2016 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada Report 1—Venture Capital Action Plan

2016 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada Report 1—Venture Capital Action Plan

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- List of Recommendations

- Exhibits:

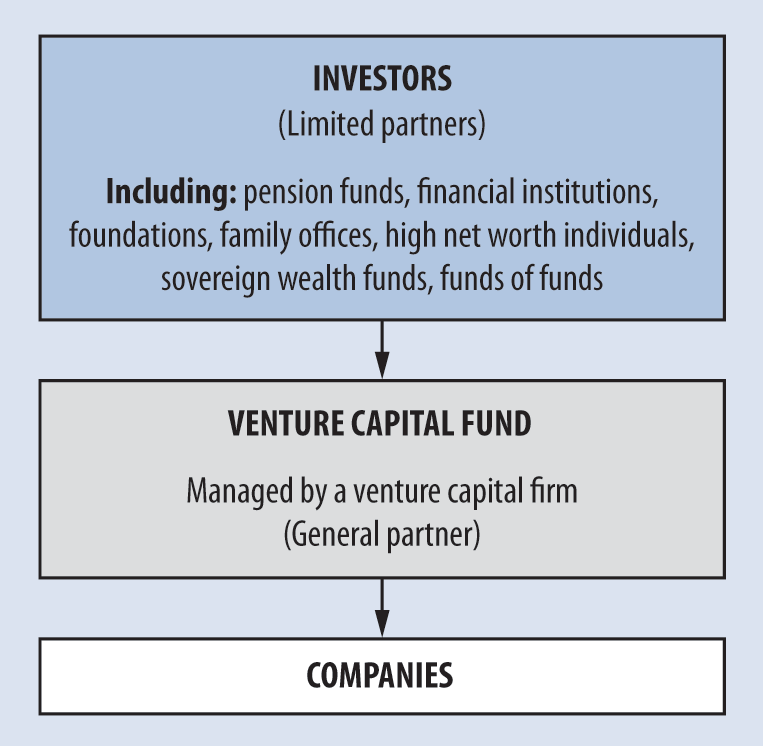

- 1.1—Basic relationships in venture capital investing

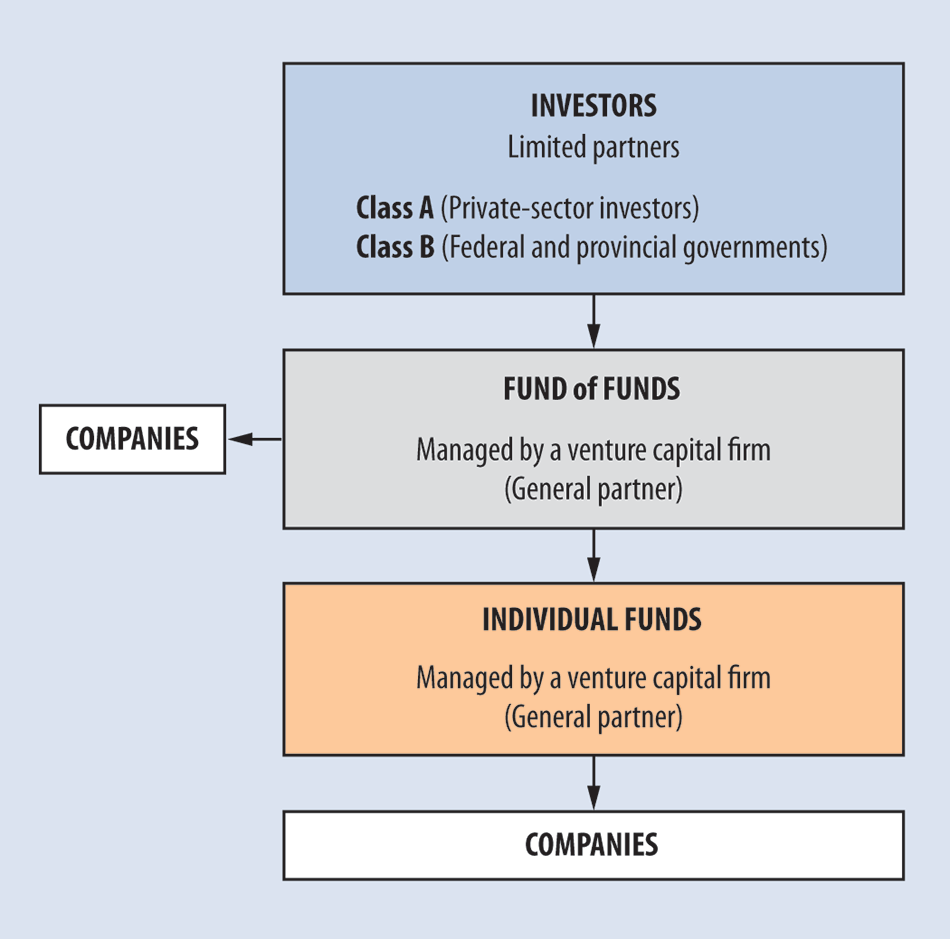

- 1.2—The fund-of-funds model involves a double layer of management and fees

- 1.3—The Venture Capital Action Plan invested in four funds of funds and four high-performing funds

- 1.4—More comprehensive indicators could provide better performance information

Introduction

Background

Early stage—The stage at which a company has been established but has not yet started generating revenues. Typically, an early-stage company has a core management team and a proven concept or product, but does not have a positive cash flow.

1.1 Venture capital is a mechanism for financing new, innovative companies before and at the early stages of commercialization. A venture capital firm invests third-party funds in such companies in return for an equity share. When a company develops its ideas to the stage where its commercial potential is sufficiently proven, the venture capital firm is able to sell its equity in the company and then returns to third-party investors the funds received from them plus any profits.

1.2 Venture capital is a major source of financing for innovative, high-growth firms and their entrepreneurial owner-managers. Venture capital investment in early-stage firms has helped to create and grow many of today’s leading global technology companies. Venture capital–backed firms have also made major contributions to the rapid commercialization of advanced technologies in the fields of medicine and new materials.

1.3 Venture capital firms provide long-term, committed share capital that is generally not secured by any assets. Companies backed by venture capital are often involved in developing disruptive technologies, which means that the companies are high-risk but offer the potential for high returns. If a company is successful, the venture capital firm realizes a capital gain when it sells its investment. There are two main ways of realizing this gain:

- Initial public offering: The company offers shares to the public and is listed on a stock exchange.

- Acquisition: A larger, more established company, usually in the same sector, buys out a smaller, developing company.

1.4 Venture capital investments are often made through a fund, that is, a pool of capital from a number of investors. The funds are typically structured as limited partnerships. The fund managers, referred to as general partners, raise money from investors (limited partners), including both individuals and institutions. The managers then seek out companies in which to invest. The investing cycle for a fund is usually around five years, after which the focus is on managing and making follow-up investments in the fund’s existing portfolio. Even if most of the investments prove unsuccessful, a few successful investments may cover the costs of investing in the entire portfolio and may generate an attractive return for investors. It can take several years for successful businesses to mature, and during this time, investors generally cannot withdraw their capital. The life of a fund is typically 10 to 15 years.

1.5 Investors, investment firms, and young companies are the three essential components of a venture capital ecosystem. Other components include academic institutions; research organizations; providers of legal, accounting, and other services; and large corporations. The components interact as a system to create and grow new companies (Exhibit 1.1). Many countries are interested in promoting such an ecosystem, since venture capital is widely recognized to be a key driver of innovation and economic development in advanced economies.

Exhibit 1.1—Basic relationships in venture capital investing

Venture capital is money provided to a company that is trying to develop a new idea.

The company is often at an early stage of development. It has been established but has not yet started generating revenues.

Governments may decide to provide venture capital in the case of a market gap—that is, lack of availability of sufficient investment capital to meet the needs of firms in a particular sector or sectors. To increase the total amount of money provided, a government may seek to involve private-sector investors in its venture capital initiative.

The money is pooled in a fund. This is often structured as a limited partnership, with the terms set out in a limited partnership agreement.

The fund manager, or general partner, undertakes fundraising from the public and the private sectors and selects businesses to receive funding.

Investors in the fund are limited partners. They are not involved in managing the fund or choosing the recipients of funding. However, as members of a limited partnership advisory committee, they provide advice to the general partner on specific issues.

In the case of a fund of funds, capital does not go directly to enterprises. Instead, it goes to individual (or underlying) funds, which in turn seek out opportunities for growth on behalf of the fund of funds. The fund of funds becomes a limited partner in the individual funds.

Years may pass before a business is capable of operating without assistance. For this reason, the business may need follow-up funding after the original investment, and the general partner may need to undertake several rounds of fundraising.

Diagram—text version

The relationships in venture capital investing can involve investors, a venture capital fund, and companies seeking funding.

Investors in a venture capital fund are limited partners, which can include pension funds, financial institutions, foundations, family offices, high net worth individuals, sovereign wealth funds, and funds of funds.

Investments are made through a venture capital fund that is managed by a venture capital firm The fund managers, referred to as general partners, raise money from investors.

The managers of venture capital funds then seek out companies in which to invest.

1.6 For years, governments in Canada have been concerned about the lack of capital available for new and early-stage entrepreneurial ventures. Several governments have attempted a public response to what they perceived as a market failure: they have set up programs to channel funding to high-potential, young enterprises that are in need of capital.

1.7 In 2010, the Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC) completed a review of the Canadian venture capital industry and its own venture capital operations. The review identified a number of issues faced by the national venture capital ecosystem beyond the simple lack of capital:

- persistent low returns for venture capital investors, resulting in a lack of private-sector investor confidence;

- the reluctance of institutional investors, such as banks and pension funds, to invest in innovative early-stage firms;

- the relatively small size of venture capital funds in Canada; and

- a shortage of experienced fund managers capable of leading successful venture capital funds.

1.8 Together, these findings suggest the problem is not only a financing gap that can be solved by simply supplying public money, or a demand-side problem attributable to the poor quality of firms. Instead, the findings of BDC’s review highlight that in the Canadian venture capital market, there are small numbers of high-potential firms and small numbers of investors with the skills to help them grow; and consequently, to find one another, firms and investors incur high transaction and/or search costs. The result is a reduction in the overall levels of investment.

1.9 To address the above-mentioned issues, in Budget 2012, the Government of Canada announced $400 million to help increase private-sector investments in early-stage venture capital, and to support the creation of large-scale venture capital funds led by the private sector. After government-led consultations with various stakeholders, on 14 January 2013 the government announced the Venture Capital Action Plan, to make available

- $250 million to establish new, large, private sector–led national funds of funds;

- up to $100 million to recapitalize existing large private sector–led funds of funds; and

- an aggregate investment of up to $50 million in three to five existing high-performing venture capital funds in Canada.

1.10 At the same time, the government announced the objectives of the Venture Capital Action Plan:

- Act as a catalyst in the development of a sustainable venture capital ecosystem led by private-sector investments. This includes participation by domestic and international institutional investors, as well as large-scale venture capital funds managed by the private sector.

- Increase the number of successful Canadian companies by encouraging private-sector investments in early-stage venture capital and helping to ensure that high-potential innovative firms have access to financing.

- Contribute to the development of a deeper pool of experienced fund managers in Canada, including by attracting foreign expertise and capital to Canada’s venture capital market.

Consolidated Revenue Fund—The general pool of income of the federal government. All money received by the federal government must be credited to this fund and properly accounted for.

1.11 As a self-sustaining Crown corporation, BDC does not receive government appropriations and does not appear in the government’s Estimates. It receives government funding by issuing shares to its sole shareholder, the Government of Canada. The $400-million Action Plan initiative was financed through that mechanism. The shares may be issued only to the designated minister (the Minister of Innovation, Science and Economic Development, formerly the Minister of Industry), to be held in trust for the Crown. The amount of the subscription is paid to BDC out of the Consolidated Revenue Fund. It takes the form of a non-budgetary transaction and represents a financial claim held by the government.

1.12 Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (formerly Industry Canada) does not report on the BDC shares in its financial statements because it passes the entire amount of the subscription to BDC. It reports only budgetary expenditures related to the Department.

1.13 Three federal organizations shared responsibilities for the Venture Capital Action Plan. The Department of Finance Canada was responsible for

- undertaking research and supporting consultations;

- seeking interest from private-sector investors and provincial governments to invest in the funds of funds;

- supporting the Venture Capital Expert Panel, a body appointed by the Minister of Finance to provide advice and recommendations on key selection processes;

- negotiating contractual agreements with general partners, potential private-sector investors, and interested provinces for the funds of funds; and

- working together with Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada officials in support of BDC’s role.

1.14 Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada was responsible for providing analytical support and advice to the Department of Finance Canada on venture capital, particularly during the early stages of the Action Plan initiative and during the consultation process.

1.15 BDC was entrusted with the following main duties for the Action Plan:

Distributions—Returns that investors in a venture capital fund receive.

- providing advice to the Expert Panel established by the government to help implement the Action Plan;

- fulfilling, as the agent of government, the duties typical of a limited partner;

- performing administrative duties, such as providing capital to the general partners, and eventually receiving distributions from the Action Plan investments; and

- monitoring, reporting, and informing officials from the Department of Finance Canada and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada about developments related to the initiative.

Focus of the audit

1.16 This audit focused on the Venture Capital Action Plan. The Department of Finance Canada, the Business Development Bank of Canada, and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (formerly Industry Canada) have roles and responsibilities for the Action Plan. We examined whether those federal organizations properly assessed the policy need, and designed and implemented the Action Plan in order to meet its stated objectives. We also examined whether the two departments and the Business Development Bank of Canada, consistent with their roles and responsibilities, measured and monitored the performance of the Action Plan against the stated objectives and intended outcomes.

1.17 This audit is important because the government chose to commit $400 million for the purpose of supporting innovation, and for creating jobs and growth.

1.18 This audit is not about the Canadian venture capital industry or the attractiveness of venture capital as an asset class. The findings and recommendations in the audit should not be seen or interpreted as commenting on the financial strategies of the fund managers or on the potential financial returns of the program.

1.19 More details about the audit objectives, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Creation of the Venture Capital Action Plan

1.20 Overall, we found that the Department of Finance Canada, the Business Development Bank of Canada, and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada assessed the policy need prior to the announcement of $400 million for early-stage venture capital in Budget 2012.

1.21 We found that when it made the announcement, the Government of Canada had not decided how to allocate the money. The government then held consultations with stakeholders, a process that helped to design the Venture Capital Action Plan. The government faced difficulty in convincing private-sector investors to participate in the Action Plan, which contributed to delays in implementation. Among the factors behind the reluctance were low returns, as well as strict international regulatory requirements for certain private-sector investors. Further, management fees could amount to approximately $250 million of the total amount ($1.35 billion) committed to funds of funds over the lifetime of the Action Plan.

1.22 These findings are important because the venture capital ecosystem in Canada has been facing structural challenges, including the risk-averse culture of Canadian institutions and the relative ease of obtaining funding from United States investors. An optimal set of parameters and flexible investment conditions were therefore essential for the Action Plan to meet its objectives.

1.23 In the long term, if the Action Plan did not succeed in helping to provide the intended high returns, it would be even harder to convince private-sector investors to participate in later efforts to support Canada’s venture capital industry.

1.24 For the Venture Capital Action Plan, the government used the model of the fund of funds. It combined this with a smaller investment in high-performing funds—that is, funds with good past performance—to respond to the pressing need for additional money in the venture capital market.

1.25 With the fund-of-funds model for the Action Plan, public-sector investors take more risk than private-sector investors. There are two classes of investors: Class A for private-sector investors and Class B for federal and provincial governments that invest. Class B investors provide money earlier but receive distributions only after Class A investors receive a predetermined level of returns. This is the incentive that the government chose to encourage private-sector participation in the Action Plan.

1.26 The model of the fund of funds has advantages and disadvantages (Exhibit 1.2).

Exhibit 1.2—The fund-of-funds model involves a double layer of management and fees

Exhibit 1.2—text version

The diagram shows the fund-of-funds model. In this model, investors are limited partners. There are two classes of investors: Class A for private-sector investors and Class B for federal and provincial governments.

The fund of funds is managed by a venture capital firm. The fund managers, referred to as general partners, raise money from investors (limited partners). The venture capital firm seeks out companies in which to invest.

In the fund of funds model, the venture capital firm invests in individual funds that are managed by another venture capital firm. The managers of the individual funds (general partners) also seek out companies in which to invest.

In this model, there are two layers of management and of fees: one layer is for the individual funds and the second layer is for the fund of funds. Investors pay fees to the two venture capital firms that manage the two types of funds.

1.27 Advantages of the fund-of-funds model. The main advantage of the fund-of-funds model is that it avoids a situation in which a government chooses recipients of investments (“picks the winners”) without having the necessary expertise. It also allows for better risk diversification.

1.28 The federal government chose the fund-of-funds model because it wished to increase the number of large, skilled general partners (that is, fund managers) in the Canadian venture capital ecosystem. Smaller general partners lack the operating budget needed to attract top-tier global partners, and they often lack sufficient capital to follow through on an investment. Further, the fund-of-funds model can increase the sophistication of the process of fund selection and capital allocation, which should lead to improved industry performance over the long term. Funds of funds can also help smaller or less experienced investors to gain access to new types of investments.

1.29 Disadvantages. A common criticism of the fund-of-funds model is the high cost of investing, as a result of the double layer of fees. Because of the high fees, the returns are lower with this model. To lessen this disadvantage, in some jurisdictions funds of funds are government-operated, thereby lowering management fees for investors. This is the case in New Zealand, for example. Similarly, within Canada, the Alberta Enterprise Corporation operates that province’s fund of funds.

1.30 In addition, the double layer of management means that performance tracking can be challenging with the fund of funds, and there is less control of capital for limited partners.

1.31 There is growing worldwide interest in co-investments—that is, investments made by limited partners alongside experienced general partners. A model such as this could be more appropriate when the venture capital ecosystem in Canada has matured and there are enough committed and experienced private-sector investors.

The government performed preliminary analysis of the market gap before the Budget 2012 announcement

1.32 We found that before it announced $400 million in funding in March 2012, the government had performed analysis on

- the size of the market gap,

- the sectors of investment, and

- the developmental stage of enterprises needing venture capital.

Officials from the Department of Finance Canada told us that the size of the market gap informed the size of the federal government’s investment in the Action Plan. In summer 2012, the government held consultations on the design of the Action Plan. In response to the consultation findings, the Department of Finance Canada designed the program to be flexible in determining the investments that fund-of-fund managers and high-performing fund managers could make.

1.33 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

1.34 This finding matters because the intent of the Action Plan initiative was to be a catalyst for the development of a sustainable venture capital ecosystem. The Department of Finance Canada, the Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC), and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada determined the size of the initiative so that, with private-sector leveraging, it would be able to respond to the market gap. There can be unintended consequences if the government establishes a program without having properly defined the support needed in terms of elements such as amount of funding required, the stage of development of enterprises that will receive funds, and the industry sectors to be targeted. Underfunding certain areas would limit the capacity to make follow-up investments as enterprises grow. Overfunding other areas would encourage investments of lower quality, thus generating lower returns and misallocating government money.

1.35 Action Plan investments are aggregated under the category of Loans, Investments, and Advances for reporting in the consolidated financial statements of the Government of Canada. So far, Action Plan investments did not affect the federal government’s fiscal balance. Eventually, annual realized and unrealized gains and losses resulting from Action Plan investments will be reflected in the government’s annual results of operations.

1.36 We made no recommendations in this area of examination.

1.37 What we examined. We examined whether the Department of Finance Canada, BDC, and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada conducted sound analyses that led to a program designed to address Canadian venture capital market challenges in a manner complementary to existing venture capital programs.

1.38 Analysis supporting the market gap. We found that BDC analyzed the venture capital funds that were raising capital by industry sector, geographic region of investments, and developmental stage of enterprises. BDC calculated the demand for venture capital over the following three years and the supply of money that was available. This determined the size of the market gap and informed the decision to invest $400 million in venture capital at the time of Budget 2012.

1.39 The government originally intended the Venture Capital Action Plan to support early-stage venture capital. However, many stakeholders in the consultations indicated that there might also be a gap in later stages of the development process, when enterprises need follow-up funding.

1.40 The Venture Capital Action Plan focuses on the information and communication technology sector and, to a lesser extent, on life sciences and clean technology. According to stakeholders, Action Plan support might have been beneficial for other specific sectors, such as agriculture and natural resources, where innovation is required to maintain Canada’s competitiveness. The government decided that the Action Plan would not give overall priority to agriculture and natural resources. Instead, the limited partnership agreements of the selected funds of funds allow investments in those sectors.

1.41 Design of the Venture Capital Action Plan. Following the initial announcement of $400 million in funding, in summer 2012 the government met with approximately 250 stakeholders to discuss the design of the Action Plan. In addition, stakeholders provided some 80 written submissions. The government held consultation sessions across Canada as well as in hubs of venture capital activity in the United States.

1.42 During the consultations, stakeholders mentioned that Canada’s venture capital market had a pressing need for additional money. In response, the government set aside $50 million of the $400 million in Action Plan funding to provide money to high-performing funds. Because of a simpler management structure, high-performing funds should be able to disburse money to reach the market more rapidly.

1.43 For the main component of the Action Plan, responsible for distributing $350 million, the government chose the fund-of-funds model. Other jurisdictions around the world chose the same model as a way to support their venture capital industry; an example is the United Kingdom. The fund-of-funds model was intended to complement other federal initiatives, such as BDC programs already supporting the venture capital industry. It involved private-sector investors, thus creating a leverage effect. The public-sector investors provided one third of the capital.

1.44 To meet the changing needs of the venture capital market, we found that the government allowed flexibility in the investments that fund-of-funds managers could make. The flexibility was reflected in the stage of development, geography, and industry sectors of potential recipients. This flexibility could prove to be useful in achieving higher returns. Best practices show that restrictions on investments should be kept to a minimum.

The government faced delays in attracting private-sector investors

1.45 We found that in the early days of the Action Plan, the government had encountered difficulties in convincing private-sector investors to participate as limited partners in the funds of funds. Among the reasons for the reluctance of the private sector to invest were the double layer of management fees payable in the case of funds of funds, the historically low returns on venture capital investments, and international regulatory requirements.

1.46 The Department of Finance Canada was aware of these challenges when it launched the Action Plan and sought the participation of Canada’s institutional and corporate strategic investors. The Department could have broadened its search further.

1.47 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

- delays in implementing the initiative,

- administrative costs inherent in the fund-of-funds model, and

- other factors limiting the participation of private-sector investors.

1.48 This finding matters because the Department of Finance Canada identified an immediate need in the venture capital market in 2012.

1.49 We made no recommendations in this area of examination.

1.50 What we examined. We examined whether the Department of Finance Canada, BDC, and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada properly implemented the Venture Capital Action Plan to attract and retain private-sector capital.

1.51 Delays in implementing the initiative. Given the needs of the market and the amount of public-sector funding available, the government decided that private-sector involvement was essential to fill the market gap.

1.52 In the early days of the Action Plan, convincing private-sector partners to invest was difficult despite the immediate needs of the market and the financial incentives embedded in the Action Plan. The Department of Finance Canada deployed considerable efforts to attract investment from Canadian banks, pharmaceutical companies, telecommunication firms, and subsidiaries of foreign high-tech companies. However, it could have broadened its search, including to foreign potential investors. The difficulty in convincing private-sector companies to invest led to delays in implementing the Action Plan.

1.53 We found that when the Action Plan was announced, some stakeholders adopted a wait-and-see approach before participating in the initiative and the venture capital market.

1.54 Administrative costs inherent in the fund-of-funds model. We found that the government set up its fund-of-funds model according to industry standards. Along with other lead investors, the government negotiated mutually acceptable distributions as well as expenses and management fees with the industry. The aim was to ensure that the government did not overpay, and at the same time that payments were sufficient to attract the participation of fund-of-funds managers.

1.55 Fund-of-funds managers receive approximately 0.5 percent to 1 percent per year of total investor commitments for the first five years, with the amount declining thereafter. In addition, approximately 2 percent per year goes to managers of underlying funds, that is, the individual funds in which a fund of funds invests. Allowing for other factors such as the flow of funds under management, we calculated that the double layer of management fees could amount to approximately $250 million of the total amount committed to funds of funds over the expected 13-year lifetime of the Action Plan.

1.56 We found that this double layer of fees reduced the return on investment for all investors, significantly limited the amount of capital available to entrepreneurs, and contributed to the difficulty faced by the Action Plan in attracting private-sector investors.

Internal rate of return—Interest rate that a certain amount of capital invested today would have to earn each year in order to grow to a predetermined value by a specific date.

1.57 Other factors limiting the participation of private-sector investors. Historically low returns on venture capital investments have led Canadian banks, pension funds, and insurance companies to be particularly cautious about venture capital investments. In the period from 2004 to 2014, Canada had a return of about minus 4 percent. At least two funds of funds involved in the Action Plan were confident of their ability to deliver an internal rate of return of 15 to 25 percent over their lifetimes, based on their track records and industry practices.

1.58 Large pools of private capital, such as pension funds and banks, typically prefer other types of investments to venture capital because it is expensive for them to monitor these smaller investments and the returns are not as predictable.

1.59 Banks are subject to stricter international regulations. Since the 2008 financial crisis, capital reserve requirements have increased substantially for high‐risk investments. This has led banks to be more cautious about making venture capital investments.

Selection process

Some processes for selecting fund managers did not adhere to sound practices

1.60 Overall, we found that the Department of Finance Canada, with the support of the Business Development Bank of Canada and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, met its short-term goals of establishing two large-scale national funds of funds, recapitalizing two funds of funds, and providing $50 million to four high-performing funds. The government treated the selection of funding recipients as an investment process. Therefore, no federal government policies applied except the procedures for reviewing investment opportunities. The Department of Finance Canada established its own procedures to choose the fund-of-funds managers and high-performing fund managers of the Venture Capital Action Plan. The processes used to select fund managers were a blend of public- and private-sector practices. Together with the Venture Capital Expert Panel appointed by the Minister of Finance to make the selection, the three organizations assessed the applications and interviewed applicants. However, we found some significant shortcomings in the selection process for fund managers.

1.61 The shortcomings are related to the Call for Expressions of Interest itself and the review of applications. For example, when the Department of Finance Canada posted the Call for Expressions of Interest, it indicated that it reserved the right to make changes to the selection process and to select any firm that it preferred. The government undertook limited outreach to advertise the Call for Expressions of Interest. The government also selected a candidate that did not initially submit an expression of interest. We believe that these practices fell short of a sound process and were not in accordance with the government’s values of fairness, openness, and transparency.

1.62 This is important because a fair, open, and transparent selection process would encourage enterprises in the venture capital industry to have confidence in the way the Government of Canada chooses fund-of-funds managers and high-performing fund managers. The shortcomings encountered could lessen the willingness of other investment managers to participate in a similar selection process in the future.

1.63 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

1.64 During the consultations prior to the establishment of the Action Plan, there were many calls for a formal request for proposals or a competitive process. Among the stakeholders referring to this need were representatives of one of Canada’s associations of venture capital firms. Initially, the Department of Finance Canada considered that the Action Plan would require a competitive process. In the end, the Department approached this as an investment, not a procurement process.

1.65 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 1.81.

1.66 What we examined. We examined whether the Department of Finance Canada, the Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC), and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada adopted a sound selection process for fund-of-funds managers and high-performing fund managers.

1.67 Call for Expressions of Interest. In April 2013, the Department of Finance Canada advised the two major associations of venture capital firms in Canada about the upcoming posting. The Department posted a Call for Expressions of Interest on its website in May 2013.

1.68 One of the stated objectives of the Action Plan initiative included attracting foreign expertise to Canada’s venture capital market. In our opinion, however, more targeted outreach would have been necessary to achieve this objective. In the end, out of a field of about 100 potential applicants in North America, the Call for Expressions of Interest attracted only nine submissions from fund-of-funds managers. Some applicants heard about the Call for Expressions of Interest from contacts in the industry.

1.69 The documentation to be provided by applicants amounted in some cases to hundreds of pages. Applicants were allowed only a short time to respond: three weeks in the case of the high-performing funds and four weeks in the case of the funds of funds. For those who did not find out about the process early enough, it might have been difficult to develop a proper application.

1.70 The Call for Expressions of Interest did not explain the weighted criteria that would be used to evaluate applicant firms, with the result that applicants did not know where to put their efforts. In fact, the Expert Panel finalized the criteria after the launch of the selection process.

1.71 Further, when it launched the selection process, the Department of Finance Canada stated that it reserved the right at any time to “make changes, including substantial changes, to the selection process … [and] select any Firm as a Selected Candidate over a Candidate who is ranked the highest or whose submissions reflect the lower cost.”

1.72 As a result of these shortcomings, the government might not have had a wide enough selection from which to choose the fund-of-funds managers and high-performing fund managers for meeting the intended goals of the Venture Capital Action Plan.

1.73 Review of the applications. The application review process involved reviews by different teams and the Expert Panel. The Expert Panel also interviewed the applicants. Further, there was an interview with potential limited partners. BDC followed its investment procedures in its evaluation of potential candidates throughout the process.

1.74 One step in the review process involved the use of a formal evaluation grid, with criteria and weighted marks for each. We found that the weighting of the criteria changed during the review, affecting the ranking of the applicants.

1.75 We found that the government chose a fund-of-funds manager even though the firm did not respond to the Call for Expressions of Interest.

1.76 We also found that some applicants not chosen in the selection process tried to obtain feedback explaining why they were not selected, but they did not receive answers either formally or informally.

1.77 While we found that the government developed some good procedures for reviewing the applications, in practice there were problems with the way it actually evaluated and chose the fund-of-funds managers and high-performing fund managers.

1.78 Results of the selection process. The selection process had three short-term goals: to establish two new large-scale national funds of funds; to recapitalize two existing large-scale funds of funds that were private sector–managed; and to provide up to $50 million to between three and five existing high-performing venture capital funds that were private sector–managed.

1.79 We found that the government succeeded in reaching its identified short-term goals (Exhibit 1.3), but the manner in which it conducted the process might not have helped the Action Plan to achieve its objective of establishing a self-sustaining, privately led venture capital ecosystem in Canada.

Exhibit 1.3—The Venture Capital Action Plan invested in four funds of funds and four high-performing funds

Funds of funds

| Northleaf Venture Catalyst Fund | Recapitalized fund of funds. |

| Teralys Capital Innovation Fund | Recapitalized fund of funds. |

| Kensington Venture Fund | New fund of funds, created when Kensington Capital Partners (a private-equity fund-of-funds manager) launched its first fund of funds dedicated exclusively to venture capital. |

| HarbourVest Canada Growth Fund | New fund of funds. U.S. firm based in Boston; established an office in Toronto in 2015. |

High-performing funds

| CTI Life Sciences Fund II | The federal government announced $15 million for this fund in September 2013. |

| Real Ventures Fund III | The federal government announced $10 million for this fund in September 2013. |

| Lumira Capital II | The federal government announced $10 million for this fund in September 2013. |

| Relay Ventures III | The federal government announced $15 million for this fund in December 2014. |

Source: News releases from the Department of Finance Canada and information on fund managers’ websites

Fairness—A value that ensures decisions are made objectively; are free from bias, favouritism, or influence; and conform to established rules.

Openness—A value that ensures activities are accessible to all potential participants, without unjustified restrictions.

Transparency—A value that ensures information is provided to the public and interested parties in a timely manner that facilitates public scrutiny.

1.80 In our opinion, the Call for Expressions of Interest, the review of applications, and the selection of fund managers did not entirely adhere to sound practices and had a negative impact on fairness, openness, and transparency.

1.81 Recommendation. When making investments that are similar to those of the Venture Capital Action Plan, the Department of Finance Canada and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada should fully respect the values of fairness, openness, and transparency while meeting the purposes of the investment. This will maintain the venture capital industry’s confidence in selection processes run by the Government of Canada.

The departments’ response. Agreed. The government agrees that fairness, openness, and transparency are important principles for selection processes administered by the Government of Canada.

The Venture Capital Action Plan involved collaboration between private-sector and public-sector partners. In order to leverage the knowledge, expertise, and capital of private-sector partners, which are requirements for contributing to the success of the Action Plan, selection processes were designed to balance the private-sector principles of confidentiality and flexibility in negotiations, with the public-sector principles of fairness, openness, and transparency for overall benefits of the public interest.

Should the government decide to develop a new initiative that involves private-sector partnerships and formal selection processes to assist the government in making venture capital investments, as was the case under the Action Plan, it will, in the context of the venture capital market at that time, design the selection processes to balance the principles of confidentiality and flexibility for private-sector partners, and fairness, openness, and transparency for public-sector partners, to enable the success of the initiative.

Performance measurement and reporting

An appropriate set of performance indicators was not in place to assess the success of the Venture Capital Action Plan and inform its future directions

1.82 Overall, we found that the Business Development Bank of Canada properly managed the monitoring and reporting of activities of the Venture Capital Action Plan. The Business Development Bank of Canada also effectively transmitted the information that it gathered to the Department of Finance Canada and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada. However, the Performance Measurement Framework put in place by the two departments had a limited set of performance indicators and was not sufficient for assessing how the Action Plan fostered Canadian innovation and strengthened the economy.

1.83 In our opinion, the government could learn from other jurisdictions that have developed a more complete framework to assess the short-term results and longer-term outcomes of their publicly backed venture capital programs.

1.84 This is important because performance assessments are necessary to inform the future of the initiative; and for proper assessment, officials need to have a complete set of metrics on which they can rely to evaluate the performance of the Action Plan. According to various stakeholders, a decision about the future of the initiative might have to be made by the 2019–20 fiscal year. By then, the Action Plan’s high-performing funds as well as funds of funds will have invested most of their capital and will need to start fundraising again for follow-up funding.

1.85 Through its monitoring and reporting on Action Plan activities, the Business Development Bank of Canada ensured that contractual obligations were met and that officials from the Department of Finance Canada and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada were informed about the progress of the initiative. However, the departments did not make public the information collected by the Business Development Bank of Canada. We believe that public disclosure of relevant information about Action Plan activities and performance could benefit the Canadian venture capital market. It would increase the awareness among potential investors and would highlight the Canadian venture capital marketplace as being able to generate commercial returns from investing in young Canadian firms. It would also increase transparency for taxpayers.

1.86 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

- monitoring and reporting on Action Plan activities,

- completeness of indicators and timing of measurement,

- public disclosure of information, and

- exit strategy for the public sector.

1.87 The Department of Finance Canada and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada developed some performance indicators for the Action Plan. These include the aggregate financial returns of the Action Plan’s funds of funds, the total amount of investment in funds of funds supported by the Action Plan, and the number of venture capital funds of funds and high-performing funds supported by the Action Plan.

1.88 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 1.99 and 1.103.

1.89 What we examined. We examined whether the Department of Finance Canada, the Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC), and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, consistent with their roles and responsibilities, measured and monitored the performance of the Venture Capital Action Plan against the stated objectives and intended outcomes.

1.90 Monitoring and reporting on Action Plan activities. As the agent of government acting as a limited partner, BDC received information about activities of the funds of funds and the high-performing funds.

1.91 Clauses in the limited partnership agreements about reporting to limited partners were generally in line with industry standards. BDC sat on the limited partner advisory committees, enabling it to monitor the activities of the general partners and ensure that they met their contractual agreements.

1.92 BDC prepared quarterly reports and a detailed annual report about Action Plan activities.

1.93 BDC submitted its reports to the Department of Finance Canada and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada to keep officials informed about Action Plan activities.

1.94 Completeness of indicators and timing of measurement. We found that the Performance Measurement Framework developed by the Department of Finance Canada and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada had a limited set of key performance indicators for tracking results. The framework was also developed two years after the design of the initiative. In our opinion, the framework did not do enough to capture information about key outputs and outcomes.

1.95 Further, the performance measurement timeline set a date far in the future to start evaluating outputs. In our opinion, this will not provide information early enough to support important decisions, such as whether to launch a similar program in future. The Action Plan’s financial performance will not be formally evaluated before 2021; the long-term economic impact of the Action Plan will be evaluated in 2025 and 2030. Fund managers supported by the Action Plan that raise follow-up funding will be monitored only in 2020 and 2025. This will leave the government with little information when it is needed to support decisions related to the future of the Action Plan initiative.

1.96 More comprehensive indicators are available, as shown by the experience in other jurisdictions and as suggested by academic experts in the field (Exhibit 1.4).

Exhibit 1.4—More comprehensive indicators could provide better performance information

| Indicators | What they measure |

|---|---|

|

Indicators for measuring outputs |

Exit performance

|

|

Indicators for measuring outcomes |

Exports and financial performance

Commercialization of innovation

|

|

Indicators for measuring the development of fund managers |

Attractiveness of venture capital market

Fund managers’ skills and experience

|

1.97 Public disclosure of information. BDC reported on Action Plan activities, and informed the Department of Finance Canada and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada about the progress of the initiative. BDC’s information included metrics such as the aggregate internal rate of return of the funds of funds, the companies in which they invested, and an overview of the sector and geographic location of the investments. However, the departments did not make public the information collected by BDC.

1.98 In our opinion, publishing information about Action Plan activities and performance would help the government demonstrate to private-sector investors that commercial returns can be obtained from investing in early-stage companies. We understand that there are concerns about maintaining commercial confidentiality. At the same time, we believe there is a case for greater transparency. This would meet the legitimate needs of private-sector investors as well as the needs of taxpayers.

1.99 Recommendation. To appropriately assess the performance of the Venture Capital Action Plan and inform decision making, the Department of Finance Canada and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada should expand the Action Plan’s Performance Measurement Framework by considering the inclusion of performance metrics, such as

- exit performance of recipient companies,

- recipient companies’ export growth and their financial performance,

- new patents and patent citations, and

- the number of new or additional key investment personnel and lead investors.

To increase transparency, the two departments should report publicly relevant information about Action Plan activities and performance.

The departments’ response. Agreed. Performance measurement is an essential tool for assessing the Venture Capital Action Plan, and the evidence collected on the performance of the Action Plan’s investments will be important to the government as it develops future policy directions supporting innovative start-ups in Canada.

The government’s performance framework outlines key performance indicators with specific, measurable, and relevant targets and benchmarks. The framework includes an analysis of the long-term economic performance of the companies backed by the Action Plan compared to a baseline of non–venture capital supported companies using government databases.

In accordance with this recommendation, and subject to the availability of robust data, the government will update the Performance Measurement Framework to include additional metrics on exit performance, exports, financial performance, and key investment personnel. The framework will also cover innovation performance by including research and development spending and employment levels, as these are good indicators of innovation in venture capital–backed start-ups.

The government will publish relevant information about Action Plan activities and performance while respecting the confidentiality requirements in the agreements with the fund managers.

1.100 Exit strategy for the public sector. The main objective of the Action Plan is to create a self-sustaining, privately led venture capital ecosystem. With this purpose in mind, the Action Plan model is built around an incentivized structure to appeal to private-sector partners. However, the Action Plan does not provide for an exit of the public-sector partners during the lifetime of the funds. In our opinion, this could send a message that the public sector’s participation is intended to be permanent. An early-exit option would offer the possibility of timely disengagement by the government from its involvement in the venture capital funds.

1.101 An early exit of the public-sector partners could send a strong signal of the private-sector partners’ confidence that their returns at termination will be sufficient. In turn, this would suggest that the objective of creating a self-sustaining, privately led venture capital ecosystem is being achieved.

1.102 Another incentivized model, used in jurisdictions such as New Zealand and Israel, involves allowing (but not requiring) private-sector partners to purchase the government’s position after a certain time, at a price that would generate a predetermined rate of return to the government.

1.103 Recommendation. In formulating future interventions such as the Venture Capital Action Plan, the Department of Finance Canada and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada should allow for an early exit of the public-sector partners.

The departments’ response. Agreed. Should the government pursue future venture capital interventions whereby government capital is treated differently than private-sector capital, similar to the Venture Capital Action Plan, the government will consider a broad range of design parameters governing the participation of investors, which could include early-exit options. Parameters would be contemplated in the context of the maturity, sustainability, and nature of the venture capital market, and the objectives of the initiative.

Conclusion

1.104 We concluded that the Department of Finance Canada, the Business Development Bank of Canada, and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada assessed the policy need for the Venture Capital Action Plan prior to the Budget 2012 announcement and subsequently held extensive consultations with stakeholders to determine how to allocate the money. However, the selection of fund managers did not always adhere to sound practices because the process had important shortcomings with regard to fairness, openness, and transparency.

1.105 We also concluded that Action Plan activities were properly monitored. However, better performance indicators would help to measure the policy outcomes of the initiative and inform future policy decisions. Also, better public disclosure of the Action Plan’s performance could benefit the Canadian venture capital market. Finally, the Action Plan did not include an exit strategy to foster the transition to a self-sustaining, privately led ecosystem.

About the Audit

The Office of the Auditor General’s responsibility was to conduct an independent examination of the Venture Capital Action Plan to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs.

All of the audit work in this report was conducted in accordance with the standards for assurance engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance. While the Office adopts these standards as the minimum requirement for our audits, we also draw upon the standards and practices of other disciplines.

As part of our regular audit process, we obtained management’s confirmation that the findings in this report are factually based.

Objectives

The audit examined whether the Department of Finance Canada, the Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC), and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (formerly Industry Canada), consistent with their roles and responsibilities, properly assessed the policy need for, designed, and implemented the Action Plan in order to meet its stated objectives.

The audit examined whether the Department of Finance Canada, BDC, and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, consistent with their roles and responsibilities, measured and monitored the performance of the Action Plan against the stated objectives and intended outcomes.

Scope and approach

The scope of this audit included the Economic Development and Corporate Finance Branch at the Department of Finance Canada, the Business Development Bank of Canada, and the Small Business Branch at Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada. The audit examined the funds of funds and the high-performing funds in the Venture Capital Action Plan. It did not examine the Canada Accelerator and Incubator Program within the Action Plan.

The audit examined the analysis supporting the Action Plan and its design, the implementation of the Action Plan, and the performance measurement of the Action Plan. The audit did not comment on the financial strategies or potential returns of the Action Plan, or on the attractiveness of venture capital as an asset class.

We reviewed various documents, including briefing notes and analyses prepared by the two departments and BDC, written submissions and minutes of meetings for the consultations, applications for the selection process, and reports issued by foreign governments on their venture capital support programs. We also reviewed literature related to the issue of venture capital support programs.

In addition, we interviewed numerous Action Plan stakeholders, including private-sector investors and participants in the selection process.

Finally, we consulted with former federal government officials, experts in the field, and foreign government officials managing venture capital support programs.

Criteria

To determine whether the Department of Finance Canada, the Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC), and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, consistent with their roles and responsibilities, properly assessed the policy need for, designed, and implemented the Action Plan in order to meet its stated objectives, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

The Department of Finance Canada, BDC, and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada conduct sound analyses that lead to a solution designed to address Canadian venture capital market challenges in a manner complementary to existing venture capital programs. |

|

|

The Department of Finance Canada, BDC, and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada properly implement the Action Plan to attract and retain private-sector capital, select fund managers, and develop a pool of top-tier fund managers (venture capital investors) in a sustainable manner. |

|

To determine whether the Department of Finance Canada, BDC, and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, consistent with their roles and responsibilities, measured and monitored the performance of the Action Plan against the stated objectives and intended outcomes, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

The Department of Finance Canada, BDC, and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, according to their roles and responsibilities, define measurable and appropriate outcomes for the Action Plan and develop relevant performance indicators. |

|

|

The Department of Finance Canada, BDC, and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada monitor the implementation and have a framework to assess the performance and relevance of the Action Plan in order to adapt the initiative if necessary. |

|

Management reviewed and accepted the suitability of the criteria used in the audit.

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period between 1 January 2012 and 31 May 2015. The period under examination was extended back to 1 January 2010 for analyses of the Venture Capital Action Plan before its implementation. Audit work for this report was completed on 26 February 2016.

Audit team

Assistant Auditor General: Nancy Y. Cheng

Principal: Richard Domingue

Director: Philippe Le Goff

Alexandre Fortier-Labonté

Rose Pelletier

List of Recommendations

The following is a list of recommendations found in this report. The number in front of the recommendation indicates the paragraph where it appears in the report. The numbers in parentheses indicate the paragraphs where the topic is discussed.

Selection process

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

1.81 When making investments that are similar to those of the Venture Capital Action Plan, the Department of Finance Canada and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada should fully respect the values of fairness, openness, and transparency while meeting the purposes of the investment. This will maintain the venture capital industry’s confidence in selection processes run by the Government of Canada. (1.66–1.80) |

The departments’ response. Agreed. The government agrees that fairness, openness, and transparency are important principles for selection processes administered by the Government of Canada. The Venture Capital Action Plan involved collaboration between private-sector and public-sector partners. In order to leverage the knowledge, expertise, and capital of private-sector partners, which are requirements for contributing to the success of the Action Plan, selection processes were designed to balance the private-sector principles of confidentiality and flexibility in negotiations, with the public-sector principles of fairness, openness, and transparency for overall benefits of the public interest. Should the government decide to develop a new initiative that involves private-sector partnerships and formal selection processes to assist the government in making venture capital investments, as was the case under the Action Plan, it will, in the context of the venture capital market at that time, design the selection processes to balance the principles of confidentiality and flexibility for private-sector partners, and fairness, openness, and transparency for public-sector partners, to enable the success of the initiative. |

Performance measurement and reporting

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

1.99 To appropriately assess the performance of the Venture Capital Action Plan and inform decision making, the Department of Finance Canada and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada should expand the Action Plan’s Performance Measurement Framework by considering the inclusion of performance metrics, such as

To increase transparency, the two departments should report publicly relevant information about Action Plan activities and performance. (1.89–1.98) |

The departments’ response. Agreed. Performance measurement is an essential tool for assessing the Venture Capital Action Plan, and the evidence collected on the performance of the Action Plan’s investments will be important to the government as it develops future policy directions supporting innovative start-ups in Canada. The government’s performance framework outlines key performance indicators with specific, measurable, and relevant targets and benchmarks. The framework includes an analysis of the long-term economic performance of the companies backed by the Action Plan compared to a baseline of non–venture capital supported companies using government databases. In accordance with this recommendation, and subject to the availability of robust data, the government will update the Performance Measurement Framework to include additional metrics on exit performance, exports, financial performance, and key investment personnel. The framework will also cover innovation performance by including research and development spending and employment levels, as these are good indicators of innovation in venture capital–backed start-ups. The government will publish relevant information about Action Plan activities and performance while respecting the confidentiality requirements in the agreements with the fund managers. |

|

1.103 In formulating future interventions such as the Venture Capital Action Plan, the Department of Finance Canada and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada should allow for an early exit of the public-sector partners. (1.89, 1.100–1.102) |

The departments’ response. Agreed. Should the government pursue future venture capital interventions whereby government capital is treated differently than private-sector capital, similar to the Venture Capital Action Plan, the government will consider a broad range of design parameters governing the participation of investors, which could include early-exit options. Parameters would be contemplated in the context of the maturity, sustainability, and nature of the venture capital market, and the objectives of the initiative. |

PDF Versions

To access the Portable Document Format (PDF) version you must have a PDF reader installed. If you do not already have such a reader, there are numerous PDF readers available for free download or for purchase on the Internet: