2018 Fall Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada Independent Auditors’ ReportReport of the Joint Auditors to the Board of Canada Development Investment Corporation—Special Examination—2018

2018 Fall Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of CanadaReport of the Joint Auditors to the Board of Canada Development Investment Corporation—Special Examination—2018

Independent Auditors’ Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- List of Recommendations

- Exhibits:

- 1—Governance—key findings and assessment

- 2—Strategic planning—key findings and assessment

- 3—Corporate risk management—key findings and assessment

- 4—The Canada Hibernia Holding Corporation is one of several investors in the Hibernia offshore oil project, but it does not operate the facilities

- 5—Advice to the Government of Canada on government assets—key findings and assessment

- 6—Canada Hibernia Holding Corporation management—key findings and assessment

- 7—Canada Eldor incorporatedInc. liabilities—key findings and assessment

This report reproduces the special examination report that the joint auditors issued to Canada Development Investment Corporation on 6 June 2018. The Office has not performed follow-up audit work on the matters raised in this reproduced report.

Introduction

Background

1. The Canada Development Investment Corporation (CDEV) is a federal Crown corporation established in 1982 to provide a commercial vehicle for the Government of Canada’s equity investments and to manage the government’s commercial holdings. In 1995, CDEV was directed to wind down its operations by divesting itself of (by selling) its remaining assets. In 2007, however, the Minister of Finance issued a new direction to CDEV. The Minister indicated that it should focus on commercially managing the federal investments that the government had assigned to it. It should also focus on providing advice on government assets as requested by the government while maintaining its capacity to divest those holdings or interests.

2. CDEV is a parent company with three wholly owned subsidiaries:

- The Canada Hibernia Holding Corporation (CHHC) owns and manages the federal government’s investment in the Hibernia offshore oil project. The CHHC is the only active subsidiary of CDEV and the only one with its own employees (five full-time-equivalent positions). It shares ownership of Hibernia with other private and public sector organizations. For Hibernia’s operations, these owners have entered several joint arrangements, which enable the owners to share costs and define responsibilities. The CHHC’s role in the management of Hibernia is further detailed in paragraphs 40 to 43.

- Canada Eldor IncorporatedInc. manages the liabilities of decommissioned uranium mines in Saskatchewan, along with the retirement benefits of some former employees of Eldorado Nuclear Limited, a Crown corporation that originally owned and operated the mine.

- The Canada GEN Investment Corporation was established to hold and manage Canada’s equity interest in the General Motors Company. Since the company’s shares were sold in 2015, the Canada GEN Investment Corporation has had very little activity.

In this report, we refer to this group of companies collectively as “the Corporation.” When findings are specific to a particular company, such as CDEV or the CHHC, we refer to the company.

3. CDEV has two main roles. One is to oversee its subsidiaries—mainly the CHHC, its only active subsidiary. In this role, CDEV is responsible for maintaining a state of readiness to divest the CHHC. The CHHC is the sole revenue stream for CDEV, as CDEV has no government funding through parliamentary appropriations. CDEV’s financial statements include the federal government’s share of the revenue from the Hibernia offshore oil project and the government’s share of the expenses from operating the Hibernia platform. In 2016, CDEV reported gross crude-oil revenues for the CHHC of approximately $224 million and an operating profit of $60 million. The CHHC paid a dividend of $56 million to CDEV, which in turn paid a $51 million dividend to the government. The Corporation also maintains a large cash account, with a balance of about $220 million as of 31 December 2016.

4. CDEV’s other role is to respond to requests from the Government of Canada to analyze government assets—usually requests from the Department of Finance for advice on the evaluation, management, and divesting of the assets. One recent request was to review Canada’s major airports in 2016. Likewise, through the Canada GEN Investment Corporation, CDEV was responsible for the government’s sale of its investment in the General Motors Company in 2010, 2013, and 2015.

5. Because these requests involve large and diverse investments and occur at irregular times, CDEV has adopted a business model of employing only a small number of people and contracting out for much of its analysis.

Focus of the audit

6. Our objective for this audit was to determine whether the systems and practices we selected for examination at the Canada Development Investment Corporation were providing it with reasonable assurance that its assets were safeguarded and controlled, its resources were managed economically and efficiently, and its operations were carried out effectively as required by section 138 of the Financial Administration Act.

7. In addition, section 139 of the Financial Administration Act requires that we state an opinion, with respect to the criteria established, on whether there was reasonable assurance that there were no significant deficiencies in the systems and practices examined. A significant deficiency is reported when the systems and practices examined did not meet the criteria established, resulting in a finding that the Corporation could be prevented from having reasonable assurance that its assets are safeguarded and controlled, its resources are managed economically and efficiently, and its operations are carried out effectively.

8. Based on our assessment of risks, we selected systems and practices in the following areas:

- corporate management practices, and

- management of the Canada Development Investment Corporation.

The selected systems and practices and the criteria used to assess them are found in the exhibits throughout the report.

9. We asked the Audit Committee to confirm the factual accuracy of the audit report. The Committee stated it did not agree that the report was factually accurate.

10. More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and sources of criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Corporate management practices

Except for a significant deficiency in Board appointments and some other improvements needed, the Corporation had good corporate management practices

Overall message

11. Overall, except for a significant deficiency in board appointments, we found that the Canada Development Investment Corporation (CDEV) had good corporate management practices. The significant deficiency related to the fact that the Executive Vice-President had not been appointed by the Governor in Council, despite performing the duties of a president and chief executive officer. We also found weaknesses in four systems and practices:

- board independence,

- risk identification and assessment,

- risk mitigation, and

- risk monitoring and reporting.

12. This finding matters because well-designed corporate management practices provide a sound basis for decision making. They also support transparency and accountability in how a corporation manages and safeguards the government’s resources and assets.

13. Our analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

14. The CDEV’s Board is allowed a president, a chairperson, and six directors. During the period covered by the audit, there was no president and there was a vacancy on the Board. There were also two expired terms for which the members continued to sit on the Board. On 14 December 2017, the Privy Council Office appointed two new members to replace the members who had expired terms.

15. The Board has an Audit Committee, a Nominating and Governance Committee, and a Human Resources and Compensation Committee. Each of the subsidiaries has its own Board of Directors and respective subcommittees. All members of the CDEV Board who were not employees of the organization were also members of the Canada Hibernia Holding Corporation (CHHC) Board.

16. During the period covered by the audit, the Corporation had 12 full-time-equivalent employees and managers, 6 of whom were at the CHHC. During the fall of 2017, the number of full-time equivalents at the CHHC was reduced to 5, as the Chief Executive Officer and the Vice-President of Transportation and Marketing (both working part-time) left the CHHC.

17. Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 21, 27, 34, and 35.

18. Analysis. We looked at governance at both CDEV and the CHHC. While they had in place the elements of good governance, there was a weakness in board independence and a significant deficiency in board appointments (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1—Governance—key findings and assessment

| Systems and practices | Criteria used | Key findings | Assessment against the criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Legend—Assessment against the criteria

Met the criteria

Met the criteria, with improvement needed

Did not meet the criteria |

|||

|

Board independence |

The Board functioned independently. |

The boards functioned independently of management in their decision making. A conflict of interest code applied to board members, who were informed of their obligations under the Conflict of Interest Act. The boards and staff members had a process for making annual declarations of conflicts of interest. Weakness One subsidiary Board member did not share information about potential conflicts of interest with the Board, as required by the Corporation’s code of conduct. |

|

|

Providing strategic direction |

The Board provided strategic direction. |

The Corporation’s strategic objectives were clearly linked to the mandate and were included in the corporate plan. The boards were active in setting up the most-senior officers’ annual objectives, which aligned with the strategic direction and corporate objectives. The boards were active in conducting the annual assessment of the most-senior officers’ performance. |

|

|

Board oversight |

The Board carried out its oversight role over the Corporation. |

Board members made decisions and questioned the Corporation’s strategic information. The boards received appropriate and timely information on financial performance, the status of key operations, and major strategic decisions. |

|

|

Board appointments and competencies |

The Board collectively had capacity and competencies to fulfill its responsibilities. |

The Canada Development Investment Corporation had processes to proactively identify and communicate its Board needs and upcoming vacancies, and to propose candidates. The boards had profiled the skills and expertise needed to be a director of the Corporation. There had been periodic assessments to determine whether the Board membership had the necessary abilities, skills, and knowledge. Board members had access to orientation sessions and ongoing training. Significant deficiency The Executive Vice-President had not been appointed by the Governor in Council but was performing the duties of a president and chief executive officer. |

|

19. Weakness—Board independence. We found that one subsidiary Board member had not declared that he was a member of the board of another organization, as required by the Corporation’s code of conduct. Furthermore, we noted that details about potential conflicts of interest for this individual, included in his declarations, had not been reported to the subsidiary’s Board. Despite these omissions, we found no evidence of any actual conflicts of interest.

20. This weakness matters because the Corporation, though small, is responsible for large investments on the government’s behalf. The outside business interests of Board members must be transparent if the government is to have confidence that they are acting on its behalf.

21. Recommendation. The Corporation should review its processes to ensure that its conflict of interest policy is being followed, particularly so that declarations are reviewed and disclosures are presented to the Board.

The Corporation’s response. Agreed. The Corporation will review its code of conduct policies and reporting requirements therein and will make the necessary modifications to clarify and improve the declaration and reporting process. This will include a review of communication, training, declaration forms, monitoring procedures, and the clarity of expectations. The Corporation plans to complete these improvements by December 2018.

22. Significant deficiency—Board appointments and competencies. We found that the Executive Vice-President (EVP) had not been appointed by the Governor in CouncilDefinition i, but was performing the duties of a president and chief executive officer.

23. CDEV has not had a Governor in Council–appointed president and chief executive officer since 1987. For several years, it had little activity and no employees. In 2005, the Board appointed an Executive Vice-President to help with the increased activities of the Corporation.

24. The Financial Administration Act requires that the president and chief executive officer of a Crown corporation, “by whatever name called,” must be appointed by the Governor in Council. Our analysis of the functions of the Executive Vice-President, as contained in the objectives that have been set, the job profile, terms and conditions of employment, and CDEV’s governance policy, concluded that the responsibilities and duties of the position were those of a president and chief executive officer. CDEV was not in compliance with the Act, as the Executive Vice-President had not been appointed by the Governor in Council.

25. Furthermore, in 2000, the Privy Council Office established guidelines on the salaries of chief executives of Crown corporations, corresponding to the scope of their operations. As there had not been a president and chief executive officer since before the guidelines were in place, CDEV’s Executive Vice-President—though performing the duties of a president and chief executive officer—has never had his salary assessed against them.

26. This deficiency matters because CDEV’s operations and the government’s requirements for Crown corporations have changed significantly since CDEV last had a president and chief executive officer appointed by the Governor in Council. The salary of CDEV’s chief executive has not been subject to the same level of review and approval that is required of other Crown corporations.

27. Recommendation. The Canada Development Investment Corporation should comply with the Financial Administration Act (FAA) requirement for the president and chief executive officer to be appointed by the Governor in Council.

The Board of Directors’ response. Disagreed. In 1995, following the passage of enabling legislation, the Minister of Finance instructed the Board to take steps to wind up CDEV. Notwithstanding the passage of that legislation, authority for the company to fully divest its assets was never received. Since 2007, CDEV has been asked by the government to carry out studies of certain government assets and to manage certain sales processes but the company continues to be without a long-term mandate.

The Board is therefore of the view that, pending receipt of a long-term mandate or instructions to wind up the company, a chief executive officerCEO is unnecessary and CDEV’s needs are adequately served through the role of a part-time EVP to manage day-to-day activities of the corporation and any particular projects assigned by the government. Since the project work is unpredictable, CDEV and the Board are sensitive to managing costs. Having a highly capable, experienced professional willing to work as the EVP on a part-time, variable basis enables the company to keep costs down when project activity is low. CDEV’s shareholder has the authority to appoint a CEO at any time but has chosen not to do so since 1987.

We disagree with the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s (OAG’s) opinion that the EVP has not been properly appointed and that the company is not in compliance with the FAA. In particular, we view the OAG’s opinion as incorrect for the following reasons:

(a) The FAA does not require the appointment of a CEO and CDEV’s articles of incorporation expressly contemplate that CDEV may not have a CEO;

(b) the Board of Directors of CDEV has the authority under CDEV’s by-law and the FAA to appoint the EVP;

(c) the EVP does not perform all of the functions, duties and responsibilities that are typically performed, and are normally expected to be performed, by a CEO. His role as EVP is more operational in nature than a typical CEO and he operates under the direction of the Board, as evidenced by the following:

(i) CDEV has a limited mandate that involves the management of assets and projects but it has very little ability to influence the value of those assets and has no ability to divest those assets or undertake new projects or lines of business without the approval of or a directive from its shareholder—as a result, the long-term strategic perspective required of the CEO role has been considered unnecessary by the Board;

(ii) until recently, the EVP did not have responsibility for oversight of CDEV’s most significant asset, CHHC;

(iii) the EVP’s role is part-time with termination terms unlike that of the full-time employee status of a CEO;

(iv) the EVP performs no strategy-making function and is not expected to do so; and

(v) the EVP does not serve on the Board which is reflective of the fact that his position is something other than a CEO. For corporations in Canada, both public and private, the vast majority of CEOs also serve as board members. In addition, for Crown corporations and publicly traded companies, typically no officers but the CEO are board members (and the FAA precludes any officer other than the CEO from serving on the board of a parent Crown corporation);

(d) the actions of successive governments since 1987 indicate that they have concluded that a CEO is unnecessary for CDEV;

(e) in the absence of an appointment of a CEO by the Governor in Council, the Board still has an obligation under the FAA and Canada Business Corporations Act to manage the business, activities and other affairs of the corporation and to appoint the necessary officers to assist them in satisfying that obligation, which is has carried out by appointing the EVP; and,

(f) the OAG’s opinion would mean, in effect, that notwithstanding that the FAA does not require a CEO and notwithstanding a decision by the Governor in Council and the Board that a CEO of CDEV is not necessary, that CDEV is required to have a CEO at all times, with that person being whoever happens to be the most senior officer of CDEV at that time. This is an illogical interpretation of the FAA as it would impose a management regime on CDEV that is inconsistent with, and contrary to, the FAA and that would constitute an unwarranted lessening of the power of the Board. Taken to its logical extreme, it would lead to the absurd result that an administrative assistant to the Board would, in absence of any other officers or employees of CDEV, be considered the CEO and require appointment by the Governor in Council.

28. Analysis. We looked at strategic planning at both CDEV and the CHHC. We found that they had sound systems and practices in strategic planning (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2—Strategic planning—key findings and assessment

29. Analysis. We looked at risk management at both CDEV and the CHHC. We found that they had good systems and practices to manage risks. However, we found weaknesses in risk assessment, mitigation, monitoring, and reporting (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3—Corporate risk management—key findings and assessment

30. Weaknesses—Corporate risk management. We found that neither CDEV nor the CHHC had a risk management policy or framework in place. Such a framework would include defined risk measurement criteria and tolerance levels, as well as a consistent and systematic approach to monitoring the status of risk mitigation activities.

31. Through an annual assessment, the CHHC identified key risks. These included the environmental and health and safety risks of operating the Hibernia offshore oil project, as well as the risk of the absence or loss of individuals at the CHHC, each of whom represented a large amount of its corporate memory. The CHHC operated largely though joint arrangements with other stakeholders in Hibernia, including arrangements for transportation and storage. Each of these operations carried its own set of risks.

32. The Corporation also defined risk mitigation actions for the identified risks. However, it did not have defined risk tolerance levels to guide risk mitigation decisions. Moreover, it did not have a systematic approach to monitoring and reporting the status of risk mitigation activities throughout the year, including those performed by third parties, to consistently track progress.

33. These weaknesses matter because the Corporation is responsible for advising on and overseeing large operations and transactions. The effects of some of the risks involved, such as a possible oil spill, could be very large. Furthermore, one of the Corporation’s assets is its corporate memory, which resides in a small number of employees and managers.

34. Recommendation. The Corporation should develop a formal risk management policy and framework that supports a consistent approach to identifying, assessing, and monitoring risks, including those of its subsidiaries and its joint arrangements, and define the Corporation’s risk tolerance levels.

35. Recommendation. The Corporation should formally track, monitor, and report on the status of its risk mitigation activities, including those risks applicable to the Canada Hibernia Holding Corporation that may be mitigated and managed by third parties.

The Corporation’s response to both recommendations. Agreed. The Corporation supports effective risk management across the organization. While risks are routinely considered, evaluated, and reported on in the Corporation’s management practices, the Corporation will develop a formalized risk management policy and framework to identify, assess, and monitor risks, and define risk tolerance levels where possible. The Corporation considers that it has a limited ability to control and influence some risks managed and mitigated by third parties. In these cases, management will review and document the extent of applicable risk oversight procedures. The Corporation plans to have this implemented by December 2018.

The Corporation will also implement a more systematic and formalized approach to tracking and monitoring risks as part of its existing review of risks and risk mitigation activities. Improvements will include a revised, improved risk register that formally assigns risk accountabilities to appropriate managers, including the reporting of the status of risk mitigation activities. The reporting will more clearly identify the risk oversight procedures in those areas where the risks are managed and mitigated by third parties. The Corporation plans to have this implemented by December 2018.

Management of the Canada Development Investment Corporation

The Corporation had good systems and practices for managing its operations, but an improvement was needed in operational oversight

Overall message

36. Overall, we found that there were good systems and practices for the management of the Canada Development Investment Corporation (CDEV). However, we found a weakness in the operational oversight of the Canada Hibernia Holding Corporation (CHHC)—specifically, that the CHHC did not have the tools it needed to readily track all of its contractual obligations.

37. This finding matters because the CHHC must ensure that its strategic decisions protect and maximize the government’s investment in the Hibernia offshore oil project.

38. Our analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

- Advice to the Government of Canada on government assets

- Canada Hibernia Holding Corporation management

- Canada Eldor Inc. liabilities

39. Advice to the Government of Canada on government assets. With very few employees, CDEV hires contractors and consultants as financial, legal, and technical advisers to carry out requests from the Government of Canada for advice and assistance on managing government assets. CDEV reports the results to the government; the reports are not made public.

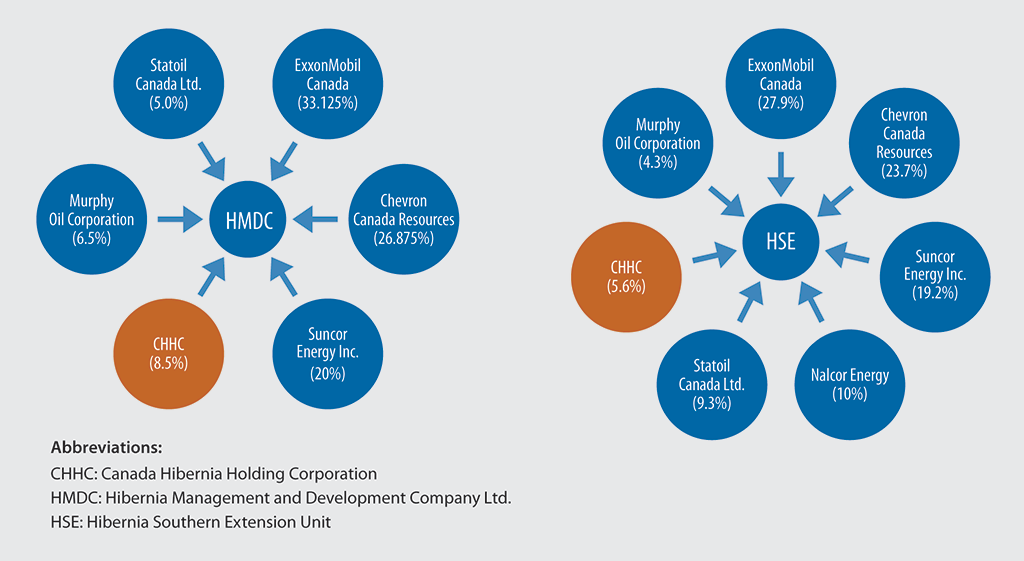

40. Canada Hibernia Holding Corporation management. The CHHC holds investments in the two main components of the Hibernia offshore oil project (Exhibit 4):

- The Hibernia Development Project (8.5%): This is the original Hibernia platform and production, managed through a joint arrangement with six shareholder companies, called the Hibernia Management and Development Company limitedLtd. (HMDC), which conducts oil development and production activities.

- The Hibernia Southern Extension Unit (5.6%): This is a newer, subsea development with tiebacks to the original Hibernia platform. It has seven owners. Facilities, operations, and production services for the Hibernia Southern Extension Unit are managed through the HMDC.

Exhibit 4—The Canada Hibernia Holding Corporation is one of several investors in the Hibernia offshore oil project, but it does not operate the facilities

Source: Based on data from www.hibernia.ca

Exhibit 4—text version

Two diagrams show that the Canada Hibernia Holding Corporation is one of several investors in the two main components of the Hibernia offshore oil project. The two components are Hibernia Management and Development Company limitedLtd., and the Hibernia Southern Extension Unit.

Although the Canada Hibernia Holding Corporation is an investor in both components, it holds the third-lowest share (8.5%) of Hibernia Management and Development Company Ltd. and the second-lowest share (5.6%) of the Hibernia Southern Extension Unit.

The shareholders of Hibernia Management and Development Company Ltd. are as follows, in descending order by the percentage of shares held:

- ExxonMobil Canada (33.125%)

- Chevron Canada Resources (26.875%)

- Suncor Energy incorporatedInc. (20%)

- Canada Hibernia Holding Corporation (8.5%)

- Murphy Oil Corporation (6.5%)

- Statoil Canada Ltd. (5.0%)

The shareholders of the Hibernia Southern Extension Unit are as follows, in descending order by the percentage of shares held:

- ExxonMobil Canada (27.9%)

- Chevron Canada Resources (23.7%)

- Suncor Energy Inc. (19.2%)

- Nalcor Energy (10%)

- Statoil Canada Ltd. (9.3%)

- Canada Hibernia Holding Corporation (5.6%)

- Murphy Oil Corporation (4.3%)

Source: Based on data from www.hibernia.ca

41. Protecting the government’s investment in both of the Hibernia components means not only maximizing its value, but also ensuring that risks are managed. To do this, the CHHC senior management participates in committees of joint owners that oversee compliance with regulations and fulfillment of contractual obligations.

42. In addition to its interests in the overall ownership of Hibernia, the CHHC has entered several joint arrangements for its various operations. For example, the CHHC shares a joint arrangement with all interested holders in oil-production projects in offshore Newfoundland and Labrador to schedule and transport the holders’ crude oil to ports. This joint arrangement enables all the participants to share costs and transportation infrastructure.

43. Furthermore, there are a large number of contractual agreements related to Hibernia operations, ranging from platform operations to governance of the arrangement. The CHHC has responsibilities under these contracts, either as a direct signatory or through its share of ownership in Hibernia. For example, the marketing of oil sales is contracted out to Suncor Energy Inc. CHHC management exercises oversight over these contracts to manage their risks.

44. Canada Eldor Inc. liabilities. In the mid-20th century, Eldorado Nuclear Limited, a Crown corporation, owned and operated uranium mining and processing operations in northern Saskatchewan and Ontario. In 1982, the operations at Uranium City, Saskatchewan, were closed. In 1988, Eldorado Nuclear Limited contributed most of its assets to what would become the Cameco Corporation, in exchange for Cameco Corporation shares. The assets and liabilities not contributed to the Cameco Corporation remained with Eldorado Nuclear Limited, which changed its name to Canada Eldor Inc. As part of this transaction, the Cameco Corporation is the manager of the remaining site-restoration activities at Uranium City, as well as of the defined-benefit obligations for Eldorado Nuclear Limited retirees. Plans for the mine site involve its eventual transfer to the province.

45. Canada Eldor Inc. continues to pay costs related to the decommissioning of the mine site and for retiree benefits of some former employees. Canada Eldor Inc. also contracts an independent consultant to monitor the Cameco Corporation’s performance in managing the mine site.

46. Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 52.

47. Analysis. We found that CDEV had good practices for advising the government on the divestment of selected government assets (Exhibit 5).

Exhibit 5—Advice to the Government of Canada on government assets—key findings and assessment

48. Analysis. We found that the CHHC had good systems and practices for protecting the government’s investment in the Hibernia offshore oil project. However, we found a weakness in the CHHC’s operational oversight (Exhibit 6).

Exhibit 6—Canada Hibernia Holding Corporation management—key findings and assessment

49. Weakness—Operational oversight. The CHHC maintained a repository of its many contracts. Each joint arrangement had multiple contracts and parties; the governance structures for the arrangements varied. Moreover, as these were often long-standing arrangements, some had multiple amendments. Despite the large number of contracts related to Hibernia operations, we found that the CHHC did not have sufficient systems and practices in place to ensure that all the contractual obligations associated with its joint arrangements could be readily identified and monitored. For example, there was no complete listing of all contractual obligations along with milestone dates and names of individuals responsible for oversight.

50. Furthermore, the recent departures of two part-time senior managers further limited the number of the CHHC’s people who had detailed knowledge of the industry and the risks and obligations related to the CHHC’s joint arrangements.

51. This weakness matters because, without practices to ensure that all contractual obligations can be readily documented and monitored, there is a risk that the CHHC might not fulfill some of its obligations, especially as the small number of key resources within the CHHC could further increase its risk during times of transition and turnover.

52. Recommendation. The Canada Hibernia Holding Corporation should develop practices to formally document and monitor contractual obligations related to its joint arrangements.

The Canada Hibernia Holding Corporation’s response. Agreed. The Canada Hibernia Holding Corporation (CHHC) will expand its documentation of contractual obligations to cover all applicable agreements and legislation. The listing will identify the primary individual responsible for oversight of the agreement, and procedures for how and when the obligations will be monitored. In many of the CHHC’s joint arrangements, there are operating companies (for example, the respective legal operators of the Hibernia Development Project and the Hibernia Southern Extension Unit). In these cases, the CHHC only has a general oversight role and cannot directly manage and monitor these third-party contractual obligations. The CHHC expects this large task will take into 2019 to complete; the CHHC will apply a risk-based prioritization to documenting its contractual obligations.

53. Analysis. We found that the Corporation had good practices for managing the government’s responsibilities for existing liabilities and ongoing claims through Canada Eldor Inc. (Exhibit 7).

Exhibit 7—Canada Eldor Inc. liabilities—key findings and assessment

Conclusion

54. In our opinion, based on the criteria established, there was a significant deficiency in the Canada Development Investment Corporation’s board appointments, but there was reasonable assurance there were no significant deficiencies in the other systems and practices that we examined. We concluded that, except for this significant deficiency, the Corporation maintained these systems and practices during the period covered by the audit in a manner that provided the reasonable assurance required under section 138 of the Financial Administration Act.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada and Klynveld Peat Marwick Goerdeler Limited Liability PartnershipKPMG LLP on the Canada Development Investment Corporation (CDEV). Our responsibility was to express

- an opinion on whether there is reasonable assurance that during the period covered by the audit, there were no significant deficiencies in the Corporation’s systems and practices that we selected for examination; and

- a conclusion about whether the Corporation complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

Under section 131 of the Financial Administration Act (FAA), the Canada Development Investment Corporation is required to maintain financial and management control and information systems and management practices that provide reasonable assurance that

- its assets are safeguarded and controlled;

- its financial, human, and physical resources are managed economically and efficiently; and

- its operations are carried out effectively.

In addition, section 138 of the FAA requires the Corporation to have a special examination of these systems and practices carried out at least once every 10 years.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard for Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The joint auditors apply Canadian Standard on Quality Control 1 and, accordingly, maintain a comprehensive system of quality control, including documented policies and procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we have complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from the Corporation’s management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit;

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit; and

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided.

The Canada Development Investment Corporation’s Audit Committee stated that it did not agree the audit report was factually correct.

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether the systems and practices we selected for examination at the Canada Development Investment Corporation were providing it with reasonable assurance that its assets were safeguarded and controlled, its resources were managed economically and efficiently, and its operations were carried out effectively as required by section 138 of the Financial Administration Act.

Scope and approach

Our audit work examined CDEV and its subsidiaries: the Canada Hibernia Holding Corporation (CHHC), Canada Eldor Inc., and the Canada GEN Investment Corporation. The scope of the special examination was based on our assessment of the risks the Corporation faced that could affect its ability to meet the requirements set out by the Financial Administration Act.

In performing our work, we reviewed key documents related to the systems and practices selected for examination. We interviewed members of the CDEV and CHHC boards of directors, senior management, and other employees of the Corporation. We also tested the systems and practices in place to obtain the required level of audit assurance.

The systems and practices selected for examination for each area of the audit are found in the exhibits throughout the report.

In carrying out the special examination, we did not rely on any internal audits.

Sources of criteria

The criteria used to assess the systems and practices selected for examination are found in the exhibits throughout the report.

Governance

Meeting the Expectations of Canadians: Review of the Governance Framework for Canada’s Crown Corporations, Treasury Board Secretariat, 2005

Internal Control—Integrated Framework, Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission, 2013

Corporate Governance in Crown Corporations and Other Public Enterprises—Guidelines, Treasury Board Secretariat, 1996

20 Questions Directors Should Ask about Risk, second edition, Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants, 2006

Performance Management Program for Chief Executive Officers of Crown Corporations—Guidelines, Privy Council Office, 2016

Practice Guide: Assessing Organizational Governance in the Public Sector, The Institute of Internal Auditors, 2014

Strategic planning

Meeting the Expectations of Canadians: Review of the Governance Framework for Canada’s Crown Corporations, Treasury Board Secretariat, 2005

Guidelines for the Preparation of Corporate Plans, Treasury Board Secretariat, 1996

Corporate Governance in Crown Corporations and Other Public Enterprises—Guidelines, Treasury Board Secretariat, 1996

20 Questions Directors Should Ask about Risk, second edition, Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants, 2006

Recommended Practice Guideline 3, Reporting Service Performance Information, International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board, 2015

Corporate risk management

20 Questions Directors Should Ask about Risk, second edition, Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants, 2006

Internal Control—Integrated Framework, Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission, 2013

Corporate Governance in Crown Corporations and Other Public Enterprises—Guidelines, Treasury Board Secretariat, 1996

Advice to the Government of Canada on government assets

Internal Control—Integrated Framework, Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission, 2013

Plan-Do-Check-Act management model adapted from the Deming Cycle

Contracting Policy, Treasury Board, 2013

Good practice contract management framework, National Audit Office, United Kingdom, 2008

Organizational Project Management Capacity Assessment Tool, Treasury Board Secretariat, 2013

Policy on the Management of Projects, Treasury Board, 2009

Mandate of Canada Development Investment Corporation

Corporate Plan 2017–2021, Canada Development Investment Corporation

Corporate Plan 2017–2021, Canada Hibernia Holding Corporation

Canada Hibernia Holding Corporation management

Guidelines for the Preparation of Corporate Plans, Treasury Board Secretariat, 1996

Risk Management: What Boards Should Expect from Chief Financial OfficersCFOs, Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants, 2005

Internal Control—Integrated Framework, Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission, 2013

Plan-Do-Check-Act management model adapted from the Deming Cycle

A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), fifth edition, Project Management Institute Inc., 2013

Policy on the Management of Projects, Treasury Board, 2009

Standard for Project Complexity and Risk, Treasury Board Secretariat, 2010

Control Objectives for Information and related TechnologyCOBIT 5 Framework—APO05 (Manage Portfolio), BAI01 (Manage Programmes and Projects), Information Systems Audit and Control AssociationISACA, 2012

COBIT 5: Enabling Processes, ISACA, 2012

Canada Eldor Inc. liabilities

A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), fifth edition, Project Management Institute Inc., 2013

Policy on the Management of Projects, Treasury Board, 2009

Standard for Project Complexity and Risk, Treasury Board Secretariat, 2010

Plan-Do-Check-Act management model adapted from the Deming Cycle

Period covered by the audit

The special examination covered the period between 1 April 2017 and 11 December 2017. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies. However, to gain a more complete understanding of the significant systems and practices, we also examined certain matters that preceded the starting date of this period.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 28 March 2018, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

Office of the Auditor General of Canada:

Principal: Vicki Clement

Director: Nathalie Desjardins

Marc-André Gervais

Stacey Vukovic

KPMG LLP:

Partner: Nancy Chase

Senior Manager: Clarissa D. Crane

List of Recommendations

The following table lists the recommendations and responses found in this report. The paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report, and the numbers in parentheses indicate the location of the related discussion.

Corporate management practices

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

21. The Corporation should review its processes to ensure that its conflict of interest policy is being followed, particularly so that declarations are reviewed and disclosures are presented to the Board. (19 to 20) |

The Corporation’s response. Agreed. The Corporation will review its code of conduct policies and reporting requirements therein and will make the necessary modifications to clarify and improve the declaration and reporting process. This will include a review of communication, training, declaration forms, monitoring procedures, and the clarity of expectations. The Corporation plans to complete these improvements by December 2018. |

|

27. The Canada Development Investment Corporation should comply with the Financial Administration Act (FAA) requirement for the president and chief executive officer to be appointed by the Governor in Council. (22 to 26) |

The Board of Directors’ response. Disagreed. In 1995, following the passage of enabling legislation, the Minister of Finance instructed the Board to take steps to wind up CDEV. Notwithstanding the passage of that legislation, authority for the company to fully divest its assets was never received. Since 2007, CDEV has been asked by the government to carry out studies of certain government assets and to manage certain sales processes but the company continues to be without a long-term mandate. The Board is therefore of the view that, pending receipt of a long-term mandate or instructions to wind up the company, a CEO is unnecessary and CDEV’s needs are adequately served through the role of a part-time EVP to manage day-to-day activities of the corporation and any particular projects assigned by the government. Since the project work is unpredictable, CDEV and the Board are sensitive to managing costs. Having a highly capable, experienced professional willing to work as the EVP on a part-time, variable basis enables the company to keep costs down when project activity is low. CDEV’s shareholder has the authority to appoint a CEO at any time but has chosen not to do so since 1987. We disagree with the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s (OAG’s) opinion that the EVP has not been properly appointed and that the company is not in compliance with the FAA. In particular, we view the OAG’s opinion as incorrect for the following reasons: (a) The FAA does not require the appointment of a CEO and CDEV’s articles of incorporation expressly contemplate that CDEV may not have a CEO; (b) the Board of Directors of CDEV has the authority under CDEV’s by-law and the FAA to appoint the EVP; (c) the EVP does not perform all of the functions, duties and responsibilities that are typically performed, and are normally expected to be performed, by a CEO. His role as EVP is more operational in nature than a typical CEO and he operates under the direction of the Board, as evidenced by the following: (i) CDEV has a limited mandate that involves the management of assets and projects but it has very little ability to influence the value of those assets and has no ability to divest those assets or undertake new projects or lines of business without the approval of or a directive from its shareholder—as a result, the long-term strategic perspective required of the CEO role has been considered unnecessary by the Board; (ii) until recently, the EVP did not have responsibility for oversight of CDEV’s most significant asset, CHHC; (iii) the EVP’s role is part-time with termination terms unlike that of the full-time employee status of a CEO; (iv) the EVP performs no strategy-making function and is not expected to do so; and (v) the EVP does not serve on the Board which is reflective of the fact that his position is something other than a CEO. For corporations in Canada, both public and private, the vast majority of CEOs also serve as board members. In addition, for Crown corporations and publicly traded companies, typically no officers but the CEO are board members (and the FAA precludes any officer other than the CEO from serving on the board of a parent Crown corporation); (d) the actions of successive governments since 1987 indicate that they have concluded that a CEO is unnecessary for CDEV; (e) in the absence of an appointment of a CEO by the Governor in Council, the Board still has an obligation under the FAA and Canada Business Corporations Act to manage the business, activities and other affairs of the corporation and to appoint the necessary officers to assist them in satisfying that obligation, which is has carried out by appointing the EVP; and, (f) the OAG’s opinion would mean, in effect, that notwithstanding that the FAA does not require a CEO and notwithstanding a decision by the Governor in Council and the Board that a CEO of CDEV is not necessary, that CDEV is required to have a CEO at all times, with that person being whoever happens to be the most senior officer of CDEV at that time. This is an illogical interpretation of the FAA as it would impose a management regime on CDEV that is inconsistent with, and contrary to, the FAA and that would constitute an unwarranted lessening of the power of the Board. Taken to its logical extreme, it would lead to the absurd result that an administrative assistant to the Board would, in absence of any other officers or employees of CDEV, be considered the CEO and require appointment by the Governor in Council. |

|

34. The Corporation should develop a formal risk management policy and framework that supports a consistent approach to identifying, assessing, and monitoring risks, including those of its subsidiaries and its joint arrangements, and define the Corporation’s risk tolerance levels. (30 to 33) 35. The Corporation should formally track, monitor, and report on the status of its risk mitigation activities, including those risks applicable to the Canada Hibernia Holding Corporation that may be mitigated and managed by third parties. (30 to 33) |

The Corporation’s response to both recommendations. Agreed. The Corporation supports effective risk management across the organization. While risks are routinely considered, evaluated, and reported on in the Corporation’s management practices, the Corporation will develop a formalized risk management policy and framework to identify, assess, and monitor risks, and define risk tolerance levels where possible. The Corporation considers that it has a limited ability to control and influence some risks managed and mitigated by third parties. In these cases, management will review and document the extent of applicable risk oversight procedures. The Corporation plans to have this implemented by December 2018. The Corporation will also implement a more systematic and formalized approach to tracking and monitoring risks as part of its existing review of risks and risk mitigation activities. Improvements will include a revised, improved risk register that formally assigns risk accountabilities to appropriate managers, including the reporting of the status of risk mitigation activities. The reporting will more clearly identify the risk oversight procedures in those areas where the risks are managed and mitigated by third parties. The Corporation plans to have this implemented by December 2018. |

Management of the Canada Development Investment Corporation

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

52. The Canada Hibernia Holding Corporation should develop practices to formally document and monitor contractual obligations related to its joint arrangements. (49 to 51) |

The Canada Hibernia Holding Corporation’s response. Agreed. The Canada Hibernia Holding Corporation (CHHC) will expand its documentation of contractual obligations to cover all applicable agreements and legislation. The listing will identify the primary individual responsible for oversight of the agreement, and procedures for how and when the obligations will be monitored. In many of the CHHC’s joint arrangements, there are operating companies (for example, the respective legal operators of the Hibernia Development Project and the Hibernia Southern Extension Unit). In these cases, the CHHC only has a general oversight role and cannot directly manage and monitor these third-party contractual obligations. The CHHC expects this large task will take into 2019 to complete; the CHHC will apply a risk-based prioritization to documenting its contractual obligations. |