2014 Fall Report of the Auditor General of Canada Chapter 2—Support for Combatting Transnational Crime

2014 Fall Report of the Auditor General of Canada

Chapter 2—Support for Combatting Transnational Crime

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Observations and Recommendations

- Program operations and performance

- Information sharing and cooperation

- RCMP liaison officers have advanced Canadian investigations through their information-sharing practices

- The costs and benefits of increased Europol participation have not been assessed

- Justice Canada processes extradition and mutual legal assistance requests appropriately, but does not monitor timeliness

- The RCMP could not generally access information on Canadians detained abroad

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- Appendix—List of recommendations

- Exhibits:

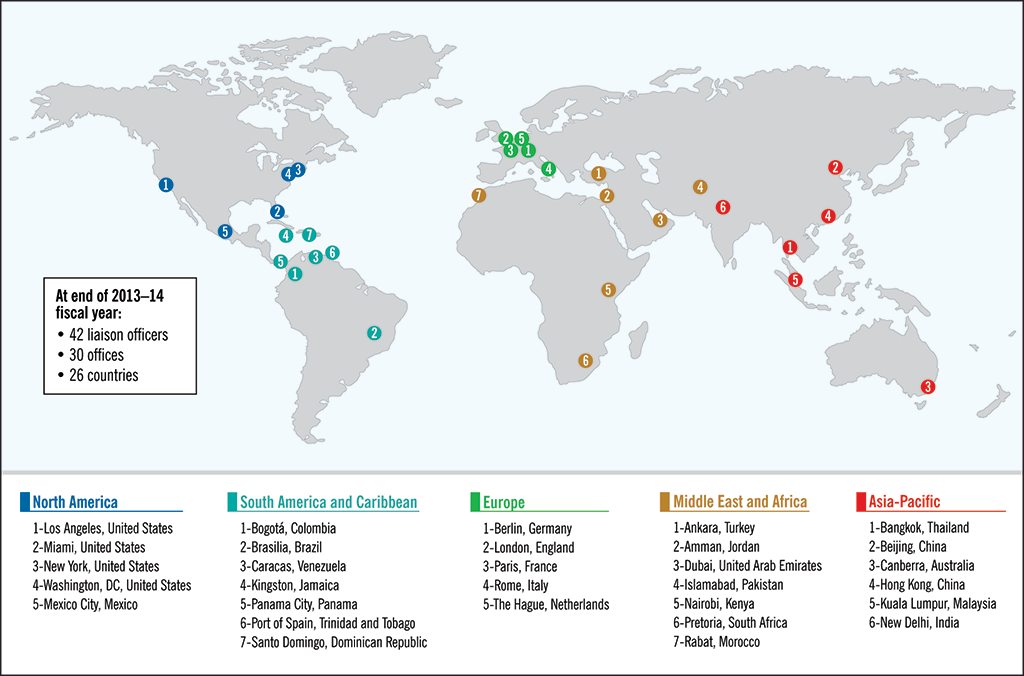

- 2.1—RCMP liaison officers are located in 26 countries

- 2.2—Nearly half of requests received by RCMP liaison officers in 2013 were related to serious crime

- 2.3—Canada intervened to prevent human smuggling

- 2.4—RCMP liaison officers share information with a variety of Canadian, foreign, and international organizations

- 2.5—Requests for extradition and mutual legal assistance in the 2012–13 fiscal year came mainly from foreign authorities

- 2.6—Many requests for mutual legal assistance and extraditions in the 2011–13 fiscal years took more than a year to process

- 2.7—Information on sexual offenders convicted abroad is not shared with the RCMP

Performance audit reports

This report presents the results of a performance audit conducted by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada under the authority of the Auditor General Act.

A performance audit is an independent, objective, and systematic assessment of how well government is managing its activities, responsibilities, and resources. Audit topics are selected based on their significance. While the Office may comment on policy implementation in a performance audit, it does not comment on the merits of a policy.

Performance audits are planned, performed, and reported in accordance with professional auditing standards and Office policies. They are conducted by qualified auditors who

- establish audit objectives and criteria for the assessment of performance;

- gather the evidence necessary to assess performance against the criteria;

- report both positive and negative findings;

- conclude against the established audit objectives; and

- make recommendations for improvement when there are significant differences between criteria and assessed performance.

Performance audits contribute to a public service that is ethical and effective and a government that is accountable to Parliament and Canadians.

Introduction

2.1 Many crimes that affect Canadians begin or end with actions taken beyond our borders; criminals and their organizations do not view borders as limitations on their activities. The Government of Canada is responsible for enforcing legislation that is meant to protect Canadians from crimes and criminals that cross its borders, and it shares that responsibility with the provinces.

2.2 The international character of serious crime is facilitated by the expansion of technology, increased mobility, and the adaptive nature of criminal networks. These trends are evidenced in the types of serious crimes being committed in more than one country, such as drug trafficking, corruption, theft, money laundering, child pornography, identity-related crime, mass-marketing fraud, human trafficking and migrant smuggling. To address these crimes, it is important that the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) work with its international counterparts to obtain and share information that advances their criminal investigations and those of other police forces in Canada.

