2023 Report of the Auditor General of Canada to the Yukon Legislative AssemblyCOVID‑19 Vaccines in Yukon

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings and Recommendations

- The Department of Health and Social Services, the Department of Community Services, and the Executive Council Office effectively rolled out COVID‑19 vaccines in Yukon

- Outdated and incomplete emergency and pandemic planning

- Quick development of strategy to roll out vaccines

- Vaccination prioritization followed federal guidance

- Effective rollout of clinics and timely vaccinations

- Some challenges to getting vaccinated

- Sufficient staff for vaccination clinics but cultural sensitivity lacking

- The departments did not effectively collaborate and communicate with Yukon First Nations

- The monitoring of and reporting on the vaccine rollout had some weaknesses

- The Department of Health and Social Services, the Department of Community Services, and the Executive Council Office effectively rolled out COVID‑19 vaccines in Yukon

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- Recommendations and Responses

- Exhibits:

- 1—Key dates in Yukon’s COVID‑19 vaccination rollout

- 2—Locations of Yukon’s communities

- 3—Emergency and pandemic plans supplementing the Yukon Government Emergency Coordination Plan

- 4—Dose 1 was prioritized for vulnerable populations in 2021

- 5—Yukon’s vaccine coverage was comparable to Canada’s, as of 6 November 2022

- 6—Most age groups had strong coverage rates for dose 1 and dose 2, as of 31 October 2022

- 7—Yukon incurred nearly $8.8 million in direct rollout costs in the 2020–21 and 2021–22 fiscal years

- 8—Cumulative inventory and waste as reported to the Public Health Agency of Canada by 30 October 2022

Introduction

Background

1. After the World Health Organization declared the global outbreak of the coronavirus disease (COVID‑19)Definition 1 to be a pandemic in March 2020, governments around the world moved quickly to secure vaccines against the disease. Yukon’s COVID‑19 Vaccine Strategy was released in December 2020, and the rollout, which began 4 January 2021, was the most significant vaccination campaign undertaken in the territory’s history. It was part of the larger Canadian rollout (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1—Key dates in Yukon’s COVID‑19 vaccination rollout

|

25 January 2020 |

First case of COVID‑19 is confirmed in Canada |

|---|---|

|

10 March 2020 |

Yukon Government Pandemic Co‑ordination Plan is released |

|

11 March 2020 |

World Health Organization declares the global outbreak of COVID‑19 to be a pandemic |

|

18 March 2020 |

Yukon’s Chief Medical Officer of Health declares a public health emergency under the Link opens a PDF file in a new browser windowPublic Health and Safety Act |

|

22 March 2020 |

First 2 cases of COVID‑19 are confirmed in Yukon |

|

27 March 2020 |

Government of Yukon declares a state of emergency under the Link opens a PDF file in a new browser windowCivil Emergency Measures Act |

|

2 April 2020 |

Government of Yukon enacts the Civil Emergency Measures Health Protection (COVID‑19) Order |

|

9 December 2020 |

Health Canada authorizes the first COVID‑19 vaccine |

|

10 December 2020 |

Yukon’s COVID‑19 Vaccine Strategy is released |

|

Mid‑December 2020 |

Canada receives its first shipments of doses of COVID‑19 vaccine |

|

28 December 2020 |

Yukon receives its first shipment (7,200 doses) of COVID‑19 vaccine |

|

4 January 2021 |

Vaccinations begin in Yukon, starting with long‑term care residents in Whitehorse |

|

18 January 2021 |

|

|

1 March 2021 |

Whitehorse mass vaccination clinic accepts residents aged 18 years and older |

Source: The World Health Organization and various sources of the Government of Canada and the Government of Yukon

2. In Yukon, the Link opens a PDF file in a new browser windowCivil Emergency Measures Act sets out decision-making authorities in planning for and responding to emergency situations. Under the act, once the state of emergency was declared in the territory, a number of health protection, border control, and enforcement orders were made. The orders included establishing physical distancing, limiting the size of gatherings, and closing most public facilities and services. Border controls included checkstops at key entry points into the territory, from the Northwest Territories, British Columbia, and the United States on the Alaskan border. The orders also put in place strict travel restrictions and gave powers necessary for enforcement officers to ensure compliance.

3. Canada’s vaccination response was led by the federal government, which coordinated efforts with vaccine manufacturers, provinces, and territories. In December 2020, the federal, provincial, and territorial governments released Canada’s COVID‑19 Immunization Plan: Saving Lives and Livelihoods. The plan’s goal was to immunize as many Canadians as possible as quickly as possible while prioritizing high‑risk populations. As part of the plan, the federal government procured and paid for the COVID‑19 vaccines, a certain amount of cold chain equipment,Definition 2 and related essential supplies, such as needles and syringes. The federal government also managed and covered the cost of vaccine delivery to the provinces and territories. The Government of Yukon was responsible for rolling out and administering COVID‑19 vaccines within the territory and for monitoring and reporting on the rollout.

4. In Yukon, about 80% of the population lives in the capital, Whitehorse, while the remainder of the population lives in rural communities (Exhibit 2). About 20% of the Yukon population identifies as First Nations. The rural communities are geographically remote, and 1 is accessible only by plane. The rural communities face distinct challenges in accessing health and social services, which are more readily available in Whitehorse or outside of Yukon. There are 3 acute care hospitals in Yukon. This means that for some medical situations, when health services are not readily available locally, residents must travel outside of their community, including to provinces.

Exhibit 2—Locations of Yukon’s communities

Source: Population Report: Second Quarter, Yukon Bureau of Statistics, 2022

Exhibit 2—text version

This map shows the locations of Yukon’s communities. The most-populated community is the capital of Whitehorse in the southern part of the territory.

Surrounding the capital in the south are the communities of Burwash Landing, Carcross, Destruction Bay, Haines Junction, Johnsons Crossing, Mendenhall, Tagish, Teslin, and Watson Lake. Some of these communities are farther from the capital; these are Burwash Landing, Destruction Bay, Haines Junction, and Watson Lake.

Farther north toward the central part of the territory are the communities of Beaver Creek, Carmacks, Dawson City, Faro, Mayo, Pelly Crossing, and Ross River.

Finally, in the northern part of the territory is the community of Old Crow.

5. Following negotiations among the federal government, the provinces, and the territories, the 3 territories were prioritized to receive vaccines that had less extreme transport and storage requirements. This allocation recognized the territories’ remote communities and large Indigenous populations. In January and February 2021, as shipments of COVID‑19 vaccines to Canada were in short supply, the 3 territories were able to advocate to keep their allocations from being reduced. This allowed the territories to roll out the vaccine to all residents without additional delays or expenses.

6. Yukon was one of the first of Canada’s territories and provinces to receive COVID‑19 vaccines. As a result, the Government of Yukon had to roll out the vaccines to its population without having the benefit of lessons already learned elsewhere.

