2024 Reports 1 to 5 of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the Parliament of CanadaReport 3—Zero Plastic Waste

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings and Recommendations

- Despite some delays, the implementation of waste-reduction activities was mainly proceeding as intended

- Environment and Climate Change Canada coordinated with other federal organizations to launch the initiative

- Key federal organizations did not yet measure how much the horizontal initiative was helping Canada reach zero plastic waste

- The lack of proactive risk management increased the chances of waste-reduction activities not succeeding

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- Recommendations and Responses

- Exhibits:

- 3.1—Plastic waste in Canada from 2012 to 2019

- 3.2—Ways to manage plastic waste from least to most harmful to the environment

- 3.3—Timeline of events leading up to the zero plastic waste horizontal initiative

- 3.4—Eleven of the 16 activities we sampled had begun achieving results for the initiative as of September 2023

- 3.5—Five of the 16 activities we sampled had completed or were developing preliminary requirements for implementation as of September 2023

- 3.6—As of 31 March 2023, $86 million of the total initiative funding of $279 million had been spent to carry out activities

- 3.7—Two key results for the initiative and associated targets and indicators

Introduction

Background

3.1 Plastic pollution negatively affects the natural environment by directly harming wildlife and by altering habitats and natural processes. As noted by the United Nations Environment Programme, it reduces ecosystems’ abilities to adapt to climate change. In turn, this harm directly affects millions of people’s livelihoods, food production capabilities, and social well‑being. As well, there are mounting concerns about the negative impact of plastic pollution on human health.

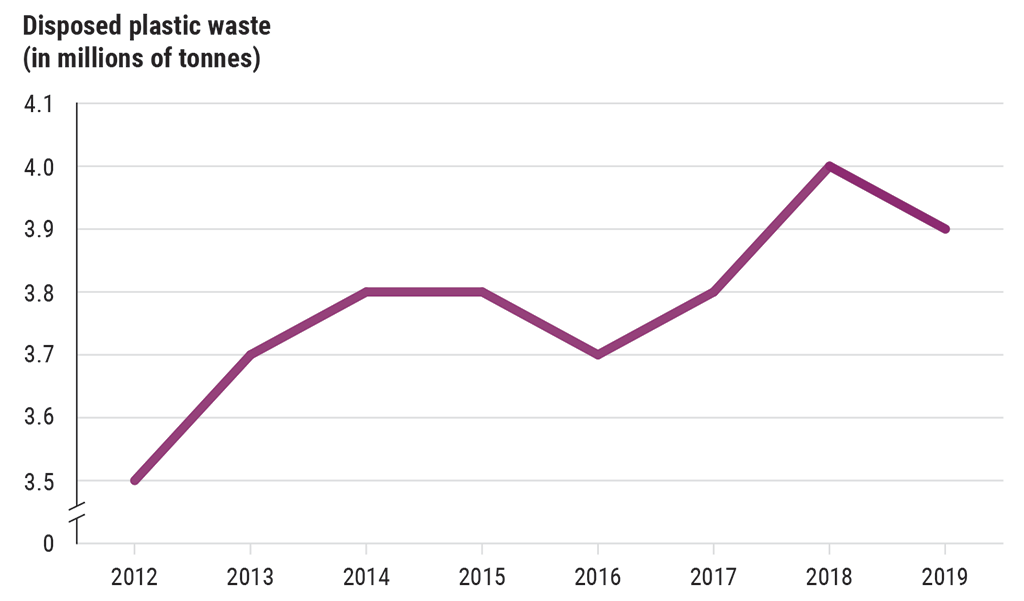

3.2 In 2019, Environment and Climate Change Canada commissioned a study of plastics that were introduced to the market through both domestic and imported products. It found that 70% of plastics on the market were disposed of as waste, most of which ended up in landfills. Statistics Canada’s data shows that plastic waste in Canada increased from 2012 to 2018 (Exhibit 3.1). According to Environment and Climate Change Canada, if current trends stay the same, demand for plastics in Canada will grow by almost 30% by 2030.

Exhibit 3.1—Plastic waste in Canada from 2012 to 2019

Source: Based on data from Statistics Canada, March 2023

Exhibit 3.1—text version

This line graph shows the increase in the amount of disposed plastic waste in Canada from 2012 to 2019 in millions of tonnes.

In 2012, approximately 3.5 million tonnes of plastic was disposed of. That amount rose to 3.7 million tonnes in 2013 and to 3.8 million tonnes in both 2014 and 2015. It fell to 3.7 million tonnes in 2016 before rising again to 3.8 million tonnes in 2017 and then to 4.0 million tonnes in 2018. It fell to 3.9 million tonnes in 2019.

