2021 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of CanadaReport 8—Pandemic Preparedness, Surveillance, and Border Control Measures

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

- Pandemic planning

- Health surveillance information

- Early warning of public health threats

- Border measures

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- List of Recommendations

- Exhibits:

- 8.1—Key events in the initial public health response to the pandemic

- 8.2—Plans were developed to inform a response to a pandemic

- 8.3—Examples of federal, provincial, and territorial roles and responsibilities during a pandemic as set out in the response plan

- 8.4—Previous audit reports contained findings and recommendations on health surveillance data sharing and standards

- 8.5—Provinces and territories were asked to send case report forms that included specific data elements for probable or confirmed cases of COVID‑19 to the Public Health Agency of Canada

- 8.6—The Public Health Agency of Canada’s 2 key pandemic response committees met frequently to discuss public health response to COVID‑19

- 8.7—Enforcement of mandatory quarantine was limited

Introduction

Background

8.1 A pandemic occurs when an infectious disease spreads widely. Pandemics can occur at any time, cross international borders, and affect a large number of people. Because of the unpredictability of pandemics and the important health, societal, and economic consequences they may have, Canada must be prepared to respond to infectious diseases of pandemic potential at all times.

8.2 When a pandemic occurs, identifying, tracking, and forecasting the disease’s spread are important so that all levels of government can quickly respond and deploy resources as required to limit the spread of the disease. Decision makers need credible and timely risk assessments to guide effective responses. Also important is an effective national surveillance framework to collect, share, analyze, and report public health information. Responses may also include border control measures such as traveller restrictions, border closures, and quarantine and isolation orders.

8.3 On 31 December 2019, reports emerged of a cluster of cases of viral pneumonia of unknown origin in Wuhan, China. A new coronavirus was identified to cause the disease, later named coronavirus disease (COVID‑19)Definition 1 by the World Health Organization. Canada’s first case of the disease was confirmed on 27 January 2020.

8.4 Through February and into March, the disease spread internationally at a rapid rate. On 30 January 2020, the World Health Organization declared the outbreak in China to be a public health emergency of international concern and on 11 March 2020 declared COVID‑19 to be a pandemic. Five days later, Canada had 401 confirmed cases and the Chief Public Health Officer of Canada stated that COVID‑19 posed a serious health risk. Key events in the initial public health response to COVID‑19 are highlighted (Exhibit 8.1).

Exhibit 8.1—Key events in the initial public health response to the pandemic

2019

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

|

December 31 |

The Global Public Health Intelligence Network issued a daily report with a link to an article about an outbreak of viral pneumonia of unknown origin in central China. |

2020

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

|

January 2 |

The Chief Public Health Officer of Canada sent an email to all members of the national Council of Chief Medical Officers of Health informing them of a cluster of undiagnosed viral pneumonia in China. |

|

January 7 |

Chinese authorities confirmed a new coronavirus identified as the cause of the pneumonia outbreak, as reported by the World Health Organization. |

|

January 15 |

The Federal-Provincial-Territorial Public Health Response Plan for Biological Events was activated to support coordination of federal, provincial, and territorial preparedness and response to the emergence of the coronavirus. |

|

January 22 |

Enhanced screening measures were implemented at the Vancouver, Toronto, and Montréal international airports to identify travellers from the city of Wuhan, China with symptoms and to inform travellers on what to do if they became ill. |

|

January 27 |

Canada’s first domestic case of illness caused by the new coronavirus was confirmed. |

|

January 29 |

The enhanced screening measures previously implemented at the Vancouver, Toronto, and Montréal international airports were expanded to identify travellers from Hubei province, China, who may have had symptoms upon arrival and to inform travellers on what to do if they became ill after their return. |

|

January 30 |

The World Health Organization declared a public health emergency of international concern, an extraordinary event that constitutes a public health risk through the international spread of disease and that potentially requires a coordinated international response. |

|

February 3 |

An Emergency OrderNote * came into effect for a mandatory 14-day quarantine in federal facilities for repatriated Canadians from Hubei province, China. |

|

February 9 |

The enhanced screening measures previously implemented at 3 international airports were expanded to include all travellers from Hubei province, China, at 7 more airports: Calgary, Edmonton, Winnipeg, Billy Bishop Toronto City Airport, Ottawa, Québec, and Halifax. |

|

February 11 |

The World Health Organization announced COVID‑19 as the name of the disease caused by the new coronavirus. |

|

February 17 and 19 |

Emergency orders came into effect for mandatory 14-day quarantine in federal facilities for a number of repatriated Canadians from China and from the Diamond Princess cruise ship. |

|

March 3 |

The enhanced screening measures previously implemented at international airports were expanded to include all travellers from Iran. |

|

March 6 |

The enhanced screening measures previously implemented at international airports were expanded to all ports of entry. |

|

March 11 |

The World Health Organization declared the global outbreak of COVID‑19 a pandemic. |

|

March 12 |

The enhanced screening measures previously implemented at all ports of entry were expanded to include all travellers from Italy. |

|

March 13 |

A global travel advisory to avoid non-essential travel outside Canada until further notice was issued and Canadians abroad were urged to return home. |

|

March 16 |

The enhanced screening measures previously implemented at all ports of entry were expanded to cover all travellers entering Canada, along with voluntary self-isolation for 14 days (with exemptions for essential workers without symptoms). |

|

March 18 |

An Emergency Order came into effect prohibiting the entry of foreign nationals for discretionary purposes, with exception for citizens of the United States. |

|

March 21 |

The Emergency Order prohibiting the entry of foreign nationals for discretionary purposes was expanded to include citizens of the United States (with exemptions for essential workers). |

|

March 25 |

An Emergency Order came into effect for mandatory 14-day quarantine for all incoming travellers, whether or not they had symptoms of COVID‑19 (with exemptions for essential workers). |

Source: Based on information from the Public Health Agency of Canada, the Canada Border Services Agency, emergency orders issued under the Quarantine Act, and announcements from the federal government and the World Health Organization

8.5 In Canada, public health is a shared responsibility between the federal government, the 10 provinces, and the 3 territories. Ensuring a consistent approach to pandemic planning requires the federal, provincial, and territorial governments to work together.

8.6 Public Health Agency of Canada. The Public Health Agency of Canada supports the federal Minister of Health on a number of public health issues and is the lead federal organization for planning and coordinating a national response to infectious diseases that pose a risk to public health. The Chief Public Health Officer of Canada is the lead health professional of the Government of Canada responsible for public health and provides advice to the Minister of Health and the president of the agency.

8.7 The agency plays a key role in planning for public health emergencies by developing and maintaining plans that support national emergency response. It also coordinates intergovernmental collaboration on public health matters and facilitates policy development and access to health surveillance information.

8.8 Canada Border Services Agency. The Canada Border Services Agency plays an important role in supporting national security and public health and safety priorities by enforcing federal legislation and orders. In cooperation with the Public Health Agency of Canada, the Canada Border Services Agency can implement a variety of border control measures to help protect public health. Border control measures are actions that may be used in an emergency and include

- screening arriving travellers

- providing information and travel health notices

- collecting contact information from travellers entering Canada and providing it to the Public Health Agency of Canada

- enforcing an emergency order for mandatory quarantine or isolation

- enforcing an emergency order for entry restrictions at the border

Focus of the audit

8.9 This audit focused on whether the Public Health Agency of Canada was prepared to effect a pandemic response that would protect public health and safety and would be supported by accurate and timely public health surveillance information. This audit also focused on whether the Public Health Agency of Canada and the Canada Border Services Agency implemented and enforced border control and mandatory quarantine measures to limit the spread in Canada of the virus that causes COVID‑19.

8.10 This audit is important because a well-planned and informed public health response is crucial to limiting the spread and public health impact of an infectious disease during a pandemic. In particular, timely and comprehensive surveillance information is needed to direct public health efforts. Border control and quarantine measures can help to limit the spread of an infectious disease and lessen the impact of a pandemic on the health of people in Canada.

