2024 Reports 1 to 5 of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the Parliament of Canada

Report 1—Contaminated Sites in the North

At a Glance

Contaminated sites represent significant environmental and human health risks and cost Canadians billions of dollars. Contaminated sites in northern Canada have not been managed to reduce the financial liability under the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan and the Northern Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program. Although work was undertaken to remediate contaminated sites, the total financial liability for federal contaminated sites is now over $10 billion. In addition, gaps remained in practices intended to reduce the risks to the environment and human health for current and future generations.

We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada, with the support of the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, did not effectively lead the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan. Transport Canada and Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, which manage contaminated sites in the North, complied with the program, but we found this was not enough for the program to meet its Canada‑wide objectives. For example, the cost for remediating contaminated sites keeps increasing for Canadians. Also, the program did not appropriately support custodians by including climate change and reconciliation with Indigenous peoples in remediation efforts, which are key priorities related to the management of contaminated sites.

Complex sites that require ongoing care and maintenance—such as the large abandoned Faro and Giant mines—present immediate and long-term risks to the environment and health of Canadians. For example, the Faro Mine requires ongoing maintenance for the foreseeable future to prevent contaminated water from polluting surrounding areas, and the Giant Mine requires a large volume of arsenic to remain frozen underground. The cost to remediate the 8 largest abandoned mines in the North has increased by 95% since 2019 due to several factors, including more accurate estimates to reflect the scope of work required to address these sites. As the responsible organization managing these mines, Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada had gaps in its approach for considering climate change adaptation and perpetual care plans.

As these sites often stand on Indigenous land, the remediation of contaminated sites in the North provides a significant opportunity to support reconciliation with Indigenous peoples and promote economic development. We heard from some Indigenous communities that these opportunities have yet to be realized.

Key facts and findings

- There were more than 24,000 contaminated sites across Canada, and more than 2,600 were in northern Canada. Of the more than 24,000 sites, 18,110 were closed, including 8,639 where no action was required.

- While only 11% of the total number of federal sites are in the North, over 60% of Canada’s total estimated financial liability is for the remediation of sites in the North.

- Although progress has been made in closing contaminated sites, the total financial liability for known contaminated sites had increased from $2.9 billion in 2004–05 to $10.1 billion in 2022–23.

- The Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan does not include realistic targets for climate adaptation and is missing targets for Indigenous engagement and socio-economic benefits to support reconciliation with Indigenous peoples—key priorities related to the management of contaminated sites.

- The lack of reporting and meaningful information on contaminated sites, including large abandoned mines, means that the Government of Canada, decision makers, and Canadians do not have a clear picture of the environmental and financial effects of these contaminated sites.

Why we did this audit

- Exposure to hazardous substances has been linked to adverse health conditions for humans. Left unaddressed, the environmental and human health risks, and the associated liabilities, could increase if contaminants move, especially if they spread beyond federal property boundaries.

- The costs to remediate federal contaminated sites are a burden to current and future generations of Canadian taxpayers.

- Meaningful engagement and socio-economic benefits supporting reconciliation with Indigenous peoples and the consideration of climate change are integral to assessing and addressing environmental and human health risks—which are significant for people who live near contaminated sites.

- Canadians need to understand the state of contaminated sites, including their environmental and financial effects.

Highlights of our recommendations

- To achieve the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan’s objective of reducing the financial liability, Environment and Climate Change Canada, working with program partners, should support custodians in reducing financial liability.

- To achieve the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan’s objective of reducing the environmental and human health risks, Environment and Climate Change Canada, working with program partners, should directly measure environmental and human health risk reduction, improve quality assessment and quality control for key program elements and develop a consistent approach for custodians to document and report on key program priorities.

- To improve its management of large abandoned mines in the North under the Northern Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program, Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada should enhance the reliability of the liability estimates and reduce environmental risks and improve transparency for current and future generations.

Please see the full report to read our complete findings, analysis, recommendations and the audited organizations’ responses.

As part of our audit, we examined the departments’ actions to support several United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, such as Goal 3 (Good Health and Well‑Being), Goal 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation), and Goal 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), along with selected associated targets. We found that Environment and Climate Change Canada, Transport Canada, and Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada aligned their site management or remediation activities with some of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal targets through their departmental sustainable development strategies. However, they did not track progress toward meeting United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal targets specifically.

Visit our Sustainable Development page to learn more about sustainable development and the Office of the Auditor General of CanadaOAG.

Exhibit highlights

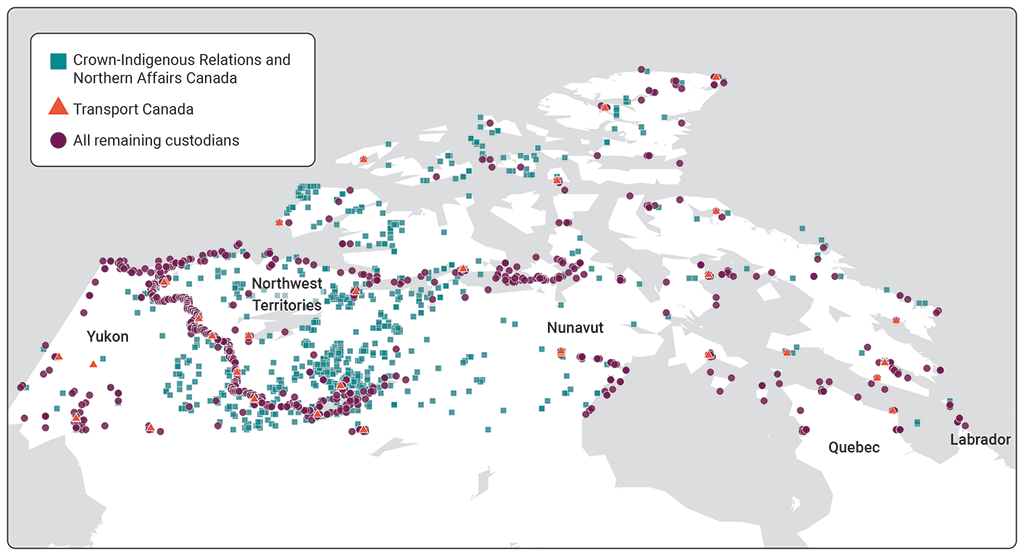

Federally managed contaminated sites in northern Canada

Note: The map includes all federal contaminated sites in the North, including active, closed, and suspected sites. The map is not proportional.

Source: Adapted from data provided by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

Text version

This map includes all federal contaminated sites in the North, including active, closed, and suspected sites. It indicates the sites that are managed by Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, by Transport Canada, and by all other custodians. In total, there are 2,567 sites.

Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada manages 1,003 contaminated sites in North. Although they are spread out across the 3 territories, most of these sites are located in the Northwest Territories and in the western part of Nunavut.

Transport Canada manages 131 sites, which are spread out across the North.

The remaining 1,433 sites, which are managed by all remaining custodians, are also spread out across the North, with most in Nunavut and in the Northwest Territories. Many of them are close to the water, such as along the northern coast.

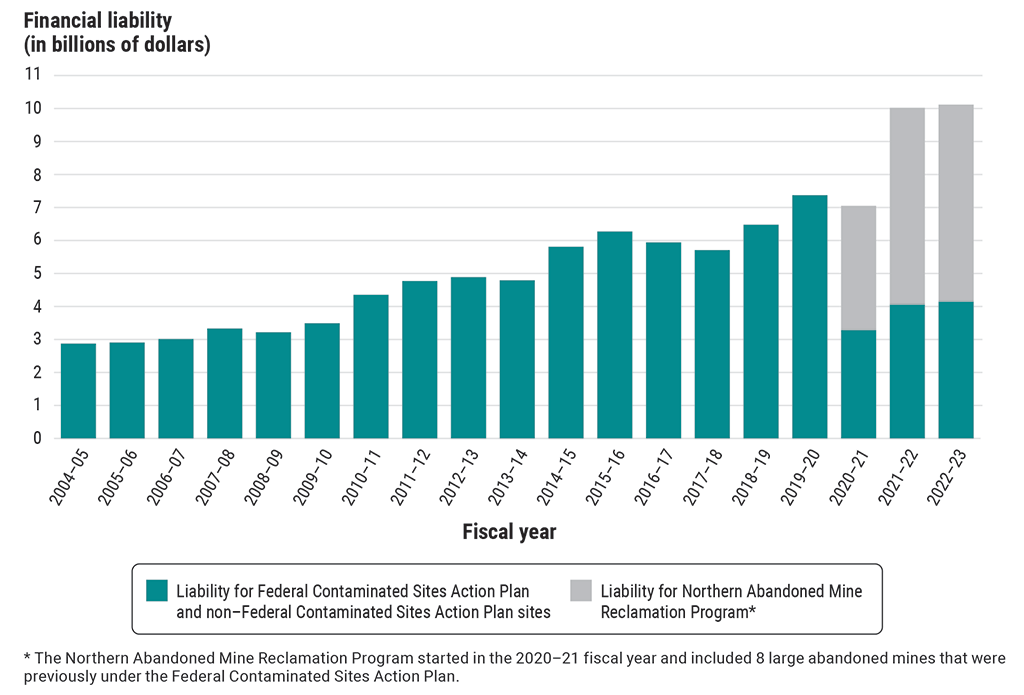

Canada’s financial liability for contaminated sites had increased since 2005, notwithstanding progress made in closing sites

Source: Adapted from data reported by the Public Accounts of Canada

Text version

Adapted from data reported by the Public Accounts of Canada, the graph shows the financial liability for contaminated sites for each fiscal year. The liability steadily increased during the period.

In 2004–05, the liability for Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan and non–Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan sites was $2.87 billion.

In 2005–06, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $2.91 billion.

In 2006–07, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $3.01 billion.

In 2007–08, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $3.33 billion.

In 2008–09, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $3.22 billion.

In 2009–10, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $3.49 billion.

In 2010–11, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $4.35 billion.

In 2011–12, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $4.77 billion.

In 2012–13, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $4.89 billion.

In 2013–14, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $4.80 billion.

In 2014–15, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $5.81 billion.

In 2015–16, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $6.27 billion.

In 2016–17, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $5.94 billion.

In 2017–18, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $5.71 billion.

In 2018–19, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $6.48 billion.

In 2019–20, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $7.38 billion.

In the 2020–21 fiscal year, the Northern Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program started and included 8 large abandoned mines that were previously under the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan. In 2020–21, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $3.28 billion and the liability for the program was $3.77 billion.

In 2021–22, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $4.06 billion and the liability for the program was $5.97 billion.

In 2022–23, the liability for plan and non‑plan sites was $4.15 billion and the liability for the program was $5.97 billion.

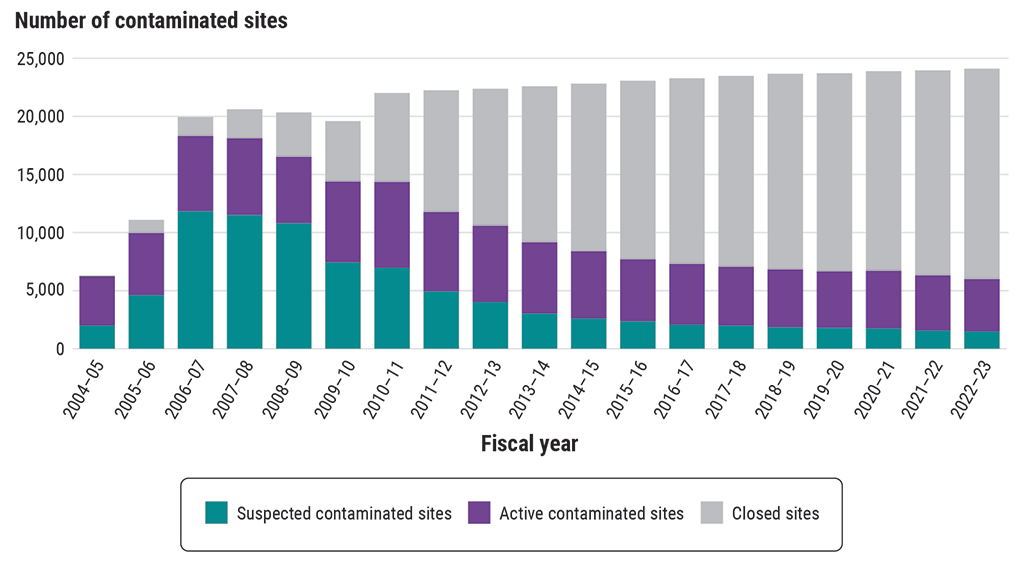

Source: Data provided by Environment and Climate Change Canada

Note: The liability for the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan and non–Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan sites can include sites that may have conducted activities using non–Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan funding. This is due to the limitations of the Federal Contaminated Sites Inventory with respect to categorizing sites by program (see paragraph 1.53).

Text version

Using data provided by Environment and Climate Change Canada, the graph shows the number of contaminated sites for the 2004–05 to 2022–23 fiscal years, broken into the following categories: suspected contaminated sites, active contaminated sites, and closed sites. The number of closed sites increased during the period.

In 2004–05, there were 6,200 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 2,000 suspected contaminated sites, 4,200 active sites, and 0 closed sites.

In 2005–06, there were 11,090 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 4,609 suspected contaminated sites, 5,352 active sites, and 1,129 closed sites.

In 2006–07, there were 19,947 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 11,841 suspected contaminated sites, 6,476 active sites, and 1,630 closed sites.

In 2007–08, there were 20,616 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 11,510 suspected contaminated sites, 6,601 active sites, and 2,505 closed sites.

In 2008–09, there were 20,344 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 10,809 suspected contaminated sites, 5,710 active sites, and 3,825 closed sites.

In 2009–10, there were 19,598 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 7,434 suspected contaminated sites, 6,949 active sites, and 5,215 closed sites.

In 2010–11, there were 22,017 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 6,958 suspected contaminated sites, 7,399 active sites, and 7,660 closed sites.

In 2011–12, there were 22,254 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 4,929 suspected contaminated sites, 6,845 active sites, and 10,480 closed sites.

In 2012–13, there were 22,382 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 4,014 suspected contaminated sites, 6,568 active sites, and 11,800 closed sites.

In 2013–14, there were 22,591 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 3,020 suspected contaminated sites, 6,144 active sites, and 13,427 closed sites.

In 2014–15, there were 22,820 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 2,606 suspected contaminated sites, 5,785 active sites, and 14,429 closed sites.

In 2015–16, there were 23,074 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 2,353 suspected contaminated sites, 5,340 active sites, and 15,381 closed sites.

In 2016–17, there were 23,279 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 2,060 suspected contaminated sites, 5,239 active sites, and 15,980 closed sites.

In 2017–18, there were 23,490 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 1,987 suspected contaminated sites, 5,067 active sites, and 16,436 closed sites.

In 2018–19, there were 23,667 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 1,842 suspected contaminated sites, 4,980 active sites, and 16,845 closed sites.

In 2019–20, there were 23,714 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 1,795 suspected contaminated sites, 4,860 active sites, and 17,059 closed sites.

In 2020–21, there were 23,897 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 1,738 suspected contaminated sites, 4,967 active sites, and 17,192 closed sites.

In 2021–22, there were 23,965 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 1,552 suspected contaminated sites, 4,762 active sites, and 17,651 closed sites.

In 2022–23, there were 24,109 contaminated sites in total, which consisted of 1,496 suspected contaminated sites, 4,503 active sites, and 18,110 closed sites.

Giant Mine costs rose significantly, and remediation work was not expected to be completed until 3 decades after it was abandoned

Shipping containers filled with contaminants located at the site of the Giant Mine in the Northwest Territories

Photo: Angela Gzowski, Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada

The Giant Mine is a former gold mine located outside of Yellowknife, in the Northwest Territories. It operated from 1948 to 2004 and was abandoned in 2005. The main environmental concern is the 237,000 tonnes (enough toxic waste to fill seven 11‑storey buildings) of highly toxic arsenic on the site.

The federal government has spent nearly 20 years assessing the site, developing a remediation plan, and conducting consultation and engagement activities. Urgent remediation work was completed during this period to reduce risks to the environment and human health. Remediation officially began in 2021 and is expected to be completed in 2038, 33 years after the mine was abandoned. The site will then require maintenance and monitoring in perpetuity.

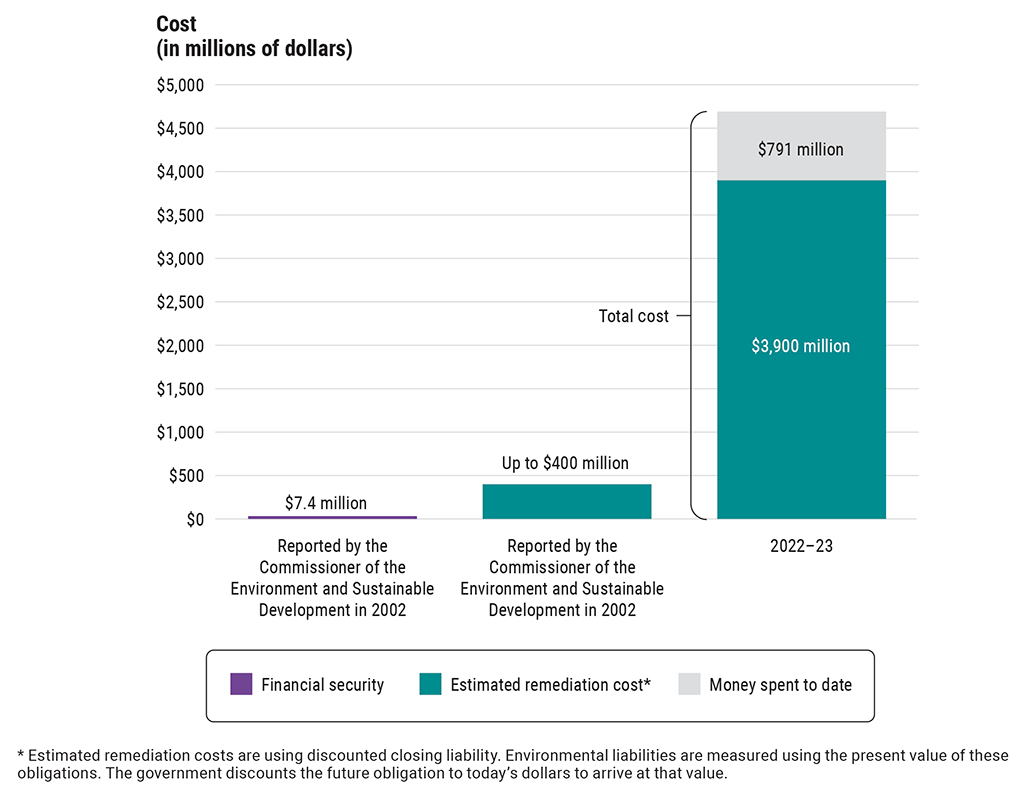

The estimated remediation cost for the mine has greatly increased since our 2002 audit, and the total cost to Canadians is much higher.

Source: Adapted from data in the 2002 Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the House of Commons, Chapter 3—Abandoned Mines in the North; and the Federal Contaminated Sites Inventory

Text version

This bar chart compares the estimated remediation costs for the Giant Mine as reported by the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development in 2002 with the estimated costs in the 2022–23 fiscal year.

In 2002, the Commissioner reported that the mine’s financial security was $7.4 million and the estimated remediation cost was up to $400 million. In 2022–23, the estimated remediation cost increased to $3.9 billion with an additional $791 million of money spent to date.

Estimated remediation costs are using discounted closing liability. Environmental liabilities are measured using the present value of these obligations. The government discounts the future obligation to today’s dollars to arrive at that value.

Faro Mine costs increased significantly, though the remediation phase had not yet started

Site of the Faro Mine in the Northwest Territories

Photo: Daphne Pelletier Vernier, Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada

The Faro Mine was once one of the largest open‑pit lead‑zinc mines in the world. It began operating in 1969 and was abandoned in 1998. Canada assumed responsibility for the management of the site in 2018. The main environmental problems are mining waste—enough to cover over 26,000 football fields, 1 metre deep—and 3 open pits filled with contaminated water.

At the time of our 2002 audit, the Faro Mine was being assessed. Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada had since consulted and engaged with Indigenous communities, conducted urgent remediation work, and submitted the remediation project’s proposal to the Yukon Environmental and Socio-economic Assessment Board in 2019 for review. Once designs and regulatory approvals are in place, the remediation of the mine is expected to take 15 years, followed by another 20 to 25 years of testing and monitoring. The site will then require maintenance and monitoring in perpetuity.

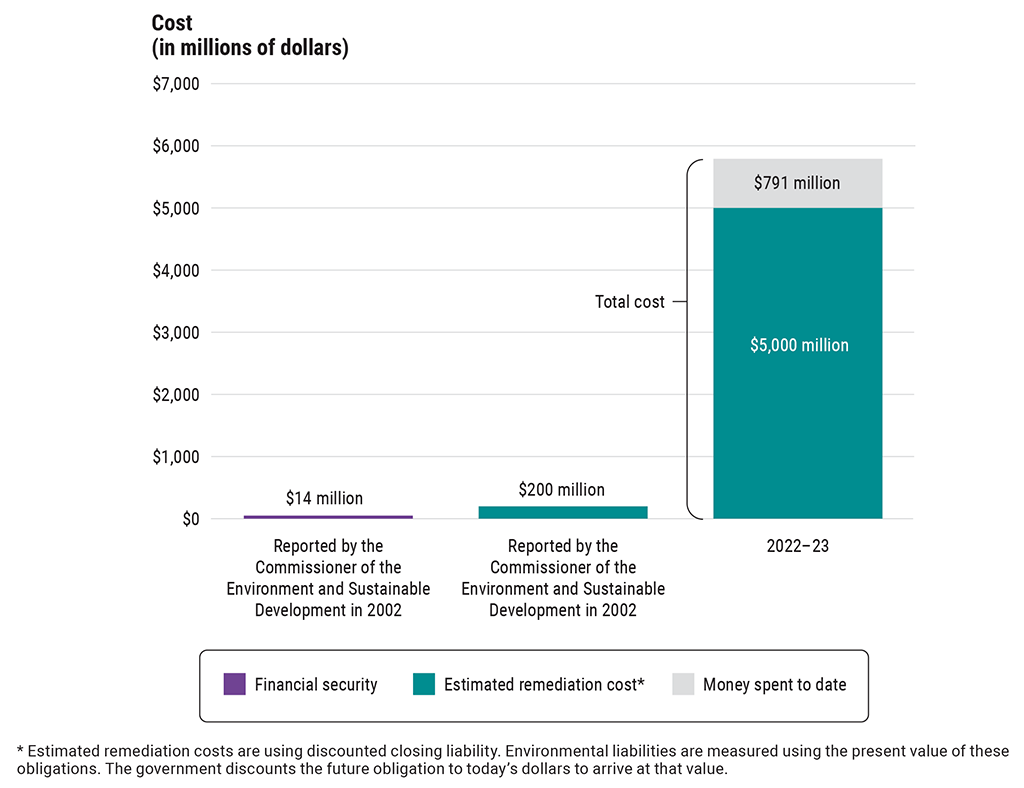

The estimated cost to remediate the mine has greatly increased since our 2002 audit, and the total cost to Canadians is much higher.

Source: Adapted from data in the 2002 Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the House of Commons, Chapter 3—Abandoned Mines in the North; and the Federal Contaminated Sites Inventory

Text version

This bar chart compares the estimated remediation costs for the Faro Mine as reported by the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development in 2002 with the estimated costs in the 2022–23 fiscal year.

In 2002, the Commissioner reported that the mine’s financial security was $14 million and the estimated remediation cost was $200 million. In 2022–23, the estimated remediation cost increased to $5 billion with an additional $791 million of money spent to date.

Estimated remediation costs are using discounted closing liability. Environmental liabilities are measured using the present value of these obligations. The government discounts the future obligation to today’s dollars to arrive at that value.

Infographic

Text version

Contaminated Sites in the North

Contaminated sites in northern Canada were not managed effectively. Despite work done, the financial liabilities had significantly increased, and gaps remained in practices to reduce risks to the environment and human health.

Contaminated sites include mines, military bases, airports, and landfills.

Contaminated sites contain substances that could harm the environment and human health.

If not managed properly, they can pollute the surrounding environment: air, water, and soil.

Highlights

There are 24,000 contaminated sites across Canada and 2,600 contaminated sites in northern Canada. Sixty percent of remediation costs are for contaminated sites in the North. Since 2005, 18,000 sites have been closed across Canada.

Since 2005, the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan has managed federal contaminated sites across Canada.

Financial risks have increased: The cost of remediating contaminated sites has increased by 59% since 2019 and is now over $10 billion.

Environmental and human health risks remain: Most environmental and human health targets were not on track to be met.

Since 2019, the Northern Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program has managed the 8 largest and highest‑risk abandoned mines

Faro Mine is one of the largest open-pit lead-zinc mines in the world. Mining waste at the site covers over 26,000 football fields, 1 metre deep, with contaminated water.

The site of Giant Mine, a former gold mine, contains 237,000 tonnes of toxic arsenic—enough to fill 9,480 dump trucks.

Faro Mine requires ongoing maintenance to prevent contaminated water from polluting surrounding areas.

Giant Mine requires arsenic to remain frozen underground forever.

They both don’t have perpetual care plans or a comprehensive approach to climate change adaptation.

The remediation of large abandoned mines in the North is an important opportunity to advance reconciliation with Indigenous peoples.

However, we heard that there was a lack of the following:

- meaningful engagement and consultation on the clean-up approach

- capacity within the communities to contribute to remediation efforts

- fair and adequate socio-economic benefits arising from remediation

Related information

Entities

Tabling date

- 30 April 2024

Related audits

- 2012 Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development

Chapter 3—Federal contaminated sites and their impacts - 2002 Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development

Chapter 2—The legacy of federal contaminated sites - 2002 Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development

Chapter 3—Abandoned mines in the North