2.3 Canadian law enforcement agencies do not have policing authority outside of Canada. To address crimes that extend beyond the country’s borders, Canada has entered into numerous cooperation agreements with foreign agencies. They share information through police-to-police networks, multilateral policing organizations such as INTERPOL and Europol, and formal mechanisms such as mutual legal assistance, and extradition treaties.

2.4 To advance investigations involving transnational crime, Canada’s law enforcement agencies rely on a network of RCMP liaison officers, who are located in various countries and interact with foreign law enforcement agencies to extend Canada’s investigative reach. RCMP liaison officers foster and maintain key relationships with foreign law enforcement agencies. These officers receive requests from both Canadian and foreign law enforcement agencies to advance criminal investigations of interest to Canada. These requests support operational files and include, for example, routine background checks on individuals, inquiries with local police, reporting of drug deliveries, obtaining or sharing human smuggling information, and following up on outstanding requests for evidence or extradition.

2.5 International sharing of police information is not new to Canada; the RCMP Liaison Officer Program started during World War II. Over the years, the role, locations, and need for this program have all grown substantially.

Focus of the audit

2.6 We examined whether the RCMP established priorities for serious and organized crime and aligned its international programming with those priorities, and whether the RCMP and the Department of Justice Canada (Justice Canada) had in place the systems and practices necessary to address their international requirements. Between 1 April 2010 and 31 May 2014, we examined the management of the RCMP Liaison Officer Program and its systems and practices for addressing its international requirements. More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this chapter.

Observations and Recommendations

Program operations and performance

2.7 The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) Liaison Officer Program posts police officers in foreign cities on behalf of Canada’s entire law enforcement community. The Program has 103 employees and a budget of approximately $19 million. It provides direction, support, and assistance to Canadian law enforcement agencies in the prevention and detection of crimes committed in Canada and those committed abroad that affect Canada.

2.8 The RCMP currently has 42 liaison officers posted around the world (Exhibit 2.1), who are responsible for working with police forces in one or more countries. For example, the one liaison officer posted in Jordan is accountable for maintaining links and advancing investigations with police forces in Algeria, Cyprus, Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, Libya, Syria, and Tunisia. Temporary liaison officers can also be posted abroad to assist with special projects or investigations. The Program also includes 61 employees in Ottawa who support its operations abroad, including its INTERPOL and Europol operations.

Exhibit 2.1—RCMP liaison officers are located in 26 countries

2.9 RCMP liaison officers received and responded to more than 2,200 requests in 2013, with about 60 percent of requests originating from within Canada. These requests can range from simple routine checks to specific criminal intelligence information related to ongoing major cases. Almost half of all requests are related to serious crimes such as child exploitation, money laundering, and drug smuggling that are often conducted through organized networks of criminals (Exhibit 2.2).

Exhibit 2.2—Nearly half of requests received by RCMP liaison officers in 2013 were related to serious crime

| Nature of requests | Number | Percentage of total |

|---|---|---|

|

||

|

71 | 3% |

|

593 | 26% |

|

170 | 8% |

|

20 | 1% |

|

166 | 7% |

|

77 | 3% |

| Sub-total | 1,097 | 48% |

|

17 | 1% |

|

126 | 6% |

|

150 | 7% |

|

366 | 16% |

|

498 | 22% |

| Total requests | 2,254 | 100% |

Source: Analysis based on data obtained from the RCMP

2.10 Overall, we found that the RCMP aligned the operations of the Liaison Officer Program to respond to priorities for serious and organized crime, but had not developed a process to assess the overall performance of the Program. Such a process would help the RCMP know whether it is using the Program efficiently and help to ensure its continued ability to adjust to changing criminal trends and national priorities.

The Liaison Officer Program adjusts to changing priorities

2.11 Because crime is becoming more and more transnational and involves Canadians both domestically and abroad, the RCMP needs to ensure that it aligns its liaison officers’ locations and activities with its priorities. Moreover, these placements must be strategically made, given the RCMP’s limited resources and the large number of requests.

2.12 Establishing priorities. We examined how the RCMP established its priorities for serious and organized crime and how liaison officers are made aware of these priorities. We found that it does so through consultations with its partners and the work of various international and domestic committees, such as the Canada–United States Cross-Border Crime Forum, the National Coordinating Committee on Organized Crime, federal interdepartmental committees, and committees with municipal and provincial police forces. In its Report on Plans and Priorities 2013–2014, the RCMP identified the following key priorities on crime:

- serious and organized crime (for example, financial crimes, and crimes related to drugs, human trafficking, and border security),

- national security, and

- economic integrity.

2.13 The RCMP uses these broad priorities to develop more specific operational and strategic direction through its National Integrated Operations Council, which is composed of representatives of various parts of the RCMP, and meets annually to develop its national enforcement and intelligence priorities. The RCMP communicates these priorities throughout its organization, including directly with its liaison officers, and with other federal organizations and law enforcement agencies.

