Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable DevelopmentBiodiversity in Canada: Commitments and Trends

Introduction

Purpose of this backgrounder

In light of the United Nations–recognized emergency facing the world’s biodiversity, the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, on behalf of the Auditor General of Canada, plans to release several performance audits related to biodiversity, between 2022 and 2024. This backgrounder provides general information on Canada’s commitments to biodiversity protection and specifically on the status and trends of species at risk as background to the performance audit reports on specific biodiversity topics.

What is biodiversity?

Biological diversity, or biodiversity, is the variety among living things. It operates at 3 fundamental levels—genes, species, and ecosystems:

- Genetic diversity is the variety within the gene pool of a species. Each individual in a species has its own genetic makeup, which can be expressed through differences in behaviour and appearance. The more genetically diverse a species or population is, the greater will be its ability to adapt to changes in the environment. Lack of genetic diversity—for example, in the monocultures on which modern farming often relies—increases vulnerability to disease, parasites, and other threats.

- Species diversity is the number of species in a given area. Scientists have formally described approximately 1.7 million living species. Scientists with the United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre suggest that these make up less than a quarter of the species on our planet.

- Ecosystem diversity is the variety of ecosystems in a particular area. It includes the variation of biological communities, habitat diversity, and ecological processes. How the boundaries of ecosystems are defined depends on the scale. For example, the relevant habitat for a frog population may be defined as the pond and shore areas inhabited by the frogs, while the relevant habitat for a population of woodland caribou may include the same pond and vast areas of surrounding forest, wetlands, and other freshwater bodies frequented by the caribou.

Importance of biodiversity

A diverse mix of genes, species, and ecosystems make human survival possible. Biodiversity underpins

- the provision of goods consumed directly or used as economic inputs, such as food, medicine, fresh water, and wood products

- the regulation of the climate and air and water quality, and the mitigation of drought and flooding

- recreation, aesthetic enjoyment, and spiritual fulfillment

- other benefits, including soil formation, nutrient cycling, and oxygen production (for example, at least half of the oxygen we breathe comes from photosynthesis by marine plants)

Threats to biodiversity

The United Nations recognizes biodiversity loss as one of the world’s most pressing emergencies, along with pollution and climate change. In 2021, the United Nations Environment Programme stated the following in its Making Peace with Nature report:

Species are currently going extinct tens to hundreds of times faster than the natural background rate. One million of the world’s estimated 8 million species of plants and animals are threatened with extinction. The population sizes of wild vertebrates have dropped by an average of 68 per cent in the last 50 years, and the abundance of many wild insect species has fallen by more than half. … Ecosystems are degrading at an unprecedented rate, driven by land-use change, exploitation, climate change, pollution and invasive alien species. Climate change exacerbates other threats to biodiversity, and many plant and animal species have already experienced changes in their range, abundance and seasonal activity. Degradation of ecosystems is impacting their functions and harming their ability to support human well-being. Loss of biodiversity is anticipated to accelerate in coming decades, unless actions to halt and reverse human transformation and degradation of ecosystems and to limit climate change are urgently implemented.

Likewise, the 2021–22 Global Risks Perception Survey, conducted by the World Economic Forum, identified biodiversity loss as the third-most severe global risk over the next 10 years.

There are 5 principal threats to biodiversity:

- Habitat loss and degradation is the primary threat to biodiversity, in Canada and globally. They are the result of the conversion of natural ecosystems to new uses, including residential, agricultural, commercial, and industrial development. Habitat degradation can include the loss or disruption of natural processes, such as fire or water-level fluctuations. As habitats are lost, fragmented, or degraded, they become less able to support the full complement of native species that rely on them.

- Invasive alien species can include plants, animals, and diseases that can outcompete or kill native species and destroy or alter habitat. When they affect commercially valuable or culturally important species, they can cause significant harm to local economies and livelihoods.

- Overexploitation reduces populations of species and can lead to changes in species’ characteristics, such as smaller average body sizes. Industrial overexploitation is a particular threat to marine fish. For example, it contributed to the collapse of Atlantic Canada’s cod fishery in the 1990s.

- Pollution can kill species, reduce their health, and affect their reproductive ability. Pollution also degrades habitat and causes changes in the mix of species. For example, nutrient runoff into water promotes the growth of harmful algae and bacteria, which in turn can affect water quality, species composition, and resource availability.

