2022 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of CanadaReport 5—Chronic Homelessness

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings and Recommendations

- Addressing chronic homelessness

- Infrastructure Canada and Employment and Social Development Canada did not know whether their efforts to prevent and reduce chronic homelessness were leading to improved outcomes

- Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation did not know who was benefiting from its initiatives

- Minimal federal accountability for reaching the National Housing Strategy target to reduce chronic homelessness by 50% by the 2027–28 fiscal year

- Addressing chronic homelessness

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- Recommendations and Responses

- Exhibits:

- 5.1—Definitions of homelessness and chronic homelessness

- 5.2—The housing continuum

- 5.3—Breakdown of $78.5 billion in planned spending under the National Housing Strategy

- 5.4—Uncertain results for key indicators used for measuring progress toward preventing and reducing homelessness

- 5.5—Targets for the National Housing Strategy’s initiatives only measured outputs

- 5.6—Rental housing units considered affordable and approved under the National Housing Co‑Investment Fund were often unaffordable for low‑income households across Canada in 2020

Introduction

Background

5.1 Access to housing is a challenge for many Canadians, particularly for vulnerable people, including those who are at risk of homelessness or those experiencing chronic homelessness (Exhibit 5.1). People experiencing chronic homelessness often have complex housing and service needs. There are many reasons why a person can experience chronic homelessness, including poverty, housing affordability and supply, the availability of supports and services for those at risk of homelessness, and personal circumstances such as job loss.

Exhibit 5.1—Definitions of homelessness and chronic homelessness

Homelessness is the state of individuals who lack stable, permanent, appropriate housing or who lack the immediate prospect, means, and ability to acquire it. People who are experiencing homelessness can include those who are unsheltered, are in emergency shelters, are in temporary accommodations, and are at risk of homelessness. Homelessness is a fluid experience, where a person’s housing situation and options may change frequently.

Chronic homelessness is the state of individuals who are experiencing homelessness and who meet at least 1 of the following criteria:

- a total of at least 6 months (180 days) of homelessness over the past year

- recurrent experiences of homelessness over the past 3 years, with a cumulative duration of at least 18 months

And who have spent time staying in any of the following contexts:

- unsheltered locations without consent or contract, or places not intended for permanent human habitation

- emergency shelters

- with others temporarily or in short-term rentals, without the guarantee of continued residency or the prospect of permanent housing

Sources: Adapted from Reaching Home: Canada’s Homelessness Strategy Directives, Infrastructure Canada, and Canadian Definition of Homelessness, Canadian Observatory on Homelessness

5.2 There is a housing continuum—the housing that people in Canada may move through, ranging from being without a home to having a home of one’s own (Exhibit 5.2). Access to housing along the housing continuum affects many aspects of a person’s quality of life, such as health and educational outcomes, and ability to be part of the labour force. Some responses to homelessness, such as emergency shelters, are designed to be short-term, temporary supports until other housing types become viable options.

Exhibit 5.2—The housing continuum

Source: Adapted from About Affordable Housing in Canada, Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, 2018

Exhibit 5.2—text version

The housing continuum has the following stages:

- Homelessness

- Emergency shelter

- Transitional housing

- Supportive housing

- Community housing

- Affordable housing

- Market housing

5.3 Individuals whose dwellings are deemed inadequate, unsuitable, or unaffordable and who are not able to afford alternative housing in their communities are considered to be in core housing need. The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation defines adequate, suitable, and affordable housing as follows:

- Adequate housing—Housing that is not in need of major repairs, such as repairs to defective plumbing or electrical wiring, or structural repairs to walls, floors, or ceilings.

- Suitable housing—Housing that has enough bedrooms for the size and make‑up of the resident household. This is according to National Occupancy Standard requirements.

- Affordable housing—Housing that costs less than 30% of before‑tax household income.

5.4 On 11 March 2020, the World Health Organization declared a pandemic because of the rapid spread of the virus that causes the coronavirus disease (COVID‑19)Definition 1. The COVID‑19 pandemic created additional challenges for people experiencing or at risk of homelessness, such as limited access to public spaces that were subsequently closed. Governments and service providers had to adjust the way they provided housing and homelessness support to Canadians. The pandemic also created additional costs and operational pressures for shelters and other service providers, such as those related to accommodating physical distancing and personal protective equipment. Furthermore, the pandemic affected the cost and availability of building supplies for housing construction and repairs.

5.5 Many partners must work together in Canada to address homelessness and chronic homelessness. This includes federal, provincial, and municipal governments, Indigenous governments and organizations, and other partners such as not‑for‑profit organizations.

5.6 Launched in 2017, the National Housing Strategy is a 10‑year, $78.5 billion federal strategy intended to improve housing outcomes and affordability for Canadians in need, including reducing chronic homelessness by 50% by the 2027–28 fiscal year. The strategy was informed by national consultations held in 2016 with partners and stakeholders.

5.7 The National Housing Strategy aims to meet the housing needs and improve the housing outcomes of the most vulnerable Canadians, including the following 11 groups:

- survivors fleeing domestic violence (especially women and children)

- seniors

- people with disabilities

- people dealing with mental health and addiction issues

- racialized people or communities

- recent immigrants (including refugees)

- members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, 2‑spirit, and other communities (LGBTQ2+)

- veterans

- Indigenous people

- young adults

- people experiencing homelessness

5.8 The housing needs of priority vulnerable groups, including those experiencing homelessness and chronic homelessness, vary by individual. However, some housing types, such as transitionalDefinition 2 and supportive housingDefinition 3, can help these groups achieve housing stability.

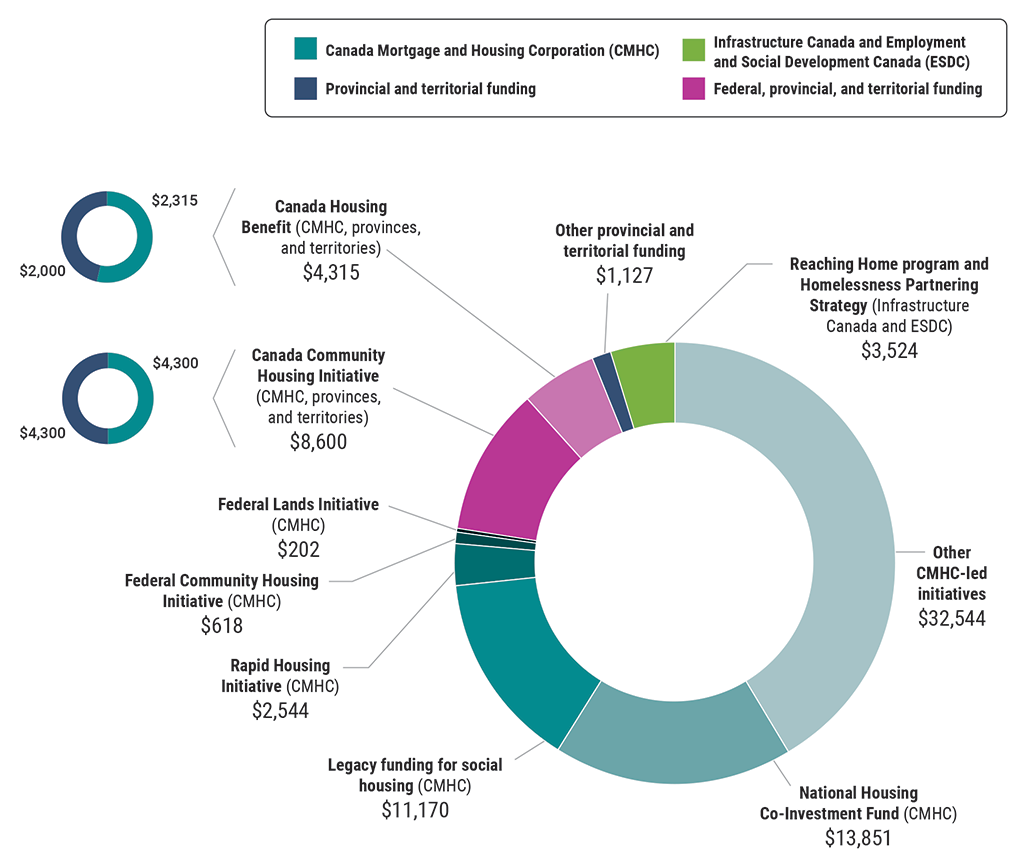

5.9 Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. The corporation leads the National Housing Strategy. It oversees the majority of the $78.5 billion of funding for the strategy (Exhibit 5.3), which is primarily allocated to build, repair, and provide subsidies for housing. The corporation is responsible for reporting on the status of the strategy and the achievement of the strategy’s key targets. These targets include the following by the 2027–28 fiscal year:

- removing 530,000 households from housing need

- protecting 385,000 community housingDefinition 4 units (through affordability support, repair, renovation, and adaptation) and creating an additional 50,000 community housing units

- providing 300,000 households with affordability support through the Canada Housing Benefit

- reducing chronic homelessness by 50%

- repairing and renewing 300,000 existing housing units

- creating 100,000 new housing units

Exhibit 5.3—Breakdown of $78.5 billion in planned spending under the National Housing Strategy (amounts shown are in millions of dollars)

Note: As part of the Budget 2022 announcement, an additional $580 million was announced for the Reaching Home program and an additional $2 billion was announced for CMHC‑led initiatives. These amounts are not included above.

Source: Adapted from various public sources and documents provided by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation and Infrastructure Canada

Exhibit 5.3—text version

This pie chart shows the breakdown of $78.5 billion in planned spending under the National Housing Strategy (amounts are in millions of dollars).

The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), Infrastructure Canada, Employment and Social Development Canada, provinces, and territories receive funding under the strategy for the following programs:

- National Housing Co‑Investment Fund is a Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation program that planned to spend $13,851,000,000.

- Legacy funding for social housing is a Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation program that planned to spend $11,170,000,000.

- Rapid Housing Initiative is a Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation program that planned to spend $2,544,000,000.

- Federal Community Housing Initiative is a Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation program that planned to spend $618,000,000.

- Federal Lands Initiative is a Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation program that planned to spend $202,000,000 in provincial and territorial funding.

- Canada Community Housing Initiative is a program that planned to spend $8,600,000,000 in federal, provincial, and territorial funding. The program is administered by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, provinces, and territories.

- Of this, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation planned to spend $4,300,000,000, and the provinces and territories planned to spend $4,300,000,000.

- Canada Housing Benefit is a program that planned to spend $4,315,000,000 in federal, provincial, and territorial funding and is administered by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, provinces, and territories.

- Of this, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation planned to spend $2,315,000,000, and the provinces and territories planned to spend $2,000,000,000.

- Reaching Home program and Homelessness Partnering Strategy is a program that planned to spend $3,524,000,000 in funding and is facilitated by Infrastructure Canada and Employment and Social Development Canada.

- The provinces and territories planned to spend $1,127,000,000 in other funding that they provided.

- Other CMHC‑led initiatives planned to spend $32,544,000,000.

5.10 Some of the initiatives under the National Housing Strategy targeted to meet the housing needs of priority vulnerable groups are also intended to complement Reaching Home, the federal homelessness program. Vulnerable groups, including some of those identified in the National Housing Strategy, are more susceptible to becoming homeless. By delivering federal housing programs and services, the corporation has a key role in helping prevent and reduce chronic homelessness.

5.11 Employment and Social Development Canada. Launched in 2019 by Employment and Social Development Canada, Reaching Home is the National Housing Strategy’s homelessness program. It is the most recent iteration of the federal homelessness program, which has existed since 1999. It is a $3.4 billion, 9‑year program under the National Housing Strategy (Exhibit 5.3), and its ultimate goal is to prevent and reduce homelessness. Reaching Home also uses the National Housing Strategy’s commitment to reduce chronic homelessness by 50% by 2027–28 as a target to measure success.

5.12 In fall 2021, responsibility for Reaching Home was transferred from Employment and Social Development Canada to Infrastructure Canada. Despite this transfer, Employment and Social Development Canada retains some responsibilities for regional delivery and oversight of the program, such as monitoring funding agreements through Service Canada.

5.13 Infrastructure Canada. This department leads the Reaching Home program and is responsible for measuring performance and for reporting on national homelessness outcomes. It is also responsible for sharing information and best practices with partners across Canada who provide supports for people experiencing homelessness. This includes reporting on progress toward the National Housing Strategy target to reduce chronic homelessness in Canada by 50% by the 2027–28 fiscal year and coordinating with the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation on the federal approach to housing and homelessness.

5.14 Through the Reaching Home program, Infrastructure Canada provides direct support and funding to 64 designated communities (urban centres that are outside the territories and that face significant issues with homelessness) and to Indigenous, territorial, and rural or remote communities across Canada. Communities use this funding to support activities such as the following:

- connecting people experiencing homelessness with more stable housing and supports

- preventing those at imminent risk of experiencing homelessness from becoming homeless

- promoting the coordination of services within the community

5.15 Other federal organizations. Other federal organizations also have responsibilities related to homelessness, such as Veterans Affairs Canada and Indigenous Services Canada. Several federal organizations also have responsibilities related to the priority vulnerable groups identified in the National Housing Strategy.

5.16 Other levels of government and partners. Provincial, territorial, and municipal governments, along with non‑government organizations, also fund and deliver services to people experiencing homelessness, including providing access to shelters and a range of medical, social, and support services. These partners also deliver and administer housing construction and repair projects and supports in their regions. While some of these services may be funded in part through the Reaching Home program and other National Housing Strategy initiatives, these groups may also provide services funded by other means, independent of the federal government.

Focus of the audit

5.17 This audit focused on whether Employment and Social Development Canada and Infrastructure Canada prevented and reduced chronic homelessness through interventions that helped those at risk of or experiencing homelessness and chronic homelessness obtain housing and supports needed to remain housed.

5.18 This audit also focused on whether the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation contributed to the prevention and reduction of chronic homelessness through its delivery and administration of federal housing programs and services that address the housing needs and improve housing outcomes for vulnerable Canadians.

5.19 This audit is important because experiencing homelessness, including chronic homelessness, affects an individual’s health, security, stability, and participation in society and the economy.

5.20 Addressing chronic homelessness through both housing and supports, such as discharge planning services for people leaving public systems (for example, health, corrections, and child welfare systems) is important. Without permanent housing options, the supports to prevent people from experiencing homelessness, and the supports to enable people experiencing chronic homelessness to transition out of temporary locations into permanent housing, it is not possible to reduce chronic homelessness.

5.21 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings and Recommendations

Overall message

5.22 Overall, Infrastructure Canada, Employment and Social Development Canada, and the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation did not know whether their efforts improved housing outcomes for people experiencing homelessness or chronic homelessness and for other vulnerable groups.

5.23 As the lead for Reaching Home, a program within the National Housing Strategy, Infrastructure Canada spent about $1.36 billion between 2019 and 2021—about 40% of total funding committed to the program—on preventing and reducing homelessness. However, the department did not know whether chronic homelessness and homelessness had increased or decreased since 2019 as a result of this investment.

5.24 For its part, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, as the lead for the National Housing Strategy, spent about $4.5 billion and committed about $9 billion but did not know who was benefiting from its initiatives. This was because the corporation did not measure the changes in housing outcomes for priority vulnerable groups, including people experiencing homelessness. We also found that rental housing units approved under the National Housing Co‑Investment Fund that the corporation considered affordable were often unaffordable for low‑income households, many of which belong to vulnerable groups prioritized by the strategy.

5.25 Despite being the lead for the National Housing Strategy and overseeing the majority of its funding, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation took the position that it was not directly accountable for addressing chronic homelessness. Infrastructure Canada was also of the view that while it contributed to reducing chronic homelessness, it was not solely accountable for achieving the strategy’s target of reducing chronic homelessness. This meant that despite being a federally established target, there was minimal federal accountability for its achievement.

5.26 Moreover, the initiatives under the strategy were not integrated, and the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation and Infrastructure Canada were not working in a coordinated way. In our view, without better alignment of their efforts, Infrastructure Canada and the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation are unlikely to achieve the federal National Housing Strategy target of reducing chronic homelessness by 50% by the 2027–28 fiscal year.

Addressing chronic homelessness

Infrastructure Canada and Employment and Social Development Canada did not know whether their efforts to prevent and reduce chronic homelessness were leading to improved outcomes

5.27 We found that Employment and Social Development Canada and Infrastructure Canada did not know whether chronic homelessness and homelessness overall had increased or decreased since 2019. The departments did not analyze up‑to‑date national shelter‑use data and other data to understand changes in the homeless population. The departments also did not have up‑to‑date and complete data on program results to determine whether program adjustments were required to better support those experiencing homelessness. Furthermore, it was unlikely that Infrastructure Canada would achieve its targets for community implementation of coordinated accessDefinition 5.

5.28 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

- Not known whether chronic homelessness and homelessness had increased or decreased

- Incomplete collection and analysis of data on Reaching Home project results and use of pandemic funding

- Meeting coordinated access implementation targets unlikely

5.29 This finding matters because without up‑to‑date data and analysis related to homelessness and chronic homelessness, the departments cannot know whether progress has been made and whether program adjustments may be required to support communities’ efforts. Furthermore, up‑to‑date national homelessness data would help build community capacity to address homelessness and chronic homelessness by improving the understanding of the issue across Canada. It would also support the adoption of data‑driven approaches to address homelessness and chronic homelessness across the country through federal leadership.

5.30 The departments spent about $1.4 billion through the Reaching Home program from the 2019–20 fiscal year to the 2020–21 fiscal year (about 40% of the $3.4 billion in planned spending for the program) to support projects intended to prevent and reduce homelessness. These included projects to help communities deliver urgent homelessness supports to respond to the COVID‑19 pandemic. As part of its leadership role, Infrastructure Canada provides communities with tools and funding to address homelessness and chronic homelessness. In exchange, communities provide the department with data, including

- national shelter‑use data

- data from biannual community‑led point‑in‑time counts that enumerate individuals using shelters and transitional housing and living in unsheltered locations

- results from projects funded through Reaching Home

This data is to be used to measure program performance against national indicators. This data is also to be used to assess whether outcomes were improving for people experiencing homelessness and chronic homelessness, to improve the understanding of homelessness nationally, and to support policy and program development.

5.31 The Reaching Home program introduced coordinated access to help match individuals with the right housing at the right time and to provide services for those most in need. Coordinated access represents a transformation in the way that communities deliver services to address homelessness. Infrastructure Canada is responsible for providing funding, training, and technical assistance to communities to enable them to offer coordinated access. According to Infrastructure Canada, communities that have been successful in reducing chronic homelessness have done so in part by using data‑driven decision making and developing a coordinated local homelessness system.

5.32 Coordinated access is also intended to help communities develop targeted, evidence-based responses to address local homelessness. This includes addressing the needs of vulnerable groups such as Indigenous people, youth, and people with disabilities. According to Infrastructure Canada, without a coordinated approach, people experiencing homelessness must navigate a complicated network of connected—but uncoordinated—services. They often have to tell their story multiple times and place themselves on a number of waiting lists to secure the housing resources they need.

Not known whether chronic homelessness and homelessness had increased or decreased

5.33 Infrastructure Canada established 3 targets to measure progress toward the Reaching Home program goal of preventing and reducing homelessness (Exhibit 5.4). This included a target to reduce the number of shelter users experiencing chronic homelessness by 31% by the 2023–24 fiscal year and by 50% by the 2027–28 fiscal year. To measure progress against this target, the department used national shelter‑use data and compared its annual estimates of chronic homelessness with baseline estimates established in 2016.

Exhibit 5.4—Uncertain results for key indicators used for measuring progress toward preventing and reducing homelessness

| Indicator | Targets and timelines | Baseline | Results (fiscal year) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019–20 | 2020–21 | 2021–22 | |||

| Percentage of applicable designated communities in which the number of new homeless individuals decreases | 66% by the 2023–24 fiscal year | Baselines vary by community. | Not availableNote * | Not availableNote * | Results not due until fall 2022 |

| Estimated number of individuals using emergency shelters | 15% reduction by the 2027–28 fiscal year | 129,127 is the estimated number of people who used emergency shelters in 2016. | 118,759 (decrease of 8%) |

Not availableNote ** | Not availableNote ** |

| Estimated number of shelter users who are chronically homeless | 31% reduction by the 2023–24 fiscal year, and 50% reduction by the 2027–28 fiscal year | 26,900 is the estimated number of shelter users who were chronically homeless in 2016. | 29,927 (increase of 11.3%) |

Not availableNote ** | Not availableNote ** |

5.34 We found that Infrastructure Canada was not able to measure progress toward its prevention target because of challenges with the data. For its goals of reducing homelessness and chronic homelessness, the most recent shelter data reported by the department was from 2019. The department told us that it had some data from 2020 and 2021 but that the data was not sufficiently complete for estimating results. We found that the department had engaged a consultant to examine challenges related to the collection, management, and processing of national shelter‑use data. The department’s 2019 analysis indicated a disparity between homelessness—an 8% decrease—and chronic homelessness—an 11% increase. The absence of more recent results meant that the department did not know whether homelessness and chronic homelessness had increased or decreased since 2019, and what impact the COVID‑19 pandemic had on rates of homelessness and chronic homelessness.

5.35 Despite identifying changing trends in homelessness and chronic homelessness, the department did not examine why this was happening. Although shelter‑use data alone may not have accurately portrayed the state of homelessness nationally because it excluded those outside the shelter system, supplemental data such as analysis from point‑in‑time counts may have helped explain some of the reasons for these changes. This is because these counts included people in transitional housing and unsheltered locations. According to Infrastructure Canada’s analysis, results from 58% of Reaching Home communities that completed point‑in‑time counts between 2020 and 2021 suggested that homelessness had increased nationally by 6.6% since 2018. However, we found that the department had not conducted further analysis of these and other sources of data to understand why these results were not consistent with the decline in the number of shelter users.

5.36 We also found that Infrastructure Canada’s analysis of 2019 shelter‑use data identified trends and changes in the homeless population, including its subpopulations. For example, the analysis showed that occupancy rates at shelters serving families had steadily increased since 2016 and that the number of refugees or refugee claimants using shelters was 4 times greater than it was in 2014. The department’s analysis did not explore why rates of shelter use among families, refugees, and refugee claimants were increasing.

Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable

Source: United NationsFootnote 1

5.37 The lack of a more recent estimate of chronic homelessness meant that the department did not report up‑to‑date information or make adjustments so that the Reaching Home program met its objectives and contributed to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. Specifically, Goal 11 is to make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable. A Canadian target related to this goal is to reduce chronic homelessness by at least 31% by March 2024. In our view, given the results as of 2019, it is unlikely this target will be met unless significant actions are taken.

5.38 Without timely and comprehensive analysis and reporting of up‑to‑date national shelter use and other sources of data, the department’s ability to lead national responses to emerging homelessness trends, provide targeted support to local responses, and adjust its programs where required was limited. Our recommendation in this area is in paragraph 5.45.

Incomplete collection and analysis of data on Reaching Home project results and use of pandemic funding

5.39 We found that Infrastructure Canada had not completed its analysis of results from Reaching Home–funded projects. Between the 2019–20 fiscal year and the 2020–21 fiscal year, communities allocated about $356 million in program funding to projects that required results to be reported annually. The department was to use these results to measure its progress against several performance indicators. At the time of our audit, the department told us that it had collected and analyzed about 70% of the results from that period. Results for projects funded in the 2021–22 fiscal year were not due until after the end of our audit period. We found that the department’s collection and analysis of results were delayed in part because of decisions to extend community reporting deadlines and defer the implementation of an online reporting platform. Although these decisions were made to facilitate pandemic response, they limited the department’s ability to assess the program’s contribution to improving outcomes for those experiencing homelessness and chronic homelessness and those at risk of becoming homeless.

5.40 We found that the department’s analysis of project results that it had collected showed that about $128 million in funding for housing placement activities between the 2019–20 fiscal year and the 2020–21 fiscal year helped place about 21,500 individuals in more stable housing. This represented about 30% of the program’s target of placing 71,500 individuals by 31 March 2022. Because the department’s data and analysis for these 2 fiscal years were incomplete, it did not know whether it was on track to meet the 2022 target. It was also unable to determine whether it was on track to meet its target of placing 115,850 individuals in more stable housing by the end of March 2024.

5.41 We found that Employment and Social Development Canada considered gender-based analysis plusDefinition 6 in the design of the Reaching Home program. For example, the program required communities to provide demographic data broken down by population and gender in order to measure the program’s impact on target populations. Reaching Home identified 18 vulnerable subpopulations that could be targeted by funded projects, consistent with the 11 groups prioritized by the National Housing Strategy, such as veterans, people with disabilities, and members of the LGBTQ2+ communities.

5.42 However, we found that the departments did not collect project result data for all targeted populations and did not consistently obtain information on gender identity for those benefiting from the program. For example, Infrastructure Canada did not know the gender of 20% of individuals who were placed in more stable housing because this information was not provided by some funding recipients from the 2019–20 to 2020–21 fiscal years. Without this information, the department could not determine whether outcomes were improving for specific groups (categorized by gender and other identity factors), and whether different approaches were needed.

5.43 We also found that despite challenging circumstances due to the COVID‑19 pandemic, the departments quickly delivered about $709 million in COVID‑19 homelessness response funding to communities between the 2019–20 fiscal year and the 2021–22 fiscal year. To help communities respond to health risks facing the homeless population, the departments allowed for flexibility in spending existing Reaching Home funding. For example, restrictions on funding health and medical services were lifted to allow communities to hire healthcare professionals to provide services to people experiencing homelessness and chronic homelessness.

5.44 Infrastructure Canada received reports from most of the communities related to the COVID‑19 response funding they had received. However, we found that the department had not completed its analysis to determine what had been achieved. The department’s analysis completed to date suggested that the program had exceeded its target for creating new temporary accommodations in response to the pandemic. However, the department’s analysis of other pandemic-related targets and community reporting on the use of pandemic funding had not been completed. Understanding the impacts of the COVID‑19 pandemic on homelessness is important for the departments and communities so that programs can be adjusted, if necessary, to achieve the best value and address emerging needs stemming from the pandemic.

5.45 Recommendation. Infrastructure Canada should

- collect and analyze data in a timely manner so that it can report up‑to‑date results on homelessness and chronic homelessness

- finalize the implementation of its online reporting platform

- use the information and data that it collects to determine why trends in homelessness are emerging and how its programs are addressing the needs of people experiencing homelessness and chronic homelessness

- use the information that it collects and the resulting analysis to make program adjustments where required

Infrastructure Canada’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Meeting coordinated access implementation targets unlikely

5.46 Implementing coordinated access was a transformation intended to give communities the tools and support they needed to develop local, evidence-based responses to homelessness. It was also part of the data-driven approach recommended by the national consultations to address homelessness. Although implementation was affected by the COVID‑19 pandemic, Infrastructure Canada did not revise its implementation timelines.

5.47 For the 2021–22 fiscal year, the Reaching Home program required that coordinated access be implemented in 29 of 44 (66%) eligible designated communities. By the 2023–24 fiscal year, all 64 designated communities were to have implemented it. We found that as of March 2021, 9 (about 20%) of the 44 eligible communities reported that they had fully implemented it, 1 year in advance of the required timeline.

5.48 Infrastructure Canada had analyzed progress reported by communities and developed recommendations to help them implement coordinated access. However, we found that the department had no action plans or timelines to support communities in meeting the 2023–24 target. Given that coordinated access was intended to improve housing outcomes for people experiencing homelessness and chronic homelessness by matching those most in need with available housing, it is critical that Infrastructure Canada work with communities to understand their challenges and provide the necessary supports to help facilitate timely implementation.

5.49 Recommendation. Infrastructure Canada should collaborate with designated communities and other partners to develop an action plan with timelines to address the barriers to the implementation of coordinated access that were identified in its analysis of community reporting.

Infrastructure Canada’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation did not know who was benefiting from its initiatives

5.50 We found that the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation did not know who was benefiting from its initiatives. While the corporation knew vulnerable groups were intended to benefit, it did not know whether those groups were actually occupying housing supported by its initiatives. Moreover, it did not measure the changes in housing outcomes for priority vulnerable groups. We also found that rental units approved under the National Housing Co‑Investment Fund that the corporation considered affordable were often unaffordable to low‑income households.

5.51 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

- Minimal measurement of housing outcomes for priority vulnerable groups

- Rental housing considered affordable and approved under the National Housing Co‑Investment Fund often unaffordable for low‑income households

5.52 This finding matters because addressing housing needs for the most vulnerable Canadians, including people experiencing homelessness, promotes social and economic inclusion for individuals and families, reduces the number of households in core housing need, and contributes to preventing and reducing chronic homelessness.

5.53 The National Housing Strategy includes construction and repair and support and subsidy initiatives led by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. Some of these are intended to complement the Reaching Home program (the strategy’s homelessness support program) by addressing the housing needs of priority vulnerable groups, including people at risk of and experiencing homelessness.

5.54 We examined 6 of the corporation’s National Housing Strategy initiatives related to addressing the housing needs of

- priority vulnerable groups, including people experiencing homelessness

- those at risk of homelessness

- low‑income households

Overall, these 6 initiatives (Exhibit 5.5) represented about 38% of the $78.5 billion allocated to the National Housing Strategy over 10 years.

Exhibit 5.5—Targets for the National Housing Strategy’s initiatives only measured outputs

| Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation rent and subsidy programs | Housing type and target | Funding as of 31 March 2022 | Progress as of 31 March 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Canada Housing Benefit

|

Community housing Affordable housing Target: Reduce or eliminate housing need for 300,000 households by the 2027–28 fiscal year |

Budgeted: $4.3 billion in subsidies, including provincial and territorial cost matching administration costs (Exhibit 5.3) Committed: $297 million Spent: $135 million |

Provinces and territories have committed support to more than 133,100 households. |

|

Canada Community Housing Initiative

|

Community housing Target: Protect 330,000 community housing units until the 2027–28 fiscal year |

Budgeted: $8.6 billion in joint investments, including provincial and territorial cost matching (Exhibit 5.3) Committed: $839 million Spent: $490 million |

Provinces and territories have committed support to more than 146,900 units. |

|

Federal Community Housing Initiative

|

Community housing Target: Protect 55,000 community housing units by providing rent supplements to as many as 13,700 low‑income households until the 2027–28 fiscal year |

Budgeted: $618 million in subsidy extensions and rent assistance, including administration costs Committed: $217 million Spent: $87.5 million |

Provided subsidies to support more than 32,900 community housing units, including 6,100 low‑income units. |

|

National Housing Co‑Investment Fund

|

Emergency shelters Transitional housing Supportive housing Community housing Affordable housing Target: Create 60,000 new units and repair or renew 240,000 existing units by the 2027–28 fiscal year |

Budgeted: $13.9 billion in loans (low‑interest and/or forgivable) and contributions, including administration costs Committed: $5.3 billion Spent: $1.4 billion |

More than 3,400 units were built, 11,300 are currently being built, and CMHC has committed to build an additional 6,700 units. More than 18,600 units were repaired or renewed, 66,900 units are being repaired or renewed, and CMHC has committed to repair or renew an additional 6,500 units. |

|

Rapid Housing Initiative

|

Transitional housing Supportive housing Community housing Affordable housing Target: Create 7,500 affordable units by the 2023–24 fiscal year |

Budgeted: $2.5 billion in contributions, including administration costs Committed: $2.5 billion Spent: $2.4 billion |

More than 800 units were built, more than 6,400 are currently being built, and CMHC has committed to build an additional almost 3,000 units. |

|

Federal Lands Initiative

|

Emergency shelter Transitional housing Supportive housing Community housing Affordable housing Market housing Target: Create 4,000 new units by the 2027–28 fiscal year |

Budgeted: $202 million in loans, including administration costs Committed: $109 million Spent: $17.7 million |

Agreements have been signed to create more than 400 units, and CMHC has committed to creating another 2,800 units. |

|

Source: Adapted from Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation public reporting and data |

|||

Minimal measurement of housing outcomes for priority vulnerable groups

5.55 We found that the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation completed a gender-based analysis plus assessment as part of designing the National Housing Strategy. As part of the assessment, the corporation considered how specific demographic groups experience housing need, including affordability challenges. However, we also found that the corporation did not collect the demographic data broken down by population and gender that it needed to measure the impact of strategy initiatives on specific gender-identity groups within priority vulnerable populations. This meant that it did not know whether outcomes were improving for those specific groups of people or whether different approaches were required to address the needs of specific subpopulations.

5.56 We found that the corporation had analyzed data and reported on the broader National Housing Strategy targets (Exhibit 5.5), but it did not analyze the impact of the strategy on vulnerable groups. While the corporation measured and reported on outputs, such as the total number of units built, it did not measure outcomes for vulnerable groups, such as how many people were being housed and which vulnerable groups were being helped by its initiatives. The corporation also did not define what successful prioritization of vulnerable groups meant. Therefore, the corporation could not determine if vulnerable groups and those in greatest need were benefiting as intended. While the strategy addresses housing needs across the entire housing continuum, the primary goal of the National Housing Strategy is to make safe and affordable housing accessible for the most vulnerable Canadians and for those struggling to make ends meet.

5.57 We also found that the corporation did not know who was being housed and receiving supports from the initiatives we examined. For the Rapid Housing Initiative and the National Housing Co‑Investment Fund, although the corporation knew that housing types likely to benefit vulnerable groups, such as transitional and supportive housing, were being funded, the corporation did not know whether priority vulnerable groups who were intended to benefit from approved projects were actually housed once projects were completed. For example, it did not know whether units intended for people with disabilities were actually occupied by this population. For the Federal Lands Initiative, it was too soon to determine if priority vulnerable groups were actually housed. For the 3 subsidy initiatives we examined, we found that while the corporation knew that supports were being provided to protect the supply of social housing units and that affordability supports were being provided to households in housing need, it did not know which vulnerable groups actually benefited or whether those in greatest need were being helped.

5.58 Some of the initiatives we examined were intended to complement the Reaching Home program to prevent and reduce homelessness by providing rent supports, protecting and expanding social housing, and building and providing units with affordability linked to income. According to the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, as of 31 March 2022, more than $9 billion had been committed to the 6 initiatives we examined, and about $4.5 billion had been spent, which is about 30% and 15% of planned spending respectively. However, without knowing who was benefiting from its initiatives, the corporation did not know whether it was achieving good value for money and meeting its commitments. Our recommendation in this area is in paragraph 5.62.

Rental housing considered affordable and approved under the National Housing Co‑Investment Fund often unaffordable for low‑income households

5.59 We found that the National Housing Co‑Investment Fund had a measure for affordable housing that was not the same as the National Housing Strategy overall. The result of this was that rent for approved housing was often unaffordable for low‑income households, many of whom belong to priority vulnerable groups. In the strategy, affordable rent is calculated as less than 30% of before‑tax income. In the National Housing Co‑Investment Fund, affordable rent is based on rent being less than 80% of median market rent. We calculated that rent for units approved under the initiative were typically about 63% of median market rent, which was less expensive than the 80% criterion. When we compared rent using the 2 affordability measures, we found that overall low‑income households would have to spend 30% or more of their before‑tax income on rent (Exhibit 5.6).

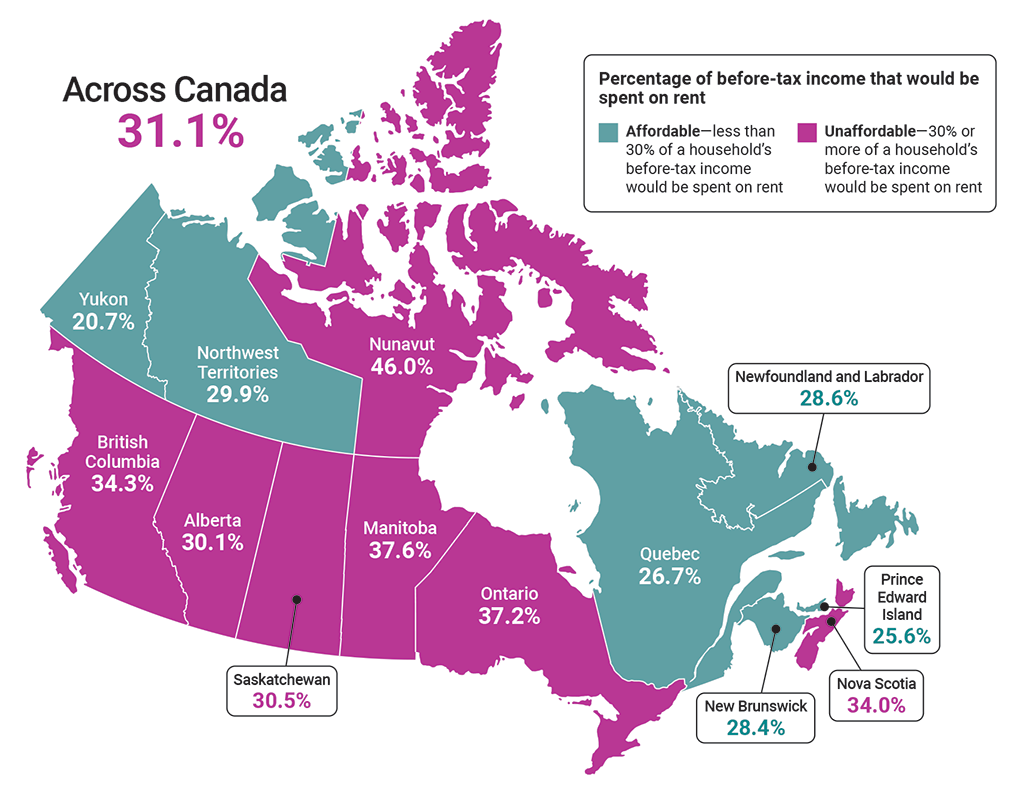

Exhibit 5.6—Rental housing units considered affordable and approved under the National Housing Co‑Investment Fund were often unaffordable for low-income households across Canada in 2020

Text version

This map of Canada shows the percentage of before‑tax income that would be spent on rent in each province and territory in 2020. For each province and territory, the maps shows whether rent would be affordable or unaffordable for low‑income households, according to data from 2020. The map shows that low‑income households would afford rent in 2 territories and 4 provinces and would not afford rent in 1 territory and 7 provinces.

A table under the map shows rent and income amounts rounded to the nearest $10. Amounts are based on data published at the national, provincial, and territorial levels.

According to Statistics Canada, low‑income households are defined as having after‑tax income of less than half of the median after‑tax income (for example, if median income is $50,000, the maximum income to be considered low income would be $25,000).

| Regions | Maximum annual before‑tax income for low‑income households that rentNote 1, Note 2, Note 3 | Maximum affordable monthly rentNote 2, Note 3 (less than 30% of before‑tax income) | Monthly rent at about 63% of median market rentNote 2, Note 3, Note 4 | Percentage of before‑tax income that would be spent on rent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Across Canada | $24,230 | $600 | $630 | 31.1% |

| Alberta | $28,690 | $710 | $720 | 30.1% |

| British Columbia | $28,540 | $710 | $820 | 34.3% |

| Manitoba | $21,130 | $520 | $660 | 37.6% |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | $22,280 | $550 | $530 | 28.6% |

| New Brunswick | $21,180 | $530 | $500 | 28.4% |

| Northwest Territories | $44,570 | $1,110 | $1,110Note 5 | 29.9% |

| Nova Scotia | $22,690 | $560 | $640 | 34.0% |

| Nunavut | $45,570 | $1,130 | $1,750Note 5 | 46.0% |

| Ontario | $25,860 | $640 | $800 | 37.2% |

| Prince Edward Island | $25,660 | $640 | $550 | 25.6% |

| Quebec | $21,810 | $540 | $490 | 26.7% |

| Saskatchewan | $24,710 | $610 | $630 | 30.5% |

| Yukon | $47,090 | $1,170 | $810Note 5 | 20.7% |

|

Source: Based on data published by Statistics Canada and data published and provided by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation |

||||

5.60 According to the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, affordability was the primary reason that about 76% of Canadian households were in core housing need and in 2016, the majority (66%) of households in core housing need were renting. Furthermore, more than 85% of Canadian households in core housing need had a before‑tax income of less than $50,000. This meant that monthly rent would need to be less than $1,250 to be considered affordable.

5.61 Also according to the corporation, many of the priority vulnerable groups, including Indigenous people and recent immigrants, were overrepresented in lower-income brackets and more likely to be in core housing need than the Canadian average. Producing affordable rental units for low‑income households is critical to meeting the needs of these groups and contributing to preventing and reducing chronic homelessness. Having affordability criteria linked to market rent will continue to produce housing that is unaffordable to many of these groups.

5.62 Recommendation. The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation should assess the impact of its programs on vulnerable groups at all stages of its National Housing Strategy initiatives. The corporation’s efforts should include the following:

- Define the housing needs of vulnerable groups, how it will prioritize meeting those needs, and what the successful result of this prioritization would be.

- Develop performance measures and report on whether housing outcomes for vulnerable groups are improving.

- Verify who is being housed in units generated and supported by its initiatives and use this data to determine whether program adjustments are required so that the housing needs of vulnerable groups are met.

- Take the necessary steps to align the definitions of affordability for all initiatives so that they are consistent.

The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Minimal federal accountability for reaching the National Housing Strategy target to reduce chronic homelessness by 50% by the 2027–28 fiscal year

5.63 We found that although the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation is the lead of the National Housing Strategy, the corporation took the position that it was not directly accountable for the achievement of the strategy’s target to reduce chronic homelessness by 50% by the 2027–28 fiscal year. Infrastructure Canada took the position that it was not solely accountable for the target’s achievement. This meant that despite being a federal target, there was minimal accountability at the federal level for its achievement and for making sure that funds spent resulted in the intended outcome. While many partners must work together to address homelessness and chronic homelessness, we expected clear federal accountability to meet the target.

5.64 We also found that Infrastructure Canada’s Reaching Home program and the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation–led National Housing Strategy initiatives we examined were not well integrated. In our view, the organizations did not have effective mechanisms and a well‑coordinated approach with each other to address chronic homelessness and the housing needs of other priority vulnerable groups.

5.65 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

- Minimal federal accountability for the National Housing Strategy target to reduce chronic homelessness

- Federal housing and homelessness initiatives not well integrated or coordinated

5.66 This finding matters because an accountability gap for the achievement of the National Housing Strategy chronic homelessness target means that no one is making sure that initiatives are aligned and that the funds spent actually result in the intended outcome. In addition, housing and homelessness are long‑standing issues that require an integrated and coordinated approach to improve outcomes and get the best value for money.

5.67 Responses to housing and homelessness are advanced through federal leadership, which helps guide, influence, and support efforts and local responses toward addressing housing and homelessness challenges, including chronic homelessness. Infrastructure Canada and the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation are accountable, through the National Housing Strategy, for addressing the housing needs of priority vulnerable groups, including people experiencing homelessness. Employment and Social Development Canada has a supporting role.

5.68 Infrastructure Canada and Employment and Social Development Canada have expertise and an established role in supporting the sector that serves people experiencing homelessness. The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation has expertise and an established role in providing capital construction and repair assistance for housing. Employment and Social Development Canada and the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation committed to working together in 2006 to ensure coordination and good governance of the federal approach to housing and homelessness through a memorandum of understanding. This memorandum was updated again in 2019. When the Reaching Home program was transferred to Infrastructure Canada in 2021, the department told us that this memorandum of understanding was still in effect and would be revised to reflect the partnership between it and the corporation.

Minimal federal accountability for the National Housing Strategy target to reduce chronic homelessness

5.69 The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation is the lead for the National Housing Strategy and oversees the majority of its funding. However, the corporation took the position that it was not directly accountable for the achievement of the federal National Housing Strategy target to reduce chronic homelessness by 50% and that its initiatives in the strategy did not specifically target chronic homelessness. In our view, this position creates a significant gap because of the interconnected nature of housing and homelessness. Furthermore, it is critical that the corporation, as the lead for the strategy, define how its housing initiatives will contribute to the achievement of the 50% reduction in chronic homelessness.

5.70 Infrastructure Canada is the lead federal department responsible for addressing homelessness, and the Reaching Home program was the only initiative in the National Housing Strategy dedicated to addressing chronic homelessness. The department acknowledged accountability for contributing to and reporting on the status of the National Housing Strategy target to reduce chronic homelessness by 50% by the 2027–28 fiscal year through the Reaching Home program. However, it considered accountability for the achievement of the target to be shared among a range of stakeholders, community service providers, and other levels of government. This meant that despite being a federally established target, there was minimal federal accountability for its achievement and it was unclear how federal organizations were working together to do so. Our recommendation in this area is in paragraph 5.74.

Federal housing and homelessness initiatives not well integrated or coordinated

5.71 We found that the National Housing Strategy initiatives led by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation and Infrastructure Canada’s Reaching Home program were not well integrated. This was despite the fact that the strategy indicated that some initiatives led by the corporation were to be complementary to the Reaching Home program and that the strategy was to help reduce chronic homelessness by supporting communities to deliver a combination of housing measures.

5.72 We also found that the organizations’ efforts to coordinate with each other were limited. This was despite the organizations’ acknowledgement that collaboration and coordination within and outside the federal government are vital to addressing the housing needs of priority vulnerable groups and to reducing chronic homelessness. For example, we found that Infrastructure Canada was a member of the project selection committee for the corporation’s $202 million Federal Lands Initiative. On this committee, Infrastructure Canada was responsible for sharing its homelessness expertise and for contributing its recommendations during project selection. However, for other initiatives, such as the Rapid Housing Initiative and the National Housing Co‑Investment Fund that ranged in planned spending from $2.5 to $13.9 billion, we found no similar mechanisms for the department to provide its input and expertise to the corporation.

5.73 We found that there was no mechanism in place to ensure that efforts around providing support services and housing were aligned. There is currently no single National Housing Strategy initiative that includes building and repairing housing units and providing comprehensive services. For this reason, it is important that the department‑led Reaching Home program, where about 80% of funding was allocated by communities to support services, be well integrated and coordinated with the construction initiatives led by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. These include the National Housing Co‑Investment Fund and the Rapid Housing Initiative, where about $821 million in funding has been committed to building transitional and supportive housing, which are recognized as options that can help people experiencing chronic homelessness and other vulnerable groups achieve housing stability. In our view, without this integration and coordination, it is unlikely that the current National Housing Strategy will achieve its target of reducing chronic homelessness by 50% by the 2027–28 fiscal year.

5.74 Recommendation. The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation and Infrastructure Canada should

- align, coordinate, and integrate their efforts to prevent and reduce homelessness and chronic homelessness

- engage with central agencies to clarify accountability for the achievement of the National Housing Strategy targets to eliminate gaps

Response of each entity. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Conclusion

5.75 Infrastructure Canada and Employment and Social Development Canada did not know whether their efforts to prevent and reduce chronic homelessness were achieving the intended results. This was because the departments did not analyze up‑to‑date homelessness data to assess whether interventions intended to help people at risk of or experiencing homelessness and chronic homelessness obtained the housing and supports they needed.

5.76 Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation did not know whether it was addressing the housing needs of and improving housing outcomes for vulnerable Canadians and contributing to the prevention and reduction of chronic homelessness. The corporation did not know who was benefiting from its initiatives or whether housing outcomes were improving for priority vulnerable populations, including people experiencing chronic homelessness. We also concluded that rental housing considered affordable and approved under the National Housing Co‑Investment Fund was often unaffordable for low‑income households, many of whom belong to vulnerable groups.

5.77 We also concluded that there was minimal federal accountability for the achievement of the National Housing Strategy target to reduce chronic homelessness by 50% by the 2027–28 fiscal year. In addition, Infrastructure Canada’s and the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s initiatives were not well integrated and the 2 entities were not working in a coordinated way to deliver on the strategy’s objectives.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on chronic homelessness in Canada. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs and to conclude on whether Infrastructure Canada, Employment and Social Development Canada, and the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements, set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada applies the Canadian Standard on Quality Control 1 and, accordingly, maintains a comprehensive system of quality control, including documented policies and procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate

Audit objective

The objectives of this audit were to determine whether

- Employment and Social Development Canada and Infrastructure Canada prevented and reduced chronic homelessness through interventions that helped those at risk of or experiencing homelessness obtain housing and supports needed to remain housed

- the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation contributed to the prevention and reduction of chronic homelessness by addressing the housing needs and improving housing outcomes for vulnerable Canadians

Scope and approach

The audit included an examination of Employment and Social Development Canada’s and Infrastructure Canada’s efforts to prevent and reduce chronic homelessness in Canada. It also included an examination of the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s role in contributing to the prevention and reduction of chronic homelessness by addressing the housing needs and improving housing outcomes for vulnerable Canadians.

The audit involved examining and analyzing key documents from the departments and the corporation. This included data from Employment and Social Development Canada, Infrastructure Canada, and the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation.

We interviewed officials from each of the entities and from other federal departments with responsibilities related to homelessness and/or vulnerable groups identified in the National Housing Strategy. We also interviewed officials from organizations external to the federal government involved in the homeless and housing sector. This included the Canadian Alliance for Ending Homelessness, the Federation of Canadian Municipalities, and the Assembly of First Nations.

We did not examine the following:

- National Housing Strategy programs that were not focused on housing for the most vulnerable Canadians

- federal programs and services related to homelessness that are not delivered by the departments and the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation

- programs and services delivered by provinces, municipalities, not‑for‑profit organizations, Indigenous organizations, and the private sector that do not receive funding and/or support from the departments and/or the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation

Criteria

We used the following criteria to determine whether Employment and Social Development Canada and Infrastructure Canada prevented and reduced chronic homelessness through interventions that helped those at risk of or experiencing homelessness obtain housing and supports needed to remain housed. We also used the following criteria to determine whether the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation contributed to the prevention and reduction of chronic homelessness by addressing the housing needs and improving housing outcomes for vulnerable Canadians.

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Employment and Social Development Canada and Infrastructure Canada collect information to measure the short-term and long-term progress in preventing and reducing chronic homelessness, adjust programs as appropriate, and publicly report the results achieved. Employment and Social Development Canada and Infrastructure Canada monitor recipient compliance with program-specific requirements, share information and analysis with recipients, and adjust programs as appropriate in support of preventing and reducing chronic homelessness. |

|

|

The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation collects information to measure the short-term and long-term progress in improving housing outcomes for vulnerable Canadians, adjust programs as appropriate, and publicly report the results achieved. The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation monitors recipient compliance with program-specific requirements, shares information and analysis with recipients, and adjusts programs as appropriate in support of improving housing outcomes for vulnerable Canadians. |

|

|

The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, Employment and Social Development Canada, and Infrastructure Canada collaborated and coordinated to prevent and reduce chronic homelessness and improve housing outcomes for vulnerable Canadians. Employment and Social Development Canada, Infrastructure Canada, and the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation collaborated and coordinated with other federal entities to prevent and reduce chronic homelessness and improve housing outcomes for vulnerable Canadians. The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, Employment and Social Development Canada, and Infrastructure Canada coordinated their approach to prevent and reduce chronic homelessness and improve housing outcomes for vulnerable Canadians with partners outside the federal government. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period from November 2017 to 31 March 2022. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies. However, to gain a more complete understanding of the subject matter of the audit, we also examined certain matters that preceded the start date of this period.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 21 October 2022, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

This audit was completed by a multidisciplinary team from across the Office of the Auditor General of Canada led by Casey Thomas, Assistant Auditor General, who had overall responsibility for audit quality, including conducting the audit in accordance with professional standards, applicable legal and regulatory requirements, and the office’s policies and system of quality management.

Recommendations and Responses

In the following table, the paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report.

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

5.45 Infrastructure Canada should

|

Infrastructure Canada’s response. Agreed. While the COVID‑19 pandemic required communities to shift their focus to pandemic response measures, impacting their ability to collect and report timely data and therefore the ability of the department to analyze and report up‑to‑date information, Infrastructure Canada recognizes the importance of emergency shelter and program data to support an understanding of homelessness and the extent to which the program is addressing needs. With respect to shelter data, in early 2022, the department began work to identify technological solutions to accelerate data availability. A work plan for implementing these solutions will be developed by 31 March 2023. The last phase of the new Reaching Home Results Reporting Online system is expected to be released in fall 2022. This will allow for timely collection and analysis of annual program results. To explain trends in homelessness through data collected by the department, as well as other data available, new research products will be released by 31 May 2023, including one that will review known structural factors that influence homelessness and an analysis of their relative contribution to observed changes in shelter use. All of these information sources will support the department in making adjustments to the program where and when needed. |

|

5.49 Infrastructure Canada should collaborate with designated communities and other partners to develop an action plan with timelines to address the barriers to the implementation of coordinated access that were identified in its analysis of community reporting. |

Infrastructure Canada’s response. Agreed. While the COVID‑19 pandemic required communities to shift their focus to pandemic response measures, impacting their ability to pursue the transformational change required to introduce coordinated access, Infrastructure Canada recognizes the importance of supporting the ongoing efforts of communities to implement and maintain this approach to service delivery. Subsequent to the period under audit, the department implemented the following measures:

Additionally, Infrastructure Canada will be working individually with all the communities that have not yet implemented coordinated access to help them achieve the requirements by 31 March 2023. |

|

5.62 The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation should assess the impact of its programs on vulnerable groups at all stages of its National Housing Strategy initiatives. The corporation’s efforts should include the following:

|

The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s response. Agreed. The National Housing Strategy is composed of a variety of initiatives that form a toolkit to support Canadians across the entire housing continuum, from those most in need to those wanting to buy their first home. Addressing the housing needs of vulnerable Canadians is one of 6 key priority areas for action of the National Housing Strategy which it works to accomplish across a variety of programs while also supporting investments in the housing system along the housing continuum, including market housing. Currently, National Housing Strategy programs that are designed to support those in need include operational procedures to prioritize projects that support National Housing Strategy vulnerable populations. Going forward, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation will further define and analyze the housing needs of vulnerable populations and measure how its programs are meeting these needs as well as define the successful result of its programs in prioritizing vulnerable populations by the end of December 2023. The corporation currently uses performance measures and administrative data to assess which vulnerable populations proponents intend to serve and are assisting through its programs. The corporation will work on strategies to access more comprehensive administrative data and report on information about those being housed in National Housing Strategy units by the end of December 2023 through its public reporting tools. In addition, to understand who is being assisted by the units generated through the National Housing Strategy and how their needs are being met, the corporation has initiated a record-linkage project in partnership with Statistics Canada. This project will provide demographic and outcome-based data on households being housed in National Housing Strategy units. This will allow the corporation to assess who is being assisted in units while respecting the privacy of occupants. The data will also be made available around mid‑2023 through the research data centres to promote and leverage external research capacity on housing. The corporation expects to have reporting on this available in late 2023. The corporation will report on its progress in achieving this commitment through its website as well as through the Triennial National Housing Strategy Report to Parliament, which is expected to be published in the 2023–24 fiscal year. The National Housing Strategy targets individuals across the housing continuum from those most in need to market rental and first-time home ownership. While this requires that programs target different thresholds of need and depths of affordability, the corporation will review and take the necessary steps to align how affordability is measured within its programs, as well as how affordability is reported for National Housing Strategy programs by the end of December 2023 with a goal of reflecting this in public reporting by the end of March 2024. |

|

5.74 The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation and Infrastructure Canada should

|

Response of each entity. Agreed. While federal efforts are only one component of addressing homelessness, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation and Infrastructure Canada recognize that preventing and reducing homelessness, including chronic homelessness, requires clear accountability, alignment of federal initiatives, and cross-jurisdictional support and efforts. While the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation is the lead and accountable for the National Housing Strategy as a whole, the corporation and Infrastructure Canada will work with central agencies by 31 December 2023 to clarify accountability for the achievement of the National Housing Strategy chronic homelessness target. In support of improved alignment, coordination, and integration on homelessness and chronic homelessness including prevention, subsequent to the initial audit period, the Assistant Deputy Minister–level committee between the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation and Infrastructure Canada was established to collaborate more formally on infrastructure, housing, and homelessness. Two additional interdepartmental committees will be struck in 2022–23: one across federal organizations to facilitate efforts on chronic homelessness; and the other with Veterans Affairs Canada to support the implementation of the new Veteran Homelessness Program. Beyond improving federal governance structures, by 31 December 2022, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation and Infrastructure Canada will develop a targeted awareness strategy to ensure that Reaching Home funding recipients can maximize opportunities available through other National Housing Strategy programs that could support their efforts to address homelessness. To promote the ongoing awareness of opportunities, Reaching Home funding recipients will be encouraged to integrate regional corporation staff into community-level planning around funding through existing structures such as community advisory boards. For cross-jurisdictional support and efforts, one mechanism that is used is the Federal, Provincial and Territorial Forum on Housing, which provides opportunities to discuss the implementation of the National Housing Strategy and assess its effectiveness. The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation is the co‑chair of the forum at the deputy and senior official levels and Infrastructure Canada is also represented. |