2023 Reports 5 to 9 of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of CanadaReport 5—Inclusion in the Workplace for Racialized Employees

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings and Recommendations

- Despite actions taken by the audited organizations, equity and inclusion outcomes for racialized employees were unknown

- Organizations did not sufficiently use data to explore why and how racialized employees were disadvantaged

- No actions were identified to address the design of systems and processes that handled complaints of racism

- Accountability for equity, diversity, and inclusion goals did not extend to all executives and managers

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- Recommendations and Responses

- Exhibits:

- 5.1—The 6 organizations had varied practices for using disaggregated survey results and data on representation, promotion, and retention

- 5.2—In all 6 organizations, a higher percentage of visible minority respondents than non‑visible minority respondents indicated in the 2018, 2019, and 2020 Public Service Employee Surveys that they were a victim of discrimination on the job

- 5.3—Using a sample of 3 organizations that met workforce availability estimates at the organizational level, we found that only the Department of Justice Canada met the rates within all of its occupational groups, regions, and branches

- 5.4—Workforce availability estimates were not always met for all levels within occupational groups, as of 31 March 2022

- 5.5—In the 6 organizations, a greater percentage of respondents from racialized groups compared with those who did not identify as racialized selected the least positive answers in the Public Service Employee Survey (2020 and 2022) questions regarding fear of reprisal

- 5.6—Performance agreements for executive and non‑executive managers were not always based on specific and measurable objectives and did not always demonstrate results for equity, diversity, and inclusion goals

- 5.7—The response rates for the 6 sampled organizations for the Public Service Employee Survey

Introduction

Background

5.1 Canada’s population is increasingly racialized. In 2000, Statistics Canada reported that 1 in 8 persons identified as racialized. In 2021, it was 1 in 4. As of 2022, Canada’s core public administration comprised 69 departments and agencies with a total of 236,000 employees, of which approximately 1 in 5 identified as a member of a visible minority.Definition 1

5.2 With the understanding that equality ought to be reflected within the public service workplace, in 1986, Parliament enacted the Employment Equity Act. This act was amended in 1995 and fully repealed when the current act came into force in 1996. The act, under review at the time of this audit, is designed to achieve equality in the workplace by correcting underrepresentation of the 4 designated groups,Definition 2 including members of visible minorities.

5.3 Every employer under the act is required to implement policies and practices and make reasonable accommodations to correct disadvantages that designated groups face in employment so that they achieve representation at levels similar to those in relevant segments of the broader Canadian workforce.

5.4 The Employment Equity Act requires federally regulated private sector employers and portions of the federal public sector to

- analyze their human resources systems, policies, and practices

- identify barriers or conditions of disadvantage in employment

- develop and implement a plan to remove these barriers and correct underrepresentation

- be held accountable for results

The act prescribes reporting on representation, and this data is based on voluntary self‑identification, meaning that public servants can choose whether or not to self‑identify; it is not mandatory.

5.5 Within the federal public service, various government‑wide task forces have been struck over the years, including in 2000 and again in 2016, to address gaps in representation of visible minorities and other designated groups. In June 2020, the Prime Minister characterized systemic racismDefinition 3 as an issue across the country and called upon the government to work at eradicating it.

5.6 In January 2021, the Clerk of the Privy Council and Secretary to the Cabinet issued a Call to Action on Anti‑Racism, Equity, and Inclusion in the Federal Public Service saying, “the time to act is now.” The Clerk called upon public service leaders to combat all forms of racism,Definition 4 discrimination, and other barriers to inclusion in the workplace. In turn, deputy heads were expected to respond transparently by outlining actions taken in their organizations and the early impacts of these efforts.

5.7 Barriers, or conditions of disadvantage, take different forms. They can be overt or subtle and can include everyday racism, denial or dismissal of harm and hardship resulting in different treatment, stalled opportunities for advancement when compared with non‑racialized colleagues, and underrepresentation at decision‑making tables. Everyday racism refers to day‑to‑day acts of interpersonal racism experienced by racialized people in workplaces and other environments.

5.8 Experiences of racism in the workplace negatively impact the workplace experience for racialized employees and cause harm, bringing with it the cost to employees’ mental and physical health. In Canada, the financial impacts and costs of mental health problems can be significant. In 2020, the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, a World Health Organization collaborating centre, estimated the economic burden of mental illness to be approximately $51 billion each year, with $6.3 billion resulting from lost productivity.

5.9 Six federal organizations that have responsibilities related to the delivery of front‑line services in Canada, providing safety, the administration of justice, or policing, are the focus of this audit. Together, they comprise approximately 21% of employees in the federal core public administration:

- Canada Border Services Agency. This agency provides integrated border services that support national security and public safety priorities and facilitates the free flow of persons and goods that meet all legislated requirements.

- Correctional Service Canada. This agency administers sentences of a term of 2 years or more, as imposed by the courts. It manages institutions of various security levels and supervises offenders under conditional release in the community.

- Department of Justice Canada. This department provides legal advisory, litigation, and legislative drafting services to the Government of Canada and federal government departments and agencies. The department develops policies, programs, and services as they relate to the administration of justice under the federal jurisdiction. The department also supports the Minister of Justice in advising the Cabinet on all legal matters. In addition, the Minister of Justice is responsible for a number of independent organizations, including the Canadian Human Rights Commission and the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal.

- Public Prosecution Service of Canada. This organization prosecutes federal offences and provides legal advice and assistance to law enforcement as a national, independent, and accountable prosecuting authority.

- Public Safety Canada. This department plays a leading role in the development, coordination, and implementation of policies and programs related to community safety, law enforcement, national security, emergency management, crime prevention, and other security and safety initiatives.

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). The RCMP contributes to the safety and security of Canadians by tackling crime at the municipal, provincial or territorial, federal, and international levels, including preventing and investigating crime, maintaining peace and order, enforcing laws, and providing vital operational support services to other police and law enforcement agencies.

5.10 The deputy heads of the 6 organizations are responsible and accountable for human resources management within their organizations. As the administrative arm of the Treasury Board, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat supports federal deputy heads and their departments and agencies in implementing government priorities and meeting citizens’ expectations of government. The Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer within the secretariat develops policy and provides strategic direction for managing people in the federal public service, including in employment equity, diversity, and inclusion.

Focus of the audit

5.11 This audit focused on whether actions and progress made in 6 organizations from 1 January 2018 to 31 December 2022 fostered an inclusive organizational culture and corrected the conditions of disadvantage in employment experienced by racialized employees.

5.12 The focus of this audit was on racialized employees and the actions taken by selected organizations to correct conditions of disadvantage in employment. However, the recommendations are expected to also benefit other employment equity groups. For example, the 2017 Many Voices One Mind: A Pathway to Reconciliation action plan initiated an all‑of‑government effort to reduce and remove barriers to federal public service employment encountered by Indigenous peoples.

5.13 This audit is important because the 6 organizations we audited have a responsibility to provide a work environment that is safe, respectful, inclusive, and free of racism. A representative and inclusive public service draws on the diverse perspectives and lived experiences of disproportionately disadvantaged groups, which in turn better informs decision making and service delivery that impact people.

5.14 To gain insight into the lived experience of racialized employees, the audit team engaged an independent third party to conduct individual interviews with volunteer racialized employees at the 6 audited organizations. These confidential interviews carried out by a team of racialized clinical psychologists are an important source of qualitative data about the lived experience of racialized employees. Major themes emerging from this data are shared in this audit report to illustrate the experiences and resulting harm that were shared with us by the volunteer racialized employees in the audited organizations.

5.15 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings and Recommendations

Despite actions taken by the audited organizations, equity and inclusion outcomes for racialized employees were unknown

5.16 This finding matters because actions alone are not sufficient to measure whether desired outcomes have been achieved. Indicators are needed to measure whether a situation has changed. Data specific to racialized employees, measured over time, communicated to employee networks, and used by decision makers is necessary to inform actions and provides indicators to track progress toward equity, diversity, and inclusion.

Strategies and action plans developed

5.17 We found that each of the 6 organizations developed its own plans to address equity, diversity, and inclusion according to its respective resources and priorities. No additional funding was provided to implement actions in response to the Call to Action on Anti‑Racism, Equity, and Inclusion in the Federal Public Service.

5.18 We found that between 2020 and 2022, the 6 organizations established multi‑year equity, diversity, and inclusion strategies or action plans, or both. The plans included a broad range of actions related to areas such as recruitment, promotion, retention, training, and integrating equity, diversity, and inclusion commitments in performance agreements for executives, managers, and supervisors.

5.19 We found that the Canada Border Services Agency developed a specific 2020–23 anti‑racism strategy. The strategy included guiding principles, expected changes to behaviours, and a clear acknowledgement that racism was a problem within the organization. The organization’s equity, diversity, and inclusion action plan guided early efforts to achieve the strategy’s vision and desired outcomes. Two other organizations—Correctional Service Canada and the Department of Justice Canada—also developed anti‑racism frameworks that helped guide their efforts to create an equitable and inclusive workplace.

5.20 Across the 6 organizations, we found that actions focused on achieving representation were based on meeting workforce availability. The federal core public administration uses workforce availability data as the benchmark to assess sufficient representation of the 4 designated employment equity groups in its workforce. While this data is based on labour market information obtained through the most recent Statistics Canada Census of Population and Canadian Survey on Disability and is adjusted for factors such as citizenship, location, age, and education, it can lag up to 8 years behind the demographic realities of Canadian society. For a growing racialized population, the risk can be underrepresentation in workforce availability data that in turn leads to understated representation goals.

5.21 We found that Correctional Service Canada and the Department of Justice Canada took an extra step and established their own organizational representation goals. Correctional Service Canada established goals based on a blend of workforce availability and the representation of the offender population. The Department of Justice Canada went even further and developed projected representation rates based on existing labour force projections produced by Statistics Canada, Canada’s national statistical agency. These projections were updated to address the lag in the reporting of demographic information. The projections became the new representation benchmarks for the organization in its 2022–25 employment equity plan.

No measurement of progress on equity and inclusion outcomes for racialized employees

5.22 We found that none of the organizations had both

- established clear indicators

- measured results that would allow them to compare equity and inclusion outcomes for racialized and non‑racialized groups

Clear indicators set out what changes are expected to improve equity and inclusion. Comparing outcomes of racialized employees with non‑racialized employees supports the measurement of change over time. In our opinion, a pathway toward achieving equity and inclusion would be co‑creating indicators with racialized employees, comparing the outcomes of racialized employees with non‑racialized employees, and reviewing quantitative results alongside qualitative data.

5.23 We found that the Canada Border Services Agency and the Department of Justice Canada had developed performance measurement indicators related to culture change and equity, diversity, and inclusion outcomes. Both organizations designed indicators to assess progress on a wide range of issues relevant to the work environment, such as discrimination, leadership and supervision, fairness and access to career development, and mental health. Both organizations also established quantitative outcome goals. However, neither organization had used the indicators to measure and report on results in such a manner as to be able to compare the outcomes for racialized employees with non‑racialized employees.

5.24 We also found that the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer did not issue guidance to organizations on the approach they should take for establishing equity and inclusion outcome indicators. The office is responsible for providing strategic direction and policies related to diversity, inclusion, and employment equity and for providing leadership and guidance on developing key performance indicators. Individual organizations would benefit from its centralized expertise. For example, developing a common set of measurable indicators would be more efficient than each organization doing this work independently. This is important because this would also allow for consistent monitoring of progress toward equity and inclusion outcomes across government.

5.25 The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat should provide guidance and share best practices that will help organizations establish performance indicators to measure and report on equity and inclusion outcomes in the federal public service. This should include at minimum

- a common set of measurable indicators that use reliable survey, organizational human resources, and other data

- indicators that show comparative results at the racialized employee group and subgroup levels against results for non‑racialized employees

The secretariat’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

5.26 Each of the 6 organizations, using the guidance and best practices we recommend the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat prepare, should implement performance measurement frameworks to assess and report on progress toward its equity and inclusion outcomes. Furthermore, each of the 6 organizations should develop and implement its performance measurement indicators and related benchmarks or comparator groups using an extensive and comprehensive approach driven by racialized employees, as they are the employees affected by racism in the workplace.

Response of each entity. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Lack of regular and comprehensive communication to employees on equity and inclusion

5.27 We found mixed communication practices by organization:

- The RCMP published 5 annual employment equity reports to all employees that included progress on selected actions and employment equity data.

- Both the Canada Border Services Agency and the Department of Justice Canada published a progress report in 2022 on some of the actions in their equity, diversity, and inclusion action plans and made some detailed employment equity data available to all their employees.

- Beginning in July 2022 at Correctional Service Canada and October 2022 at Public Safety Canada, quarterly dashboards containing employment equity data were published on their internal networks for all employees to access.

5.28 We found that all 6 organizations had provided their employees with information on selected activities, as well as various tools and resources related to equity, diversity, and inclusion. However, by the end of our audit period, we did not find any instances where a complete report on action plan progress and results was provided to all employees. We found that the Department of Justice Canada published a communication plan in its 2022–25 employment equity plan, released in August 2022. Communication under this plan had not commenced during the audit period.

5.29 This lack of complete and comprehensive reporting was a missed opportunity to keep employees engaged and informed of progress, as well as to demonstrate accountability for results. In our opinion, because a change in culture rests on a change in behaviours and beliefs, it is essential that all employees, and especially those who are members of racialized employee networks, receive regular and comprehensive updates on progress achieved to reinforce the need for and achievement of change.

5.30 A major theme emerged from the confidential interviews conducted with racialized employees. They felt there was a lack of commitment to equity, diversity, and inclusion, and there was a perception that meaningful change was not being achieved. Some employees reported that they did not know the status of initiatives from action plans or what progress toward outcomes had been made. As a result, many believed that equity was an empty word in their organizations, and plans and committees were devoid of the potential to bring about meaningful changes.

5.31 So that all employees are meaningfully informed of and engaged in how the work environment is changing, the Canada Border Services Agency, Correctional Service Canada, the Public Prosecution Service of Canada, Public Safety Canada, and the RCMP should have either communication plans or reporting frameworks that provide all employees with regular and comprehensive updates of measurable progress toward desired equity and inclusion outcomes. Communication plans should include updates on both quantitative and qualitative results.

Response of each entity. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Organizations did not sufficiently use data to explore why and how racialized employees were disadvantaged

5.32 This finding matters because access to accurate and timely human resources data to monitor trends and compare them with other available data is required for organizations to identify the impacts of biases and other disadvantages experienced by racialized employees at different levels and throughout an organization. With that knowledge, organizations will be able to concentrate their efforts on removing barriers and taking action to eliminate disadvantages to establish benchmarks and measure improvements over time.

5.33 Using only quantitative data—information that can be counted or measured in numerical values—can be limiting when seeking to understand human experiences. Its use can be helpful to identify where problems exist and to measure progress over time. However, it is more illuminating when used alongside other sources of information. Qualitative data—information that approximates and characterizes—can be collected by way of interviews, case studies, and focus groups.

5.34 The Clerk of the Privy Council and Secretary to the Cabinet’s Call to Action on Anti‑Racism, Equity, and Inclusion in the Federal Public Service in 2021 stressed that disaggregated data—data broken out from the overall organizational results to show results for groups such as racialized employees—would help public service leaders to “understand where gaps exist and to inform direction and decisions.” It further stated that creating “a sense of belonging and trust for all public servants” included “measuring progress and driving improvements in the employee workplace experience by monitoring disaggregated survey results and related operational data (for example, promotion and mobility rates, tenure) and acting on what the results are telling us.” This is consistent with legislated requirements from the Employment Equity Act to collect and analyze data on the employer’s workforce. The importance of measuring progress was also reiterated in the Clerk’s forward direction message issued to deputy heads following the end of our audit period in May 2023.

Limited analysis of data specific to racialized employees

5.35 We found that opportunities for improvements could be made by all of the organizations with respect to their practices for using disaggregated survey results and related operational, or human resources, data. We found that none of the organizations examined performance rating distribution or tenure rates for employment equity groups. We also found that not all organizations examined survey results and representation, promotion, and retention data at the lowest possible disaggregated levels (Exhibit 5.1).

Exhibit 5.1—The 6 organizations had varied practices for using disaggregated survey results and data on representation, promotion, and retention

| Results and data that the organization’s internal dashboards, analyses, or reports showed | Canada Border Services Agency | Correctional Service Canada | Department of Justice Canada | Public Prosecution Service of Canada | Public Safety Canada | Royal Canadian Mounted Police |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public Service Employee Survey results by employment equity group |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

| Public Service Employee Survey results by employment equity group and comparator (member of visible minority versus not a member of an employment equity group) |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

| Public Service Employee Survey results analyzed by employment equity subgroup |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Representation data by employment equity group and subgroup |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

| Representation data by employment equity group compared with workforce availability estimates by branch or region |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

| Representation data by employment equity group compared with workforce availability estimates by occupational groups |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Promotion data by employment equity group compared with representation |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

| Promotion data by employment equity subgroup compared with representation |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Promotion data by employment equity group and comparator (member of visible minority versus not a member of an employment equity group) |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Retention data by employment equity group compared with representation |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

| Retention data by employment equity subgroup compared with representation |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Retention data by employment equity group and comparator (member of visible minority versus not a member of an employment equity group) |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

Source: Based on information from the 6 audited organizations

5.36 In addition, we found that none of the 6 audited organizations compared Public Service Employee Survey results for racialized employees with data from multiple other sources, such as human resources data, data on complaints, or results from exit interviews. We also found that not all organizations compared survey results and human resources data for racialized employees and subgroups with employees who do not identify as racialized (Exhibit 5.1).

5.37 We found that long‑known problems with the quality of the organizations’ information technology infrastructure, in particular human resources systems and reporting tools, continued to affect the quality and availability of data. This affected the efficiency and quality of the analysis completed by the 6 organizations, as well as our own audit work. Several government‑wide initiatives are underway to address these issues. For example, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat is leading the implementation of a new self‑identification process and centralized employment equity data collection and reporting initiative. In the interim, the Department of Justice Canada implemented in February 2022 its own updated self‑identification system to improve access to and use of employment equity data.

5.38 We provide further analysis of each organization’s use of Public Service Employee Survey results, representation data, and performance assessment ratings in paragraphs 5.39 to 5.49.

5.39 Public Service Employee Survey data. We found that in order to understand the overall workplace environment for their employees, all 6 organizations reviewed survey results. In addition, each organization with the exception of the RCMP provided us with evidence of survey results analyzed by employment equity groups.

5.40 Correctional Service Canada provided the best example of survey analysis presented to management that compared 2020 survey results of racialized employees with non‑racialized employees and showed the results over time. This was a good practice because it provided the organization with more insight into the existence of inequalities faced by racialized employees and illustrated the important differences reported across employee groups. For example, only 55% of its visible minority survey respondents reported that they felt free to speak about racism in the workplace without fear of reprisal, compared with the 67% who felt that way across the whole organization. That percentage dropped again to 44% when reviewing the responses of the Black visible minority subgroup who felt free to speak about racism.

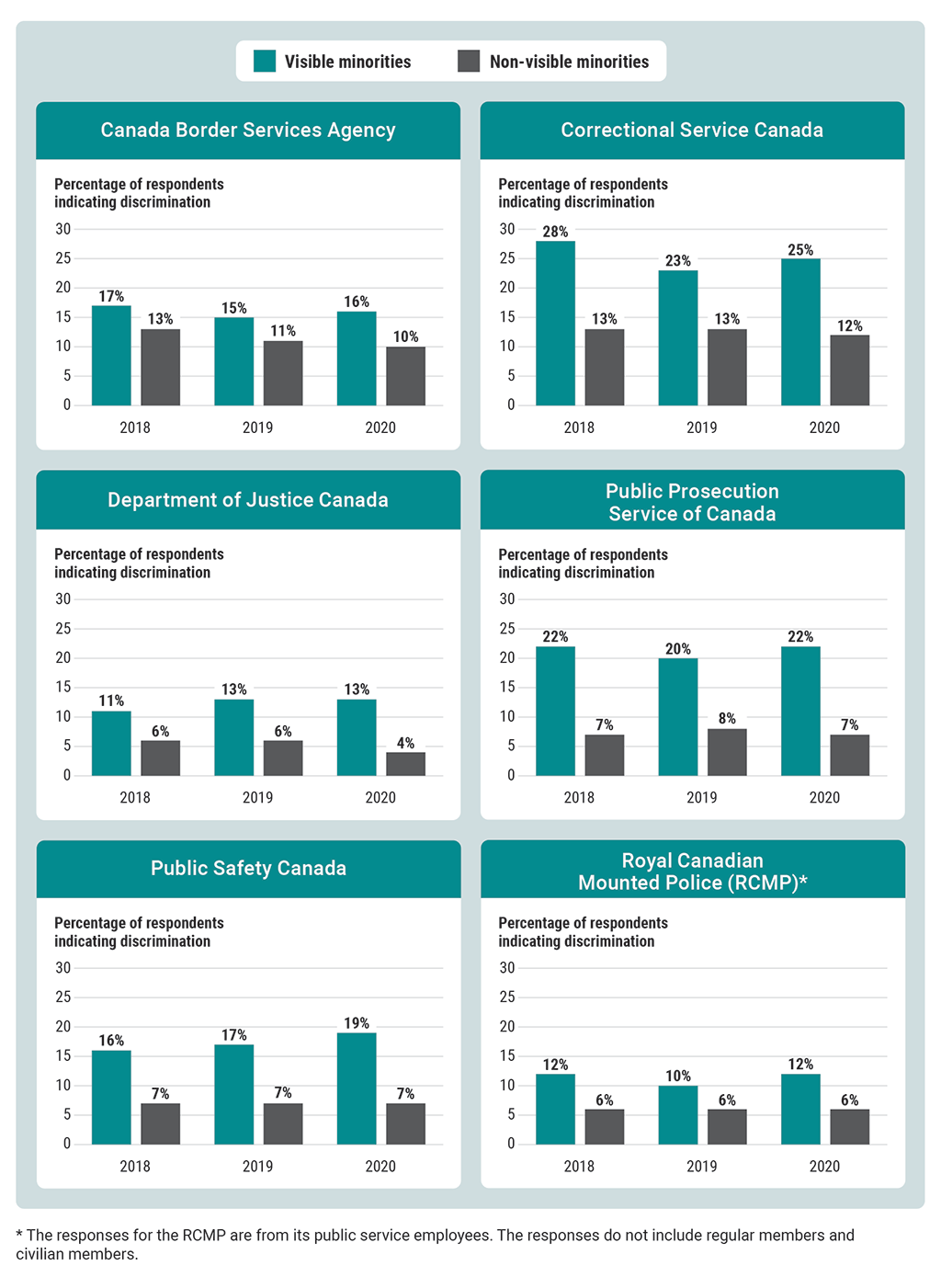

5.41 We examined data from 2018 to 2020 for the 6 organizations from the survey regarding the question of whether employees had experienced acts of discriminationDefinition 5 on the job. We found that racialized employees reported rates of discrimination at least 30% higher than respondents who were not racialized (Exhibit 5.2). Such comparisons should act as alarms for leadership that problems impacting racialized employees exist and immediate actions are needed. They can also serve as indicators of progress when measured over time.

Exhibit 5.2—In all 6 organizations, a higher percentage of visible minority respondents than non‑visible minority respondents indicated in the 2018, 2019, and 2020 Public Service Employee Surveys that they were a victim of discrimination on the job

Note: Respondents self‑identified and answered the question: “Having carefully read the definition of discrimination, have you been the victim of discrimination on the job in the past 12 months?”

Source: Based on data from the 2018, 2019, and 2020 Public Service Employee Surveys

Exhibit 5.2—text version

This chart shows the percentage of respondents of the 2018, 2019, and 2020 Public Service Employee Surveys who indicated discrimination at the 6 audited organizations. Respondents self-identified and answered the question: “Having carefully read the definition of discrimination, have you been the victim of discrimination on the job in the past 12 months?” The percentage of respondents indicating discrimination was higher for visible minorities than for non‑visible minorities in all 6 organizations.

