2015 Fall Reports of the Auditor General of Canada Report 3—Implementing the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement

2015 Fall Reports of the Auditor General of Canada Report 3—Implementing the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement

Table of Contents

Production of our Fall 2015 reports was completed before the government announced changes to names of some departments. The name Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada was changed to Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. The name Environment Canada was changed to Environment and Climate Change Canada. There was no impact to our audit work and findings.

Introduction

Background

3.1 Comprehensive land claims and self-government agreements, also referred to as modern treaties, are fundamentally important to the parties that sign them, including the Government of Canada, provincial and territorial governments, and Aboriginal groups.

3.2 Comprehensive land claims agreements, according to the federal government, are meant to provide for legal certainty and clarity of rights to ownership and use of lands and resources in those areas where Aboriginal title has not already been decided. These agreements can cover a variety of topics such as the ownership, use, and management of land and natural resources; economic development; government contracting and procurement; public sector employment; wildlife and fisheries management; and environmental assessment.

3.3 Self-government agreements provide Aboriginal groups with greater responsibility for and control over internal affairs and decisions that affect their communities. These agreements address topics such as the accountabilities of Aboriginal groups, their law-making powers, and the financing of Aboriginal governments. Self-government agreements can be integrated into comprehensive land claims agreements or can stand alone.

3.4 In the Federal Framework for the Management of Modern Treaties and related Guide for Federal Implementers of Comprehensive Land Claims and Self-Government Agreements, the federal government states that these agreements are important for

- promoting strong and self-reliant Aboriginal communities,

- improving the social well-being and economic prosperity of Aboriginal people, and

- providing certainty for resource development.

3.5 The Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement (LILCA) was signed in 2005 by the Labrador Inuit, represented by the Labrador Inuit Association, and the governments of Canada and Newfoundland and Labrador. This comprehensive land claims agreement settled Aboriginal title and ownership of lands and resources, and set out ongoing relationships and obligations between the three signatories. These relationships and obligations are central to both comprehensive land claims and self-government agreements.

3.6 Nunatsiavut Government. The LILCA includes self-government provisions that enabled the creation of the Nunatsiavut Government. The Nunatsiavut Government has authority over a variety of areas, such as culture and language, education, healthcare, social services, housing, and environmental protection. The agreement also provides this government with law-making authority and taxation powers. According to the Nunatsiavut Government, there are about 7,200 beneficiaries of the agreement.

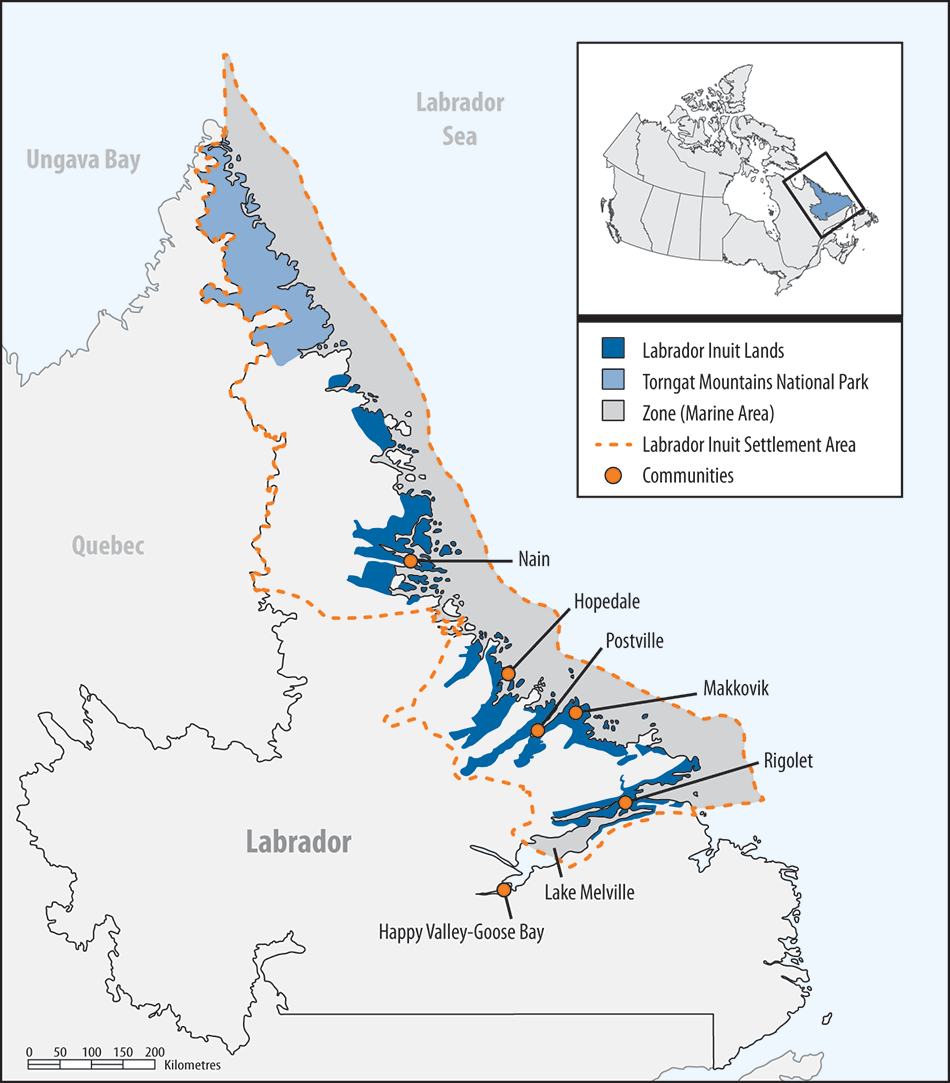

3.7 Labrador Inuit Settlement Area. By signing the LILCA, the Labrador Inuit obtained specific and defined rights (for example, with respect to the use of natural resources and the harvesting of plants and wildlife) within the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area (Exhibit 3.1). The settlement area is about 122,000 square kilometres, consisting of about 73,000 square kilometres of land and waters along the northeastern coast of Labrador, and almost 49,000 square kilometres of an adjacent marine zone. In the settlement area, the Labrador Inuit have title to approximately 16,000 square kilometres of land and waters known as the Labrador Inuit Lands. In exchange for the rights and benefits specified in the agreement, the Labrador Inuit ceded and released to Canada and the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador all Aboriginal rights they may have outside of the Labrador Inuit Lands except for a defined area of northeastern Quebec still subject to negotiation. The Labrador Inuit also ceded Aboriginal rights related to subsurface resources in the Labrador Inuit Lands.

Exhibit 3.1—The Labrador Inuit Settlement Area is about 122,000 square kilometres consisting of land and waters along the northeastern coast of Labrador and an adjacent marine zone

Source: Adapted from Government of Newfoundland and Labrador – Labrador and Aboriginal Affairs Office documentation

Exhibit 3.1—text version

This map shows that the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area consists of a long, narrow area of land and water along the northeastern coast of Labrador. The area begins in the northern tip of Labrador, where Ungava Bay meets the Labrador Sea. The area ends in the south at Lake Melville, to the northeast of Happy Valley-Goose Bay, a community that is not part of the settlement area. The settlement area includes an adjacent marine zone running along the Labrador Sea coast.

The settlement area includes the Torngat Mountains National Park in the northern tip of Labrador, between the Quebec border and the Labrador Sea. The area also includes Labrador Inuit Lands along the Labrador Sea coast.

The map shows the locations of several communities inside the settlement area, which are, from north to south: Nain, Hopedale, Postville, Makkovik, and Rigolet.

The information for this map was adapted from documentation from the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador—Labrador and Aboriginal Affairs Office.

3.8 Torngat Mountains National Park of Canada. The LILCA also led to the establishment of the Torngat Mountains National Park Reserve of Canada, located within the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area. The reserve became the Torngat Mountains National Park of Canada when the Nunavik Inuit Land Claims Agreement came into effect in 2008.

3.9 Side agreements. The LILCA is accompanied by a number of side agreements, including the following signed by the governments of Canada and Nunatsiavut:

- Fiscal Financing Agreement,

- Labrador Inuit Park Impacts and Benefits Agreement for the Torngat Mountains National Park Reserve of Canada.

3.10 The Fiscal Financing Agreement outlines the financial contributions that the federal government would provide to the Nunatsiavut Government and describes the programs and services the Nunatsiavut Government would deliver with this funding. In 2005, the agreement was signed for the period 2005 to 2010 (and was subsequently extended to 2012). This agreement was then renegotiated and signed for the period 2012 to 2017.

3.11 The Labrador Inuit Park Impacts and Benefits Agreement, signed in 2005, provides for the administration and maintenance of the Torngat Mountains National Park of Canada. The agreement ensures that the management of the park respects and reflects Inuit rights, and that Parks Canada and the Inuit have a framework for cooperatively managing the park.

3.12 The Government of Canada enters into land claims and self-government agreements on behalf of the federal Crown. Since many federal departments and agencies are involved in implementing these agreements, interdepartmental coordination and oversight are important. The Guide for Federal Implementers of Comprehensive Land Claims and Self-Government Agreements states that Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada is responsible for coordinating the implementation of the federal Crown’s obligations.

3.13 In the document entitled “Renewing the Comprehensive Land Claims Policy: Towards a Framework for Addressing Section 35 Aboriginal Rights,” the federal government acknowledges the importance of basing its relationship with Aboriginal peoples on mutual recognition and respect. It stresses the need to work cooperatively with Aboriginal groups when implementing land claims and self-government agreements. It also recognizes that, when implementing these agreements, federal departments and agencies should uphold the honour of the Crown. Specifically, these entities and their officials must act with honour, integrity, and fairness at all times when dealing with the Aboriginal parties involved. The honour of the Crown also requires that obligations in these agreements be interpreted in a reasonable and “purposive” manner, which means that the Crown must fulfill its obligations by pursuing their purpose and not interpreting them narrowly.

3.14 The Supreme Court of Canada has also stated that the Crown needs to take a broad purposive approach to interpreting its obligations and act diligently to fulfill them.

3.15 Audits by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada and a study by the Senate of Canada have previously reported on the implementation of comprehensive land claims agreements (Exhibit 3.2). These efforts identified common findings, including the following areas for improvement:

- dispute resolution,

- performance measurement, and

- systems for monitoring and reporting on land claims obligations.

Exhibit 3.2—Previously reported audits and study on the implementation of land claims agreements

| Year | Topic | Author |

|---|---|---|

| 2003 | Indian and Northern Affairs Canada—Transferring Federal Responsibilities to the North | Office of the Auditor General of Canada |

| 2007 | Inuvialuit Final Agreement | Office of the Auditor General of Canada |

| 2008 | Honouring the Spirit of Modern Treaties: Closing the Loopholes—Special Study on the Implementation of Comprehensive Land Claims Agreements in Canada | Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples |

| 2011 | Programs for First Nations on Reserves | Office of the Auditor General of Canada |

3.16 In early 2015, Douglas Eyford, Ministerial Special Representative to the Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development, prepared for the Minister a report entitled, “A New Direction: Advancing Aboriginal and Treaty Rights.” The report focused on negotiating and implementing land claims agreements. It recommended that the federal government increase awareness, oversight, and accountability for its obligations and that, among other things, it strengthen structures for coordinating and fulfilling obligations.

3.17 In July 2015, after the period covered by our audit, the Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development introduced a “whole-of-government” approach to the implementation of land claims and self-government agreements. He noted that this approach puts measures in place to manage the full scope of Canada’s responsibilities under these agreements. The Minister announced the following measures:

- a new Deputy Ministers’ Oversight Committee to provide ongoing, executive-level oversight and accountability for obligations and implementation of land claims and self-government agreements;

- a Modern Treaty Implementation Office within Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada to strengthen coordination and oversight across the federal government;

- a new Cabinet Directive on the Federal Approach to Modern Treaty Implementation, outlining roles and responsibilities of federal departments and agencies;

- a new Statement of Principles on the Federal Approach to Modern Treaty Implementation, which states, among other things, that modern treaties establish clarity and certainty with respect to the ownership and management of lands and resources, and that the honour of the Crown must be upheld when implementing land claims and self-government agreements. The principles are meant to guide departments and agencies on how to fulfill their obligations, and dictate that obligations should be interpreted in a reasonable and purposive manner; and

- new tools, training, and guidance for federal officials to help them fulfill Canada’s responsibilities under the agreements.

Focus of the audit

3.18 This audit focused on whether Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Parks Canada, and Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada were implementing selected obligations in the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement (LILCA) and two related side agreements, the Fiscal Financing Agreement and the Labrador Inuit Park Impacts and Benefits Agreement for the Torngat Mountains National Park Reserve of Canada (Labrador Inuit Park Impacts and Benefits Agreement).

3.19 We also examined whether the above entities monitored the status of their obligations, and whether this information was shared with Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada to help it coordinate and report on the implementation of the LILCA.

3.20 This audit is important because implementing obligations contributes to promoting strong and self-reliant Inuit communities, improving the social well-being and economic prosperity of the Inuit people, and providing certainty to all parties with respect to resource development. Furthermore, implementing obligations can foster a collaborative relationship, which reduces the potential for litigation.

3.21 We examined the following selected obligations, because of the potential benefits they could provide to the Labrador Inuit if implemented:

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada and its obligations related to commercial fishing of northern shrimp and to negotiating an arrangement for communal food fishing licences for beneficiaries living in Labrador but outside the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area;

- Parks Canada and its implementation of selected commitments contained in the Labrador Inuit Park Impacts and Benefits Agreement; and

- Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada and its obligation related to negotiating the Fiscal Financing Agreement (on behalf of the federal Crown) with the Nunatsiavut Government to support self-government.

3.22 We also examined whether the above entities plus Environment Canada tracked federal contracts issued within the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area and whether this information was shared with Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada for public reporting purposes, as required by the Treasury Board’s Contracting Policy.

3.23 More details about the audit objectives, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Implementing obligations in the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement

3.24 Overall, we found that the federal government made progress in implementing selected obligations in the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement (LILCA) and related side agreements, but that some challenges remained. We found ongoing differences in interpretations between Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Nunatsiavut Government over fisheries-related obligations. We also found that Parks Canada has acted upon commitments set out in the Labrador Inuit Park Impacts and Benefits Agreement, resulting in economic benefits including employment for the Labrador Inuit. Finally, we found that the Fiscal Financing Agreement signed by Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada provided financial support to the Nunatsiavut Government, which has been important for its self-government. However, the lack of a federal program for Inuit housing has affected the Nunatsiavut Government’s ability to fulfill housing responsibilities it received by signing this side agreement.

3.25 We also found that Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada’s system for tracking the status of obligations was not yet being used to its full potential; opportunities exist to expand the system to include benefits resulting from the implementation of obligations. A plan has been developed to expand the capabilities of the system to allow it to better support departments and agencies involved in implementing land claims agreements. We also found that the entities were not adequately tracking and sharing information on federal contracts for goods and services issued within the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area, as required by Treasury Board policy. As a result, Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada’s public reporting on federal contracting activities within the settlement area was incomplete.

3.26 These findings are important because failing to consistently implement obligations in the LILCA and related side agreements jeopardizes the certainty that parties to the agreements hoped to achieve. It also affects efforts by all parties to improve the social well-being and economic prosperity of the Labrador Inuit. Moreover, the federal government risks litigation if its obligations go unfulfilled.

3.27 According to the Guide for Federal Implementers of Comprehensive Land Claims and Self-Government Agreements, all federal departments and agencies must ensure that they fulfill their obligations under these agreements in an appropriate and timely manner. The Guide also states that departments and agencies must implement their obligations with due regard for clarity, consistency, and coordination.

Progress was made implementing some obligations, but challenges remained regarding fisheries and housing

3.28 We found ongoing differences in interpretation over the obligation to provide the Nunatsiavut Government with commercial fishing access to the northern shrimp fishery.

3.29 We also found that between 2006 and 2015, the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans issued annual communal fishing licences to the Nunatsiavut Government. These licences allowed beneficiaries to the LILCA living in Labrador, but outside the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area, to fish for food, social, and ceremonial purposes. However, the Nunatsiavut Government and Fisheries and Oceans Canada differed over whether the actions taken by the Minister met the LILCA obligations.

3.30 We found that, through its operation of the Torngat Mountains National Park of Canada, Parks Canada provided employment to the Labrador Inuit and economic opportunities for Inuit businesses. Parks Canada implemented many of the commitments we examined and made progress in implementing the Labrador Inuit Park Impacts and Benefits Agreement.

3.31 Finally, we found that Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, on behalf of the federal Crown, signed a 2012–2017 Fiscal Financing Agreement that provided financial support to the Nunatsiavut Government. The Nunatsiavut Government received some funding for housing through both the Fiscal Financing Agreement and other one-time funding sources. However, the lack of a federal program for Inuit housing south of the 60th parallel has limited the Nunatsiavut Government’s ability to fulfill housing responsibilities it received by signing the Fiscal Financing Agreement.

3.32 Our analysis supporting these findings presents what we examined and discusses

- access to the northern shrimp fishery,

- communal harvesting of fish outside the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area,

- implementation of the Labrador Inuit Park Impacts and Benefits Agreement, and

- fiscal financing including funding for housing.

3.33 Fisheries. Ongoing differences in interpretation have resulted in uncertainty. The Nunatsiavut Government is uncertain about its access to the northern shrimp fishery—an important economic opportunity for the Labrador Inuit. The Nunatsiavut Government asserts that it has not participated in the shrimp fishing industry as much as expected under the provisions outlined in the LILCA. According to the Nunatsiavut Government, this reduced participation limited its efforts to develop the economy within Labrador Inuit communities. Further, because of differences in interpretation regarding communal harvesting obligations, there is uncertainty for beneficiaries of the LILCA regarding their ability to fish for food, social, and ceremonial purposes outside of the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area after 2015.

3.34 National parks. Parks Canada’s implementation of the Labrador Inuit Park Impacts and Benefits Agreement has provided the Inuit with economic benefits in a remote region of Canada with limited economic opportunities. In addition, Parks Canada’s actions have helped the Labrador Inuit maintain and strengthen their connection with their traditional homeland and assisted in preserving their history and culture. Parks Canada’s approach to managing the Torngat Mountains National Park of Canada helped it foster a collaborative relationship with the Nunatsiavut Government.

3.35 Fiscal financing including funding for housing. The financial support made available through fiscal financing agreements provided the Labrador Inuit with the means and resources to govern their internal affairs. However, from the Nunatsiavut Government’s perspective, inadequate funding for housing has limited its ability to address the housing needs of Nunatsiavut residents.

3.36 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 3.57, 3.58, 3.68, and 3.77.

3.37 What we examined. We examined the implementation of selected obligations in the LILCA and related side agreements with respect to the following topics:

- commercial fishing access to the northern shrimp fishery;

- communal harvesting of fish by beneficiaries living outside the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area;

- employment for the Inuit and opportunities for Inuit businesses resulting from Parks Canada’s operation of the Torngat Mountains National Park of Canada;

- preserving, managing, and safekeeping archaeological materials in the park; and

- the process and factors considered in negotiating the 2012–2017 Fiscal Financing Agreement between the Nunatsiavut Government and the Government of Canada.

Special allocation—An allocation given for certain species of fish harvested under the authority of a licence issued pursuant to the Fisheries Act. Fisheries and Oceans Canada requires that the recipient of the special allocation identify the existing licence holder under which the special allocation is to be harvested; the Department modifies that licence accordingly. The allocations are provided on a one-time basis only and include a number of criteria such as, but not limited to, proximity to the resource and economic circumstances. These special allocations remain static over time and are subject to the “last in, first out” approach (see paragraph 3.49).

3.38 Access to the northern shrimp fishery. Under the authority of the Fisheries Act, the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans can provide individuals and organizations (including Aboriginal groups) with access to commercial fishing opportunities by issuing commercial fishing licences. A fishing licence grants permission to harvest certain species of fish subject to the conditions attached to the licence. The Minister may also provide special allocations to individuals or organizations for certain species of fish without issuing a licence. Both licences and special allocations are issued at the discretion of the Minister.

3.39 The northern shrimp fishery, located off the coast of Labrador, is an important economic sector for the Inuit. Section 13.12.7 of the LILCA states that if, after the agreement comes into effect, the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans “decides to issue more Commercial Fishing Licences to fish for shrimp in Waters Adjacent to the [Labrador Inuit Settlement Area marine] Zone than the number available for issuance in the year of the Agreement, the Minister shall offer access to the Nunatsiavut Government through an additional Commercial Fishing Licence issued to the Nunatsiavut Government or by some other means to 11 percent of the quantity to be Harvested under those licences.”

3.40 Section 13.12.9 further states that if “the system for allocating commercial opportunities in relation to a species or stock of Fish . . . changes from the system existing on the Effective Date [of the agreement], the Minister shall offer to the Nunatsiavut Government participation under the new system that is at least as favourable as that set out” for northern shrimp in section 13.12.7.

3.41 We found that Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Nunatsiavut Government have differences of interpretation regarding obligations related to the northern shrimp fishery, including

- when the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans is required to offer the Nunatsiavut Government access to the northern shrimp fishery,

- what constitutes a change to the system for allocating commercial opportunities to fish,

- how existing licence holders should be considered when deciding on the quota that should be allocated to the Nunatsiavut Government, and

- how reductions in fishing quotas are managed.

3.42 According to the Department’s interpretation of section 13.12.7, the Minister is required to offer the Nunatsiavut Government access to the northern shrimp fishery only when the Minister issues new licences. The Department’s position is that no new licences have been issued since the LILCA was signed; therefore, this obligation has not been triggered.

3.43 The Nunatsiavut Government’s position is that the Minister is obligated to provide a minimum of 11 percent of an increase in the allowable harvest of northern shrimp in one of two circumstances: when the Department issues new licences or when the Department increases the amount of shrimp allocated to those permitted to harvest the resource. The Nunatsiavut Government negotiated and signed the agreement with this understanding and expectation in mind.

Shrimp fishing area—Shrimp fishing along Canada’s eastern coast is divided into specific fishing zones known as shrimp fishing areas (SFAs). SFA 4 and SFA 5 are within and adjacent to the marine zone of the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area.

3.44 We found that the Minister had not issued new licences for the northern shrimp fishery since 2005. However, between 2005 and 2015, the Minister did increase the amount of northern shrimp that the fishing industry was allowed to catch in waters adjacent to the marine zone (in Shrimp Fishing Area 4) of the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area. The amount increased by 4,651 metric tonnes, with increases in 2008, 2012, and 2013. As part of these increases, the Nunatsiavut Government received a special allocation in 2012 of 300 metric tonnes, which represented 6.5 percent of the total increase in allowable catch. However, based on its interpretation of the LILCA, the Nunatsiavut Government expected to receive 11 percent of the total increase. According to the Department, it gave this special allocation of 300 tonnes outside the context of the agreement and therefore the agreement’s provisions were not applicable.

3.45 We found that between the signing of the agreement in 2005 and up to 2008, officials from the Department communicated that the Department would offer the Nunatsiavut Government access to the northern shrimp fishery if the Department issued new licences or announced quota increases. This position, which was consistent with the Nunatsiavut Government’s interpretation, was communicated both internally in the Department and externally. According to the Department, it was not until 2008, when the first quota increase was announced, that the Department formally assessed its obligation. As a result of this assessment, the Department has since maintained that if new commercial licences are made available it has to provide the Nunatsiavut Government with 11 percent of the quantity of fish to be harvested under the new licences through a new licence to the Nunatsiavut Government, or by some other means.

3.46 Opinions also differ over what constitutes changes to the system for allocating commercial opportunities to fish. For example, in 2013, the Department revised the boundaries of the areas it uses to manage the shrimp fishery. The Nunatsiavut Government felt that these boundary adjustments constituted changes to the system for allocating commercial opportunities to fish, which would trigger section 13.12.9 of the LILCA. The Department disagreed. We found that the Department did not formally define what constitutes a change in the system for allocating commercial opportunities to fish. In our opinion, without such a definition, it is not clear what situations would trigger the obligation.

3.47 The Department and the Nunatsiavut Government also differ on how to consider existing licence holders when deciding on the quota to allocate to the Nunatsiavut Government. In particular, two organizations involving the Labrador Inuit hold licences for shrimp fishing:

- Torngat Fish Producers Co-Operative Society, Limited—Largely owned by beneficiaries (this organization holds one licence for shrimp fishing).

- Nunatsiavut Group of Companies—Describing itself as the business arm of the Nunatsiavut Government (this organization holds one half of a licence).

3.48 In the Department’s opinion, since Labrador Inuit beneficiaries are involved in these organizations, these beneficiaries—and by extension the Nunatsiavut Government—obtain benefits from any increased allocations to these organizations. In contrast, the Nunatsiavut Government’s opinion is that allocations to these organizations—which are separate and distinct from the Nunatsiavut Government—should not influence decisions on whether the Nunatsiavut Government should receive a share of any increases in shrimp quota. Furthermore, the Nunatsiavut Government noted that section 13.12.7 states that if the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans issues more licences, the Nunatsiavut Government, not the Labrador Inuit, is to be offered access to the fishery (see paragraph 3.39). This situation has created further disagreement on the Nunatsiavut Government’s access to the northern shrimp fishery.

3.49 We found that the Department applied a “last in, first out” (LIFO) approach to reduce northern shrimp fishing quotas. LIFO means that those who last entered the fishery will be the first to experience cuts to their quota(s) should reductions below a certain threshold occur in a shrimp fishing area. This approach has left the Nunatsiavut Government uncertain about its continued access to northern shrimp. The LILCA is silent on how a potential decline in fishing quotas would affect the Nunatsiavut Government’s allocations of the northern shrimp harvest. We also noted that the Department’s documentation indicates that applying the LIFO approach should be subject to land claims agreements.

3.50 In 2014, in response to conservation concerns, the Minister lowered the amount of northern shrimp that the fishing industry was allowed to catch. LIFO was applied, and consequently some allocations in SFA 5 were reduced, including the Nunatsiavut Government’s. Since the Nunatsiavut Government was one of the last to enter the shrimp fishery, this reduction was consistent with the Department’s LIFO approach.

3.51 We found that the Nunatsiavut Government objected to the reduction to its quota. Since it had less than 11 percent of the overall quota (the percentage specified in the LILCA), the Nunatsiavut Government believed that its quota should not have been reduced. The Nunatsiavut Government also believed that the LIFO approach was inconsistent with the constitutional protection provided by the agreement. In its view, the agreement should have taken precedence over the Department’s approach to reducing fishing quotas. The Department’s view is that the allocation given to the Nunatsiavut Government was outside the provisions of the agreement and that LIFO therefore applied.

3.52 Communal harvesting of fish outside the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area. We found that opinions differed on whether the Department fulfilled the obligation contained in LILCA sections 13.13.1 and 13.13.2. These sections relate to negotiating an arrangement to issue communal food fishing licences for the Upper Lake Melville area. This arrangement would allow communal harvesting for food, social, or ceremonial purposes, by beneficiaries living in Labrador but outside the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area. Section 13.13.2 states that the arrangement would be for a period of nine years and that before the end of this period, the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans may extend the arrangement.

3.53 Before the LILCA’s signing in 2005, the Minister issued annual communal fishing licences to the Labrador Inuit that allowed them to fish for food, social, and ceremonial purposes in Upper Lake Melville. We found that, for the nine years between 2006 and 2014, the Department annually negotiated with the Nunatsiavut Government a communal fishing licence for food, social, and ceremonial purposes. A licence was also negotiated for 2015. In the Department’s opinion, by negotiating and issuing annual communal fishing licences since 2006, it had fulfilled its obligation to provide for communal fishing outside of the settlement area.

3.54 We also found that the Department and the Nunatsiavut Government were negotiating a nine-year comprehensive fisheries agreement for Upper Lake Melville. The agreement would explain how the two parties would work together to manage the fishery in Upper Lake Melville. Communal fishing licences, negotiated annually, would form part of the agreement.

3.55 The Nunatsiavut Government’s position is that because it has not yet signed the comprehensive fisheries agreement with the Department, the obligation regarding communal fishing in Upper Lake Melville has not been met. Therefore, the nine-year period has not yet started. The Nunatsiavut Government is of the opinion that a nine-year arrangement would provide longer-term certainty for its beneficiaries.

3.56 In our opinion, the ongoing disagreements have created uncertainty regarding the Nunatsiavut Government’s access to the northern shrimp fishery while inhibiting the parties from working together to increase Inuit participation in the shrimp fishing industry. The disagreements have also created uncertainty regarding the communal harvesting by beneficiaries in the Upper Lake Melville area. Furthermore, we are concerned that these disagreements may negatively affect the relationship between the two parties while creating the potential for litigation. The dispute resolution mechanisms in the LILCA have not been used to resolve these issues.

3.57 Recommendation. Fisheries and Oceans Canada should work with the Nunatsiavut Government to clarify and agree on the intent of the obligations regarding the Nunatsiavut Government’s access to the northern shrimp fishery. They should also agree on what constitutes changes to the system for allocating commercial opportunities to fish. If the differences remain unresolved, the matter should be brought to the Dispute Resolution Board as provided for in the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response. Agreed. Fisheries and Oceans Canada is willing to work with the Nunatsiavut Government to clarify the intent of the obligations around the shrimp fishery, including defining what constitutes changes to the system. Failing that, Fisheries and Oceans Canada would agree to mechanisms under the Dispute Resolution chapter of the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement while ensuring that the Minister’s discretion under the Fisheries Act is not fettered. Timelines for implementing this recommendation will be discussed with the Nunatsiavut Government as part of our ongoing discussions on fisheries-related issues.

3.58 Recommendation. Fisheries and Oceans Canada should work with the Nunatsiavut Government to agree on the status of the obligation regarding communal harvesting in the Upper Lake Melville area. If the differences remain unresolved, the matter should be brought to the Dispute Resolution Board as provided for in the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response. Agreed. Fisheries and Oceans Canada is willing to participate with the Nunatsiavut Government to clarify and explain our position on this matter. If agreement cannot be reached with the Nunatsiavut Government on the status of the obligation regarding communal harvesting in Upper Lake Melville, Fisheries and Oceans Canada would agree to mechanisms under the Dispute Resolution chapter of the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement, while ensuring that the Minister’s discretion under the Fisheries Act is not fettered. Timelines for implementing this recommendation will be discussed with the Nunatsiavut Government as part of our ongoing discussions on fisheries related issues.

3.59 Implementation of the Labrador Inuit Park Impacts and Benefits Agreement. The Labrador Inuit Park Impacts and Benefits Agreement includes commitments related to recruiting, hiring, and training Inuit employees and to providing economic opportunities to Inuit businesses.

3.60 We found that Parks Canada had implemented these commitments as follows:

- Parks Canada employed Inuit as full-time and seasonal staff to manage the park. It also employed Inuit elders and cultural performers, who enhanced visitor experiences while helping to preserve Inuit history and culture. It also provided training to Inuit staff.

- Parks Canada facilitated the recruitment of Inuit with input from the Torngat Mountains National Park Cooperative Management Board and the Nunatsiavut Government. For example, it included knowledge of Inuktitut as part of its hiring criteria and used the Nunatsiavut Government to help advertise job openings.

- According to Parks Canada, since the 2012–13 fiscal year, it had purchased almost $2.4 million worth of goods and services, including goods and services from Labrador Inuit businesses, in support of park operations. Goods and services provided included airplane and helicopter charter services, vessel support, park accommodations, fuel, and polar bear safety training.

3.61 Establishing and operating the park’s base camp has played an important role in the employment and economic benefits created for the Inuit. The base camp has also improved access to the park, allowing Inuit to connect more easily with their traditional homeland.

3.62 The park contains almost 400 known archeological sites related to the Inuit. The agreement requires that Parks Canada and the Nunatsiavut Government jointly develop and implement a memorandum of understanding on the presentation, management, and safekeeping of archaeological materials found in the park. A draft memorandum of understanding had been developed, and Parks Canada informed us that they expect to sign it in the fall of 2015.

3.63 The Labrador Inuit Park Impacts and Benefits Agreement recognizes the importance of archaeological materials to the Inuit and the Nunatsiavut Government’s role in safekeeping these materials. The agreement also provides that title and management of all archaeological materials found in the park are vested jointly in the governments of Canada and Nunatsiavut. However, despite recognizing the Nunatsiavut Government’s role, we found that Parks Canada decided, without consulting the Nunatsiavut Government, to move archaeological materials from the park (stored in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia), to Gatineau, Quebec, in 2018. Parks Canada officials have recognized this oversight and have since met with the Nunatsiavut Government to discuss its concerns.

3.64 In 2013, a Nunatsiavut Government official raised concerns with Parks Canada about damage to an archaeological site resulting from visitor activities in the park. In response, Parks Canada mapped and assessed the site and then managed visitor activities by, for example, restricting access to certain areas around the site and requiring visitors to be accompanied by a guide to minimize the risk of damage. Parks Canada has taken similar actions for some other frequently visited sites.

3.65 However, the Nunatsiavut Government remained concerned that visitors or researchers may damage archaeological materials and sites in other park locations. The Nunatsiavut Government would like Parks Canada to develop a formal process to help ensure that archaeological sites are protected and systematically considered when planning visitor and research activities in the park. In Parks Canada’s opinion, the memorandum of understanding (and other initiatives, including the development of a cultural resource values statement) will strengthen the existing formal policies and processes for managing archaeological sites and materials in the park, such as the Parks Canada Cultural Resource Management Policy and the research and collection permitting process.

3.66 One purpose of the Labrador Inuit Park Impacts and Benefits Agreement is to provide a framework for cooperative management, including a commitment to cooperatively establish, operate, and manage the park in a way that recognizes the Inuit as partners. Parks Canada acted on this commitment by creating a seven-Inuit-member Torngat Mountains National Park Cooperative Management Board, which provides advice to Parks Canada on all aspects related to the park’s management. The board is the first all-Inuit cooperative management board in Canada’s national parks system, and Parks Canada considers the board’s creation a best practice.

3.67 In our opinion, Parks Canada’s actions were consistent with its obligations as set out in the Labrador Inuit Park Impacts and Benefits Agreement and are a model for other federal departments and agencies. Furthermore, the collaborative and cooperative working relationship that Parks Canada has established with the Nunatsiavut Government, and the Inuit, is a good approach to implementing land claims agreements. Parks Canada’s actions also reflect the principle of pursuing the purpose of obligations rather than interpreting them narrowly.

3.68 Recommendation. Parks Canada should finalize, with the Nunatsiavut Government, the memorandum of understanding on the presentation, management, and safekeeping of archaeological material found in the Torngat Mountains National Park of Canada.