7. In Yukon, 11 of the 14 First Nations have entered into self‑government agreements, under which they can make their own laws and policies and have decision-making power in a broad range of matters with respect to their Settlement Lands and citizens. The Government of Yukon recognizes a historical legacy of colonialism and discrimination in Canada. It also recognizes that many Indigenous communities and people have experienced significant trauma—including from communicable diseases. The territorial government included cultural safety and humility as a principle of response to the COVID‑19 pandemic.

8. In Yukon, the rollout of COVID‑19 vaccines was managed by the Department of Health and Social Services and the Department of Community Services, with the support of the Executive Council Office.

9. Department of Health and Social Services. The department, with the expert advice of the Chief Medical Officer of Health, is responsible for protecting, promoting, and restoring the well‑being of Yukon residents. It is also responsible for direct management of the spread and control of disease and treatment of the public, including

- providing information to the public on health issues

- providing care and treatment advice to clinical care providers

- delivering antiviral and vaccination programs

- coordinating and managing health resources

10. Department of Community Services. The responsibilities of the department include

- directing and administering the Yukon Emergency Measures Organization, which, in accordance with the Civil Emergency Measures Act, provides overall government‑wide coordination for responses to major emergencies and disasters

- maintaining the organization’s website and other emergency public information sources

- delivering responses to inquiries from the public

- promoting and educating the public on the importance of general individual emergency preparedness

11. Executive Council Office. The Aboriginal Relations Division within the Executive Council Office is responsible for providing support and leadership to government departments on reconciliation initiatives. The responsibilities of the Aboriginal Relations Division include

- providing corporate leadership and advice to support a strategic, government‑wide approach to reconciliation and collaboration with Indigenous governments, communities, and organizations

- advising Government of Yukon departments on how to strengthen relationships, fulfill consultation obligations, and implement agreements with Indigenous governments

- undertaking negotiations with Indigenous governments on behalf of the Government of Yukon

- collaborating with Indigenous governments on shared priorities to improve the lives of all Yukoners

- providing corporate policy advice on initiatives that advance reconciliation with Yukon First Nations and transboundary Indigenous groups

Focus of the audit

12. This audit focused on whether Yukon’s Department of Health and Social Services, Department of Community Services, and Executive Council Office managed the rollout of the COVID‑19 vaccines in an effective and equitable manner to protect the health and well‑being of Yukon residents. According to the Government of Yukon Gender Inclusive Diversity Analysis (GIDA) Action Plan, an equitable strategy considers factors such as age, race, gender, economic, and rural status and is fair and inclusive.

13. This audit is important because vaccines are considered to be one of the most important public health tools available for preventing serious illness and controlling infectious disease outbreaks. Vaccinating people also increases access to health care by lessening the burden on health‑care workers. As well, widespread immunization allows an easing of health-related restrictions.

14. More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings and Recommendations

The Department of Health and Social Services, the Department of Community Services, and the Executive Council Office effectively rolled out COVID‑19 vaccines in Yukon

15. This finding matters because without vaccinating as many residents as possible in the shortest amount of time, there was an elevated risk of the spread of the coronavirus and susceptibility to serious illnesses and possible deaths. Carrying out an effective COVID‑19 vaccination campaign was critical to minimizing disruption and protecting infrastructure essential to keep society functioning. This was particularly important in smaller and more remote communities with limited resources. This would enable them to respond to the health emergency while continuing to care for people with other medical needs.

16. The Link opens a PDF file in a new browser windowCivil Emergency Measures Act sets out the powers and responsibilities of the Government of Yukon to plan for and respond to emergencies. The act requires that the Yukon Emergency Measures Organization, under the Department of Community Services, produce an overall government plan for responding to emergency situations. The most recent version of the plan—the Yukon Government Emergency Coordination Plan—is from December 2011. The plan provides high‑level strategies, including the roles and responsibilities across government departments, but is not intended to be a stand-alone plan. Additional emergency and pandemic plans were developed for use in conjunction with the Yukon Government Emergency Coordination Plan (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3—Emergency and pandemic plans supplementing the Yukon Government Emergency Coordination Plan

| Plans | Description |

|---|---|

| Departmental emergency plans | Each Government of Yukon department is responsible for preparing, regularly reviewing, and updating an emergency plan specific to its defined area of responsibility. Departmental emergency plans include business continuity and recovery plans and outline in detail the role and responsibilities of the department in dealing with emergencies. |

| Yukon Government Pandemic Co‑ordination Plan, 2010 | The Yukon Government Pandemic Co‑ordination Plan was developed to more specifically guide the territory’s preparedness for and response to a pandemic. It establishes that the Department of Health and Social Services, with the advice of the Chief Medical Officer of Health, is solely responsible for leading the government’s response to pandemic health issues. |

| Pandemic Health Response Plan, Yukon Department of Health and Social Services, 2009 | The Department of Health and Social Services uses its Pandemic Health Response Plan as the central document guiding the department’s pandemic planning and response effort. |

Source: Various sources of the Government of Yukon

Outdated and incomplete emergency and pandemic planning

17. We found that emergency and pandemic planning in Yukon was outdated and incomplete. The Government of Yukon developed high‑level, government‑wide plans roughly a decade before the COVID‑19 pandemic but did not update them until after the pandemic started. In addition, the updates were limited. For example, the only changes made to the 2020 version of the Yukon Government Pandemic Co‑ordination Plan, updated from 2010, were deleting references to the H1N1 virus and adjusting the appendices.

18. Furthermore, we found that the most recent pre‑pandemic emergency plans developed for the Department of Health and Social Services in 2015, the Department of Community Services in 2015, and the Executive Council Office in 2012 were outdated and incomplete. For example, sections were underdeveloped and information was missing. This could leave those departments unprepared to fully and effectively respond to emergencies that might arise.

19. The Department of Health and Social Services, the Department of Community Services, and the Executive Council Office should update their emergency plans so that they complement each other to ensure a prompt and comprehensive response to future health emergencies.

The 3 departments’ response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Quick development of strategy to roll out vaccines

20. Despite outdated and incomplete emergency and pandemic plans (see paragraphs 17 and 18), we found that once COVID‑19 vaccines were available, the Department of Health and Social Services collaborated with the Department of Community Services and the Executive Council Office to provide timely access to vaccines in Yukon.

21. Before getting the vaccine, the Department of Health and Social Services used the 2020 annual flu clinic in Whitehorse as a starting point for the COVID‑19 vaccine rollout. More than 14,000 Yukoners received the flu vaccine over a 6‑week period in October and November, the majority at a single location. The department leveraged existing partnerships and expertise of key stakeholders and modelled the mass COVID‑19 vaccinations after the Whitehorse flu clinic.

22. In December 2020, the Government of Yukon released its COVID‑19 vaccine strategy. The goal of the strategy was to administer the COVID‑19 vaccine to every eligible Yukoner who wanted to receive it and, in doing so, to reduce the rate of transmission and the severity of illness. The strategy included considering the needs of First Nations and groups it identified as vulnerable (Exhibit 4).

