2015 March Report of the Auditor General of Canada Corrections in Yukon—Department of Justice

2015 March Report of the Auditor General of Canada Corrections in Yukon—Department of Justice

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

- Offender management

- The Department is not adequately preparing offenders for successful reintegration into the community

- The Department is not adequately managing many aspects of community supervision

- The Department is not yet meeting its obligations to incorporate the cultural heritage and needs of Yukon First Nations into its programs and services

- Facility management

- Offender management

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- List of Recommendations

- Exhibits:

- 1—The Department has programs and services to help rehabilitate offenders

- 2—There are gaps in the case management of offenders in the Whitehorse Correctional Centre

- 3—There are gaps in the case management of offenders under community supervision

- 4—Most offenders were not offered all core programs identified for them

Introduction

Background

1. The Department of Justice is responsible for correctional services in Yukon, as outlined in the Corrections Act (2009) and its regulations. Under the Act, the Department must develop and provide access to programs and services that promote accountability and behavioural change so that offenders may be rehabilitated, healed, and reintegrated into the community. Mental health services for offenders are administered under the Mental Health Act (2002).

Inmate on remand—A person who has been charged with an offence and ordered by the court to be detained in custody while awaiting a further court appearance.

2. The territory’s correctional facility—the Whitehorse Correctional Centre—houses male and female inmates on remand and those who have been sentenced to jail terms of less than two years. The Corrections Branch of the Department of Justice is responsible for supervising inmates incarcerated in the Whitehorse Correctional Centre. It is also responsible for providing rehabilitation programs and services to sentenced inmates.

Individual on bail—A person who has been charged with an offence and ordered by the court to be supervised in the community while awaiting a further court appearance.

3. The Offender Supervision and Services unit of the Corrections Branch is responsible for supervising offenders in the community who are on probation or serving conditional sentences. It is also responsible for providing these offenders with rehabilitation programs and services and for supervising individuals on bail.

4. Corrections is a significant issue in Yukon, as crime rates in the territory are among the highest in Canada. Yukon’s 2012 crime rate was the third highest in the country.

5. In the 2013–14 fiscal year, the Whitehorse Correctional Centre had 732 admissions, including both remanded and sentenced individuals. The Offender Supervision and Services unit had 1,003 admissions of individuals on probation orders, conditional sentences, and bail orders. The average sentence was about 30 days for women and about 87 days for men. The majority of offenders in Yukon are male and of First Nations descent, and half are from communities outside of Whitehorse.

6. In 2013–14, more than $14.6 million was allocated to correctional services within the Department of Justice. This represented 22 percent of the Department’s budget and included

- about $10.6 million directly related to custodial sentences;

- about $1.9 million directly related to community supervision; and

- about $2.1 million for other community and custodial programs and services, such as community justice initiatives.

7. The Whitehorse Correctional Centre has approximately 80 full-time employees. Offender Supervision and Services, which is responsible for community supervision, has approximately 16 full-time employees.

8. In 2004, the Department began a process of correctional redevelopment in the territory. Consultations on correctional redevelopment were co-chaired by the Government of Yukon, the Department of Justice, and the Council of Yukon First Nations. The process resulted in the development of a new Corrections Act in 2009, intended to provide a responsive approach to corrections that pairs the protection of society with the promotion of rehabilitation, healing, and reintegration for offenders. A key priority identified in the correctional redevelopment process was that the existing correctional centre be replaced. The new Whitehorse Correctional Centre opened in March 2012.

9. The Yukon justice system emphasizes using community supervision of offenders over incarceration. The cost of keeping inmates in the Whitehorse Correctional Centre is 20 to 25 times higher than the cost of supervising offenders in the community.

10. The Department of Justice faces several challenges in managing corrections. Evidence suggests that Yukon has a prevalence of mental health issues and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder that is estimated to be much higher in the corrections population than in the non-corrections population. Further, an estimated 90 percent of offenders have problems with substance abuse.

11. Programs and services for mental health, substance abuse, and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder are limited in the territory, particularly in communities outside of Whitehorse. These limited resources are a significant challenge to the Department in delivering its mandate.

12. The Corrections Act requires the Department to work with First Nations to develop and deliver correctional programs and services that incorporate the cultural heritage and needs of offenders who are First Nation persons. There are 14 Yukon First Nations with cultural distinctions that must be respected. The Department told us that there are capacity challenges and conflicting priorities for First Nations to assist with the development of Yukon-specific First Nations programs to deal with criminal behaviour.

Focus of the audit

13. This audit focused on whether the Department of Justice was meeting its key responsibilities for offenders within the corrections system. We audited how the Department met these responsibilities

- for offenders in the Whitehorse Correctional Centre, and

- for offenders under community supervision.

14. We also examined whether the Department adequately planned for and operated the Whitehorse Correctional Centre.

15. This audit is important because the corrections system plays a critical role in protecting the public by supervising offenders in custody and those serving community sentences, with a view to their rehabilitation.

16. We did not examine court services, sentencing decisions, or community justice programs. We also did not audit the management of youth in custody.

17. More details about the audit objectives, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Offender management

18. Overall, we found that the Department is missing two key opportunities to improve offenders’ chances for rehabilitation and successful reintegration into the community: the first is when offenders begin serving their custodial sentence in the Whitehorse Correctional Centre, and the second is when they make the transition to serve their sentence under community supervision. The Department is required by its offender case management policies to identify offenders’ rehabilitation needs and major areas of risk of reoffending, and to provide them with programs that have been identified in their case plans to meet those needs.

