2018 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada Independent Auditor’s ReportReport 3—Administration of Justice in the Canadian Armed Forces

2018 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of CanadaReport 3—Administration of Justice in the Canadian Armed Forces

Independent Auditor’s Report

Introduction

Background

3.1 Canada’s military justice system functions in parallel with the civilian justice system. Like the civilian system, the military justice system must be fair and respect the rule of law.

3.2 The purpose of the military justice system is to contribute to the Canadian Armed Forces’ effectiveness by maintaining discipline, efficiency, and morale. It applies to all members, including 66,096 regular forces members and 21,873 primary reserve forces members as of March 2017.

3.3 The military justice system is anchored in the National Defence Act, which includes the Code of Service Discipline, and the Queen’s Regulations and Orders for the Canadian Forces. Together, these describe various offences, as well as authorities, rules, and procedures.

3.4 Charges may be laid for military offences under the Code of Service Discipline for incidents that occur in the military context, such as insubordination or absence without permission, and incidents that also occur in the civilian context, such as theft or sexual assault. If a murder, manslaughter, or child abduction charge is brought against a military member for an incident that happened in Canada, it would be handled by the civilian justice system.

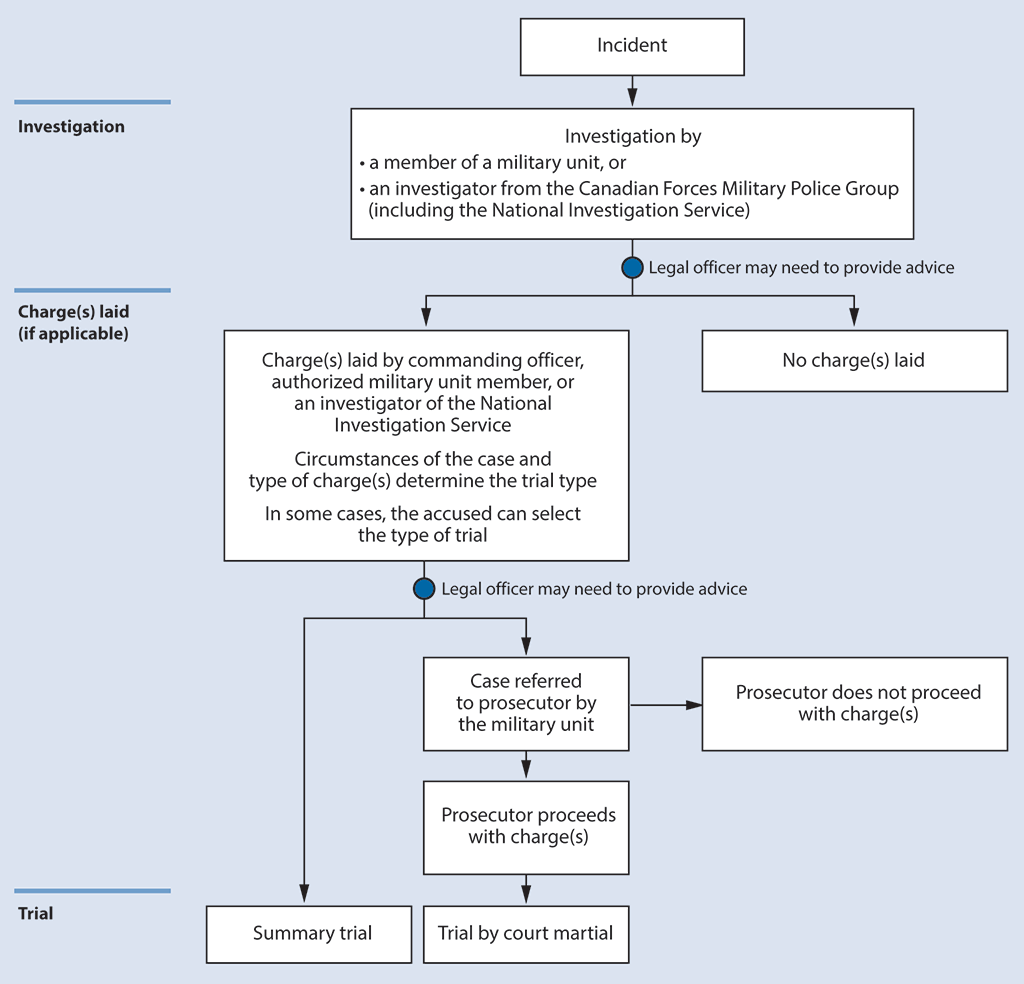

3.5 The military justice system has two levels (Exhibit 3.1). Charges can be dealt with through a summary trial or by court martial.

- Summary trials are intended to dispense prompt but fair justice for less serious offences. Summary trials are presided over by commanding officers or other authorized officers. Generally, the accused is not represented by legal counsel in a summary trial.

- A court martial is a formal trial presided over by a military judge. The accused has the right to be represented by legal counsel. A court martial follows many of the same rules that apply to criminal proceedings in civilian courts.

The circumstances of each case, including the nature of the charges and the rank of the accused, will determine whether the case will proceed by summary trial or by court martial. In some cases the accused can select the type of trial.

Exhibit 3.1—Basic steps of the military justice process

Source: Based on information from National Defence.

Exhibit 3.1—text version

The flowchart shows the basic steps of the military justice process, from the investigation of an incident through to a trial. If the decision is to proceed to trial, the two types of trial are summary trial or trial by court martial.

The process starts with an incident.

In the investigation phase, the incident is investigated by a member of a military unit, or an investigator from the Canadian Forces Military Police Group (including the National Investigation Service). A legal officer may need to provide advice before the next phase, which is the charge laying phase.

In the charge laying phase, a charge is laid or charges are laid by a commanding officer, authorized military unit member, or an investigator of the National Investigation Service. The circumstances of the case and type of charge or charges determine the trial type. In some cases, the accused can select the type of trial. Or, in the alternative, no charge is laid. A legal officer may need to provide advice before the next steps.

Finally, when a charge is laid or charges are laid, the case then either goes directly to a summary trial or is referred to a prosecutor by the military unit. When the case is referred to a prosecutor by the military unit, the prosecutor decides whether to proceed with the charge or charges.

When the prosecutor decides to proceed with the charge or charges, the case goes to trial by court martial.

Source: Based on information from National Defence.

3.6 As detailed in Exhibit 3.2, specific individuals and services have responsibilities within the military justice system.

Exhibit 3.2—Primary roles and responsibilities for military justice

| Role | Responsibility |

|---|---|

|

Commanding officers of military units |

Commanding officers are responsible for maintaining discipline among the members of the military units across the Canadian Armed Forces, including the Canadian Army, the Royal Canadian Air Force, and the Royal Canadian Navy. They have the authority to request and assign investigations, lay charges, preside over summary trials, and impose punishments. They can also delegate some of these authorities. |

|

Canadian Forces Military Police Group (Military Police) |

Under the authority of the Canadian Forces Provost Marshal, the Military Police has the authority to investigate alleged incidents. Part of this group, the National Investigation Service investigates serious and sensitive offences. Its investigators can lay charges. |

|

Office of the Judge Advocate General |

The Judge Advocate General is the legal adviser to the Governor General of Canada, the Minister of National Defence, and the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces on matters relating to military law. Despite the position title, the Judge Advocate General does not have judicial functions. The Judge Advocate General also has the superintendence of the administration of military justice in the Canadian Armed Forces. As such, the Office of the Judge Advocate General is responsible for developing legislation, policies, and directives on military justice. It also provides legal advice to military units, and reviews and reports on the military justice system. |

|

Office of the Chief Military Judge (including the Court Martial Administrator) |

This office includes the Chief Military Judge and three other military judges. They preside over court martial cases. The Court Martial Administrator provides administrative support to the Chief Military Judge. |

|

Canadian Military Prosecution Service |

Under the authority of the Director of Military Prosecutions, this office determines whether to proceed with charges that would be tried by court martial, and it is responsible for the conduct of all court martial prosecutions. The Director of Military Prosecutions also counsels the Minister of National Defence in cases that are appealed. |

|

Defence Counsel Services |

Under the direction of the Director of Defence Counsel Services, this office provides legal advice and representation. |

Focus of the audit

3.7 This audit focused on whether the Canadian Armed Forces administered the military justice system efficiently. In particular, we assessed the effectiveness of the Canadian Armed Forces in processing military justice cases in a timely manner.

3.8 This audit is important because the purpose of the military justice system is to maintain discipline, efficiency, and morale in the Canadian Armed Forces.

3.9 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Administering military justice

Overall message

3.10 Overall, we found that the Canadian Armed Forces took too long to resolve many of its military justice cases, with significant impacts in some cases. In the 2016–17 fiscal year, a court martial dismissed charges in one case because of delay, and delay was a reason why military prosecutors decided not to proceed to trial in an additional nine cases. In addition, we found that commanding officers did not immediately inform Defence Counsel Services of the accused’s request for defence counsel, and prosecutors did not provide the accused with all relevant information for their defence as soon as was practical.

3.11 These findings matter because Canadians expect their armed forces to be disciplined, with unacceptable behaviour investigated and addressed promptly. When there are delays in the military justice process, accused persons and victims remain in a state of uncertainty. Delays in providing accused persons with defence counsel, and information about their case, can breach their constitutional rights. In addition, such delays can erode confidence in the Canadian Armed Forces’ administration of discipline and justice.

3.12 The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees every accused person the right to be tried within a reasonable time, and to retain and instruct defence counsel without delay. The Supreme Court of Canada recently emphasized that the prompt processing of charges is a fundamental principle.

3.13 Various stakeholders administer the military justice system. These are

- units of the Canadian Armed Forces (which belong to various commands such as the Canadian Army, Royal Canadian Navy, and Royal Canadian Air Force);

- the Military Police;

- the Office of the Chief Military Judge (including the Court Martial Administrator); and

- the Office of the Judge Advocate General, including the Canadian Military Prosecution Service and Defence Counsel Services.

They share the responsibility of processing cases in a fair and efficient manner.

Delays in resolving military justice cases contributed to 10 cases being dismissed or not proceeding to court martial

3.14 We found delays throughout the various stages of the military justice process. We also found that the Canadian Armed Forces did not set time standards for some steps of the process. In our opinion, it often took too long to decide whether charges should be laid and to refer cases to prosecutors. Prosecutors did not meet their time standards for making decisions to proceed to court martial. Where they did proceed, it took too long to schedule the court martial.

3.15 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

3.16 This finding matters because delays prevent the Canadian Armed Forces from enforcing discipline promptly and dispensing justice in a timely manner.

3.17 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 3.31.

3.18 What we examined. We examined how long it took the Canadian Armed Forces to process military justice cases. We examined a sample of 117 summary trial cases and 20 court martial cases completed in the 2016–17 fiscal year.

3.19 Delays in summary trials. Although the summary trial process is intended to administer swift justice, we found delays that could erode confidence in the military leadership’s ability to enforce discipline.

3.20 According to the Judge Advocate General 2016–17 Annual Report, 553 summary trials were completed in that fiscal year. The Judge Advocate General reported that these cases took an average of three months to complete from the time of the offence, but that about 18% took more than six months. These summary trial cases mostly involved minor disciplinary charges.

3.21 Of the 117 summary trial cases we examined, 99 were investigated solely by the military units. In these 99 cases, we found that the process to lay charges took too long. On average, the units completed the investigation within 1.5 weeks, but commanding officers took an additional 5 weeks, on average, to lay the charges. We also found that the summary trial files contained no justifications for these delays.

3.22 The Military Police investigated the other 18 summary trial cases we examined. The Military Police’s internal policy sets a time standard of 30 days to deliver the results of their investigations to the commanding officers of the units. The policy requires that investigators justify on file whenever the time standard was not met. We found that 12 of the 18 cases took more than 30 days to investigate, with no written justifications for any of those 12 cases.

3.23 Delays in court martial cases. According to the Judge Advocate General 2016–17 Annual Report, 56 court martial cases were conducted in that fiscal year. We reviewed 20 of these cases and found delays throughout the process.

3.24 We found the following delays in the steps before charges were laid:

- Investigating. Investigations are conducted prior to deciding whether to lay charges. The Military Police investigated 16 of the 20 cases we reviewed. We found that all of these investigations took longer than the 30-day time standard to complete. The investigations in these 16 cases took an average of 6 months to complete, including 2 cases that took longer than a year. Despite the Military Police’s internal policy, we found no written justifications for any of these 16 cases that took more than 30 days to investigate.

- Laying charges. After the investigation, commanding officers, or their delegates, took a long time to lay the charges in many cases. Of the 20 cases we examined, we found that it took over 3 months for 4 cases, including 1 case for which it took about one year. No time standard has been defined for laying charges.

3.25 We found the following delays after charges were laid:

- Referring charges to a prosecutor. After charges were laid, the commanding officers and their superiors took 2 months, on average, to refer charges to the Director of Military Prosecutions. No time standard has been defined for this phase of the process.

- Proceeding to a court martial. Although the time standard for prosecutors to decide whether to proceed to court martial is 30 days, or 44 depending on circumstances, it took an average of 3 months for the prosecutor to make this decision.

- Setting the date for a court martial. After the prosecutor decided to proceed to court martial, it took an average of 5.5 months for the prosecutor and the defence counsel to hold a teleconference call with the Chief Military Judge to set the date for the trial.

3.26 In our opinion, these delays prevented the Canadian Armed Forces from enforcing prompt and efficient discipline, and ensuring that justice was carried out in a timely manner.

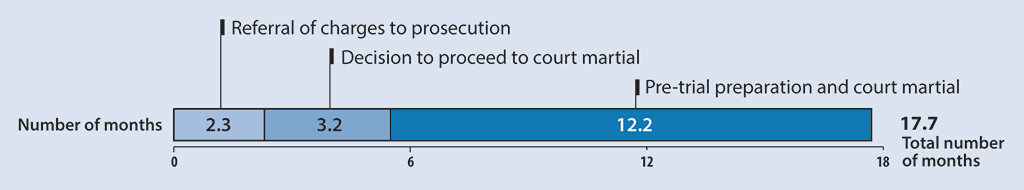

3.27 Regarding timeliness, a Supreme Court of Canada decision in 2016 (R. versusv. Jordan) emphasized the need for prompt administration of justice. It established the principle that most trials should be completed within an 18-month timeline after the laying of charges. When courts martial take too long, there is a risk that cases involving serious charges could be dismissed because of delays. For the 20 cases that we examined, the average amount of time to complete the court martial process was very close to this 18-month time limit (Exhibit 3.3).

Exhibit 3.3—Average time to complete 20 court martial cases was almost 18 months

Exhibit 3.3—text version

This timeline shows the average number of months it took to complete the 20 court martial cases examined. It also shows that the average amount of time to complete the 20 court martial cases was close to 18 months.

It took an average of 2.3 months to refer the charges to prosecution.

It took an average of 3.2 months to decide to proceed to court martial.

It took an average of 12.2 months for the pre-trial preparation and court martial.

In total, it took an average of 17.7 months to complete the 20 court martial cases.

3.28 The average time to complete the 20 cases was 17.7 months after charges were laid, and 9 cases took more than 18 months to complete.

3.29 We found 10 examples outside of our sample of 20 completed cases where delays contributed to decisions to dismiss or not to proceed with charges:

- In February 2017, a court martial dismissed charges, including a charge of assault causing bodily harm, because of delays. The court estimated that if the trial had proceeded, over two years (25 months) would have elapsed from the time the charges were laid to the anticipated completion of the trial. As a result, the court concluded that the constitutional rights of the accused to be tried in a reasonable time had been violated.

- In the 2016–17 fiscal year, military prosecutors decided not to proceed to court martial in 53 cases. According to the Director of Military Prosecutions, delays were the sole reason for 2 of these cases, and among the reasons for 7 other cases.

3.30 The Supreme Court of Canada has stated that justice delayed is justice denied. Unreasonable delays in the administration of military justice denies justice to the accused, victims and their families, and Canadians.

3.31 Recommendation. The Canadian Armed Forces should review its military justice processes to identify the causes of delays and to implement corrective measures to reduce them.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. As mentioned at paragraph 3.69, the Office of the Judge Advocate General has received funding for and is developing a military justice case management tool and database. This system, called the Justice Administration and Information Management System, or JAIMS, is being developed in the 2018–19 fiscal year in collaboration with the Assistant Deputy Minister (Information Management). It is expected that the JAIMS will be piloted beginning in January 2019 and will be launched in September 2019.

The JAIMS will electronically track discipline files from the receipt of a complaint through to closure of the file. The system will allow military justice stakeholders to access real-time data on files as they progress through the military justice system and will prompt key actors when they are required to take action. It is expected that management of military justice system files with the JAIMS will significantly reduce delays. The JAIMS will also be integrated with a new military justice performance measurement system, expected to be launched concurrently. This system will deliver measurable data on the performance of the military justice system, allowing for the identification of system weaknesses—including in the area of delay—and the development of targeted measures to address them.

There were systemic weaknesses in the military justice process

3.32 We found systemic weaknesses in the process that contributed to delays in enforcing discipline and administering justice. For example, the Canadian Armed Forces had not defined time standards for every phase of the military justice system. Even when time standards were defined, unexplained delays still occurred. We also found that human resource practices did not support the development of specialized expertise in litigation.

3.33 In addition, we found that commanding officers did not immediately inform Defence Counsel Services of the accused’s request for defence counsel. Further, prosecutors did not provide the accused with all relevant information for their defence as soon as was practical. As well, we found that the processes used by the Military Police to inform military units, and by the Canadian Military Prosecution Service to inform the Military Police, were inefficient.

3.34 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

- Lack of time standards

- Inadequate communication between Military Police investigators and other parties

- Late communication with Defence Counsel Services

- Risk that sufficient military litigation expertise not developed

3.35 This finding matters because systemic weaknesses in managing the military justice system can undermine the accused’s rights for a prompt and fair resolution.

3.36 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 3.43, 3.47, 3.52, and 3.57.

3.37 What we examined. We examined the time standards and procedures that various stakeholders developed to exercise their duties and functions. We also examined how military units and the Office of the Judge Advocate General implemented these procedures.

3.38 Lack of time standards. The National Defence Act and its regulations impose a duty to act promptly, but this duty is not explained in concrete terms. Various reviews of the military justice system have recommended establishing time standards for various stages of the military justice process. We discuss reviews in more detail in paragraphs 3.71 to 3.75.

3.39 We found that the Canadian Armed Forces had not defined time standards for every phase of the military justice process. In particular, they had not established any time standards for commanding officers and their superiors to exercise their duties and functions. As discussed above, commanding officers took a long time to lay charges in summary trial cases (see paragraph 3.21). Commanding officers and their superiors also took a long time to refer charges to the Director of Military Prosecutions in court martial cases (see paragraph 3.25).

3.40 The policy of the Director of Military Prosecutions on court martial disclosure does not establish time standards for disclosing evidence to the accused, and does not require prosecutors to document the reasons for delays in disclosing evidence to the accused.

3.41 We found some time standards had been developed. For example,

- the Judge Advocate General—time to provide legal advice: 7 to 30 days depending on circumstances;

- the Military Police—time to complete investigations: 30 days; and

- the Director of Military Prosecutions—time for a decision on whether to proceed to court martial: 30 or 44 days, depending on circumstances.

We found that even when time standards were defined, some unexplained delays still occurred.

3.42 It is our view that establishing time standards for all parts of the military justice process, and tracking whether they are being met or enforced, may help to determine why delays occur and find ways to reduce them.

3.43 Recommendation. The Canadian Armed Forces should define and communicate time standards for every phase of the military justice process and ensure there is a process for tracking and enforcing them.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Office of the Judge Advocate General will conduct a review of time requirements for every phase of the military justice system process. This review will allow for the identification and, by January 2019, the introduction of time standards that would benefit the military justice process in a manner that respects rules of fairness and legal requirements.

The Justice Administration and Information Management System, or JAIMS, expected to be operational in September 2019, will incorporate all time standards and will allow for real-time tracking of files as they proceed through the system. The JAIMS will also prompt decision makers when action is required. The military justice performance measurement system, linked to the JAIMS, will deliver data on compliance with time standards.

The JAIMS could also be used to require decision makers at various stages to justify why they could not meet time standards, which will assist in identifying and resolving the causes of delays.

3.44 Inadequate communication between Military Police investigators and other parties. In order to determine whether charges will be laid, commanding officers and their legal advisers need to consider the evidence from the investigation. Military Police investigators are required to provide a summary of each investigation to the relevant military unit.

3.45 We examined 18 summary trial cases that the Military Police investigated. After having received the summary of the investigation, the commanding officers, or legal officers, requested more information from the Military Police in several of these cases before they made their decisions. This contributed to delays. In 5 of these cases, this added, on average, an extra three weeks to the process. In 2 other cases, it added 5 and 10 months to the process, respectively.

3.46 There was no formal requirement for the Canadian Military Prosecution Service to communicate with the Military Police about whether charges were laid, or to provide feedback on the quality of the police investigations. We did not see evidence of this type of communication on a regular basis. We found that this lack of communication limited the Military Police’s ability to update its database and to improve the quality of future investigations.

3.47 Recommendation. The Canadian Armed Forces should establish formal communication processes to ensure that the Military Police, the Director of Military Prosecutions, the Judge Advocate General’s legal officers, and the military units receive the information that they need to carry out their duties and functions in a timely manner.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Military Police Group, the Canadian Military Prosecution Service, legal officers within the Office of the Judge Advocate General, military units, as well as Defence Counsel Services will all have access to the Justice Administration and Information Management System, or JAIMS, which is expected to be operational in September 2019. This will enable decision makers to access real-time information concerning files. In addition, the Office of the Judge Advocate General is undertaking a full review of the policies respecting the disclosure of Military Police reports. This review is expected to be completed by summer 2018 and to be followed by the development of new standards—within the 2018–19 fiscal year—for the timely and complete delivery of these Military Police reports.

The re-establishment of the Military Justice Round Table, planned for the spring of 2018, will bring together stakeholders from the Court Martial Appeal Court of Canada, Office of the Chief Military Judge, Office of the Judge Advocate General, Canadian Forces Provost Marshal, Canadian Military Prosecution Service, and Defence Counsel Services to provide a forum to discuss military justice challenges and options to implement best practices.

Further, the Director of Military Prosecutions is examining how additional legal support can be provided to the Canadian Forces Military Police Academy in order to facilitate the provision of information between military prosecutors and the Military Police, as well as to assist in the improvement of the quality of future investigations through coordinated training and feedback. It is anticipated that a comprehensive solution to this will be put in place by summer 2019.

3.48 Late communication with Defence Counsel Services. In court martial cases, the accused is entitled to be represented by defence counsel. The commanding officer is required to ask whether the accused wants to be represented by defence counsel, and must immediately inform the Director of Defence Counsel Services of the accused’s decision.

3.49 In 14 of the 20 court martial cases that we examined, commanding officers did not immediately inform the Director of Defence Counsel Services of the accused’s decision regarding representation. In 4 of these cases, more than 30 days passed before the Director of Defence Counsel Services was notified that an accused had requested counsel. In our view, any delays in informing Defence Counsel Services are unacceptable given the accused’s right to obtain legal advice and representation without delay.

3.50 Prosecutors have a legal duty to disclose all relevant information to the defence. The Director of Military Prosecution’s policy on disclosure requires prosecutors to disclose evidence to the accused as soon as is “practicable.” However, the policy does not define what this means.

3.51 Of the 20 court martial cases we examined, we found that in 19 cases prosecutors took an average of three months to disclose evidence to defence counsel, and over a year for the other case. In 13 of these 20 cases, we found that prosecutors disclosed evidence to defence counsel only after the prosecutor had decided to proceed to court martial. In our opinion these examples are not consistent with the requirement to disclose evidence as soon as is practical.

3.52 Recommendation. The Canadian Armed Forces should define and communicate expectations for the timely disclosure of all relevant information to members charged with an offence.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Office of the Judge Advocate General is conducting a review of timelines for the delivery of disclosure to those charged with an offence. It is expected that this review will be completed by January 2019.

The Director of Military Prosecutions has already instituted a number of changes to expedite disclosure to defence counsel. For example, before a file is assigned to a prosecutor, the prosecutor’s supervisor will request disclosure from the appropriate investigative agency. In addition, prosecutors have been instructed to send disclosure to defence counsel once they have received and reviewed it and prior to making a decision (whether to prefer a charge).

Further, in spring 2018, the Office of the Judge Advocate General will remind commanding officers of their obligation to immediately inform the Director of Defence Counsel Services of the accused’s decision on whether the accused wishes to be represented by defence counsel.

3.53 Risk that sufficient military litigation expertise not developed. The Office of the Judge Advocate General has 134 legal officers who provide legal services to the Canadian Armed Forces in Canada and abroad on all aspects of military law. The Office manages and assigns legal officers to various services, including military prosecution. Legal officers rotate through a wide range of military legal services to acquire broad and general legal experience, from compensation to military operations.

3.54 In 2008, an external review for the Director of Military Prosecutions (the Bronson Report) determined that, on average, Canadian Armed Forces prosecutors had 2.25 years of experience as a prosecutor. (We discuss this review in paragraphs 3.71 and 3.72.) This review recommended that prosecutors stay in their positions for a minimum of 5 years. We found that the length of prosecution experience of military prosecutors had not increased since 2008.

3.55 We found that the Office of the Judge Advocate General’s human resource practices put more emphasis on gaining general legal experience than on developing litigation expertise—that is, court experience for prosecutors or defence counsel.

3.56 While we recognize the value of rotating legal officers to allow them to develop a wide range of experience, in our view the rotation frequency prevents prosecutors and defence counsel from developing the necessary expertise and experience to effectively perform their duties.

3.57 Recommendation. The Judge Advocate General should ensure that its human resource practices support the development of litigation expertise necessary for prosecutors and defence counsel.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Office of the Judge Advocate General is developing better approaches to the posting of legal officers into positions as prosecutors or defence counsel, taking into account operational requirements. The Office of the Judge Advocate General expects to have a policy in place by spring 2019—in advance of the next posting season—mandating five-year-minimum posting periods for legal officers in prosecution and defence counsel positions in order to better develop litigation experience.

In the interim period, the Office of the Judge Advocate General is directly implementing this recommendation. In 2018, most of the legal officers assigned to the Canadian Military Prosecution Service and Defence Counsel Services will remain in their positions (and not be posted elsewhere) to ensure organizational stability and further development of litigation expertise.

Overseeing the administration of the military justice system

The Office of the Judge Advocate General did not provide effective oversight of the military justice system

Overall message

3.58 Overall, we found that the Office of the Judge Advocate General did not provide effective oversight of the military justice system. The Office did not have the information needed to oversee the military justice system, nor did it develop methods to assess performance. The Office of the Judge Advocate General did not implement actions to address many of the problems identified in past external reviews. We also found that it did not analyze how to improve the administration of military justice and it did not conduct the required regular reviews of the military justice system.

3.59 In addition, we found that the Judge Advocate General’s supervision of the Director of Military Prosecutions and the Director of Defence Counsel Services presented a risk to the independence of these two primary positions.

3.60 These findings matter because without effective oversight, problems may not be identified and resolved, which can undermine confidence in the military justice system. Without sufficient information and performance measures, the Canadian Armed Forces cannot assess the efficiency or make informed decisions to improve the military justice system. In addition, independence of both prosecution and defence is an important component of the rule of law.

3.61 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

- Inadequate case management systems and practices

- Inadequate response to past reviews

- Insufficient reviews by the Office of the Judge Advocate General

- Inadequate implementation of a prosecution policy

- Risks to independence

3.62 The Judge Advocate General is responsible for ensuring that the military justice system operates efficiently, effectively, and in accordance with the rule of law. The Office of the Judge Advocate General supports the Judge Advocate General in this role. The Office is responsible for developing legislation, policies, and directives on military justice. It also provides legal advice to military units, and reviews and reports on the military justice system.

3.63 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 3.70, 3.76, 3.82, and 3.86.

3.64 What we examined. We examined the information management systems that stakeholders used to support their decision-making processes and manage their cases. These included databases and documentation practices that the military units and the Office of the Judge Advocate General used to track and monitor military justice cases. We also analyzed how the Canadian Armed Forces responded to military justice system reviews conducted by the Judge Advocate General and external consultants. Finally, we examined how the Judge Advocate General supervised the Director of Military Prosecutions and the Director of Defence Counsel Services.

3.65 Inadequate case management systems and practices. We found that the Office of the Judge Advocate General did not have the information needed to oversee the military justice system. We also found that various stakeholders, notably the Military Police, the Canadian Military Prosecution Service, Defence Counsel Services, and the Office of the Judge Advocate General, had their own case tracking systems that did not capture all the needed information.

3.66 In addition, we found that some military units had no system or process to track and monitor their military justice cases. Where units had their own database, we found the information was often limited, and did not include data on all phases of the military justice process. For example, the tracking documents did not generally include the dates of some important steps—such as the date of the allegations, or the date the case was referred for court martial. Better information about all stages of the process would help the Canadian Armed Forces and the Office of the Judge Advocate General identify when cases appear to be stalled.

3.67 We found that the Office of the Judge Advocate General’s database was incomplete. For example, we found that there were summary trial cases conducted in the 2016–17 fiscal year that were tracked in databases kept by specific military units that were not included in the Office of the Judge Advocate General’s database. We also found that the database was not up to date, as many military units did not provide timely reports on their summary trials. We found that in 23% of the summary trial cases we examined, the military units were late in sending information to the Office of the Judge Advocate General.

3.68 We also found that the Office of the Judge Advocate General’s database included information only on closed cases. It did not contain information on the time taken to complete the various stages of the military justice process. Further, it did not include some important data such as the investigation dates.

3.69 During our audit, the Office of the Judge Advocate General identified requirements for an electronic system to capture relevant data on all military justice cases and generate reports for management. It received approval and funding to launch this project.

3.70 Recommendation. The Canadian Armed Forces should put in place a case management system that contains the information needed to monitor and manage the progress and completion of military justice cases.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. As mentioned at paragraph 3.69, the Office of the Judge Advocate General has received funding for, and is developing, a military justice case management tool and database. This system, which is being called the Justice Administration and Information Management System, or JAIMS, is being developed in the 2018–19 fiscal year in collaboration with the Assistant Deputy Minister (Information Management). It is expected that the JAIMS will be piloted beginning in January 2019 and will be launched in September 2019.

The JAIMS will electronically track discipline files from the receipt of a complaint through to closure of the file. The system will allow military justice stakeholders to access real-time data on files as they progress through the military justice system and will prompt key actors when they are required to take action.

The JAIMS could also be used to require decision makers at various stages to justify why they could not meet time standards, which will assist in identifying and resolving causes for delays.

In addition, by 1 June 2018, the Director of Military Prosecutions will employ a significantly improved electronic database / case management system, designed to better track those files throughout the court martial process that have been referred to the Director of Military Prosecutions. This system will be integrated with the JAIMS when that system is operational.

3.71 Inadequate response to past reviews. The Bronson Consulting Group conducted two reviews of the military justice system in 2008 and 2009. The resulting recommendations included

- developing timelines and practice standards,

- gathering better statistical information and enhancing case management practices,

- ensuring better coordination between stakeholders, and

- ensuring more continuity in legal officer positions.

Recommendations were directed at the Office of the Judge Advocate General and other stakeholders involved in the military justice process. No action plans were developed in response to these recommendations.

3.72 The National Defence Act requires an independent review of the military justice system every seven years. The report of the last independent review was issued in 2011 after the Minister of National Defence had mandated Justice Lesage to review the military justice system. The report reiterated a number of the Bronson Consulting Group’s recommendations. The Office of the Judge Advocate General provided us with its responses to Justice Lesage’s recommendations; however, many of the actions set out in the responses have not been implemented.

3.73 Insufficient reviews by the Office of the Judge Advocate General. The National Defence Act requires the Judge Advocate General to conduct regular reviews of the administration of military justice. We found that the Office of the Judge Advocate General did not do so.

3.74 In May 2016, the Office of the Judge Advocate General initiated a review of the court martial portion of the military justice system. One of its purposes was to assess the efficiency of the court martial system. The review resulted in a draft report in July 2017. After reviewing the draft report, the Office of the Judge Advocate General concluded that it was of limited assistance in assessing the court martial system, largely because of methodology challenges and the lack of metrics and analytics. We reviewed the draft report, and agreed that the review did not adequately assess the efficiency of the court martial process because of weaknesses in its methodology. We found that the results of the review relied heavily on information gathered during interviews and consultations, rather than on data analyses and performance indicators.

3.75 We found that the Office of the Judge Advocate General did not review or study the summary trial processes in the last 10 years.

3.76 Recommendation. The Office of the Judge Advocate General and the Canadian Armed Forces should regularly assess the efficiency and effectiveness of the administration of the military justice system and correct any identified weaknesses.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. In line with the development of the Justice Administration and Information Management System, or JAIMS, the Office of the Judge Advocate General is developing a military justice performance measurement system. This system should begin to collect meaningful data on the military justice system in September 2019. In doing so, this system will enable the assessment of the efficiency and effectiveness of the administration of the military justice system on an ongoing basis. Data analysis will also allow for the identification of system weaknesses and enable targeted measures to address them.

In addition, aside from the ongoing monitoring that will be possible with the performance measurement system, the Office of the Judge Advocate General will undertake periodic and more formal reviews of the military justice system. The first such review will commence by September 2019.

3.77 Inadequate implementation of a prosecution policy. The decision about whether charges proceed to court martial is among the most important steps in the prosecution process. Those decisions involve a high degree of professional judgment, and poor decisions may undermine confidence in the military justice system. The risk is that charges may not go to trial that should have, or that charges go to trial that should not have. The prosecutor has to be independent and free of bias. Considerable care must be taken in each case to ensure fairness and consistency.

3.78 The Director of Military Prosecutions is legally responsible and accountable for ensuring that decisions to proceed to court martial are well founded, made by the right people in the Canadian Military Prosecution Service, and properly documented.

3.79 The Canadian Military Prosecution Service has a policy that governs how decisions are made about whether to proceed to court martial. The policy includes a process to assign cases to prosecutors, along with the authorities they are allowed to exercise. It also includes requirements for documenting certain decisions, including the reasons that support those decisions.

3.80 We found that the Canadian Military Prosecution Service did not develop clear and defined processes to ensure it could implement the policy. Here are some examples:

- The delegation of prosecutorial duties and functions from the Director to individual prosecutors was not always documented.

- The procedure for assigning cases and decision-making authorities to prosecutors was not clear.

- The assignment of cases to prosecutors was not always documented.

3.81 In addition, in response to our questions, the Director of Military Prosecutions acknowledged that when prosecutors were authorized to decide whether to proceed to court martial, they rarely documented their reasons. The Director also acknowledged that when the decision on whether to proceed to court martial required a higher-ranking officer’s approval, neither the recommendation nor the approval was documented. Without this information, the Director cannot monitor and show how prosecutors applied legal principles and exercised professional judgment in each case.

3.82 Recommendation. The Director of Military Prosecutions should ensure that the policies and processes for assigning cases to prosecutors, and for documenting decisions made in military justice cases, are well defined, communicated, and fully implemented by the members of the Canadian Military Prosecution Service.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Director of Military Prosecutions has already made changes to the instruments for the appointment of prosecutors clarifying the limits for the exercise of their prosecutorial powers. The Director of Military Prosecutions has also made changes to better document the assignment of files to prosecutors. These changes will ensure that a proper record is kept of which prosecutor is assigned to the file, by whom the assignment was made, when the assignment took place, and who has final disposition authority in the matter.

Further, the Director of Military Prosecutions will undertake a detailed policy review to be completed by 1 September 2018 to ensure that the policies properly reflect the above-noted changes and that all key decisions taken on a file affecting the disposition of that file are properly documented and communicated.

3.83 Risks to independence. The directors of military prosecutions and defence counsel services are appointed by the Minister of National Defence for a fixed period of time. While they work under the general supervision of the Judge Advocate General, this appointment process is intended to allow those directors to operate with a high degree of independence. It is important to maintain independence so that conflicts do not arise between the duty of prosecutors to act for the public interest and the duty of defence counsel to act in the interest of the accused.

3.84 The Judge Advocate General is responsible for allocating and rotating legal officers within the organization, including to both prosecution and defence services. As a result, both directors do not control their resources independently. In our opinion, this can affect their ability to manage their functions efficiently and effectively.

3.85 We found that the Judge Advocate General did not establish a formal agreement with these directors to define how overall supervision can be exercised without compromising their ability to perform their functions independently. We also found that the Judge Advocate General did not assess whether current practices and processes affect the independence needed by both directors to carry out their distinct roles in the military justice system.

3.86 Recommendation. The Judge Advocate General should assess whether its practices and processes affect the independence of the Director of Military Prosecutions and the Director of Defence Counsel Services, and whether any adjustments or mitigation measures should be established.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. By January 2019, the Office of the Judge Advocate General (JAG) will perform a thorough review of its relationships with the Director of Military Prosecutions and the Director of Defence Counsel Services to ensure their respective independent roles within the military justice system are respected. This will encompass a review of all existing policy directives to the Director of Military Prosecutions and the Director of Defence Counsel Services. In addition, the Office of the Judge Advocate General will continue to ensure that the Director of Military Prosecutions and the Director of Defence Counsel Services have the human resources required to perform their functions.This will include having a policy in place by spring 2019—in advance of the next posting season—mandating five-year-minimum posting periods for legal officers in prosecution and defence counsel positions in order to better develop litigation experience.

In the interim period, the 2018-2021 Office of the JAG Strategic Direction specifically mandates in its mission statement and relevance proposition that the superintendence of the administration of military justice in the Canadian Armed Forces must be accomplished while respecting the independent roles of each statutory actor within the military justice system (which include the Director of Military Prosecutions and the Director of Defence Counsel Services).

Conclusion

3.87 We concluded that the Canadian Armed Forces did not administer the military justice system efficiently. There were delays throughout the various processes for both summary trials and court martial cases. In addition, systemic weaknesses, including the lack of time standards and poor communication, compromised the timely and efficient resolution of military justice cases.

3.88 We also concluded that the Office of the Judge Advocate General did not provide effective oversight of the military justice system and did not have the information needed to adequately oversee the military justice system.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on the administration of the military justice system. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs, and to conclude on whether the Canadian Armed Forces complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard for Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office applies Canadian Standard on Quality Control 1 and, accordingly, maintains a comprehensive system of quality control, including documented policies and procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we have complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit;

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit;

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided; and

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate.

Audit objective

The objective of the audit was to determine whether the Canadian Armed Forces administered the military justice system efficiently.

Scope and approach

The Canadian Armed Forces was the only organization included in this audit.

The audit examined the mechanisms implemented by the Office of the Judge Advocate General to supervise the Director of Military Prosecutions and the Director of Defence Counsel Services. The audit also examined the measures taken by the Canadian Armed Forces to review, assess, and report on the performance of the military justice system, including the availability and the quality of performance indicators and supporting data, and the actions taken based on those reviews and assessments. The audit also examined the measures taken to ensure that the military justice system is supported by the personnel needed.

The audit also examined whether the Canadian Armed Forces applied the rules of the military justice system efficiently. This included an examination of military justice processes and processing times for summary trials and courts martial. We examined a sample of 117 summary trial cases and 20 court martial cases completed in the 2016–17 fiscal year. We selected summary trial cases from a variety of military units with the highest level of military justice activities in different types of operations. With respect to court martial cases, we selected 16 cases randomly, and 4 other cases based on the time required for the case to reach its conclusion.

The audit did not include the following areas:

- adequacy of pretrial custody, detention, and rehabilitation programs;

- implementation of the codes of conduct of the Canadian military colleges;

- administrative corrective measures;

- grievance resolution processes;

- the quality of the legal advice provided by Canadian Armed Forces’ legal officers;

- the exercise of discretion in the laying of charges or decisions to prosecute particular cases;

- the exercise of judicial functions and powers; and

- decisions reached by service tribunals following trials.

Offences related to sexual misconduct were included in the scope of this audit, like any other type of offence within the purview of the military justice system. However, the audit excluded examining the overall strategy and approach to deal with inappropriate sexual behaviour in the Canadian Armed Forces.

Criteria

To determine whether the Canadian Armed Forces administered the military justice system efficiently, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

The roles and responsibilities of the Canadian Armed Forces officials within the military justice system are well defined to support the rule of law. |

|

|

The Canadian Armed Forces measure and evaluate the efficiency and effectiveness of the administration of the military justice and use this information to take action. |

|

|

The Canadian Armed Forces administer the military justice system expeditiously. |

|

|

The Canadian Armed Forces have sufficient trained and professionally developed personnel to administer military justice in an efficient, fair, and impartial manner. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period between 1 April 2011 and 31 March 2017. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 29 March 2018, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

Principal: Andrew Hayes

Director: Chantal Thibaudeau

Shayna Gersher

Pierrick Labbé

Daniel Sipes

Jeff Stephenson

List of Recommendations

The following table lists the recommendations and responses found in this report. The paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report, and the numbers in parentheses indicate the location of the related discussion.

Administering military justice

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

3.31 The Canadian Armed Forces should review its military justice processes to identify the causes of delays and to implement corrective measures to reduce them. (3.14 to 3.30) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. As mentioned at paragraph 3.69, the Office of the Judge Advocate General has received funding for and is developing a military justice case management tool and database. This system, called the Justice Administration and Information Management System, or JAIMS, is being developed in the 2018–19 fiscal year in collaboration with the Assistant Deputy Minister (Information Management). It is expected that the JAIMS will be piloted beginning in January 2019 and will be launched in September 2019. The JAIMS will electronically track discipline files from the receipt of a complaint through to closure of the file. The system will allow military justice stakeholders to access real-time data on files as they progress through the military justice system and will prompt key actors when they are required to take action. It is expected that management of military justice system files with the JAIMS will significantly reduce delays. The JAIMS will also be integrated with a new military justice performance measurement system, expected to be launched concurrently. This system will deliver measurable data on the performance of the military justice system, allowing for the identification of system weaknesses—including in the area of delay—and the development of targeted measures to address them. |

|

3.43 The Canadian Armed Forces should define and communicate time standards for every phase of the military justice process and ensure there is a process for tracking and enforcing them. (3.38 to 3.42) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Office of the Judge Advocate General will conduct a review of time requirements for every phase of the military justice system process. This review will allow for the identification and, by January 2019, the introduction of time standards that would benefit the military justice process in a manner that respects rules of fairness and legal requirements. The Justice Administration and Information Management System, or JAIMS, expected to be operational in September 2019, will incorporate all time standards and will allow for real-time tracking of files as they proceed through the system. The JAIMS will also prompt decision makers when action is required. The military justice performance measurement system, linked to the JAIMS, will deliver data on compliance with time standards. The JAIMS could also be used to require decision makers at various stages to justify why they could not meet time standards, which will assist in identifying and resolving the causes of delays. |

|

3.47 The Canadian Armed Forces should establish formal communication processes to ensure that the Military Police, the Director of Military Prosecutions, the Judge Advocate General’s legal officers, and the military units receive the information that they need to carry out their duties and functions in a timely manner. (3.44 to 3.46) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Military Police Group, the Canadian Military Prosecution Service, legal officers within the Office of the Judge Advocate General, military units, as well as Defence Counsel Services will all have access to the Justice Administration and Information Management System, or JAIMS, which is expected to be operational in September 2019. This will enable decision makers to access real-time information concerning files. In addition, the Office of the Judge Advocate General is undertaking a full review of the policies respecting the disclosure of Military Police reports. This review is expected to be completed by summer 2018 and to be followed by the development of new standards—within the 2018–19 fiscal year—for the timely and complete delivery of these Military Police reports. The re-establishment of the Military Justice Round Table, planned for the spring of 2018, will bring together stakeholders from the Court Martial Appeal Court of Canada, Office of the Chief Military Judge, Office of the Judge Advocate General, Canadian Forces Provost Marshal, Canadian Military Prosecution Service, and Defence Counsel Services to provide a forum to discuss military justice challenges and options to implement best practices. Further, the Director of Military Prosecutions is examining how additional legal support can be provided to the Canadian Forces Military Police Academy in order to facilitate the provision of information between military prosecutors and the Military Police, as well as to assist in the improvement of the quality of future investigations through coordinated training and feedback. It is anticipated that a comprehensive solution to this will be put in place by summer 2019. |

|

3.52 The Canadian Armed Forces should define and communicate expectations for the timely disclosure of all relevant information to members charged with an offence. (3.48 to 3.51) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Office of the Judge Advocate General is conducting a review of timelines for the delivery of disclosure to those charged with an offence. It is expected that this review will be completed by January 2019. The Director of Military Prosecutions has already instituted a number of changes to expedite disclosure to defence counsel. For example, before a file is assigned to a prosecutor, the prosecutor’s supervisor will request disclosure from the appropriate investigative agency. In addition, prosecutors have been instructed to send disclosure to defence counsel once they have received and reviewed it and prior to making a decision (whether to prefer a charge). Further, in spring 2018, the Office of the Judge Advocate General will remind commanding officers of their obligation to immediately inform the Director of Defence Counsel Services of the accused’s decision on whether the accused wishes to be represented by defence counsel. |

|

3.57 The Judge Advocate General should ensure that its human resource practices support the development of litigation expertise necessary for prosecutors and defence counsel. (3.53 to 3.56) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Office of the Judge Advocate General is developing better approaches to the posting of legal officers into positions as prosecutors or defence counsel, taking into account operational requirements. The Office of the Judge Advocate General expects to have a policy in place by spring 2019—in advance of the next posting season—mandating five-year-minimum posting periods for legal officers in prosecution and defence counsel positions in order to better develop litigation experience. In the interim period, the Office of the Judge Advocate General is directly implementing this recommendation. In 2018, most of the legal officers assigned to the Canadian Military Prosecution Service and Defence Counsel Services will remain in their positions (and not be posted elsewhere) to ensure organizational stability and further development of litigation expertise. |

Overseeing the administration of the military justice system

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

3.70 The Canadian Armed Forces should put in place a case management system that contains the information needed to monitor and manage the progress and completion of military justice cases. (3.65 to 3.69) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. As mentioned at paragraph 3.69, the Office of the Judge Advocate General has received funding for, and is developing, a military justice case management tool and database. This system, which is being called the Justice Administration and Information Management System, or JAIMS, is being developed in the 2018–19 fiscal year in collaboration with the Assistant Deputy Minister (Information Management). It is expected that the JAIMS will be piloted beginning in January 2019 and will be launched in September 2019. The JAIMS will electronically track discipline files from the receipt of a complaint through to closure of the file. The system will allow military justice stakeholders to access real-time data on files as they progress through the military justice system and will prompt key actors when they are required to take action. The JAIMS could also be used to require decision makers at various stages to justify why they could not meet time standards, which will assist in identifying and resolving causes for delays. In addition, by 1 June 2018, the Director of Military Prosecutions will employ a significantly improved electronic database / case management system, designed to better track those files throughout the court martial process that have been referred to the Director of Military Prosecutions. This system will be integrated with the JAIMS when that system is operational. |

|

3.76 The Office of the Judge Advocate General and the Canadian Armed Forces should regularly assess the efficiency and effectiveness of the administration of the military justice system and correct any identified weaknesses. (3.71 to 3.75) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. In line with the development of the Justice Administration and Information Management System, or JAIMS, the Office of the Judge Advocate General is developing a military justice performance measurement system. This system should begin to collect meaningful data on the military justice system in September 2019. In doing so, this system will enable the assessment of the efficiency and effectiveness of the administration of the military justice system on an ongoing basis. Data analysis will also allow for the identification of system weaknesses and enable targeted measures to address them. In addition, aside from the ongoing monitoring that will be possible with the performance measurement system, the Office of the Judge Advocate General will undertake periodic and more formal reviews of the military justice system. The first such review will commence by September 2019. |

|

3.82 The Director of Military Prosecutions should ensure that the policies and processes for assigning cases to prosecutors, and for documenting decisions made in military justice cases, are well defined, communicated, and fully implemented by the members of the Canadian Military Prosecution Service. (3.77 to 3.81) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Director of Military Prosecutions has already made changes to the instruments for the appointment of prosecutors clarifying the limits for the exercise of their prosecutorial powers. The Director of Military Prosecutions has also made changes to better document the assignment of files to prosecutors. These changes will ensure that a proper record is kept of which prosecutor is assigned to the file, by whom the assignment was made, when the assignment took place, and who has final disposition authority in the matter. Further, the Director of Military Prosecutions will undertake a detailed policy review to be completed by 1 September 2018 to ensure that the policies properly reflect the above-noted changes and that all key decisions taken on a file affecting the disposition of that file are properly documented and communicated. |

|

3.86 The Judge Advocate General should assess whether its practices and processes affect the independence of the Director of Military Prosecutions and the Director of Defence Counsel Services, and whether any adjustments or mitigation measures should be established. (3.83 to 3.85) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. By January 2019, the Office of the Judge Advocate General (JAG) will perform a thorough review of its relationships with the Director of Military Prosecutions and the Director of Defence Counsel Services to ensure their respective independent roles within the military justice system are respected. This will encompass a review of all existing policy directives to the Director of Military Prosecutions and the Director of Defence Counsel Services. In addition, the Office of the Judge Advocate General will continue to ensure that the Director of Military Prosecutions and the Director of Defence Counsel Services have the human resources required to perform their functions. This will include having a policy in place by spring 2019—in advance of the next posting season—mandating five-year-minimum posting periods for legal officers in prosecution and defence counsel positions in order to better develop litigation experience. In the interim period, the 2018-2021 Office of the JAG Strategic Direction specifically mandates in its mission statement and relevance proposition that the superintendence of the administration of military justice in the Canadian Armed Forces must be accomplished while respecting the independent roles of each statutory actor within the military justice system (which include the Director of Military Prosecutions and the Director of Defence Counsel Services). |