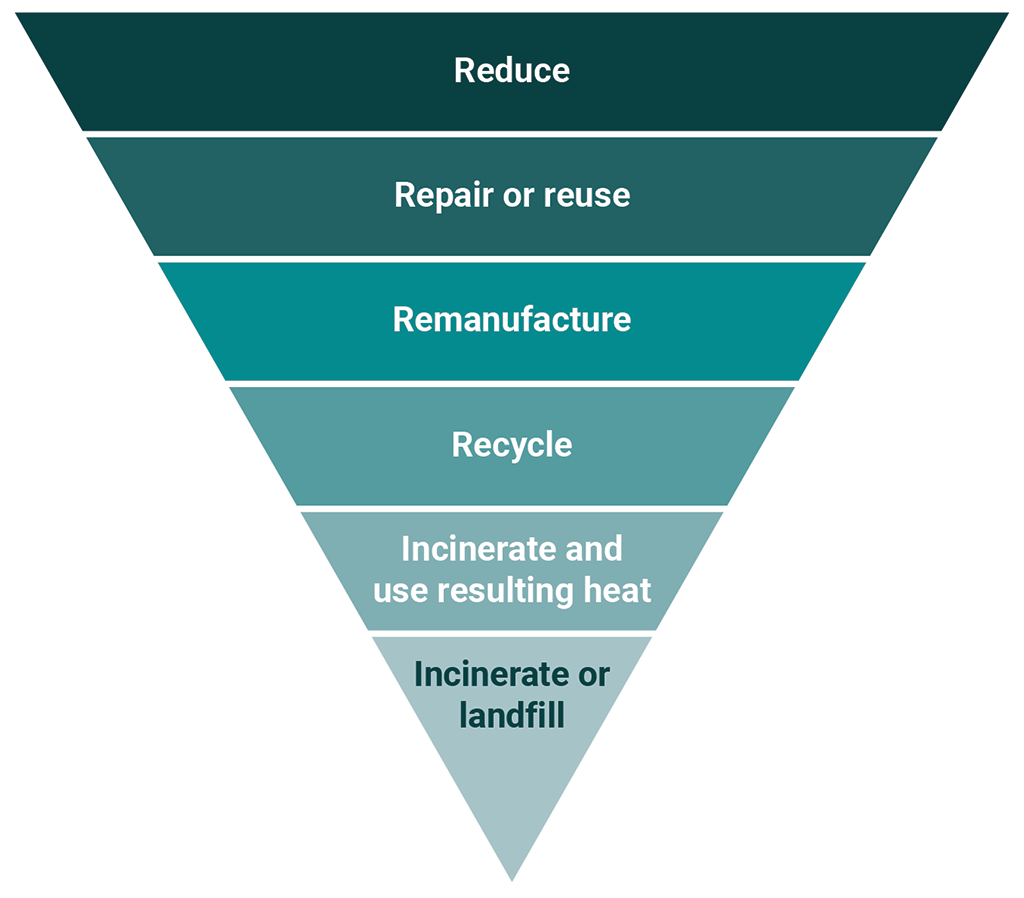

3.3 In 2019, Canada had similar rates of treating plastic waste as the other countries belonging to the Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development. The organisation’s categories for plastic waste management were “recycled,” “incinerated,” “landfilled,” and “mismanaged and uncollected litter,” in order of preference for how waste should be managed (Exhibit 3.2). The only notable difference was that Canada landfilled a higher proportion of its plastic waste, while the other countries incinerated more of their plastic waste.

Exhibit 3.2—Ways to manage plastic waste from least to most harmful to the environment

Source: Adapted from information provided by Environment and Climate Change Canada

Exhibit 3.2—text version

This list of ways to manage plastic waste from least to most harmful to the environment forms an inverted triangle. It shows the following management options in order from least to most harmful:

- Reduce

- Repair or reuse

- Remanufacture

- Recycle

- Incinerate and use resulting heat

- Incinerate or landfill

3.4 Beginning in 2018, several events took place leading up to the Government of Canada funding a horizontal initiative in 2019 to achieve zero plastic waste by 2030 (Exhibit 3.3). The initiative’s goal is to contribute to creating a circular economy for plastics in Canada by 2030. In a circular economy, nothing is waste. For plastics, this would mean that by 2030, no plastic waste would be sent to landfills or released into the environment. Instead, plastics would be repaired, reused, remanufactured, or recycled. According to a 2019 study commissioned by Environment and Climate Change Canada, diverting even 90% of waste from landfills would require large increases in recycling and other methods of treating plastic waste.

Exhibit 3.3—Timeline of events leading up to the zero plastic waste horizontal initiativeNote 1

| Date | Event | Significance of the event |

|---|---|---|

|

June 2018 |

In its role as Group of SevenNote 2 president, Canada spearheads the Ocean Plastics Charter. |

The charter outlines key targets toward managing plastics more efficiently and sustainably. It will be the foundation for the next steps toward targeting zero plastic waste. |

|

November 2018 |

The Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment approves the Canada‑wide Strategy on Zero Plastic Waste. |

The strategy marks the agreement of Canada’s federal, provincial, and territorial environment ministers to work collectively toward the goal of zero plastic waste. It aligns with the charter and sets the framework for collaborative actions across many sectors. |

|

June 2019 and July 2020 |

The council approves phase 1 and phase 2 of an action plan to implement the strategy. |

The action plan specifies priority actions for council member jurisdictions, including the federal government. |

|

2019 |

To fulfill its commitments under the charter, the strategy, and the action plan, the federal government begins Phase 1—Federal Leadership Towards Zero Plastic Waste in Canada Horizontal Initiative. |

The federal government earmarks about $65 million to be spent on this first phase of the initiative from 2019 to 2022. Phase 1 is to focus on the scientific and data needs for a plan to reduce plastic waste using the best available research. Environment and Climate Change Canada leads the initiative, with 4 other departments involved: Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Transport Canada, Public Services and Procurement Canada, and Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada. |

|

December 2021 |

In his mandate letter to the Minister of Environment and Climate Change, the Prime Minister lists objectives to achieve the commitment of zero plastic waste by 2030. |

These objectives build on the charter and the action plan. |

|

2022 |

To continue to fulfill its commitments, the federal government begins Phase 2—Advancing a Circular Plastics Economy for Canada Horizontal Initiative. |

The federal government earmarks around $200 million to be spent on this second phase of the initiative from 2022 to 2027. Phase 2 is to focus on several activities, such as researching the effects of microplastics on human health and monitoring plastic pollution in water systems. Three organizations are added to help deliver the initiative: Statistics Canada, Health Canada, and National Research Council Canada. |

Source: Adapted from information provided by Environment and Climate Change Canada

3.5 This undertaking is formally designated by the government as a horizontal initiative. This means that multiple organizations must work together to achieve shared outcomes. We examined 16 of the 44 activities from both phases of the horizontal initiative. About half of the total funding for the initiative was to be spent on these 16 activities. These activities involved 4 out of the total 8 organizations participating in the initiative. They ranged from a program to retrieve abandoned and lost (“ghost”) fishing gear and innovate fishing gear technology to researching and monitoring plastic pollution in Canada’s North.