8.11 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Overall message

8.12 Since the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, the Public Health Agency of Canada has further developed plans to guide a response to a pandemic. In particular, the agency worked with its federal, provincial, and territorial partners to develop the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Public Health Response Plan for Biological Events. Moreover, since the beginning of January 2020, the Public Health Agency of Canada has worked collaboratively with its provincial and territorial partners to support Canada throughout the COVID‑19 pandemic. But the agency was not adequately prepared to respond to the pandemic, and it underestimated the potential impact of the virus at the onset of the pandemic.

8.13 The agency was not as well prepared as it could have been because it had not resolved long-standing issues in health surveillance information, including shortcomings that impeded the effective exchange of health data between the agency and the provinces and territories. Also, the agency did not regularly update or test all plans for a national health response to a pandemic, especially one of such magnitude as the COVID‑19 pandemic. For example, the agency did not complete test response elements of the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Public Health Response Plan for Biological Events with its partners prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic. We found that the agency’s Global Public Health Intelligence Network did not issue an alert to provide early warning when the virus was first reported but did email a daily report to domestic subscribers with links to related news articles. Although the agency prepared rapid risk assessments, these did not consider the pandemic risk of this emerging infectious disease or its potential impact—information necessary to guide decision makers on the public health measures needed to control the spread of the virus. Despite these gaps, we recognize that the agency quickly adapted the plans it had and continuously adjusted its response to COVID‑19 as the pandemic progressed.

8.14 Since the onset of the pandemic, the agency has made strides in collecting surveillance data from the provinces and territories to support a national public health response. However, although the Public Health Agency of Canada put in place a data sharing agreement with its provincial and territorial partners, important parts of the agreement set out in technical annexes had not yet been finalized. In addition, the agency’s outdated information technology infrastructure issues still need to be addressed to help ensure its ability to inform a consistent national picture of COVID‑19 infections in Canada to support an effective response to the COVID‑19 pandemic and future infectious disease outbreaks.

8.15 The Public Health Agency of Canada and the Canada Border Services Agency worked collaboratively to implement emergency orders to restrict entry into Canada and require incoming travellers to quarantine. However, the Public Health Agency of Canada did not know whether two thirds of incoming travellers followed quarantine orders. The agency referred few of the travellers for in-person follow-up to verify compliance with orders.

Pandemic planning

The Public Health Agency of Canada had prepared plans and national guidance to support a response to a pandemic but had not completed a planned testing exercise or updated all of the plans and guidance

8.16 We found that following infectious disease outbreaks in Canada, such as the H1N1 virus pandemic in 2009, the Public Health Agency of Canada took steps to further develop plans and national guidance to prepare for future outbreaks of infectious diseases. However, prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic, the agency did not update all of the plans.

8.17 We also found that, although the agency engaged with provincial and territorial partners and was advanced in its preparations to test the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Public Health Response Plan for Biological Events through a large-scale exercise simulating an influenza pandemic, the agency did not complete this test exercise with its partners prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic. The test exercise had been scheduled for 2020. The agency indicated that testing activities could not proceed further, as they were interrupted by the COVID‑19 pandemic.

8.18 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

- Plans and national guidance prepared

- Federal health portfolio plans and national guidance not updated

- Testing of the federal, provincial, and territorial plan not completed

8.19 This finding matters because response plans that are current, updated regularly, and thoroughly tested support that

- roles and responsibilities at the federal and provincial or territorial levels are clear and well-coordinated and understood among partners

- the agency has the capacities and resources to implement the plans

- the agency is prepared to support Canada’s pandemic preparedness and response goals of minimizing serious illness, overall deaths, and societal disruption among Canadians as a result of a pandemic

8.20 Under the Emergency Management Act and the Federal Policy for Emergency Management, federal institutions must

- prepare emergency management plans for their areas of responsibility

- maintain, test, and implement the plans

- conduct exercises and training related to the plans

8.21 Given that it is impossible to predict when a pandemic may occur or how severe the impact on Canadians will be, the Public Health Agency of Canada must be ready to respond to a pandemic at any time.

8.22 Following the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, the agency completed a lessons learned review, and the Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology completed a review of Canada’s response to the pandemic. Reports identified actions to improve Canada’s pandemic preparedness, including

- streamlining the federal-provincial-territorial governance structure and clarifying roles and responsibilities

- undertaking regular and rigorous testing of pandemic-related plans at all levels

8.23 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 8.37.

Plans and national guidance prepared

8.24 We found that since the 2009 H1N1 virus pandemic, the Public Health Agency of Canada has further developed plans to guide a response to a pandemic (Exhibit 8.2):

- At the federal-provincial-territorial level, the agency worked with its provincial and territorial partners to develop the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Public Health Response Plan for Biological Events.

- At the federal level, the agency also developed 2 plans for the federal health portfolio, which includes the agency and Health Canada.

Exhibit 8.2—Plans were developed to inform a response to a pandemic

Federal-Provincial-Territorial Public Health Response Plan for Biological Events

This plan

- was developed by the Pan-Canadian Public Health Network Council

- coordinates the federal, provincial, and territorial response to public health events, including pandemics

- details a governance structure to be activated as needed, depending on the level of federal, provincial, and territorial coordination required

This governance is centered on a Special Advisory CommitteeNote * and aims to streamline the response processes by providing clarity on roles, responsibilities, and approval processes. This governance structure also aims to facilitate situational awareness among the health sectors of the jurisdictions.

Created

2017

Last updated

No subsequent updates

Federal health portfolio plans

The agency’s emergency plans provide the generic requirements of emergency response activities. Annexes to the plans meet the unique needs of a particular threat, including a pandemic.

Health Portfolio Strategic Emergency Management Plan

This plan

- provides strategic guidance for emergency management across the health portfolio, including the health portfolio mandate, the broad objectives, the risk environment, and the response operations structure

- describes the emergency management roles and responsibilities of the health portfolio during response operations

Created

2012

Last updated

2016

Health Portfolio Emergency Response Plan

This plan

- provides guidance on how the health portfolio staff will transition from normal operations into emergency response operations for events with public health implications

- outlines a phased response process with supporting tools

- details the structure of the Health Portfolio Executive GroupNote * that will lead the coordination of the health portfolio’s emergency response efforts

Created

2009

Last updated

2013

Note: Canada has had an influenza pandemic plan since 1988. In 1998, the federal-provincial-territorial pandemic planning process began, which led to the establishment of the first federal-provincial-territorial influenza pandemic plan in 2004.

8.25 We found that, in addition to the plans, the agency worked with its provincial and territorial partners to improve national guidance following the H1N1 pandemic. The Canadian Pandemic Influenza Preparedness: Planning Guidance for the Health Sector provides the federal, provincial, and territorial health sectors with operational advice for pandemic planning, and contains a series of technical annexes on specific response elements. The latest version of this Pan-Canadian Public Health Network document was approved by federal, provincial, and territorial deputy ministers of health in 2014, with a further update made in 2018.

8.26 We found that the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Public Health Response Plan for Biological Events and national guidance documented roles and responsibilities for responding to a pandemic (Exhibit 8.3).

Exhibit 8.3—Examples in the response plan of federal, provincial, and territorial roles and responsibilities during a pandemic

Roles and responsibilities

Federal government

- coordinating the overall federal-provincial-territorial response

- managing all international aspects of a pandemic response, including travel health notices, and exercising powers under the Quarantine Act

- preparing and communicating risk assessments

- mobilizing medical supplies in the National Emergency Strategic StockpileNote * to support provincial and territorial responses and acquiring extra medical supplies

Provinces and territories

- providing health care services

- collecting health information and reporting data to the federal level

- communicating the response and messages at a provincial or territorial level

- ensuring the provision of medications, supplies, and equipment required for provision of health care services

Shared

- implementing surveillance standards and protocols

- establishing and implementing protocols for timely sharing of surveillance information

- developing and implementing public health guidance

Note: The National Emergency Strategic Stockpile will be the subject of a future audit.