Vaccination prioritization followed federal guidance

23. We found that the Department of Health and Social Services used guidance from Canada’s National Advisory Committee on ImmunizationDefinition 3 to prioritize key populations for the COVID‑19 vaccine rollout. Prioritization for vaccinations in Yukon was determined in consultation with Yukon’s Chief Medical Officer of Health on the basis of a variety of risk, logistical, and epidemiological considerations. These included the evolving evidence base for COVID‑19 and vaccine characteristics, the timing and quantity of shipments, the particular vulnerabilities of certain groups, and the challenges of transporting and administering vaccines in Yukon, given its geography, infrastructure, and population.

24. We found that the Department of Health and Social Services prioritized administering the initial vaccine dose to the most vulnerable populations in Yukon (Exhibit 4). Administering vaccines started for the priority groups in Whitehorse. This was followed by individuals aged 18 and older living in the rural communities, beginning with communities along the territorial borders and the Alaska Highway. The mass vaccination clinic in Whitehorse opened to the general public on 1 March 2021.

Exhibit 4—Dose 1 was prioritized for vulnerable populations in 2021

| Date | Prioritization for dose 1 in Whitehorse | Prioritization for dose 1 in rural communities |

|---|---|---|

|

4 to 17 January 2021 |

|

Long‑term care residents and staff and high‑risk health‑care staff in Dawson City (13 January) |

|

18 to 24 January 2021 |

|

Residents aged 18 and older of Watson Lake, Beaver Creek, and Old Crow |

|

25 to 31 January 2021 |

Continuation of high‑risk and vulnerable populations included the previous week |

Residents aged 18 and older of Dawson City, Teslin, Carcross, Tagish, and Pelly Crossing |

|

1 to 6 February 2021 |

Residents aged 60 and older |

Residents of Burwash Landing, Destruction Bay, Haines Junction, Carmacks, Mayo, Faro, and Ross River |

Note: Although First Nations were not identified as a vulnerable group, their members were prioritized in other ways, such as through mobile clinics to rural communities, through special clinics for First Nations health‑care staff and Elders in Whitehorse, and through the Whitehorse Emergency Shelter.

Source: Yukon’s COVID‑19 Vaccine Rollout Schedule, Yukon Department of Health and Social Services, 2021

25. We found that the Department of Health and Social Services vaccinated clients and staff of some organizations providing services to higher‑risk populations before others providing similar services. Some of these services are provided in locations where physical distancing and other infection prevention and control measures are challenging. These types of settings put those working and living in them at a higher risk of becoming infected.

26. Staff from a number of organizations told us there was a lack of clarity about which clients and employees would be prioritized by the Department of Health and Social Services. They did not understand why their organizations had not been prioritized. They were concerned that given the risks they faced, they should have been eligible to be vaccinated at the same time as prioritized organizations providing similar services.

27. An example of a prioritized organization was the Whitehorse Emergency Shelter, where the first vaccination clinic was held on 25 January 2021. The Department of Health and Social Services told us that it was prioritized because it is the largest shelter in Whitehorse and is a service hub for individuals experiencing homelessness. In addition to clients, who were the prioritized vaccine recipients, staff were also given the opportunity to be vaccinated, ahead of the planned prioritization. The department told us this was done to avoid wasting doses from already opened vials. Other organizations in Whitehorse providing services similar to those of the emergency shelter told us they had to wait to be vaccinated until the mass vaccination clinic opened to the general public on 1 March 2021. We noted that no additional clinics were set up specifically for these organizations.

28. There is no information in the National Advisory Committee on Immunization guidelines on prioritizing within a group of organizations that all provide services in the same types of settings. Furthermore, certain groups that were to be prioritized according to early Government of Yukon communications in the end were not. In our view, other organizations providing similar services and facing comparable risks of infection should be similarly prioritized, and decisions about prioritization should be clearly communicated to organizations.

29. The Department of Health and Social Services should ensure that organizations providing similar services and facing comparable risks of infection should be prioritized for vaccination in an equivalent manner. This prioritization should be included in emergency planning documentation.

The department’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Effective rollout of clinics and timely vaccinations

30. We found that the Department of Health and Social Services and the Department of Community Services established COVID‑19 vaccination clinics quickly and effectively. As noted in paragraph 22, the Government of Yukon released its COVID‑19 vaccine strategy in December 2020. The Department of Health and Social Services then established how it would provide access to the COVID‑19 vaccines throughout the territory and outlined this in operational documents. The Yukon Emergency Measures Organization—under the Department of Community Services—would provide logistical support, and the Department of Health and Social Services would provide clinical staff and expertise.

31. The Department of Health and Social Services assembled 5 multidisciplinary teams to coordinate and administer the vaccine rollout to the Yukon population and ran mock clinics for practice. The teams included nurses, pharmacists, administrative personnel, drivers, and greeters and were composed of employees from across Government of Yukon departments:

- The Logistics and Clinical Coordination team was responsible for setting up practical clinical needs, such as location, equipment, and travel arrangements.

- The Whitehorse Priority Populations team provided long‑term care residents, home‑bound individuals receiving home care services, and vulnerable populations in Whitehorse with their first 2 doses.

- The Whitehorse Vaccinations team administered vaccines at a mass vaccination clinic in Whitehorse.

- Two mobile vaccine teams travelled to rural communities to administer vaccines.

32. The model for multidisciplinary teams was designed to

- minimize the number of different delivery sites

- use human resources efficiently

- respect the limitations of the stability and mobility of the COVID‑19 vaccine

33. Administration of the vaccine was handled differently on the basis of whether people lived in Whitehorse or in rural communities, which contributed to the efficiency of the rollout. In Whitehorse, eligibility was phased in to the population for vulnerable groups and according to age. Vaccinations there began with priority groups on 4 January 2021. On 18 January 2021, eligibility was phased in according to age at the mass vaccination clinic, starting with residents aged 70 and older.

34. In the rural communities, all residents aged 18 and older were eligible for vaccinations during scheduled mobile clinic visits. To prepare for this, advance teams of 3 to 5 individuals went to the rural communities to share information about the vaccine rollout, coordinate with organizations and individuals in the community, and prepare for the set‑up of the vaccine clinics. On 18 January 2021, the 2 mobile teams began administering the first dose of vaccines in conjunction with local health‑care staff, including community-based nurses. We found that having 2 mobile teams allowed multiple immunizers to travel from location to location to vaccinate as many people as possible within a specific time frame without burdening local health‑care centres.

35. In early February 2021, the second dose of vaccinations began in Whitehorse for priority groups, and the 2 mobile teams returned to rural communities. Throughout the remainder of 2021 and 2022, the first and second vaccine boosters became available. In Whitehorse, vaccinations continued to be administered at the mass vaccination clinic. Outside of Whitehorse, responsibility for administering vaccines was gradually transferred from the mobile teams to local Department of Health and Social Services health‑care centres. By December 2021, the transition was completed and mobile teams were disbanded.

36. By 6 November 2022, 81% of the population of Yukon had received 2 doses and its vaccination status was comparable to the rest of Canada (Exhibit 5).

