2023 Report of the Auditor General of Canada to the Legislative Assembly of NunavutChild and Family Services in Nunavut

Independent Auditor’s Report

WARNING

The content of this audit report and the materials related to it may negatively impact readers.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Early Findings

- Findings

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- Exhibits:

- 1—Required actions after a referral was made to the Department of Family Services were not taken, 1 January 2019 to 31 March 2022

- 2—A significant percentage of required screening actions for 12 new foster homes were not completed by the Department of Family Services from 1 January 2019 to 31 March 2022

- 3—The Department of Family Services had 95 children, youth, and young adults in placements outside of the territory as of March 2022

- 4—The Department of Family Services’ budget and actual spending, 2018–19 to 2023–24

- 5—Many communities had no community social services worker for up to 25 months from 1 January 2019 to 31 May 2022

Introduction

1. Nunavut has the youngest and one of the fastest growing populations in Canada, with people under the age of 15 making up more than 30% of a population of about 40,000 Nunavummiut. The well‑being and safety of these young people and their families and community endure as core Inuit values. They are reflected in Inuit societal values, including Pijitsirniq, which means serving and providing for family or community, and Inunguqsainiq, which means nurturing or raising an individual to be a productive member of society as stated in the Child and Family Services Act.

2. In Nunavut, intergenerational trauma resulting from colonialism and residential schools, compounded by social and economic challenges such as inadequate housing, food insecurity, poverty, and remoteness, creates a complex range of issues that put some children and families at risk and in need of child protection and family services.

3. In 2014, we conducted a follow‑up audit focused on the progress made by the Department of Family Services on key deficiencies found in our 2011 audit of child and family services in Nunavut. The 2014 audit found that the department made unsatisfactory progress in complying with key child protection standards and ensuring ongoing human resources capacity to fulfill its mandate.

4. The audit examined whether the Department of Family Services and the Department of Health, with the support of the Department of Human Resources, provided services to protect and support the well‑being of vulnerable children and youth and their families in accordance with legislation, policy, and program requirements from 1 January 2019 to 31 May 2022.

5. More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

6. The Department of Family Services is responsible for delivering programs and services related to child and family services, poverty reduction, income assistance, and career development. Within the department, the Family Wellness division provides support services for children, youth, and vulnerable adults who may require protection or other specialized support. The division assists individuals, families, groups, and communities to develop skills and make use of both personal and community resources to enhance their well‑being.

7. The Health Care Service Delivery Branch of the Department of Health provides clinical services at community and regional health centres and at the Qikiqtani General Hospital in Iqaluit. In terms of child protection, the department’s nurses provide care to children and youth who have experienced abuse and neglect. The branch’s Mental Health and Addictions program has a mandate to provide a person-centred, comprehensive continuum of care to those individuals and families experiencing emotional distress or psychiatric disorders.

8. The Department of Human Resources’ staffing division works in collaboration with government departments to develop and implement recruitment initiatives. The department is the lead in allocating the Government of Nunavut staff housing.

Early Findings

Letters to senior management

9. Our early findings during this audit on child protection services were so alarming that we brought our concerns to the Department of Family Services’ attention without delay.

10. We issued a first letter to senior management of the Department of Family Services in December 2022. We informed the department that we found limited or no evidence that it had investigated many referrals of child abuse and neglect. We also informed the department of our concerns about many significant gaps in its case management and supervision of children and youth under its care, including children and youth in foster homes. Without evidence that the department had responded to referrals, and given the gaps we identified in case management and supervision, we were deeply concerned that some children and youth did not receive the protection and services they needed and were entitled to under the Child and Family Services Act.

11. We identified 47 cases for follow‑up, involving 92 children and youth. In 42 cases (85 children and youth), we identified possible follow‑up actions the department could consider—including face‑to‑face follow‑up with the young people involved in the cases—because we were concerned that their safety and well‑being could still be at risk. For the remaining 5 cases (7 children and youth), we requested documentation related to key steps in the departmental standards that was missing from files. In March 2023, the department provided us with information on the actions it took in response to our concerns:

- In 48% of cases (20 of the 42 cases involving 36 children and youth), the department responded that it had followed up and that there were no concerns regarding the safety and well‑being of the children and youth we identified. We received no evidence to support those statements.

- In 33% of cases (14 of 42 cases involving 33 children and youth), follow‑up actions were underway.

- In the remaining 19% of cases (8 of 42 cases involving 16 children and youth), the department did not provide any information about its follow‑up on the children or youth in question.

12. Overall, it is our view that the department’s responses to our concerns did not alleviate our unease about the safety and well‑being of all the children and youth we had identified. The department needs to introduce long‑term and sustainable improvements to its process of responding to reports of suspected child abuse.

13. The concerns and possible follow‑up actions we put forward for consideration were based on information we received from the department. The department remains responsible for determining the appropriate action in the instances we identified.

14. We issued a second letter in March 2023, in which we raised concerns over how the department manages the health and safety of its employees. We noted that the department had neither a health and safety program nor a workplace violence policy.

15. Despite evidence of incidents of physical assault, verbal abuse, and threatening behaviour against workers, we found that the department did not have a system in place to collect and manage occupational health and safety incident reports.

16. The department told us that it does not have the resources at this time to address these gaps. We are very concerned that the department’s lack of required protection places frontline workers at risk.

Findings

Referrals to family services

Failure to act on reports of suspected harm

17. We found a number of significant deficiencies in how the Department of Family Services responded to reports of suspected harm and how it supported children and youth in foster care as well as those placed in care facilities outside of the territory. We identified a number of long‑standing issues that in our opinion contributed to those deficiencies. These issues relate to funding, staffing, housing and office space, training, and management of files. They are discussed starting at paragraph 38.

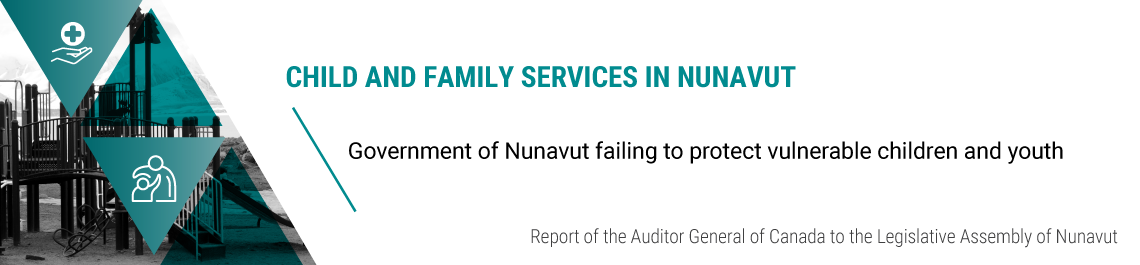

18. Employees of the department are required under the Child and Family Services Act to respond to cases where a child may be in need of protection. These referrals can be reported by, for example, nurses, police officers, teachers, family members, or neighbours. Under the department’s standards and procedures, community social services workers must screen all child and family referrals received by the department to determine whether there are possible child protection risks or whether families have other needs. In our sample of 51 case files across 5 communities, there were 92 such referrals. We found that in 20 of the 92 referrals we examined, the department did not do a screening of the child’s risk and circumstances (Exhibit 1).

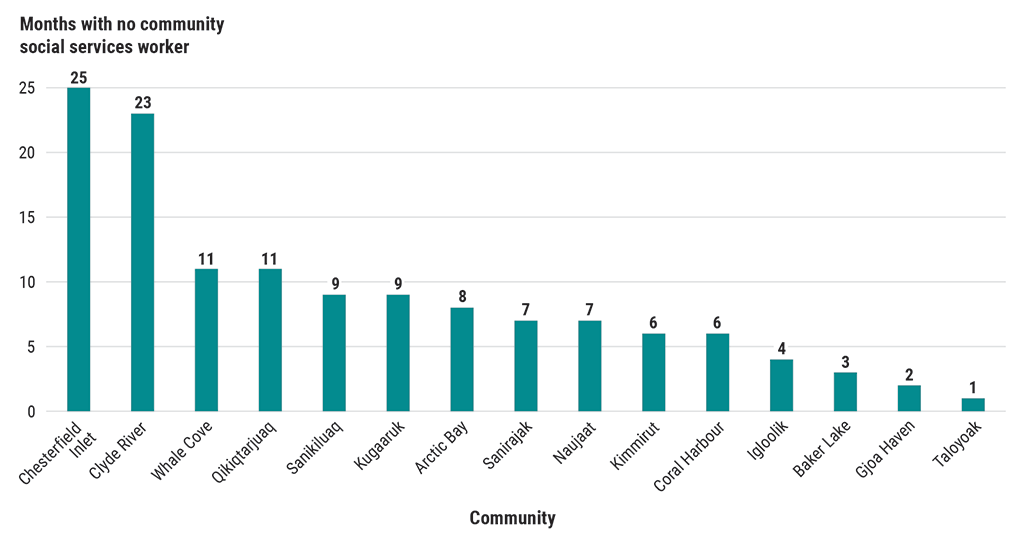

Exhibit 1—Required actions after a referral was made to the Department of Family Services were not taken, 1 January 2019 to 31 March 2022

Source: Based on the requirements under the Nunavut Child and Family Services Act, the Department of Family Services’ Children and Family Services Standards and Procedures Manual (2018), and The Structured Decision Making System for Child Protective Services—Policy and Procedures Manual (updated 2019), Government of Nunavut and the National Council on Crime and Delinquency Children’s Research Center

Exhibit 1—text version

This flow chart shows the required actions to take after a referral is made to the Department of Family Services. It also shows how the department performed from 1 January 2019 to 31 March 2022.

The first action after a referral is made to the department is to screen the referral.

When a report concerning a child, youth, or family is received, a community social services worker must screen a child’s risk and circumstances within 24 hours to decide on a course of action, including whether to start an investigation.

Of the 92 referrals that were examined, 60, or 65%, were screened in for investigation; 20, or 22%, had no screening done; and 12, or 13%, were screened out (that is, no investigation was needed).

The next action after the screening of referrals is the required investigation for the screened‑in referrals.

The investigation starts within 24 to 72 hours of a referral. The start time can be escalated depending on the identified level of risk to the child.

Of the 92 referrals that were examined, 60 referrals moved to the investigation phase. The investigation phase consists of 2 steps: a safety assessment and a risk assessment.

During the safety assessment step, a community social services worker assesses the immediate safety risks for the child or youth. Of the 60 required safety assessments, 32, or 53%, were not done, and 28, or 47%, were completed.

During the risk assessment step, a community social services worker assesses the level of risk the child faces, which informs the investigation. Of the 60 required risk assessments, 54, or 90%, were not done, and 6, or 10%, were completed.

The final action after the required investigation is the investigation’s conclusion.

The investigation must be completed within 30 days of a referral to arrive at a conclusion on whether a child is in need of protection. Of the 60 required investigations, 30, or 50%, were not completed, and 30, or 50%, were completed.

Of the 30 investigations that were not completed, 15, or 25% of the 60 investigations, were not started, and 15, or 25% of the 60 investigations, were started but not completed. Of the 30 investigations that were completed, 12, or 20% of the 60 investigations, were completed within the timeline, and 18, or 30% of the 60 investigations, were completed late.

19. Of the 72 referrals that were screened, 60 were determined to require investigation. We found that investigations were not started in 15 cases out of the 60 (25%) referrals that we examined. Furthermore, another 15 (25%) were started but not completed.

20. The failure to complete required steps for screening and investigation of a referral means that vulnerable children and youth could be left at risk. We saw very little evidence that supervisors were verifying that required steps in the process were being completed. In addition, when investigations are not concluded, this means that protective services are not being provided to children who might be at risk of maltreatment. These failures are also missed opportunities to assess whether families require support such as parenting, mental health, or addictions services.

Protective services

Little action on plans of care

21. After the Department of Family Services completes an investigation, it has several options for actions to protect children and youth who are determined to need protection. A plan of care is frequently used as a means to keep a child safe within the family home or in foster care, and it is an alternative to the department seeking a child protection order from the court. The plans, which may be extended, are signed by a number of stakeholders, including the department and the person with custody of the child. These plans may include, for example, terms for support services, counselling, or visitation by a parent who may not be living with the child.

22. In 51 case files that we looked at, there were 41 plans of care in place during our audit period. We found in 36 of the 41 plans of care (involving 27 children and 13 families) that the department did not have evidence that the terms of the plans were carried out. Without follow‑up on these care plans, there is no way to know if the issues that gave rise to child protection concerns are still present. This could leave children exposed to further risks.

23. For example, we found a case of a very young child who the department assessed as needing protection due to physical abuse by a parent. The plan of care in the department’s files stated that the child would remain at home and the parent was required to access mental health counselling. However, we found that the department did not follow up on the plan of care and did not contact the child and parent for a year and a half. The department followed up only after it received another report of physical abuse involving the same parent and child. The department set up a new plan of care and placed the child in foster care, but again did not follow up on the child’s safety and well‑being afterward. In our opinion, this is an example of multiple failures: The system failed a child who had been harmed, and failed to help a parent acquire the skills to change a pattern of harm.

24. We also found that some programs and services (such as alcohol and drug counselling, and parenting programs) that were needed to help families were not offered at all by the departments of Health and Family Services in some communities. In others, the programs and services were offered only temporarily, for short periods of time.

25. Furthermore, the Department of Family Services, the Department of Health, and other stakeholders acknowledged in the 2020 Surusinut Ikajuqtigiit: Nunavut Child Abuse and Neglect Response Agreement that collaboration and sharing information are vital for making informed decisions about the protection, safety, and well‑being of children and youth. In 1 community we visited, we found local supervisors had established regular meetings between the Department of Health and the Department of Family Services to discuss individual cases.

Foster care

Lack of oversight and required screening

26. During the period of our audit, the Department of Family Services did not have reliable data on the total number of children and youth in foster care. As of August 2022, the department indicated that there were 180 children and youth in foster care in Nunavut and that there were 140 approved foster homes in the territory. As a result of the gaps and weaknesses in information management that are discussed in paragraphs 56 to 59, we could not confirm the accuracy of these numbers.

27. Removing children from their homes and placing them with extended family or unfamiliar caregivers in foster care or in group homes is done in exceptional situations to safeguard the children’s mental and physical well‑being.

28. In our sample of 51 files, there were 26 children placed in 15 foster homes. We found that the department did not have evidence of check‑ins with any of the children or the foster homes as required. Monthly check‑ins at the foster home, by telephone or in person, are required, as are private, face‑to‑face meetings with children every 6 weeks. Alarmingly, we found that the department had no evidence of contact with the children or the foster home for extended periods including

- gaps of 6 to 8 months for 8 children in 4 of the foster homes we examined

- no check‑ins on 10 children in 6 foster homes for 12 months or more, including 2 foster homes with no check‑ins during the 39‑month period of our audit

29. In the absence of check‑ins, the department did not know about children’s well‑being or safety, or their whereabouts, what kind of care they were receiving in their foster home, or whether the foster home was receiving any required support. For example, we found that:

- The department learned that 2 children it had not contacted for 4 months were no longer in their foster placement and were living elsewhere.

- The department learned that 2 children who were temporary wards of the department were once again living with the parent who had lost custody of them. The department learned about this a month after the children were back with the parent. Nothing on file indicates that the department took action to ensure the safety and well‑being of the children afterward.

- There was no evidence that the department took action when it received information that 10 children in foster care were experiencing suicidal thoughts or had attempted suicide, or were at risk of sexual abuse or physical harm.

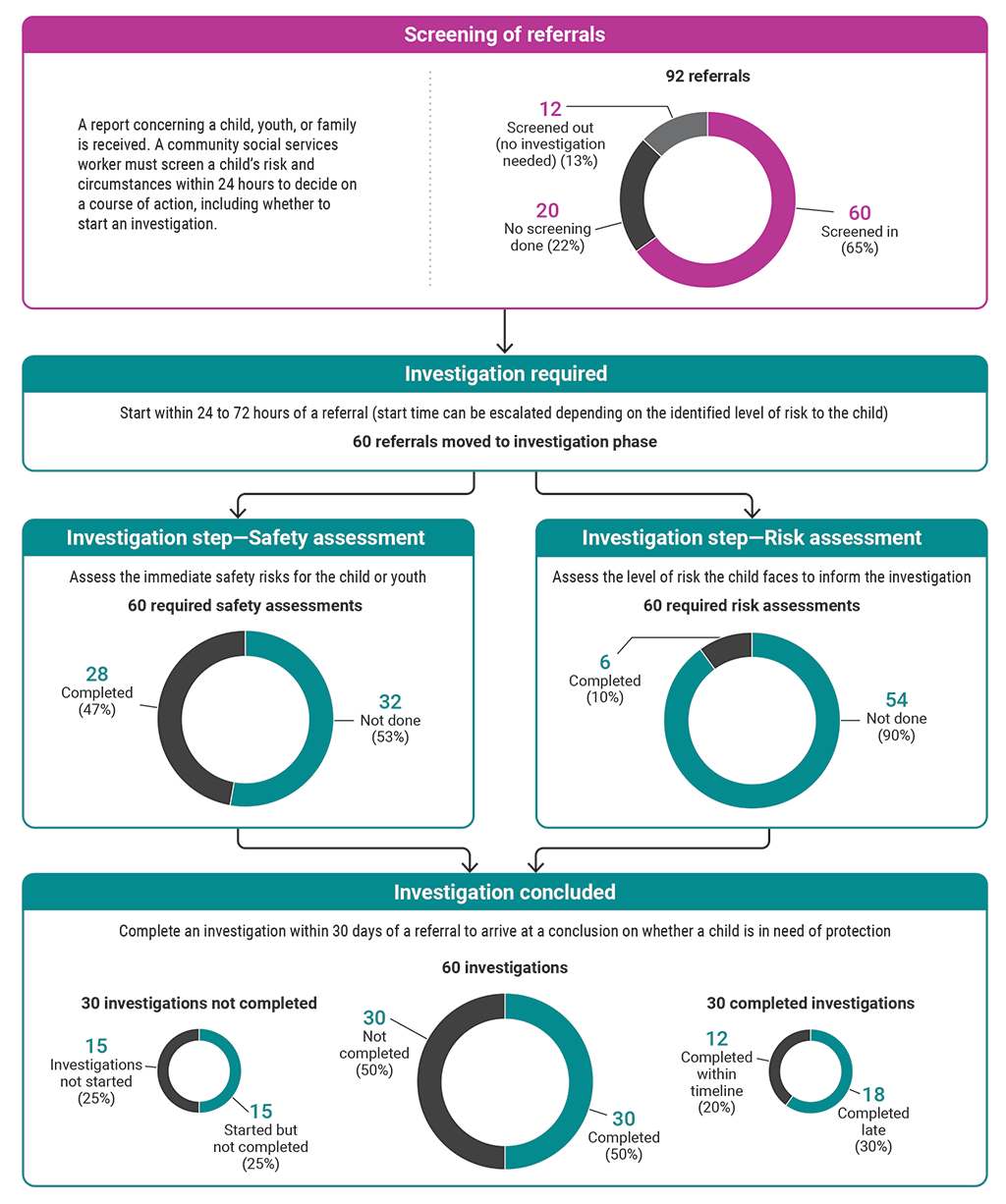

30. We selected an additional 6 foster homes for a total of 21 foster homes across the 5 communities. Of these, 12 were new. We found that the department did not thoroughly screen these new homes (Exhibit 2) or carry out required reviews of the established ones. Screening new foster homes and monitoring established ones are essential to confirming a safe and stable environment for children.

Exhibit 2—A significant percentage of required screening actions for 12 new foster homes were not completed by the Department of Family Services from 1 January 2019 to 31 March 2022

Exhibit 2—text version

This bar chart shows the percentages of required screening actions that the Department of Family Services did not complete for 12 new foster homes from 1 January 2019 to 31 March 2022.

In descending order, the percentages that were not completed were as follows:

- 83% of the criminal record checks were not completed. A criminal record check verifies whether an adult living in a foster home may have a criminal record. Additional steps need to be taken to confirm whether a criminal record exists.

- 58% of the home studies were not completed. A home study is an assessment of the suitability of a prospective foster home and includes a visit to the home.

- 50% of the vulnerable sector checks were not completed. A vulnerable sector check verifies whether an adult living in the foster home has a criminal record as well as any pardon for sexual offences.

- 33% of the foster home engagements were not completed. A foster home agreement is an agreement between the department and the foster home that outlines roles and responsibilities to provide a safe environment.

31. We also found that the department did not direct community social services workers and supervisors on what to do when the results of criminal or vulnerable sector checks had positive or possible matches. In 6 of the foster home files we examined, the department approved and continued foster placements where adults in the foster home had criminal record matches. We found only 1 of these 6 homes where departmental employees contacted the Royal Canadian Mounted Police in order to confirm whether a criminal record or other record existed.

Out of territory

Few check‑ins on children and youth

32. When services are not available within the territory’s 25 communities or when exceptional circumstances warrant it, an option for children, youth, and young adults (aged 19 to 26 years) is to be placed in care outside of the territory. Placement out of territory includes both for foster care and special needs. Removing young people from their homes, schools, and communities—from the Inuit culture and land—requires tremendous consideration and care. The impacted children are at risk of losing their culture and identity. Their placement must be one that provides the children with a living arrangement that will support their physical, mental, and emotional well‑being.

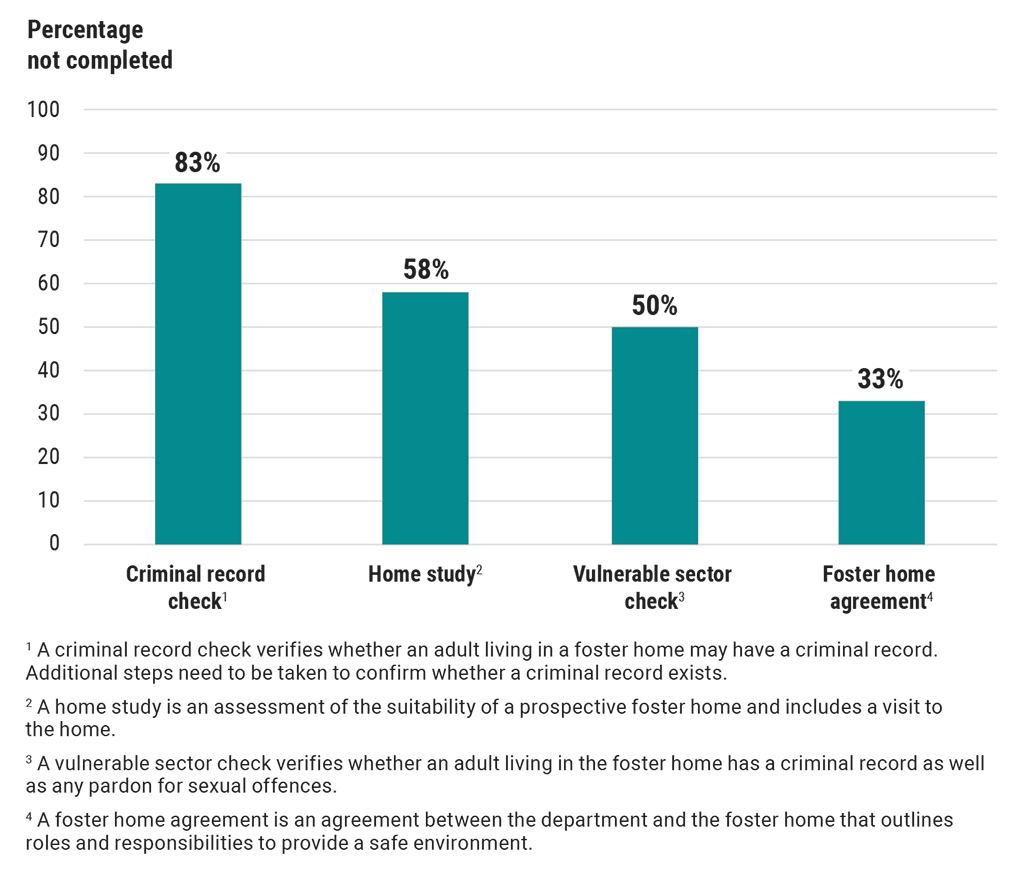

33. We received information from the Department of Family Services that 95 young people were under the department’s care living out of territory as of March 2022 (Exhibit 3). In the files we reviewed, children, youth, and young adults were placed in Alberta, Manitoba, and Ontario. As a result of the gaps and weaknesses in information management that are discussed in paragraphs 56 to 59, we could not confirm the accuracy of these numbers.

Exhibit 3—The Department of Family Services had 95 children, youth, and young adults in placements outside of the territory as of March 2022

Source: Compiled from Department of Family Services data

Exhibit 3—text version

This map shows the number of children, youth, and young adults from the 3 regions of Nunavut (Qikiqtaaluk, Kitikmeot, and Kivalliq) who were placed outside of the territory. As of March 2022, the total number of out‑of‑territory placements was 95. This number consisted of 43 out‑of‑territory placements of children (aged 0 to 15), 17 out‑of‑territory placements of youth (aged 16 to 18), and 35 out‑of‑territory placements of young adults (aged 19 to 26).

Of the 95 placements outside of Nunavut, 20 were in Alberta, 19 were in Manitoba, and 56 were in Ontario.

Of the 20 placements in Alberta, 2 were placements of children, 2 were placements of youth, and 16 were placements of young adults.

Of the 19 placements in Manitoba, 15 were placements of children, 1 was a placement of youth, and 3 were placements of young adults.

Of the 56 placements in Ontario, 26 were placements of children, 14 were placements of youth, and 16 were placements of young adults.

34. We only found evidence for 1 out of 23 children, youth, and young adults that the required quarterly case reviews with the care providers in southern Canada were done. Apart from this, we did not see evidence that community social services workers from the home community were checking in on a monthly basis with young people as required. Though children, youth, and young adults may have had contact with Inuit client liaison officers or family members during this period, this remains an example of the Department of Family Services failing to take actions that it is required to take. Follow‑up contact with young people placed out of territory would help determine when, or if, they can be brought back to Nunavut and be reintegrated into their culture and communities.

35. We also found that the Department of Family Services could not demonstrate that it had completed, monitored, and tracked annual site reviews for all out‑of‑territory care provider facilities. These reviews confirm whether the facilities are meeting safety and licensing requirements.

36. We also found that the department lacked policies and requirements for important aspects of its out‑of‑territory services. For example, the department recognized the need for it to have Inuit employees in provinces to support children and youth who were in placements out of territory. Inuit client liaison officers are now based in Alberta, Manitoba, and Ontario. However, we found that client liaison officers lacked direction and training on how to support Nunavummiut, and their roles and responsibilities were not clearly defined. In addition, the department did not have a process to regularly review when out‑of‑territory children and youth could be repatriated back to Nunavut.

37. In 2016, the department committed to developing a continuum of services care strategy to keep children, youth, and adults in the territory and bring back those who were placed in facilities in southern Canada. We found that 6 years passed before the department started, in the fall of 2022, to discuss the strategy with stakeholders.

Root causes

38. We found that the Department of Family Services’ inability to meet its responsibilities to Nunavut’s at‑risk children and youth is linked to many intertwined root causes that have contributed to this persistent and chronic crisis. They include funding, staffing, lack of housing and office space, lack of timely training, and poor information management. Our findings in this report echo those of our audits in 2011 and 2014. Employees will not be set up to perform well in their jobs until the department has adequate resources and provides them with the appropriate tools. Over time, the department has repeatedly committed to addressing our recommendations, yet the crisis persists. These interlinked root causes will need to be addressed through interdepartmental collaboration. That will require the government to oversee a whole‑of‑government approach.

Funding

39. We found that the Department of Family Services’ budget and expenditures were stable from the 2018–19 to the 2021–22 fiscal years. Annual expenditures averaged $161.6 million (Exhibit 4). The budget for the 2022–23 fiscal year was $169.6 million, increasing to $179.5 million in 2023–24.

Exhibit 4—The Department of Family Services’ budget and actual spending, 2018–19 to 2023–24 (thousands of dollars)

| Fiscal year | Budget | Actual spending |

|---|---|---|

| 2018–19Note * | $164,500 | $161,728 |

| 2019–20Note * | $164,900 | $169,470 |

| 2020–21Note * | $165,400 | $151,290 |

| 2021–22*Note * | $169,029 | $164,140 |

| 2022–23Note ** | $169,636 | Not available at time of audit |

| 2023–24Note ** | $179,474 | Not available at time of audit |

40. As per the Government of Nunavut’s 2023–26 business plan, the Family Wellness division’s budget for the 2021–22 fiscal year was $75 million. Of that total,

- the budget for the child protection, family violence, and foster care programs was $25.5 million (34% of the Family Wellness division’s budget)

- the budget for facility‑based care, including care provided to children and adults within Nunavut and outside of the territory, was $43.7 million (about 58% of the division’s budget)

41. We found that the department submitted some business cases to increase the number of positions in the Family Wellness division. Between January 2019 and May 2022, the department gained a net of 9 Family Wellness positions. Of the new positions, only 4 were filled by May 2022.

Staffing

42. In May 2022, within the Department of Family Services, the staffing vacancy rate was 49% in the Family Wellness division. We found that community social services workers often are on short‑term contracts, with frequent turnover. In 2022, an average of almost 56% of community social services workers were in short‑term contract positions in Nunavut. The prevalence of short‑term employees leads to a lack of continuity of services, a need for timely training sessions, and increased workloads for supervisors and experienced colleagues. Permanently filling vacancies is required to provide stable, continuous services to vulnerable children, youth, and families. We found that Inuit representation among community social services workers was low. At the end of May 2022, 14 out of the 47 permanent and casual community and social services worker positions were filled by Inuit staff.

43. To identify children at risk, investigate cases, and respond when children need protection, community social services workers and supervisors are needed for carrying out these tasks. Yet we found that some communities went months without a community social services worker during our audit period (Exhibit 5). This included large communities such as Igloolik, with a population of over 2,000. During our audit period, Igloolik had only a single community social services worker for 18 months and had no community social services workers at all for 4 separate months. Clyde River, with a population of more than 1,000, had no community social services worker for 23 months of the audit period. We also found that 8 communities with populations of 1,000 or more spent 18 or more months in that time period with only 1 community social services worker, which would have left any individual working alone on call almost permanently.

Exhibit 5—Many communities had no community social services worker for up to 25 months from 1 January 2019 to 31 May 2022

Exhibit 5—text version

This bar chart shows the number of months during which each of 15 Nunavut communities had no community social services worker. Two communities had no community social services worker for 25 and 23 months. The other communities were without a community social services worker from between 1 month and 11 months. Here, in descending order, are the details:

- Chesterfield Inlet had no community social services worker for 25 months.

- Clyde River had no community social services worker for 23 months.

- Whale Cove had no community social services worker for 11 months.

- Qikiqtarjuaq had no community social services worker for 11 months.

- Sanikiluaq had no community social services worker for 9 months.

- Kugaaruk had no community social services worker for 9 months.

- Arctic Bay had no community social services worker for 8 months.

- Sanirajak had no community social services worker for 7 months.

- Naujaat had no community social services worker for 7 months.

- Kimmirut had no community social services worker for 6 months.

- Coral Harbour had no community social services worker for 6 months.

- Igloolik had no community social services worker for 4 months.

- Baker Lake had no community social services worker for 3 months.

- Gjoa Haven had no community social services worker for 2 months.

- Taloyoak had no community social services worker for 1 month.

44. The Department of Family Services did not collect and analyze data on the caseload of community social services workers. Their responsibilities include screening referrals, conducting investigations, screening foster homes, monitoring children in foster care and out of territory, and attending court, among many other duties. Without a detailed workload analysis, the department cannot reliably determine how many community social services workers are needed in each community.

45. One of our recommendations in 2014 was to fill community social services worker positions with permanent employees in all communities. However, the department continues to hire workers on 4‑month contracts, and these casual workers are primarily from outside of Nunavut. Between January 2019 and May 2022, the department employed a total of 103 individual casual community social services workers. The majority—79 (77%)—came from outside the territory. These workers need the department’s support to become oriented to the work required and to the communities, culture, and language.

46. Inuit employees in the Family Wellness division, like family resource workers or interpreters, enhance social services and lessen the workload of community social services workers through their knowledge of Inuit culture, languages, and the communities. We found that up to 8 communities spent half or more of the year without any Inuit Family Wellness employees between 2019 and 2022. We found that at the end of May 2022, only 5 of 10 family resource worker positions were filled with permanent employees, and there was 1 family resource worker on a casual contract.

47. We also found that the percentage of positions occupied by full‑time supervisors has decreased steadily. In 2019 and 2020, the 12 funded supervisor positions in the department’s Family Wellness division were filled an average of 73% of the time with permanent employees. This fell to an average of 51% in 2021 and remained low at 50% in the first 5 months of 2022. There was no information available to explain this decrease.

48. We also found chronic shortages of Department of Health frontline health care and mental health and addictions workers: In the first 5 months of 2022, the average vacancy rate was 46% for frontline health care workers, and 68% for mental health and addictions workers. Staffing shortages resulted in reduced service levels in community health centres.

Staff housing and office space

49. We found that recruitment delays were attributable in part to staff housing requests that were pending for 6 months to 2 years. Although access to staff housing units was insufficient in many communities, the Department of Human Resources did not assess what staff housing was needed in each community.

50. In the 2021–22 fiscal year, the Department of Family Services identified 13 communities in which its offices needed repairs or additional space. In several cases, lack of office space resulted in employees working in space borrowed from the Department of Health, or in overcrowded spaces. Community social services workers need to have a workspace that allows them to interact with children, youth, and their families in a safe and confidential manner.

Lack of training

51. Department of Family Services. The department had a mandatory 5‑day core training for community social services workers and 5‑day training—StepWise 360—on techniques for interviewing children who may have been victims of abuse. We found that the median number of months casual and permanent workers waited from starting employment to receiving core training was about 10 months, and about 19 months before the department provided training on interviewing techniques.

52. Because the department is addressing vacancies by hiring casual employees on 4‑month contracts, some employees never received the mandatory training at all. The situation may create risks that employees are not equipped to carry out their work to protect children.

53. In addition, the department had only 1 position to do all the scheduling, booking of space, documenting of files, and travel arrangements related to training. The position was filled for only 21 months of the audit period.

54. Department of Health. Training can also help frontline health care providers such as nurses correctly identify child maltreatment when children are visiting health centres. They are frequently the first to witness signs of child abuse, harm, and neglect and are legally required to report cases where they believe a child needs protection.

55. We found that the Department of Health provided orientation training on child welfare topics, such as when to report on cases of child maltreatment and to whom cases should be reported. However, it acknowledged that more training and guidance were needed in this area.

