2019 Spring Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the Parliament of Canada Independent Auditor’s ReportReport 1—Aquatic Invasive Species

2019 Spring Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the Parliament of CanadaReport 1—Aquatic Invasive Species

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

- Assessing the risks posed by aquatic invasive species

- Preventing aquatic invasive species from becoming established

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada lacked a strategic approach to prevent aquatic invasive species from entering and spreading within Canada

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Canada Border Services Agency did not adequately enforce the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada did not respond rapidly to known threats

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- List of Recommendations

- Exhibits:

- 1.1—The case of the clubbed tunicate: How species invasions happen

- 1.2—It costs less to prevent the introduction of aquatic invasive species than to delay action and manage them once established

- 1.3—Case study: Eurasian water milfoil—Fisheries and Oceans Canada was not prepared for aquatic plant invasions

- 1.4—The invasive green crab is at risk of spreading farther along Canada’s east and west coasts

- 1.5—Case study: Zebra mussel—This invasive species was not properly intercepted at certain international border points

- 1.6—Case study: Asian carp—Fisheries and Oceans Canada had a response plan for one group of species

Introduction

Background

1.1 Invasive species are plants, animals (including fish), and micro-organisms that are introduced outside their natural habitats and that can harm the environment, the economy, or society. Invasive species can displace native species by competing for food, degrading habitats, and introducing diseases. The harm caused by invasive species can reduce biodiversity.

1.2 The number of at-risk fish, molluscs, and plants in Canada has been climbing for decades, and invasive species are a key reason for the increase. The Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations list about 174 species.

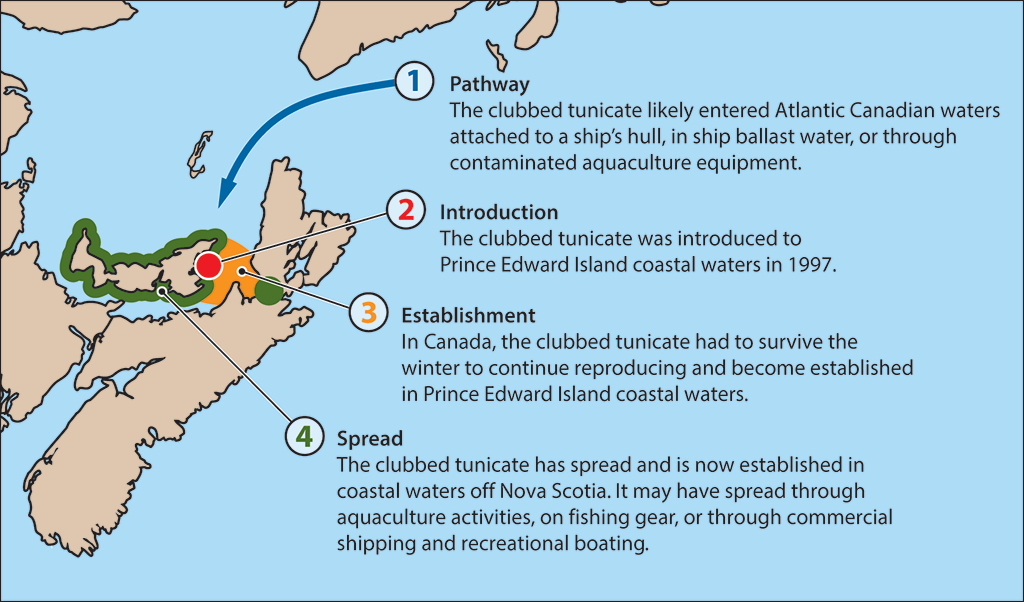

1.3 A species invasion (Exhibit 1.1) starts with the species’ pathwayDefinition i into Canada. Humans may move the species outside of its natural range (known as introduction).Definition ii The species reproduces and becomes established,Definition iii after which it spreadsDefinition iv to other areas.

Exhibit 1.1—The case of the clubbed tunicate: How species invasions happen

Considered one of the world’s most troublesome invaders, the clubbed tunicate is an invertebrate aquatic species that forms dense, abundant colonies. Academic and government scientists have estimated its economic cost to the Canadian shellfish industry to be in the tens of millions of dollars. Here is the story of its spread.

Photo: Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Source: Based on information provided by Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Exhibit 1.1—text version

This map shows the areas in Atlantic Canadian waters where clubbed tunicates entered and the progression through four stages of this species’ invasion.

The first stage is the entry of the clubbed tunicate into Atlantic Canadian waters, through a route or pathway. It likely entered attached to a ship’s hull, in ship ballast water, or through contaminated aquaculture equipment. The direction of the pathway is from east to west through waters south of the Island of Newfoundland and north of Nova Scotia.

The second stage is the introduction. The clubbed tunicate was introduced to Prince Edward Island coastal waters in 1997.

The third stage is the establishment. In Canada, the clubbed tunicate had to survive the winter to continue reproducing and become established in Prince Edward Island coastal waters.

The fourth stage is the spread. The clubbed tunicate has spread and is now established in coastal waters off Nova Scotia. It may have spread through aquaculture activities, on fishing gear, or through commercial shipping and recreational boating.

Source: Based on information provided by Fisheries and Oceans Canada

1.4 Aquatic invasive species can

- damage fisheries, shipping, aquaculture, and tourism;

- put stress on ecosystem functions, processes, and structures;

- litter beaches and foul docks; and

- damage hydroelectric and drinking water filtration facilities.

These species cause socio-economic and health effects and can have profound social and cultural impacts on Indigenous peoples and communities that rely on water resources.

1.5 The costs associated with managing aquatic invasive species are high. For example, according to the Great Lakes Fishery Commission, Canada and the United States budgeted about CanadianCAN$40 million combined in the 2019–20 fiscal year to control just one species—sea lamprey—that has significantly affected Great Lakes fisheries.

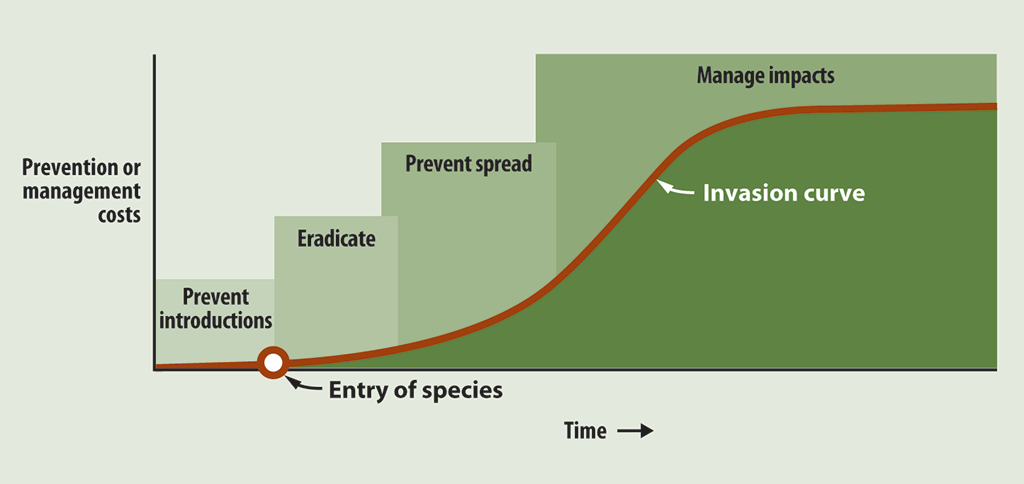

1.6 In general, it costs far less to prevent an aquatic invasive species from entering an area than to control it afterwards (Exhibit 1.2). Costs rise when it becomes necessary to eradicate a species, prevent its spread, or manage its impact once established. Swift detection and action are critical to keep a species from becoming established.

Exhibit 1.2—It costs less to prevent the introduction of aquatic invasive species than to delay action and manage them once established

Source: Adapted from Invasive Plants and Animals Policy Framework, Department of Primary Industries (since changed to Department of Jobs, Precincts, and Regions), State of Victoria, Australia

Exhibit 1.2—text version

This chart shows that it costs less to prevent the introduction of aquatic invasive species than to delay action and manage them once they are established.

Preventing the introduction of a species is the action that costs the least. If action is delayed until after the entry of a species, then costs rise according to the amount of time taken to act.

After the entry of a species, the order of actions from least costly to most costly are as follows: eradicating a species, preventing the spread of a species, and managing the impacts of a species.

As time passes, and the species reproduces and spreads, managing the invasion of a species becomes more difficult. The relationship between the stages of species invasion and costs to respond to the invasion is illustrated through the invasion curve. If action is delayed until after the species has become established and has spread, then the impacts must be managed, and the species invasion is at its peak.

Source: Adapted from Invasive Plants and Animals Policy Framework, Department of Primary Industries (since changed to Department of Jobs, Precincts, and Regions), State of Victoria, Australia

1.7 Climate change can make habitats more vulnerable to aquatic invasive species. As water temperatures rise, more non-native species can survive the winter in Canadian waters. Although it may be difficult or impossible to prevent species from extending their habitat ranges (often northward) because of warming temperatures, it is possible to manage some of the human pathways by which species can enter Canada. For example, species that attach to recreational boats can be prevented by decontaminating exposed surfaces.

1.8 The Fisheries Act gives Fisheries and Oceans Canada a broad mandate to protect fish and fish habitat. The 2015 Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations further empower the Department to prevent the introduction and spread of aquatic invasive species and manage established species. Federal, provincial, and territorial officials may also be empowered to take prevention actions, and may be designated as fishery officers or guardians to enforce these federal regulations.

1.9 Fisheries and Oceans Canada runs the Aquatic Invasive Species Science Program and initiated the Aquatic Invasive Species National Core Program in 2017. These programs are meant to

- prevent the introduction of aquatic invasive species,

- respond rapidly when new species are detected,

- manage the spread of established species, and

- work with other jurisdictions to ensure national consistency and collaboration on issues related to managing aquatic invasive species.

1.10 The Department’s Asian Carp Program was charged with carrying out Asian carp prevention and response activities.

1.11 The Canada Border Services Agency helps Fisheries and Oceans Canada to enforce the import prohibitions in the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations. The Customs Act authorizes border services officers to examine imported goods and detain any that are prohibited or controlled under regulations, including the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations.

1.12 Canada’s international and domestic commitments to address the risks posed by invasive species go back several decades. Canada signed on to the United Nations’ Convention on Biological Diversity in 1992. In 2010, it updated its commitment, agreeing to Aichi Biodiversity TargetDefinition v 9: “By 2020, invasive alien species and pathways are identified and prioritized, priority species are controlled or eradicated, and measures are in place to manage pathways to prevent their introduction and establishment.”

1.13 In 2015, Canada committed to achieving the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. This audit supports the goal of life on land (Goal 15 of the United Nations’ sustainable development goals),Definition vi which sets a target to do the following: “By 2020, introduce measures to prevent the introduction and significantly reduce the impact of invasive alien species on land and water ecosystems and control or eradicate the priority species.”

1.14 Fisheries and Oceans Canada is the federal department responsible for coordinating efforts on and for acting on aquatic invasive species to meet international targets. The Canada Border Services Agency has committed to helping Canada meet its biodiversity targets.

Focus of the audit

1.15 This audit focused on whether Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Canada Border Services Agency implemented adequate measures to prevent aquatic invasive species from becoming established in Canadian waters. We examined the organizations’ activities to prevent introductions, to detect and respond to invasions, and to prevent the spread of aquatic invasive species.

1.16 Specifically, we examined whether Fisheries and Oceans Canada

- determined which species and pathways posed the highest risks,

- used a strategic approach to prevent the introduction and spread of aquatic invasive species,

- enforced the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations, and

- responded rapidly to threats of invasions.

1.17 We also looked at whether the Canada Border Services Agency helped enforce the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations at international border points.

1.18 This audit is important because aquatic invasive species can devastate biodiversity and ecosystem functions. These species can compete aggressively with native species for food and survival, harming fish, fish habitat, and fisheries. This can have negative impacts on the communities and Indigenous peoples that depend on these resources. Along with damaging infrastructure, aquatic invasive species can foul beaches and ruin sport fishing, affecting tourism and local economies.

1.19 We did not examine how Fisheries and Oceans Canada managed aquatic invasive species where they were already established. We did not examine the oversight of aquatic invasive species by Transport Canada, including its regulation of ballast water.

1.20 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Overall message

1.21 Overall, we found that Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Canada Border Services Agency had not taken the steps required to prevent invasive species, such as the zebra mussel, green crab, and tunicates, from becoming established in Canada’s waters despite commitments to do so over the years. Fisheries and Oceans Canada had not determined which species and pathways posed the greatest threats to Canada’s environment and economy and to human health and activities, and it had not determined which species were the most important to regulate.

1.22 Fisheries and Oceans Canada had, however, taken significant action to prevent Asian carp species from becoming established in the Great Lakes, and in 2017, the Department received additional funding to deal with aquatic invasive species.

1.23 We also found that Fisheries and Oceans Canada did not distinguish its responsibilities with regard to aquatic invasive species from those of the provinces and territories. Not knowing who should do what creates uncertainty about which jurisdiction should respond when new invasive species are detected. As well, the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations were not adequately enforced, partly because of the Department’s and the Agency’s shortcomings in equipping and training fishery officers and border services officers with the means to prevent aquatic invasive species from entering Canada.

Assessing the risks posed by aquatic invasive species

Fisheries and Oceans Canada did not systematically assess and monitor threats

1.24 We found that Fisheries and Oceans Canada did not determine which aquatic invasive species and pathways posed the greatest risks to Canada. The Department lacked a coherent process to identify which assessments were most needed, did not have a complete inventory of its risk assessments, and had no consistent way of reviewing the results to determine how to use them.

