2023 Reports 1 to 5 of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the Parliament of CanadaReport 2—Follow-up on the Recovery of Species at Risk

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings

- Recommendation

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- Recommendation and Responses

- Exhibits:

- 2.1—Recovery planning and implementation reporting timelines under the Species at Risk Act

- 2.2—Federal organizations’ roles and responsibilities under the Species at Risk Act

- 2.3—Ten percent of recovery strategies and management plans were overdue (as of 31 December 2022)

- 2.4—Recovery strategies and management plans for 4 species were overdue by up to 17 years

- 2.5—For some wildlife species at risk, the implementation reports on their recovery strategies were several reporting cycles behind

Introduction

Background

2.1 The Species at Risk Act was designed as a key tool for conserving and protecting Canada’s biodiversity—the variety among living things. The act came fully into force in 2004 and supports federal commitments under the 1996 national Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk to prevent species in Canada from becoming extirpated (see next paragraph) or extinct as a result of human activity.

2.2 The act aims to protect wildlife species in Canada that are in any of the 4 categories of increasing risk:

- special concern (may become threatened or endangered)

- threatened (likely to become endangered if nothing is done to reverse the factors leading to its extirpation or extinction)

- endangered (faces imminent extirpation or extinction)

- extirpated (no longer exists in the wild in Canada but exists elsewhere in the wild)

2.3 The purposes of the act are to

- prevent wildlife species in Canada from becoming extinct or extirpated

- provide for the recovery of wildlife species that are extirpated, endangered, or threatened as a result of human activity

- manage wildlife species of special concern to prevent them from becoming endangered or threatened

2.4 The act requires that 4 key documents be prepared for the management and recovery of wildlife species at risk listed under the act:

- Recovery strategies. For all extirpated, endangered, and threatened wildlife species, the act requires recovery strategies. These documents include, among other things, recovery objectives (including population and distribution objectives), an identification of the species’ critical habitat to the extent possible, a general description of the research and management activities needed to meet the recovery objectives, and the identification of threats to the survival of the species and their critical habitat to the extent possible. If the recovery of a species is not feasible, the strategy must include a description of the species and its needs, an identification of the species’ critical habitat to the extent possible, and the reasons why its recovery is not feasible.

- Action plans. While the recovery strategy sets out the recovery objectives for a species, the related action plan or plans detail the proposed measures to be taken to protect the species’ critical habitat and to implement the recovery strategy, including those that address the threats to the species and those that help to achieve the population and distribution objectives. Examples of such measures are actions to address illegal harvesting and habitat restoration.

- Management plans. For any wildlife species listed as being of special concern, the act requires management plans, which identify conservation measures for the species and its habitat.

- Implementation reports. These reports provide information on the progress made toward achieving objectives set out in a species’ recovery strategy or management plan or the progress made toward implementing the measures proposed in an action plan.

2.5 To the extent possible, recovery strategies, action plans, and management plans are prepared in cooperation and consultation with provincial and territorial governments, wildlife management boards, Indigenous people and communities, and stakeholders. When preparing individual recovery strategies, action plans, and management plans, a multi-species or an ecosystem approach may be used.

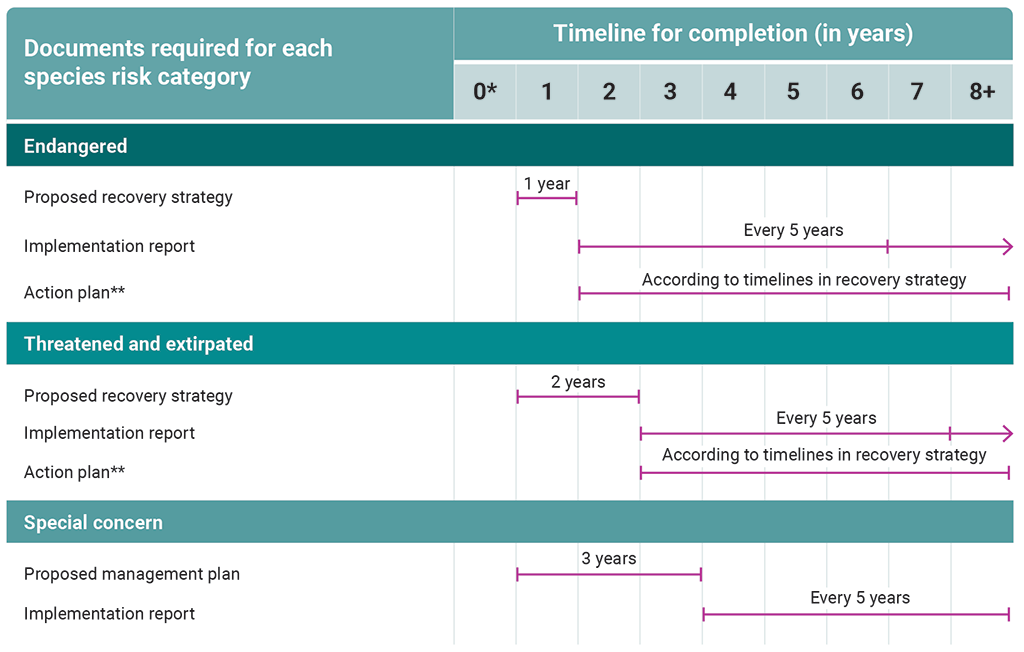

2.6 The act sets out timelines for completing these documents (Exhibit 2.1):

- Proposed recovery strategies must be posted on the Species at Risk Public Registry within 1 year of the wildlife species being listed as endangered or within 2 years of it being listed as threatened or extirpated. Once posted, recovery strategies are subject to a 60‑day comment period after which they must be finalized within 30 days.

- The recovery strategy indicates when 1 or more action plans will be completed.

- Proposed management plans must be posted on the Species at Risk Public Registry within 3 years of a wildlife species being listed as being of special concern. Once posted, management plans are subject to a 60‑day comment period after which they must be finalized within 30 days.

- Implementation reports must be produced within 5 years of the publication of the related recovery strategy or management plan and in every 5‑year period after that until the objectives of the strategy or plan have been met (or in the case of recovery strategies, the species’ recovery has been shown to be unfeasible). A report on the implementation of an action plan and its ecological and socio-economic impacts is required 5 years after the plan comes into effect.

Exhibit 2.1—Recovery planning and implementation reporting timelines under the Species at Risk Act

Source: Based on information from the Species at Risk Act

Exhibit 2.1—text version

These timelines are for completing proposed recovery strategies, actions plans, proposed management plans, and implementation reports under the Species at Risk Act.

For the endangered species risk category, the timelines for completing documents are as follows:

- The proposed recovery strategy must be completed within 1 year of the date when a species is listed in the Species at Risk Act, Schedule 1.

- The implementation report must be completed within 5 years of completing the proposed recovery strategy and in every 5‑year period after that.

- The action plan must be completed according to timelines in the recovery strategy as required by the act.

For the threatened and extirpated species risk categories, the timelines for completing documents are as follows:

- The proposed recovery strategy must be completed within 2 years of the date when a species is listed in the Species at Risk Act, Schedule 1.

- The implementation report must be completed within 5 years of completing the proposed recovery strategy and in every 5‑year period after that.

- The action plan must be completed according to timelines in the recovery strategy as required by the act.

For the special concern species risk category, the timelines for completing documents are as follows:

- The proposed management plan must be completed within 3 years of the date when a species is listed in the Species at Risk Act, Schedule 1.

- The implementation report must be completed within 5 years of completing the proposed recovery strategy and in every 5‑year period after that.

2.7 Canada has made commitments to counter biodiversity loss over 3 decades. In 1992, Canada ratified the United Nations’ Convention on Biological Diversity. This legally binding treaty recognizes that the global decline of biodiversity is one of the most serious environmental issues. Countries that signed the convention committed to conserving biological diversity, using the components of biological diversity sustainably, and sharing the benefits arising from the use of genetic resources fairly and equitably. The Species at Risk Act is a key tool in Canada’s response to the convention.

2.8 In 2015, as part of its commitment to the convention, Canada adopted a suite of 19 national targets, known as the 2020 Biodiversity Goals and Targets for Canada. These national targets cover issues ranging from species at risk to sustainable forestry to connecting Canadians to nature. In 2018, Environment and Climate Change Canada reported that, while Canada had made progress toward meeting its target for species at risk, that progress was too slow.

Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources

Source: United NationsFootnote 1

Sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, halt and reverse land degradation, halt biodiversity loss

Source: United Nations

2.9 The United Nations has recognized that an emergency faces the world’s biodiversity and that, despite ongoing efforts, biodiversity is deteriorating worldwide faster than ever. In December 2022, in response to the biodiversity crisis, Canada, along with other parties to the convention, further committed to fight biodiversity loss by agreeing on the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. The framework requires signatories to take urgent action to halt and reverse biodiversity loss and sets out 23 targets to be achieved by 2030. It includes a call for urgent actions to halt the extinctions of threatened species, to recover and conserve species, and to maintain and restore genetic diversity.

2.10 Planning for and reporting on the recovery of wildlife species at risk contributes to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, particularly Goal 14 (Life Below Water)—”Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources”—and Goal 15 (Life on Land), specifically target 15.5—”Take urgent and significant action to reduce the degradation of natural habitats, halt the loss of biodiversity and, by 2020, protect and prevent the extinction of threatened species.”

2.11 Canada’s commitments to biodiversity are further detailed in the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development’s October 2022 Biodiversity in Canada—Commitments and Trends backgrounder.

2.12 Environment and Climate Change Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and Parks Canada share responsibility for the implementation of the Species at Risk Act (Exhibit 2.2). These organizations are involved in a range of activities that occur over the 5 stages of the conservation cycle for species at risk: assessment, protection, recovery planning, implementation, and monitoring and evaluation. Successful recovery of wildlife species at risk depends not only on the federal government’s efforts but also on the contributions of provincial and territorial governments, Indigenous people and communities, industry, non‑government organizations, and others.

Exhibit 2.2—Federal organizations’ roles and responsibilities under the Species at Risk Act

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Fisheries and Oceans Canada | Parks Canada |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Source: Based on information from the Species at Risk Act, Environment and Climate Change Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and Parks Canada

Focus of the audit

2.13 This audit focused on whether Environment and Climate Change Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and Parks Canada met the timeline requirements of the Species at Risk Act specific to the development of recovery strategies, action plans, management plans, and related implementation reports. It also focused on whether objectives set out in the recovery strategies and management plans were being met. The audit included the analysis of individual wildlife species listed under Schedule 1 of the Species at Risk Act and whether as of 31 December 2022, recovery strategies, action plans, management plans, and implementation reports were created for these individual species within the timelines specified in the act.

2.14 The Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development has previously reported on the federal government’s planning and recovery actions for wildlife species at risk, in 2018. Progress made on observations from the 2018 report is included in this audit where appropriate.

2.15 This audit is important because the diversity of wildlife species continues to decline in Canada, and more wildlife species could become extinct, extirpated, endangered, or threatened soon if they are not adequately protected. Without consistent action to protect wildlife species—including developing and implementing recovery strategies, action plans, and management plans—the rate of their loss is expected to increase significantly.

2.16 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings

Progress toward meeting wildlife species recovery objectives was slow

2.17 This finding matters because the lack of progress toward meeting recovery objectives means that wildlife species at risk continue to face extirpation or extinction.

2.18 The government periodically reports on population trends for wildlife species at risk against the recovery and management objectives set out in the species’ recovery strategies and management plans, respectively.

2.19 When recovery is feasible, the recovery strategies include population and distribution objectives to assist the recovery and survival of the wildlife species at risk. These objectives can involve keeping a species stable, stopping the decline of a species, or increasing the populations of at‑risk species.

Uneven progress toward meeting population and distribution objectives

2.20 We found that population and distribution objectives were not being met for many species at risk for which population data was available. In addition, 17% (or 87) of the 520 species that had been reassessed had entered a higher risk category.

2.21 The January 2023 Canadian Environmental Sustainability Indicators: Species at Risk Population Trends report presented progress toward meeting population and distribution objectives for 144 of 640 wildlife species at risk for which trends could be determined. The report indicated that

- 64 (or 44%) of the 144 species did not show progress toward meeting their population and distribution objectives

- 62 (or 43%) of the 144 species showed progress toward meeting their population and distribution objectives

- 18 (or 13%) of the 144 species showed mixed evidence of both improvement and decline

2.22 The 2022 Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Report 9—Departmental Progress in Implementing Sustainable Development Strategies—Species at Risk reported that these trends indicated that the government was not on track to meet its target of having 60% of population trends for species at risk consistent with recovery and management objectives by 2025. The initial target, set out in the 2010–2013 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy, was to have population trends consistent with recovery strategy objectives for 100% of species listed as at risk by 2020.

2.23 Under the Species at Risk Act, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in CanadaDefinition 1 is responsible for assessing the status and classifying wildlife species that it considers to be at risk. The committee must also review wildlife species previously designated in a category of risk at least once every 10 years or at any time if it has reason to believe that the species’ status has changed significantly. The completed assessment of wildlife species must be submitted to the Minister of Environment and Climate Change and to the Canadian Endangered Species Conservation Council, which consists of the responsible federal ministers and their provincial and territorial counterparts.

2.24 As reported in the December 2022 Canadian Environmental Sustainability Indicators: Changes in the Status of Wildlife Species at Risk report, the committee reassessed 520 species that had been listed as at risk since 1982 and that had sufficient data available. The committee found that

- 329 (or 63%) of the 520 species showed no change in status

- 104 (or 20%) of the 520 species had entered a lower risk category

- 87 (or 17%) of the 520 species had entered a higher risk category

No change to a species’ risk status does not necessarily mean that its population or distribution has not changed. It means only that any change was not significant enough to change its risk category.

2.25 In general, conservation actions are expected, over time, to lead to a lower risk status for listed wildlife species. However, population trends reported by Environment and Climate Change Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada were affected by many factors, such as species’ lifespans, species’ reproductive cycles, and expectations on species’ recovery timelines. For example, longer-lived species, such as the north Pacific right whale, might not show signs of recovery for many years. Furthermore, according to Environment and Climate Change Canada, changes in apparent risk level, both improving or worsening, can result from improved information, such as the discovery of additional populations of a species than was previously known, in addition to the result of actual changes in the condition of the known species population. Finally, in some cases, the risk status of some species may never change, even with conservation actions (for example, for rare or isolated species).

Documents that were needed to help species recover were not in place for many wildlife species at risk

2.26 This finding matters because recovery strategies and related action plans set out what must be done to stop or reverse the decline of a wildlife species that has been assessed as threatened, endangered, or extirpated in Canada. Management plans are important because they set out what must be done to maintain the population of a wildlife species of special concern and prevent it from becoming more at risk. Recovery strategies, action plans, and management plans are the building blocks for species’ recovery.

2.27 The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada determines the conservation status of Canadian wildlife species suspected of being at risk. As of December 2022, the committee had identified 866 wildlife species at risk. It planned to assess and reassess an additional 89 species by November 2024.

2.28 The Governor in Council,Definition 2 on the recommendation of the Minister of the Environment, decides which of the wildlife species that the committee has assessed as being at risk should be listed under the Species at Risk Act (under Schedule 1). For aquatic species, Fisheries and Oceans Canada and its minister also advise on the Minister of the Environment’s recommendation for listings. As of December 2022, 640 wildlife species had been listed under the act. The Governor in Council’s listing decisions were pending for 152 at‑risk species, including important pollinators, such as the 2 subspecies of the western bumble bee (assessed in 2014 by the committee as being of special concern and as threatened). If the Governor in Council were to list all of the identified wildlife species, the number of listed wildlife species would increase by more than 20%. Once any of these wildlife species are listed under the act, recovery strategies or management plans would have to be produced in accordance with the legislated timelines. Status reclassification was also pending for 23 at‑risk wildlife species.

2.29 Once a wildlife species is listed as threatened, endangered, or extirpated under the act, the species’ critical habitat must be identified in its recovery strategy to the extent possible using available information. The act defines critical habitat as “the habitat that is necessary for the survival or recovery of a listed wildlife species.” Critical habitat would need to be identified for extirpated species only if reintroduction to Canada is recommended. Critical habitat—and examples of activities likely to destroy it—is identified to the extent possible in the final recovery strategy or action plan. If the available information on critical habitat is inadequate, a schedule of related studies to identify critical habitat is also required.

Missing recovery strategies and management plans

2.30 We found that 10% (or 61) of the 627 species listed as extirpated, endangered, threatened, or of special concern did not have recovery strategies or management plans in place as required by the act (Exhibit 2.3). Overall, recovery strategies were overdue for 36 species, and management plans were overdue for 25 species. In terms of published documents, 566 species had a recovery strategy or a management plan published on the Species at Risk Public Registry by the 3 organizations.

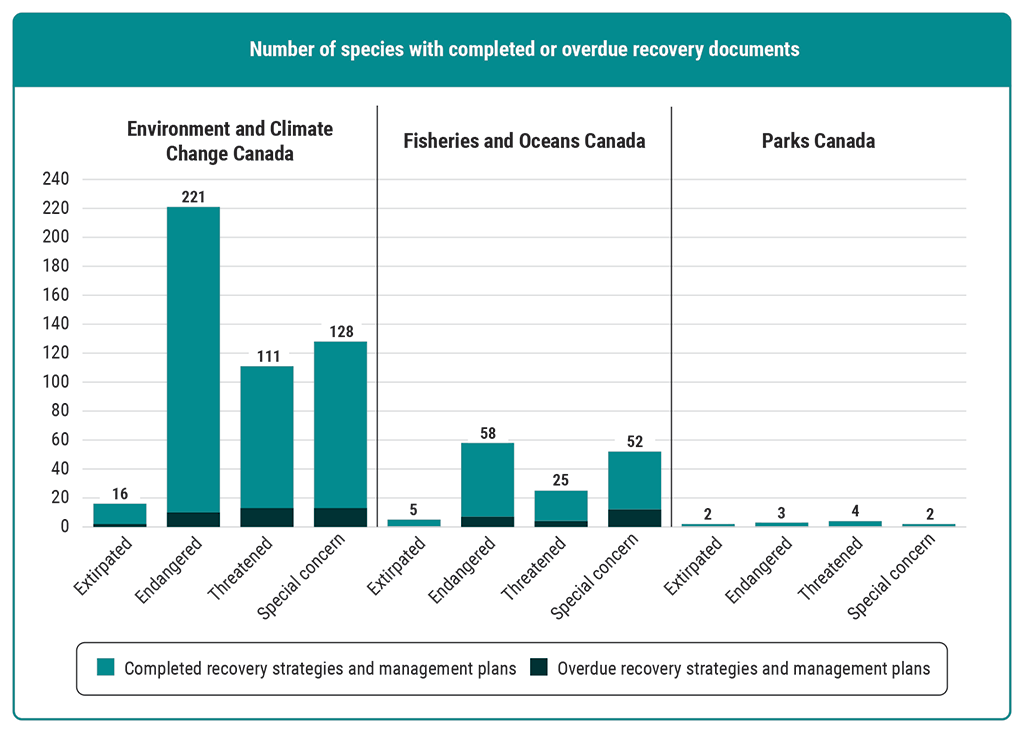

Exhibit 2.3—Ten percent of recovery strategies and management plans were overdue (as of 31 December 2022)

Source: Based on data provided by Environment and Climate Change Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and Parks Canada

Exhibit 2.3—text version

This bar chart shows the number of species for which Environment and Climate Change Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and Parks Canada had completed or overdue recovery documents as of 31 December 2022. Overall, 10% (or 61) of the 627 species listed as extirpated, endangered, threatened, or of special concern had overdue recovery strategies and management plans.

Of the 3 organizations, Environment and Climate Change Canada had the highest number of completed or overdue recovery documents. The department’s numbers are as follows:

- Environment and Climate Change Canada had completed or overdue recovery documents for 16 extirpated species. Specifically, recovery strategies and management plans were completed for 14 extirpated species and were overdue for 2 extirpated species.

- Environment and Climate Change Canada had completed or overdue recovery documents for 221 endangered species. Specifically, recovery strategies and management plans were completed for 211 endangered species and were overdue for 10 endangered species.

- Environment and Climate Change Canada had completed or overdue recovery documents for 111 threatened species. Specifically, recovery strategies and management plans were completed for 98 threatened species and were overdue for 13 threatened species.

- Environment and Climate Change Canada had completed or overdue recovery documents for 128 species of special concern. Specifically, recovery strategies and management plans were completed for 115 species of special concern and were overdue for 13 species of special concern.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada had the next highest number of completed or overdue recovery documents. The department’s numbers are as follows:

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada had completed recovery strategies and management plans for 5 extirpated species. The department had no overdue recovery documents for extirpated species.

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada had completed or overdue recovery documents for 58 endangered species. Specifically, recovery strategies and management plans were completed for 51 endangered species and were overdue for 7 endangered species.

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada had completed or overdue recovery documents for 25 threatened species. Specifically, recovery strategies and management plans were completed for 21 threatened species and were overdue for 4 threatened species.

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada had completed or overdue recovery documents for 52 species of special concern. Specifically, recovery strategies and management plans were completed for 40 species of special concern and were overdue for 12 species of special concern.

Parks Canada had the lowest number of completed recovery documents and no overdue documents. The agency had completed recovery strategies and management plans for 2 extirpated species, 3 endangered species, 4 threatened species, and 2 species of special concern.

2.31 We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada did not have a recovery strategy or management plan for 38 of the wildlife species at risk that it was responsible for. Fisheries and Oceans Canada did not have a recovery strategy or management plan in place for 23 of the wildlife species that it was responsible for. Parks Canada had completed all of its required recovery strategies and management plans.

2.32 We found that recovery strategies and management plans were overdue by less than a year to up to 17 years. Of the 61 species for which a recovery strategy or a management plan was overdue, 4 were more than 10 years late (Exhibit 2.4). On average, overdue recovery strategies and management plans were 3 years overdue.

Exhibit 2.4—Recovery strategies and management plans for 4 species were overdue by up to 17 years

| Species | Risk status | Years overdue |

|---|---|---|

| Western screech‑owl (macfarlanei subspecies). There are about 300 to 500 of these medium-sized birds in Canada. Recent reports show that it has a wider geographic range than previously thought. | Threatened | 17 |

| Greater prairie-chicken. This grassland bird was formerly found in parts of Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Ontario but has not been observed in Canada since 1987. | Extirpated | 16 |

| Alkaline wing-nerved moss. This moss is found mostly in western Canada and is at risk globally. Some of its known sites have been lost to urbanization. | Threatened | 14 |

| White shark (Atlantic population). This top predator is protected in many countries. The only documented threat in Atlantic Canada is being caught as bycatch in commercial fishing. | Endangered | 11 |

Source: Based on the Species at Risk Public Registry and data provided by Environment and Climate Change Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada

2.33 We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada had made progress in completing overdue recovery strategies and management plans since 2018. In the 2018 Spring Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Report 3—Conserving Biodiversity, we found that the 3 organizations had not completed overdue recovery strategies and management plans for 25 wildlife species at risk. Since then, 18 of those 25 overdue recovery strategies and management plans had been completed—13 by Environment and Climate Change Canada and 5 by Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

Missing action plans

2.34 The Species at Risk Act requires that action plans be prepared to support the implementation of recovery strategies. We found that the 3 organizations had not produced 146 (or 57%) of the required 257 action plans. Environment and Climate Change Canada was responsible for 138 of the 146 overdue action plans (including 33 for species transferred from Parks Canada in 2021), Fisheries and Oceans Canada was responsible for 8 of them, and Parks Canada had none.

2.35 The 3 organizations have been preparing multi-species action plans. These plans can allow for conservation measures that can address the needs of multiple wildlife species at risk at the same time with existing resources. The use of multi-species action plans can also create efficiencies by reducing the number of recovery documents and implementation reports that need to be published. We found that 37 multi-species action plans had been produced (5 by Environment and Climate Change Canada, 9 by Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and 23 by Parks Canada for the protected heritage areas it administers).

2.36 In our view, expanding the use of multi-species plans, where appropriate to do so, could help the responsible federal organizations meet their legislated timelines by addressing action plan requirements for multiple species at once while responsibly using available resources. Using ecosystem plans could have the same benefits.

Missing identification of critical habitat

2.37 We found that 20% (or 82) of the 409 recovery strategies that had been produced for extirpated, endangered, and threatened wildlife species did not identify the species’ critical habitat. These include 64 strategies by Environment and Climate Change Canada, 17 strategies by Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and 1 strategy by Parks Canada. Identifying critical habitat, when sufficient information is available, allows appropriate measures to be taken to protect or restore it—and, in turn, the wildlife species that depend on it. Identifying critical habitat can be challenging, particularly if data about species’ habitat needs and preferences is scarce—which can be the case for rare, hard‑to‑find, or little-studied species where little is known about their actual locations. The lack of information on a species’ location and habitat needs affects the ability to identify where and how much critical habitat this species needs to support achieving its population and distribution objectives.

2.38 Provinces and territories collect and maintain information on certain wildlife species at risk. Environment and Climate Change Canada has indicated that to identify critical habitat, it relies on occurrence and location data on terrestrial species from provinces, territories, and Indigenous groups and communities under established data-sharing agreements. Those agreements do not always allow the department to disclose the location of critical habitat in a recovery strategy for a variety of reasons.

2.39 There may be sensitivities about sharing information for the purposes of including it in a recovery strategy or action plan. For example, publishing information on critical habitat could lead to actions that cause unintended or unwanted effects on a wildlife species, such as poaching. We noted that Environment and Climate Change Canada was developing a policy to define sensitive information applicable to critical habitat and how best to share this information without jeopardizing the recovery and survival of the wildlife species.

Most reports on the implementation of actions to recover wildlife species at risk were overdue

2.40 This finding matters because implementation reports point to what progress has been made toward meeting wildlife species’ population and distribution objectives. This can include actions to protect or recover a wildlife species and its critical habitat and steps being taken to mitigate threats to a wildlife species. Implementation reports also help to hold the responsible minister accountable for the actions being taken to manage wildlife species at risk and to help them recover.

Delayed implementation reports

2.41 We found that there were large backlogs in completing implementation reports, including the initial and subsequent 5‑year reports on progress for individual species’ recovery strategies and management plans and the 5‑year report on progress for action plans.

2.42 Environment and Climate Change Canada had not completed 398 (or 99.7%) of the 399 required implementation reports. This included implementation reports for the species that Parks Canada had transferred to Environment and Climate Change Canada. The department was assessing what was required to report on these species, including considering the previous work conducted by Parks Canada, which was responsible for implementation reporting on these species prior to their transfer.

2.43 Fisheries and Oceans Canada produced 93 implementation reports, some of which covered more than the 5 years required by the act. It had yet to complete 108 (or 54%) of the 201 required implementation reports. The department indicated that it had an approach to addressing its backlog, which includes producing reports that cover a period longer than 5 years, allowing it to address its overdue reporting obligations efficiently.

Pink sand-verbena

Source: Sundry Photography/Shutterstock.com

2.44 Parks Canada published 7 reports on the implementation of the recovery strategies for 6 wildlife species at risk that it was the lead for and 4 reports on related action plans. Six of the 7 reports on the implementation of recovery strategies were published after the 5‑year period required by the act. However, each report covered the period from the original posting of the recovery strategy. For 2 species—the Banff Springs snail and the pink sand-verbena—the implementation report covered 10 years, or 2 reporting periods. It also produced 18 implementation reports for multi-species action plans for specific protected heritage sites.

2.45 Environment and Climate Change Canada was 3 report cycles behind for 31 implementation reports on recovery strategies and management plans and 2 report cycles behind for 67 implementation reports. Fisheries and Oceans Canada was 3 report cycles behind for 1 species and 2 report cycles behind for 18 species. Some of the wildlife species that have implementation reports that are overdue by more than 1 reporting cycle are described in Exhibit 2.5.

Exhibit 2.5—For some wildlife species at risk, the implementation reports on their recovery strategies were several reporting cycles behind

| Species | Risk status | Number of reporting cycles overdue |

|---|---|---|

| Barrens willow. The shoreline habitat of this woody shrub is threatened by erosion and salt spray, while human activity has degraded its habitat elsewhere. | Endangered | 3 |

| Horsetail spike-rush. This perennial plant of the sedge family occupies shallow waters and pond shorelines. Activities by beavers, affecting the water levels, may be disrupting this plant’s habitat. | Endangered | 3 |

| Kirtland’s warbler. This medium-sized songbird depends strongly on young jack pines, which were originally maintained by natural fires and now largely by human intervention. | Endangered | 3 |

| North Pacific right whale. There may be fewer than 100 of these large baleen whales left. Long lifespans and low reproductive rates mean that recovery will take decades at least. | Endangered | 2 |

Source: Based on the Species at Risk Public Registry and data provided by Environment and Climate Change Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada

2.46 In the 2018 Spring Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Report 3—Conserving Biodiversity, we found that combined, the 3 responsible organizations had not completed 171 (or 78%) of the 218 required implementation reports. At the time of this audit, we found that Parks Canada had completed all of its overdue implementation reports and that Fisheries and Oceans Canada made progress in completing overdue implementation reports, with only 5 remaining. Environment and Climate Change Canada had 142 overdue implementation reports in 2018 and had not produced any reports since then.

Insufficient resources for preparing implementation reports

2.47 Collaboration and consultation with multiple partners and stakeholders are undertaken when preparing recovery strategies, action plans, management plans, and implementation reports, but it can be complex and time-consuming. Officials from the 3 organizations attributed some delays in the completion of recovery documents and related implementation reporting to the need to undertake meaningful consultations and collaboration with multiple partners. This is especially the case for species that have ranges that cover large geographical areas and multiple jurisdictions. Limited internal capacity to do recovery planning and reporting, along with competing priorities, were also cited as factors.

2.48 According to department officials, the lack of resources contributed to Environment and Climate Change Canada not meeting the legislated timelines for the completion of implementation reports. The department had focused on completing recovery strategies and management plans while assigning very few resources to completing implementation reports.

2.49 We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada was taking steps to make the production of recovery strategies and management plans more efficient. For example, the department uses provincial recovery strategies if the strategy meets the requirements of the Species at Risk Act. If information that was not required at the provincial level was required by the act, the department would add this information to the recovery document. We also found that Environment and Climate Change Canada had developed criteria to assist with prioritizing its recovery planning. This included considering legal timelines and internal capacity, as well as prioritizing resources and capacity for work with the highest potential conservation gains.

2.50 We also found that Fisheries and Oceans Canada had taken steps to improve the efficiency of its planning processes. The department developed a prioritization decision tree for reviewing and approving recovery strategies, action plans, management plans, and implementation reports. Although the document was yet to be approved, it clearly outlined prioritization criteria and document ranking, with the aim of producing recovery documents more efficiently. We also found that the department tracked overdue reports and had prepared a schedule for completing them. The department indicated that it was developing a policy guide (the Framework for Aquatic Species at Risk Conservation) to transition to applying multi-species approaches where it makes sense to do so.

Recommendation

2.51 As reported in this audit, most but not all species at risk have a published recovery strategy or management plan. However, there were and continue to be significant backlogs in producing action plans and reports on the implementation of recovery documents and progress toward meeting their objectives. These documents are important for implementing recovery strategies—and for understanding how well recovery measures are working—and can inform decisions on what more must be done to help with the survival and recovery of a wildlife species at risk. These are also essential to meeting Canada’s international commitments, including the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals.

2.52 To ensure that the organizations have the required tools in place to support and report on the recovery of all wildlife species at risk, Environment and Climate Change Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada, in collaboration with Parks Canada, should

- determine the time frame and resources that would be required to complete the backlog of outstanding recovery strategies, action plans, management plans, and related implementation reports for wildlife species at risk for which they are responsible

- periodically report publicly on the recovery strategies, action plans, management plans, and implementation reports completed; on those remaining to be done; and on compliance with the planning and reporting requirements of the Species at Risk Act

- continue to seek efficiencies, such as using multi-species or ecosystem plans and implementation reports where it makes sense to do so

Response of each entity. Agreed.

See Recommendation and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Conclusion

2.53 We concluded that the objectives set out by Environment and Climate Change Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and Parks Canada in recovery strategies and management plans for wildlife species at risk were not on track to be met. The January 2023 Canadian Environmental Sustainability Indicators: Species at Risk Population Trends report indicated that 44% of 144 wildlife species at risk for which trends could be determined did not show progress toward meeting their recovery objectives. Meanwhile, as reported in the December 2022 Canadian Environmental Sustainability Indicators: Changes in the Status of Wildlife Species at Risk report, 80% of the wildlife species at risk that had been reassessed since 1982 either showed no change in status or had entered a higher risk category. Stronger action is needed to help recover Canada’s species at risk and meet Canada’s commitments to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030.

