2018 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada Independent Auditor’s ReportReport 4—Replacing Montréal’s Champlain Bridge—Infrastructure Canada

2018 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of CanadaReport 4—Replacing Montréal’s Champlain Bridge—Infrastructure Canada

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- List of Recommendations

- Exhibits:

- 4.1—Premature deterioration of the Champlain Bridge has made significant repair work necessary

- 4.2—The New Champlain Bridge project will link Montréal to the south shore of the St. Lawrence River

- 4.3—Architect’s rendering of the new Champlain Bridge with three decks and cable-stayed structure

- 4.4—The original 2015 costs estimated for the new Champlain Bridge project

- 4.5—Major repair costs for the existing Champlain Bridge have risen sharply

- 4.6—The process of planning for the new Champlain Bridge began late

- 4.7—Technical proposals had to meet mandatory and rated criteria

- 4.8—Stakeholders’ requests triggered some major project changes

- 4.9—The elimination of toll collection had significant implications

Introduction

Background

4.1 In October 2011, the Government of Canada announced construction of a new bridge to replace the existing Champlain Bridge, which links the island of Montréal with the south shore of the St. Lawrence River.

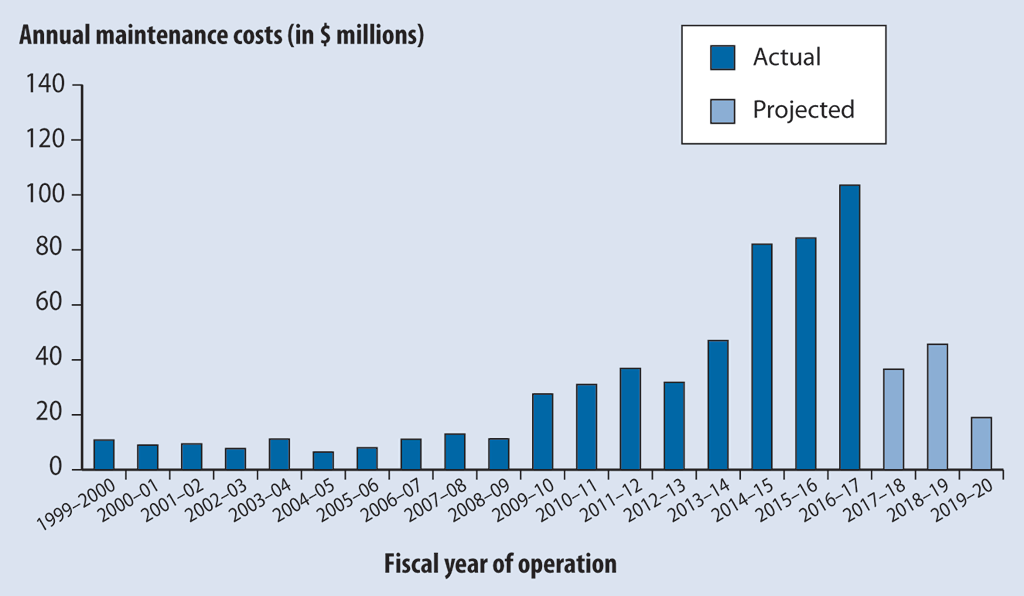

4.2 The existing bridge was less than 50 years old, but it had deteriorated badly. Heavy investments were required to repair and maintain it (Exhibit 4.1). If a structural problem forced the bridge to close, the four other river crossings in the area could not accommodate the displaced traffic without significant congestion. Even partial closures for brief periods or load restrictions could significantly affect the flow of people and goods through the region, and also affect the economy.

Exhibit 4.1—Premature deterioration of the Champlain Bridge has made significant repair work necessary

Photo: The Jacques Cartier and Champlain Bridges IncorporatedInc.

4.3 Since it was established in 1978, The Jacques Cartier and Champlain Bridges Inc. (a Crown corporation) has owned, maintained, and operated the existing bridge. From 1998 to 2014, it was a subsidiary of The Federal Bridge Corporation under the responsibility of the Minister of Transport.

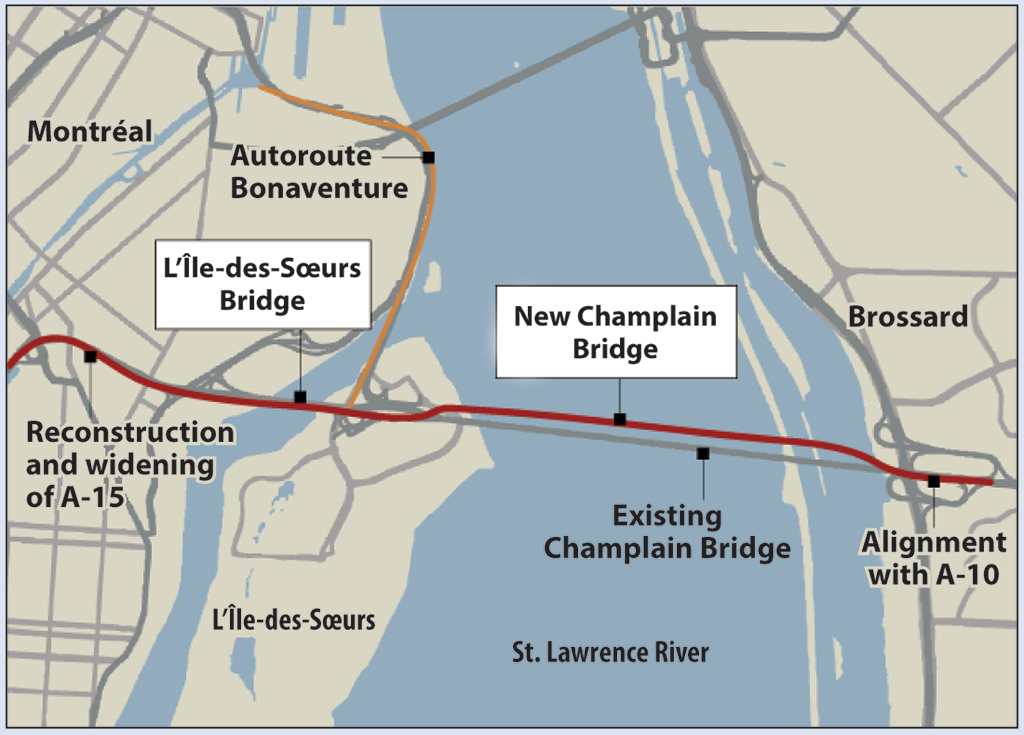

4.4 Project elements. The new Champlain Bridge project (Exhibit 4.2) includes several elements:

- Construction of a replacement for the existing Champlain Bridge (Exhibit 4.3). The new bridge will be a cable-stayed structure that is 3.4 kilometres long. It will have two decks supporting three lanes of highway traffic in each direction; a third, central deck supporting a mass transit system; and a multi-use path.