3.6 The responsibility for waste management in Canada is shared among federal, provincial, territorial, and municipal governments. All these levels of government are therefore involved in contributing to the goal of reducing plastic waste. The federal government

- regulates the transboundary movements of hazardous waste and recyclable materials

- negotiates and reports on international agreements

- prevents pollution and manages pollutants and wastes through the authorities in the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999

- regulates waste management on federal lands

- conducts scientific research, collects data, and makes these available to the public

- funds infrastructure and innovation

3.7 Provincial and territorial governments approve, license, and monitor waste management operations, such as incinerators and landfills. They also implement extended producer responsibility and stewardship regulations, policies, and programs. Extended producer responsibility is a policy where businesses that produce plastic products are required to pay for the cost of their products’ collection, recycling, and disposal. Municipal governments collect, recycle, compost, and dispose of household waste.

3.8 Of the 8 federal departments and agencies involved in the zero plastic waste horizontal initiative, we audited 4 key organizations: Environment and Climate Change Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, and Statistics Canada.

3.9 Environment and Climate Change Canada. This department is responsible for developing and implementing measures under federal jurisdiction to prevent and reduce the release of plastics into the environment. It also monitors plastics levels in air, water, soil, and wildlife. It is to promote and enforce compliance with federal environmental laws and regulations related to plastic items. In addition, it is to implement and support actions and programs for preventing and reducing plastic pollution and waste and for recovering the value of waste plastics. Its lead role in the zero plastic waste horizontal initiative requires it to coordinate, collaborate, and consult with other federal government organizations, provinces and territories, Indigenous partners, non‑governmental organizations, industry partners, international partners, and other stakeholders.

3.10 Fisheries and Oceans Canada. This department’s mandate is to protect and restore Canadian oceans and coasts. An activity under this mandate is to expand the Ghost Gear Program, in which fishers and others are to clean up lost and abandoned fishing gear and other plastics in oceans. The department also works on improvements to data collection, lost and retrieved gear reporting systems, regulatory review, and the promotion of sustainable gear and best practices.

3.11 Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada. This department houses the Northern Contaminants Program secretariat. Under the program, the department is responsible for supporting the coordinated generation, collection, and management of scientific and environmental data and Indigenous knowledge pertaining to plastics in the environment and wildlife.

3.12 Statistics Canada. This agency is responsible for developing and publishing the physical flow account for plastic material. This account estimates the flow of plastics through the Canadian economy. This means estimating the amount of plastics produced each year and then tracking whether they are used, disposed of as waste, or recycled. By establishing accurate baselines and data on the presence of plastics, this tool is intended to help measure progress toward the zero plastic waste target and help develop policy.

Focus of the audit

3.13 This audit focused on whether key federal organizations led by Environment and Climate Change Canada were on track to achieve their intended contributions to the Canada‑wide goal of reaching zero plastic waste by 2030 to reduce the impact of plastic pollution on the environment.

3.14 This audit is important because plastic pollution causes damage to wildlife and their habitats in Canada and globally. On land and sea, species can get tangled in plastic waste and die of starvation or choke on the waste itself. Wildlife can also die as a result of ingesting plastic waste. Plastics contaminate food chains and weaken the resilience of ecosystems. Additionally, there are concerns about the adverse effects of plastic pollution on human health.

3.15 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings and Recommendations

Despite some delays, the implementation of waste-reduction activities was mainly proceeding as intended

3.16 This finding matters because any serious delays in implementing activities and any significant shortcomings in reducing plastic waste in landfills and in the ocean would result in continuing harmful environmental effects.

Good progress in implementing selected activities of the horizontal initiative

3.17 We assessed the implementation progress of 16 activities (out of the initiative’s total 44 activities). We found that 11 had begun achieving results for the initiative (Exhibit 3.4).

Exhibit 3.4—Eleven of the 16 activities we sampled had begun achieving results for the initiative as of September 2023

| Activity (phase) | Responsible entities | Results |

|---|---|---|

|

Canada’s Plastics Science Agenda: Researching knowledge gaps and improving the monitoring and understanding of plastics and microplastic pollution in the Arctic (phase 1) |

Environment and Climate Change Canada and Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada |

|

|

Research and monitoring of plastic pollution in Canada’s North (phase 2) |

Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada |

|

|

Ghost Gear Fund (phases 1 and 2) |

Fisheries and Oceans Canada |

|

|

Industry partnerships and voluntary agreements (phase 1) |

Environment and Climate Change Canada |

|

|

Community‑led initiatives (phase 1) |

Environment and Climate Change Canada |

|

|

Canadian Plastics Innovation Challenges (phase 1) |

Environment and Climate Change Canada |

|

|

Developing methodology for measuring plastic usage and plastic waste through Statistics Canada surveys (phases 1 and 2) |

Statistics Canada |

|

|

Developing guidance to facilitate consistent extended producer responsibilityNote 2 policies and programs for plastics (phase 1) |

Environment and Climate Change Canada |

|

|

Developing national standards and performance requirements for sustainable plastics and alternatives (phase 1) |

Environment and Climate Change Canada |

|

3.18 We found that the remaining 5 of our 16 sampled activities had completed or were developing preliminary requirements for implementation (Exhibit 3.5).

Exhibit 3.5—Five of the 16 activities we sampled had completed or were developing preliminary requirements for implementation as of September 2023

| Activity (phase) | Responsible entity | Preliminary requirements completed or in development |

|---|---|---|

|

Developing a federal public plastics registry (phase 2) |

Environment and Climate Change Canada |

|

|

Developing measures for additional single‑use plastics (phase 2) |

Environment and Climate Change Canada |

|

|

Supporting innovative solutions for reducing waste in key sectors (phase 2) |

Environment and Climate Change Canada |

|

|

Developing and implementing recycled content regulatory requirements for plastic products and packaging (phase 2) |

Environment and Climate Change Canada |

|

|

Research and monitoring to detect and characterize plastics (phase 2) |

Environment and Climate Change Canada |

|

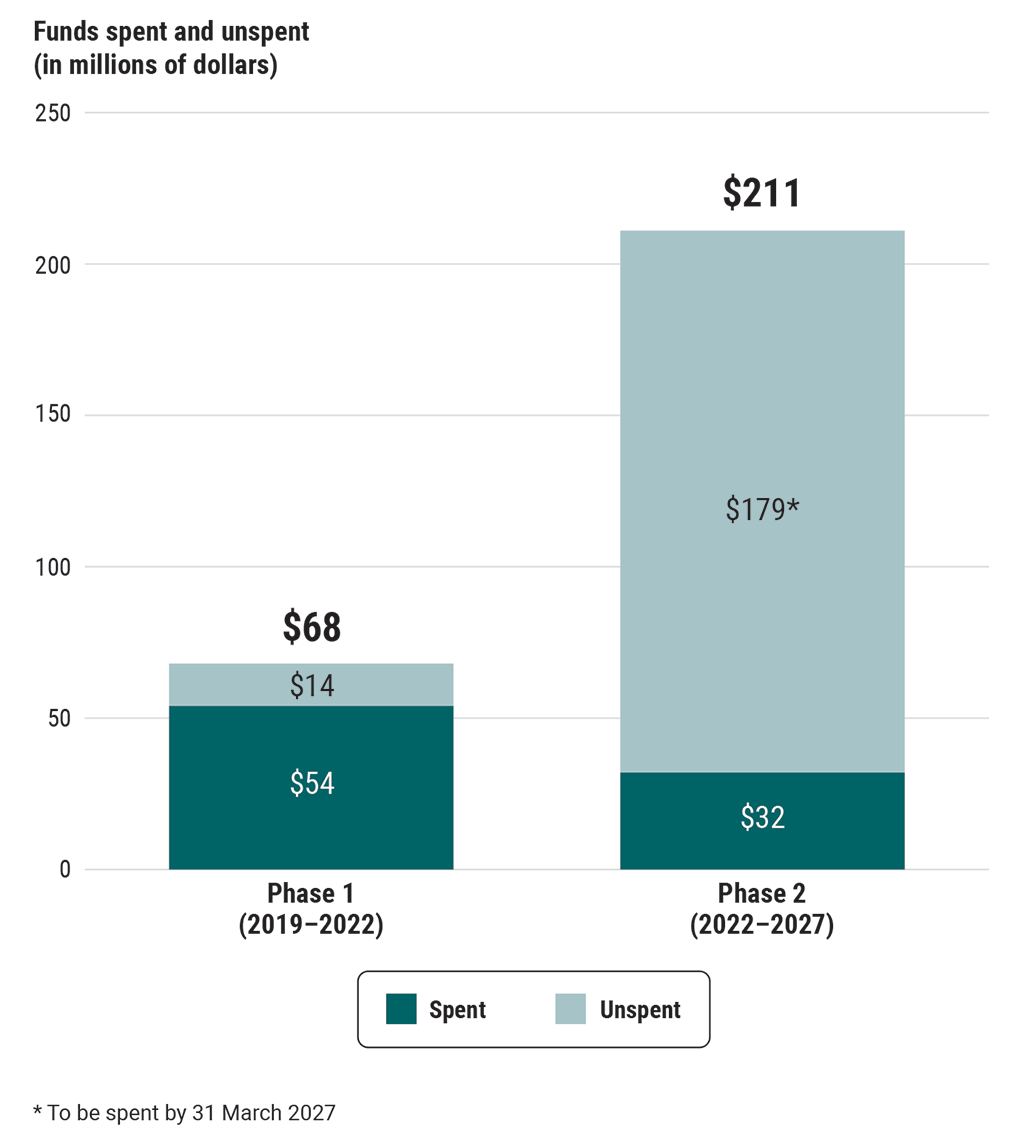

3.19 Funding for the 2 phases of the initiative totalled $279 million. We found that as of 31 March 2023, most of the funding for phase 1 had been spent (Exhibit 3.6). The rest of the funding is to be spent by the end of phase 2, which is 31 March 2027.

Exhibit 3.6—As of 31 March 2023, $86 million of the total initiative funding of $279 million had been spent to carry out activities

Source: Based on information from Environment and Climate Change Canada

Exhibit 3.6—text version

This bar graph shows the amount of spent and unspent initiative funding for phase 1 (2019 to 2022) and phase 2 (2022 to 2027) as of 31 March 2023.

Of the $68 million of funding for phase 1, $54 million was spent and $14 million was unspent.

Of the $211 million of funding for phase 2, $32 million was spent and $179 million was unspent but is to be spent by 31 March 2027.

Environment and Climate Change Canada coordinated with other federal organizations to launch the initiative

3.20 This finding matters because Environment and Climate Change Canada cannot achieve the initiative’s goal alone. The amount of waste being generated and the ambitious goal of zero plastic waste made it crucial for the department to coordinate effectively with key federal stakeholders so that the initiative could proceed.

Strong alignment between waste-reduction activities and previously stated priorities

3.21 We found that all of the activities of phase 1 and phase 2 of the initiative corresponded directly to the priorities identified in the action plan for the Canada‑wide Strategy on Zero Plastic Waste. This strong alignment was in keeping with the federal government’s commitments to the action plan and the strategy developed by the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment.

Clear roles and responsibilities in the initiative’s governance structure

3.22 We found that the governance structure established by Environment and Climate Change Canada for the initiative had identified clear roles and responsibilities to manage decision making across all federal organizations. It included 3 interdepartmental oversight committees with set processes to follow for meetings and decision making. We found that, although some changes were made to the structure in phase 2, the terms of reference for the committees continued to be clear and thorough on accountabilities and decision-making processes. We also found that committees met as frequently as planned.

3.23 We found that the committees had representation from the relevant federal organizations. In addition to the 5 partners from the phase 1 launch (Environment and Climate Change Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Transport Canada, Public Services and Procurement Canada, and Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada), the committees had representation from a wide range of other departments and agencies that participated voluntarily to support a whole‑of‑government approach.

3.24 We found that the initiative’s 5 partners from the phase 1 launch established clear accountability mechanisms by requiring regular reporting. All of the organizations we audited had quarterly reporting processes that they followed.

Key federal organizations did not yet measure how much the horizontal initiative was helping Canada reach zero plastic waste

3.25 This finding matters because not measuring the horizontal initiative’s progress toward zero plastic waste would result in decision makers not knowing whether they are on the right track and whether they need to take corrective actions. Stakeholders include all Canadians, who, to differing degrees, are affected by and involved in plastic production, consumption, and disposal. They also include the many organizations and governments that must work together in the complex undertaking of reaching zero plastic waste.

3.26 When the initiative began in 2019, the most recent economic data to estimate the amount of plastic waste in Canada and where it ended up was for 2016. The data was compiled in a study commissioned by Environment and Climate Change Canada and published in 2019. To improve data on plastic waste, Statistics Canada began developing and publishing the physical flow account for plastic material. This account estimates the tonnes of plastic in Canadian products every year and identifies where they end up.

3.27 The initiative’s activities are to be monitored and reported on in 2 ways. First, in quarterly reporting, organizations are required to provide Environment and Climate Change Canada with the following information for its results tracking tables: the high‑level shared outcome for each organization’s activities and the activities’ performance indicators, target, target date, data source, and data frequency. Tracking performance information in this way is meant to enable decision makers to assess the progress of activities on the basis of whether targets are met. Second, Environment and Climate Change Canada is to publish an annual departmental results report that includes the initiative’s results.

3.28 The initiative expects to achieve 2 key results. It has set certain targets and indicators aligned with those results (Exhibit 3.7).

Exhibit 3.7—Two key results for the initiative and associated targets and indicators

| Result | Target | Indicator |

|---|---|---|

| Plastics are kept out of the environment. | Reduction in plastic waste from a baseline to be identified in 2024 | Amount (in tonnes) of plastics entering Canada’s natural environment from both land and water sources |

| Plastic is diverted from landfills and incinerators. | Declining trend from 2018 baseline to be achieved by 2030 | Amount (annual, in tonnes) of plastic waste disposed of at landfills and incineration sites across Canada |

Source: Adapted from information provided by Environment and Climate Change Canada

Missing information on the amount of plastic waste and other baselines

3.29 We found that information on the amount of plastic waste that is leaked into the environment was incomplete. In 2019, a study commissioned by Environment and Climate Change Canada concluded that around 1% of Canada’s plastic waste in 2016 entered the environment as pollution. The study recognized that this number was an estimate. It was drawn from a study that did not include plastic pollution from aquatic-based sources (that is, in or around bodies of water). For example, it did not capture plastic pollution from the shipping sector and lost or discarded fishing gear.

3.30 We also found a time lag of 3 years and 3 months in Statistics Canada’s publication of plastic waste estimates. The first physical flow account for plastic material was published in November 2021, with additional releases in March 2022, June 2022, and March 2023. At the time of our audit, Statistics Canada was expected to report next in March 2024. This release was expected to present data only up to 2020. If the time lag is not shortened, the information on 2030 plastic waste will not be available until 2034.

3.31 The federal government recognized that it had few other sources of data to determine whether it was on the right track to achieve its 2030 goal. We found that it had several data projects in development to improve this situation. For example, to add more detail to the data supplied by Statistics Canada, Environment and Climate Change Canada was developing a federal public plastics registry, with first reporting expected by January 2025. The registry would require producers to report annually on the quantity and types of plastic they place on the Canadian market, how that plastic moves through the economy, and how it is managed at the end of its life.

3.32 We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada twice issued a call for consultants to bid on a contract to quantify the amount of plastic pollution entering the environment, measure Canada’s progress toward the 2030 goal, and identify opportunities to help achieve the goal. The first attempt was not successful, putting the planned work behind schedule. The second attempt was successful, and the department awarded a contract in fall 2023. Given the late start, the work required under the contract was reduced to cover 2023–40, rather than 2022–50 as originally planned. The contract also required the consultant to establish, by the end of March 2024, a 2024 baseline for plastic pollution leaked into the environment. Progress can then be measured against it. The consultant was also expected by that date to deliver a modelling methodology and projections on progress toward the zero plastic waste goal. The modelling was to assess and incorporate the impact of policy measures and other actions in reducing plastic waste and pollution. Progress reports were expected to be released by the department in 2024 and 2027.

3.33 We also found that, despite these data projects, Environment and Climate Change Canada had no clear data framework to respond to data and knowledge gaps. There were initiatives underway, but they were pursued independently without checking whether they overlapped or collectively were sufficient to ensure that all gaps were closed. Such a framework would identify all the data requirements to progress proactively toward the 2030 zero plastic waste goal. This would assist organizations in planning and prioritizing information gathering.

3.34 To have more information about results and determine whether it is using the right tools to reduce plastic waste, Environment and Climate Change Canada should develop a data framework to compile existing information-gathering initiatives and identify the gaps in the information to measure progress toward the 2030 zero plastic waste goal. Once these are identified, the framework should guide organizations on focusing on and prioritizing information gathering.

The department’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Lack of measurement and reporting of long‑term desired result

3.35 We found that the initiative’s targets and indicators (as listed in Exhibit 3.7) were not aligned with the initiative’s long‑term desired result. Although the horizontal initiative refers to “zero” plastic waste (beginning from the phase 1 launch), the initiative’s targets referred only to “reduction” and “declining trend” and were not measuring against the end goal of zero plastic waste and setting a pathway to reach it.

3.36 We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada’s annual departmental results reports gave parliamentarians and Canadians information mostly on short‑term progress without reporting on the long‑term target or desired result. For example, long‑term targets for the initiative are to steadily reduce the plastic waste deposited annually in landfills and the environment from a 2018 baseline of about 4 million tonnes. The department set the 2022 target at 300 tonnes of plastic waste diverted from landfills and the environment. It reported a 2022 result of 325 tonnes diverted. While this met the short‑term target, the department did not report that the total weight of diverted plastic waste from 2019 to 2022 was a reduction of less than 0.01% against the 2018 baseline.

3.37 We further found that the annual results reports did not clearly state the instances where targets were not met. They also did not clearly state the reasons why. Examples included the following:

- A target for a plastics information activity was for 100% of the gaps in knowledge about the distribution and impact of plastics to be filled by March 2022. The 2022 results report discussed the plastics knowledge collected. However, it did not state whether 100% of the gaps were filled and, if not, the reasons why the target was not met.

- A target for an activity to improve plastic product design and reuse was for 100% of specified sectors to adopt measures to make plastics more sustainable and less prone to waste by March 2022. The specified sectors included textiles, the automotive industry, health care, and agriculture. The 2022 results report discussed studies, tools, pilots, and roadmaps developed for this activity. However, it did not state whether all sectors adopted the measures and, if not, the reasons why the target was not met.

3.38 To improve the transparency of results reporting and provide the information needed to correct course when necessary, Environment and Climate Change Canada should in its annual departmental results reports

- include an overall assessment of the progress of the initiative toward achieving its long‑term desired results

- include assessments of the progress of individual activities toward achieving the long‑term desired results of the initiative

- clearly state the instances where targets were not met and explain the reasons why

The department’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

No monitoring and reporting of progress in meeting gender‑based analysis plus criteria

3.39 We found several instances where the organizations we audited had identified how gender and other identity factors, such as having a disability or being Indigenous, should be taken into account when designing their activities. However, we found that these considerations had not been incorporated into performance measures within Environment and Climate Change Canada’s results tracking tables. This meant that there were no expectations for monitoring or reporting on these considerations as organizations implemented their activities. Without monitoring or reporting, organizations could not demonstrate whether they were addressing the gender-based analysis plus concerns they had identified.

3.40 We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada was not collecting or monitoring the disaggregated performance data that is necessary to track progress in meeting the gender-based analysis plus criteria and objectives. Disaggregated performance data looks at trends and patterns for specific populations grouped according to characteristics, such as where they live, their age, whether they have reduced mobility, and whether they are part of a racialized group.

3.41 To track progress in meeting gender-based analysis plus criteria and objectives, Environment and Climate Change Canada should

- in the data framework recommended earlier (paragraph 3.34), identify the disaggregated performance data it needs

- in its results tracking tables, translate the criteria and objectives into performance indicators, targets, and outcomes that organizations should then monitor and report on progress made

The department’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

The lack of proactive risk management increased the chances of waste-reduction activities not succeeding

3.42 This finding matters because the work needed to achieve the goal of zero plastic waste by 2030 is complex. Therefore, potential risks need to be anticipated early and addressed quickly for the goal to be met on time.

3.43 The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat provides a framework and guidance for risk management. The guidance directs government organizations to assess risks at every level and in every sector on an ongoing basis. Organizations then should consolidate the results at a corporate level, communicate them, and ensure adequate monitoring and review. The consolidated results are intended to help organizations make informed decisions to address risk.

3.44 To obtain funding, federal organizations prepare submissions to the Treasury Board that include risk tables identifying key risks for their initiatives. The tables also identify the risks’ probability, impact, and level; the organizations’ risk response; and the risk level remaining after the response is used.

3.45 Since the initiative began, organizations have been required to prepare quarterly update reports that feed into quarterly dashboards for oversight committees. The reports must include information on risks.

No consolidation of risk information to enable monitoring, review, and course correction

3.46 We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada did not have a complete listing of all identified risks. Different risks were captured in various documents, and some were not documented at all. These included risks identified through feedback from public consultations. The department published these risks in What We Heard reports (reports summarizing the feedback), but not all consultations resulted in a report.

3.47 We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada did not have a consolidated risk document to capture risk data and information, such as in a formal risk register or framework. Undertaking risk management without having consolidated all the risks has hindered

- the monitoring of risk responses so they could be adjusted as needed

- the tracking of risk trends and triggers over time

- the determination of who is responsible for the risks for transparency and accountability

- the addition and removal of risks as circumstances change

3.48 Having a formal risk register or framework is especially important for a horizontal initiative, where risks interact and overlap throughout activities and organizations. For example, during phase 1 of the initiative, the Governor in Council,Definition 1 on the recommendation of the Minister of Health and the Minister of Environment and Climate Change, used an order‑in‑council to designate “plastic manufactured items” as a toxic substance by adding them to Schedule 1 of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999. This allowed initiative activities, such as banning certain harmful single‑use plastics through regulations, to proceed. An industrial coalition challenged the designation in the Federal Court. The challenge put at risk the regulatory activities that depended on the designation and also risked delaying the initiative as a whole. These risks could have been managed in a consolidated way with a formal risk register that included identified risk responses. The Federal Court’s ruling was announced after the period of our audit, on 16 November 2023. It ruled that the order‑in‑council was both unreasonable and unconstitutional, quashing the order retroactively and declaring it invalid and unlawful. At the time we were preparing this report, this decision was currently being appealed to the Federal Court of Appeal. Although Environment and Climate Change Canada considered that the risks identified in the initiative were not high enough to warrant ongoing consolidated risk management, examples like this one support the value of a consolidated approach.

3.49 Environment and Climate Change Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, and Statistics Canada should complete the identification of all risks at every level of the initiative and should review and monitor them on an ongoing basis.

Response of each entity. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

3.50 Environment and Climate Change Canada should consolidate the results of the completed risk identification and communicate them among the partners in accordance with the risk management framework required by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

The department’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Lack of monitoring of the effectiveness of risk responses

3.51 We chose a sample of 9 risks identified by the 4 organizations we audited, and we examined the responses they developed and their overall management of the risks. We found that the organizations were not all consistently and formally monitoring and reporting on whether the responses were having any effect on reducing or overcoming the risk.

3.52 We also found many instances where organizations did not set target dates for when risk responses should be completed. This is a key element for monitoring risks and risk responses. It is especially important for the risk of not having needed information. Instead of setting target dates for getting needed data, organizations planned to simply keep on trying to get the data. For example, Statistics Canada identified the risk of not having needed information for its annual physical flow account for plastic material. Some of this information was to come from an annual report from Environment and Climate Change Canada that the department was considering cancelling. It had deemed that the data collected for the report from municipalities was not consistent. At the time of our audit, the department and Statistics Canada were in ongoing discussions on how to get the needed data. Setting target dates and monitoring progress against the dates could focus and speed up the 2 organizations’ efforts to respond to this risk.

3.53 We found that the lack of a formal monitoring process was part of a larger issue of reactive, rather than proactive, risk management. Environment and Climate Change Canada informed us that it did not have formal risk frameworks or matrices because of the absence of significant risk issues to date. We found that the department was using this reactive response of waiting for a risk to present itself even for known past risks. For example, the COVID‑19 pandemic disrupted and, in some cases, halted environmental research and monitoring. The department noted that, in response to the pandemic, laboratory practices evolved to keep work going. However, we found no evidence that the department was planning for alternative approaches and practices in response to another unforeseen risk like the pandemic. Instead, it assumed that they would evolve of their own accord.

3.54 Environment and Climate Change Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, and Statistics Canada should put mechanisms in place to monitor the effectiveness of risk responses. This should include target dates for tracking progress on the completion of risk responses.

Response of each entity. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Conclusion

3.55 We concluded that key federal organizations led by Environment and Climate Change Canada began implementing activities to contribute to the Canada‑wide goal of reaching zero plastic waste by 2030. However, they had still not gathered all the information needed on plastic waste and had not yet fully established the targets and monitoring systems to track their progress against the goal. Until this is done, they will not know whether they are on track to meeting the goal.

3.56 Successfully reducing plastic pollution requires the collaboration of the federal government with partners, such as provinces, territories, municipalities, and the private sector. The initiative’s dependence on so many partners makes it all the more important for the key federal organizations to have proper tracking systems in place.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on Canada’s zero plastic waste horizontal initiative. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs and to conclude on whether the horizontal initiative complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements, set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada applies the Canadian Standard on Quality Management 1—Quality Management for Firms That Perform Audits or Reviews of Financial Statements, or Other Assurance or Related Services Engagements. This standard requires our office to design, implement, and operate a system of quality management, including policies or procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether key federal organizations led by Environment and Climate Change Canada were on track to achieve their intended contributions to the Canada‑wide goal of reaching zero plastic waste by 2030 to reduce the impact of plastic pollution on the environment.

Scope and approach

The audit focused on the federal government’s horizontal initiative, led by Environment and Climate Change Canada, which aims to deliver the federal contribution to the Canada‑wide goal of reaching zero plastic waste by 2030. It examined federal activities and excluded the actions of other levels of government while acknowledging that the actions of other levels of government play a vital role in achieving the waste-reduction goal.

The following organizations were audited:

- Environment and Climate Change Canada

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada

- Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada

- Statistics Canada

The audit methodology included document reviews, file reviews, data analysis, and interviews with organization officials. It also included a sample of Canada’s zero plastic waste horizontal initiative activities. We examined 16 activities covering both phases of the horizontal initiative, 9 of which were grant and contribution activities. For those activities, 43 files were reviewed using a representative sampling approach.

We did not examine activities for which other organizations were responsible under the horizontal initiative.

The matters examined in this audit relate to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) and 1 associated target:

- target 12.5: “By 2030, substantially reduce waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling and reuse”

This international target has been incorporated into the 2022 to 2026 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy as part of Canada’s commitments to waste diversion from landfills.

The matters examined also relate to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 14 (Life Below Water) and 1 associated target:

- target 14.1: “By 2025, prevent and significantly reduce marine pollution of all kinds, in particular from land‑based activities, including marine debris and nutrient pollution”

This international target has also been reflected in the 2022 to 2026 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy as part of Canada’s commitment to conserving its coastal and marine areas, particularly as they are home to the world’s longest coastline.

Criteria

We used the following criteria to conclude against our audit objective:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Environment and Climate Change Canada has adequately planned and coordinated with other federal organizations to implement the horizontal initiative aiming to deliver on Canada’s zero plastic waste goal by 2030. |

|

|

Environment and Climate Change Canada is effectively implementing with other federal organizations the selected activities under the horizontal initiative aiming to deliver on Canada’s zero plastic waste goal by 2030. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period from 1 January 2018 to 30 September 2023. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies. However, to gain a more complete understanding of the subject matter of the audit, we also examined certain matters that preceded the start date of this period.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 16 February 2024, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

This audit was completed by a multidisciplinary team from across the Office of the Auditor General of Canada led by Nicholas Swales, Principal. The principal has overall responsibility for audit quality, including conducting the audit in accordance with professional standards, applicable legal and regulatory requirements, and the office’s policies and system of quality management.

Recommendations and Responses

Responses appear as they were received by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada.

In the following table, the paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report.

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

3.34 To have more information about results and determine whether it is using the right tools to reduce plastic waste, Environment and Climate Change Canada should develop a data framework to compile existing information-gathering initiatives and identify the gaps in the information to measure progress toward the 2030 zero plastic waste goal. Once these are identified, the framework should guide organizations on focusing on and prioritizing information gathering. |

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. Environment and Climate Change CanadaECCC will develop a data framework to: 1) compile existing information gathering activities; and, 2) identify remaining data gaps in the information to measure progress towards the 2030 zero plastic waste goal. ECCC will finalize this framework by March 31, 2025. |

|

3.38 To improve the transparency of results reporting and provide the information needed to correct course when necessary, Environment and Climate Change Canada should in its annual departmental results reports

|

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. The department will include information on the progress of the initiative, based on available data, in the departmental results report starting in the 2024–25 report. |

|

3.41 To track progress in meeting gender-based analysis plus criteria and objectives, Environment and Climate Change Canada should

|

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. Using the information gathered on Gender-based analysis plusGBA+ when the initiative was developed and informed by indicators used in other Environment and Climate Change CanadaECCC programs, the department will develop GBA+ indicators to track progress annually. The indicators will be developed by March 31, 2025 and will be reported in the annual departmental results report. |

|

3.49 Environment and Climate Change Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, and Statistics Canada should complete the identification of all risks at every level of the initiative and should review and monitor them on an ongoing basis. |

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. Environment and Climate Change CanadaECCC has added quarterly risk reporting to existing partner department risk monitoring processes. ECCC will also review the risks in line with the development of its corporate risk profile and ensure that any new risks are identified and included in risk monitoring and reporting mechanisms. Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response. Agreed. Fisheries and Oceans Canada has developed a process to identify risks at all levels for the Zero Plastic Waste initiative. Officials with the Ghost Gear Program identified risks as part of program delivery, including up to the final expenditures of Zero Plastic Waste funding associated with the Ghost Gear Fund, the Grants and Contributions portion of the Ghost Gear Program. Final results are currently being collated. Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada’s response. Agreed. Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada will adjust the 2025 Call for Proposals to include a risk identification section to be completed by applicants, and the program’s Management Committee will review these risks annually at its mid‑year meeting. Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada will also work with Environment and Climate Change Canada to identify risks at the initiative level. Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada will work with Environment and Climate Change Canada to review and monitor the identified risks on an ongoing basis through an agreed upon mechanism. The department’s projected timeline to implement this recommendation is 12 months. Statistics Canada’s response. Agreed. Statistics Canada has worked to identify potential risks at every level of the initiative. The most pressing risk for the Physical Flow Account for Plastic Material (PFAPM) is that it relies on many data sources, such as the Supply and Use tables, Statistics Canada surveys, and administrative data sources, which they do not control. Delays or cancellations of these data sources would require the PFAPM team to pivot to other sources. Also, due to the highly specialized nature of the PFAPM, the other most significant risk is losing subject matter knowledge due to staff turnover. Environment and Climate Change Canada has added monitoring of risks and mitigation measures into the quarterly Plastics Horizontal Initiative’s progress report, to which Statistics Canada will contribute on a quarterly basis. [Timeline: This information will be reported to Environment and Climate Change Canada for the first time in the Q3 report, due January 2024.] |

|

3.50 Environment and Climate Change Canada should consolidate the results of the completed risk identification and communicate them among the partners in accordance with the risk management framework required by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. |

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. The new quarterly risk reporting was developed in accordance with the Treasury Board risk management framework. Departments are required to provide a risk statement, the anticipated risk impact, the current status and potential mitigation actions, the initial risk level reported in the submission and whether that risk level has changed. The department will assess the effectiveness of this process in 2025 to ensure that risk information is communicated appropriately to support informed decision-making. |

|

3.54 Environment and Climate Change Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, and Statistics Canada should put mechanisms in place to monitor the effectiveness of risk responses. This should include target dates for tracking progress on the completion of risk responses. |

Environment and Climate Change Canada’s response. Agreed. The department will collaborate with the entities identified to review current risk monitoring and tracking processes to ensure that mitigation measures are having their intended impacts. Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response. Agreed. Mechanisms were in place which allowed Fisheries and Oceans CanadaDFO to monitor the effectiveness of risk responses including up to the final expenditures of Zero Plastic Waste funding associated with the Ghost Gear Fund, the Grants and Contributions portion of the Ghost Gear Program. Specifically, calls for proposals with specific open and close dates allowed Fisheries and Oceans Canada to gauge how well communication strategies had engaged harvesters by tracking the number of proposals submitted during the call for proposals window. Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada’s response. Agreed. The Northern Contaminants Program will formalize its risk assessment approach through the project-level mid‑year reporting and proposal update processes, and develop a mechanism to track risk responses and their effectiveness. This formalized approach could improve the identification of risks and ensure timely and more effective interventions across the horizon of a project. The program’s Management Committee will review the risk responses twice per year, at its spring and mid‑year meetings. The department’s projected timeline to implement this recommendation is 18 months. Statistics Canada’s response. Agreed. Statistics Canada will put mechanisms in place to monitor the effectiveness of risk responses, as required. For example, Statistics Canada is currently closely monitoring its data sources and has been developing plans about what alternative data sources could be used as a substitute if current sources become unavailable. In terms of mitigating the risk of potential staff turnover, Statistics Canada plans to, for example, (i) continue to automate aspects of the compilation process, to help ensure that any new staff will be able to compile the account effectively; and (ii) develop a series of guidance documents to ensure that the detailed knowledge required to run the account can be efficiently transferred to new staff. Statistics Canada will set target dates for these and other risks and carefully track progress for these risks, as well as any other identified risks that come to the forefront during the project. Environment and Climate Change Canada has added monitoring of risks and mitigation measures into the quarterly Plastics Horizontal Initiative’s progress report, to which Statistics Canada will contribute on a quarterly basis. [Timeline: This information will be reported to Environment and Climate Change Canada for the first time in the quarter 3Q3 report, due January 2024.] |