The Environment and Sustainable Development Guide

Integrating Environmental and Sustainable Development Considerations in Direct Engagement Work

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Background and Context

- Audit Guidance: Section 1—Strategic Audit Plans

- Audit Guidance: Section 2—Planning a Direct Engagement

- Appendices:

- Appendix 1—Overview of the Potential Impact of Human Activities on the Environment

- Appendix 2—Assessing the Significance of Environmental and Sustainable Development Risks

- Appendix 3—Background and Resources

- Appendix 4—The Built Environment: Hazards to Human Health and Well-Being

- Appendix 5—Canada’s International Commitments on the Environment and Sustainable Development

Introduction

Purpose

The purpose of this guide is to help auditors identify and assess environmental and sustainable development risks that could be associated with the programs, activities, or Crown corporations they audit.

At the Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG), we audit the federal government and the governments of the northern territories. We examine significant issues and report what we find to Canada’s Parliament and the northern legislative assemblies. We also conduct special examinations of federal Crown corporations and report our findings to their boards of directors. We are thus in a good position to inform parliamentarians and Canadians about whether entities are considering the environmental and sustainable development consequences of their activities appropriately.

This guide provides information to support the identification and assessment of environmental and sustainable development risks as part of

- the strategic audit planning process,

- the planning of a performance audit, and

- the planning of a special examination.

Applicability and audience

The guidance presented in this guide applies to the direct engagement practice and was designed for OAG audit staff.

Auditors’ responsibilities

Teams that are preparing or revising strategic audit plans for specific entities or for sectoral (government-wide) topics are required to consult the Internal Specialist—Environment and Sustainable Development (ESD).

Teams that are planning direct engagements are required to consult the Internal Specialist—ESD, except for special examination teams that are auditing a Crown corporation assessed by the Internal Specialist—ESD as having low environmental and sustainable development risks.

See Section 1 and Section 2 below for more information on strategic audit planning and direct engagement planning.

How to use the guide

Teams use this guide to help them identify and assess environmental and sustainable development risks and complete required templates as part of the strategic audit planning process and the planning of a performance audit or special examination:

- See Section 1 if you are preparing or revising a strategic audit plan.

- See Section 2 if you are starting to plan a performance audit or a special examination.

Important information about federal environmental and sustainable development policies, guidelines, and authorities is presented in the appendices:

- Appendix 1 provides information on the impact of human activities on the environment.

- Appendix 2 provides guidance on assessing the significance of environmental and sustainable development risks.

- Appendix 3 provides background information and resources on important issues and legal authorities relevant to environment and sustainable development.

- Appendix 4 discusses hazards to human health associated with the built environment.

- Appendix 5 provides information and resources on Canada’s international environmental and sustainable development commitments.

The Internal Specialist—ESD is available to support teams when they use the guide.

Background and Context

The environment and sustainable development and our audit mandate

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG or the Office) is empowered by the Auditor General Act to examine the economy, efficiency, and effectiveness of government expenditures in performance audits. The OAG is also empowered to examine whether the government has given due regard to the environmental effects of its expenditures in the context of sustainable development.

Under section 134(2) of the Financial Administration Act, the Auditor General is to be appointed auditor or joint auditor of a Crown corporation and conducts special examinations. The purpose of a special examination is to determine whether the systems and practices we selected for examination are providing the corporation with reasonable assurance that its assets are safeguarded and controlled, its resources are managed economically and efficiently, and its operations are carried out effectively, as required by section 138 of the Financial Administration Act. The environment is one area for which systems and practices are commonly examined.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

The United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were adopted in September 2015 by the 193 member states of the United Nations (UN), including Canada (Exhibit 1). The SDGs cover environmental, social, and economic concerns and are to apply to all nations, large or small, insular or landlocked, developed and developing. Countries can use the SDGs, targets, and indicators as a framework to guide their own policies and action plans. The SDGs have been recognized as a focus for the International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions (INTOSAI) and included in the INTOSAI Strategic Plan 2017–2022 as one of five crosscutting priorities: Crosscutting priority 2: “Contributing to the follow-up and review of the SDGs within the context of each nation’s specific sustainable development efforts and SAIs’ individual mandates.”Footnote 1 This contribution is expected to develop and change over time as the SDG cycle advances.

Exhibit 1: United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

Goal 1: End poverty in all its forms everywhere

Goal 2: End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture

Goal 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages

Goal 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all

Goal 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls

Goal 6: Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all

Goal 7: Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all

Goal 8: Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all

Goal 9: Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization and foster innovation

Goal 10: Reduce inequality within and among countries

Goal 11: Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable

Goal 12: Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns

Goal 13: Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts

Goal 14: Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development

Goal 15: Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss

Goal 16: Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels

Goal 17: Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development.

Notes:

See the website on the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

See the guidelines for reusing the United Nations images.

Source: Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

The Office is committed to contributing, through its audit work and consistent with its mandate, to the federal government’s implementation of the SDGs. The Office’s sustainable development strategy also reflects this engagement. To fulfill this commitment and in line with the direction provided by INTOSAI, this guide helps direct engagement teams to consider sustainable development using the SDGs as they prepare strategic audit plans and plan audits or special examinations. The SDGs define sustainable development and provide a structure for integrating sustainable development considerations into the Office’s audit work. More information is provided in Audit Guidance: Section 1—Strategic Audit Plans and Audit Guidance: Section 2—Planning a Direct Engagement.

The role and influence of government and of Crown corporations

Through their policies, programs, and legal authorities, as well as the billions of dollars they spend each year, the federal and territorial governments and Crown corporations have a significant influence on almost every aspect of Canadian society and can play a key role in advancing environmental protection and sustainable development.

The activities of the federal entities and territorial governments can affect the environment and sustainable development in two ways:

- directly (i.e., through their own operations); or

- indirectly (i.e., through the control or influence they exert on the activities of others through their policies, plans, and programs).

Within the context of a strategic audit plan or a direct engagement, it is important to consider how federal activities may pose a risk to the environment and sustainable development. This is the starting point for any evaluation of risks related to ESD.

Key terms and concepts

For the purposes of this guide, the term “environment” encompasses the natural environment and the built environment.

When we think of the environment, we generally think of the natural environment that surrounds us—the air, water, and land, as well as the diversity of plants, animals, and other organisms that inhabit our planet. It includes renewable resources such as timber and fisheries, and non-renewable resources such as minerals, oil, and gas. Natural ecosystems serve a variety of functions that provide people with necessary and valuable benefits. For example, ecosystems provide clean water, maintain healthy and productive soil, pollinate wild plants and crops, and provide materials like wood and natural spaces for recreation. These are referred to as “ecosystem goods and services.” We could not survive without them.

The built environment includes both the buildings in which people spend their time (at home, school, the workplace, recreational facilities, shops and malls, etc.) and the broader built environment of human settlements (villages, towns, suburbs, and cities) and related infrastructure. North Americans spend close to 90 percent of their time indoors.

Human beings are not immune from the effects of negative changes to the environment. A variety of pollutants are emitted from resource development, industrial processes, vehicle exhaust, agricultural activities, etc. While they degrade the quality of the environment, exposure to pollutants can also lead to a number of health impacts. These range from minor problems to premature death.

We are also affected by our built surroundings. Environmental conditions inside buildings where we live, work, and play can also play a significant role in health and well-being.

Information on human activities and impacts on the environment is provided in Appendix 1. For hazards related to the built environment, refer to Appendix 4.

Section 2 of the Auditor General Act includes the definition of sustainable development from the 1987 report of the World Commission on Environment and Development, Our Common Future, also known as the Brundtland Report:

“Sustainable development” means development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

Section 21.1 of the Act expands on this definition:

Sustainable development . . . is a continually evolving concept based on the integration of social, economic and environmental concerns, and which may be achieved by, among other things,

-

- the integration of the environment and the economy,

- protecting the health of Canadians,

- protecting ecosystems,

- meeting international obligations,

- promoting equity,

- an integrated approach to planning and making decisions that takes into account the environmental and natural resource costs of different economic options and the economic costs of different environmental and natural resource options,

- preventing pollution, and

- respect for nature and the needs of future generations.

The United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development also provides a definition of sustainable development through its concrete and structured goals and targets. These goals and targets deal with the means required to work toward sustainable development.

Audit Guidance: Section 1—Strategic Audit Plans

Assessing major risks is where effective strategic audit planning begins. When developing or updating strategic audit plans, auditors consider environment and sustainable development (ESD) risks along with other business risks.

This section of the guide provides guidance on

- strategic audit planning for individual entities and for sectoral topics, and

- steps for incorporating ESD risks into a strategic audit plan.

Teams that are preparing strategic audit plans for specific entities are required to complete the Environment and Sustainable Development Risk Profile for Strategic Audit Planning and consult with the Internal Specialist—ESD. Sign-off by the Internal Specialist is mandatory.

Teams that are preparing strategic audit plans for sectoral (government-wide) topics are required to consult with the Internal Specialist—ESD to discuss significant sustainable development risks, based on the United Nations sustainable development goals, that may be relevant to the topics in their strategic audit plans. Teams may wish to review and/or complete the template, as it provides a framework to identify and assess ESD risks at a high level. Consultation with the Internal Specialist—ESD is mandatory, but completion of the template is not mandatory.

Strategic audit planning

Teams complete the Environment and Sustainable Development Risk Profile for Strategic Audit Planning and consult with the Internal Specialist—ESD. This provides for a systematic approach to performing high-level assessments of an entity or sector ESD risks by

- identifying an entity’s strategic outcomes or key activities related to a sectoral topic and associated policies, programs, and operations;

- identifying potential associated ESD effects; and

- assessing the risks to determine whether they are significant.

If any significant ESD risks are identified, they are incorporated into the overall risk profile for the strategic audit plan.

Completing the Environment and Sustainable Development Risk Profile for Strategic Audit Planning

Step 1: Review key documents and resources

To become familiar with ESD issues and authorities that may be relevant for an entity or to the sectoral topic, consider the following:

- potential impact of specific activities on the environment;

- the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals;

- commitments made in the Federal Sustainable Development Strategy as well as the entity’s sustainable development strategy;

- infrastructure and other projects;

- facilities management and other aspects of government operations;

- hazards associated with the built environment;

- policy, plan, or program proposals that require the approval of a Minister or Cabinet, and associated strategic environmental assessments;

- funding and other financial assistance activities;

- international environmental and sustainable development commitments; and

- environmental petitions submitted to the Office of the Auditor General of Canada by residents of Canada.

Note

Some teams find it useful to review the ESD section of the Functional Risk Identification Template when they analyze ESD risks for their entities or sectoral topic, as this template contains useful questions to consider.

Step 2: Complete columns 1 to 3 of the Environment and Sustainable Development Risk Profile for Strategic Audit Planning

Summarize strategic outcomes or key activities and related program activities and sub-activities:

- Identify an entity’s strategic outcomes and related program activity for entity-specific strategic audit plans, or key activities relevant to the sectoral area, and enter this information in column 1 of the Environment and Sustainable Development Risk Profile for Strategic Audit Planning. Use as many rows as you need.

- Enter related program sub-activities in column 2.

- Summarize key related policies, programs, projects, or operations for each program sub-activity. Focus only on major initiatives and describe them very briefly in column 3.

Step 3: Identify potential environment and sustainable development effects

Determine which ESD effects may result from the policies, programs, or other activities that you noted in columns 1, 2, and 3. Review columns 4 to 12 of the risk profile and mark those that could be relevant with an “x” or check mark.

Keep in mind that the government may affect the environment directly (through its own operations and activities) or indirectly (through the control or influence it has on others through its policies and programs).

Note

For more information about human activities and their potential impact on the environment, see Appendix 1. A list of environmental issues associated with government operations is contained in Appendix 3. Teams should also consult Appendix 4—The Built Environment: Hazards to Human Health and Well-Being.

A newly added element to the Environment and Sustainable Development Risk Profile for Strategic Audit Planning is consideration of the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals.

- An entity, through its programs and policies, has an influence on achieving one or more of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals and associated target(s). Identify the goal(s) and associated target(s) that relate to the entity or to the sectoral topic. See column 4 of the Environment and Sustainable Development Risk Profile for Strategic Audit Planning.

Other elements covered in the Environment and Sustainable Development Risk Profile for Strategic Audit Planning are environmental effects:

- Effects on air, water, and land. These kinds of effects could result from releases into the environment (e.g., pollution) or physical changes (e.g., erosion from forestry activities).

- Air effects include climate change and other air quality issues, such as ozone layer depletion, smog, and acid rain. See column 5.

- Water effects cover fresh water and the marine/coastal environments. They include changes to water quality and quantity, as well as effects on aquatic animals and plants (biodiversity) or their habitats. See column 6.

- Land effects include changes to soil, habitats, and biodiversity, as well as contaminated sites. See column 7.

- Generation, handling, or discharge of hazardous materials. Such actions are known to have harmful effects on human health and the environment. See column 8.

- Environmental emergencies. These include accidents that may cause releases into aquatic or terrestrial ecosystems. Some occur on land (e.g., at rail or nuclear facilities) and others on water (e.g., shipping accidents). See column 9.

- Depletion or degradation of natural resources. See column 10. Examples include

- consumption and use of natural resources and their derivatives;

- degradation and other changes resulting from the harvesting, extraction, or processing of these resources; and

- the generation of waste.

- The built environment (buildings/infrastructure). See column 11. Examples of effects that would have an impact on human health and well-being associated with the built environment include

- degraded indoor air quality;

- degraded drinking water quality;

- fires or explosions; and

- other unsafe conditions related to structural integrity, poor building conditions, etc.

Note

A description of some hazards associated with the built environment is provided in Appendix 4.

- Other effects. Other environmental issues may not be covered in the environmental risk profile. If so, put a check mark in column 12 and describe them in the comments section.

Step 4: Analyze the level of risk to determine significance

To assess risk, we look at the likelihood of occurrence and the severity of the resulting effects (consequences). We also take management controls into consideration. If some are in place, they might affect the level of risk.

For effects identified in the ESD risk profile, proceed as follows:

- Estimate the seriousness or severity of the ESD effect (taking any controls into account) and enter the rating (Low, Medium, or High). See column 13.

- Estimate the likelihood of occurrence (taking any controls into account) and enter the rating (Low, Medium, or High). See column 14.

Consider these two factors together to determine if the risk is significant (check Yes or No). See column 15.

If different kinds of major ESD effects have been identified for a program sub-activity, it may be necessary to assess their level of risk separately.

Refer to Appendix 2—Assessing the Significance of Environmental and Sustainable Development Risks to determine the appropriate ratings.

Step 5: Provide comments

In the comments section, explain how you arrived at your conclusions about the risk ratings. In addition, include any other information that was important to your analysis. With regard to the SDGs, teams comment on the alignment (good fit) of the entity’s mandate or sectoral topic with SDG(s) and associated target(s) and whether there are measureable indicator(s). Teams should discuss with each entity in order to better understand the entity’s awareness of the SDGs, as well as its responsibilities, and its plan to contribute to specific goals.

Step 6: Request Internal Specialist—ESD review and sign-off

Provide a copy of the completed environmental risk profile to the Internal Specialist and arrange a meeting to discuss your assessment and risk ratings.

Contact the Internal Specialist—ESD at any point for advice on completing the ESD risk profile.

Steps for incorporating environmental and sustainable development risks into a strategic audit plan

When significant ESD risks are identified, they are assessed in conjunction with other business risks identified during strategic audit planning.

The following are possible options for reflecting important ESD issues in a strategic audit plan:

- a full performance audit of an ESD issue,

- an ESD line of enquiry (LOE) within a performance audit,

- a horizontal audit that focuses on one or more ESD issues, or

- an ESD LOE within a horizontal audit.

Audit Guidance: Section 2—Planning a Direct Engagement

This section of the guide is intended to help teams determine if there are any environment and sustainable development (ESD) issues related to the subject matter of their audit and, if so, to help them evaluate whether the issues are significant and should be included in the audit scope.

Performance audits

Teams start to identify and assess ESD risks associated with the subject matter of the audit when they complete the Office of the Auditor General of Canada's Functional Risk Identification Template (FRIT). Risk-screening questions listed in the Environment and Sustainable Development (ESD) section of the FRIT highlight areas where ESD risks could lie. After they have completed the ESD section, teams consult the Internal Specialist—ESD for advice to determine whether potential ESD risks should be explored further. Sign-off of the ESD component of the FRIT by the Internal Specialist—ESD is mandatory.

In cases where the screening questions and consultation with the Internal Specialist—ESD indicates ESD risks associated with the subject matter being audited, teams can decide to give further consideration to the risk area using the Subject Matter Assessment of Risk Template (SMART).

Considering sustainable development using the Sustainable Development Goals

The Office requires performance audit teams to identify Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and associated target(s) in the Audit Report Submission. As teams define the scope of the subject matter during the planning phase, they are now required to have a second look at SDGs when completing the FRIT. If the subject matter and SDG(s), plus associated target(s) are well aligned (good fit) and the associated indicator is measurable, teams can decide to pursue exploration using the SMART, as explained above. Teams can consider

- the value added of including the relevant SDG, target, and indicator in the audit scope and using the United Nations (UN) Agenda 2030 as a source of criteria;

- links between the relevant SDG, target, indicator, and Canada-specific goals, targets, actions, and measurable indicators that the federal government has committed to in the Federal Sustainable Development Strategy 2016–2019 and using the Strategy as an additional source of criteria;

- awareness and preparedness of the entity in relation to the relevant SDG, target, indicator, and data availability. Questions could be discussed with the entity, such as

- Is the entity aware of the UN Agenda 2030 and its 17 SDGs?

- Is the entity responsible for delivering on any goal, target, and indicator in relation to the subject matter being audited?

- Has the entity done any work on aligning its relevant program or activity with any SDG, target, and indicator?

- Does the entity collect data on a relevant indicator?

- Office direction in terms of commitment to contribute, through its audit work, to the implementation of the SDGs by the federal government. See the Office's sustainable development strategy.

Next steps

Based on the planning phase information, teams can decide to include ESD issues in the scope of their audits. It could be having a specific line of enquiry (LOE) or including ESD questions as part of an LOE. Note that the SDGs, targets, and indicators are recent, so teams examining relevant goals, targets, and indicators can expect to focus their audit work on questions about the entity’s preparedness: the entity’s role, plan, and process to deliver on the goal. Where SDGs have been integrated in the Federal Sustainable Development Strategy 2016–2019, examination work is more likely to focus on concrete actions and results achieved. Audit work will develop and change over time as the SDG cycle advances. The Internal Specialist—ESD is available to provide advice on audit objectives, lines of enquiry, and audit criteria and questions.

The following example (Exhibit 2) illustrates how the template can help identify ESD risks. For background information and helpful links to documents and electronic resources, see Appendices 1 to 5.

Exhibit 2: Example—Drinking water in First Nations communitiesFootnote 2

Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) and Health Canada provide funding and support to assist First Nations in making drinking water available to their communities. INAC assists First Nations in identifying infrastructure needs and submitting project proposals; provides funding and advice on the design, construction, operation, and maintenance of water treatment facilities; and provides funding to train First Nations staff such as water treatment plant operators. Health Canada supports First Nations in the monitoring and testing of tap water to demonstrate that it is safe for drinking. Through funding arrangements, First Nations are responsible for the construction, upgrade, and day-to-day management of water systems.

During the planning phase of an audit, the audit team starts to explore environmental and sustainable development risks associated with the subject matter of the audit (for example, drinking water in First Nations Communities) by completing the Environment and Sustainable Development section of the Functional Risk Identification Template (FRIT). When answering the questions in that template, the team might identify some of the following risks:

- human health risks associated with unsafe drinking water;

- gaps in the regulations for drinking water on reserves;

- improper training of First Nations operators of water treatment facilities.

Auditors would also identify

- specific targets and indicators from the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, and

- goals and targets from the Federal Sustainable Development Strategy.

United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 6: Clean Water and SanitationFootnote 3

- Target 6.1—“By 2030, achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all”;

- Indicator 6.1.1—“Proportion of population using safely managed drinking water services”;

- Target 6.b—“Support and strengthen the participation of local communities in improving water and sanitation management”; and

- Indicator 6.b.1—“Proportion of local administrative units with established and operational policies and procedures for participation of local communities in water and sanitation management.”

Federal Sustainable Development Strategy Goal 10: Clean Drinking WaterFootnote 4

- Medium-term target—“By March 31, 2019, 60% and by March 31, 2021 100% of the long-term drinking water advisories affecting First Nation drinking water systems financially supported by Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada are to be resolved.”

The team would also identify issues raised by Canadian residents through the petitions process managed by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada. In this case, the team would identify any issues raised in petitions directed to INAC and Health Canada; for example, Petition 275: Progress toward meeting drinking water quality standards on Indian reserves.

The team would then consult the Internal Specialist—Environment and Sustainable Development (ESD) and could decide to further consider the significance of these issues using the Subject Matter Assessment of Risk Template (SMART). Finally, the team could decide to include ESD issues in the audit scope by

- adding an ESD line of enquiry within the performance audit, or

- including ESD issues in a line of enquiry.

Special examinations

The Internal Specialist—ESD has prepared a Preliminary Assessment of Environment and Sustainable Development Risks—Crown Corporations. Teams that are conducting special examinations first review this risk assessment during the planning phase.

When the Internal Specialist has assessed a Crown corporation as having a low overall risk, teams are not required to complete the ESD component of the Office of the Auditor General of Canada's Functional Risk Identification Template (FRIT) or to consult with the Internal Specialist.

When the Internal Specialist has assessed a Crown corporation as having an overall risk of either high or medium, teams start to identify and assess ESD risks associated with the subject matter of the special examination when they complete the FRIT. Risk-screening questions listed in the Environment and Sustainable Development section of the FRIT highlight areas where ESD risks could lie. After they have completed the Environment and Sustainable Development section, teams consult the Internal Specialist—ESD for advice to determine whether potential ESD risks should be explored further. Sign-off of the ESD component of the FRIT by the Internal Specialist—ESD is mandatory.

In cases where the screening questions and consultation with the Internal Specialist—ESD indicate ESD risks associated with the subject matter being audited, teams can decide to give further consideration to the risk area using the SMART.

Considering sustainable development using the Sustainable Development Goals

As teams define the scope of the subject matter during the planning phase, they are asked to identify relevant SDG(s), target(s), and indicator(s) when completing the FRIT. If the Crown corporation’s mandate, corporate objectives, or strategic priorities and relevant SDG(s) and associated target(s) are well aligned (good fit), teams can decide to pursue exploration using the SMART, as explained above. Teams can consider

- the value added of including the relevant SDG and target in the audit scope and using the UN Agenda 2030 as a source of criteria; and

- awareness of the Crown corporation in relation to the relevant SDG, target, and indicator. Questions could be discussed with the Crown corporation, such as

- Is the Crown corporation aware of the UN Agenda 2030 and its 17 SDGs?

- Has the Crown corporation identified any goals and targets that are linked to its mandate?

- Has the Crown corporation done any work on aligning its programs or activities with any SDG, target, and indicator?

- Office direction in terms of commitment to contribute, through its audit work, to the implementation of the SDGs by the federal government. See the Office's sustainable development strategy.

Next steps

Based on the planning phase information, teams can decide to include ESD issues in the scope of their audits. It could be having a specific LOE (on environmental risk management, for example) or including ESD criteria and questions as part of an LOE (on governance or operations, for example). The Internal Specialist—ESD is available to provide advice on audit objectives, LOE, and audit criteria and questions.

Appendix 1—Overview of the Potential Impact of Human Activities on the Environment

Within the context of a strategic audit plan or audit subject matter, it is important to consider how the government’s or Crown corporation’s activities may pose a risk to the environment. This is the starting point for any evaluation of environmental risks.

As we noted earlier in this guide, the activities of the federal and territorial governments and Crown corporations can affect the environment in two ways:

- directly (i.e., through their own operations); or

- indirectly (i.e., through the control or influence they exert on the activities of others through their policies, plans, and programs).

The term “environment” encompasses the natural environment and the built environment. See Key terms and concepts for more information on the environment and the connections between human health and well-being and the environment.

For information on risks associated with the built environment, see Appendix 4.

How human activities can have an impact on the natural environment

In general, human activities have an impact on the natural environment by

- releasing substances into the environment (e.g., emissions, discharges, and waste production);

- changing and degrading water, land, and habitats; and

- using and depleting resources.

Human activities do not necessarily cause negative effects. Some activities, such as pollution prevention, may benefit the environment and enhance sustainability.

Overview of activities

The following is an overview of the main categories of activities that have an impact on the natural environment:

- Energy—exploration, development, distribution, processing, management, consumption, or use (oil, gas, nuclear, other)

- Natural resources—development, management, harvesting (e.g., fisheries, aquaculture, forestry, hunting and trapping, mining)

- Agriculture/food production—land cultivation, animal husbandry, food processing and distribution

- Procurement and consumption of goods

- Physical infrastructure—construction or use of infrastructure, such as roads, housing, bridges, ports, buildings, railways, sewage, or waterworks

- Transportation of people and goods—road, marine, rail, or air transportation, and all related activities and infrastructure

- Toxic or hazardous substances and materials—generation, manufacture, use, management, transportation, or disposal (e.g., toxic substances and pesticides)

- New substances and organisms—development, deployment, and regulation (e.g., new chemicals, genetically modified organisms)

- New products and technologies —development and deployment

- Industrial activity—e.g., resource processing and manufacturing

- Urban development

- Military activities—training, equipment, materials, natural disasters, and other emergencies (e.g., preparation and response)

- Waste generation or management (including hazardous waste)

- International trade (export and import)

- Cleanup or remediation of contaminated sites

This is not an exhaustive list. Other activities that are not on this list may have an impact on the natural environment. Consult the Internal Specialist if you require further information.

Note

Exhibit 3 below provides detailed examples of various activities and the potential impacts of these activities on air, water, land, and biodiversity.

Exhibit 3: Human activities and examples of potential impact on the natural environment

The first part of this chart provides illustrative examples of activities that have an impact on air, water, and land, including biodiversity. The second part of the chart provides examples of the types of impacts that may result from those activities.

Examples of activities that will lead to impacts on various components of the environment

| Air | Surface water (e.g., lakes, rivers) |

Groundwater | Coastal areas / marine | Land |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Examples of potential impact

| Air | Surface water (e.g., lakes, rivers) |

Groundwater | Coastal areas / marine | Land |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Exhibit 4 lists examples of ways to avoid or minimize environmental impacts and advance environmental sustainability.

Exhibit 4: Opportunities to advance environmental sustainability

Examples of ways to avoid or minimize environmental impacts and advance environmental sustainability:

- Consider environmental issues in the early stages of decision making (e.g., when planning new projects, policies, plans, and programs).

- Reduce energy consumption and/or increase use of renewable energy sources through increased efficiency (e.g., enhanced fuel efficiency for vehicles, reduced electricity consumption by household appliances) and green building design (new buildings) or retrofitting.

- Increase the use of renewable energy sources.

- Advance, support, and employ green technologies.

- Reduce the consumption of resources.

- Increase reuse and recycling, which will reduce resource consumption, waste production, and disposal.

- Establish and maintain protected areas (terrestrial and marine).

- Improve eco-efficiency.

- Implement green procurement practices—purchasing more environmentally friendly goods and services.

- Prevent pollution by avoiding the use of hazardous/toxic materials and by using cleaner fuels, clean emission technologies for engines, and cleaner or zero-emission energy sources (e.g., solar and wind power).

- Promote sustainable certification in various sectors.

- Advance socially responsible policies and practices.

- Improve emergency planning, preparedness, and response.

- Implement environmental management systems (EMS).

- Develop environmental training programs.

Appendix 2—Assessing the Significance of Environmental and Sustainable Development Risks

To assess risk, we consider the likelihood of a risk event occurring and the magnitude of the impact (severity) of any effects that may result. The overall risk rating is a product of these two factors.

If management controls are in place, we also consider how they would mitigate or reduce the level of risk.

Overall Risk = (Impact) x (Likelihood)

Estimating the impact (the severity of the environmental or sustainable development effect)

Factors to consider when assessing the severity of an effect include

- the magnitude (ranging from little effect to loss of function);

- the location or proximity (e.g., beside important fish habitat, in a sensitive ecosystem close to human populations);

- the size or scale of effect (e.g., total area, percentage or size of animal population affected);

- the timing (e.g., during migration, spawning, nesting season);

- the duration (e.g., short-term or long-term; reversible or irreversible); and

- the socio-economic and health implications.

Use the descriptions in Exhibit 5 to determine the magnitude of the impact. Consider whether any management controls are in place. If there are, consider whether they reduce or mitigate the extent of the environmental effect, and take them into account when assigning the rating.

Exhibit 5: Impact (severity of effect)

| Level | Description |

|---|---|

| Low |

|

| Medium |

|

| High |

|

Estimating likelihood of occurrence

Use the descriptions in Exhibit 6 to determine the likelihood of the risk event occurring. If management controls are in place that could reduce the likelihood that the risk event will materialize, they should be taken into consideration when assigning the rating.

Exhibit 6: Likelihood that a risk event will occur

| Level | Description |

|---|---|

| Low | May occur but only under exceptional circumstances |

| Medium | Likely to occur at some time |

| High | Occurring or imminent |

Rating overall risk to determine significance

The overall risk rating is the product of severity and likelihood. Plot the intersection of these ratings on the risk assessment chart (Exhibit 7). Any effect that yields a risk rating in the darkest boxes of the table is considered to pose a significant environmental risk and warrants further consideration and analysis.

Exhibit 7: Risk assessment chart

| Likelihood of occurrence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impact (severity of effect) |

Low | Medium | High | |

| Low | L/L | L/M | L/H | |

| Medium | M/L | M/M | M/H | |

| High | H/L | H/M | H/H | |

The following example (Exhibit 8) illustrates the various steps involved in identifying and assessing environmental and sustainable development risks related to the subject matter of an audit.

Exhibit 8: Example of an audit of rail transportation

An audit team is planning an audit of Transport Canada’s oversight of rail transportation in Canada.

The first step is to consider the types of activities related to rail transportation. These could include the following:

- carriage of goods (hazardous and non-hazardous),

- movement of trains and cars on rail sidings, and

- track maintenance.

The next step is to examine these activities in more detail and consider their effects. For example, consider the activity “carriage of goods.” Think about the types of activities associated with transport of goods by rail and the kinds of effects that might result from these activities (on the natural environment and/or on people). They might be continuous or ongoing effects, or effects that would result if a risk event like an accident occurred. The following are some activities and related effects that could be identified:

Effects (continuous or ongoing)

- Small leaks and spills—contaminates soil or other parts of the surrounding environment, especially in areas where there is frequent use (e.g., near sidings)

- Engine emissions—degrades air quality

- Noise—has a negative impact on the enjoyment of property by residents and users of nearby buildings or other uses

Effects from an accident or derailment

- Release(s) of solid, liquid, or gaseous materials from rail cars or tank cars. The severity of the effects would depend on the characteristics of the specific commodities that are being transported and the volumes involved. Effects could include

- contamination of nearby land and water bodies;

- negative effects on flora and fauna and their habitat (aquatic and terrestrial);

- impairment of water quality for drinking, recreation, fishing, or other uses;

- migration into groundwater, with resulting degradation of groundwater quality;

- if goods are flammable or have explosive properties, fires and/or explosions could occur, leading to personal injuries and other damage, including property damage;

- damage to community infrastructure;

- damage to people’s health and safety;

- injuries to train staff.

To evaluate the overall level of risk and significance for a rail accident or derailment, take the following actions:

- Evaluate the magnitude of the impact (severity) of these effects. Assign a rating of High, Medium, or Low. The risk rating for impact is influenced by a variety of factors, as described in Exhibit 5 above.

- Evaluate the likelihood of these risks occurring. The risk rating for likelihood is influenced by a variety of factors, as described in Exhibit 6 above. Assign a rating of High, Medium, or Low. Rail transport data for commodities and accident rates would help to determine the rating for likelihood.

- Determine the overall risk rating using the risk assessment chart found in Exhibit 7.

The following table (Exhibit 9) illustrates how the final overall risk rating is estimated.

Exhibit 9: Rating environmental risks

| Potential environmental risk | Risk factors | Risk rating |

|---|---|---|

| Accident/Derailment |

Impact (severity) Some considerations affecting the risk rating:

|

Medium to High |

|

Likelihood Some considerations affecting the risk rating:

|

High | |

| Overall risk rating | M/H to H/H Significant: Yes |

Appendix 3—Background and Resources

The background information and resources contained in this appendix will help audit teams to identify and assess environmental and sustainable development risks as teams develop strategic audit plans or subject matter for their performance audits or special examinations.

This appendix provides information on the following topics:

- the federal and departmental sustainable development strategy;

- physical infrastructure and other projects that may be subject to the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012;

- facilities management and other aspects of government operations;

- funding or other financial assistance activities;

- policy, plan, or program proposals that require approval from a Minister or Cabinet (strategic environmental assessment); and

- environmental petitions, which Canadian residents submit to the Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG).

For more information on any of these topics, please consult the Internal Specialist.

Sustainable development strategies

Sustainable development strategies are important tools by which the federal government can advance sustainable development and make environmental and sustainable development decision making more transparent and accountable to Parliament. These strategies are meant to be the main vehicle to drive responsible management, from an environmental and sustainable development perspective, throughout the federal government. The strategies set out the goals, targets, and actions designed to contribute to the overall goal of furthering sustainable development.

Federal Sustainable Development Strategy

With the passage of the 2008 Federal Sustainable Development Act (under revision), the government acknowledged the need to integrate environmental, economic, and social factors in all government decision making. The Act requires that a Federal Sustainable Development Strategy (FSDS) be developed that would make environmental decision making more transparent and accountable to Parliament.

Federal Sustainable Development Strategy 2016–2019

Federal Sustainable Development Strategy 2013–2016

Federal Sustainable Development Strategy 2010–2013

The 13 aspirational goals in the FSDS 2016–2019 are

-

- Effective action on climate change

- Low-carbon government

- Clean growth

- Modern and resilient infrastructure

- Clean energy

- Healthy coasts and oceans

- Pristine lakes and rivers

- Sustainably managed lands and forests

- Healthy wildlife populations

- Clean drinking water

- Sustainable food

- Connecting Canadians with nature

- Safe and healthy communities

The FSDS contains goals, targets, and related action plans. Action plans set out what to do to achieve the targets. They include priority measures, as well as other actions that support the targets. Each target is associated with responsible ministers.

Departmental sustainable development strategies

The requirement for designated departments and agencies to prepare sustainable development strategies, then update them and present them to Parliament every three years, has existed since 1995. These same designated departments and agencies are required to respond to environmental petitions.

Since the introduction of the first FSDS in 2010, departmental sustainable development strategies must now include objectives and plans that comply with and contribute to the federal strategy. Departmental strategies have to be prepared within one year of the tabling of the federal strategy. The designated departments and agencies report on their sustainable development activities in annual departmental plans and departmental results reports, as well as on their websites. Some prepare stand-alone sustainable development strategies.

Refer to departmental sustainable development strategies, which can be accessed on the Environment and Climate Change Canada website, to check for newly developed departmental sustainable development strategies.

Strategies that were prepared by departments and agencies prior to the enactment of the Federal Sustainable Development Act can be accessed by clicking the links in Exhibit 10.

Exhibit 10: Entity sustainable development strategies (1997–2009)

Departments/agencies required to prepare sustainable development strategies (SDSs) and respond to environmental petitions

| Departments and agencies | SDS I (1997–2000) |

SDS II (2000–2003) |

SDS III (2003–2006) |

SDS IV (2007–2009) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada | I | II | III | IV |

| Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency | I | II | III | IV |

| Canada Border Services Agency | N/A | N/A | N/A | IV |

| Canada Economic Development for Quebec Regions | I | II | III | IV |

| Canada Revenue Agency | I | II | III | IV |

| Canadian Heritage | I | II | III | IV |

| Employment and Social Development Canada | I | II | III | IV |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | I | II | III | IV |

| Finance Canada, Department of | I | II | III | IV |

| Fisheries and Oceans Canada | I | II | III | IV |

| Global Affairs Canada | I | II | III | IV |

| Global Affairs Canada (formerly Canadian International Development Agency) | I | II | III | IV |

| Health Canada | I | II | III | IV |

| Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada | I | II | III | IV |

| Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada | I | II | III | IV |

| Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada | I | II | III | IV |

| Justice Canada, Department of | I | II | III | IV |

| National Defence | I | II | III | IV |

| Natural Resources Canada | I | II | III | IV |

| Parks Canada | N/A | II | III | IV |

| Public Health Agency of Canada | N/A | N/A | N/A | IV |

| Public Safety Canada | I | II | III | IV |

| Public Service Human Resources Management Agency of Canada (the new Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, part of the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, has assumed responsibility for the agency's functions) |

N/A | N/A | N/A | IV |

| Public Services and Procurement Canada | I | II | III | IV |

| Transport Canada | I | II | III | IV |

| Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat | I | II | III | IV |

| Veterans Affairs Canada | I | II | III | IV |

| Western Economic Diversification Canada | I | II | III | IV |

Federal organizations that voluntarily prepare strategies

| Departments and agencies | SDS I (1997–2000) |

SDS II (2000–2003) |

SDS III (2003–2006) |

SDS IV (2007–2009) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency | I | II | III | IV |

| Correctional Service Canada | I | II | III | IV |

| Office of the Auditor General of Canada | I | II | III | IV |

| Royal Canadian Mounted Police | I | II | III | IV |

Projects and environmental assessment requirements

The construction, operation, modification, and demolition or decommissioning of projects can pose a variety of environmental risks. Projects involve physical works such as bridges, pipelines, nuclear facilities, and marine terminals.

Environmental assessment is a process to ensure that environmental effects are identified and considered in decision making before a project proceeds.

Under the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012, federal environmental assessments are required for proposed projects that have been “designated,” either by regulation or by the Minister of the Environment and Climate Change Canada. The Regulations Designating Physical Activities identify the different project categories that may require an environmental assessment under the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012.

In addition, pursuant to section 67 of the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012, a federal environmental assessment may be required for other types of projects if they are located on federal lands (e.g., national parks, military bases, First Nations reserves).

Note

Projects that are undertaken in the northern territories or outside of Canada are subject to different requirements. See sections 2 and 68 of the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012.

Consult with the Internal Specialist—Environment and Sustainable Development (ESD) if you require more information.

Government and Crown corporation operations

As large enterprises in Canada, federal and territorial governments and Crown corporations have significant environmental footprints. The activities listed below, when performed by governments or Crown corporations, may have an impact on the environment—natural resources, energy, and water are consumed, emissions are released, waste is generated, and hazardous substances need to be managed:

- purchasing goods and services;

- managing buildings, facilities, and infrastructure (energy consumption, greenhouse gas emissions, water usage, waste water discharged, solid waste produced);

- managing laboratories and hazardous substances (solvents and other toxic substances);

- constructing, renovating, and demolishing buildings and infrastructure (asbestos, lead paint, and polychlorinated biphenyl present in older buildings);

- operating vehicle fleets;

- managing land (including managing ecological values on federal land, such as wetlands and endangered species);

- managing contaminated sites;

- handling fuel (storage tanks above ground and underground); and

- operating various equipment.

Under Goal 2 of the FSDS 2016–2019, the Government of Canada commits to leading by example by making its operation low-carbon. The government has established targets and milestones related to this goal:

Medium-term target

- Reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from federal government buildings and fleets by 40 percent below 2005 levels by 2030, with an aspiration to achieve it by 2025.

Short-term targets

- Be an early adopter of building standards to be established through the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change for all new government buildings and leases, where applicable.

- Establish a complete and public inventory of federal GHG emissions and energy use.

- Encourage departments to take action to innovate sustainable workplace practices.

- Review procurement practices to align with green objectives.

The Office of Greening Government Operations (OGGO) was created within Public Services and Procurement Canada in 2005. The OGGO works with federal government institutions to reduce the footprint of government operations. Its mandate is to accelerate the greening of the government’s operations by working closely with other federal departments, particularly the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat and Environment and Climate Change Canada.

Contaminated sites

Over 23,000 federal contaminated sites have been identified across the country. Various policies, guidelines, and funding programs are in place to support departments and agencies as they assess, remediate, or manage these sites. They are listed in the Treasury Board’s Federal Contaminated Sites Inventory.

Teams should also consult Appendix 4 for information on hazards associated with the built/indoor environment.

Funding or other financial arrangements or support

Federal or territorial entities can indirectly cause environmental effects by providing others with funding, loans, or other forms of financial assistance. The activities or initiatives that benefit from these arrangements may have environmental consequences.

Furthermore, when conducting audits of funding agreements, the OAG should consider environmental impacts. With respect to a recipient under any funding agreement, audit teams may ask the following questions:

- Has money been spent with due regard for economy and efficiency?

- Has money been spent with due regard for the effects on the environment in the context of sustainable development?Footnote 5

Considering the environment during the development of policy, plan, and program proposals: the Cabinet Directive on the Environmental Assessment of Policy, Plan and Program Proposals

To make informed decisions that support sustainable development, decision makers at all levels of government must have relevant information on environmental, economic, and social factors. This is particularly important for ministers of federal departments, whose decisions on government policies, plans, and programs can have important implications for Canada’s economy, society, and environment. It is also important for stakeholders to see that the government has considered factors in all three areas when making its decisions.

Integrating environmental considerations in the decision-making process for policies, plans, and programs is the subject of a federal Cabinet directive. According to the Cabinet Directive on the Environmental Assessment of Policy, Plan and Program Proposals and related guidelines, a strategic environmental assessment (SEA) should be performed for a policy, plan, or program proposal when the following two conditions are met:

- A proposal is submitted to an individual Minister or to Cabinet for approval (e.g., memoranda to Cabinet or Treasury Board submissions).

- The implementation of the proposal may result in important environmental effects, either positive or negative.

To determine whether an SEA must be performed, a preliminary environmental assessment (scan) must be conducted for every proposal.

In the first FSDS, released in 2010, the government committed to applying SEAs more stringently.Footnote 6 Submissions to an individual Minister or to Cabinet, including Treasury Board, should discuss any SEAs and the outcomes of this analysis as an integral part of examining the options presented.

Reporting and transparency

The results of any completed SEAs are reported through departmental results reports and public statements. The Cabinet directive requires that federal departments and agencies publish a public statement for SEAs. According to the SEA guidelines, departments and agencies shall prepare a public statement of environmental effects when a detailed assessment of environmental effects has been conducted through an SEA in order to assure stakeholders and the public that environmental factors have been appropriately considered when decisions are made.

Public Statements of Strategic Environmental Assessments can be accessed on the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency website.

Environmental petitions from residents of Canada: individuals, groups, and other organizations

Under the provisions of the Auditor General Act, a resident of Canada can submit environmental petitions to the OAG. Federal departments and agencies are responsible for responding to these petitions within a set time frame. The OAG has received over 400 petitions since 1997.

They cover a wide range of environmental and sustainable development issues that are the responsibility of the federal government.

Most petitions and responses are provided in full in the OAG’s Petitions Catalogue. Petitions can be searched by petition number, by issue, or by federal institution.

If you locate a petition that is relevant to the subject matter of your audit and the full text is not available in the catalogue, please contact the Petitions team to request a copy.

Appendix 4—The Built Environment: Hazards to Human Health and Well-Being

Our built surroundings can play a significant role in health and safety and well-being. We spend the majority of our time each day in workplaces, homes, or other indoor settings. Examples of hazards associated with the built environment include materials such as asbestos, mould, or other toxic substances, such as lead in paint. Many of these hazards have an impact on indoor air quality. Other kinds of building hazards include emergencies such as fires and explosions and issues related to building condition and structural integrity. Reducing risk requires appropriate management, including adequate heating and ventilation systems, risk identification and risk assessment, periodic inspections, and regular maintenance, as well as hazard prevention and emergency preparedness and response.

The Directory of Federal Real Property lists real property holdings (buildings and land) of the federal government. It includes properties that are owned or leased. The directory can be searched by custodial department, agency, Crown corporation, and port authority. It provides information on building age and condition (critical, poor, fair, good, etc.). See the Directory of Federal Real Property on the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat website.

An overview of the following hazards is provided in this appendix:

- asbestos;

- mould;

- radon;

- risks related to fuel combustion for power generation or heating (such as carbon monoxide and other air pollutants, and fuel storage tanks);

- bacteriological hazards and other pathogens;

- safe drinking water;

- volatile organic compounds (VOCs);

- lead; and

- electrical and fire hazards.

Please note that this is not an exhaustive list. Some hazards that are not covered here include the heavy metal mercury (present in old thermostats, among other things) and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). Although they are banned in Canada, PCBs are still found in older transformers and other electrical equipment.

Asbestos: Asbestos was used for decades as insulation, roofing, and fire and sound proofing, as well as in ceiling tiles, floor tiles, paints, adhesives, and plastics. It was valued in many commercial applications because of its heat resistance and strength, insulating, and friction characteristics. Asbestos is a fibrous material that can get trapped in the lungs after inhalation. If inhaled, it can cause cancer and other diseases. Effects include fibrotic lung disease, lung cancer, pleural disorders, and a type of cancer called mesothelioma. Overall use of asbestos in Canada has declined dramatically since the mid-1970s. In December 2016, the Government of Canada committed to develop regulations that would “seek to prohibit all future activities respecting asbestos and asbestos-containing products, including the manufacture, use, sale, offer for sale, import and export.” The regulations to implement an asbestos ban are expected to be developed by 2018.

Mould: Mould is a common term referring to fungi that can grow inside buildings, often on or behind drywall and ceiling tiles. It thrives in damp conditions. Moulds can affect indoor air quality because the mould spores and fragments disperse into the air and are inhaled. Health Canada considers any indoor mould growth to be a significant health hazard, as it can increase the risk of allergy symptoms such as eye, nose, and throat irritation, wheezing, coughing, phlegm buildup, and asthma conditions. Studies have confirmed a significant association between damp conditions in homes and an increased risk of developing asthma.

Radon: Radon is a radioactive gas that is invisible and odourless. Radon gas is released from the natural breakdown of uranium in soil, rock, and water. It can enter all types of buildings and accumulate to high levels. Because of its radioactive properties, it can damage lung tissue and cause lung cancer over time. It has been identified as the second leading cause of lung cancer after smoking. A cross-Canada survey of radon concentrations in homes, conducted by Health Canada, found that 6.9 percent of Canadians are living in homes with radon levels above the current radon threshold of 200 becquerels per cubic metre. This study did not examine workplaces where people might also be at risk of long-term exposure to radon gas.

Risks related to fuel combustion for power generation or heating

- Carbon monoxide and other air pollutants: Carbon monoxide can result from the incomplete burning of wood, propane, natural gas, heating oil, coal, charcoal, gasoline, etc. It can cause harmful effects by reducing the delivery of oxygen to the heart, brain, and other tissues. At high concentrations, it can lead to death. It is reported that more than 50 people die each year from carbon monoxide poisoning in Canada. Some provinces, such as Ontario, now require the installation of carbon monoxide alarms in residential buildings. Heating by wood creates other risks, aside from carbon monoxide. There are increasing concerns about pollutants contained in wood smoke, such as fine particulate matter. Evidence is mounting about the adverse health effects of wood smoke on the lungs and cardiovascular system.

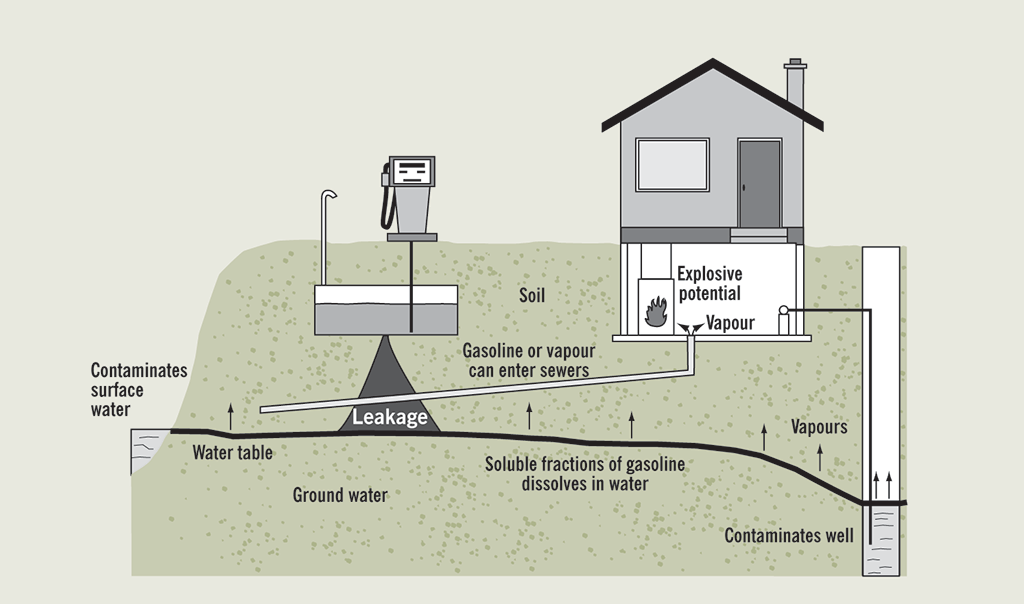

- Fuel storage tanks: Fuel storage tanks are commonplace in Canada. Spills and leaks from fuel tanks, fuel supply lines, and other related systems can contaminate surrounding soils, surface water and groundwater, and air; create combustion hazards; pose direct toxic risks to humans, plants, and animals; affect soil processes; and cause aesthetic problems, such as an objectionable odour and sheen. Left unmanaged, they can cause significant adverse effects. Contamination in soil or groundwater can migrate into indoor air in adjacent or overlying buildings. This is known as vapour intrusion. Where vapour intrusion occurs, there is the potential for impacts to indoor air quality and unacceptable chronic health risks to building occupants, as well as increased risk of fire or explosions. The elementary school in the First Nations community of Attawapiskat was closed due to health concerns after a large diesel spill seeped into the soil and groundwater around the school. Exhibit 11 illustrates how leaks from fuel storage tanks can cause various problems.

Exhibit 11: Leaking underground petroleum storage tanks can cause a number of problems

Source: Environment and Climate Change Canada

Exhibit 11—text version

This illustration shows a small house and a fuel pump, both of which are resting on the soil at the top of the illustration. The fuel pump is connected by a pipe to a petroleum storage tank installed underground beneath the pump. The tank is shown to be leaking into the soil. A pool of fuel is directly under the tank and a stream of fuel spans the whole length of the soil.

The illustration shows the problems that the leaking fuel can cause both below the storage tank and above it:

- The water table is under the fuel storage tank and could be contaminated by leaking fuel.

- Ground water flows below the water table and could be contaminated by leaking fuel, because soluble fractions of fuel dissolve in water.

- Contaminated ground water can flow out of the soil into surface water and contaminate surface water.

- The ground water can also flow into an underground well and contaminate the well.

The illustration shows that other problems can be caused by vapours from the soil and well water:

- Vapours from the fuel leak can make their way up into the soil.

- Vapours can enter the air from contaminated well water.

The illustration also shows that problems can be caused in and below the house:

- Below the house is a basement containing a furnace and a water pump. The water pump is connected by a pipe to the contaminated well water and can bring contaminated water into the house.

- Between the furnace and the water pump is a floor drain that is connected to a sewage pipe. The sewage pipe goes down for a short length underneath the basement floor then turns and passes through the leaked fuel. Vapours from the sewage pipe can enter sewers.

- Vapours can also come from the basement floor drain. These vapours have the potential to explode, if they come into contact with the heat from the furnace.

The source of this illustration is Environment and Climate Change Canada.

Bacteriological hazards and other pathogens: Exposure to bacteria and other pathogens can cause illness, including food-borne illnesses. Building premises need to be maintained in a clean and sanitary condition to avoid transmission of bacteria and other pathogens or contaminants, especially in areas where food is prepared and consumed. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency has developed a Guide to Food Safety (2010).

Safe drinking water: Drinking water needs to be free of both disease-causing organisms and chemical concentrations that have been shown to cause health problems. It should also have minimal taste and odour, making it aesthetically acceptable for drinking. The Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality-Summary Table establish safe levels for microbiological contaminants such as bacteria (e.g., E. coli), protozoa, and viruses, as well as chemicals and heavy metals like lead and arsenic. The guidelines are developed by the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Committee on Drinking Water. Ensuring a safe supply of drinking water involves management from source to tap—this means ensuring a safe, available source of water, protecting it from contamination, using effectiveness treatment where necessary, and preventing water quality deterioration in the distribution system. Employers under federal jurisdiction must provide potable water that meets the guidelines. The federal government updated its Guidance for Providing Safe Drinking Water in Areas of Federal Jurisdiction-Version 2 in 2013. At a minimum, water should be analyzed on a regular basis to confirm that it meets the Canadian guidelines and other requirements.

Volatile organic compounds: These are a large group of chemicals that evaporate at room temperature. They are contained in a variety of products, including carpets, adhesives, composite wood products, paints, solvents, upholstery fabrics, varnishes, and vinyl flooring, all of which off-gas or release VOCs into indoor air. Studies have shown indoor levels of VOCs to be two to five times higher than the levels outdoors. Some common examples of VOCs include acetone, benzene, formaldehyde, ethylene glycol, toluene, and xylene. Some individual VOCs have been identified as being carcinogenic or neurotoxic. Short-term or acute symptoms to high levels of VOCs include eye, nose, and throat irritation, headaches, nausea, dizziness, and exacerbation of asthma. Chronic health effects could include increased risk of cancer, liver damage, kidney damage, and central nervous system damage. Health Canada has developed indoor air quality guidelines for some VOCs, such as formaldehyde, toluene, and benzene.

Lead: Lead can be found in homes through lead-based paints, in contaminated soil and dust, and in drinking water (due to lead plumbing and piping) (see section on safe drinking water, above). Findings of elevated levels of lead residues in household dust in older buildings in a Health Canada study raise concerns about human exposure. Lower levels of lead can cause adverse health effects on the central nervous system, kidneys, and blood cells. The effects on children and fetuses are more severe, as this can affect physical and mental development. Children may also be at risk of higher exposures than adults through lead dust and by putting lead-contaminated objects into their mouths.

Electrical and fire hazards: Fire hazards in workplaces or other building settings are common. They include the presence of flammable liquids and vapours, accumulation of waste and combustible materials, objects that generate heat, faulty electrical equipment, smoking, and overloading power sockets. Fire risks can be minimized through regular inspections and appropriate building design with fire exits, fire safety equipment, and emergency preparedness and response programs and procedures.

Health Canada has produced a variety of guidance and study documents on health and the environment.

Appendix 5—Canada’s International Commitments on the Environment and Sustainable Development

Canada is a party to more than 130 international agreements that address environmental and sustainable development issues. These include bilateral agreements and regional or multilateral treaties. Obligations assumed through these legally binding agreements must be met domestically, and the federal government is responsible for matters under federal jurisdiction. Canada’s international commitments can serve as a useful source of audit criteria.

Some international instruments that Canada has adopted are not legally binding, as formal treaties are. However, these instruments should be consulted and may serve as a source of audit criteria. Examples include declarations and action plans under the auspices of the Arctic Council or the United Nations Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030.

Canada’s international commitments cover a diverse array of topics, such as

- the Arctic;

- fisheries resources;

- shipping;

- air quality, including ozone-depleting substances;

- greenhouse gases and climate change;

- biodiversity;

- nuclear safety;

- water quality;

- disasters/crises;

- food safety;

- hazardous pollutants and substances; and

- movement of hazardous waste.

To identify agreements that apply to Canada, you can perform searches using the following online resources:

- International Environmental Agreements Database Project, hosted by the University of Oregon; and

Note: Information is listed for specific countries and by subject matter. Searches can be performed using specific keywords or topics. In most cases, the text of the agreement is also provided. - Environmental Treaties and Resources Indicators (ENTRI) is an online resource that allows you to identify by country parties or by topic. Treaty texts can also be accessed using keyword searches. ENTRI is a project of the Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and Columbia University’s Center for International Earth Science Information Network.

See the Government of Canada’s website on its commitment to support the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.