- Demolition and replacement of L’Île-des-Sœurs Bridge connecting L’Île-des-Sœurs to Montréal. The replacement will be 470 metres long and will include two decks for traffic, as well as a multi-use path.

- Reconstruction and widening of the federal portion of Autoroute 15, with three lanes in each direction.

- Reconstruction of Autoroute 10, and improvement of the ramps on the south shore between Route 132 and Autoroute 10.

Exhibit 4.2—The New Champlain Bridge project will link Montréal to the south shore of the St. Lawrence River

Source: Based on a map from Infrastructure Canada

Exhibit 4.2—text version

This map shows the locations of the existing Champlain Bridge, the new Champlain Bridge, and the L’Île-des-Soeurs Bridge over the St. Lawrence River. Montréal and Autoroute Bonaventure are identified on the Island of Montréal to the north of the Champlain Bridge and west of the St. Lawrence River. The Autoroute Bonaventure connects with the Champlain Bridge on L’Île-des-Soeurs further to the south. Also further south on the Island of Montréal and connected to L’Île-des-Soeurs by the L’Île-des-Soeurs Bridge is the area of planned reconstruction and widening of the A-15 highway. Brossard is identified to the east of the St. Lawrence River, north of where the new Champlain Bridge will align with the A-10 highway.

Exhibit 4.3—Architect’s rendering of the new Champlain Bridge with three decks and cable-stayed structure

Source: Signature on the Saint Lawrence Group

4.5 Private partner. The government signed a contract, dated 16 June 2015, with Signature on the Saint Lawrence Group (the private partner) to complete the new Champlain Bridge project. The private partner undertook to deliver the project for just under $4 billion, excluding the government’s project management and land acquisition costs (Exhibit 4.4). The contract called for the new bridge to be ready for use by 1 December 2018. It included a 42-month construction period and a 30-year operation and maintenance period. After that time, the contract provided for the bridge to be transferred back to the government in a predefined condition. This arrangement was intended to ensure that the private partner used high-quality materials and adequately operated and maintained the bridge. Other sections of the project were scheduled to come into use by 31 October 2019.

Exhibit 4.4—The original 2015 costs estimated for the new Champlain Bridge project

| Type of cost | Amount (in $ millions) |

|---|---|

|

Contract with private partner (Signature on the Saint Lawrence Group): |

|

|

2,246.7 |

|

754.2 |

|

954.2 |

|

22.2 |

|

Total private partner costs |

3,977.3 |

|

Government of Canada:Note 2 |

|

|

158.6 |

|

103.2 |

|

Total government costs |

261.8 |

|

Total costs for the project |

4,239.1 |

Source: Infrastructure Canada

4.6 Project team. To manage the project, an integrated team of officials was drawn from five federal organizations:

- From 2011 to 2014, Transport Canada was responsible for planning for the replacement of the existing Champlain Bridge.

- Infrastructure Canada took over in 2014, when the Minister of Infrastructure was given responsibility for the project. Infrastructure Canada became responsible for all technical matters related to procurement, contracting, and construction.

- Public Services and Procurement Canada was the federal contracting authority for the project. It was responsible for administering the procurement process and managing contracts, including any amendments.

- Public-Private PartnershipsPPP Canada, a Crown corporation, was the commercial and financial adviser to the project team. It played an active role in selecting the private partner, up to the signing of the contract. Its responsibilities for the project ended in May 2017.

- The Department of Justice Canada is the government’s legal adviser on the project.

Focus of the audit

4.7 This audit focused on whether Infrastructure Canada managed selected aspects of the new Champlain Bridge project to meet the objective of delivering a durable bridge on time and in a cost-effective manner.

4.8 This audit is important because the existing Champlain Bridge is a lifeline for residents and businesses in the Greater Montréal area. It accommodates close to 50 million of the 200 million river crossings recorded in the area each year. It also facilitates the movement of imports and exports through the area, with an estimated value of $20 billion every year.

4.9 We did not examine the quality of the construction of the new Champlain Bridge; the management of environmental issues; land acquisitions; contractual agreements other than the one with the selected private partner; the planning for demolition of the existing bridge; or the operation, maintenance, and rehabilitation plan for the new bridge.

4.10 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Planning for the replacement of the existing Champlain Bridge

Overall message

4.11 Overall, we found that the Government of Canada was slow in making the decision to invest in a new bridge instead of maintaining the existing one. This finding matters because the delay in decision making entailed avoidable expenditures of more than $500 million, apart from the economic costs to the Greater Montréal area due to the congestion and load limitations on the existing bridge.

4.12 We also found that Infrastructure Canada completed its analysis of the procurement models for the new Champlain Bridge project two years after it announced the choice of a public-private partnership model. If the Department had thoroughly analyzed the procurement models for the project, it would have found that the public-private partnership could be more expensive than a traditional model.

4.13 For the infrastructure that it owns—including the existing Champlain Bridge—The Jacques Cartier and Champlain Bridges Inc. (JCCBI) is responsible for planning for life-cycle costs and requesting the necessary funding from the minister to whom it reports. The planning must take into account costs of maintaining and operating the infrastructure, and replacing it when the end of its service life is approaching.

4.14 As a subsidiary of The Federal Bridge Corporation (FBCL) from 1998 to 2014, the JCCBI was required to make use of the FBCL’s corporate plan to officially request funding for life-cycle costs. The plan went for review to the minister responsible for the FBCL (then the Minister of Transport), who in turn recommended to the government to approve it.

4.15 In October 2011, the government announced its decision to replace the existing Champlain Bridge. It also stated that the chosen procurement model would be a public-private partnership (P3). A P3 is a contractual agreement between government and the private sector. Under the partnership, the private-sector partner delivers public infrastructure and assumes a major share of the risks in terms of design, construction, operation, and maintenance. This is one of a number of procurement models used by the government. Others include more traditional models such as design-build or design-bid-build.

Delays in decision making added to the overall costs

4.16 We found that the Government of Canada was slow in deciding to replace the existing Champlain Bridge. The decision came in 2011, although the JCCBI had begun studying the possibility of replacing the bridge two years earlier.

4.17 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

4.18 This finding matters because the planning, procurement, and construction of a bridge of this size generally takes about seven years, from the initial decision to the date the bridge comes into use. The delay entailed avoidable expenditures of more than $500 million for the government, as well as economic costs for the Greater Montréal area resulting from truck load limits and lane closures. It is therefore important to make timely decisions in order to avoid significant delays and costs at the end of the service life of a bridge or comparable infrastructure asset. To ensure cost-effectiveness, a best practice is to plan life-cycle costs according to the asset’s remaining service life.

4.19 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 4.29.

4.20 What we examined. We examined whether Infrastructure Canada planned for the cost-effective replacement of the existing Champlain Bridge.

4.21 Deterioration of the existing bridge. The existing bridge came into use in 1962. It deteriorated more quickly than expected, for several reasons:

- It was not resistant to salt corrosion. The use of road salt for de-icing began soon after the bridge opened, accelerating deterioration of the concrete and steel components.

- It was extensively damaged by salt water. It had no drainage system to keep salt water away from the beams.

- It contained key elements that could not be inspected for deterioration. The bridge girders had been designed with embedded pre-stressed cables, but there were no interior sensors to determine the condition of the cables.

- It had not been designed for the volume of heavy truck traffic using the bridge since the 1990s.

4.22 We found that the JCCBI was diligent in inspecting, repairing, and rehabilitating the bridge. From 1986 onward, it undertook major repairs to mitigate serious structural problems, which had increased in number and scope. The problems were abnormal for a bridge of that age. The increasing maintenance costs indicated the severe deterioration of the existing bridge (Exhibit 4.5).

Exhibit 4.5—Major repair costs for the existing Champlain Bridge have risen sharply

Notes:

- Costs from 2015–16 onward ($306 million) could have been avoided with more timely planning for replacement of the bridge.

- The existing bridge will have to be maintained for six months after the new bridge comes into use.

Source: Based on data provided by The Jacques Cartier and Champlain Bridges Inc.

Exhibit 4.5—text version

A review of the total annual maintenance costs for the existing Champlain Bridge since the 1999 to 2000 fiscal year shows sharp increases in costs for the 2009 to 2010, 2014 to 2015, and 2016 to 2017 fiscal years. The maintenance costs projected for the 2017 to 2018, 2018 to 2019, and 2019 to 2020 fiscal years are much lower than those of the past 3 fiscal years.

| Fiscal year of operation | Annual maintenance costs (in millions of dollars) |

|---|---|

| 1999 to 2000 | 10.8 |

| 2000 to 2001 | 9.0 |

| 2001 to 2002 | 9.4 |

| 2002 to 2003 | 7.7 |

| 2003 to 2004 | 11.2 |

| 2004 to 2005 | 6.5 |

| 2005 to 2006 | 8.0 |

| 2006 to 2007 | 11.1 |

| 2007 to 2008 | 13.4 |

| 2008 to 2009 | 11.3 |

| 2009 to 2010 | 27.6 |

| 2010 to 2011 | 31.0 |

| 2011 to 2012 | 36.9 |

| 2012 to 2013 | 31.8 |

| 2013 to 2014 | 47.0 |

| 2014 to 2015 | 82.1 |

| 2015 to 2016 | 84.3 |

| 2016 to 2017 | 103.5 |

| 2017 to 2018 (projected) | 36.6 |

| 2018 to 2019 (projected) | 45.7 |

| 2019 to 2020 (projected) | 19.0 |

Notes:

- Costs from 2015 to 2016 onward ($306 million) could have been avoided with more timely planning for replacement of the bridge.

- The existing bridge will have to be maintained for 6 months after the new bridge comes into use.

Source: Based on data provided by The Jacques Cartier and Champlain Bridges Inc.

4.23 Financial analysis. Starting in the 1980s, concerns were raised about the bridge’s deterioration, and important structural issues were noted between 1999 and 2004. However, we found that it was only in 2004 that the JCCBI developed a financial indicator and target to monitor life-cycle costs for the existing bridge. This was after our 2003 special examination report on the FBCL (available at www.federalbridge.ca), in which we noted that there was no financial analysis. In 2005, the financial indicator showed that life-cycle costs were higher than the target. Subsequently, the JCCBI launched an independent financial analysis to determine whether it was more cost-effective to maintain or replace the existing structure. The analysis was based on an updated service life for the deteriorated exterior girders.

4.24 In February 2006, the JCCBI obtained results of its independent financial analysis. The analysis stated that maintaining and repairing the existing bridge over its remaining service life would cost more than the investment needed to build a new bridge for delivery in 2020.

4.25 Planning delays. As early as 1999, engineers reported the possibility of failure of an exterior girder, a key component of the existing Champlain Bridge. In 2004, the JCCBI expressed concerns in the FBCL’s corporate plan about the shortening of the remaining service life of the existing bridge. However, the JCCBI did not share information about the bridge degradation and structural problems with Transport Canada. Consequently, the government did not begin considering replacement of the existing bridge at that time.

4.26 It was difficult for the JCCBI to appreciate the increasingly rapid deterioration of the existing bridge because it could not determine what was happening inside the bridge girders. It did not fully realize the situation until the 2006–07 fiscal year, when the bridge was in urgent need of unexpected major repairs. In that year, through the FBCL’s corporate plan, the JCCBI officially communicated to the Minister of Transport that replacement would be more cost-effective than continuing to repair the bridge. The corporate plan stated, “The planning for the construction of the new bridge should be put in place now to have an operational crossing by 2021.” However, we found that the JCCBI’s communication did not clearly present the increasingly rapid deterioration of the existing bridge. No funding decision was made at that time.

4.27 In 2007 and 2008, the JCCBI found additional serious structural problems with the existing bridge and communicated them to Transport Canada. In our 2008 special examination report on the FBCL (available at www.federalbridge.ca), we noted the need for the government to provide funding for these pressing repairs ($212 million over a 10-year period). In 2010, the JCCBI obtained the requested funding. Nevertheless, it was only in late 2011 that the government approved the replacement of the bridge with a new structure, initially set for delivery by 2021. This decision marked the start of the planning process. Two years later, in 2013, an accelerated construction schedule of 42 months was adopted and the completion date was advanced to 2018 because of new major structural concerns with the existing bridge.

