2014 Fall Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development Chapter 1—Mitigating Climate Change

2014 Fall Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development

Chapter 1—Mitigating Climate Change

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Observations and Recommendations

- Working to reduce emissions

- Regulations to reduce emissions have been delayed and good practices have not been consistently followed

- Departments are not yet assessing the success of current regulatory measures

- Environment Canada is not coordinating with the provinces and territories to achieve the national target

- Environment Canada still does not have a planning process for how the federal government will contribute to achieving the national target

- Estimating Canada’s future emissions

- Managing Canada’s fast-start financing

- Working to reduce emissions

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- Appendix—List of recommendations

- Exhibits:

- 1.1—Climate change is affecting all regions of Canada

- 1.2—The federal government has made domestic and international commitments to address climate change and reduce greenhouse gas emissions

- 1.3—Regulatory progress has been limited since 2012 and some measures have been delayed

- 1.4—Transportation is a significant source of greenhouse gas emissions

- 1.5—Current federal measures will have little effect on emissions by 2020

- 1.6—The provinces and territories have set a mix of reduction targets

- 1.7—Estimating emissions from forests poses challenges

- 1.8—Environment Canada's emission reports could include additional information relevant to decision makers

- 1.9—By 30 May 2014, most fast-start financing funds had not yet reached the projects to be funded

Performance audit reports

This report presents the results of a performance audit conducted by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada under the authority of the Auditor General Act.

A performance audit is an independent, objective, and systematic assessment of how well government is managing its activities, responsibilities, and resources. Audit topics are selected based on their significance. While the Office may comment on policy implementation in a performance audit, it does not comment on the merits of a policy.

Performance audits are planned, performed, and reported in accordance with professional auditing standards and Office policies. They are conducted by qualified auditors who

- establish audit objectives and criteria for the assessment of performance;

- gather the evidence necessary to assess performance against the criteria;

- report both positive and negative findings;

- conclude against the established audit objectives; and

- make recommendations for improvement when there are significant differences between criteria and assessed performance.

Performance audits contribute to a public service that is ethical and effective and a government that is accountable to Parliament and Canadians.

Introduction

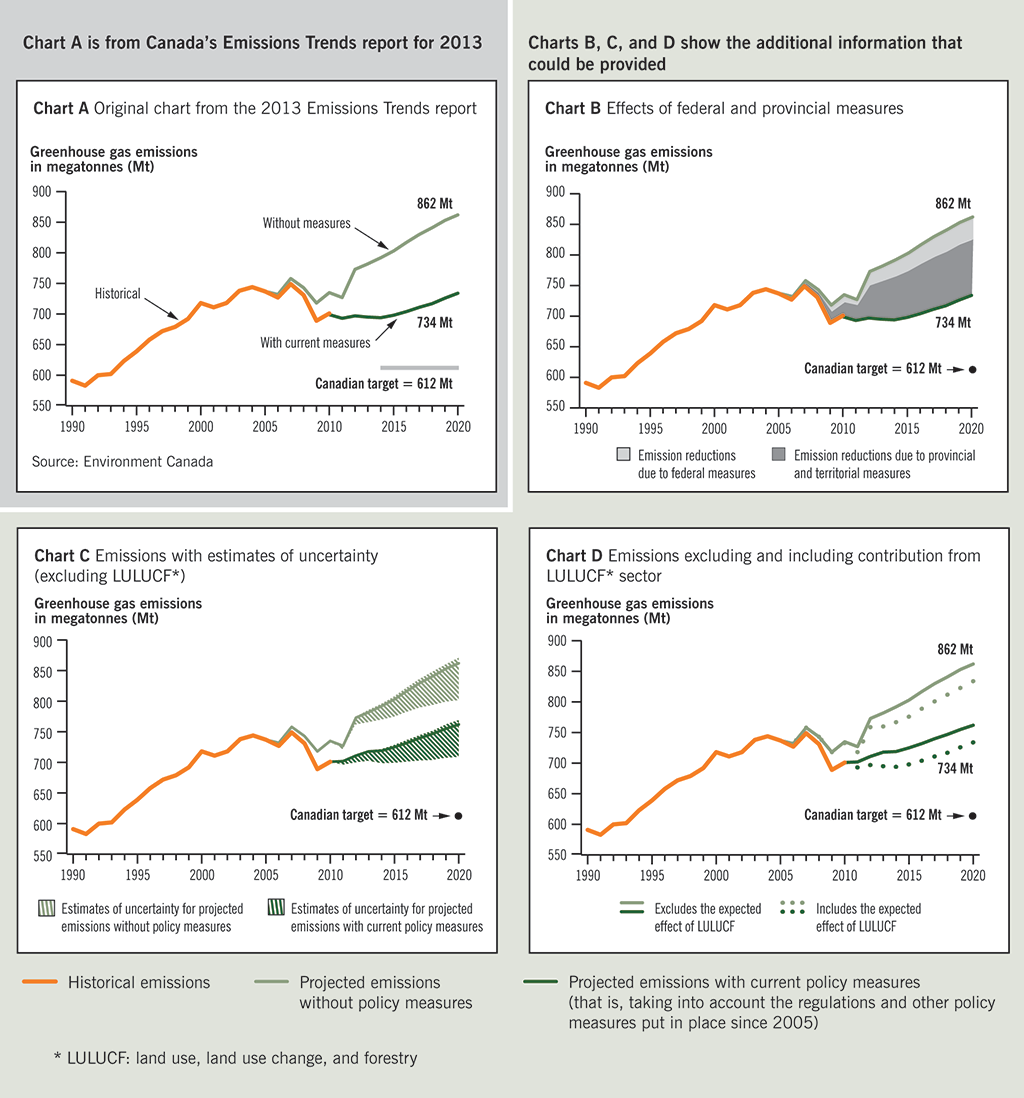

1.1 Scientists have documented the effects of climate change in all regions of our planet. For example, the Earth’s atmosphere is warming, sea levels are rising, the oceans are becoming warmer and more acidic, the Arctic ice cap is shrinking, and some weather extremes are becoming more frequent. In Canada, the effects include the loss of glaciers and the resulting impacts on water supplies on the Prairies, changes to water levels in the Great Lakes–St. Lawrence watershed, increasing risks from coastal storms, and more frequent heat waves (Exhibit 1.1).

Exhibit 1.1—Climate change is affecting all regions of Canada

Source: Government of Canada, Canada in a Changing Climate: Sector Perspectives on Impacts and Adaptation, 2014.

1.2 According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, these changes are attributable to human activities that result in emissions of greenhouse gases. Efforts to coordinate international action on greenhouse gases began in 1992 with the adoption of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Despite these efforts, emissions have risen and are projected to rise further.

Measuring greenhouse gases

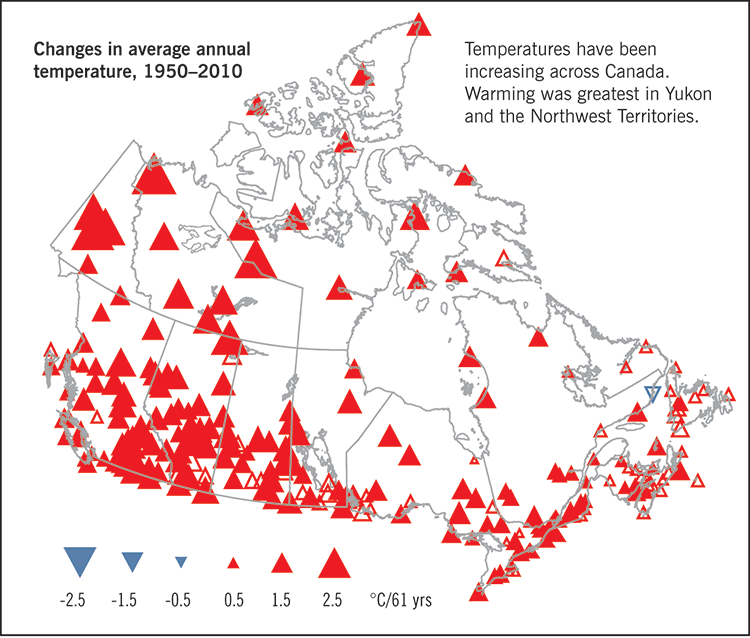

Because different greenhouse gases have different effects on the atmosphere, for measurement purposes emissions are usually converted to the equivalent in carbon dioxide, the most common greenhouse gas. Emissions are usually measured in megatonnes; that is, millions of tonnes.

1.3 The Government of Canada has recognized the need to urgently combat climate change and has made commitments and allocated funds to reduce emissions. Under the Copenhagen Accord, an international agreement reached in 2009, the federal government committed to a 17-percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions below 2005 levels by the year 2020 for Canada’s economy as a whole. This was the latest in a series of international commitments made by Canada to reduce emissions (Exhibit 1.2); the federal government has since reiterated this commitment several times, including in its Sustainable Development Strategy. Under the Accord, the government also pledged to provide $1.2 billion over three years (2010 to 2012) to help developing countries address climate change, through an initiative called fast-start financing. Further, Canada has undertaken to achieve long-term reductions in emissions beyond 2020 through the Accord and other international statements.

Exhibit 1.2—The federal government has made domestic and international commitments to address climate change and reduce greenhouse gas emissions

The following timeline lists some of the federal government’s international and domestic commitments on climate change. For more details, see the 2012 Spring Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Chapter 2—Meeting Canada’s 2020 Climate Change Commitments.

Roles of federal departments

1.4 Within the federal government, Environment Canada is the lead department on the issue of climate change. It has primary responsibility for the current federal approach, which involves putting in place emission reduction regulations for each of the main sectors of Canada’s economy. The federal government has declared greenhouse gases to be toxic substances under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999, which establishes the regulatory framework for the control of such substances. Environment Canada’s other climate change responsibilities include reporting on current greenhouse gas emissions, estimating future emissions, leading international negotiations, and leading policy coordination for the provision of financial support to other countries, notably through the fast-start financing initiative. Environment Canada also has the lead on behalf of the federal government for the coordination of action on climate change with provincial and territorial officials.

1.5 Among other roles, Natural Resources Canada is responsible for estimating emissions from Canada’s forests, and also regulates energy efficiency under the Energy Efficiency Act. Transport Canada regulates emissions from ships pursuant to the Canada Shipping Act, 2001 and leads Canadian representation at international negotiations to reduce emissions from marine and aviation transportation modes. For the fast-start financing initiative, the Department of Finance Canada and the Canadian International Development Agency (now part of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada) have managed some of the large disbursements.

Past audit work

1.6 Over the last 16 years, our Office has examined different aspects of the federal government’s management of climate change, most recently in 2012. The present audit follows up on the 2012 Spring Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Chapter 2—Meeting Canada’s 2020 Climate Change Commitments. In the 2013 Spring Report of the Auditor General, Chapter 4—Official Development Assistance through Multilateral Organizations, we also examined one part of the fast-start financing initiative.

Focus of the audit

1.7 Our audit had three objectives. The first was to determine whether Environment Canada, working with others, has made satisfactory progress in addressing four key issues from our 2012 audit. We wanted to know whether

- the federal government has put in place emission reduction measures, following good practices for regulatory development;

- the federal measures currently in place have been assessed in terms of their success;

- Environment Canada has mechanisms for working with the provinces and territories to reduce emissions; and

- the Department has an implementation plan that describes how federal departments and agencies will contribute to achieving Canada’s emission reduction target.

1.8 The second objective was to determine whether Environment Canada, working with others, has used sound methods for estimating and reporting Canada’s future greenhouse gas emissions.

1.9 The third objective was to determine whether Environment Canada, working with others, is tracking, assessing, and reporting on funding under Canada’s fast-start financing initiative and the results achieved, including reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.

1.10 The audit focused on the actions of three federal entities: Environment Canada, Natural Resources Canada, and Transport Canada. We also spoke with other federal organizations to obtain their perspectives. We did not audit the actions of provincial or territorial governments. We also did not audit the multilateral banks, other multilateral organizations, or other governments that helped distribute the funds under the fast-start financing initiative.

1.11 The audit covered the period between January 2011 and July 2014. More details about the audit objectives, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this chapter.

Observations and Recommendations

Working to reduce emissions

1.12 In the 2012 Spring Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Chapter 2—Meeting Canada’s 2020 Climate Change Commitments, we noted several deficiencies. Based on these, we selected four areas for examination in this present follow-up audit:

- putting measures in place to reduce greenhouse gas emissions,

- assessing the success of the measures,

- working with the provinces and territories, and

- developing plans to achieve the 2020 Copenhagen Accord target of a 17-percent reduction in emissions below 2005 levels for Canada’s economy as a whole.

1.13 Overall, we found that federal departments have made unsatisfactory progress in each of the four areas examined. Despite some advances since our 2012 audit, timelines for putting measures in place to reduce greenhouse gas emissions have not been met and departments are not yet able to assess whether measures in place are reducing emissions as expected. We also found that Environment Canada lacks an approach for coordinating actions with the provinces and territories to achieve the national target, and an effective planning process for how the federal government will contribute to achieving the Copenhagen target. In 2012, we concluded that the federal regulatory approach was unlikely to lead to emission reductions sufficient to meet the 2020 Copenhagen target. Two years later, the evidence is stronger that the growth in emissions will not be reversed in time and that the target will be missed.

Regulations to reduce emissions have been delayed and good practices have not been consistently followed

1.14 In 2012, we found that regulations for renewable fuels and for passenger automobiles and light trucks had been finalized, and that coal-fired electricity regulations had been proposed. Some other regulations were in the conceptual stage or in development.

1.15 In this audit, we found that some progress has been made since 2012 by moving certain regulations forward and developing new ones. However, when we examined progress in each sector, we observed that timelines for putting several regulations in place have been delayed beyond the dates planned in 2012 (Exhibit 1.3). No federal regulatory action has been taken in some sectors, such as agriculture and waste. Although other levels of government are taking action in some of these areas, we did not audit their actions.

Exhibit 1.3—Regulatory progress has been limited since 2012 and some measures have been delayed

| Sector | Measure | Status | Timeline | Expected reductions in 2020 (megatonnes per year) | Changes since 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Transportation |

Renewable Fuels Regulations |

Finalized |

Came into effect in December 2010. Amended in November 2013. |

2 |

Regulations amended to include two exemptions. |

|

Passenger Automobile and Light Truck Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations |

Finalized for 2011–16 models Proposed for 2017–25 models |

Came into effect in September 2010. |

10 for 2011–16 models 3 for 2017–25 models (estimate) |

Progressed. Proposed regulations for 2017–25 models released in November 2012, but not published as of July 2014. |

|

|

Heavy-duty Vehicle and Engine Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations |

Finalized for 2014 and later models |

Published in March 2013. Came into effect in January 2014. Work for post-2018 model years is under way. |

3 |

Progressed. Regulations were in a conceptual stage in 2012. |

|

|

Energy efficiency standards for ships |

Finalized (new ships travelling internationally) |

Published in May 2013. |

0.4 |

Delayed. Regulations were expected to be published in August 2012 but were delayed until May 2013. |

|

|

Conceptual stage (new domestic ships) |

Under consideration. |

n/a |

n/a |

||

|

Conceptual stage (existing ships) |

Under negotiation at International Maritime Organization. |

n/a |

n/a |

||

|

Electricity |

Reduction of Carbon Dioxide Emissions from Coal-Fired Electricity Generation Regulations |

Finalized |

Published in September 2012. |

3 |

Emission reduction from final regulations is expected to be lower than that under the proposed 2011 regulations (was 5.3 megatonnes). |

|

Natural gas-fired electricity regulations |

Conceptual stage |

Discussions with stakeholders are under way. |

n/a |

Delayed. Publication of proposed regulations was expected in September 2012. |

|

|

Oil and gas |

Oil and gas regulations |

Conceptual stage |

Analysis is under way. Consultations continue. |

n/a |

Delayed. Proposed regulations were expected in December 2012. |

|

Emission-intensive trade-exposed industries |

Groups of industries will be regulated individually. |

Conceptual stage |

Discussions with stakeholders are under way. |

n/a |

Delayed. Publication of proposed regulations for one or more sectors was expected in late 2012. |

Sources: Environment Canada, Canada Gazette, and Canada’s Sixth National Communication on Climate Change and First Biennial Report to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

1.16 Transportation regulations. The transportation sector is one of the biggest sources of greenhouse gases (Exhibit 1.4). Progress has been made on most transportation regulations; for example, regulations for heavy-duty vehicles came into effect in early 2014. In their content and timing, Canada’s transportation regulations continue to be closely modelled on regulations in the United States, partly because of the highly integrated automotive market. For example, the technical specifications in Canadian regulations for passenger vehicles and light trucks match US specifications very closely. Environment Canada officials expect this parallel regulatory action to continue.

Exhibit 1.4—Transportation is a significant source of greenhouse gas emissions

The average vehicle on Canada’s roads produces about 5.6 tonnes of greenhouse gases per year. Overall, Canada produced an estimated 699 megatonnes of greenhouse gas emissions in 2012, with about 195 megatonnes from transportation. Reducing emissions by a single megatonne would be equivalent to removing 180,000 vehicles from the road.

Photo: Aaron Kohr/Shutterstock.com

1.17 Transport Canada is addressing emissions from other modes of transportation through voluntary measures, such as a Canadian aviation action plan. In addition, it is participating in international negotiations to address emissions from aviation (through its membership in the International Civil Aviation Organization) and shipping (through its membership in the International Maritime Organization). It is not clear whether or when these measures will lead to emission reductions. Transport Canada is now also addressing emissions from railways through voluntary measures rather than regulations, as previously planned.

1.18 Electricity regulations. Regulations for coal-fired power plants are now in place, but have not yet reduced emissions because the performance standards take effect only in July 2015 and only apply to new plants or to existing plants when they reach the end of their useful life. The final regulations will reduce emissions in the year 2020 by about half as much as originally planned in 2011; this is because the final performance standard is less stringent and existing power plants are assumed to have longer lifespans. The regulations will have a greater effect on emissions after 2020 as existing coal-fired plants come to the end of their life. The complementary regulations for natural gas-fired plants are now under discussion, but Environment Canada officials do not expect them to come into effect until 2016 at the earliest.

1.19 Oil and gas regulations. According to Environment Canada, the oil and gas sector will contribute 200 megatonnes to national emissions in 2020. This is 27 megatonnes more than in 2012—a larger increase than any other sector. Despite this prediction, regulations for the sector have been repeatedly delayed. Although detailed regulatory proposals have been available internally for over a year, the federal government has consulted on them only privately, mainly using a small working group of one province and selected industry representatives. In our view, this approach and the delays inhibit effective planning by affected parties, including industries and the provinces.

1.20 Environment Canada officials told us that one factor contributing to the delays has been concern about whether regulations would make Canadian companies in the sector less able to compete with their US counterparts. It is not yet clear what alignment between the Canadian federal government and the United States might mean in practice for these regulations, or when it might occur.

1.21 Overall effect of regulations. New regulations are being put in place slowly relative to the 2020 target, and the federal government has yet to act in sectors other than transportation and electricity. In addition, some measures now being considered by the federal government may have little effect on emissions by 2020 because of the limited expected reductions or because of the long lead times required to make capital investments or to change technologies.

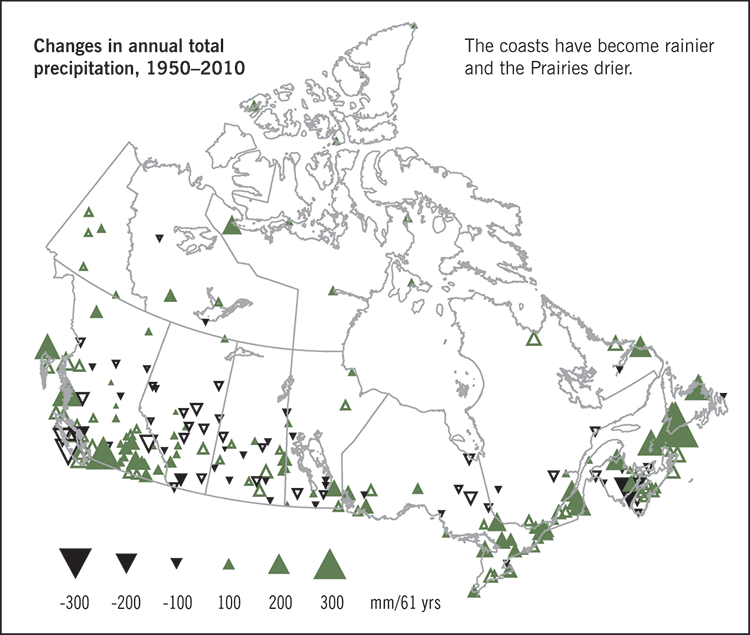

1.22 According to Environment Canada’s estimates, sector-specific federal regulations currently in place will reduce emissions by about 18 megatonnes in the year 2020. These measures are expected to achieve a reduction of about 7 percent in the gap between Canada’s Copenhagen target (612 Mt) and the projected emissions level without policy measures (862 Mt) (Exhibit 1.5). The federal government expects that other cross-cutting regulations, such as the energy efficiency regulations managed by Natural Resources Canada, and economic measures that are complementary to the current sectoral approach will reduce emissions further. The federal government predicts additional reductions from current and planned regulations after 2020, but not enough to reverse the increasing trend in Canada’s total emissions.

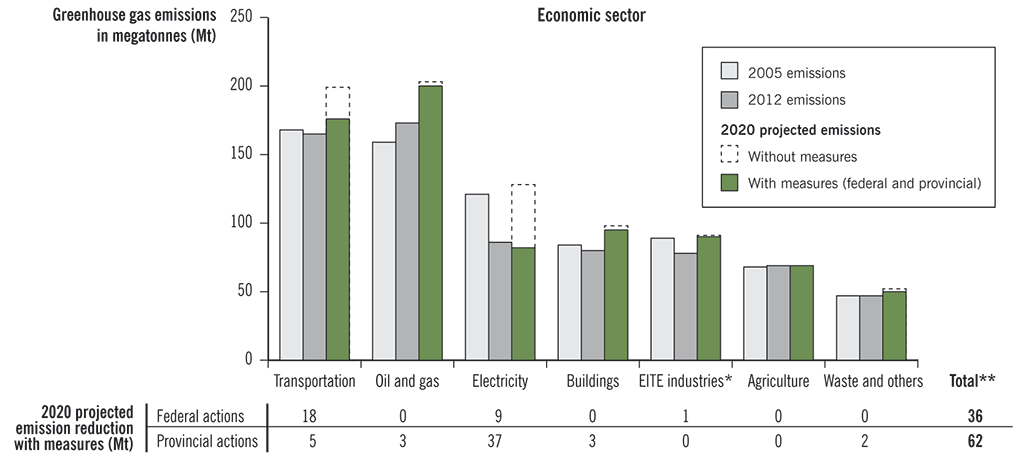

Exhibit 1.5—Current federal measures will have little effect on emissions by 2020

* EITE: emission-intensive trade-exposed industries

** Total emission reductions also include cross-cutting measures, which are estimated to be 8 Mt at the federal level, and 13 Mt at the provincial level. Cross-cutting measures are measures that affect more than one sector, such as the federal eco-efficiency programs or British Columbia’s carbon tax.

For each economic sector, the first bar in each group corresponds to the estimated greenhouse gas emissions for 2005, the baseline year for the Copenhagen Accord target. The second bar in each group corresponds to the most recent (2012) estimates of current emissions. The third bar in each group corresponds to the emissions projected by Environment Canada for 2020. The top of the third bar (“Without measures”) represents the projected emissions if none of the current or announced federal or provincial measures are taken into account. The solid portion of the bar corresponds to the projected emissions if all of the current and announced measures are included (“With measures”).

Sources: Canada’s National Inventory Report and Sixth National Communication on Climate Change and First Biennial Report to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

1.23 Process for regulatory development. In a Cabinet Directive and other documents, the federal government has set out its expectations for developing and managing regulations. In addition, Environment Canada has recently committed to following the principles respected by what it calls “world class regulators.” For example, one of the principles is transparency, described as follows: “Affected parties are engaged throughout the process to give stakeholders a voice, enable market certainty, reinforce credibility, and engender public trust.”

1.24 In our view, the Department’s approach to some of the planned regulations for greenhouse gas emissions has not been consistent with federal requirements and the principles of world-class regulation, in terms of the extent and nature of consultation. We noted earlier the problems with consultations on potential oil and gas regulations. In much the same way, Environment Canada did not advise all interested and affected parties that regulations would be developed for emission-intensive trade-exposed industries, such as the pulp and paper sector, and what the scope and timing of those regulations would be. The information Environment Canada has provided publicly about future greenhouse gas regulations—for example, in its forward regulatory plan—lacks the details and timelines provided for other federal regulations. We are also concerned about how the results of existing regulations are measured and reported (see paragraphs 1.27 and 1.28).

1.25 Recommendation. Given its commitment to be a world-class regulator, Environment Canada should publish its plans for future regulations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, such as the oil and gas regulations, with sufficient detail and lead time, so that consultations with interested and affected parties can be transparent and broadly based, and the parties can plan effectively.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Environment Canada is committed to transparency in implementing the government’s climate change agenda. The Department will continue to publish its Forward Regulatory Plan on an annual basis and update it semi-annually. This plan provides information on planned and potential regulatory initiatives, including sectoral greenhouse gas regulations as appropriate, that Environment Canada expects to bring forward over the next two years. The plan will also identify public consultation opportunities and a departmental contact point for each regulatory initiative. In addition, Environment Canada will continue to consult with stakeholders both pre- and post-publication of proposed regulations, to assist these parties in understanding proposed requirements and to allow them to plan effectively.

Departments are not yet assessing the success of current regulatory measures

1.26 In response to a recommendation in our 2012 audit report, Environment Canada committed to ensuring that mechanisms for assessing performance were put in place for each measure for which it is responsible. It also committed to reporting on the results achieved.

1.27 In this audit, we found that there are only two measures in place for which Environment Canada could assess the actual results: the regulations on renewable fuels and on passenger vehicles. Environment Canada is developing tools to obtain information electronically from the regulated parties, is tracking compliance, and has some interim results. However, for neither measure does it yet have sufficient reliable information to assess overall compliance, estimate the actual emission reductions resulting from the regulations, or take corrective action if necessary.

1.28 There has been a substantial lag in understanding and reporting how well these two regulations are working in practice. The Renewable Fuels Regulations have been in effect for almost four years. Regulations on emissions from passenger vehicles first applied to the 2011 model year, but the information to assess compliance will not be complete until 2015. For neither regulation has Environment Canada yet published reports describing the observed results. In addition, we were told that there has been no re-evaluation of expected reductions resulting from either of the two current regulations. Without this information, it is not possible to determine what lessons—for example, related to regulatory design—might be applied to other planned regulations or to the overall federal regulatory approach.

1.29 Recommendation. Environment Canada, with the support of Natural Resources Canada and Transport Canada, should publicly report the effects of the regulations currently in place to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. With the other departments, it should also identify the lessons learned from measuring the effects of these regulations and should apply them to planned regulations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The Department’s response. Agreed. In consultation with other federal departments and other key partners, Environment Canada will continue to report publicly on the results of its regulations currently in place. This will be done, for example, through the National Inventory Reports and Canada’s Emissions Trends. Environment Canada will also work with other federal departments and other partners, as appropriate, to examine lessons learned with a view to applying them to planned regulations.

Environment Canada is not coordinating with the provinces and territories to achieve the national target

1.30 In 2012, we found that Environment Canada was consulting with the provinces and territories on each regulation under development as part of its sector-by-sector approach. Committees made up of senior representatives of each government concerned had been formed to communicate and coordinate strategies, and to identify gaps in the development of regulations.

1.31 Because the federal government shares jurisdiction over environmental matters with the provinces and territories, the two levels of government need to coordinate their actions effectively and on a continuing basis to achieve the national target. This is particularly important with respect to climate change because of the diversity of provincial and territorial plans and targets (Exhibit 1.6). The latest estimates indicate that all federal measures will account for about 36 megatonnes, roughly a third of the predicted reduction resulting from action by all levels of government (see Exhibit 1.5). Environment Canada has indicated that the federal government is committed to implementing its sector-by-sector regulatory plan with the aim of making further reductions until the total reduction achieved by federal and provincial measures is sufficient to reach Canada’s 2020 target.

Exhibit 1.6—The provinces and territories have set a mix of reduction targets

| Province or territory | Date of latest plan |

Baseline year |

Reduction targets compared to baseline year | Deadline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | 2008 | 2007 | 6% (interim) | 2012 |

| 18% (interim) | 2016 | |||

| 33% (legislated) | 2020 | |||

| 80% (legislated) | 2050 | |||

| Alberta | 2008 | n/a | 20 megatonnes (Mt) below BAU1 | 2010 |

| 50 Mt below BAU | 2020 | |||

| 200 Mt below BAU | 2050 | |||

| Saskatchewan | 2010 | 2006 | 20% | 2020 |

| Manitoba | 2008 | 2000 | Stabilization at 2000 levels | 2010 |

| 1990 | 6% | 2012 | ||

| 2005 | 15% | 2020 | ||

| Ontario | 2007 | 1990 | 6% | 2014 |

| 15% | 2020 | |||

| 80% | 2050 | |||

| Quebec | 2012 | 1990 | 20% | 2020 |

| New Brunswick | 2014 | 1990 | 10% | 2020 |

| 2001 | 75% to 85% | 2050 | ||

| Nova Scotia | 2009 | 1990 | 10% (legislated) | 2020 |

| 2009 | Up to 80% | 2050 | ||

| Prince Edward Island | 2008 | 1990 | 10% | 2020 |

| 2001 | 75% to 85% | 2050 | ||

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 2011 | 1990 | 10% | 2020 |

| 2001 | 75% to 85% | 2050 | ||

| Yukon2 | 2009 | 2010 | 20% | 2015 |

| Carbon-neutral | 2020 | |||

| Northwest Territories | 2011 | 2005 | 0% | 2015 |

| Increase of 66% | 2020 | |||

| 0% | 2030 | |||

| Nunavut | No target announced |

1 BAU: business as usual, or trend in emissions without policy measures considered.

2 The Yukon targets shown apply only to internal government operations. In addition, the Government of Yukon has established a mix of different targets for different sectors of the economy, but no economy-wide target.

Sources: Provincial and territorial government information

1.32 The committee structure we observed in 2012 has evolved. Separate working-level committees, including industry and relevant provincial representatives, now focus on each of the existing and planned federal regulations (Exhibit 1.3). Environment Canada also meets bilaterally with provincial officials. However, one of the two strategic coordinating committees described in our 2012 audit report has not met since 2011. The other committee, a federal-provincial-territorial consultative committee at the deputy minister level, meets twice yearly, mainly to share information. Provincial and territorial officials meet bilaterally and multilaterally to discuss emission reductions, and on some occasions federal officials join these meetings. The provinces and territories are also taking action independently of the federal government, including working with US state governments.

1.33 Environment Canada has discussed with some provinces the possibility of using equivalency agreements, as provided for by the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999, as a way to avoid regulatory duplication or overlap between jurisdictions. An equivalency agreement allows the federal government to suspend the application of a federal regulation in a province or territory. In this context, the equivalency agreement declares that in the relevant province or territory there are laws in force containing provisions that will result in a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions equivalent to the given federal regulation. For example, in June 2014 Environment Canada announced the details of an agreement with the province of Nova Scotia regarding emissions from coal-fired electricity generating plants. Other provinces are interested in equivalency agreements. For instance, in June 2012 the federal government and the Government of Saskatchewan announced their intent to work toward an agreement, also based on the federal coal-fired electricity regulations.

1.34 During our audit work, we contacted all the provinces and territories to understand the evolving initiatives under way for reducing emissions and the extent to which, in their view, cooperation was important for success at a national level. Most of the officials we consulted cited the need for improved mechanisms for consultation and cooperation on national emission reduction initiatives. Other expert reports, including from the former National Round Table on the Environment and the Economy, have pointed to the same need.

1.35 Overall, we found that the federal government has not provided sufficiently focused coordination to meet its commitment of achieving the national 2020 emission reduction target jointly with the provinces and territories, or to address the need for further reductions beyond that date.

Environment Canada still does not have a planning process for how the federal government will contribute to achieving the national target

1.36 In 2012, we found that Environment Canada had no overall implementation plan that indicated how different regulations or how different federal departments and agencies would work together to achieve the reductions required to meet the 2020 target of the Copenhagen Accord. The Department had not provided an estimate of the emission reductions expected from each sector or a general description of the regulations needed in each sector. In the present audit, we found that this is still the case.

1.37 In our view, effective planning depends on well-understood objectives, measurable targets, clear roles and responsibilities, and appropriately coordinated actions. The federal government has described some of these elements in general terms in various places, but it does not have a documented implementation plan for its own actions to reduce emissions—a plan based on the sector-by-sector regulatory approach—that sets out what the government is trying to achieve in quantitative terms and what specific steps it will take to get there. Without such a plan, it is not possible to accurately estimate the costs and benefits of the federal approach, or to compare it with other possible approaches. Such a plan would answer questions such as:

- What additional or more stringent regulations will be needed in sectors already subject to regulation, and when?

- Which additional sectors does the federal government plan on regulating, and when?

- What measures to complement the sector-by-sector regulations does the federal government plan to put in place?

- Are there gaps in the provincial and territorial plans that the federal government is best positioned to fill?

1.38 Effective planning also involves regularly assessing progress, reviewing priorities, and revising action plans, if necessary. The annual national emissions inventory and the update of projected emissions described later in this chapter have put in place the foundation for this kind of regular review, as have the detailed National Communications to the United Nations.

1.39 To meet Canada’s long-term emission reduction objectives, the federal government, working with the provinces and territories, will need to plan for further reductions beyond 2020. It has not yet done this. We observed that some current federal actions will have effects after 2020 and that the federal government is considering further steps to reduce emissions, but there are no detailed federal objectives or consolidated plans for the period beyond 2020.

1.40 The absence of effective federal planning, including unclear timelines, leaves responsible organizations at all levels without essential information for identifying, directing, and coordinating their reduction efforts. It also means that there are no benchmarks against which to monitor and report on progress. For example, industries that may be affected by regulations cannot plan their investments effectively. In our view, the lack of a clear plan and an effective planning process is a particularly significant gap given that Canada is currently projected to miss its 2020 emission reduction target.

1.41 Recommendation. Environment Canada, working with other federal departments and agencies, should put in place a planning process that includes the following elements:

- a quantitative description of what contribution the federal government will make to Canada’s 2020 target and to reducing emissions beyond 2020;

- a detailed description of what measures it will take to do its part in achieving the national target, including planned timelines;

- a regular review to assess progress and identify how plans will need to be adjusted, if necessary (this should include the provinces and territories); and

- a regular report to Parliament so that Canadians understand what has been achieved and what remains to be done.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Environment Canada will strengthen its planning process by working with other federal departments and agencies in support of the government’s climate change agenda:

- Environment Canada will continue to publish reports, including Canada’s Emissions Trends, National Inventory Reports, Biennial Reports, and National Communications to provide a quantitative description of progress in reducing greenhouse gas emissions, as well as greenhouse gas projections for 2020 and beyond;

- The Department will continue to implement, within its mandate, the government’s sector-by-sector approach to reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Through its annual Forward Regulatory Plan, the Department will identify proposed new measures under development and associated timelines;

- Environment Canada will also continue to collaborate with provinces and territories as they implement measures to reduce emissions. To that end, Environment Canada will utilize existing federal-provincial-territorial mechanisms, and will enhance these mechanisms or create new forums where appropriate; and

- Environment Canada will report to Parliament and Canadians on progress on the issue of climate change through annual Reports on Plans and Priorities and Departmental Performance Reports.

Estimating Canada’s future emissions

1.42 In our 2012 audit, we recommended that Environment Canada forecast greenhouse gas emissions and reductions under various scenarios to inform decision making. We also recommended that the Department continue to report regularly on the trends in Canada’s emissions to support the development of greenhouse gas reduction measures.

1.43 In the present audit, we found that Environment Canada has produced forecasts and reports regularly, voluntarily providing Canadians with information about energy use and greenhouse gas emissions. This is a positive step. The Department has generally used sound methods to estimate and report future emissions; however, it could improve these methods by enhancing its modelling capacity, continuing to strengthen its internal training, and providing greater consistency and detail in its predictions and reports.

1.44 The government needs to have a good understanding of the likely future level of greenhouse gas emissions so that it can respond appropriately. Its analysis also provides a basis for reports to Canadians and international parties, including the Emissions Trends reports that we described in 2012 and the National Communications and Biennial Reports required under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

1.45 To meet these needs, Environment Canada has combined a detailed model of the Canadian economy with a model of energy use and greenhouse gas emissions. It also uses the modelling framework to analyze policy options, including possible regulations, for the purpose of understanding their economic implications. The Department is the main user of the framework, but Natural Resources Canada and the National Energy Board also use it for their own analyses as well as to ensure a common federal approach in areas of shared interest.

Environment Canada uses suitable methods for estimating future emissions but could improve its quality controls

1.46 We found that Environment Canada uses a variety of quality controls, including checks during data assembly and model runs by its analysts, and reviews of the outputs by external experts and provincial and territorial officials. By producing an updated forecast each year, analysts can identify and correct errors, make model enhancements, and ensure that the forecasts incorporate up-to-date information.

1.47 Input data. To project future emissions, the modellers need many kinds of input data, including population size, economic trends, energy use by different industries, and current and planned policy measures. In general, Environment Canada uses standard and credible data sources; for example, it uses information prepared by Statistics Canada, which has its own internal quality guidelines. We also found that the modellers have appropriate practices for obtaining, documenting, and checking the key inputs. We noted that there are opportunities for strengthening how the Department handles input data—for example, by using better quality control checklists and more complete documentation, especially when combining data from different sources.

1.48 The Department will also need to enhance its modelling capacity as a result of a significant change to a key source of input data. Statistics Canada has recently made fundamental changes in the way it categorizes and describes the Canadian economy in its system of national accounts. This means that the economy model used until now by Environment Canada, and similar models used by other private and public organizations, are no longer compatible with the new input data. The Department has begun the process of acquiring a replacement economy model to respond to these changes.

1.49 The inputs integrated into the emission forecasts also include separate forecasts provided by external parties, which are subject to their own quality controls. For example, the predictions of the future state of the Canadian economy are based on and then matched to those of the Department of Finance Canada. Environment Canada relies on the National Energy Board for forecasts of future oil and gas production. Independently of Environment Canada’s forecasting process, Natural Resources Canada provides estimates of current and future emissions from Canada’s forests (Exhibit 1.7).

Exhibit 1.7—Estimating emissions from forests poses challenges

Photo: mironov/Shutterstock.com

As forests grow, they absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. They release greenhouse gases when they die, whether by fire, insect attack, or harvesting. This means that a forest may be a “sink” for greenhouse gases one year and a “source” the next. Since Canada has the third-largest forested area in the world, the year-to-year differences can overwhelm other changes in our country’s emissions. In addition, of the total 348 million hectares of forest in Canada, an area of about 116 million hectares is considered unmanaged forest where humans do not undertake management activities, such as harvesting or fighting forest fires. According to analysis by the Canadian Forest Service of Natural Resources Canada, there is a high risk that Canada’s managed forests will be a net annual source of greenhouse gases in the future because of natural disturbances, including fires and insect attacks. These natural disturbances are beyond human control.

To address these and related calculation and reporting issues, the parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change have developed a set of accounting rules that will move countries toward comparable estimates for what is termed the Land Use, Land-Use Change, and Forestry (LULUCF) sector. Under these rules, for example, reports on the sector may exclude the year-to-year changes due to natural disturbances provided that any exclusion is transparent and the effects of the subsequent forest regrowth are also excluded.

1.50 Key assumptions. We also wanted to know whether Environment Canada ensures that key assumptions in the modelling framework are appropriate and well documented. For the energy use model, Environment Canada modellers have satisfied themselves that the core assumptions are appropriate and credible. We found that the energy use model, including its underlying assumptions, is well documented. Improvements are needed to the documentation of the economy model, including the specific assumptions and procedures underlying the use of the model. Environment Canada has been working to address this gap.

1.51 Calculation methods. We observed that the modelling framework has an appropriate scope and considerable detail, allowing modellers to examine the changes in emissions resulting from individual policies or combinations of policies.

1.52 Environment Canada and the other federal entities using the modelling framework rely on the expertise of consultants to make changes to the framework. To reduce the reliance on third-party consultants, the Department is continuing to train its staff on the key model functions.

1.53 External reviews. Environment Canada follows a good practice by commissioning external reviews of different aspects of its models, reports, and outputs. The external reviews used by Environment Canada include peer reviews, in which external experts examine the draft Emissions Trends report and the associated model outputs. Reviews are performed as a step leading to publication of the reports. Partly for this reason, the reviews are performed quickly and with limited opportunity to examine the details of the models. However, reviewers were able to identify errors in how data was reported and also raised issues about how the models are managed.

1.54 External reviews are most valuable if they provide a basis for continual improvement. The 2013 Emissions Trends report documented technical changes resulting from a combination of external and internal reviews. When we compared the recommendations made by the peer reviewers with the final version of the report, we found that Environment Canada had not systematically tracked reviewers’ concerns (especially suggestions for possible long-term improvements) and its own responses. Consequently, the Department is not fully using the opportunities to improve its modelling framework.

1.55 Other external reviewers include the National Energy Board, Natural Resources Canada, and the provinces and territories. If Environment Canada gave other levels of government additional details and results for their review, the Department could strengthen how it models provincial and territorial policies.

1.56 Taking these internal and external reviews together, we found that all key elements of the modelling framework are subject to some review but there are opportunities to strengthen the quality control. For comparison, the US National Energy Modeling System provides detailed public information on its modelling framework and results, and is open to public review.

1.57 Recommendation. To strengthen its quality controls and increase its transparency, Environment Canada should take steps to enhance external review of its climate change modelling framework. For its projection of the most likely future path of emissions, the Department should provide greater access to model inputs, assumptions, and outputs, as well as details about the way policies are modelled. This would include full documentation of the modelling framework.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Environment Canada has a strong commitment to the external review of its modelling framework and projections. Not only does it submit Canada’s Emissions Trends report and its underlying projections for peer review, Environment Canada participates in the internationally-recognized Stanford University Energy Modeling Forum.

Having said this, Environment Canada will continue to strengthen its quality controls and increase its transparency for estimating future emissions.

With respect to enhancing quality control, Environment Canada will

- continue to automate the data input process to ensure more effective and efficient data review, and

- increase the data review steps by senior analysts and managers.

With respect to increased transparency for estimating future emissions, Environment Canada will

- continue to engage officials in other federal departments and provinces and territories;

- increase the frequency of bilateral, and, where appropriate, multilateral discussions with key Canadian energy/emissions modellers;

- seek advice on the level of information required to make informed judgments on the modelling approach, inputs, assumptions and outputs;

- continue to submit Canada’s Emissions Trends report and its underlying projections to peer review by recognized Canadian modelling experts and provincial and territorial officials; and

- identify internationally recognized expert reviewers and submit its emissions projections and modelling framework to international peer review.

Environment Canada can better communicate emission information to support decisions

1.58 In December 2013, the federal government released Canada’s Sixth National Communication and First Biennial Report on Climate Change, as required under the Framework Convention. These documents comprehensively summarized the status of Canadian action on climate change. For the first time, the government gave a public estimate of emissions for 2030 as well as the effects by 2020 of the main federal and provincial actions to reduce emissions. Based on our analysis, the report met core international reporting guidelines. (The Convention Secretariat plans to coordinate its own expert review of Canada’s National Communication.)

1.59 In general, we found the main reports prepared by Environment Canada strive for an objective presentation of information. The systematic format of the reports contributes to the objectivity. We found, however, four specific areas where additional information could support better decisions (Exhibit 1.8).

Exhibit 1.8—Environment Canada's emission reports could include additional information relevant to decision makers

1.60 First, readers could more easily interpret the charts if they had a clearer explanation of what is included in different projections especially the “Without measures” projection, which estimates the emissions if reduction measures had not been taken. Second, while there are technical challenges involved, it would be useful to separately indicate the federal and provincial contributions to emission reductions as far as possible; this would help policy makers at different levels to evaluate the effect of their own policies in a common framework (see Exhibit 1.8, Chart B, Effects of federal and provincial measures).

1.61 Third, it is important for the modellers projecting future emissions to indicate to decision makers the degree of confidence in their projections (see Exhibit 1.8, Chart C, Emissions with estimates of uncertainty [excluding LULUCF]). We observed that Environment Canada reported some limited information about the reliability of its projections, specifically in the form of alternative projections; for example, it considered what might happen if economic growth was higher or lower than assumed. However, the Department did not address other aspects of uncertainty, such as the overall reliability of its projections or the sensitivity to the price of natural gas. Communicating the uncertainty associated with estimates is a good practice applied in other countries, and much of the information and tools for doing it are available.

Land Use, Land-use Change, and Forestry (LULUCF) sector—A sector that includes emissions to and removals of greenhouse gases from the atmosphere resulting from direct human-induced land use, changes to land use, and forestry activities. Activities in this sector include wildfires in managed forests, timber harvesting, and conversion of forested land to agriculture.

1.62 Fourth, Environment Canada could more clearly and consistently describe the effects of forest management on Canada’s emissions. In its reports, the Department presented the Land Use, Land-Use Change, and Forestry (LULUCF) sector (see Exhibit 1.7) as contributing a reduction of 28 megatonnes (about 19 percent) to the achievement of Canada’s emission reduction target (see Exhibit 1.8, Chart D, Emissions excluding and including contribution from LULUCF sector). Based on the accounting rules being applied, this contribution is not the result of specific efforts to reduce emissions; instead, it mainly reflects the fact that forest harvest levels up to 2020 are now predicted to be lower than past average forest harvest levels. In effect, the contribution attributed to this sector is partly the consequence of the recent economic recession. In some places, the Emissions Trends report and other Environment Canada reports based on it communicate this difference in harvest levels as if it were a planned policy measure to reduce emissions rather than part of the underlying economic circumstances.

1.63 Recommendation. Environment Canada, working with Natural Resources Canada, should improve the value to decision makers of its climate change reports by describing the key assumptions, separately indicating the impact of federal and provincial measures as far as possible, communicating the uncertainty associated with its estimates, and more appropriately and consistently describing the future emissions from Canada’s forests.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Environment Canada has taken steps to improve its transparency on climate change reporting and is committed to continuous improvement. Since 2011, Environment Canada has reported greenhouse gas emissions projections through Canada’s Emissions Trends. This report, which has been well-received by stakeholders, has evolved since its inception to include enhanced descriptions and recommendations from external reviewers.

While Environment Canada’s approach presents information in a complete and transparent manner, we acknowledge that there is room for improvement. In future reports, Environment Canada will

- continue to ensure that its climate change reports are consistent with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) guidelines for preparing emissions projections, and

- provide a more comprehensive and clearer discussion of the sensitivity analysis undertaken for emissions projections.

Environment Canada, working with the Canadian Forest Service of Natural Resources Canada, will continue to

- estimate and report future emissions/removals from Canada’s forests, and more generally from land use, land-use change, and forestry activities, using methods that are consistent with Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change guidelines; and

- appropriately describe the application of UNFCCC rules and approaches as they evolve.

Managing Canada’s fast-start financing

1.64 In line with its international commitments, Canada has also supported action in developing countries to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and to adapt to climate change. Under the 2009 Copenhagen Accord, Canada and other developed countries together committed to providing US$30 billion in new and additional resources for the years 2010 to 2012 so that developing countries could better respond to climate change. For its part, the Government of Canada pledged to provide $1.2 billion through the resulting fast-start financing initiative over the three years; this amounts to approximately 4 percent of the total pledge, a proportion similar to Canada’s traditional contribution to multilateral funds. Under the Accord, Canada and other developed countries together also committed to a longer-term goal of mobilizing US$100 billion a year by 2020 from all funding sources, including the private sector, in the context of developing countries taking action to reduce their emissions and reporting on progress.

1.65 Overall, we found that Environment Canada, working with others, is tracking, assessing, and reporting on funding under the initiative and the results achieved so far. While the Department has developed an interactive website to provide details on the projects funded by Canada’s share of the initiative, it could improve the consistency and value of its public reports by including information about the status of project spending and the flows of funds back to Canada. It could also work with its federal and international partners to improve the prediction and assessment of results, including greenhouse gas emission reductions. This collaboration and coordination will be particularly important in view of the global efforts to reduce emissions and adapt to a changing climate.

The government has disbursed its funds but most of the money has not yet reached the final recipients

1.66 As it committed to do under the Copenhagen Accord, the federal government disbursed all of the funds that Canada pledged to provide, in almost equal amounts for the 2010–11, 2011–12, and 2012–13 fiscal years. Environment Canada is the department with overall responsibility for the fast-start financing initiative, but the Department of Finance Canada disbursed $352 million and the former Canadian International Development Agency disbursed $760 million.

1.67 The initiative funds a wide range of projects. For example, the Inter-American Development Bank allocated about $21 million from Canada to help finance a large solar power project intended to supply clean energy to the Chilean mining industry. When operational, the project is expected to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 0.056 megatonnes a year. Environment Canada also allocated about $750,000 to Engineers Canada for a project in Honduras that identifies risks to highway bridges from climate change and provides training to local engineers.

Through the Inter-American Development Bank, the Government of Canada provided fast-start funding to the Pozo Almonte and Calama Solar Photovoltaic Power Project in Chile.

Photo: © Inter-American Development Bank

1.68 Funding mechanisms. The federal government supplied funds for its share of the fast-start financing initiative by using a mix of grants and concessional financing (unusually advantageous financing), mainly in the form of repayable contributions. The government gave some of the funding in the form of grants directly to countries or projects, but it transferred most of it ($884 million, or 74 percent) as repayable contributions to multilateral banks, such as the Asian Development Bank or the International Finance Corporation, which acted as intermediaries in providing the financing. In some of these cases, the Canadian contributions went into a dedicated fund, allowing specific results to be attributed to Canada; in others, the funds were combined with money from other donors. The use of repayable contributions affects which projects are chosen to receive funding because the projects must generate revenue so that they can repay the contribution.

1.69 Since 1986, Canada has provided developing countries with Official Development Assistance mainly through grants or funds transferred to multilateral banks. In contrast, most of the fast-start financing has used a new approach: while the funds are managed by multilateral banks, they are to be repaid to Canada. Repayable contributions have several potential advantages. For example, they reduce the costs to Canadian taxpayers since the funds are expected to come back to the federal treasury over the next 20 to 25 years. A disadvantage is that repayable contributions increase the debt levels of the final recipients. The net effect on the federal government’s accounts will depend on interest rates, repayment schedules, and risks. However, one estimate is that more than $615 million of the $1.2 billion disbursed as agreed under the Copenhagen Accord could eventually be repaid to Canada.

1.70 In the 2013 Spring Report of the Auditor General, Chapter 4—Official Development Assistance through Multilateral Organizations, we raised concerns about the information provided to Parliament on the use of repayable loans, including for part of the fast-start financing initiative. In the present audit, we found that public reports did not clearly present the financial consequences of the fact that many of the loans were repayable to Canada. Our recommendation to address this concern is found in paragraph 1.74.

1.71 Consistency with federal policies and international commitments. Based on the files we examined, we found that Canada provided funding in accordance with key federal requirements, such as those for periodic reports and provisions for audits. We noted that Environment Canada went from having no responsibility for reporting international assistance to being fully responsible for reporting Canada’s climate financing over a three-year period. The Copenhagen Accord and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change provide new and detailed reporting requirements for the fast-start funds. As required, Environment Canada described how the resources would be considered to be “new and additional.”

1.72 Tracking disbursements. We found that Environment Canada is recording the disbursement of funds, and relies on information from other federal entities and multilateral banks to prepare a consolidated summary of the financial status. Based on this information, we noted that as of 30 May 2014 about 73 percent of the money going to multilateral banks was still not committed at the project level (Exhibit 1.9); projects were not yet identified and approved, with the result that disbursements were taking longer than originally expected. In one case, the contribution agreement with the bank had to be amended to allow an additional two years to disburse the funds. One contributing factor has been the need to put administrative structures in place to ensure due diligence; another has been the project approval process. The time required for these steps leads to delays in achieving reductions in greenhouse gas emissions or taking other kinds of climate change action. The Copenhagen Accord called for the resources to be provided “for the period 2010–2012” but did not set out more specific expectations for the timing.

Exhibit 1.9—By 30 May 2014, most fast-start financing funds had not yet reached the projects to be funded

| Funding category | Funding recipient or intermediary | Amount disbursed by the Government of Canada (CAN$ millions) |

Amount committed to final recipients (CAN$ millions) and percentage of amount disbursed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Repayable contributions to multilateral banks | International Finance Corporation | 352 | 129 (37%) |

| Inter-American Development Bank | 250 | 22 (9%) | |

| Asian Development Bank | 82 | 35 (43%) | |

| Clean Technology Fund, World Bank | 200 | n/a | |

| Grants to other multilateral institutions and bilateral support | Various | 309 | n/a |

| Total | 1,193 |

Notes:

- The Clean Technology Fund pools the funds from several donor countries so it is not possible to identify what proportion of Canadian funds have been disbursed.

- The amounts committed by multilateral banks to final recipients will be greater than the amounts actually disbursed to date.

- Some, but not all, information in this table has been subject to independent financial audit.

Sources: Environment Canada; Department of Finance Canada; Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada; and public reports from listed organizations

1.73 Reporting disbursements. To report on Canada’s contribution, Environment Canada has used a dedicated interactive website and public reports, including the latest National Communication and Biennial Report to the Framework Convention. These reporting tools give details on the funding approved and the wide variety of individual projects receiving support. Environment Canada is further upgrading its online database, including features to allow information sharing with other federal entities. During our audit, however, we found some inconsistencies and errors in the information presented in the National Communication; these included the lists of projects and the total amount of funding. Environment Canada has since corrected the public information. We also observed that Environment Canada is not reporting details of the status of project disbursements and expected and actual repayments to Canada by the various multilateral organizations. In our view, this information would help Canadians better understand the status and effect of this initiative.

1.74 Recommendation. In addition to the information currently provided, Environment Canada, with its partners for the fast-start financing initiative, should regularly publish a consistent, full summary of the project disbursements and the actual amounts repaid to Canada, subject to commercial confidentiality constraints. It should also describe the risks associated with the repayable contributions, indicate the extent to which concessionary terms and conditions apply, and provide an estimate of the impact of these risks on the amount that will ultimately be repaid to Canada.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Environment Canada is committed to providing transparent information to Canadians and our international partners on Canada’s climate financing and its results, notably through Canada’s climate finance website, Canada’s National Communications, and Biennial Reports to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, and through other relevant reporting on Canada’s international assistance.

Environment Canada is working to track progress but it is too early to assess emission reduction results

1.75 Specifying expected results. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions is one of the key objectives of the projects being supported through the fast-start financing initiative. We found that Environment Canada and its federal partners are receiving information on the status of projects, but the different expected outcomes from the funding are not clearly and consistently identified. For funds transferred to multilateral banks, the contribution agreements describe the expected results, but only in general terms. We examined selected bilateral funding contribution agreements with Environment Canada. Based on these, we found that the agreements do not clearly describe the expected results, including how they will contribute to quantified emission reduction objectives when relevant. As a result, it is unclear what the net effect of the financing will be on greenhouse gas emissions.

1.76 A group of multilateral banks, including some that have received Canadian funds, is now working to develop estimates of the effects on greenhouse gas emissions from different kinds of projects. As this initiative and similar ones advance, they may help to establish consistent, measurable indicators, relevant baselines, and appropriate expectations for project results.

1.77 Assessing and reporting results. Most funds have not yet been allocated and most projects have not been completed. It is therefore too early to fully assess the results or attribute the results to particular factors. Accordingly, it is also too early to determine the overall success of this program, but there is an opportunity to identify and apply the lessons learned so far to both the fast-start financing remaining to be allocated by the banks and to future financing to address climate change. With its domestic and international partners, Environment Canada has begun to do this.

1.78 In a global context, the fast-start financing initiative is laying the groundwork for a larger international effort to support mitigation and adaptation measures in developing countries. As we have noted, Canada and other developed countries together committed to a longer-term goal of mobilizing US$100 billion a year by 2020 from all funding sources, in the context of developing countries taking action to reduce their emissions and reporting on progress.

1.79 Recommendation. Environment Canada, in collaboration with its Canadian and international partners, should ensure that the lessons learned from the fast-start financing experience are synthesized and applied to future climate change financing. These lessons could include

- which financing approaches and types of projects are most likely to achieve the desired outcomes, including emission reductions;

- the need for realistic estimates of the time required to make financing arrangements; and

- the need for effective measurement and reporting for both predicted and actual results.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Environment Canada will continue to work within its mandate with its partners to synthesize and apply the lessons learned from the fast-start financing experience, including with a view to informing international discussions on climate finance in the run up to the 21st Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in December 2015, where the Parties are expected to adopt a new international climate change agreement for the post-2020 period.

Conclusion

1.80 We concluded that progress in addressing four key issues from our last audit has been unsatisfactory. While the Government of Canada has recognized the need to urgently combat climate change, its planning has been ineffective and the action it has taken has been slow and not well coordinated. The sector-by-sector regulatory approach led by Environment Canada has made some gains, but the measures currently in place are expected to close the gap in greenhouse gas emissions by only 7 percent by 2020, and the actual effects of these measures have not yet been assessed. Environment Canada also lacks an approach for coordinating actions with the provinces and territories to achieve the national target. We are concerned that Canada will not meet its 2020 emission reduction target and that the federal government does not yet have a plan for how it will work toward the greater reductions required beyond 2020.

1.81 Environment Canada’s modelling framework is an essential tool to meet internal and external planning requirements—to project the likely path of future emissions and to fully assess possible emission reduction policies, singly or in combination. We concluded that the Department has generally used sound methods to estimate and report future greenhouse gas emissions. In our view, its practices could be improved by enhancing its modelling capacity, continuing to strengthen its internal training, and providing greater detail and consistency in its projections and reports.

1.82 Through the fast-start financing initiative, Environment Canada, working with others, disbursed the $1.2 billion pledged by the Government of Canada to provide support to developing countries. We concluded that Environment Canada, working with others, is tracking, assessing, and reporting on this initiative and the results achieved so far. While the Department has developed an interactive website to provide details on the projects funded by the initiative, it could improve the consistency and value of its public reports by including information about the status of project spending and the flow of funds back to Canada. It could also work with its federal and international partners to improve the prediction and assessment of results, including in terms of greenhouse gas emission reductions. Collaboration and coordination will be essential to achieve the deep cuts in global emissions that the international community has recognized are required.

About the Audit

The Office of the Auditor General’s responsibility was to conduct an independent examination of federal government activities having the objective of estimating and reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs.

All of the audit work in this chapter was conducted in accordance with the standards for assurance engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA) in the CPA Handbook—Assurance. While the Office adopts these standards as the minimum requirement for our audits, we also draw upon the standards and practices of other disciplines.

As part of our regular audit process, we obtained management’s confirmation that the findings reported in this chapter are factually based.

Objectives

The objectives of this audit were to determine whether Environment Canada, working with others,

- has made satisfactory progress in addressing key issues presented in the 2012 Spring Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Chapter 2—Meeting Canada’s 2020 Climate Change Commitments;

- has used sound methods for estimating and reporting Canada’s future greenhouse gas emissions; and

- is tracking, assessing, and reporting on Canada’s participation in the fast-start financing initiative and the results achieved, including greenhouse gas emission reductions.

Scope and approach

We focused on the responsibilities of Environment Canada, Natural Resources Canada, and Transport Canada. For the first objective, we followed up on key observations and recommendations from our 2012 Spring Report Chapter 2—Meeting Canada’s 2020 Climate Change Commitments. We examined progress in four areas:

- putting measures in place to reduce greenhouse gas emissions;

- assessing the success of the measures;

- working with provinces and territories; and

- developing plans to achieve the 2020 Copenhagen Accord target.

We assessed progress by drawing on several sources of information, including departmental plans and commitments, some of which were made in response to our 2012 recommendations. For the second objective, we considered the annual projections produced since 2011, with an emphasis on the latest reports, and looked at selected aspects of the input data and the modelling framework. We did not examine how Environment Canada estimates and reports historical and current emissions, for example in the National Inventory Report.

For the third objective, we focused on the completed three-year fast-start funding, and how Environment Canada managed this initiative. We obtained information about the roles of the Department of Finance Canada and the Canadian International Development Agency (now part of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada), but did not audit them.

Our methods included interviews, document reviews, and step-by-step review of how Environment Canada prepares its projections of greenhouse gas emissions. To better understand the provincial and territorial roles and perspectives, we conducted a survey of all provincial and territorial offices responsible for managing climate change. We did not audit the actions of provincial or territorial governments. We also did not audit the multilateral banks, other multilateral organizations, or other governments that helped to distribute the fast-start financing.

Criteria

To determine whether Environment Canada, working with others, has made satisfactory progress in addressing key issues presented in the 2012 Spring Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Chapter 2—Meeting Canada’s 2020 Climate Change Commitments, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

| Environment Canada, working with Transport Canada and others, has put in place emission reduction measures that are consistent with good practices for regulatory development. |

|

| Environment Canada, working with Transport Canada and others, has assessed the success of current measures. |

|

| Environment Canada has mechanisms for working with the provinces and territories to reduce emissions. |

|

| Environment Canada, working with others, has an implementation plan that describes how federal entities will contribute to achieving Canada’s emission reduction target. |

|

To determine whether Environment Canada, working with others, has used sound methods for estimating and reporting Canada’s future greenhouse gas emissions, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

| Environment Canada has adequate systems and practices in place to provide assurance that the information it uses as a base for its estimates of future emissions is high-quality and sufficient. |

|

| Environment Canada, working with Natural Resources Canada and others, has used methods for estimating future emissions that are suitable for the intended purpose and consistent with good practices. |

|

| Environment Canada has prepared reports that communicate the information about future emission estimates and reduction measures accurately and fairly to national and international stakeholders. |

|

| Environment Canada, working with others, has put in place quality control processes to ensure the estimates of future emissions are of sufficient quality. |

|

To determine whether Environment Canada, working with others, is tracking, assessing, and reporting on Canada’s fast-start financing and the results achieved, including greenhouse gas emission reductions, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

| Environment Canada, working with others, is tracking and reporting on Canada’s fast-start financing, in accordance with international commitments and federal policies. |

|

| Environment Canada, working with others, is assessing and reporting on the results achieved by the fast-start financing funds, including reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. |

|

Management reviewed and accepted the suitability of the criteria used in the audit.

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period between January 2011 and July 2014. Audit work for this chapter was completed on 5 August 2014.

Audit team

Principal: Kimberley Leach

Lead Director: Peter Morrison

Director: Roger Hillier

Vineet Goswami

Kristin Lutes

David Wright

For information, please contact Communications at 613-995-3708 or 1-888-761-5953 (toll-free).

Hearing impaired only TTY: 613-954-8042

Appendix—List of recommendations