2024 Reports 5 to 7 of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of CanadaReport 7—Combatting Cybercrime

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings and Recommendations

- Poor case management limited the ability of the RCMP to respond to cybercrime incidents

- Communications Security Establishment Canada responded effectively to cybercrime incidents

- Thousands of cybercrime reports were not acted on by the CRTC and Communications Security Establishment Canada

- The RCMP had not built the capacity it needed to combat the growing issue of cybercrime

- Government of Canada–wide strategy was lacking in key areas of Canada’s fight against cybercrime

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- Recommendations and Responses

- Exhibits

Introduction

Background

7.1 Cybercrime is a rapidly evolving and continually expanding threat to Canadians, including to their financial assets, their private information, and even their personal safety. Cybercrime also threatens to disrupt the operations of businesses and institutions and can involve attacking critical infrastructure and services, such as power grids and hospitals.

7.2 According to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), cybercrime is any crime in which information technology (IT), including the Internet, plays a substantial role. Some cybercrimes target technology systems directly—for example, hacking into a database to steal or corrupt protected information. Other cybercrimes use IT as a means to commit crimes. Many cybercrimes rely on the use of spam, or mass‑distributed email that aims to persuade individuals to click links that may lead to malware.

7.3 Up until the 1990s, cybercrimes tended to involve individuals targeting large institutions or corporations. However, cybercrime is steadily becoming more sophisticated and more targeted to individuals. Cybercriminals can operate alone or may be part of a sophisticated organized crime group.

7.4 Year by year, cybercrime increases, both in the number of attacks and the overall amount stolen. In 2022, the Canadian Anti‑Fraud Centre, a national police service jointly operated by the RCMP, Competition Bureau Canada, and the Ontario Provincial Police, received reports of $531 million in total financial losses from victims of fraud. Three quarters of these reports were cybercrime related. This amount was more than triple the amount reported in 2020. The centre has projected that reported losses will increase to more than $1 billion by 2028. The centre also estimates that likely only 5% to 10% of cybercrimes are reported to it.

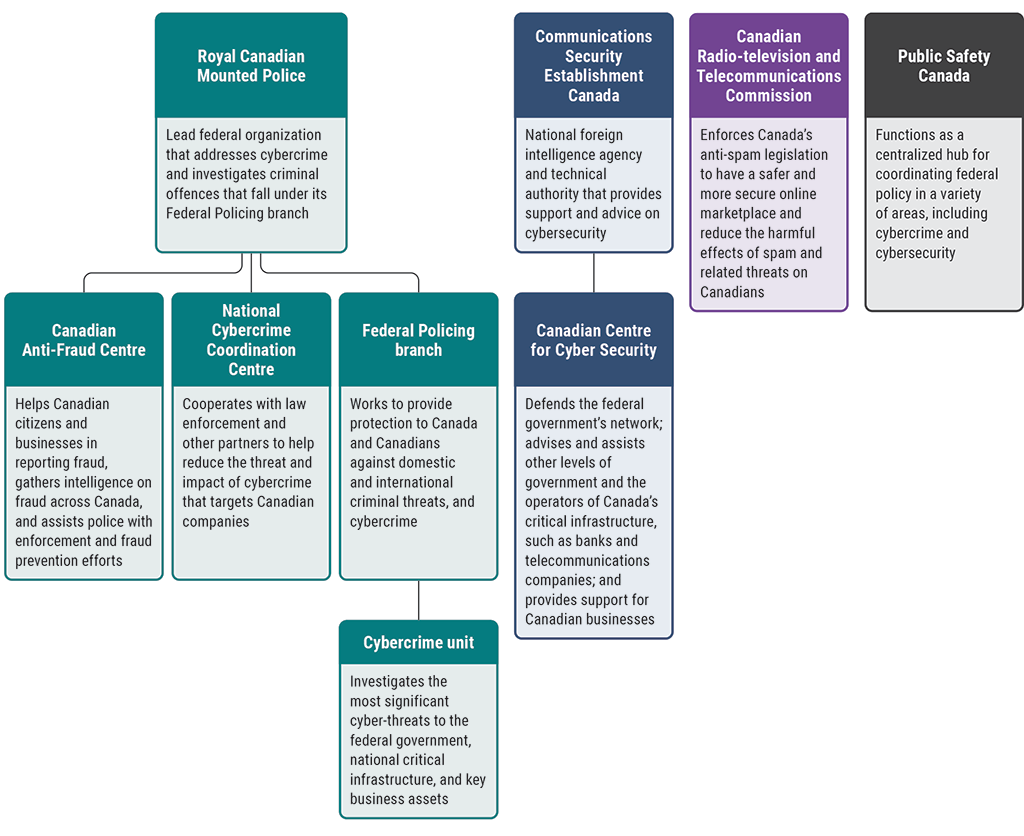

7.5 Several federal organizations have responsibilities related to cybercrime (Exhibit 7.1).

Exhibit 7.1—Federal organizations with cybercrime-related responsibilities

Source: Based on information from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Communications Security Establishment Canada, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission, and Public Safety Canada

Exhibit 7.1—text version

This flow chart shows the different federal organizations with cybercrime-related responsibilities and the ways that they are connected.

The largest branch is under the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, which is the lead federal organization that addresses cybercrime and investigates criminal offences that fall under its Federal Policing branch.

Under it are the following organizations:

- The Canadian Anti‑Fraud Centre, which helps Canadian citizens and businesses in reporting fraud, gathers intelligence on fraud across Canada, and assists police with enforcement and fraud prevention efforts.

- The National Cybercrime Coordination Centre, which cooperates with law enforcement and other partners to help reduce the threat and impact of cybercrime that targets Canadian companies.

- The Federal Policing branch, which works to provide protection to Canada and Canadians against domestic and international criminal threats, and cybercrime.

Under the Federal Policing branch is the Cybercrime unit, which investigates the most significant cyber‑threats to the federal government, national critical infrastructure, and key business assets.

The next branch is under Communications Security Establishment Canada, the national foreign intelligence agency and technical authority that provides support and advice on cybersecurity.

Under it is the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security, which defends the federal government’s network; advises and assists other levels of government and the operators of Canada’s critical infrastructure, such as banks and telecommunications companies; and provides support for Canadian businesses.

Finally, there are the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission and Public Safety Canada.

The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission enforces Canada’s anti‑spam legislation to have a safer and more secure online marketplace and reduce the harmful effects of spam and related threats on Canadians.

Public Safety Canada functions as a centralized hub for coordinating federal policy in a variety of areas, including cybercrime and cybersecurity.

7.6 RCMP. The RCMP is the lead federal organization for addressing cybercrime. It is responsible for investigating criminal offences that fall under its Federal Policing branch. The branch has a mandate to investigate the greatest criminal threats to Canada, including cybercrime, transnational and serious organized crime, and threats to national security. One of the RCMP’s core responsibilities is also to provide programs that support other Canadian police agencies. This includes specialized cybercrime expertise and investigative support. The RCMP also coordinates multijurisdictional cybercrime investigations.

7.7 Communications Security Establishment Canada. The establishment is Canada’s national agency for intelligence on foreign signals—that is, the interception, decoding, and analysis of electronic communications. It also serves as the government’s technical authority on cybersecurity, providing technical and operational assistance to federal law enforcement and security agencies, including the RCMP. It hosts the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security. The centre is responsible for providing cybersecurity advice, guidance, services, and support for Canadian businesses; critical infrastructure, such as transportation and communications; and federal government systems.

7.8 Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC). The CRTC regulates and supervises broadcasting and telecommunications. The CRTC also enforces Canada’s anti‑spam legislation. While violations of this legislation are not in themselves criminal, they can enable criminal activity.

7.9 Public Safety Canada. This department functions as a centralized hub for coordinating the work of federal departments and agencies in a variety of areas, including cybersecurity. The department is also responsible for developing policies and providing advice to the Minister of Public Safety.

7.10 Other organizations. Criminal investigations related to cybercrime may require involvement by several of the above-listed federal organizations, along with other law enforcement agencies at the provincial, territorial, and municipal levels; First Nations police services; and international partners, such as the European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation (Europol).

7.11 In recent years, Canada has undertaken several initiatives to address cybercrime:

- Public Safety Canada’s National Cyber Security Strategy. Launched in 2018 under the leadership of Public Safety Canada, this strategy includes goals to address cybercrime and initiatives such as funding for the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security, creating the RCMP’s National Cybercrime Coordination Centre, and funding to develop Canadian expertise in cybersecurity. A new strategy was being developed at the time of our audit.

- The RCMP’s National Cybercrime Coordination Centre. In 2018, the Government of Canada established the centre to act as a service provider to Canadian law enforcement. The centre coordinates investigations, provides technical advice and guidance, produces actionable cybercrime intelligence, and established a national cybercrime reporting mechanism. The primary focus of the centre is on cybercrime that targets technology itself, such as ransomware, malware-based cybercrime, data breaches, and other intrusions targeting Canadian companies and businesses.

- The RCMP’s Canadian Anti‑Fraud Centre. The centre focuses on cybercrimes that target individuals—for example, fraud, identity crimes, romance scams, business email compromise, advance fee fraud, phishing (attacks that attempt to lure individuals to reveal personal information on legitimate-seeming websites), and spear phishing (phishing campaigns that target a specific person or group). The RCMP takes the lead on managing the centre, which is a joint operation among the RCMP, Competition Bureau Canada, and the Ontario Provincial Police.

- The RCMP’s Federal Policing branch. The branch works to provide protection to Canada and Canadians against domestic and international criminal threats, and cybercrime.

- The Federal Policing branch’s cybercrime unit. As of reporting, the unit had a total of 5 cybercrime investigative teams across the country. The teams are mandated to investigate the most significant cyber-threats to the federal government, national critical infrastructure, and key business assets.

Focus of the audit

7.12 This audit focused on whether the RCMP and selected federal entities had the capacity and capability to effectively enforce laws against cybercrime and to ensure the safety and security of Canadians.

7.13 This audit is important because Canadian individuals, businesses, institutions, and infrastructure will continue to be targets for cybercriminals. Because of the increasing sophistication of cybercrime attempts, the low rate of reporting, and the fact that cybercrime does not respect domestic and international borders, collaboration and a strategic response are needed more than ever.

7.14 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings and Recommendations

Poor case management limited the ability of the RCMP to respond to cybercrime incidents

7.15 This finding matters because federal organizations respond to cybercrime cases through investigations by notifying potential victims, such as businesses and organizations, and by providing advice and assistance to victims to mitigate the impact of cybercrimes. An effective response enables actions, such as avoiding ransomware, that prevent or reduce the effects of the cybercrime.

7.16 Victim notifications often involve international law enforcement partners informing the RCMP about Canadian businesses and organizations undergoing imminent, real‑time, or recent cybercrime attacks. The notifications can also involve cases where, in the course of its intelligence work, the RCMP becomes aware that an organization was the victim of a cybercrime attack—for example, by finding that an organization’s data was leaked and uploaded to the dark web. The RCMP’s National Cybercrime Coordination Centre sends an electronic victim notification to the appropriate municipal, provincial, First Nations, or territorial police agency to inform it of the situation so that local police can contact the victim organization.

Lack of RCMP procedures and service standards to manage victim notifications

7.17 We found that the RCMP had no formal standard for how quickly its National Cybercrime Coordination Centre should issue victim notifications. RCMP officials confirmed to us that they considered victim notifications to be a high priority and generally expected them to be managed within 1 day. We applied that 1‑day expectation to 37 cases that we reviewed. We found that the majority of victim notifications were issued within that informal target of 1 day (Exhibit 7.2). Among the 9 cases that took between 2 and 27 days, officials said they considered these cases to be less urgent because the cases dealt with potential crimes that happened in the past and that did not require immediate attention.

Exhibit 7.2—The RCMP’s National Cybercrime Coordination Centre issued the majority of victim notifications within 1 day in 37 cases that we reviewed

| Time period | Number of victim notifications | Percentage of victim notifications |

|---|---|---|

| Issued within 1 day | 26 of 37 | 70% |

| Issued between 2 and 27 days | 9 of 37 | 24% |

| OtherNote * | 2 of 37 | 6% |

7.18 We also found that the RCMP’s centre had no standard procedures to triage victim notification requests on the basis of their levels of urgency—for example, by prioritizing cybercrime attacks targeting important economic targets, such as a major bank or major telecommunications company. The result was that when the number of victim notifications that needed to be issued was high and a backlog of requests developed, the centre lacked procedures to ensure that the most urgent cases were identified and addressed first.

7.19 The notification does not actually reach the victim unless the police agency contacted by the RCMP’s centre notifies the victim. The centre routinely asks the police agencies to confirm that they have done this. We found that the centre received such confirmations from agencies in 24 of 34 (71%) of the cases we reviewed. However, for the remaining 10 cases, the law enforcement agencies did not reply. This lack of response made it impossible for the centre to determine whether the victims were contacted on time by their local police and whether the victim notifications helped prevent cybercrimes.

7.20 The RCMP’s National Cybercrime Coordination Centre should establish procedures to identify the most urgent victim notifications and ensure that they are sent first. The centre should set formal expectations for how fast victim notifications are sent, measure against these standards, and ensure that they are met.

The RCMP’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Incomplete RCMP responses to requests to coordinate cases with police partners

7.21 The RCMP’s National Cybercrime Coordination Centre responds to requests for help with investigations of cybercrime incidents from partner law enforcement agencies. Each of these requests includes 2 elements:

- conducting research to determine whether a specific incident was connected to other cybercrime cases

- sharing evidence and coordinating with the partner law enforcement agency conducting ongoing investigations

7.22 We found that the centre’s responses to these requests were not always properly documented. For 39% (17 of 44) of the requests, the file was missing required documents, such as the initial request for assistance from the partner organization. Despite this, in some cases, the supervisor still approved and closed the file. Also, in some cases, the required supervisor reviews were not completed.

7.23 We found that the centre did not forward 7 of 26 (27%) of the requests we reviewed from international partners to domestic police agencies to see whether they had evidence relevant to the investigation. It was unclear to us why the centre had not forwarded the requests. No explanation for these decisions was included in the files. This made it impossible to confirm whether the information was not shared in error or for a legitimate reason, such as the international partner asking that the request not be shared outside the RCMP.

7.24 The RCMP’s National Cybercrime Coordination Centre should ensure that all requests for assistance received from domestic and international partners are fully documented and completed so that all necessary information is provided as part of the response. The centre should share requests as appropriate with all organizations implicated by the request.

The RCMP’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Poor RCMP tracking and assessment of cybercrime incidents

7.25 We found that the stated approach of the RCMP’s Federal Policing branch was to manage cybercrime through centralized governance to ensure that resources were focused on the most important cases. The branch has a cybercrime unit with 5 investigative teams spread around the country. The teams focus on investigating cases that represent a serious threat to Canada. The unit has 4 priority areas, which include crimes that

- threaten the federal government

- target critical infrastructure, such as hospitals or public utilities

- threaten important business assets

- target Canadian institutions on behalf of a foreign state

However, we found that prioritization did not happen. Instead, investigations could be initiated without the cybercrime unit prioritizing and assigning potential cases to its teams for investigation.

7.26 A key control for achieving prioritization of the most important cases is a form called the Occurrence Triage Aid. The form includes assessment criteria, such as applicability to the mandate of the RCMP’s Federal Policing branch, resource availability, and alternatives to a Federal Policing response. However, our review of a sample of 36 cases assigned to the Federal Policing cybercrime unit found that only 3 of the 36 cases (8%) had a completed Occurrence Triage Aid. We also found that 5 of the 36 cases (14%) we reviewed did not fit within any of the 4 priority areas set for the unit, listed in paragraph 7.25. As a result, specialized resources were not focused on the most important cases.

7.27 Moreover, we found that the RCMP had poor records management and a lack of quality data. This impaired the Federal Policing branch’s ability to understand the full picture of cybercrime cases reported to its cybercrime unit and to keep track of specific cases assigned to the unit for investigation. As a result, the Federal Policing branch was unable to produce an accurate count of all the potential cybercrimes reported to it and could not accurately track the cases assigned to the cybercrime unit. For example, we found that the RCMP’s records management system relied on manually input data fields to identify possible cybercrimes that could be left blank or filled in incorrectly, making it impossible to reliably identify possible cybercrimes.

7.28 In 2018, the RCMP was allocated $78.9 million over 5 years to increase the cybercrime unit’s capacity, of which $55.2 million had been spent as of 31 March 2023. As a result of the issues that we observed with the Federal Policing branch’s cybercrime data, the results reported publicly for the Federal Policing branch for performance indicators, such as the number of cybercrime investigations closed, were not accurate or complete. Because of this inaccurate or incomplete data, the RCMP could not demonstrate whether Canadians were receiving value for the money spent on the cybercrime unit.

7.29 We also found that the RCMP’s Federal Policing branch had defined internal performance measures that were intended to be used to help with program management. Because of inaccurate and incomplete data, the branch was unable to generate these measures during the audit period. This meant that the Federal Policing branch lacked an important source of information to manage the cybercrime unit.

7.30 The RCMP’s Federal Policing branch should ensure that a consistent triage process is managed centrally and is followed so that specialized cybercrime investigative resources are focused on the most serious cybercrime investigations.

The RCMP’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

7.31 The RCMP should ensure that its information management systems capture accurate and complete data to assess performance, improve decision making, and demonstrate value for money for the work done by its Federal Policing branch’s cybercrime unit.

The RCMP’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Communications Security Establishment Canada responded effectively to cybercrime incidents

7.32 This finding matters because by helping Canadian organizations that have been victims of cybercrime attacks, Communications Security Establishment Canada prevents or reduces the harm caused by those attacks. By cooperating effectively with the RCMP, the establishment helps to ensure a more coordinated and effective federal response to cybercrimes.

Communications Security Establishment Canada met standards for timely incident response and notifying victims

7.33 Communications Security Establishment Canada hosts the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security. The centre is responsible for providing cybersecurity advice, guidance, services, and support for Canadian businesses; critical infrastructure, such as transportation and communications; and federal government systems. We found that the centre met its standards for responding to cybercrime-related incidents in 80% of cases, including the following up with potential victims and the timeliness of the response and the notification of potential victims. Organizations that are the victims of cybercrime incidents can contact the establishment for assistance. The establishment is not a law enforcement agency and does not take enforcement action. Instead, it provides advice and guidance to the organizations on how to respond to the attack. It also works with other organizations that should be involved in the response, such as the RCMP or other law enforcement agencies.

7.34 We reviewed a sample of 51 cybercrime-related incidents during the 2021–22 and 2022–23 fiscal years. We selected them out of a total 5,341 incidents that the establishment responded to after organizations reported them to the establishment. We found the following:

- The establishment’s response was timely 80% of the time. Its agents analyzed the priority of the incidents according to its triage criteria in its standard operating procedures and assigned them to agents who responded to them within the required timelines. Those requirements were a response within 1 hour of reporting for the most serious incidents and a response within 2 business days for the least serious.

- Agents followed up with the reporting organization 80% of the time to ensure that their cases had been appropriately handled as required by policy.

- For cases in which the reported incident affected 1 or more third parties, the establishment informed the third-party victims 95% of the time. This complied with the establishment’s standard of informing affected parties or victims so they could take measures to protect themselves.

Effective Communications Security Establishment Canada cooperation with the RCMP

7.35 We found that Communications Security Establishment Canada and the RCMP coordinated with each other in their response to cybercrime cases. They shared information on those cases and coordinated the response to high‑priority potential cybercrime incidents—essentially, those that could affect Government of Canada systems or other systems of importance to Canada.

7.36 We reviewed 41 cases where the RCMP asked the establishment to cooperate in issuing a victim notification. In 33 of 41 (80%) of these cases, the RCMP’s National Cybercrime Coordination Centre received a response from the establishment the same or the next day.

Thousands of cybercrime reports were not acted on by the CRTC and Communications Security Establishment Canada

7.37 This finding matters because addressing cybercrime effectively depends on reports going to the organizations best equipped to receive them and on those organizations acting on the reports, thus helping protect Canadians against the risk of financial loss and other harms.

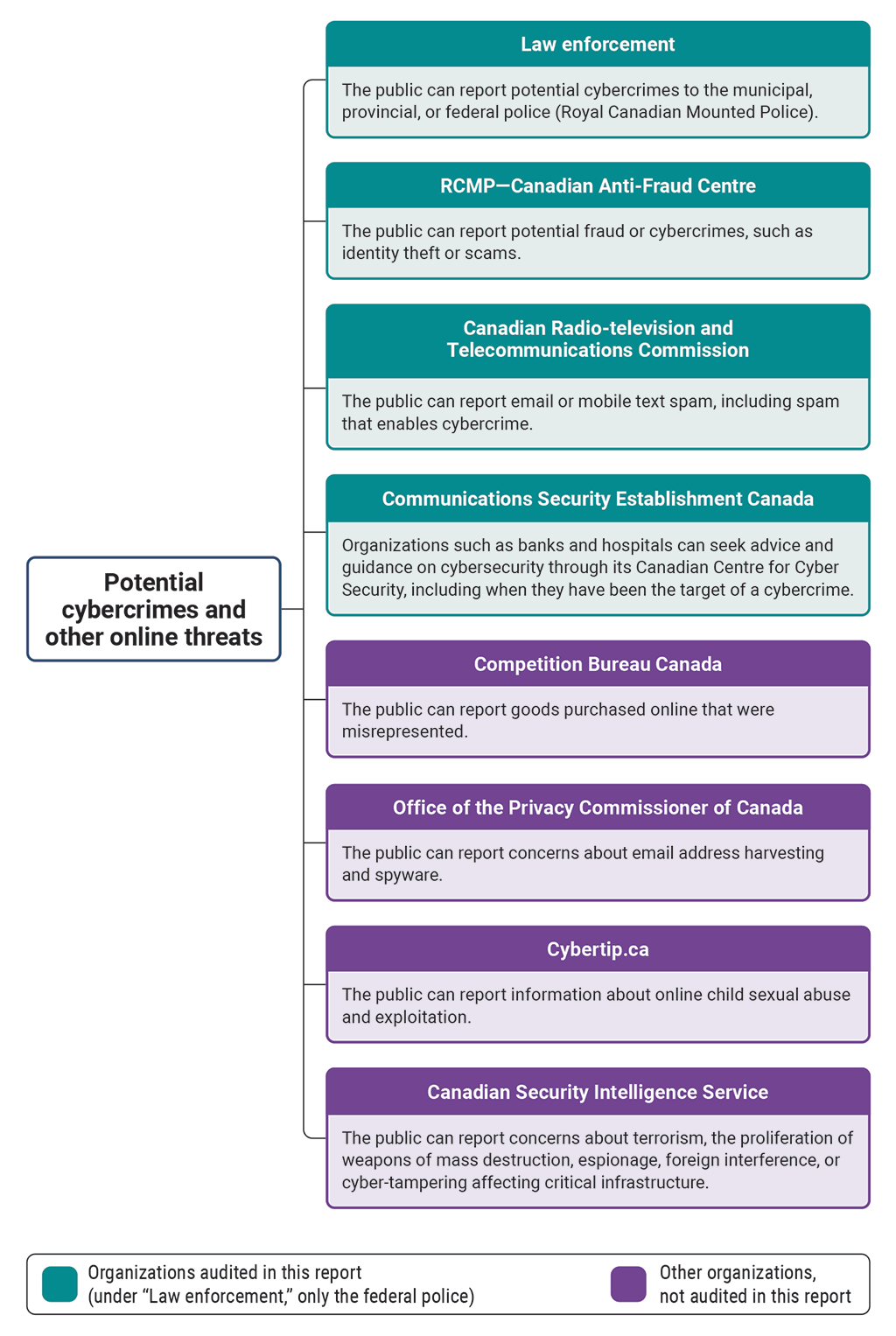

7.38 In Canada, the public can report potential cybercrimes and other online threats to a variety of organizations with different mandates (Exhibit 7.3).

Exhibit 7.3—Public reporting of potential cybercrimes and other online threats in Canada

Source: Based on information from the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security and the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

Exhibit 7.3—text version

This list shows the ways that the public can report cybercrime and other online threats and is categorized by organizations included in the audit and those not included in the audit.

The following are organizations included in the audit:

- Law enforcement—The public can report potential cybercrimes to the municipal, provincial, or federal police (that is, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police). The only law enforcement agency included in the audit is the federal police.

- The Royal Canadian Mounted Police’s Canadian Anti‑Fraud Centre—The public can report potential fraud or cybercrimes, such as identity theft or scams.

- The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission—The public can report email or mobile text spam, including spam that enables cybercrime.

- Communications Security Establishment Canada—Organizations such as banks and hospitals can seek advice and guidance on cybersecurity through its Canadian Centre for Cyber Security, including when they have been the target of a cybercrime.

The following are other organizations not included in the audit:

- Competition Bureau Canada—The public can report goods purchased online that were misrepresented.

- The Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada—The public can report concerns about email address harvesting and spyware.

- Cybertip.ca—The public can report information about online child sexual abuse and exploitation.

- The Canadian Security Intelligence Service—The public can report concerns about terrorism, the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, espionage, foreign interference, or cyber-tampering affecting critical infrastructure.

7.39 Communications Security Establishment Canada has a mandate to provide advice and technical assistance to Canadian organizations facing a potential cybercrime. Its clientele includes owners of critical infrastructure (such as power grids and telecommunications networks), Government of Canada organizations, and private enterprises. The mandate does not extend to assisting individual citizens who have been victims of cybercrime. The establishment is also responsible for collaborating with enforcement organizations, including the RCMP and the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC).

7.40 In 2014, Canada’s anti‑spam legislation came into force. The objective of this legislation is to protect Canadians against spam, such as phishing, malware, identity theft, and online scams. The online Spam Reporting Centre was put in place for members of the public to make complaints related to violations of the anti‑spam legislation. At times, the CRTC receives other types of complaints that may warrant investigation by another agency because threats can be both a violation of Canada’s anti‑spam legislation and a violation of the Criminal Code.

7.41 The anti‑spam legislation is a civil regulatory regime. The CRTC has civil enforcement powers, which are distinct from those of a law enforcement agency. Its investigative powers include requesting that information relevant to a CRTC investigation be provided or preserved and executing search warrants to verify compliance. The CRTC can also take actions, including issuing notices to people believed to have committed a violation of the anti‑spam legislation and negotiating agreements to address the non‑compliance, both of which may include a specified amount to be paid.

The CRTC does little to protect Canadians against online threats

7.42 We found that during the 2022–23 fiscal year, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) received 335,751 reports to its Spam Reporting Centre concerning potential anti‑spam legislation violations. We estimated that about 75,000, or 22% of these reports, were cybercrime-linked incidentsDefinition 1. Not all of these reported incidents would have led to an investigation. Some reports would be similar and linked together; others would not include enough information to be followed up. However, there remains a large gap between the number of reports received by the Spam Reporting Centre and the number of investigations conducted by the CRTC.

7.43 We found that most of the cybercrime-linked reports were not investigated by the CRTC. We found that during the 3 years in our audit period, the CRTC conducted only 6 investigations into anti‑spam violations with links to cybercrime-linked incidents. Of these investigations,

- 3 resulted in enforcement action against individuals, such as assessing a monetary penalty

- 2 were ongoing at the time of our audit

- 1 was closed, as the CRTC determined that no further action was needed

7.44 We found that the CRTC’s operating procedures allowed for the sharing of information with law enforcement in a limited set of circumstances, such as when conducting its own search warrants to ensure the safety of its staff, or in response to judicial orders, such as a production order or a warrant. However, the CRTC told us that there are limitations on their ability to share information with law enforcement agencies because the anti‑spam legislation is a civil administrative regime and disclosing information to criminal law enforcement agencies could lead to breaches of Canadians’ privacy rights.

7.45 The CRTC’s operating procedures state that information should always be shared with law enforcement when a victim reports information involving an imminent danger to life or safety, threats to the welfare of a child, or any activity involving child sexual exploitation material or the sale of such material. These procedures also outline additional steps to be taken when the risk to an individual is particularly high. In December 2021, the CRTC received a report through the Spam Reporting Centre from an individual about an offer to purchase child sexual exploitation material. Rather than forwarding the report to law enforcement, the CRTC contacted the individual and asked them to report the incident to law enforcement. It is unknown whether the individual did so. We raised our concerns with the CRTC that it did not forward this report to a law enforcement agency, as required by its operating procedures. The CRTC disagreed and took the position that its operating procedures do not require it to inform law enforcement because the person who made the report to the online Spam Reporting Centre was not the potential victim or at immediate risk of harm. As a result, we informed the RCMP of the incident in April 2024.

7.46 We found that for 1 of the 6 investigations under the anti‑spam legislation, the CRTC provided incorrect information to a law enforcement agency in response to the possibility of being served with a search warrant. In 2019, the CRTC began an investigation into several individuals for cybercrime-linked violations of the anti‑spam legislation. As part of this anti‑spam investigation, the CRTC seized several electronic devices from the individuals to be used as evidence. The CRTC became aware that 1 of the individuals was also being investigated by a law enforcement agency for possible related criminal charges. The CRTC informed the law enforcement agency about its own investigation. The law enforcement agency issued a production order to the CRTC for the electronic evidence stored on the devices, which it complied with.

7.47 In addition to the production order, the CRTC was informed that it was going to receive a warrant to obtain the physical devices. A decision was made by the CRTC to delete data on the devices on an accelerated time frame after obtaining the consent of the owner of the devices. The CRTC subsequently contacted the law enforcement agency to inform it that the data on the devices had been deleted and that a warrant was no longer viable. However, we found that the statement made to the law enforcement agency was incorrect, as the data on the devices was deleted at a later date. In October 2023, we informed CRTC management and senior officials about our serious concerns with how this matter was handled.

7.48 In addition, we found further concerning practices at the CRTC in terms of decision making about enforcement action. Under Canada’s anti‑spam legislation, a “designated person” has the authority to undertake enforcement actions, such as issuing notices to produce or preserve information and notices of violation of the legislation. Members of the CRTC’s Electronic Commerce Enforcement division are considered “designated persons.” However, we observed that legal services often made decisions about whether to take an enforcement action, even though legal services are not “designated persons.”

7.49 The above findings illustrate elements of the CRTC’s culture that we observed during the audit. We found that the CRTC was risk averse. We observed a strained relationship between CRTC legal services and officials of the Electronic Commerce Enforcement division. At times, this resulted in delays and missed opportunities to address the most serious possible cyber-threats under the CRTC’s administration of the anti‑spam legislation. We observed that there was a marked lack of trust and civility between these 2 teams. In our view, the CRTC’s culture affected the ability of the Electronic Commerce Enforcement division staff to act in the public interest when performing their duties.

7.50 The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission should ensure that it has clear policies and procedures outlining when and under what circumstances information it acquires will be shared with law enforcement.

The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

7.51 The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission should ensure that roles and responsibilities of officials responsible for enforcement comply with the requirements of the legislation. Further, it should ensure that only “designated persons” under Canada’s anti‑spam legislation make key decisions as part of their role to enforce the legislation.

The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

No acknowledgement from Communications Security Establishment Canada when individuals reported incidents online

7.52 We found that Communications Security Establishment Canada’s Canadian Centre for Cyber Security public contact centre received 10,850 telephone calls, emails, and online reports in the 2021–22 and 2022–23 fiscal years. The establishment deemed 5,766 of these reports to be within its mandate because they related to businesses and organizations, not individuals. These reports went through the establishment’s incident response protocol. As part of this work, we confirmed that cases that were identified as falling within the establishment’s mandate were correctly classified and that the establishment did not respond to cases that fell outside of its mandate. The remaining 5,084 reports were deemed to be outside of its mandate because they related to individual Canadians and not organizations. The establishment determined that 27% of these incidents (1,366 of 5,084) were reports of potential cybercrimes.

7.53 We found that the establishment directed individual Canadians to report to relevant organizations, such as the RCMP’s Canadian Anti‑Fraud Centre, only when they reported incidents by phone or email. Reports by phone or email constituted 3,212 (63%) of the 5,084 out‑of‑mandate incidents.

7.54 We found that the establishment did not respond to individual Canadians when they reported incidents on the centre’s online (web) reporting portal. Web reports constituted 1,870 (37%) of the 5,084 out‑of‑mandate incidents. Because of privacy policies, the centre also did not forward these reports for further action to the appropriate authorities, such as the RCMP’s National Cybercrime Coordination Centre. The establishment’s Canadian Centre for Cyber Security deleted information from all out‑of‑mandate reports almost immediately. However, we found that the establishment did not have controls to ensure that reports were accurately assessed as being out of mandate before deletion. This created a risk that some reports deemed to be out of mandate may have been inaccurately assessed, and the establishment should have addressed them.

7.55 Our recommendation for this section is at paragraph 7.78.

Limitations in follow‑up data on high‑priority cybercrime reports

7.56 We found that the RCMP’s Canadian Anti‑Fraud Centre logged more than 87,000 reports of potential fraud from the Canadian public during the 2022–23 fiscal year. The centre assessed that more than 28,000 of these reports involved potential cybercrimes. Of the 28,000 reports, 3,257 involved Canadian victims losing $10,000 or more from a cybercrime. This is a threshold for considering a case to be a high priority and requiring action.

7.57 We found that in its internal information management system, the centre rarely linked complaints received into its database to the corresponding follow‑up action. This is because complaints were received and stored on 1 system, while follow‑up actions were tracked in another system. Reports in the 2 systems must be linked manually, and we found that staff failed to do this. As a result, we were able to match only 6% (196 of 3,257) of the high‑priority complaints received to the corresponding follow‑up actions. Because of this, the Canadian Anti‑Fraud Centre was missing an opportunity to better understand effective approaches for the resolution of complaints and to better report on its progress. The inability to track reported cases also created a risk that some high‑priority cases were not addressed.

7.58 The RCMP should improve its information management systems and practices so that it can consistently match reports received by the Canadian Anti‑Fraud Centre to actions taken. This will allow the RCMP to track progress on high‑priority cases and identify effective approaches used.

The RCMP’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

The RCMP had not built the capacity it needed to combat the growing issue of cybercrime

7.59 This finding matters because the effectiveness of efforts by the RCMP to combat cybercrime depends on having enough people with the skills needed to conduct cybercrime investigations along with comprehensive and adaptive IT systems and information.

7.60 In 2018, the RCMP submitted a business case that highlighted the need for IT systems that could store the large amounts of data needed to track and effectively analyze cybercrime data. The business case highlighted that the systems are necessary for the National Cybercrime Coordination Centre to reach full operational capability. In June 2020, the RCMP received $69.5 million to develop an IT system to help with efforts to address cybercrime, the National Cybercrime Solution. The solution was scheduled for full implementation by 31 March 2023 but was delayed, with an anticipated delivery date of March 2025.

7.61 The National Cybercrime Solution is intended to consist of 3 components:

- an updated public portal for victims to report cybercrimes

- a database of cybercrime indicators, case information, and other data, which Canadian law enforcement agencies can query to identify common cases and help coordinate investigations

- a system that allows cross‑referencing of domestic and international malware samples to help identify things such as malicious IP addresses associated with known criminal activity

Insufficient human resources

7.62 We found that the RCMP’s cybercrime investigative teams experienced ongoing challenges in recruiting and retaining staff with the needed technical skills, which affected the RCMP’s capacity to address cybercrime. The RCMP’s Federal Policing branch did not have reliable tracking of the number of vacant positions in the branch’s cybercrime unit. As of January 2024, we estimated that 30% of positions were vacant.

7.63 However, we noted gaps in the RCMP’s analysis of its staffing challenges. In particular, while the RCMP’s analysis included collecting data on why employees left the organization and on employee wellness and diversity, none of the analysis was specific to cybercrime positions. Also, the RCMP had not done an internal labour market analysis of its existing workforce, its workforce needs, and how employees advance within it. Such an analysis could help the RCMP in recruiting and retaining cybercrime staff. RCMP officials told us that compensation was the main reason for these staffing challenges. The officials also told us that individuals doing the same cybercrime technical work in the private sector were typically paid more.

7.64 The RCMP should conduct an analysis to understand its challenges in recruiting and retaining staff for specialized cybercrime positions. It should use the results to guide future recruiting and retention efforts to increase its capacity to address cybercrime.

The RCMP’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Delayed implementation of the RCMP’s National Cybercrime Solution

7.65 The RCMP began deploying components of the National Cybercrime Solution for user testing and limited operational use in April 2023. However, officials told us that the full implementation of the solution had been delayed until March 2025, which is 2 years later than originally planned.

7.66 We found that there were a number of reasons for the delay, including that the RCMP underestimated the complexity involved in migrating existing data to the new system. In addition, there were problems with aligning system features with user needs.

7.67 During our audit period, the RCMP’s National Cybercrime Coordination Centre was relying on a variety of IT systems that had to be supplemented by manual processes. We found that these systems were limited in their ability to receive and link reported instances of cybercrimes across Canadian police jurisdictions’ databases and from international sources.

7.68 We found that as of 31 December 2023, the RCMP had spent $29.7 million of the $69.5 million it received in 2020 for the project. RCMP officials told us that they expected to deliver the project on budget even with the delay. However, we found that not all of the staff costs associated with the project were included in the financial reporting. In our view, ongoing delays to the project schedule represent an escalating risk that money invested in the project will not yield all of the intended benefits and could lead to project cost overruns.

7.69 The RCMP should ensure that the problems experienced with the National Cybercrime Solution’s system features aligning with user needs are overcome so that the project meets all of its requirements. It should also implement effective risk responses and contingency plans so that the project is delivered on budget and within the revised timeline.

The RCMP’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

The RCMP established partnerships with Canadian and international law enforcement

7.70 We found that the RCMP’s National Cybercrime Coordination Centre established partnerships with Canadian and international law enforcement agencies. The partnerships helped the centre to understand the needs of these agencies for programs from the RCMP that support the agencies’ efforts against cybercrime and to share high‑level information on cybercrime trends. For example, domestically, some of the centre’s officials were members of the National Police Services Cybercrime Committee. Through this committee, various Canadian police agencies and other key partners exchange information about cybercrime trends.

Government of Canada–wide strategy was lacking in key areas of Canada’s fight against cybercrime

7.71 This finding matters because addressing cybercrime requires a coordinated approach, including federal entities, provincial and municipal governments, and the private sector.

7.72 Public Safety Canada is the policy lead for developing and implementing the National Cyber Security Strategy. The strategy was launched in 2018. It was undergoing renewal at the time of our audit, and the renewed strategy was scheduled to be released in 2024.

7.73 Public Safety Canada chairs (or co‑chairs with Communications Security Establishment Canada) a variety of working groups on cybersecurity. They include deputy minister, assistant deputy minister, and director general governance committees and a variety of interdepartmental working groups focused on specific cybersecurity issues. Membership in these governance committees includes a variety of federal organizations, such as the RCMP, but not the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC).

Weaknesses in the National Cyber Security Strategy

7.74 We found that the CRTC was not included in the original National Cyber Security Strategy or the strategy being renewed at the time of our audit. The CRTC was excluded even though its mandate to enforce Canada’s anti‑spam legislation can have an important impact on cases with a link to cybercrime.

7.75 The RCMP, Communications Security Establishment Canada, and Public Safety Canada have all discussed the option of implementing a single point where Canadians could report cybercrime. Reports made by the public could then be routed to the organization mandated to act on them. However, we found that the single point of reporting had not been implemented. In our view, a coordinated response to cybercrime with 1 single point for Canadians to report cybercrime would simplify the process and eliminate the need for Canadians to report the same incident to multiple organizations.

7.76 As part of work to develop the new National Cyber Security Strategy, various options to develop Canada’s cybersecurity workforce were under consideration. In our view, having a plan to reduce human resource gaps across all responsible organizations is an important component of an updated strategy.

7.77 Because violations of Canada’s anti‑spam legislation can be linked to cybercrime, Public Safety Canada should include the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission in the development of Government of Canada initiatives to address cybercrime.

Public Safety Canada’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

7.78 Public Safety Canada, the RCMP, Communications Security Establishment Canada, and the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission should work together to ensure that cybercrimes reported by Canadians and Canadian businesses are routed to the organization with the mandate to address them.

Response of each entity. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Conclusion

7.79 We concluded that the RCMP and selected federal entities did not have the capacity and capability to effectively enforce laws against cybercrime activities to ensure the safety and security of Canadians.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on combatting cybercrime. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs and to conclude on whether the RCMP and selected federal entities complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements, set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada applies the Canadian Standard on Quality Management 1—Quality Management for Firms That Perform Audits or Reviews of Financial Statements, or Other Assurance or Related Services Engagements. This standard requires our office to design, implement, and operate a system of quality management, including policies or procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate, except for the Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC). The CRTC did not confirm that the findings in this report are factually accurate.

Audit objective

The objective of the audit was to determine whether the RCMP and selected federal entities had the capacity and capability to effectively enforce laws against cybercrime activities to ensure the safety and security of Canadians.

Scope and approach

The audit focused on efforts by the RCMP (through the National Cybercrime Coordination Centre and the Federal Policing cybercrime unit’s investigative teams) and efforts deployed by Communications Security Establishment Canada’s Canadian Centre for Cyber Security and the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) to address cybercrime and related offences impacting individuals, businesses, and other institutions.

Specifically, we examined whether the RCMP had been able to develop the capacities and capabilities needed to confront the rapidly expanding and evolving threat of cybercrime and whether the RCMP provided the support and collaboration needed to help law enforcement throughout Canada to meet this threat. We also examined the roles played by Public Safety Canada, Communications Security Establishment Canada, and the CRTC in addressing cybercrime within their respective mandates.

We reviewed data from entity systems to understand

- the volume of potential cybercrime cases reported by Canadians and Canadian businesses to the entities in scope, in order to assess whether all cases reported were reviewed and forwarded to the appropriate enforcement authorities as necessary

- the volume of requests for assistance made by Canadian and international law enforcement partners to help prevent or reduce the impact of cybercrimes on Canadian businesses, in order to assess whether these requests were properly responded to by taking enforcement action or assisting victims

Our audit included a review of cybercrime files to determine whether the identified cybercrime cases were handled in a timely manner and met the organization’s own standards for response. We reviewed cybercrime files managed by the following groups:

- National Cybercrime Coordination Centre (RCMP)

- Federal Policing cybercrime unit’s investigative teams (RCMP)

- Canadian Centre for Cyber Security (Communications Security Establishment Canada)

- Compliance and Enforcement division (CRTC)

Where representative sampling was used, samples were sufficient in size to conclude on the sampled population with a confidence level of no less than 90% and a margin of error of no greater than plus 10%. Specifically,

- for the RCMP’s National Cybercrime Coordination Centre, we selected a sample of 46 victim notification files out of 384 closed files and a sample of 44 files where a request was made to coordinate cases with police partners out of 274 closed files

- for Communications Security Establishment Canada’s Canadian Centre for Cyber Security, we selected a sample of 51 incidents out of 5,341 incidents managed by the centre

Our audit also examined whether the RCMP was able to hire people with the specialized skills and knowledge needed to effectively address cybercrime. We interviewed RCMP officials tasked with managing human resources for cybercrime units. We reviewed the RCMP’s human resource policies and analyzed data on staffing levels in cybercrime positions.

The audit also looked at whether Public Safety Canada exercised leadership at the federal level to coordinate the policy response to cybercrime. We interviewed entity officials and examined whether and how Public Safety Canada coordinated efforts to establish the National Cyber Security Strategy. We also examined efforts by Public Safety Canada to coordinate the evaluation and renewal of the strategy.

We did not examine areas related to Canada’s collection of foreign intelligence or the work of the RCMP’s National Child Crime Exploitation Centre.

Criteria

We used the following criteria to conclude against our audit objective:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Federal entities intake, triage, and route reported cybercrimes and potential cybercrimes to enforcement authorities on a timely basis to manage reported incidents of suspected cybercrime activities. |

|

|

The RCMP’s Federal Policing branch identifies, prioritizes, and responds to the cybercrime occurrences that are within its mandate. |

|

|

The RCMP’s National Cybercrime Coordination Centre provides national police services to support Canadian and international law enforcement agencies in responding to cybercrime. |

|

|

The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) and the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security collaborate with law enforcement partners to support investigations related to cybercrime. |

|

|

The CRTC identifies, prioritizes, and responds to violations of Canada’s anti‑spam legislation that may enable cybercrimes. |

|

|

Public Safety Canada leads federal public safety entities’ efforts in establishing strategic priorities to address cybercrime and in measuring progress against them. |

|

|

Selected entities are using transparent, clear, and useful information to measure and demonstrate their level of success in identifying and responding to cybercrime. |

|

|

Selected entities conduct strategic human resource planning to ensure they have the right people with the right skills, in the right place, and at the right time to respond to cybercrime. |

|

|

Selected entities recruit and retain people with skills, knowledge, and diversity to conduct and support cybercrime investigations. |

|

|

Selected entities apply diversity and inclusion criteria in their human resource planning, recruiting, hiring, and retention processes and have met their respective targets. |

|

|

Selected entities promote, target, and implement outreach activities to educate Canadians on cybercrime risks. |

|

|

Federal entities provide client-centric mechanisms to encourage public reporting of cybercrime occurrences. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period from 1 April 2020 to 31 March 2023. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies. However, to gain a more complete understanding of the subject matter of the audit, we also examined certain matters that followed the end date of this period.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 24 May 2024, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

This audit was completed by a multidisciplinary team from across the Office of the Auditor General of Canada led by Sami Hannoush, Principal. The principal has overall responsibility for audit quality, including conducting the audit in accordance with professional standards, applicable legal and regulatory requirements, and the office’s policies and system of quality management.

Recommendations and Responses

Responses appear as they were received by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada.

In the following table, the paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report.

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

7.20 The RCMP’s National Cybercrime Coordination Centre should establish procedures to identify the most urgent victim notifications and ensure that they are sent first. The centre should set formal expectations for how fast victim notifications are sent, measure against these standards, and ensure that they are met. |

The RCMP’s response. Agreed. While most high priority victim notifications are actioned within 24 hours, the RCMP National Cybercrime Coordination Centre (NC3) will establish and formalize standard procedures to define the level of priority for victim notifications. The NC3 will apply a formal service standard and prioritization process for victim notifications by September 2024. This timeframe aligns with the planned full implementation of the National Cybercrime Solution, which will include new capabilities to systematically measure NC3 operational activities. The NC3’s victim notification procedures continue to evolve since the program’s initial operating capability in 2020. These notifications are an essential component of NC3 and Canadian law enforcement efforts to reduce the harm caused by cybercrime to Canadian organizations. The NC3 and Canadian law enforcement partners have participated in international law enforcement operations to notify cyber victims, such as the takedown of Hive ransomware infrastructure in 2023. These efforts prevent or mitigate ransomware payouts and contribute to protecting Canada’s economy from ransomware and other cyber intrusions. |

|

7.24 The RCMP’s National Cybercrime Coordination Centre should ensure that all requests for assistance received from domestic and international partners are fully documented and completed so that all necessary information is provided as part of the response. The centre should share requests as appropriate with all organizations implicated by the request. |

The RCMP’s response. Agreed. The RCMP National Cybercrime Coordination Centre (NC3) will ensure that all requests for assistance received from domestic and international law enforcement partners are fully documented and completed, and that the NC3 shares information as appropriate with relevant organizations. Since its initial operating capability in 2020, the NC3 has enhanced its ability to coordinate and share information with partners, while adhering to originator consent and other requirements for information sharing. The NC3 also engages its partners to seek feedback on NC3 services, such as through annual surveys. Based on survey results, most active partners are satisfied or highly satisfied with NC3 services. By September 2024 and following the full implementation of the National Cybercrime Solution, the NC3 will be better equipped fully meet the needs of its domestic and international law enforcement partners, including more comprehensive audit tracking capabilities for operational requests, and enhanced information sharing capabilities. |

|

7.30 The RCMP’s Federal Policing branch should ensure that a consistent triage process is managed centrally and is followed so that specialized cybercrime investigative resources are focused on the most serious cybercrime investigations. |

The RCMP’s response. Agreed. The RCMP recognizes that greater efforts are required to ensure that Federal Policing specialized cybercrime investigative resources are focused on the most serious cybercrime investigations. As such, Federal Policing Cybercrime has initiated an oversight process to regularly monitor compliance with the use of the Occurrence Triage Aid for all new files (i.e. occurrences). The Occurrence Triage Aid, which was launched across Federal Policing in 2020, was specifically designed to guide investigators through a standardized, comprehensive assessment process while also capturing potential impediments such as a lack of resources or expertise. Implementing a structured monitoring process at the Program-level will serve to monitor compliance and ensure that resources are focused on the most serious cybercrime investigations, while also capturing key data to inform decision-making and accountability. In addition, Federal Policing Cybercrime has developed an Action Plan for implementation across Cybercrime Investigative Teams to ensure compliance with the Federal Policing mandate. Federal Policing Cybercrime is confident that with a clear mandate, a well‑defined governance model, and improved coordination of activities performed by the Cybercrime Investigative Teams, results will be aligned under the Federal Policing mandate and focused on the most serious cybercrime threats. |

|

7.31 The RCMP should ensure that its information management systems capture accurate and complete data to assess performance, improve decision making, and demonstrate value for money for the work done by its Federal Policing branch’s cybercrime unit. |

The RCMP’s response. Agreed. RCMP Federal Policing commits to working with the Policy Centre for the RCMP’s Operational Records Management System (RMS), known as the Police Reporting and Occurrence System, to develop means to improve data accuracy and completeness in relation to cybercrime investigations. Federal Policing has initiated discussions with the Policy Centre to explore means to improve reporting within the RMS. The timeframe for the development and implementation of the identified solutions will depend on their individual complexity. In addition to efforts to improve data within the RMS, Federal Policing will continue to develop means to enhance comprehensive operational reporting, while also improving data accuracy. Specifically, the anticipated launch of a new Investigative Progress Report will serve to improve completeness of operational data by providing access to data throughout all stages of an investigation, improving accountability and enabling evidence-based decisions based on timely, accurate and complete data. The Investigative Progress Report pilot phase will initiate in Summer 2024 and is anticipated to be rolled out across Federal Policing in Winter 2024/25. Furthermore, the RCMP Federal Policing commits to working with the Policy Centres for the RCMP’s Human Resource management system (HRMIS), financial reporting systems (TEAM) and operational RMS to develop indicators that demonstrate value for money (i.e. return on investment), establish standard methodologies, and identify current reporting capabilities and limitations to in relation to those indicators. |

|

7.50 The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission should ensure that it has clear policies and procedures outlining when and under what circumstances information it acquires will be shared with law enforcement. |

The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission’s response. Agreed. The CRTC, along with the Competition Bureau and the Office of the Privacy Commissioner, is responsible for a civil regulatory regime that promotes and monitors compliance with Canada’s anti‑spam legislation (CASL). There are clear legal and privacy constraints to disclosing information from civil regulatory bodies to criminal law enforcement agencies. The CRTC will review its procedures to ensure that it clearly outlines when it could override privacy protections and disclose information to criminal law enforcement agencies while remaining in compliance with applicable laws. This will be completed by the end of the fiscal year 2024‑25. The CRTC also commits to working with its CASL partners to clearly:

|

|

7.51 The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission should ensure that roles and responsibilities of officials responsible for enforcement comply with the requirements of the legislation. Further, it should ensure that only “designated persons” under Canada’s anti‑spam legislation make key decisions as part of their role to enforce the legislation. |

The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission’s response. Agreed. In 2023, the CRTC developed and implemented a comprehensive protocol that clarifies roles and responsibilities for those involved in CASL compliance investigations. The CRTC also hired an external expert to deliver mandatory training to employees in the 2024‑25 fiscal year. The CRTC will continue to ensure that roles and responsibilities of officials responsible for CASL compliance investigations comply with the requirements of the legislation and that only “designated persons” make key decisions. |

|

7.58 The RCMP should improve its information management systems and practices so that it can consistently match reports received by the Canadian Anti‑Fraud Centre to actions taken. This will allow the RCMP to track progress on high‑priority cases and identify effective approaches used. |

The RCMP’s response. Agreed. The RCMP Canadian Anti‑Fraud Centre (CAFC) will ensure that it tracks and accounts for all actions taken to address fraud and cybercrime incidents that are reported to the CAFC. Cybercrime and fraud victim reporting is critical for law enforcement, as it informs police actions to tackle these prolific and serious types of crime. At a national level, law enforcement action may include the identification of new cybercrime threats, referrals to local police, engagement with industry partners to disrupt threats, prevention tactics to reduce further victimization, among other objectives. When actionable, the CAFC conducts follow‑up activities for most high priority victim reports. The CAFC recognizes that new technical capabilities are required to improve systematic tracking of victim reports. In 2024, the CAFC and the RCMP National Cybercrime Coordination Centre will implement a new National Cybercrime and Fraud Reporting System to improve victim reporting at a national level for law enforcement purposes. The online reporting system will include new technical capabilities for the CAFC to systematically link victim reports with follow‑up activities. |

|

7.64 The RCMP should conduct an analysis to understand its challenges in recruiting and retaining staff for specialized cybercrime positions. It should use the results to guide future recruiting and retention efforts to increase its capacity to address cybercrime |

The RCMP’s response. Agreed. Federal Policing has developed a strategy for recruiting and developing cyber expertise. The RCMP will also address recruitment and retention challenges as part of future efforts to enhance capacity to fight cybercrime over the next two to three years, and as part of broader modernization initiatives, including finding efficiencies in the selection process for the Civilian Criminal Investigator Program and exploring how initiatives such as the Experienced Police Officer Program may help to address these challenges. Despite the cyber skills talent gap, the RCMP continues to recruit individuals with specialized cyber skills, such as through the Civilian Criminal Investigator Program as well by leveraging CO‑OP opportunities to attract new talent. Training is another strategic tool in the RCMP’s recruitment and retention efforts. The Federal Policing Training Program provides a training guide for all Investigators, including those working in cybercrime, which was shared nationally at the end of January 2024. It also leverages other training opportunities offered by external partners and the RCMP’s Canadian Police College. Additionally, the RCMP National Cybercrime Coordination Centre has launched the Cyber Learning Portal which provides cyber-focused resources for RCMP employees in support of cyber investigations. |

|

7.69 The RCMP should ensure that the problems experienced with the National Cybercrime Solution’s system features aligning with user needs are overcome so that the project meets all of its requirements. It should also implement effective risk responses and contingency plans so that the project is delivered on budget and within the revised timeline. |

The RCMP’s response. Agreed. The RCMP will ensure that National Cybercrime Solution (NCS) challenges are mitigated, and that user needs align with system requirements by March 2025. The NCS is a major technological initiative that will provide the RCMP and the Canadian law enforcement community with new capabilities to support multi-jurisdictional cybercrime investigations. Initiated at the onset of the COVID‑19 pandemic, the NCS is a complex initiative and includes novel procurement and system approaches for the RCMP. The implementation of the new solution has undergone challenges and delays. To mitigate these risks, the RCMP sought an independent review of the NCS. While the review cited the NCS as a pathfinder initiative with good practices, it included recommendations related to resource constraints, systems delivery assurance, user requirements, and knowledge transfer activities. The RCMP will address these recommendations to mitigate risks with the ongoing implementation of the NCS, and will continue to work with partners to ensure the solution meets partner needs and aligns with Government policies for user‑centric digital services, now through March 31, 2025. |

|

7.77 Because violations of Canada’s anti‑spam legislation can be linked to cybercrime, Public Safety Canada should include the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission in the development of Government of Canada initiatives to address cybercrime. |

Public Safety Canada’s response. Agreed. Public Safety Canada agrees with this recommendation. The Department consults relevant departments and agencies extensively as part of its regular policy development processes. Public Safety Canada will explore further opportunities to include the Canadian Radio-television and Television Commission in the policy development processes, noting that while they are a regulatory body, there are procedures that can be leveraged to enable their participation in Cabinet Confidence discussions. With respect to the new National Cyber Security Strategy, Public Safety Canada is taking the necessary steps to ensure a whole‑of‑government approach that also considers the views and needs of all Canadians. In summer 2022, Public Safety Canada led a public consultation to provide Canadians an opportunity to voice what they would like to see the Government of Canada focus on during the development of the new Strategy. As Public Safety Canada continues to finalize the Strategy, it will continue to consult broadly, including, where possible, with the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission. |

|

7.78 Public Safety Canada, the RCMP, Communications Security Establishment Canada, and the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission should work together to ensure that cybercrimes reported by Canadians and Canadian businesses are routed to the organization with the mandate to address them. |

Public Safety Canada’s response. Agreed. Public Safety Canada agrees with this recommendation. As the Government lead for cyber security policy, Public Safety Canada works closely with departments and agencies to promote coordination and information sharing across necessary departments and agencies in an efficient and timely manner. Information is shared at all levels through various mechanisms, such as regular committee meetings that involve the broader cyber security community. The RCMP’s response. Agreed. The RCMP will continue to work with federal partners to ensure that reported cybercrimes are routed to appropriate federal organizations. The RCMP recognizes that victim reporting is critical to addressing cybercrime, and that many incidents go unreported to law enforcement. The RCMP continues to conduct outreach activities with private sector organizations, vulnerable groups and other communities to improve victim reporting, and to encourage the role of law enforcement in cyber incident response plans. The implementation of the new National Cybercrime and Fraud Reporting System in 2024 will make it easier for victims to report incidents to law enforcement at a national level. The RCMP also recognizes that greater efforts are required to harmonize operational activities across the federal community for cyber incident response, including ways to streamline and simplify how victim organizations and individuals report and receive support from the RCMP and its federal partners. The RCMP will continue to work closely with its federal partners in 2024 and ongoing to improve reporting and response services for victims of cybercrime. Communications Security Establishment Canada’s response. Agreed. Communications Security Establishment Canada agrees with this recommendation and offers the following management action plans:

The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission’s response. Agreed. The CRTC, along with the Competition Bureau and the Office of the Privacy Commissioner, is responsible for a civil regulatory regime that promotes and monitors compliance with Canada’s anti‑spam legislation (CASL). The CRTC does not have authority to investigate cybercrime. It also does not have the mandate or ability to assess whether complaints give rise to conduct that is criminal in nature. The CRTC commits to working with partners to clearly:

|