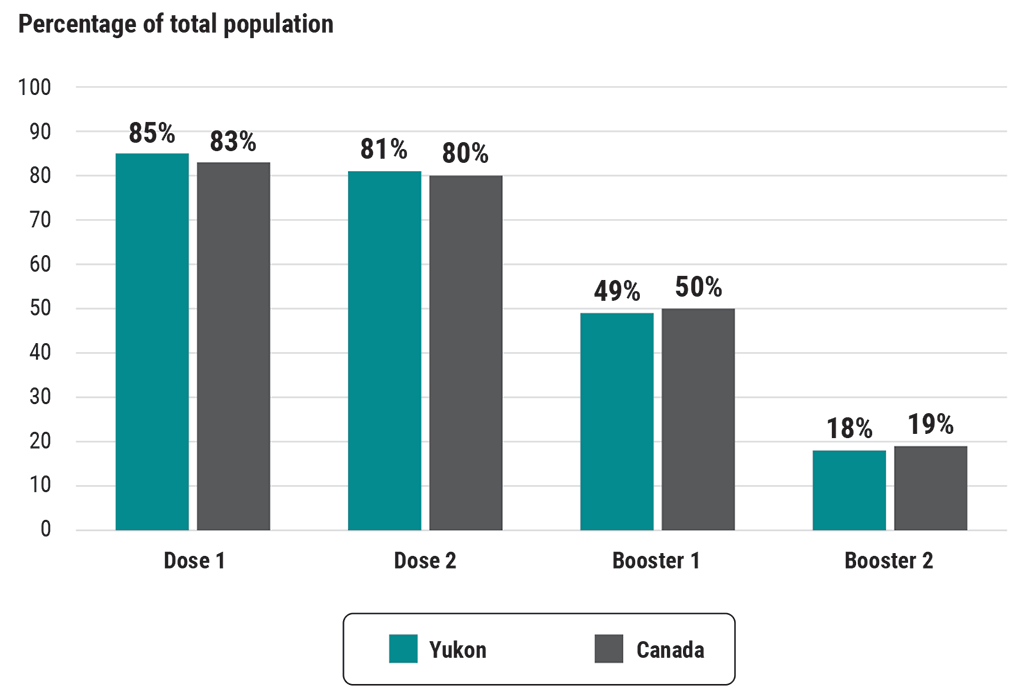

Exhibit 5—Yukon’s vaccine coverage was comparable to Canada’s, as of 6 November 2022

Source: Yukon Department of Health and Social Services and the Government of Canada’s Health Infobase

Exhibit 5—text version

This bar chart shows Yukon’s and Canada’s vaccine coverages as of 6 November 2022. Both coverages were comparable for dose 1, dose 2, booster 1, and booster 2. In Yukon, more people received dose 1 and dose 2, similar to the rest of Canada, and fewer people received booster 1 and booster 2, also similar to the rest of Canada:

- Dose 1 was administered to 85% of Yukon’s population and 83% of Canada’s population.

- Dose 2 was administered to 81% of Yukon’s population and 80% of Canada’s population.

- Booster 1 was administered to 49% of Yukon’s population and 50% of Canada’s population.

- Booster 2 was administered to 18% of Yukon’s population’s and 19% of Canada’s population.

37. As of 31 October 2022, the coverage for the first and second doses was strong across most age groups in Yukon (Exhibit 6). The coverage was similar between men and women for the first 2 doses; for the 2 boosters, the coverage was slightly higher for women. As of 31 October 2022, almost 5,000 COVID‑19 cases in Yukon had been confirmed, and 32 related deaths were reported. At that time, Canada’s total number of cases amounted to nearly 4.4 million, and the total number of deaths was about 47,000.

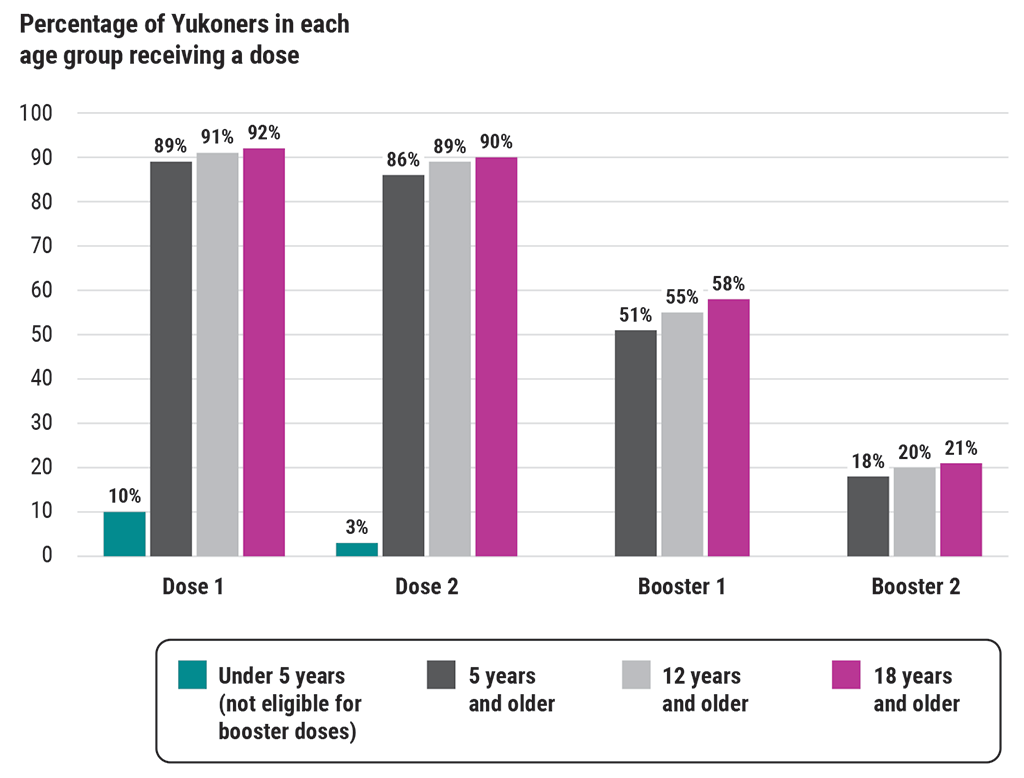

Exhibit 6—Most age groups had strong coverage rates for dose 1 and dose 2, as of 31 October 2022

Source: Yukon Department of Health and Social Services

Exhibit 6—text version

This bar chart shows the vaccine coverage rates of Yukoners by age group as of 31 October 2022. The age groups are under 5 years, 5 years and older, 12 years and older, and 18 years and older. Most age groups had strong coverage for dose 1 and dose 2:

- Dose 1 was administered to 10% of the under‑5‑years age group, 89% of the 5‑years‑and‑older age group, 91% of the 12‑years‑and‑older age group, and 92% of the 18‑years‑and‑older age group.

- Dose 2 was administered to 3% of the under‑5‑years age group, 86% of the 5‑years‑and‑older age group, 89% of the 12‑years‑and‑older age group, and 90% of the 18‑years‑and‑older age group.

- Booster 1 was administered to 51% of the 5‑years‑and‑older age group, 55% of the 12‑years‑and‑older age group, and 58% of the 18‑years‑and‑older age group. The under‑5‑years age group was not eligible for booster 1.

- Booster 2 was administered to 18% of the 5‑years‑and‑older age group, 20% of the 12‑years‑and‑older age group, and 21% of the 18‑years‑and‑older age group. The under‑5‑years age group was not eligible for booster 2.

38. We found that the Department of Health and Social Services developed a clear schedule for mobile teams in terms of where and when they would be administering vaccines. We also found that doses were administered in a timely manner as they became available, both in the communities and at the mass vaccination clinic in Whitehorse. Within 6 weeks of receiving the first shipment of vaccines, the department had administered doses to individuals aged 18 and older in rural communities and all identified priority groups in Whitehorse. The department effectively monitored the shipments of vaccines it was receiving from the Public Health Agency of Canada. It also administered doses as permitted according to the recommended intervals between the first and second doses. At the clinics, the Department of Health and Social Services and the Department of Community Services organized logistics well. We found that there was sufficient supply of vaccines, doses, and clinical supplies, and standard precautions, such as masking and physical distancing, were in place and monitored.

39. Regarding territory‑wide communications planning and monitoring, we found that information was available to the public on when and where to be vaccinated. This was provided through the Government of Yukon website, radio and television advertisements, posters, social media, a telephone line, and news conferences with health officials. However, the department was unable to provide us with complete communications plans and monitoring and tracking tools. In our view, it is important for plans to be complete and to track their implementation in order to know if communication has been effective.

40. We also inquired about the costs to the Government of Yukon of the COVID‑19 vaccine rollout. The federal government procured and paid for vaccines, a certain amount of cold chain equipment, and related essential supplies, such as needles and syringes. But the Government of Yukon incurred costs, such as employee transportation, accommodation, and overtime. We found that the Department of Health and Social Services was responsible for tracking those costs. We did not audit these costs; however, we noted that direct costs relating to the vaccine rollout, as reported by the department, amounted to nearly $8.8 million for the 2020–21 and 2021–22 fiscal years (Exhibit 7). In our view, it is important to monitor these costs even during a pandemic to account for how public money is spent and to help in planning for possible future pandemics.

Exhibit 7—Yukon incurred nearly $8.8 million in direct rollout costs in the 2020–21 and 2021–22 fiscal years

| Type of cost | Amount |

|---|---|

| Communications | $451,244 |

| Travel and accommodation | $647,517 |

| Personnel | $4,320,760 |

| Other (rentals, hardware, software, printing) | $3,367,161 |

| Total | $8,786,682 |

Source: Yukon Department of Health and Social Services

Some challenges to getting vaccinated

41. Several non‑governmental organizations told us that some residents faced barriers to getting vaccinated. For example, vaccinations in Whitehorse and the communities were initially provided by appointment, and Yukoners had to reserve via a booking system—online or by phone—using their health‑care card. Some residents in Yukon do not have a land‑line telephone or cellular service, a computer or Internet connection, or a health‑care card. As a consequence, some residents, in particular those within vulnerable populations, such as individuals experiencing homelessness, experienced delays booking an appointment. Their options included relying on others to assist them, such as First Nations support staff, community health‑care workers, and employees of non‑governmental organizations.

42. We found that the Department of Health and Social Services and the Department of Community Services made efforts to lift barriers at clinics. For example, they made special accommodations for individuals with autism or allergies; accepted non‑residents of Yukon, such as members of First Nations outside the territory’s borders; and over time established workarounds for Yukoners without a health‑care card. And while the general public in Whitehorse initially could be vaccinated only by appointment, the Government of Yukon published a media release on 3 March 2021 stating that the mass vaccination clinic would begin accepting walk‑ins on 11 March 2021.

43. Moreover, we found that the departments modified and communicated operational plans as needed when circumstances changed. For example, they modified the schedule for the mobile teams when a community made them aware that some residents were hesitant and had concerns. In this situation, the Department of Health and Social Services changed its schedule for the mobile clinics to give the community more time to prepare.

44. Some community representatives told us that the logistical plans for mobile vaccine clinics were not always well communicated to community leaders. For example, Government of Yukon staff sometimes first contacted managers of locations such as gyms and recreational centres instead of the municipal mayors or First Nations leaders to arrange the logistics for the vaccination clinics. The departments did not use the territory’s emergency and pandemic planning framework for the vaccine rollout. We found that even if they had used the framework, it specifies only that appropriate parties should be kept informed—it does not specify which parties should be the necessary points of contact.

45. For future vaccine rollouts, the Department of Health and Social Services and the Department of Community Services should provide and communicate alternatives to online and phone options for booking services that are as barrier‑free as possible.

The 2 departments’ response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Sufficient staff for vaccination clinics but cultural sensitivity lacking

46. We found that the Department of Health and Social Services had sufficient staff so that eligible residents who wanted to be vaccinated were able to receive the initial doses and boosters. Given that the COVID‑19 pandemic extended over a long period of time, demands on vaccination staff were considerable. We found that in planning its response to the pandemic, the department assessed that it needed just over 100 full‑time‑equivalent staff for the vaccine teams, which would include nurses and other trained immunizers from across the territory.

47. The Department of Health and Social Services provided training to immunizers who were administering COVID‑19 vaccines in vaccination clinics and health centres. This training had to be completed before immunizers could begin working in clinics. The training was for administering the vaccines and the logistics, such as safe storage and transport of the vaccines. The Government of Yukon kept track of all courses completed by immunizers, which allowed it to know how many staff were qualified. Immunizers were also trained to respond to concerns and dispel vaccine myths raised by the public with messaging about vaccine safety.

48. We found that the training given to immunizers included brief and general cultural sensitivity information. Registered nurses had to complete mandatory courses and orientation, including one course specific to Yukon First Nations, to obtain their licence. Although cultural sensitivity training was mandatory for some nurses, many other immunizers and individuals who planned and supported front‑line immunization services to First Nations did not receive the same training. Residents, health‑care professionals, and non‑governmental organizations shared with us that the clinics and communications should have been provided in a more culturally safe and sensitive manner. There was a perception that the environment was overly clinical and lacked warmth and welcoming and that there was little cultural support provided at clinics, unless provided by First Nations.

49. Some First Nations and non‑governmental organizations told us that some residents had anxieties about getting vaccinated, including concern that they were the test cases to determine the efficacy of the vaccination. Cultural safety was an important issue in the Yukon vaccine rollout because of vaccine hesitancy among First Nations due to colonialism and past trauma.

50. The Department of Health and Social Services should ensure that Yukon‑specific cultural competency training is delivered to those planning and providing front‑line immunization services to better meet First Nations’ needs.

The department’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

The departments did not effectively collaborate and communicate with Yukon First Nations

51. Collaboration and communication with Yukon First Nations are important for the Government of Yukon to make decisions that are fair and well informed, including on the COVID‑19 vaccine rollout. Collaboration provides opportunities for increased relationship building, which can improve both trust in the territorial government and government‑to‑government relationships and make meaningful steps toward reconciliation.