Source: Federal-Provincial-Territorial Public Health Response Plan for biological Events, Pan-Canadian Public Health Network, 2018; definition of the national stockpile based on information from National Emergency Strategic Stockpile, Public Health Agency of Canada, 2019

8.27 We found that the roles and responsibilities among the levels of government established in the federal-provincial-territorial plan supported engagement between the federal, provincial, and territorial governments during the COVID‑19 pandemic response. For example, on 15 January 2020, the agency put the plan into action, and the Special Advisory Committee was established on 28 January 2020. Documents provided by the agency indicated that the committee regularly held meetings and approved and coordinated guidance for the pandemic response, including the approved COVID‑19 surveillance guidelines.

8.28 We found that alongside these general plans, in spring 2020 the agency began working with its partners to develop the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Public Health Response Plan for Ongoing Management of COVID‑19. This plan, finalized in August 2020, was built on experience in responding to the first wave of the pandemic. The plan provides an approach for managing COVID‑19 in Canada until enough immunity is achieved within the population to bring the pandemic in Canada to an end.

Federal health portfolio plans and national guidance not updated

8.29 The Public Health Agency of Canada is the federal lead for maintaining, reviewing, and revising public health response plans to ensure that they are current, appropriate, and based on the ever-evolving public health landscape. Response planning must take into account the wide range of threats that fall under the agency’s areas of responsibility.

8.30 We found that the agency did not update the 2 plans for the federal health portfolio entities prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic. The Health Portfolio Strategic Emergency Management Plan is supposed to be reviewed every 2 years at a minimum to assess the need to update it. But the plan had not been reviewed or updated since 2016. As of late 2019, the agency had identified the need to update it to reflect

- the creation of the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Public Health Response Plan for Biological Events

- the federal health portfolio’s new risk and capability assessment process

- lessons learned from the opioid crisis

- changes to roles and responsibilities within the federal health portfolio

8.31 In addition, the Health Portfolio Emergency Response Plan is meant to be reviewed and updated regularly to ensure that it reflects changes in legislation, policy priorities, and lessons learned. We found that this plan had not been updated since 2013, despite an agency evaluation on pandemic preparedness and response done in 2018 that identified the need to review and update the plan by March 2020.

8.32 Regarding national guidance, the Canadian Pandemic Influenza Preparedness: Planning Guidance for the Health Sector states that the main body and technical annexes will be reviewed every 5 years, with updates made between reviews if necessary. We found that, although the main body was updated in 2014, with further updates in 2018, the agency identified in 2019 that it was due for review. The agency indicated that the review was delayed until the large-scale influenza pandemic exercise scheduled for 2020 had been completed so that the agency could incorporate lessons learned into the document (see paragraph 8.35). Furthermore, we found that 3 of the 9 annexes were not updated prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic, specifically

- the health care services annex

- the psychosocial annex

- the annex covering considerations for on-reserve First Nations communities

8.33 The agency coordinated the updates of the annexes with its partners in order of priority. According to the agency, it takes one and a half years to complete the work for each annex. Two of these annexes were in the process of being updated when the pandemic arrived in Canada. We found that the COVID‑19 Pandemic Guidance for the Health Care Sector was published in April 2020 and included previously unpublished material developed for the health care services annex that was adapted for the pandemic.

Testing of the federal, provincial, and territorial plan not completed

8.34 The Public Health Agency of Canada is the lead for testing pandemic-related response plans under its responsibility. Following the H1N1 pandemic, the need for regular and rigorous testing of plans at all levels was one of the lessons learned and one of the recommendations from the Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology. Through testing exercises, it is possible to

- evaluate plans, policies, and procedures

- reveal planning weaknesses

- reveal gaps in resources

- improve organizational coordination and communications

- clarify roles and responsibilities

- improve employee performance

8.35 We found that, although the agency engaged with provincial and territorial partners and was advanced in its preparations to test the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Public Health Response Plan for Biological Events through a large-scale exercise simulating an influenza pandemic, the agency did not complete this test exercise with its partners prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic. The test exercise had been scheduled for 2020. The exercise, developed with provincial and territorial partners, would have tested a variety of response elements, including the infrastructure for gathering and sharing public health data. The agency indicated that because of the COVID‑19 pandemic, this exercise could not proceed further.

8.36 In our view, if the agency had completed a national pandemic simulation exercise before the COVID‑19 pandemic, it could have improved its understanding of provincial and territorial pandemic response capacity, ensured roles and responsibilities were understood among partners, and identified potential obstacles to a response.

8.37 Recommendation. The Public Health Agency of Canada should work with its partners to evaluate all plans to assess whether emergency response activities during the COVID‑19 pandemic were carried out as intended and met objectives. This evaluation and other lessons learned from the pandemic should inform updates to plans. The agency should further test its readiness for a future pandemic or other public health event.

The agency’s response. Agreed. The experience of COVID‑19 has provided a lived experience of a global pandemic, the nature of which Canada has not seen in over 100 years. Recognizing that existing plans provided a framework to guide the current response but that improvements are always possible, the Public Health Agency of Canada will incorporate learnings from the pandemic into its plans and test them as appropriate. In updating and testing these plans, the agency will work with provincial and territorial partners to reflect shared responsibilities for public health emergencies. This work will be completed within 2 years after the end of the pandemic.

Health surveillance information

Although the Public Health Agency of Canada took some steps to implement solutions, long-standing shortcomings in health surveillance information impeded the effective exchange of health data between the agency and provinces and territories

8.38 We found that although the Public Health Agency of Canada put in place a data sharing agreement with its provincial and territorial partners, important parts of the agreement set out in technical annexes had not yet been finalized. In early 2020, the agency and its provincial and territorial partners developed surveillance guidelines and a case reporting form specific to COVID‑19 surveillance. However, the agency did not fully report to internal decision makers on COVID‑19 data surveillance elements and it indicated that some gaps in reporting were due to missing information in the case forms received. We also found that there were several long-standing shortcomings concerning the agency’s information technology infrastructure used for the storage, processing, and analysis of health surveillance data from provinces and territories. The agency began to implement improvements to this infrastructure in October 2020. The agency informed us that while these shortcomings did not prevent provinces and territories from providing their data to the agency, the shortcomings had an impact on the timeliness with which the data could be cleaned, processed, and analyzed.

8.39 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

- Past recommendations on data sharing agreements and the legislative review of authorities not fully implemented

- Incomplete surveillance data reports about COVID‑19

- Inadequate information technology infrastructure

8.40 This finding matters because identifying, tracking, and forecasting the spread of viruses helps governments and public health officials quickly respond and deploy resources as required to mitigate the spread of an infectious disease during a pandemic. An effective pandemic response depends on a strong information technology infrastructure to support collecting, standardizing, and managing data from multiple sources so it can be analyzed and ultimately inform public health decision makers.

8.41 Also, because key health data is shared by the provinces and territories with the agency to support surveillance, it is important that agreements be in place to help ensure the timely interjurisdictional sharing of complete and accurate health data. Such agreements should make clear the expectation of full reporting against an agreed-upon set of health data elements.

8.42 The Federal-Provincial-Territorial Public Health Response Plan for Biological Events defines surveillance as the routine, systematic, and ongoing collection, collation, and analysis of public health information for public health purposes. Surveillance is done as a routine activity (for example, the ongoing monitoring of measles in Canada) and in response to a public health emergency (such as during the COVID‑19 pandemic). One of the agency’s objectives is to establish and implement an effective national framework for public health surveillance so that it can collect, analyze, and share relevant and timely information across jurisdictions. Surveillance results should show when and where a virus is circulating, its intensity, and whether specific population groups are at higher risk for illness.

8.43 Along with data quality, appropriate information technology infrastructure to support the collection, standardization, and management of data is crucial to the success of surveillance during a pandemic. Previous reviews highlighted the importance of information technology infrastructure in supporting an effective pandemic response—for example:

- A national advisory committee on severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and public health officials found that during the 2003 SARS epidemic, an inappropriate information technology infrastructure had a negative impact on information flow and on the management of the outbreak.

- The Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology also mentioned the importance of information technology infrastructure in its review after the 2009 H1N1 pandemic.

8.44 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 8.51, 8.65, and 8.66. The recommendation in paragraph 8.66 is our overall recommendation on health surveillance information.

Past recommendations on data sharing agreements and the legislative review of authorities not fully implemented

8.45 We found that the Public Health Agency of Canada had not made satisfactory progress on selected recommendations made in our previous audit reports on health surveillance information related to data sharing agreements and the legislative review of authorities for surveillance activities.

8.46 Gaps in data sharing agreement. We found that, prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic, the Public Health Agency of Canada, along with its partners, did not finalize agreed-upon surveillance standardsDefinition 2 for the data it should have received from provinces and territories, as we had recommended in our 2008 audit report on the surveillance of infectious diseases. In 1999 and 2002, we also examined the management of federal surveillance programs for infectious diseases, which was then the responsibility of Health Canada (Exhibit 8.4).

Exhibit 8.4—Previous audit reports contained findings and recommendations on health surveillance data sharing and standards

| Year | Report title | Findings and recommendations |

|---|---|---|

|

1999 |

Report of the Auditor General of Canada, Chapter 14—National Health Surveillance: Diseases and Injuries |

A lack of common standards and agreed-upon procedures for reporting information at the provincial and territorial level affected Health Canada’s capacity to collect data on communicable diseases. We recommended Health Canada work with provinces and territories to establish common standards and protocols for classifying, collecting, and reporting data on communicable diseases. |

|

2002 |

Status Report of the Auditor General of Canada, Chapter 2—National Health Surveillance—Health Canada |

For the most part, Health Canada still had no agreements in place with provincial and territorial governments on data sharing and common standards. We recommended Health Canada obtain agreement on the sharing of disease information, including data collection, data dissemination, and data standards. |

|

2008 |

Report of the Auditor General of Canada to the House of Commons, Chapter 5—Surveillance of Infectious Diseases—Public Health Agency of Canada |

The Public Health Agency of Canada was not assured of receiving timely, accurate, and complete information because of gaps in its information sharing agreements with its partners. We recommended that the agency establish data sharing agreements to ensure that it was receiving timely, complete, and accurate surveillance information from all provinces and territories. We also recommended that the agency work with its provincial and territorial partners to implement agreed-upon standards for the data it was receiving from them. |

Notes:

1. Prior to the establishment of the Public Health Agency of Canada in 2004, Health Canada was the federal department responsible for public health surveillance.

2. The surveillance standards defined in our 2008 audit report on the surveillance of infectious diseases included

- the infectious diseases that should be reported

- the definitions to be used

- the information to be provided for each case

- timelines for reporting the information

- the method for submitting the information

- the parties required to submit reports

8.47 In recent years, the agency put in place an agreement with its provincial and territorial partners that formalizes certain basic rules for the collection, use, and disclosure of public health information on infectious diseases. This agreement—the Multi-Lateral Information Sharing Agreement—was in force across the country by 2016. However, we found that important parts of the agreement set out in technical annexes had not yet been finalized. These annexes included standards on key information about an infectious disease that would be provided as part of the surveillance of that disease. For example, the common data elements annex was not approved by the parties, and therefore not in force, although it includes fundamental data elements such as

- whether a person was hospitalized as a result of the disease

- the person’s symptoms of the disease and the date of their onset

- whether the person identified as Indigenous/Aboriginal

We also found that the agreement did not include timelines for delivering different types of surveillance data to the agency.

8.48 During a 2018 review of the information sharing agreement conducted by a federal-provincial-territorial table of representatives, parties identified a lack of clarity around what and how information is to be shared under routine and emergency situations. This review indicated that many of the challenges were expected to be addressed once the technical annexes had been completed and the agreement fully implemented.

8.49 Legislative review of authorities for surveillance activities. In 2008, we reported that the Public Health Agency of Canada did not have clear and up-to-date legislative authorities for its surveillance activities, either for routine data collection or to respond to emergency situations. In that report, we recommended that the agency, with Health Canada, complete a review of its legislative authorities found in the Public Health Agency of Canada Act for the collection, use, and disclosure of public health information to clarify roles and responsibilities and ensure the receipt of relevant and timely surveillance information. We also recommended that, if necessary, the agency should seek additional authorities for it to carry out these surveillance activities.

8.50 We expected the agency to have completed this legislative review by the time of this audit. We found that the agency took steps in 2009 toward making regulations for the collection, use, and disclosure of public health information, but it did not finalize them. Moreover, the agency did not provide any evidence that it had analyzed whether it needed additional legislative authorities to conduct surveillance activities.

8.51 Recommendation. The Public Health Agency of Canada should, in collaboration with its provincial and territorial partners, finalize the annexes to the multi-lateral agreement to help ensure that it receives timely, complete, and accurate surveillance information from its partners. In addition, in collaboration with provinces and territories, the agency should set timelines for completing this agreement. This exercise should be informed by lessons learned from data sharing between the agency and its partners during the COVID‑19 pandemic.

The agency’s response. Agreed. The Public Health Agency of Canada will continue to work with its provincial and territorial partners to develop a new work plan for the multi-lateral agreement. The new work plan will be developed with provincial and territorial partners on the basis of lessons learned from the COVID‑19 pandemic and the forthcoming recommendations from the pan-Canadian health data strategy.

The agency will use lessons learned to evolve the existing federal-provincial-territorial governance, through which a joint critical path for delivery on the multi-lateral agreement will be outlined. The necessary agreements to support receiving timely and accurate surveillance information from its provincial and territorial partners will also be articulated. Both the work plan and governance recommendations will be addressed within 2 years of the end of the pandemic.

Incomplete surveillance data reports about COVID‑19

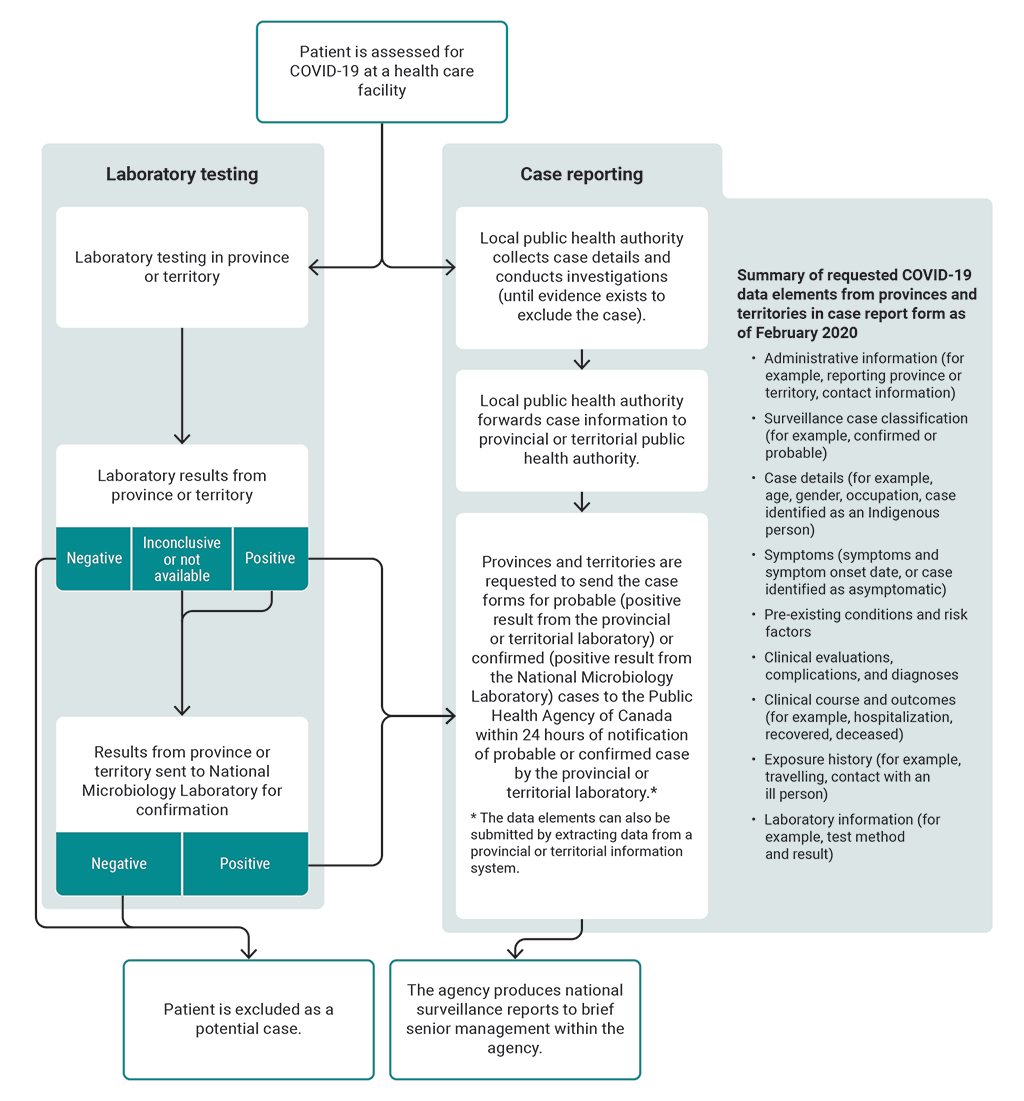

8.52 In early February 2020, the agency and its provincial and territorial partners approved COVID‑19 surveillance guidelines, a reporting process, and a COVID‑19–specific case report form. Provinces and territories were asked to send a case report form to the agency within 24 hours of notification of each probable or confirmed COVID‑19 case. The case forms received from the 10 provinces and 3 territories are important sources for the agency’s COVID‑19 data surveillance. The case report form included several requested data elements for the agency to be able to track the disease (Exhibit 8.5).

Exhibit 8.5—Provinces and territories were asked to send case report forms that included specific data elements for probable or confirmed cases of COVID‑19 to the Public Health Agency of Canada

Source: Based on information from the Public Health Agency of Canada

Exhibit 8.5—text version

This flow chart presents the case reporting process from assessing a patient for COVID-19 in the provinces and territories to producing national surveillance reports.

Here are details of the process:

A patient is assessed for COVID-19 at a health care facility. As a result of the assessment, a laboratory test is performed. The laboratory testing is done in the province or territory. If the laboratory result is negative, the patient is excluded as a potential case. If the laboratory result is inconclusive or not available, the result is sent from the province or territory to the National Microbiology Laboratory for confirmation. If the result is positive, the provinces and territories are requested to send a case report form to the Public Health Agency of Canada within 24 hours of notification and the result is sent to the National Microbiology Laboratory for confirmation.

If a result from the National Microbiology Laboratory is negative, the patient is excluded as a potential case. If a result from the National Microbiology Laboratory is positive, the provinces and territories are requested to send a case report form for the confirmed case to the Public Health Agency of Canada within 24 hours of notification.

The case reporting process happens while the laboratory testing process is underway. After a patient is first assessed for COVID-19 at a health care facility, the local public health authority collects case details and conducts investigations, until evidence exists to exclude the case. The local public health authority forwards case information to the provincial or territorial public health authority.

Provinces and territories are requested to send the case forms for probable cases, meaning positive results from the provincial or territorial laboratory, and confirmed cases, meaning positive results from the National Microbiology Laboratory, to the Public Health Agency of Canada within 24 hours of notification of probable or confirmed cases by the provincial or territorial laboratory.

The data elements in the case report form can also be submitted by extracting data from a provincial or territorial information system.

The final step in the process presented in the flow chart is that the agency produces national surveillance reports to brief senior management within the agency.

The flow chart provides a summary list of requested COVID-19 data elements from provinces and territories in the case report form as of February 2020. The list includes

- administrative information (for example, reporting province or territory, contact information)

- surveillance case classification (for example, confirmed or probable)

- case details (for example, age, gender, occupation, case identified as an Indigenous person)

- symptoms (symptoms and symptom onset date, or case identified as asymptomatic)

- pre-existing conditions and risk factors

- clinical evaluations, complications, and diagnoses

- clinical course and outcomes (for example, hospitalization, recovered, deceased)

- exposure history (for example, travelling, contact with an ill person)

- laboratory information (for example, test method and result)

Source: Based on information from the Public Health Agency of Canada

8.53 As of July 2020, the agency indicated that it obtained 99% of the expected case forms from provinces and territories. However, much of the data in the forms was incomplete—for example:

- hospitalization data was provided in only 67% of the case forms

- symptoms, onset date, and risk factors (for example, pre-existing health conditions) were provided in only 10% of the case forms

8.54 We found that the Public Health Agency of Canada did not fully report to internal decision makers on COVID‑19 data surveillance elements as stated in its interim national surveillance guidelines for COVID‑19. The agency indicated that some gaps in reporting were because of missing information in the case forms received from provinces and territories. The February 2020 guidelines state that the agency will routinely report the results of descriptive analyses of cases, such as distribution by age, gender, geography, exposure history, and disease severity indicators. Accordingly, from March to June 2020, the agency produced a series of daily, weekly, and monthly national surveillance reports to brief senior management within the agency. These reports provided statistics on COVID‑19 cases, such as death and hospitalization figures. However, we found that the agency did not include information for a number of data elements in these reports, including the reason for testing, whether a person identified as Indigenous, most of the symptoms, and clinical evaluation information.

8.55 Therefore, we found that the agency had to do regular quality assurance controls to assess the reliability of data elements with low completion rates or quality issues. As a result, the agency indicated that some key data elements had to be excluded from routine reports to its senior management to ensure the accuracy of the briefing information.

8.56 We also found that COVID‑19 surveillance data from the provinces and territories was not provided within agreed-upon timelines. Only 4% of the COVID‑19 cases in Canada from February to June 2020 were provided to the agency within 24 hours of detection as requested.

8.57 The agency indicated that the incomplete data reporting from provinces and territories was because of the information management challenges faced by some provinces and territories, as well as data not being available at a given moment in time. These factors made the 24-hour submission deadline difficult to achieve.

8.58 We found that the agency developed a plan in June 2020 that included actions to review and revise the data elements it needed from provincial and territorial partners to help improve the timeliness and comprehensiveness of the reporting. Revised and updated sets of data elements were approved in June and September 2020 by all parties. However, the agency indicated that many of the surveillance data elements it asked for from provinces and territories remained incomplete as of November 2020.

8.59 In our view, the lack of complete and timely surveillance data made it difficult for the agency to meet its 2 main public health surveillance goals during the COVID‑19 pandemic:

- detecting and containing the virus early

- characterizing the clinical features (such as symptoms) and epidemiologic features (such as close contacts or travel history) of COVID‑19 cases to better inform prevention and control efforts

Inadequate information technology infrastructure

8.60 We found that the Public Health Agency of Canada had identified several problems with the information management system used for its COVID‑19 surveillance program during our audit period—for example:

- Manual data processing. Although received electronically from provincial and territorial partners in the majority of cases, health data files were manually copied and pasted from the data intake system into the agency’s processing environment. These manual processes could cause delays or errors.

- Data formatting. The agency received the data in inconsistent formats from provinces and territories, requiring complex processes to transform it.

- Storage capacity. The agency’s database system had insufficient storage capacity to deal with anticipated future needs and would likely soon be incapable of hosting all of the requested records related to COVID‑19 health information.

8.61 According to the agency, its information technology infrastructure limitations had a negative impact on the timeliness with which data was processed and therefore analyzed to inform a consistent national picture of COVID‑19 infections in Canada.

8.62 We found that for more than 10 years prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic, the agency had identified gaps in its existing infrastructure but had not implemented solutions to improve it. In its last 2 strategic plans for surveillance, the agency identified several capacity deficiencies in the information technology infrastructure used to support its public health surveillance activities:

- In its 2016–2019 strategic plan for surveillance, the agency identified an ongoing need for improved technical infrastructure to support surveillance and data management.

- In the previous plan (2013–2016), the agency similarly identified building a corporate model for data management and technology to support surveillance as a strategic objective. Despite some work being done, this initiative was never completed.

8.63 In September 2019, the agency published an organization-wide data strategy. One of the strategy’s key themes was the improvement of the agency’s data infrastructure. The strategy set out a phased approach for implementing objectives for each theme according to specified timelines.

8.64 Building upon work that had begun in 2019, the agency developed a new cloud-based platform to collect and manage COVID‑19 health data. The first phase of this portal became operational after our audit period, in October 2020. The agency anticipates that this system will improve data flow with the provinces and territories, will address the challenges associated with the existing system, and will enable comparative analysis against national-level data. The agency indicated that additional phases of the system would be implemented in 2021 to introduce more features to the portal and make data available for research purposes.

8.65 Recommendation. The Public Health Agency of Canada should finalize the improvements to its information technology infrastructure to facilitate the collection of timely, accurate, and complete surveillance information from provinces and territories, both during and after the COVID‑19 pandemic. The agency should establish timelines for the completion of these improvements.

The agency’s response. Agreed. The Public Health Agency of Canada will work with provincial and territorial partners through established governance mechanisms, including the Technical Advisory Committee, the Special Advisory Committee, and the Canadian Health Information Forum, to build on the information management and information technology improvements already underway and articulate the additional functionality at the federal level to facilitate the collection of surveillance information from provinces and territories. The agency will use this intelligence to finalize improvements to its information technology infrastructure, in order to facilitate the sharing of timely, accurate, and complete surveillance information provided by provinces and territories both during and after the COVID‑19 pandemic. This work will also address any relevant forthcoming recommendations from the pan-Canadian health data strategy. A critical path with clear milestones will be developed with provincial and territorial partners to guide this work. This recommendation will be addressed within 2 years of the end of the pandemic.

8.66 Recommendation. The Public Health Agency of Canada should develop and implement a long-term, pan-Canadian health data strategy with the provinces and territories that will address both the long-standing and more recently identified shortcomings affecting its health surveillance activities. This strategy should support the agency’s responsibility to collect, analyze, and share relevant and timely information.

The agency’s response. Agreed. The Public Health Agency of Canada signalled its commitment to continue improving health data collection, sharing, and use by creating the Corporate Data and Surveillance Branch in October 2020. Under the leadership of the new branch, the agency launched collaborative work with its federal, provincial, and territorial partners, as well as diverse data stakeholders, toward articulating a pan-Canadian health data strategy. The strategy will identify and address COVID‑19 data issues and provide recommendations for addressing the long-standing issues that have a negative impact on Canada’s ability to collect, share, and use health data. Success is dependent on collaboration with and commitment from provincial and territorial partners.

Significant progress has been made to support federal, provincial, and territorial partnership and on the overall deliverable itself. The federal-provincial-territorial governance for the strategy was established and approved by the Conference of Deputy Ministers of Health. An expert advisory group was launched to provide strategic policy advice related to the strategy. Short- and medium-term priorities to improve Canada’s COVID‑19 data use have been identified, with summer 2021 targeted for completion. A long-term strategy is under development and is on track for completion by December 2021.

Early warning of public health threats

Global Public Health Intelligence Network alerts and agency risk assessments are key to early warning

8.67 We found that the Public Health Agency of Canada’s Global Public Health Intelligence Network (GPHIN) did not issue an alert to provide early warning about the virus that would become known as causing COVID‑19. Instead, the network shared daily reports with Canadian subscribers including federal, provincial, and territorial public health officials, which contained links to news articles reporting on the virus. The agency prepared 5 rapid risk assessments of the virus outbreak but did not prepare a forward-looking assessment of the pandemic risk, as was called for in its emergency response plan and guidance.

8.68 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

8.69 This finding matters because early warning alerts and risk assessments support decision making by public health officials on measures needed to help control and limit the spread of an infectious disease.

8.70 In 1997, the Global Public Health Intelligence Network (GPHIN) was created to monitor media reports worldwide and to provide early warning of emerging public health events by issuing alerts. The GPHIN consists of a team of analysts and an automated web-based tool. Together, they collect and filter media reports from around the globe in order to rapidly detect, identify, and assess threats to human health, such as disease outbreaks and infectious diseases. GPHIN alerts are intended to provide early warning of serious public health threats. The alerts are distributed to both domestic subscribers (450) and international subscribers (520). An alert consists of an email with a copy of the article, as well as a note about the confidence in the source (for example, unconfirmed information reported by a local media source).

8.71 The GPHIN also produces daily reports that provide links to multiple international and domestic public health articles. The daily reports are distributed internally within the agency and to provincial and territorial public health officials.

8.72 The World Health Assembly of the World Health Organization and its Member States adopted the International Health Regulations in 2005. The regulations came into force in 2007. Member States like Canada are required to develop and maintain core capacities to detect and notify the World Health Organization of specific public health risks. The goal is to protect global public health from the spread of disease and other health risks that have the potential to cross international borders.

8.73 Credible and timely risk assessments are an essential part of emergency management of public health crises. Risk assessments combine evidence-based information with expert judgment to identify the potential impact of a threat. According to the agency’s pandemic response plans and guidance, the agency must prepare a risk assessment that considers the pandemic risk of an emerging infectious disease as well as the disease’s potential impact on public health were it to be introduced into Canada.

8.74 Risk assessments are intended to be shared with senior public health officials to inform their decisions and recommendations (including with the agency’s pandemic response committees, one of which includes provincial and territorial representatives) on responses necessary to limit the impact of a pandemic in Canada.

8.75 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 8.80 and 8.85.

Global Public Health Intelligence Network alert

8.76 We found that no alert from the Global Public Health Intelligence Network (GPHIN) was issued to provide early warning of the virus. According to the agency’s criteria, an alert is to be issued for an unusual event that has the potential for serious impact or spread. However, no alert was issued when news of an unknown pneumonia was first reported, when the virus had spread outside of China, or when domestic cases were first suspected and confirmed. Public Health Agency of Canada officials confirmed that by the end of December 2019, other international sources had already shared news of the virus and therefore it was unnecessary to issue an alert. For comparison, we note that GPHIN issued 1 alert in May 2019, warning about an Ebola-like illness in Uganda, and 1 in alert in August 2020, warning about a virus infection caused by tick bites in China.

8.77 We found that GPHIN daily reports were issued about the new virus. The first report was issued on 31 December 2019 with a link to an article describing an outbreak of viral pneumonia of unknown origin in China. Unlike a GPHIN alert, these reports were distributed only within Canada (to federal, provincial, and territorial partners). The daily reports contain links to international and national news articles and consist of publicly available information to facilitate early warning and ongoing situational awareness of emerging public health risks or threats. By contrast, a GPHIN alert warns subscribers of a potential health threat, provides a link to an article on the event of concern, and is issued on the basis of pre-established criteria to determine significance.

8.78 Agency officials confirmed that GPHIN analysts did not propose an alert for the virus. We found that the agency changed the analysts’ authorization to issue GPHIN alerts in 2018, requiring senior management approval. After this change, the number of alerts decreased significantly. From 2015 to 2018, the agency issued between 21 and 61 alerts per year (on average 1 to 2 alerts per month), whereas it issued only 1 alert for 2019 and 1 in 2020. Agency officials confirmed this change was to ensure appropriate awareness of and response to emerging issues, but GPHIN subscribers were not informed of this operational change in alert reporting. We note that the agency notified the World Health Organization of the first domestic case and subsequent cases of COVID‑19 in accordance with its reporting requirements under the International Health Regulations.

8.79 At the end of our audit, the agency formalized its existing procedures for issuing alerts. We also note that in September 2020, the Minister of Health announced an independent review of the effectiveness of the GPHIN and its contribution to public health intelligence domestically and internationally. The review had not yet been completed by the end of our audit period.

8.80 Recommendation. The Public Health Agency of Canada should appropriately utilize its Global Public Health Intelligence Network monitoring capabilities to detect and provide early warning of potential public health threats and, in particular, clarify decision making for issuing alerts.

The agency’s response. Agreed. The Global Public Health Intelligence Network (GPHIN) performed its key function of providing early warning within Canada. Early warning of an emerging public health threat on 31 December 2019 was communicated within Canada through a daily report issued by the system on that day. The Public Health Agency of Canada took immediate action on becoming aware of this emerging public health threat following this report, including enhanced surveillance and reporting.

The agency will continue to use the GPHIN as Canada’s global event-based surveillance system, relying on the full scope of its capabilities to provide early detection and warning of potential public health threats. In recognition of the need for clear decision-making processes, a standard operating procedure was put in place in fall 2020 regarding the issuance of GPHIN alerts. The agency will work to make further improvements to GPHIN and to one of the program components, the alert process, taking into account both this recommendation as well as the final recommendations of the independent review of GPHIN, expected to be issued in spring 2021.

Pandemic risk assessment

8.81 We found that the Public Health Agency of Canada completed a series of rapid risk assessments for the initial outbreak but did not assess the pandemic risk of this emerging infectious disease or its potential impact were it to be introduced into Canada. Once the emergency response plan was activated for the coronavirus on January 15, related guidance called for the completion of pandemic risk assessments. These risk assessments are intended to be forward-looking; that is, to examine the risk that an emerging infectious disease could become a pandemic, and if so, to determine the potential impact on public health. As stated in the agency’s guidance, pandemic risk assessments are intended to guide response planning and actions proportional to the assessed level of threat as well as to the reality of the evolving situation.

8.82 Instead, the agency prepared a series of 24-hour rapid risk assessments, using a methodology that was in a pilot phase of implementation and had not yet been formally evaluated or approved. Furthermore, the assessments were designed to assess the risk of a disease outbreak at a specific point in time and were meant to trigger more thorough risk assessments. We found that the methodology was not designed to assess the likelihood of the pandemic risk posed by a disease like COVID‑19 and the potential impact were it to be introduced to Canada.

8.83 Five rapid risk assessments were prepared from January to mid-March 2020 to inform the public health response. All except the last risk assessment, which was prepared on March 16, provided an overall ranking that assessed the impact of the virus as low. Because these assessments did not consider forward-looking pandemic risk, the agency assessed that COVID‑19 would have a minimal impact if an outbreak were to occur in Canada.

8.84 We reviewed the meeting minutes of the agency’s 2 key pandemic response committees (Exhibit 8.6) and found little discussion concerning the ongoing low risk rating for COVID‑19. However, on 12 March 2020, in light of escalating case counts, senior provincial and territorial public health officials raised the need for aggressive public health measures, including mandatory quarantine for international travellers. Canada had 138 confirmed cases at that time. On March 15, the Chief Public Health Officer of Canada requested that the risk rating for COVID‑19 be upgraded from low in the agency’s daily situation reports as well as on its website. The next day, the agency’s final risk assessment raised the overall COVID‑19 risk rating to high for the general public, largely because of concerns over the growing number of cases in the community. By then, Canada had 401 confirmed cases.

Exhibit 8.6—The Public Health Agency of Canada’s 2 key pandemic response committees met frequently to discuss public health response to COVID‑19

The Public Health Agency of Canada’s key pandemic response committees

The Health Portfolio Executive Group

- provides strategic direction, oversight, and advice to the Minister of Health, the Privy Council Office, the Office of the Prime Minister, and other federal agencies and departments on the COVID‑19 response effort

- consists of the agency president, the Chief Public Health Officer of Canada, and executives representing all agency branches

- is accountable to the Minister of Health

- was activated on 15 January 2020 and met daily to discuss Canada’s ongoing response to COVID‑19

The Special Advisory Committee

- forms the main approval and decision-making body for the coordination of, public health policy on, and technical content on matters related to a federal-provincial-territorial response to a significant public health event

- consists of the Chief Public Health Officer of Canada, the chief public health officers of all provinces and territories, and senior government officials from all jurisdictions responsible for public health

- reports and provides recommendations to the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Conference of Deputy Ministers of Health

- began preliminary deliberations on 14 January 2020 and was formally activated on 28 January 2020

- met twice weekly to discuss Canada’s ongoing response to COVID‑19

8.85 Recommendation. The Public Health Agency of Canada should strengthen its process to promote credible and timely risk assessments to guide public health responses to limit the spread of infectious diseases that can cause a pandemic, as set out in its pandemic response plans and guidance.

The agency’s response. Agreed. The Public Health Agency of Canada conducts risk assessments as a means to assess the severity of emerging public health threats and recognizes the importance of having a robust risk assessment process in response to public health events, including pandemics such as COVID‑19.

The agency will conduct a review of its risk assessment process and incorporate lessons learned from the COVID‑19 pandemic to support timely decision making by senior officials. In addition, the agency will engage domestic and international partners and other stakeholders to inform the review process. This review will also be consistent with and informed by other international risk assessment process reviews in response to the COVID‑19 pandemic.

This review will be completed by December 2022, recognizing that timelines for this review are dependent on the federal government and its partners’ available capacity to dedicate to this work, given the ongoing COVID‑19 pandemic.

Border measures

Border restrictions were quickly enforced

8.86 We found that the Canada Border Services Agency acted quickly to enforce emergency orders prohibiting the entry of foreign nationals to Canada, with exemptions for essential workers. The Public Health Agency of Canada and the Canada Border Services Agency worked together to develop guidance for border services officers. However, we found that the Canada Border Services Agency did not review whether border services officers were consistently applying exemptions for essential workers.

8.87 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

8.88 This finding matters because restricting the number of people entering the country during the pandemic and implementing other public health measures can limit the number of people who have, or have been exposed to, the virus, and therefore help to contain the spread of COVID‑19.

8.89 The Canada Border Services Agency had a high-level pandemic plan, which it further developed as the pandemic evolved, along with planning tools and documents to guide its border services officers. The agency created and mobilized a border task force to lead its response to COVID‑19 as the pandemic evolved. The task force was responsible for implementing border measures as directed by the Public Health Agency of Canada, as well as coordinating with other government departments to ensure that exemptions were correctly applied.

8.90 Starting in January, under the direction of the Public Health Agency of Canada, the Canada Border Services Agency implemented a number of public health measures at the border. These measures consisted of

- enhanced screening of travellers arriving from locations with high rates of virus infection and transmission (initially Wuhan, China; later, all of China, Italy, and Iran; and as of March 16, all travellers)

- providing information to incoming travellers instructing them to self-monitor for symptoms of COVID‑19 and to contact local health authorities, if necessary

- asking incoming travellers to voluntarily quarantine for 14 days

8.91 Both the Canadian Pandemic Influenza Preparedness: Planning Guidance for the Health Sector and the Government of Canada Response Plan: COVID‑19 noted that border restrictions may not be useful measures to fight a pandemic. On 30 January 2020, the World Health Organization recommended against any trade or travel restriction on the basis of the current information available. However, on 11 February 2020, while calling on countries to be prepared for the containment phase of the COVID‑19 outbreak, the World Health Organization issued a statement about the public health rationale for the use of border-related travel restrictions to contain the spread of the virus.

8.92 On 18 March 2020, an emergency order was issued under the Quarantine Act restricting the entry of foreign nationals arriving from outside the United States, with some exceptions. As of 21 March 2020, Canada and the United States agreed to temporarily restrict all discretionary travel across the Canada–United States border for 30 days, again with some exemptions, and a further emergency order was issued to that effect. These restrictions continued for the audit period, and were extended and modified in response to the evolving pandemic.

8.93 In recognition of the critical nature of ensuring that essential goods and services, food, medicines, and workers continued to be able to move across the border, the emergency orders included important exemptions from the restrictions on entry to the country. Travel of a non-discretionary nature continued to be permitted for certain individuals, including people who live in one country and work in another, first responders and health care providers, truck drivers, and workers supporting the agricultural and transportation sectors.

8.94 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 8.100.

Border measures during initial response

8.95 Beginning in January 2020, the Public Health Agency of Canada directed the Canada Border Services Agency to implement public health measures at the border on the basis of the evolving nature of the outbreak. These measures emphasized education and health promotion and voluntary compliance with quarantine recommendations for travellers who entered Canada from high-risk locations. The Quarantine Act requires that, before prohibiting or setting conditions for entry into Canada, all reasonable alternatives must be considered to prevent the introduction or spread of disease. The International Health Regulations prohibit restrictive measures as long as other reasonable alternatives exist to provide appropriate protection.

A border services officer interviews travellers entering Canada

Photo: Canada Border Services Agency

8.96 We found that, once the emergency orders restricting entry into Canada were imposed, the Canada Border Services Agency mobilized quickly to provide guidance to its border services officers on restricting entry to Canadian citizens, permanent residents, and essential workers. This was the case at all ports of entry—air, land, and marine. The Canada Border Services Agency worked closely with the Public Health Agency of Canada in planning the implementation of the public health measures at the border. Enforcement guidance for border services officers was provided in advance of or in line with implementation dates.

8.97 The Public Health Agency of Canada and the Canada Border Services Agency worked together to create a mobile application that would allow travellers to provide their contact information ahead of arriving at the border. The Canada Border Services Agency was able to implement the ArriveCAN application at all land ports of entry and 1 airport by the end of April. However, we found that the application did not have high usage rates. Just 7% of travellers used the application to provide their contact information in the application’s first 2 months of use. To increase the volume of contact information provided electronically, use of the application became mandatory for incoming air travellers in November 2020.

Discretion in applying exemptions

8.98 The Public Health Agency of Canada and the Canada Border Services Agency worked together to develop guidance for border services officers. To enforce the prohibitions on entry to the country, border services officers were responsible for determining whether travel was discretionary or not, and whether a traveller was exempt from mandatory quarantine for a particular reason. Exemptions had to be verified for each essential worker, relying on the judgment of border services officers. Enforcement guidance was highly technical and changed frequently because of the rapidly evolving orders. This may have led to inconsistencies in the processing of some travellers at the border.

8.99 We found that the Canada Border Services Agency had not verified whether border services officers had properly exercised their judgment in determining the exemptions for essential workers for entry into Canada and for mandatory quarantine. This is important for the consistent application of emergency orders to incoming travellers.

8.100 Recommendation. The Canada Border Services Agency, in collaboration with the Public Health Agency of Canada, should ensure that border services officers have the appropriate guidance and tools to enforce border control measures imposed to limit the spread of the virus that causes COVID‑19. Furthermore, because border control measures regarding entry and mandatory quarantine continue to evolve, the Canada Border Services Agency should conduct a review of decisions related to essential workers to ensure that border services officers are properly applying exemptions. The findings from this review should be used to adjust existing and future guidance for the enforcement of emergency orders.

The agency’s response. Agreed. The Canada Border Services Agency, through its border task force, has expanded its support to front-line border services officers beyond the existing operational guideline bulletins; live support access for 24 hours a day, 7 days a week; and regular case reviews. In addition, the agency has supplemented support by conducting detailed technical briefings prior to the implementation of new or amended orders-in-council. The objective is to support the accurate implementation of new provisions and ensure clarity for front-line staff.

The agency has established a process to monitor decisions made by border services officers as they relate to the application of orders-in-council for essential workers. The agency will continue to utilize this information to inform adjustments or reviews that may be required of the orders-in-council.

The agency’s border task force will develop a training tool by June 2021 to assist front-line officers in understanding the complexities of the orders-in-council.

The Canada Border Services Agency and the Public Health Agency of Canada have consulted regularly with each other on interpretations of the orders-in-council and will continue to collaborate on future adjustments and improvements.

Enforcement of mandatory quarantine was limited

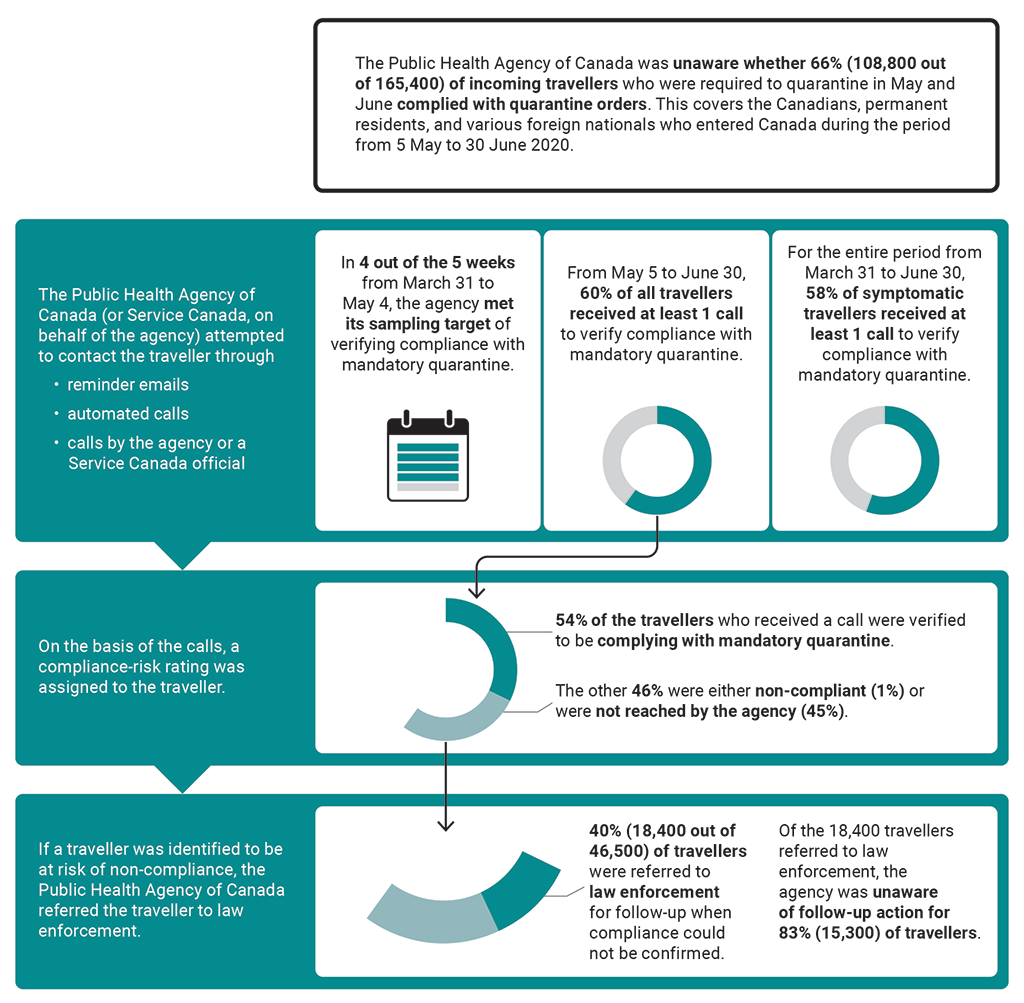

8.101 We found that, during the period from 31 March to 30 June 2020, the Public Health Agency of Canada did not always meet the targets it set to verify whether travellers subject to the mandatory 14-day quarantine upon entering Canada were following the quarantine orders.

8.102 We found that because of limitations of public health information, the agency could not track new cases of COVID‑19 to see if they could be connected to travellers who may not have followed the quarantine orders. Of the individuals considered to be at risk of non-compliance, the agency referred only 40% to law enforcement and did not know whether law enforcement actually contacted them. The agency had not contemplated or planned for mandatory quarantine on a nationwide scale and, as a result, had to increase capacity to verify compliance.

8.103 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics: