2021 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of CanadaReport 3—Access to Safe Drinking Water in First Nations Communities—Indigenous Services Canada

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

- Drinking water advisories in First Nations communities

- Operations and maintenance funding

- Regulatory regime for safe drinking water

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- List of Recommendations

- Exhibits:

Introduction

Background

3.1 Safe drinking water is vital to the health and well-being of all Canadians, including about 330,000 people living in more than 600 First Nations communitiesDefinition 1. Access to safe drinking water can also boost a community’s economic growth and help reduce poverty. However, many First Nations communities live without the assurance that their drinking water is safe.

3.2 Access to safe drinking water is a long-standing issue in many First Nations communities. We previously reported on this issue in 2005 and again in 2011 and provided recommendations to help resolve this issue. Fifteen years after we first examined the issue, some First Nations communities continue to experience a lack of access to safe drinking water.

3.3 In 2015, the federal government promised to address this long-standing issue. It committed to eliminating all long-term drinking water advisories on public water systems on First Nations reserves by 31 March 2021.

3.4 Beginning in the 2016–17 fiscal year, the government allocated more than $2 billion to improve water and wastewater systems in First Nations communities, including funding to operate and maintain public drinking water systems. This targeted funding ends on 31 March 2021. As of 30 November 2020, the department estimated that $1.79 billion had been spent.

3.5 As part of the federal government’s economic update in November 2020, almost $1.5 billion in additional funding starting in the 2020–21 fiscal year was announced. This funding was intended to accelerate the work being done to end all long-term drinking water advisories on public water systems on First Nations reserves, better support the operation and maintenance of water systems, and enable continued program investments in water and wastewater infrastructure. The announcement included an additional $114 million per year starting in the 2026–27 fiscal year for the operation and maintenance of water and wastewater systems.

3.6 The federal government emphasizes the importance of reconciliation and the renewal of a nation-to-nation relationship between Canada and Indigenous communities that is based on the recognition of Indigenous rights, respect, cooperation, and partnership. A key component of reconciliation is to eliminate long-term drinking water advisories on public water systems on First Nations reserves to help ensure access to safe drinking water in First Nations communities and address community infrastructure needs.

3.7 Provinces and territories. Provincial and territorial government regulations apply to almost all public water and wastewater systems in Canada and also provide for enforcement when standards are not met. Although provincial regulations do not apply to First Nations communities, Indigenous Services Canada recommends First Nations communities adhere to the more stringent of federal or provincial requirements.

3.8 Indigenous Services Canada. The department helps to ensure that First Nations communities have access to safe drinking water in a number of ways:

- provides advice and funding to First Nations to design, construct, upgrade, repair, operate, and maintain water systems

- supports drinking water monitoring to determine whether the water is safe

- provides public health advice when there are concerns about drinking water quality and helps communities address these issues

3.9 First Nations. First Nations are the owners and operators of community infrastructure in First Nations communities, including water infrastructure. First Nations manage the construction, upgrade, and day-to-day operations of water systems. They also work to ensure that water systems operate in accordance with various standards, protocols, and guidelines, and that appropriate water testing and monitoring programs are in place.

3.10 The Chiefs and Councils in First Nations communities issue and lift drinking water advisories. Environmental public health officers provide information on drinking water quality and recommend actions to Chiefs and Councils to help inform their decisions. Environmental public health officers are either employed by Indigenous Services Canada or First Nations organizations, such as tribal councils.

3.11 Many First Nations communities rely on multiple water systems for their drinking water. Water systems that serve 5 or more households and those that serve public facilities, such as schools and community centres, are considered to be public systems and are funded by Indigenous Services Canada. Other systems such as wells and cisterns serve individual households and do not receive departmental funding because they are the responsibility of the resident.

3.12 Most First Nations water systems are small, and some are in remote communities that are not always accessible by road. These circumstances present unique challenges, such as managing high capital and operating costs, finding and retaining qualified water system operators, and getting supplies and materials.

3.13 Many First Nations communities are particularly vulnerable to infectious disease outbreaks, such as the virus that causes the coronavirus disease (COVID-19), because of social, environmental, and economic factors. In comparison with other communities, First Nations communities

- more frequently experience overcrowded or poor housing conditions

- have higher rates of pre-existing health conditions and chronic diseases

- have more limited access to health care

3.14 In September 2015, Canada committed to achieving the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. This audit supports the goal of clean water and sanitation (Goal 6), specifically to “ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all” by 2030.

Focus of the audit

3.15 This audit focused on whether Indigenous Services Canada provided adequate support to First Nations communities to ensure that they have access to safe drinking water. We examined the department’s progress against the federal government’s commitment to eliminate all long-term drinking water advisories on public water systems on First Nations reserves by 31 March 2021.

3.16 We also examined whether the department determined and provided the amount of funding necessary to operate and maintain drinking water infrastructure and whether, in collaboration with First Nations, the department made progress in developing a regulatory regime for drinking water in First Nations communities.

3.17 This audit is important because access to safe drinking water is vital to the health and well-being of First Nations communities. Until deficiencies with water systems are addressed and long-term solutions are fully implemented, communities may continue to have challenges accessing safe drinking water.

3.18 In addition, if funding to operate and maintain water systems is insufficient, water systems may continue to deteriorate at a faster-than-expected rate. A regulatory regime for safe drinking water in First Nations communities is important to ensure that First Nations people receive protections comparable with other Canadians.

3.19 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Overall message

3.20 Overall, Indigenous Services Canada did not provide the support necessary to ensure that First Nations communities have ongoing access to safe drinking water. Drinking water advisories remained a constant for many communities, with almost half of the existing advisories in place for more than a decade.

3.21 We found that the department was not on track to meet its target to remove all long-term drinking water advisories on public water systems on First Nations reserves by 31 March 2021. In December 2020, Indigenous Services Canada acknowledged that it would not meet this target. In addition, we found that although interim measures provided affected communities with temporary access to safe drinking water, some long-term solutions were not expected to be completed for several years.

3.22 Indigenous Services Canada’s efforts have been constrained by a number of issues, including an outdated policy and formula for funding the operation and maintenance of water infrastructure.

3.23 No regulatory regime was in place for managing drinking water in First Nations communities. Indigenous Services Canada was working with First Nations to develop a new legislative framework with the goal of supporting the development of a regulatory regime. Such a regime would provide First Nations communities with drinking water protections comparable with other communities in Canada.

3.24 Implementing sustainable solutions requires continued partnership between the department and First Nations. Until these solutions are implemented, First Nations communities will continue to experience challenges in accessing safe drinking water—a basic human necessity.

Drinking water advisories in First Nations communities

3.25 The proper treatment of water is essential to make it safe for drinking, sanitation, and hygiene. When drinking water may be unsafe for consumption or other uses, drinking water advisories are issued. Advisories may be short term, lasting less than 12 months, or long term, lasting 12 months or more.

3.26 Advisories may be issued if there are problems with the water system, such as water line breaks, equipment failure, or poor filtration. An advisory may also be issued if there is no trained operator to run the water system or no trained staff to test drinking water quality.

3.27 As of 1 November 2020, most drinking water advisories in First Nations communities were boil-water advisories. However, some communities were under do-not-consume advisories, which means that even boiled water was unsafe to drink. There were no do-not-use advisories. Do-not-use advisories mean that the water should not be used under any circumstances (Exhibit 3.1).

3.28 In addition to health risks, other negative effects include businesses and services closing temporarily and the subsequent loss of income. Recurring and lengthy advisories may also cause a community to lose confidence in its drinking water quality, which could lead people to turn to unsafe alternative sources, such as untreated lake water, even after the advisory is eliminated.

Exhibit 3.1—Three types of drinking water advisories may be issued to protect public health

| Type of drinking water advisory | Drinking | Washing hands | Bathing | Preparing food | Washing clothing or washing dishes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Boil-water advisory |

Safe |

Safe |

Safe |

Safe |

Safe |

|

Do-not-consume advisory |

Not safe |

Safe |

Safe |

Not safe |

Safe |

|

Do-not-use advisory |

Not safe |

Not safe |

Not safe |

Not safe |

Not safe |

Source: Based on information from Indigenous Services Canada

Indigenous Services Canada did not meet its commitment to eliminate long-term drinking water advisories in First Nations communities

3.29 We found that although Indigenous Services Canada made progress in eliminating long-term drinking water advisories, the department was not on track to meet its 2015 commitment to eliminate all long-term drinking water advisories on public water systems on First Nations reserves by 31 March 2021. We found that, although the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic delayed progress on some projects, many were already facing delays prior to the pandemic.

3.30 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topic:

3.31 This finding matters because if long-term drinking water advisories persist, the health and safety of First Nations communities will be at risk.

3.32 The federal government’s commitment covers public water systems on First Nations reserves—about 1,050 water systems in all. The commitment excludes private wells, cisterns, and homes with no running water, which account for about one third of households on reserves.

3.33 In December 2020, Indigenous Services Canada acknowledged that it would not meet its commitment to eliminate all long-term drinking water advisories on public water systems on First Nations reserves by 31 March 2021.

3.34 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 3.40.

Long-term drinking water advisories still in effect

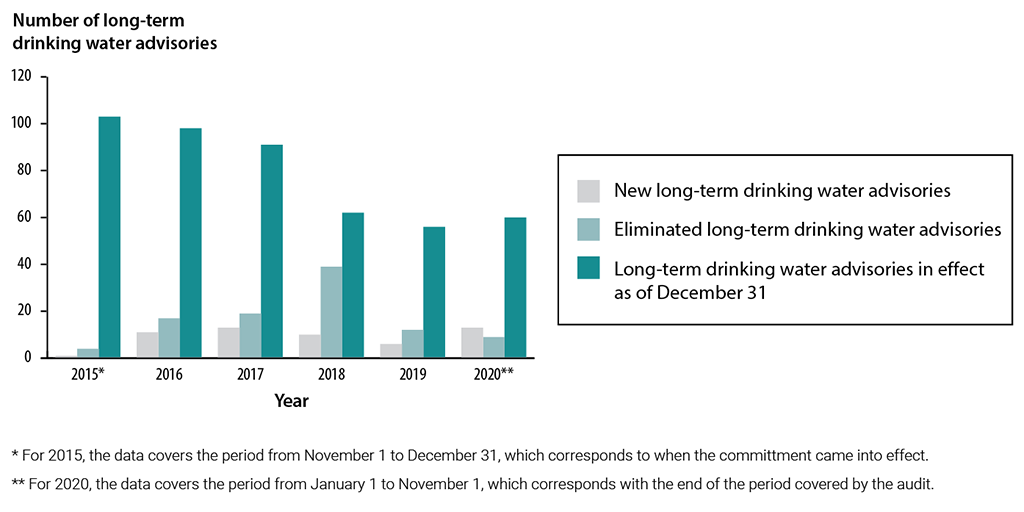

3.35 We found that since the federal government’s commitment in 2015, there were a total of 160 long-term drinking water advisories on public water systems in First Nations communities. As of 1 November 2020, 100 (62.5%) of these long-term advisories had been eliminated and 60 (37.5%) remained in effect in 41 First Nations communities (Exhibit 3.2).

Exhibit 3.2—On 1 November 2020, 60 long-term drinking water advisories were still in effect

Source: Based on data provided by Indigenous Services Canada

Exhibit 3.2—text version

This bar chart shows the number of long-term drinking water advisories for 2015 to 2020. The chart present 3 sets of data for each year:

- the number of new long-term drinking advisories

- the number of eliminated long-term drinking water advisories

- the number of long-term drinking water advisories in effect as of December 31, except for 2020

In 2020, 60 long-term drinking water advisories were still in effect as of November 1.

| Year | Number of new long-term drinking water advisories | Number of eliminated long-term drinking water advisories | Number of long-term drinking water advisories in effect as of December 31, except for 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 1 | 4 | 103 |

| 2016 | 11 | 17 | 98 |

| 2017 | 13 | 19 | 91 |

| 2018 | 10 | 39 | 62 |

| 2019 | 6 | 12 | 56 |

| 2020 | 13 | 9 | 60 as of November 1 |

Please note the following:

- For 2015, the data covers the period from November 1 to December 31, which corresponds to when the commitment came into effect.

- For 2020, the data covers the period from January 1 to November 1, which corresponds with the end of the period covered by the audit.

Source: Based on data provided by Indigenous Services Canada

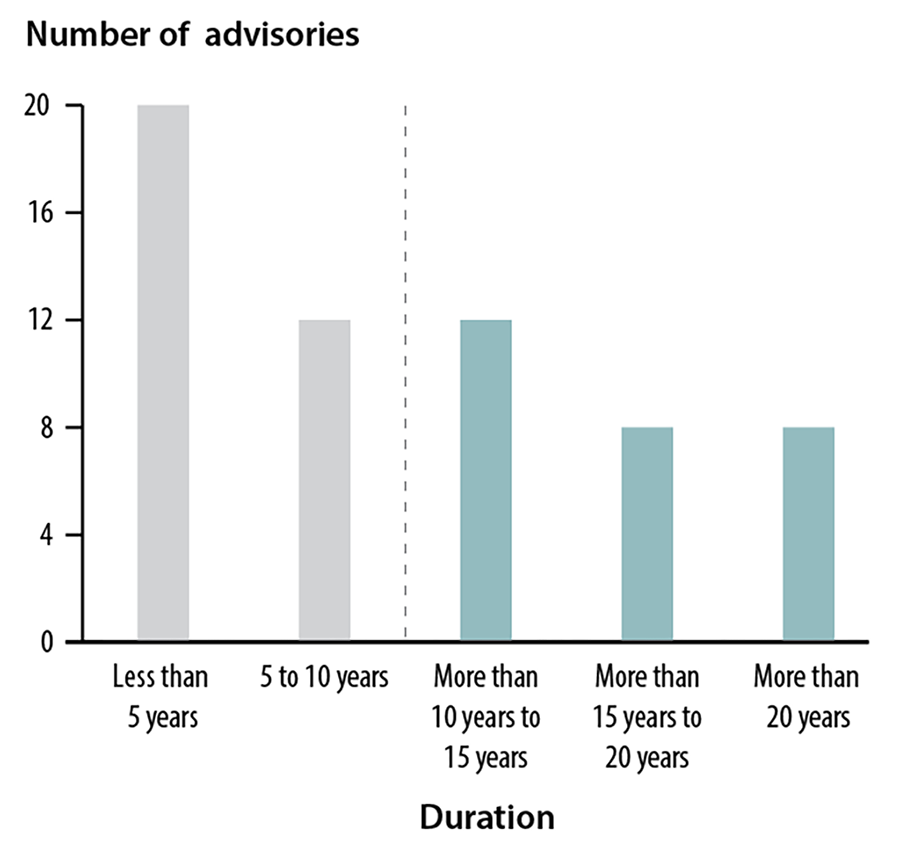

3.36 We found that of the 60 long-term drinking water advisories that remained in effect as of 1 November 2020, almost half (28, or 47%) had been in place for more than a decade (Exhibit 3.3).

Exhibit 3.3—As of 1 November 2020, almost half of the long-term drinking water advisories had been in place for more than a decade

Source: Based on data provided by Indigenous Services Canada

Exhibit 3.3—text version

This bar chart shows the duration of long-term drinking water advisories as of 1 November 2020. Almost half of the advisories—28 out of 60—had been in place for more than a decade.

| Duration | Number of advisories |

|---|---|

| Less than 5 years | 20 |

| 5 to 10 years | 12 |

| More than 10 years to 15 years | 12 |

| More than 15 years to 20 years | 8 |

| More than 20 years | 8 |

Source: Based on data provided by Indigenous Services Canada

3.37 In addition, Indigenous Services Canada indicated that as of 1 November 2020, 2 more short-term drinking water advisories risked surpassing the 1-year mark and becoming long-term drinking water advisories before the 31 March 2021 deadline.

3.38 As of 1 November 2020, the department estimated that 32 (53%) of the remaining 60 long-term drinking water advisories would be eliminated by 31 March 2021. The other 28 (47%) advisories were at risk of surpassing the March 31 deadline. In December 2020, the department acknowledged that it would not meet this deadline. The department expected that most of the 28 advisories could be resolved by September 2021.

3.39 During the pandemic, many First Nations communities limited outside access to their communities to prevent the spread of the virus that causes the coronavirus disease (COVID-19). According to the department, this public health measure had a number of effects, including delays in completing water system infrastructure projects in First Nations communities. However, we found that in many cases, water system projects were already experiencing delays prior to the start of the pandemic.

3.40 Recommendation. Indigenous Services Canada should work with First Nations communities to strengthen efforts to eliminate all long-term drinking water advisories and prevent new ones from occurring.

The department’s response. Agreed. In the Fall Economic Statement 2020, the Government of Canada committed an additional $309 million to continue the work to address all remaining long-term drinking water advisories as soon as possible. Indigenous Services Canada will continue to actively work with First Nations to address drinking water issues, including by assessing the impact of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic on timelines and supporting the advancement of projects in a way that respects public health measures. This work is a continuation of the ongoing strategy to address each and every long-term drinking water advisory on public systems on reserves.

The department will continue to support First Nations to prevent advisories from becoming long term by providing sustainable investments to address short-term advisories, expand delivery systems, build the capacity of and retain local water operators, and support regular monitoring and testing.

The department will continue to advocate for a continuation of program funding with central agencies to ensure continued support for water and wastewater services in First Nations with the objective of obtaining long-term stable funding.

Deficiencies for some water systems had not been addressed

3.41 We found that for some water systems, Indigenous Services Canada supported interim measures to provide access to safe drinking water on a temporary basis. However, long-term solutions to address water system deficiencies still needed to be fully implemented. In some cases, these long-term solutions were not expected to be completed for several years.

3.42 We also found that the duration and frequency of short-term drinking water advisories indicated ongoing issues with a number of water systems. If unaddressed, these issues could undermine communities’ trust in the safety of their drinking water and put residents’ health at risk.

3.43 We found that the condition of water systems in First Nations communities, as measured by annual risk ratings, had not improved between the 2014–15 and the 2019–20 fiscal years.

3.44 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

- Long-term solutions not fully implemented

- Recurring drinking water advisories

- Condition of water systems not improved

3.45 This finding matters because if deficiencies in water systems are not resolved, First Nations communities will not have reliable access to safe drinking water.

3.46 Long-term solutions. When needed, Indigenous Services Canada works with First Nations to implement interim measures to temporarily provide safe drinking water, such as repairs to an existing treatment plant or distribution system. Interim measures provide safe drinking water to affected residents of a community and are designed to eliminate the advisory.

3.47 Long-term solutions are required to address the underlying issue. Long-term solutions may include building a new water treatment plant or upgrading an existing water system. Implementing these long-term solutions can take several years.

3.48 Short-term drinking water advisories. Short-term drinking water advisories are precautionary public health measures that have been in place for less than a year. They are issued when the safety of the drinking water cannot be guaranteed. According to the department, they indicate a temporary water quality issue on a specific water system. Indigenous Services Canada collects data on short-term advisories except for those issued in British Columbia and some parts of Saskatchewan, as this data is managed by First Nations agencies or tribal councils.

3.49 Water systems with recurring and lengthy short-term drinking water advisories may indicate deficiencies that, if unaddressed, could lead to long-term advisories. According to the department, resolving short-term drinking water advisories with lasting solutions is an important part of its overall goal to eliminate long-term drinking water advisories.

3.50 Condition of water systems. The department performs annual risk assessments for all public water systems in First Nations communities. Annual inspections are done to assess each system’s design, how well it is being operated and maintained, the appropriateness of record keeping, the level of water system operators’ training, and the quality of source water. Systems are then categorized into 3 risk categories: high, medium, and low. High- and medium-risk systems have deficiencies that need to be addressed.

3.51 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 3.54 and 3.61.

Long-term solutions not fully implemented

3.52 We found that although interim measures provided affected communities temporary access to safe drinking water, long-term solutions were not expected to be completed for several years. Of the 60 long-term drinking water advisories that remained in effect as of 1 November 2020, 16 (27%) were being addressed through interim measures. According to Indigenous Services Canada, long-term solutions for these systems were in various stages of implementation and were expected to be completed between 2021 and 2025.

3.53 We also found that of the 100 long-term drinking water advisories that were eliminated between 1 November 2015 and 1 November 2020, 15 (15%) were eliminated as a result of interim measures. Of the 15 that were eliminated, long-term solutions were not fully implemented for any of these water systems. Seven (47%) were in the design and feasibility stages, and 8 (53%) were under construction. The department expected that the majority of these projects would be completed between 2022 and 2024.

3.54 Recommendation. Indigenous Services Canada should work with First Nations communities to implement long-term solutions to ensure that water systems in First Nations communities provide ongoing access to safe drinking water.

The department’s response. Agreed. Working with First Nations, Indigenous Services Canada will continue to support long-term measures to ensure that First Nations have ongoing access to safe drinking water.

The department will continue to work with central agencies to ensure that long-term stable funding is available to commit toward these projects and to address the long-term needs of communities.

The department will continue to support operator training and retention and will work with partners to expand capacity building and operator support for First Nations. The department will continue to provide hands-on support to operators through the Circuit Rider Training Program.

Eliminating long-term drinking water advisories is only one aspect of ensuring sustainable access to clean drinking water. Indigenous Services Canada will continue to support First Nations–led engagement processes for the review of the 2013 Safe Drinking Water for First Nations Act with the objective of developing new water legislation accepted by both the federal government and First Nations and for the co-development of a long-term strategy to ensure that drinking water systems are sustainable.

Recurring drinking water advisories

3.55 Long-term drinking water advisories. We found that of the 100 long-term drinking water advisories that were eliminated between 1 November 2015 and 1 November 2020, 5 affected systems had subsequent advisories that became long term. For example, 1 First Nations community had a long-term drinking water advisory in effect since 2001. The advisory was eliminated in 2019 after repairs were made to the treatment plant and distribution system. Yet, less than 2 months later, a subsequent drinking water advisory was issued. This advisory was still in effect on 1 November 2020.

3.56 Short-term drinking water advisories. Short-term drinking water advisories that last for 2 months or longer may indicate underlying water system deficiencies. We found that between 1 November 2015 and 1 November 2020, 1,281 short-term drinking water advisories were issued on public water systems in First Nations communities. Of these, 143 (11%) lasted more than 2 months.

3.57 We also found that some communities experienced recurring short-term advisories. For example, a water system in 1 First Nations community had 31 separate short-term advisories between 1 November 2015 and 1 November 2020, lasting between 2 and 172 days.

3.58 In addition, we found that between 1 November 2015 and 1 November 2020, 19 water systems had recurring short-term drinking water advisories that when combined, lasted for longer than 1 year. For example, 1 community had a short-term advisory for 363 days, followed less than 4 months later by another short-term advisory that lasted for another 325 days. For the residents of this community, the impact of these recurring short-term advisories could be as disruptive as a long-term advisory.

3.59 Although short-term advisories may be a result of routine activities, such as planned maintenance, recurring and lengthy advisories may also indicate underlying issues with water systems that, if unresolved, could undermine a community’s trust in the safety of their drinking water and put their health at risk.

Condition of water systems not improved

3.60 We found that the department’s risk ratings for water infrastructure remained unchanged. In the 2014–15 fiscal year, the department’s annual assessment revealed that 304 (43%) of 699 assessed water systems were either high or medium risk. Five years later in the 2019–20 fiscal year, the same percentage of systems (306 of 718) were still rated as high or medium risk. According to the department, high- and medium-risk systems can have major deficiencies that need to be addressed. If these deficiencies are not addressed, First Nations communities may not have reliable access to safe drinking water.

3.61 Recommendation. Indigenous Services Canada should work with First Nations to proactively identify and address underlying deficiencies in water systems to prevent recurring advisories.

The department’s response. Agreed. Indigenous Services Canada will continue to work with First Nations to conduct performance inspections of water systems annually and asset condition assessments every 3 years to identify deficiencies. The department will proactively work with communities to address those deficiencies and prevent recurring advisories.

Through the funding announced as part of the Fall Economic Statement 2020, the department will further increase support for the operation and maintenance of water systems, enabling First Nations to better sustain their infrastructure. The department will continue to support operator training and retention and will work with partners to expand capacity building and operator support for First Nations. The department will continue to provide hands-on support to operators through the Circuit Rider Training Program.

The department will continue to support the First Nations–led engagement process for the development of a long-term strategy to ensure that drinking water systems are sustainable. Furthermore, the department will continue to support the development of a more holistic asset management approach that allows for better forecasting and the ability to account for future infrastructure investment requirements while engaging on operations and maintenance policy reform.

Operations and maintenance funding

Operations and maintenance policy and funding formula did not reflect First Nations’ needs

3.62 We found that Indigenous Services Canada had not amended the operations and maintenance funding formula for First Nations water systems since it was first developed 30 years ago. Until the formula is updated, it will be unclear whether recent funding increases will be sufficient to allow First Nations to operate and maintain their water infrastructure.

3.63 We also found that a salary gap contributed to problems in retaining qualified water system operators.

3.64 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

3.65 This finding matters because if operations and maintenance funding is insufficient, water-related infrastructure may continue to deteriorate at a faster-than-expected rate, and overall costs may continue to increase as the infrastructure ages.

3.66 In addition, First Nations communities will likely continue to have problems retaining qualified water system operators if there is insufficient funding for their salaries. These factors can put the health of First Nations people at risk.

3.67 Operations refers to the services performed, materials needed, and energy used for the proper day-to-day functioning of a water system. This includes water system operators’ salaries, water treatment chemicals, and electricity costs.

3.68 Maintenance refers to routine maintenance and repairs on a water system to preserve it in as near to its original or renovated condition as is practical.

3.69 Indigenous Services Canada allocates operations and maintenance funds according to a formula and a policy. The formula calculates the overall estimated costs required to operate and maintain water systems. The policy dictates that the department will fund only 80% of these calculated costs. First Nations are expected to cover the remaining 20% through sources such as user fees.

3.70 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 3.77.

Outdated funding formula and policy

3.71 We found that Indigenous Services Canada’s operations and maintenance funding formula was out of date. The formula, which dates back to 1987, was updated annually for inflation but did not keep pace with advances in technology or the actual costs of operating and maintaining infrastructure.

3.72 In addition, the formula did not consider the condition of the infrastructure as determined in annual risk assessments or information about planned maintenance activities. This meant that water systems in greater need of maintenance did not necessarily receive more money from the formula than other systems.

3.73 We also found that the department’s operations and maintenance policy had not been updated since 1998. According to the department, because the formula was outdated, it did not provide the full 80% of costs required by the policy. In addition, many First Nations struggled to provide the remaining 20% of operations and maintenance costs. As a result, the operations and maintenance funding provided to First Nations was insufficient. This contributed to issues with water system operator capacity and accelerated deterioration of water systems.

3.74 In Budget 2019, the department committed targeted operations and maintenance funding for water and wastewater systems. According to the department, this funding was intended to ensure that First Nations received the full 80% of operations and maintenance costs as calculated by the existing formula. The federal government’s Fall Economic Statement 2020 committed additional funding that, according to the department, was intended to ensure that, going forward, First Nations would receive 100% of operations and maintenance costs as calculated by the existing formula.

3.75 Given that the department had not updated its operations and maintenance funding policy or updated the formula used to calculate operations and maintenance costs, it was unclear whether the announced funding increases would be sufficient to allow First Nations to operate and maintain their water infrastructure. The department was working with the Assembly of First Nations to update the operations and maintenance policy.

Challenges in retaining water system operators

3.76 First Nations water system operators’ salaries are included in operations and maintenance funding. We found that the salary gap for water system operators continued to pose problems for First Nations communities. According to a 2018 departmental study, the salaries of water system operators in First Nations communities were 30% lower than their counterparts elsewhere. This salary gap contributed to problems in retaining qualified water system operators. Departmental data for the 2019–20 fiscal year showed that 189 (26%) of 717 public water systems on First Nations reserves lacked a fully trained and certified operator and 401 (56%) of 717 lacked a fully trained and certified back-up operator.

3.77 Recommendation. Indigenous Services Canada, in consultation with First Nations, should make it a priority to

- identify the amount of funding needed by First Nations to operate and maintain drinking water infrastructure

- amend the existing policy and funding formula to provide First Nations with sufficient funding to operate and maintain drinking water infrastructure

The department’s response. Agreed. Indigenous Services Canada will continue to work with First Nations partners to ensure that sufficient water and wastewater operations and maintenance funding is provided and to amend associated policies.

Regulatory regime for safe drinking water

No regulatory regime was in place to help ensure access to safe drinking water in First Nations communities

3.78 We found that there was no regulatory regime to ensure access to safe drinking water in First Nations communities. During our audit period, Indigenous Services Canada was working with First Nations to co-develop a new legislative framework with the goal of supporting the development of a regulatory regime.

3.79 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topic:

3.80 This finding matters because until a regulatory regime is in place, First Nations communities will not have drinking water protections comparable with other communities in Canada where drinking water is regulated.

3.81 Although provinces and territories have their own legally binding safe drinking water protections, First Nations communities do not have comparable legally enforceable protections. Development of legal protections—a regulatory regime—for safe drinking water would include

- parliamentary legislation (an act)

- accompanying regulations developed by Indigenous Services Canada and approved by the Governor in CouncilDefinition 3

3.82 In 2005, we published the Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Chapter 5—Drinking Water in First Nations Communities. In that audit, we found that First Nations communities had no regulatory protections similar to those in the provinces and territories. We recommended that the department develop a regulatory regime for safe drinking water in First Nations communities that included roles and responsibilities, technical requirements, enforcement, and reporting.

3.83 Our follow-up audit was published in our 2011 June Status Report of the Auditor General of Canada, Chapter 4—Programs for First Nations on Reserves. In that audit, we found that the department made some progress in developing a regulatory regime. At that time, the department had drafted a bill to enable regulations for safe drinking water in First Nations communities.

3.84 The Safe Drinking Water for First Nations Act came into force in 2013. It allowed for the development of regulations to ensure access to safe, clean, and reliable drinking water and effective treatment of wastewater on First Nations lands.

3.85 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 3.90.

Ongoing work on new legislative framework

3.86 We found that a regulatory regime was still not in place 15 years after we first recommended it. Although the Safe Drinking Water for First Nations Act came into force in 2013, no supporting regulations were developed.

3.87 First Nations criticized the way the act was developed because of what they considered to be a lack of meaningful engagement and consultation. First Nations also objected to the act because it did not address resource deficiencies to enable them to follow any regulations.

3.88 Indigenous Services Canada acknowledged the importance of a collaborative approach that recognizes First Nations’ rights to self-determination. The department told us that it was working with the Assembly of First Nations to co-develop a new legislative framework to address concerns in the Safe Drinking Water for First Nations Act, with the goal of supporting the development of a regulatory regime.

3.89 Until a regulatory regime is in place that is comparable with those in provinces and territories, First Nations communities will not have the same drinking water protections as other communities in Canada.

3.90 Recommendation. Indigenous Services Canada, in consultation with First Nations, should develop and implement a regulatory regime for safe drinking water in First Nations communities.

The department’s response. Agreed. Indigenous Services Canada will continue to support the Assembly of First Nations in its lead role in the engagement process. The department will continue to work collaboratively and in full partnership with the Assembly of First Nations, other First Nations and First Nations organizations, and other federal departments to develop a legislative framework that can be presented to Cabinet. Once new legislation is passed, regulations can be developed.

Conclusion

3.91 We concluded that Indigenous Services Canada did not provide adequate support to First Nations communities so that they have access to safe drinking water. Until deficiencies with water systems are addressed, sufficient operations and maintenance funding is identified and provided, and a regulatory regime is established, First Nations communities will not have reliable access to safe drinking water. Identifying and implementing sustainable solutions will require continued partnership with First Nations to resolve outstanding issues and other factors that prevent reliable access to safe drinking water.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on access to safe drinking water in First Nations communities. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs, and to conclude on whether the support provided to First Nations communities by Indigenous Services Canada for safe drinking water complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements, set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada applies the Canadian Standard on Quality Control 1 and, accordingly, maintains a comprehensive system of quality control, including documented policies and procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether Indigenous Services Canada provided adequate support to First Nations communities so that they have access to safe drinking water.

Scope and approach

The audit focused on Indigenous Services Canada’s activities regarding the safety of drinking water in First Nations communities. The audit team interviewed departmental managers and staff in the Regional Operations Sector and the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch. We conducted quantitative analysis of drinking water advisory data for those that were either in place or issued and eliminated between 1 November 2015 and 1 November 2020. The purpose of this analysis was to determine the department’s progress in eliminating long-term drinking water advisories in First Nations communities. We examined whether the funding for First Nations to operate and maintain water systems in their communities was sufficient. In addition, we reviewed the department’s progress in developing a regulatory regime for safe drinking water in First Nations communities. The audit team also met with selected key First Nations stakeholders to discuss issues related to access to safe drinking water. However, because of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, we did not visit First Nations communities during our audit.

We did not examine the performance of First Nations communities, First Nations organizations, or other federal departments. We also did not examine water quality monitoring, capacity development, or capital funding programs.

Criteria

We used the following criteria to determine whether Indigenous Services Canada provided adequate support to First Nations communities so that they have access to safe drinking water:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Indigenous Services Canada is on track to meet its commitment to eliminate all long-term drinking water advisories on public water systems on First Nations reserves by 31 March 2021. |

|

|

Indigenous Services Canada has identified and provided the amount of funding to First Nations necessary to operate and maintain drinking water infrastructure in accordance with all relevant policies, guidelines, protocols, and service standards. |

|

|

Indigenous Services Canada has made progress, in collaboration with First Nations communities, in developing a regulatory regime for drinking water in First Nations communities. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period from 1 November 2015 to 1 November 2020. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies. However, to gain a more complete understanding of the subject matter of the audit, we also examined certain matters that preceded the start date of this period.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 18 December 2020, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

Principal: Glenn Wheeler

Director: Doreen Deveen

Samira Drapeau

Valérie La France-Moreau

Maxine Leduc

Joseph O’Brien

List of Recommendations

The following table lists the recommendations and responses found in this report. The paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report, and the numbers in parentheses indicate the location of the related discussion.

Drinking water advisories in First Nations communities

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

3.40 Indigenous Services Canada should work with First Nations communities to strengthen efforts to eliminate all long-term drinking water advisories and prevent new ones from occurring. (3.35 to 3.39) |

The department’s response. Agreed. In the Fall Economic Statement 2020, the Government of Canada committed an additional $309 million to continue the work to address all remaining long-term drinking water advisories as soon as possible. Indigenous Services Canada will continue to actively work with First Nations to address drinking water issues, including by assessing the impact of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic on timelines and supporting the advancement of projects in a way that respects public health measures. This work is a continuation of the ongoing strategy to address each and every long-term drinking water advisory on public systems on reserves. The department will continue to support First Nations to prevent advisories from becoming long term by providing sustainable investments to address short-term advisories, expand delivery systems, build the capacity of and retain local water operators, and support regular monitoring and testing. The department will continue to advocate for a continuation of program funding with central agencies to ensure continued support for water and wastewater services in First Nations with the objective of obtaining long-term stable funding. |

|

3.54 Indigenous Services Canada should work with First Nations communities to implement long-term solutions to ensure that water systems in First Nations communities provide ongoing access to safe drinking water. (3.52 to 3.53) |

The department’s response. Agreed. Working with First Nations, Indigenous Services Canada will continue to support long-term measures to ensure that First Nations have ongoing access to safe drinking water. The department will continue to work with central agencies to ensure that long-term stable funding is available to commit toward these projects and to address the long-term needs of communities. The department will continue to support operator training and retention and will work with partners to expand capacity building and operator support for First Nations. The department will continue to provide hands-on support to operators through the Circuit Rider Training Program. Eliminating long-term drinking water advisories is only one aspect of ensuring sustainable access to clean drinking water. Indigenous Services Canada will continue to support First Nations–led engagement processes for the review of the 2013 Safe Drinking Water for First Nations Act with the objective of developing new water legislation accepted by both the federal government and First Nations and for the co-development of a long-term strategy to ensure that drinking water systems are sustainable. |

|

3.61 Indigenous Services Canada should work with First Nations to proactively identify and address underlying deficiencies in water systems to prevent recurring advisories. (3.55 to 3.60) |

The department’s response. Agreed. Indigenous Services Canada will continue to work with First Nations to conduct performance inspections of water systems annually and asset condition assessments every 3 years to identify deficiencies. The department will proactively work with communities to address those deficiencies and prevent recurring advisories. Through the funding announced as part of the Fall Economic Statement 2020, the department will further increase support for the operation and maintenance of water systems, enabling First Nations to better sustain their infrastructure. The department will continue to support operator training and retention and will work with partners to expand capacity building and operator support for First Nations. The department will continue to provide hands-on support to operators through the Circuit Rider Training Program. The department will continue to support the First Nations–led engagement process for the development of a long-term strategy to ensure that drinking water systems are sustainable. Furthermore, the department will continue to support the development of a more holistic asset management approach that allows for better forecasting and the ability to account for future infrastructure investment requirements while engaging on operations and maintenance policy reform. |

Operations and maintenance funding

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

3.77 Indigenous Services Canada, in consultation with First Nations, should make it a priority to

|

The department’s response. Agreed. Indigenous Services Canada will continue to work with First Nations partners to ensure that sufficient water and wastewater operations and maintenance funding is provided and to amend associated policies. |

Regulatory regime for safe drinking water

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

3.90 Indigenous Services Canada, in consultation with First Nations, should develop and implement a regulatory regime for safe drinking water in First Nations communities. (3.86 to 3.89) |

The department’s response. Agreed. Indigenous Services Canada will continue to support the Assembly of First Nations in its lead role in the engagement process. The department will continue to work collaboratively and in full partnership with the Assembly of First Nations, other First Nations and First Nations organizations, and other federal departments to develop a legislative framework that can be presented to Cabinet. Once new legislation is passed, regulations can be developed. |