2018 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada Independent Auditor’s ReportReport 1—Building and Implementing the Phoenix Pay System

2018 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of CanadaReport 1—Building and Implementing the Phoenix Pay System

Independent Auditor’s Report

Introduction

Background

1.1 In 2009, the Government of Canada started an initiative to replace the 40-year-old system it used to pay 290,000 employees in 101 departments and agencies. This Transformation of Pay Administration Initiative would also centralize pay services for nearly half of the departments and agencies, which had previously processed pay for their own employees. The initiative’s goal was to decrease the costs of and improve the efficiency of processing the government’s payroll, which is about $22 billion a year.

1.2 Public Services and Procurement Canada was responsible for this initiative. The Department undertook two projects to support the initiative. One was to centralize pay operations for 46 departments and agencies in a new Public Service Pay Centre in Miramichi, New Brunswick. The second was to switch to a new pay software for all departments and agencies. The initiative took seven years to complete and had a budget of $310 million, including $155 million to build and implement the new pay software.

1.3 The government expected the initiative to save it about $70 million a year, starting in the 2016–17 fiscal year. These savings were largely to be achieved through

- eliminating about 1,200 positions in departments and agencies for pay advisors—specialists who process pay, advise employees, and correct errors—which were replaced by 550 positions, including 460 pay advisors, at the Miramichi Pay Centre;

- automating many pay processes that were manual under the old system, using new software; and

- eliminating duplicate data entry and processing by integrating pay operations with the Government of Canada’s approved human resource management system.

1.4 Public Services and Procurement Canada centralized the pay advisors for 46 departments and agencies between May 2012 and early 2016. The remaining 55 departments and agencies kept their approximately 800 pay advisors to process pay for their own employees.

1.5 In June 2011, after a public competition, Public Services and Procurement Canada awarded a contract to International Business Machines CorporationIBM to help it design, customize, integrate, and implement new software to replace the government’s old pay system. The Department chose a PeopleSoft commercial pay software, which was to be customized to meet the government’s needs. The Department called this system Phoenix.

1.6 Development of Phoenix began in December 2012 and was implemented in two waves. The first wave included 34 departments and agencies on 24 February 2016, and the second wave included the remaining 67 departments and agencies on 21 April 2016.

1.7 In our fall 2017 audit of Phoenix pay problems, we found that the system had problems immediately after it was put in place and that they continued to grow. Departments and agencies have struggled to pay their employees accurately and on time. In that audit, we found that as of 30 June 2017, there was over $520 million in pay outstanding due to errors for public servants serviced by Phoenix who were paid too much or too little. We calculated that about 51% of employees had errors in their paycheques issued on 19 April 2017, compared with 30% in the pay issued on 6 April 2016. We found that the number of outstanding pay requests—such as a request to make a change to an employee’s pay because of a promotion or to fix an error—had continued to grow to over 494,500 by June 2017.

1.8 Public Services and Procurement Canada. Public Services and Procurement Canada administers the pay of public service employees. It led the development of the Phoenix pay system and is responsible for operating and maintaining the system and providing instructions to Phoenix users. It is also responsible for operating the Miramichi Pay Centre. At the Pay Centre, pay advisors use Phoenix to initiate, change, or terminate employees’ pay by directly inputting information based on requests received from the 46 departments and agencies that rely on the Pay Centre. The other 55 departments and agencies do not use the Pay Centre and are responsible for inputting pay information in Phoenix for their employees.

1.9 Three executives at Public Services and Procurement Canada (Phoenix executives) were responsible for delivering the Phoenix pay system. The Deputy Minister of the Department was responsible for ensuring that a governance and oversight mechanism to manage the project was in place, documented, and maintained, and that the project was managed according to its complexity and risk. During the seven years it took to develop Phoenix, up to and including its first wave, three different people served as Deputy Minister.

1.10 Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat supports the Treasury Board as the public service employer. The Treasury Board determines and regulates pay, hours of work, and other terms and conditions of employment. The Secretariat provides departments with direction and guidance on how to implement Treasury Board pay policies. The Secretariat also promotes government-wide sharing of information and best practices on pay and provides documented business processes for human resources.

1.11 Departments and agencies. Departments and agencies are responsible for ensuring that their human resource systems and processes are compatible and integrated with Phoenix. They must ensure that the information needed to pay employees is entered on time and accurately into Phoenix. Departments and agencies must also review and authorize pay to be issued to employees.

1.12 All departments and agencies, including Public Services and Procurement Canada and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, have a shared accountability to pay employees. They must comply with federal employees’ terms and conditions of employment, which include paying employees accurately within a specific time.

1.13 According to Public Services and Procurement Canada, a pay processing system is just one part of a complex process that includes many stakeholders. The Department states that a pay system needs to support a variety of human resource systems and processes that handle numerous pay-related tasks, such as

- hiring employees,

- managing vacations and other leaves,

- managing benefits such as dental care, and

- paying employees who are retiring or terminated.

Considering the broad intricacies and scope of these processes and systems, the Transformation of Pay Administration Initiative has been a large and complex undertaking with substantial risks. Developing and implementing the Phoenix pay system have been an essential and critical part of the initiative.

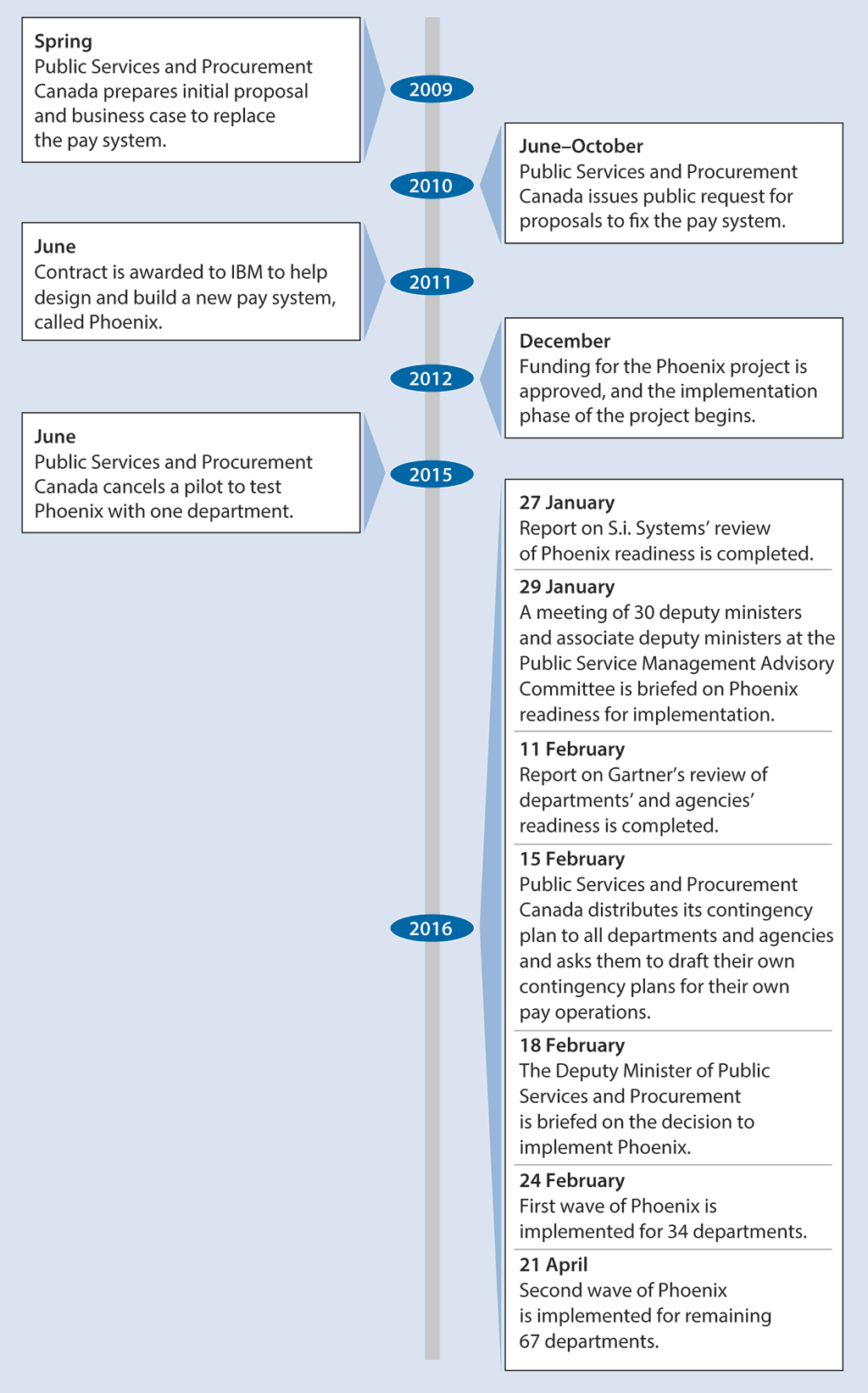

1.14 Exhibit 1.1 shows the key milestones of the Phoenix project.

Exhibit 1.1—Timeline of key Phoenix milestones

Exhibit 1.1—text version

This timeline shows key Phoenix milestones, from 2009 to 2016.

In spring 2009, Public Services and Procurement Canada prepares initial proposal and business case to replace the pay system.

From June 2010 to October 2010, Public Services and Procurement Canada issues public request for proposals to fix the pay system.

In June 2011, a contract is awarded to IBM to help design and build a new pay system, called Phoenix.

In December 2012, funding for the Phoenix project is approved, and the implementation phase of the project begins.

In June 2015, Public Services and Procurement Canada cancels a pilot to test Phoenix with one department.

In 2016, there are the following seven milestones:

- On 27 January, a report on S.i. Systems’ review of Phoenix readiness is completed.

- On 29 January, a meeting of 30 deputy ministers and associate deputy ministers at the Public Service Management Advisory Committee is briefed on Phoenix readiness for implementation.

- On 11 February, a report on Gartner’s review of departments’ and agencies’ readiness is completed.

- On 15 February, Public Services and Procurement Canada distributes its contingency plan to all departments and agencies and asks them to draft their own contingency plans for their own pay operations.

- On 18 February, the Deputy Minister of Public Services and Procurement is briefed on the decision to implement Phoenix.

- On 24 February, the first wave of Phoenix is implemented for 34 departments.

- On 21 April, the second wave of Phoenix is implemented for the remaining 67 departments.

Focus of the audit

1.15 This audit focused on whether Public Services and Procurement Canada effectively and efficiently managed and oversaw the implementation of the new Phoenix pay system. The audit focused on the Department as the lead organization for building and implementing the system and for operating centralized pay operations for 46 departments and agencies in the Public Service Pay Centre in Miramichi, New Brunswick. The system is a critical part of the Transformation of Pay Administration Initiative.

1.16 We wanted to know whether the decision to implement the system was reasonable and considered selected aspects of standard management practices for system development. We examined whether the system was fully tested, would deliver the functions needed to pay federal employees, was secure, and would protect employees’ private information. We also examined whether Public Services and Procurement Canada adequately supported selected departments and agencies in their move to Phoenix.

1.17 The nine departments and agencies included in the audit were

- the Canadian Security Intelligence Service,

- Correctional Service Canada,

- Employment and Social Development Canada,

- National Defence,

- Natural Resources Canada,

- Public Services and Procurement Canada,

- the Royal Canadian Mounted Police,

- Statistics Canada, and

- the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

1.18 This audit is important because the Phoenix pay system is less efficient and less cost-effective than the old system, and thousands of employees have not been accurately paid or paid on time. In our fall 2017 audit of Phoenix pay problems, we found that the problems were having serious financial impacts on the federal government and its employees. In that audit, we estimated that it will take many millions of dollars and years to fix the Phoenix pay problems. It is important that the government learn from the mistakes made in the Phoenix project in order to properly manage future large information technology projects.

1.19 We did not examine events leading to the centralization of pay advisors or the events after Phoenix was implemented.

1.20 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Managing the development of Phoenix

Overall message

1.21 Overall, we found that Public Services and Procurement Canada failed to properly manage the Phoenix project. Because of the Department’s poor management, Phoenix was implemented

- without critical pay processing functions;

- without having been fully tested to see whether it would operate as expected;

- with significant security weaknesses, which meant that the system did not protect public servants’ private information;

- without an adequate contingency plan in case the system had serious and systemic problems after it was implemented; and

- without any plans to upgrade the underlying software application after it was no longer supported.

1.22 Furthermore, we found that Public Services and Procurement Canada did not fully consult and involve other departments and agencies during the development of Phoenix to determine what they needed Phoenix to do or to adequately help them move to the new system. The Department did not completely and properly test Phoenix before its implementation, which is contrary to recognized practices for developing a system. Phoenix executives cancelled a pilot project with one department that would have assessed whether Phoenix was ready to be used government-wide.

1.23 These findings matter because the Phoenix pay system failed to meet the needs of users and improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the government’s pay processes. The project mismanagement resulted in

- the system’s failing to correctly pay tens of thousands of federal employees on time,

- government departments and agencies spending a significant amount of time and money trying to resolve Phoenix pay problems, and

- a system that so far has been less efficient and more costly than the 40-year-old system it replaced.

1.24 The building and implementation of Phoenix was an incomprehensible failure of project management and oversight.

Public Services and Procurement Canada failed to properly manage the Phoenix project

1.25 We found that Public Services and Procurement Canada failed to properly manage the Phoenix pay system project. The Department did not fully test or pilot the system before implementation. When faced with possible higher costs, the Department removed or deferred important system functions. All of this created many risks—which the Department knew about—that the system would not be able to process pay accurately or keep employee information secure. The Department chose to not go back to the Treasury Board either to ask it for more money so that the project could be delivered as planned or to inform it about the Department’s decision to remove or defer some functions and the impact that could have on the expected benefits and savings.

1.26 Furthermore, the Department had no plans to upgrade the PeopleSoft application on which Phoenix was built, despite the application’s need for regular upgrades.

1.27 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

- Functions needed to process pay

- Testing Phoenix

- Security, privacy protection, and accessibility requirements

- Software upgrade

- Contingency plan

1.28 This finding matters because the project was expected to deliver a secure system that meets the needs of the Government of Canada for processing pay for its employees.

1.29 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 1.48.

1.30 What we examined. We examined whether Public Services and Procurement Canada adequately managed the building of the Phoenix pay system. We examined whether the Department

- ensured that Phoenix had all the functions needed to process pay;

- ensured that Phoenix met government security, privacy protection, and accessibility requirements;

- planned for future upgrades of Phoenix; and

- had a contingency plan in case Phoenix had major problems after implementation.

1.31 Functions needed to process pay. We found that before implementing Phoenix, Phoenix executives did not ensure that it could properly process pay. When the system was put in place, it could not perform some critical pay functions, such as processing requests for retroactive pay. The Department knew about many of these critical weaknesses before implementing the Phoenix system. In our opinion, these weaknesses were serious enough that the system should not have been implemented. Other weaknesses were discovered by Public Services and Procurement Canada or other departments and agencies only after they started using Phoenix. Testing and piloting should have taken place to confirm the weaknesses, to determine whether there were more, and to fix or mitigate them.

1.32 Large information technology projects require balancing cost, schedule, and scope. We found that Phoenix executives scaled back the project’s functions to save money or time. In the spring of 2012, after the planning phase of Phoenix, IBM told Public Services and Procurement Canada that Phoenix would cost $274 million to build and implement. The Treasury Board had approved a Phoenix building and implementation budget of $155 million in 2009. We found that Public Services and Procurement Canada did not consider asking the Treasury Board for more money to build and implement Phoenix. Instead, Phoenix executives decided to work with IBM to find ways to reduce the scope of work to fit the approved budget. As a result, Phoenix executives decided to

- remove some pay processing functions,

- not test some pay processing functions,

- shorten the project schedule by compressing the time between the two waves of Phoenix from seven months to two months, and

- reduce the number of IBM and Public Services and Procurement Canada employees assigned to the development and implementation of Phoenix.

1.33 We found that overall, Phoenix executives decided to defer or remove more than 100 important pay processing functions, including the ability to

- process requests for retroactive pay, such as acting pay, which is provided to an employee acting in a temporary role for a superior;

- notify employees by email of actions required on their part to process pay requests; and

- automatically calculate certain types of pay, such as increases in pay for acting appointments.

1.34 Phoenix executives planned for these important functions to be added to Phoenix only after all 101 departments and agencies had been transferred to it.

1.35 Phoenix executives did not re-examine the system’s expected benefits after they decided to significantly scale back what Phoenix would do. They should have known that such a significant change in the project scope could put the system’s functionality and projected savings at risk and undermine the government’s ability to pay its employees the right amount at the right time.

1.36 Testing Phoenix. We found that Public Services and Procurement Canada could not show that the Phoenix functions that had been approved as part of the February and April 2016 implementations were in place by those dates and were fully tested before implementation. The Department had identified 984 functions that it needed to include in the February and April 2016 implementations so that pay advisors could process pay. We reviewed 111 of them. We found that 30 of these 111 functions were not part of Phoenix when departments and agencies started to use it—the functions had been either removed or deferred. The decisions to remove or defer some of these functions, such as the processing of retroactive pay, led to increases in outstanding pay requests and pay errors.

1.37 For the remaining 81 functions we reviewed, we found that 20% did not pass testing by Public Services and Procurement Canada before implementation. The Department did not retest the functions that failed the original testing.

1.38 We also found that Public Services and Procurement Canada did not test Phoenix as a whole system before implementation and did not know whether it would operate as intended. For example, the Department did not complete the final testing of Phoenix by pay advisors.

1.39 To assess whether Phoenix was ready government-wide, Public Services and Procurement Canada had planned to conduct a pilot implementation with one department. A pilot would have allowed the Department to determine if the system would work in a real setting without affecting pay that was still being processed by the old pay system.

1.40 However, we found that in June 2015, Phoenix executives cancelled the pilot because of major defects that affected critical functions and outstanding problems with system stability, and they did not have enough time to reschedule the pilot without delaying Phoenix implementation. They decided that rather than delaying Phoenix, there would be no pilot. Public Services and Procurement Canada did not assess the impacts of cancelling the pilot. This pilot was the Department’s chance to test a final, live version of Phoenix before implementation. The pilot could have allowed the Department to detect problems that would have shown that the system was not ready.

1.41 Security, privacy protection, and accessibility requirements. The Phoenix pay system was expected to comply with Government of Canada policies for security, privacy protection, and accessibility. We found that Phoenix executives implemented Phoenix even though it did not comply with these policies.

1.42 We found that the Department implemented Phoenix despite knowing about high security risks, which it did not expect to address until December 2016—months after the planned implementation. These risks included the risk of someone gaining unauthorized access to information.

1.43 We also found that Phoenix did not meet government policy requirements to protect personal information. The Treasury Board Policy on Privacy Protection aims to prevent, for example, managers from accessing personal files of employees outside of their responsibility. Public Services and Procurement Canada conducted a preliminary privacy impact assessment of the planned system in March 2012. The assessment was to identify potential privacy risks with Phoenix and recommend ways to mitigate the risks. This preliminary assessment identified four high privacy risks and six moderate risks. The Department did not complete a final privacy impact assessment before implementing Phoenix. The Privacy Commissioner of Canada has reported numerous privacy breaches of federal employees’ information in Phoenix after it was put in place.

1.44 We also found that Phoenix was not fully accessible to federal employees with disabilities or other impediments. We found that Phoenix executives decided in July 2013 to remove any obligations for IBM to customize the software that would have provided such accessibility. After Phoenix was put in place, federal employees with disabilities or other impediments reported difficulties reading Phoenix information. In May 2017, Public Services and Procurement Canada told us that after it had stabilized Phoenix pay problems, it would improve accessibility. However, the Department did not provide any timelines.

1.45 Software upgrade. A standard management practice in information technology projects is to plan for future software upgrades. We found that when building Phoenix, Public Services and Procurement Canada did not plan for future upgrades to PeopleSoft, the software application on which Phoenix was built. The Oracle Corporation, the owner of PeopleSoft, was expected to stop supporting the version used by Phoenix in 2018. Although the Department informed us that it had secured a one-year extension to its maintenance contract with the Oracle Corporation, not planning to upgrade is a significant omission that puts the system’s long-term viability at risk. Upgrading a system’s underlying software application is complex and must be well planned, especially when many customizations need to be upgraded, as with Phoenix. If the Department does not keep the underlying software up to date, it will have to maintain it on its own.

1.46 Contingency plan. Public Services and Procurement Canada finalized a limited contingency plan for Phoenix less than two weeks before its implementation in February 2016. We found that the plan mostly outlined what to do if Phoenix failed to operate; the plan did not anticipate scenarios with system or process problems, such as the ones that occurred after implementation. We found that all but one of the plan’s scenarios called for Phoenix to continue operating while the problems were being resolved. The plan did not explain how problems would be resolved, what specific tasks would be needed to carry out the contingency plan, and who would be responsible for these tasks. We also found that the Department did not test its contingency plan to see whether it would work.

1.47 We also found that Public Services and Procurement Canada did not help departments and agencies prepare their individual contingency plans in case Phoenix did not work as planned. Less than a week before the February 2016 implementation of Phoenix, Public Services and Procurement Canada sent its contingency plan to departments and agencies and asked them to develop their own contingency plans using a template. Public Services and Procurement Canada did not give them any guidance or enough time to develop their contingency plans.

1.48 Recommendation. For government-wide information technology projects under its responsibility, Public Services and Procurement Canada should ensure the following:

- Its project managers understand and communicate to concerned stakeholders the impacts of any changes to functionality, including any impacts of the cumulative effect of all changes.

- The project complies with relevant legislative and policy requirements.

- The project includes plans for keeping the software current.

- The project includes a complete contingency plan.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Moving forward, Public Services and Procurement Canada will ensure that, for all government-wide information technology (IT) projects under its responsibility, it will seek appropriate authorities to define and assign roles and responsibilities of concerned stakeholders. This will permit the Department to measure and report on collective efforts with regard to project management and to ensure that implicated partners and stakeholders participate in, and support the assessment of, the cumulative impacts of key decisions and risk mitigations, including changes to functionality.

The Department’s National Project Management System requires compliance with legal and policy requirements related to project management. The Department will ensure that project managers understand and respect these requirements. It will also ensure that project managers understand well the requirements for preparing a stakeholder engagement plan, a formal software upgrade plan, and a comprehensive contingency plan that covers government-wide systems, processes, and impacts for all government-wide IT projects under its responsibility.

The Department will integrate the lessons learned from Phoenix into project management practices and training and will support government-wide efforts to strengthen the capacity of the project management community.

Public Services and Procurement Canada did not fully engage departments and agencies in building Phoenix and in preparing them to use it

1.49 We found that Public Services and Procurement Canada did not fully engage departments and agencies during the development of Phoenix. The Department did not seek their extensive experience and knowledge in processing complex pay requests, which would have helped the Department to develop Phoenix to meet their needs. We also found that Public Services and Procurement Canada did not help other departments and agencies fully understand what they would need to do to use Phoenix. The Department also did not provide relevant and timely training to support the transition to Phoenix.

1.50 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

- Engaging departments and agencies in building Phoenix

- Supporting departments and agencies in preparing to move to Phoenix

1.51 This finding matters because Phoenix required changes to the way departments and agencies processed pay. It also required that departments and agencies have the tools and training needed to use Phoenix.

1.52 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 1.61.

1.53 What we examined. We examined whether Public Services and Procurement Canada adequately engaged client departments and agencies in building Phoenix and helped them move to the new system. The seven client departments and agencies we included in our audit were

- the Canadian Security Intelligence Service,

- Correctional Service Canada,

- Employment and Social Development Canada,

- National Defence,

- Natural Resources Canada,

- the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and

- Statistics Canada.

1.54 Engaging departments and agencies in building Phoenix. We found that Public Services and Procurement Canada did not effectively engage the seven client departments and agencies we included in our audit to identify what they needed Phoenix to do to process pay. Public Services and Procurement Canada did not share a complete list of functions with departments and agencies and did not give them a chance to review or approve the functions to confirm that the system met their needs.

1.55 Public Services and Procurement Canada asked only six departments and agencies, including four of the client departments and agencies in our audit, to participate in the final pay advisor testing of Phoenix. We found the following:

- Public Services and Procurement Canada gave these six departments and agencies vague instructions and guidance on how their pay advisors should perform final testing of Phoenix.

- In some cases, departments and agencies disagreed with Public Services and Procurement Canada on testing results.

The four departments and agencies told us that the recording of testing results was subjective and inconsistent, and the criteria for passing or failing a test were not clear.

1.56 We also found that Public Services and Procurement Canada did not share information on outstanding Phoenix security and privacy risks with most departments and agencies, because it considered the information either too sensitive or incomplete. Departments and agencies therefore could not understand and comment on the extent of security and privacy risks that remained when Phoenix was put in place, including risks that could affect their human resource data or risks they could help to mitigate.

1.57 The seven client departments and agencies in our audit told us that in general, they received communications from Public Services and Procurement Canada that were not complete or timely throughout most of the Phoenix development. They said that they did not receive enough information to meaningfully help build Phoenix or move to the new system.

1.58 Supporting departments and agencies in preparing to move to Phoenix. Phoenix required significant changes to the way pay would be processed in all departments and agencies using the system. We found that Public Services and Procurement Canada did not adequately prepare departments and agencies for these changes. For example, Public Services and Procurement Canada gave descriptions of modified pay processes to be implemented by departments and agencies using the system. We found that these descriptions

- were ambiguous and did not sufficiently and explicitly detail what was required from employees and managers,

- did not provide guidance on how the modified pay processes should integrate into the pay operations of specific departments or agencies, and

- were provided too late to be implemented.

1.59 Public Services and Procurement Canada analyzed departments’ and agencies’ training needs for the Phoenix pay system. It also developed a training plan and curriculum and procedures manuals for the new pay system. However, officials from the departments and agencies in our audit told us that employees received inadequate training on Phoenix. We found that the content and procedures were generic, incomplete, and used classroom or web-based presentations instead of a demonstration version of the Phoenix software. Pay advisors from two of the departments and agencies included in this audit were surveyed as part of our fall 2017 audit of Phoenix pay problems. Most pay advisors we surveyed in these two departments and agencies reported that they were dissatisfied with the training they received.

1.60 As stated in paragraph 1.32, Public Services and Procurement Canada reduced the scope of the work so that the work could be done within the approved Phoenix project budget. As a result, fewer IBM and Public Services and Procurement Canada employees were assigned to help departments and agencies move to Phoenix.

1.61 Recommendation. For government-wide projects under its responsibility, Public Services and Procurement Canada should

- ensure that requirements to move to a new system are defined and implemented with the active participation of all concerned departments and agencies, and

- ensure that all concerned departments and agencies are consulted and actively participate in the project’s design and testing.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Moving forward, Public Services and Procurement Canada will ensure that for all government-wide information technology projects under its responsibility, it seeks authority to do the following:

- Clearly define, in consultation with concerned departments and agencies, the roles and responsibilities of Public Services and Procurement Canada as the lead organization and of concerned departments and agencies, as well as of the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. Such authorities will ensure active participation and collaboration of concerned departments and agencies and the Secretariat in defining business requirements and designing and testing any new system. Such authorities will also ensure implementation of requirements related to change management, departmental readiness, data quality, and revised business and technical processes and controls.

- Develop a performance measurement framework that measures the effective discharge of the assigned roles and responsibilities of the lead organization, concerned departments and agencies, and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

- Independently validate the performance of the lead organization, concerned departments and agencies, and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, and report the results of performance to a government-wide deputy head oversight committee.

- In accordance with established authorities, in conjunction with the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, take appropriate action where performance is lacking.

Deciding to implement Phoenix

Overall message

1.62 Overall, we found that there was no oversight of the Phoenix project, which allowed Phoenix executives to implement the system even though they knew it had significant problems. There were no oversight bodies independent of the project management structure to provide independent advice to the Deputy Minister of Public Services and Procurement on the project status. This meant that the Deputy Minister did not receive independent information showing that Phoenix was not ready to be implemented or that the Miramichi Pay Centre and departments and agencies were not ready for Phoenix. Phoenix executives were more focused on meeting the project budget and timeline than on what the system needed to do.

Phoenix executives did not understand the importance of warnings that the Miramichi Pay Centre, users, and the new system were not ready

1.63 We found that before implementing Phoenix, Phoenix executives did not heed clear warnings that the Miramichi Pay Centre, departments and agencies, and the pay system itself were not ready. It was obvious even before Phoenix was in place that pay advisors in Miramichi were not handling the volume of files that the Department expected. Furthermore, several departments and agencies, along with third-party assessments, identified significant problems with the system. Phoenix executives did not understand the importance of these warnings and went ahead with implementing Phoenix.

1.64 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

- Review of Miramichi Pay Centre readiness

- Review of departments’ and agencies’ readiness

- Review of Phoenix pay system readiness

1.65 This finding matters because there were several missed opportunities to consider the Phoenix pay system’s readiness and everyone’s readiness for Phoenix. If readiness had been considered, Public Services and Procurement Canada might have been able to take corrective actions as required.

1.66 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 1.83.

1.67 What we examined. We examined whether Phoenix executives assessed the readiness of the Miramichi Pay Centre, departments and agencies, and the pay system itself before implementing Phoenix in February 2016. We examined whether Phoenix executives used sound and independent advice and responded appropriately.

1.68 Review of Miramichi Pay Centre readiness. We found that Public Services and Procurement Canada vastly overestimated the Miramichi Pay Centre’s capacity and readiness to handle employee pay files before and after Phoenix was implemented.

1.69 When it sought approval from the Treasury Board for the Phoenix project and its budget, Public Services and Procurement Canada said that it could increase the efficiency of pay advisors through centralization in the Miramichi Pay Centre and through Phoenix. Before Phoenix, each pay advisor in departments and agencies handled on average 184 employee pay files. Public Services and Procurement Canada expected this number would rise to 200 employee pay files after centralization and then at least double to 400 employee pay files after Phoenix was in place. The Department expected that Phoenix would increase pay advisor productivity through synergies; the use of a compensation web application by employees to enter some of their own pay requests, such as overtime; and the automation of pay processing. This expected increase in the productivity of Miramichi pay advisors and the resulting decrease in the total number of pay advisors was the main source of the $70 million a year the government expected to save starting in the 2016–17 fiscal year.

1.70 As part of the centralization project and before Phoenix was implemented, Public Services and Procurement Canada transferred to the Miramichi Pay Centre the pay files of 92,000 out of the 184,000 employees from the 46 departments whose pay operations were being centralized. The Department expected the Pay Centre to handle 92,000 pay files based on the 460 pay advisors handling an average of 200 files each.

1.71 We found that after the hiring of pay advisors was completed in Miramichi in January 2015, the Pay Centre could handle fewer employee pay files—not more—than before centralization. In July 2015, Public Services and Procurement Canada knew that pay advisors in Miramichi could each handle only about 150 employee pay files—well below the 184 pay files before centralization and the 200 pay files expected after centralization. This meant that Miramichi pay advisors could handle a total of about 69,000 pay files, not the 92,000 files the Department had transferred to the Pay Centre. In our view, this lower total was largely because of a lack of training and experience. Many pay advisors at the Pay Centre were new to the job because many pay advisors in departments and agencies did not move to Miramichi. In our fall 2017 audit of Phoenix pay problems, we found that before Phoenix, outstanding pay requests were already increasing because of centralization, and pay advisors in Miramichi were already complaining of excessive workload and stress.

1.72 Despite knowing that the Miramichi Pay Centre could handle 23,000 fewer files than expected before the implementation of Phoenix, Phoenix executives did not re-examine expected benefits for Phoenix. Phoenix executives also did not adjust the number of employee pay files that pay advisors were expected to handle or did not hire more pay advisors. Phoenix executives did not ensure that pay advisors could handle the files already assigned to them before doubling their workload by transferring the remaining 92,000 employee files to the Pay Centre. Even though pay advisors were less productive than what was expected of them, Phoenix executives still expected that their productivity would more than double when they started to use Phoenix. Before implementing the system, Phoenix executives should have first determined whether the pay advisors could handle 200 files each with the old system and then reconsidered the assumption that productivity would double under Phoenix.

1.73 Review of departments’ and agencies’ readiness. We found that Phoenix executives did not ensure that departments and agencies were ready to use Phoenix.

1.74 To assess readiness, Public Services and Procurement Canada required the departments and agencies to complete a checklist. The Department then compiled and analyzed the checklist information into dashboard readiness reports, which it regularly provided to all departments and agencies. According to the Department’s February 2016 dashboards, it had assessed that departments and agencies were ready for Phoenix.

1.75 However, Public Services and Procurement Canada could not explain to us how some of the dashboards’ readiness measures were calculated or what data supported them. Therefore, we reviewed the checklists submitted by the departments and agencies. We found that these checklists reported significant potential problems with Phoenix. For example, checklists completed in January 2016 reported significant problems with data coming from departments’ and agencies’ human resource systems not matching the data in Phoenix. Departments and agencies’ checklists noted that due to errors in the data transferred from the old pay system into Phoenix, hundreds of employees were at risk of not being paid or of receiving incorrect pay. We found no evidence that Public Services and Procurement Canada helped departments and agencies correct the problems they noted in their checklists.

1.76 In December 2015, departments’ and agencies’ concerns about Phoenix caused the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat to hire Gartner, an information technology consulting company, to assess departments’ and agencies’ readiness for Phoenix. The Gartner report, delivered on 11 February 2016, identified one risk it considered critical: Phoenix might not be able to pay employees accurately and on time because the system had not been fully tested and because system defects might not be corrected before implementation. The report also identified several risks to the implementation that it considered major, such as new procedures required to process pay with Phoenix that risked not being ready by the time Phoenix was implemented and that risked not being fully understood by departments and agencies.

1.77 Gartner recommended to the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat that Phoenix be gradually implemented in a limited number of departments starting with those that had less complicated pay needs. It also recommended that Phoenix and the old pay system be operated in parallel in case anything went wrong with Phoenix. As a recognized practice when replacing an old software system with a new one, both systems would operate in parallel during a certain time to compare their results to ensure that the results of the new system were accurate. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat transmitted the Gartner report to Public Services and Procurement Canada prior to the 26 February 2016 implementation of Phoenix.

1.78 The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat provided Phoenix executives with an invitation to participate in the Gartner assessment and to comment on Gartner’s preliminary findings and recommendations. However, we found that they did not participate until late January 2016, just before Phoenix was put in place. We found that they did not consider the report’s findings and recommendations before Phoenix was implemented.

1.79 Review of Phoenix pay system readiness. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s guidance recommends that information technology projects undergo independent reviews of readiness to proceed at key decision points, including at implementation. These reviews are meant to provide senior executives with

- strengthened accountability over these projects,

- additional information to determine whether and how to proceed,

- an opportunity to assess the quality of work to date,

- an opportunity to alter the project’s course and take corrective actions if necessary, and

- guidance when deciding whether to go ahead with implementation.

For the Phoenix project, Public Services and Procurement Canada hired S.i. Systems to do an external review of Phoenix readiness.

1.80 The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s guidance recommends that all development activities be completed before an independent review is conducted on a project’s readiness to be implemented. We found that this was not the case with Phoenix. For example, at the time of the review, testing had not been completed, user training was still under way, and some manual solutions were still being developed to make up for a lack of some functionality.

1.81 We also found that the review did not comply with the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s guidance on independence, because Phoenix executives had authority over the reviewers. Phoenix executives were involved in developing the reviewers’ interview questionnaire as well as the list of interviewees, and approved them. This list did not include representatives from departments and agencies, which were therefore not consulted on their readiness for Phoenix. According to the approved list of interviewees, only Phoenix project staff were interviewed.

1.82 We also found that the review’s positive conclusion—that Phoenix was ready to implement in two waves as scheduled—was inconsistent with the review’s own findings. For example, the review stated significant concerns with

- the lack of detailed and tested contingency plans,

- the ability to do future software upgrades, and

- outstanding security risks.

1.83 Recommendation. For all government-wide information technology projects, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat should

- carry out mandatory independent reviews of the project’s key decisions to proceed or not, and

- inform the project’s responsible Deputy Minister and senior executives of the reviews’ conclusions.

The Secretariat’s response. Agreed. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat will ensure that independent reviews of projects’ key decision points are completed for all government-wide information technology projects. The Secretariat will also inform projects’ accountable deputy ministers and senior executives of the reviews’ conclusions.

There was no oversight of the decision to implement Phoenix

1.84 We found that the Phoenix project had a detailed project management structure in place but did not include oversight independent of that structure. The Phoenix committees set up by Public Services and Procurement Canada did not provide independent advice to the Deputy Minister on project status. Instead, the Department created the project structure so that project information going to the Deputy Minister could only come from Phoenix executives. When Phoenix executives briefed the Deputy Minister just before Phoenix was implemented, they did not provide important information about problems with the system. It was questionable whether Phoenix executives fully understood the extent of the problems with Phoenix, and as a result, they did not provide a complete picture of the project’s risks. The lack of oversight allowed Phoenix executives to implement the system despite clear warnings that the Miramichi Pay Centre and departments and agencies were not ready and that the pay system had significant problems.

1.85 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

- Oversight of the Phoenix project

- Independent advice to the Deputy Minister

- Decision to implement Phoenix

1.86 These findings matter because if there had been effective oversight, the Deputy Minister of Public Services and Procurement would have received complete and accurate information on Phoenix readiness. This could have resulted in a different decision to implement the system.

1.87 Our recommendations in these areas of examination appear at paragraphs 1.103 and 1.104.

1.88 What we examined. We examined whether

- oversight bodies were in place and effective in guiding the decision to build and implement Phoenix,

- the Deputy Minister received independent advice on the project status, and

- the decision to implement Phoenix was reasonable and was based on complete and accurate information about the project’s readiness.

1.89 Oversight of the Phoenix project. The Treasury Board Policy on the Management of Projects states that the deputy head of a department is responsible for ensuring that effective project governance and oversight mechanisms are in place and for monitoring and reporting on the management of all projects in the department under the deputy head.

1.90 Public Services and Procurement Canada considered the Phoenix project management committees and structure it put in place to be governance and oversight. In our view, this was in fact just a project management structure. We found that there was no oversight of the Phoenix project independent of the project management structure. The project management was organized in such a way that project information that went to the Deputy Minister of Public Services and Procurement came only from Phoenix executives.

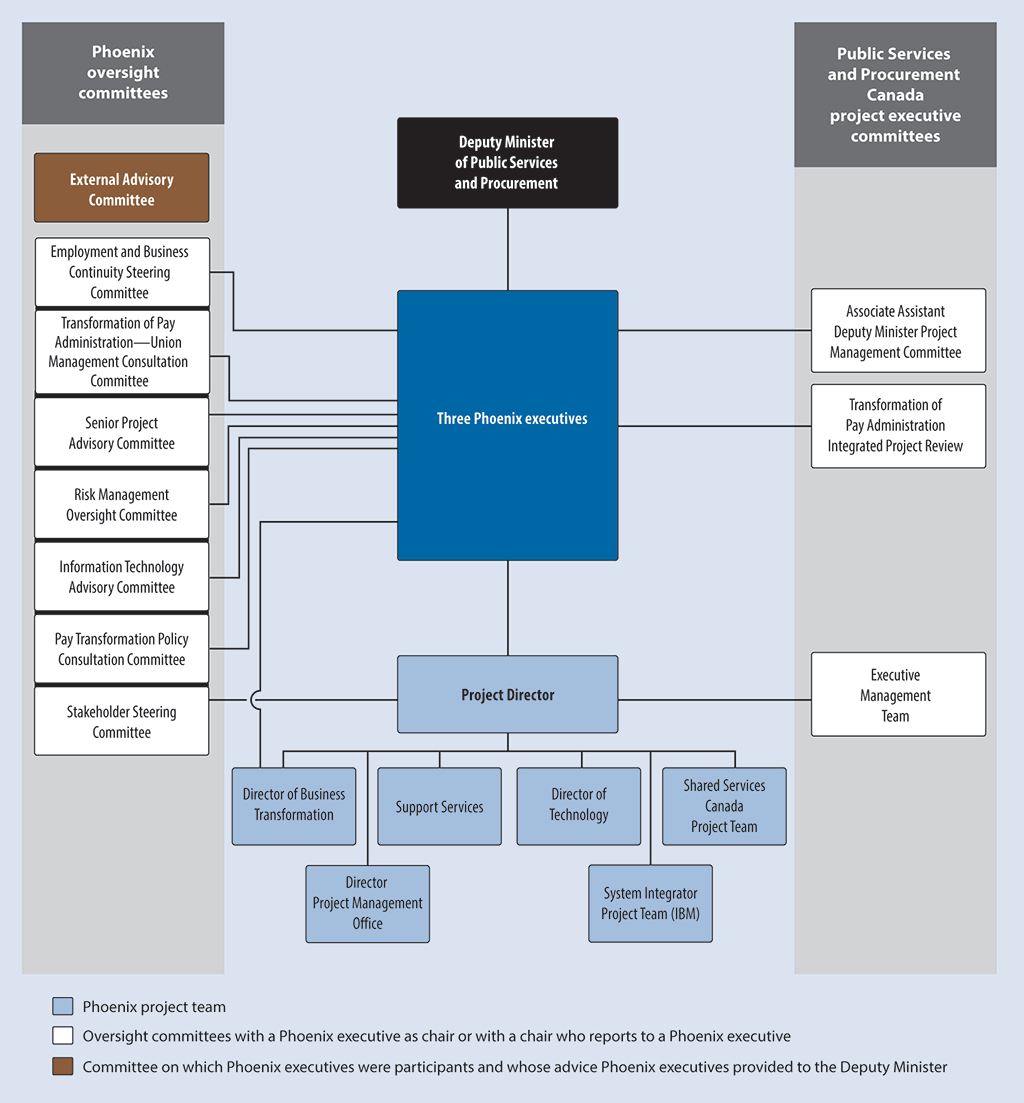

1.91 Public Services and Procurement Canada put in place many committees to guide the decisions about system design and implementation. However, most of these committees were either chaired by Phoenix executives or had committee chairs directly reporting to them. This meant that information coming from the committees would be provided to the Deputy Minister and to other stakeholders only by Phoenix executives (Exhibit 1.2). The Deputy Minister did not receive Phoenix project status information from independent sources, including the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, external reviews, and other departments and agencies.

Exhibit 1.2—Only Phoenix executives provided the Deputy Minister of Public Services and Procurement with project status information

Source: Based on information from Public Services and Procurement Canada

Exhibit 1.2—text version

This chart shows that only the three Phoenix executives provided the Deputy Minister of Public Services and Procurement with project status information.

This chart also shows that the three Phoenix executives were connected to many committees. The chart lists eight Phoenix oversight committees and three Public Services and Procurement Canada project executive committees.

One Phoenix oversight committee was the External Advisory Committee, a committee on which Phoenix executives were participants and whose advice Phoenix executives provided to the Deputy Minister.

The other seven Phoenix oversight committees and the three Public Services and Procurement Canada project executive committees were oversight committees with a Phoenix executive as chair or with a chair who reported to a Phoenix executive.

The other seven Phoenix oversight committees were

- the Employment and Business Continuity Steering Committee,

- the Transformation of Pay Administration—Union Management Consultation Committee,

- the Senior Project Advisory Committee,

- the Risk Management Oversight Committee,

- the Information Technology Advisory Committee,

- the Pay Transformation Policy Consultation Committee, and

- the Stakeholder Steering Committee.

The three Public Services and Procurement Canada project executive committees were

- the Associate Assistant Deputy Minister Project Management Committee,

- the Transformation of Pay Administration Integrated Project Review, and

- the Executive Management Team.

Six of the seven other Phoenix oversight committees and two of the three Public Services and Procurement Canada project executive committees connected directly to the three Phoenix executives. The two exceptions were the Stakeholder Steering Committee and the Executive Management Team—they both connected directly to the Project Director of the Phoenix project team. The Project Director connected directly to the three Phoenix executives.

Reporting to the Project Director were the following members of the Phoenix project team:

- the Director of Business Transformation,

- the Director of the Project Management Office,

- Support Services,

- the Director of Technology,

- the System Integrator Project Team at IBM, and

- the Shared Services Canada Project Team.

The Director of Business Transformation also connected directly to the three Phoenix executives.

Source: Based on information from Public Services and Procurement Canada

1.92 Deputy ministers of all departments and agencies are responsible for paying employees in a timely and accurate manner. We therefore expected that deputy ministers would be part of the oversight of the Phoenix project, which would give them an opportunity to provide input into the decision to implement. However, we found that deputy ministers from departments and agencies had no role in the Phoenix governance structure. They did not sit on any of the oversight bodies.

1.93 Independent advice to the Deputy Minister. Another essential element of a department’s oversight is independent advice from experts and stakeholders outside a project’s management. Every department has an internal audit function as a crucial part of its internal control system to provide such independent advice. The 2012 Treasury Board Policy on Internal Audit, which was in effect when Phoenix was implemented in February and April 2016, states that deputy ministers should receive independent assurance and advice from their internal audit groups to inform decision making. Internal auditing assesses and helps improve risk management, control, and governance processes. This helps ensure that a department achieves its objectives efficiently, using informed, ethical, and accountable decision making. A department’s internal audit function proposes audits based on each activity’s risk to the department.

1.94 For information technology projects such as Phoenix, an internal audit is an independent assessment of whether the project is achieving its objectives. Furthermore, internal auditing in the early stages of an information technology project increases the chances that it will succeed. An internal audit of Phoenix would have been crucial, considering the risks posed by the number of transactions it had to process, its cost, its promise to rapidly save money, its government-wide nature, and its need to process about $22 billion in annual payroll. Public Services and Procurement Canada’s internal audit function should therefore have audited the Phoenix project and reported its findings directly to the Deputy Minister.

1.95 We found that the Department’s internal audit function considered the risks but did not audit the Phoenix project even though departmental files showed that four internal audits of Phoenix were intended. In our view, internal audits of the Phoenix project would have given the Deputy Minister an independent source of assurance as part of a review of the project’s management that could have resulted in a different implementation decision.

1.96 A final opportunity to give the Deputy Minister of Public Services and Procurement independent, accurate, and complete information on the readiness of Phoenix was the review by S.i. Systems. However, as stated in paragraph 1.81, we found that the review was not independent of the project team.

1.97 Decision to implement Phoenix. Before going ahead with implementing Phoenix, Phoenix executives knew about serious problems with it, including high security risks and privacy risks. They also knew that the new pay system could not perform critical functions, such as processing requests for retroactive pay or automatically calculating certain types of pay. They also had a summary of test results highlighting major defects found through testing that were still not resolved. They also knew that some testing was not completed or successful.

1.98 On 29 January 2016, Public Services and Procurement Canada representatives, including Phoenix executives, told deputy ministers and associate deputy ministers that the Department was going to implement Phoenix in two waves, in February and April 2016. The briefing took place in a meeting of more than 30 deputy ministers and associate deputy ministers at the Public Service Management Advisory Committee, an advisory forum that discusses government-wide management issues. This Committee did not have a governance or oversight responsibility for the Phoenix project and did not have any decision-making authority. Because deputy ministers from departments and agencies had no role in the Phoenix governance structure, Public Services and Procurement Canada decided to use the Committee meeting to communicate its implementation plans to the deputy ministers.

1.99 Just before this briefing of the Committee, 14 departments and agencies, including some of the largest in the federal government, told Public Services and Procurement Canada that they had significant concerns with Phoenix, including

- inadequate training material and training,

- the Miramichi Pay Centre’s inability to process pay requests accurately and on time,

- unclear roles and responsibilities for Phoenix, and

- the incomplete and unsuccessful testing of Phoenix.

1.100 However, during the Committee briefing on 29 January 2016, Public Services and Procurement Canada representatives assured deputy ministers and associate deputy ministers that these problems had been resolved or that the Department had procedures in place to resolve them. For example, the representatives said that there were more than 100 outstanding defects in Phoenix, but that there were manual solutions in place to mitigate them. Public Services and Procurement Canada also told deputy ministers and associate deputy ministers that not implementing Phoenix in February and April 2016 presented several significant risks, including

- a lack of money and pay advisors to keep the old pay system running while waiting for Phoenix to be put in place,

- the need for additional funding to be requested from the Treasury Board, and

- a possible long delay before there was another chance to implement Phoenix.

As an information-sharing and advisory forum, the Committee could not formally challenge the information it received from Public Services and Procurement Canada or the decision to implement Phoenix.

1.101 Phoenix executives then briefed the Deputy Minister of Public Services and Procurement on 18 February 2016 on the implementation of the Phoenix system and told him that everything was ready to go. We found that documentation provided at the briefing did not mention any of the significant problems that Phoenix executives knew about. Furthermore, Phoenix executives did not tell the Deputy Minister about these significant problems, including the critical and major risks identified in the Gartner report prepared for the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (see paragraphs 1.76 to 1.78). The Deputy Minister did not receive independent advice on the Phoenix pay system’s readiness and relied solely on Phoenix executives.

1.102 Formal documents approving the Phoenix project confirm that Phoenix executives were responsible for deciding to implement Phoenix. However, we found that the decision to proceed with the implementation of Phoenix was not documented, which was contrary to the requirements of the project and to recognized practices. In the absence of an explicit decision, we found that Phoenix executives in effect decided to implement Phoenix. In our opinion, they had received more than enough information and warning that Phoenix was not ready to be implemented, and therefore, they should not have proceeded as planned. Phoenix executives prioritized meeting schedule and cost over other critical elements, such as functionality and security, resulting in an incomprehensible failure of project management and oversight. In our fall 2017 audit of Phoenix pay problems, we found that not only did Phoenix not meet user needs to pay employees accurately and on time, it has resulted in significant costs to the federal government and to thousands of its employees.

1.103 Recommendation. For all government-wide information technology projects under its responsibility, Public Services and Procurement Canada should ensure that an effective oversight mechanism is in place, is documented, and is maintained. The mechanism should first be approved by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat and should include the heads of concerned departments and agencies.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Moving forward, Public Services and Procurement Canada will ensure that for all government-wide information technology (IT) projects under its responsibility, it will put in place, document, and maintain an effective oversight mechanism approved by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. The mechanism’s membership will include the Secretariat and representation from a selected group of deputy heads of concerned departments and agencies. Terms of reference approved by the Secretariat and the Department, in consultation with the Privy Council Office, will clarify the roles and responsibilities of the oversight committee participants in regard to the government-wide IT projects and to colleague deputy heads of departments and agencies not specifically represented on the committee.

1.104 Recommendation. For all government-wide information technology projects under its responsibility, Public Services and Procurement Canada should ensure that its internal audit function provides the Deputy Minister with assurances regarding the projects’ governance, oversight, and management.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Moving forward, Public Services and Procurement Canada will ensure that the internal audit function provides the Deputy Minister with the appropriate assurances regarding project governance, oversight, and management of government-wide IT projects under the Department’s responsibility. The Department will accomplish this by working with other internal audit functions of concerned departments and agencies to develop an audit strategy that will provide a holistic view of project governance, oversight, and management risks.

The Department will support government-wide initiatives to strengthen the capacity of the internal audit community, to provide assurance regarding major transformation initiatives.

Conclusion

1.105 We concluded that the Phoenix project was an incomprehensible failure of project management and oversight. Phoenix executives prioritized certain aspects, such as schedule and budget, over other critical ones, such as functionality and security. Phoenix executives did not understand the importance of warnings that the Miramichi Pay Centre, departments and agencies, and the new system were not ready. They did not provide complete and accurate information to deputy ministers and associate deputy ministers of departments and agencies, including the Deputy Minister of Public Services and Procurement, when briefing them on Phoenix readiness for implementation. In our opinion, the decision by Phoenix executives to implement Phoenix was unreasonable according to the information available at the time. As a result, Phoenix has not met user needs, has cost the federal government hundreds of millions of dollars, and has financially affected tens of thousands of its employees.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on the building and implementation of the Phoenix project. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs, and to conclude on whether the management of the Phoenix project complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard for Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office applies Canadian Standard on Quality Control 1 and, accordingly, maintains a comprehensive system of quality control, including documented policies and procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we have complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entities’ management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit;

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit;

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided; and

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate.

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether Public Services and Procurement Canada effectively and efficiently managed the delivery of the Phoenix project.

Scope and approach

We audited the following nine departments and agencies:

- the Canadian Security Intelligence Service,

- Correctional Service Canada,

- Employment and Social Development Canada,

- National Defence,

- Natural Resources Canada,

- Public Services and Procurement Canada,

- the Royal Canadian Mounted Police,

- Statistics Canada, and

- the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

We examined the legislation, policies, and procedures in place to manage and to support the management of the Phoenix project within all the audited departments and agencies. We also met and interviewed officials in all the audited entities, including at the Public Service Pay Centre in Miramichi, New Brunswick.

We analyzed data extracted from the information systems of Public Services and Procurement Canada’s case management tool to identify and compare information related to the processing of pay. Although we noted issues with the integrity of data, we found the data sufficiently reliable for the purpose of our analysis.

We analyzed the emails of 10 senior executives from Public Services and Procurement Canada, including the three Phoenix executives, to identify information related to the management and oversight of the Phoenix project. The emails we looked at were sent during the period of the audit, which spans from 1 April 2008 to the second wave of the Phoenix pay system on 21 April 2016.

We used the results of a survey that we conducted during our fall 2017 audit of Phoenix pay problems. It was a survey of pay staff in Miramichi as well as in the satellite centres, which were set up by Public Services and Procurement Canada to increase the Department’s pay processing capacity. The survey’s purpose was to understand the impact on pay advisors of pay problems after Phoenix was first implemented. We sent 740 questionnaires and received responses from 480 employees, for a total response rate of approximately 65%.

We used our review of similar events around the world, which we performed during our audit of Phoenix pay problems, to get a better understanding of causes and responses.

We did not examine events leading to the centralization of pay advisors, other than expected efficiencies to be achieved from the centralization, or the events after Phoenix was implemented, other than referring to findings from our report on Phoenix pay problems.

Criteria

To determine whether Public Services and Procurement Canada effectively and efficiently managed the delivery of the Phoenix project, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Key Phoenix decisions by Public Services and Procurement Canada are based on project management principles that consider impacts on the realization of expected project outcomes and on pay operations of line departments and agencies. |

|

|

Public Services and Procurement Canada develops and communicates changes to the Government of Canada pay processes and systems resulting from the Phoenix project to line departments and agencies, and provides requisite support, tools, and training. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period between 1 April 2008 and 21 April 2016. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies. However, to gain a more complete understanding of the subject matter of the audit, we also examined certain matters that preceded the starting date of this period and followed the ending date of this period.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 9 March 2018, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

Principal: Jean Goulet

Director: Jan-Alexander Denis

Glen Barber

Danny Bruni

Nicole Grant

Manav Kapoor

Kevin Kit

Jocelyn Lefèvre

Elisa Metza

William Xu

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge the contribution of Nancy Cheng, Assistant Auditor General, to the production of this report.

List of Recommendations

The following table lists the recommendations and responses found in this report. The paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report, and the numbers in parentheses indicate the location of the related discussion.

Managing the development of Phoenix

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

1.48 For government-wide information technology projects under its responsibility, Public Services and Procurement Canada should ensure the following:

|

The Department’s response. Agreed. Moving forward, Public Services and Procurement Canada will ensure that, for all government-wide information technology (IT) projects under its responsibility, it will seek appropriate authorities to define and assign roles and responsibilities of concerned stakeholders. This will permit the Department to measure and report on collective efforts with regard to project management and to ensure that implicated partners and stakeholders participate in, and support the assessment of, the cumulative impacts of key decisions and risk mitigations, including changes to functionality. The Department’s National Project Management System requires compliance with legal and policy requirements related to project management. The Department will ensure that project managers understand and respect these requirements. It will also ensure that project managers understand well the requirements for preparing a stakeholder engagement plan, a formal software upgrade plan, and a comprehensive contingency plan that covers government-wide systems, processes, and impacts for all government-wide IT projects under its responsibility. The Department will integrate the lessons learned from Phoenix into project management practices and training and will support government-wide efforts to strengthen the capacity of the project management community. |

|

1.61 For government-wide projects under its responsibility, Public Services and Procurement Canada should

|

The Department’s response. Agreed. Moving forward, Public Services and Procurement Canada will ensure that for all government-wide information technology projects under its responsibility, it seeks authority to do the following:

|

Deciding to implement Phoenix

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

1.83 For all government-wide information technology projects, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat should

|

The Secretariat’s response. Agreed. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat will ensure that independent reviews of projects’ key decision points are completed for all government-wide information technology projects. The Secretariat will also inform projects’ accountable deputy ministers and senior executives of the reviews’ conclusions. |

|

1.103 For all government-wide information technology projects under its responsibility, Public Services and Procurement Canada should ensure that an effective oversight mechanism is in place, is documented, and is maintained. The mechanism should first be approved by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat and should include the heads of concerned departments and agencies. (1.88 to 1.102) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. Moving forward, Public Services and Procurement Canada will ensure that for all government-wide information technology (IT) projects under its responsibility, it will put in place, document, and maintain an effective oversight mechanism approved by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. The mechanism’s membership will include the Secretariat and representation from a selected group of deputy heads of concerned departments and agencies. Terms of reference approved by the Secretariat and the Department, in consultation with the Privy Council Office, will clarify the roles and responsibilities of the oversight committee participants in regard to the government-wide IT projects and to colleague deputy heads of departments and agencies not specifically represented on the committee. |

|

1.104 For all government-wide information technology projects under its responsibility, Public Services and Procurement Canada should ensure that its internal audit function provides the Deputy Minister with assurances regarding the projects’ governance, oversight, and management. (1.88 to 1.102) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. Moving forward, Public Services and Procurement Canada will ensure that the internal audit function provides the Deputy Minister with the appropriate assurances regarding project governance, oversight, and management of government-wide IT projects under the Department’s responsibility. The Department will accomplish this by working with other internal audit functions of concerned departments and agencies to develop an audit strategy that will provide a holistic view of project governance, oversight, and management risks. The Department will support government-wide initiatives to strengthen the capacity of the internal audit community, to provide assurance regarding major transformation initiatives. |