19. However, we found that most offenders who were not offered the core rehabilitation programs identified for them while in the correctional centre were also not offered the programs while they were under community supervision. As a result, those offenders completed both their custodial and community sentences without getting access to all the core rehabilitation programs identified for them.

20. This finding matters because the primary goal of Yukon Correctional Services is the safe reintegration of offenders into communities as law-abiding citizens. By not doing all that is required to help offenders with their rehabilitation, healing, and reintegration into the community, the Department is not meeting this goal.

21. To support the rehabilitation of offenders who serve a custodial sentence of 90 days or more followed by a sentence under community supervision, the Department uses a collaborative approach to case planning and offender management. Offenders are managed from the time they are admitted to the Whitehorse Correctional Centre until they have completed their sentence in the community. Case managers at the correctional centre collaborate with probation officers in the community.

22. Case management is a continuous process that includes gathering information about an offender, assessing the offender’s rehabilitation needs and risk of committing a crime, creating a case plan, and reviewing the offender’s progress against the plan at regular intervals. It also involves ensuring that the types of programs offered correspond to the offender’s identified needs and risk.

23. Needs and risk assessment is a step in case management that is taken at first contact with the offender; it forms the basis of the case management plan. The Department’s case management policies require an offender’s needs and risk to be reassessed at least every six months. The case management plan is used to document issues related to the offender’s rehabilitation needs and risk of committing a crime. The plan also includes required actions and dates related to supporting the offender’s rehabilitation. For example, it notes programs and services that the offender should have, based on the offender’s needs and risk assessment.

24. The Department has two types of rehabilitation programs for offenders: core programs and non-core programs. Core programs are those that have been shown through research to be effective in reducing the likelihood of reoffending. All other programs that the Department offers offenders—for example, life skills and job readiness programs—are referred to in this report as non-core programs. See Exhibit 1 for a list of the Department’s core programs and some of its non-core programs and services.

Exhibit 1—The Department has programs and services to help rehabilitate offenders

| Core programs | Non-core programs and services (including referrals) |

|---|---|

|

|

The Department is not adequately preparing offenders for successful reintegration into the community

25. The Department did not meet key requirements of the case management process for the offenders in our sample, such as offering the offenders core rehabilitation programs. This was particularly the case when the offenders were under community supervision. This means that, despite two opportunities to do so, the Department is not adequately preparing offenders for successful reintegration into the community.

26. Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

- case management in the Whitehorse Correctional Centre,

- core programs in the correctional centre,

- transition planning,

- case management in community supervision, and

- core programs in community supervision.

27. This finding matters because the primary goal of correctional case management is to reduce offending by encouraging and enabling behavioural change. By not doing all that is required by its case management policies to help offenders with their rehabilitation, healing, and reintegration into the community, the Department is not meeting this goal. Moreover, because more offenders in Yukon are sentenced to community supervision than incarceration, it is particularly important that the Department adequately support the rehabilitation of offenders who are under community supervision to reduce their chances of reoffending. Without adequate rehabilitation, offenders may pose a risk to the safety of the community.

28. Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 52 and 53.

29. What we examined. We examined whether key steps of the case management process for offenders had been followed as required by the Department’s policy manuals. To do so, we reviewed the case management files of a random sample of 25 offenders who were sentenced to the Whitehorse Correctional Centre for 90 days or more between April 2012 and March 2013, with a period of community supervision to follow. This was the same fiscal year in which the new correctional centre opened.

30. Our examination included whether the Department had offered these 25 offenders core rehabilitation programs intended to address their identified needs and risk. We also looked at whether the Department provided the offenders with access to its non-core programs and services.

31. Case management in the Whitehorse Correctional Centre. In its case management of offenders, the Department is required according to its policy manuals to assess an offender’s rehabilitation needs and risk of reoffending and then use that assessment to develop a case plan for the offender. The case plan should include programs and services that address the offender’s identified major areas of needs and risk.

32. We found gaps in the case management of offenders in the correctional centre. For example, case managers had completed needs and risk assessments on a timely basis for only 16 of 24 of these offenders. This assessment is supposed to form the basis of the case plan. See Exhibit 2 for our specific findings on case management in the correctional centre.

Exhibit 2—There are gaps in the case management of offenders in the Whitehorse Correctional Centre

| Case management requirements | Completed assessments or plans |

|---|---|

| Assess, on a timely basis, an offender’s needs and risk of committing crime | 92% (22 of 24 files * ) completed, but only 67% (16 of 24 files) completed on time |

| Develop case plan | 88% (21 of 24 files) |

| Review and update case plan on a timely basis | Not determined (dates were missing from original case plans) |

| Develop transition plan | 75% (18 of 24 files) |

| Conduct return-to-custody interview | 0% (0 of 14 files * ) |

* The requirement applied to this number of files.

33. In not meeting its case management requirements, the Department is not doing all it can to help the offenders successfully reintegrate into the community. For example, when the Department does not assess or update offenders’ needs and risk on a timely basis, offenders may miss the opportunity to take the programs they need.

34. Core programs in the correctional centre. One of the key strategies of the corrections redevelopment initiative was the adoption of evidence-based core programs. The Department selected these programs because it found they had been proven effective in reducing reoffending in other jurisdictions. The correctional centre is the Department’s first opportunity to provide the offenders with programs designed to help rehabilitate them.