2.14 Responding to requests—locations and actions. We also examined how the RCMP aligned its Liaison Officer Program with its priorities. We found that liaison officers responded to all requests received, most of which were specifically related to priorities. We also found that the RCMP was able to expand its international capacity in response to new priorities. For example, after the arrival of two migrant vessels on the Pacific coast of Canada, the government and the RCMP identified human smuggling and illegal migration as priorities. Subsequently, the RCMP expanded its efforts against human smuggling by deploying temporary liaison officers to key locations around the world (Exhibit 2.3).

Exhibit 2.3—Canada intervened to prevent human smuggling

In 2009, the migrant vessel Ocean Lady arrived in British Columbia, carrying 76 migrants; in 2010, the migrant vessel Sun Sea arrived, carrying 492 migrants. After these incidents, the Government of Canada identified human smuggling and prevention of illegal migration as priorities. Beginning in the 2011–12 fiscal year, the government provided about $13 million per year in dedicated funding to several departments and agencies to combat human smuggling. Of this amount, the RCMP was allocated about $5 million per year to increase its capacity to investigate and disrupt human smuggling networks.

The project was initiated to enhance intelligence collection, analysis, and dissemination; bolster situational awareness; and support prevention efforts and targeting of criminal networks. During the audit, the RCMP had nine temporary dedicated resources deployed in southeast Asia and west Africa to support efforts against human smuggling. These liaison officers worked with the other RCMP’s liaison officers in the region, and with relevant domestic and international partners, to coordinate with and support domestic and international policing operations.

RCMP files indicate that, to date, efforts by the RCMP and other federal agencies have prevented over 750 illegal migrants from reaching Canadian shores. Preventing illegal migration could save the government and Canadian taxpayers significant costs. For example, a government document estimates that the cost to intercept the Sun Sea and process the immigrants from it totalled about $25 million.

Note: Information was not audited

Source: Information obtained from the RCMP

2.15 We also found that the RCMP was able to react to changing circumstances by rapidly deploying staff temporarily when necessary. For example, when terrorists attacked in Algeria in January 2013, RCMP liaison officers from Amman, London, Hong Kong, and Rabat assisted Algerian authorities with their investigation and looked for any evidence of Canadian involvement. Similarly, a terrorist attack at a shopping mall in Nairobi, Kenya in September 2013, in which there were Canadian casualties, prompted the liaison officer in Pretoria to immediately investigate and work with international partners, with support from investigative officers deployed from Canada.

2.16 Recruiting liaison officers. Because liaison officers must be able to respond to a broad range of requests (see Exhibit 2.2), it is imperative that they have a variety of key competencies and experience, such as effective communication skills and experience in specialized areas such as organized crime. We examined the recruitment process for liaison officers. We sampled information for 29 liaison officers posted or rotated abroad between the 2011–12 and 2013–14 fiscal years. We reviewed the selected position requirements, the successful candidates’ résumés, and their corresponding employment files. We also reviewed files of ongoing and closed cases, to understand the roles of liaison officers.

2.17 We found that all of the selected candidates in our sample had demonstrated, in their previous experience, one or more of the skills and competencies identified for the posts. We also observed that most of these officers had more than 15 years’ experience with the RCMP, including experience with at least one area of the RCMP’s strategic priorities. We also found in the files we reviewed that the liaison officers demonstrated a high degree of competency in communication skills. They demonstrated that the relationships they developed and maintained with foreign partners were critical to their success.

The RCMP does not have the information it needs to assess the Liaison Officer Program

2.18 Posting liaison officers abroad carries significant costs. RCMP officials have identified the average annual cost for one liaison officer in 2013 as $500,000, including salaries, accommodations, office maintenance, and operating expenditures such as travel. New posts carry higher initial costs, averaging $750,000 per liaison officer in the first year, as these posts often include costs associated with renovating office space and obtaining new equipment. These costs compare with an average annual cost of approximately $210,000 per equivalent member in its domestic policing program.

2.19 We examined how the RCMP determined the appropriate size and deployment for its Liaison Officer Program.

2.20 The last comprehensive evaluation of the Program by the RCMP was conducted in 2003. The evaluation reported on the Program’s operations, ability to establish partnerships, distribution of resources, and training capacity, among other issues. In general, the evaluation concluded that the Program was administered effectively, but pointed to several areas that needed improvement. The resulting report recommended an ongoing process for evaluating overseas postings in order to determine the Program’s future ability to meet changing criminal trends and national priorities.

2.21 In 2008, the RCMP conducted a gap analysis to assess whether the allocation of liaison officers matched RCMP and government priorities. The analysis identified various options to redistribute existing liaison officer locations and to add liaison officers to address immediate pressures on the Program. Since that analysis, the RCMP has conducted various regional studies to assess the distribution of liaison officer positions on the basis of regional priorities, workload, and specific trends. However, these ad hoc assessments were not comprehensive and did not focus on overall program performance. In 2014, the RCMP began a new initiative to assess the performance of its International Policing program—of which the Liaison Officer Program is a part—but had yet to complete it by the time of our audit.