Ineffective information management

56. Ineffective information management is another root cause of the failures in child and family services. Having access to reliable, accurate, up‑to‑date information in a central system—and training staff to use it—is essential for continuity of knowledge and informed decision making. Information and the means to access it provide frontline workers with what they need to carry out their work. This includes information such as where vulnerable children and youth are living, their plans of care and past history, and whether necessary follow‑up visits are being conducted.

57. Following our 2014 audit, the Department of Family Services developed a new online system for managing information. However, the department subsequently determined that the system did not meet its needs; for example, for aggregating and reporting data. The department procured a new system in 2022, which it plans to have implemented later in 2023.

58. In this audit, we found that the Department of Family Services was not meeting its own standards on records management nor did its information management practices comply with the Government of Nunavut’s policies on record management.

59. We found that each of the 5 communities we visited had different approaches to managing their case files. Some communities kept paper files; some kept electronic files on individual computers, universal serial busUSB keys, or in the department’s existing case management system; and some combined methods. In some communities, we also found that files—such as paper copies and USB keys—were not stored in a way that would protect confidentiality.

Conclusion

60. We concluded that the Department of Family Services consistently failed to take action to protect and support the well‑being of vulnerable children, youth, and their families in accordance with legislation, policy, and program requirements. In addition, the Department of Health and the Department of Human Resources have not provided needed support and resources, such as in the areas of training, staffing, and staff housing.

61. Our findings are more than statistics, trends, and a compilation of facts. This report is a call to action. To protect the territory’s vulnerable children and youth, solutions lie in a whole‑of‑government approach to overcome the challenges in serving Nunavut’s 25 communities. We ask that the Government of Nunavut act to compel the departments of Family Services, Health, and Human Resources to collaboratively take urgent and necessary concrete actions to help safeguard Nunavut’s children, and support the territory’s families and communities.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on child and family services in Nunavut. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist the Legislative Assembly in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs and to conclude on whether the management of services to protect and support the well‑being of vulnerable children and youth and their families complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements, set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada applies the Canadian Standard on Quality Management 1—Quality Management for Firms That Perform Audits or Reviews of Financial Statements, or Other Assurance or Related Services Engagements. This standard requires our office to design, implement, and operate a system of quality management, including policies or procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether the Department of Family Services and the Department of Health, with the support of the Department of Human Resources, provided adequate services to protect and support the well‑being of vulnerable children and youth and their families in accordance with legislation, policy, and program requirements.

Scope and approach

The audit included an examination of the following key areas:

- child protection interventions and supportive services to children and their families

- placements of children and youth outside of the home (foster care in territory and out‑of‑territory foster care and facility care)

- the fostering of a workforce that is competent, stable, culturally informed, and representative of the population

The Department of Family Services, the Department of Health, and the Department of Human Resources were within the scope of the audit.

Audit work consisted of interviews with staff with the 3 departments and a review and analysis of data and key documentation provided by the departments. We also had interviews with representatives from organizations based in Nunavut to obtain their perspectives on the delivery of child and family services provided to Nunavummiut.

The audit included visits to 5 communities across Nunavut’s 3 regions to conduct interviews with departmental officials with the Department of Family Services and the Department of Health and stakeholders and to select a sample of files for our examination. In each of the 5 communities, we selected a random sample of Department of Family Services’ case files and foster home files. Through these, we examined the Family Wellness division’s response to referrals about children and families, delivery of case management services, and screening and support of foster homes. In each of the communities, we supplemented the random sample with a judgmental sample of files identified as child protection cases. In total, we examined 51 case files, which included 15 foster home files, and we also examined an additional 6 foster home files.

In addition, we audited the case files of 23 young Nunavummiut who were in placements in southern Canada through the Department of Family Services (foster homes or other care facilities) to examine how the department was monitoring and supporting them while they were out of territory and how it was conducting placement planning, including possible repatriation back to Nunavut. These files were randomly sampled from Family Wellness division files in the same 5 communities.

Our analysis of staffing levels was based on the Department of Human Resources’ monthly establishment reports for permanent and casual employees in the 3 departments we audited.

Our case file testing covered the period from 1 January 2019 to 31 March 2022, while our human resources analysis covered the period from 1 January 2019 to 31 May 2022.

Our findings from the samples relate only to the files reviewed and are not meant to statistically represent the entire population of children, youth, young adults, and families receiving services through the Department of Family Services.

Some audit findings relate to events/developments that occurred after the end of our audit period. We decided to report on them given their significance. Some data is based on the most recent information we could obtain from the departments.

We integrated questions about the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals into our audit approach. This reflects our commitment to do so in our Sustainable Development Strategy.

Criteria

We used the following criteria to conclude against our audit objective:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period from 1 January 2019 to 31 May 2022, and our case file testing covered the period from 1 January 2019 to 31 March 2022. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies. However, to gain a more complete understanding of the subject matter of the audit, we also examined certain matters that preceded the start date of this period.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 15 April 2023, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

This audit was completed by a multidisciplinary team from across the Office of the Auditor General of Canada led by James McKenzie, Principal. The principal has overall responsibility for audit quality, including conducting the audit in accordance with professional standards, applicable legal and regulatory requirements, and the office’s policies and system of quality management.