- Climate change affects biodiversity by altering the environmental conditions that species have evolved or adapted to rely on. The effects can vary, depending on the region and the ability of species to adapt to changing conditions. Higher temperatures may lead to shifts in the habitats where a species can survive—or the outright loss of those habitats. Climate-induced changes to the timing of plant flowering may also affect food availability and migration patterns.

Biodiversity in Canada

Canada is home to an estimated 80,000 species, including mammals, birds, fish, plants, amphibians, reptiles, and insects. Species such as caribou, polar bears, beavers, and loons are depicted on Canadian coins and are among the most widely recognized species in the country. More than 300 species are found exclusively in Canada. Unfortunately, some of Canada’s species that were once quite common, such as bison, Atlantic cod, and the monarch butterfly, have declined drastically to the point that they are at risk. What was once North America’s most common bird, the passenger pigeon, is extinct.

Plants and animals in Canada are dispersed across various landscapes and ecosystems: forests, grasslands, wetlands, lakes and rivers, coastal ecosystems, oceans, and ice. The greatest diversity of species is in the south, where most Canadians live. However, other areas of Canada maintain extensive intact habitats of global significance. Canada has approximately 24% of the world’s boreal forests and about 25% of the world’s temperate forests. Canada’s 1.5 million square kilometres of wetlands make up about 25% of the world’s total. Canada also has the world’s longest coastline, 2 million lakes, and the third-largest area of glaciers in the world.

Biodiversity in Canada is at risk, with thousands of species in danger of disappearing. The national conservation status of species at risk is assessed by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, which sets out several risk categories:

- Not at risk: evaluated and found not to be at risk of extinction given the current circumstances

- Special concern: may become threatened or endangered because of a combination of biological characteristics and identified threats

- Threatened: likely to become endangered if nothing is done to reverse the factors leading to its extirpation or extinction

- Endangered: faces imminent extirpation or extinction

- Extirpated: no longer exists in the wild in Canada, but exists elsewhere

- Extinct: no longer exists

As part of the process for identifying species at risk, the National General Status Working Group, a joint federal–provincial–territorial body, prepares a regular report on the status of all wild species in Canada. Species that are ranked as “may be at risk” are prioritized for assessment by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, which advises the federal government about species that should be listed under the Species at Risk Act. The Minister of Environment and Climate Change makes a recommendation to the Governor in CouncilFootnote 1 as to which species should be listed under the act.

Species that are extinct or in decline in Canada

Tragically, some species have become extinct in Canada. Other species are in decline and are endangered or have threats that have increased their risk of extinction (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1—Examples of species that are extinct or whose risk has increased

| Species | Risk category by year | Status history |

|---|---|---|

|

Atlantic salmon, Lake Ontario population

Photo: slowmotiongli/Shutterstock.com |

Extirpated Extinct |

Once abundant in the Lake Ontario watershed, the Lake Ontario population of Atlantic salmon became extinct by the end of the 19th century because of overfishing, habitat degradation, and dams that blocked spawning runs. While there are ongoing efforts to bring Atlantic salmon back to Lake Ontario, the reintroduced stock is not part of the genetic stock native to the lake. |

|

Passenger pigeon

Illustration: Nicolas Primola/ |

Extinct |

The passenger pigeon is perhaps the best known of Canada’s extinct species. It once ranged over large areas of southeastern Canada and numbered in the billions, but its numbers were sharply reduced by market hunting and habitat loss. It was last recorded in Canada in 1902 at Penetanguishene, Ontario, and became extinct in 1914. The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada formally assessed the passenger pigeon as extinct in 1985. |

|

American chestnut

Photo: Gabriela Beres/Shutterstock.com |

Threatened Endangered |

Once a dominant tree in eastern deciduous forests, including in southern Ontario, the American chestnut was devastated by the invasive chestnut blight fungus in the early 1900s. American chestnuts still exist, but most are sprouts that do not reproduce. The American chestnut was assessed as endangered in 2004 because of ongoing threats and its small population size. |

|

Atlantic cod, Newfoundland and Labrador population

Photo: Travel Faery/Shutterstock.com |

Special concern Endangered |

The Atlantic cod once occurred in large numbers, but the population collapsed because of industrial overfishing. A moratorium on fishing was introduced in 1992. The Newfoundland and Labrador population had declined by 99% since the 1960s, and while numbers appear to be increasing, its abundance is at a fraction of historical numbers. |

|

Blanding’s turtle, Great Lakes population

Photo: Paul Reeves Photography/Shutterstock.com |

Threatened Endangered |

The Great Lakes population of the Blanding’s turtle, with its distinctive yellow throat and chin, is still widespread in parts of southern Ontario and Quebec but has been declining because of threats such as road mortality and habitat loss. |

|

Killer whale, northeast Pacific southern resident population

Photo: slowmotiongli/Shutterstock.com |

Threatened Endangered |

The southern resident population of the northeast Pacific killer whale (also known as the orca) ranges from the coasts of northern British Columbia to central California. During the summer months, they concentrate off the southern end of Vancouver Island. This population numbers fewer than 100 and is threatened by reduced prey availability, noise and disturbance by ships, and contaminants. This population, together with other orca populations, was assessed as threatened in 1999, and the southern resident population’s risk was reassessed as endangered in 2001. |

|

Monarch butterfly

Photo: Nancy Bauer/Shutterstock.com |

Special concern Endangered |

The monarch butterfly breeds across Canada in the summer and migrates up to 7,000 kilometres to Mexico and California for the winter. Monarch butterflies face many threats, including habitat loss, extreme weather events as a result of climate change, and pesticides. |

|

Spotted owl

Photo: Nick Bossenbroek/ |

Endangered |

There were once about 500 to 1,000 spotted owls in Canada. However, as their old-growth forest habitat in coastal British Columbia dwindled, their numbers in the wild have plummeted to 3. The recent arrival of the closely related barred owl in the province also threatens this species through competition and hybridization. Despite a captive breeding program, the spotted owl remains one of the most endangered species in Canada. |

|

Polar bear

Photo: Vaclav Sebek/Shutterstock.com |

Not at risk Special concern |

The polar bear is the world’s largest land carnivore. It inhabits Arctic sea ice and coastal areas, with about two thirds of the population found in Canada. The polar bear’s risk was increased to special concern in 1991 because of sea-ice loss from climate change. |

Source: Species at Risk Registry, Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2022

Species in Canada with signs of recovery

Some species have been brought back from the brink of extinction (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2—Examples of species that suffered historical declines but whose conservation status has improved

| Species | Risk category by year | Status history |

|---|---|---|

|

Swift fox

Photo: Ghost Bear/Shutterstock.com |

Extirpated Endangered Threatened |

The swift fox is one of Canada’s most successful wildlife reintroductions. It had disappeared from the Prairies by the 1930s because of habitat loss, trapping, and poisoning. In the early 1980s, swift foxes were returned to Saskatchewan and Alberta, through captive breeding programs. This population has now grown to over 600. |

|

Sea otter

Photo: rbrown10/Shutterstock.com |

Endangered Threatened Special concern |

The sea otter was extirpated in British Columbia by the fur trade by the early 1900s. The first reintroduction efforts occurred from 1969 to 1972. Since then, its range and numbers have continued to grow. |

|

Wood bison

Photo: Tim Malek/Shutterstock.com |

Endangered Threatened Special concern |

The wood bison is the northern cousin of the threatened plains bison and is the largest land animal in North America. It was on Canada’s first list of endangered wildlife in 1978 after suffering from more than a century of overhunting. Numbers have continued to grow, and new populations have been established through translocation projects. |

|

Humpback whale, western north Atlantic population

Photo: Paul S. Wolf/Shutterstock.com |

Threatened Special concern Not at risk |

Numbers of humpback whales along Canada’s Atlantic coast were dramatically reduced by commercial whaling in the 1800s. With the halt of whaling for this species in 1960, its numbers have rebounded. It was originally assessed together with the north Pacific population as threatened in 1982. |

|

Peregrine falcon (anatum and tundrius subspecies)

Photo: Harry Collins Photography/ Shutterstock.com |

Endangered Threatened Special concern Not at risk |

The peregrine falcon is 1 of just a few species in Canada to recover from being endangered to not at risk. The anatum subspecies was originally assessed as endangered in 1978. The species had declined throughout its range primarily because of the pesticide DDT, which was causing reproductive failure. It was then reassessed as threatened in 1999 and as being of special concern in 2007 (together with the tundrius subspecies). This recovery was the result of both a ban on DDT and on captive breeding and release programs. In 2017, after 39 years on Canada’s list of endangered wildlife, both the anatum and tundrius subspecies were assessed as being not at risk. A third subspecies remains in the special concern category, however. |

|

Trumpeter swan

Photo: Don Mammoser/Shutterstock.com |

Special concern Not at risk |

The trumpeter swan is the largest waterfowl species in the world. It was almost driven to extinction by 2 centuries of commercial hunting for its meat and feathers. When the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada first assessed it as being of special concern in 1978, the trumpeter swan had already started to recover because of hunting restrictions, habitat protection, and captive breeding and release programs. The trumpeter swan was then listed to being not at risk in 1996. Its numbers and range have continued to grow. |

Source: Species at Risk Registry, Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2022

International agreements and commitments

Canada has ratified or accepted 5 major international agreements that focus on biodiversity. The overarching agreement is the Convention on Biological Diversity and associated protocols. The objectives of this convention are the conservation of biological diversity, the sustainable use of its components, and the fair and equitable sharing of the benefits of commercial and other uses of genetic resources. The agreement covers all ecosystems, species, and genetic resources.

The Convention on Biological Diversity is complemented by 4 other international agreements:

- The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora aims to ensure that international trade in specimens of wild animals and plants does not threaten their survival. The convention gives varying degrees of protection to more than 30,000 plant and animal species.

- The International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture aims to conserve and promote sustainable use of plants’ genetic resources for food and agriculture, along with the fair and equitable sharing of the benefits of their use, in harmony with the Convention on Biological Diversity, for sustainable agriculture and food security.

- The Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Especially as Waterfowl Habitat (the Ramsar Convention) provides the framework for national action and international cooperation for the conservation and wise use of wetlands and their resources.

- The Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage identifies outstanding cultural and natural heritage sites and promotes closer cooperation among nations toward their preservation for all of humanity.

These major agreements are supplemented by others among fewer countries, such as the Convention for the Protection of Migratory Birds in the United States and Canada.

Canada’s domestic commitments to biodiversity

Protecting biodiversity in Canada is a joint effort that requires the collaboration of many parties. The federal, provincial, and territorial governments share responsibility for conserving biodiversity and for ensuring the sustainable use of biological resources. Also playing essential roles are Indigenous peoples, property owners, businesses, conservation organizations, municipalities, research institutions, foundations, and other groups. While the collaboration of many parties is important, the federal government also has an important leadership role to play.

The federal government is responsible for protecting the biodiversity of oceans, waters, and lands under its jurisdiction. This responsibility extends to aquatic species, migratory birds, and federally listed species at risk.

Although Canada does not have overarching biodiversity legislation at the federal level, there are several pieces of relevant federal legislation, including the following:

- Canada National Marine Conservation Areas Act

- Canada National Parks Act

- Canada Wildlife Act

- Fisheries Act

- Migratory Birds Convention Act, 1994

- Oceans Act

- Species at Risk Act

- Wild Animal and Plant Protection and Regulation of International and Interprovincial Trade Act

Provincial and territorial governments are the primary custodians of the natural resources within their boundaries, and some have developed their own biodiversity strategies. They are responsible for managing wildlife, overseeing resource development, and planning land use within their respective jurisdictions.

Indigenous peoples, as well as wildlife management boards, play an important role by managing biodiversity and contribute their traditional knowledge to the process of determining how to manage biodiversity and natural resources on their lands. Both the Convention on Biological Diversity and the Species at Risk Act recognize the importance of the preservation, maintenance, and consideration of traditional knowledge in the conservation of wildlife and biodiversity.

Biodiversity status and trends

The tables and charts below provide a snapshot of the status and trends of species at risk in Canada. While not complete, the snapshot presents the best monitored information available at this time. The federal government’s environmental sustainability indicators provide additional information on biodiversity.

The national status of wild species in Canada ranges from species with no conservation status rank assigned, to species that are extirpated or extinct (Exhibit 3). The 50,179 species described in this table are those that have been formally identified—only part of the estimated 80,000 species that exist in Canada.

Exhibit 3—National status of wild species in Canada

| Status | Number of species |

|---|---|

| Species that are known, but for which no conservation status rank has been assigned | 25,889 |

| Species that are known, but about which there is not enough information to assign a conservation status rank | 8,048 |

| Secure | 8,294 |

| Apparently secure | 4,804 |

| Vulnerable | 1,555 |

| Imperiled | 790 |

| Critically imperiled | 658 |

| Historical (believed to be extirpated or extinct) | 96 |

| Extirpated or extinct | 45 |

| Total (database query as of 4 June 2022) | 50,179 |

Source: NatureServe, 2022

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada has identified 841 species that are at risk (Exhibit 4), but this covers only a small fraction of Canada’s species thus far. Even so, a committee assessment does not necessarily result in a listing under the Species at Risk Act: The Minister of Environment and Climate Change is responsible for making recommendations to the Governor in Council on which species to protect under the act. So, the numbers of final decisions made, listed in the “Species at Risk Act (Schedule 1)” column, vary from those of the committee assessments.

The species assessed as being in the extirpated, endangered, threatened, and special concern categories are considered at risk.

Exhibit 4—Number of species at risk in Canada, assessed by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada and listed under the Species at Risk Act (by risk category)

| Risk category | Committee | Species at Risk Act (Schedule 1) |

|---|---|---|

| Extirpated | 21 | 23 |

| Endangered | 371 | 282 |

| Threatened | 196 | 141 |

| Special concern | 253 | 194 |

| Total | 841 | 640 |

Note: This table does not include the 23 extinct, 203 not at risk, and 62 “data-deficient” species that the committee has also assessed. The Governor in Council has not listed under the Species at Risk Act all of the species at risk identified by the committee.

Source: Species at Risk Registry, Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2022

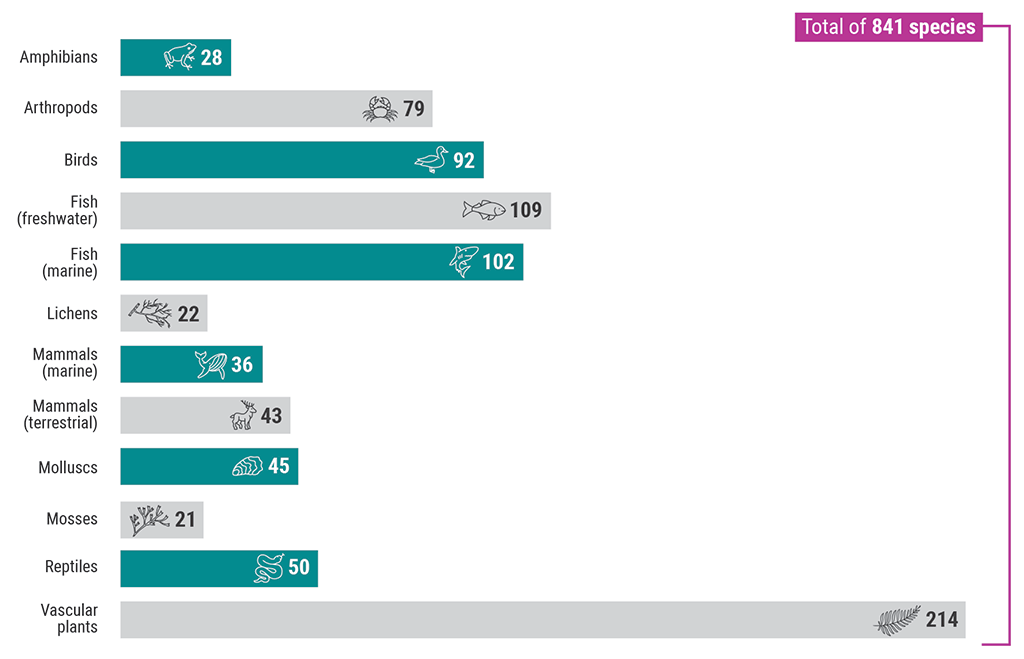

The numbers of committee recommendations to the Minister of Environment and Climate Change on species at risk vary, depending on the species’ biological classifications, also called taxa (Exhibit 5).

