2016 Spring Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development Report 1—Federal Support for Sustainable Municipal Infrastructure

2016 Spring Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development Report 1—Federal Support for Sustainable Municipal Infrastructure

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- List of Recommendations

- Exhibits:

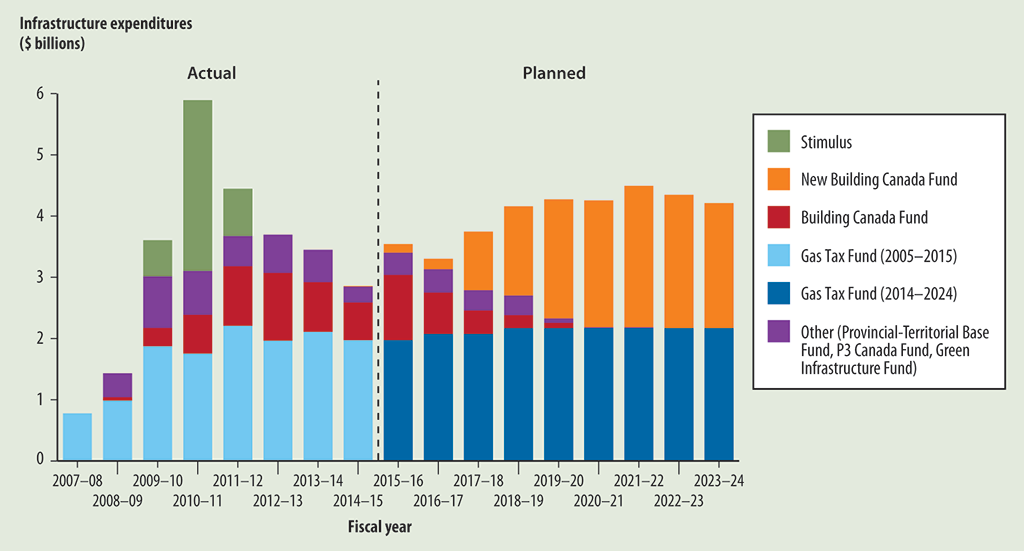

- 1.1—The mix of federal infrastructure programs has changed over the past decade and is projected to change in future years

- 1.2—The Green Municipal Fund has supported initiatives in several categories

- 1.3—Federal programs have provided funding for many types of municipal infrastructure

- 1.4—New federal wastewater regulations will place heavy demands on available infrastructure funding

Introduction

Background

1.1 Over the past century, Canadians have increasingly chosen to live and work in towns and cities. Statistics Canada has estimated that Canada’s six largest urban areas account for about half of all national economic activity. As urban areas grow and evolve, they face enormous challenges—from providing housing, to moving people and goods efficiently, to adapting to climate change. As a result, the economic, social, and environmental sustainability of Canadian communities strongly influences how the country as a whole meets the needs of future generations.

1.2 Under the Constitution, the provinces have the legal responsibility for municipalities. However, the federal government affects the sustainability of municipalities in all regions, through its policies; spending programs; regulations, such as energy-efficiency requirements; management of federal property, such as contaminated sites; and research in areas such as housing design. One of the most important ways is through federal funding for municipal infrastructure.

1.3 Infrastructure Canada. Established in 2002 and currently operating on the basis of an order-in-council, Infrastructure Canada is the main department responsible for federal efforts to enhance Canada’s infrastructure, with expenditures of over $3.6 billion planned for the 2015–16 fiscal year (Exhibit 1.1). It is the lead federal department for programs under the Building Canada plan and the New Building Canada Plan, and works with provinces, territories, municipalities, the private sector, and non-profit organizations to deliver its programs. The Gas Tax Fund is the single largest program the Department is managing, at about $2 billion per year.

Exhibit 1.1—The mix of federal infrastructure programs has changed over the past decade and is projected to change in future years

Source: Data from Infrastructure Canada and PPP Canada

Exhibit 1.1—text version

This bar chart shows actual and planned federal infrastructure expenditures by fiscal year for a 17-year period from 2007–08 to 2023–24. Federal infrastructure programs include six types of programs. They are

- stimulus;

- the New Building Canada Fund;

- the Building Canada Fund;

- the first round of the Gas Tax Fund, from 2005 to 2015;

- the second round of the Gas Tax Fund, from 2014 to 2024; and

- other programs (the Provincial-Territorial Base Fund, the P3 Canada Fund, and the Green Infrastructure Fund).

The left side of the chart shows actual expenditures for the 2007–08 to 2014–15 fiscal years, as follows:

- 2007–08: $778 million total (Gas Tax Fund)

- 2008–09: $1.4 billion total, comprising $56 million (Building Canada Fund), $986 million (Gas Tax Fund), and $391 million (other)

- 2009–10: $3.6 billion total, comprising $590 million (stimulus), $298 million (Building Canada Fund), $1.8 billion (Gas Tax Fund), and $843 million (other)

- 2010–11: $5.9 billion total, comprising $2.8 billion (stimulus), $633 million (Building Canada Fund), $1.8 billion (Gas Tax Fund), and $716 million (other)

- 2011–12: $4.4 billion total, comprising $771 million (stimulus), $974 million (Building Canada Fund), $2.2 billion (Gas Tax Fund), and $494 million (other)

- 2012–13: $3.7 billion total, comprising $1.1 billion (Building Canada Fund), $2.0 billion (Gas Tax Fund), and $627 million (other)

- 2013–14: $3.4 billion total, comprising $813 million (Building Canada Fund), $2.1 billion (Gas Tax Fund), and $529 million (other)

- 2014–15: $2.9 billion total, comprising $11 million (New Building Canada Fund), $614 million (Building Canada Fund), $2.0 billion (Gas Tax Fund), and $260 million (other)

The right side of the chart shows planned expenditures for the 2015–16 to 2023–24 fiscal years, as follows:

- 2015–16: $3.5 billion total, comprising $142 million (New Building Canada Fund), $1.1 billion (Building Canada Fund), $2.0 billion (Gas Tax Fund), and $361 million (other)

- 2016–17: $3.3 billion total, comprising $170 million (New Building Canada Fund), $676 million (Building Canada Fund), $2.1 billion (Gas Tax Fund), and $384 million (other)

- 2017–18: $3.7 billion total, comprising $958 million (New Building Canada Fund), $383 million (Building Canada Fund), $2.1 billion (Gas Tax Fund), and $332 million (other)

- 2018–19: $4.2 billion total, comprising $1.5 billion (New Building Canada Fund), $211 (Building Canada Fund), $2.2 billion (Gas Tax Fund), and $320 million (other)

- 2019–20: $4.3 billion total, comprising $1.9 billion (New Building Canada Fund), $84 million (Building Canada Fund), $2.2 billion (Gas Tax Fund), and $73 million (other)

- 2020–21: $4.3 billion total, comprising $2.1 billion (New Building Canada Fund), $2.2 billion (Gas Tax Fund), and $12 million (other)

- 2021–22: $4.5 billion total, comprising $2.3 billion (New Building Canada Fund), $2.2 billion (Gas Tax Fund), and $12 million (other)

- 2022–23: $4.3 billion total, comprising $2.2 billion (New Building Canada Fund) and $2.2 billion (Gas Tax Fund)

- 2023–24: $4.2 billion total, comprising $2.0 billion (New Building Canada Fund) and $2.2 billion (Gas Tax Fund)

1.4 Federation of Canadian Municipalities. Established in 1901, the Federation is a non-governmental organization whose membership includes Canada’s largest cities, small urban and rural communities, and 20 provincial and territorial municipal associations. In the early 2000s, the federal government provided the Federation with endowments totalling $500 million, which became known as the Green Municipal Fund. The Federation also received $50 million to disburse for plans, studies, and tests. The Federation is responsible for managing the Fund in accordance with the funding agreement with the federal government. Environment and Climate Change Canada and Natural Resources Canada help oversee the Fund on behalf of the federal government.

Focus of the audit

1.5 This audit focused on federal infrastructure programs intended to improve community environmental sustainability. We assessed whether the objectives of the Gas Tax Fund and the Green Municipal Fund were being achieved. We also examined whether Infrastructure Canada, working in collaboration with others, adequately coordinated the key federal programs under its responsibility. We selected those programs that funded municipal infrastructure and that were intended, among other objectives, to improve the environmental performance and sustainability of Canadian communities.

1.6 This audit is important because the programs examined are the main ways in which the federal government directly contributes to the environmental sustainability of Canadian communities, and because the programs are substantial investments. As the programs are expected to continue or to be expanded and new ones may be launched, this audit provides an opportunity to identify lessons for the future.

1.7 We did not look at the management of federal lands or federal assets, or at First Nations infrastructure. We did not audit the provinces, territories, or municipalities.

1.8 Our audit work in the Federation of Canadian Municipalities was limited to those activities, processes, and functions used to administer the Green Municipal Fund. We did not audit the overall management of the Federation or its sections or functions not involved in administering the Fund.

1.9 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Gas Tax Fund

1.10 Overall, we found that although the Gas Tax Fund has provided predictable funding to municipalities, Infrastructure Canada could not adequately demonstrate that the Fund has resulted in cleaner air, cleaner water, and reduced emissions of greenhouse gases. Infrastructure Canada did not implement the performance measurement strategy that it would have needed to determine whether the Fund was meeting its objectives, and to report on results to Parliament and the Canadian public. We also found that the Department did not consistently manage key accountability and reporting requirements. This makes it difficult for the Department to report back to Parliament about whether the funds have been managed appropriately and used for their intended purposes.

1.11 This finding is important because, starting in 2005, Infrastructure Canada paid out $13 billion in the first round of the Gas Tax Fund and currently provides about $2 billion each year. However, the Department is unable to provide Parliament with a clear description of the results obtained through a decade of funding. Canadians do not know what results have been achieved for the money spent, and with continuing funding, it is unclear what results they can expect in the future.

1.12 The Gas Tax Fund was established in 2005 and has had two major rounds of funding agreements. The first round of agreements covered 2005 to 2015. The original objective was to provide reliable, predictable funding in support of environmentally sustainable municipal infrastructure that contributes to cleaner air, cleaner water, and reduced greenhouse gas emissions. The second round of agreements was renewed one year early and set the terms and conditions of the Fund from 2014 to 2024. The objectives for these later agreements are a clean environment, increased productivity and economic growth, and strong cities and communities.

1.13 Signatories to the agreements include provinces, territories, associations that represent municipalities in Ontario and British Columbia, and the City of Toronto. Fund allocations were based on the number of people in each jurisdiction, with minimum amounts set for Prince Edward Island and each of the three territories. The signatories receive federal funds twice a year, in advance of the costs being incurred, and then they transfer funds to their municipalities to address local infrastructure priorities.

1.14 The 2007 federal budget extended the funding for the first round to 2014 for a cumulative investment of $13 billion. The 2011 and 2013 federal budgets established a set amount for the Gas Tax Fund of $2 billion per year, indexed at 2 percent per year, payable in $100 million increments, starting in the 2016–17 fiscal year.

1.15 Under the Fund, municipalities are responsible for making infrastructure investment decisions that respect the eligible investment categories determined by the federal government. Provinces and territories are responsible for administering the program and for reporting on outcomes achieved within their jurisdictions. At the federal level, Infrastructure Canada is responsible for ensuring that the program’s terms and conditions are met, that there is effective accountability and reporting, and that the program is on track to achieve its intended results.

1.16 Infrastructure Canada holds signatories to account for the use of funds, through audited annual expenditure reports; for results, through outcomes reports; and for fund management, through evaluations. (The first-round agreement with the Province of Quebec did not require the Province to submit outcomes reports to Infrastructure Canada.) Almost all of the signatories (12 of 15) must submit expenditure reports by 30 September of each year for the money spent in the previous fiscal year. The rest are due by 30 November or 31 December. This expenditure report is a key accountability and reporting requirement for assessing signatories’ continued eligibility for funding, and for ensuring that funds are being spent appropriately.

1.17 The projects funded by the Gas Tax Fund include a wide range of initiatives. Infrastructure Canada has reported that roads and bridges have been the most common projects, accounting for roughly one third of the total by both number and value. Examples of other projects include upgrading drinking water systems in Lévis, Quebec; building an organic-waste processing facility in Guelph, Ontario; and purchasing fuel-efficient buses in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Five of Canada’s largest cities—Vancouver, Calgary, Edmonton, Toronto, and Ottawa—have dedicated most or all of their funding to public transit.

Infrastructure Canada could not demonstrate that the Gas Tax Fund achieved the intended environmental benefits

1.18 We found that Infrastructure Canada did not have a final set of performance indicators, specific performance targets or expectations, or timelines to measure whether the Gas Tax Fund was meeting its objectives. We found that Infrastructure Canada did not adequately report on the outcomes of the Fund to Parliament and the Canadian public. The Department reported on the money spent on the Fund, but was not able to report on the results achieved.

1.19 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

- setting objectives,

- measuring performance,

- reporting on results, and

- promoting community sustainability planning.

1.20 This finding matters because without the relevant performance information, Infrastructure Canada could not determine the extent to which its environmental objectives had been met and what results had been achieved for the money spent.

1.21 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 1.29.

1.22 What we examined. We examined the elements of the performance measurement and reporting framework that Infrastructure Canada put in place, the Gas Tax Fund agreements between the federal government and the signatories, and the reports that signatories submitted.

1.23 Setting objectives. The first round of Gas Tax Fund agreements was intended to achieve three environmental objectives: cleaner air, cleaner water, and reduced greenhouse gas emissions. The second round of agreements had broader objectives. We found that the objectives for neither round had been put in terms that were SMART, that is, specific, measurable, attainable, results-oriented, and time-related.

1.24 Measuring performance. Under the first round of the Gas Tax Fund agreements, the effects of the funding were supposed to be measured using indicators that were based on the Fund objectives and the funding categories. The program was designed so that each signatory would establish an oversight committee, including a representative from Infrastructure Canada, which would be responsible for performance indicators. These committees were established. We found, however, that for both rounds of agreements, Infrastructure Canada, working with the signatories, did not have a set of indicators that could be applied consistently to aggregate results nationally.

1.25 During the first round of the Fund, Infrastructure Canada was not able to measure performance against its three environmental objectives. It will be even more difficult for the second round of agreements because the objectives are broader, specific expected results are not clearly defined, and the list of eligible investment categories is longer. In some cases, Infrastructure Canada has not made the cause-effect link between the funding category (such as recreation facilities) and the overall program objectives. As long as the project is within an eligible category, the funds can be used for an infrastructure project regardless of its net effect, intended or unintended, on environmental performance.

1.26 For the first round of agreements, Infrastructure Canada proposed project-level indicators to consolidate results from across the country. We found that the recipients of the funds could use these proposed indicators to, at a minimum, report the amounts spent and the number of projects for each category. The recipients could use other possible indicators to measure outputs, such as the length of roads built or the volume of water that could be treated to meet safety standards. For the second round of agreements, the draft list of indicators has grown along with the number of eligible categories. As of November 2015, this draft list had not been finalized; as a result, information is not being collected and reported using consistent definitions. We noted that, without targets and baselines, Infrastructure Canada was not able to measure how far it had come and how far it would have to go to meet the Fund’s objectives.

Departmental performance reports—Individual department and agency accounts of results achieved against performance expectations. The reports cover the most recent fiscal year and are normally tabled in Parliament in the fall.

1.27 Reporting on results. Infrastructure Canada is responsible for reporting on Gas Tax Fund outcomes to Parliament and the Canadian public. In 2008, Infrastructure Canada prepared a report titled Gas Tax Fund: Results for Canadians intended for the public but never released it. In 2015, Infrastructure Canada officials reported that they were working on a consolidated outcomes report, but they have not been able to finalize it because of delayed outcomes reports from signatories. In its 2013–14 Departmental Performance Report, Infrastructure Canada reported only on the amount of money spent and the percentage of annual expenditure reports and outcomes reports that it received in the fiscal year. The report includes no information about the change in environmental quality resulting from the funds.

1.28 Promoting community sustainability planning. According to 11 of the 13 first-round Gas Tax Fund agreements, signatories were required to ensure the development of integrated community sustainability plans. These long-term plans, developed in consultation with community members, provide direction for the community to achieve its environmental, cultural, social, and economic sustainability objectives. Jurisdictions took individual approaches to meeting the requirements for these plans. For example, the Province of Nova Scotia included the requirement for these plans in its funding agreements with its 54 municipalities. We found that Infrastructure Canada did not systematically track or report on the preparation and use of integrated community sustainability plans, or take other steps to promote them.

1.29 Recommendation. Infrastructure Canada should work with the agreement signatories to develop an effective performance measurement strategy so that it has the information it needs to determine whether the objectives of the Gas Tax Fund have been achieved and to take corrective action when necessary. Infrastructure Canada should use this information to report on Gas Tax Fund outcomes to Parliament and the Canadian public.

The Department’s response. Agreed. The Gas Tax Fund provides municipalities with a stable, flexible, and predictable source of funding that helps them build and revitalize infrastructure. While projects funded through the Fund are contributing to national objectives, such as productivity and economic growth, a clean environment, and strong cities and communities, this is not the primary objective of the program. Furthermore, jurisdictional challenges make it difficult to harmonize reports on national results and program performance in a consistent fashion.

Infrastructure Canada will work with signatories to develop an appropriate and effective performance measurement strategy to measure the outcomes.

The Department will implement a more practical performance reporting strategy for the Fund and will move forward with the three specific and measurable outcomes below:

- provide municipalities with access to a predictable source of funding,

- invest in community infrastructure, and

- support and encourage long-term municipal planning and asset management.

The Department will work with signatories to collect the results of their next outcomes reports in 2018 in order to demonstrate program outcomes. It will use the performance information submitted by the provinces to report to Parliament and Canadians on the outcomes through the Departmental Performance Report.

Infrastructure Canada did not consistently manage key accountability and reporting requirements of the Gas Tax Fund

1.30 We found deficiencies in Infrastructure Canada’s procedures that aimed to ensure effective accountability and reporting for the Gas Tax Fund. We also found that in some, but not all, cases the Department delayed providing funds when signatories submitted annual expenditure reports late.

1.31 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

1.32 This finding matters because the Gas Tax Fund provides signatories with funding in advance of the costs being incurred, and because the funds do not have to be spent in the year they are received. If Infrastructure Canada does not have and use the checks needed to ensure that funds are managed appropriately, Parliament cannot be confident that funds are being used for their intended purposes.

1.33 We made no recommendations in this area of examination.

1.34 What we examined. We examined how Infrastructure Canada managed the accountability requirements associated with 35 of the 57 possible second payments to agreement signatories from October 2012 to November 2015. Under the first round of agreements, these payments were to be issued only after Infrastructure Canada received the annual expenditure reports from the signatories. Under the second round of funding, the Department sends letters with the amounts and dates of payments to those signatories that are in compliance with the agreements. We examined how the Department tracked and responded to cases in which the required reports were late. We also examined how the Department managed the accountability requirements for the outcomes reports.

1.35 Managing annual reporting requirements. We found that Infrastructure Canada has faced issues with delayed reporting by signatories for at least the past two years. For example, the Department’s records indicated that, as of 30 November 2015, 5 of 13 signatories had met the deadline for submission of annual reports. Two more reports were not due until 31 December 2015.

1.36 For 25 of the 35 payments we considered, we found deficiencies and inconsistencies in how Infrastructure Canada monitored reporting by signatories and held them to account for their use of the Gas Tax Fund. In 3 of these cases, the Department issued payments before receiving the annual expenditure report. In other similar situations under both rounds, the Department did take action when reports were late, by withholding payment or by delaying issuance of the next year’s funding letter, thereby affecting future payments.

1.37 In the other 22 cases, we found weaknesses in how Infrastructure Canada reviewed the reports and approved payments. We found 7 cases in which officials did not complete their analyses of the expenditure reports before recommending that payments be made to the signatories, and a further 15 cases in which the approvals were not clearly documented before payments were recommended. We noted that in some cases Department officials planned to complete their review afterwards. We also noted improvements in how the Department monitored and approved expenditure reports during the course of our audit, and expect these improvements to continue.

1.38 Managing outcomes reporting requirements. Under the funding agreements, most signatories were also supposed to produce and make public periodic summaries of the outcomes achieved in their jurisdictions by using the Gas Tax Fund. For the first round of agreements, the outcomes reports were first due in 2009 and periodically thereafter. These reports were intended to document results against the objectives of cleaner air, cleaner water, and reduced greenhouse gas emissions. Outcomes reports expected in 2012 from two signatories were still outstanding as of November 2015. We noted that Infrastructure Canada had no means to compel signatories to comply with this requirement.

Green Municipal Fund

1.39 Overall, we found that the Federation of Canadian Municipalities was managing the Green Municipal Fund to support innovative municipal projects across Canada. The Federation was also demonstrating a good practice in tracking and reporting the environmental benefits of the projects it has funded. However, the Federation had not set out a clear description of what results it was trying to achieve in terms of how its investments would influence other municipal projects. Furthermore, mainly because of prevailing economic conditions, the balance in the Fund was at risk of falling below the specified minimum level, thereby putting the achievement of its objectives at risk.

1.40 This finding is important because the Green Municipal Fund targets innovative projects intended to improve the environmental performance of Canadian communities—an approach that complements other federal funding programs. To be as effective as possible, the Fund needs clear objectives and performance expectations for all of its activities, and long-term threats to its financial sustainability need to be addressed.

1.41 In 2000, the Federation of Canadian Municipalities received grants from Environment Canada (renamed Environment and Climate Change Canada in November 2015) and Natural Resources Canada to create the Green Municipal Enabling Fund and the Green Municipal Investment Fund. In 2005, these funds were combined to form the Green Municipal Fund, with a total endowment of $500 million. The terms and conditions for managing this endowment were set out in a funding agreement. The Federation received an additional grant of $50 million, to be disbursed in accordance with the funding agreement, to support activities such as plans, studies, and tests.

1.42 According to the funding agreement, the purpose of the Fund is to “assist municipal governments in Canada to lever investments in municipal environmental projects and provide grants for feasibility studies, assessments, sustainable community plans and field tests, and grants, loans and/or loan guarantees to eligible recipients for project implementation.” The agreement also notes that the Government of Canada and the Federation “desire to enhance the quality of life of Canadians by improving air, water and soil quality, and protecting the climate.” Since the Fund was created, the Federation has periodically revised its approach to achieving this purpose.

Brownfield—An abandoned, vacant, derelict, or underutilized commercial or industrial property where past actions have led to actual or perceived contamination and where there is an active potential for redevelopment.

1.43 The Fund supports projects in five main categories: brownfields, energy, transportation, waste, and water. Several criteria, including the use of innovative approaches, guide project selection. According to the 2014–15 annual report, about $56 million was allocated in that fiscal year, and a total of $756 million in funding has been approved and 891 projects have been completed since this initiative began. As one example, the Fund provided a loan of about $1.5 million and a grant of about $300,000 for a community centre in Île-des-Chênes, Manitoba, that uses a district geothermal heating system to reduce energy consumption.

1.44 The Green Municipal Fund Council advises the Federation on the management of the Fund. The Council comprises representatives from the federal government (Environment and Climate Change Canada, Natural Resources Canada, and Infrastructure Canada), municipal officials, and external members representing the public, private, academic, and environmental sectors.

The Federation reported the environmental benefits of projects it funded, but did not clearly define how it expected its investments to lever other municipal projects

1.45 We found that the Federation of Canadian Municipalities funded projects to meet the expectations for the types and locations of projects as set out in the funding agreement for the Green Municipal Fund. We also found that the Federation was measuring and reporting the environmental benefits of the projects it supported. We found, however, that the Federation had not set out specific objectives for what it was trying to achieve by levering these projects for municipal innovation.

1.46 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

1.47 This finding matters because the Federation, its partners, and the Canadian public need clear objectives and performance expectations for the Green Municipal Fund to determine how successful it is in terms of its influence beyond the projects it funds directly. The requirement that recipients track the actual environmental benefits of their projects is an innovative feature of the Fund. This is a good practice that could be applied to other infrastructure funding programs to quantify the results of projects and to promote systematic learning.

1.48 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 1.52.

1.49 What we examined. We examined planning documents and elements of the performance management and reporting system for the Green Municipal Fund. We also examined the procedures used by the Federation to obtain estimates of the environmental benefits of the capital projects it funds. These procedures included information management systems and quality controls.

1.50 Setting objectives and measuring progress. According to the funding agreement, one part of the purpose of the Fund is to provide grants and loans to implement municipal environmental projects. We found that the Federation had defined performance expectations and was meeting the requirements in the funding agreement for the types of projects it supported and for rural-urban (Exhibit 1.2) and regional balances. For example, about 20 percent of project funds went to small, rural, or remote communities—roughly proportional to Canada’s population distribution.

Exhibit 1.2—The Green Municipal Fund has supported initiatives in several categories

| Category of initiative | Number of applications receivedNote 1 | Number of initiatives approvedNote 2 | Total value of grants and loans approvedNote 3 (in $ millions) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capital projects | 577 | 188 | $680.3 |

|

Brownfields

|

46 | 13 | $39.8 |

|

Energy

|

255 | 91 | $320.3 |

|

Transportation

|

42 | 8 | $34.5 |

|

Waste

|

92 | 21 | $71.6 |

|

Water

|

133 | 49 | $175.0 |

|

Multi-sector

|

9 | 6 | $39.1 |

| Plans, feasibility studies, and field tests | 1,476 | 900 | $75.3 |

| Total | 2,053 | 1,088 | $755.7 |

|

Urban

|

1,452 | 782 | $596.0 |

|

Rural

|

601 | 306 | $159.7 |

Entries are from the inception of the Fund in 2000 up to and including the 2014–15 fiscal year.

Source: Federation of Canadian Municipalities

1.51 Another part of the purpose of the Fund is to lever investments in municipal projects. We found that the Federation had not yet set out a clear description of what results it was trying to achieve regarding how its investments and other products and services would influence other municipal projects and other kinds of innovation. This includes how the Federation targeted and delivered knowledge services, such as informing municipalities about innovative projects through webinars or conferences. The Federation had some information on how frequently pilot projects or studies supported by the Fund were “converted” to full capital projects, but this was only one way its projects affected the adoption of innovative practices by municipalities.

1.52 Recommendation. The Federation of Canadian Municipalities, in consultation with the Green Municipal Fund Council (which includes Natural Resources Canada and Environment and Climate Change Canada as members), should develop specific objectives, performance targets, and indicators for levering its investments in municipal environmental projects.

The Federation’s response. Agreed. The Federation of Canadian Municipalities will develop specific objectives, performance targets, and indicators to better reflect the various leveraging activities that are delivered through the Green Municipal Fund. As the Federation is currently implementing its final year of a three-year plan for the Fund, over the course of the 2016–17 fiscal year, the Federation will take the opportunity to engage the Green Municipal Fund Council on establishing these leveraging objectives and targets. The results of this work with the Council will form part of the Fund’s next three-year plan.

1.53 Measuring and reporting environmental benefits. The contracts for capital projects included a hold-back provision requiring recipients to report on the environmental benefits after at least 12 consecutive months of operation—typically one year after project completion. This provision allowed the Federation to collect and analyze data on the actual performance of the projects and to compare these observations with the predicted effects. This practice contrasted with the requirements for the projects funded by Infrastructure Canada under other programs.

1.54 We found that the Federation was tracking and reporting these environmental benefits. For example, in its annual reports, the Federation has reported on the number of energy projects it funded, the expected reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, and the actual reductions.

The long-term financial sustainability of the Fund was at risk

1.55 We found that the Green Municipal Fund’s long-term financial sustainability was at risk, mainly because of current economic conditions and the terms of the funding agreement with Environment and Climate Change Canada and Natural Resources Canada. The balance in the Fund was at risk of falling below the specified minimum level of $500 million, thereby also putting the achievement of its objectives at risk. We found that the Federation had taken action to address these concerns, but has projected that its actions would likely be insufficient to reverse the expected reduction in the Fund balance.

1.56 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

1.57 This finding matters because a decline in the Fund balance would reduce the total value of the projects that could be funded each year. The same factors are also shrinking the resources available for Fund operations and for building capacity in municipalities. If fewer municipalities are able to use the Fund to design and implement innovative projects, the Fund might not be able to achieve its overall purpose.

1.58 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 1.62.

1.59 What we examined. We examined the financial analysis conducted by the Federation on the future status of the Green Municipal Fund, the actions taken by the Federation, and its analysis of the effects of those actions on the projected sustainability of the Fund. Fund sustainability was determined by the terms and conditions of the funding agreement, which required that the Fund provide an annual minimum amount of loans and grants, and contribute annually to a reserve for non-performing loans, while maintaining the Fund balance at a minimum of $500 million. The interest revenues (investments and loans) would have to be enough to cover the minimum funding requirements and the operating expenses of the Fund.

1.60 Assessing Fund sustainability. We found that in 2012 the Federation projected that the fund balance would decline and drop below the required minimum balance within the next decade. Limitations on the kinds of investments the Fund managers can make, as well as other terms and conditions of the 2005 funding agreement, contributed to this situation. For example, $150 million of the Fund was set aside to assist communities with the remediation and redevelopment of brownfields, yet this was an area where the Federation had received relatively few applications. Other key factors were the change in rates of return and the effect of inflation. For example, inflation had reduced the relative value of the Fund since it was created.

1.61 Taking action to improve Fund sustainability. We found that the Federation had taken action to address some of the factors under its control. For example, the Federation has introduced higher rates on its loans to non-municipal borrowers. The Federation estimated that these actions would delay the decline, but would likely not be enough to reverse it.

1.62 Recommendation. Natural Resources Canada, Environment and Climate Change Canada, and the Federation of Canadian Municipalities should review the terms and conditions in the funding agreement for the Green Municipal Fund and revise them as needed to address the financial sustainability concerns about the Fund. These parties should consider including a requirement for a regular review of the agreement so that it continues to support Fund objectives.

The departments’ response. Agreed. In reviewing Budget 2016 commitments and the process for deploying newly announced funding measures, Natural Resources Canada and Environment and Climate Change Canada will work with the Federation of Canadian Municipalities on options to support the long-term sustainability of the Green Municipal Fund—for example, the modification of the Fund investment guidelines and regular review of its terms and conditions.

The Federation’s response. Agreed. The Federation of Canadian Municipalities has undertaken considerable work over the past several years in analyzing and implementing measures to manage the Green Municipal Fund’s sustainability challenges while also proactively educating and highlighting these concerns to the Green Municipal Fund Council. This analysis can be used as the basis for the initial discussions with Environment and Climate Change Canada and Natural Resources Canada. The Federation will work collaboratively with both federal departments to ensure that any necessary revisions to the funding agreement are made as soon as reasonably possible to address the Fund’s sustainability concerns. Further consultations with these federal departments are necessary on the specific approach and timing for implementing this recommendation.

Coordination of federal funding programs

1.63 Overall, we found that Infrastructure Canada was working in collaboration with others, but was missing some elements necessary for coordinating the key programs under its responsibility that were intended to improve the environmental performance and sustainability of Canadian municipalities. The Department was not adequately considering environmental risks, such as climate change, in how it made funding decisions, nor did current programs actively encourage the use of innovative approaches to mitigate those risks. The Department did not have sufficient information available to it on the state of infrastructure, funding needs, and sustainability challenges to support strategic and coordinated funding decisions. Infrastructure Canada had developed a long-term plan for infrastructure funding. However, the resulting New Building Canada Plan only addressed some federal roles and responsibilities, without outlining federal infrastructure priorities, or providing clear objectives and ways to measure and report on results.

1.64 This finding is important because inadequate consideration of environmental risks means that projects might not be designed to minimize their environmental impacts, or, for instance, to withstand future severe weather events (see 2016 Spring Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Report 2—Mitigating the Impacts of Severe Weather). Inadequate predictability and clarity of federal programs may affect the ability of communities to identify which funds are most appropriate to their needs and to obtain resources in a timely way. Inadequate information limits the ability of the federal government to design its programs to meet the needs of communities. As a result, federal funds could be less effective in improving the environmental performance and sustainability of municipalities.

1.65 The federal government has made substantial investments in environmentally sustainable municipal infrastructure since 2000, using a mix of different programs, including the Gas Tax Fund, the Green Municipal Fund, and a fund dedicated to green infrastructure projects. Many of these programs have provided funding to the same types of infrastructure projects (Exhibit 1.3). Effective coordination in the design and delivery of these programs can help ensure that federal funds achieve value for Canadians, do not work at cross-purposes, and meet their commitments to improving environmental quality.

Exhibit 1.3—Federal programs have provided funding for many types of municipal infrastructure

| Type of infrastructure | Gas Tax Fund 2005 | Gas Tax Fund 2014 | Building Canada Fund | New Building Canada Fund (National Infrastructure Component) | New Building Canada Fund (Provincial-Territorial Infrastructure Component) | Green Infrastructure Fund | Infrastructure Stimulus Fund | P3 Canada FundNote 1 | Green Municipal FundNote 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brownfield remediation or redevelopment |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Carbon transmission and storage |

|

||||||||

| Capacity building |

|

|

|

||||||

| Collaborative projects |

|

||||||||

| Connectivity and broadband |

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Community services |

|

||||||||

| Culture |

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Drinking water |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Disaster mitigation |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Energy |

|

|

|||||||

| Green energy |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Highways and major roads |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Innovation |

|

||||||||

| Intelligent Transportation Systems |

|

||||||||

| Local and regional airports |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Local roads and bridges |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Northern (territories only) |

|

||||||||

| Parks and trails |

|

||||||||

| Ports |

|

||||||||

| Public transit |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Rail |

|

||||||||

| Recreation |

|

|

|||||||

| Short-line rail |

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Short-sea shipping |

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Solid waste management |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Sport |

|

|

|||||||

| Tourism |

|

|

|

||||||

| Wastewater |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.66 Infrastructure Canada is the lead federal department responsible for infrastructure policy development and program delivery. The Department relies on partnerships with several parties to deliver the programs under its responsibility: provinces, territories, municipalities, private and non-profit organizations, and other federal departments and agencies. It faces significant challenges in delivering funding programs across the country. These include

- establishing and maintaining effective working relationships with all jurisdictions;

- adjusting its program delivery to the diverse economic conditions, priorities, and capacities of other levels of government; and

- coordinating with the other federal entities involved in the delivery of infrastructure programs.

1.67 The Department needs effective mechanisms for strategic planning, communication, and cooperation to ensure that its programs can deliver their intended results. Furthermore, because the responsibilities for environmental performance are shared among levels of government, roles and responsibilities must be clear so that environmental risks can be appropriately identified and managed.

Infrastructure Canada did not adequately identify or manage environmental risks for the projects it funds

1.68 We found that Infrastructure Canada did not adequately identify or manage the environmental risks associated with the projects it funded. The Department expected proponents of major projects to supply information on environmental risks, including climate change risks, but did not include this information in its project risk analyses. We also found that Infrastructure Canada had completed the first step in the strategic environmental assessments for four of the programs we examined, but did not carry out a detailed assessment of the environmental effects. Moreover, the Department also indicated it had no mandate to encourage new approaches that would reduce the environmental effects.

1.69 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

- considering climate change risks,

- assessing environmental effects, and

- promoting innovation to address environmental risks.

1.70 This finding matters because climate change is a growing risk to municipal infrastructure. If this risk is not considered during project design, proponents may face high and unexpected future costs. Environmental assessment is an essential tool to ensuring that environmental effects of projects are considered early in the design stage, so that negative effects can be mitigated. Innovation will be critical to addressing the future needs of Canadian municipalities, especially given the pressure on available financial resources and emerging risks, such as climate change.

1.71 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 1.100.

1.72 What we examined. We examined the procedures that Infrastructure Canada used to consider environmental risks, such as climate change, during its project reviews. We also examined how the Department used strategic and project-level environmental assessments to mitigate possible negative environmental effects. We considered the strategic assessments done for the Building Canada Fund, the New Building Canada Fund, the Green Infrastructure Fund, and the two rounds of the Gas Tax Fund. We also looked at the role of the Department in promoting innovation to address environmental risks.

1.73 Considering climate change risks. According to the 2011 Federal Adaptation Policy Framework, Infrastructure Canada is supposed to take action to ensure that it effectively integrates climate change considerations into its own programs, policies, and operations, and facilitates action by others.

1.74 Under the New Building Canada Fund, a suite of funding programs managed by Infrastructure Canada, we found that the Department expected proponents of major projects to supply information about relevant environmental risks, such as climate change. We found, however, that the Department did not require its officials to analyze climate change risks systematically. Instead, departmental risk analysis focused on risks that might impede or delay successful completion of the project, such as whether a federal environmental assessment would be required, whether financing had been secured, or the complexity of the project. The Department informed us that it had not been given the authority to consider climate change risks.

1.75 Assessing environmental effects. At the federal level, environmental effects are assessed in two ways. Strategic environmental assessments are used to identify the possible effects of proposed policies, plans, or programs. Then for specific project proposals, project environmental assessments are used to identify the potential negative effects, along with mitigating actions, in more detail.

1.76 In terms of strategic environmental assessments, we found that, as required, Infrastructure Canada completed the first step in the assessment (the preliminary scan) for four of the five programs we examined. The Department was not able to provide a strategic assessment for the fifth program, the establishment of the Gas Tax Fund in 2005. We found that these four preliminary scans contained the information and analysis necessary to deciding whether the programs could lead to important environmental effects, and hence whether a detailed assessment of the effects would be required. We found, however, that the decisions not to proceed to detailed assessments were not documented or, in our view, were not consistent with the guidelines for such decisions. (We reported related findings in the 2015 Fall Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Report 3—Departmental Progress in Implementing Sustainable Development Strategies.)

1.77 A detailed strategic environmental assessment could describe the measures to reduce or eliminate adverse effects. In addition, a strategic environmental assessment could examine the risks that projects intended to achieve one program objective could be working at cross-purposes to other objectives of the same program, or to the objectives of another program. So, funding to expand road networks might lead to more air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. We found that Infrastructure Canada did not undertake a detailed assessment of this type of risk or the implications for its environmental program objectives.

1.78 In terms of project environmental assessments, Infrastructure Canada has stated that since the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012 came into force, no projects that it has funded have required a federal environmental assessment as a result of its funding. This means that any environmental assessment of funded projects would have been conducted only by another federal entity or by another level of government, and that the same project being carried out in two different provinces could be held to two different standards.

1.79 Promoting innovation to address environmental risks. Infrastructure Canada informed us that it had not been given a mandate to encourage innovative infrastructure projects through its project selection. This gap translates to a risk that older technologies might not be replaced by using “green” infrastructure or by using other alternative approaches that could achieve greater net environmental benefits. Innovative projects supported by the Green Municipal Fund could complement those funded by Infrastructure Canada. In our view, the federal responsibilities for innovation in this area need to be sorted out.

1.80 Given Infrastructure Canada’s mandate, the current legislative context, and the role of the Department in funding projects proposed, designed, and managed by others, it has no obligations to encourage project managers to assess project alternatives fully, to consider environmental risks early in the design stage, or to encourage innovative solutions. The Department would need to work with others to ensure that environmental risks, including the risks due to climate change, are adequately considered and managed.

Infrastructure Canada was missing some critical information and tools for strategic coordination

1.81 We found that Infrastructure Canada, working in collaboration with others, was missing some information and tools necessary for strategic coordination when addressing the long-term infrastructure challenges for municipalities. The Department did not have sufficient information available to it on the state of infrastructure, funding needs, and sustainability challenges to support strategic and coordinated funding decisions. Infrastructure Canada was contributing to better asset management by municipalities, but had not clearly defined what role it would play. We found that Infrastructure Canada followed an appropriate consultation process for developing a long-term infrastructure plan. However, the resulting New Building Canada Plan only addressed some federal roles and responsibilities. The Department had some good practices for communicating with others, but did not have the tools to report on results across its programs.

1.82 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

- assessing needs for municipal infrastructure funding,

- promoting asset management,

- communicating with partners and funding recipients,

- developing a long-term infrastructure plan, and

- measuring and reporting results.

1.83 This finding matters because most of the infrastructure in Canadian communities is owned by provincial, territorial, or municipal governments, which are also responsible for its long-term management. All levels of government, therefore, need good information about the condition of infrastructure and about federal programs, objectives, and roles. The lack of this information could cause federal funds to be allocated where they would be less effective, lead to potential recipients experiencing delays and inefficiencies in meeting their funding needs, or result in Parliament and Canadians not receiving reliable information about the net effects of the funding programs.

1.84 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 1.91 and 1.100.

1.85 What we examined. We examined the availability of information about the needs for municipal infrastructure funding and the role of Infrastructure Canada in obtaining this information. We examined documents and conducted interviews related to coordination among federal infrastructure programs, specifically those under the New Building Canada Fund envelope, focusing on how Infrastructure Canada communicated and coordinated with other parties. We also examined the federal roles in supporting municipal infrastructure management and the documentation of the consultation process for a long-term infrastructure plan. We also looked at how measuring and reporting results was coordinated across programs.

1.86 Assessing needs for municipal infrastructure funding. We found that Infrastructure Canada did not have sufficient information available to it on the state of infrastructure, funding needs, and sustainability challenges to support strategic and coordinated decisions. The decisions could include, for example, selecting how much to allocate to public transit programs in large cities as opposed to other infrastructure needs. Also missing was a consolidated analysis of future risks and needs that could support decisions about future funding requirements.

1.87 As an example of the importance of matching funding needs to available sources, we looked at wastewater management. Municipalities have become responsible for meeting the requirements of the 2012 federal Wastewater Systems Effluent Regulations, in many cases relying on funding from their respective provinces or territories, as well as the federal government (Exhibit 1.4).

Exhibit 1.4—New federal wastewater regulations will place heavy demands on available infrastructure funding

City of St. John’s wastewater treatment plant

Photo: City of St. John’s

The challenge for municipalities

The 2012 federal Wastewater Systems Effluent Regulations will require an upgrade of approximately 850 wastewater systems across Canada by 2040. Environment Canada (renamed Environment and Climate Change Canada in November 2015) has estimated that the necessary infrastructure would cost $6 billion. Other estimates are even higher. The Federation of Canadian Municipalities concluded that existing federal funding programs, such as the Gas Tax Fund and the New Building Canada Fund (which includes wastewater as an eligible category), will not be enough to help cover the costs for municipalities to implement the regulations.

The example of Newfoundland and Labrador

In 2012, Environment Canada estimated that the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador had 45 high-risk plants that needed upgrades by 2020 and one medium-risk plant that needed an upgrade by 2030 to meet the regulations; the final numbers are not expected to be this high. For example, the City of St. John’s new wastewater treatment facility, opened in 2009, will need to be upgraded to provide secondary treatment by 2020. The City has indicated that meeting this deadline is impossible; it has yet to secure the funding necessary for the upgrade (estimated at $200 million). Some smaller communities in the province have conflicting infrastructure priorities. For example, about 200 currently have boil-water advisories. These communities might have neither the funds to build secondary wastewater treatment facilities nor the capacity to operate and maintain them.

1.88 Several studies have attempted to document the status of Canada’s core public infrastructure (comprising roads, bridges, drinking water facilities, wastewater facilities, and public transit) and the resulting funding needs for municipalities. These studies have identified substantial information gaps. For example, the 2012 Canadian Infrastructure Report Card obtained reliable information from only 123 municipalities and found that almost half of these municipalities reported having no data on the condition of their buried infrastructure, such as water-distribution pipes. Such information on the condition of assets and the risks of failures is valuable when making decisions such as the recent diversion of untreated wastewater into the St. Lawrence River by the City of Montréal. (The City carried out this diversion, with the necessary authorizations, over four days to permit repairs and preventive maintenance to one of the main wastewater pipes.)

1.89 We found that Infrastructure Canada did not conduct its own research on municipal infrastructure funding needs. The Department has used some Statistics Canada data to estimate the age of Canada’s infrastructure, but the estimates did not include the current condition or performance of the infrastructure, or estimates of future needs.

1.90 In 2009, the Department had a memorandum of understanding with Statistics Canada to collect information on the state of infrastructure. The work progressed as far as a draft survey of core public infrastructure. However, Infrastructure Canada did not give final approval to proceed with that survey.

1.91 Recommendation. To support strategic and coordinated funding decisions, Infrastructure Canada should work with Statistics Canada and other parties, as necessary, to build a source of standardized, reliable, and regularly updated information on the inventory and condition of Canada’s core public infrastructure.

The Department’s response. Agreed. In line with Budget 2016, Infrastructure Canada is committed to working with Statistics Canada as well as other stakeholders to improve infrastructure-related data. This will provide a baseline of information on the state and performance of core public infrastructure assets for all levels of government.

In 2016, the Department will work with Statistics Canada to develop an action plan to meet the Budget 2016 commitment, with implementation to follow in 2017.

1.92 Promoting asset management. About 95 percent of Canada’s public infrastructure assets are owned by provincial, territorial, or municipal governments, which are responsible for managing them. Asset management has been defined as an integrated, lifecycle approach to managing infrastructure assets to maximize benefits, manage risk, and provide satisfactory levels of service to the public in a sustainable and environmentally responsible manner. International standards for managing infrastructure assets, such as ISO 55000, provide a basis for consistent practices and could improve the quality and consistency of information available on municipal infrastructure. For example, the City of Hamilton has catalogued all of its public assets, assigned values to them, and estimated the risks of infrastructure failures, such as water main breaks. This means, for instance, that it has the information to discuss with its citizens what level of road maintenance will be provided, where, and at what cost.

1.93 The second round of Gas Tax Fund agreements require most provinces and territories to promote better planning and to support their municipalities in adopting asset management plans, but the agreements’ requirements and deadlines vary. We found that Infrastructure Canada had facilitated discussions on implementing such plans, but had not provided specific guidance or played a leadership role. For example, Infrastructure Canada could have promoted systematic consideration of environmental risks in asset management plans. Some municipal and provincial representatives told us that they would welcome a clearer federal role regarding asset planning.

1.94 Communicating with partners and funding recipients. Treasury Board policy requires good coordination among federal programs that contribute to similar objectives or serve the same recipients. When we looked at the program objectives and funding categories, we noted that there was a range of target recipients and a mix of project categories for the different programs; this would require effective coordination and communication (Exhibit 1.3). We found, however, that some applicants experienced significant delays and difficulties when applying to the New Building Canada Fund—for example, related to unclear deadlines and the requirement to consider public-private financing.

1.95 During program implementation, Infrastructure Canada negotiates with its provincial, territorial, and municipal partners funding agreements that outline roles and responsibilities. We found that Infrastructure Canada also coordinated with other governments through informal communication with identified contacts and through committees that oversee the funding agreements. Provincial and municipal officials told us that, once the applications and project reviews were complete and the funding agreement was in place, they were generally satisfied with their coordination with Infrastructure Canada.

1.96 Developing a long-term infrastructure plan. At a strategic level, Budget 2011 stated that the federal government would work with provinces, territories, the Federation of Canadian Municipalities, and other stakeholders to develop a long-term plan for public infrastructure that would extend beyond the expiry of the Building Canada plan in the 2013–14 fiscal year. Infrastructure Canada led this consultation for the federal government. We noted that the consultation process was well documented, including the input received and the lessons learned.

1.97 The New Building Canada Plan is the result of this consultation. We found that the Plan focuses only on the roles and responsibilities of some federal entities; it does not address the roles of other federal entities that have been involved in delivering infrastructure programs, such as Transport Canada, Public Safety Canada, or the regional development agencies. Furthermore, it does not provide long-term federal priorities for infrastructure that are linked to well-defined objectives and a performance management framework. For example, under the Plan, projects are proposed, reviewed, and funded only on a case-by-case basis, without a clear connection to a strategic federal vision. In addition, the Plan does not describe agreed-upon roles and responsibilities of the players across the country, including the provinces, territories, municipalities, and municipal associations.

1.98 We also found that the federal government did not link its infrastructure programs into the Federal Sustainable Development Strategy, an interdepartmental initiative for sustainable development. As a result, the federal government missed an opportunity to coordinate its action on cleaner air, cleaner water, and reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.

1.99 Measuring and reporting results. We found that Infrastructure Canada was working on project-level performance indicators for the New Building Canada Fund programs and was trying to standardize them across the programs. We found, however, that there was no coordinated roll-up of this performance information or reporting on results within or across federal programs—for example, to describe the overall outcomes of the New Building Canada Plan. This means that the Department could not assess and report on the combined effect of the projects and programs over time to Parliament and Canadians.

1.100 Recommendation. Infrastructure Canada, in collaboration with its federal, provincial, territorial, and municipal partners, should

- clarify the federal roles and responsibilities in relation to those of the other players making decisions related to municipal infrastructure funding, including identifying and managing environmental risks, such as those linked to climate change;

- address their needs for better information about municipal funding requirements, including nationally consistent asset inventories;

- provide support to municipalities in their adoption of good practices for asset management;

- clarify the federal roles in promoting the use of innovative approaches to municipal infrastructure projects that contribute to environmental and financial sustainability; and

- provide a long-term vision outlining federal infrastructure priorities, with clear objectives, performance measures, and accountability.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Infrastructure Canada will continue to work closely with provinces, territories, and municipalities while implementing their infrastructure projects. The Department does not have a regulatory role, and project proponents remain responsible for the planning, prioritization, design, financing, and operation of their infrastructure assets. The Department will continue in its role as a convener on infrastructure issues.

With regard to the consideration of environmental risks, identification and consideration of environmental risks remain the responsibility of the asset manager. In the context of current programs, the federal role is to confirm that applicable risks, including environmental risks, have been considered by the asset owner and that it has taken measures to address those risks. This will be reflected more clearly in the context of applicable program information for asset managers and project proponents to be developed, in respect of new programming, or revised, in respect of current programming, over the 2016–17 fiscal year.

Recognizing the need for improved data to support evidence-based decision making, in line with Budget 2016, Infrastructure Canada is committed to working with Statistics Canada as well as other stakeholders to improve infrastructure-related data. This will support better information on the state and performance of core public infrastructure assets for all levels of government. The Department will work with Statistics Canada to develop plans to meet the Budget 2016 commitment, with implementation to follow in 2017.

Infrastructure Canada will support municipalities’ capacity for improved asset management practices under existing programs as well as under programs that are currently being finalized. Budget 2016 announced $50 million in new funding for a new asset management fund. This fund is designed to support the development and implementation of municipal infrastructure asset management practices, and data collection on infrastructure assets to bolster greater evidence-based decision making for strategic investments at all levels of government. Support for asset management is also reflected under the newly announced Public Transit Infrastructure Fund and the Clean Water and Wastewater Fund. The implementation of these funds will begin in the 2016–17 fiscal year and take place over the following five years.

In addition, under the Gas Tax Fund, funding is already available for municipalities to improve their asset management planning. All signatories have committed to ensure progress on the state of asset management planning by municipalities and will report on progress in 2018.

Infrastructure Canada recognizes and supports the importance of innovation, particularly in the context of ensuring the environmental and financial sustainability of infrastructure. As identified in Budget 2016, Phase 2 of the federal government’s infrastructure plan signaled that the federal government will work over the next year with partners to examine new innovative financing mechanisms to increase the long-term affordability and sustainability of infrastructure in Canada. In this context, the Department will also continue to examine its own programming for opportunities that will maximize innovative mechanisms for program delivery and project funding. It will also aim to better support the use of state-of-the-art infrastructure technology to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of existing assets. This examination will take place as part of the Phase 2 engagement process for the long-term infrastructure investment plan announced in Budget 2016, which will take place in the 2016–17 fiscal year. The outcomes of this examination will form part of Phase 2, which the government will announce in the next year.

Also as part of the engagement on Phase 2, beginning in the spring of 2016, the Government of Canada will work with its provincial, territorial, municipal, and Indigenous partners, as well as other stakeholders, to determine longer-term infrastructure priorities. Continuing to build on the government’s role as funding partner and convener of infrastructure issues, the long-term plan will include a clear identification of the federal role and responsibilities, as well as federal and mutually identified objectives, and outcomes. Phase 2 of the long-term plan will be introduced in 2017.

Conclusion

1.101 We concluded that Infrastructure Canada was not adequately managing the Gas Tax Fund to achieve the Fund’s environmental objectives, and that the Department was not adequately coordinating the key federal infrastructure programs under its responsibility that were intended to improve the environmental performance and sustainability of Canadian communities. We also concluded that the Federation of Canadian Municipalities was managing the Green Municipal Fund to achieve part of the Fund’s purpose, but how it was seeking to lever its investments in municipal environmental projects remained to be better defined.

1.102 Overall, we found that although billions of dollars have been allocated to programs with objectives to improve environmental sustainability, Canadians do not have a consolidated national picture of the extent to which these objectives have been achieved. We also found that Infrastructure Canada did not adequately consider environmental risks, such as climate change, in its program and project decisions.

1.103 Without a long-term federal vision that is based on reliable information about the condition of Canada’s infrastructure, and without clear objectives, priorities, and performance measures, Canadians will not know what results to expect from the billions spent on infrastructure through federal programs or how well those programs are working to make communities sustainable for future generations.

About the Audit

The Office of the Auditor General’s responsibility was to conduct an independent examination of federal support for municipal infrastructure intended to improve environmental performance, in order to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs.

All of the audit work in this report was conducted in accordance with the standards for assurance engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance. While the Office adopts these standards as the minimum requirement for our audits, we also draw upon the standards and practices of other disciplines.

As part of our regular audit process, we obtained management’s confirmation that the findings in this report are factually based.

Objective

The overall objective was to determine whether Infrastructure Canada and the Federation of Canadian Municipalities managed two key programs designed to support sustainable communities to achieve their objectives, and whether Infrastructure Canada adequately coordinated the set of programs.

Scope and approach

Our audit work focused on Infrastructure Canada’s management of the Gas Tax Fund and its coordination of some key federal programs that provide funding for municipal infrastructure. We also assessed the Federation of Canadian Municipalities’ management of the Green Municipal Fund. We also spoke to officials in Environment and Climate Change Canada and Natural Resources Canada, in view of their roles in overseeing the Green Municipal Fund.

We relied on interviews with officials from audited organizations and with stakeholders, such as the recipients of federal funds. We examined selected project files and databases used for tracking performance information. Entity officials provided details on key management processes. We spoke to municipal and provincial officials in several jurisdictions and conducted interviews and site visits in Calgary, Toronto, and St. John’s. For our work on the Gas Tax Fund, we also used an online survey distributed to all signatories of funding agreements to obtain their views on aspects of the management of the Fund.

To assess the procedures used by Infrastructure Canada to review the reports received from the signatories of the Gas Tax Fund agreements, we chose 35 of the second of the two annual payments made to the signatories from October 2012 to November 2015 and looked at the procedures leading up to the payments. Given that there were 15 signatories and that our testing covered four fiscal years, we expected that there would be 57 possible payments, considering that our testing occurred in November 2015, when three annual reports were not yet due. The payments were selected to focus on higher-risk items (for example, because of larger dollar amounts) and to include examples of payments to all jurisdictions.

Criteria

To determine whether Infrastructure Canada managed the Gas Tax Fund to achieve the Fund’s objectives, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Infrastructure Canada, working with others, is managing the Gas Tax Fund Transfer Payment Program in accordance with key federal policies and relevant agreements. |

|

|

Infrastructure Canada can demonstrate that the Gas Tax Fund Transfer Payment Program is meeting the Fund’s objectives. |

|

To determine whether the Federation of Canadian Municipalities, with the support of Environment and Climate Change Canada and Natural Resources Canada, could demonstrate that the Green Municipal Fund was meeting its objectives, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

The Federation of Canadian Municipalities, with the support of Environment and Climate Change Canada and Natural Resources Canada, can demonstrate that the Green Municipal Fund is meeting the Fund’s objectives. |

|

To determine whether Infrastructure Canada, working in collaboration with others, adequately coordinated the key federal programs under its responsibility that were intended to improve the environmental performance and sustainability of Canadian communities by funding municipal infrastructure, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Infrastructure Canada has adequate information for decision making on the infrastructure and financing needs of Canadian communities, and the sustainability challenges they face. |

|

|

Infrastructure Canada, working in collaboration with others, is ensuring that federal funding is adequately coordinated for municipal infrastructure to improve the environmental performance and the sustainability of Canadian communities. |

|

|

Infrastructure Canada, working in collaboration with others, is managing the key federal programs under its responsibility that support municipal infrastructure in a way that mitigates the environmental and financial sustainability risks. |

|

Management reviewed and accepted the suitability of the criteria used in the audit.

Period covered by the audit

The main emphasis of the audit was on the period between April 2010 and October 2015. Some questions required consideration of events and information related to the design and early implementation of the programs. For example, the agreements for the Green Municipal Fund and for the first round of the Gas Tax Fund were signed in 2005. To provide the most up-to-date information possible, we also included some information from after October 2015. Audit work for this report was completed on 11 March 2016.

Audit team

Principal: Kimberley Leach

Director: Peter Morrison

Arethea Curtis

Caron Mervitz

Melissa Miller

List of Recommendations

The following is a list of recommendations found in this report. The number in front of the recommendation indicates the paragraph where it appears in the report. The numbers in parentheses indicate the paragraphs where the topic is discussed.

Gas Tax Fund

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|