2.22 We found that the RCMP does not currently have a systematic means of evaluating its Liaison Officer Program or of identifying how best to use the Program’s resources to meet its priorities. Without a comprehensive evaluation or other means of regularly assessing performance, the RCMP does not know either the optimal size of the Program or the best locations for its resources. Furthermore, since maintaining liaison officers abroad incurs more than twice the cost of employing them within Canada, proper planning and assessment is necessary for the RCMP to decide how best to use available resources. We note that the 2009 Treasury Board of Canada Policy on Evaluation requires that all programs be evaluated every five years.

2.23 Recommendation. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police should assess the performance of its Liaison Officer Program to ensure that it gets the best use of its limited resources.

The RCMP’s response. Agreed. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) is focusing its International Program to further advance criminal investigations impacting Canada. A comprehensive Performance Management Framework is currently being developed to better guide senior management on program requirements, operational priorities, risks, and financial constraints. This Framework will include performance measures designed to ensure that the Liaison Officer Program is using its limited resources in the most effective and efficient manner possible. Full implementation of the Framework is anticipated by the end of the 2015–16 fiscal year. After the Framework’s full implementation, the RCMP will conduct a performance assessment of the International Program to ensure that it achieves expected outcomes and demonstrates efficiency and cost-effectiveness.

Information sharing and cooperation

2.24 Law enforcement agencies across Canada rely on Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) liaison officers to collect and share information from international police forces in order to advance their own criminal investigations. Liaison officers develop and maintain links with foreign law enforcement agencies to exchange information (Exhibit 2.4). Informal police-to-police cooperation works well with most countries; others require more formal processes.

Exhibit 2.4—RCMP liaison officers share information with a variety of Canadian, foreign, and international organizations

2.25 Overall, we found that RCMP liaison officers cooperate with domestic and foreign partners to access and share information, but that the RCMP had not assessed the potential of greater participation in Europol and did not generally have access to information about Canadians detained abroad. We also found that the Department of Justice Canada (Justice Canada) processes formal requests for extradition and obtains evidence from abroad appropriately, but does not monitor the reasons for delays in the process. Information sharing and cooperation are key elements in helping to advance criminal investigations within Canada and abroad in order to protect Canadians from transnational criminal activities.

RCMP liaison officers have advanced Canadian investigations through their information-sharing practices

2.26 Liaison officers regularly share information with Canadian and foreign law enforcement agencies to advance criminal investigations. Depending on the needs of the investigation, shared information may include personal data such as addresses, phone numbers, travel activity, passport information, and criminal records. Liaison officers may also be asked to exchange information about ongoing investigations.

2.27 The authority to determine what information can be shared typically resides with the lead investigator from the originating police organization. Investigators from Canada’s police organizations must carefully consider what information should be shared with foreign partners while ensuring adequate safeguards, so that investigations are not compromised.

Police Reporting Occurrence System—An RCMP information system to manage investigations and store information about individuals, vehicles, addresses, and businesses involved in criminal investigations.

Canadian Police Information Centre—A national information sharing system that contains records on crimes and criminals. Law enforcement agencies across Canada can access and input information on criminal investigations into the system. The type of information ranges from records of vehicles and property that were possibly stolen to information about individuals who have criminal records.

2.28 We assessed whether the liaison officers had the information necessary to fulfill their operational requirements. We examined information shared within eight liaison offices in three regions. We found that liaison officers had access to the information required to support investigations both domestically and internationally. They had access to key case information as well as RCMP systems and databases such as the Police Reporting Occurrence System and the Canadian Police Information Centre. Access to key systems and case information allowed liaison officers to react in a timely manner to requests related to investigations.

2.29 We also examined whether the liaison officers shared appropriate information with foreign law enforcement officials, while respecting lead investigators’ directions on what could be shared. We reviewed the documentation of a sample of cases where domestic partners asked liaison officers to obtain information from foreign law enforcement agencies. Many of the files we reviewed showed that liaison officers had been directed to share only selected information with partners. We found that in all of the files we reviewed, the documentation shows that liaison officers adhered to the instructions on information-sharing provided by the Canadian lead investigators.

2.30 However, liaison officers informed us that foreign partners sometimes expressed concern when limited information was shared by Canada. Nevertheless, in most files that we reviewed, we saw that liaison officers were able to gather the information sought from foreign partners.

The costs and benefits of increased Europol participation have not been assessed

2.31 The RCMP participates in multilateral policing organizations, particularly INTERPOL and Europol. We assessed whether the RCMP had identified the value in doing so, in terms of the costs, potential opportunities, and challenges. We examined the RCMP’s engagement with both INTERPOL and Europol.

2.32 INTERPOL. INTERPOL is an international network of 190 countries with a primary mandate of facilitating police cooperation. Canada’s involvement with INTERPOL is fully integrated within the RCMP, and many Canadian police agencies use this resource. Canada joined INTERPOL in 1949, and the RCMP was given responsibility for managing Canada’s involvement. Canadian law enforcement agencies use INTERPOL to conduct international checks on criminal records, passports, vehicle identification numbers, and firearms.

2.33 We found that INTERPOL serves as an important tool for the RCMP and Canadian law enforcement agencies. Through INTERPOL, these agencies issue notices to all member countries to help locate both travelling fugitives and missing persons. In terms of cost, we found that the RCMP pays Canada’s share of 3 percent of the overall INTERPOL budget and also covers the cost of 26 employees working in Ottawa. For the 2013–14 fiscal year, the total cost to the RCMP was $5.7 million.

2.34 Europol. The role of Europol is very different from that of INTERPOL. Europol is a policing organization that brings together European and other police agencies to address crimes that cross international borders. Its mandate is to enable police organizations to work collaboratively to address crimes linked to at least two European countries. It includes 150 liaison officers from 28 European Union and 18 other countries, all working from the same location in The Hague, the Netherlands.

2.35 Canada’s engagement with Europol is relatively new: Canada joined Europol as a non-European third-party member in 2005. The requests for information on criminal activity between Canada and Europe are significant; in 2013, about one quarter of all requests received by liaison officers involved European countries. Similarly, about 20 percent of the RCMP’s liaison officers are located in Europe. Most of the costs of operating Europol are borne by the European Union; third-party members are responsible only for the costs of their own members.

2.36 The RCMP notes that European countries are dedicating an increasing number of resources to Europol, which is becoming an important avenue for their sharing of information and their work with other countries’ police agencies. At the time of our audit, the RCMP had 1 liaison officer working at Europol and was participating in 3 of the 22 Europol thematic intelligence projects: synthetic drugs, payment card fraud, and outlaw motorcycle gangs.

2.37 We found that the RCMP had not assessed the costs and benefits of greater participation in Europol, including the impact that this could have on the size and location of the Liaison Officer Program in Europe and how best to use its limited resources (see our discussion at paragraph 2.22). RCMP management acknowledged that it was not currently using Europol extensively. By the end of our audit, the RCMP had determined that a study to assess the pros and cons of greater participation in Europol was warranted.

2.38 Recommendation. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police should assess the costs, potential opportunities, and challenges associated with greater participation in Europol.

The RCMP’s response. Agreed. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police, in consultation with Canadian and international law enforcement, has initiated a formal assessment to better determine the costs, potential opportunities, and challenges that may result from greater participation in Europol, beyond the recent deployment of a liaison officer. The assessment is anticipated to be completed by spring 2015.

Justice Canada processes extradition and mutual legal assistance requests appropriately, but does not monitor timeliness

Mutual legal assistance—Assistance to domestic and foreign police and prosecutors in sharing evidence and providing other types of investigative support to advance criminal investigations and prosecutions.

Extradition—Surrender of a person wanted for prosecution, or imposition or enforcement of a sentence, in the jurisdiction of the requesting state.

2.39 The RCMP and other law enforcement agencies often require information and evidence from foreign jurisdictions and must use a formal means to acquire them. Such mechanisms are required to gather evidence for most legal proceedings, as well as for requests to apprehend and surrender individuals to and from foreign jurisdictions. In these instances, law enforcement agencies need to work with the central justice authority of the associated country. In Canada, these requests go to Justice Canada.

2.40 Justice Canada is responsible for processing Canadian and foreign requests for mutual legal assistance and extradition. It also provides advice to the Minister of Justice on extraditions requested from abroad under the Extradition Act. To process these requests, Justice Canada deals with Canadian and foreign law enforcement agencies and prosecutors, as well as with central authorities of other countries. Justice Canada reviews the requests and ensures that the supporting documents and evidence are sufficient and that required authorizations have been issued. Lack of supporting documentation, evidence, or authorization necessitates revisions before requests can proceed. In the 2012–13 fiscal year, Justice Canada received close to 1,000 new requests (Exhibit 2.5).

Exhibit 2.5—Requests for extradition and mutual legal assistance in the 2012–13 fiscal year came mainly from foreign authorities

| Source of request | Extradition | Mutual legal assistance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of requests |

Percentage of total |

Number of requests |

Percentage of total |

|

| Foreign authorities | 141 | 76% | 625 | 79% |

| Canadian authorities | 44 | 24% | 166 | 21% |

| Total | 185 | 100% | 791 | 100% |

Source: Analysis based on data obtained from the Department of Justice Canada

2.41 Justice Canada implements numerous agreements with other countries to facilitate these processes. Canada has signed extradition agreements with 51 countries and has listed an additional 31 countries and 3 international criminal tribunals as extradition partners in a schedule to the Extradition Act. Canada has also signed mutual legal assistance treaties with 35 countries and has listed an additional 3 international criminal tribunals in a schedule to the Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Act. Furthermore, Canada has signed international conventions, such as the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime and the United Nations Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air. When these conventions are integrated into statutes, they establish the terms and conditions under which extradition and mutual legal assistance are possible.

2.42 Processing requests. We examined whether Justice Canada had processes in place to complete extradition and mutual legal assistance requests appropriately. We examined 50 extradition and mutual legal assistance files from between 2011 and 2013. We selected a variety of files, which included requests coming into Canada, going out from Canada to foreign jurisdictions, and both ongoing and closed files, to review the various steps and approvals for requests, the parties involved, the treaties used, and the outcomes of the files.

