2021 Report of the Auditor General of Canada to the Legislative Assembly of NunavutFollow-up Audit on Corrections in Nunavut—Department of Justice

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

- Managing inmate rehabilitation

- Operating correctional facilities

- The way forward

- Conclusion

- COVID‑19

- About the Audit

- List of Recommendations

- Appendix—List of Recommendations Outstanding From 2015

- Exhibits:

Introduction

Background

1. Crime, including violent crime and family violence, is a significant issue in Nunavut. According to Statistics Canada, Nunavut had the highest adult incarceration rate (the average number of adults in custody per day for every 100,000 individuals in the adult population) among the provinces and territories in the 2018–19 fiscal year. The Government of Nunavut has identified a number of factors that contribute to the territory’s high crime rate, including low levels of educational attainment, overcrowded homes, poverty, addiction, and mental illness.

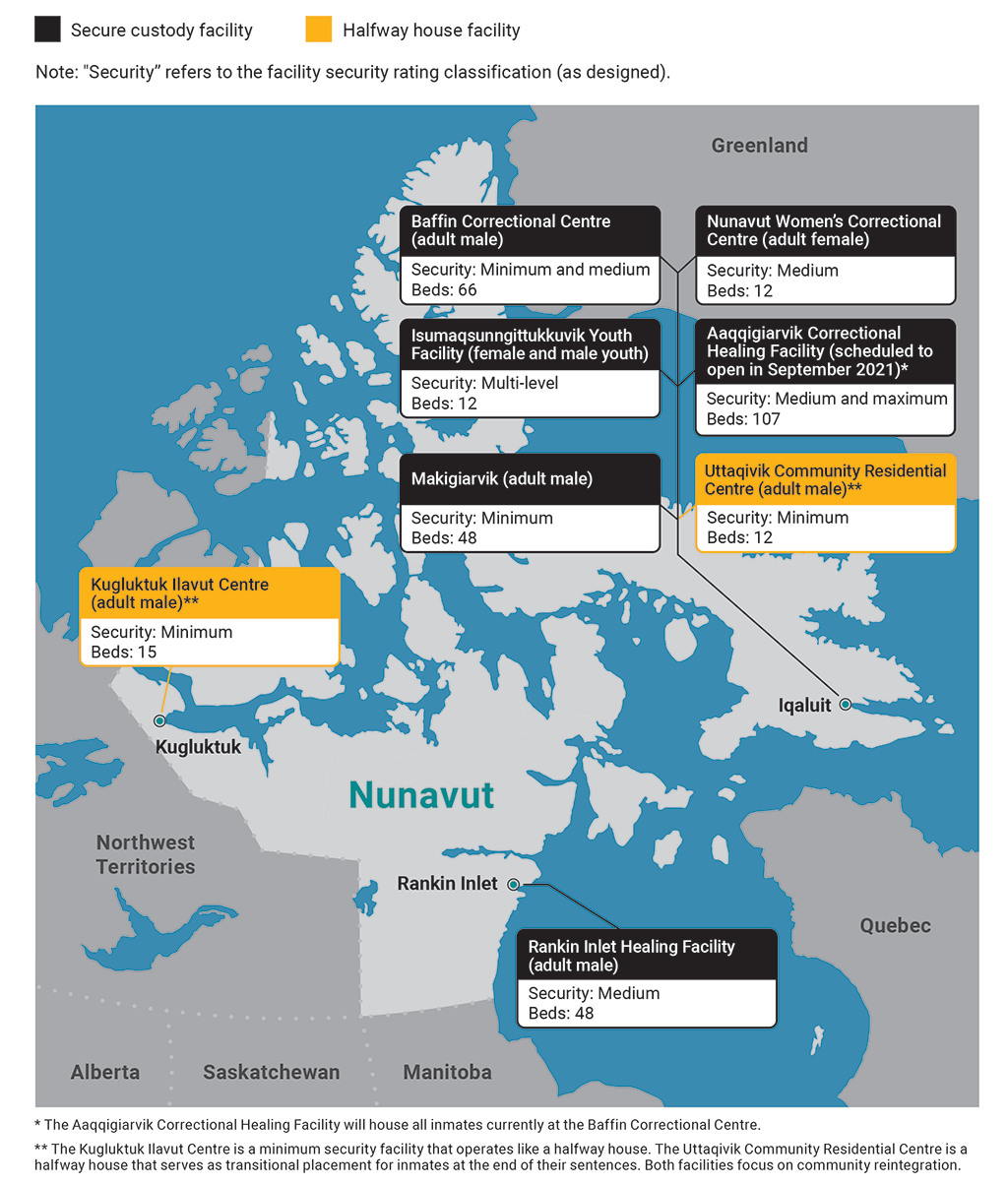

2. The Corrections Division of the Department of Justice in Nunavut operates 7 correctional facilities (Exhibit 1) with a new facility scheduled to open in September 2021. These facilities house inmates on remand (those charged with committing an offence who are in custody while awaiting trial) and inmates sentenced to a period of incarceration shorter than 2 years. Inmates serving sentences of 2 years or more are sent to federal facilities. According to Statistics Canada, between the 2014–15 and 2018–19 fiscal years, admissions into adult custody at Nunavut’s correctional facilities increased from 1,064 to 1,475 per year.

Exhibit 1—Nunavut’s correctional facilities

Source: Based on information from Nunavut’s Department of Justice

Exhibit 1—text version

This map shows the locations of Nunavut’s correctional facilities. It also shows the types of inmates housed at each facility, the facility security rating classification (as designed) of each facility, and the number of beds at each facility. Of the 8 facilities, 6 are located in Iqaluit, 1 is located in Kugluktuk, and 1 is located in Rankin Inlet.

There are 6 secure custody facilities:

- The Baffin Correctional Centre is in Iqaluit and houses adult male inmates. The facility security rating classification (as designed) is minimum and medium, and there are 66 beds.

- The Isumaqsunngittukkuvik Youth Facility is in Iqaluit and houses female and male youth inmates. The facility security rating classification (as designed) is multi-level, and there are 12 beds.

- The Makigiarvik facility is in Iqaluit and houses adult male inmates. The facility security rating classification (as designed) is minimum, and there are 48 beds.

- The Nunavut Women’s Correctional Centre is in Iqaluit and houses adult female inmates. The facility security rating classification (as designed) is medium, and there are 12 beds.

- The Rankin Inlet Healing Facility is in Rankin Inlet and houses adult male inmates. The facility security rating classification (as designed) is medium, and there are 48 beds.

- The Aaqqigiarvik Correctional Healing Facility is scheduled to open in Iqaluit in September 2021 and will house all inmates currently at the Baffin Correctional Centre. The facility security rating classification (as designed) will be medium and maximum, and there will be 107 beds.

There are 2 halfway house facilities:

- The Kugluktuk Ilavut Centre is in Kugluktuk and houses adult male inmates. The facility security rating classification (as designed) is minimum, and there are 15 beds.

- The Uttaqivik Community Residential Centre is in Iqaluit and houses adult male inmates. The facility security rating classification (as designed) is minimum, and there are 12 beds.

The Kugluktuk Ilavut Centre is a minimum-security facility that operates like a halfway house. The Uttaqivik Community Residential Centre is a halfway house that serves as transitional placement for inmates at the end of their sentences. Both facilities focus on community reintegration.

3. The vision of the Corrections Division is to be a dedicated and respectful workforce that respects Inuit societal values, represents the people of Nunavut, supports public safety, and offers innovative, culturally relevant programming for Nunavut residents in conflict with the law. The division’s budget for the 2020–21 fiscal year was $37.8 million (about 30% of the Department of Justice’s total budget).

4. The 1988 Corrections Act for Nunavut sets out the responsibilities of the Corrections Division. The division is responsible for delivering adult institutional services and community corrections programs throughout Nunavut. It is also responsible for the custodial detention of youth and their supervision in the community under the federal Youth Criminal Justice Act and the territorial Young Offenders Act.

5. This audit followed up on selected recommendations from the 2015 March Report of the Auditor General of Canada, Corrections in Nunavut—Department of Justice. In that audit, we found that the department had not provided inmates with the rehabilitation and reintegration services it was required to provide. We also found that it had not met its responsibilities for ensuring the safe and secure operation of the Baffin Correctional Centre and the Rankin Inlet Healing Facility.

Focus of the audit

6. This audit focused on whether the Department of Justice had made satisfactory progress on selected recommendations and observations that were made in our 2015 audit report on corrections in Nunavut and that related to managing inmate rehabilitation and operating correctional facilities.

7. This audit is important because providing programs and supports to inmates in a safe and secure environment helps promote their healing and reintegration into their communities.

8. Recommendations on new issues identified during this follow-up audit are provided throughout the report. Recommendations from 2015 that had not been addressed by the department are discussed at paragraphs 105 to 106. More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

9. Overall, we found that the Department of Justice still had significant work to do in managing inmate rehabilitation and operating correctional facilities. We noted progress in some areas, such as increased capacity to house male inmates. However, most of the issues found in this audit were raised in observations and recommendations in our 2015 audit. The department’s work to fully address these outstanding issues is ongoing.

10. Among the challenges facing the department, we found that adult inmates in secure custody facilities did not consistently receive case management services. In addition, the department struggled to provide these inmates with access to the range of programs and services, across facilities, needed to support inmates’ rehabilitation and eventual reintegration into the community. This includes access to mental health services.

11. The department made progress in correcting the causes of overcrowding and poor living conditions at the Baffin Correctional Centre. However, the capacity of the Nunavut Women’s Correctional Centre was inadequate for its needs and lacked space to adequately provide rehabilitation programs. The safety of inmates within the facilities was also a concern, as the department could not demonstrate that cell searches and fire drills and evacuations were completed as required across all facilities. However, 5 facilities carried out fire drills and evacuations as required during the 2020–21 fiscal year.

12. The Department of Justice adopted a new approach to segregation. However, staff were not trained on how to place and monitor inmates in segregation. Having proper procedures, training, management, and oversight are important to ensure that segregation placements are justified and that inmates are managed safely and remain in segregation for the shortest time possible.

13. Consistently high vacancy rates in critical staff positions affected the department’s ability to manage correctional facilities and ensure the safety of inmates and staff. The Corrections Division did not have a human resources plan to address challenges in recruitment and retention.

Managing inmate rehabilitation

The Department of Justice did not provide the case management services needed to help rehabilitate inmates

14. We found that since our 2015 audit, there continued to be gaps in case management services provided to inmates. We found that inmate needs assessments, case management plans, and release plans were not completed for most of the inmate files we examined. Further, the Department of Justice did not have a common set of standards and practices to guide case management, and staff were not given formal case management training. However, the department was taking steps to address these issues.

15. The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

- Lack of inmate needs assessments, case management plans, and release plans

- Recent actions taken to develop case management standards and training

16. This finding matters because case management services help inmates receive the rehabilitation they need while incarcerated and help them reintegrate into their community after their release.

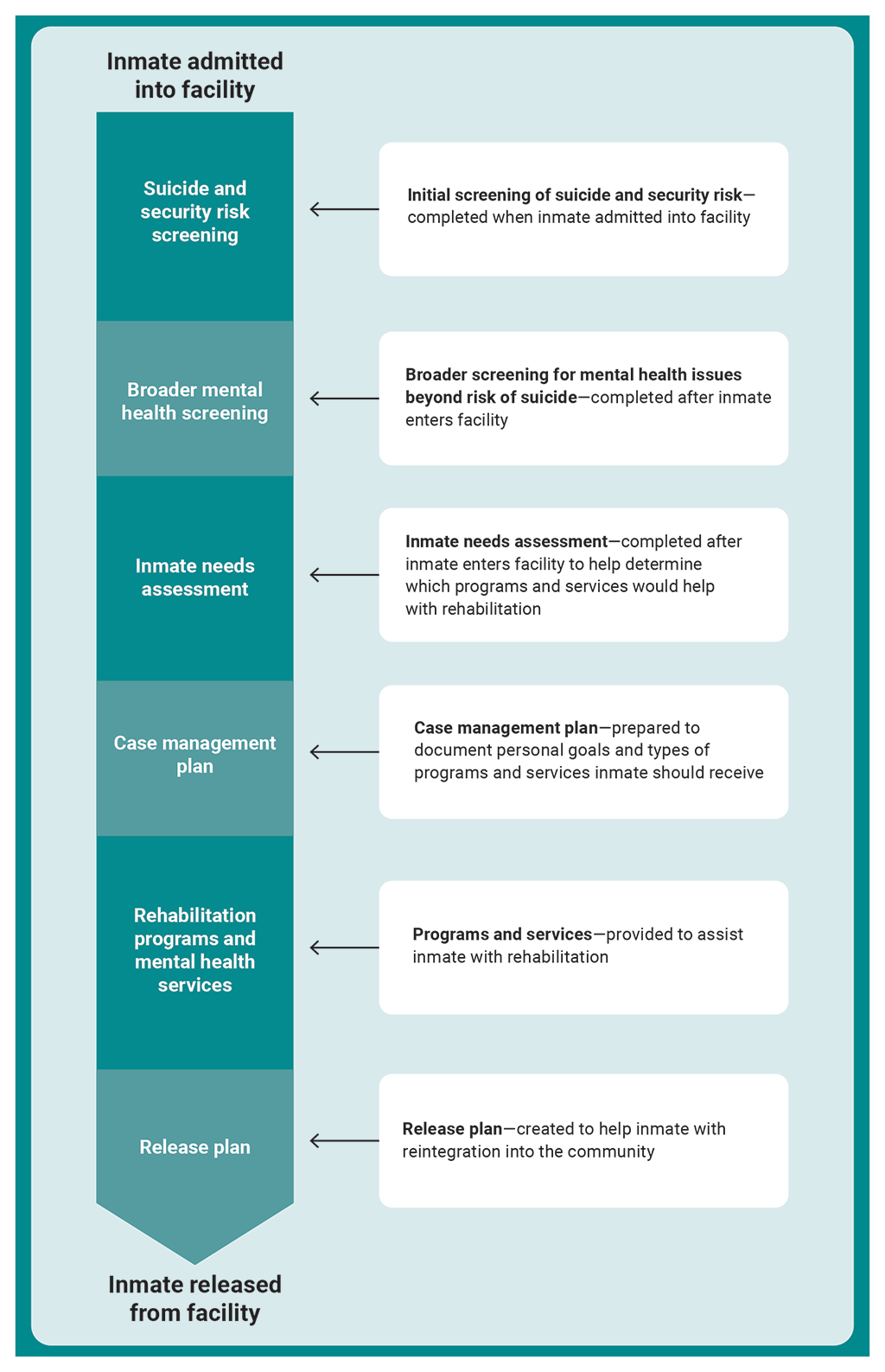

17. According to the Corrections Division Directives, when inmates are admitted to a correctional facility, they should receive case management services during their stay and right before their release. These services are meant to help identify and address any needs, health issues, and mental health challenges they may have and to support their release back into their community (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2—Several steps are included in the Corrections Division’s case management model

Source: Based on the Corrections Division Directives

Exhibit 2—text version

This flow chart shows the several steps included in the Corrections Division’s case management model.

After an inmate is admitted into a facility and before the inmate is released, there are several steps:

- The first step is a suicide and security risk screening. This initial screening of suicide and security risk is completed when the inmate is admitted into the facility.

- The second step is a broader mental health screening. This broader screening for mental health issues beyond the risk of suicide is completed after the inmate enters the facility.

- The third step is an inmate needs assessment. The inmate needs assessment is completed after the inmate enters the facility to help determine which programs and services would help with rehabilitation.

- The fourth step is a case management plan. The case management plan is prepared to document personal goals and types of programs and services the inmate should receive.

- The fifth step is providing rehabilitation programs and mental health services. These programs and services are provided to assist the inmate with rehabilitation.

- The sixth step is a release plan. The release plan is created to help the inmate with their reintegration into the community.

18. Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 26 and 105 to 106.

Lack of inmate needs assessments, case management plans, and release plans

19. In our 2015 audit, we found gaps in the case management services being provided to inmates at the Baffin Correctional Centre and the Rankin Inlet Healing Facility. For example, plans for guiding inmates’ rehabilitation had not been completed, and plans had not been developed for their release back to their community and to help them reintegrate. In this follow-up audit, we looked at case management services at the 4 adult secure custody facilities and continued to find weaknesses and gaps in how these services were delivered (Exhibit 3). We found that at the Baffin, Makigiarvik, and Rankin Inlet facilities, case management staff were not completing needs assessments or case management plans for most of the files we examined. However, needs assessments and case management plans were being completed for most of the files we examined at the Nunavut Women’s Correctional Centre.

Exhibit 3—The Department of Justice was not consistently completing key case management tasks

| Facility | Needs assessment conducted | Case management plan created |

|---|---|---|

| Baffin Correctional Centrenote * | 4 of 17 (24%) | 1 of 17 (6%) |

| Makigiarviknote * | ||

| Rankin Inlet Healing Facility | 2 of 9 (22%) | 2 of 9 (22%) |

| Nunavut Women’s Correctional Centre | 5 of 5 (100%) | 4 of 5 (80%) |

20. We saw examples of inmates who were incarcerated for several months at the Baffin and Rankin Inlet facilities and who received no case management services. This included inmates who were charged or convicted of violent offences. For example, for an inmate who served a 5-month sentence at the Baffin facility, and for another inmate who served a sentence at the Rankin Inlet facility for more than 9 months, there was no record of a needs assessment or case management plan, or any monthly progress reporting during their incarcerations.

21. In 2015, we found limited planning for the release of inmates at the Baffin Correctional Centre and the Rankin Inlet Healing Facility. Release planning is important as it is intended to help inmates reintegrate into the community. In this follow-up audit, we continued to find that release planning was limited across the 4 facilities we examined. We found that some release planning was done for 9 of the 17 sentenced inmate files we examined. In most cases, this was limited to documenting where the inmates were expected to reside after their release.

Recent actions taken to develop case management standards and training

22. In our 2015 audit, we found deficiencies in case management training. In this follow-up audit, we found no improvement. For example, we found that

- formal case management training was not mandatory nor provided to Corrections Division staff who did case management

- training was limited to job shadowing and informal on-the-job training

- no training manual or handbook on case management was available to staff

23. We also found that the department did not outline case management standards for staff or provide common tools and timelines for completing key case management tasks. For example, staff were required to prepare release plans, but the department did not set requirements for the minimum content that should be in the plans or when they should be completed.

24. The department had taken some actions related to case management. In October 2019, the department created a case management committee to standardize its approach to case management. At the end of our audit period, the committee had drafted new forms for collecting information on inmates’ social history and for assessing their needs. These new forms incorporated principles of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (that is, traditional Inuit knowledge and values). Standardized templates for case management plans and release plans were under development. The department was also developing a new information management system (SharePoint) that was expected to provide easier access to case management documents and help facilitate updates for readmissions, transfers, and releases into the community. The system was scheduled to be implemented in July 2021. The committee was also developing a case management manual that would be followed by a training manual and case management training.

25. Corrections officials noted that one of the challenges with providing case management services was a lack of clearly defined roles and responsibilities for ensuring that case management services were being provided. Toward the end of our audit, correctional supervisors assumed responsibility for ensuring that case management services were being provided. Department officials informed us that these new lines of authority would be incorporated into the new information management system and case management manual.

26. Recommendation. The Department of Justice should complete and implement case management standards and a case management manual and related guidance for staff. It should also make case management training mandatory for Corrections Division staff who do case management and ensure this training is provided to staff.

The department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Justice created a case management working group in October 2019 to review and standardize practices across all correctional facilities.

This work also includes a training manual that will be developed and used to train all staff, both existing and new. It is anticipated that this manual will be completed by March 2022. Training will take place following the completion of the manual.

Inmates did not have consistent access to rehabilitation programs or mental health services

27. We found that since our 2015 audit, there had been limited improvements to rehabilitation programs. For example, some programming had been updated in 2020. The Department of Justice had also introduced some new culturally relevant rehabilitation programming. However, we found that adult inmates still did not have consistent access to rehabilitation programs. We also found that the department had not assessed the needs of inmates nor developed an overall plan for delivering rehabilitation programs. We also found that there were gaps in inmates’ access to mental health services in secure custody facilities.

28. The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

- Inconsistent access to rehabilitation programs

- Numerous gaps in mental health services provided to inmates

29. This finding matters because rehabilitation programs and mental health services are intended to address the underlying factors that led inmates to be incarcerated, and to reduce their likelihood of reoffending. These programs and services can also improve overall inmate well-being and help prepare them for successful reintegration into the community after being released.

30. Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 40, 51, 52, and 105 to 106.

Inconsistent access to rehabilitation programs

31. In our 2015 audit, we found that inmates at the Baffin Correctional Centre and the Rankin Inlet Healing Facility did not have adequate access to rehabilitation programs. The Department of Justice had also not assessed inmate needs to inform its rehabilitation programming, nor did it have an overall plan to deliver rehabilitation programs. In this follow-up audit, we examined access to programming at all secure adult custody facilities and found limited improvements.

32. We found that adult male inmates did not always have access to key rehabilitation programs, such as anger management and substance abuse recovery. For example, at the Rankin Inlet facility, these programs were offered only twice a year. As a result, depending on when the inmates were at the facility, the programs may not have been available to them. Anger management and substance abuse recovery programs were being offered at the Baffin and Makigiarvik facilities, but there were program gaps. For example, the anger management program was not offered for 6 months in 2018. The content of the anger management program was updated in 2020. At these same facilities, a second addictions recovery program was also offered. We also found that none of the secure custody facilities for adult male inmates offered a sex offender rehabilitation program.

33. We found that access to education programs offered to male inmates was inconsistent across facilities. For example, literacy and pre-trades tutoring were provided at the Rankin Inlet and Makigiarvik facilities. However, inmates at the Baffin facility were not offered these programs. Similarly, at the Rankin Inlet facility, inmates were able to work on their high school credits through Nunavut Arctic College’s online adult high school program. However, this program was not offered at the other facilities.

34. We found that there were important gaps in the programs available at the Nunavut Women’s Correctional Centre. For example, an anger management program was not available and a substance abuse recovery program was offered for only a brief period. The facility also did not offer education programs, which meant that female inmates could not upgrade their academic skills or improve their opportunities for employment.

35. In 2015, we found that a range of cultural programs was offered to inmates at the Baffin and Rankin Inlet facilities. In this follow-up audit, we found that staff had introduced some new culturally relevant rehabilitation programming, such as the Pilimmaksarniq Education Program. Offered at the 4 secure custody facilities for adults, this program was developed for Nunavut’s inmates and focused on Inuit societal values, communication strategies, and relationship building. The Better Father, Better Husband Program offered at the Rankin Inlet facility was another example of culturally relevant rehabilitative programming offered by the department. We found that, because of a lack of capacity, the facilities were challenged when it came to offering these programs on an ongoing basis.

36. We found that rehabilitative programming at the 4 adult secure custody facilities was being delivered primarily in English and not in Inuktitut, the mother tongue of most inmates.

37. We also found that a variety of programs and services were offered at the Isumaqsunngittukkuvik Youth Facility.

38. In our 2015 audit, we recommended that the department identify the needs of its inmate population. This assessment would have helped it determine whether the programming it offered aligned with those needs and identified any gaps in programming. As part of this follow-up audit, we found that the department had not done this assessment.

39. The department still had no overall plan for delivering rehabilitation programs, nor did it have sufficient dedicated staff to plan and deliver these programs. As a result, it frequently relied on correctional case workers to deliver programs, and these workers could be called away to attend to their primary duties. We also observed that not all staff delivering programs had received training in the subject matter or on program facilitation and learning strategies. Further, the department did not have a dedicated budget for rehabilitation programming. Some enhancements to capacity were made in 2020. The department received approval for 2 new programming positions for the Aaqqigiarvik Correctional Healing Facility. At the Nunavut Women’s Correctional Centre, a new Deputy Warden Operations and Programs position was staffed to manage case management and programming.

40. Recommendation. The Department of Justice should provide the resources needed to plan and consistently deliver rehabilitation programming to inmates, and it should provide training to staff who deliver the programming.

The department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Justice will commit to developing a programming strategy for the Corrections Division.

The department is also looking to work with federal partners to build on successful rehabilitative programming that is already provided to some of the department’s federal and territorial clients under bilateral agreements.

The department plans to offer train-the-trainer training to staff who are facilitating or providing programming.

Numerous gaps in mental health services provided to inmates

41. In our 2015 audit, we found that the Baffin Correctional Centre and the Rankin Inlet Healing Facility had few staff members who could provide counselling or other support services to inmates. We also found that most adult inmates who were identified as needing mental health services did not receive them. In this follow-up audit, we found that capacity continued to be limited and that there continued to be gaps and inconsistencies in the level of mental health services being provided to inmates.

42. A significant proportion of inmates in Nunavut’s correctional facilities have mental health and addiction challenges. However, there are only 2 in-house mental health positions—1 to support inmates at the Baffin Correctional Centre and the Makigiarvik facility and 1 at the Isumaqsunngittukkuvik Youth Facility. Since 2016, the position supporting inmates at the Baffin and Makigiarvik facilities had been filled for less than a year. In 2020, the department hired a mental health nurse on a casual basis to support inmates at both the Baffin and Makigiarvik facilities. At the Rankin Inlet Healing Facility, there were 2 Inuit program counsellors/facilitators on staff. However, there were no dedicated mental health positions at the Rankin Inlet Healing Facility or the Nunavut Women’s Correctional Centre. We were informed that the individual supporting the youth facility also started to provide support to the women’s facility in 2020. There were no addiction support services at any of the facilities except for the youth facility.

43. In 2015, we recommended that the department review and increase its capacity, where required, to ensure that inmates needing mental health services had access to them. The department commissioned a preliminary review of mental health services, but it covered only the Baffin and Makigiarvik facilities. The review identified significant deficiencies in mental health services for inmates. We found that the department had not added any new dedicated mental health positions since 2006. In our view, such positions are necessary to provide inmates with ongoing treatment, counselling, and support to meet their mental health needs.

44. The Mental Health Strategy for Corrections in Canada: A Federal-Provincial-Territorial Partnership emphasizes the importance of early identification of mental health challenges for inmates when they arrive at a correctional facility. This should be done through

- an initial screening of suicide risk

- a broader mental health screening interview to identify issues beyond the risk of suicide

The directives of the department’s Corrections Division require an initial screening of suicide risk along with a security rating screening upon admission to determine where inmates should be housed within the facility.

45. We found that the initial screening upon admission for suicide risk and to assign a security rating was not always being done. Of the admission files we examined at the 5 secure custody facilities, the completion rate ranged from 55% to 80%.

46. We found that the broader mental health screening interviews were done when inmates entered the Baffin, Makigiarvik, youth, and women’s facilities. However, they were done at the Rankin Inlet facility only during 2019 and early 2020.

47. At the youth facility, a mental health and wellness clinician screened inmates for mental health challenges using a screening tool (a questionnaire) tailored to young people. At the other facilities, nurses did this broader mental health screening using a recognized screening tool. Neither tool had been tailored to Inuit inmates. In addition, the nurses were not given a manual nor did they receive any training on using the screening tool, which could have helped them identify inmates’ mental health challenges. We also found that the department had not established guidelines on how to conduct the broader screening and how the screening results should inform inmate case management and mental health supports.

48. Assessment and diagnosis of complex mental illnesses, when required, must be done by qualified psychiatrists or psychologists to allow for appropriate treatment. Because the department did not have a psychiatrist or psychologist on staff, it collaborated with Nunavut’s Department of Health to provide assessment services to adult inmates with complex needs in its Iqaluit facilities. From 2016 to February 2020, inmates in the Iqaluit facilities were assessed by a team of visiting psychiatrists provided through the Department of Health. The team came once a month to provide services to members of the community. The team also spent 4 hours seeing inmates from the Baffin, Makigiarvik, and women’s facilities.

49. Starting in March 2020, as a result of the coronavirus disease (COVID‑19)Definition 1 pandemic, the psychiatrists discontinued their visits to Iqaluit and changed to virtual e‑consults. However, because of resource constraints, the Department of Health made these e-consults available only to members of the community but not to inmates in Iqaluit. As a result, inmates in Iqaluit who required assessment and diagnosis of complex mental illnesses did not receive them. As of March 2021, these assessments were still not being done for inmates in custody in adult correctional facilities in Iqaluit. We found that the Department of Health coordinated with children’s hospitals in southern Canada to get assessments for youth inmates and that those assessments continued after March 2020.

50. We also found that no psychiatric assessments were available to inmates at the Rankin Inlet facility. This meant that inmates there with complex needs were not being assessed and diagnosed.

51. Recommendation. The Department of Justice should ensure that

- suicide and security risk screening of inmates is completed once they are admitted to a facility

- broader screening of all inmates takes place to identify those who have mental health or addiction challenges to inform inmate placement, programming, counselling, and other mental health supports

- inmates that require more detailed assessment and diagnosis of complex mental illnesses are provided with these assessments

The department’s response. Agreed. Suicide risk assessments and security screenings are a core part of what the Corrections Division does at every new intake.

Unfortunately, documentation, including centralized storage locations, has not been consistent. This provided challenges in tracking and substantiating the implementation of this work when working with the Office of the Auditor General of Canada throughout this process.

The Department of Justice is committed to tracking this information and will have better tools to do so once the ongoing work related to a custom SharePoint site and corrections database is completed.

52. Recommendation. The Department of Justice should provide counselling and other mental health supports to inmates with mental health and addiction challenges who are under its care and custody. These services should be provided by qualified mental health professionals.

The department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Justice has taken steps to hire a dedicated mental health nurse in Iqaluit, and the department will continue to look for more ways to enhance mental health supports currently being offered in line with this recommendation.

The Department of Justice will work with its colleagues at the Department of Health to identify and address gaps in mental health services for inmates.

The department’s management and oversight of administrative segregation was deficient

53. We found that since our 2015 audit, the Department of Justice adopted a new approach to segregation with the objective of keeping inmates in segregation for the shortest time possible. However, the department did not provide staff with formal procedures on how to place and monitor an inmate in administrative segregation nor did it have procedures for overseeing administrative segregation.

54. The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topic:

55. This finding matters because spending time in segregation can jeopardize an inmate’s mental and physical health. Having proper procedures, training, management, and oversight are important to ensure that segregation placements are justified and that inmates are managed safely and remain in segregation for the shortest time possible.

56. Segregation is the isolation of an individual from the general inmate population. “Disciplinary segregation” refers to isolating inmates as a means to discipline them. “Administrative segregation” is used to temporarily keep inmates out of the general population for their own protection, including to protect them from threats from other inmates or the risk of self-harm. Inmates may also be placed into administrative segregation because they are jeopardizing the security of the institution or the safety of other inmates or staff.

57. In July 2019, the department stopped using disciplinary segregation and, since then, has only used a revised, informal approach to administrative segregation. This revised approach involves engaging with and supporting inmates while they are in segregation and keeping them in segregation for the shortest time possible. The department has introduced mandatory training for its staff, including Nunavut Healing and Learning Together (NUHALT) and Mental Health First Aid. Both are meant to better equip staff when dealing with inmates in administrative segregation.

58. At the time of our audit, 4 facilities were using the revised approach to administrative segregation:

- Baffin Correctional Centre

- Rankin Inlet Healing Facility

- Nunavut Women’s Correctional Centre

- Isumaqsunngittukkuvik Youth Facility

Starting in March 2020, because of the COVID‑19 pandemic, segregation cells were used for isolating inmates upon their admission to a facility to adhere to territorial health and safety guidance. This meant cells may not have been available for segregation purposes.

59. Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 65 and 66.

Deficiencies in the management and oversight of administrative segregation

60. In our 2015 audit, we found that the department was not following all of the guidelines for placing and overseeing inmates in segregation. In this follow-up audit, we found that, although the department had modified its approach to segregation, there was no improvement in how segregation was being managed.

61. We found that the department did not have formal guidelines, procedures, or training for placing and overseeing inmates in administrative segregation. In June 2019, a new Corrections Act passed in the Legislative Assembly of Nunavut, but it was not yet in force at the end of our audit period. Department officials told us that once the act comes into force, regulations, directives, and standing orders will be developed to formalize the department’s revised approach to segregation.

62. In 2019, the department introduced a new form for staff to document the reasons an inmate was placed into administrative segregation. The form was used by all 4 facilities to document who authorized the segregation placement and the time the inmate entered segregation. The placement decision was to be reviewed after every 24 hours so that the inmate was not kept in segregation longer than needed.

63. We tested 36 administrative segregation placements (involving a total of 11 inmates) across the 4 facilities where administrative segregation was being used. We examined whether the new forms were complete, review dates were noted, and reviews were done as required. We also looked at how long inmates were in administrative segregation. We found the following:

- Only 13 of the 36 placements had an administrative segregation form on file. All 13 had the justification for the placement and a review date identified on the form. However, a review of the placement decision was documented for only 2 of the 13 placements.

- Of the 36 placements in administrative segregation, the majority were for less than 2 days. In particular, 17 (47%) were segregation placements for less than 1 day, while 10 (28%) were placements that were 1 day or more but less than 2 days. The remaining 9 placements were between 2 to 5 days in length.

64. The department had no process for overseeing that documentation requirements for administrative segregation were met, both for initial and ongoing placements. In response to our 2015 audit, the department indicated that it would create a compliance- and oversight-related position within the Corrections Division. The staff member in this position would help oversee segregation. We found that the department had not created this position (see paragraph 103). We also found that facility-level data on the use of administrative segregation was not compiled in 1 location and was not easily accessible, which limited the department’s ability to roll up the data and analyze segregation at the department level.

65. Recommendation. The Department of Justice should immediately establish and implement formal procedures for its revised approach to segregation. This should include procedures for monitoring and oversight, ensuring that required documentation is completed when an inmate is placed into administrative segregation and that regular reviews of the placement are completed and documented.

The department’s response. Agreed. The 2019 Nunavut Corrections Act has detailed and best-practice provisions for the use and oversight of administrative segregation. As the division works through standing orders and directives, the provisions of the new act are being used as the standard of operations.

The act also includes provisions around the monitoring and oversight by an independent investigation officer. The Department of Justice expects to bring this act into force within the year.

The department is currently working through the process of establishing an independent investigation office that will oversee this work.

66. Recommendation. The Department of Justice should ensure that information on the use of administrative segregation is centrally located and accessible to facilitate oversight and reporting on administrative segregation in the facilities where it is being used.

The department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Justice will work with facility managers to centralize and better manage administrative segregation information.

With the completion of the new case management manual and training, managers will receive consistent and effective direction and training on how to implement standards in information collection and storage.

While the department feels it has made strides in the reduction of administrative segregation, this segregation should be further limited once the department has the capacity to appropriately house and separate maximum-security clients from medium-security clients. This situation will improve with the opening of the Aaqqigiarvik Correctional Healing Facility.

The corrections standing orders and directives for those facilities that have the ability to administratively segregate clients will be updated in 2021 to ensure the act is being followed consistently in all facilities.

Operating correctional facilities

Progress was made in addressing a lack of capacity

67. The Department of Justice opened a new correctional facility in 2015. A second new facility is scheduled to open in September 2021. These facilities will address overcrowding and other capacity-related issues at the Baffin Correctional Centre that we raised in our 2015 audit. However, during this follow-up audit, we found that the Nunavut Women’s Correctional Centre faced challenges accommodating the number of inmates admitted to the facility. This resulted in female inmates with different security ratings being housed together because of a lack of capacity to house them separately.

68. The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topic:

69. This finding matters because without adequate capacity in facilities, inmates may not be housed according to their assigned security ratings, or overcrowding may occur, both of which can put staff and inmates at risk of harm. Overcrowding can present even more risk during emergencies and events, such as the COVID‑19 pandemic. Lack of space can also limit the type of rehabilitation programming and services available to inmates.

70. Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 78.

Increased capacity to house male inmates but a lack of capacity for female inmates

71. In our 2015 audit, we found that there was overcrowding at the Baffin Correctional Centre and that not all inmates were housed according to their assigned security ratings. The Baffin Correctional Centre was the only facility in Nunavut that held maximum-security adult male inmates, and its capacity to house these inmates was very limited. Programming space was also very limited at the facility. In this follow-up audit, we found that the department had made progress in addressing overcrowding at the Baffin facility by opening the Makigiarvik facility in 2015, a minimum-security facility that can hold 48 inmates.

72. Further progress is expected with the opening of the new Aaqqigiarvik Correctional Healing Facility in September 2021. This facility will have space for up to 54 medium-security inmates and 38 maximum-security inmates. The new facility will also have 15 cells for inmates with complex needs. Prior to the opening of this new facility, the department dealt with overcrowding at the Baffin Correctional Centre by transferring inmates to other jurisdictions.

73. In 2016, a needs analysis was conducted for the department that indicated that by 2029, the department would need a total of 250 beds to meet its needs for adult male inmates. With the construction of the new Aaqqigiarvik Correctional Healing Facility, the department will have the capacity to house 230 male inmates across its various adult male facilities, including halfway houses.

74. The Aaqqigiarvik Correctional Healing Facility includes space for programming. The Baffin Correctional Centre is scheduled to be renovated to provide programming space to supplement the programming space at the Aaqqigiarvik Correctional Healing Facility. In addition, we noted that the design of the facility was informed by an Elder’s committee and was designed to incorporate Inuit societal values.

75. We found that the physical capacity of the Nunavut Women’s Correctional Centre was insufficient given its security and programming needs. Although 4 beds had been added to the facility since it first opened, according to the department’s data, this facility often operated close to or at capacity and had no dedicated space for programming activities. In addition, all female inmates were housed together regardless of security rating, which can present security risks to staff and inmates.

76. The lack of capacity at the women’s facility presented additional challenges with placing inmates into administrative segregation. The facility had 2 segregation cells. Since March 2020, because of the COVID‑19 pandemic, 1 cell was also used to isolate new inmates admitted into the facility. When the cell was occupied, staff were unable to use it to segregate inmates.

77. We also found that, because of space limitations, inmates on remand were housed with those serving sentences in all secure facilities, which contravened the department’s directives.

78. Recommendation. The Department of Justice should review and adjust the use of existing facilities to optimize space and better respond to housing and programming needs for male and female inmates. This should include space for inmates on remand and those serving sentences.

The department’s response. Agreed. The Corrections Division has monitored the use of the current infrastructure capacity of the Department of Justice’s facilities and whether they are being utilized effectively. Various options are being considered, which would require, at minimum, significant renovations.

As part of this process, the department will engage internal partners to undertake a needs assessment and develop options that would facilitate the necessary growth in this area. Anticipated completion date for this work is fall 2021.

The department continued to face high staff-vacancy rates and could not determine whether its staff were provided with adequate training

79. Similar to our findings in 2015, we found in this follow-up audit that all facilities had high staff-vacancy rates for critical positions, and as a result, the Department of Justice continued to rely on overtime and casual staff to meet its staffing needs. We found that the department had assessed its staffing needs but had not determined an acceptable level of overtime or monitored its use. The department took steps to increase its training capacity. However, it did not adequately track staff training rates, which meant that we could not get an accurate picture of training completion rates across the department. Although we found no improvement in this area compared with our 2015 audit, the department was developing a new software system that would allow it to track staff training as well as manage and track overtime. We did find that since our 2015 audit, the department had increased mental health supports for staff.

80. The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

- High staff-vacancy rates and no human resources plan

- Gaps in information on staff training

- Increased mental health supports for staff

81. This finding matters because the department must pay a premium for overtime hours worked, and staff members may become burned out from working too many hours. In addition, frontline correctional case workers may be more prone to stress, burnout, and mental health issues, such as anxiety and depression. Having mental health supports for staff can improve their well-being and improve retention. Inadequate tracking of staff training means that the department cannot be sure that its staff members are qualified to carry out their duties.

82. Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 90 and 105 to 106.

High staff-vacancy rates and no human resources plan

83. In our 2015 audit, we found that the department relied heavily on overtime and casual staff to meet its staffing needs at the Baffin Correctional Centre and the Rankin Inlet Healing Facility. The department had also not adequately monitored or managed overtime use at these facilities. In this follow-up audit, we found that the department continued to rely on overtime and casual staffing to meet its staffing needs but that it was not adequately monitoring the use of overtime.

84. In this audit, we examined staffing across all facilities. We found that there were high staff-vacancy rates in critical positions (Exhibit 4). The overall vacancy rate for the department was 28% as of 31 March 2020. Between 2018 and 2020, floor-staff-related positions (such as correctional case workers and supervisors) had the highest average vacancy rate across all facilities. The department used acting positions, overtime hours, and casual staff to fill vacant positions.

Exhibit 4—Vacancy rates were high for critical positions from February 2018 to July 2020

| Position category | Average vacancy rate |

|---|---|

| Senior management (wardens) | 10% |

| Management (deputy wardens) | 24% |

| Floor staff supervisors | 35% |

| Floor staff support (for example, nurses) | 31% |

| Floor staff (correctional case workers and correctional officers) | 27% |

85. In 2016, the department analyzed its staffing needs, but since then, it has faced challenges in meeting these needs. Department officials identified several factors that affected their ability to attract and retain staff. These included

- long staffing processes

- competing staffing priorities

- lack of qualified candidates

- lack of staff housing

- difficult working conditions within correctional facilities (see paragraph 92)

86. We found that the department did not have a human resources plan to address its chronic staffing challenges. Such a plan would allow the department to outline the steps it must take to recruit, train, and retain staff.

87. Some of the recruitment and retention challenges the department faced—such as lack of staff housing and long staffing processes—were not fully within its control. Overcoming these challenges will require the department to partner with other organizations, such as Nunavut’s Department of Human Resources, which manages the staffing process for the department.

88. In early 2020, the department partnered with Algonquin College, located in Ottawa, Ontario, to announce a new program called the Community and Justice Services Diploma: Inuit Correctional Caseworkers. Although the program was delayed because of the COVID‑19 pandemic, it is an example of how the department can work with partners to address its recruitment challenges.

89. Similar to our 2015 audit, we found that overtime rates were high. For the 2015–16 to 2019–20 fiscal years, the department spent between $2 million and $3 million annually on overtime across all facilities. This represented about 7% of its total spending on salaries. In 2015, we recommended that the department determine an acceptable level of overtime and monitor its use. We found that this analysis and monitoring had not been done. In 2020, the department signed a contract for a new software system (InTime) that would allow it to manage and track staff scheduling and overtime. The system was under development as of 31 March 2021.

90. Recommendation. The Department of Justice should develop and implement a comprehensive human resources plan that outlines the steps it will take to recruit and retain Corrections Division staff for existing and future facilities. The plan should

- outline the staff that the department needs to properly operate its facilities and support inmates

- include steps that the department, working with its partners, will take to remove barriers that prevent timely hiring of permanent staff

The department’s response. Agreed. There are significant capacity issues through all government departments, which are especially felt within the Corrections Division.

With the use of various human resource tools available to the division, including the Nunavut Inuit Labour Force Analysis, the Department of Justice will work with the Department of Human Resources and the Department of Finance to develop a human resources plan for the division. Anticipated completion date for this work is fall 2022.

The department anticipates that the opening of the state-of-the-art Aaqqigiarvik Correctional Healing Facility will create a much improved working environment and will have a positive impact on recruitment and retention.

Gaps in information on staff training

91. We found that to increase its in-house training capacity, reduce training costs, and increase the availability of training, the department opened a dedicated training facility, created 2 new training officer positions, and filled 1 of these positions. These positions are in addition to the training coordinator position that was established in 2013. In our 2015 audit, we found that the department’s tracking of staff training at the Baffin Correctional Centre and the Rankin Inlet Healing Facility was incomplete. In this follow-up audit, we found that there were still gaps in how the department tracked staff training. Although the department had identified the mandatory training its staff needed, most of the information on training completion rates was disaggregated and housed in multiple locations. Department officials told us that not all staff had completed mandatory training. However, because of concerns about the quality of the training data the department provided us, we could not put together an accurate picture of training completion rates in the department. The InTime system that the department was implementing to manage and track staff scheduling and overtime was also planned to be used to track staff training.

Increased mental health supports for staff

92. In the department’s most recent survey of Corrections Division staff (2016), over half of respondents (53%) said they thought that general stress associated with their job contributed to staff turnover and retention issues. Correctional case workers witness incidents in which inmates have attempted suicide or harmed themselves or others, and these case workers may experience risks to their own personal safety. Regular exposure to trauma can lead to anxiety and depression and may make frontline correctional staff more prone to mental health issues.

93. We found that to help improve staff retention and well-being, the department increased mental health services for staff. In mid-2020, it signed a contract with an external service provider to provide mental health services to staff. As of July 2020, the service provider offered debriefs after traumatic incidents and one-on-one counselling on demand to staff. This new counselling service was in addition to the counselling that was available through the government’s Employee and Family Assistance Program.

The department was unable to demonstrate that it was protecting the safety and security of inmates and staff

94. In our 2015 audit, we found deficiencies in cell searches, fire drills and evacuations, and fire inspections at the Baffin Correctional Centre and the Rankin Inlet Healing Facility. In this follow-up audit, we found some improvement in these areas. For example, the Baffin Correctional Centre—along with the Makigiarvik and Uttaqivik facilities—held fire drills and evacuations as required. However, overall, we found that the Department of Justice was not complying with its directives for cell search frequency and fire drills and evacuations, or for documenting how it addressed any deficiencies that were found. We also found that the department did not monitor its compliance with the directives that specify how it should perform these activities.

95. The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topic:

96. This finding matters because without proper compliance with directives for cell searches, fire drills and evacuations, and fire inspections, the safety and security of inmates and staff is at risk. In March 2021, a fire occurred at the Baffin Correctional Centre. Such an event underlines the importance of conducting and documenting fire drills and inspections.

97. Cell searches are done to ensure that inmates are not storing in their cells contraband goods, such as knives or drugs, which can pose a security risk to staff and inmates. Cell searches, along with fire drills and evacuations, are supposed to be done according to a specific frequency, which is set out in the Corrections Division Directives or the facility’s standing orders.

98. Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 104 to 106.

Lack of compliance with directives for cell searches, fire drills and evacuations, and fire inspections

99. In our 2015 audit, we found deficiencies in cell searches, fire drills and evacuations, and fire inspections at the Baffin Correctional Centre and the Rankin Inlet Healing Facility. In this follow-up audit, we examined these issues at all facilities and found

- the department lacked clear roles, responsibilities, and guidance for responding to deficiencies identified in fire inspection reports

- with the exception of the Uttaqivik Community Residential Centre, staff were not conducting cell searches at the frequency set out in the department’s directives

- there was no formal monitoring process to ensure that cell searches were conducted according to the frequency requirements set out in the department’s directives

100. We also found that the results of cell searches were not documented consistently. This made it difficult to analyze trends related to the types of contraband that was found during cell searches and how it had entered the facility.

101. In this follow-up audit, we asked the 7 correctional facilities to provide us with documentation (for example, fire drill reports) to demonstrate that they had conducted fire drills and evacuations regularly as required (4 times a year) during 2018, 2019, 2020, and the period from 1 January to 31 March 2021.

102. At 3 of the 7 facilities (the Baffin, Makigiarvik, and Uttaqivik facilities), the fire drills and evacuations were done consistently (quarterly) in accordance with directives. At the youth facility, they were done as required with the exception of 1 drill missed in each of 2018 and 2019. At the other 3 facilities, fire drills and evacuations were held sporadically, and we were concerned to find that there were significant periods of time during which fire drills and evacuations were not conducted at all. The Nunavut Women’s Correctional Centre did however provide fire drill reports for each quarter in the 2020–21 fiscal year. We also asked for annual fire inspection reports for each facility from 2016 to 2020. We received 12 of the 35 expected inspection reports for that time period. The lack of fire inspection documentation meant that the department did not have assurance that fire inspections were done on an annual basis or that corrective actions were taken to promptly address identified deficiencies. Failure to take corrective action could pose a safety risk for inmates and staff.

103. In response to our 2015 audit, the department indicated that it would create a compliance- and oversight-related position within the Corrections Division, pending staffing analysis and funding approval. The staff member in this position would help monitor compliance with policies and procedures and conduct investigations when required. In our follow-up audit, we found that the department had not created this position. Officials informed us that the SharePoint information system being developed to document case management services is also expected to serve as a central repository for fire safety information, such as fire drills and evacuations and fire inspections. Having this type of information will be important for monitoring compliance with policies and procedures.

104. Recommendation. The Department of Justice should ensure that the results of cell searches and fire drills and evacuations are documented, and that corrective actions are taken. It should also ensure that roles and responsibilities for responding to the results of annual fire inspections are clearly defined, and that actions taken in response to these inspections are documented.

The department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Justice will work with facilities to better train managers on how to track fire drills and cell searches. This is a functionality the department has identified to be built into the custom SharePoint site currently being developed.

In addition, the department will put in place a mechanism to ensure there is appropriate follow-up on deficiencies identified through these exercises.

The way forward

105. We conducted this follow-up audit to assess the progress made by the Department of Justice in addressing deficiencies in delivering correctional services that we identified in our 2015 audit. We found that many of the issues we identified in our 2015 audit remained unresolved. The lack of progress on these issues is concerning because the matters that we raised have a direct impact on the rehabilitation of inmates and the health and safety of inmates and staff. In addition to the new recommendations included in this follow-up audit, the department should take immediate action on the following 2015 recommendations that had not been addressed:

- recommendations on case management (at paragraphs 120 and 124 of the 2015 report)

- recommendation on rehabilitative programming (at paragraph 137 of the 2015 report)

- recommendation on monitoring and managing use of overtime (at paragraph 100 of the 2015 report)

- recommendation on staff training (at paragraph 102 of the 2015 report)

- recommendations on protecting the safety and security of staff and inmates (at paragraphs 58, 59, 66, and 87 of the 2015 report)

The full text of these 2015 recommendations is reproduced in the Appendix to this report, along with the department’s 2021 responses.

106. The department should specify the actions it will take and timelines for addressing both new and outstanding recommendations. The actions should clarify where support is needed from other departments and how the department will collaborate with these departments to achieve progress. To strengthen accountability, regular periodic reports on the Corrections Division’s progress in implementing the recommendations from this follow-up audit and those still outstanding from 2015 should be prepared for the Director of Corrections and the Deputy Minister of Justice.

Conclusion

107. We concluded that the Department of Justice did not make satisfactory progress on selected observations and recommendations from our 2015 audit. We found that most of the issues facing the department in terms of supporting inmate rehabilitation and operating its correctional facilities remained unresolved. Addressing these issues will be important for the department to be able to achieve a corrections system that incorporates culturally relevant programming and rehabilitation measures that promote healing and successful reintegration of inmates into society and for ensuring the safety and security of staff and inmates.

COVID‑19

108. The COVID‑19 pandemic affected the operations of correctional facilities in the territory and caused challenges in managing human resources. For example, some staff were in self-isolation at the beginning of the pandemic, and non-essential staff were required to work from home for a temporary period. Staffing slowed as a result of the travel restrictions in place in the territory, and training for staff was paused. The pandemic further exacerbated issues in the delivery of programming and supports to inmates.

109. Following the start of the pandemic, the Department of Justice put in place a pandemic response plan. According to the department, health and safety measures were also implemented to protect staff, inmates, and the community at the outset of the pandemic. These measures included suspending all outside visitation and non-essential traffic, isolating new inmates for a period of 14 days, providing personal protective equipment to staff, and developing new cleaning protocols for its facilities. Starting in January 2021, visitors were allowed in facilities but were required to undergo screening and wear a mask.

110. In mid-April 2021, a case of COVID‑19 was reported in Iqaluit. Cases of COVID‑19 were subsequently detected at 1 facility in Iqaluit (plus 1 case detected at intake), with 14 inmates testing positive. Once the first case of COVID‑19 was detected in Iqaluit, the department restricted access to its facilities to staff and inmates only. After cases were detected at the facility in Iqaluit, inmates and staff were tested and contact tracing was undertaken. As of May 31, all of the inmates who had contracted COVID‑19 were assessed as having recovered.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on correctional services in Nunavut. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist the Legislative Assembly of Nunavut in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs, and to conclude on whether correctional services complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements, set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada applies the Canadian Standard on Quality Control 1 and, accordingly, maintains a comprehensive system of quality control, including documented policies and procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether the Department of Justice had made satisfactory progress on selected recommendations made in the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s 2015 audit report on corrections in Nunavut.

Scope and approach

This follow-up audit examined whether the Department of Justice made satisfactory progress in response to selected recommendations that were made in the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s 2015 audit report on corrections in Nunavut and that related to operating the Baffin Correctional Centre and the Rankin Inlet Healing Facility and managing inmate rehabilitation at these 2 facilities plus the Uttaqivik Community Residential Centre. This follow-up audit expanded on the scope of the 2015 audit by examining mental health supports provided to Corrections Division staff. It also examined activities across all correctional facilities in Nunavut. Text has been added to each findings section throughout this report to indicate facility coverage in 2015 versus facility coverage as part of this follow-up audit.

Audit work consisted of interviews with Corrections Division management and staff, and a review and analysis of data and documentation provided by the department. We selected a purposeful sample of inmate files to examine the Corrections Division’s delivery of case management services, initial screening of inmates’ suicide and security risks upon admission, and the management of segregation. Our file testing covered the period from 1 January 2018 to 31 March 2020 with the exception of inmates in segregation (which covered the period from 1 July 2019 to 30 November 2020 to cover the department’s new approach to segregation). Our examination of fire drills and evacuations covered the period from 1 January 2018 to 31 March 2021, while fire inspection reports were requested for the calendar years from 2016 to 2020. Examination work for the audit was carried out remotely as a result of the COVID‑19 pandemic. Prior to the pandemic, members of the audit team undertook a tour of the Baffin Correctional Centre, the Makigiarvik facility, and the Aaqqigiarvik Correctional Healing Facility, which was under construction in Iqaluit. Information was added to the report to indicate how the Department of Justice responded to the pandemic.

In June 2019, a new Corrections Act passed in the Legislative Assembly of Nunavut. The act was not in force at the time of the audit and was not within the scope of our audit. The audit also did not examine the capital planning or construction of the new Aaqqigiarvik Correctional Healing Facility.

This audit contributed to Canada’s actions in relation to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 16, which is, “Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels,” and Target 16.6, “Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels.”

Criteria

We used the following criteria to determine whether the Department of Justice had made satisfactory progress on selected recommendations made in the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s 2015 audit report on corrections in Nunavut:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

The Department of Justice has put measures in place and made progress related to

|

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period from 1 January 2018 to 31 March 2021. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 11 June 2021, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

Principal: Jim McKenzie

Director: Sami Hannoush

Catharine Johannson

Kamila Karolinczak

Sophia Khan

Adrienne Scott

Faraz Tariq

List of Recommendations

The following table lists the recommendations and responses found in this report. The paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report, and the numbers in parentheses indicate the location of the related discussion.

Managing inmate rehabilitation

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

26. The Department of Justice should complete and implement case management standards and a case management manual and related guidance for staff. It should also make case management training mandatory for Corrections Division staff who do case management and ensure this training is provided to staff. (19 to 25) |

The department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Justice created a case management working group in October 2019 to review and standardize practices across all correctional facilities. This work also includes a training manual that will be developed and used to train all staff, both existing and new. It is anticipated that this manual will be completed by March 2022. Training will take place following the completion of the manual. |

|

40. The Department of Justice should provide the resources needed to plan and consistently deliver rehabilitation programming to inmates, and it should provide training to staff who deliver the programming. (31 to 39) |

The department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Justice will commit to developing a programming strategy for the Corrections Division. The department is also looking to work with federal partners to build on successful rehabilitative programming that is already provided to some of the department’s federal and territorial clients under bilateral agreements. The department plans to offer train-the-trainer training to staff who are facilitating or providing programming. |

|

51. The Department of Justice should ensure that

(41 to 50) |

The department’s response. Agreed. Suicide risk assessments and security screenings are a core part of what the Corrections Division does at every new intake. Unfortunately, documentation, including centralized storage locations, has not been consistent. This provided challenges in tracking and substantiating the implementation of this work when working with the Office of the Auditor General of Canada throughout this process. The Department of Justice is committed to tracking this information and will have better tools to do so once the ongoing work related to a custom SharePoint site and corrections database is completed. |

|

52. The Department of Justice should provide counselling and other mental health supports to inmates with mental health and addiction challenges who are under its care and custody. These services should be provided by qualified mental health professionals. (41 to 50) |

The department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Justice has taken steps to hire a dedicated mental health nurse in Iqaluit, and the department will continue to look for more ways to enhance mental health supports currently being offered in line with this recommendation. The Department of Justice will work with its colleagues at the Department of Health to identify and address gaps in mental health services for inmates. |

|

65. The Department of Justice should immediately establish and implement formal procedures for its revised approach to segregation. This should include procedures for monitoring and oversight, ensuring that required documentation is completed when an inmate is placed into administrative segregation and that regular reviews of the placement are completed and documented. (60 to 64) |

The department’s response. Agreed. The 2019 Nunavut Corrections Act has detailed and best-practice provisions for the use and oversight of administrative segregation. As the division works through standing orders and directives, the provisions of the new act are being used as the standard of operations. The act also includes provisions around the monitoring and oversight by an independent investigation officer. The Department of Justice expects to bring this act into force within the year. The department is currently working through the process of establishing an independent investigation office that will oversee this work. |

|

66. The Department of Justice should ensure that information on the use of administrative segregation is centrally located and accessible to facilitate oversight and reporting on administrative segregation in the facilities where it is being used. (60 to 64) |

The department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Justice will work with facility managers to centralize and better manage administrative segregation information. With the completion of the new case management manual and training, managers will receive consistent and effective direction and training on how to implement standards in information collection and storage. While the department feels it has made strides in the reduction of administrative segregation, this segregation should be further limited once the department has the capacity to appropriately house and separate maximum-security clients from medium-security clients. This situation will improve with the opening of the Aaqqigiarvik Correctional Healing Facility. The corrections standing orders and directives for those facilities that have the ability to administratively segregate clients will be updated in 2021 to ensure the act is being followed consistently in all facilities. |

Operating correctional facilities

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

78. The Department of Justice should review and adjust the use of existing facilities to optimize space and better respond to housing and programming needs for male and female inmates. This should include space for inmates on remand and those serving sentences. (71 to 77) |

The department’s response. Agreed. The Corrections Division has monitored the use of the current infrastructure capacity of the Department of Justice’s facilities and whether they are being utilized effectively. Various options are being considered, which would require, at minimum, significant renovations. As part of this process, the department will engage internal partners to undertake a needs assessment and develop options that would facilitate the necessary growth in this area. Anticipated completion date for this work is fall 2021. |

|

90. The Department of Justice should develop and implement a comprehensive human resources plan that outlines the steps it will take to recruit and retain Corrections Division staff for existing and future facilities. The plan should

(83 to 89) |

The department’s response. Agreed. There are significant capacity issues through all government departments, which are especially felt within the Corrections Division. With the use of various human resource tools available to the division, including the Nunavut Inuit Labour Force Analysis, the Department of Justice will work with the Department of Human Resources and the Department of Finance to develop a human resources plan for the division. Anticipated completion date for this work is fall 2022. The department anticipates that the opening of the state-of-the-art Aaqqigiarvik Correctional Healing Facility will create a much improved working environment and will have a positive impact on recruitment and retention. |

|

104. The Department of Justice should ensure that the results of cell searches and fire drills and evacuations are documented, and that corrective actions are taken. It should also ensure that roles and responsibilities for responding to the results of annual fire inspections are clearly defined, and that actions taken in response to these inspections are documented. (99 to 103) |

The department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Justice will work with facilities to better train managers on how to track fire drills and cell searches. This is a functionality the department has identified to be built into the custom SharePoint site currently being developed. In addition, the department will put in place a mechanism to ensure there is appropriate follow-up on deficiencies identified through these exercises. |

Appendix—List of Recommendations Outstanding From 2015

The following table lists the recommendations outstanding from the 2015 March Report of the Auditor General of Canada, Corrections in Nunavut—Department of Justice that had not been addressed by the department. The table also includes the department’s 2021 responses to these recommendations. The paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the 2015 audit report. Where appropriate, the wording of some recommendations was adjusted to include all facilities.

Case management

| Outstanding recommendation from 2015 | Updated 2021 response |

|---|---|

|

120. The Department of Justice should complete assessments as soon as possible after admission to identify the programs and services required for each inmate’s rehabilitation. |