2.54 We concluded that Environment and Climate Change Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada did not always meet the timelines required in the federal Species at Risk Act specific to the development of recovery strategies, action plans, management plans, and related implementation reports. In addition to fulfilling the requirements of the act, these documents are important for helping to protect and recover wildlife species at risk in Canada. Parks Canada had produced the recovery strategies, action plans, management plans, and related implementation reports for the wildlife species at risk for which it was responsible.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on whether Environment and Climate Change Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and Parks Canada complied with the timeline requirements of the Species at Risk Act specific to the development of recovery strategies, action plans, management plans, and related implementation reports and whether objectives set out in recovery strategies and management plans were being met. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs and to conclude on whether Environment and Climate Change Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and Parks Canada complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements, set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada applies the Canadian Standard on Quality Management 1—Quality Management for Firms That Perform Audits or Reviews of Financial Statements, or Other Assurance or Related Services Engagements. This standard requires our office to design, implement, and operate a system of quality management, including policies or procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether Environment and Climate Change Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and Parks Canada were meeting the timeline requirements of the federal Species at Risk Act specific to the development of recovery strategies, action plans, management plans, and related implementation reports and whether they were meeting the objectives set out in the recovery strategies and management plans.

Scope and approach

In our approach for this audit, we

- interviewed department and agency officials to update our understanding of the Species at Risk Act recovery planning, implementation, and monitoring and evaluation processes, including identifying root causes and barriers in completing the recovery strategies and action plans (which involved the identification of critical habitat), as well as management plans and implementation reports, as required by the act

- interviewed department and agency officials to identify root causes and barriers in meeting the objectives set out in the recovery strategies and management plans

- reviewed and analyzed supporting documentation, provided by the organizations, that tracks completion of recovery strategies, action plans, management plans, and implementation reports

We assessed whether recovery strategies and action plans identified critical habitat. However, we did not audit the quality of the information pertaining to critical habitat.

Unless otherwise noted, our analysis of the compliance with the timelines outlined in the Species at Risk Act is up to 31 December 2022.

Criteria

We used the following criteria to conclude against our audit objective:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Environment and Climate Change Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and Parks Canada report progress in meeting the objectives set out in the recovery strategies and management plans. |

|

|

Environment and Climate Change Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and Parks Canada complete the recovery strategies or management plans in accordance with the timelines set out in the federal Species at Risk Act. |

|

|

Critical habitat is identified for threatened species, endangered species, and extirpated species. |

|

|

Environment and Climate Change Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and Parks Canada prepare action plans based on the recovery strategies. |

|

|

Environment and Climate Change Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and Parks Canada complete implementation reports in accordance with the timelines set out in the federal Species at Risk Act. |

|

|

Environment and Climate Change Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada completed overdue recovery strategies or management plans that were reported in the 2018 Spring Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Report 3—Conserving Biodiversity. |

|

|

Environment and Climate Change Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and Parks Canada completed overdue progress reports that were reported in the 2018 Spring Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Report 3—Conserving Biodiversity. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period from 1 January 2018 to 31 December 2022. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 17 February 2023, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

This audit was completed by a multidisciplinary team from across the Office of the Auditor General of Canada led by James McKenzie, Principal. The principal has overall responsibility for audit quality, including conducting the audit in accordance with professional standards, applicable legal and regulatory requirements, and the office’s policies and system of quality management.

Recommendation and Responses

In the following table, the paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report.

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

2.52 To ensure that the organizations have the required tools in place to support and report on the recovery of all wildlife species at risk, Environment and Climate Change Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada, in collaboration with Parks Canada, should

|

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. Environment and Climate Change Canada will continue to deliver on obligations under the Species at Risk Act by publishing recovery strategies and management plans. By 31 December 2024, the department will develop a plan indicating the time frames and resources required to advance the completion of recovery strategies, management plans, and action plans and publish implementation reports. The department will continue to explore options for multi-species and place-based approaches for recovery planning and action planning, and will consider this as appropriate for implementation reporting. Environment and Climate Change Canada will build the plan to prioritize actions that have the greatest potential conservation outcome, and that will respect the need for meaningful collaboration and engagement with Indigenous communities and groups, stakeholders and other partners. Environment and Climate Change Canada, in collaboration with Fisheries and Oceans Canada and Parks Canada, will periodically report on compliance with the obligations related to recovery planning and reporting under the Species at Risk Act. Implementation date: 31 December 2024 Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response. Agreed. Fisheries and Oceans Canada will continue to make progress in the development of recovery strategies, action plans, management plans, and progress reports for listed aquatic species. The department will determine what is required to complete outstanding recovery documents and progress reports per its legislated obligations under the Species at Risk Act, providing periodic public reports and using multi-species or ecosystem plans and implementation reports when it makes sense to do so. Parks Canada’s response. Agreed. Parks Canada will continue to collaborate with Environment and Climate Change Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada, where Parks Canada is also a competent authority for a species, to deliver on obligations under the Species at Risk Act by determining the resources required to contribute to the completion of recovery strategies, management plans, action plans and implementation reports for these species. In addition, Parks Canada will continue to lead on the completion of recovery documents for species that occur primarily on the lands and waters it administers. Parks Canada will also continue to develop and implement multispecies action plans for species under its authority. |