2023 Report of the Auditor General of Canada to the Legislative Assembly of Nunavut

Child and Family Services in Nunavut

WARNING

The content of this audit report and the materials related to it may negatively impact readers.

At a Glance

This audit report describes a crisis. It is a call for change. We are urging the Government of Nunavut to take immediate action to protect the vulnerable children and youth of the territory.

When children are at risk in their home environments, we found that the Department of Family Services did not respond or was slow to act in many cases. The audit found failures in all areas examined, from responding to reports of suspected harm, to completing investigations and following up with children, youth, and young adults placed in care in the territory or in southern Canada. Alarmingly, the Department of Family Services also could not provide accurate numbers on the number of children in its care.

This is the third time since 2011 that we have raised these concerns. The alarm has been echoed by other voices, including Nunavut’s Representative for Children and Youth, who works to protect the rights of children and youth in the territory.

The primary objective of Nunavut’s Child and Family Services Act is to promote the best interests, protection, and well-being of children. It embodies the principle that children are entitled to protection from abuse and harm and from the threat of abuse and harm. However, despite the department’s obligations contained in the act, many children are not receiving the protection to which they are entitled.

The Department of Family Services’ inability to meet its responsibilities is the result of severe, chronic gaps in critical areas such as staffing, housing and office space for employees, and training of employees. We also found that the department is not taking appropriate steps to provide a safe work environment for its employees.

This report does not contain formal recommendations. We found that recommendations in our previous 2 reports received agreement from the department and commitments for significant improvements that have yet to result in changed outcomes for the territory’s children, youth, and families. This report instead lays out our findings and some important root causes for the systemic failings in child and family services.

Ultimately, the responsibility and accountability for action rest with the government and its leaders. We are prepared to work with the government and the Legislative Assembly on future steps to address the findings.

Please see the full report to read our complete findings.

Exhibit highlights

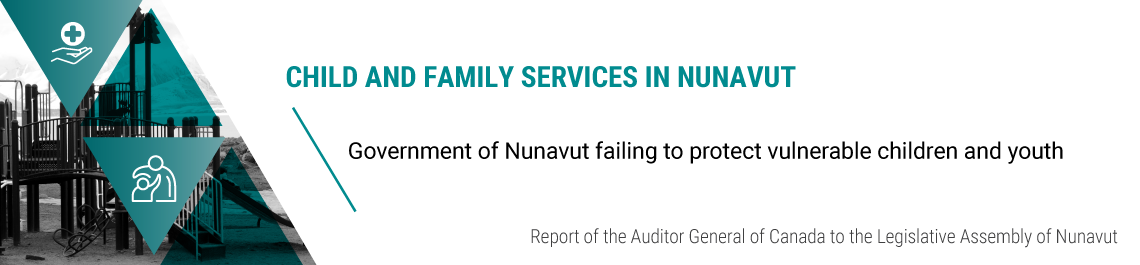

A significant percentage of required screening actions for 12 new foster homes were not completed by the Department of Family Services from 1 January 2019 to 31 March 2022

Text version

This bar chart shows the percentages of required screening actions that the Department of Family Services did not complete for 12 new foster homes from 1 January 2019 to 31 March 2022.

In descending order, the percentages that were not completed were as follows:

- 83% of the criminal record checks were not completed. A criminal record check verifies whether an adult living in a foster home may have a criminal record. Additional steps need to be taken to confirm whether a criminal record exists.

- 58% of the home studies were not completed. A home study is an assessment of the suitability of a prospective foster home and includes a visit to the home.

- 50% of the vulnerable sector checks were not completed. A vulnerable sector check verifies whether an adult living in the foster home has a criminal record as well as any pardon for sexual offences.

- 33% of the foster home engagements were not completed. A foster home agreement is an agreement between the department and the foster home that outlines roles and responsibilities to provide a safe environment.

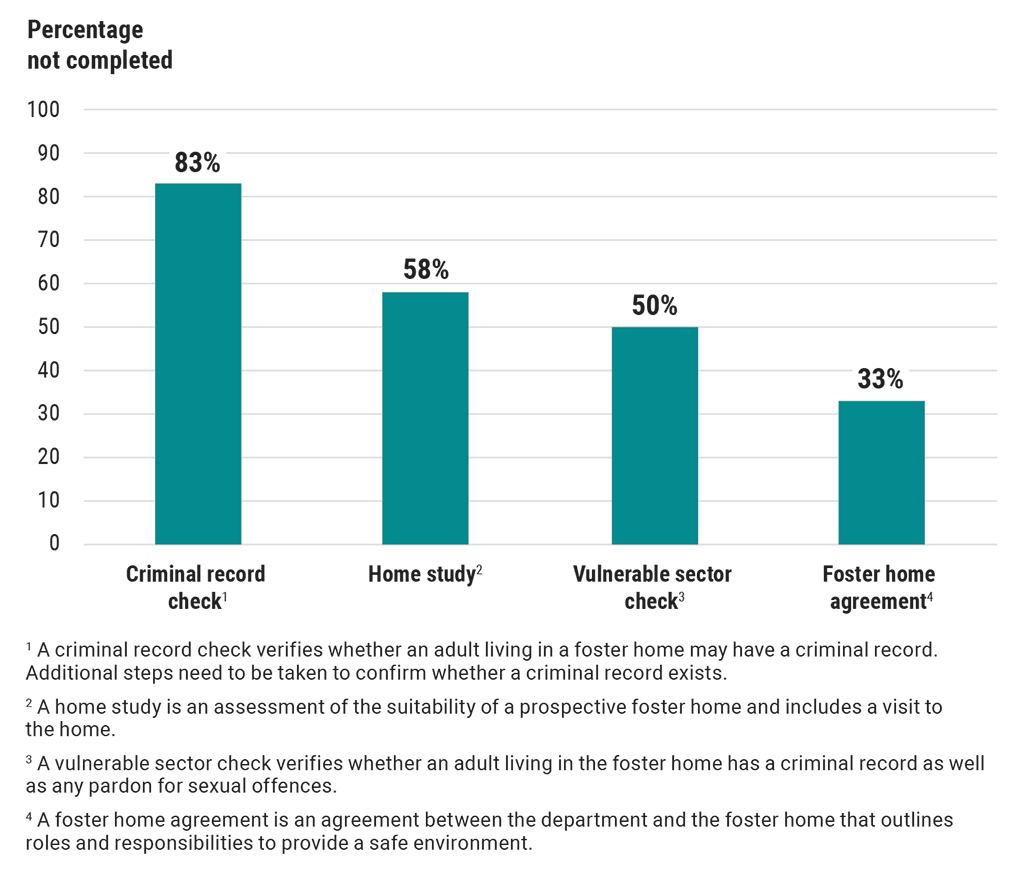

The Department of Family Services had 95 children, youth, and young adults in placements outside of the territory as of March 2022

Source: Compiled from Department of Family Services data

Text version

This map shows the number of children, youth, and young adults from the 3 regions of Nunavut (Qikiqtaaluk, Kitikmeot, and Kivalliq) who were placed outside of the territory. As of March 2022, the total number of out‑of‑territory placements was 95. This number consisted of 43 out‑of‑territory placements of children (aged 0 to 15), 17 out‑of‑territory placements of youth (aged 16 to 18), and 35 out‑of‑territory placements of young adults (aged 19 to 26).

Of the 95 placements outside of Nunavut, 20 were in Alberta, 19 were in Manitoba, and 56 were in Ontario.

Of the 20 placements in Alberta, 2 were placements of children, 2 were placements of youth, and 16 were placements of young adults.

Of the 19 placements in Manitoba, 15 were placements of children, 1 was a placement of youth, and 3 were placements of young adults.

Of the 56 placements in Ontario, 26 were placements of children, 14 were placements of youth, and 16 were placements of young adults.

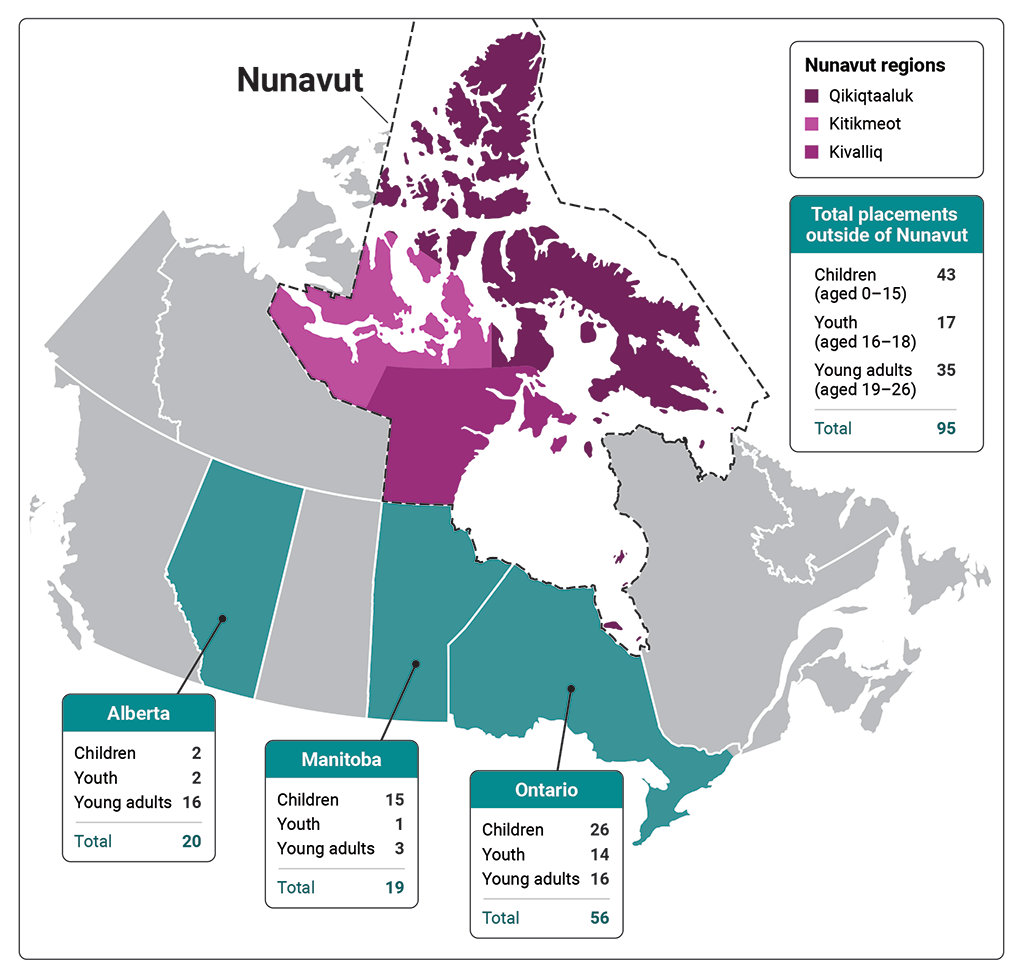

Many communities had no community social services worker for up to 25 months from 1 January 2019 to 31 May 2022

Text version

This bar chart shows the number of months during which each of 15 Nunavut communities had no community social services worker. Two communities had no community social services worker for 25 and 23 months. The other communities were without a community social services worker from between 1 month and 11 months. Here, in descending order, are the details:

- Chesterfield Inlet had no community social services worker for 25 months.

- Clyde River had no community social services worker for 23 months.

- Whale Cove had no community social services worker for 11 months.

- Qikiqtarjuaq had no community social services worker for 11 months.

- Sanikiluaq had no community social services worker for 9 months.

- Kugaaruk had no community social services worker for 9 months.

- Arctic Bay had no community social services worker for 8 months.

- Sanirajak had no community social services worker for 7 months.

- Naujaat had no community social services worker for 7 months.

- Kimmirut had no community social services worker for 6 months.

- Coral Harbour had no community social services worker for 6 months.

- Igloolik had no community social services worker for 4 months.

- Baker Lake had no community social services worker for 3 months.

- Gjoa Haven had no community social services worker for 2 months.

- Taloyoak had no community social services worker for 1 month.

Infographic

Text version

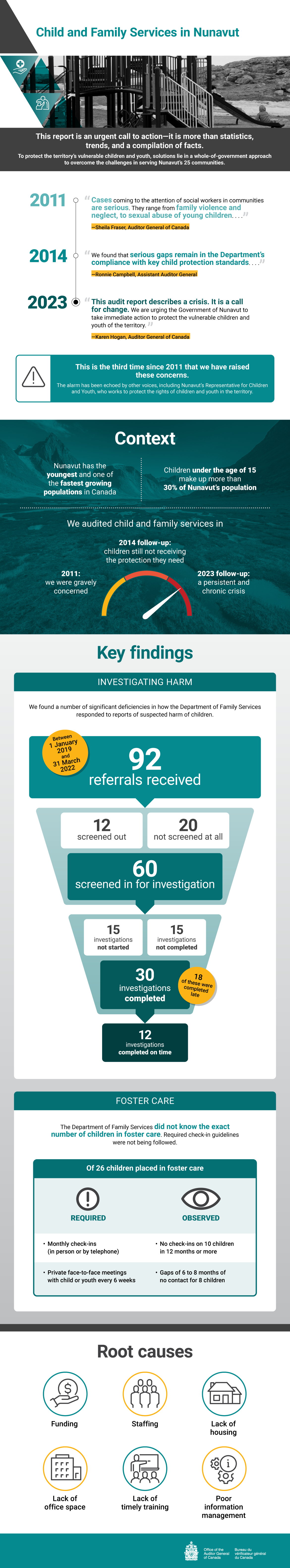

Child and Family Services in Nunavut

Image description for infographic about Child and Family Services in Nunavut

This report is an urgent call to action—it is more than statistics, trends, and a compilation of facts.

To protect the territory’s vulnerable children and youth, solutions lie in a whole-of-government approach to overcome the challenges in serving Nunavut’s 25 communities.

This is the third time since 2011 that we have raised these concerns:

- In 2011, Sheila Fraser, the Auditor General of Canada, said, “Cases coming to the attention of social workers in communities are serious. They range from family violence and neglect, to sexual abuse of young children. …”

- In 2014, Ronnie Campbell, Assistant Auditor General, said, “We found that serious gaps remain in the Department’s compliance with key child protection standards. …”

- In 2023, Karen Hogan, the Auditor General of Canada, said, “This audit report describes a crisis. It is a call for change. We are urging the Government of Nunavut to take immediate action to protect the vulnerable children and youth of the territory.”

The alarm has been echoed by other voices, including Nunavut’s Representative for Children and Youth, who works to protect the rights of children and youth in the territory.

Context

Nunavut has the youngest and one of the fastest growing populations in Canada.

Children under the age of 15 make up more than 30% of Nunavut’s population. That’s about 40,000 Nunavummiut.

We audited child and family services in 2011, 2014, and 2023:

- In our 2011 audit, we were gravely concerned.

- In our 2014 follow-up audit, we found that children were still not receiving the protection they need.

- In our 2023 follow-up audit, we found a persistent and chronic crisis.

Key findings

With respect to investigating harm, we found a number of significant deficiencies in how the Department of Family Services responded to reports of suspected harm of children.

We found that the following happened between 1 January 2019 and 31 March 2022:

- 92 referrals were received, of which 12 were screened out, 20 were not screened at all, and 60 required investigation.

- 15 investigations were not started, and 15 investigations were not completed.

- 30 investigations were completed, 18 of which were completed late.

- 12 investigations were completed on time.

With respect to foster care, we found that the Department of Family Services did not know the exact number of children in foster care. For those that it did follow, required check‑in guidelines were not being followed.

On a sample of 26 children placed in foster care, we found the following:

- Monthly check‑ins (in person or by telephone) were required. However, we found no check‑ins on 10 children for 12 months or more.

- Private face‑to‑face meetings with a child or youth every 6 weeks were required. However, we found gaps of 6 to 8 months of no contact for 8 children.

Root causes

They are as follows:

- funding

- staffing

- lack of housing

- lack of office space

- lack of timely training

- poor information management

Related information

Tabling date

- 30 May 2023

Related audits

- 2014 Report of the Auditor General of Canada to the Legislative Assembly of Nunavut

Follow-up Report on Child and Family Services in Nunavut—Department of Family Services - 2011 Report of the Auditor General of Canada to the Legislative Assembly of Nunavut

Children, Youth and Family Programs and Services in Nunavut