Lessons learned from 30 years of climate change challenges and opportunities in Canada

The Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development and the Auditor General of Canada have been reporting to Parliament on Canada’s climate change performance since 1998. However, mentions of climate change in audit reports started as early as 1985, delving into topics such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions, mitigating the effects of severe weather, adapting to the changing climate, phasing out fossil fuel subsidies, and developing sustainable infrastructure and clean energy technologies. We have audited Environment and Climate Change Canada and Natural Resources Canada most frequently on these topics, but we have also included Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada, Transport Canada, Health Canada, and the Department of Finance Canada, among others.

A series of 8 lessons emerge from the findings of these many audits. In turn, these lessons—along with some examination of examples from other jurisdictions—suggest opportunities for Canada to turn its climate commitments into lasting results.

Lesson 1: Stronger leadership and coordination are needed to drive progress toward climate commitments

The challenge

Photo: BLFootage/

Shutterstock.com

Addressing the climate change crisis requires leadership and coordination among many government actors—not only federal organizations, but also the provincial, territorial, and municipal governments.

Provincial and territorial jurisdiction and interests. Some responsibilities relevant to climate change fall under provincial and territorial jurisdiction, and climate actions are often subject to divergent regional interests. For example, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Newfoundland and Labrador produce 97% of Canadian crude oil. In addition, Alberta and British Columbia account for 97% of Canadian production of natural gas and natural gas liquids. Canada’s climate goals cannot be met without taking the oil and gas industry into account, but the debate about fossil fuel development risks both partisan and regional division. Experts that we interviewed told us that Canada needs to depolarize the climate change discussion to move the debate from whether the country should significantly reduce its emissions and toward a discussion on how emissions should be reduced.

Coordination of federal responsibilities. Many federal government organizations have an increasing number of responsibilities related to climate change, which creates complications at the national level. This risks an uncoordinated policy approach among government entities, which can hamper progress on climate action. Potentially competing mandates and responsibilities can lead to policies and decisions that can appear to be at cross‑purposes—as seen in the government’s actions on the Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion (Exhibit 5.5) and the Onshore Program of the Emissions Reduction Fund (Exhibit 5.6).

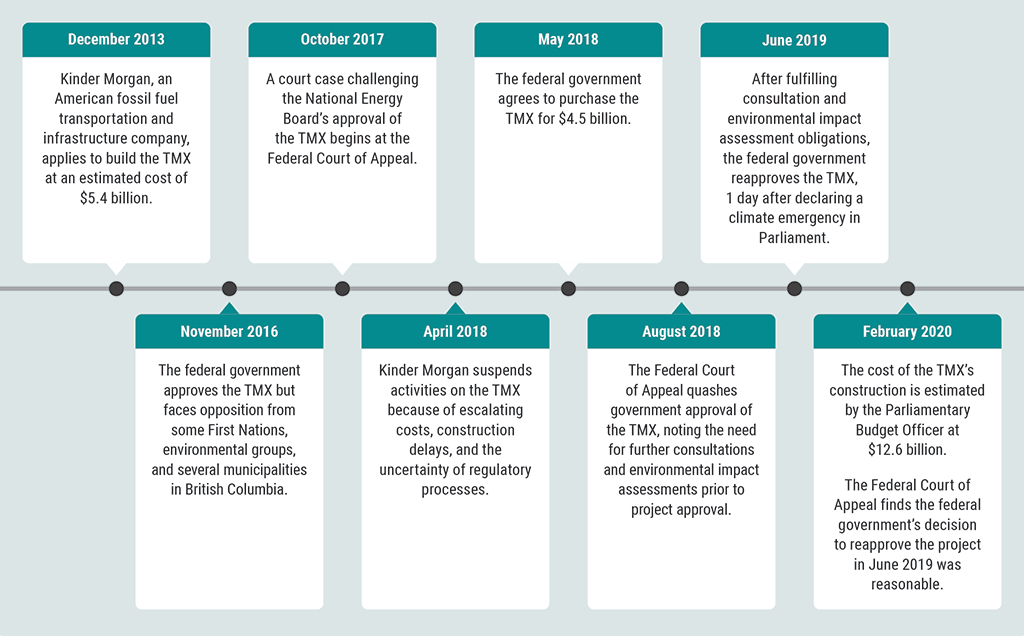

Exhibit 5.5—Investing in the Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion (TMX) is an example of policy incoherence with progress toward climate commitments

The federal government made a direct and significant investment in fossil fuel infrastructure while trying to position itself as a global leader on climate action

Exhibit 5.5—text version

This timeline shows the events and investments related to the Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion.

Overall, the Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion (TMX) is an example of policy incoherence with progress towards climate commitments. The federal government made a direct and significant investment in fossil fuel infrastructure while trying to position itself as a global leader on climate action.

In December 2013, Kinder Morgan, an American fossil fuel transportation and infrastructure company, applies to build the TMX at an estimated cost of $5.4 billion.

In November 2016, the federal government approves the TMX but faces opposition from some First Nations, environmental groups, and several municipalities in British Columbia.

In October 2017, a court case challenging the National Energy Board’s approval of the TMX begins at the Federal Court of Appeal.

In April 2018, Kinder Morgan suspends activities on the TMX because of escalating costs, construction delays, and the uncertainty of regulatory processes.

In May 2018, the federal government agrees to purchase the TMX for $4.5 billion.

In August 2018, the Federal Court of Appeal quashes government approval of the TMX, noting the need for further consultations and environmental impact assessments prior to project approval.

In June 2019, after fulfilling consultation and environmental impact assessment obligations, the federal government reapproves the TMX, 1 day after declaring a climate emergency in Parliament.

In February 2020, the cost of the TMX’s construction is estimated by the Parliamentary Budget Officer at $12.6 billion. The Federal Court of Appeal finds the federal government’s decision to reapprove the project in June 2019 was reasonable.

Exhibit 5.6—The Emissions Reduction Fund is an example of a program that aims to support the energy sector while also reducing emissions

In fall 2020, the government launched the Onshore Program of the Emissions Reduction Fund as part of Canada’s COVID‑19 Economic Response Plan. The government saw the program as a way to help the energy sector deal with lower oil prices during the COVID‑19 pandemic. The program was designed to provide financial support to struggling companies in the sector while at the same time supporting emission reduction efforts. It offered up to $675 million to help onshore (that is, land‑based) oil and gas companies maintain employment, attract investments, increase global competitiveness, and accelerate their deployment of equipment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, particularly methane emissions.

Our 2021 audit found that Natural Resources Canada did not design the Onshore Program of the Emissions Reduction Fund to ensure credible and sustainable reductions of greenhouse gas emissions in the oil and gas sector or value for the money spent.

The Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development’s audit findings on Canada’s Emissions Reduction Fund can be found on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s website.

Environment and Climate Change Canada is the lead federal department responsible for climate change. However, because the department is not a federal central agency, it cannot compel other federal organizations to undertake work related to climate change under their respective mandates.

Several of our audits on the subject of climate change have pointed to the importance of coordinating actions across federal departments and agencies and all levels of government. For example, in 2018, most provincial and territorial auditors general, together with the Auditor General of Canada, coordinated their efforts to report on climate change activities in their jurisdictions. This resulted in a collaborative summary report that was submitted to Parliament that highlighted limited coordination among and within federal, provincial, and territorial levels of government. The findings also showed limited coordination between provincial and territorial governments and their municipal governments. The summary report stated that this limited coordination led to an ad hoc response to climate change across the country. This lack of coordination also meant that important opportunities or challenges may have been overlooked and that redundant or contradictory policies may have been developed.

The Department of Finance Canada is responsible for analyzing and advising the Minister of Finance on tax measures relevant to Canada’s 2009 group of 20G20 commitment to phase out and rationalize inefficient fossil fuel subsidies. Our reports in 2017 and 2019 found that Canada’s assessments to identify inefficient tax subsidies for fossil fuels were incomplete, and the department did not clearly define what an inefficient fossil fuel subsidy was. Our reports have recommended that the Department of Finance Canada clearly define the criteria for determining whether tax subsidies for fossil fuels are inefficient and conduct an analysis of all tax measures that apply to the fossil fuel sector to support the phase‑out and rationalization of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies.

Opportunities

In our review, we identified several opportunities to address leadership challenges in the fight against climate change.

Centralizing responsibility within the federal government. In France, the Council of Ministers, which is equivalent to the Cabinet in Canada, has made the centre of government—rather than an individual department or ministry with more limited jurisdiction—responsible for climate change. We heard in our interviews with experts that recent strides have been made to put climate change closer to the centre of Canadian government policy through ministerial mandate letters, for example. However, we also heard that stronger collaboration and leadership from central agencies, such as the Privy Council Office and the Department of Finance Canada, would further drive this important agenda.

Taking provincial and territorial needs into account. Our expert interviewees identified the Pan‑Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change as a successful driver of federal–provincial coordination, as it was developed to reflect the varying needs of each province, territory, and federal organization. They also raised carbon pricing as an instance where the federal government was able to institute climate policy that could be applied at the provincial level, given the flexibility that the policy allowed provinces to have in managing their own systems, so long as they adhere to the federal benchmark (Exhibit 5.7). Experts we interviewed identified a recent Supreme Court of Canada decision that upheld the constitutionality of the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act as providing some certainty about federal power and responsibility.

Exhibit 5.7—Canada has applied minimum requirements for pricing carbon across all provinces and territories

Carbon pricing is widely recognized as one of the most efficient and effective tools for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. It spurs low‑carbon innovation and investment while encouraging businesses and households to lower their emissions. According to a World Bank Group report, 61 carbon pricing initiatives have been established or are scheduled for implementation. Together, these would apply to about 22% of global emissions. As of 2019, all Canadian provinces and territories had carbon pricing systems, some where the provinces ran the system and some where the federal system applied.

Carbon pricing is a core element of the Pan‑Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change. In October 2016, the federal government published its carbon pricing benchmark, which aims to ensure that carbon pricing covers a broad set of emission sources across Canada and increases in stringency over time. The benchmark provides flexibility for provinces and territories to design and implement their own carbon pricing systems, provided that the systems meet certain criteria. The federal government completed its review of the benchmark criteria and confirmed an increase in the carbon price by $15 per tonne each year, starting in 2023, to $170 per tonne in 2030. The federal government has also implemented a federal carbon pricing backstop, a carbon pricing system that applies only in jurisdictions that requested it or those whose carbon pricing systems do not meet the benchmark criteria. On 25 March 2021, the Supreme Court of Canada released its decision upholding the constitutionality of the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act.

In 2022, the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development will present to Parliament a performance audit that examines the federal carbon pricing system.

Depolarizing climate action discussions. Some countries, such as the United Kingdom, have successfully depolarized some aspects of the climate change discussion. The United Kingdom has an independent climate body (the Climate Change Committee), established as part of the country’s Climate Change Act, that advises the government on emission targets. It also reports to the Parliament of the United Kingdom on progress made in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and in preparing for and adapting to the effects of climate change. The legislation and the establishment of an independent advisory body have been useful in cementing consensus and holding the government accountable to ensure that climate action remains a priority in the face of competing political agendas and periodic changes in government.

In 2021, the Canadian Parliament passed the Canadian Net‑Zero Emissions Accountability Act, which enshrines in law Canada’s 2050 target of net‑zero emissions. It remains to be seen whether this legislation and the new Net‑Zero Advisory Body—an independent group of experts charged with providing advice to the Minister of Environment and Climate Change on the most efficient and effective ways to reach net‑zero emissions by 2050—will help to depolarize climate change discussions.

Considerations for parliamentarians

- How can coordination across all levels of government be strengthened?

- How will the federal government ensure that lead departments on climate change are given the resources and authority they need to provide leadership to other departments and agencies?

- How will the federal government ensure that policies within various jurisdictions are complementary rather than redundant or contradictory?

- Is there a way to depolarize aspects of the issue and ensure that the necessary elements of Canada’s climate actions remain consistent through changes in government?

Lesson 2: Canada’s economy is still dependent on emission‑intensive sectors

The challenge

Photo: Bruce Raynor/

Shutterstock.com

Canada has an abundance of energy resources, including crude oil, coal, natural gas, uranium, the highest tides in the world, and space for hydroelectric dams and wind and solar farms. The energy industry is a vital part of both the production and consumption sides of the Canadian economy. Natural Resources Canada’s Energy Fact Book 2020–2021 states that the oil and gas industry directly accounted for more than 5.3% of the country’s gross domestic product in 2019, rising to 7.8% when accounting for indirect contributions. It directly employed nearly 176,500 people and indirectly employed 422,500 people in 2019. The sector also employs 10,000 Indigenous workers. The industry is also an important contributor to international trade, accounting for 23% of Canada’s exports and 8% of its imports in 2019. However, the industry is also the largest greenhouse gas emitter in Canada (Exhibit 5.8), accounting for 26% of Canada’s total emissions in 2019.

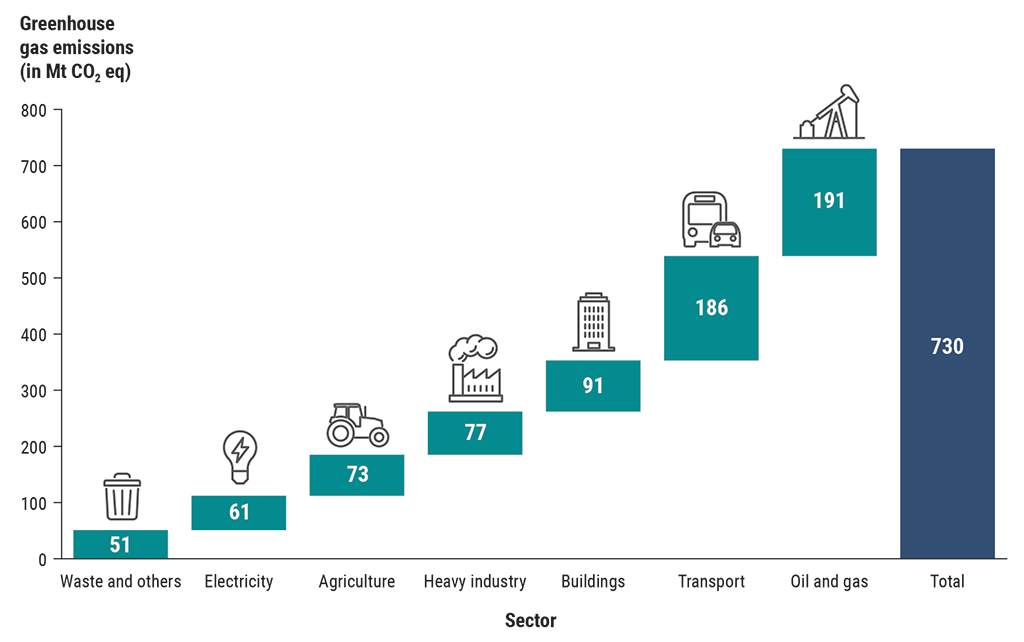

Exhibit 5.8—Oil and gas production accounts for the largest share of Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions by economic sector (2019)

Source: Based on emission data from Canada’s 2021 National Inventory Report

Exhibit 5.8—text version

This bar graph shows the different economic sectors that contributed to Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions in 2019 and the amounts these sectors emitted in megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent.

In 2019, Canada emitted 730 megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent. Of this,

- the oil and gas industry contributed 191 megatonnes, accounting for the largest share of emissions

- transportation contributed 186 megatonnes

- buildings contributed 91 megatonnes

- heavy industry contributed 77 megatonnes

- agriculture contributed 73 megatonnes

- electricity contributed 61 megatonnes

- waste and others contributed 51 megatonnes

Regional divisions. Even with substantial reductions in oil sands emissions per barrel, Canada’s growing oil and gas production remains a key barrier to meeting its climate targets. Because of these competing pressures, aggressive climate policies face not only climate skepticism, but also pushback from powerful industry interests and voter concerns about higher energy costs and economic losses caused by a transition to cleaner sources of energy. Partly because the provinces and territories have very different economies and priorities, climate change has been a polarizing regional issue in Canada.

While Canada represents about 1.6% of global emissions, it is among the top 10 largest emitters globally and one of the highest emitters per capita (Exhibit 5.9). Canada is also the world’s fourth‑largest producer and exporter of oil, with about 53% of oil produced in 2019 being exported and burned elsewhere. The Canada Energy Regulator projects that Canadian fossil fuel production will continue to grow because of oil and gas exports, even while domestic consumption declines.

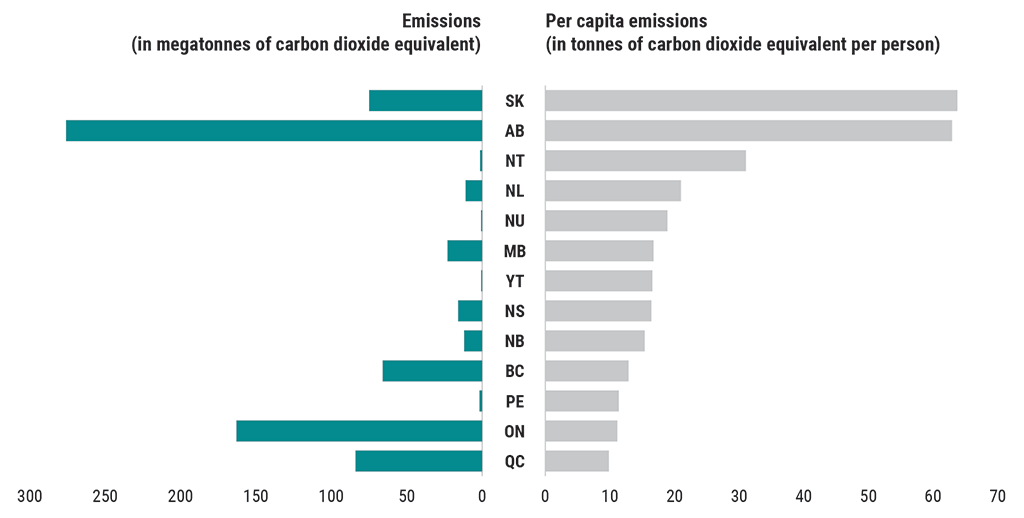

Exhibit 5.9—Total and per capita economy‑wide greenhouse gas emissions vary widely across provinces and territories (2019)

Source: Based on emission data from Canada’s 2021 National Inventory Report; per capita calculations by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada based on Canada’s 2021 National Inventory Report and 2019 population data from Statistics Canada

Exhibit 5.9—text version

This graph shows the total and per capita economy-wide greenhouse gas emissions from Canadian provinces and territories in 2019. Total emissions are listed in megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent, and per capita emissions are listed in tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent per person.

In 2019, Canada emitted 730 megatonnes. Globally, 52,400 megatonnes were emitted. The Canadian average for per capita emissions was 19.31 tonnes. The global average for per capita emissions was 4.72 tonnes.

The total and per capita emissions for the provinces and territories, in order of highest per capita emissions to lowest, are as follows:

- Saskatchewan emitted 75 megatonnes, which was 63.75 tonnes per person.

- Alberta emitted 276 megatonnes, which was 62.94 tonnes per person. It had the highest overall emissions of all of the provinces and territories.

- The Northwest Territories emitted 1.4 megatonnes, which was 30.98 tonnes per person.

- Newfoundland and Labrador emitted 11 megatonnes, which was 21.00 tonnes per person.

- Nunavut emitted 0.73 megatonnes, which was 18.90 tonnes per person.

- Manitoba emitted 23 megatonnes, which was 16.74 tonnes per person.

- Yukon emitted 0.69 megatonnes, which was 16.57 tonnes per person.

- Nova Scotia emitted 16 megatonnes, which was 16.39 tonnes per person.

- New Brunswick emitted 12 megatonnes, which was 15.37 tonnes per person.

- British Columbia emitted 66 megatonnes, which was 12.86 tonnes per person.

- Prince Edward Island emitted 1.8 megatonnes, which was 11.34 tonnes per person.

- Ontario emitted 163 megatonnes, which was 11.14 tonnes per person.

- Quebec emitted 84 megatonnes, which was 9.83 tonnes per person.

In this sense, Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions are much higher than those accounted for under the Paris Agreement because the agreement considers only emissions released within national boundaries, rather than exports, which are attributed to the consumer countries. Regardless of the accounting approach, Canada continues to play a large role in the dangerous accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

One way that countries can more fairly share the burden of reducing emissions is through border carbon adjustments—that is, by ensuring that imported goods are subject to the same emission costs as domestically produced goods are. In 2021, the Government of Canada opened a consultation to explore the possibility of partnering with other economies to introduce border carbon adjustments.

Opportunities

Governments that heavily rely on fossil fuels as sources of revenue are at risk of not being fiscally sustainable over the long term if they do not properly adapt to the phasing out of fossil fuels. Experts we interviewed told us that the Canadian government will need to adapt to decarbonization and must be aware of the shifting revenue base that will accompany the transition to a low‑emission economy. Because of shifts away from emitting activities, an economic transition will increase the risk that assets may be stranded—for example, oil and gas that will never be extracted or equipment that will not be used for its whole life cycle—and that workers may require government support to mitigate its social and economic effects. Additionally, diversifying economic activity will be essential to transitioning away from an emission‑intensive economy. As the fossil fuel tax base erodes, governments will need to identify new streams of revenue.

We identified several opportunities to address the challenges of such a transition.

Long‑term funding. Some oil‑exporting countries have successfully begun to transition their economies. For example, Norway manages its oil wealth through the Government Pension Fund Global, which it set up to shield the economy from ups and downs in oil revenue. The fund serves as a financial reserve and long‑term savings plan so that both current and future generations benefit from the country’s oil wealth. The fund also invests in renewable energy technologies and decided in 2019 to divest from unsustainable companies.

Diversifying energy production. The Commissioner’s 2017 audit on funding clean energy technologies examined clean energy technology demonstration projects in 3 funds. The audit found that the government had a rigorous and objective process in place to assess, approve, and monitor projects. However, the audit recommended that the government clearly document its project assessment and approval decisions and report publicly on the emission reductions that result from all the relevant demonstration projects it funds.

Several other countries that rely on fossil fuels have also begun to transition to a low‑carbon economy. Countries, such as the United Arab Emirates, the fifth‑largest producer in the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, have committed to diversifying their economies away from oil and natural gas and sourcing a greater proportion of their electricity from renewable sources. In Canada, steps have been taken to diversify by investing in clean technology. For example, in 2020, the Government of Canada released its hydrogen fuel strategy (Exhibit 5.10).

Exhibit 5.10—Canada aims to add hydrogen to its energy mix as part of its transition to a clean economy

Hydrogen is viewed as an option for meeting net‑zero targets by decarbonizing hard‑to‑abate sectors, such as heating and power generation, and reducing Canada’s dependence on high‑carbon fuels. Hydrogen is a carbon‑free energy carrier that emits only water and heat when burned; no greenhouse gases or other pollutants are released. However, hydrogen extraction may require large quantities of energy and, depending on the energy source, could result in emissions.

An increasing number of countries, including Japan and Germany, have released strategies and visions for a hydrogen‑fuelled economy. In Canada, the provinces of Alberta, British Columbia, Ontario, and Quebec have also made hydrogen announcements.

In December 2020, Natural Resources Canada released the Hydrogen Strategy for Canada. The policy document demonstrates what a hydrogen‑fuelled economy could look like in Canada where clean hydrogen can deliver up to 30% of Canada’s end‑use energy by 2050, abating up to 190 megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent. This would be accomplished through deployment in transportation, heating, and industrial applications. The strategy also views hydrogen as an opportunity to expand Canada’s export market that could reach $50 billion by 2050.

In 2022, the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development will present to Parliament a performance audit that examines the role of hydrogen in reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Shielding workers and communities. A key consideration of transitioning an economy away from fossil fuels is the need to shield communities and workers who might be negatively affected by the climate policy. Many countries, including Canada, have begun to address vulnerable workers and communities through “just transition” initiatives (Exhibit 5.11). The European Union established the Just Transition Mechanism to direct about $183 billion to the fossil‑fuel‑producing and carbon‑intensive regions most affected by the energy transition from 2021 to 2027. Germany’s Energiewende (energy transition) is a mission‑oriented program aimed at creating a low‑carbon energy system while phasing out nuclear power by 2022 and coal‑fired power by 2038. Germany’s coal phase‑out includes compensation claims by coal plant operators and paves the way for economic support programs worth €40 billion (CanadianCAN$59 billion) in coal regions.

Exhibit 5.11—The government supports a just transition for coal workers

In 2016, the Government of Canada committed to phasing out traditional coal‑fired electricity by 2030 to help meet Canada’s emission reduction targets. However, the coal phase‑out could also lead to job losses, income insecurity, and social effects. It will eventually affect nearly 50 communities and roughly 3,900 coal workers, mostly in Alberta, but also in Saskatchewan, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia. The status of coal mines and coal plants varies across these provinces; some are already closed and others are scheduled to close by 2030.

The Pan‑Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change acknowledges the importance of supporting coal workers and communities in a just and fair transition to a low‑carbon economy. To identify possible solutions to support a just and fair transition, the government launched its Task Force on Just Transition for Canadian Coal Power Workers and Communities in 2018. Its key recommendations included

- prioritizing infrastructure projects in affected communities

- funding locally driven transition centres in affected communities

- dedicating funds for economic redevelopment and skills retraining

The government began to allocate funds from a $35‑million Canada Coal Transition Initiative in 2018 and is now disbursing $150 million from a similar fund for infrastructure projects and economic diversification. The Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency and Prairies Economic Development Canada (established in 2021 when Western Economic Diversification Canada divided operations between Pacific Economic Development Canada and Prairies Economic Development Canada) are administering these funds to affected communities. Natural Resources Canada and Employment and Social Development Canada are working toward federal support for a just transition toward a low‑carbon economy.

In 2022, the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development will present to Parliament a performance audit that examines Canada’s just transition for coal workers.

National energy strategy. A robust economic transition at the necessary scale and pace will require long‑term planning coordinated by the federal government with strong involvement from the provinces and territories. A national energy strategy could help to unify Canada’s diverse energy interests and map a path forward for governments and industry. The strategy should align with climate targets and the varying energy needs across all regions. It should also incorporate elements needed to shield workers and communities from the effects of an industrial transition.

The United Kingdom’s Energy White Paper is the country’s national 10‑point plan that sets out how the country will clean up its energy system to reach net‑zero emissions by 2050. The strategy’s focus areas include reducing energy consumption in buildings, industry, and transportation. It also includes commitments in the areas of green finance and innovation. The strategy focuses on wind, nuclear, and hydrogen energy and carbon capture, use, and storage for transitioning to a low‑carbon economy. In addition, the plan lays out ambitious objectives for the transportation industry, such as accelerating the transition to green ships and planes and ending the sale of new petrol and diesel cars and vans by 2030.

Considerations for parliamentarians

- How much financial support does Canada provide to the oil and gas industry? Could this support be reallocated to workers?

- How can Canada deliver on its promise to reduce fossil fuel subsidies that undermine the achievement of climate change actions?

- What role could a national energy strategy play in diversifying Canada’s economic interests and mitigating risks to the energy supply across Canada?

- How can the federal government identify and assist communities and workers most affected by the transition to a low‑carbon economy?

Lesson 3: Adaptation must be prioritized to protect against the worst effects of climate change

The challenge

Photo: FDR Stock/

Shutterstock.com

Climate change is increasing the frequency and magnitude of extreme weather events, such as droughts, floods, heat waves, wildfires, and storms, and causing more gradual changes, such as melting permafrost and rising sea levels (Exhibit 5.12). The associated costs from weather‑related disasters in Canada have risen over the past decade and are now equivalent to 5% to 6% of the annual gross domestic product growth. The costs per disaster have increased drastically as well, jumping 1,250% since the 1970s. For example, the devastating 2016 wildfires in and around Fort McMurray, Alberta, necessitated the evacuation of over 80,000 people and incurred $11 billion in economic losses. Wildfire smoke is thought to cause hundreds to thousands of premature deaths each year in Canada and cause health effects that cost the Canadian economy billions of dollars annually. Loss of property is another concern because an estimated 10% of Canadian households are at very high risk of flooding.

Exhibit 5.12—Climate‑related infrastructure failures can pose real risks to Canadians

Climate change is already affecting Canadian infrastructure, particularly in vulnerable northern and coastal regions. Climate‑related infrastructure failures threaten health and safety and can interrupt essential services, disrupt economic activity, and incur high costs for recovery and replacement. To better adapt to climate change, the government has committed billions to fund infrastructure projects that incorporate climate considerations into infrastructure planning. Proper design and rehabilitation will help Canadians withstand climate effects, protect the health and safety of Canadians, and generate long‑term cost savings.

Infrastructure Canada launched a Climate Lens tool in 2018 to help promote the consideration of climate risks and greenhouse gas emissions in the design and planning of new infrastructure. The Climate Lens tool includes a greenhouse gas mitigation assessment, which provides an estimate of the anticipated emissions impact of federally funded infrastructure projects funded through the Investing in Canada Infrastructure Program, the Disaster Mitigation and Adaptation Fund, and the Smart Cities Challenge. It also includes a climate change resilience assessment, which employs a risk management approach to the projected impacts of future climate change.

An updated Climate Lens approach, which directly integrates climate considerations, is starting with the 5‑year, $1.5‑billion Green and Inclusive Community Buildings program. This program supports green and accessible construction, retrofits, repairs, and upgrades of public community buildings that serve high‑need or underserved communities.

In 2022, the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development will present to Parliament a performance audit that examines the evolution and application of Infrastructure Canada’s Climate Lens approach.

Because of the accumulation of long‑lasting greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, the effects of climate change cannot practically be reversed, even if emissions were to drop sharply. Nevertheless, some vulnerabilities related to climate change can be reduced through measures to adapt to the effects. The Commissioner’s climate audits have repeatedly found deficiencies in the federal government’s climate adaptation plans. Reports in 2010 and 2017 found that concrete actions had not been taken to adapt to the effects of a changing climate. In 2018, a collaborative summary report with most of Canada’s provincial auditors general identified similar deficiencies in climate adaptation efforts across Canada. The summary report’s findings highlighted that most Canadian governments had not assessed the risks they faced and the actions they should take to adapt to a changing climate.

Opportunities

The effective implementation of adaptation measures depends on policies and cooperation at all levels of government and can be improved through integrated responses that link mitigation and adaptation with other societal objectives. For example, nature‑based climate solutions that sequester carbon or help prevent floods can simultaneously assist in mitigation and adaptation and address the related crisis of biodiversity loss.

Federal action. Through the Pan‑Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change, the federal government committed to several actions to build climate resilience across Canada. This included

- translating scientific information and traditional knowledge into action—for example, by providing authoritative climate information and building regional adaptation capacity and expertise

- investing in infrastructure and developing climate‑resilient codes and standards

- protecting and improving human health and well‑being by addressing climate‑related health risks and supporting health in Indigenous communities and in particularly vulnerable regions

- reducing climate‑related hazards and disaster risks by investing in infrastructure that minimizes disaster risk, advancing flood‑protection efforts, improving management practices in the forestry sector, and supporting adaptation efforts in Indigenous communities

Through our audits, the Commissioner has recommended that the government develop a federal adaptation action plan and common guidance for assessing climate risks and build government‑wide awareness of climate change risks and opportunities to inform adaptation planning. The 2020 A Healthy Environment and a Healthy Economy plan commits Canada to developing its first national adaptation strategy. This strategy would establish a shared vision for climate resilience in Canada, identify key priorities for increased collaboration, and establish a framework for measuring progress at the national level.

Subnational actions. The need for adaptation will vary across Canada’s provinces and territories. Municipal governments, Indigenous communities, businesses and industry groups, and local non‑government actors are closest to the problem and well positioned to offer context‑specific, adaptive solutions. The federal, provincial, and territorial governments can draw on this local knowledge and provide forums for planning and implementation to enable the sharing of experience and expertise.

The 2018 collaborative summary report on climate change undertaken by most auditor general offices across Canada found that among the provinces and territories, only Nova Scotia had undertaken a detailed, government‑wide assessment of climate risks. In most other provinces and territories, risk assessments had been completed for individual communities, sectors, or government departments. Nova Scotia was also the first province to require local climate action plans when it mandated the creation of municipal climate change action plans by 2014.

Action is also occurring at the municipal level. For example, in 2012, Vancouver adopted a Climate Change Adaptation Strategy to identify and prioritize vulnerabilities and to guide the development of policies and programs to build resilience. Indigenous communities in Canada are also taking action to prepare for the effects of climate change. For example, the Tsleil‑Waututh Nation in British Columbia has initiated a Community Climate Change Resilience Planning project, which includes a hazard and vulnerability assessment and the development and implementation of a 10‑year climate action plan.

Implementing adaptation measures early. Compared with the high costs of cleaning up disasters after the fact, investing early in adaptation measures avoids losses and generates significant economic, social, and environmental benefits, such as through reducing risk, increasing productivity, and driving innovation. A 2019 report found that a global investment of $1.8 trillion in early warning systems, climate‑resilient infrastructure, improved dryland agriculture crop production methods, global mangrove protection, and more resilient water resources from 2020 to 2030 could generate $7.1 trillion in total net benefits.

Considerations for parliamentarians

- How will the federal government ensure that all sectors of society are involved in developing and implementing adaptation strategies?

- As the federal government dedicates resources to adaptation, how can it ensure that the most pressing risks are prioritized?

- How can the federal government catalyze nature‑based solutions as a route to adaptation?

- How will the federal government ensure that funding is available for adaptation projects and initiatives?

- How can the federal government better integrate local and community‑level insights into federal adaptive planning and action?

Lesson 4: Canada risks falling behind other countries on investing in a climate‑resilient future

The challenge

Photo: CHOTTHANIN THITIAKARAKIAT/

Shutterstock.com

The risks that climate change pose to the economy also have deep effects on the financial system. For example, damage from flooding, hurricanes, droughts, and wildfires raises costs for home and business owners and consequently for insurance companies. In addition, chronic effects, such as melting permafrost and rising sea levels, will have long‑term economic effects. Costs also rise because of the need to adapt to the physical effects of climate change and to shift to a lower‑carbon global economy. Financial decisions in Canada must take climate change into account if risks to Canadians are to be mitigated. However, we heard through our interviews with experts that Canada has not been a key player in the international discussion on sustainable finance. Canada risks being left behind while countries with very different economies set the agenda.

Mitigating risks to the financial system. Investors and authorities can better mitigate the risks that climate change poses to financial systems when they know what the exposures are and how these can be managed. In 2015, the Financial Stability Board, an international body, established the Task Force on Climate‑related Financial Disclosures to develop voluntary and consistent climate‑related financial risk disclosures for companies to use when providing information to investors, lenders, insurers, and other stakeholders. The task force, which consists of 32 members from across the group of 20G20, recommends that firms publish climate‑related financial information (Exhibit 5.13). However, this practice is not universal. Few firms disclose the financial impact of climate change on their assets, and there are inconsistencies in how climate‑related risks are reported across industries and regions.

Exhibit 5.13—Standards for climate‑related financial disclosures are still emerging in Canada and globally

A transition to a low‑carbon economy will require significant investment to decarbonize certain industries and develop others.

Climate change disclosures help investors make informed decisions to redirect their investment capacity toward industries and market players that are aligned with the transition to a low‑carbon economy. Such disclosures provide information on the impact that climate change has on a project, a company, or an investment fund’s returns, as well as the impact these entities have on the climate. These disclosures describe and quantify how the entities identify, assess, measure, and manage climate‑related risks and opportunities.

Investors and other users of financial reports cite the inconsistencies in disclosure practices and non‑comparable reporting as major obstacles to incorporating climate‑related risks and opportunities as considerations in their investment, lending, and insurance‑underwriting decisions. Evidence suggests that the lack of consistent information also hinders investors and others from considering climate‑related issues in their asset valuation and allocation processes.

In 2015, the Financial Stability Board was asked by the G20 finance ministers and central bank governors to look into how the financial sector could take climate matters into account. The board identified the lack of available information as a key issue and created the Task Force on Climate‑related Financial Disclosures to address it. In 2017, the task force released its recommendations, which promote transparency as a contributor to better climate risk management.

In its September 2020 consultation on sustainability reporting, the International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation stated that “a process of ‘bottom up’ cooperation among regional initiatives or existing standard‑setters alone would not be sufficient to realise the goal of establishing even a basic set of standards. To develop such standards, a global initiative would be needed, and it would be vital for that global initiative to cooperate with regional initiatives to achieve global consistency and comparability.” In 2021, the foundation proposed a new International Sustainability Standards Board, which will work on developing a new set of sustainability standards that are based on existing frameworks, notably the task force’s recommendations.

Current securities legislation in Canada requires the disclosure of certain climate‑related information in an issuer’s regulatory filings only if such information is considered material, as with any other type of risk. However, there is no standard framework to report such disclosures in a comparable and transparent framework.

In 2022, the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development will present to Parliament a study that examines climate‑related financial disclosures.

International climate finance. Developed countries continue to consume a disproportionate share of the world’s natural resources. Particularly with fossil fuels, this has contributed to the accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. While developed countries have reaped economic rewards from this, developing countries—especially those vulnerable to sea‑level rise, desertification, and flooding—have disproportionately felt many of the negative effects. Further, climate change is expected to increase poverty because of its effects on agriculture, water resources, and health. The developing world faces many additional vulnerabilities relative to developed countries. For example, they tend to be warmer than developed regions and suffer from high rainfall variability. They also depend heavily on agriculture, the most climate‑sensitive of all economic sectors, and suffer from inadequate health care and low‑quality public services. Their low incomes combined with these vulnerabilities make their adaptation to climate change particularly difficult.

Adapting to the effects of climate change and enabling a global transition to low‑emission energy sources require developed countries to provide more financial support to developing countries, particularly vulnerable ones. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the Kyoto Protocol, and the Paris Agreement all call for such financial assistance, recognizing differing capabilities in responding to the climate challenge. Developed countries have committed to jointly mobilizing AmericanUS$100 billion per year by 2020 from a wide variety of sources—public and private, bilateral and multilateral, and alternative sources. Canada has committed to providing $2.65 billion over 5 years (2016–21) in climate finance and has committed to increasing this figure to $5.3 billion over the next 5‑year period. However, the Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development reports that actual financing has fallen short of the US$100 billion goal, having reached US$79.6 billion in 2019.

Opportunities

In our review, we identified several opportunities in the field of climate finance.

Disclosing climate‑related risks. In the 2021 budget, the Government of Canada announced that it would be making climate disclosures part of regular disclosure practices for a broad spectrum of the Canadian economy. This includes requiring Canada’s large Crown corporations (those with over $1 billion in assets) to report on their climate‑related financial risks, starting in 2022. Smaller Crown corporations will be expected to start reporting on their climate‑related financial risks in 2024. As well, under the new Canadian Net‑Zero Emissions Accountability Act, the Minister of Finance will report annually on government measures to manage climate‑related financial risks and opportunities.

In 2018, the European Commission released its action plan on financing sustainable growth to establish a regulatory framework that supports the goals of the Paris Agreement. This includes mandating climate risk disclosures for investors and improving the methodologies and practices of corporate risk disclosure.

Incorporating sustainable development into finance. Canada has made progress on sustainable finance in recent years. In April 2018, the Minister of Environment and Climate Change and the Minister of Finance appointed an Expert Panel on Sustainable Finance. The panel produced a report, Mobilizing Finance for Sustainable Growth, which presented 15 recommendations, including

- establishing a standing Canadian Sustainable Finance Action Council, with a cross‑departmental secretariat, to advise and assist the federal government on implementing the panel’s recommendations

- embedding climate‑related risk into the monitoring, regulation, and supervision of Canada’s financial system

- promoting sustainable investment as “business as usual” in Canada’s asset management community

In 2019, the Bank of Canada joined the Network for Greening the Financial System, a worldwide forum of central banks and financial system supervisors that defines and promotes best practices in climate risk management for the financial sector and conducts analytical work on green finance.

Support for developing countries. In 2014, the Commissioner examined international climate finance through Canada’s fast‑track financing initiative. Environment and Climate Change Canada (then named Environment Canada) had developed an interactive website to provide details on the projects funded by Canada’s share of the initiative. However, we found that the department could improve the consistency and value of its public reports by including information about the status of project spending and the flows of funds back to Canada. It could also work with its federal and international partners to better predict and assess results, including greenhouse gas emission reductions. This collaboration and coordination are of continued importance, in view of the global efforts to reduce emissions and adapt to a changing climate.

Considerations for parliamentarians

- How should the federal government incorporate climate disclosures into the regular risk‑disclosure practices of federal organizations and Crown corporations?

- How should the federal government mandate firms that are seeking investment capital to disclose their climate risks?

- How can the federal government better contribute to international discussions on climate finance?

- How can the federal government mandate investments that are managed across its operations to decarbonize their investment portfolios?

Lesson 5: Increasing public awareness of the climate challenge is a key lever for progress

The challenge

Photo: HTWE/

Shutterstock.com

Scientists and the Government of Canada recognize climate change as a serious global threat. While Canadians’ awareness of the climate crisis has increased in recent years, a 2020 poll showed that just three quarters of Canadians agreed that human activities contribute to climate change. It also showed that 60% agreed that the government would be failing all citizens if it did not act to address climate change, which trails the global average of 68%. As public support and collective action are important for policy and behavioural change, insufficient public awareness of climate change can hinder Canada’s progress on climate action.

Opportunities

In our review, we identified several opportunities to address the challenges of climate awareness.

Sharing policy objectives. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Paris Agreement call on governments to educate, empower, and engage all stakeholders and major groups on policies and actions related to climate change. An informed public is better equipped to assess proposed government policies on climate change and make decisions about the goods they consume. Building awareness of some proposed policies, such as carbon pricing, can help build support and dispel misinformation about costs to consumers.

The government has taken some steps toward building public awareness of climate change. For example, one of the objectives stated in the national assessment, Canada in a Changing Climate: Advancing our Knowledge for Action, issued by Natural Resources Canada in 2019, is to “increase awareness of the relevance of climate change to Canadians and the need for timely action.” Earlier this year, the government announced an investment of $3 million to educate 300,000 children on how they can help Canada meet its net‑zero emission target by 2050. However, building awareness and seeing the results of associated behavioural shifts takes time.

Enhanced transparency. The government has an opportunity to build awareness through increased transparency about its progress toward meeting climate commitments and the policy measures it plans to take. Transparency can help to hold the government to account and can also help to build trust with citizens. The Commissioner has examined transparency in many climate‑related audits. For example, in 2009, the Commissioner found a lack of transparency in climate change modelling and reporting. In 2014, the Commissioner recommended that climate change reports could be improved by describing key assumptions, communicating uncertainty associated with estimates, and describing emissions from Canada’s forests more consistently and appropriately. Further, in 2019, the Commissioner found that statements on progress against Canada’s greenhouse gas emission targets were not fairly presented.

Climate change in public discourse. Concerted action taken by the government to build awareness and counter misinformation will help create a more informed public discourse. Building awareness of the facts of climate change and the basis for climate policies helps to reduce the amount of political polarization that can stem from the spread of misinformation. It can also lay the groundwork for the individual behavioural changes that Canadians can make to fight climate change.

Governments can benefit from a communications strategy that incorporates clear objectives to ensure effectiveness and equity. The strategy can involve partners and stakeholders to ensure coherency while accommodating regional diversity. Governments can use social media platforms in addition to traditional communication channels to reach a broader audience of Canadians. Partnering with Indigenous communities, trusted organizations, businesses, and community leaders can help governments build awareness of the climate crisis and enhance trust and credibility in the policy measures being implemented to combat the climate crisis.

Considerations for parliamentarians

- How can the federal government strengthen Canadians’ awareness of the climate crisis and the measures to address it?

- Where are the knowledge gaps and sources of misinformation on the topic and how can they be addressed?

- What are the best ways to relay climate‑related messaging so that it resonates with Canadians?

Lesson 6: Climate targets have not been backed by strong plans or actions

The challenge

Photo: Dmitry Demidovich/

Shutterstock.com

Achieving the Paris Agreement goals to limit global temperature rise requires an urgent, transformative response. While setting ambitious emission reduction targets is necessary, countries must also ensure that they are implementing policies and actions toward their goals.

Targets without follow‑up. Since 1990, Canada has repeatedly made domestic and international commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, to adapt to the effects of climate change, and to support clean energy technology. However, as documented in the Commissioner’s past climate reports, Canada has consistently failed to meet its climate targets, including the specific emission targets set in response to the Kyoto Protocol.

In 2017, the Commissioner noted that previous plans had failed to produce concrete results and that the government had to start the hard work of turning the Pan‑Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change into tangible and measurable actions. Canada’s initial target under the Paris Agreement was to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 30% below 2005 levels by 2030, and under the Copenhagen Accord, it committed to reducing emissions by 17% below its 2005 levels by 2020. Despite these commitments, total national emissions have declined by only 1.1% from 2005 to 2019. The timely implementation of policies and actions outlined in the plans to meet targets has been sorely lacking.

Opportunities

In 2017, the Commissioner recommended that the government develop an integrated approach to measure, monitor, and report publicly on the federal, provincial, and territorial contributions toward meeting Canada’s 2030 target for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. In 2021, the Government of Canada announced its new target of a 40% to 45% reduction below 2005 levels by 2030, accompanied by a new target of net‑zero emissions by 2050. These new targets signal heightened ambitions, but the government also needs to ensure that the targets are actually achieved through its plans and actions. New policy and legislation present some opportunities to address the challenge.

Achieving the new targets. Taken together, full implementation of the actions and measures outlined in the Pan‑Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change, A Healthy Environment and a Healthy Economy, and Budget 2021 are expected to yield reductions of 36% below 2005 levels by 2030. While implementation of Canada’s current climate plans may fulfill Canada’s initial 2030 target of a 30% reduction below 2005 levels, Canada now has a new, more ambitious goal of 40% to 45%. Therefore, the government will have to revisit the plans, policies, and actions needed to achieve the new targets. Looking further ahead, Canada also needs to align its goal of having net‑zero emissions by 2050 with its new 2030 target and establish incremental, 5‑year milestones leading up to 2050. Regardless of when Canada makes a new plan to match its new targets, the emphasis this time (unlike with its previous plans) should be on meeting the targets and not just making plans. Sound plans are essential, but it is the outcome that really matters. Some countries (for example, Costa Rica and Kenya) have shown leadership in ensuring that their plans and related policies are consistent with their Paris Agreement targets.

Recent legislative change. Canada’s new 2030 target provides a window of opportunity for the government to better align its policies and actions with its objectives. In 2021, Parliament passed the Canadian Net‑Zero Emissions Accountability Act, which enshrines in law Canada’s 2050 target of net‑zero emissions and requires a series of national greenhouse gas emission targets at 5‑year milestones starting in 2030. The act also requires the Minister of Environment and Climate Change to establish an emission reduction plan for 2030. Pursuant to the act, the emission reduction plan for 2030 must include an interim greenhouse gas emission objective for 2026. Each emission target under the act is required to be more ambitious than the previous one. Additionally, the Commissioner’s mandate has been expanded by the Canadian Net‑Zero Emissions Accountability Act. This act requires the Commissioner to examine and report on the government’s implementation of measures aimed at mitigating climate change. This reporting may include recommendations on improving the effectiveness of the implementation of these measures.

Considerations for parliamentarians

- How can the federal government tangibly demonstrate accountability and transparency in its results?

- How will Parliament ensure that the federal government is held to account for action on climate change?

- What steps will the federal government take to ensure that Canada’s climate plan, policies, and actions align with its new targets?

- How can the federal government (advised by the Net‑Zero Advisory Body) advance the implementation of the Canadian Net‑Zero Emissions Accountability Act and its incremental 5‑year milestones?

Lesson 7: Enhanced collaboration among all actors is needed to find climate solutions

The challenge

Photo: Rawpixel.com/

Shutterstock.com

Governments cannot meet climate objectives alone. Without broad, collaborative action, Canada’s emission reduction goals are out of reach. At the 21st Conference of the Parties in Paris in 2015, participants agreed to mobilize action from non‑government partners, including civil society, the private sector, financial institutions, local communities, and Indigenous peoples.

Further, ensuring diverse interests and competing interests are represented and reflected in climate solutions is crucial to ensuring a robust, inclusive response to the climate crisis. Yet much of the potential for collaboration between government and non‑government partners remains untapped.

Opportunities

We identified international and domestic examples of how to include Indigenous communities and stakeholders to the table.

International examples. Globally, non‑government actors are building momentum for climate action, and governments are finding ways to better cooperate with these actors. For example, the Climate and Clean Air Coalition is a voluntary partnership of 73 state partners (including Canada), 19 intergovernmental organizations, and 59 non‑governmental organizations that aims to reduce powerful, short‑lived climate pollutants, such as methane.

Numerous actors in the private sector have been joining forces to lead climate change action. For example, the We Mean Business Coalition now includes more than 2,000 companies committed to climate action; these companies represent $24.8 trillion in market capitalization worldwide. Canada can look to these private sector leaders as examples of how to leverage and strengthen collaboration.

Domestic examples. In addition to delivering emission reductions, non‑government actors can put policies into action and, in turn, spur more climate ambition. Many Canadian actors—including Indigenous communities, the private sector, and non‑profit organizations—are already demonstrating their leadership:

- The First Nations Major Projects Coalition and the First Nations Climate Initiative, which represent more than 70 First Nations across Canada, aim to lead and own economic development projects that contribute to national and global strategies to achieve net‑zero emissions by 2050 while supporting economic self‑determination for their communities.

- In July 2020, the International Institute for Sustainable Development published 7 principles for enabling Canada to meet its commitment to having net‑zero emissions by 2050 while fostering economic resilience and creating quality jobs. Several leading Canadian environmental non‑governmental organizations have signed on to these principles.

- Canada’s new Climate Action and Awareness Fund, announced in 2020, will invest $206 million over 5 years to support Canadian‑led projects that contribute to Canada’s emission reductions. The fund is designed to support youth climate awareness and community‑based climate action and advance climate science and technology.

- Canadian companies are among the more than 160 private sector partners that are advocating for broad adoption of carbon pricing through the Carbon Pricing Leadership Coalition.

- Canadian oil and gas companies are exploring new technologies, such as the use of solvents in oil sands production, to reduce both costs and emissions.

- Fifteen Canadian universities have signed the Investing to Address Climate Change charter, which commits them to incorporating environmental, social, and governance factors into how they manage their long‑term investment portfolios, measuring the carbon emissions of their investments regularly, and setting targets for reducing their investment portfolios’ carbon emissions in order to accelerate the transition to a low‑carbon economy.

Considerations for parliamentarians

- What steps can the federal government take to better collaborate with all sectors of society to meet Canada’s climate targets and develop mitigation and adaptation strategies?

- How can Parliament facilitate more effective ways for non‑government actors to hold the federal government to account for its climate objectives?

- How can the federal government support industry, trade, and professional associations to help them equip their members for the effects, risks, and opportunities of climate change and the transition to the low‑carbon economy?

- How can the federal government help sectors create transition plans to accelerate the transition to a low‑carbon economy?

Lesson 8: Climate change is an intergenerational crisis with a rapidly closing window for action

The challenge

Photo: HQuality/

Shutterstock.com

Governments often struggle with long‑term problems. Governments—and those who wish to form a government—often plan around the next election, rather than around longer‑term challenges. Internal government planning cycles also favour short‑term thinking at the expense of long‑term planning. Past inaction on climate change has created the present crisis. Meanwhile, continued inaction unfairly burdens future generations, who will experience even greater effects from the long‑lasting greenhouse gases that have already been emitted.

Opportunities

We identified examples of how other countries are addressing the intergenerational aspect of fighting climate change. Hungary and Wales have instituted government bodies to protect future generations by overcoming short‑term political interests. Courts, particularly in the countries of the European Union, notably in the Netherlands, France, and Germany, have recently made landmark decisions that force governments to take stronger climate action.

The Parliament of Canada, through the Canadian Net‑Zero Emissions Accountability Act and the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act, has integrated climate action into legislation in recent years. However, Parliament—as a custodian of our democratic institutions and of our collective future—must intensify efforts in the fight against climate change to make up for decades of missed opportunities and missteps.

Considerations for parliamentarians

- How can the federal government be held to account for solving long‑term issues such as climate change?

- How can the federal government ensure that the interests of future generations are included in present decisions?

- How can the principle of intergenerational equity be incorporated into institutional decision making?

- How can the federal government better involve youth in climate policy?

Conclusion

The need for action on climate change has never been more pressing. Global momentum on climate change action is growing, and Canada has set strong emission targets by committing to a reduction of 40% to 45% below 2005 levels by 2030 and to reaching net‑zero emissions by 2050. However, as previous reports by the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development and the Auditor General of Canada demonstrate, Canada has consistently failed to meet its emission reduction targets. Over the past 30 years, Canada has gone from being a climate leader to falling behind other developed countries despite recent efforts.

Canada can learn from 3 decades of results by

- strengthening leadership and coordination at the national and subnational levels

- transitioning the economy and vulnerable communities away from emission‑intensive sectors

- prioritizing adaptation to protect against the worst effects of climate change

- prioritizing finance and investment to support climate objectives both domestically and internationally

- increasing climate awareness among Canadians to support the policy choices needed to transition to a low‑carbon future

- backing climate targets with strong plans and effective implementation

- inviting all players to the decision‑making table, including Indigenous communities, the financial sector, businesses, industry, professional associations, academia, and non‑governmental organizations

- acting now to protect future generations against the worst effects of climate change

With strong, concerted action from parliamentarians and Canadians, Canada can move past its poor track record on climate change and meet its international climate obligations. Building on momentum around the globe and at home, including recent climate legislation, stronger plans, and increased funding, Canada can achieve a cleaner, net‑zero‑emission future for generations to come.