52. The Government of Yukon committed to thoughtful engagement with Yukon First Nations governments and support for community‑led approaches in Yukon’s COVID‑19 Vaccine Strategy, in addition to adding cultural safety and humility as a principle.

53. Since 2005, the Government of Yukon has been legislated, through the Link opens a PDF file in a new browser windowCooperation in Governance Act, to discuss issues of common concern with First Nations at least 4 times a year in formal, government‑to‑government meetings through the Yukon Forum. Membership of the forum includes representatives from the Government of Yukon, Yukon First Nations, and the Council of Yukon First Nations. The purpose of the Yukon Forum is to build strong government‑to‑government relations and to identify and collaborate on shared priorities and areas of responsibility, such as health. This includes identifying opportunities and common priorities for cooperative action and formulating direction.

Insufficient collaboration with Yukon First Nations in planning vaccine rollout

54. We found that Yukon First Nations were not involved in pandemic and emergency planning, nor were they given the opportunity to provide input on Yukon’s COVID‑19 Vaccine Strategy, which was made public on 10 December 2020. We also found that First Nations were briefed late in the planning of the vaccine rollout and had limited input throughout its implementation.

55. The rollout was a significant undertaking, and the departments had to deal with evolving information. For example, confirmation of quantities and information on the timing of shipments came only in late December 2020. First Nations and community leaders were informed in January 2021 of vaccination schedules and locations through government-organized calls, government liaison officers, and mobile clinic staff arriving in the communities prior to the start of vaccination clinics. However, this engagement was done on tight deadlines and with limited dialogue.

56. The Cooperation in Governance Act recognized the importance of having a space for collaboration. The Yukon Forum met 9 times between February 2020 and June 2022. The meetings covered topics such as Yukon’s Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls and Two‑spirit+ People Strategy, land use, and the Putting People First report. We found that there were limited discussions on the COVID‑19 vaccination rollout. For example, in May 2020, the forum meeting included discussion on the COVID‑19 pandemic and the public health measures to maintain until a vaccine was available. The forum meeting in December of that year had an agenda item to discuss the COVID‑19 vaccine rollout. We also found that the forum was not used to define the level and frequency of collaboration between the territorial government and Yukon First Nations for a COVID‑19 vaccine rollout. In our view, this represented a missed opportunity to agree on the collaboration needed between parties.

57. The departments also had regular committee meetings and calls with Yukon First Nations throughout the rollout. These varied in frequency—some daily, some weekly, and some as needed. While the departments made efforts to engage regularly and share information frequently, First Nations initiated calls and committee meetings outside of those initiated by the departments to meet their own needs.

58. Months passed between the Government of Yukon declaring a state of emergency under the Civil Emergency Measures Act on 27 March 2020 and the territory receiving its first shipment of COVID‑19 vaccines in December 2020. The Department of Health and Social Services and the Department of Community Services had time to meaningfully collaborate with First Nations and receive their input on the rollout plan, including on how communications would be managed, potential barriers their communities could face, and issues regarding vaccine hesitancy.

59. The Department of Health and Social Services and the Department of Community Services, with the support of the Executive Council Office, should partner with Yukon First Nations to outline the expected level and frequency of collaboration during emergencies. This understanding should include clear roles and responsibilities and timing of communications during an emergency situation and should be reflected in emergency plans.

The 2 departments’ response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Inadequate sharing of information with First Nations and rural communities

60. We found that the responsible departments did not discuss the collection and sharing of data with First Nations as part of emergency and pandemic planning. During the pandemic, the departments received requests from some First Nations for COVID‑19 data related to their own citizens.

61. We found that the information that First Nations and communities received from the departments did not, in their opinion, meet their needs. While the Government of Yukon shared vaccination rates and cases on a regional level—amalgamated results for multiple communities—information specific to communities was not shared until May 2021. The Department of Health and Social Services told us that this information was not shared earlier to avoid stigmatizing rural communities on the basis of vaccination rates.

62. The Department of Health and Social Services does not have access to nor does it collect information on First Nations status for any programs, including the immunization programs. The system that tracks immunizations has a field to capture First Nations status, but we found that the department did not collect data on First Nations status when administering COVID‑19 vaccines. During the planning of the pandemic response, the department did not ask First Nations governments if their residents would be willing to self‑identify. The department told us this was because of privacy reasons and because it did not want to create hesitancy among First Nations members, who might have considered it to be stigmatizing.

63. In May 2021, the Government of Yukon began publishing vaccination rates by rural community on its website. This information did not distinguish between Indigenous and non‑Indigenous people. This meant that it was not possible to determine what percentage of First Nations people were vaccinated. Collecting data on communities and specific vulnerable groups would allow trend analysis and could help identify ways to improve service delivery and immunization coverage.

64. Department officials sought permission to begin creating data‑sharing agreements with interested Yukon First Nations governments only in November 2021. At the end of our audit period, there was 1 data‑sharing agreement in place with 1 First Nation.

65. The Department of Health and Social Services, with the support of the Executive Council Office, should work with First Nations toward finalizing data‑sharing protocols or agreements to meet the needs of First Nations.

The department’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

The monitoring of and reporting on the vaccine rollout had some weaknesses

66. This finding matters because vaccines can be a scarce resource, especially in their early months of availability. It is important to have comprehensive systems in place to track and report accurate information to Yukon residents but also to the Government of Canada. Information such as the vaccine inventory on hand and vaccine wastage can help the Government of Yukon to make better-informed decisions on vaccine needs. Also, during the COVID‑19 pandemic, Yukon did not have a vaccine storage facility that met federal requirements for transferring expiring vaccines to other jurisdictions. This meant that Yukon needed to carefully manage inventory and minimize the number of wasted doses.

67. Like all other jurisdictions in Canada, Yukon was asked to report to the Public Health Agency of Canada weekly on the cumulative number of people vaccinated for each of dose 1, dose 2, and the booster doses. The reporting was by product, sex, age, and, to the extent possible, key populations. Yukon was also asked to report, subject to privacy considerations and limitations, weekly counts of adverse events following immunization. Such events included any unexpected medical event that followed immunization whether or not it appeared to be linked to receiving the vaccine.

Inefficient manual systems to monitor inventory and waste

68. We found that the Department of Health and Social Services was able to order vaccines from the Public Health Agency of Canada on the basis of the initial per capita allocation and later on the basis of Yukon’s needs. When shipments of vaccines were received from the Public Health Agency of Canada, they were stored initially by the Yukon Hospital Corporation at the Whitehorse General Hospital and were later distributed to the vaccination clinics and local health‑care centres in rural communities.

69. We found that the Department of Health and Social Services did not have an efficient inventory management system in place to track the movement of vaccines in real time among its multiple storage locations and to manage supply. It managed inventory and waste using Excel spreadsheets. Specifically, it used the information from clinic and health‑care centre documents to manually compile in master spreadsheets the reported levels for each vaccine product. Inventory and waste were reported daily to the department’s central office.

70. Because the department manually compiled this information, we found inaccuracies in the data, such as errors in expiry dates and lot numbers. Also, we could not reconcile some levels of waste and inventory reported to the Public Health Agency of Canada. We found that discrepancies were due to human data entry errors, calculation errors, and lack of real‑time data.

71. We found that the Department of Health and Social Services could not determine with precision its inventory levels of vaccines. We were able to confirm that the department tracked the total number of shipments and related vials received from the federal government. Each vial contained a pre‑established number of doses. However, we found that immunizers could sometimes extract 1 additional dose from a vial and that these additional doses were never added to the total inventory count in Yukon. We also found that when booster doses were introduced, an error was made in how wastage was recorded for about a 16‑week period. This error occurred because 1 vaccine product required that the booster shot use half the volume of dose 1 and dose 2. However, the waste for these booster doses was recorded as a full dose. The department could not correct this error by simply halving the amounts misrecorded partly because some people, such as those aged 70 years and older and immunocompromised individuals, received the full volume of the dose for their booster shots. Overall, this meant that the amount of wastage may have been overstated and that inventory levels could not be perfectly reconciled.

72. The Department of Health and Social Services reported that by 30 October 2022, 103,854 shots in arms were administered no matter the vaccine volume used. This differs from the 95,379 cumulative number of full‑volume doses administered that the department had reported weekly to the Public Health Agency of Canada as of 30 October 2022. Exhibit 8 presents the inventory reported on that date according to the pre‑established doses per vial, as reported to the federal government.

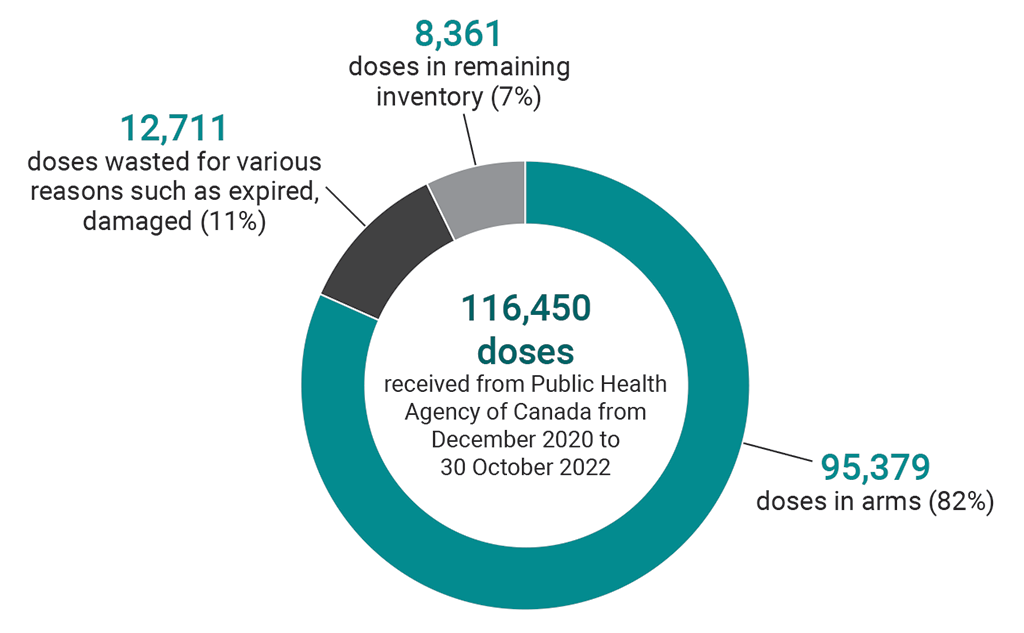

Exhibit 8—Cumulative inventory and waste as reported to the Public Health Agency of Canada by 30 October 2022

Note: Doses have been rounded to the nearest whole number.

Source: Yukon Department of Health and Social Services

Exhibit 8—text version

This pie chart shows the breakdown of the 116,450 vaccine doses that Yukon received from the Public Health Agency of Canada from December 2020 to 30 October 2022:

- There were 95,379 doses in arms. This represented 82% of the total number of doses received.

- There were 12,711 doses wasted for various reasons such as being expired or damaged. This represented 11% of the total number of doses received.

- There were 8,361 doses in the remaining inventory. This represented 7% of the total number of doses received.

73. Early in the vaccine rollout, the department issued guidance to minimize waste. We noted that in the first 3 months after vaccines became available in January 2021, when doses were scarce, only 43 doses (or 0.08%) were wasted. As of 30 October 2022, nearly 11% of doses had been wasted (Exhibit 8). We found that reasons to account for most of the wastage changed over time. In 2021, the majority of wastage (60%) was due to people not showing up for their appointment or cancellations. In 2022, most wastage (57%) was due to expired vaccines.

74. Given that by September 2021, over 80% of Yukon’s adult population had received the first 2 doses and that Yukon had experienced a significant number of cases in the summer, the Department of Health and Social Services was expecting a 75% coverage for the first booster dose. We found that the department placed large orders for 1 vaccine product to be received on 11 October 2021 (3,080 doses), 1 November 2021 (10,080 doses), and then only 3 weeks later, on 22 November 2021 (10,000 doses). Because the coverage for the first booster was only approximately 50%, the department reported a waste of 4,544 expired doses of this product in the second quarter of 2022. While the department managed inventory by using vials closest to expiration first, staggering smaller orders would have minimized wastage. We found that the department did do this for subsequent orders, which were smaller and more staggered in time.

75. The Department of Health and Social Services should develop accurate and comprehensive inventory systems and practices to track vaccine inventory, wastage, and expected coverage. This information should be used for decisions on timing and quantities of vaccine needed and to track the movement of vaccines in real time across the territory.

The department’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Mostly timely COVID‑19 data reporting

76. On the basis of a selected sample of reports, we found that the Department of Health and Social Services reported on coverage, inventory, wastage, and adverse events following immunization to the Public Health Agency of Canada on a weekly basis. We also found that the department corresponded with its federal counterparts to validate information required to be reported and timing requirements.

77. For serious adverse events, such as deaths, or other adverse events of special interest, provinces and territories were asked to report to the Public Health Agency of Canada within 24 hours of becoming aware of the event. The Department of Health and Social Services indicated that delays in bloodwork and diagnosis made it difficult to report severe adverse events within 24 hours, but it reported those instances to the Public Health Agency of Canada at least weekly. From 1 January 2021 to 31 October 2022, the department reported a total of 550 adverse events following immunization, representing 0.5% of the 103,854 shots in arms administered. Only 0.03% of all doses administered were categorized as serious adverse events. Making information on adverse events following immunization available to the Public Health Agency of Canada is important for improving public safety by, for example, better understanding and preventing side effects.

Conclusion

78. We concluded that the Department of Health and Social Services, the Department of Community Services, and the Executive Council Office managed the rollout of the COVID‑19 vaccines in an effective and equitable manner to protect the health and well‑being of Yukon residents.

79. However, the audit identified opportunities for the departments to improve future plans, in particular in communications with First Nations and inventory management, which are about efficiency and preventing wastage, so that departments are better prepared for future emergency situations.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on the vaccine rollout in Yukon. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist the Legislative Assembly in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs and to conclude on whether the management of the rollout of COVID‑19 vaccines in Yukon complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada applies the Canadian Standard on Quality Management 1—Quality Management for Firms That Perform Audits or Reviews of Financial Statements, or Other Assurance or Related Services Engagements. This standard requires our office to design, implement, and operate a system of quality management, including policies or procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether the responsible Government of Yukon organizations—the Department of Health and Social Services, the Department of Community Services, and the Executive Council Office—managed the rollout of the COVID‑19 vaccines in an effective and equitable manner to protect the health and well‑being of Yukon residents.

Scope and approach

We examined how the government organizations responsible for the COVID‑19 response on behalf of the Government of Yukon oversaw the COVID‑19 vaccine rollout by developing plans, implementing and communicating them, and conducting monitoring of and reporting on core elements of the COVID‑19 vaccine rollout.

We examined the relevant legislation, plans, policies, and procedures related to the vaccination rollout in Yukon. We interviewed officials from the Department of Health and Social Services, the Department of Community Services, the Executive Council Office, and government partners, including the Council of Yukon First Nations and several First Nations in the territory. We also interviewed several rural communities and their municipal representatives, and other organizations implicated in the vaccination rollout. We analyzed data with respect to inventory and waste management and tools used to forecast demand. We did not examine the following:

- procurement of vaccines

- authorization of COVID‑19 vaccines

- vaccine rollout schedule prior to approval by Cabinet

- sequencing of the initial and subsequent doses

- quality of training

- impacts of the implementation of the vaccine rollout on health‑care workers

Criteria

We used the following criteria to conclude against our audit objective:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

The responsible Government of Yukon departments develop an equitable vaccine strategy and operational plans with clear roles and responsibilities to oversee the core elements of the vaccination rollout. The core elements, as part of Yukon’s COVID‑19 Vaccine Strategy, comprise vaccine distribution, administration, and safety and effectiveness. |

|

|

For core elements of the vaccination rollout, the responsible Government of Yukon departments implement plans and monitor results to inform decision making and make needed adjustments in a timely manner. Core elements comprise allocation (vaccine rollout schedule), vaccine inventory management, training, recruitment and staffing strategy, vaccine uptake, and adverse events. |

|

|

The responsible Government of Yukon departments ensure that Yukon residents have timely access to accurate and clear information about when and where they can access the vaccines in a manner supported by accessible language and culturally safe approaches in order to reduce vaccine hesitancy. |

|

|

The responsible Government of Yukon departments ensure the transparent and timely coordination of delivery systems, communications, and data sharing with Yukon First Nations. |

|

|

The responsible Government of Yukon departments identify and report progress on core elements of COVID‑19 vaccine distribution, administration, safety, and effectiveness and on the objectives of Yukon’s COVID‑19 Vaccine Strategy in a way that benefits Yukon residents. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period from 1 March 2020 to 31 October 2022. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 19 May 2023, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

This audit was completed by a multidisciplinary team from across the Office of the Auditor General of Canada led by Glenn Wheeler, Principal. The principal has overall responsibility for audit quality, including conducting the audit in accordance with professional standards, applicable legal and regulatory requirements, and the office’s policies and system of quality management.

Recommendations and Responses

In the following table, the paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report.

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

19. The Department of Health and Social Services, the Department of Community Services, and the Executive Council Office should update their emergency plans so that they complement each other to ensure a prompt and comprehensive response to future health emergencies. |

The 3 departments’ response. Agreed. The Government of Yukon is committed to updating and improving its emergency and pandemic response plans based on lessons learned and best practices developed during this unprecedented public health emergency. In addition, the Government of Yukon has committed to undertaking a legislative review of the Civil Emergency Measures Act and the Public Health and Safety Act to better prepare for future health emergencies. |

|

29. The Department of Health and Social Services should ensure that organizations providing similar services and facing comparable risks of infection should be prioritized for vaccination in an equivalent manner. This prioritization should be included in emergency planning documentation. |

The department’s response. Agreed. The prioritization of front‑line workers providing health and social services will be included in future departmental pandemic planning documentation. |

|

45. For future vaccine rollouts, the Department of Health and Social Services and the Department of Community Services should provide and communicate alternatives to online and phone options for booking services that are as barrier‑free as possible. |

The 2 departments’ response. Agreed. Reducing barriers to access vaccines was, and will remain, a Government of Yukon priority. For future vaccine rollouts, the government will provide and communicate alternatives to online and phone options for booking services. Outreach efforts to reach vulnerable populations, delivering vaccine clinics as close to home as possible, and offering walk‑in appointments as soon as logistically feasible will continue to be part of the government’s vaccine planning and implementation processes. |

|

50. The Department of Health and Social Services should ensure that Yukon‑specific cultural competency training is delivered to those planning and providing front‑line immunization services to better meet First Nations’ needs. |

The department’s response. Agreed. The Government of Yukon is committed to improving cultural competency training for all staff but particularly those planning and providing front‑line immunization services. The Department of Health and Social Services will review and improve existing cultural competency training included in the Yukon Immunization Program’s immunizer certification program. |

|

59. The Department of Health and Social Services and the Department of Community Services, with the support of the Executive Council Office, should partner with Yukon First Nations to outline the expected level and frequency of collaboration during emergencies. This understanding should include clear roles and responsibilities and timing of communications during an emergency situation and should be reflected in emergency plans. |

The 2 departments’ response. Agreed. The Government of Yukon, through the Yukon Emergency Measures Organization, is currently working with municipalities and Yukon First Nation governments to develop emergency management capacity and build emergency-resilient communities. This work includes support for updates to First Nation governments’ emergency coordination plans and support for hazard identification and risk assessments. Clarity on roles and responsibilities, level of engagement, and timing of communications are key elements of this work and the plans being developed. Clear roles and responsibilities and timing of communications during an emergency situation will also be reflected as Government of Yukon emergency plans are updated. |

|

65. The Department of Health and Social Services, with the support of the Executive Council Office, should work with First Nations toward finalizing data‑sharing protocols or agreements to meet the needs of First Nations. |

The department’s response. Agreed. The Government of Yukon is working with, and will continue to work with, interested First Nations toward establishing and finalizing data‑sharing protocols and agreements. |

|

75. The Department of Health and Social Services should develop accurate and comprehensive inventory systems and practices to track vaccine inventory, wastage, and expected coverage. This information should be used for decisions on timing and quantities of vaccine needed and to track the movement of vaccines in real time across the territory. |

The department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Health and Social Services is already in the final stages of implementing a new electronic Inventory Management System, integrated into the existing Panorama information management system, and adds real‑time inventory counts across all facilities that store publicly funded vaccine products. The department will review current methods used to project vaccine uptake and adjust as necessary to improve accuracy of estimates to improve resolution of vaccine product needs. |