4.28 In our view, the planning period for replacing the bridge began late (Exhibit 4.6). This was partly because of the JCCBI’s delays in determining life-cycle costs and communicating safety concerns to Transport Canada. Based on the information collected between 1999 and 2006, it would have been judicious for the government to react to the JCCBI’s conclusions presented in the FBCL’s corporate plan for 2006–07, and to start planning for the bridge replacement soon afterward. A new bridge could have been delivered by early 2015 if the JCCBI had provided timely information to Transport Canada, indicating the need to replace the existing bridge. The delays in planning, communicating, and deciding entailed avoidable government expenditures of over $500 million from the 2015–16 fiscal year to the date of delivery of the new bridge: $306 million for major repairs to the existing bridge (detailed in Exhibit 4.5) and $235 million to the private partner for additional resources and transportation costs caused by load restrictions on the existing bridge (detailed in paragraph 4.75). These figures do not consider any financial impacts on users and businesses resulting from the non-availability of part of the existing bridge.

Exhibit 4.6—The process of planning for the new Champlain Bridge began late

| Event | Period | Information provided to decision makers |

Actions taken |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Independent engineers found bridge degradation and structural problems. |

1999 to 2003 |

No information in the FBCL corporate plan |

None |

|

The JCCBI raised concerns that the bridge was reaching the end of its service life more quickly than expected. |

2004 |

Information on the reduction of the bridge’s life expectancy in the FBCL corporate plan |

None |

|

The JCCBI found more structural concerns regarding girder deterioration. It requested an engineering firm to design an emergency truss for possible support of a failing girder. |

2005 |

No information on the emerging girder concerns in the FBCL corporate plan |

None |

|

The JCCBI conducted an independent life-cycle cost analysis for the existing bridge and concluded that maintaining the existing bridge would cost more than building a new bridge by 2021. |

2006 |

Financial analysis results in the FBCL corporate plan |

None |

|

Independent engineers alerted the JCCBI about significant deterioration of the bridge girders. Our special examination report on the FBCL noted an urgent need for additional funding for the JCCBI to mitigate structural problems. |

2007 to 2008 |

Presentations by the JCCBI to Transport Canada’s senior management and the Minister of Transport In the FBCL corporate plan, information on the strategic objective to accelerate the repair program |

The Minister of Transport announced the need to replace the bridge. |

|

Independent engineers alerted the JCCBI about significant deterioration of the bridge and recommended repairing important components, such as the deck, girders, and expansion joints. |

2009 to 2010 |

Information on the 10-year rehabilitation program and replacement feasibility study in the FBCL corporate plan |

None |

|

Independent engineers alerted the JCCBI about additional capacity deficiencies and risks of a collapse. |

2011 |

Presentations by the JCCBI to the FBCL board of directors and to senior management at Transport Canada |

The Government of Canada approved construction of a new bridge, for delivery by 2021. |

|

Pre-construction work began for the new bridge a few months before a girder failed. |

2013 |

Ongoing communications between the JCCBI and the office of the Minister of Transport about the girder failure |

The Minister of Transport announced an accelerated construction schedule, with delivery of the new bridge in 2018. |

Source: Based on planning documents of The Jacques Cartier and Champlain Bridges Inc.

4.29 Recommendation. To avoid service disruptions and unnecessary expenditures, Infrastructure Canada should analyze the life-cycle costs of the infrastructure assets in its portfolio and should plan effectively for timely replacements.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Infrastructure Canada, in its oversight role for the Crown corporations under the Infrastructure and Communities portfolio, which includes The Jacques Cartier and Champlain Bridges Incorporated, will work collaboratively to review the life-cycle asset management.

The decision to proceed with a public-private partnership was based on incomplete information and analyses

4.30 We found that Infrastructure Canada analyzed procurement models two years after the government had decided in favour of a public-private partnership (P3) model. The Department did not base its analysis on reliable data and assumptions, and did not consider all key risks. More thorough analyses would have yielded results indicating that a P3 model could be more expensive than a traditional procurement model.

4.31 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

4.32 This finding matters because decision making must be well-informed to give the best results.

4.33 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 4.44 and 4.45.

4.34 What we examined. We examined Infrastructure Canada’s qualitative analysis for the new Champlain Bridge project, which identified the advantages and disadvantages of a public-private partnership. We also examined the Department’s value-for-money analyses, which compared the costs and benefits of a P3 with a traditional “design-bid-build” procurement model—that is, a model involving different contractors for design and construction, as well as limited risk transfer.

4.35 Timing of the decision. Before deciding on a public-private partnership, federal organizations are required to perform qualitative and value-for-money analyses based on the practices established by PPP Canada. We found that the government selected the P3 model in 2011, before it had completed its analyses.

4.36 Qualitative analysis. In 2014, Infrastructure Canada completed a high-level qualitative analysis for the new Champlain Bridge project. Completing an appropriate qualitative analysis was important because it was supposed to provide a first indication of whether a P3 was the most suitable procurement model. The analysis supported a conclusion in favour of the P3 model, identifying several advantages. From the viewpoint of the Department, one advantage was that the private partner would assume responsibility for more construction- and operation-related risks, such as technical defects, cost overruns, and delays.

4.37 We found that the qualitative analysis was incomplete because the Department did not examine previous construction projects, nor did it analyze other possible forms that a P3 model could take, with varying levels of federal government involvement. Furthermore, the Department did not assess and consider some aspects of the project, particularly

- the difficulties related to undertaking a large construction project in an urban area, involving numerous discussions with municipalities, provincial and federal organizations, and stakeholders; and

- the potential impacts of project changes on the project completion date and related cost increases.

4.38 Value-for-money analyses. In January 2014, the Department finalized a value-for-money analysis to quantify the savings of a P3 model, compared with the traditional procurement model. It conducted the analysis before the financial proposals of the bidders were available. The analysis indicated that a public-private partnership would generate estimated savings of $227 million, compared with a public sector approach. PPP Canada reviewed the analysis and communicated issues and recommendations to Infrastructure Canada. However, the Department did not make all necessary adjustments. We reviewed key variables of the value-for-money analysis and found the following weaknesses:

- Construction costs. The estimated construction costs for the project had a high variability, due to the Department’s use of comparatively imprecise estimates, which were based on a design that was only 5% completed. PPP Canada was concerned about the low level of design completion. Best practices recommend the use of a design that is at least 30% completed for more precise cost estimates, especially when project complexity is high. In other words, the project had not been sufficiently advanced to provide a well-based understanding of the costs. With a design that is only 5% completed, the construction costs may vary up to 30% above the estimate.

- Efficiency rate. An efficiency rate represents cost savings from efficiencies in construction, operation, and maintenance. In a P3, savings usually come from leveraging private-sector experience and expertise. The estimated efficiency rate of 10% was high, compared with the 5% rate recommended by PPP Canada. The higher rate favoured the choice of the P3 model. Experts consulted by PPP Canada did not believe that an efficiency gain would be possible with an accelerated work schedule.

- Project management costs. In 2014, the government estimated that its project management costs would be $15.9 million. In 2015, it revised that estimate to $158.6 million.

- Risk evaluation. The risk evaluation was based on opinions obtained from experts during a workshop, a recognized industry practice. However, their opinions were based on their own expertise and in most cases were not supported by historical data from previous projects. The support of historical data is important for the calculation of plausible risk values, and is also recognized as a best practice. In the risk evaluation, we found some flaws that favoured the P3 model. For example, the risks of late completion and construction cost overruns were not properly evaluated for the P3 model. This is important because, under a P3 model, these risks are, for the most part, transferred to the private sector.

- Discount rate. A discount rate determines the present value of future cash flows. The discount rate of 3.15% used in the analysis was higher than the then-current rate of 2.95%. This is important because a value-for-money analysis varies with different discount rates. In the analysis, the higher discount rate favoured the P3 model.

4.39 As part of the 2014 value-for-money analysis, Infrastructure Canada conducted a sensitivity analysis. This type of analysis determines how the values assigned to different assumptions will lead to different results. The aim is to make decision makers aware of variability in the expected savings of the selected procurement model. We found that the Department’s sensitivity analysis did not use appropriate values for assumptions.

4.40 As part of our audit, we recalculated certain key variables of the value-for-money analysis, using more conservative values for assumptions:

- Construction costs. We recalculated the savings based on construction costs of 30% above the estimate. This value represented the maximum by which actual construction costs might vary from an estimate based on a design that is 5% completed. With costs rising 30% above the estimate, our analysis showed additional costs of $237 million for the P3 model, compared with the traditional model.

- Efficiency rate. We recalculated the savings based on a rate of 5%, as recommended by PPP Canada. Our analysis indicated that the P3 model would cost $26 million more than the traditional model.

4.41 Our recalculations demonstrated that, with more appropriate values for assumptions, a value-for-money analysis might show higher costs associated with the use of a public-private partnership instead of a traditional model.

4.42 In July 2015, Infrastructure Canada updated its value-for-money analysis, which originally showed $227 million in savings for the P3 model. The update was based on the financial proposal of the private partner and updated values for the traditional model, and it was conducted after the contract had been signed. The updated analysis indicated that proceeding with the selected proposal would yield savings of $1.75 billion, compared with the traditional procurement model—that is, $1.5 billion above the estimated savings in the Department’s 2014 analysis. In the updated analysis, however, we found weaknesses favouring the P3 model. For example, the analysis indicated that the value of risks under the traditional procurement model would be six times the value of risks under the P3 model. Similarly, for long-term maintenance, operation, and rehabilitation, the update identified higher costs under the traditional model than under a P3 model. In addition, the discount rate used in the update was higher than the rate in effect at the time of the analysis.

4.43 In our view, the value-for-money analyses were of little use to decision makers because they contained many flaws favouring the P3 model. The project involved significant risks, was of unprecedented size, and required an accelerated schedule. Despite these factors, the values used in the analysis were not sufficiently conservative. The Department indicated that the low construction and financing costs in the private partner proposal could explain higher savings than the original estimates. However, it was unable to fully explain the $1.5-billion difference. In our view, the Department’s analyses indicated savings that were unrealistic.

4.44 Recommendation. Before deciding which procurement model to adopt for future large infrastructure projects, Infrastructure Canada should

- analyze the key project-specific aspects when conducting a qualitative analysis, and evaluate their costs;

- use best practices, sound assumptions, and evidence-based data from relevant past projects to better evaluate the risks and assumptions used in the value-for-money analysis; and

- perform a sound sensitivity analysis to inform decision makers about the variability of expected costs and benefits.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Infrastructure Canada completed a business case, which concluded that the appropriate procurement model for the new Champlain Bridge project was a design-build-finance-operate-maintain contract, a form of public-private partnership widely used in Canada and internationally for large capital projects. The conclusion was based on an analysis of risks determined by experts and the performance of sound sensitivity analysis using best industry practices.

For future large infrastructure projects under its responsibility, Infrastructure Canada will determine

- key project-specific elements,

- risks and assumptions based on data from the new Champlain Bridge project and any other comparable Government of Canada projects, and

- the variability and probability of expected costs and benefits according to best industry practices.

4.45 Recommendation. After completing the construction of the new Champlain Bridge, Infrastructure Canada should create realistic benchmarks for construction costs, risk evaluation, and efficiency rates in value-for-money analyses, for use in future requests for proposals for infrastructure projects.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Infrastructure Canada will examine the development of a benchmark in collaboration with Public Services and Procurement Canada.

The benchmark will be developed against a representative sample of traditionally procured infrastructure projects on cost and time performance indicators.

Management of procurement risks

Overall message

4.46 Overall, we found that Infrastructure Canada evaluated the technical proposals for the construction of the new Champlain Bridge project consistently and fairly. However, the evaluation approach had some flaws. The Department did not sufficiently account for important technical evaluation criteria. Moreover, bidders did not have to demonstrate that they met them.

4.47 Furthermore, after awarding the contract, Infrastructure Canada made several changes to the project, some of them major, to respond to the needs of surrounding communities and stakeholders. The negotiations on these changes, which were ongoing at the time this report was published, have been time-consuming.

4.48 In our view, the private partner will not deliver the new Champlain Bridge within budget. In addition, the delivery of the new bridge on time appears very challenging.

4.49 The new Champlain Bridge project was one of only a few public-private partnership (P3) projects of this complexity and size ever managed by the federal government.

4.50 The procurement process for the project involved two major steps. First, out of six interested consortiums, Infrastructure Canada selected three on the basis of their financial and technical capability. The three consortiums then participated in a second step. This involved submitting detailed technical and financial proposals. After evaluating these, the Department selected the proposal with the lowest bid that satisfied the technical and financial evaluation criteria.

Infrastructure Canada’s approach for evaluating the technical proposals exposed it to risks

4.51 We found that, although Infrastructure Canada evaluated the technical proposals consistently and fairly, its evaluation approach contained flaws that introduced major risks. These included uncertainties about the bidders’ approach related to durability; design; and operation, maintenance, and rehabilitation.

4.52 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topic:

4.53 This finding matters because the federal government was expected to spend around $4.2 billion for the new Champlain Bridge project. Before awarding the contract, it was important for Infrastructure Canada to know the specifics about critical elements of each bidder’s proposal, to minimize risks of cost overruns and delays.

4.54 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 4.62.

4.55 What we examined. We examined the approach for evaluating the technical proposals of the three qualifying bidders that responded to Infrastructure Canada’s July 2014 request for proposals for the new Champlain Bridge project.

4.56 Evaluation approach. The Department developed requirements that bidders had to follow in preparing their technical proposals—for example, specifications for the height clearance of the bridge above high-water levels. The Department worked closely with Public Services and Procurement Canada to develop an approach for evaluating bidders’ technical proposals. It chose an approach that compressed the procurement process so that the selected bidder would be able to proceed quickly with construction. The approach was based on two sets of evaluation criteria published in the request for proposals. To pass the technical evaluation, proposals had to comply with 18 mandatory criteria. In addition, they had to achieve an overall score of at least 21 out of a possible 35 points on seven rated criteria, including at least 3 out of a possible 5 points on two rated criteria (Exhibit 4.7).

Exhibit 4.7—Technical proposals had to meet mandatory and rated criteria

Step 1

Evaluation

Compliance with 18 mandatory technical evaluation criteria related to

- project completion by the target date, and

- inclusion of specific structural and geometric elements

All three proposals submitted met all 18 mandatory criteria and advanced to Step 2.

Step 2

Evaluation

Compliance with 7 rated technical evaluation criteria

Overall pass score: 21 out of a possible 35 points

| Criterion | Score | |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum required | Maximum possible | |

| Time management approach | 3 | 5 |

| Durability approach | 3 | 5 |

| Tolling and technology | not applicableN/A | 5 |

| Design | N/A | 5 |

| Operation, maintenance, and rehabilitation approach | N/A | 5 |

| Management approach | N/A | 5 |

| Construction approach | N/A | 5 |

All three proposals obtained a score of at least 21.

Step 3

Selection

Of the three proposals in Step 2, the one with the lowest financial bid was selected, in accordance with the pre-established rules in the request for proposals.

Source: Based on information provided by Infrastructure Canada.

4.57 We found that the Department had put measures in place to evaluate the technical proposals consistently and fairly. We also found that, of the three proposals considered in Step 2 of Exhibit 4.7, the Department concluded that all had met the mandatory criteria, and that they had obtained at least the minimum score required on two rated criteria and the overall score required for all seven rated criteria. However, in our view, the evaluation did not provide the Department with a sufficient understanding of certain aspects of the bidders’ proposals.

4.58 Of the seven rated criteria, we found that all were assigned the same weight, although some were more important than others. In addition, not all rated criteria had a minimum score requirement. As a result, the Department could not reject technical proposals that scored low on criteria having no minimum score requirement. For example, one bidder proposed a seismic design approach, which was an incorrect interpretation of the technical requirements, and would have required redesign of other bridge elements and could have put the project completion date at risk. Another bidder proposed an incomplete operation, maintenance, and rehabilitation plan. Despite such significant weaknesses, evaluators could not eliminate these proposals.

4.59 Evaluators raised concerns that the weaknesses would adversely affect contract performance if one of the proposals concerned was selected. The proposals passed the technical evaluation because they still met the overall minimum score requirement. In our view, the criteria on design and on operation, maintenance, and rehabilitation should have been given more weight than the other rated criteria, should have been made mandatory, or should have had a minimum score.

4.60 In addition, we found that the Department did not verify whether proposals demonstrated that all important technical requirements had been met. The evaluation approach did not require it to do so. In some instances, the bidders only had to demonstrate their understanding of certain technical requirements. For example, to avoid lengthening the procurement period and adding costs to bidders’ proposals, the Department chose to verify that designs met the expected service life requirement of 125 years after it awarded the contract. Before selecting the successful bidder, it did not obtain any durability analysis—that is, an analysis to determine the probable service life of the structure or its individual components. Without obtaining results of durability analyses in advance, Infrastructure Canada could not know whether the proposed bridge designs would meet the expected service life requirement before it signed a contract with the selected bidder. We found that this approach exposed the government to risks related to the selected bidder’s designs, its compliance with bridge durability requirements, and its maintenance plan.

4.61 We reviewed the durability analyses of the successful bidder and found that they did not fully assess several deterioration mechanisms—for example, frost damage and the compounding effect of all deterioration mechanisms. As a result, we performed comprehensive durability analyses on the designs of key non-replaceable components of the new bridge. In our analysis, we did not find design problems that would affect the examined components’ ability to meet their expected service life.

4.62 Recommendation. When evaluating proposals for public-private partnership contracts under its responsibility, Infrastructure Canada should develop an evaluation approach that includes

- specifying the appropriate weights and minimum scores for assessing important technical project requirements, and

- requiring bidders to provide analysis or evidence that their proposals meet all critical technical requirements.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Infrastructure Canada will work with Public Services and Procurement Canada, as the federal contracting authority for major projects, in the

- development of weighted assessment criteria for the technical project requirements for all future design-and-build projects under its direct responsibility and those of the two Crown corporations under the Infrastructure and Communities portfolio, and

- determination of evidence required to ensure that bidders meet all critical technical requirements.

Costs for the new bridge were higher than planned

4.63 We found that the new Champlain Bridge would cost more than planned. At the time of our audit, the delivery of the new bridge on time appeared very challenging because of transportation delays and unforeseen events, such as labour disputes and strikes. There were major changes to the project during construction, and these were still under negotiation with the private partner when this audit report was published. We found that the changes introduced major additional risks in an already complex project.

4.64 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

4.65 This finding matters because the Government of Canada announced that the new bridge would be constructed on time and in a cost-effective manner.

4.66 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 4.79.

4.67 What we examined. We examined whether Infrastructure Canada managed and monitored the procurement risks to mitigate cost overruns and delays.

4.68 Project changes. We found that Infrastructure Canada implemented a governance framework to mitigate its lack of experience in managing a contract for a large and complex public-private partnership project. For example, the Department maintained a risk register, tasked senior management committees with overseeing project risks, and hired experts to advise on technical matters. In addition, Public Services and Procurement Canada administered the contract amendments resulting from project changes. We found that, while the governance was generally sound, Infrastructure Canada issued more than 20 project change notices, which were accepted by the private partner. Given the aggressive construction schedule, size, and complexity of the new Champlain Bridge project, we also found that the changes introduced additional risks of delays and cost overruns.

4.69 According to PPP Canada, it is not advisable to make extensive changes to a P3 project. Other public-sector organizations that manage P3 projects in Canada limit the number of changes and ensure that they can be completed quickly to avoid the risk of cost increases and delays. Otherwise, changes can erode the projected savings and benefits of a public-private partnership.

4.70 Most of the changes were triggered by third-party requests after the completion of the final design in February 2017. The Department agreed to accommodate requests for the benefit of local residents and stakeholders, and in the interest of supporting urban integration (Exhibit 4.8). However, managing the changes was a complex and time-consuming process for all parties, particularly because other levels of government were involved. While not all of the changes involved significant costs, the real cost was the shift of resources and attention away from the bridge construction. We found that the changes required extensive discussions, reviews of designs, additional resources, estimates of price changes, and negotiations.

Exhibit 4.8—Stakeholders’ requests triggered some major project changes

| Source of request | Change description |

|---|---|

|

Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec, 2016 |

Change the design of the bridge deck to allow for construction of light rail transit. |

|

Municipalities, June 2016 to April 2017 |

Upgrade the model by adding more noise barriers along the highway, to improve noise protection for the cities of Brossard and Montréal. Construct a cycling path and a sidewalk along Gaétan-Laberge Boulevard to improve active transportation in Montréal. Add a fourth lane on L’Île-des-Sœurs Bridge to improve traffic movement onto the island, and make consequent structural changes to the deck drainage system. |

Source: Based on Infrastructure Canada information

4.71 We also found that Infrastructure Canada was slow to finalize the project changes. According to the Department, it followed a thorough approach for analyzing the project changes to ensure that they were technically sound and that prices were reasonable. The private partner had alerted the Department about the growing risk of delays because of the unapproved project changes. However, two years after the start of construction, Infrastructure Canada had still not approved any of the changes. By March 2018, the Department had approved two of the changes.

4.72 In November 2015, the federal government requested the removal of toll collection from the design of the new bridge. We found that this project change had significant implications for the project, and reaching agreement on it proved time-consuming (Exhibit 4.9).

Exhibit 4.9—The elimination of toll collection had significant implications

In 2011, the Government of Canada announced construction of the new Champlain Bridge, with toll collection as a way of recovering costs. The 2015 contract with the private partner included a plan for toll collection.

In November 2015, however, the government decided that the new Champlain Bridge would be toll-free. Shortly after that date, the private partner was instructed to stop all work related to tolling. The parties had to review the contract to identify impacts. On the day of the official announcement that there would be no tolls, Infrastructure Canada communicated its analysis of the impacts of the change to the Minister of Infrastructure. The analysis identified technical, financial, and contractual impacts.

This was a major project change with far-reaching implications:

- The elimination of tolls was expected to increase traffic volumes significantly, by about 20%.

- The parties took longer than expected to review the design of the bridge access ramps in order to determine whether modifications were needed to accommodate the increase in traffic volume.

- The parties had to analyze traffic volumes in a no-toll environment and agree on estimated increases in traffic levels.

- Higher traffic volumes were expected to increase wear and tear on the bridge structure, resulting in higher operation and maintenance costs.

- The elimination of tolls was expected to result in revenue losses of at least $3 billion over the first 30 years of the bridge’s operation.

- The elimination of tolling equipment and associated maintenance costs was projected to yield savings.

In February 2018, the parties reviewed all foreseeable implications of the change so that the contract would adequately reflect them. The discussions were important because, once an agreement was reached between the parties, it would be binding. As of the publication of this audit report, the parties were finalizing negotiations on the mechanism to compensate the private partner for increases in heavy truck traffic, and on the total financial impact of the project change.

Source: Based on information from Infrastructure Canada documents

4.73 Project delays and costs. The private partner faced unforeseen events, such as a labour dispute and strikes by construction workers and engineers of the Quebec public service. There were also transportation challenges due to load restrictions on the Quebec road network and the existing Champlain Bridge. We found that some project risks had materialized and the federal government was assuming more costs than originally planned. This meant that the full expected savings would not be achieved.

4.74 In May 2016, The Jacques Cartier and Champlain Bridges Inc. (JCCBI) decided to limit the transportation of heavy loads on the existing bridge because it was deteriorating rapidly. This had a major impact on the private partner because it had based its construction strategy on the off-site fabrication of hundreds of heavy pieces, along with their transportation on the Quebec road network and over the existing Champlain Bridge to the construction site. As a result of the load restrictions, the private partner claimed that it would incur additional costs and construction delays because of issues related to transporting components for the new bridge.

4.75 In March 2017, the private partner sued the government for $124 million, for additional costs incurred because of restrictions on the transportation of heavy load trucks on the Quebec road network over the existing Champlain Bridge. This lawsuit did not include any amount for the delays resulting from the transportation issues. Later, during the summer of 2017, the private partner reported to the Department that the project was about eight months behind schedule, but that it was still possible to meet the completion deadline through acceleration measures. In March 2018, the Department and the private partner negotiated a global settlement, which included an extension to 21 December 2018 for completing the bridge construction, and an amount of $235 million, of which

- $63 million was for the settlement of all existing claims related to transportation; and

- $172 million was for additional acceleration measures, including the recovery of construction delays. Without these additional measures, the existing Champlain Bridge would have required further investments in major repairs to prolong its service life.

We found that these additional costs would have been avoided had the existing bridge replacement been timely.

4.76 In our opinion, the project will not be delivered within the original budget. Even with additional construction resources or new construction methods, meeting the revised construction completion date of 21 December 2018 appears very challenging.

4.77 In September 2017, the JCCBI studied the impacts of delays in the construction of the new bridge. Its study suggested that additional funds were required to extend the service life of the existing bridge to keep it open until the construction of the new bridge is completed. As such, the JCCBI has budgeted an additional $19 million for maintenance and major repairs in 2019–20, if required. Other factors had the potential to affect the project costs, such as new claims during bridge operation. The Department will not know the final project costs until 30 years after construction is completed, when the private partner turns over the new bridge to the Department.

4.78 We found that the problems we noted in our audit—such as over-optimistic risk evaluation, an accelerated procurement process, and a high number of project changes—are typical problems noted by experts in connection with P3 infrastructure projects in Canada. Lessons learned from the new Champlain Bridge project are important because the government intends to deliver more P3 infrastructure projects in the future.

4.79 Recommendation. In future public-private partnership projects, Infrastructure Canada should minimize the number of project changes and approve them in a timely manner, to reduce the risk of cost overruns and delays.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Infrastructure Canada will continue to work with industry and other key stakeholders to minimize impacts while maximizing benefits for the community. In addition, the Department will apply lessons learned from the new Champlain Bridge project.

Conclusion

4.80 We concluded that Infrastructure Canada did not plan the replacement of the existing Champlain Bridge in a cost-effective manner.

4.81 We also concluded that Infrastructure Canada did not adequately manage selected procurement risks to mitigate cost overruns and delays. Moreover, the private partner’s ability to meet the revised completion date of 21 December 2018 remained uncertain. With respect to the bridge’s durability, the Department had no assurance that the new bridge would meet the expected service life of 125 years at the time it signed the contract with the private partner. However, from our examination of certain components, we found no evidence that the bridge would not last the expected service life.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on the new Champlain Bridge project. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs, and to conclude on whether the new Champlain Bridge project complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard for Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office applies Canadian Standard on Quality Control 1 and, accordingly, maintains a comprehensive system of quality control, including documented policies and procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we have complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit;

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit;

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided; and

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate.

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether Infrastructure Canada managed selected aspects of the new Champlain Bridge project to meet the objective of delivering a durable bridge on time and in a cost-effective manner.

Scope and approach

We audited Infrastructure Canada.

The audit assessed the planning for the replacement of the existing Champlain Bridge. The audit looked at costs of major maintenance repairs of the existing bridge, and the selection of the procurement model to be used for the new Champlain Bridge project.

In addition, the audit assessed the federal government’s analysis and mitigation of key procurement risks. This included the evaluation of the proponents’ technical proposals, as well as the management of project changes. Furthermore, the audit assessed the likelihood that the new bridge would attain the desired 125-year service life.

The audit involved interviewing officials from Infrastructure Canada and other federal government organizations. We also interviewed officials from other levels of government and industry experts to gain insight on best practices. Finally, the audit involved reviewing and analyzing documents provided by Department officials and other project stakeholders.

Criteria

To determine whether Infrastructure Canada managed selected aspects of the new Champlain Bridge project to meet the objective of delivering a durable bridge on time and in a cost-effective manner, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Infrastructure Canada planned the replacement of the existing Champlain Bridge to ensure safety for users in a cost-effective manner. |

Guide to the Management of Real Property, Treasury Board Review of the Governance Framework for Canada’s Crown Corporations, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat Policy Framework for the Management of Assets and Acquired Services, Treasury Board Policy on Investment Planning—Assets and Acquired Services, Treasury Board |

|

Infrastructure Canada selected the procurement model for the new Champlain Bridge based on a sound and reliable analysis to achieve cost-effectiveness. |

P3 Business Case Development Guide, PPP Canada Guideline to Implementing Budget 2011 Direction on Public-Private Partnerships, Treasury Board |

|

Infrastructure Canada managed and monitored key procurement risks for the new Champlain Bridge project to mitigate cost overruns and delays. |

Contracting Policy, Treasury Board Framework for the Management of Risk, Treasury Board |

|

Infrastructure Canada ensured that the accepted designs and construction approach of the private partner for the design and construction of non-replaceable components met minimum technical requirements to achieve an expected service life of 125 years. |

Canadian Highway Bridge Design Code, Canadian Standards Association, 2014 New Bridge for the St. Lawrence Corridor Project Agreement Request for proposals, New Bridge for the St. Lawrence Corridor Project |

|

Infrastructure Canada managed emerging project issues associated with the construction of the new bridge to ensure a timely bridge replacement delivered on budget. |

New Bridge for the St. Lawrence Corridor Project Agreement Request for proposals, New Bridge for the St. Lawrence Corridor Project |

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period between January 2012 and the end of October 2017. However, for the section on planning for the replacement of the existing Champlain Bridge, we also reviewed information covering the period from 1999 to 2011. These are the periods to which the audit conclusion applies.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 18 December 2017, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

Principals: Richard Domingue and Philippe Le Goff

Director: Lucie Talbot

Alexandra Elias-Kapoor

Audrey Garneau

Rose Pelletier

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge the contribution of Nancy Cheng, Assistant Auditor General, to the production of this report.

List of Recommendations

The following table lists the recommendations and responses found in this report. The paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report, and the numbers in parentheses indicate the location of the related discussion.

Planning for the replacement of the existing Champlain Bridge

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

4.29 To avoid service disruptions and unnecessary expenditures, Infrastructure Canada should analyze the life-cycle costs of the infrastructure assets in its portfolio and should plan effectively for timely replacements. (4.16 to 4.28) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. Infrastructure Canada, in its oversight role for the Crown corporations under the Infrastructure and Communities portfolio, which includes The Jacques Cartier and Champlain Bridges Incorporated, will work collaboratively to review the life-cycle asset management. |

|

4.44 Before deciding which procurement model to adopt for future large infrastructure projects, Infrastructure Canada should

|

The Department’s response. Agreed. Infrastructure Canada completed a business case, which concluded that the appropriate procurement model for the new Champlain Bridge project was a design-build-finance-operate-maintain contract, a form of public-private partnership widely used in Canada and internationally for large capital projects. The conclusion was based on an analysis of risks determined by experts and the performance of sound sensitivity analysis using best industry practices. For future large infrastructure projects under its responsibility, Infrastructure Canada will determine

|

|

4.45 After completing the construction of the new Champlain Bridge, Infrastructure Canada should create realistic benchmarks for construction costs, risk evaluation, and efficiency rates in value-for-money analyses, for use in future requests for proposals for infrastructure projects. (4.30 to 4.43) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. Infrastructure Canada will examine the development of a benchmark in collaboration with Public Services and Procurement Canada. The benchmark will be developed against a representative sample of traditionally procured infrastructure projects on cost and time performance indicators. |

Management of procurement risks

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

4.62 When evaluating proposals for public-private partnership contracts under its responsibility, Infrastructure Canada should develop an evaluation approach that includes

|

The Department’s response. Agreed. Infrastructure Canada will work with Public Services and Procurement Canada, as the federal contracting authority for major projects, in the

|

|

4.79 In future public-private partnership projects, Infrastructure Canada should minimize the number of project changes and approve them in a timely manner, to reduce the risk of cost overruns and delays. (4.63 to 4.78) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. Infrastructure Canada will continue to work with industry and other key stakeholders to minimize impacts while maximizing benefits for the community. In addition, the Department will apply lessons learned from the new Champlain Bridge project. |