At the Canada Border Services Agency, the percentage of respondents indicating discrimination was as follows.

| Respondents | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visible minorities | 17% | 15% | 16% |

| Non-visible minorities | 13% | 11% | 10% |

At Correctional Service Canada, the percentage of respondents indicating discrimination was as follows.

| Respondents | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visible minorities | 28% | 23% | 25% |

| Non-visible minorities | 13% | 13% | 12% |

At the Department of Justice Canada, the percentage of respondents indicating discrimination was as follows.

| Respondents | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visible minorities | 11% | 13% | 13% |

| Non-visible minorities | 6% | 6% | 4% |

At the Public Prosecution Service of Canada, the percentage of respondents indicating discrimination was as follows.

| Respondents | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visible minorities | 22% | 20% | 22% |

| Non-visible minorities | 7% | 8% | 7% |

At Public Safety Canada, the percentage of respondents indicating discrimination was as follows.

| Respondents | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visible minorities | 16% | 17% | 19% |

| Non-visible minorities | 7% | 7% | 7% |

At the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, the percentage of respondents indicating discrimination was as follows. The responses are from its public service employees. The responses do not include regular members and civilian members.

| Respondents | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visible minorities | 12% | 10% | 12% |

| Non-visible minorities | 6% | 6% | 6% |

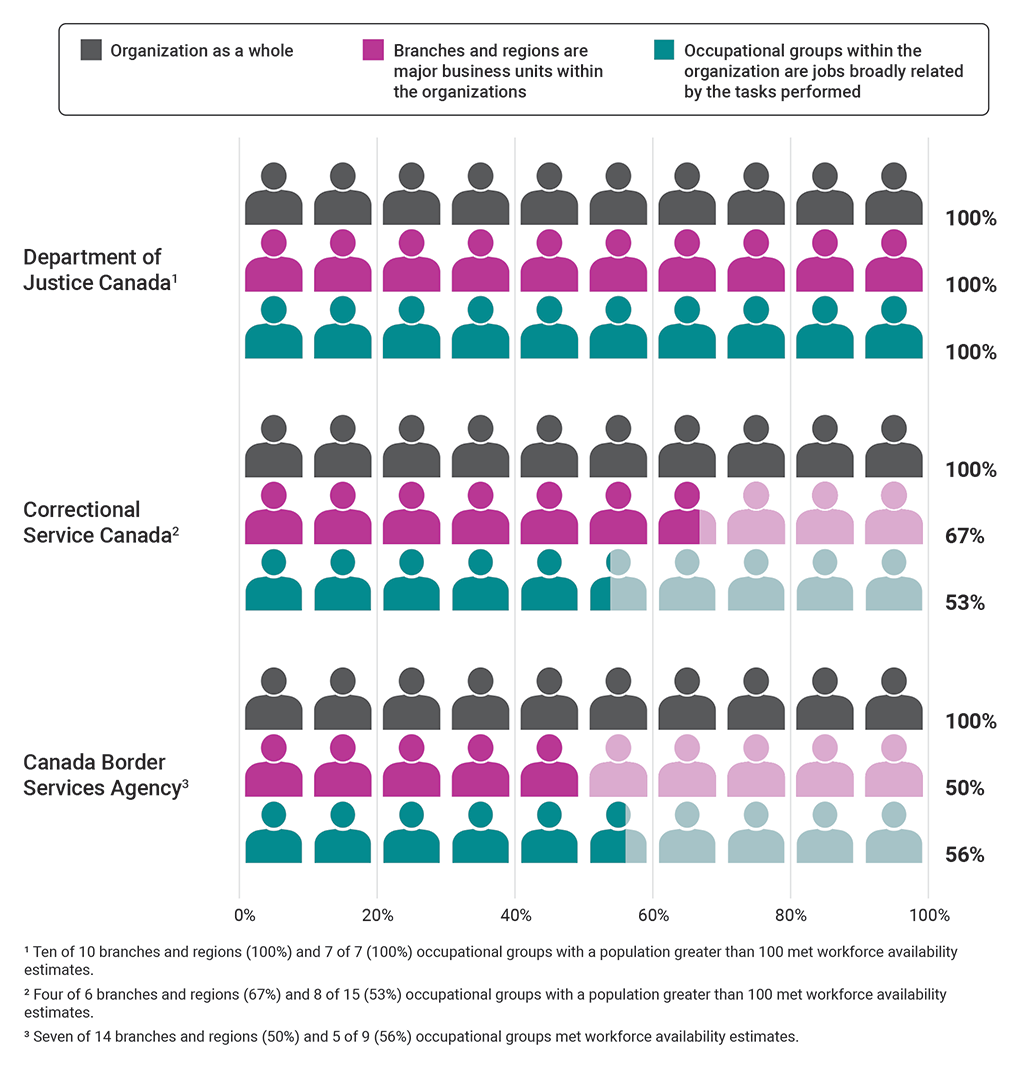

5.42 Human resources data—Representation. We found that only the RCMP did not meet workforce availability representation goals for the overall level of organizational reporting. While the other 5 organizations met workforce availability representation goals, there were sometimes gaps deeper in an organization, at a regional and branch level (Exhibit 5.3). For example, the Department of Justice Canada met all of its branch and regional representation goals. Correctional Service Canada met its goals for 4 of 6 branches and regions, and the Canada Border Services Agency met its goals for 7 of 14 branches and regions.

Exhibit 5.3—Using a sample of 3 organizations that met workforce availability estimatesNote * at the organizational level, we found that only the Department of Justice Canada met the rates within all of its occupational groups, regions, and branches

Note: Populations of greater than 100 per occupational group, branch, and region were selected to maintain privacy of respondents. Due to the small number of such populations at the Public Prosecution Service of Canada and Public Safety Canada, they were excluded from the sample.

Source: Based on data from the Department of Justice Canada, Correctional Service Canada, and the Canada Border Services Agency

Exhibit 5.3—text version

This illustration shows the workforce availability rates at the Department of Justice Canada, Correctional Service Canada, and the Canada Border Services Agency. These organizations as a whole met workplace availability estimates.

Workforce availability estimates indicate the percentage of racialized people who are in the labour force in a region, including all of Canada. The estimates are compiled on a 5‑year cycle using Census and labour market availability data.

For each of the 3 organizations, the rates within regions and branches and within occupational groups are shown. Branches and regions are major business units within the organizations. Occupational groups within the organization are jobs broadly related by the tasks performed.

At the Department of Justice Canada, 10 of 10 branches and regions, or 100%, and 7 of 7 occupational groups with a population greater than 100, or 100%, met workforce availability estimates.

At Correctional Service Canada, 4 of 6 branches and regions, or 67%, and 8 of 15 occupational groups with a population greater than 100, or 53%, met workforce availability estimates.

At the Canada Border Services Agency, 7 of 14 branches and regions, or 50%, and 5 of 9 occupational groups, or 56%, met workforce availability estimates.

5.43 We also found that goals were not always achieved within an organization’s occupational groups—jobs related by the nature of the functions performed (Exhibit 5.3). For example, while all of the Department of Justice Canada occupational groups met representation goals, Correctional Service Canada met representation goals for 8 of 15 occupational groups and the Canada Border Services Agency met 5 of 9 representation goals for its occupational groups.

5.44 In the confidential interviews, racialized employees expressed that barriers and other disadvantages in employment caused by racism were felt to be more pronounced in certain regions or branches as well as within different occupational groups and levels. Analyzing representation data in comparison to workforce availability estimates or other representation goals established by organizations can help identify where barriers and disadvantages may be encountered.

5.45 In the confidential interviews, racialized employees also communicated that they were being left out of higher levels within occupational groups in their organizations and instead remained in occupational groups and levels with lower pay and less influence compared with non‑racialized employees. We found that only the Department of Justice Canada conducted analysis on this topic as part of its 2020–22 employment equity plan progress report. We did our own analysis of the largest occupational group in each of the 6 organizations and found that workforce availability estimates were not always met at the low, mid, and high levels within occupational groups (Exhibit 5.4). Conducting further analysis into the cause behind this result, including consideration of other relevant quantitative data—such as hiring, promotion, and retention rates—and qualitative data would help the 6 organizations understand what conditions led to this result and what steps could be taken to correct them.

Exhibit 5.4—Workforce availability estimates were not always met for all levels within occupational groups, as of 31 March 2022

| Organization | Largest occupational group in the organization | Workforce availability met (occupational group) |

Workforce availability met (low-level) |

Workforce availability met (mid-level) |

Workforce availability met (high-level) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada Border Services Agency | Border services group | Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

| Correctional Service Canada | Correctional service officers | Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Department of Justice Canada | Lawyers | Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

| Public Prosecution Service of Canada | Lawyers | Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

| Public Safety Canada | Policy and research analysts | No |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

| Royal Canadian Mounted Police | Police officers | No |

No |

No |

No |

Source: Based on information from the 6 audited organizations

5.46 Human resources data—Performance assessments. We found that none of the 6 organizations completed a comparative analysis of the distribution of performance assessment ratings for racialized employees with non‑racialized employees. In our view, this analysis is important to uncover whether any disparities exist in how performance assessments are conducted and career advancement is achieved for racialized employees.

5.47 We found that the Canada Border Services Agency was the only organization to have initiated an analysis of performance assessment trends based on employment equity groups. This work began in 2022, and it was not yet completed by the end of our audit period. Although none of the organizations had completed such analysis, we examined selected data from the performance assessment results for the 2021–22 fiscal year for 5 of the 6 organizations. The RCMP could not provide the data required to conduct the analysis because its human resources systems did not capture performance assessment ratings data.

5.48 In our analysis, we found there was a mixed result across performance assessment distribution. For example, we found that among the executive groups at the Canada Border Services Agency and Public Safety Canada, performance assessments were 6 and 7 percentage points higher, respectively, for racialized employees compared with the non‑racialized employees in the highest rating categories: succeeded plus and surpassed. However, at the Department of Justice Canada, we found that performance assessments for racialized employees were 6 percentage points lower than for non‑racialized employees in the same categories.

5.49 Detailed analysis of performance assessment trends based on employment equity groups provides insights into systemic practices and individual biases that can make it more difficult for racialized employees to advance in their careers. In the confidential interviews, racialized employees raised that systemic barriers caused by racism impacted equitable hiring and advancement of racialized employees in all 6 organizations.

5.50 All 6 organizations should undertake data‑informed analysis to understand how racialized employees experience their workplace in comparison with others. By using quantitative data together with qualitative data, such as the lived experiences of racialized employees and other designated groups, organizations should take concrete and measurable actions to correct situations of employment disadvantage.

Response of each entity. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

No actions were identified to address the design of systems and processes that handled complaints of racism

5.51 It is important that all employees feel safe and free to voice concerns regarding racism in the workplace without fear. Racialized employees face a unique challenge that stems from a power imbalance derived from being a historically disadvantaged group. This places racialized employees at an inherent disadvantage when faced with the decision to file a complaint against a non‑racialized employee.

5.52 When racialized employees have access to a fair and safe organizational culture in which everyday racism is considered in the complaint processes, the risk of continued harm is reduced.

5.53 As an employer for federal employees in the core public administration, the Treasury Board, supported by the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer within the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, is responsible for setting policies with respect to people management. The current Policy on People Management, issued in 2021, delegated to deputy heads the responsibility to create and maintain a respectful and fair workplace while safeguarding the health and safety of their workforce and workplace. Additionally, under the Work Place Harassment and Violence Prevention Regulations, employers are required to develop a workplace harassment and violence prevention policy.

5.54 The Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer provides people management leadership to deputy heads and heads of human resources with regard to human resources management matters that fall within the Treasury Board’s authority. This includes any associated tools, systems, and oversight, including reporting cycles, such as the annual report on employment equity in the public service.

No specific initiatives in action plans to address concerns and complaints related to barriers to raising instances of racism

5.55 We found that there were various complaint resolution processes in all 6 of the organizations. They included

- informal conflict resolution processes

- grievance processes as outlined in collective agreements or terms and conditions of employment

- processes for handling and preventing harassment and violence in the workplace

We did not find any specific action undertaken to address concerns regarding barriers to raising issues or making complaints relating to conditions of disadvantage of racialized employees, including instances of racism.

5.56 Our analysis of the 2018, 2019, 2020, and 2022 Public Service Employee Survey results showed that respondents from all 6 organizations who indicated that they experienced either harassment or discrimination were most likely to respond that they experienced harassment or discrimination from someone with authority over them or a colleague. The 2 most common approaches taken by those respondents were to discuss the matter with their supervisors or senior managers or to take no action. When the survey question asked why they did not file a grievance or a formal complaint, the most common answers were that they were afraid of reprisal or did not believe it would make a difference.

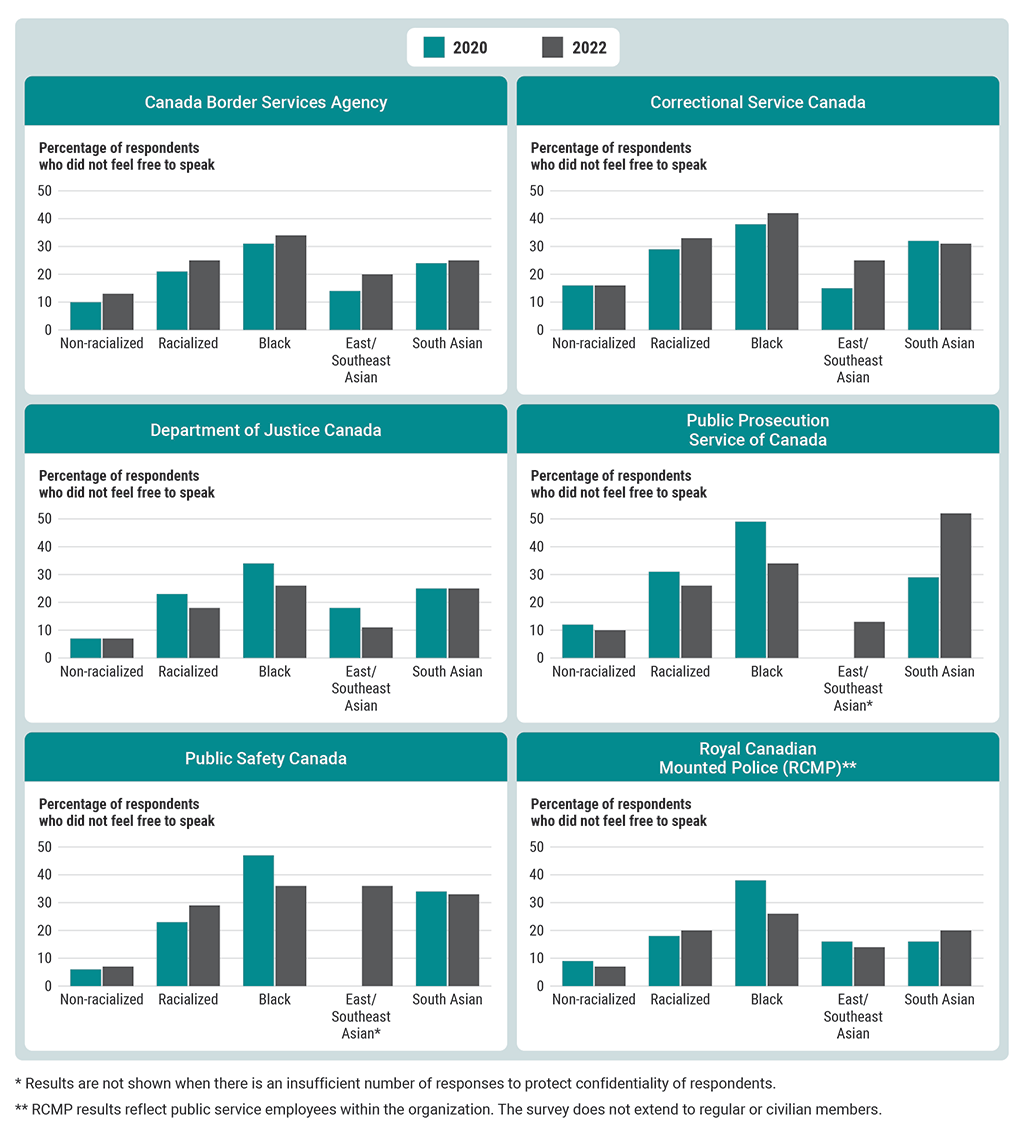

5.57 An analysis of the 2020 and 2022 surveys showed that in the 6 organizations, a greater percentage of racialized respondents than non‑racialized respondents indicated that they did not feel free to speak about racism in the workplace without fear of reprisal (Exhibit 5.5). A further disaggregated examination of the results for the 3 largest racialized subgroups also revealed differences between results, with respondents identifying as Black reporting the most negative results. These differences highlight the importance of examining results by different racialized groups, as perceptions and lived experiences are not all the same.

Exhibit 5.5—In the 6 organizations, a greater percentage of respondents from racialized groups compared with those who did not identify as racialized selected the least positive answers in the Public Service Employee Survey (2020 and 2022) questions regarding fear of reprisal

Note: In 2022, respondents self‑identified as belonging to a racial group or not. They answered the question: “In my work unit, I would feel safe to speak about racism in the workplace without fear of reprisal or negative impact on my career.” The exhibit shows the negative responses to the question: In other words, the respondents did not feel safe to speak about racism in the workplace without fear of reprisal or negative impact on their career.

In 2020, respondents self‑identified as belonging to a visible minority group or not and answered the question: “In my work unit, I would feel free to speak about racism in the workplace without fear of reprisal.” The exhibit shows the negative responses to the question: In other words, the respondents did not feel free to speak about racism in the workplace without fear of reprisal.

Source: Based on data from the 2020 and 2022 Public Service Employee Surveys

Exhibit 5.5—text version

This chart shows the percentage of racialized and non‑racialized respondents of the 2020 and 2022 Public Service Employee Surveys who did not feel free to speak about racism in the workplace without fear of reprisal at the 6 audited organizations. Also shown are the results for the 3 largest racialized subgroups: Black, East/Southeast Asian, and South Asian.

In 2022, respondents self‑identified as belonging to a racial group or not. They answered the question: “In my work unit, I would feel safe to speak about racism in the workplace without fear of reprisal or negative impact on my career.” The exhibit shows the negative responses to the question: In other words, the respondents did not feel safe to speak about racism in the workplace without fear of reprisal or negative impact on their career.

In 2020, respondents self-identified as belonging to a visible minority group or not and answered the question: “In my work unit, I would feel free to speak about racism in the workplace without fear of reprisal.” The exhibit shows the negative responses to the question: In other words, the respondents did not feel free to speak about racism in the workplace without fear of reprisal.

At all 6 organizations, a greater percentage of respondents from racialized groups compared with those who did not identify as racialized selected the least positive answers in the survey questions regarding fear of reprisal.

At the Canada Border Services Agency, the percentage of respondents indicating discrimination is as follows.

| Respondents | 2020 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| Non-racialized | 10% | 13% |

| Racialized | 21% | 25% |

| Black | 31% | 34% |

| East/Southeast Asian | 14% | 20% |

| South Asian | 24% | 25% |

At Correctional Service Canada, the percentage of respondents indicating discrimination is as follows.

| Respondents | 2020 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| Non-racialized | 16% | 16% |

| Racialized | 29% | 33% |

| Black | 38% | 42% |

| East/Southeast Asian | 15% | 25% |

| South Asian | 32% | 31% |

At the Department of Justice Canada, the percentage of respondents indicating discrimination is as follows.

| Respondents | 2020 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| Non-racialized | 7% | 7% |

| Racialized | 23% | 18% |

| Black | 34% | 26% |

| East/Southeast Asian | 18% | 11% |

| South Asian | 25% | 25% |

At the Public Prosecution Service of Canada, the percentage of respondents indicating discrimination is as follows. Results are not shown when there is an insufficient number of responses to protect confidentiality of respondents.

| Respondents | 2020 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| Non-racialized | 12% | 10% |

| Racialized | 31% | 26% |

| Black | 49% | 34% |

| East/Southeast Asian | Not shown | 13% |

| South Asian | 29% | 52% |

At Public Safety Canada, the percentage of respondents indicating discrimination is as follows. Results are not shown when there is an insufficient number of responses to protect confidentiality of respondents.

| Respondents | 2020 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| Non-racialized | 6% | 7% |

| Racialized | 23% | 29% |

| Black | 47% | 36% |

| East/Southeast Asian | Not shown | 36% |

| South Asian | 34% | 33% |

At the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, the percentage of respondents indicating discrimination is as follows. Results reflect public service employees within the organization. The survey does not extend to regular or civilian members.

| Respondents | 2020 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| Non-racialized | 9% | 7% |

| Racialized | 18% | 20% |

| Black | 38% | 26% |

| East/Southeast Asian | 16% | 14% |

| South Asian | 16% | 20% |

5.58 In the confidential interviews, racialized employees shared many examples of experiences when they reported instances of racism to their managers, and their complaints were either diminished or denied on the basis of their managers’ subjective interpretation of racism. Others shared a deep fear of retaliation on the part of their managers or colleagues if they were to raise the issue of racist behaviour, resulting in their choosing not to report the incident in order to avoid the possibility of additional harm. Denying and diminishing concerns of racism can dissuade employees from making a complaint. This can result in a systemic racial power imbalance that perpetuates racist behaviour and can silence the people experiencing it.

5.59 We examined what actions the 6 organizations had taken to promote an environment in which complaints of racism could be raised without fear of reprisal. We also looked at whether, based on complaints and other evidence of concerns related to racism, steps were taken in an appropriate manner that addressed conditions of disadvantage of racialized employees, including racism and the denial of it. We examined the 6 organizations’ equity, diversity, and inclusion and other relevant action plans to determine whether they had identified initiatives that would address these concerns.

5.60 We did not find any specific actions undertaken to address concerns of racialized employees with respect to raising complaints. The Canada Border Services Agency had identified an initiative in its equity, diversity, and inclusion action plan for a reconciliation process that would help management and employees to address issues that occurred within a team, but work had not yet begun.

5.61 We found that managers and staff designated to receive complaints through the informal conflict resolution process were required to take mandatory training for violence and harassment in the workplace, but there was no training specific to recognizing and handling complaints of racism. Without specialized training, there is a risk that those receiving a complaint could diminish or deny the racism because they do not recognize it as racism. There is also a risk that they could recommend a complaint resolution option that does not consider the power imbalance for a racialized employee making a complaint of racism against a white employee, resulting in another barrier to the resolution and prevention of racism.

5.62 We found that the 6 organizations did not track data on all complaints that would allow them to monitor trends over time, examine the nature of complaints, or observe patterns in the profile of the individuals who bring forward complaints and against whom the complaints are made. As a result, this limited the organizations’ ability to use the data that they had to conduct root‑cause analyses based on various sources of complaint resolution and identify and correct racism faced by racialized employees.

5.63 In addition, we did not find evidence that the guidance or best practices issued by the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer regarding informal complaint processes included the collection, analysis, and reporting of informal complaint data. The use of complaint data in a manner that protects the confidentiality of the parties involved would help organizations to uncover the root causes of conflicts, to prioritize actions and resolve sources of harm to racialized employees, and to prevent future occurrences.

5.64 In the confidential interviews, racialized employees shared the negative impacts on their careers of working in an environment in which they feared reprisal when they attempted to speak up against racism. Every employee who was interviewed said they had experienced mental health impacts of everyday racism in the workplace, such as stress, low self‑esteem, anxiety, depression, trauma, or hopelessness. For the most part, the employees reported they felt it was essential to tough it out so their job performance would not be affected and because they did not want to provide any reasons to be further mistreated.

5.65 In our opinion, acknowledging everyday racism as a form of unacceptable behaviour could provide an important measure of support for racialized employees raising racism complaints and concerns.

5.66 All 6 organizations, supported by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, should examine their existing complaint resolution processes and ensure that these processes specifically address instances of racism in the workplace and that complaints are received and managed by professionals trained and experienced in the area of racism.

Response of each entity. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

5.67 All 6 organizations, supported by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, should collect and analyze information gathered through complaint resolution processes to identify root causes of disadvantage for racialized employees. Analysis of this information should contribute to preventing and resolving racism in the workplace.

Response of each entity. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Accountability for equity, diversity, and inclusion goals did not extend to all executives and managers

5.68 This finding matters because executives and managers lead and influence an organization’s efforts and direction and have the authority to make decisions that impact employees. Performance management processes and sufficient and appropriate education and training that set expectations for desired behaviour and outcomes are important to foster a culture of accountability for results.

5.69 In accordance with the Directive on Performance Management, performance agreements in the core public administration must include

- clear and measurable work objectives, with associated performance measures, that are linked to the priorities of the organization and of the Government of Canada

- observable and measurable expected behaviours

- a learning and development plan

5.70 Deputy heads establish annual commitments that are expected to cascade throughout their organizations. In the 2021 Call to Action on Anti‑Racism, Equity, and Inclusion in the Federal Public Service, the Clerk of the Privy Council and Secretary to the Cabinet identified key expectations in terms of deputy ministers’ commitments to equity, diversity, and inclusion. The call to action demanded collective responsibility for change at all levels and set expectations that progress would be measured and lessons learned would be shared.

5.71 In support of individual and collective change, training is often identified as a solution. Training is important because it provides organizations with an opportunity to create awareness and improve skills, as well as establish clear expectations with respect to desired behaviours in the workplace. However, training alone will not bring about desired change to behaviours and culture. When complemented by other diversity initiatives, such as personal readings and experiential learning, and recurring over a significant period of time, training is more effective in developing knowledge and skills.

Lack of measurable equity, diversity, and inclusion results in executive and non‑executive manager performance agreements

5.72 All 6 organizations told us that individual accountability for equity, diversity, and inclusion goals was assessed as part of the performance management process

- against a competency related to integrity and respect

- against the achievement of stated work objectives

- against the specific commitments established by deputy ministers for their organizations

The key leadership competencies used for managers in the federal core public administration were developed by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. The RCMP developed its own competency framework for its regular and civilian members. Work objectives were set at the organizational level for all 6 organizations.

5.73 We used representative sampling of executive and non‑executive manager performance agreements for the 2021–22 fiscal year to determine the extent to which accountability of individuals in supervisory positions was assessed in each of the 6 organizations. Nearly 100% of executives in all 6 organizations included performance objectives that created individual accountability for equity, diversity, and inclusion goals because of the expectation to incorporate the deputy head commitments established for their organizations into their performance agreements. We found that the objectives were not always specific and measurable, nor did they demonstrate a clear outcome (Exhibit 5.6).

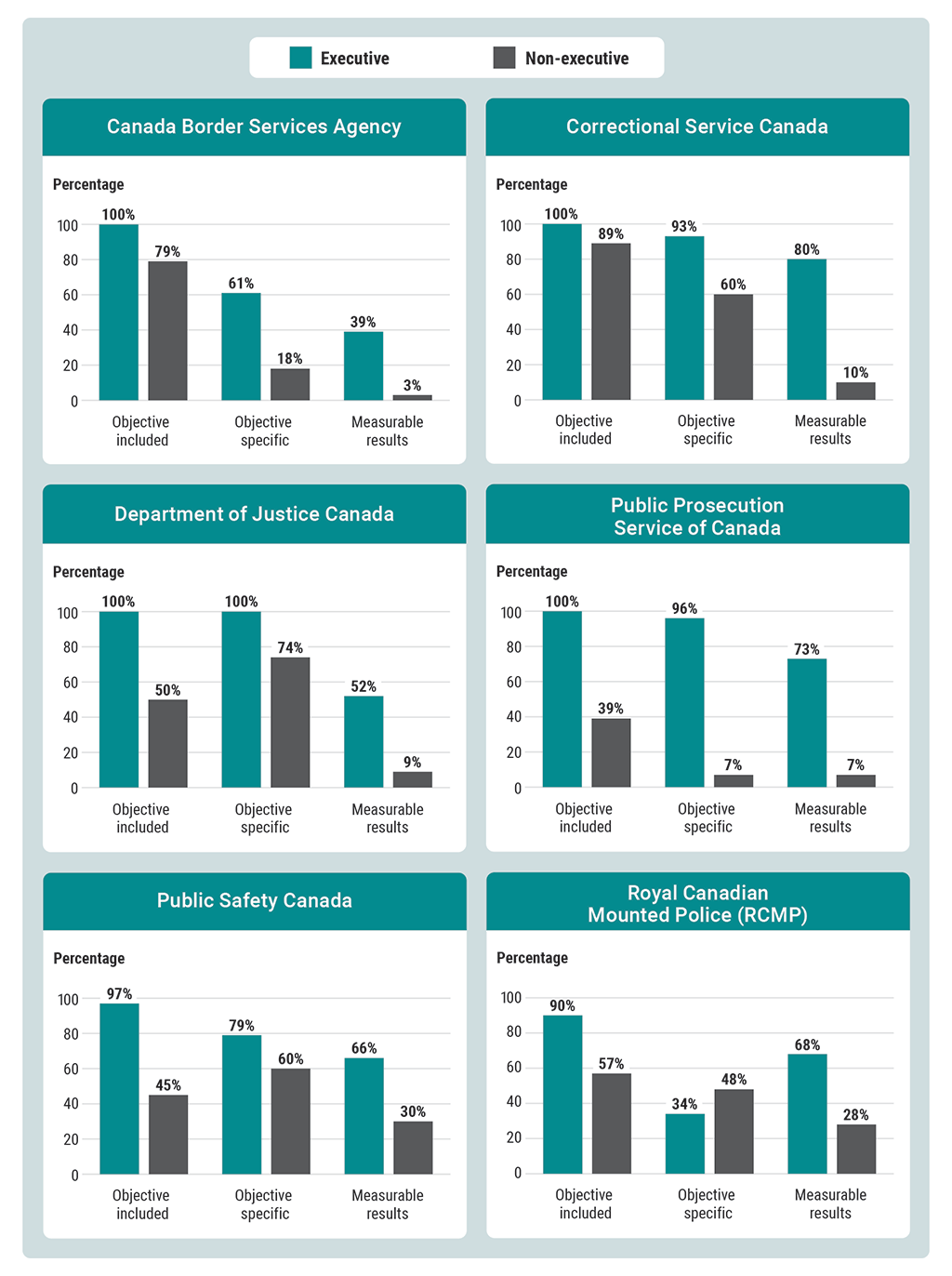

Exhibit 5.6—Performance agreements for executive and non‑executive managers were not always based on specific and measurable objectives and did not always demonstrate results for equity, diversity, and inclusion goals

Source: Based on data from the 6 audited organizations

Exhibit 5.6—text version

This chart shows the percentage of executive and non-executive performance agreements at the 6 audited organizations that included objectives, that had specific objectives, and that had measurable results. Nearly all executive agreements included objectives, but they were not always specific or did not always have measurable results. Non-executive agreements fell below the executive results.

At the Canada Border Services Agency, the percentage of performance agreements that included objectives was 100% for executive managers and 79% for non‑executive managers. The percentage of performance agreements that had specific objectives was 61% for executive managers and 18% for non‑executive managers. The percentage of performance agreements with measurable results was 39% for executive managers and 3% for non‑executive managers.

At Correctional Service Canada, the percentage of performance agreements that included objectives was 100% for executive managers and 89% for non‑executive managers. The percentage of performance agreements that had specific objectives was 93% for executive managers and 60% for non‑executive managers. The percentage of performance agreements with measurable results was 80% for executive managers and 10% for non‑executive managers.

At the Department of Justice Canada, the percentage of performance agreements that included objectives was 100% for executive managers and 50% for non‑executive managers. The percentage of performance agreements that had specific objectives was 100% for executive managers and 74% for non‑executive managers. The percentage of performance agreements with measurable results was 52% for executive managers and 9% for non‑executive managers.

At the Public Prosecution Service of Canada, the percentage of performance agreements that included objectives was 100% for executive managers and 39% for non‑executive managers. The percentage of performance agreements that had specific objectives was 96% for executive managers and 7% for non‑executive managers. The percentage of performance agreements with measurable results was 73% for executive managers and 7% for non‑executive managers.

At Public Safety Canada, the percentage of performance agreements that included objectives was 97% for executive managers and 45% for non‑executive managers. The percentage of performance agreements that had specific objectives was 79% for executive managers and 60% for non‑executive managers. The percentage of performance agreements with measurable results was 66% for executive managers and 30% for non‑executive managers.

At the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, the percentage of performance agreements that included objectives was 90% for executive managers and 57% for non‑executive managers. The percentage of performance agreements that had specific objectives was 34% for executive managers and 48% for non‑executive managers. The percentage of performance agreements with measurable results was 68% for executive managers and 28% for non‑executive managers.

5.74 Our assessment of individual accountability for equity, diversity, and inclusion goals for non‑executive managers in our representative sample fell below the results of the executives in each of the 6 organizations except in 1 case for the RCMP (Exhibit 5.6). For example, we found that 79% of the performance agreements for non‑executive managers at the Canada Border Services Agency and 89% at Correctional Service Canada included objectives related to equity, diversity, and inclusion, while results for the remaining 4 organizations ranged from 39% to 57%.

5.75 A major theme across all 6 organizations that emerged from the confidential interviews with racialized employees was the negative impacts that came from a lack of accountability of the people who directly managed them. Interviewed employees described the lack of behavioural change that followed corporate statements on the importance of building equitable, diverse, and inclusive workplaces. They also described how racism and the importance of changing behaviours have not been a sufficient focus of their leaders despite their commitments to equity, diversity, and inclusion.

Unknown impact of training

5.76 We found that organizations recognized that education was needed in order to address bias and change behaviours. Curriculums were developed by each of the 6 organizations and tied to equity, diversity, and inclusion action plans. They included mandatory courses as well as a range of alternative learning products, such as guest speakers, lunch and learn events, workshops, and corporate communications on equity, diversity, inclusion, and anti‑racism‑related topics.

5.77 We found that the RCMP and the Canada Border Services Agency included mandatory courses to specifically address anti‑racism. In addition, the RCMP and Correctional Service Canada entered into a memorandum of understanding to allow Correctional Service Canada to pilot the RCMP’s Uniting Against Racism course, which was an example of sharing of best practices across these 2 organizations.

5.78 However, we found that the 6 organizations did not have a method or measures to assess the impact of training on individual behaviours and its contribution to improved organizational outcomes. We found that compliance and course delivery rates were monitored by the 6 organizations, but this did not demonstrate whether training was sufficient, appropriate, and contributed to a change in behaviours in the way the organizations intended.

5.79 Each of the 6 organizations and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat should establish expected behaviours needed for an anti‑racist and inclusive work environment and against which performance should be assessed for employees. These behaviours should be aligned with specific equity and inclusion outcome indicators and the performance measurement frameworks.