1.25 We also found that Fisheries and Oceans Canada did not systematically collect or maintain information to track aquatic invasive species or the extent of their spread.

1.26 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

- Identifying and assessing high-risk species and pathways

- Monitoring and tracking the presence and spread of aquatic invasive species

1.27 This finding matters because systematic risk assessment—biological risk assessmentDefinition vii and socio-economic risk assessmentDefinition viii—would let Fisheries and Oceans Canada know which aquatic species and pathways pose the greatest biological and socio-economic risks and are likely to cause the greatest amount of damage. The Department needs this information to determine which species it should monitor or regulate or which species it should urgently attempt to eradicate if they are discovered.

1.28 We conducted an audit of invasive species 17 years ago: the 2002 October Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Chapter 4—Invasive Species. We recommended that Fisheries and Oceans Canada develop a means to identify and assess the risks posed by aquatic invasive species and use it to set priorities and objectives.

1.29 We conducted another audit of Fisheries and Oceans Canada 11 years ago, also focusing on aquatic invasive species: the 2008 March Status Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Chapter 6—Ecosystems—Control of Aquatic Invasive Species. In response to our recommendations, the Department indicated that it was assessing the risks posed by existing and potential aquatic invasive species and pathways to guide program activities and provide a foundation for managing aquatic invasive species.

1.30 Our recommendations in these areas of examination appear at paragraphs 1.36 and 1.40.

1.31 What we examined. We examined whether Fisheries and Oceans Canada assessed biological and socio-economic risks to identify the most important aquatic invasive species and pathways to regulate. We also examined whether it monitored and tracked the presence and spread of the aquatic invasive species that were considered to pose the greatest risks.

1.32 Identifying and assessing high-risk species and pathways. Fisheries and Oceans Canada acknowledged the importance of doing biological and socio-economic risk assessments to understand the risks posed by the aquatic invasive species or pathways with a high potential to cause damage. However, we found that the Department lacked a coherent process to identify which assessments were needed. It therefore could not demonstrate that it had completed the assessments critical to identifying the species or pathways that posed the greatest risks and the nature of these risks. In addition, it had no reliable estimate of the number of aquatic invasive species that threaten Canada.

1.33 The Department undertook various types of biological risk assessment work. This work included a few detailed biological risk assessments (following a formal, peer-reviewed process), less detailed screening assessments, and studies to inform more in-depth work. However, we found that the Department was not consistently applying its screening assessment methods and had not determined when it should conduct which type of assessment. Furthermore, it did not have complete information on what assessments it had already done and had no consistent way of reviewing the results to determine what further action was necessary.

1.34 We found that the Department had not determined whether the assessments that it had completed were those that were most needed. It was able to provide us with detailed biological risk assessments for one species and three pathways that it had completed between 2014 and 2018. It also provided three socio-economic risk assessments for five species that it had completed during the same period. One of the reasons why the Department had completed few socio-economic assessments was that, according to its Socioeconomic Risk Assessment Guidelines for Aquatic Invasive Species, it could conduct them only if it had detailed information on a species’ biological risks.

1.35 With no way of knowing whether it had conducted the risk assessments that were most needed, the Department did not have a national view of the range, extent, or importance of the risks posed by aquatic invasive species or certain pathways.

1.36 Recommendation. Fisheries and Oceans Canada should develop and implement a coherent approach to determine which biological and socio-economic risk assessments are needed and conduct them.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response. Agreed. Fisheries and Oceans Canada is currently developing a systematic approach for determining which biological and socio-economic risk assessments should be conducted, and it will build on previously developed screening tools. Risk assessments will be undertaken based on capacity.

By 31 March 2021, Fisheries and Oceans Canada will develop a systematic approach to determine which biological and socio-economic risk assessments are needed.

1.37 Monitoring and tracking the presence and spread of aquatic invasive species. We found that without an overall view of the risks posed by invasive species, Fisheries and Oceans Canada could not make informed decisions at the national level about which species and pathways to monitor. It based its decisions about which species to monitor on discussions with regional stakeholders. It chose to focus on monitoring species that had already been sighted, with an emphasis on tunicate and Asian carp species, the zebra mussel, and the green crab. However, it did not know whether these were the species that most needed monitoring.

1.38 We found that despite its lead role in monitoring aquatic invasive species in Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada did not have adequate data that would provide it with an overall view of what invasive species had become established and where they were located in Canada. It did not have or contribute to a common database or platform that would allow it to track invasive species or the extent of their geographic spread. At the time of our audit, most of the Department’s regional offices contributed to multi-stakeholder databases that were not connected to each other. Department officials sometimes entered data into databases that only a few users could access.

1.39 Fisheries and Oceans Canada contributed to Environment and Climate Change Canada’s Newly Established Invasive Alien Species in Canada indicator. However, Fisheries and Oceans Canada was concerned that the indicator did not accurately reflect the full status of the aquatic invasive species affecting Canada. In 2017, this indicator reported that no new invasive species became established in Canada between 2012 and 2015. However, the indicator did not include data on species that were spreading within Canada or for which early eradication efforts were still being taken. We found that in spite of its concerns with the design and relevance of this indicator, Fisheries and Oceans Canada did not compile its own reliable information on the number of new aquatic invasive species established or their spread within Canada.

1.40 Recommendation. Fisheries and Oceans Canada should develop or coordinate a national database or platform that would allow the Department and stakeholders to track and share information about species introductions and spread. This information should help the Department make informed decisions about where to focus its resources for prevention and monitoring activities.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response. Agreed. Fisheries and Oceans Canada agrees to develop or coordinate a national data platform, which could inform the Department’s decision making for resource allocation and management activities.

In order to truly capture a national picture, Fisheries and Oceans Canada will have to rely on provinces, territories, and other partners and stakeholders to share or to freely allow access to their data and information, particularly for areas where the Department has not previously conducted research or monitoring.

By 31 March 2022, Fisheries and Oceans Canada will prepare and assess options for the creation of a data platform.

Preventing aquatic invasive species from becoming established

1.41 Over the past decade and a half, both the House of Commons Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans and the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development have issued reports finding that Fisheries and Oceans Canada did not act urgently enough to address the problems posed by aquatic invasive species. In its latest report, in 2013, the Committee called on the government to develop a framework and funding strategy to manage aquatic invasive species.

1.42 Until 2015, Canada had no national regulations for aquatic invasive species. Some provinces and territories had legislation, but the lack of a cohesive national approach left gaps in oversight. The 2015 Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations made it illegal to introduce, import, possess, transport, or release certain species. The Regulations include a list of 103 species and groups of species (covering about 174 species in total). Fisheries and Oceans Canada anticipated that, in the future, the addition or removal of species from this list would be informed by biological and socio-economic risk assessments.

1.43 Fisheries and Oceans Canada has said that implementing the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations was a cornerstone of its efforts to prevent the introduction and spread of aquatic invasive species. Funds to implement the Regulations started to become available to the Department in 2017. That year, the federal budget allocated $43.8 million to the Department over five years to prevent the introduction of aquatic invasive species, respond to the appearance of new species, and manage the spread of established species. The federal government also approved an ongoing budget of $10.8 million per year after the 2021–22 fiscal year. These amounts were in addition to the $4.1 million a year that the Department was already receiving to conduct scientific research and risk assessments, support regulatory development, and control sea lamprey. Significant portions of the Department’s new funding were earmarked for its Asian Carp Program and Sea Lamprey Control Program.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada lacked a strategic approach to prevent aquatic invasive species from entering and spreading within Canada

1.44 We found that when Fisheries and Oceans Canada developed the 2015 Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations, it did not always use science-based information to choose which species to regulate. By 2018, it had still not arrived at a process for choosing species to include when the Regulations are next revised.

1.45 We also found that Fisheries and Oceans Canada did not distinguish its regulatory responsibilities from those of the provinces and territories, including clarifying who was responsible for aquatic invasive freshwater plants.

1.46 At the time of our audit, the Department had developed draft work plans for its Aquatic Invasive Species National Core Program but had not finalized strategic directions for the program to guide its planning and resource allocation.

1.47 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

- Identifying aquatic invasive species to regulate

- Defining responsibilities

- Establishing strategic directions

1.48 This finding matters because to prevent aquatic invasive species from entering Canada, the first steps are knowing which species to regulate, how funding and staff will be allocated, and who is responsible for which tasks.

1.49 Our recommendations in these areas of examination appear at paragraphs 1.53, 1.56, and 1.59.

1.50 What we examined. We examined whether Fisheries and Oceans Canada

- used science-based information to choose which species to regulate,

- worked with provinces and territories to clearly define its responsibilities, and

- had established strategic directions to guide its prevention activities.

1.51 Identifying aquatic invasive species to regulate. We found that Fisheries and Oceans Canada did not determine priority invasive species and pathways to include in the 2015 Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations. The Department did not have a process relying on scientific information to identify species to regulate even though it recognized the importance of doing so.

1.52 The Regulations cover about 174 aquatic species. Yet the Department could demonstrate that it had assessed only the biological risks posed by 14% and the socio-economic risks posed by 5% of these species prior to developing the Regulations. By 2018, it had still not arrived at a process for choosing species to include when the Regulations are next revised.

1.53 Recommendation. Fisheries and Oceans Canada should develop and implement a science-based process to identify the species, pathways, or areas to include in the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response. Agreed. Fisheries and Oceans Canada will develop a listing process for adding new species under the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations. This will be done in close collaboration with provinces and territories through the National Aquatic Invasive Species Committee. The listing process will incorporate scientific information, including results from screening level, biological, and socio-economic risk analyses, as well as cost-benefit analyses required under Canada’s regulatory process.

By 31 March 2021, Fisheries and Oceans Canada will have a listing process ready for national endorsement by the provinces and territories.

1.54 Defining responsibilities. We found that Fisheries and Oceans Canada was unclear on whether its responsibilities for regulating aquatic invasive species included freshwater plants (Exhibit 1.3). The Department acknowledged that it might be responsible for regulating them, but we found that it had not yet reached a conclusion on this. The Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations were passed in 2015, but they listed no plant species.

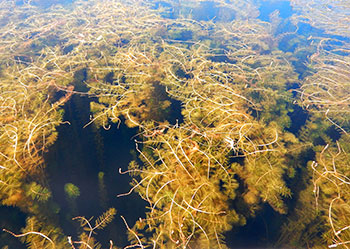

Exhibit 1.3—Case study: Eurasian water milfoil—Fisheries and Oceans Canada was not prepared for aquatic plant invasions

Eurasian water milfoil in Lac Gobeil, a lake in Quebec’s Côte-Nord (North Shore) region

Photo: Organisme des bassins versants de la Haute-Côte-Nord (the watershed organization of the Upper North Shore region)

Understanding the threat

The Eurasian water milfoil is an aquatic invasive plant of concern. It is already established in many provinces and is at risk of spreading to other parts of Canada. It can compete aggressively with native plants and reduce biological diversity and water quality. As it decomposes, it can lower oxygen levels in the water, killing fish. It also has a negative effect on human activities. It affects tourism by forming dense mats that restrict boating, swimming, and fishing. These mats also create stagnant water, an ideal habitat for mosquitoes.

Undefined responsibility for regulating plants

In 2014, Fisheries and Oceans Canada developed a protocol to assess the biological risks of aquatic plants. It used the protocol to identify more than 100 freshwater plant species, including the Eurasian water milfoil, as having the potential to pose high invasion risks. However, since the Department had not determined whether it was responsible for regulating freshwater plants, it was not in a position to prevent the Eurasian water milfoil’s introduction or spread.

1.55 We also found that, more generally, Fisheries and Oceans Canada had not formally articulated its roles and responsibilities for aquatic invasive species. The Department often viewed its role as preventing marine invasive species and expected the provinces to oversee freshwater invasive species. At the time of our audit, the Department sometimes disagreed with provinces about these responsibilities and was still negotiating to clarify them.

1.56 Recommendation. Fisheries and Oceans Canada should consult the provinces and territories to clarify roles and responsibilities for preventing the introduction and spread of aquatic invasive species, including freshwater plants.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response. Agreed. Fisheries and Oceans Canada will continue to meet regularly with provincial and territorial governments to discuss respective roles and responsibilities, including for freshwater invasive plants. For example, the Department is currently discussing a formal agreement with the Province of British Columbia regarding the management of freshwater and marine invasive species in that province. In New Brunswick, the Department has initiated discussions around roles and responsibilities for freshwater invasive species with the hope of establishing a formal agreement. Further, by collaborating with provinces and territories through the National Aquatic Invasive Species Committee, the Department has the opportunity to facilitate discussions and maintain strong working relationships.

While Fisheries and Oceans Canada is the lead for managing aquatic invasive species in Canada, it is a shared responsibility across numerous federal departments and agencies, including but not limited to Environment and Climate Change Canada, Parks Canada, Transport Canada, Health Canada’s Pest Management Regulatory Agency, National Defence, and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency.

By 31 March 2020, Fisheries and Oceans Canada will consult with provinces and territories to clarify respective roles and responsibilities, including with respect to freshwater plants.

1.57 Establishing strategic directions. We found that Fisheries and Oceans Canada was still establishing strategic directions for its new Aquatic Invasive Species National Core Program. At the time of our audit, the Department was working with other federal departments and jurisdictions to finalize joint work plans. However, we found that the Department had not yet determined which activities were most critical. Its program was not given a mandate for activities in Canada’s Arctic. The Department continued to focus its resources on the Great Lakes as it developed its program.

1.58 During our audit, Fisheries and Oceans Canada provided three-year funding to a third party to prevent zebra and quagga mussels from invading lakes and rivers in British Columbia. The Department did this even though it had not clarified responsibilities for freshwater aquatic invasive species with the Province of British Columbia. We found that the Department made decisions about allocating resources to prevent invasive species without having clarified responsibilities with provinces and without having established a strategic direction for its activities.

1.59 Recommendation. In consultation with the provinces, territories, and other partners, Fisheries and Oceans Canada should develop and communicate a strategy to guide its resource allocation decisions, so that it can prevent the establishment of aquatic invasive species.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response. Agreed. The Budget 2017 announcement to prevent the introduction and spread of aquatic invasive species provided some direction for resource allocation. Funding increases incrementally over five years and includes a total of 13 new program staff across the country and 7 new fishery officers to be deployed to the Central and Arctic region and to the Quebec region by the 2020–21 fiscal year. This aligns with the priority in the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard’s mandate letter to increase the protection of freshwater resources in the Great Lakes, St. Lawrence River, and Lake Winnipeg basins. However, as funding was significantly less than Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s identified needs, the Department will make risk-based decisions regarding the resources allocated to protect fish and fish habitat from aquatic invasive species.

As the implementation and enforcement of the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations is a responsibility shared by the federal and provincial governments, Fisheries and Oceans Canada will continue to engage provinces, territories, and other partners through the National Aquatic Invasive Species Committee and other appropriate means.

Informed by An Alien Invasive Species Strategy for Canada and A Canadian Action Plan to Address the Threat of Aquatic Invasive Species, Fisheries and Oceans Canada will draft a strategy to help guide resource allocation and present it to the National Aquatic Invasive Species Committee by 31 December 2019.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Canada Border Services Agency did not adequately enforce the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations

1.60 We found that Fisheries and Oceans Canada had done limited enforcement of the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations. We also found that it did not prevent contaminated boats from entering Canada at the key international border crossing points that we looked at in Manitoba and New Brunswick. We found that the Canada Border Services Agency’s intervention activities were ineffective in these provinces.

1.61 Fisheries and Oceans Canada did not develop the procedures, tools, and training that federal, provincial, and territorial enforcement officers needed to enforce the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations within Canada. In addition, neither the Department nor the Agency provided adequate support that border services officers needed to help prevent aquatic invasive species from crossing the border.

1.62 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

- No strategy and no dedicated staff for enforcement

- Insufficient procedures, tools, and training for enforcement

1.63 This finding matters because shortcomings at both Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Canada Border Services Agency may be allowing aquatic invasive species to enter Canada. If left uncorrected, management problems will only increase as more species are added to the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations.

1.64 Fisheries and Oceans Canada and provincial and territorial fishery officers and guardians have the power to enforce the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations. For example, an officer can decontaminate a boat carrying an aquatic invasive species or order the person transporting it to do so. The Regulations also allow an officer to direct a person to stop introducing any non-native species.

1.65 Border services officers with the Canada Border Services Agency are expected to refer anyone suspected of importing prohibited aquatic invasive species to provincial, territorial, or federal enforcement staff. Currently, four types of Asian carp species and two types of invasive mussels are prohibited. Asian carp are typically imported intentionally for food, whereas zebra and quagga mussels attach themselves to watercraft.

1.66 As mentioned earlier, the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations were passed in 2015. Additional funding to enforce them is scheduled to become available to Fisheries and Oceans Canada in 2019. The Canada Border Services Agency did not receive dedicated funding to help enforce the Regulations, and no additional funding is anticipated. It had one staff member at its national headquarters supporting its work to intercept aquatic invasive species, among other responsibilities.

1.67 Our recommendations in these areas of examination appear at paragraphs 1.73 and 1.76.

1.68 What we examined. We examined whether Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Canada Border Services Agency clearly delineated their mutual roles and responsibilities for enforcing the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations. This work included looking at federal enforcement of zebra and quagga mussel prohibitions at the international border in Manitoba and New Brunswick, where the environment was or could be suitable for invasions, where regional border traffic was high, and where there were indications of less activity to control the risks. We examined whether the Department and the Agency developed the procedures, tools, and training that federal, provincial, and territorial staff needed to enforce the Regulations effectively.

1.69 No strategy and no dedicated staff for enforcement. We found that Fisheries and Oceans Canada had no strategy for enforcing the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations and that its enforcement activities were limited. Its records showed that it had spent a limited amount of time verifying compliance with the Regulations. It had responded to only a single infraction since the Regulations were passed in 2015.

1.70 We also found that Fisheries and Oceans Canada did not assess the risk of commercial importers smuggling Asian carp into Canada intentionally by declaring they were importing another species. The Department also did not set targets on suspected imports or importers to check shipments and mitigate this risk.

1.71 We also found that Fisheries and Oceans Canada had no staff dedicated to enforcing the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations in all regions, although risks had been identified across all of them. For example, on Canada’s east and west coasts, there is a risk of green crab continuing to spread (Exhibit 1.4).

Exhibit 1.4—The invasive green crab is at risk of spreading farther along Canada’s east and west coasts

Invasive green crab found off the coast of Prince Edward Island

Photo: Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Green crab was first found in Atlantic Canadian waters in the 1950s. The species was found in Pacific Canadian waters in the 1990s. The invasive crab is at risk of spreading farther along both coasts. Green crab populations can expand rapidly and compete fiercely with other native species, such as lobster, for food. They have the potential to significantly affect biodiversity and habitat.

1.72 We found that the Canada Border Services Agency and Fisheries and Oceans Canada did not effectively prevent the entry of the zebra mussel into Canada at the international borders in Manitoba and New Brunswick (Exhibit 1.5).

Exhibit 1.5—Case study: Zebra mussel—This invasive species was not properly intercepted at certain international border points

Provincial staff using 60 degrees Celsius60ºC water to decontaminate a boat in Selkirk, Manitoba

Photo: Manitoba Government

Zebra mussel shells piled up on a beach in Manitoba

Photo: Canadian Broadcasting CorporationCBC News

Understanding the threat

The zebra mussel is thought to be one of the most destructive aquatic species ever to have invaded North American fresh waters, according to Fisheries and Oceans Canada. It estimates the economic impact of this mussel and its sister species, the quagga mussel, to be in the tens of millions of dollars annually in Canada.

The zebra mussel competes for food with native species. Its sharp shells litter recreational beaches and clog up infrastructure.

This species first arrived in the Great Lakes in the mid-1980s via water retained on boats. Since then, it has spread extensively around the Great Lakes basin, made its way into other watersheds across the United States, and in 2013, expanded into a few lakes in Manitoba. One way it did this was by attaching itself to trailered boats. Even when the zebra mussel is not visible, its larvae can survive in water retained on boats. Therefore, the Canada Border Services Agency defines a high-risk boat as any that has been in the water in the past 30 days where the mussel is known or suspected to live, or that is not clean, drained, dry, and free of bait.

Possible solutions

Preventing the spread of the zebra mussel is possible. International borders provide an opportunity for the Canada Border Services Agency to work with federal, provincial, or territorial enforcement authorities to stop the zebra mussel from spreading via boats transported over land. This risk can be reduced by ensuring that high-risk boats are properly decontaminated, quarantined, or refused entry.

Ineffective enforcement—or none at all

At the international border in Manitoba and New Brunswick, we found that Fisheries and Oceans Canada did not intervene to prevent potentially contaminated boats from entering Canada. This was partly because the Department had not distinguished its responsibilities from those of the provinces.

In these provinces, we also found that the Canada Border Services Agency’s interventions were ineffective.

Canada Border Services Agency officials told us that in Emerson, Manitoba—at the busiest highway crossing in the Prairies—they sometimes sent uncleaned boats back to American car washes before allowing the boats to re-enter Canada. But car washes are not an effective way to decontaminate boats, since the water temperatures are often not hot enough to kill the mussel.

In New Brunswick, Canada Border Services Agency officials told us they relied on visual cues to determine whether to refer a boat to an enforcement authority. Since the mussel can be too small to see, this was also an ineffective approach.

1.73 Recommendation. Fisheries and Oceans Canada should analyze and fill gaps in its enforcement of the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations, including

- developing and implementing a national strategy to enforce the Regulations, and

- working with the Canada Border Services Agency to address risks associated with watercraft and prohibited imports.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response. Agreed. Budget 2017 allocated $43.8 million over five years to prevent the introduction and spread of aquatic invasive species. Under this initiative, enforcement capacity will be increased by a total of seven new fishery officers (four in the 2019–20 fiscal year and three in the 2020–21 fiscal year). These officers will be deployed to the Central and Arctic region and to the Quebec region in a manner that aligns with the priority in the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard’s mandate letter to increase the protection of freshwater resources in the Great Lakes, St. Lawrence River, and Lake Winnipeg basins. To ensure the efficient use of these limited resources, Fisheries and Oceans Canada will develop a strategy for verifying compliance and enforcing the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada will continue to work with the Canada Border Services Agency and through the National Aquatic Invasive Species Committee.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada will draft a national enforcement strategy by 30 September 2019.

1.74 Insufficient procedures, tools, and training for enforcement. We found that within Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada did not develop the procedures, tools, and training that federal, provincial, and territorial enforcement staff needed. The Department distributed general training material on the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations to its enforcement staff but had not yet developed more targeted material for all enforcement audiences.

1.75 We also found that at international borders, Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Canada Border Services Agency developed procedures for border services officers to help enforce the Regulations. However, we found that these did not provide adequate support. For example, the organizations did not

- clearly explain that the officers were expected to refer suspected cases of aquatic invasive species to enforcement staff;

- explain whether border services officers should detain, admit, or refuse entry of high-risk boats when enforcement staff could not act within a set time frame;

- develop sufficient tools to help border services officers detect prohibited aquatic invasive species; or

- provide training material to border services officers who were likely to encounter prohibited species.

1.76 Recommendation. Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Canada Border Services Agency should develop and implement the procedures, tools, and training that border services officers need to assist in enforcing the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations. The Department should also do this for fishery officers and fishery guardians.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Canada Border Services Agency’s response. Agreed. Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Canada Border Services Agency will work collaboratively to continue to develop and implement tools to support fishery and border services officers in enforcing the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada provided training to its fishery officers when the Regulations came into force in 2015. Additional information was further provided as part of the officers’ annual training. The Department is developing enhanced training on the Regulations for border services officers and will also develop procedures, tools, and training for its fishery officers by 31 March 2020.

The Canada Border Services Agency, with input and support from Fisheries and Oceans Canada, will update key existing training to ensure that border services officers are provided with key information on aquatic invasive species and to reinforce their understanding of procedures and expectations to enforce the Regulations at the international borders. These tools will incorporate and reflect border services officers’ new and broader mandate to enforce aquatic invasive species through legislation such as the Plant Protection Act and Regulations and the Health of Animals Act and Regulations. These activities will be completed by 31 March 2020.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada did not respond rapidly to known threats

1.77 We found that Fisheries and Oceans Canada was not ready to act in a timely manner when new aquatic invasive species were detected. Since putting in place a framework for developing rapid response plans in 2011, the Department developed and implemented only one formal plan: for four species of Asian carp in 2018. The Department’s responses to sightings of some other species were planned and undertaken only after the sightings.

1.78 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topic:

1.79 This finding matters because there is often only a small window of time to successfully eradicate a newly introduced or detected species. Once a species becomes established, it is generally much costlier to control its spread and manage its impacts.

1.80 In the context of invasive species, rapid response refers to the capacity to respond in a timely manner when a suspected species is detected to prevent it from becoming established or control its spread. Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s 2011 Canadian Rapid Response Framework for Aquatic Invasive Species underlines the need for planning, so that organizations are ready to respond.

1.81 Fisheries and Oceans Canada has the regulatory authority to prevent the introduction and spread of any aquatic invasive species by controlling, eradicating, treating, or destroying it.

1.82 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 1.88.

1.83 What we examined. We examined whether Fisheries and Oceans Canada developed and implemented response plans to prevent detected species from becoming established.

1.84 Developing and implementing response plans. We found that Fisheries and Oceans Canada had undertaken limited work to develop and implement response plans. This was despite a prior Auditor General’s recommendation and international commitments to do such work over the years. In the 2008 March Status Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Chapter 6—Ecosystems—Control of Aquatic Invasive Species, we recommended that Fisheries and Oceans Canada apply a systematic, risk-based approach to early detection and develop the ability to respond when new invasive species were detected. However, in our current audit, we found that the Department had not developed any response plans for pathways and was still in the process of developing several regional response plans.

1.85 The Department had created only one formal species-level response plan. This plan covered four species of Asian carp (Exhibit 1.6). Department officials told us that the Department planned to use the Asian carp response plan as a model for responding to other aquatic invasive species across Canada.

Exhibit 1.6—Case study: Asian carp—Fisheries and Oceans Canada had a response plan for one group of species

Response plans are a critical tool for timely action to prevent aquatic invasive species from becoming established. To date, Fisheries and Oceans Canada has created such a plan, covering only Asian carp species, of which there are four.

Grass carp that Fisheries and Oceans Canada captured and removed from Lake Gibson, Ontario, in 2016

Photo: Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Asian carp jumping out of the water

Photo: Sergey Yeromenko/Shutterstock.com

Understanding the threat

Four species of Asian carp (grass, bighead, silver, and black) have become established in the Mississippi River system. In the Great Lakes, there have been isolated sightings of Asian carp species since 1985.

In its 2004 biological risk assessment, Fisheries and Oceans Canada found that Asian carp species posed a high risk of becoming established in Canadian waters. Where they have become established in the United States, they have devastated native species by competing for food and destroying habitat.

According to Fisheries and Oceans Canada, the total economic value of activities that could be affected by an Asian carp invasion in the Great Lakes is $8.5 billion a year. These activities include

- commercial fishing,

- recreational fishing,

- recreational boating,

- wildlife viewing, and

- beach and lakefront use.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s contribution

To prepare to respond to future sightings of Asian carp, the Department began developing rapid response plans with partners, such as the Province of Ontario and the United States, starting in 2011.

When the Department received funding to put its own Asian Carp Program in place in 2012, it developed monitoring and response techniques and guidance that it shared with the other governments and non-government organizations working to prevent Asian carp species from becoming established. Activities included

- systematic monitoring of high-risk sites to detect the presence of Asian carp; and

- rapid responses to eradicate the few that were found, to keep them from multiplying.

In 2018, the Department developed its own strategic plan to respond to the detection of Asian carp in Canadian waters. This included a decision-making structure for determining what actions the Department should take depending on the circumstances. This also included an incident command system developed by the Department that set out participants’ roles, with clear procedures and instructions that participants can follow in the event of a sighting.

The results

Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response efforts have so far contributed to preventing Asian carp species from becoming established in Canada.

Experts still expect these species to become established in the next decade or two if nothing more is done. However, Department officials told us that delaying the species’ establishment would allow more time for governments to develop strategies and tools to manage and control them and would defer damaging and costly impacts.

1.86 Department officials told us that in the meantime, they responded to threats in an ad hoc manner, deciding what actions to take after reported sightings of a new species. We found that this response style could be slow. Delayed response times can allow a species to spread further, making it costlier and more troublesome to control or eradicate.

1.87 For example, green crab sightings were first reported in 1951 in the Bay of Fundy (New Brunswick). The Department did not develop a response plan to address it, and the crab continued to spread along Canada’s Atlantic coast. When it was reported off the Island of Newfoundland in 2007, the Department had no response plan ready and took no action for almost a year while it worked with stakeholders to decide how to respond. It started trapping green crab the following year but was not successful in eradicating the species. Green crab is now established in this area.

1.88 Recommendation. Fisheries and Oceans Canada should develop response plans for species that have a high risk of becoming established and causing environmental or economic impacts, or for areas where there is a high risk of this occurring.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response. Agreed. Early detection and response are critical for preventing the establishment and spread of aquatic invasive species in Canadian waters. Fisheries and Oceans Canada has identified the development of response plans for high-risk species and areas as a priority.

The Department will review and build upon the science-based Canadian Rapid Response Framework for Aquatic Invasive Species (2011) to develop a national response strategy to guide regional plans. In accordance with these frameworks and informed by ongoing monitoring and early detection activities, each region will develop response plans adapted to its respective high-risk species or areas, which is critical for responding effectively to emergency situations. The successes of the Asian Carp Program and the development and implementation of the Department’s Strategic Response Plan will inform the development of response plans in other regions.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada will draft a national response strategy by 31 December 2019.

Conclusion

1.89 We concluded that Fisheries and Oceans Canada, as the lead on aquatic invasive species for the federal government, did not implement adequate measures to prevent invasive species from becoming established in Canadian waters.

1.90 In addition, we concluded that the Canada Border Services Agency did not implement adequate measures to help enforce the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations at international borders.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on aquatic invasive species. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs, and to conclude on whether the management of aquatic invasive species complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard for Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office applies Canadian Standard on Quality Control 1 and, accordingly, maintains a comprehensive system of quality control, including documented policies and procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we have complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit;

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit;

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided; and

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate.

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Canada Border Services Agency implemented adequate measures to prevent invasive species from becoming established in Canadian waters.

The measures we examined were those covered by the audit criteria.

Scope and approach

The audit focused on the federal oversight of aquatic invasive species under the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations. This focus covered the work by the two federal organizations to prevent the introduction and spread of aquatic invasive species (including early detection and response), but not their work to control invasive species once established. We examined the performance of the federal organizations with the understanding that they deliver certain programs in collaboration with other partners, including provinces and territories.

We gathered evidence through document review, interviews with federal officials and third-party stakeholders, system and process walk-throughs, file review, and site visits to selected research facilities and a border crossing. The audit included case studies in which more in-depth audit work was conducted. This included enforcement of zebra and quagga mussel prohibitions in Manitoba and New Brunswick, where inherent risks were high or uncertain and there were indications that the mussels were not well controlled. It also included response efforts for Asian carp species in Ontario.

We considered the contributions of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (assisted by the Canada Border Services Agency) to meeting two international commitments:

- By 2020, introduce measures to prevent the introduction and significantly reduce the impact of invasive alien species on land and water ecosystems and control or eradicate the priority species (United Nations’ sustainable development target 15.8); and

- By 2020, invasive alien species and pathways are identified and prioritized, priority species are controlled or eradicated, and measures are in place to manage pathways to prevent their introduction and establishment (United Nations’ Convention on Biological Diversity, Aichi Biodiversity Target 9).

In doing so, this audit contributed to Canada’s actions in relation to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 16, which is to “promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels.”

We did not examine the federal government’s activities to assess and approve intentionally introduced species through the National Code on Introductions and Transfers of Aquatic Organisms. Nor did we examine other federal departments’ and agencies’ contributions to preventing the introduction of aquatic invasive species. We did not include Transport Canada because our initial analysis when planning the audit indicated that it had introduced measures to control the risks of species invasions in the Great Lakes (an important invasion pathway). Other federal organizations that work in this area include Environment and Climate Change Canada, Parks Canada, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, and Health Canada’s Pest Management Regulatory Agency.

Criteria

To determine whether Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Canada Border Services Agency implemented adequate measures to prevent invasive species from becoming established in Canadian waters, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Fisheries and Oceans Canada

|

|

|

Fisheries and Oceans Canada implements the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations and provides the tools and support necessary for its partners (the Canada Border Services Agency, provinces, and territories) to contribute to enforcing them. |

|

|

The Canada Border Services Agency carries out its responsibilities for implementing the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations. |

|

|

Fisheries and Oceans Canada develops early detection and rapid response protocols where priority threats exist and achieves expected results. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period between 1 January 2014, when the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations were being developed, and 6 December 2018. However, the audit period for the Asian carp case study began on 1 January 2012. These are the periods to which the audit conclusion applies. To gain a more complete understanding of the subject matter of the audit, we also examined certain matters that preceded the starting dates of these periods.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 28 December 2018, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

Principal: Kimberley Leach

Director: Erin Windatt

Alexandra Elias-Kapoor

Leslie Lapp

Mark Lawrence

Kyla Tanner

Genna Woolston

List of Recommendations

The following table lists the recommendations and responses found in this report. The paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report, and the numbers in parentheses indicate the location of the related discussion.

Assessing the risks posed by aquatic invasive species

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

1.36 Fisheries and Oceans Canada should develop and implement a coherent approach to determine which biological and socio-economic risk assessments are needed and conduct them. (1.32 to 1.35) |

Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response. Agreed. Fisheries and Oceans Canada is currently developing a systematic approach for determining which biological and socio-economic risk assessments should be conducted, and it will build on previously developed screening tools. Risk assessments will be undertaken based on capacity. By 31 March 2021, Fisheries and Oceans Canada will develop a systematic approach to determine which biological and socio-economic risk assessments are needed. |

|

1.40 Fisheries and Oceans Canada should develop or coordinate a national database or platform that would allow the Department and stakeholders to track and share information about species introductions and spread. This information should help the Department make informed decisions about where to focus its resources for prevention and monitoring activities. (1.37 to 1.39) |

Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response. Agreed. Fisheries and Oceans Canada agrees to develop or coordinate a national data platform, which could inform the Department’s decision making for resource allocation and management activities. In order to truly capture a national picture, Fisheries and Oceans Canada will have to rely on provinces, territories, and other partners and stakeholders to share or to freely allow access to their data and information, particularly for areas where the Department has not previously conducted research or monitoring. By 31 March 2022, Fisheries and Oceans Canada will prepare and assess options for the creation of a data platform. |

Preventing aquatic invasive species from becoming established

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

1.53 Fisheries and Oceans Canada should develop and implement a science-based process to identify the species, pathways, or areas to include in the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations. (1.51 to 1.52) |

Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response. Agreed. Fisheries and Oceans Canada will develop a listing process for adding new species under the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations. This will be done in close collaboration with provinces and territories through the National Aquatic Invasive Species Committee. The listing process will incorporate scientific information, including results from screening level, biological, and socio-economic risk analyses, as well as cost-benefit analyses required under Canada’s regulatory process. By 31 March 2021, Fisheries and Oceans Canada will have a listing process ready for national endorsement by the provinces and territories. |

|

1.56 Fisheries and Oceans Canada should consult the provinces and territories to clarify roles and responsibilities for preventing the introduction and spread of aquatic invasive species, including freshwater plants. (1.54 to 1.55) |

Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response. Agreed. Fisheries and Oceans Canada will continue to meet regularly with provincial and territorial governments to discuss respective roles and responsibilities, including for freshwater invasive plants. For example, the Department is currently discussing a formal agreement with the Province of British Columbia regarding the management of freshwater and marine invasive species in that province. In New Brunswick, the Department has initiated discussions around roles and responsibilities for freshwater invasive species with the hope of establishing a formal agreement. Further, by collaborating with provinces and territories through the National Aquatic Invasive Species Committee, the Department has the opportunity to facilitate discussions and maintain strong working relationships. While Fisheries and Oceans Canada is the lead for managing aquatic invasive species in Canada, it is a shared responsibility across numerous federal departments and agencies, including but not limited to Environment and Climate Change Canada, Parks Canada, Transport Canada, Health Canada’s Pest Management Regulatory Agency, National Defence, and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency. By 31 March 2020, Fisheries and Oceans Canada will consult with provinces and territories to clarify respective roles and responsibilities, including with respect to freshwater plants. |

|

1.59 In consultation with the provinces, territories, and other partners, Fisheries and Oceans Canada should develop and communicate a strategy to guide its resource allocation decisions, so that it can prevent the establishment of aquatic invasive species. (1.57 to 1.58) |

Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response. Agreed. The Budget 2017 announcement to prevent the introduction and spread of aquatic invasive species provided some direction for resource allocation. Funding increases incrementally over five years and includes a total of 13 new program staff across the country and 7 new fishery officers to be deployed to the Central and Arctic region and to the Quebec region by the 2020–21 fiscal year. This aligns with the priority in the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard’s mandate letter to increase the protection of freshwater resources in the Great Lakes, St. Lawrence River, and Lake Winnipeg basins. However, as funding was significantly less than Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s identified needs, the Department will make risk-based decisions regarding the resources allocated to protect fish and fish habitat from aquatic invasive species. As the implementation and enforcement of the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations is a responsibility shared by the federal and provincial governments, Fisheries and Oceans Canada will continue to engage provinces, territories, and other partners through the National Aquatic Invasive Species Committee and other appropriate means. Informed by An Alien Invasive Species Strategy for Canada and A Canadian Action Plan to Address the Threat of Aquatic Invasive Species, Fisheries and Oceans Canada will draft a strategy to help guide resource allocation and present it to the National Aquatic Invasive Species Committee by 31 December 2019. |

|

1.73 Fisheries and Oceans Canada should analyze and fill gaps in its enforcement of the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations, including

|

Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response. Agreed. Budget 2017 allocated $43.8 million over five years to prevent the introduction and spread of aquatic invasive species. Under this initiative, enforcement capacity will be increased by a total of seven new fishery officers (four in the 2019–20 fiscal year and three in the 2020–21 fiscal year). These officers will be deployed to the Central and Arctic region and to the Quebec region in a manner that aligns with the priority in the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard’s mandate letter to increase the protection of freshwater resources in the Great Lakes, St. Lawrence River, and Lake Winnipeg basins. To ensure the efficient use of these limited resources, Fisheries and Oceans Canada will develop a strategy for verifying compliance and enforcing the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations. Fisheries and Oceans Canada will continue to work with the Canada Border Services Agency and through the National Aquatic Invasive Species Committee. Fisheries and Oceans Canada will draft a national enforcement strategy by 30 September 2019. |

|

1.76 Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Canada Border Services Agency should develop and implement the procedures, tools, and training that border services officers need to assist in enforcing the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations. The Department should also do this for fishery officers and fishery guardians. (1.74 to 1.75) |

Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Canada Border Services Agency’s response. Agreed. Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Canada Border Services Agency will work collaboratively to continue to develop and implement tools to support fishery and border services officers in enforcing the Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations. Fisheries and Oceans Canada provided training to its fishery officers when the Regulations came into force in 2015. Additional information was further provided as part of the officers’ annual training. The Department is developing enhanced training on the Regulations for border services officers and will also develop procedures, tools, and training for its fishery officers by 31 March 2020. The Canada Border Services Agency, with input and support from Fisheries and Oceans Canada, will update key existing training to ensure that border services officers are provided with key information on aquatic invasive species and to reinforce their understanding of procedures and expectations to enforce the Regulations at the international borders. These tools will incorporate and reflect border services officers’ new and broader mandate to enforce aquatic invasive species through legislation such as the Plant Protection Act and Regulations and the Health of Animals Act and Regulations. These activities will be completed by 31 March 2020. |

|

1.88 Fisheries and Oceans Canada should develop response plans for species that have a high risk of becoming established and causing environmental or economic impacts, or for areas where there is a high risk of this occurring. (1.84 to 1.87) |

Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response. Agreed. Early detection and response are critical for preventing the establishment and spread of aquatic invasive species in Canadian waters. Fisheries and Oceans Canada has identified the development of response plans for high-risk species and areas as a priority. The Department will review and build upon the science-based Canadian Rapid Response Framework for Aquatic Invasive Species (2011) to develop a national response strategy to guide regional plans. In accordance with these frameworks and informed by ongoing monitoring and early detection activities, each region will develop response plans adapted to its respective high-risk species or areas, which is critical for responding effectively to emergency situations. The successes of the Asian Carp Program and the development and implementation of the Department’s Strategic Response Plan will inform the development of response plans in other regions. Fisheries and Oceans Canada will draft a national response strategy by 31 December 2019. |