Parks Canada’s response. Agreed. Currently, Parks Canada and the Nunatsiavut Government are conducting respective legal reviews of the penultimate draft of the memorandum of understanding on the presentation, management, and safekeeping of archaeological materials in the Torngat Mountains National Park of Canada, with the shared intention to sign the memorandum in the fall of 2015 or as soon as possible, once the legal reviews are complete and the memorandum has been finalized.

3.69 Fiscal financing including funding for housing. The Fiscal Financing Agreement sets out federally funded programs and services for which the Nunatsiavut Government is responsible, including

Non-Insured Health Benefits Program for First Nations and Inuit—A federal program that provides coverage to First Nations and Inuit for a limited range of health-related goods and services that are not insured by the provinces and territories or private insurance plans.

- the legislative and administrative functions of the Nunatsiavut Government;

- construction, renovation, and repairs to housing;

- the construction and maintenance of water and sewer facilities and other community capital projects;

- programs for Inuit education;

- programs and services that support Inuit employment and business development;

- Inuit health programs and services, including the Non-Insured Health Benefits Program for First Nations and Inuit; and

- fisheries management.

3.70 Since 2005, the federal government has transferred more than $300 million to the Nunatsiavut Government to help it deliver programs and services. We found that this funding provided the Nunatsiavut Government with the means and resources to govern its internal affairs and was important for self-government. Although some of this funding was provided for housing, according to the Nunatsiavut Government, the funding has been insufficient to address the Labrador Inuit’s housing needs and a gap remains.

3.71 Toward the end of the period covered by the 2005–2010 Fiscal Financing Agreement, Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada and the Nunatsiavut Government reviewed the agreement and identified areas to address in the negotiations of the second agreement. After the review, the Nunatsiavut Government submitted a proposal to the Government of Canada for additional funding to address gaps identified during the review and enhance current programs.

3.72 The proposal drew attention to funding challenges facing the Nunatsiavut Government in relation to the Non-Insured Health Benefits Program for First Nations and Inuit, which it delivered to beneficiaries of the LILCA on Health Canada’s behalf. The Nunatsiavut Government stated that without additional financial resources, it could not provide non-insured health benefits comparable to those that First Nations and Inuit receive under the program elsewhere in Canada. Working with Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada and the Nunatsiavut Government, Health Canada provided additional funding to support the program, which addressed the Nunatsiavut Government’s concerns.

3.73 The proposal also included requests for increased funding to help the Nunatsiavut Government fulfill housing responsibilities it had assumed under the agreement. These requests included funding to develop subdivisions and build an additional 50 housing units (over five years) to help address overcrowding within Nunatsiavut’s communities. The federal government responded by indicating that there was no federal housing program for Inuit south of the 60th parallel. Consequently, no federal funding could be identified to address the housing needs of Nunatsiavut residents. This situation differs from that of the Non-Insured Health Benefits Program for First Nations and Inuit, in which a federal program and related source of funding was already in place.

3.74 We noted that the Nunatsiavut Government did receive some one-time funding for housing outside of the agreement. For example, the Nunatsiavut Government applied for and received some of the federal funding that the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation transferred to the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador to address affordable housing needs in the province. However, unlike the funding the federal government provides to First Nations directly for housing, the funding from the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation was provided to the provincial government to meet the needs of the entire province. This funding was therefore not allocated specifically for Inuit housing. Despite assuming responsibility for housing through the Fiscal Financing Agreement, the Nunatsiavut Government had to apply to the province and compete with other applicants.

3.75 To better understand the housing situation facing Nunatsiavut residents, the federal, provincial, and Nunatsiavut governments jointly funded a housing assessment for the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area in 2012. The assessment identified, among other things, problems with respect to overcrowding, housing shortages, repairs, and mould in Nunatsiavut houses. This assessment enabled the Nunatsiavut Government to better estimate the housing needs of its residents.

3.76 According to the Nunatsiavut Government, inadequate funding has affected its ability to fully carry out its responsibilities related to the construction, maintenance, and repair of housing, and from meeting housing needs in Nunatsiavut. We noted that addressing the Nunatsiavut Government’s housing concerns may involve program or policy solutions outside the LILCA.

3.77 Recommendation. Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, in cooperation with the Nunatsiavut Government, the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador, and other federal entities (such as the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation) should identify a solution to address the lack of a federal housing program for Inuit south of the 60th parallel.

Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada’s response. Agreed. Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada and other federal departments and agencies, in partnership with the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador and the Nunatsiavut Government, will examine potential solutions to address the issue of housing for the Labrador Inuit south of 60. An appropriate forum for this discussion would be the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement Implementation Committee.

Systems for monitoring the status of obligations were inadequate

3.78 We found that Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada’s system for tracking the status of obligations was not yet operating at its full potential. The Department, however, developed a plan to enhance the system to better support departments and agencies involved in implementing land claims agreements and the whole-of-government approach announced in the summer of 2015 (see paragraph 3.17).

3.79 We also found that three of the four entities we examined issued contracts for goods and services within the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area. However, this information was not tracked adequately. As a result, complete information on contracting activities within the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area was not provided to Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada as required by Treasury Board policy.

3.80 Our analysis supporting these findings presents what we examined and discusses

- monitoring the status of the implementation of obligations, and

- monitoring federal contracting activities within the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area.

3.81 Monitoring the status of the implementation of obligations. This finding matters because each department and agency is required to monitor the status of the implementation of its obligations. An appropriate monitoring system is therefore an important part of overseeing the implementation of the agreement.

3.82 Monitoring federal contracting activities within the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area. This finding matters because by monitoring contracting activities, the federal government can demonstrate that it awarded contracts within the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area. Having adequate monitoring systems also helps generate the information needed to publish complete public reports on the number and value of contracts issued, including those that provided economic benefits to the Labrador Inuit.

3.83 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 3.90 and 3.98.

3.84 What we examined. We examined the monitoring of the status of the implementation of obligations in the LILCA. We also examined the monitoring and reporting of federal contracting activities within the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area.

3.85 Monitoring the status of the implementation of obligations. As noted by Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, effective implementation of any land claims agreement is an ongoing, iterative process characterized by regular monitoring, feedback, and corrective action. Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada developed the Treaty Obligation Monitoring System (TOMS) to identify obligations and monitor implementation of land claims and self-government agreements. TOMS was intended to allow departments and agencies involved in land claims agreements to track the progress and status of the implementation of their obligations. This insight was expected to help strengthen accountability and reduce the risk of not implementing obligations.

3.86 We found that although TOMS was launched in 2010, the obligations in the system were still being validated for accuracy, consistency, and completeness. As a result, there was no assurance that the information in the system was complete or up to date. In addition, no deadline had been set for the completion of the validation process. Without validation, complete and up-to-date information on the status of the implementation of obligations was not readily available. According to department officials, a number of factors have made validation time-consuming, including

- the sheer number of obligations (the system includes more than 3,900 obligations covering all land claims and self-government agreements across Canada);

- some disagreements over the nature of obligations and who is responsible for implementing the obligations; and

- staff turnover in departments.

3.87 We noted that TOMS, as designed, included information only on the status of the implementation of obligations in land claims and self-government agreements, including the LILCA. The system was not designed to include the status of commitments in side agreements such as the Labrador Inuit Park Impacts and Benefits Agreement.

3.88 Furthermore, as designed, TOMS was unable to capture the benefits resulting from the implementation of obligations. For instance, these benefits could include how actions on obligations contribute to effective government-to-government relationships. Effective relationships, in part, are what comprehensive land claims and self-government agreements are meant to achieve.

3.89 In our opinion, focusing only on the status of obligations overlooks the importance of working collaboratively with Aboriginal groups such as the Labrador Inuit to build strong, self-reliant communities. This collaboration is especially important given that many obligations require an ongoing relationship between the Crown and the Nunatsiavut Government. We noted that toward the end of our audit, Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada developed a plan to expand the capabilities of TOMS. The enhancements are expected to allow TOMS to better support departments and agencies involved in implementing land claims agreements and the whole-of-government approach announced in the summer of 2015.

3.90 Recommendation. Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, in collaboration with other government departments and agencies, should set a firm deadline to validate obligations and complete improvements to the Treaty Obligation Monitoring System.

Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada’s response. Agreed. Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada expects that the current validation process and revised system will be in place by March 2017.

3.91 Monitoring federal contracting activities within the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area. Treasury Board policy requires government departments and agencies to collect information about federal contracting activities in areas covered by land claims agreements. This responsibility includes identifying the name of the applicable comprehensive land claim pertaining to the area in which the goods or services were delivered. This information must then be provided to Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada to compile and then disclose online through a publicly accessible database called CLCA.net, in quarterly and annual reports.

3.92 Data we obtained on contracting activities showed that, from the 2012–13 to the 2014–15 fiscal years, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Environment Canada, and Parks Canada issued contracts within the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area. During this time frame, Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada did not award any contracts within this area.

3.93 While the three entities had records on contracting activities, including activities within the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area, information was incomplete and inaccurate. We found that this was due to varying staff awareness regarding contracting policy requirements, and limitations in the way systems and processes were used to track contracting activities.

3.94 We found that in some cases, systems and processes were designed to capture contracting activities within areas covered by land claims agreements, including the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area. However, staff responsible for managing contracts did not consistently use these systems and processes to properly capture the required information. Furthermore, some entities used the contractors’ addresses to determine whether goods or services were delivered within the settlement area. However, Treasury Board policy states that it is the location in which the goods or services were delivered that determines whether the contracting activity was applicable to the settlement area.

3.95 Entity officials acknowledged that there could be improvements in recording and reporting information on contracting activities. Though some entities regularly reviewed and manually corrected their information before sending it to Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada for public reporting, we found that incomplete information was still sent, resulting in incomplete public reporting.

3.96 Although these entities had issued contracts within the settlement area, not all contracts appeared in the CLCA.net database. For example, for the 2014–15 fiscal year, the database listed only two contracts, both worth $1,000 and both issued in the settlement area by an entity outside the scope of our audit. However, based on our review of documentation provided by the entities in the scope of our audit, the $2,000 significantly understated the value of contracts issued in the settlement area for the 2014–15 fiscal year. In that fiscal year, Parks Canada alone issued approximately $960,000 in contracts for goods and services to support its management of the Torngat Mountains National Park of Canada.

3.97 In our opinion, while the Labrador Inuit benefited from economic opportunities associated with federal contracts, contract information was not adequately tracked. Further, public reporting on contracting activities within the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area was not complete.

3.98 Recommendation. Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Parks Canada, and Environment Canada should ensure that data related to contracts for goods and services within the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area is accurate and complete. These entities should also provide this information to Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada regularly for reporting through the publicly accessible CLCA.net database.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response. Agreed. Fisheries and Oceans Canada will continue to communicate proper procedures and processes and educate staff on entering contracts within the departmental financial management reporting system to ensure that the data captured for contracting activities within areas covered by land claims agreements, including the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement, is accurate and complete. Fisheries and Oceans Canada will also look into strengthening its processes related to the reporting of comprehensive land claims agreement data and continue to provide Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada with this data on a regular basis. To be implemented immediately.

Parks Canada’s response. Agreed. Parks Canada (the Agency) reports comprehensive land claims agreement contracting activities to Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada on a quarterly basis in accordance with Treasury Board policy. The Agency is aware of the importance of accurate data when reporting on procurement in comprehensive land claims agreement areas. The Agency will review its business processes and training approaches for its procurement officers by March 2016 to ensure awareness of comprehensive land claims agreement obligations in general and system requirements for recording and monitoring contracting in such areas.

Environment Canada’s response. Agreed. Environment Canada is aware of the importance of accurate data when reporting on procurement within all comprehensive land claims agreement areas. Environment Canada will review its business processes and increase awareness of the comprehensive land claims agreement obligations in general. Environment Canada is committed to reporting the data to Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada on a quarterly basis.

Conclusion

3.99 We concluded that federal government entities made progress implementing selected obligations in the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement and two related side agreements, the Fiscal Financing Agreement and the Labrador Inuit Park Impacts and Benefits Agreement. However, there are challenges that need to be resolved. By providing direction and guidance, the Deputy Ministers’ Oversight Committee announced in July 2015 by the Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development could help with some of the challenges experienced when implementing land claims agreement obligations.

About the Audit

The Office of the Auditor General’s responsibility was to conduct an independent examination of the implementation of the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement (LILCA) to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs.

All of the audit work in this report was conducted in accordance with the standards for assurance engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance. While the Office adopts these standards as the minimum requirement for our audits, we also draw upon the standards and practices of other disciplines.

As part of our regular audit process, we obtained management’s confirmation that the findings in this report are factually based.

Objective

The audit objective was to determine whether federal government entities implemented selected obligations as defined in the LILCA and related side agreements.

The two related side agreements include the Fiscal Financing Agreement and the Labrador Inuit Park Impacts and Benefits Agreement.

Scope and approach

The following entities were included in the audit:

- Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada,

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada,

- Parks Canada, and

- Environment Canada.

The audit focused on the following chapters of the LILCA and related obligations:

- Chapter 7—Economic Development, including contracting in the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area. We examined whether contracts were issued in the settlement area including to Inuit businesses and whether the information was provided to Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada for inclusion in the database on federal contracting activities in comprehensive land claims areas (CLCA.net) according to the Treasury Board’s Contracting Policy. The audit did not examine the contracting process itself or decisions pertaining to individual contracts or the provisions in the LILCA pertaining to employment with the federal government. Employment was considered as part of our examination related to Chapter 9 (see below).

- Chapter 9—National Parks and Protected Areas, including commitments in the Labrador Inuit Park Impacts and Benefits Agreement related to hiring practices and Inuit career training opportunities, economic benefits and opportunities, and archaeological and Inuit cultural materials.

- Chapter 13—Fisheries, including obligations related to commercial harvesting of shrimp and obligations related to communal harvesting of fish outside the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area.

- Chapter 18—Fiscal Financing Agreements, including factors considered in negotiating the 2012–2017 Fiscal Financing Agreement.