Exhibit 5—Number of species in Canada assessed as extirpated, endangered, threatened, and special concern, by taxon (biological classification), as of May 2022

Source: Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada

Exhibit 5—text version

This bar graph shows that as of May 2022, there were 841 species in Canada that were assessed by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada as extirpated, endangered, threatened, and special concern. By taxon, which is a biological classification, there were 28 amphibians, 79 arthropods, 92 birds, 109 freshwater fish, 102 marine fish, 22 lichens, 36 marine mammals, 43 terrestrial mammals, 45 molluscs, 21 mosses, 50 reptiles, and 214 vascular plants.

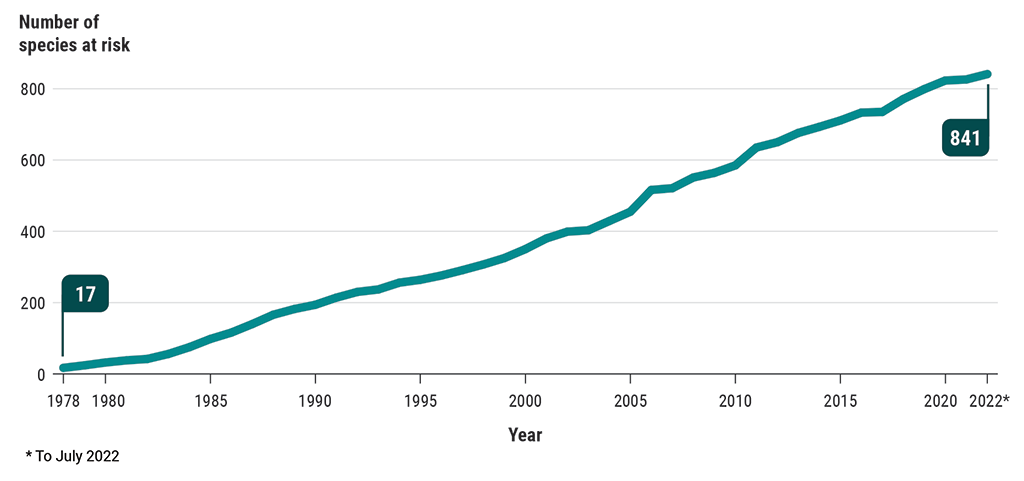

Since Canada developed its first list of endangered wildlife in 1978, the number of species identified by the committee as being at risk has increased steadily (Exhibit 6).The rising trend reflects a combination of the committee assessing more species over time and of species becoming more at risk.

Exhibit 6—Number of species at risk assessed as extirpated, endangered, threatened, and special concern by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, 1978 to 2022

Source: Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada

Exhibit 6—text version

This line graph shows the number of species at risk assessed as extirpated, endangered, threatened, and special concern by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada from 1978 to 2022. The graph shows a steady increase from 17 species at risk in 1978 to 841 species at risk in 2022 (up to July).

The number of species at risk are as follows.

| Year | Number of species at risk |

|---|---|

| 1978 | 17 |

| 1979 | 24 |

| 1980 | 32 |

| 1981 | 38 |

| 1982 | 42 |

| 1983 | 56 |

| 1984 | 75 |

| 1985 | 98 |

| 1986 | 116 |

| 1987 | 140 |

| 1988 | 166 |

| 1989 | 182 |

| 1990 | 194 |

| 1991 | 214 |

| 1992 | 230 |

| 1993 | 237 |

| 1994 | 256 |

| 1995 | 264 |

| 1996 | 276 |

| 1997 | 291 |

| 1998 | 307 |

| 1999 | 325 |

| 2000 | 350 |

| 2001 | 380 |

| 2002 | 399 |

| 2003 | 403 |

| 2004 | 429 |

| 2005 | 455 |

| 2006 | 516 |

| 2007 | 521 |

| 2008 | 551 |

| 2009 | 564 |

| 2010 | 585 |

| 2011 | 635 |

| 2012 | 650 |

| 2013 | 676 |

| 2014 | 693 |

| 2015 | 711 |

| 2016 | 733 |

| 2017 | 735 |

| 2018 | 771 |

| 2019 | 799 |

| 2020 | 823 |

| 2021 | 826 |

| 2022 (up to July) | 841 |