2.43 We found that Justice Canada had appropriate processes in place to ensure that supporting documents complied with the requirements of pertinent treaties and legislation. The Department also issued the required authorizations and transmitted relevant documents to the justice and police organizations involved in the files. For most of the files reviewed, Justice Canada monitored and followed up on requests regularly.

2.44 Processing time. Through the course of our audit, various police officials expressed concerns about the overall time it took to process requests for extradition and mutual legal assistance. We noted cases in the past where failing to obtain evidence in advance of court proceedings or to extradite individuals in a timely manner affected police investigations and criminal proceedings. We found that it often took over a year to process the requests that we reviewed (Exhibit 2.6).

Exhibit 2.6—Many requests for mutual legal assistance and extraditions in the 2011–13 fiscal years took more than a year to process

| Source of request | Average processing time | |

|---|---|---|

| Extradition | Mutual legal assistance | |

| Foreign authorities | 15 months | 7 months |

| Canadian authorities | 12 months | 20 months |

Source: Analysis based on data obtained from the Department of Justice Canada

2.45 We examined the role of Justice Canada in processing these requests. We found that only about 15 percent of the overall time needed to process mutual legal assistance requests in our sample was within Justice Canada’s control; for extradition requests, about 30 percent of the overall time it took for processing was within its control. The Extradition Act includes statutory deadlines for specific actions by Justice Canada when processing extradition requests from foreign partners. We found that these deadlines were met for all of the extradition requests we reviewed.

2.46 Various delays not related to Justice Canada’s actions accounted for the majority of the time required. These delays included the time spent waiting for evidence from foreign and domestic organizations, revisions that had to be made to original requests, translation, and delays in judicial processes. Moreover, police organizations had sometimes submitted incomplete information or were unable to locate a person or the required evidence.

2.47 We examined whether Justice Canada, as the central authority, had a process in place to monitor the main reasons for the delays and whether the Department had considered what could be done to address them. We found that Justice Canada had not taken any actions to assess the time taken to process requests for extradition or mutual legal assistance. By not assessing the reasons for delays in processing these requests, Justice Canada, as the central authority, does not have the insight needed to develop processes to help minimize them and improve results.

2.48 Recommendation. The Department of Justice Canada, in consultation with domestic and foreign partners, should assess the reasons for significant delays in processing requests for extradition or mutual legal assistance and develop strategies to mitigate them where possible.

The Department of Justice Canada’s response. Agreed. The Department of Justice Canada is committed to ensuring the best possible service to domestic and international partners. To that end, Justice Canada regularly engages in consultations with significant treaty partners and domestic partners to discuss the progress of files and to identify issues including delays that are reducing the effectiveness of international cooperation. Justice Canada will review its outstanding file inventory in the 2014–15 fiscal year to identify files involving significant delay. Meetings, either in person or by telephone or video conferencing, will be arranged with relevant partners throughout the 2015–16 fiscal year to discuss methods to mitigate these delays.

The RCMP could not generally access information on Canadians detained abroad

2.49 The RCMP has determined that information on Canadians abroad who are arrested, charged, and convicted of serious crimes and their release dates is potentially valuable to the organization, as this information would facilitate its domestic policing efforts. For example, suspects in domestic criminal investigations who go missing may have been arrested, charged, convicted, or released from prison abroad.

2.50 Local authorities notify Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada of the detention of Canadians abroad when those detained exercise their rights to receive consular assistance under the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations. In 2011, the Department (then the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade) opened more than 1,800 arrest and detention cases and received information on more than 1,700 ongoing cases related to Canadians imprisoned abroad. Between 2003 and 2014, Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada also received about 3,300 notifications of the release dates of Canadians detained abroad.

2.51 We examined whether the RCMP had access to this information. We found that, in general, the RCMP does not receive information from Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada on Canadians arrested, charged, convicted, or released from prison abroad. This is because of restrictions in the Privacy Act on the sharing of information about individuals, and restrictions in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms on the sharing of information about Canadians with law enforcement agencies. The RCMP can gain access to this information in specific cases—when it clearly relates to criminal investigations, or when the public interest outweighs any invasion of privacy that could result from the disclosure. It can only obtain this access upon written request and when it is determined that the request is in accordance with the requirements of the Privacy Act. We found that the RCMP and other domestic law enforcement agencies had submitted such requests 34 times in the three years we examined and were provided with the requested information in 17 instances.

2.52 In some countries, information on individuals incarcerated and released from prison is publicly available, but the nationality of the individual concerned is not always published. Canadian legislation allows for the sharing of publicly available information among federal organizations. The decision whether to share, however, rests with the department or agency holding the information. We found that Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada’s practice is to not share this information; thus, it is not provided to the RCMP.

2.53 In contrast, we met representatives from foreign law enforcement agencies who informed us that their consular officials regularly shared information with them. For example, in keeping with their legal framework, consular officials from the United Kingdom (UK) tell other relevant UK authorities when a citizen is arrested abroad for certain serious offenses, such as child sex abuse or drug crimes.

2.54 Moreover, in 2013, the UK initiated a project for the then Group of Eight (G8) countries’ enforcement agencies to exchange information on G8 foreign nationals who are convicted of serious crimes in each other’s countries. The aim of this project is to establish routine notification procedures for the exchange of conviction and prison-release data among the countries. Without information on Canadians convicted abroad, the RCMP cannot fully participate in this project with its partners, and its ability to mitigate domestic crimes by those convicted abroad is diminished.

2.55 In 2010, the government established an interdepartmental working group on child sex offenders. This working group explores possible legislative changes and the development of a framework that would guide federal efforts such as an information sharing protocol (Exhibit 2.7).

Exhibit 2.7—Information on sexual offenders convicted abroad is not shared with the RCMP

The Sex Offender Information Registration Act was amended in 2011 to include a new Criminal Code of Canada provision to address the registration of sex offenders convicted abroad. The Sex Offender Information provisions in the Criminal Code apply to any person who has been convicted of a sex offence in another country, serves his or her sentence and is released, and then returns to Canada. These people are obligated to report to a local police service within seven days of arriving in Canada and provide to them their name, date of birth, gender, address, other personal information, and information about their conviction.

We found that 25 offenders have registered as required by law since 2011. The RCMP cannot confirm whether there were other convicted sex offenders who did not register on the National Sex Offender Registry upon their return to Canada because it does not have access to Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada’s information on convicted offenders released from foreign prisons.

Public Safety Canada and the RCMP are co-leading an interdepartmental initiative to develop protocols that would facilitate the RCMP’s access to this information. At the time of our audit, they had met seven times between 2010 and 2013, but no new protocols had been established.

2.56 Recommendation. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada should work together to identify information related to Canadians arrested, charged, convicted, or released from prison abroad that can be shared legally and should put in place processes to share this information with the RCMP.

The RCMP’s response. Agreed. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) is fully committed to working with Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada, and with other federal agencies and departments, to review information sharing practices and policies, and to establish a process for Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada to share information legally with the RCMP regarding Canadians who are charged, arrested, convicted, or released from prison abroad.

Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada’s response. Agreed. Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada recognizes the increasingly transnational nature of crime and is pleased to work with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) as part of the Government of Canada’s commitment to protecting Canadians from crimes and criminals that cross Canadian borders.

Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada remains committed to sharing information with the RCMP in accordance with the Privacy Act and its protocol with the RCMP concerning cooperation in consular cases involving Canadians detained abroad. The Department is looking forward to reviewing and codifying existing practices related to requests for consular information from the RCMP and values its relationship with the RCMP’s liaison officer at Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada’s headquarters in Ottawa.

Conclusion

2.57 We concluded that the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) established priorities for serious and organized crime, aligned its international programming with those priorities, and has the necessary systems and practices in place to address its international requirements. The RCMP established and maintained links with key domestic and international partners to advance criminal investigations that affect Canada. Liaison officers possess the required competencies to function in their roles to develop and maintain relationships with international partners.

2.58 We also concluded that the RCMP has not assessed whether it is using available resources to their full potential. It has not assessed the optimum size or locations for its Liaison Officer Program and has not assessed the costs and benefits of greater participation in Europol.

2.59 We concluded that the Department of Justice Canada processes requests for mutual legal assistance and extraditions appropriately, but has not assessed the time taken to process those requests.

2.60 We concluded that in general the RCMP could not access information on Canadians arrested, charged, convicted, and released from prison abroad.

About the Audit

The Office of the Auditor General’s responsibility was to conduct an independent examination of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police’s international policing activities and the Department of Justice Canada’s international activities, to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs.

All of the audit work in this chapter was conducted in accordance with the standards for assurance engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance. While the Office adopts these standards as the minimum requirement for our audits, we also draw upon the standards and practices of other disciplines.

As part of our regular audit process, we obtained management’s confirmation that the findings reported in this chapter are factually based.

Objective

The audit objective was to determine whether the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) established priorities for serious and organized crime, and aligned its international programming with those priorities; and whether the RCMP and the Department of Justice Canada had the necessary systems and practices in place to address their international requirements.

Scope and approach

The scope of the audit focused on the capacity of the RCMP to address serious and organized crime by examining the systems and practices it had in place to support Canadian law enforcement agencies. We also examined the appropriateness of the practices used by Department of Justice Canada for extraditions and mutual legal assistance.

We examined documentation on how the RCMP adjusted the size and location of its Liaison Officer Program to meet its priorities. We also gathered and reviewed evaluations conducted by the RCMP on the Program. We examined a sample of 29 liaison officer job postings, candidate personnel files, and their relevant job experience. We conducted interviews with liaison officers in 8 offices and 3 regions, and with representatives at federal departments and from foreign agencies. We analyzed paper and electronic files of over 160 cases originating both from Canada and from abroad and handled by liaison officers between April 2011 and December 2013, to better understand the nature of the requests and the role of the liaison officers involved. We also selected a sample of 50 extradition and mutual legal assistance files from the Department of Justice Canada for the 2011 to 2013 calendar years, looking at both incoming requests from foreign states and outgoing requests from Canadian prosecutors.

We also performed limited audit work in Public Safety Canada, to assess its role in setting priorities, and in Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada, in relation to information it received and disseminated about Canadians detained abroad.

This audit did not examine provincial or municipal police forces, or RCMP policing work within Canada. It also did not look at international policing activities related to peacekeeping operations, border security, capacity building, or Canadian organizations’ involvement in international or humanitarian crises. The audit did not assess the activities of police forces that work with the RCMP or the RCMP’s investigative techniques. We also did not assess activities related to counter-terrorism or intelligence gathering.

Criteria

To determine whether the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) established priorities for serious and organized crime, and aligned its international programming with those priorities; and whether the RCMP and the Department of Justice Canada (Justice Canada) have the necessary systems and practices in place to address their international requirements, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

The RCMP has identified its international strategic priorities to combat serious and organized crime. |

|

|

RCMP programming is aligned with its priorities for serious and organized crime. |

|

|

The RCMP bases resource decisions for its Liaison Officer Program on program priorities for serious and organized crime. |

|

|

The RCMP has the information necessary to fulfill its operational requirements related to serious and organized crime for its Liaison Officer Program. |

|

|

The RCMP and the Department of Justice Canada have the tools necessary to fulfill their operational requirements related to their international programs for serious and organized crime. |

|

Management reviewed and accepted the suitability of the criteria used in the audit.

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period between April 2010 and May 2014. Audit work for this chapter was completed on 31 May 2014.

Audit team

Assistant Auditor General: Wendy Loschiuk

Principal: Frank Barrett

Director: Sami Hannoush

Donna Ardelean

Eve-Lyne Bouthillette

Catherine Martin

Anthony Stock

William Xu

For information, please contact Communications at 613-995-3708 or 1-888-761-5953 (toll-free).

Hearing impaired only TTY: 613-954-8042

Appendix—List of recommendations

The following is a list of recommendations found in Chapter 2. The number in front of the recommendation indicates the paragraph where it appears in the chapter. The numbers in parentheses indicate the paragraphs where the topic is discussed.

Program operations and performance

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

2.23 The Royal Canadian Mounted Police should assess the performance of its Liaison Officer Program to ensure that it gets the best use of its limited resources. (2.18–2.22) |

The RCMP’s response. Agreed. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) is focusing its International Program to further advance criminal investigations impacting Canada. A comprehensive Performance Management Framework is currently being developed to better guide senior management on program requirements, operational priorities, risks, and financial constraints. This Framework will include performance measures designed to ensure that the Liaison Officer Program is using its limited resources in the most effective and efficient manner possible. Full implementation of the Framework is anticipated by the end of the 2015–16 fiscal year. After the Framework’s full implementation, the RCMP will conduct a performance assessment of the International Program to ensure that it achieves expected outcomes and demonstrates efficiency and cost-effectiveness. |

Information sharing and cooperation

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

2.38 The Royal Canadian Mounted Police should assess the costs, potential opportunities, and challenges associated with greater participation in Europol. (2.31–2.37) |

The RCMP’s response. Agreed. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police, in consultation with Canadian and international law enforcement, has initiated a formal assessment to better determine the costs, potential opportunities, and challenges that may result from greater participation in Europol, beyond the recent deployment of a liaison officer. The assessment is anticipated to be completed by spring 2015. |

|

2.48 The Department of Justice Canada, in consultation with domestic and foreign partners, should assess the reasons for significant delays in processing requests for extradition or mutual legal assistance and develop strategies to mitigate them where possible. (2.39–2.47) |

The Department of Justice Canada’s response. Agreed. The Department of Justice Canada is committed to ensuring the best possible service to domestic and international partners. To that end, Justice Canada regularly engages in consultations with significant treaty partners and domestic partners to discuss the progress of files and to identify issues including delays that are reducing the effectiveness of international cooperation. Justice Canada will review its outstanding file inventory in the 2014–15 fiscal year to identify files involving significant delay. Meetings, either in person or by telephone or video conferencing, will be arranged with relevant partners throughout the 2015–16 fiscal year to discuss methods to mitigate these delays. |

|

2.56 The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada should work together to identify information related to Canadians arrested, charged, convicted, or released from prison abroad that can be shared legally and should put in place processes to share this information with the RCMP. (2.49–2.55) |

The RCMP’s response. Agreed. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) is fully committed to working with Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada, and with other federal agencies and departments, to review information sharing practices and policies, and to establish a process for Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada to share information legally with the RCMP regarding Canadians who are charged, arrested, convicted, or released from prison abroad. Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada’s response. Agreed. Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada recognizes the increasingly transnational nature of crime and is pleased to work with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) as part of the Government of Canada’s commitment to protecting Canadians from crimes and criminals that cross Canadian borders. Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada remains committed to sharing information with the RCMP in accordance with the Privacy Act and its protocol with the RCMP concerning cooperation in consular cases involving Canadians detained abroad. The Department is looking forward to reviewing and codifying existing practices related to requests for consular information from the RCMP and values its relationship with the RCMP’s liaison officer at Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada’s headquarters in Ottawa. |

PDF Versions

To access the Portable Document Format (PDF) version you must have a PDF reader installed. If you do not already have such a reader, there are numerous PDF readers available for free download or for purchase on the Internet: