2024 Reports 1 to 5 of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the Parliament of CanadaReport 2—Greening of Building Materials in Public Infrastructure

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings and recommendations

- The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat and Public Services and Procurement Canada were slow to prioritize low embodied carbon construction materials in federally owned infrastructure

- Infrastructure Canada included considerations of embodied carbon in its funding programs in a limited way, thereby reducing its contribution to the government’s 2030 environmental objectives

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- Recommendations and Responses

- Exhibits:

Introduction

Background

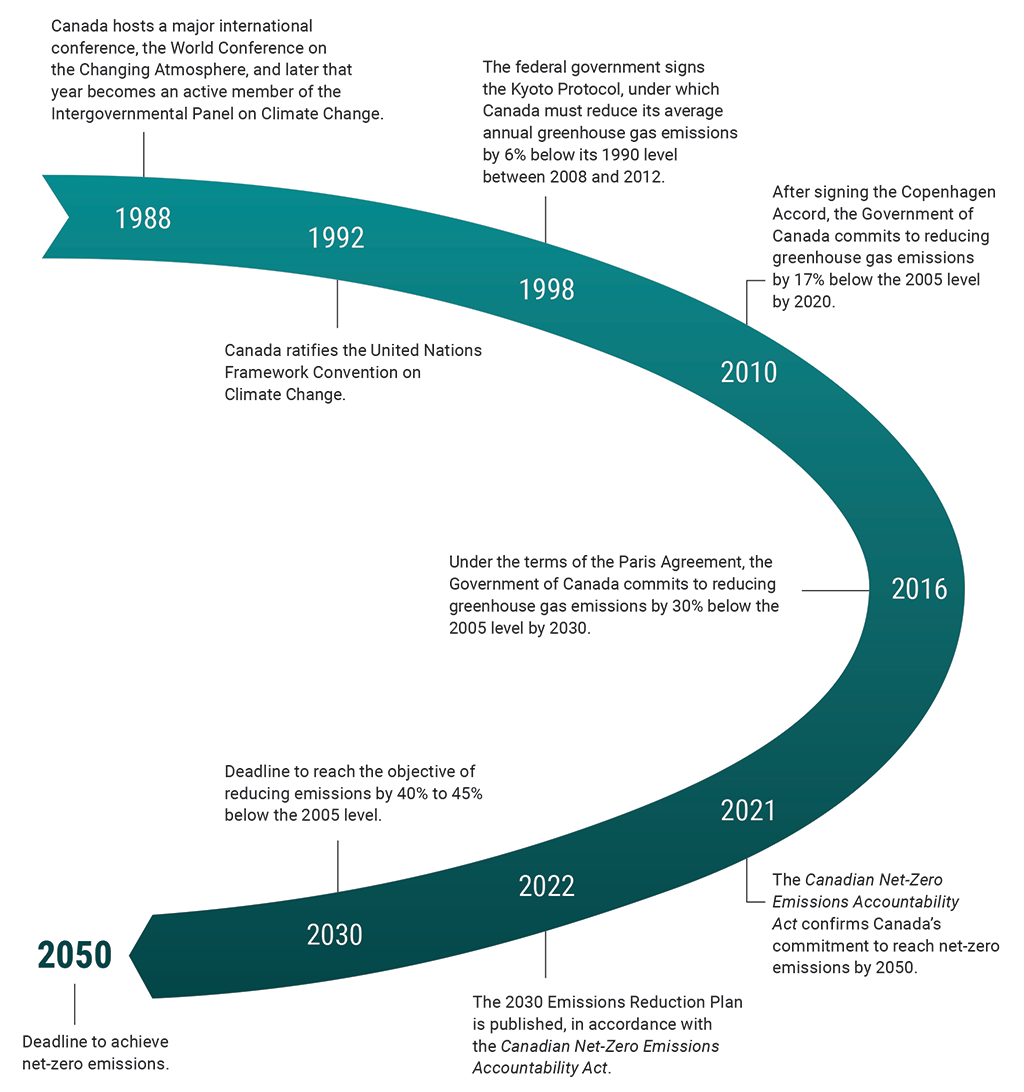

2.1 There is an urgent need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions worldwide to mitigate climate change. For more than 30 years, the Government of Canada has been making environmental and sustainable development commitments to limit the harmful effects of such emissions (Exhibit 2.1). In 2021, the Government of Canada committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 40% to 45% relative to the 2005 level by 2030.

Exhibit 2.1—Canada’s key climate commitments

Source: United Nations and various federal government sources

Exhibit 2.1—text version

This timeline shows the period from 1988 to 2050 when Canada made international commitments, enacted legislation, and set deadlines that extend to 2050.

In 1988, Canada hosts a major international conference, the World Conference on the Changing Atmosphere, and later that year becomes an active member of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

In 1992, Canada ratifies the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

In 1998, the federal government signs the Kyoto Protocol, under which Canada must reduce its average annual greenhouse gas emissions by 6% below its 1990 level between 2008 and 2012.

In 2010, after signing the Copenhagen Accord, the Government of Canada commits to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 17% below the 2005 level by 2020.

In 2016, under the terms of the Paris Agreement, the Government of Canada commits to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 30% below the 2005 level by 2030.

In 2021, the Canadian Net‑Zero Emissions Accountability Act confirms Canada’s commitment to reach net-zero emissions by 2050.

In 2022, the 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan is published, in accordance with the Canadian Net‑Zero Emissions Accountability Act.

The deadline in 2030 is to reach the objective of reducing emissions by 40% to 45% below the 2005 level.

The deadline in 2050 is to achieve net‑zero emissions.

2.2 In his report entitled Canadian Net‑Zero Emissions Accountability Act—2030 Emissions Reduction Plan from the 2023 Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development reported that the federal government was not on track to meet its target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 40% below the 2005 level by 2030. The Government of Canada must therefore speed up the implementation of measures to help prevent climate change that is irreversible and potentially harmful to humanity.

2.3 One way to help reduce greenhouse gas emissions is to reduce the emissions from construction materials. This is because the production of construction materials such as steel, concrete, and aluminum accounts for 11% of global greenhouse gas emissions. The Government of Canada, as one of the country’s largest public buyers of goods and services and a funder of public infrastructure projects, can drive the transformation of the construction materials market.

2.4 A market transformation involves a series of strategic interventions designed to bring about long‑lasting changes to the structure or functioning of that market or to the behaviour of market participants, to speed up the adoption of new technologies. A successful market transformation therefore requires the active participation of the industries involved. Direct purchasing and funding programs are market transformation tools that governments can use to motivate this active participation.

2.5 Public spending on infrastructure is one way to foster the use of green construction materials. In 2021, governments were responsible for approximately 76% of the $108 billion spent on infrastructure, 8% of which consisted of direct federal spending. Governments have also committed to spending hundreds of billions more in the coming years. For example, in its 2023 budget, the Government of Ontario anticipates spending $184.4 billion over the next 10 years, while Quebec’s 2023–33 infrastructure plan projects $150 billion in spending.

2.6 In March 2022, in its 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan: Clean Air, Strong Economy, the federal government committed to introducing a new Buy Clean Strategy for federal investments. The plan’s goal is to support and prioritize the use of made‑in‑Canada low‑carbon products in Canadian infrastructure projects. The Minister of Natural Resources, the Minister of Intergovernmental Affairs, Infrastructure and Communities, and the Minister of Public Services and Procurement are responsible for developing the strategy.

2.7 Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat—The secretariat develops the directives, standards, and performance measures that support the 2006 Policy on Green Procurement. The secretariat is also leading the Greening Government Strategy, which focuses on buying green goods and services to facilitate the transition to a less carbon-intensive economy.

2.8 Public Services and Procurement Canada—As the central purchasing agent and common service provider, the department supports federal departments and agencies in their daily operations:

- As the Government of Canada’s central purchasing agent, the department manages the procurement of goods and services on behalf of federal departments and agencies.

- The department supports the implementation of the 2006 Policy on Green Procurement, which incorporates environmental performance considerations into procurement, planning, and purchasing activities. The department must take into account environmental performance throughout the life cycle of a purchased product.

- The department’s Real Property Services provides real property management and support services to the government, ensuring the optimal use and valuation of real property assets while striving to reduce the environmental footprint of government property.

2.9 Natural Resources Canada—The department is responsible for providing guidance, in particular to the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, on matters relating to its mandate, such as energy efficiency and clean energy technologies, to support the development of green policies. The department is also leading the joint development of the Buy Clean Strategy and will work with the other federal departments and agencies involved to implement the strategy if it is approved by Cabinet.

2.10 Infrastructure Canada—The department makes significant investments in public infrastructure through its funding programs, establishes public–private partnerships, and develops policies. In the context of this audit, the department is working with Natural Resources Canada and Public Services and Procurement Canada to develop the Buy Clean Strategy to encourage the use of made‑in‑Canada low‑carbon products in infrastructure projects.

Build resilient infrastructure, promote sustainable industrialization and foster innovation

Source: United NationsFootnote 1

Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts

Source: United Nations

2.11 In 2015, Canada committed to achieving the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The goals include “Build resilient infrastructure, promote sustainable industrialization and foster innovation” (Goal 9) and “Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts” (Goal 13). The 2022–2026 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy aligns with the Sustainable Development Goals to ensure that all federal organizations are involved in implementing the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development within their areas of responsibility.

Focus of the audit

2.12 This audit focused on whether Public Services and Procurement Canada, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, and Natural Resources Canada had used the Government of Canada’s purchasing powerDefinition 1 effectively to support and prioritize the use of low embodied carbonDefinition 2 construction materials, including steel, aluminum, and concrete, in public infrastructure projects in order to contribute to environmental protection and sustainable development. It also focused on determining whether Infrastructure Canada made effective use of its funding programs in pursuit of that goal.

2.13 This audit is important because it is estimated that the greenhouse gas emissions from construction and construction materials account for 11% of Canada’s total emissions. With the amounts it spends on public infrastructure, the federal government is able to demonstrate the environmental leadership to which Canada aspires, fulfill its commitment to reducing the emissions from its operations, and help industry reduce its greenhouse gas emissions, thereby contributing to the achievement of Canada’s 2030 climate goals and its 2050 goal of net‑zero emissions.

2.14 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings and recommendations

The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat and Public Services and Procurement Canada were slow to prioritize low embodied carbon construction materials in federally owned infrastructure

2.15 This finding matters because federal public procurement is the tool over which the Government of Canada has the most control for achieving the embodied carbon objectives of its Policy on Green Procurement. In light of the climate emergency, any delay in using this tool slows down the widespread adoption of low embodied carbon construction materials as well as their substitution or reduced quantities used in federal public infrastructure and hampers the contribution of public procurement to Canada’s climate goals.

2.16 The Policy on Green Procurement was implemented in 2006 under the responsibility of Public Services and Procurement Canada. It requires deputy headsDefinition 3 to incorporate environmental considerations into their procurement processes. The policy was transferred to the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat in 2016, shortly after the creation of its Centre for Greening Government.

2.17 In the policy, the federal government expresses its goal of demonstrating environmental leadership. One of its objectives is to influence industry and citizens to use environmentally preferable and climate-resilient goods, services, and processes. Another objective is to stimulate the innovation and market development of, and demand for, environmentally preferable goods and services, making them available and mainstream for other sectors of society.

2.18 To achieve its objectives, the government wants to leverage its procurement activities to reduce the cost of environmentally preferable goods and services. It also wishes to strengthen green markets and industries.

2.19 In October 2023, the Department of Public Works and Government Services Act was amended to require that the minister consider any potential reduction in greenhouse gas emissions and any other environmental benefits when developing requirements with respect to the construction, maintenance, and repair of public works, federal real property, and federal immovables and to allow the use of wood or any other thing—including a material, product, or sustainable resource—that achieves such benefits.

2.20 The carbon emissions of built infrastructure can be divided into 2 main categories: embodied carbon (defined in paragraph 2.12) and operational carbonDefinition 4. Some infrastructure, like buildings, generate both operational and embodied carbon. Infrastructure like bridges, roads, and sewers mainly generate embodied carbon. Therefore, it is possible to reduce an infrastructure’s emissions by reducing its embodied carbon, its operational carbon, or a combination of both. Maximum reduction of the emissions from an infrastructure is impossible unless both the embodied and the operational carbon are reduced.

2.21 Even after construction is complete, the operational carbon of an infrastructure can still be reduced—for example, by using renewable power and modernizing its lighting, heating, and ventilation systems. Embodied carbon, on the other hand, is essentially irreversible once construction is complete. Some relative reductions may still be achieved—for example, during repairs and renovations. This means that the procurement and construction phases represent the only opportunities to significantly reduce the embodied carbon of built infrastructure. After that, the carbon is “locked in” for the life of the infrastructure.

2.22 In recent decades, governments and the private sector have focused primarily on reducing the operational carbon of infrastructure by developing data, standards, certifications, and tools. Examples include the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED®) and the Energy Star® certifications for buildings and programs to improve energy efficiency, such as the Market Transformation Strategies for Energy-Using Equipment in the Building Sector published in 2017 by federal, provincial, and territorial ministers of energy and mines.

2.23 Yet, solutions for reducing the embodied carbon of construction materials have been around for a long time. For example, Portland-limestone cement has a carbon footprint that is on average 10% lower than that of traditional cement, while being of equivalent strength and durability. This type of cement has been widely used in Europe for more than 35 years. In Canada, Portland-limestone cement was added to the concrete materials standards in 2009. In the United States, it has been used by some states to pave highways since 2007.

2.24 Furthermore, innovative ideas for reducing the quantity of materials used, reusing existing materials, or substituting construction materials—for example, replacing steel with engineered wood, can effectively reduce the amount of embodied carbon in infrastructure.

2.25 Internationally, some governments have already taken steps to reduce the embodied carbon of construction materials. For example, in 2012, the Netherlands’ Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management developed DuboCalc, a tool that calculates the embodied carbon of construction materials, among other things. This enables the ministry to offer contractors financial incentives to choose low embodied carbon materials during the design phase. In addition, in 2017, California passed the Buy Clean California Act. Under that act, since 2019, suppliers have been required to submit environmental product declarations for certain construction materials, such as structural steel, flat glass, and insulation products, used in public infrastructure projects. In 2022, California established carbon limits for some construction materials.

Embodied carbon not taken into consideration before 2016

2.26 We found that, between the initial publication of the Policy on Green Procurement in 2006 and its transfer to the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat in 2016, Public Services and Procurement Canada took no steps to stimulate the innovation and market development of or demand for low embodied carbon materials. This was a missed opportunity to contribute to the widespread adoption of low embodied carbon construction materials, and it hindered the achievement of Canada’s climate goals.

2.27 And yet, according to Statistics Canada, in the 10 years between 2006 and 2016, the federal government spent approximately $4.2 billion to acquire or refurbish federal public infrastructure. We noted that during that period, Public Services and Procurement Canada made progress in reducing the operational carbon emissions of federal public infrastructure. However, we saw no documentation to indicate that similar efforts were made to reduce the embodied carbon of infrastructure construction materials. Yet, a maximum reduction of infrastructure emissions requires reducing both embodied and operational carbon. We noted that every infrastructure built without consideration of embodied carbon represents a missed opportunity to contribute to the reduction of greenhouse gases.

Insufficient progress since 2017

2.28 We found that, since 2017, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, through its Centre for Greening Government, had gradually put in place measures to encourage a reduction in the embodied carbon of construction materials. In 2017, the secretariat published the first version of its Greening Government Strategy, with the objective being to “minimize embodied carbon“ in the construction materials used in the government’s real property.

2.29 We found that, at that time, the secretariat had no data for measuring embodied carbon in the government’s real property. As a result, the initial strategy could not set a quantitative objective for reducing embodied carbon; it simply made stakeholders aware that embodied carbon was now on the federal government’s radar. To address the lack of data, the secretariat worked with the National Research Council Canada from 2019 to mid‑2022 to develop the Low‑Carbon Assets Through Life Cycle Assessment initiative. The goal was to gather the necessary data for establishing quantitative thresholds for embodied carbon reductions.

2.30 In 2020, the Centre for Greening Government updated the Greening Government Strategy to include more precise and quantifiable objectives:

- Disclose the amount of embodied carbon in the structural materials of major construction projects by 2022 according to material carbon intensity or a life‑cycle analysis.

- Reduce the embodied carbon of the structural materials of major construction projects by 30%, starting in 2025, using recycled and lower-carbon materials, material efficiency, and performance-based design standards.

- Conduct whole building (or asset) life‑cycle assessments by 2025 at the latest for major building and infrastructure projects.

2.31 We found that the strategy’s first objective, namely disclosure of the amount of embodied carbon in the structural materials of major construction projects by 2022, was not achieved by 2022. In December 2022, the secretariat introduced the Standard on Embodied Carbon in Construction, which requires that departments named in the Policy on Green Procurement disclose and reduce the embodied carbon footprint of ready‑mix concrete for any new construction or renovation of real property in Canada with a value of $10 million or more. The strategy was updated in September 2023 to remove the 2022 deadline given that the standard was then in place.

2.32 More precisely, the Standard on Embodied Carbon in Construction requires that the embodied carbon of the ready‑mix concrete used in infrastructure projects be 10% less than the regional average for federal infrastructures. Given that the standard took effect on 31 December 2022 and that infrastructure projects take several years to complete, secretariat officials informed us that public disclosure about the reduction of embodied carbon in ready‑mix concrete will begin in 2024–25.

2.33 We noted that, to assess the effectiveness of the Standard on Embodied Carbon in Construction, it is essential to have several years of quality data on the embodied carbon of structural construction materials. In our opinion, as things currently stand, it could be challenging for the Centre for Greening Government to collect enough information on the embodied carbon of the structural materials of major construction projects before 2025.

2.34 We also found that the Greening Government Strategy targets the “structural materials of major construction projects,” whereas the 2022 version of the standard applies only to ready‑mix concrete. In addition to concrete, however, steel, which is widely used in major construction projects and is known for its high levels of embodied carbon, is also a structural construction material. Contrary to the objectives set out in the strategy, the secretariat’s standard does not capitalize on the potential for reducing the embodied carbon of steel.

2.35 The secretariat informed us that it is currently consulting with Canada’s steel industry and is gathering information to identify a way to incorporate steel into the standard. If steel were included in the standard, the secretariat would be able to establish a benchmark for the embodied carbon from steel in public infrastructure and could subsequently require reductions relative to that benchmark.

2.36 Active dialogue between the steel industry and the secretariat is vital for the secretariat’s timely receipt of the data needed to include steel in the standard. However, we found that no date had been set for the inclusion of steel. Any delay in including steel in the standard will slow market adoption of low embodied carbon steel and hinder the achievement of Canada’s near‑term climate goals, particularly the 2030 goals.

2.37 In 2022, Natural Resources Canada determined that 22% of the aluminum produced worldwide was used in construction, primarily for skyscrapers and bridges. The secretariat’s Standard on Embodied Carbon in Construction currently addresses concrete construction products, but work is underway to incorporate steel construction products. These 2 materials are particularly harmful to the environment. In its Greening Government Strategy, the secretariat committed to conducting whole-building life‑cycle assessments by 2025. If this commitment is respected, the life‑cycle assessment of buildings should help reduce emissions from all construction materials that have an impact on the embodied carbon of infrastructure, in addition to concrete and steel. In real terms, the life‑cycle assessment of buildings would determine the contribution of aluminum to the carbon footprint.

2.38 We found that Natural Resources Canada had cooperated with the other departments by offering its expertise, as required by the Policy on Green Procurement. For example, the department had helped Public Services and Procurement Canada explore the creation of a procurement search tool for green products by conducting an analysis of existing tools. We noted, however, that Natural Resources Canada’s expertise was limited mainly to energy efficiency and, therefore, to operational carbon. That said, we found that the department’s responsibilities had evolved during the audit period, with greater focus being placed on embodied carbon. The department was therefore actively developing its expertise in that area.

2.39 To meet its commitments under the Greening Government Strategy and optimize the strategy’s contribution to the achievement of the 2030 climate goals, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat should move quickly to identify which structural construction materials, such as steel, should be included in the Standard on Embodied Carbon in Construction.

The secretariat’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

No systematic consideration of embodied carbon

2.40 Under the Policy on Green Procurement, Public Services and Procurement Canada must “include environmentally preferable options (that is, that have a lesser or reduced impact on the environment over the life cycle of the good or service, when compared with competing goods or services serving the same purpose) in the procurement services offered to client departments where feasible.” We found that the department had no systematic, standardized approach to identifying options for reducing the embodied carbon in federal real property projects.

2.41 In the context of the public infrastructure procurement process, Public Services and Procurement Canada officials will evaluate design plans to ensure that they meet the minimum expected requirements.

2.42 The department informed us that it does not follow a systematic and standardized process for challenging drafts and plans submitted by consultants regarding embodied carbon. Such an approach would allow the department to consistently identify opportunities in proposed projects to reduce the embodied carbon footprint in the federal government’s building stock. Even though we reviewed a draft that had been revised to significantly reduce the embodied carbon footprint, the lack of a systematic and standardized process for challenging drafts may undermine the department’s efforts to maximize embodied carbon reductions in future infrastructure projects.

2.43 To better meet its responsibilities under the 2006 Policy on Greening Government and improve its ability to propose environmentally preferable options, Public Services and Procurement Canada should establish and implement a systematic, standardized approach to challenging the drafts submitted by consultants that includes criteria to enable the department to measure the effectiveness of the challenge function in identifying ways to reduce embodied carbon in federal real property projects.

The department’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Infrastructure Canada included considerations of embodied carbon in its funding programs in a limited way, thereby reducing its contribution to the government’s 2030 environmental objectives

2.44 This finding matters because federal funding programs are one of the government’s most powerful tools for promoting its objectives and priorities. Given the importance of working with other levels of government to expedite the greening of the construction material industry, insufficient consideration of embodied carbon in funding programs represents a missed opportunity to contribute to government‑wide efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and achieve the 2030 climate goals.

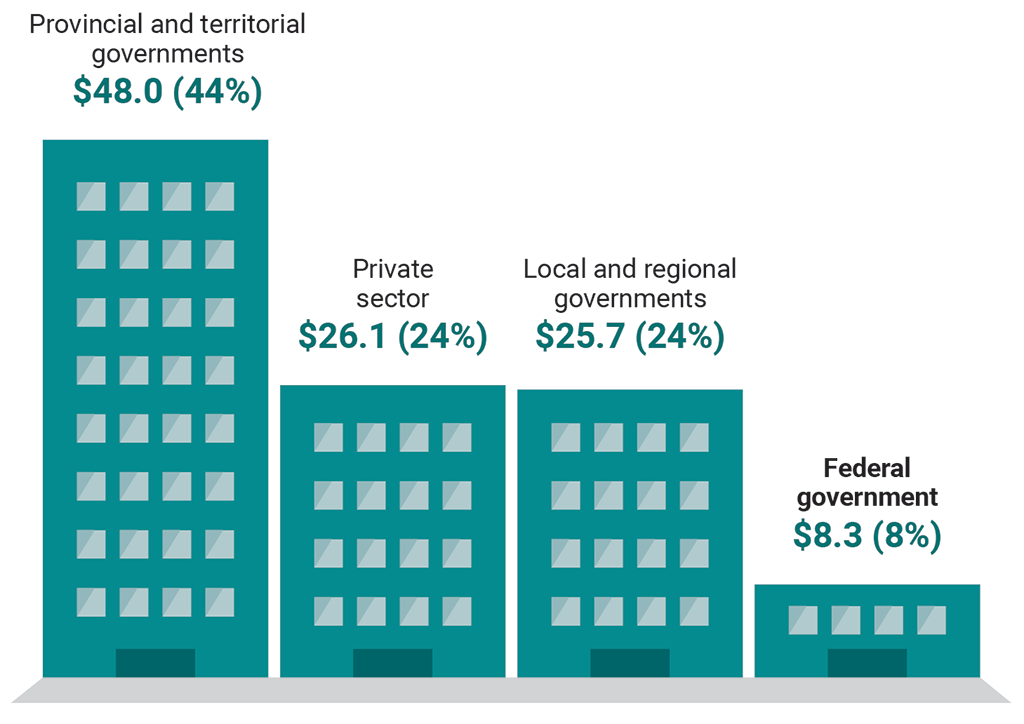

2.45 According to the Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development (OECD), Canada has one of the most decentralized public procurement systems in the world. In 2019, the federal government’s procurement spending accounted for only 12% of total spending by all levels of government in Canada, whereas it was as much as 80% in other OECD countries. Most Canadian public infrastructure spending was on projects managed by provincial, territorial, and municipal governments. In 2021, while federal infrastructure spending totalled $8 billion, infrastructure spending by provinces, territories, and municipalities totalled $74 billion (Exhibit 2.2).

Exhibit 2.2—Spending on infrastructure in Canada in 2021 (billions of dollars)

Source: Based on Statistics Canada data

Exhibit 2.2—text version

This exhibit compares the spending in 2021 by different levels of government and by the private sector on infrastructure in Canada. Provincial and territorial governments spent the most on infrastructure, and the federal government spent the least. The private sector and local and regional governments spent similar amounts.

Provincial and territorial governments spent $48 billion or 44% of the total spending.

The private sector spent $26.1 billion or 24% of the total spending.

Local and regional governments spent $25.7 billion or 24% of the total spending.

The federal government spent $8.3 billion or 8% of the total spending.

2.46 Through transfer programs, Infrastructure Canada provides significant funding to provincial, territorial, and municipal governments to support public infrastructure projects in the areas of transportation, housing, climate resilience, and rural and northern community living. From 2014 to 2023, Infrastructure Canada approved more than $46 billion in federal contributions to fund infrastructure projects across the country.

2.47 Infrastructure Canada has 2 main approaches to managing funds with its program partners. With allocation-based programs, the department relies on provinces and territories to identify projects, submit applications, and distribute federal funding to the ultimate recipients. For direct funding programs, on the other hand, applications are submitted directly to the department, which approves projects on the basis of the program eligibility and merit requirements. Direct funding programs allow the federal government more control in deciding which projects to prioritize.

2.48 Over the years, Infrastructure Canada has assumed greater responsibility for federal government objectives relating to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions (Exhibit 2.3).

Exhibit 2.3—Evolution of Infrastructure Canada climate responsibilities

|

2008 |

Policy on Transfer Payments | Departments responsible for delivering transfer payments, including Infrastructure Canada, must design and implement programs that take the government’s priorities into account, including its climate commitments. |

|

2017 |

2016–17 Departmental Results Report | For the first time, Infrastructure Canada indicates that one of its major objectives involves reducing greenhouse gas emissions. |

|

2019 |

Minister of Infrastructure and Communities Mandate Letter | Infrastructure Canada is mandated to work with the Federation of Canadian Municipalities through the Green Municipal Fund to monitor investments and ensure they reduce emissions from residential, commercial, and multi‑unit buildings. |

|

2020 |

Federal Sustainable Development Act | In accordance with this act, Infrastructure Canada must adhere to the principles of the 2022–2026 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy. The strategy aims to “foster innovation and green infrastructure in Canada” in order to contribute by 2030 to advancing United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 9 (Industries, innovation and infrastructure), which is to “Build resilient infrastructure, promote sustainable industrialization and foster innovation.” |

Source: Various federal government sources

2.49 In 2018, Infrastructure Canada launched the Climate Lens tool to promote and enable the estimation of expected reductions in greenhouse gas emissions and the assessment of climate risks and resilience outcomes. The findings of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development regarding the Climate Lens are in Report 4, Funding Climate-Ready Infrastructure—Infrastructure Canada in the 2022 Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development.

2.50 In 2021, Infrastructure Canada was given the clear mandate to support government‑wide efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, which includes embodied carbon. Specifically, the Minister of Intergovernmental Affairs, Infrastructure and Communities was mandated to work with the Minister of Natural Resources and the Minister of Public Services and Procurement “to introduce a new Buy Clean Strategy to support the use of made‑in‑Canada low‑carbon products in Canadian infrastructure projects.”

2.51 Strategies prioritizing the purchase of low‑carbon products, which aim to transform the market, have increased in popularity in recent years. In February 2022, the United States government announced the creation of the Federal Buy Clean Initiative and Task Force, designed to prioritize the use of low‑carbon construction materials made in the United States for federal procurement and for federally funded projects. In March 2023, the United States government announced that it was partnering with 12 states that had committed to prioritizing low‑carbon construction materials for projects that they fund. In December 2023, the General Services Administration announced a $2‑billion investment to support more than 150 federal construction projects that use low‑carbon materials.

Few measures prioritizing construction materials with a low‑carbon footprint

2.52 We found that Infrastructure Canada had not announced any new programs since receiving the December 2021 mandate letter, which limited its opportunities to fulfill its explicit mandate to support government‑wide efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, particularly embodied carbon.

2.53 We also found that Infrastructure Canada had incorporated criteria for reducing embodied carbon in only a small section of a single existing funding program, namely new building projects under the second stream of the Green and Inclusive Community Buildings Program (Exhibit 2.4). The program has a budget of $1.5 billion to be disbursed over 5 years on retrofit and new building projects. According to the data provided by the department, as of the end of the audit period, $279 million from this envelope has been publicly approved for 25 new building projects. The vast majority of the approved projects required the production of a report on levels of embodied carbon, and 2 of them also included requirements to reduce embodied carbon. Under this program, 1 project located in a northern region was seeking an exemption from embodied carbon requirements in view of geographic constraints.

Exhibit 2.4—Green and Inclusive Buildings Program

In the second stream of the Green and Inclusive Community Buildings Program, announced in December 2022, Infrastructure Canada requires that new building projects comply with the Zero Carbon Building Design Standard, version 3. This standard, which was introduced by the Canada Green Building Council in June 2022, requires a 10% reduction in embodied carbon relative to a baseline building or an absolute threshold for embodied carbon intensity.

Prior to that, Infrastructure Canada required that new building projects submitted before 29 September 2022 comply with the Zero Carbon Building Design Standard, version 2. That standard only required a report on embodied carbon.

2.54 We also found that this requirement of the second stream of the Green and Inclusive Community Buildings Program did not enable Infrastructure Canada to collect data on low embodied carbon construction materials. This is because the Zero Carbon Building Design standard, version 3, is administered by the Canada Green Building Council, which receives the analyses submitted by applicants to demonstrate project compliance with the standard. As a result, Infrastructure Canada does not receive the data or analyses on a project’s embodied carbon. The department acknowledges, however, that the lack of data is a key factor hindering its progress on reducing embodied carbon.

2.55 We nevertheless found that Infrastructure Canada had attempted to encourage the disclosure of data on embodied carbon in its projects subject to the requirements of the Climate Lens. In December 2023, the department added an explicit reference to low embodied carbon construction materials in its Climate Lens guidance. However, the quantity of data collected depends entirely on applicants’ goodwill given that disclosure is purely voluntary, and programs that apply the Climate Lens are not required to comply with any embodied carbon reporting requirements.

2.56 We also found that Infrastructure Canada had not yet incorporated embodied carbon considerations into a wide range of funding programs and that the department had not yet made use of the tools developed by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat and based on the work of the National Research Council Canada.

2.57 In 2019, Infrastructure Canada, together with the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, Natural Resources Canada, and Environment and Climate Change Canada, provided funding to the National Research Council Canada to lead the Low‑Carbon Assets Through Life Cycle Assessment initiative. Through this initiative, the National Research Council Canada produced outputs, including data to establish quantitative thresholds for embodied carbon reductions, which supported the development of the secretariat’s 2022 Standard on Embodied Carbon in Construction. However, Infrastructure Canada officials informed us that they must better understand the impact of adding embodied carbon requirements both on applicants (for example, applicants’ capacity to implement the requirements) and on projects requiring funding (for example, cost, timelines) before they can include such requirements in future funding programs.

2.58 To this end, Infrastructure Canada indicated that it wanted to draw lessons from the implementation of the standard in federal construction projects in order to inform its own implementation strategy. Also, in September 2023, the department contracted an independent analysis of the regional availability, performance, and cost of low‑carbon construction materials. The report from this independent contract is expected in June 2024 and will also inform the approach for incorporating embodied carbon considerations into future funding programs. However, Infrastructure Canada did not provide a deadline or time frame within which it expected to incorporate these considerations into a wider range of funding programs.

2.59 In our opinion, funding programs could include financial incentives to use low embodied carbon materials that would benefit applicants who decide to take advantage of them without penalizing those who cannot or choose not to do so. Some countries, including the United States, use such a tool (Exhibit 2.5). In other areas, such as energy efficiency, financial incentives have been used regularly to stimulate the adoption of environmentally preferable products. These incentives could speed up the adoption of low embodied carbon materials and enable the department to play a leadership role.

Exhibit 2.5—Examples of incentives offered by the United States federal government

In March 2023, the United States Federal Emergency Management Agency, which is the federal organization responsible for managing disaster response, announced that it would offer additional funding to states for low‑carbon rebuilding after disasters. The additional funding will help cover the higher costs of purchasing materials, such as concrete and steel, that are certified as having lower carbon emissions.

Under the United States’ Inflation Reduction Act, $2 billion was granted to the Federal Highway Administration to reimburse it for the extra costs of low embodied carbon materials and products used in construction projects or to offer incentives to eligible applicants.

2.60 Incidentally, some provincial and municipal partners signalled their willingness to work with the Government of Canada to reduce governments’ greenhouse gas emissions by creating the Buyers for Climate Action coalition in 2021. The coalition brings together leading green buyers who purchase a high volume of goods and services, including real property, and who are carrying out various initiatives to develop sample procurement specifications for net‑zero buildings and low‑carbon construction materials.

2.61 At the time of the audit, the Buy Clean Strategy was still under development. We are therefore unable to comment on it. However, we examined some of the analyses and factors considered by the federal government organizations responsible for developing the strategy, including Public Services and Procurement Canada, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, Natural Resources Canada, and Infrastructure Canada. In our opinion, the analysis carried out to date duly considers the factors that, according to studies, contribute to successful market transformation strategies.

2.62 To support government‑wide efforts to speed up the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and make progress by 2030 on Goal 9 of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals and the objectives set out in the 2022–2026 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy, Infrastructure Canada should incorporate embodied carbon reduction considerations into the widest possible range of its funding programs.

The department’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Conclusion

2.63 We concluded that Public Services and Procurement Canada, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, and Infrastructure Canada did not use the Government of Canada’s purchasing power effectively to support and prioritize the use of low embodied carbon construction materials, in particular steel, aluminum, and concrete, in public infrastructure projects in order to contribute to environmental protection and sustainable development.

2.64 We also concluded that Natural Resources Canada was adequately fulfilling its supporting role with regard to its expertise in operational carbon, and that the department was actively developing expertise to enable it to assume greater responsibilities in the area of embodied carbon.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on the greening of construction materials in public infrastructure. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs and to conclude on whether the greening of construction materials in public infrastructure complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements, set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada applies the Canadian Standard on Quality Management 1—Quality Management for Firms That Perform Audits or Reviews of Financial Statements, or Other Assurance or Related Services Engagements. This standard requires our office to design, implement, and operate a system of quality management, including policies or procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether Public Services and Procurement Canada, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, Natural Resources Canada, and Infrastructure Canada had used the Government of Canada’s purchasing power effectively to support and prioritize the use of low embodied carbon construction materials, in particular steel, aluminum, and concrete, in public infrastructure projects in order to contribute to environmental protection and sustainable development.

Scope and approach

During the audit, we interviewed representatives and stakeholders from the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, Public Services and Procurement Canada, Infrastructure Canada, and Natural Resources Canada. We examined and analyzed documents provided by those organizations. We also analyzed the feedback they received from working groups. Furthermore, we looked at case studies of how the organizations incorporated embodied carbon considerations into their procurement and funding processes.

Criteria

We used the following criteria to conclude against our audit objective:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Public Services and Procurement Canada, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, and Natural Resources Canada incorporate considerations that prioritize the purchase of low embodied carbon construction materials. |

|

|

Infrastructure Canada, Natural Resources Canada, and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat propose approaches to support the use of low embodied carbon construction materials in the design and construction of public infrastructure by the federal government, or by another level of government but funded in part by the federal government, to support Canada’s greenhouse gas reduction goals. |

|

|

The use of low embodied carbon construction materials in public infrastructure built directly by the Government of Canada, or by another level of government but funded in part by the federal government, is measured effectively and makes it possible to determine whether such use contributes to the achievement of Canada’s sustainable development goals. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period from 1 December 2021 to 29 February 2024. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies. However, to gain a more complete understanding of the subject matter of the audit, we also examined certain matters that preceded the start date of this period.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 20 March 2024, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

This audit was completed by a multidisciplinary team from across the Office of the Auditor General of Canada led by Susan Gomez, Principal. The principal has overall responsibility for audit quality, including conducting the audit in accordance with professional standards, applicable legal and regulatory requirements, and the office’s policies and system of quality management.

Recommendations and Responses

Responses appear as they were received by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada.

In the following table, the paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the locationof the recommendation in the report.

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

2.39 To meet its commitments under the Greening Government Strategy and optimize the strategy’s contribution to the achievement of the 2030 climate goals, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat should move quickly to identify which structural construction materials, such as steel, should be included in the Standard on Embodied Carbon in Construction. |

The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s response. Agreed. By the end of March 2025, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat will identify the high embodied carbon structural materials to which the Standard on Embodied Carbon in Construction (the standard) applies. Concrete is already included in the standard, and the secretariat is in the process of working with key partners to add steel construction products. |

|

2.43 To better meet its responsibilities under the 2006 Policy on Greening Government and improve its ability to propose environmentally preferable options, Public Services and Procurement Canada should establish and implement a systematic, standardized approach to challenging the drafts submitted by consultants that includes criteria to enable the department to measure the effectiveness of the challenge function in identifying ways to reduce embodied carbon in federal real property projects. |

Public Services and Procurement Canada’s response. Agreed. To implement this recommendation, Public Services and Procurement Canada will complete the work that has been going on since 31 December 2022 when the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat published its new Standard on Embodied Carbon in Construction. Public Services and Procurement Canada will finalize this ongoing work so embodied carbon is fully integrated into its existing systematic and standardized quality control process for reviewing design mandate deliverables. |

|

2.62 To support government‑wide efforts to speed up the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and make progress by 2030 on Goal 9 of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals and the objectives set out in the 2022–2026 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy, Infrastructure Canada should incorporate embodied carbon reduction considerations into the widest possible range of its funding programs. |

Infrastructure Canada’s response. Agreed. lnfrastructure Canada has included embodied carbon disclosure and reduction considerations in select programs and will continue to expand consideration of embodied carbon in its infrastructure projects through its future infrastructure funding programs. ln keeping with best practices, the department will test embodied carbon requirements in some programs while validating the market availability and cost of these products and the robustness of the supporting data (namely, environmental product declarations) to ensure the application of embodied carbon reduction requirements is reasonable. |