Response of each entity. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Conclusion

5.80 We concluded that the 6 organizations took action to correct the conditions of disadvantage in employment experienced by racialized employees. However, they did not do enough to demonstrate progress toward creating an inclusive organizational culture.

5.81 The 6 organizations did not make sufficient use of data to guide their efforts, and more work is needed to address the fear of reprisal disproportionately perceived by racialized employees when considering a complaint or raising other concerns regarding racism. Accountability for behavioural and cultural change did not extend throughout the leadership in the organizations. Furthermore, none of the 6 organizations had methods or measures to assess progress against equity and inclusion objectives. As a result, organizations did not know whether an inclusive organizational culture had been achieved or whether progress had been made toward that goal.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on an inclusive and equitable public service for racialized employees. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs and to conclude on whether the 6 organizations we audited complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements, set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada applies the Canadian Standard on Quality Management 1—Quality Management for Firms That Perform Audits or Reviews of Financial Statements, or Other Assurance or Related Services Engagements. This standard requires our office to design, implement, and operate a system of quality management, including policies or procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether selected organizations took action to correct the conditions of disadvantage in employment experienced by racialized employees and had demonstrated progress toward creating an inclusive organizational culture.

Scope and approach

The audit examined selected organizations’ systems, controls, and practices that impact the organizational culture of the selected organizations regarding the inclusion of racialized groups. The audit reviewed the progress achieved in increasing these groups’ representation, participation, and influence in the workplace. It also examined selected organizations’ past results at the lowest possible disaggregated levels for racialized employees (referred to as “members of visible minorities” in the Employment Equity Act) with respect to operational data and the Public Service Employee Survey, and it assessed actions taken to improve employment representation and to address racial discrimination for racialized employees.

In conducting our work, we sought to compare the results of racialized employees with the results of employees who were not racialized in an effort to identify where systemic barriers existed. There were 2 limitations to this approach:

- Where self‑identification data was used, the population of racialized employees may not have been exact, given the voluntary nature of the data. Although we knew who had chosen to self‑identify as belonging to an employment equity group, we did not know to what extent employees had chosen not to self‑identify, even if they belonged to an employment equity group. High self‑identification response rates mitigated this limitation in part but not completely.

- There was no option under the self‑identification questionnaire in use during the audit period to self‑identify as not belonging to an employment equity group. Of particular relevance to this audit would have been the ability to self‑identify as white, which would have provided the most relevant comparator group for racialized employees. This limitation also existed in certain surveys, such as the Public Service Employee Survey, depending on the demographic questions asked.

To the extent possible, the comparator groups referred to as “non‑racialized” or “non‑visible minority” reflected individuals who completed the self‑identification questionnaire or survey in question and did not self‑identify as belonging to a racialized or visible minority group, nor did they identify as Indigenous. Given the data currently available, the audit team concluded that this was the most appropriate comparison possible. The Public Service Employee Survey provides information to help improve people management practices in the federal public service. It was administered every year, such as in 2018, 2019, and 2020, before moving to every 2 years in 2022. Results for the 2018, 2019, and 2020 surveys were available to management during the audit period, while the 2022 results were published following the end of the audit period. Where appropriate, the 2022 results were included to present the timeliest information available.

While the audit team recognizes that the federal Public Service Employee Survey does not have a 100% response rate and thus cannot provide exact values for every group, nor is it the primary source of representation data for the federal public service, the response rates for the sampled organizations are sufficiently high that the survey provides valuable insights into the state of the organizations. When coupled with other forms of data, it presents a more complete picture on which management can make decisions.

Exhibit 5.7 illustrates the response rates for the 6 sampled organizations for the Public Service Employee Survey results used in the report.

Exhibit 5.7—The response rates for the 6 sampled organizations for the Public Service Employee Survey

| Survey yearNote * | Canada Border Services Agency | Correctional Service Canada | Department of Justice Canada | Public Prosecution Service of Canada | Public Safety Canada | Royal Canadian Mounted Police |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 43.4% | 41.4% | 57.5% | 59.1% | 61.1% | 54.3% |

| 2019 | 49.4% | 47.1% | 51.3% | 58.8% | 70.0% | 58.8% |

| 2020 | 51.8% | 47.0% | 57.6% | 57.2% | 68.8% | 44.2% |

| 2022 | 44.2% | 34.7% | 56.9% | 51.5% | 60.1% | 43.2% |

Source: Based on data from the 2018 to 2022 Public Service Employee Surveys

For our audit tests, we required both raw data (databases) and existing analyses of employee survey, workforce representation, promotion, and retention data; equity, diversity, and inclusion action plans and implementation progress reports; and internal and external communication reports. We also examined representative samples of annual performance agreements to conclude on executive and non‑executive management for each of the 6 organizations with respect to the inclusion of specific equity, diversity, and inclusion objectives and results in their performance assessments. The samples were sufficient in size to conclude with a confidence level of 90% and a margin of error within +10%.

We also obtained evidence for this audit by engaging a team of independent racialized clinical psychologists experienced in trauma counselling to conduct confidential interviews with volunteer employees from the selected organizations. The audit team designed an audit interview guide in consultation with our external audit advisors and key leaders from racialized employee networks of the selected organizations. The team of psychologists reviewed the interview guide for tone and appropriateness of language. The interview guide was designed to explore the lived experiences of racialized employees within the selected organizations as well as their views on existing anti‑racism initiatives and what change is needed for improved equity in the workplace. A call for volunteers was provided in writing to leaders of racialized employee networks of the 6 organizations who in turn shared the message with their communities. The interviews were administered by the team of clinical psychologists to at least 10 participants from each audit organization (n=64). The identity of the participants was not shared with the audit team in order to protect confidentiality.

We determined the size of the sample on the basis of the availability of respondents, time provided to complete the interviews, and availability of resources. A sample size of 10 per organization was determined to be adequate in answering the research questions at hand. Sample size in qualitative research is typically determined with a goal of reaching a threshold sufficient to identify major themes related to the interview objectives, referred to as code saturation. We determined that 9 interviews were sufficient for code saturation.

Issues that were described by more than half of participants were classified as major themes. Issues that were not present in all interviews but still prevalent were included as partially identified themes if they were discussed by more than a quarter but less than half of the participants. These grouping criteria were selected to account for the many identities of participants, as they may have had very different experiences based on differing assumptions and stereotypes about each racial group.

The audit scope also included the integration of gender‑based analysis plus and United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal considerations in improving the representation of members of visible minorities in the public service, where appropriate.

The following organizations were audited:

- Canada Border Services Agency

- Correctional Service Canada

- Department of Justice Canada

- Public Prosecution Service of Canada

- Public Safety Canada

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police

The following organization was included in the scope:

- Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

We did not examine recruitment and hiring activities, nor did we examine the oversight role of the Federal Public Sector Labour Relations and Employment Board and Employment and Social Development Canada on activities related to racial discrimination and systemic racism. We also did not examine operations at the Canadian Human Rights Commission or the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal, nor did we examine Governor in Council appointments.

Criteria

We used the following criteria to conclude against our audit objective:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

There is an equity, diversity, and inclusion framework or structure in place supported by an inclusive tone from the top. |

|

|

There is evidence of sound training and performance management practices that focus on increasing education and awareness of anti‑racism. |

|

|

There are policies, systems, controls, and practices in place to appropriately resolve complaints—for example, harassment and violence, and informal conflict management services—and prevent their reoccurrence. |

|

|

There is evidence of actions taken to advance employment equity conditions related to the performance of racialized employees. |

|

|

There is evidence of supports that assist racialized employees who apply for promotion and assist them to be successful in being promoted. |

|

|

There is evidence of actions taken to advance the employment equity conditions related to the retention of racialized employees. |

|

|

The organizations are correcting identified issues such as found in employment equity reports, themes found in survey results, and complaints. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period from 1 January 2018 to 31 December 2022. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies. However, to gain a more complete understanding of the subject matter of the audit, we also examined certain matters that preceded this starting date.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 17 October 2023, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

This audit was completed by a multidisciplinary team from across the Office of the Auditor General of Canada led by Carey Agnew, Principal. The principal has overall responsibility for audit quality, including conducting the audit in accordance with professional standards, applicable legal and regulatory requirements, and the office’s policies and system of quality management.

Recommendations and Responses

In the following table, the paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report.

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

5.25 The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat should provide guidance and share best practices that will help organizations establish performance indicators to measure and report on equity and inclusion outcomes in the federal public service. This should include at minimum

|