35. We found that case managers at the correctional centre had developed case plans for 21 of the offenders in our sample. The case plans identified core and non-core programs and services that the offenders needed. We found that the Department provided the offenders in our sample with access to many of its non-core programs and services. However, 13 of these 21 offenders were not offered all the core programs that had been identified for them.

36. We found that the core program that offenders were least likely to be offered after it had been identified as one they needed was the Respectful Relationships program. The program is intended to teach offenders self-management and problem-solving skills to reduce their potential for violence in a relationship. Of the nine offenders in our sample who were identified as needing the Respectful Relationships program, only three were offered the program.

37. We noted that in 12 of the 13 offender files in which the offenders were not offered the core programs, the reason noted in the files was that the programs were not delivered in the offenders’ living units in the correctional centre during their sentences. The Department told us that there are other reasons that core programs might not be offered to the offenders. For example, an offender might not be cognitively ready to start a program. In such cases, the Department tries to find services that will help prepare the offender to take the core programs at a later date.

38. The Department also told us that it cannot provide all of the programming identified in the offenders’ case plans. Neither does it currently prioritize offenders’ most critical programming needs while they are in the correctional centre.

39. Nevertheless, we found that offenders who were not offered the core programs identified for them while in the correctional centre had very little chance of being offered them while they were under community supervision. While the Department told us that it is not optimal to deliver all programs to offenders while they are in custody, it is important that the Department maximize the number of programs delivered in the correctional centre, until such time as more programming is available in the communities. See the section on core programs in community supervision at paragraph 49.

40. Transition planning. When an offender is released from the Whitehorse Correctional Centre to serve a sentence under community supervision (for example, probation), the Department is required to develop a transition plan for the offender. Transition plans are developed in collaboration with case managers and probation officers. The plans are used to determine barriers for the offenders that could prevent their successful reintegration into the community, such as a lack of housing or finances.

41. We found that no transition plans had been developed for 6 of 24 inmates (25 percent). This means that these offenders—who had yet to complete their sentences under community supervision—were released into the community without a plan to identify what support they might need to succeed in making this transition. For example, one offender in our sample was noted as having a drug and alcohol problem and no job. Yet, he was released without a transition plan in place to deal with his identified issues.

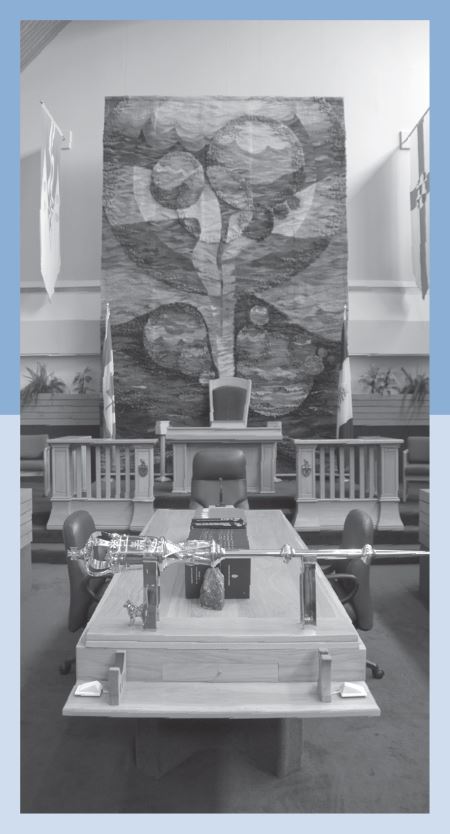

42. Case management in community supervision. Community supervision is the Department’s second opportunity to help rehabilitate offenders. Like the case management process in the correctional centre, the Department’s policies require that a needs and risk assessment as well as a case plan be completed for the offender. The probation officer can use a needs and risk assessment that was completed while the offender was in the correctional centre if it was done within the past six months. Otherwise, a new assessment is required.

43. While we found gaps in the case management of offenders in the Whitehorse Correctional Centre, we found even larger gaps in the case management of these offenders once they entered community supervision. For example, 88 percent of offenders in the correctional centre had case plans, but only 38 percent of offenders in community supervision had case plans. See Exhibit 3 for our specific findings on case management during community supervision.

Exhibit 3—There are gaps in the case management of offenders under community supervision

| Case management requirements | Completed assessments or plans |

|---|---|

| Assess or reassess, on a timely basis, an offender’s needs and risk of committing crime | 88% (22 of 25 files) completed, but only 48% (12 of 25 files) completed on time |

| Conduct Risk for Sexual Violence Protocol | 25% (1 of 4 files * ) |

| Conduct Spousal Assault Risk Assessment | 33% (3 of 9 files) |

| Develop case plan | 38% (8 of 21 files) |

| Review and update case plan on a timely basis | 75% (3 of 4 files ** ) |

44. We found that needs and risk assessments had not been updated as required by the Department’s policy; the information in the assessments was as much as five months out of date. This means that the probation officers were making decisions about the offenders’ supervision without up-to-date information.

45. For offenders convicted of either sexual assault or domestic violence who are entering into community supervision, the Department is required to conduct two additional risk assessments: the Risk for Sexual Violence Protocol and the Spousal Assault Risk Assessment.

46. These risk assessments are important because they are intended to help determine interventions the offenders might require to reduce the risk of further sexual assault or domestic violence offences. They are also used to determine an offender’s level of risk for reoffending. This is particularly important since the offenders are returning to the community when they enter community supervision.

47. Four of the 25 offenders in our sample had been convicted of sexual assault. We found that only one of the four required Risk for Sexual Violence Protocol assessments had been completed for these offenders.

48. Nine of the 25 offenders in our sample had been convicted of crimes that included domestic violence. We found that only three of the nine required Spousal Assault Risk Assessments had been completed for these offenders.

49. Core programs in community supervision. We looked at whether the 13 offenders who were not offered all the core programs identified in their case plans while they were in the correctional centre were offered the remaining programs after they transitioned to community supervision. We found that only 1 of 13 offenders was offered all the programs. This means that offenders who did not attend core programs while in the correctional centre had very little chance of doing so while under community supervision.

50. We found that there were various reasons why the 12 offenders in our sample were not offered all the core programs identified for them. The most common reason the offenders were not directed by their probation officers to take the programs was that the programs were not available in the community where the offender lived.

51. In our view, the fact that offenders had little chance of being offered core programs while under community supervision makes it all the more important that the Department make the best use of its first opportunity to deliver the programs to offenders while they are in the correctional centre. Otherwise, as indicated in Exhibit 4, most offenders are not likely to be offered all core programs despite going through incarceration and community supervision.

Exhibit 4—Most offenders were not offered all core programs identified for them

| What offenders were offered | Percentage of offenders |

|---|---|

| All programs identified for them | 43% (9 of 21 offenders * ) |

| Some programs identified for them | 48% (10 of 21 offenders) |

| None of the programs identified for them | 9% (2 of 21 offenders) |

* In 4 other files, there were no case plans in the file to identify programs for the offenders.

52. Recommendation. The Department of Justice should comply with its case management policies both in the Whitehorse Correctional Centre and in community supervision for the purpose of helping to rehabilitate, heal, and reintegrate offenders by

- completing needs and risk assessments for all offenders,

- developing case plans and ensuring that they are reviewed and updated as required,

- developing transition plans for all offenders, and

- conducting return-to-custody interviews with offenders who reoffend and are returned to custody at the Whitehorse Correctional Centre.

The Department’s response. Agreed. In 2012 and 2013, the majority of resources in the Corrections Branch were focused on transition to the new correctional centre and stabilization of operations. The Corrections Branch identified deficits in policy compliance through internal reviews and responded by implementing quality assurance processes. These processes currently comprise biannual reviews of policy compliance for integrated offender management files in each of the aforementioned areas: risk assessments, case management and transition planning, and return-to-custody interviews. The Corrections Branch will continue to monitor policy compliance, with an objective of achieving full compliance in the 2015–16 fiscal year.

53. Recommendation. The Department of Justice should ensure that its core rehabilitation programs are accessible to offenders in the Whitehorse Correctional Centre as well as in the community. This includes making sure that offenders who live outside of Whitehorse have access to the programs.

The Department’s response. Agreed. In 2012 and 2013, the majority of resources in the Corrections Branch were focused on transition to the new correctional centre and stabilization of operations. Following this transition period, providing programming to offenders became a priority, with yearly program delivery planning and monitoring. Programming at Whitehorse Correctional Centre has increased, and statistics will be publicly reported beginning in the 2015–16 fiscal year. There continue to be a number of challenges with the provision of programming for offenders under community supervision orders. The Department will develop a strategy for addressing these shortfalls by the end of the 2014–15 fiscal year, with targeted implementation of initiatives in the 2015–16 fiscal year. The Department has increased capacity in Dawson City from a half-time to a full-time probation officer. The Department is now examining capacity in the Southern Yukon Territory with a view to increasing probation services in the new fiscal year.

The Department is not adequately managing many aspects of community supervision

54. We found that the Department does not adequately manage many of the aspects of community supervision that we examined, such as the management of offenders on probation and support for probation officers. While probation officers are responsible for directly supervising and supporting offenders under community supervision, it is the Department’s responsibility overall to manage the area of community supervision. This means that the Department is not making the best use of its second and last opportunity to help rehabilitate these offenders before they leave the corrections system.

55. Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

- enforcement of court-ordered conditions,

- support for probation officers,

- access to core rehabilitation programs outside Whitehorse,

- the need for management attention, and

- mental health services.

56. Adequate supervision and support of offenders in the community are important for public safety, for rehabilitating and reintegrating offenders into the community, and for fulfilling the expectations of the court.

57. More offenders in Yukon are sentenced to community supervision than to incarceration. For example, in the 2013–14 fiscal year, 378 offenders began sentences of community supervision, whereas only 195 offenders began sentences of incarceration. Further, community supervision sentences are typically longer than sentences of incarceration. Therefore, it is particularly important that the Department adequately support offenders who are serving sentences under community supervision.

58. Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 74, 75, and 79.

59. What we examined. We examined whether the Department’s probation officers monitored offenders’ compliance with their court-ordered conditions and whether they responded to any instances of non-compliance. In addition to supervising the offenders, probation officers are expected to support the offenders by directing them to take programs intended to help rehabilitate them. We looked at the tools and resources the Department had in place for probation officers to do this work.

60. Court orders can have a variety of conditions attached to them. These can include requirements such as curfews that offenders must meet. They can also include a requirement for the offender to take programs as directed by the probation officer. This requirement is one that probation officers carry out through the case management process discussed in paragraphs 42 to 51 of this report.

61. Enforcement of court-ordered conditions. The goal of community supervision is the safe reintegration of offenders into the community as law-abiding citizens. The Department has 11 probation officers who are responsible for supervising and supporting offenders to ensure that offenders follow the conditions in their court orders.

62. While supervising an offender, the probation officer must respond when offenders breach the conditions of a court order. In our review of offenders’ files, we found that 18 of the 19 files that had breaches included evidence that the probation officer had responded to the breach.

63. While probation officers’ supervisory duties used to be their primary role, there has been an increasing emphasis on supportive duties. Supportive duties are more closely related to the philosophy of correctional redevelopment. They are also aligned with the Department’s responsibility to help rehabilitate and reintegrate the offender into the community.

64. However, we found that probation officers were not adequately carrying out their supportive duties. We noted this in our section on case management in community supervision (paragraphs 42–51) and in our file review results in Exhibit 3. This included not conducting spousal assault or sexual violence risk assessments or developing case plans. For example, in our sample, only 8 of 21 case plans were developed for offenders.

65. Support for probation officers. We looked at the support the Department provides to probation officers to help them carry out their responsibility to support offenders. We reviewed tools and resources such as policy and procedure manuals and training to determine whether they were adequate. We also interviewed probation officers to obtain their perspective on whether the tools and resources were adequate. In addition, we conducted a survey with the Department’s 11 probation officers to allow them to confirm their views on the Department’s support for them. Nine of the probation officers responded to the survey.

66. The probation officers identified a number of areas where they felt they needed more support. Seven probation officers told us that they did not feel they had received the training they thought they needed to carry out their job. For example, some told us that they had not received enough training on how to write court reports. The reports are important because they are intended to provide judges with information to help them in making decisions about offenders.

67. We found that the Department delivered training on the cultural heritage of Yukon First Nations to only 2 of its 11 probation officers. The training was delivered in September 2014. The Department is required by the Corrections Act to provide probation officers with this training. See our recommendation on this at paragraph 75.

68. Seven probation officers meet with offenders who live in rural communities outside of Whitehorse. Four of the seven told us that they did not have access to reliable physical space for meeting with those offenders. We spoke with senior management in the Department who confirmed that reliable physical space for some probation officers was a problem. This absence of reliable physical space affects not only the physical security of the probation officers, but also the confidentiality of offenders.

69. Access to core rehabilitation programs outside Whitehorse. In addition to the lack of support provided to probation officers, the Department is not providing offenders under community supervision with adequate access to its evidence-based core rehabilitation programs. These programs are not offered in most communities outside Whitehorse. This is a significant shortfall, since half of the offenders in Yukon come from communities outside of Whitehorse.

70. The need for management attention. The Department is aware of some of the issues in community supervision that we have raised—for example, the lack of reliable physical space in rural communities outside of Whitehorse for probation officers to meet with offenders.

71. The Department also conducted internal reviews in 2011, 2012, and 2013 that assessed whether some of the same case management processes we looked at were being followed. Where we looked at the same case management processes, we found weaknesses similar to those that the Department had found.

72. Both the Department’s findings and ours point to the need for management to address the weaknesses in community supervision. More sentenced offenders are supervised in the community than in the correctional centre. Community supervision is also the Department’s second opportunity to help rehabilitate offenders who have served a custodial sentence in the correctional centre.

73. Further, the increased emphasis on the need for probation officers to play a supportive role in the offender’s rehabilitation aligns with the philosophy of correctional redevelopment. For all of these reasons, it is particularly important that the Department give community supervision the attention it needs.

74. Recommendation. The Department of Justice should review its support for probation officers and identify the tools and resources—such as training and clear policies and procedures—that the probation officers need to help them in their case management of offenders.

The Department’s response. Agreed. The Department is updating its online training for probation officers and will require all officers to complete that training in the 2015–16 fiscal year. The Department will conduct an exercise to identify and remedy any areas of policy that the probation officers feel are unclear at this time. It will also undertake an exercise to develop detailed procedures to accompany policies. The Department will continue its practice of engaging staff in the development of the yearly training schedule and focus specific attention on identifying individual training in probation officer performance plans. All initiatives will include mandatory staff involvement and documentation of probation officer participation. The Department has recently hired a supervisor to provide increased support to probation officers.

75. Recommendation. The Department of Justice should provide training in First Nations cultural heritage to all probation officers.

The Department’s response. Agreed. The Yukon First Nations History and Cultures training was developed to meet strategic government recommendations and commitments. The government necessarily prioritized delivery of this training, and it was first made available to the Corrections Branch in the fall of 2014. The Department is committed to providing this training to all Corrections frontline staff: correctional officers and probation officers. The Department has already moved ahead on this commitment and will complete this objective by the end of the 2015–16 fiscal year.

76. Mental health services. The Yukon corrections population has an estimated prevalence of mental health issues that is nearly three times that of the non-corrections population. Therefore, it is critical that these offenders are provided with the services they need to facilitate their rehabilitation and safe reintegration into the community.

77. We found that the Department has some mental health services in place in the Whitehorse Correctional Centre, such as assessment and counselling services. In our review of offender files, we noted that mental health issues had been identified in six of the files. We also found evidence that those offenders had been offered access to mental health services.

78. When offenders are under community supervision, the Department of Health and Social Services is responsible for providing them with the same mental health services that they provide to all Yukoners. With a view to providing offenders with mental health services outside the Whitehorse Correctional Centre, the Department of Justice and the Department of Health and Social Services are working together to develop a Memorandum of Understanding. The intention of the Memorandum of Understanding would be to help to define the collaborative work needed in the ongoing case management of common clients who have diagnosed mental health issues.

79. Recommendation. The Department of Justice should continue to work with the Department of Health and Social Services to collaborate on providing mental health services to offenders who need them.

The Department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Justice intends to enter into a Memorandum of Understanding between its Corrections Branch and Mental Health Services within the Department of Health and Social Services by the end of the 2015–16 fiscal year. The Department of Justice is committed to working collaboratively with the Department of Health and Social Services and to developing a protocol to better meet the needs of common clients.

The Department is not yet meeting its obligations to incorporate the cultural heritage and needs of Yukon First Nations into its programs and services

80. We found that the Department is not yet meeting its obligations under the Corrections Act to incorporate the cultural heritage and needs of Yukon First Nations into their programs and services. While some First Nations cultural programs are provided to inmates at the Whitehorse Correctional Centre, none of the Department’s evidence-based core rehabilitation programs incorporate the cultural heritage of Yukon First Nations.

81. Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses First Nations programs.

82. This finding is important because between 70 and 90 percent of offenders in Yukon are members of a Yukon First Nation. The Corrections Act states that the Corrections Branch works in collaboration with Yukon First Nations in developing and delivering correctional services and programs that incorporate the cultural heritage of Yukon First Nations and address the needs of offenders who are First Nation persons.

83. Our recommendation in this area of examination appears in paragraph 88.

84. What we examined. We examined whether the Department of Justice’s correctional programs and services incorporate the cultural heritage and needs of offenders who are members of a Yukon First Nation.

85. First Nations programs. The Corrections Act states that the Corrections Branch works in collaboration with Yukon First Nations in developing and delivering correctional services and programs that incorporate the cultural heritage of Yukon First Nations and address the needs of offenders who are First Nation persons.

86. The Department faces challenges in meeting this requirement of the Act. Department officials told us that there are significant capacity issues both within the Department and within the First Nations communities to participate in developing and delivering programs for offenders. Further, the core programs that the Department delivers are the intellectual property of other jurisdictions and therefore cannot easily be modified. Finally, there are 14 Yukon First Nations with cultural distinctions that must be respected.

87. We found that the Department has made some effort to incorporate First Nations cultural heritage into its programs. The Department developed a First Nations program strategy to expand access to First Nations programs in the Whitehorse Correctional Centre. We found that the Department offers First Nations cultural programs at the Whitehorse Correctional Centre, such as language and carving courses. However, we found that the Department has not adapted its core rehabilitation programs—for example, Respectful Relationships—for offenders who are Yukon First Nation members. Further, it has not assessed whether these core programs meet the needs of Yukon First Nations offenders. It is important to determine whether the programs are effective in reducing offending in Yukon First Nations offenders because the majority of offenders in the Yukon correctional system are members of a Yukon First Nation.

88. Recommendation. The Department of Justice should take steps to address the challenges it faces in delivering correctional services and programs that incorporate the cultural heritage of Yukon First Nations and meet the needs of offenders who are First Nation members.

The Department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Justice is keenly aware of the challenges presented in incorporating Yukon First Nations culture in correctional programming. The Department remains committed to continuing its strategic planning and implementation of initiatives to meet this challenge over the next five years. The Department of Justice continues to take steps toward incorporating Yukon First Nations heritage by embedding cultural practices into the fabric of corrections operations.

Facility management

89. Overall, we found that the Department of Justice adequately planned the Whitehorse Correctional Centre. The facility was designed and built to meet the territory’s identified current and future needs for housing inmates, which included taking into account the Department’s requirements for space to ensure the safe and secure custody of inmates and to meet its program obligations for inmates. Within the operations of the correctional centre, we also found that the Department is working to address recruitment challenges and its reliance on overtime. This is important because the Department has a duty to house inmates and spend public funds in a cost-effective manner.

90. The process of assessing needs for accommodating offenders in Yukon began in 2004 as part of a wider correctional redevelopment process in the territory.

91. Consultation meetings were held over a 15-month period. The consultations included public meetings as well as meetings with various groups and organizations; staff and inmates at the existing Whitehorse Correctional Centre; and Yukon First Nations.

92. A key priority identified in the correctional redevelopment process was that the existing correctional centre, which was built in 1967, should be replaced. The new Whitehorse Correctional Centre opened in March 2012, at a cost of about $70 million. It can house between 84 and 190 inmates, depending on whether one or two inmates are housed at one time in regular living units and whether all specialized living units (for example, segregation) are occupied.

The Whitehorse Correctional Centre was designed and built to meet the territory’s identified current and future needs for housing inmates

93. We found that the Whitehorse Correctional Centre was designed and built to meet the territory’s identified current and future needs for housing inmates. This included taking into account its requirements for space in living units and program areas to ensure the safe and secure custody of inmates and to meet its program obligations for inmates.

94. Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses current and future facility needs for inmates in planning for the Whitehorse Correctional Centre.

95. This finding matters because the Department has a duty to house inmates while at the same time spending public funds in a cost-effective manner.

96. We made no recommendations in this area of examination.

97. What we examined. We examined whether the Department had identified and addressed current and future facility needs for inmates in planning for the Whitehorse Correctional Centre.

98. Current and future facility needs for inmates in planning for the Whitehorse Correctional Centre. We found that design parameters and program components were developed and evaluated as part of assessing options for building a new correctional centre. The need to consider justice principles was highlighted as part of the options document—for example, that the correctional system would incorporate Yukon First Nations cultural traditions and practices.

99. In addition, the specific needs for operating components such as security and safety, living units, and program areas were identified in planning. The Department identified inmates’ profiles (for example, the percentage of inmates with First Nations ancestry) and forecasts of the number of inmates expected for 2008–18 (between 71 and 77 individuals, using a high-growth projection).

100. We compared the identified building and operating requirements with what is in place at the Whitehorse Correctional Centre and found that they were aligned, with the exception of the separation of remanded and sentenced inmates. The Department decided not to separate remanded and sentenced inmates. Senior management told us that this decision was made to reduce costs and to have more flexibility in managing the inmate population. For example, the Department has to be able to separate inmates who cannot be safely housed together, whether they are remanded or sentenced inmates. It was also thought that mixing remanded and sentenced inmates would allow remanded inmates to benefit from the option of taking programming that would be offered in the living units of sentenced offenders.

The Department is working to address human resource challenges at the Whitehorse Correctional Centre

101. We found that the Department has taken steps to address recruitment challenges and its reliance on overtime at the Whitehorse Correctional Centre. We also found that, for the most part, staff members at the Whitehorse Correctional Centre are provided with required training.

102. Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

103. This finding matters because having the right number of trained staff is essential to operate a correctional facility such as the Whitehorse Correctional Centre 24 hours a day, seven days a week. In addition, personnel costs represent over 80 percent of the facility’s operating budget, so it is important that those costs are managed efficiently.

104. We made no recommendations in this area of examination.

105. What we examined. We examined whether the Department had identified the required number and types of staff for the correctional centre, and whether it had addressed identified gaps in staffing. We also examined whether the Department had assessed levels of overtime usage and had taken steps to manage overtime. Finally, we examined whether the Department tracks whether staff members have taken the training they require, including training in the cultural heritage of Yukon First Nations.

106. Human resource planning and staffing. We found that the Department has identified the number and type of staff required to run the Whitehorse Correctional Centre. For example, it has determined that 23 correctional officers and managers are required to staff the facility for a 24-hour period.

107. The Department has also identified staffing gaps and is taking some measures to address these gaps. For example, following the development of a human resource strategy, as part of correctional redevelopment, it introduced a new staffing approach to help increase recruitment and reduce overtime costs.

108. Nevertheless, staffing remains an ongoing challenge for the Department, particularly since the correctional centre must operate on a 24-hour basis, 365 days a year. The Department relies on on-call staff and overtime to fill staffing gaps.

109. We found that the Department monitors and manages its overtime costs. For example, it has analyzed how much it spends on overtime at the correctional centre and the reasons overtime is used.

110. Training. The Department’s policy manual requires that correctional officers take Correctional Officer Basic Training when they are hired. The Correctional Officer Basic Training, which is about 200 hours, was updated in 2014. The Department also has refresher training for courses such as first aid and use of force.

111. We examined whether correctional officers have taken the required Correctional Officer Basic Training, since it is the Department’s main training for its correctional officers before they start working with inmates. We also looked at whether training was provided for correctional officers on the cultural heritage of Yukon First Nations.

112. We found that, for the most part, correctional officers who were working at the correctional centre in 2013–14 had taken the required Correctional Officer Basic Training.

113. We found that training in First Nations cultural heritage was provided as a three-hour component of Correctional Officer Basic Training. Department officials told us that they intend to deliver a new 16-hour course on the cultural heritage of Yukon First Nations to correctional officers, starting in November 2014. We also found that the correctional centre has a training strategy outlining action items, milestones, progress to date on the action items, and expected outcomes.

Conclusion

114. We concluded that the Department adequately planned for and operated the Whitehorse Correctional Centre. However, it did not adequately manage offenders in compliance with key requirements. Therefore, we concluded that the Department of Justice has not met its key responsibilities for offenders within the corrections system.

About the Audit

The Office of the Auditor General’s responsibility was to conduct an independent examination of Yukon Corrections to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist the Legislative Assembly in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs.

All of the audit work in this report was conducted in accordance with the standards for assurance engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance. While the Office adopts these standards as the minimum requirement for our audits, we also draw upon the standards and practices of other disciplines.

As part of our regular audit process, we obtained management’s confirmation that the findings reported in this report are factually based.

Objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether the Department of Justice was meeting key responsibilities for offenders within the corrections system. As part of our audit, we looked at whether the Department of Justice

- adequately planned for and operated the Whitehorse Correctional Centre to house inmates, and

- adequately managed offenders in the Whitehorse Correctional Centre and under community supervision in compliance with key requirements.

Scope and approach

The audit focused on the Corrections Branch of the Department of Justice because that branch is responsible for implementing the Corrections Act. We examined how the Department manages offenders both while they are in the Whitehorse Correctional Centre and while they are under community supervision.

Our audit included interviews with Yukon First Nations and other key stakeholders, as well as with correctional officers, case managers, probation officers, and managers from the Department. We also conducted a survey with probation officers. Finally, we reviewed and analyzed documentation provided by the Department.

To assess whether the Department of Justice complied with key requirements of the Corrections Act and selected policies and procedures related to the management of offenders, we selected and tested a random sample of 25 files of offenders who had been sentenced to the Whitehorse Correctional Centre for 90 days or more between April 2012 and March 2013, followed by a period of community supervision. We chose to include offenders who had been sentenced to 90 days or more because the Department’s policy to provide needs and risk assessments and develop case plans does not apply to offenders who are sentenced for less than 90 days. The requirements included policies and procedures that the Department must follow in supervising and supporting offenders while the offenders are in the correctional centre as well as while they are under community supervision.

Criteria

To determine whether the Department of Justice is meeting key responsibilities for offenders within the corrections system; adequately planned for and operates the Whitehorse Correctional Centre to house inmates; and adequately manages offenders under community supervision and inmates in compliance with key requirements, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

The Department of Justice develops plans to identify and address current and future facility needs for inmates. |

|

|

The Department of Justice

|

|

|

The Department of Justice manages inmates consistent with its policies and procedures by

|

|

|

The Department of Justice has tools and resources in place to oversee and support offenders under community supervision. |

|

|

The Department of Justice manages offenders under community supervision consistent with its policies and procedures by

|

|

|

The Department of Justice monitors compliance with court-ordered conditions for offenders under community supervision. |

|

Management reviewed and accepted the suitability of the criteria used in the audit.

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period between 15 March 2012 and 1 September 2014. Audit work for this report was completed on 3 November 2014.

Audit team

Assistant Auditor General: Ronnie Campbell

Principal: Michelle Salvail

Lead auditor: Ruth Sullivan

Jenna Germaine

Maxine Leduc

Sean MacLennan

List of Recommendations

The following is a list of recommendations found in the report. The number in front of the recommendation indicates the paragraph where it appears in the report. The numbers in parentheses indicate the paragraphs where the topic is discussed.

Offender management

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

52. The Department of Justice should comply with its case management policies both in the Whitehorse Correctional Centre and in community supervision for the purpose of helping to rehabilitate, heal, and reintegrate offenders by

|

The Department’s response. Agreed. In 2012 and 2013, the majority of resources in the Corrections Branch were focused on transition to the new correctional centre and stabilization of operations. The Corrections Branch identified deficits in policy compliance through internal reviews and responded by implementing quality assurance processes. These processes currently comprise biannual reviews of policy compliance for integrated offender management files in each of the aforementioned areas: risk assessments, case management and transition planning, and return-to-custody interviews. The Corrections Branch will continue to monitor policy compliance, with an objective of achieving full compliance in the 2015–16 fiscal year. |

|

53. The Department of Justice should ensure that its core rehabilitation programs are accessible to offenders in the Whitehorse Correctional Centre as well as in the community. This includes making sure that offenders who live outside of Whitehorse have access to the programs. (25–51) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. In 2012 and 2013, the majority of resources in the Corrections Branch were focused on transition to the new correctional centre and stabilization of operations. Following this transition period, providing programming to offenders became a priority, with yearly program delivery planning and monitoring. Programming at Whitehorse Correctional Centre has increased, and statistics will be publicly reported beginning in the 2015–16 fiscal year. There continue to be a number of challenges with the provision of programming for offenders under community supervision orders. The Department will develop a strategy for addressing these shortfalls by the end of the 2014–15 fiscal year, with targeted implementation of initiatives in the 2015–16 fiscal year. The Department has increased capacity in Dawson City from a half-time to a full-time probation officer. The Department is now examining capacity in the Southern Yukon Territory with a view to increasing probation services in the new fiscal year. |

|

74. The Department of Justice should review its support for probation officers and identify the tools and resources—such as training and clear policies and procedures—that the probation officers need to help them in their case management of offenders. (54–73) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. The Department is updating its online training for probation officers and will require all officers to complete that training in the 2015–16 fiscal year. The Department will conduct an exercise to identify and remedy any areas of policy that the probation officers feel are unclear at this time. It will also undertake an exercise to develop detailed procedures to accompany policies. The Department will continue its practice of engaging staff in the development of the yearly training schedule and focus specific attention on identifying individual training in probation officer performance plans. All initiatives will include mandatory staff involvement and documentation of probation officer participation. The Department has recently hired a supervisor to provide increased support to probation officers. |

|

75. The Department of Justice should provide training in First Nations cultural heritage to all probation officers. (54–73) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. The Yukon First Nations History and Cultures training was developed to meet strategic government recommendations and commitments. The government necessarily prioritized delivery of this training, and it was first made available to the Corrections Branch in the fall of 2014. The Department is committed to providing this training to all Corrections frontline staff: correctional officers and probation officers. The Department has already moved ahead on this commitment and will complete this objective by the end of the 2015–16 fiscal year. |

|

79. The Department of Justice should continue to work with the Department of Health and Social Services to collaborate on providing mental health services to offenders who need them. (76–78) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Justice intends to enter into a Memorandum of Understanding between its Corrections Branch and Mental Health Services within the Department of Health and Social Services by the end of the 2015–16 fiscal year. The Department of Justice is committed to working collaboratively with the Department of Health and Social Services and to developing a protocol to better meet the needs of common clients. |

|

88. The Department of Justice should take steps to address the challenges it faces in delivering correctional services and programs that incorporate the cultural heritage of Yukon First Nations and meet the needs of offenders who are First Nation members. (80–87) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Justice is keenly aware of the challenges presented in incorporating Yukon First Nations culture in correctional programming. The Department remains committed to continuing its strategic planning and implementation of initiatives to meet this challenge over the next five years. The Department of Justice continues to take steps toward incorporating Yukon First Nations heritage by embedding cultural practices into the fabric of corrections operations. |

PDF Versions

To access the Portable Document Format (PDF) version you must have a PDF reader installed. If you do not already have such a reader, there are numerous PDF readers available for free download or for purchase on the Internet: