2020 February Report of the Auditor General of Canada to the Northwest Territories Legislative Assembly Independent Auditor’s ReportEarly Childhood to Grade 12 Education in the Northwest Territories—Department of Education, Culture and Employment

2020 February Report of the Auditor General of Canada to the Northwest Territories Legislative AssemblyEarly Childhood to Grade 12 Education in the Northwest Territories—Department of Education, Culture and Employment

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- List of Recommendations

- Exhibits:

- 1—Northern Distance Learning program

- 2—Our analysis of 10 years of data shows that students in small communities have lower high school graduation rates

- 3—The department’s calculation overestimated high school graduation rates

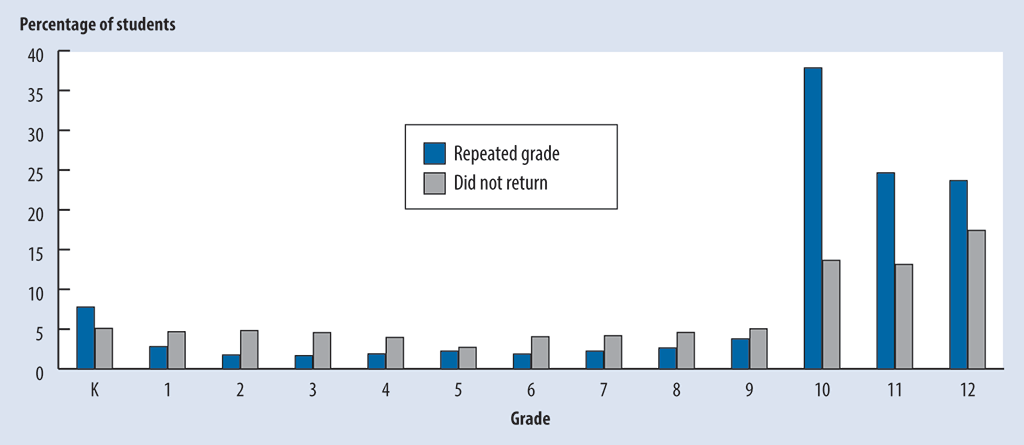

- 4—Percentages of students who repeated grades or did not return to school increased dramatically as of Grade 10

Introduction

Background

1. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment is responsible for the Northwest Territories’ education system from Junior Kindergarten through Grade 12. The system consists of the department and 10 regional education bodies (which are similar to school boards).

2. The department does not deliver services directly to students. That responsibility belongs to the regional education bodies, which employ about 800 educators and oversee operations to deliver education to approximately 8,500 students at 49 schools. In the 2018–19 fiscal year, the department allocated nearly $155 million to the education bodies.

3. The Education Act specifies that students in the Northwest Territories must have access to education programs that meet the highest possible standards and are based on Northwest Territories’ cultures. Students may receive their education in one of the Northwest Territories’ 11 official languages, 9 of which are Indigenous. The act also states that all students are entitled to access education programs in a regular instructional setting in their home communities and receive the support services necessary to do so. The department is responsible for ensuring that all students have equitable access to education programs and services.

4. The department also licenses and supports private daycares, although these are separate from the Junior Kindergarten through Grade 12 education system. High-quality early education and daycare programs delivered by well-trained, knowledgeable educators can help prepare children for success in future school years. As of June 2019, there were 115 licensed daycares, some operating in centres and others in private homes.

5. Delivering education in the Northwest Territories is challenging, partly because of factors beyond the department’s control. The remoteness of many communities and the small size of their schools create significant challenges for offering equitable, inclusive education that incorporates Indigenous language and culture. About 60% of schools have fewer than 150 students, and 8 communities do not offer a high school program. In addition, departmental information indicates that more than one third of students are on individualized learning plans to provide them with additional support. However, it can be difficult for students to access the specialized services they need, particularly in small communities.

6. The department must work within a legislative regime made up of 10 regional education bodies that operate independently of one another and are responsible for decisions about key aspects of education, such as the programs their schools will deliver and hiring school staff. It can be difficult for education bodies to recruit and retain qualified teachers, including those fluent in an official Indigenous language of the Northwest Territories. Also, many communities have limited daycare options, and it can be hard for daycare operators and staff to obtain the required qualifications and training.

7. Education bodies, communities, families, and students play key roles in student outcomes. For example, families contribute to students’ success by ensuring regular attendance and providing a home environment conducive to studying. However, this is not always easy, particularly for Indigenous families struggling with the legacy of residential schools. Although the department is responsible for ensuring that the education system produces the best possible student outcomes, social factors, which were not part of this audit, can influence student outcomes significantly.

8. We audited education in the Northwest Territories for the first time in 2010. That audit identified deficiencies with how the department monitored education bodies and ensured that the system as a whole was working toward improving student outcomes. Our 2010 report also noted a gap in graduation rates between Indigenous and non-Indigenous students.

9. In 2011, the department released its Aboriginal Student Achievement Education Plan. The plan’s aim was to close the achievement gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous students and enable Indigenous youth to lead happy, healthy, prosperous lives as productive community members.

10. According to the department, the plan helped highlight the need for significant changes in the education system. In 2013, the department broadened its focus and released the Education Renewal and Innovation Framework to respond to the need for meaningful and sustainable change throughout the entire education system. The primary goals of this 10-year initiative were to establish an effective, relevant education system for all learners and an associated reporting, management, and accountability framework.

Focus of the audit

11. This audit focused on whether the Department of Education, Culture and Employment planned, supported, and monitored the delivery of equitable, inclusive education programs and services that reflected Indigenous languages and cultures, to support improved student outcomes.

12. We assessed whether the department was meeting its commitment to building a better education system. We examined the department’s actions on selected responsibilities in 4 key educational areas:

- inclusive schooling

- Indigenous language and culture-based education

- equitable access to quality education

- programming, staff qualifications, and training in daycares

We also analyzed selected departmental data.

13. This audit is important because positive education outcomes are important for students’ well-being and future prosperity. Quality education from early childhood to high school is linked to higher employment rates, lower crime rates, and less reliance on social assistance. Furthermore, according to the department, more than three quarters of the jobs that will become available in the Northwest Territories over the next 15 years will require post-secondary education, extensive work experience and seniority, or a combination of all three. Therefore, positive education outcomes are critical to ensuring that Northwest Territories residents can fill the jobs that will become available in their communities in the future.

14. More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, data analysis, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Overall message

15. Overall, we found that the Department of Education, Culture and Employment took steps to plan, support, and monitor the delivery of education programs and services that were equitable, were inclusive, and reflected Indigenous languages and cultures, to support improved student outcomes. However, its actions fell short of meeting all its commitments and obligations, and it did not know whether its efforts were improving student outcomes. For example, we found that the department was slow to fulfill its responsibilities for Indigenous language education. Unfortunately, with every year that passes, Indigenous language proficiency is declining in the territory, increasing the challenge to keep these languages alive.

16. We also found that the department did not determine what needed to be done to ensure that students in small communities had equitable access to education programs and services, compared with students in regional centres and in Yellowknife. Also, it did not take sufficient steps to collect and use data to understand how it might make changes to address persistent gaps in student outcomes.

Planning and supporting the delivery of education

The department did not take sufficient action on key elements of education delivery

17. We found that the Department of Education, Culture and Employment did not take sufficient action to meet its responsibilities and commitments for key elements of education delivery. For example, although it implemented measures that improved equitable access to education programs and services, it did not do enough in this area to meet the additional challenges in small communities.

18. The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

- Slow progress on Indigenous language and culture-based education

- Improved support for inclusive schooling

- Insufficient action on equitable access to quality education

- Challenges related to programming and training for daycares

19. This finding matters because high-quality education programs can have a significant impact on children’s developmental, educational, cultural, emotional, and social outcomes. Planning and supporting the delivery of education are important to help students succeed.

20. Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 27, 34, 45, and 51.

Slow progress on Indigenous language and culture-based education

21. We found that the department was slow to introduce changes in Indigenous language and culture-based education, even though it had been responsible for this area of the education system for decades and had made commitments related to it.

22. After our audit in 2010, the department acknowledged its need to review its policy for Indigenous language and culture-based education. It completed this review in 2014, which found that its model was not leading to fluency for Indigenous students. However, the department issued its new policy only in 2018 and expected education bodies to meet all of the policy’s requirements, including the delivery of mandated curricula, by the 2020–21 school year.

23. In the 1990s, the department developed 2 curricula to support Indigenous culture-based education. However, we found that it did not have a specific curriculum for Indigenous languages until the 2017–18 school year. Prior to this, schools taught Indigenous languages but without a territory-wide curriculum to guide instruction. We found that the department was piloting an Indigenous language curriculum but projected that it would not be fully implemented until the 2020–21 school year.

24. In 2011, the department committed to working with education bodies to increase the number of qualified Indigenous language instructors, as it recognized that there were not enough to deliver Indigenous language education. However, we found that it had not yet collected and analyzed information on how many Indigenous language instructors were required or for which languages. We also found that in 2018, the department began preliminary work with post-secondary institutions on programs to help revitalize Indigenous languages, including through training language instructors. However, there is a risk that these programs will do little to increase the number of qualified language instructors, as the programs target individuals with jobs, including language instructors already teaching in schools.

25. We found that, although progress on Indigenous language education was slow, the department did work to support education bodies. For example, it supported initiatives to incorporate Indigenous cultures into education programming, such as providing cultural orientation for teachers, awareness training for educators on the legacy of residential schools, and an Elders in Schools Program. It also increased its training for some language instructors through the Indigenous language curriculum project that it was piloting.

26. Despite these efforts, we are concerned that the department took too long to improve Indigenous language education. With every year that passes, Indigenous language proficiency in the territory declines. Furthermore, the absence of a territory-wide curriculum over a period of many years meant that students might have missed the opportunity to learn their language in a more structured environment.

27. Recommendation. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment should work with the education bodies to fully implement the Indigenous languages curriculum, and recruit and train the number of required Indigenous language instructors.

The department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment recognizes its role in providing Indigenous language instruction and continues to work with education bodies on the large-scale pilot of the Indigenous languages curriculum, Our Languages, to be completed in the 2019–20 school year when Our Languages will be implemented as a mandatory curriculum. Training for this curriculum is provided annually to education body and school staff through the regional Indigenous language educators and to Indigenous governments through their regional Indigenous language coordinators.

In order to improve the recruitment and training required of Indigenous language instructors, the department is working in partnership with Aurora College and the University of Victoria to deliver a 2-year (2018–19 and 2019–20) pilot Indigenous language revitalization certificate program. In order to improve the recruitment of students into this program, the department is also offering revitalization scholarships to all Northwest Territories students who are taking an Indigenous language–focused program at an accredited college or university.

The department is also implementing a 1-year (2019–20) pilot mentor-apprentice program in partnership with Indigenous governments to provide immersion experiences in which a fluent speaker (the mentor) is paired with a language learner (the apprentice). At the end of their pilot stages, both pilot programs will be evaluated to determine the extent to which the programs are meeting our needs for recruiting and training Indigenous language instructors and adjustments made as necessary.

Improved support for inclusive schooling

28. We found that the Department of Education, Culture and Employment improved its support to education bodies and school staff for delivering inclusive schooling but that more work was required.

29. Inclusive schooling means that all students, regardless of their needs or abilities, can access education programs in a regular instructional setting of their community schools and receive the necessary supports to do so. For students with unique educational needs, school staff must develop individualized learning plans, which outline any supports the students require. These supports can include access to additional education professionals in the classroom and specialist services, such as speech-language pathologists or educational psychologists.

30. We found the department took the following key actions to support inclusive schooling:

- From 2016 to 2018, the department updated its Ministerial Directive on Inclusive Schooling and related guidance. It expected schools to fully comply with the new directive’s requirements starting in the 2018–19 school year.

- Starting in 2016, the department provided new inclusive schooling training to school staff and education bodies. Training included topics such as differentiated instruction, working with students with autism and trauma, and how to develop individualized learning plans.

31. Furthermore, we found that the department took some actions to increase support for specialized services. For example, starting in the 2015–16 school year, the department contracted with a company to provide counselling services to students in several small communities.

32. In 2018, the Department of Education, Culture and Employment also initiated a program with the Department of Health and Social Services to increase the number of mental health and wellness counsellors in schools over a 4-year period. In the same year, the department also began staffing a new team of professionals to help educators implement specialists’ recommendations. The department planned to complete staffing this team by the 2020–21 school year. At the time of our audit, the department had not fully implemented either of these initiatives, and it was too early to know how they might have helped address students’ needs.

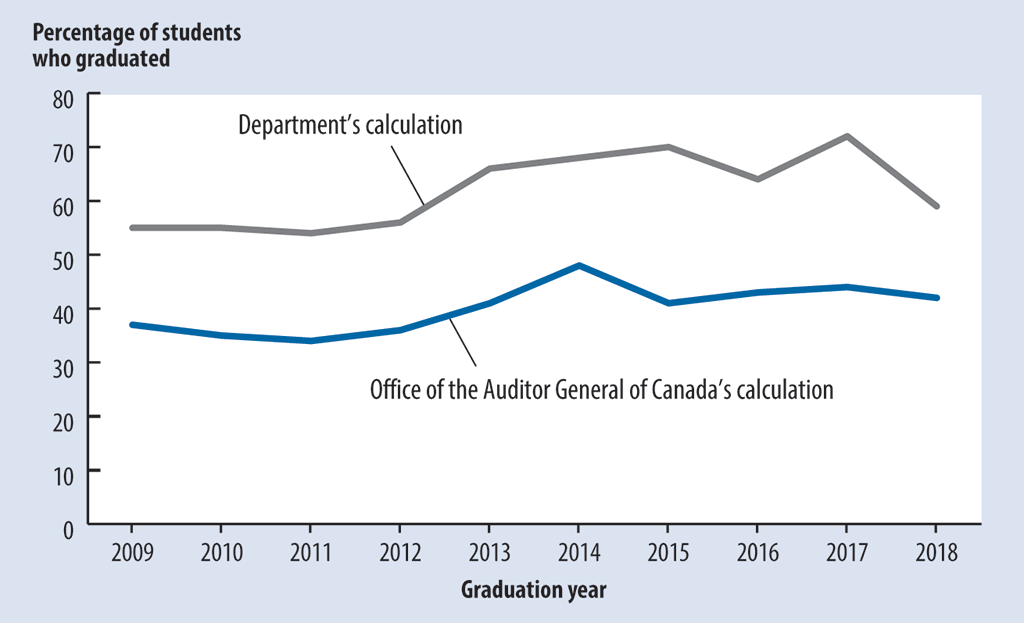

33. Although the department made improvements to support inclusive schooling, we noted challenges that caused us to be concerned that the needs of all students were not being met and that more needed to be done (for example, see paragraphs 60 and 61). This observation is consistent with what department officials told us. Also, the department did not provide adequate guidance and training for support assistants, who are crucial to delivering inclusive schooling by helping teachers meet students’ needs. Support assistants require guidance because they do not need formal qualifications or training for their jobs. We found that, although the department revised its guidance on inclusive schooling, it did not revise its guidance for support assistants, despite committing to do so before the end of the 2016–17 fiscal year.

34. Recommendation. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment should update its guidance for support assistants and provide them with adequate training to help ensure that students’ needs are met.

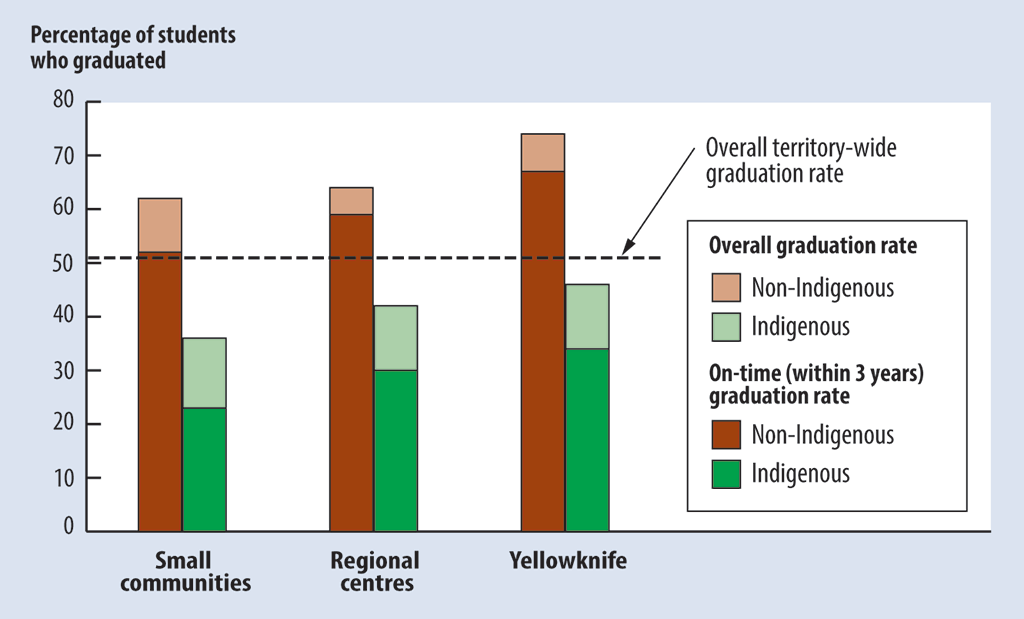

The department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment recognizes that support assistants provide one of many vital roles in meeting students’ needs and is committed to streamlining the ability of students to access these supports.

By 31 March 2020, the department will work with education bodies to update the job descriptions for support assistants, so that the descriptions are consistent across schools. It will also update the Inclusive Schooling Handbook to include a section specific to guiding support assistants in meeting the needs of students in accordance with the Ministerial Directive on Inclusive Schooling.

On an annual cycle, the department will continue to provide in-servicing to program support teachers, so that they are better equipped to train support assistants. The department will also continue working with the education bodies to formalize a tiered training approach for support assistants that can be applied across schools, education bodies, and the department by 31 March 2021. Ongoing professional development through distance learning targeted to the support assistants will also be available through the department’s educator certification and learning management platform.

Insufficient action on equitable access to quality education

35. We found that although the department implemented programs to improve equitable access to quality education, more work was required, such as better support for teachers in multi-grade classrooms.

36. The department is responsible for ensuring that all students across the Northwest Territories have access to the same quality of education, regardless of the location or size of their communities. In 2014, the department reported that more than half of the children in small communities faced challenges that could make learning more difficult for them when they entered the school system.

37. To address this issue, the department piloted a Junior Kindergarten program from 2014 to 2017. It reviewed the pilot and took action on this review’s recommendations when it implemented the program across the territory in the 2017–18 school year. Additional departmental analysis suggested that children who attended Junior Kindergarten during the pilot program scored better on a number of indicators related to developmental readiness for learning.

38. The data from the pilot program was based on results from a small number of children. The department acknowledged that it would need additional data over several more years to know whether the results were conclusive. We agree that this type of analysis would help the department know whether Junior Kindergarten was helping prepare students for future school success.

39. In addition, from 2014 to 2018, the department collaborated with the Beaufort-Delta Education Council to pilot the Northern Distance Learning program for high school students (Exhibit 1). The department’s analysis of the pilot program found that courses taken through this program were about twice as likely to produce passing grades relative to courses taken through online self-study. Between the 2014–15 and 2017–18 school years, 155 students took 445 courses through Northern Distance Learning.

Exhibit 1—Northern Distance Learning program

The Northern Distance Learning program delivers academic courses online to students in small community schools where these courses would otherwise be available only through online self-study courses. Students taking courses through this program participate with other students from across the territory in live, online classes delivered by video link from Inuvik’s East Three Secondary School. Each Northern Distance Learning classroom includes an assistant, helping to create a learning experience that is similar to a student’s regular classroom, even though the students participate remotely from their home communities.

Source: Department of Education, Culture and Employment

40. In the 2018–19 school year, the department launched the program in 11 communities and planned to fully expand it to 20 communities by the 2020–21 school year. At the time of our audit, the department had expanded the program to additional schools according to the timelines in its action plan. However, we found that differences among school calendars within the territory could cause students in some communities to miss Northern Distance Learning classes. In an analysis, the department found that even students who normally had a good rate of school attendance could miss up to 30% of classes as a result of this difference in calendars.

41. The department developed indicators to monitor and report on the program’s performance annually, as ongoing monitoring will be important for the department to know if the program is on track to achieve its intended objective. In addition, the department planned to formally evaluate the program by the end of the 2024–25 fiscal year.

42. We also found that the department adjusted its funding formula to offset the higher cost of living for schools in remote communities and to provide more administrative support to schools. In April 2017, it also began work on an online platform to provide teachers in remote communities with opportunities for development and collaboration. The department anticipated that greater equity in professional opportunities for teachers might help decrease the disparity in student outcomes. This platform was not yet operational at the time of our audit.

43. We found that despite these efforts, the department did not complete some other actions it had committed to, such as to provide additional support to principals of small schools or teachers in multi-grade classrooms. As a result, there was a risk that educators in some communities, especially small ones, could not adequately support all students, and gaps in student achievement would persist.

44. Furthermore, we found that, despite its commitment to ensure equitable access to quality education in all Northwest Territories communities, the department did not explicitly identify the actions required to achieve this commitment. Instead, it asserted that all efforts it undertook as part of the education renewal initiative would address equitable access. The department invested heavily in the Northern Distance Learning and Junior Kindergarten programs; however, these targeted only a small proportion of students in the territory. As a result, there was a risk that although these programs might have improved equitable access for some students, access for others might not have been equitable, especially for those in small or remote communities.

45. Recommendation. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment should identify what is required to provide equitable access to quality education for all students and take action. This should include providing additional supports to principals of small schools and teachers in multi-grade classrooms.

The department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment is cognizant that teaching principals working in small schools or teachers of multi-grade classrooms are limited in the breadth of supports and opportunities they are able to provide to students. To address some of the issues of having lone teachers working in small communities, the department adjusted the school funding framework in the 2019–20 school year to allow education bodies to employ a minimum of 2 teaching positions in all schools.

The department recently conducted a formative (mid-term) evaluation of the Education Renewal and Innovation Framework, which also recommended the need to target initiatives and investments in small communities. In response, the department will address the recommendations from the evaluation as well as this performance audit to assure the actions included in the education renewal action plan for 2020–21 to 2022–23 prioritize supports to small schools and teachers of multi-grade classrooms. One of these actions will include the continued expansion of the Child and Youth Care Counsellor initiative, which is expected to implement 49 new positions (42 counsellor positions and 7 clinical supervisors) by 2021–22.

The department will also begin working with education bodies in the 2019–20 school year to initiate the development of a strategic planning process to outline shared priorities of the education program and define how the selected priorities can be delivered more equitably. The department anticipates that the strategic planning process will be formally rolled out across schools, education bodies, and the department in the 2021–22 school year.

Challenges related to programming and training for daycares

46. The department is responsible for licensing private daycares in the Northwest Territories. Its early childhood consultants inspect daycares annually to ensure that they meet the standards required by the Child Day Care Act and the Child Day Care Standards Regulations. The regulations require daycare operators to provide age-appropriate and culturally appropriate programs that facilitate children’s intellectual, physical, emotional, and social development and encourage language and literacy development, but they do not prescribe learning outcomes for children. The regulations also outline the required qualifications and annual training for daycare operators and staff.

47. In 2013, a departmental handbook provided daycares with information about each of these regulatory requirements, including some related to programming. However, the department recognized the need for additional tools to improve the quality of early childhood development programs. For example, a 2015 departmental report indicated that the territory’s daycare system lacked guidance and programming materials found in other, more mature systems. We found that the department had not provided additional programming guidance to daycares, apart from the 2013 handbook. Department officials told us that they supplemented this guidance through workshops and engaging with daycare operators. However, in our view, it is important that the department provide sufficient guidance to daycare workers and operators, because they can have difficulty obtaining formal training.

48. At the time of our audit, the department was finalizing a territory-wide training plan to support culturally relevant professional development for daycare staff and to increase the number of qualified early childhood development professionals in daycares. Although the plan was not yet completed, the department had already provided some training to its early childhood consultants, who had begun to deliver this training to some daycare operators and staff.

49. The department acknowledged that recruiting qualified daycare staff could be challenging for operators, particularly in remote regions. The regulations allowed daycares to recruit individuals who had not completed a post-secondary program in child development if they could demonstrate to the department a satisfactory understanding of developmentally appropriate practices for children. However, we found that the department did not have a consistent way to assess such individuals. As a result, department officials might have interpreted these regulations inconsistently and might have missed opportunities to recruit or train staff. This result could have affected the quality of programming delivered in daycares.

50. We also looked at how the department tracked compliance with regulations for programming and daycare staff qualifications. The department noted that many daycares faced challenges meeting these requirements; however, we found that it did not track which daycares struggled in these areas. Collecting and consolidating this information would help the department identify where to focus its support for daycare operators and staff when it implements the territorial training plan.

51. Recommendation. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment should do the following:

- Develop guidance that clearly sets out how daycare operators can develop programming that would meet the educational requirements of the Child Day Care Standards Regulations.

- Track daycares’ compliance with programming requirements, track the training needs of daycare operators and staff, and deliver the required training, as appropriate.

- Establish a consistent method of assessing daycare staff and operators who lack formal qualifications to ensure they understand developmentally appropriate child care practices and can apply that understanding to daycare programming.

The department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment acknowledges that the Child Day Care Act allows the Minister to establish regulations enforcing programs of instruction in a daycare facility. However, the department is cognizant that any regulatory approach must also allow operators the flexibility to provide for the variety of family, community, and cultural contexts that they serve, as is the case with Aboriginal Head Start, Montessori Casa, and French First language programs. In order to provide a more standardized approach to early childhood programming for licensed daycares, the department will be piloting the Early Learning Framework with selected daycare operators. The department will review the results of this pilot, at which point it will be better placed to determine if regulatory changes are required, and what compliance mechanisms may be needed. This could include the possibility of linking funding to qualifications of daycare staff and operators as well as programming requirements.

To address the need to track the training needs of daycare operators and staff, the department is working to develop an educator certification and learning management platform, which can track the status of credentials of daycare staff and provide staff with ongoing professional development through distance learning. The department is also addressing the training needs of daycare operators and staff through the annual delivery of the Early Childhood Symposium and through a collaboration with Aurora College, which delivers the Early Learning and Child Care diploma program in Yellowknife.

Monitoring the delivery of education

The department did not adequately monitor the education system

52. We found that the department did not have a clear picture of the performance of the education system, including the department’s progress in renewing the system. The department did not adequately monitor the performance of the education system and had not yet identified the performance measures it would use to do so on an ongoing basis. We found that although the department collected some data on student outcomes, it did limited analysis of this data. For example, its monitoring of inclusive schooling and Indigenous language and culture-based education did not provide sufficient information to assess student outcomes. As a result, the department could not fully assess whether the education system was meeting students’ needs.

53. The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

- Poor monitoring of the education system’s performance

- Problems with data collection and analysis

- Improved monitoring of education bodies’ compliance with policies

54. This finding matters because monitoring the education system helps the department know how well the system is working and where to make changes to improve student outcomes. Without adequate data collection and analysis, the department is at risk of not having the information required to properly monitor the system.

55. Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 62, 63, 64, 65, and 74.

Poor monitoring of the education system’s performance

56. The department is responsible for ensuring that the education system is working optimally. In 2013, it committed to better monitoring the system to support student success. However, we found that it had not yet established a comprehensive monitoring system to do so, as it had still not decided which measures it would use to monitor the system’s performance on an ongoing basis.

57. We also found that the department did not have a comprehensive picture of the overall progress made against its commitments in the 2013 Education Renewal and Innovation Framework, because it did not adequately monitor the action plans it put in place to implement the framework.

58. In 2015, the department created a 3-year action plan that included 18 initiatives with more than 40 deliverables and numerous associated actions. In our opinion, the plan was ambitious, as were subsequent plans. Department officials told us that accomplishing the work required under these plans was unrealistic given the resources available. We found that department officials tracked and reported progress to senior management on some actions for which they were responsible. We expected that the department would also have a way to know its overall progress on implementing the action plans, especially as they were so ambitious; however, it did not. We found that, at the time of our audit, the department was working on a mid-term evaluation of progress against the framework’s commitments, but it did not finish the evaluation by June 2019, as it had planned to do.

59. Furthermore, we found that the department did not sufficiently measure the performance of Indigenous language and culture-based education or inclusive schooling over the period of our audit. For example, it did not assess the effectiveness of the curricula developed for culture-based education. It also did not know whether students were becoming proficient in their Indigenous languages. This is a problem, especially since the department found in 2014 that its model for language instruction was not leading to fluency, as noted in paragraph 22.

60. In addition, we found that the department did not sufficiently monitor whether schools were creating, monitoring, and updating individualized learning plans for students, as required by the Ministerial Directive on Inclusive Schooling. Its monitoring of inclusive schooling did not provide it with sufficient information about whether students on individualized learning plans received the necessary supports, including specialized services, or how this affected their outcomes. This meant that there was a risk that students were not benefiting fully from these plans.

61. Finally, we found that although the department drafted a detailed monitoring plan in 2015 for how it would measure the success of inclusive schooling, it never implemented this plan. Part of this plan was to conduct school reviews, but we found that it still had not determined what these reviews would entail or who was responsible for conducting them. At the time of our audit, the department had not completed any school reviews.

62. Recommendation. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment should develop and use performance measures that adequately measure the performance of the education system on an ongoing basis and should make the necessary modifications to its programs and services.

The department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment recognizes its responsibility for monitoring the performance of the education system and in 2019 established the Planning and Accountability Framework for the Junior Kindergarten to Grade 12 Education System. Through the framework, education bodies are expected to set and report on targets toward specific performance measures through their annual planning and reporting process. Each year, the education bodies use the information from their annual reports to inform the following year’s operating plans.

The planning and accountability framework also establishes a set of outcome-oriented performance measures for the education system, including graduation rates, which will be reported on annually, as data becomes available. The framework also requires the department to analyze all of the information gathered from the education bodies as well as the outcome-oriented performance measurement data every 5 years in order to fully understand the education system’s progress. In 2019–20, this comprehensive review took place for the first time with the formative (mid-term) evaluation of the Education Renewal and Innovation Framework. The department will address the recommendations from the evaluation as well as this performance audit to assure the actions included in the education renewal action plan for 2020–21 to 2022–23 prioritize those actions that are targeted toward decreasing the achievement gaps in the education system.

63. Recommendation. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment should complete the mid-term evaluation of the Education Renewal and Innovation Framework and refocus its efforts on actions that it should prioritize in the final years of the framework.

The department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment has completed the mid-term evaluation of the Education Renewal and Innovation Framework. Similar to the recommendation of this performance audit, a key recommendation stemming from the mid-term evaluation also requires the department to decrease the number of initiatives being undertaken and to prioritize those that would focus on small communities and closing achievement gaps.

To address the recommendations from the evaluation as well as this performance audit, the department will prioritize those actions in the final years of the framework that provide supports to small schools and teachers of multi-grade classrooms. Prioritizing the actions will also take into consideration the shared priorities of the education program that are being developed between the education bodies and the department and define how they can be delivered more equitably.

64. Recommendation. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment should monitor student progress on Indigenous language acquisition, assess the adequacy of its curricula for culture-based education, and adjust its approach as needed.

The department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment is in the process of bringing the Our Languages curriculum into full implementation, which includes the development of an oral proficiency assessment tool. The assessment tool will provide evidence of a student’s progression and will be piloted across selected schools in the 2019–20 school year. A review of the pilot will determine where adjustments to the assessment tool may be necessary.

Through the Planning and Accountability Framework for the Junior Kindergarten to Grade 12 Education System, education bodies are expected to set and report on targets toward specific performance measures through their annual planning and reporting process. Some of the performance measures are focused specifically on the Indigenous Languages and Education Policy as it relates to the school funding framework requirements. Each year, the education bodies use the information from their annual reports to inform the following year’s operating plans.

The planning and accountability framework also established a set of outcome-oriented performance measures for the education system, including measures specific to culture, identity, and well-being. In order to fully understand the education system’s progress, the department will conduct a comprehensive review every 5 years. In 2019–20, this comprehensive review took place for the first time with the formative (mid-term) evaluation of the Education Renewal and Innovation Framework, in which a case study was conducted specific to the Our Languages curriculum. The department will be applying the recommendations from the case study results and this performance audit to adjust its approach as necessary.

65. Recommendation. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment should strengthen its monitoring of inclusive schooling. This should include

- conducting reviews of inclusive schooling practices, including spot checks on individualized learning plans

- analyzing information (including information related to students’ needs for specialist services) to assess whether students’ needs are being met

- making necessary adjustments to the education system

The department’s response. Agreed. Through the Planning and Accountability Framework for the Junior Kindergarten to Grade 12 Education System, the education bodies are expected to set and report on targets toward specific performance measures through their annual planning and reporting process. This process includes performance measures specific to the Ministerial Directive on Inclusive Schooling as it relates to the school funding framework requirements. Each year, the education bodies use the information from their annual reports to inform the following year’s operating plans.

The planning and accountability framework also establishes a set of outcome-oriented performance measures for the education system, including those specific to individualized education plans and student support plans. In order to fully understand the education system’s progress, the Department of Education, Culture and Employment will conduct a comprehensive review every 5 years. In 2019–20, this comprehensive review took place for the first time with the formative (mid-term) evaluation of the Education Renewal and Innovation Framework, in which performance data related to individualized education plans and student support plans were analyzed.

While there is a key focus on monitoring inclusive schooling through the planning and accountability framework, the department recognizes the need to strengthen this monitoring to be able to formally assess whether students’ needs are being met and making adjustments as necessary. The department commits to conducting a review of inclusive schooling practices as part of its next comprehensive review of the education system, scheduled to take place in 2023 as part of its planning and accountability framework cycle.

Problems with data collection and analysis

66. We found that the department collected and analyzed student data such as whether students graduated, their attendance, and their results on standardized tests. However, it collected limited information on other outcomes, such as the performance of students on individualized learning plans and whether high school graduates went to college or university.

67. We also found that the department stopped collecting some territory-wide information about students’ academic performance. It stopped administering Grade 3 standardized testing in 2014 and stopped collecting information about students’ functional grade levelsDefinition i in 2016. We are concerned that, until the department decides what other data to collect and begins collecting it, little territory-wide data will be available, particularly for the early years of schooling.

68. We also found problems with the department’s analysis of some of the information that it collected. In 2013, it put forward a business case for a new electronic data system to improve its ability to measure, analyze, and report on its programs and services, including the Junior Kindergarten through Grade 12 education programs. However, we found that at the time of our audit, the department did not plan for this platform to support the analysis of all key student information, such as that related to individualized learning plans. This platform was supposed to be active as of June 2019, but it was still being developed at the time of our audit.

69. Furthermore, we found that the method the department used to calculate high school graduation rates painted an overly positive picture. The department’s method was to divide the number of graduates by the number of 18-year-olds in the territory in a given year. Department officials recognized that there were problems with this method, and they were working on an alternate one.

70. We analyzed 10 years of departmental data using a different method, similar to that used by the majority of jurisdictions across Canada. Our analysis followed cohorts of students from grades 10 to 12 and included students who left school prior to Grade 12. We found that graduation rates were significantly lower than those reported by the department. For example, the department’s method resulted in a reported graduation rate of 72% in 2017, while our calculations resulted in a graduation rate of 44% (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2—The department’s calculation overestimated high school graduation rates

Source: Based on data from the Department of Education, Culture and Employment (unaudited)

Exhibit 2—text version

This line chart shows the department’s calculation and the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s calculation of high school graduation rates from the 2009 to the 2018 graduation year.

The first line shows the department calculated that the high school graduation rate was about 55% in the 2009 graduation year, rose to about 70% in 2017, and decreased to about 60% in 2018.

The second line shows the Office of the Auditor General of Canada calculated that the high school graduation rate was just below 40% in the 2009 graduation year, rose to close to 50% in 2014, and decreased to about 40% in 2018.

Source: Based on data from the Department of Education, Culture and Employment (unaudited)

71. We also used the graduation rates we calculated to compare the time it took students in communities of different sizes to graduate (either on time, within the typical 3-year period, or at any point during our 10-year time frame). We found that, consistent with departmental information, students in small communities had lower graduation rates than their peers in regional centres and Yellowknife. Overall, we found that from 2009 to 2018, about 50% of students graduated (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3—Our analysis of 10 years of data shows that students in small communities have lower high school graduation rates

Source: Based on data from the Department of Education, Culture and Employment for the years 2009 to 2018 (unaudited)

Exhibit 3—text version

This bar chart shows the percentage of students who graduated between the 2009 and 2018 graduation years who were Indigenous and non-Indigenous, and in small communities, regional centres, and Yellowknife.

The overall territory-wide graduation rate in that 10-year period was just over 50%.

In small communities, among non-Indigenous students, just over 60% graduated overall, and just over 50% graduated on time, within 3 years. Among Indigenous students, about 35% graduated overall, and just over 20% graduated within 3 years.

In regional centres, among non-Indigenous students, about 65% graduated overall, and just under 60% graduated on time, within 3 years. Among Indigenous students, about 40% graduated overall, and about 30% graduated within 3 years.

In Yellowknife, among non-Indigenous students, about 75% graduated overall, and almost 70% graduated within 3 years. Among Indigenous students, about 45% graduated overall, and about 35% graduated within 3 years.

Source: Based on data from the Department of Education, Culture and Employment for the years 2009 to 2018 (unaudited)

72. Finally, in our analysis of student data, we found that the percentage of students either repeating grades or not returning to school increased dramatically for students as of Grade 10, the year in which “social passing” is no longer an option (Exhibit 4). Social passing is the practice of placing students in a higher grade with their age peers rather than holding them back, even when they have not satisfied a grade’s academic requirement. For this practice to be effective, students must be sufficiently supported, so that they can be adequately prepared for high school.

Exhibit 4—Percentages of students who repeated grades or did not return to school increased dramatically as of Grade 10

Source: Based on data from the Department of Education, Culture and Employment for the years 2008 to 2017 (unaudited)

Exhibit 4—text version

This bar chart shows the percentage of students in each grade, from Kindergarten to Grade 12, who repeated the grade or did not return to school, for the years 2008 to 2017.

In Kindergarten, about 8% of students repeated and 5% did not return.

In Grades 1 to 9, in each year, about 2 to 4% of students repeated the grade and about 3 to 5% did not return.

In Grade 10, about 38% of students repeated the grade and 14% did not return.

In Grade 11, about 25% of students repeated the grade and 13% did not return.

In Grade 12, about 24% of students repeated the grade and 17% did not return.

Source: Based on data from the Department of Education, Culture and Employment for the years 2008 to 2017 (unaudited)

73. Although the department had some information indicating the trends in student outcomes that our analyses revealed, in our view, more detailed analyses could help the department better understand the actions it could take to help improve student outcomes.

74. Recommendation. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment should do the following:

- Use a more valid method to calculate graduation rates.

- Identify, collect, and analyze the data required to adequately measure student outcomes so that it can identify necessary changes to the education system.

- Make the changes that it has identified through data analysis.

The department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment recognizes its responsibility for monitoring the performance of the education system and established a Planning and Accountability Framework for the Junior Kindergarten to Grade 12 Education System in 2019. This framework outlined annual planning and reporting requirements for education bodies against a set of performance measures and also established a set of outcome-oriented performance measures for the education system. It is through the establishment of these outcome-oriented performance measures that the department recognized the need to revise its graduation rate methodology, so that it could consider a methodology that was more precise and did not fluctuate based on changes in the Northwest Territories population.

In order to fully understand the education system’s progress, the framework also requires the department to analyze all the information gathered from the education bodies as well as the outcome-oriented performance measurement data every 5 years. In 2019–20, this comprehensive review took place for the first time with the formative (mid-term) evaluation of the Education Renewal and Innovation Framework. The department will address the recommendations from the evaluation as well as this performance audit to assure the actions included in the education renewal action plan for 2020–21 to 2022–23 prioritize those actions that are targeted toward providing more supports to teaching principals and teachers of multi-grade classrooms and decreasing the achievement gaps in the education system through initiatives like High School Pathways.

Improved monitoring of education bodies’ compliance with policies

75. We found that the department improved its monitoring of education bodies’ compliance with departmental policies since we audited education in 2010. The Education Accountability Framework, developed in 2016, was meant to help ensure that the activities of the education bodies met policy requirements. This framework required each education body to develop an annual operating plan and submit an annual report.

76. We found that all education bodies submitted their operating plans and annual reports to the department starting in the 2017–18 school year. The documents included information to demonstrate how the education bodies had used their budgets, including that they had used funding for the intended purposes. They also reported their progress on their priorities for the school year, such as specific cultural activities they had introduced in their schools or training they had provided to help teachers support student wellness. This represented a significant improvement in how the department was holding the education bodies accountable.

Conclusion

77. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment took steps to plan, support, and monitor the delivery of equitable, inclusive education programs and services that reflected Indigenous languages and cultures, to support improved student outcomes. However, we concluded that these actions were insufficient for it to fully meet its commitments and obligations. Providing sufficient support in key areas, such as Indigenous language and culture-based education, and monitoring the outcomes of its education programs are necessary to help ensure that students in the territory are being given the best chance for success.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on education from early childhood to Grade 12 in the Northwest Territories. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist the Legislative Assembly of the Northwest Territories in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs, and to conclude on whether the Department of Education, Culture and Employment complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada applies the Canadian Standard on Quality Control 1 and, accordingly, maintains a comprehensive system of quality control, including documented policies and procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether the Department of Education, Culture and Employment planned, supported, and monitored the delivery of equitable, inclusive education programs and services that reflected Indigenous languages and cultures, to improve student outcomes.

Scope and approach

The audit focused on early childhood to Grade 12 education in the Northwest Territories. Specifically, we examined whether the Department of Education, Culture and Employment met key responsibilities related to inclusive schooling, Indigenous languages and culture-based education, equitable access to quality education, daycares, planning for and measuring the effectiveness of the education system, and implementation of key elements of the Education Renewal and Innovation Framework.

The audit approach included visits to education bodies and schools, as well as interviews with education body and school staff, and other stakeholders.

The audit involved reviewing and analyzing documents from the Department of Education, Culture and Employment. We also analyzed 10 years of departmental data, including on student outcomes, using the Grade 10 enrollment year as the basis to create cohort groups. A cohort group represents the collective of all students who first enrolled in a specific grade, in our case Grade 10, in a given year. This allowed us to track 3-year graduation rates and provided a basis for other comparisons.

We did not look at the performance of education bodies or child daycare facility operators (including teaching quality) as we did not have the mandate to audit them. Neither did we assess health and safety in child daycares and schools, school infrastructure, adult and post-secondary education, private schools, or homeschooling. We also did not examine the performance of teachers or the quality of education programming in schools or daycares.

Criteria

We used the following criteria to determine whether the Department of Education, Culture and Employment planned, supported, and monitored the delivery of equitable, inclusive education programs and services that reflected Indigenous languages and cultures, to improve student outcomes:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

The Department of Education, Culture and Employment ensures equitable access to inclusive early learning programs and services that are reflective of the languages and cultures of the Northwest Territories. |

|

|

The Department of Education, Culture and Employment ensures equitable access to inclusive elementary and secondary education programs and services that are reflective of the languages and cultures of the Northwest Territories. |

|

|

The Department of Education, Culture and Employment monitors student outcomes, assesses the education system, and takes action to improve student outcomes, including closing key gaps in student achievement. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period from 1 April 2015 to 31 May 2019. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies. However, to gain a more complete understanding of the subject matter of the audit, we also examined certain matters that preceded the start date of this period.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 27 November 2019, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

Principal: Glenn Wheeler

Director: Maria Pooley

Alexandre Boucher

Makeddah John

List of Recommendations

The following table lists the recommendations and responses found in this report. The paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report, and the numbers in parentheses indicate the location of the related discussion.

Planning and supporting the delivery of education

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

27. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment should work with the education bodies to fully implement the Indigenous languages curriculum, and recruit and train the number of required Indigenous language instructors. (21 to 26) |

The department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment recognizes its role in providing Indigenous language instruction and continues to work with education bodies on the large-scale pilot of the Indigenous languages curriculum, Our Languages, to be completed in the 2019–20 school year when Our Languages will be implemented as a mandatory curriculum. Training for this curriculum is provided annually to education body and school staff through the regional Indigenous language educators and to Indigenous governments through their regional Indigenous language coordinators. In order to improve the recruitment and training required of Indigenous language instructors, the department is working in partnership with Aurora College and the University of Victoria to deliver a 2-year (2018–19 and 2019–20) pilot Indigenous language revitalization certificate program. In order to improve the recruitment of students into this program, the department is also offering revitalization scholarships to all Northwest Territories students who are taking an Indigenous language–focused program at an accredited college or university. The department is also implementing a 1-year (2019–20) pilot mentor-apprentice program in partnership with Indigenous governments to provide immersion experiences in which a fluent speaker (the mentor) is paired with a language learner (the apprentice). At the end of their pilot stages, both pilot programs will be evaluated to determine the extent to which the programs are meeting our needs for recruiting and training Indigenous language instructors and adjustments made as necessary. |

|

34. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment should update its guidance for support assistants and provide them with adequate training to help ensure that students’ needs are met. (28 to 33) |

The department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment recognizes that support assistants provide one of many vital roles in meeting students’ needs and is committed to streamlining the ability of students to access these supports. By 31 March 2020, the department will work with education bodies to update the job descriptions for support assistants, so that the descriptions are consistent across schools. It will also update the Inclusive Schooling Handbook to include a section specific to guiding support assistants in meeting the needs of students in accordance with the Ministerial Directive on Inclusive Schooling. On an annual cycle, the department will continue to provide in-servicing to program support teachers, so that they are better equipped to train support assistants. The department will also continue working with the education bodies to formalize a tiered training approach for support assistants that can be applied across schools, education bodies, and the department by 31 March 2021. Ongoing professional development through distance learning targeted to the support assistants will also be available through the department’s educator certification and learning management platform. |

|

45. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment should identify what is required to provide equitable access to quality education for all students and take action. This should include providing additional supports to principals of small schools and teachers in multi-grade classrooms. (35 to 44) |

The department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment is cognizant that teaching principals working in small schools or teachers of multi-grade classrooms are limited in the breadth of supports and opportunities they are able to provide to students. To address some of the issues of having lone teachers working in small communities, the department adjusted the school funding framework in the 2019–20 school year to allow education bodies to employ a minimum of 2 teaching positions in all schools. The department recently conducted a formative (mid-term) evaluation of the Education Renewal and Innovation Framework, which also recommended the need to target initiatives and investments in small communities. In response, the department will address the recommendations from the evaluation as well as this performance audit to assure the actions included in the education renewal action plan for 2020–21 to 2022–23 prioritize supports to small schools and teachers of multi-grade classrooms. One of these actions will include the continued expansion of the Child and Youth Care Counsellor initiative, which is expected to implement 49 new positions (42 counsellor positions and 7 clinical supervisors) by 2021–22. The department will also begin working with education bodies in the 2019–20 school year to initiate the development of a strategic planning process to outline shared priorities of the education program and define how the selected priorities can be delivered more equitably. The department anticipates that the strategic planning process will be formally rolled out across schools, education bodies, and the department in the 2021–22 school year. |

|

51. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment should do the following:

|

The department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment acknowledges that the Child Day Care Act allows the Minister to establish regulations enforcing programs of instruction in a daycare facility. However, the department is cognizant that any regulatory approach must also allow operators the flexibility to provide for the variety of family, community, and cultural contexts that they serve, as is the case with Aboriginal Head Start, Montessori Casa, and French First language programs. In order to provide a more standardized approach to early childhood programming for licensed daycares, the department will be piloting the Early Learning Framework with selected daycare operators. The department will review the results of this pilot, at which point it will be better placed to determine if regulatory changes are required, and what compliance mechanisms may be needed. This could include the possibility of linking funding to qualifications of daycare staff and operators as well as programming requirements. To address the need to track the training needs of daycare operators and staff, the department is working to develop an educator certification and learning management platform, which can track the status of credentials of daycare staff and provide staff with ongoing professional development through distance learning. The department is also addressing the training needs of daycare operators and staff through the annual delivery of the Early Childhood Symposium and through a collaboration with Aurora College, which delivers the Early Learning and Child Care Diploma program in Yellowknife. |

Monitoring the delivery of education

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

62. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment should develop and use performance measures that adequately measure the performance of the education system on an ongoing basis and should make the necessary modifications to its programs and services. (56 to 61) |

The department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment recognizes its responsibility for monitoring the performance of the education system and in 2019 established the Planning and Accountability Framework for the Junior Kindergarten to Grade 12 Education System. Through the framework, education bodies are expected to set and report on targets toward specific performance measures through their annual planning and reporting process. Each year, the education bodies use the information from their annual reports to inform the following year’s operating plans. The planning and accountability framework also establishes a set of outcome-oriented performance measures for the education system, including graduation rates, which will be reported on annually, as data becomes available. The framework also requires the department to analyze all of the information gathered from the education bodies as well as the outcome-oriented performance measurement data every 5 years in order to fully understand the education system’s progress. In 2019–20, this comprehensive review took place for the first time with the formative (mid-term) evaluation of the Education Renewal and Innovation Framework. The department will address the recommendations from the evaluation as well as this performance audit to assure the actions included in the education renewal action plan for 2020–21 to 2022–23 prioritize those actions that are targeted toward decreasing the achievement gaps in the education system. |

|

63. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment should complete the mid-term evaluation of the Education Renewal and Innovation Framework and refocus its efforts on actions that it should prioritize in the final years of the framework. (56 to 61) |

The department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment has completed the mid-term evaluation of the Education Renewal and Innovation Framework. Similar to the recommendation of this performance audit, a key recommendation stemming from the mid-term evaluation also requires the department to decrease the number of initiatives being undertaken and to prioritize those that would focus on small communities and closing achievement gaps. To address the recommendations from the evaluation as well as this performance audit, the department will prioritize those actions in the final years of the framework that provide supports to small schools and teachers of multi-grade classrooms. Prioritizing the actions will also take into consideration the shared priorities of the education program that are being developed between the education bodies and the department and define how they can be delivered more equitably. |

|

64. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment should monitor student progress on Indigenous language acquisition, assess the adequacy of its curricula for culture-based education, and adjust its approach as needed. (56 to 61) |

The department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment is in the process of bringing the Our Languages curriculum into full implementation, which includes the development of an oral proficiency assessment tool. The assessment tool will provide evidence of a student’s progression and will be piloted across selected schools in the 2019–20 school year. A review of the pilot will determine where adjustments to the assessment tool may be necessary. Through the Planning and Accountability Framework for the Junior Kindergarten to Grade 12 Education System, education bodies are expected to set and report on targets toward specific performance measures through their annual planning and reporting process. Some of the performance measures are focused specifically on the Indigenous Languages and Education Policy as it relates to the school funding framework requirements. Each year, the education bodies use the information from their annual reports to inform the following year’s operating plans. The planning and accountability framework also established a set of outcome-oriented performance measures for the education system, including measures specific to culture, identity, and well-being. In order to fully understand the education system’s progress, the department will conduct a comprehensive review every 5 years. In 2019–20, this comprehensive review took place for the first time with the formative (mid-term) evaluation of the Education Renewal and Innovation Framework, in which a case study was conducted specific to the Our Languages curriculum. The department will be applying the recommendations from the case study results and this performance audit to adjust its approach as necessary. |

|

65. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment should strengthen its monitoring of inclusive schooling. This should include

|

The department’s response. Agreed. Through the Planning and Accountability Framework for the Junior Kindergarten to Grade 12 Education System, the education bodies are expected to set and report on targets toward specific performance measures through their annual planning and reporting process. This process includes performance measures specific to the Ministerial Directive on Inclusive Schooling as it relates to the school funding framework requirements. Each year, the education bodies use the information from their annual reports to inform the following year’s operating plans. The planning and accountability framework also establishes a set of outcome-oriented performance measures for the education system, including those specific to individualized education plans and student support plans. In order to fully understand the education system’s progress, the Department of Education, Culture and Employment will conduct a comprehensive review every 5 years. In 2019–20, this comprehensive review took place for the first time with the formative (mid-term) evaluation of the Education Renewal and Innovation Framework, in which performance data related to individualized education plans and student support plans were analyzed. While there is a key focus on monitoring inclusive schooling through the planning and accountability framework, the department recognizes the need to strengthen this monitoring to be able to formally assess whether students’ needs are being met and making adjustments as necessary. The department commits to conducting a review of inclusive schooling practices as part of its next comprehensive review of the education system, scheduled to take place in 2023 as part of its planning and accountability framework cycle. |

|

74. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment should do the following:

|

The department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Education, Culture and Employment recognizes its responsibility for monitoring the performance of the education system and established a Planning and Accountability Framework for the Junior Kindergarten to Grade 12 Education System in 2019. This framework outlined annual planning and reporting requirements for education bodies against a set of performance measures and also established a set of outcome-oriented performance measures for the education system. It is through the establishment of these outcome-oriented performance measures that the department recognized the need to revise its graduation rate methodology, so that it could consider a methodology that was more precise and did not fluctuate based on changes in the Northwest Territories population. In order to fully understand the education system’s progress, the framework also requires the department to analyze all the information gathered from the education bodies as well as the outcome-oriented performance measurement data every 5 years. In 2019–20, this comprehensive review took place for the first time with the formative (mid-term) evaluation of the Education Renewal and Innovation Framework. The department will address the recommendations from the evaluation as well as this performance audit to assure the actions included in the education renewal action plan for 2020–21 to 2022–23 prioritize those actions that are targeted toward providing more supports to teaching principals and teachers of multi-grade classrooms and decreasing the achievement gaps in the education system through initiatives like High School Pathways. |