2023 Reports 1 to 5 of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the Parliament of CanadaReport 4—Supervision of Climate-Related Financial Risks—Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings and Recommendations

- The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada did not view its role as including the advancement of the government’s broader climate goals

- OSFI’s plans to address climate-related financial risks were headed in the right direction, but a full implementation is still years away

- It was unclear how climate-related financial risks would be incorporated into OSFI’s supervisory framework

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- Recommendations and Responses

- Exhibits:

- 4.1—Insured losses from catastrophic weather events in Canada

- 4.2—The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada regulates and supervises hundreds of financial institutions

- 4.3—Key responsibilities of designated entities under the Federal Sustainable Development Act

- 4.4—Examples of how the 2 types of climate-related financial risks can affect the economy and financial system

- 4.5—The United Kingdom’s Prudential Regulation Authority engaged stakeholders early and openly in climate-related financial risks

Introduction

Background

4.1 Climate change poses risks to individual financial institutions and the broader financial system. Climate-related financial risks can seriously affect the operations of financial institutions and, more importantly, the value of their assets and liabilities. For example, forest fires could lead to serious property damage and reduce households’ ability to repay mortgage loans, which would increase losses for financial institutions. Similarly, changes in government regulations and policies, introduced to limit greenhouse gas emissions, could lower companies’ revenues, reducing their capacity to repay creditors.

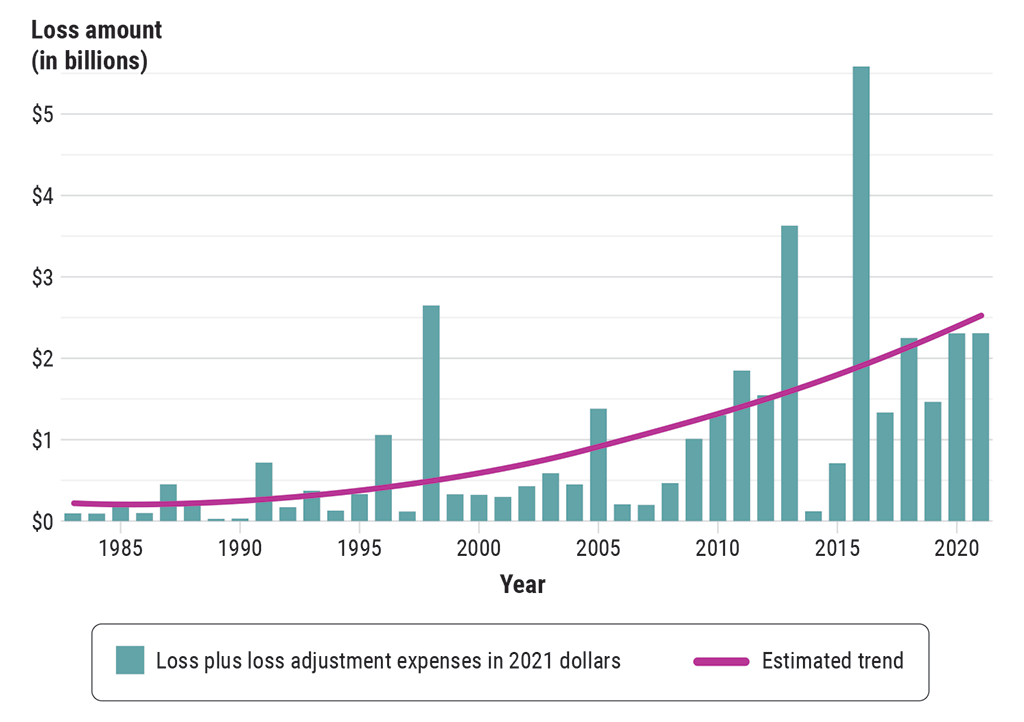

4.2 Catastrophic climate events, such as forest fires, floods, and landslides, are happening more frequently and with increased severity. The costs of these events—for example, insured losses (Exhibit 4.1)—are also quickly rising but are not yet significant enough to threaten the viability of Canada’s businesses, including financial institutions. As a result, many private sector businesses are not yet economically incentivized to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions or identify their exposure to climate-related financial risks, report on it, and develop practical strategies to manage it. This means that businesses, including financial institutions, could end up seriously unprepared as climate disasters increase in frequency and magnitude.

Exhibit 4.1—Insured losses from catastrophic weather events in CanadaNote *

Exhibit 4.1—text version

This bar chart shows the amount of insured losses from catastrophic weather events in Canada from 1983 to 2021. A catastrophic loss is 1 event costing $25 million or more. The estimated trend for these losses is a steady increase from 1983 to 2021.

The loss plus loss adjustment expenses by year in billions of 2021 dollars is as follows.

| Year | Loss plus loss adjustment expenses in billions of 2021 dollars |

|---|---|

| 1983 | $0.09 billion |

| 1984 | $0.09 billion |

| 1985 | $0.23 billion |

| 1986 | $0.10 billion |

| 1987 | $0.45 billion |

| 1988 | $0.22 billion |

| 1989 | $0.03 billion |

| 1990 | $0.03 billion |

| 1991 | $0.72 billion |

| 1992 | $0.17 billion |

| 1993 | $0.37 billion |

| 1994 | $0.13 billion |

| 1995 | $0.33 billion |

| 1996 | $1.06 billion |

| 1997 | $0.12 billion |

| 1998 | $2.65 billion |

| 1999 | $0.33 billion |

| 2000 | $0.32 billion |

| 2001 | $0.30 billion |

| 2002 | $0.43 billion |

| 2003 | $0.59 billion |

| 2004 | $0.45 billion |

| 2005 | $1.38 billion |

| 2006 | $0.20 billion |

| 2007 | $0.20 billion |

| 2008 | $0.47 billion |

| 2009 | $1.01 billion |

| 2010 | $1.30 billion |

| 2011 | $1.85 billion |

| 2012 | $1.55 billion |

| 2013 | $3.63 billion |

| 2014 | $0.12 billion |

| 2015 | $0.71 billion |

| 2016 | $5.58 billion |

| 2017 | $1.33 billion |

| 2018 | $2.25 billion |

| 2019 | $1.46 billion |

| 2020 | $2.31 billion |

| 2021 | $2.31 billion |

Source: Adapted from 2022 Facts of the Property and Casualty Insurance Industry in Canada, Insurance Bureau of Canada

4.3 The international community of financial supervisors—government agencies that regulate and oversee financial institutions, such as banks, insurers, and pension plans—recognizes that climate change poses risks to individual financial institutions and broader financial stability. As climate-related financial risks grow, financial supervisors, such as the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada (OSFI), need to update their supervisory frameworksDefinition 1 to take full account of these risks in order to achieve financial stability.

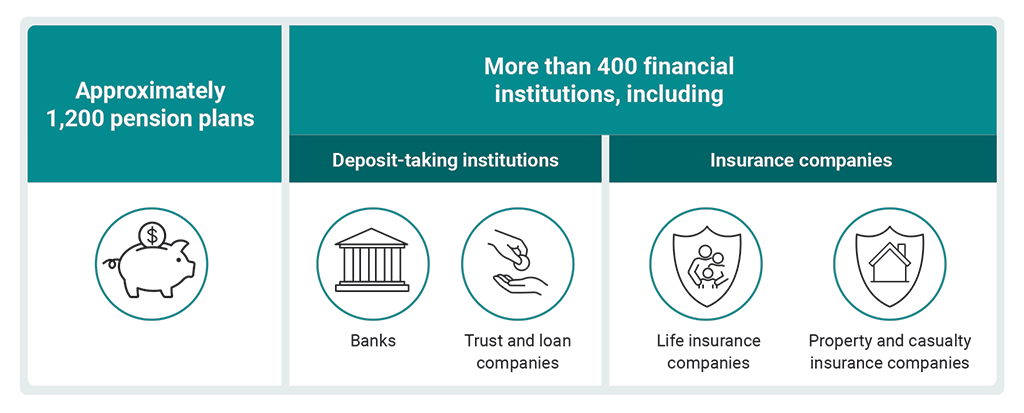

4.4 At the federal level, the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada is a key supervisor of financial institutions, regulating and supervising more than 400 financial institutions and approximately 1,200 pension plans (Exhibit 4.2). OSFI was established as an independent agency under the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Act and reports to Parliament through the Minister of Finance.

Exhibit 4.2—The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada regulates and supervises hundreds of financial institutions

Exhibit 4.2—text version

This diagram shows the number of pension plans and financial institutions that the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada regulates and supervises. There are approximately 1,200 pension plans and more than 400 financial institutions. The more than 400 financial institutions include not only deposit‑taking institutions, such as banks and trust and loan companies, but also insurance companies, such as life insurance companies and property and casualty insurance companies.

4.5 Importantly, OSFI is responsible for overseeing Canada’s 6 largest private sector banks, which are central to Canada’s payment and financial system. Two of these banks are also designated as globally systematically important financial institutions by the Financial Stability Board, which is an international body that fosters the development and promotes the implementation of effective regulatory, supervisory, and other financial sector policies. These 2 banks are deemed so important because their failure could trigger a wider financial crisis and threaten the global economy. This, in turn, makes OSFI central to maintaining public confidence not only in Canada’s financial system, but in the international financial system as well.

4.6 In Canada, as in many other countries, financial supervision responsibilities are shared among various entities, both federal and provincial, public and private. Each entity has its own mandate, responsibilities, and associated authorities, with as little overlap as possible. Cooperation among them is encouraged.

4.7 At the federal level, the entities involved in the oversight of Canada’s financial system, in addition to OSFI, are

- the Minister of Finance, who is supported by the Department of Finance Canada and has broad responsibility for all matters related to the financial sector and authority for federal financial sector legislation, including the governing legislation for each of the federal financial sector oversight agencies

- the Bank of Canada, which oversees critical financial market infrastructures, notably payment systems, and provides liquidity to the financial system

- the Financial Consumer Agency of Canada, which oversees the conduct of banking business

- the Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation, which provides deposit protection for depositors and handles, if required, the failure of member institutions

4.8 OSFI is Canada’s prudential supervisor. Prudential supervision is a process of oversight designed to promote the financial institutions’ adoption of rules and practices that contribute to the safety and soundness of the financial system and, in turn, public confidence in it. Prudential supervision involves

- identifying and assessing potential risks to the business model of a financial institution

- ensuring that the management of the financial institution has the appropriate competence and tools to manage those risks

- intervening in a timely fashion, using relevant powers if appropriate

4.9 OSFI bases the level of its prudential supervision of a given financial institution on the nature, size, complexity, and risk profileDefinition 2 of that institution and on what might happen if the institution were to fail. Ultimately, OSFI aims to safeguard depositors and insurance policyholders from loss by restraining excessive risk taking by financial institutions.

4.10 OSFI’s prudential supervision constantly responds to changes in the industry. OSFI manages emerging risks by issuing new guidelines, modifying existing guidelines, issuing advisories that clarify guidelines or inform about growing risks, collecting data from supervised institutions, and performing analysis.

4.11 OSFI’s guidelines and advisories do not have the force of regulation; however, they form the basis of the supervisory framework that OSFI uses to oversee financial institutions. The framework is based on international best practices, notably

- the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision’s Core Principles for Effective Banking Supervision

- the International Association of Insurance Supervisors’ Insurance Core Principles and methodology

Focus of the audit

4.12 This audit examined whether the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada (OSFI), according to its roles and responsibilities, incorporated climate-related financial risks into its risk management systems and frameworks of federally regulated financial institutions and federally regulated pension plans, to contribute to public confidence in the Canadian financial system.

4.13 This audit is important because climate change poses significant risks to the safety and soundness of Canada’s financial system. OSFI is central to maintaining public confidence not only in the Canadian financial system, but also in the global financial system. As such, OSFI ought to be at the forefront of international prudential supervisors when addressing climate-related financial risks. Furthermore, appropriate consideration of climate-related financial risks in prudential supervision could support the Government of Canada’s goal of achieving net‑zero emissions by 2050. As we have reported in many recent performance audits and in our 2021 report Lessons Learned from Canada’s Record on Climate Change, Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions have risen since 1990 despite decades of commitments to reduce them.

4.14 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings and Recommendations

The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada did not view its role as including the advancement of the government’s broader climate goals

4.15 This finding matters because the government strategy to achieve its environmental and sustainable development goals, including reducing greenhouse gas emissions, involves a whole‑of‑government approach where all federal entities are expected to contribute.

4.16 Financial supervisors’ primary role is to promote the stability of, and confidence in, the financial system. Internationally, however, there is debate about how that role applies to tackling the consequences of climate change. Some argue that financial supervisors ought to act only to ensure that financial markets can continue to operate normally when significant climate-related financial risks arise. Others argue that financial supervisors ought to support national commitments to transition away from carbon-intensive industries, such as oil and gas, because a low‑carbon economy would ultimately support long‑term financial stability. A consensus has yet to emerge.

4.17 Some governments have aligned financial supervisors’ mandates with sustainability objectives, including

- the United Kingdom’s Prudential Regulation Authority, which has a mandate to support an orderly economy-wide transition to net‑zero emissions

- the European Central Bank, which considers itself obliged to support general economic policies in the European Union, including the transition to a net‑zero economy and to protecting the environment

In both cases, it is worth noting that the enabling legislation of these prudential supervisors includes a secondary objective of supporting the general economic policy of the government when such support does not prejudice their primary objective. Such a secondary objective does not exist in the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Act.

4.18 In the United States, on the other hand, the Financial Stability Oversight Council considers that its only role is to promote financial stability. Nevertheless, the council recognizes that if financial institutions take into account climate-related financial risks, this could encourage investments toward a lower-emission future.

4.19 The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada (OSFI) acknowledges that climate-related financial risks can create financial challenges for the entities it supervises and should therefore be considered as part of its prudential mandate. OSFI officials told us that its current mandate allows it to take action to ensure that the financial institutions it regulates are managing how climate change affects their safety and soundness. However, OSFI officials told us that advancing national sustainability goals (for example, by actively encouraging the transition to a net‑zero economy) would exceed OSFI’s long-standing approach to implementing its legal mandate.

4.20 Although OSFI’s mandate has not changed, the Canadian legal landscape has, specifically as it relates to Canada’s environmental and sustainable development goals. The government articulated these goals through acts and policy documents, such as the Canadian Net‑Zero Emissions Accountability Act and the 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan.

4.21 Of particular relevance for OSFI is the Federal Sustainable Development Act and the resulting Federal Sustainable Development Strategy. As of 1 December 2020, the act applies to OSFI. The 2022 to 2026 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy includes 101 federal organizations, and each must prepare a sustainable development strategy (Exhibit 4.3).

Exhibit 4.3—Key responsibilities of designated entities under the Federal Sustainable Development Act

Under the Federal Sustainable Development Act, a Federal Sustainable Development Strategy is developed at least once every 3 years, and the strategy is subsequently tabled in Parliament.

According to the 2022 to 2026 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy, sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

Within 1 year after a Federal Sustainable Development Strategy is tabled, each designated entity must prepare a departmental sustainable development strategy that

- contains a plan with objectives

- complies with the Federal Sustainable Development Strategy and contributes to meeting its goals

- takes into account the designated entity’s mandate

- takes into account any Treasury Board policies made under the Federal Sustainable Development Act

- takes into account comments from consultations

Furthermore, designated entities are required to contribute to the development of and reporting on the Federal Sustainable Development Strategy.

4.22 The 2022 to 2026 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy promotes a broader view of sustainable development than previous versions of the strategy, supports a whole‑of‑government approach, and introduces new requirements to ensure transparency and accountability. It is also the first such strategy oriented toward the 17 Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

4.23 The Federal Sustainable Development Strategy includes the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 13 (climate action), which states, “Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts.” In the federal strategy, this action involves

- strengthening resilience and capacity to adapt to climate-related hazards and natural disasters

- integrating climate change measures into national policies, strategies, and planning

- improving education, awareness-raising, and human and institutional capacity on climate change

4.24 Now that it is designated under the Federal Sustainable Development Act, OSFI, reporting to the Minister of Finance, has new obligations, including developing its first departmental sustainable development strategy in 2023 and reporting on its progress in 2024 and 2025. OSFI’s upcoming strategy is required to contribute to meeting the federal strategy’s goals. The federal strategy’s whole‑of‑government approach to sustainable development has ambitious goals, including a target of achieving 40% to 45% greenhouse gas emission reductions below 2005 levels by 2030 and achieving net‑zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

4.25 Organizations designated under the Federal Sustainable Development Act must contribute to advancing the strategy’s goals within their mandates. Nevertheless, entities ought to actively reflect on policy measures they could implement that would further the strategy’s goals, beyond simply greening their operations, while still respecting the intent of their mandates.

4.26 The European Central Bank provides a potential example of such policy choice. In July 2021, its Governing Council decided to take further steps to include climate change considerations in its monetary policy framework. The European Central Bank considers that actions to encourage the economy’s transition away from carbon-intensive industries align with its primary mandate of price stability and support to financial markets.

OSFI’s modest contribution to Canada’s Federal Sustainable Development Strategy goals

4.27 We found that OSFI had not yet considered how its actions could contribute more broadly to sustainable development goals, particularly the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 13, and the Federal Sustainable Development Strategy’s goals while still respecting its primary mandate. According to its own departmental plans and priorities, OSFI aimed to contribute to the United Nations’ Goal 13 over the past 2 fiscal years. However, we found that OSFI had no overarching regulatory or supervisory policies on climate-related financial risks in place in the 2022–23 fiscal year. So, over the past 2 fiscal years, OSFI’s contribution to environmental sustainable development goals consisted of greening its own operations.

4.28 OSFI officials in the Climate Risk HubDefinition 3 we consulted during our audit stressed that the goals under the Federal Sustainable Development Strategy were beyond the scope of OSFI’s work on climate-related financial risks, which focuses on financial stability. They said that the strategy will not have a significant impact on how OSFI implements its role or on its work related to climate-related financial risks because OSFI was not mandated to contribute to the government’s broader climate goals.

4.29 We recognize OSFI’s long-standing approach to implementing its legislative mandate. Yet there are examples, at the international level, of entities that have adopted a more expansive view of their mandates, even when the legal framing of the mandate remained unchanged. As such, given the Government of Canada’s whole‑of‑government approach to achieving ambitious sustainability goals, it would be good practice, in our view, for OSFI to consider whether a more expansive view of its own mandate might be called for and to report on that reflection to all relevant stakeholders.

4.30 The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada should, in its departmental plan and upcoming departmental sustainable development strategy, carefully consider and, if necessary, clearly demonstrate how its policies and programs contribute to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, particularly Goal 13 (climate action), with a set of timelines, performance indicators, and supporting metrics, where appropriate.

The agency’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

OSFI’s plans to address climate-related financial risks were headed in the right direction, but a full implementation is still years away

4.31 This finding matters because it is important for the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada (OSFI) to have a fully developed and implemented approach to address climate-related financial risks before they pose a risk to the resilience of financial institutions and, ultimately, to deposit holders and insurance policyholders. The benefits of addressing these risks early—in terms of stability in financial markets and the economy—could be very large. Conversely, rapid or unpredictable changes to financial regulations could destabilize the financial system. So, it is desirable that financial regulations be stable and predictable and that needed changes be introduced with sufficient implementation times.

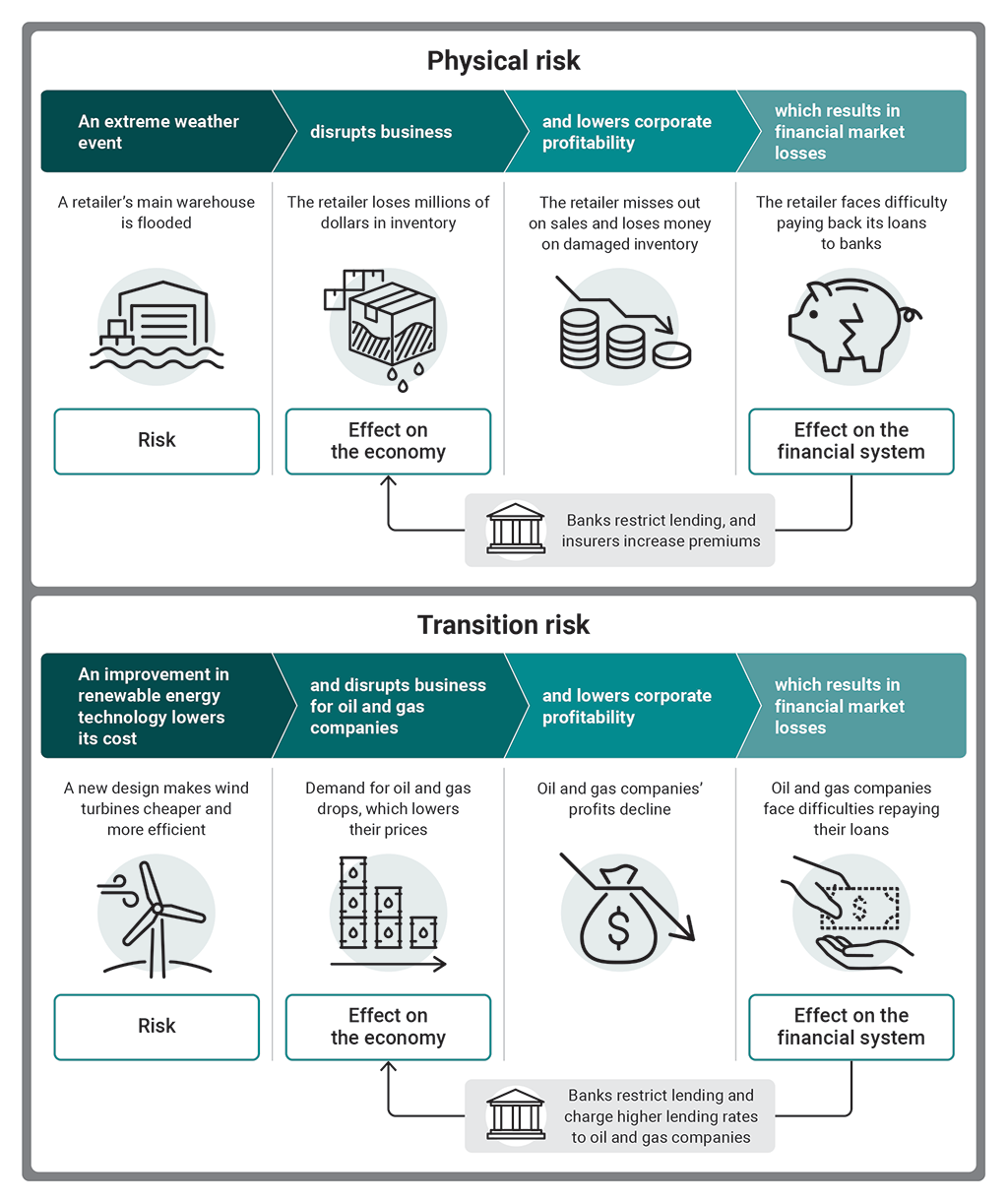

4.32 Climate-related financial risks are typically categorized as either physical or transition risks (Exhibit 4.4):

- Physical risks, such as damage to property, result from the increased severity and frequency of natural disasters and from permanent changes in the climate.

- Transition risks include technological developments and changes in investor and consumer sentiments and government policies, such as the carbon levy in Canada.

These changes affect the business processes of corporations as well as their capacity to generate revenues and repay debt.

Exhibit 4.4—Examples of how the 2 types of climate-related financial risks can affect the economy and financial system

Exhibit 4.4—text version

This exhibit gives examples of how a physical risk, such as a flood, and a transition risk, such as a technology change, can affect the economy and financial system. Physical risks and transition risks are the 2 types of climate-related financial risks.\

The example of how a physical risk can affect the economy and financial system is the following: An extreme weather event disrupts business and lowers corporate profitability, which results in financial market losses. This example is illustrated as follows:

- A retailer’s main warehouse is flooded. This is the risk from an extreme weather event.

- The retailer loses millions of dollars in inventory. This is the effect on the economy from the business disruption for the retailer.

- The retailer misses out on sales and loses money on damaged inventory, thus corporate profits decline.

- The retailer faces difficulty paying back its loans to banks. This is the effect on the financial system from the retailer’s financial losses.

- This effect on the financial system results in banks restricting lending and insurers increasing premiums. These actions affect the retailer that lost millions of dollars in inventory and also affect the economy.

The example of how a transition risk can affect the economy and financial system is the following: An improvement in renewable energy technology lowers its cost, disrupts business for oil and gas companies, and lowers corporate profitability, which results in financial market losses. This example is illustrated as follows:

- A new design makes wind turbines cheaper and more efficient. This transition to the improved renewable energy technology is a risk for the economy and the financial system.

- Demand for oil and gas drops, which lowers their prices. This is the effect on the economy from the business disruption for oil and gas companies caused by the technology transition.

- Oil and gas companies’ profits decline.

- Oil and gas companies face difficulties repaying their loans. This is the effect on the financial system from the oil and gas companies’ financial losses.

- This effect on the financial system results in banks restricting lending and charging higher lending rates to oil and gas companies. These actions affect the oil and gas companies that had to lower their prices because demand dropped and also the economy.

4.33 Canada is highly exposed to both physical and transition risks. According to a Government of Canada report on Canada’s changing climate, temperatures in Canada are rising at more than twice the global average. In Canada’s Arctic, they are rising at about 3 times the global rate. Moreover, the Canadian economy relies strongly on exploiting natural resources, such as oil and gas, forestry, metals, and minerals. As a result, Canada has one of the highest levels of greenhouse gas emissions per capita in the world.

4.34 Transitioning the Canadian economy to net‑zero emissions without delay will require the implementation of ambitious policies and regulations. This could introduce transition risks and significant costs, especially for carbon-intensive industries—translating into risks for the financial institutions that invest in and insure these industries. However, scenario analyses by international organizations have shown that the economic costs of delaying the transition are significant because of the higher physical and transition risks that these delays would generate.

4.35 Tackling climate-induced financial risks is a relatively new challenge for financial supervisors. To help in this endeavour, the Financial Stability Board developed a roadmap that financial supervisors can follow to address climate-related financial risks effectively. This roadmap consists of 4 areas:

- institution-level disclosures to provide a basis for pricing and managing climate-related financial risks at the level of individual institutions and market participants

- data to help create consistent metrics and disclosures and provide the raw material for the diagnosis of climate-related vulnerabilities

- vulnerability analysis, which provides the basis for the design and application of regulatory and supervisory frameworks and tools

- regulatory and supervisory practices and tools that allow authorities to effectively address identified climate-related financial risks to financial stability

Early steps of implementing strategy to address climate-related financial risks

4.36 We found that OSFI had taken several steps to position itself to effectively address climate-related financial risks. OSFI made addressing climate-related financial risks 1 of its 2 priorities, along with cyber-related risks, in its blueprint plan for 2022–25. In early 2022, OSFI also published its Building Federally Regulated Financial Institution Awareness and Capability to Manage Climate-Related Financial Risks strategy. The strategy addressed climate-related financial risks and was based on the Network for Greening the Financial System’s 2020 Guide for Supervisors. The strategy also aligned with the 2022 Financial Stability Board roadmap. We found that OSFI had taken meaningful steps toward implementing its strategy and progress against this strategy was already noticeable.

4.37 OSFI’s strategy lists 7 initiatives that OSFI plans to implement to raise regulated institutions’ awareness about climate-related financial risks:

- climate risk management guidance, which sets best practices or minimum requirements for regulated institutions on how to manage climate-related financial risks

- climate data and analytics

- scenario analysis for climate-related financial risks to explore the potential effects of plausible climate futures on regulated institutions and the financial sector

- climate-related capital and liquidityDefinition 4 considerations to further absorb the effects of climate-related financial risks

- climate-related financial disclosure, which is the publication of the effects of climate-related financial risks on regulated institutions

- stakeholder engagement to foster the development and implementation of best practices

- expansion of OSFI’s in‑house capacity—acquiring human resources and technical expertise to address the challenge

4.38 We found that OSFI had made progress toward implementing its strategy. In early 2022, OSFI created a Climate Risk Hub. By early 2023, OSFI had staffed all its open positions in its Climate Risk Hub, and OSFI demonstrated a willingness to increase the hub’s operations as new responsibilities were added.

4.39 Tangible progress was particularly noticeable against the first and fifth initiatives of OSFI’s strategy with the publication, in May 2022, of OSFI’s consultation on its Draft Guideline B‑15: Climate Risk Management. Guideline B‑15 aims to introduce mandatory climate-related financial disclosures for institutions regulated by OSFI. The guideline’s stated objective is to help improve the quality of regulated institutions’ governance and risk management of climate-related financial risks over time and contribute to public confidence in the Canadian financial system.

4.40 Shortly after launching the Climate Risk Hub, OSFI initiated an internal analysis to identify the data available to address climate-related financial risks, as well as existing data gaps. The analysis was based on the Network for Greening the Financial System guide and feedback from other national supervisors. This analysis and subsequent work to collect climate-related data are essential to enable OSFI to quantify some of the effects of climate change on the financial sector. We found that, although it was still performing its data‑gap analysis, OSFI had already made some progress by planning to collect data from regulated institutions, engaging with other government departments and agencies, and pursuing the acquisition of data from third parties.

4.41 In early 2022, in collaboration with the Bank of Canada, OSFI released the result of a pilot project on climate scenario analysis. Conducted as a learning exercise, the scenarios analyzed the effects of transition risk (Exhibit 4.4) in the 10 most emission-intensive sectors, which together account for about 68% of Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions, from 2020 to 2050. The analysis pilot project included 6 large regulated institutions from 2020 to 2050. OSFI also had 2 similar exercises underway. The first will assess the effects of transition risks on financial institutions regulated by OSFI and some provincially regulated pension plans. The second will assess the way that OSFI‑regulated financial institutions and provincially regulated credit unions will be affected by flooding’s effects on the Canadian real estate sector (including on mortgages).

4.42 OSFI also plans to develop a standardized climate scenario test to assess the effects of climate-related physical and transition risks on all financial institutions. This development is scheduled to take place in the 2024–25 fiscal year and will include all banks, credit unions, and insurers regulated by OSFI.

4.43 We also found that OSFI had engaged with regulated institutions through a survey of selected financial institutions and a discussion paper on the management of climate-related financial risks.

4.44 At the international level, OSFI joined the Network for Greening the Financial System in late 2021. In mid‑2022, the network announced its 2022–24 work program, identifying OSFI as the leading institution for the work stream on supervision.

4.45 Despite this progress, we found that compared with some of its international peers, OSFI had performed little work so far on exploring the potential use of other tools, such as capital requirementsDefinition 5, to address climate-related financial risks. OSFI’s own preliminary analysis showed that implementation of capital requirements in Canada could take place no earlier than 2025 to 2027, depending on the method of implementation, data availability, and international policy developments. OSFI officials told us that not much can advance on that front until OSFI obtains appropriate, quality data. We note that in its Supervisory and Regulatory Approaches to Climate-Related Risks report, the Financial Stability Board’s first recommendation is as follows:

Supervisory and regulatory authorities should accelerate the identification of their information needs for supervisory and regulatory purposes to address climate-related risks and work towards identifying, defining, and collecting climate-related data and key metrics that can inform climate risk assessment and monitoring.

Overdue plan to address climate-related financial risks

4.46 We found that OSFI’s plan to start addressing climate-related financial risks in the Canadian financial system was overdue, given the following strong indications that such action would be needed:

- Canada’s relatively high per capita emissions

- Canada’s high exposure to carbon-intensive industries and associated physical and transition risks

- progress by other jurisdictions on addressing climate-related financial risks

4.47 Furthermore, in 2015, the Government of Canada signed the Paris Agreement, a legally binding international treaty that aims to limit the increase in average global temperature to well below 2 degrees Celsius, and preferably to 1.5 degrees Celsius, above pre‑industrial levels. This sent a strong signal that the Government of Canada aimed to shift to a less carbon-intensive economy.

4.48 We found that OSFI performed limited work on requiring regulated institutions in Canada to address climate-related financial risks prior to the joint OSFI‑Bank of Canada climate scenario pilot exercise announced in late 2020. For example, OSFI

- participated in the work of several international bodies, such as an application paper on the supervision of climate-related financial risks in the insurance sector by the International Association of Insurance Supervisors

- joined the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision’s task force on climate-related financial risks

4.49 In January 2021, OSFI published a discussion paper to gather stakeholders’ views on how regulated institutions define, identify, measure, and build resilience to climate-related risks. OSFI also sought feedback on how it can facilitate regulated institutions’ preparedness for, and resilience to, these risks. According to OSFI, the responses indicated clear support from stakeholders for OSFI to take a more active role in promoting regulated institutions’ management of climate-related financial risks through setting and adopting standards.

4.50 We also found that OSFI was lagging behind some of its international peers in incorporating climate-related financial risks into its supervisory framework. Here are 2 examples:

- As early as 2019, the United Kingdom’s Prudential Regulation Authority published its Supervisory Statement 3/19, which set expectations for regulated institutions to set up a governance structure and risk management strategy on exposure to climate-related financial risks and to use scenario analysis to monitor these risks. The statement also required all regulated institutions to show, by the end of 2021, how they met these expectations.

- In late 2020, the European Central Bank published a similar set of supervisory expectations for the 110 largest banking institutions in the European Union. Although not binding on banks, the expectations were strong and came into effect immediately.

4.51 In comparison, OSFI did not publish its first comparable expectations until May 2022, when it published Guideline B‑15. Given the usual consultation and implementation period for such guidelines, initial public disclosures from B‑15 are expected for the 2023–24 fiscal year. Moreover, the requirements for certain public disclosures—such as investments made to address climate-related financial risks and opportunities or scope 2 and 3 emissionsDefinition 6—will not be implemented until as early as 2025, with some as late as 2027.

4.52 We also found that OSFI lagged behind its peers, such as the United Kingdom’s Prudential Regulation Authority, in public outreach on climate-related financial risks (Exhibit 4.5).

Exhibit 4.5—The United Kingdom’s Prudential Regulation Authority engaged stakeholders early and openly in climate-related financial risks

In 2021, the United Kingdom’s Prudential Regulation Authority published a report exploring the links between climate change and the regulatory capital framework. It concluded that capital requirements, while not the right tool to address the causes of climate change (greenhouse gas emissions), have a role to play in dealing with its consequences (financial risks).

The report was not an official policy document. But it sent a strong signal to regulated institutions and other stakeholders about how the regulator’s thinking on these matters evolves, and it fostered public discussion on difficult issues.

This public discussion was taken further in October 2022 when the Bank of England organized a conference on climate and capital. There, the Bank of England’s executives stressed that they had a “completely open mind” on the integration of climate with their capital framework. Most of the conference participants who responded to a poll stated that climate risks should be reflected in the capital framework.

The authority’s approach to socializing its thinking about policy questions through the publication of research papers followed academic best practices and allowed for early feedback from a broader set of interested stakeholders. Internationally, many policymakers, including the Bank of Canada, follow a similar approach.

4.53 In our view, OSFI would benefit from engaging earlier in the development phase of its various policy instruments and engaging with a broader set of stakeholders. This could be done by regularly publishing some of its analyses on the supervision of climate-related financial risks and summaries of conversations with stakeholders. Other interested parties, such as researchers and experts, could use these published analyses and summaries as an opportunity to engage with OSFI and share their expertise. These interactions could help OSFI expedite the development, refinement, and implementation of its strategy to address climate-related financial risks, which is a complex and multifaceted issue that requires strong collaboration to address.

4.54 The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada should increase the frequency and breadth of its public outreach to engage more broadly and benefit from the perspectives and expertise of civil society about climate-related financial risks and potential tools to address them.

The agency’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

It was unclear how climate-related financial risks would be incorporated into OSFI’s supervisory framework

4.55 This finding matters because climate-related financial risks must be incorporated formally into the supervisory frameworks if all regulated institutions are to be held to the same standards. This is particularly significant to pension plans, which are more exposed to climate-related financial risks than other financial institutions are.

No clarity in incorporation of climate-related financial risks into the future risk assessment framework

4.56 We found that the plans of the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada (OSFI) to incorporate climate-related financial risks into its revised supervisory framework were vague. OSFI’s supervisory framework describes the principles, concepts, and core process that it uses to guide its supervision of federally regulated banks, credit unions, and insurers. At the time of the audit, OSFI was redesigning its supervisory framework to modernize it. OSFI officials told us that they intended to better incorporate climate-related financial risks into the new framework, which OSFI planned to implement in 2024.

4.57 In our view, there is a risk that if climate-related financial risks are not prominent in the new supervisory framework, supervisory teams within OSFI, charged with implementing the framework, might not fully and promptly address them.

4.58 Climate-related financial risks differ from conventional financial risks in several ways, such as longer delays between actions and effects on the risk environment and less data available to quantify the risks. Therefore, it is important that the team in charge of integrating climate-related financial risks in the revised supervisory framework also develop clear guidance for OSFI’s supervisors on how to understand, assess, and challenge the information provided by financial institutions. This is so that OSFI’s supervisors can adequately integrate their assessment of climate-related financial risks in the revised table of risk indicators. Such integration could minimize the risk of greenwashing.Definition 7

4.59 The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada (OSFI) should clarify how it will address climate-related financial risks in its updated supervisory framework. Specifically, climate-related financial risks should be assessed against clear and detailed criteria to

- empower OSFI’s supervisors to challenge the information provided by the regulated institutions

- ensure that all regulated institutions are assessed using the same risk‑based approach

- ensure that the information provided by and the actions taken by regulated institutions to address climate-related financial risks are effective and reduce the risk of greenwashing

The agency’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Unclear expectations on financial institutions’ transition commitments

4.60 We found that OSFI planned to assess and, if needed, challenge financial institutions’ plans to transition to a low‑carbon economy. However, OSFI did not set clear expectations for the content of these transition plans in its Guideline B‑15. Transition plans are another important tool in understanding how an organization plans to adapt to the transition to a low‑carbon economy over the short, medium, and long terms. A transition plan sets out targets and actions, including reducing greenhouse gas emissions, that support an organization’s transition to a low‑carbon economy over the short, medium, and long terms.

4.61 The importance of this tool has been recognized by the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero—the world’s largest coalition of financial institutions committed to transitioning to a net‑zero global economy—in its 2022 Financial Institution Net‑Zero Transition Plans guide. This guide proposes a framework for financial institutions’ plans to create and maintain their transition plans with clear disclosures, interim targets, and metrics.

4.62 We found that in its consultation on Guideline B‑15, OSFI proposed to require all federally regulated financial institutions to publish a transition plan as part of their climate-related disclosure. However, OSFI officials told us that assessments of transition plans might not start until 2025 and might be based on an iterative approach because of the lack of recognized standards to inform the development of criteria to evaluate such plans. To communicate its expectations for transition plans, OSFI planned to align its final Guideline B‑15 with the International Sustainability Standards Board’s updated International Financial Reporting Standard S2: Climate-Related Disclosures, expected to be published in 2023. We note that high-level guidance on what a transition plan ought to contain already exists from organizations such as the Financial Stability Board’s Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures and the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero. OSFI refers to the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures in a footnote of its Guideline B‑15. A lack of clear guidelines from OSFI in this area increases the risk of greenwashing by regulated institutions.

4.63 To strengthen regulated institutions’ accountability for transition to a net‑zero emission economy and to avoid greenwashing, the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada should set clearer guidance about the information reported in the institutions’ transition plans.

The agency’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Limited guidance for federally regulated pension plans

4.64 We found that OSFI provided limited guidance to federally regulated pension plans about how to address climate-related financial risks. Thus, for many small- to medium-size pension plans—the majority of plans supervised by OSFI—it remains uncertain how they will effectively respond to climate-related financial risks.

4.65 Pension plans are central to the economic life of Canadians, providing income to retirees and financial security to contributing workers. Because pension plans necessarily invest over the long term, their assets can be more exposed to physical and transition risks (Exhibit 4.4) than other financial institutions are. As such, how pension plans manage climate-related financial risks is particularly critical to current contributors who will not benefit from their pension income for many years.

4.66 OSFI officials told us that they intended to use the Canadian Association of Pension Supervisory Authorities (CAPSA) Guideline on Environmental, Social and Governance Considerations in Pension Plan Management to guide OFSI’s supervision of climate-related financial risks for federally regulated pension plans. CAPSA is an inter-jurisdictional association of pension regulators, including OSFI and provincial regulators, whose role is to promote the coordination and harmonization of regulatory principles and practices in the supervision of pension plans.

4.67 OSFI officials also told us that it did not produce its own stand-alone guideline because, when it comes to pension plans, there is a long-standing approach of developing harmonized guidance across jurisdictions in certain areas, where possible. This harmonization is favoured because many pension plans operate across provinces and territories, and some of the largest pension plans are regulated by the provinces, not federally. The draft guideline was developed by CAPSA’s environmental, social, and governance committee, which OSFI chaired until June 2022. A draft of the guideline was published in June 2022 for comments, but the final guideline had yet to be published at the time of our audit.

4.68 CAPSA’s draft guideline sets expectations of how plan administrators should consider environmental, social, and governance factors. The guideline recognizes that climate change is now accepted as posing material and urgent financial risks and opportunities. Therefore, climate change is an important environmental, social, and governance factor for consideration by pension plans. Specifically, the guideline first settles the debate that using environmental, social, and governance factors to provide financial insight is consistent with an administrator’s fiduciary duty.Definition 8 The guideline also provides general principles for determining whether a pension plan’s governance, risk management, and investment decision-making practices are sufficient to recognize and respond to material environmental, social, and governance information.

4.69 In terms of disclosure, the draft guideline merely recommends that pension plan administrators disclose in their statement of investment policies and proceduresDefinition 9 whether and how environmental, social, and governance factors are considered in governance, risk management, and investment decision-making practices. CAPSA’s guideline nevertheless encourages plan administrators to ensure that they are keeping pace with disclosure developments and industry best practices. These include industry-specific guidelines and recommendations for pension funds set out by organizations such as the International Sustainability Standards Board and the Financial Stability Board’s Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures.

4.70 CAPSA’s draft guideline is principle-based, rather than prescriptive, and appears to leave much discretion to pension plan administrators. This is despite the fact that, as mentioned in paragraph 4.65, pension plans can be more exposed to physical and transition risks than other financial institutions are. Some large federally and provincially regulated pension plans openly display a willingness to address climate change by initiating or being involved in environmental, social, and governance initiatives, such as the Canadian Coalition for Good Governance or the Investor Leadership Network. Moreover, many of these large pension plans will play an active part in the upcoming and expanded Bank of Canada and OSFI climate-risk scenario analysis. However, in our opinion, there is still a risk that CAPSA’s draft guideline might lead to discrepancies in the quality of environmental, social, and governance consideration by pension plans. For example, some plan administrators may view the requirement as merely an item to include in their statement of investment policies and procedures rather than an integral part of their investment strategy.

4.71 Pension plans are private contracts and workplace benefit arrangements and not public stand-alone businesses or corporate entities. As such, the legal framework for their supervision is different from that of public financial institutions, whose ownership is open to investors, which in turn requires public disclosure. Thus, it would be misplaced to draw a direct comparison between the expectations set in CAPSA’s draft guidelines and OSFI’s Guideline B‑15. However, we note that some of the stakeholders’ submissions in response to CAPSA’s draft guidelines appeared supportive of a more prescriptive approach with clearly articulated baseline standards to help plan administrators and other pension fiduciaries fulfill their fiduciary duties.

4.72 We note that in other jurisdictions, recent legislation or draft legislation imposes more stringent requirements on reporting about climate considerations in investment decisions. Here are 2 examples:

- The United Kingdom’s Pension Schemes Act 2021 requires plans and trustees with more than 100 members to disclose how they have incorporated financially material factors, including environmental, social, and governance factors and climate change, into their investments.

- Article 173 of France’s Energy Transition Law sets a regulatory requirement for investors to report on how they account for environmental, social, and governance criteria.

4.73 Moreover, the Government of Canada clearly indicated in Budget 2022 its policy intent to require environmental, social, and governance disclosure, including climate-related financial risks, by federally regulated pension plans. It moved forward with amendments to the Pension Benefits Standards Act, 1985 to allow regulations to be made respecting the investment of pension fund assets, providing the tools needed to require disclosure of environmental, social, and governance considerations. The amendments came into force on 23 June 2022.

4.74 If CAPSA’s final Guideline on Environmental, Social and Governance Considerations in Pension Plan Management is similar to the draft version, it might not ensure that federally regulated pension plans sufficiently consider climate-related financial risks in their asset management decisions. In that case, exploring other ways to complement CAPSA’s guideline to strengthen the supervision of federally regulated pension plans’ climate-related financial risks would be beneficial. This is especially so considering the government’s expressed policy intent on environmental, social, and governance disclosure. It would also be consistent with the leadership position OSFI now assumes as the chairing institution of the Network for Greening the Financial System’s supervision work stream, which has an objective to support internationally consistent climate-related and environmental disclosure.

4.75 The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada should ensure that its strategy for addressing climate-related financial risks is as consistent as possible among federally regulated pension plans and federally regulated financial institutions, in terms of data, disclosures, vulnerability analyses, and regulatory and supervisory practices.