We did not examine federal obligations related to oceans management, environmental assessment, wildlife harvesting (including polar bears and migratory birds), and federal appointments to the various boards established under the LILCA, such as the Torngat Joint Fisheries Board, the Torngat Mountains National Park Cooperative Management Board, and the Dispute Resolution Board. We also did not examine obligations that were the responsibility of the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador or the Nunatsiavut Government.

In addition to the implementation of selected obligations, the audit also examined whether Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Parks Canada, and Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada monitored the status of their obligations and whether this information was shared with Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada to allow it to coordinate and report on the implementation of the LILCA.

In conducting the audit, we met with officials from departments and agencies, officials from the Nunatsiavut Government, and third-party stakeholders. We also reviewed documentation and files related to the subject areas we examined.

Criteria

To determine whether federal government entities implemented selected obligations as defined in the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement and related side agreements (the Fiscal Financing Agreement and the Labrador Inuit Park Impacts and Benefits Agreement), we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Each federal organization has acted upon its contracting obligations as defined in the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement. |

|

|

Each federal organization is monitoring the status of its contracting activities. Each federal organization is sharing its contracting information with Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada. |

|

|

Parks Canada has acted upon its commitments as defined in the Park Impacts and Benefits Agreement. |

|

|

Parks Canada is monitoring the status of its commitments. |

|

|

Parks Canada is sharing the status of its commitments with Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada. |

|

|

Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada has acted upon its obligations as defined under fiscal financing agreements in the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement. |

|

|

Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada is monitoring the status of its obligations as defined under fiscal financing agreements in the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement. |

|

|

Fisheries and Oceans Canada has acted upon its obligations as defined in the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement. |

|

|

Fisheries and Oceans Canada is monitoring the status of its obligations. |

|

|

Fisheries and Oceans Canada is sharing the status of its obligations with Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada. |

|

Management reviewed and accepted the suitability of the criteria used in the audit.

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period between 1 January 2012 and 31 March 2015. For specific work related to fisheries obligations, the team requested information from 1 January 2006 to 31 March 2015. Audit work for this report was completed on 10 September 2015.

Audit team

Assistant Auditor General: Jerome Berthelette

Principal: James McKenzie

Director: Marianne Avarello

Alexandre Boucher

Sophie Chen

Makeddah John

Sophia Khan

Élyse Maisonneuve

List of Recommendations

The following is a list of recommendations found in this report. The number in front of the recommendation indicates the paragraph where it appears in the report. The numbers in parentheses indicate the paragraphs where the topic is discussed.

Implementing obligations in the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

3.57 Fisheries and Oceans Canada should work with the Nunatsiavut Government to clarify and agree on the intent of the obligations regarding the Nunatsiavut Government’s access to the northern shrimp fishery. They should also agree on what constitutes changes to the system for allocating commercial opportunities to fish. If the differences remain unresolved, the matter should be brought to the Dispute Resolution Board as provided for in the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement. (3.28–3.56) |

Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response. Agreed. Fisheries and Oceans Canada is willing to work with the Nunatsiavut Government to clarify the intent of the obligations around the shrimp fishery, including defining what constitutes changes to the system. Failing that, Fisheries and Oceans Canada would agree to mechanisms under the Dispute Resolution chapter of the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement while ensuring that the Minister’s discretion under the Fisheries Act is not fettered. Timelines for implementing this recommendation will be discussed with the Nunatsiavut Government as part of our ongoing discussions on fisheries related issues. |

|

3.58 Fisheries and Oceans Canada should work with the Nunatsiavut Government to agree on the status of the obligation regarding communal harvesting in the Upper Lake Melville area. If the differences remain unresolved, the matter should be brought to the Dispute Resolution Board as provided for in the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement. (3.28–3.56) |

Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response. Agreed. Fisheries and Oceans Canada is willing to participate with the Nunatsiavut Government to clarify and explain our position on this matter. If agreement cannot be reached with the Nunatsiavut Government on the status of the obligation regarding communal harvesting in Upper Lake Melville, Fisheries and Oceans Canada would agree to mechanisms under the Dispute Resolution chapter of the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement, while ensuring that the Minister’s discretion under the Fisheries Act is not fettered. Timelines for implementing this recommendation will be discussed with the Nunatsiavut Government as part of our ongoing discussions on fisheries related issues. |

|

3.68 Parks Canada should finalize, with the Nunatsiavut Government, the memorandum of understanding on the presentation, management, and safekeeping of archaeological material found in the Torngat Mountains National Park of Canada. (3.59–3.67) |

Parks Canada’s response. Agreed. Currently, Parks Canada and the Nunatsiavut Government are conducting respective legal reviews of the penultimate draft of the memorandum of understanding on the presentation, management, and safekeeping of archaeological materials in the Torngat Mountains National Park of Canada, with the shared intention to sign the memorandum in the fall of 2015 or as soon as possible, once the legal reviews are complete and the memorandum has been finalized. |

|

3.77 Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, in cooperation with the Nunatsiavut Government, the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador, and other federal entities (such as the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation) should identify a solution to address the lack of a federal housing program for Inuit south of the 60th parallel. (3.69–3.76) |

Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada’s response. Agreed. Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada and other federal departments and agencies, in partnership with the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador and the Nunatsiavut Government, will examine potential solutions to address the issue of housing for the Labrador Inuit south of 60. An appropriate forum for this discussion would be the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement Implementation Committee. |

|

3.90 Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, in collaboration with other government departments and agencies, should set a firm deadline to validate obligations and complete improvements to the Treaty Obligation Monitoring System. (3.78–3.89) |

Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada’s response. Agreed. Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada expects that the current validation process and revised system will be in place by March 2017. |

|

3.98 Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Parks Canada, and Environment Canada should ensure that data related to contracts for goods and services within the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area is accurate and complete. These entities should also provide this information to Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada regularly for reporting through the publicly accessible CLCA.net database. (3.91–3.97) |

Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response. Agreed. Fisheries and Oceans Canada will continue to communicate proper procedures and processes and educate staff on entering contracts within the departmental financial management reporting system to ensure that the data captured for contracting activities within areas covered by land claims agreements, including the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement, is accurate and complete. Fisheries and Oceans Canada will also look into strengthening its processes related to the reporting of comprehensive land claims agreement data and continue to provide Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada with this data on a regular basis. To be implemented immediately. Parks Canada’s response. Agreed. Parks Canada (the Agency) reports comprehensive land claims agreement contracting activities to Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada on a quarterly basis in accordance with Treasury Board policy. The Agency is aware of the importance of accurate data when reporting on procurement in comprehensive land claims agreement areas. The Agency will review its business processes and training approaches for its procurement officers by March 2016 to ensure awareness of comprehensive land claims agreement obligations in general and system requirements for recording and monitoring contracting in such areas. Environment Canada’s response. Agreed. Environment Canada is aware of the importance of accurate data when reporting on procurement within all comprehensive land claims agreement areas. Environment Canada will review its business processes and increase awareness of the comprehensive land claims agreement obligations in general. Environment Canada is committed to reporting the data to Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada on a quarterly basis. |

PDF Versions

To access the Portable Document Format (PDF) version you must have a PDF reader installed. If you do not already have such a reader, there are numerous PDF readers available for free download or for purchase on the Internet: