2020 Fall Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the Parliament of Canada Independent Auditor’s ReportReport 1—Follow-up Audit on the Transportation of Dangerous Goods

2020 Fall Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the Parliament of CanadaReport 1—Follow-up Audit on the Transportation of Dangerous Goods

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- List of Recommendations

- Exhibits:

- 1.1—Volume of all dangerous goods shipped by rail across Canada

- 1.2—Design flaws in Transport Canada’s risk-scoring system for violations understate risk levels

- 1.3—An emergency response assistance plan was granted multiple interim approvals over the past 20 years by Transport Canada

- 1.4—The Canada Energy Regulator did not adequately document its analysis of how a company met the pipeline approval condition about crossing bodies of water

- 1.5—Tracking compliance with pipeline approval conditions in the 36 cases we examined

Introduction

Background

A pipeline being prepared for underground installation

Photo: Canada Energy Regulator

1.1 Dangerous goods are solids, liquids, or gases that when spilled or released have the potential to harm the health of Canadians and other living organisms, property, or the environment. These goods play a key part in Canada’s economy and society. Dangerous goods are transported throughout Canada by rail, road, ship, air, and pipeline. Examples of dangerous goods are explosives, toxic gases, flammable liquids and solids, infectious substances, radioactive materials, and corrosive chemicals.

1.2 Dangerous goods also include the crude oil, petroleum products, natural gas liquids, and natural gas that move through the approximately 72,000 kilometres of federally regulated pipelines throughout Canada. According to the Canada Energy Regulator (formerly the National Energy Board), roughly $100 billion worth of energy products were shipped in these pipelines during each of the last few years.

1.3 Spills and releases of dangerous goods can happen with any mode of transportation. Therefore, these goods require special precautions to ensure their safe transportation. Both Transport Canada and the Canada Energy Regulator aim to prevent spills and releases of dangerous goods by monitoring and enforcing industry compliance with legislation and standards.

1.4 The Transportation of Dangerous Goods Act, 1992 and its regulations govern dangerous goods shipped by rail (Exhibit 1.1), road, ship, and air. Under the act and regulations, Transport Canada’s responsibilities include

- conducting inspections of facilities and sites that handle, offer for transport, transport, or import dangerous goods

- carrying out investigations and enforcement actions, where required, to ensure immediate compliance and promote future compliance

- approving emergency response assistance plans for companies regulated by the act

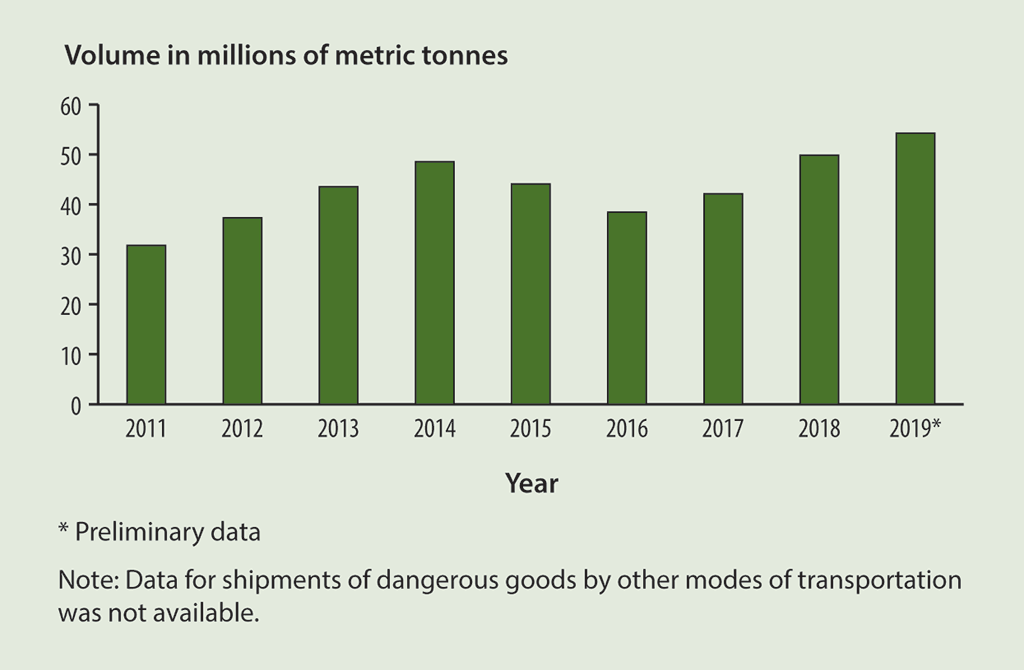

Exhibit 1.1—Volume of all dangerous goods shipped by rail across Canada

Source: Transport Canada’s Rail Traffic Database

Exhibit 1.1—text version

This graph shows the volume of all dangerous goods shipped by rail across Canada between 2011 and 2019:

- In 2011, 31.8 million metric tonnes were shipped.

- In 2012, 37.3 million metric tonnes were shipped.

- In 2013, 43.5 million metric tonnes were shipped.

- In 2014, 48.5 million metric tonnes were shipped.

- In 2015, 44.1 million metric tonnes were shipped.

- In 2016, 38.5 million metric tonnes were shipped.

- In 2017, 42.1 million metric tonnes were shipped.

- In 2018, 49.8 million metric tonnes were shipped.

- In 2019, 54.2 million metric tonnes were shipped. The data for 2019 is preliminary.

Note: Data for shipments of dangerous goods by other modes of transportation was not available.

Source: Transport Canada’s Rail Traffic Database

1.5 During our audit period, the National Energy Board became the Canada Energy Regulator. The regulator administers the Canadian Energy Regulator Act and its regulations, which replaced the National Energy Board Act. The act and its regulations apply to those pipelines that cross provincial, territorial, or national boundaries. The regulator’s oversight applies to the entire life cycle of a pipeline (and related infrastructure), including planning and application, construction, operation, and decommissioning and abandonment. The regulator performs activities to verify that companies comply with regulatory requirements and meet their pipeline approval conditions.

1.6 This audit follows up on selected recommendations from our 2011 and 2015 audit reports:

- 2011 December Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Chapter 1—Transportation of Dangerous Products

- 2015 Fall Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Report 2—Oversight of Federally Regulated Pipelines

1.7 In our 2011 audit, we found that Transport Canada

- had no national risk-based compliance inspection plan

- failed to consistently follow up to ensure that companies took corrective action on instances of non-compliance

- lacked clear roles and responsibilities for monitoring compliance with the act and regulations

- could not report on the rate of regulatory compliance because of the limits of the department’s performance measurement system

- did not grant final approval for nearly half of the emergency response assistance plans in place for regulated companies

1.8 In our 2015 audit, we found that the National Energy Board (former name of the Canada Energy Regulator)

- failed to adequately determine whether companies met pipeline approval conditions

- did not systematically verify that companies took corrective actions to return to compliance

- had inadequate information management systems to track and document company compliance and the board’s compliance oversight activities

1.9 In September 2015, Canada committed to the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. In 2017, the Office of the Auditor General of Canada committed to examining through our audit work how federal organizations are contributing to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. The matters examined in this audit relate to Goal 3: Good health and well-being. This goal has the associated target 3.9: “By 2030, substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water and soil pollution and contamination.”

1.10 Transport Canada’s sustainable development strategy states that the department’s action to contribute to this target and goal is to prevent environmental emergencies or mitigate their impact in communities.

Focus of the audit

1.11 This audit focused on the extent to which Transport Canada and the Canada Energy Regulator implemented recommendations from our 2011 and 2015 reports regarding these organizations’ compliance and enforcement responsibilities for the safe transportation of dangerous goods. This audit also focused on whether the organizations followed up with companies that had contravened regulations to ensure the companies returned to compliance, among other things.

1.12 This audit is important because accidents involving the transportation of dangerous goods can have tragic consequences, including loss of life and significant damage to property and the environment. For example, if released during transportation, chlorine used in purifying water supplies and anhydrous ammonia used in fertilizing crops could spread easily under certain conditions and pose a hazard to health.

1.13 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Overall message

1.14 Overall, we found that since our 2011 audit of the transportation of dangerous products, Transport Canada had made some improvements in the areas we followed up on, but we also found that there was still important work to be done. For example, we found that the department still had not followed up on some violations or granted final approval to many emergency response assistance plans. We also found that, although Transport Canada implemented our recommendation to develop a national risk-based system to prioritize its inspections, the underlying data was incomplete and outdated. Transport Canada has more progress to make to address the problems we identified in order to support the safe transportation of dangerous goods.

1.15 We also found that since our 2015 audit of the oversight of federally regulated pipelines, the Canada Energy Regulator had largely implemented the 3 recommendations that we followed up on. For example, it implemented an information management system to improve the tracking and documenting of its compliance oversight activities, and it improved its verification that regulated companies had taken corrective action to address non-compliance.

Transporting dangerous goods by rail, road, ship, and air

1.16 One of Transport Canada’s functions in its oversight of dangerous goods is conducting inspections of companies that handle, offer for transport, transport, or import these materials. According to the department, its Transportation of Dangerous Goods Program conducts more than 5,000 of these inspections every year, up from approximately 2,000 as we reported in 2011. The program’s spending also rose from $13.9 million in the 2011–12 fiscal year to $36.2 million in the 2018–19 fiscal year. During that same period, the program’s full-time-equivalent staff increased from 113 to 290.

1.17 Transportation of Dangerous Goods Program staff conduct inspections at rail, marine, road, and air facilities and buildings where dangerous goods are manufactured, stored, or received. These inspectors are responsible for monitoring companies’ compliance with legislation. For example, if there are violations in documentation, training, labelling, or the packaging and containers used to transport dangerous goods, inspectors can require companies to take corrective actions. Inspectors are also expected to follow up to ensure that companies return to compliance, and if not, inspectors may take other enforcement measures, such as issuing orders to detain goods.

1.18 Another of Transport Canada’s key oversight functions is reviewing emergency response assistance plans prepared by companies transporting dangerous goods to verify that the plans comply with the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Act, 1992 and its regulations. The act requires companies to have an approved emergency response assistance plan before handling, offering for transport, transporting, or importing certain quantities or concentrations of certain dangerous goods. These plans outline what is to be done to respond if dangerous goods that endanger, or could endanger, public safety are released while being handled or transported. These plans must demonstrate that specialized personnel and equipment are available in a timely manner to help first responders, such as firefighters.

Transport Canada still had shortcomings in its oversight of dangerous goods, despite having made some progress

1.19 We found that, despite having strengthened some policies, procedures, systems, and guidance, Transport Canada had not completed the work needed to address some of the problems identified in our 2011 audit. In particular, we found that the department did not always follow up on violations identified through inspections to ensure they had been addressed. In addition, the department had not finished its work to grant final approval of many companies’ plans to respond to emergencies. We also found that, although the department developed and implemented a national risk-based process to target inspections, this system was based on incomplete and outdated information. Furthermore, we found that the department did not have enough information to know whether certain facilities that manufacture, test, or repair containers for transporting dangerous goods in Canada were operating with valid certifications.

1.20 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

- Incomplete information for the risk-based planning of inspections

- Inadequate follow-up on violations

- Clear roles and responsibilities for compliance oversight

- Incomplete performance measurement

- Incomplete reviews of emergency response assistance plans

1.21 This finding matters because Transport Canada is responsible for verifying that companies respect the regulatory requirements for the safe transportation of dangerous goods.

1.22 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 1.27, 1.33, 1.34, 1.41, and 1.48.

Incomplete information for the risk-based planning of inspections

Dangerous goods transported by air may pose risks, such as lithium batteries that can overheat and catch fire.

Photo: depaz/Shutterstock.com

Marine port hubs are sites that can handle high volumes of dangerous goods. According to Transport Canada, inspections at these hubs are the most effective way to monitor compliance before dangerous goods enter the Canadian transportation network.

Photo: Office of the Auditor General of Canada

1.23 In 2011, we recommended that Transport Canada implement a national risk-based inspection plan. In this follow-up audit, we found that the department had done so. It developed an annual national oversight plan that included the priority sites, modes of transportation, and goods for inspection. For example, for the 2018–19 fiscal year, the plan’s key priorities focused on the air transportation of lithium batteries, recurring non-compliance in marine transportation, and the loading of crude oil from highway tanks to rail car tanks. The department implemented several tools in order to identify risks, including

- a policy on inspection prioritization, planning, and reporting

- a framework for prioritizing inspections

- an integrated risk management framework

1.24 However, we found that some problems affected the assessment of risks used to develop the national inspection plan. We found that Transport Canada did not have a complete and accurate picture of the companies it was regulating (see paragraph 1.38). We made this same finding in 2011. According to Transport Canada, inaccurate data on regulated companies, such as duplicate sites, makes it difficult for the department to analyze trends using inspection data and to assess risk to identify the highest-priority sites for inspection.

1.25 We also found that information on many of the sites in the national risk-based inspection plan was out of date. For example, 29% of the sites included in the national inspection plan for the 2018–19 fiscal year turned out to be closed, had moved, were duplicates, or may no longer have been handling, offering for transport, transporting, or importing dangerous goods. Therefore, the inspection process was not as efficient as it could have been because inspectors spent time and resources determining whether these sites even existed or still handled dangerous goods, rather than detecting possible violations at active sites.

1.26 In addition, we found that there were some problems with the database used to assess the risks of violations identified during an inspection and to inform risk-based planning. For example, for each violation found under the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Act, 1992 and its regulations, a score is assigned that indicates the severity of the violation. We found, however, that this scoring system had 2 design flaws that understated risk levels:

- We found that for 18 violations under the act and regulations, the system had erroneously assigned a score of 0, thereby understating the level of risk associated with these violations. One such violation is a failure to report a release of dangerous goods. We found that, overall, a score of 0 had been incorrectly assigned in 295 (6%) of the 5,189 violations that the department had found in the 2018–19 fiscal year.

- An inspector may also identify the same violation at a site multiple times. However, because the violations relate to the same section of the act or regulations, the system allows the inspector to score only 1 of these incidents of non-compliance, thereby understating the risk score of the violations as well as the total number of violations. We observed this design flaw during a site visit (Exhibit 1.2).

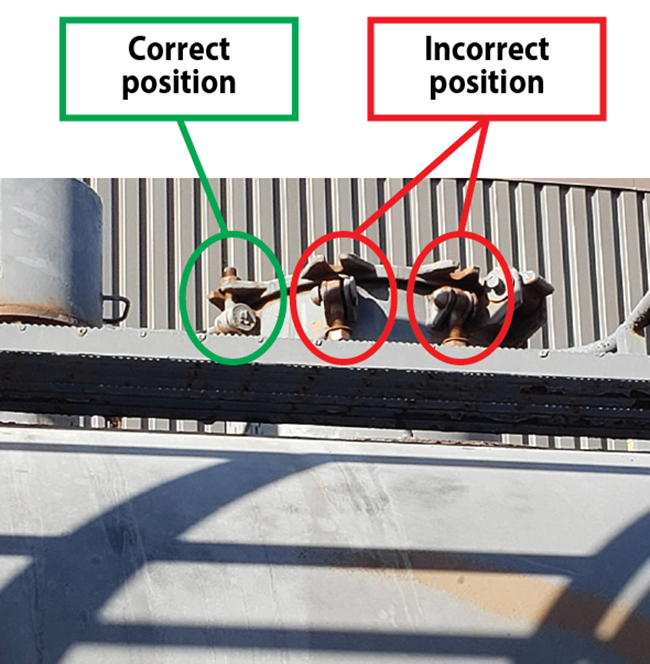

Exhibit 1.2—Design flaws in Transport Canada’s risk-scoring system for violations understate risk levels

A safety violation found on a rail car during an inspection

Photo: Office of the Auditor General of Canada

We observed one of the problems with Transport Canada’s risk-scoring system when we accompanied a departmental inspector at a facility where dangerous goods were being offloaded from railway tank cars. On 3 rail cars containing corrosives or flammable and combustible liquids, the inspector found a safety violation of the same section of the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Regulations:

- On 1 rail car, the hand brake was not fully applied during unloading.

- On a second rail car, valves were not tightened after unloading was completed.

- On a third rail car, bolts on a cover were not in the correct position to properly secure it (see photo).

When the inspector added each of these 3 violations to the department’s database, the database recorded a risk score for only 1 of these violations, not all 3, because they fell under the same section of the regulations.

1.27 Recommendation. Transport Canada should improve and update its tools and database to have more complete and accurate information on regulated companies and their compliance status and to better inform risk-based planning.

The department’s response. Agreed. Transport Canada will undertake the following activities:

- The policy approach to creating a registration requirement for transporters of dangerous goods was finalized in summer 2019. The department is developing legislative amendments to the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Act, 1992 and supporting regulations to implement the approach. Concurrently, the Client Identification Database will be developed to allow the public to register with Transport Canada. Full implementation is expected in late 2022.

- By fall 2021, the department will modernize the policy and procedures for the Inspection Prioritization Tool to identify gaps and strengthen business requirements in the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Program’s systems (for example, the Inspection Information System and “Transportation of Dangerous GoodsTDG-Core” central database) for risk scoring of regulated sites and facilities, violations, and inspection follow-ups.

- The department will confirm that data quality control processes are in place to support the effective application of tools, guidance materials, and appropriate risk scoring for individual and multiple violations. Managers will ensure that this undertaking, as well as associated inspector training, is complete by fall 2020.

- The department will further accelerate the work of the Data Quality Working Group to minimize to the extent possible, by fall 2020, the number of closed transportation of dangerous goods and means of containment sites currently in the transportation of dangerous goods databases.

Inadequate follow-up on violations

1.28 In 2011, we found that in the files we examined that identified non-compliance, Transport Canada did not always verify that companies returned to compliance. We also found that the department lacked guidance for inspectors on how to conduct and document inspections and follow-up activities. In this follow-up audit, we found that the department developed or improved its manuals, user guides, and standards to provide such guidance for inspectors—for example, it updated or created

- an inspector’s manual

- a user guide for its Inspection Information System database

- a standard for inspectors on following up on violations

1.29 In this follow-up audit, to determine whether this improved guidance resulted in better oversight, we examined a sample of 60 violations identified in the 2018–19 fiscal year. Our sample included violations related to containers, safety labels, documentation, and training. Examples of violations that the department identified through the inspections included

- the failure to prepare a shipping document for the dangerous goods being transported

- a safety label on a shipment that indicated the wrong dangerous good contained inside

- no evidence of adequate training for those handling, offering for transport, transporting, or importing dangerous goods

1.30 We found that in 18 (30%) of 60 violations, Transport Canada did not verify that companies took corrective actions to return to compliance. Among these cases, we found that the department

- had no evidence to determine whether violations had been resolved, and that it did not follow up with companies to obtain the required evidence

- did not conclude whether violations were resolved, despite companies having submitted the required evidence that they took corrective actions to address the violations

- concluded that companies had returned to compliance without having received any documentation to support that conclusion

1.31 We also examined 10 cases in which violations required that a follow-up inspection be conducted within 90 days. We found that in 4 of these cases, no follow-up had been conducted. Following up to ensure that companies return to compliance when the department identifies violations is an important aspect of oversight. Proper containment, labelling, training, and documentation are required to protect the safety of the public, those who handle and transport dangerous goods, and first responders to an accident. Such practices are also aimed at preventing spills and releases of dangerous goods into the environment.

1.32 During the course of the audit, we also found problems with the department’s verification of means of containment facilities—that is, those facilities that manufacture, test, or repair containers for the transportation of dangerous goods in Canada. Such facilities must obtain certification from Transport Canada that they meet safety design standards under federal legislation to protect the public and the environment. We found that of the 2,025 facilities registered with the department, 207 (10%) had expired certificates as of December 2019. The average length of time that these certificates had been expired was more than 2.5 years. We found that, while the department had procedures in place to notify companies that their certification was going to expire or had expired, the department had not used these procedures consistently. We also found that the department did not have enough information to know whether any of these facilities continued operating without certification. According to the department’s own assessment of risks, facilities operating with expired certification, or with no certification at all, pose a risk that the frequency and severity of incidents may increase.

1.33 Recommendation. Transport Canada should systematically track and document its verification that companies have returned to compliance after violations are found.

The department’s response. Agreed. Transport Canada will strengthen the application of, and the supporting training on, oversight procedures for follow-up activities conducted by inspectors after they detect non-compliance by regulated entities. Management will ensure that inspectors are aware of updated procedures and are able to apply appropriate quality controls. This is to be completed by spring 2021.

1.34 Recommendation. Transport Canada should ensure that means of containment facilities with expired certificates are not conducting the activities for which the certificates were issued.

The department’s response. Agreed. Transport Canada will strengthen its standard operating procedures to ensure that

- a letter is sent informing a registrant when the registration is about to expire

- following expiration, a letter is sent indicating the registration has expired and the registrant may no longer conduct such work

- in cases where Transport Canada cannot verify whether a registrant has ceased to perform the functions following the expiry of the registration, a registrant will be the subject of an onsite verification under the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Program’s National Oversight Plan

This work will be complete by spring 2021.

Clear roles and responsibilities for compliance oversight

1.35 In 2011, we found that the responsibilities within Transport Canada for monitoring compliance with legislation were unclear. We recommended that the department clarify its internal roles and responsibilities for monitoring compliance. In this follow-up audit, we found that the roles and responsibilities for conducting inspections of dangerous goods had been clarified. Since 2016, inspectors with the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Program have had authority to carry out inspections of dangerous goods at all marine and air sites.

1.36 At the time of our follow-up audit, officials in the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Program told us that they were continuing to work with both the Marine Safety and Security and the Civil Aviation directorates to determine whether formal agreements between the program and the directorates would still be required to coordinate oversight activities for the transportation of dangerous goods.

Incomplete performance measurement

1.37 In 2011, we found that Transport Canada needed to improve its methods for monitoring whether companies transporting dangerous goods were complying with regulations. A key element in the performance measurement of regulatory compliance is for the department to have a comprehensive picture of the nature and extent of compliance monitoring being conducted, which it did not have in 2011. In this follow-up audit, we found that, although the department improved its methods to measure company compliance resulting from its own inspections, it still did not have a comprehensive picture of compliance monitoring in Canada.

Provinces and territories share responsibility with Transport Canada for monitoring compliance for the transportation of dangerous goods by road.

Photo: ilmarinfoto/Shutterstock.com

1.38 We found that Transport Canada still did not know the extent of national compliance monitoring for the following reasons:

- The department’s database of companies it regulates was missing thousands of potential sites. In 2014 and 2016, the department identified more than 2,000 possible new sites to inspect, but these sites had yet to be confirmed and entered into its database. In addition, the list of sites in the database went back to the early 1990s, and it contained sites from other departmental databases. This meant that a large percentage of sites in the database either had no inspection history or had profile information that was considered out of date or incomplete. The database also contained duplicate sites, which, according to the department, made any analysis of trends using inspection data very difficult.

- The department did not routinely collect data from provinces and territories, which share responsibility with Transport Canada for monitoring compliance for the transportation of dangerous goods by road. The department has agreements with all provinces and one territory to share data related to the transportation of dangerous goods, including on compliance monitoring.

1.39 We also looked at performance measurement by examining whether Transport Canada’s activities were making progress toward Goal 3 of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. Specifically, target 3.9 is to substantially reduce, by 2030, the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water, and soil pollution and contamination. The department committed that its Transportation of Dangerous Goods Program would work to meet this target through its actions on emergency prevention, preparedness, and response.

1.40 In 2017, the program established a target to decrease by 2% from the previous year the rate of reportable releases of dangerous goods. We noted that the program did not achieve its target in 2017 and 2018, when the rate from the previous year increased by 23% and 13%, respectively. We found that this was partly because, in December 2016, the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Regulations were amended to change the types of releases of dangerous goods to be reported. However, despite the change in reporting, the actual number of incidents involving releases of dangerous goods was still higher in 2018 than it was in 2016 and 2017. Given the short time elapsed since the legislative change and the creation of this target, the department was still determining how its activities will achieve its target.

1.41 Recommendation. Transport Canada should strengthen its processes for collecting data from its partners to better identify the national rate of regulatory compliance in the transportation of dangerous goods.

The department’s response. Agreed. Transport Canada will undertake the following activities:

- By spring 2022, as part of the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Transformation Road Map, the department will implement a data-driven oversight initiative that will include the implementation of the “TDG-Core” central database initiative (revamping of the Inspection Information System, creation of the Client Identification Database, and integration into the Inspection Information System of the Facilities and Design Register database of registered facilities). This initiative will be supported by a renewal of information sharing agreements with provinces, territories, and other appropriate government programs and agencies, such as the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission and Health Canada.

- By spring 2021, the department will also further accelerate the quality control activities being conducted by the Data Quality Working Group, with the objective of strengthening transportation of dangerous goods oversight systems and data relevant to transportation of dangerous goods regulatory responsibilities to assess and verify compliance of regulated entities under the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Act, 1992 and the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Regulations.

Incomplete reviews of emergency response assistance plans

1.42 Transport Canada requires an emergency response assistance plan for companies transporting or importing certain dangerous goods representing a high risk to public safety. In 2011, we found that Transport Canada gave only interim approvalDefinition i to 453 of the 926 (49%) emergency response assistance plans submitted by regulated companies. As a result, dangerous goods had been shipped for years without the department having completed a detailed verification of these plans. We also found that the department’s guidance for staff to review and approve these plans was inadequate.

1.43 In this follow-up audit, we found that the department had clarified requirements for the review and approval of emergency response assistance plans. It had also put in place processes to help staff conduct and document their reviews of companies’ plans. The department also developed

- an assessment framework for emergency response assistance plans

- a new database for applicants to submit their plans and for departmental staff to track existing plans and review and make decisions on the approval of submitted applications

1.44 We also found that 194 of the department’s 923 plans (21%) had interim approval as of November 2019. Of these, 22 had had interim approval for more than 10 years. Exhibit 1.3 provides a timeline for 1 plan that had interim approval for 20 years.

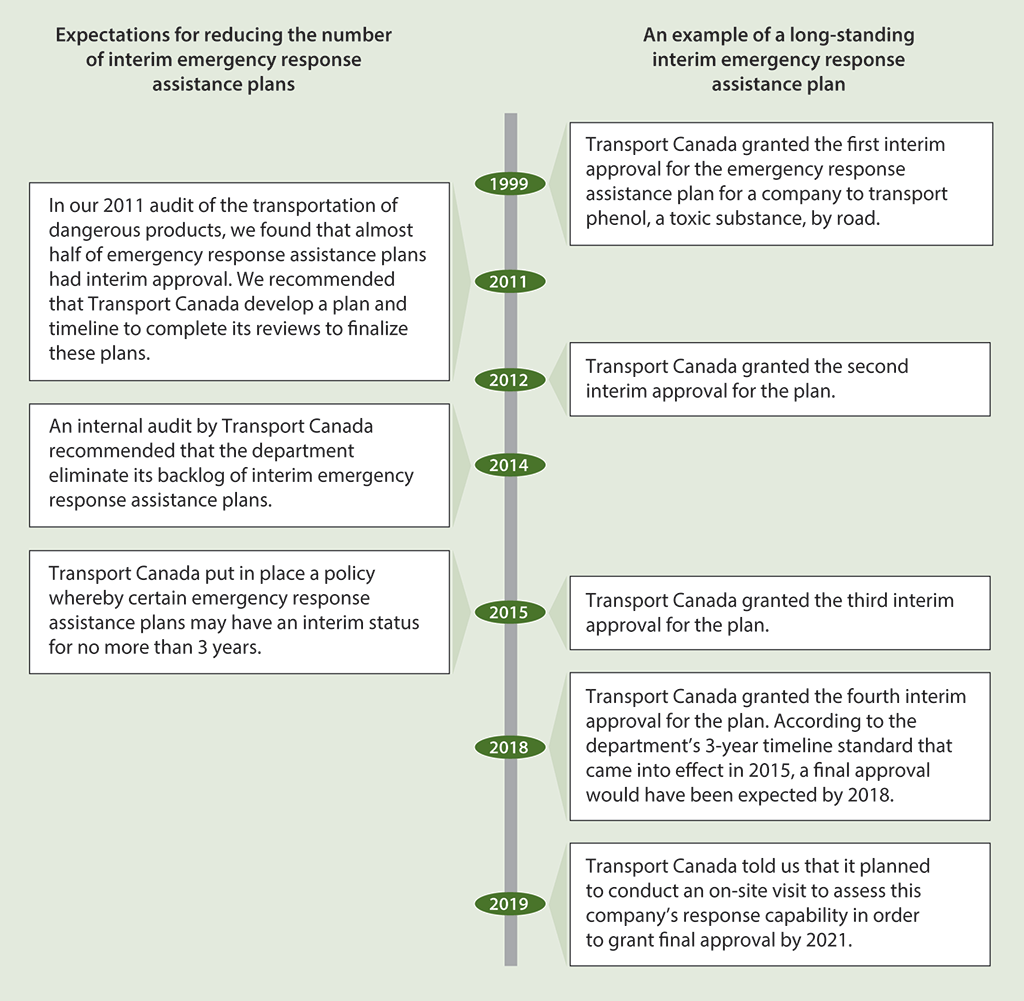

Exhibit 1.3—An emergency response assistance plan was granted multiple interim approvals over the past 20 years by Transport Canada

Exhibit 1.3—text version

This timeline shows the years in which Transport Canada granted interim approvals to 1 long-standing interim emergency response assistance plan and the years in which expectations for reducing the number of interim emergency response assistance plans were communicated:

The timeline is as follows:

- Transport Canada granted interim approvals for 1 long-standing interim emergency response plan as follows:

- In 1999, Transport Canada granted the first interim approval for the emergency response assistance plan for a company to transport phenol, a toxic substance, by road.

- In 2012, Transport Canada granted the second interim approval for the plan.

- In 2015, Transport Canada granted the third interim approval for the plan.

- In 2018, Transport Canada granted the fourth interim approval for the plan. According to the department’s 3-year timeline standard that came into effect in 2015, a final approval would have been expected by 2018.

- In 2019, Transport Canada told us that it planned to conduct an on-site visit to assess the company’s response capability in order to grant final approval by 2021.

- The expectations for reducing the number of interim emergency response plans were communicated as follows:

- In 2011, in the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s audit of the transportation of dangerous products, we found that almost half of emergency response assistance plans had interim approval. We recommended that Transport Canada develop a plan and timeline to complete its reviews to finalize these plans.

- In 2014, an internal audit by Transport Canada recommended that the department eliminate its backlog of interim emergency response assistance plans.

In 2015, Transport Canada put in place a policy whereby certain emergency response assistance plans may have an interim status for no more than 3 years.

1.45 We also found that the department was not meeting its own timelines to finalize its approval of interim plans. In 2015, the department put in place a policy whereby certain emergency response assistance plans may have an interim status for no more than 3 years, as determined by a review of the initial information submitted. We found that as of November 2019, of the 194 interim plans, 70 (36%) had been interim for more than 3 years.

Transport Canada recognizes that there are risks associated with large volumes of dangerous goods moving through communities by rail. Examples of dangerous goods shipped by rail include crude oil, gasoline, diesel, aviation fuel, and ethanol.

Photo: Office of the Auditor General of Canada

1.46 The department told us that 2 of the key reasons why plans were still interim were the following:

- Some plans required the department to make an on-site visit to assess response capability, such as verifying emergency equipment. However, these visits had yet to be made. Such visits may be part of an investigation that is required before the plans receive final approval.

- Other plans could not be finalized until Transport Canada developed national guidance and criteria for assessing the firefighting capacity for plans related to flammable liquids, such as petroleum products. Improving firefighting capability for flammable liquids was recommended by a task force the department created in response to the 2013 Lac-Mégantic rail disaster in Quebec.

Because of the unfinished investigations and guidance needed to give final approval to many of the interim plans, the department did not have all the information necessary to confirm that these regulated companies were fully prepared to respond to an emergency.

1.47 We also found that for these 70 interim plans, Transport Canada allowed the approval period to be reset 1 or more times on its 3-year timeline standard. For example, if in the second year of its interim plan a company submitted new information, such as additional dangerous goods it would be handling, then the department would often provide another full 3 years of interim approval.

1.48 Recommendation. Transport Canada should finalize its approval of the interim emergency response assistance plans by completing the necessary investigations and by developing national guidance and criteria for assessing firefighting capacity for plans related to flammable liquids. The department should ensure that approvals for all future plans are finalized within its prescribed timelines.

The department’s response. Agreed. Transport Canada will undertake the following activities:

- By 31 December 2020, develop tools to identify, assign, and track necessary investigations for existing and future emergency response assistance plans.

- By 1 January 2021, determine the necessary firefighting capacity for flammable liquids within an emergency response assistance plan and establish the related assessment criteria and guidelines.

- By 1 January 2021, update policies, procedures, and guidelines related to the assessment of emergency response assistance plans.

- By 1 December 2021, complete the necessary investigations for emergency response assistance plans that have been interim for 3 or more years.

Transporting dangerous goods by pipeline

Welded sections of a pipeline

Photo: Canada Energy Regulator

1.49 The Canada Energy Regulator has the role of verifying that companies meet approval conditions for oil and gas pipelines. Pipeline approval conditions are project-specific requirements attached to the regulator’s approval. These conditions may cover a range of topics, such as

- protection of critical habitat

- reporting on economic opportunities for Indigenous groups

- safety and engineering requirements, such as pressure testing

Conditions are established when the project is initially approved but may apply at various stages of the pipeline life cycle.

1.50 The Canada Energy Regulator must also verify that companies are building and operating pipelines according to regulatory requirements intended to protect the safety of Canadians and the environment. The regulator’s compliance verification work includes inspections, audits, meetings, emergency response exercise evaluations, and reviews of information filed by companies. It must effectively track and document its compliance activities and its follow-up of deficiencies.

The Canada Energy Regulator improved its compliance oversight

1.51 We found that since our 2015 audit, the Canada Energy Regulator improved its compliance oversight. It implemented an information and database management system to meet the needs of its compliance oversight activities, and it improved its follow-up to ensure that companies had taken corrective action to address non-compliance.

1.52 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

- Improved information management for compliance oversight

- Incomplete documentation on the analysis of pipeline approval conditions

- Improved follow-up on non-compliance

1.53 This finding matters because the Canada Energy Regulator is responsible for ensuring that companies return to compliance when violations have been identified and that they comply with all pipeline approval conditions in order to protect the safety of Canadians and the environment.

1.54 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 1.61.

Improved information management for compliance oversight

1.55 In 2015, we found that the National Energy Board (former name of the Canada Energy Regulator) had significant challenges with its information management system, including missing and out-of-date information on pipeline approvals and conditions. In this follow-up audit, we found that the Canada Energy Regulator improved its management of compliance-related information. Most notably, to resolve the problems we identified in 2015, the regulator developed and implemented the Operations Regulatory Compliance Application (ORCA) database to track and document its compliance verification activities and later added capabilities to track companies’ completion of pipeline approval conditions.

1.56 We found that the Canada Energy Regulator also developed procedures and guidance for staff to use ORCA. The regulator provided training on ORCA to its compliance officers and to the project managers responsible for monitoring whether companies satisfied pipeline approval conditions.

1.57 In our examination of the ORCA database, we observed opportunities for improvement in 3 areas of its design:

- The database did not routinely provide the regulator with reminders of due dates by when pipeline approval conditions should be verified or when companies should submit evidence that they took corrective actions. The database could be set up to provide automatic reminders for staff to ensure timely follow-up.

- Documentation related to management system audits and enforcement actions such as warning letters were mostly kept outside of the ORCA database. This information could be tracked in ORCA to minimize the risk of regulatory oversight error.

- In 5 of the 81 files we examined, a condition or a sub-component of a condition either was not uploaded or was only partially uploaded to the database, because the system allowed only manual input. Manual input poses a risk that a condition could be forgotten or not completed as required. The input of conditions into the ORCA database could be automated to remove the possibility of human error.

Incomplete documentation on the analysis of pipeline approval conditions

1.58 In 2015, we found that the National Energy Board (former name of the Canada Energy Regulator) did not systematically track compliance with pipeline approval conditions or adequately document this oversight work. In this follow-up audit, we examined a sample of conditions in effect during the 2018–19 fiscal year. We found that the regulator improved its tracking and documenting of its oversight of pipeline approval conditions in some areas. For example, in all 36 cases we examined, the regulator obtained and recorded submissions from the companies to support that they met a pipeline approval condition. We found that in 34 (94%) of 36 cases, the regulator documented its conclusion as to whether the condition had been implemented to its satisfaction.

1.59 However, the database was missing evidence in other areas. The regulator expects its staff to record their assessments of the documents submitted by companies in support of meeting pipeline approval conditions. The regulator also requires that these assessments explain and provide sufficient justification on how the submissions met or did not meet the requirements of the pipeline approval condition. We found that in 15 (42%) of 36 cases, there was little or no evidence that the regulator analyzed how the companies’ submissions met or did not meet the condition requirements (Exhibit 1.4). It is important that the regulator document its justification that a company has satisfied pipeline approval conditions in order to ensure that all requirements have been met.

Exhibit 1.4—The Canada Energy Regulator did not adequately document its analysis of how a company met the pipeline approval condition about crossing bodies of water

In 1 case we examined, the pipeline approval condition had 4 requirements regarding the pipeline’s crossing of bodies of water. Two of the requirements were that the company file with the regulator

- an updated inventory of all water bodies to be crossed, including details on the presence of fish and fish habitat

- a discussion of the potential impact to commercial, recreational, and Aboriginal fisheries

The only analysis by the regulator of the company’s filings that we found was an email on file stating that the condition was “acceptable.” There was no analysis of why the filings were considered acceptable or whether each requirement was met. The regulator told us that “the Environmental Technical staff reviewed the filings and acknowledge that the company had met the intent of the condition … .” However, the regulator could provide no additional documentation in support of its analysis.

1.60 We also found that in 7 (19%) of 36 cases, some of the required fields in the Operations Regulatory Compliance Application database were blank. The missing information included whether a condition had been met and the reviewer’s justification for this conclusion. A summary of these findings is in Exhibit 1.5.

Exhibit 1.5—Tracking compliance with pipeline approval conditions in the 36 cases we examined

Improved oversight

|

The Canada Energy Regulator verified that companies provided the required documentation to support the completion of a pipeline approval condition. |

36 of 36 (100%) |

|

The Canada Energy Regulator documented its conclusion as to whether a condition had been satisfactorily implemented. |

34 of 36 (94%) |

Areas for improvement

|

The Canada Energy Regulator did not complete documentation of its analysis of how companies’ submissions met or did not meet the condition requirements. |

15 of 36 (42%) |

|

The Operations Regulatory Compliance Application database had incomplete information in one or both of the following fields:

|

7 of 36 (19%) |

1.61 Recommendation. The Canada Energy Regulator should ensure that it has documented its analysis of companies’ submissions about how pipeline approval conditions have been satisfied.

The regulator’s response. Agreed. The Canada Energy Regulator monitors companies’ pipeline approval conditions throughout all phases of the pipeline life cycle. The Canada Energy Regulator is committed to more consistently documenting its analysis on how the company submissions met or did not meet the condition.

By May 2020, the Canada Energy Regulator will review its current procedures and quality controls and develop corrective actions to ensure a consistent approach to the documentation of the analysis of company submissions for pipeline approval conditions.

Improved follow-up on non-compliance

1.62 In 2015, we found that the National Energy Board (former name of the Canada Energy Regulator) did not systematically verify that companies took actions to correct non-compliance within the required timeline. In this follow-up audit, we found that the regulator had since done so in most of the cases we examined.

1.63 We examined a sample of 31 non-compliance cases the regulator identified in the 2018–19 fiscal year. We found the following:

- In all 31 cases, companies submitted evidence that they took corrective actions to return to compliance.

- In 27 cases (87%), inspectors analyzed the company’s documentation to verify that corrective actions were taken that addressed the non-compliance.

- In 29 cases (94%), the inspector’s final conclusion on company compliance was clearly identified in the database.

Conclusion

1.64 We concluded that, despite making some progress on each of the findings from our 2011 audit of the transportation of dangerous products, Transport Canada did not complete all the actions needed to address key aspects of our 2011 recommendation, including

- improving the quality of information for risk-based planning and inspections

- improving follow-up to ensure that companies had taken corrective action on violations

- improving its performance measurement system to be able to fully understand rates of regulatory compliance

- completing the work needed to grant final approval to the emergency response assistance plans that had remained interim for more than 3 years

1.65 We also concluded that the Canada Energy Regulator had largely implemented the 3 recommendations that we examined from our 2015 report on the oversight of federally regulated pipelines. The regulator implemented an information and data management system to meet the needs of its compliance oversight activities, and it improved its follow-up on non-compliance identified through its compliance verification activities. However, the regulator did not always document its analysis of how companies satisfied their pipeline approval conditions.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on the transportation of dangerous goods. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs, and to conclude on whether the management of the transportation of dangerous goods complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements, set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada applies the Canadian Standard on Quality Control 1 and, accordingly, maintains a comprehensive system of quality control, including documented policies and procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine the extent to which Transport Canada and the Canada Energy Regulator implemented our 2011 and 2015 recommendations regarding their compliance and enforcement responsibilities to ensure that dangerous goods are transported safely.

Scope and approach

We examined whether Transport Canada had

- put in place a national risk-based planning process that detailed how to consider risks, and how to prioritize inspections

- put in place guidance for inspectors on how to conduct and document compliance monitoring and follow-up activities

- clarified roles and responsibilities for monitoring compliance with the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Act, 1992 and its regulations

- implemented a performance measurement system that allowed the department to understand the rate of regulatory compliance

- developed guidance for the review and approval of emergency response assistance plans, and completed reviews according to its timeline standards

We examined whether the Canada Energy Regulator had

- assessed and addressed its information and data management requirements to ensure that they aligned with its critical business processes for regulatory compliance oversight

- put in place the procedures and tools to systematically track and document compliance with pipeline approval conditions

- put in place the procedures and tools to systematically verify that companies took corrective actions on violations within required timelines

The first part of the audit approach was to examine the progress that Transport Canada made on each of the elements of recommendation 1.45 from our 2011 audit report on the transportation of dangerous products, and that the Canada Energy Regulator (formerly the National Energy Board) made on recommendations 2.33, 2.44, and 2.54 from our 2015 audit report on the oversight of federally regulated pipelines. Our assessment included determining whether controls were put in place to address the deficiencies that we had identified in our previous audits. Our assessment of controls included considering new regulations, policies, directives, frameworks, procedures, guidance and tools, operating manuals, action plans, agreements, information systems, and training sessions that had been developed or improved and implemented.

The second part of the audit approach was to determine whether selected regulatory oversight controls worked as designed by using representative sampling to examine files.

For Transport Canada, we used representative sampling to examine inspection files that identified non-compliance between 1 April 2018 and 31 March 2019. These samples were sufficient in size to project to the sampled population with a confidence level of 90% and a margin of error (confidence interval) of +10%. We examined whether follow-up compliance activities and enforcement actions (where required) were conducted according to regulatory requirements and Transport Canada’s procedures to ensure that the regulated companies took corrective actions.

For the Canada Energy Regulator, we also used representative sampling to examine the controls related to the follow-up on compliance verification activities and to the oversight of pipeline approval conditions. These samples were sufficient in size to project to the sampled population with a confidence level of 90% and a margin of error (confidence interval) of +10%.

- We took a sample of selected compliance verification activities, which identified non-compliance between 1 April 2018 and 31 March 2019. We examined whether follow-up compliance activities and enforcement actions (where required) were conducted according to regulatory requirements and the regulator’s procedures to ensure that the regulated companies took corrective actions according to established timelines.

- We also took a sample of pipeline approval conditions that were, or became, active between 1 April 2018 and 31 March 2019. We examined the regulator’s tracking of pipeline approval conditions and whether it verified that regulated companies had complied with these conditions. Where any deficiencies were identified, we examined whether follow-up activities were conducted according to regulatory requirements and the regulator’s procedures to ensure that the regulated companies corrected deficiencies within established timelines and that the regulator took enforcement actions (where required).

During our audit period, the National Energy Board became the Canada Energy Regulator on 28 August 2019.

In 2017, the Office of the Auditor General of Canada committed to examining through our audit work how federal organizations are contributing to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. To this end, we examined whether Transport Canada’s activities were making progress toward Goal 3. We specifically looked at target 3.9: “By 2030, substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water, and soil pollution and contamination.” Transport Canada committed to having its Transportation of Dangerous Goods Program work to meet this target through its actions on emergency prevention, preparedness, and response. The Canada Energy Regulator had no applicable United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal or target that we could examine in this audit.

Criteria

We used the following criteria to determine the extent to which Transport Canada and the Canada Energy Regulator implemented our 2011 and 2015 recommendations regarding their compliance and enforcement responsibilities to ensure that dangerous goods are transported safely:

To determine whether controls have been put in place

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Transport Canada has put in place the controls to address each of the elements of recommendation 1.45 from the 2011 audit, which are as follows:

|

|

|

The Canada Energy Regulator has put in place the controls to address selected recommendations from the 2015 audit, which are as follows:

|

|

To determine whether controls have worked as designed

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Transport Canada conducts follow-up activities and takes enforcement actions (where required), on identified non-compliance, according to regulatory requirements and departmental procedures to ensure that corrective actions are implemented by the regulatees. |

|

|

The Canada Energy Regulator conducts follow-up activities and takes enforcement actions (where required), on identified non-compliance, according to regulatory requirements and the regulator’s procedures to ensure that corrective actions are implemented by the regulated companies within established timelines. |

|

|

The Canada Energy Regulator tracks pipeline approval conditions and verifies that regulated companies comply with these conditions. Where any deficiencies are identified, the regulator conducts its follow-up activities according to regulatory requirements and regulator procedures to ensure that the deficiencies are corrected by the regulated companies within established timelines and that enforcement actions are taken (where required). |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period from 1 April 2018 to 31 March 2019. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies. However, to gain a more complete understanding of the subject matter of the audit, we also examined certain matters that preceded the start date of this period.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 9 March 2020, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

Principal: Kimberley Leach

Lead Director: James Reinhart

Director: David Normand

Jean-Pascal Faubert

Kamila Karolinczak

Tristan Matthews

Francis Michaud

List of Recommendations

The following table lists the recommendations and responses found in this report. The paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report, and the numbers in parentheses indicate the location of the related discussion.

Transporting dangerous goods by rail, road, ship, and air

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

1.27 Transport Canada should improve and update its tools and database to have more complete and accurate information on regulated companies and their compliance status and to better inform risk-based planning. (1.23 to 1.26) |

The department’s response. Agreed. Transport Canada will undertake the following activities:

|

|

1.33 Transport Canada should systematically track and document its verification that companies have returned to compliance after violations are found. (1.28 to 1.32) |

The department’s response. Agreed. Transport Canada will strengthen the application of, and the supporting training on, oversight procedures for follow-up activities conducted by inspectors after they detect non-compliance by regulated entities. Management will ensure that inspectors are aware of updated procedures and are able to apply appropriate quality controls. This is to be completed by spring 2021. |

|

1.34 Transport Canada should ensure that means of containment facilities with expired certificates are not conducting the activities for which the certificates were issued. (1.28 to 1.32) |

The department’s response. Agreed. Transport Canada will strengthen its standard operating procedures to ensure that

This work will be complete by spring 2021. |

|

1.41 Transport Canada should strengthen its processes for collecting data from its partners to better identify the national rate of regulatory compliance in the transportation of dangerous goods. (1.37 to 1.40) |

The department’s response. Agreed. Transport Canada will undertake the following activities:

|

|

1.48 Transport Canada should finalize its approval of the interim emergency response assistance plans by completing the necessary investigations and by developing national guidance and criteria for assessing firefighting capacity for plans related to flammable liquids. The department should ensure that approvals for all future plans are finalized within its prescribed timelines. (1.42 to 1.47) |

The department’s response. Agreed. Transport Canada will undertake the following activities:

|

Transporting dangerous goods by pipeline

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

1.61 The Canada Energy Regulator should ensure that it has documented its analysis of companies’ submissions about how pipeline approval conditions have been satisfied. (1.58 to 1.60) |

The regulator’s response. Agreed. The Canada Energy Regulator monitors companies’ pipeline approval conditions throughout all phases of the pipeline life cycle. The Canada Energy Regulator is committed to more consistently documenting its analysis on how the company submissions met or did not meet the condition. By May 2020, the Canada Energy Regulator will review its current procedures and quality controls and develop corrective actions to ensure a consistent approach to the documentation of the analysis of company submissions for pipeline approval conditions. |