The agency’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Conclusion

4.76 We concluded that, according to its roles and responsibilities, the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada (OSFI) started incorporating climate-related financial risks into its risk management systems and frameworks for federally regulated financial institutions and, to a lesser extent, for federally regulated pension plans, to contribute to public confidence in the Canadian financial system. OFSI will need to continue its efforts, particularly on its draft Guideline B‑15: Climate Risk Management, to ensure the successful implementation of risk management systems and frameworks. However, OFSI had not yet fully considered its emerging roles and responsibilities under the Federal Sustainable Development Act.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on the supervision of climate-related financial risks. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs and to conclude on whether the supervision of climate-related financial risks complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements, set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada applies the Canadian Standard on Quality Management 1—Quality Management for Firms That Perform Audits or Reviews of Financial Statements, or Other Assurance or Related Services Engagements. This standard requires our office to design, implement, and operate a system of quality management, including policies or procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether, according to its roles and responsibilities, the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada incorporated climate-related financial risks into its risk management systems and frameworks of federally regulated financial institutions and federally regulated pension plans, to contribute to public confidence in the Canadian financial system.

Scope and approach

During the audit, we interviewed representatives and stakeholders of the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada (OSFI). We examined and analyzed documents provided by OSFI. We also analyzed the documents related to public consultations conducted by OSFI and public comments from various stakeholders. Furthermore, we looked at case studies of how OSFI gathered and used information and data from financial institutions.

Criteria

We used the following criteria to conclude against our audit objective:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada identifies and secures adequate internal resources and capacities to assess and supervise federally regulated financial institutions climate-related risks, according to its role and responsibilities. |

|

|

The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada considers the possible use of a variety of techniques and tools at its disposal to assess climate-related risks, in line with evolving best practices of peer countries and relevant international organizations over the period covered by the audit. |

|

|

The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada takes adequate steps to integrate climate-related risks into its supervisory and regulatory framework based on its assessment of climate-related risks, in line with evolving best practices of peer countries and relevant international organizations over the period covered by the audit and Canada’s unique exposure to transition risks. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period from 1 January 2019 to 31 January 2023. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 1 February 2023, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

This audit was completed by a multidisciplinary team from across the Office of the Auditor General of Canada led by Philippe Le Goff, Principal. The principal has overall responsibility for audit quality, including conducting the audit in accordance with professional standards, applicable legal and regulatory requirements, and the office’s policies and system of quality management.

Recommendations and Responses

In the following table, the paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report.

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

4.30 The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada should, in its departmental plan and upcoming departmental sustainable development strategy, carefully consider and, if necessary, clearly demonstrate how its policies and programs contribute to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, particularly Goal 13 (climate action) with a set of timelines, performance indicators, and supporting metrics, where appropriate. |

The agency’s response. Agreed. In 2023–24, the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada (OSFI) will develop and table its Departmental Sustainable Development Strategy that will be aligned with the 2022 to 2026 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy and will discuss strategies to support the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals as applicable. Under the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals 12 and 13 within the federal strategy, there are several targets, milestones, and implementation strategies that OSFI would directly contribute to, which could result in changes to our internal operations and enhance support for initiatives such as the Greening Government Strategy: A Government of Canada Directive. More specifically, OSFI will review its policies and programs with a view to identifying how it can better support goals related to responsible consumption, greenhouse gas emissions, and climate resilience. |

|

4.54 The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada should increase the frequency and breadth of its public outreach to engage more broadly and benefit from the perspectives and expertise of civil society about climate-related financial risks and potential tools to address them. |

The agency’s response. Agreed. The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada (OSFI) will seek to further enhance the frequency and breadth of engagement and discourse with stakeholders about climate-related financial risks and potential tools to address them. In 2022, OSFI commenced engagements with organizations representing different sectors of the real economy, Indigenous peoples and organizations, and climate change non‑governmental organizations. In 2023, OSFI will expand its activities by implementing a Climate Risk Forum as part of its domestic engagement strategy. This multifaceted engagement strategy will ensure that OSFI benefits from a broad range of perspectives and expertise, including those of civil society. |

|

4.59 The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada (OSFI) should clarify how it will address climate-related financial risks in its updated supervisory framework. Specifically, climate-related financial risks should be assessed against clear and detailed criteria to

|

The agency’s response. Agreed. The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada (OSFI) will clarify how climate-related risks will be addressed in the new supervisory framework. The conceptual design for the new supervisory framework, including measures to integrate climate-related risks, received executive approval on 3 October 2022. The new supervisory framework will continue to afford a degree of flexibility to adapt our supervisory approach to reflect the nature, scale, complexity, and risk profile of individual institutions. This includes empowering supervisors to challenge the information provided by regulated institutions, ensuring a consistent approach to implementation across all regulated institutions, and ensuring that information provided by regulated institutions to address climate-related risks reflects the risk profile of the institution. OSFI expects to complete the detailed design and system development for the new supervisory framework by the fall of 2023, with an effective date of 1 April 2024. |

|

4.63 To strengthen regulated institutions’ accountability for transition to a net‑zero emission economy and to avoid greenwashing, the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada should set clearer guidance about the information reported in the institutions’ transition plans. |

The agency’s response. Agreed. In 2022–23, the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada (OSFI) will issue its final Guideline B‑15, which will reflect and communicate OSFI’s prudential expectations for regulated institutions to manage climate-related risks, including for transition plans and their disclosure. OSFI will continue to refine its disclosure expectations in future iterations of the guideline, including aligning with the final International Sustainability Standards Board standard (International Financial Reporting Standard S2: Climate-Related Disclosures). OSFI expects that transition planning will increasingly become important to regulated institutions identifying, managing, and mitigating climate-related risks. By setting supervisory expectations on transition plans, we expect institutions to embed climate-related risks into their enterprise-wide risk management frameworks, including policies, procedures and controls, and accountability and governance structures. This will also facilitate OSFI’s understanding and assessment of regulated institutions’ unique strategies to manage climate-related risks and enable OSFI to make supervisory judgments about regulated institutions’ effectiveness in managing these risks. Prudential assessment of transition plans can strengthen plan accountability, allowing OSFI to contribute, in a manner consistent with its mandate, to other financial sector authorities’ efforts to avoid greenwashing. |

|

4.75 The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada should ensure that its strategy for addressing climate-related financial risks is as consistent as possible among federally regulated pension plans and federally regulated financial institutions, in terms of data, disclosures, vulnerability analyses, and regulatory and supervisory practices. |

The agency’s response. Agreed. The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada’s (OSFI’s) strategy for addressing climate-related risks aims to be as consistent as possible across regulated financial institutions and pension plans, while necessarily reflecting and respecting the differences between the statutory frameworks for federally regulated private pension plans and federally regulated financial institutions. For example, OSFI’s approach to executing its mandate, including for climate-related risks, must consider the unique application of pension plan administrators’ legislated and common law fiduciary duties. OSFI will continue to supervise regulated entities, including pension plans, according to the legislative frameworks set out by the Parliament of Canada. |