Image Descriptions

2014 Fall Report of the Auditor General of Canada

Image Descriptions

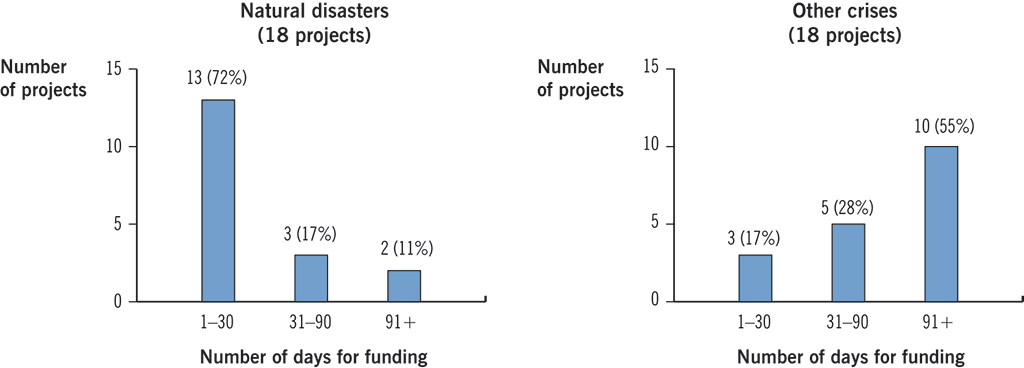

Exhibit 1.3—The timeliness of funding for 36 selected projects varied

Two bar charts show that two groups of selected projects differed in the usual length of time it took to establish funding.

The first chart represents 18 selected projects related to natural disasters. It shows that the time required to establish funding was 1 to 30 days for 13 (72%) of the projects, 31 to 90 days for 3 (17%) of the projects, and more than 91 days for 2 (11%) of the projects.

The second chart represents 18 selected projects related to other types of crises. It shows that the time required to establish funding was more than 91 days for 10 (55%) of the projects, 31 to 90 days for 5 (28%) of the projects, and 1 to 30 days for 3 (17%) of the projects.

The number of days for establishing funding is the length of time for the Department to enter into grant agreements with partners, starting from the issue of applicable appeals, increases to existing appeals, or receipt of proposals from partners in cases where there is no applicable appeal.

Note: The “number of days for funding” is the length of time for the Department to enter into grant agreements with partners, starting from the issue of applicable appeals, increases to existing appeals, or receipt of proposals from partners in cases where there is no applicable appeal.

(Return)

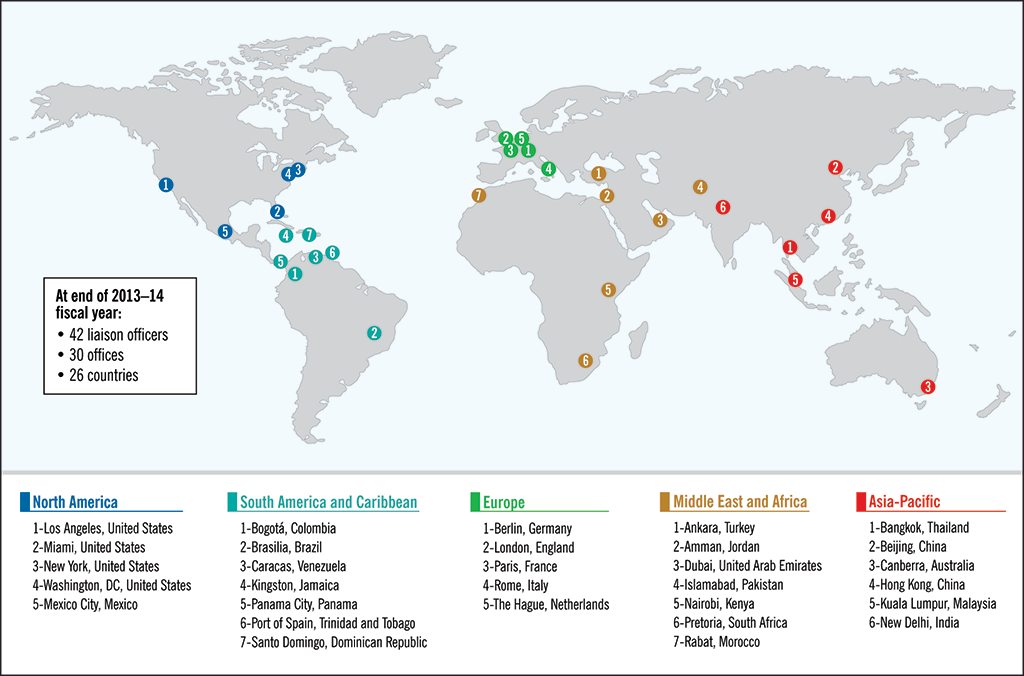

Exhibit 2.1—RCMP liaison officers are located in 26 countries

This world map shows where RCMP liaison officers are posted worldwide.

At the end of the 2013–14 fiscal year, there were 42 liaison officers posted in 30 offices in 26 countries. These liaison officers were posted in the following locations.

North America:

- Los Angeles, United States

- Miami, United States

- New York, United States

- Washington DC, United States

- Mexico City, Mexico

South America and Caribbean

- Bogota, Colombia

- Brasilia, Brazil

- Caracas, Venezuela

- Kingston, Jamaica

- Panama City, Panama

- Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago

- Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic

Europe

- Berlin, Germany

- London, England

- Paris, France

- Rome, Italy

- The Hague, Netherlands

Middle East and Africa

- Ankara, Turkey

- Amman, Jordan

- Dubai, United Arab Emirates

- Islamabad, Pakistan

- Nairobi, Kenya

- Pretoria, South Africa

- Rabat, Morocco

Asia-Pacific

- Bangkok, Thailand

- Beijing, China

- Canberra, Australia

- Hong Kong, China

- Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

- New Delhi, India

Source: Data obtained from the RCMP

(Return)

Exhibit 2.4—RCMP liaison officers share information with a variety of Canadian, foreign, and international organizations

This diagram shows that RCMP liaison officers share information with a variety of Canadian, foreign and international organizations. The organizations presented are the following:

- RCMP (e.g., criminal investigations),

- Special project teams (e.g., migrant smuggling),

- Multilateral policing organizations (e.g., INTERPOL, Europol),

- Federal partners (e.g., Canada Border Services Agency, Department of Justice Canada),

- Foreign law enforcement agencies (e.g., Australian Federal Police, Federal Bureau of Investigation),

- Other Canadian law enforcement agencies (e.g., Toronto Police Service, Sûreté du Québec)

Source: Information obtained from the RCMP

(Return)

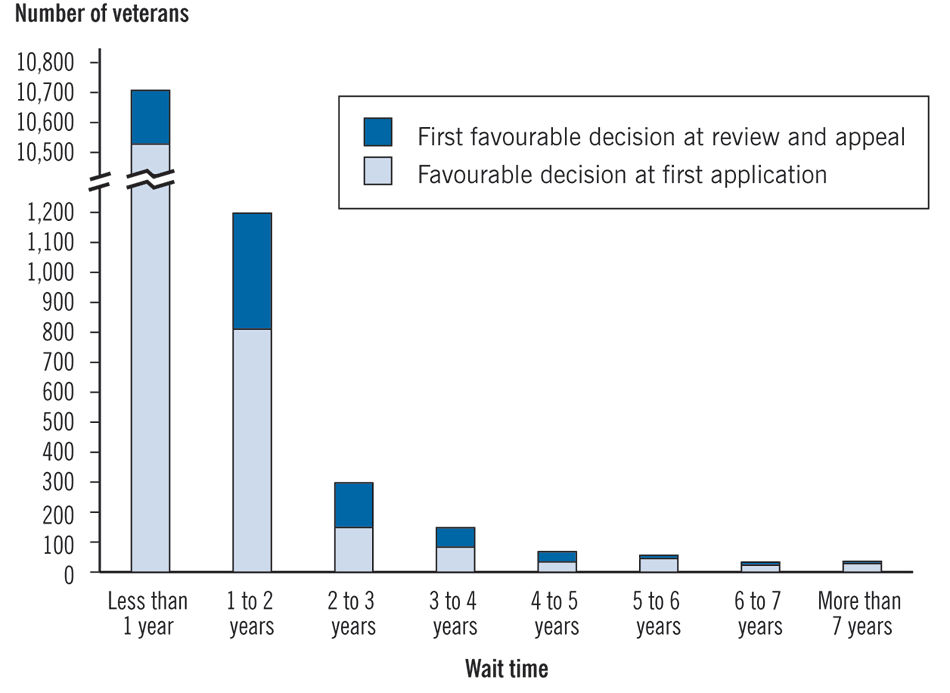

Exhibit 3.2—Time frames for a favourable disability benefits decision for veterans with a mental health condition

This bar chart shows that most veterans with a mental health condition received a favourable disability benefits decision at first application in less than a year, however for some it took much longer. The numbers of veterans who received a favourable disability benefits decision at first application were as follows:

- In less than one year: 10,528

- From one to two years: 811

- From two to three years: 149

- From three to four years: 83

- From four to five years: 34

- From five to six years: 45

- From six to seven years: 23

- After more than seven years: 28

The numbers of veterans who received a favourable disability benefits decision at review and appeal were as follows:

- In less than one year: 179

- From one to two years: 387

- From two to three years: 149

- From three to four years: 65

- From four to five years: 34

- From five to six years: 11

- From six to seven years: 10

- After more than seven years: 8

Source: Based on data obtained from Veterans Affairs Canada’s Client Service Delivery Network system for disability applications, and for review and appeal applications, from 1 April 2006 through 6 June 2014.

(Return)

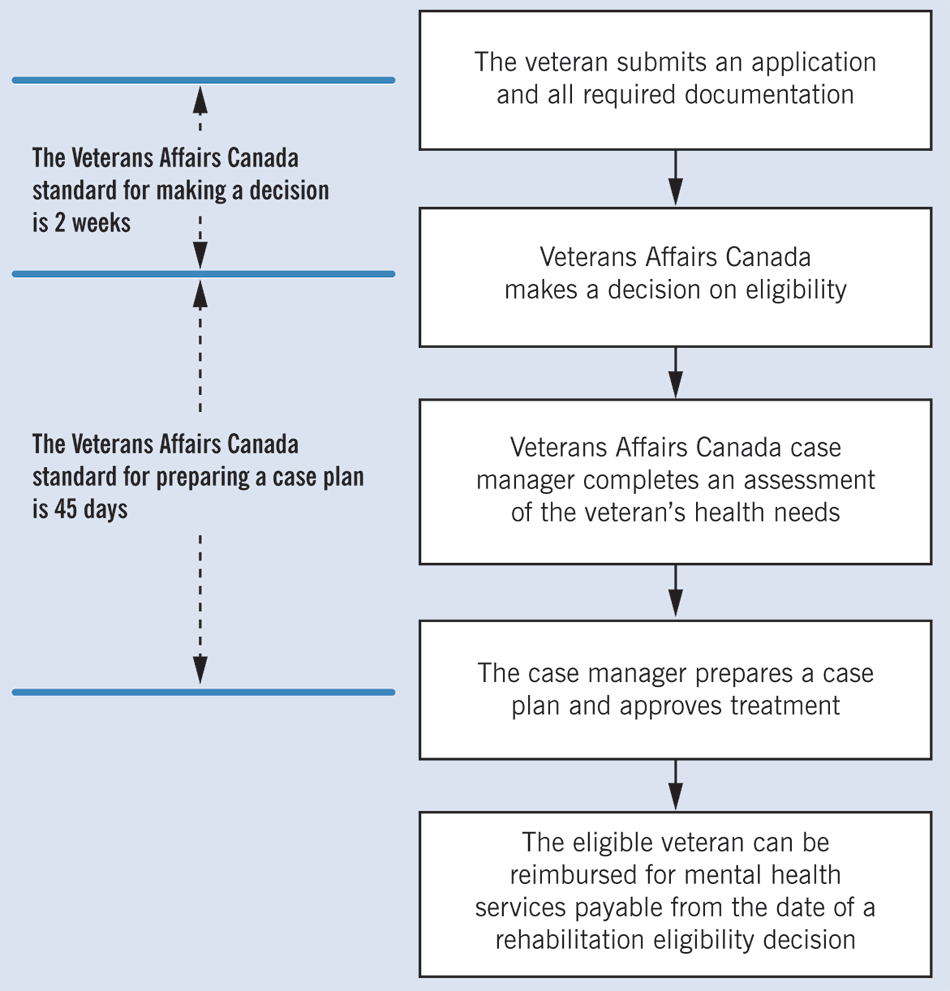

Exhibit 3.3—The Rehabilitation Program application process

The Rehabilitation Program application process involves the following steps:

- The veteran submits an application and all required documentation.

- Veterans Affairs Canada makes a decision on eligibility. The Department’s standard for making a decision is two weeks. Note that in its documentation, Veterans Affairs Canada expresses its service standards in weeks for making an eligibility decision and in days for assessing a veteran and preparing a case plan.

- For eligible veterans,

- The Veterans Affairs Canada case manager completes an assessment of the veteran’s health needs.

- The case manager prepares a case plan and approves treatment. The Veterans Affairs Canada standard for preparing a case plan is 45 days after the decision on eligibility.

- The eligible veteran can be reimbursed for mental health services payable from the date of a rehabilitation eligibility decision.

Note: In its documentation, Veterans Affairs Canada expresses its service standards in “weeks” for making an eligibility decision and in “days” for assessing a veteran and preparing a case plan.

Source: Information obtained from Veterans Affairs Canada's published service standards and internal documentation.

(Return)

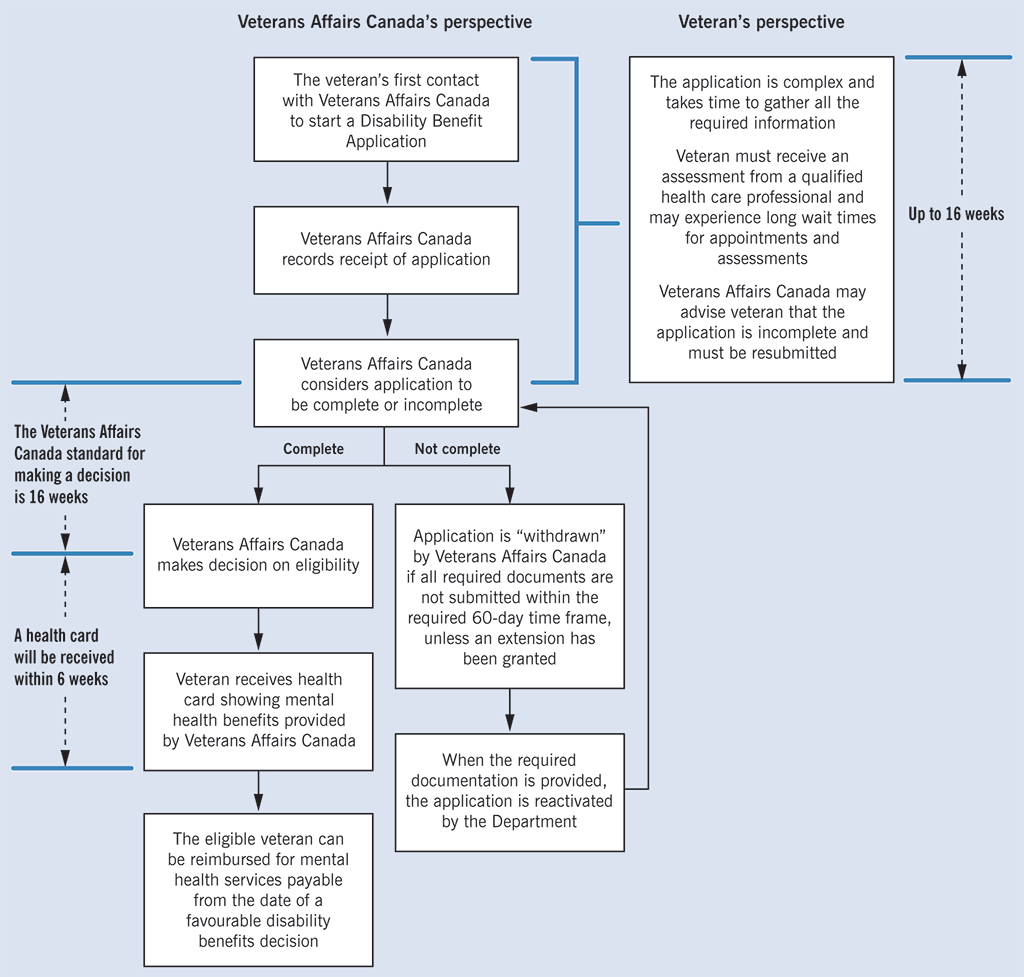

Exhibit 3.4—The Disability Benefits Program application process

This chart shows the Disability Benefits Program application process from Veterans Affairs Canada’s perspective and from the veteran’s perspective.

The process from Veterans Affairs Canada’s perspective is as follows:

- The veteran’s first contact with Veterans Affairs Canada is to start a Disability Benefit Application.

- Veterans Affairs Canada records receipt of the application.

- Veterans Affairs Canada considers the application to be either complete or incomplete.

- If Veterans Affairs Canada considers the application to be complete, it makes a decision on eligibility. The Veterans Affairs Canada standard for making a decision is 16 weeks.

- Next, the veteran receives a health card showing mental health benefits provided by Veterans Affairs Canada. A health card will be received within six weeks.

- Then the eligible veteran can be reimbursed for mental health services payable from the date of a favourable disability benefits decision.

- If Veterans Affairs Canada considers the application to be incomplete, the application is withdrawn by Veterans Affairs Canada if all required documents are not submitted within the required 60-day timeframe, unless an extension has been granted.

- When the required documentation is provided, the application is reactivated by the Department. Veterans Affairs Canada then makes the decision on eligibility.

The Disability Benefits Program application process from the veteran’s perspective is as follows:

- The application is complex and takes time to gather all the required information.

- The veteran must receive an assessment from a qualified health care professional and may experience long wait times for appointments and assessments.

- Veterans Affairs Canada may advise the veteran that the application is incomplete and must be resubmitted.

- From the veteran’s perspective, the application can take up to 16 weeks to submit, before Veterans Affairs Canada starts its time frame to make a decision.

Sources: Based on information obtained from Veterans Affairs Canada’s published service standards and internal documentation, and from Veterans Affairs Canada’s Client Service Delivery Network system for disability applications for the 2013–14 fiscal year.

(Return)

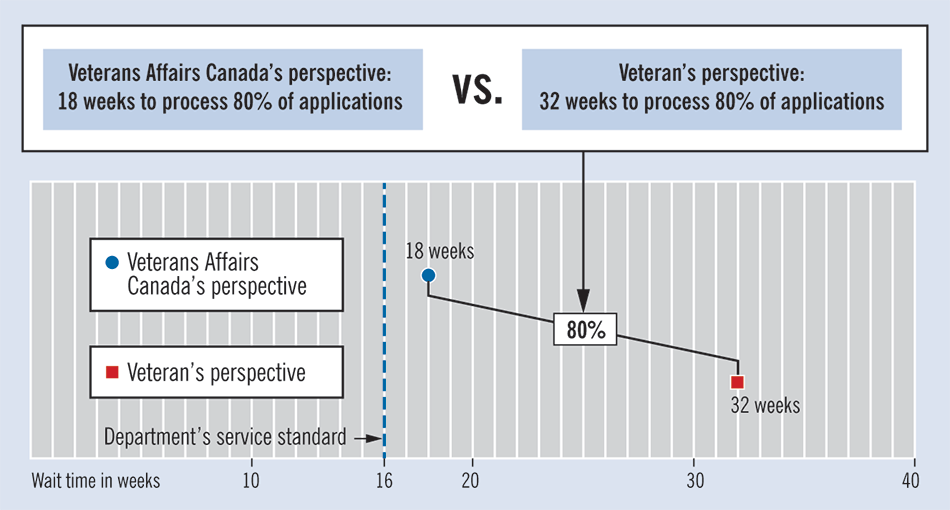

Exhibit 3.5—Veterans Affairs Canada and veterans have different perspectives on the time it takes to make a decision on eligibility for disability benefits

From Veterans Affairs Canada’s perspective, it takes 18 weeks to process 80 percent of applications. The Department’s service standard is 16 weeks.

From the veteran’s perspective, it takes 32 weeks to process 80 percent of applications.

Source: Based on data obtained from Veterans Affairs Canada’s Client Service Delivery Network system for disability applications for the 2013–14 fiscal year.

(Return)

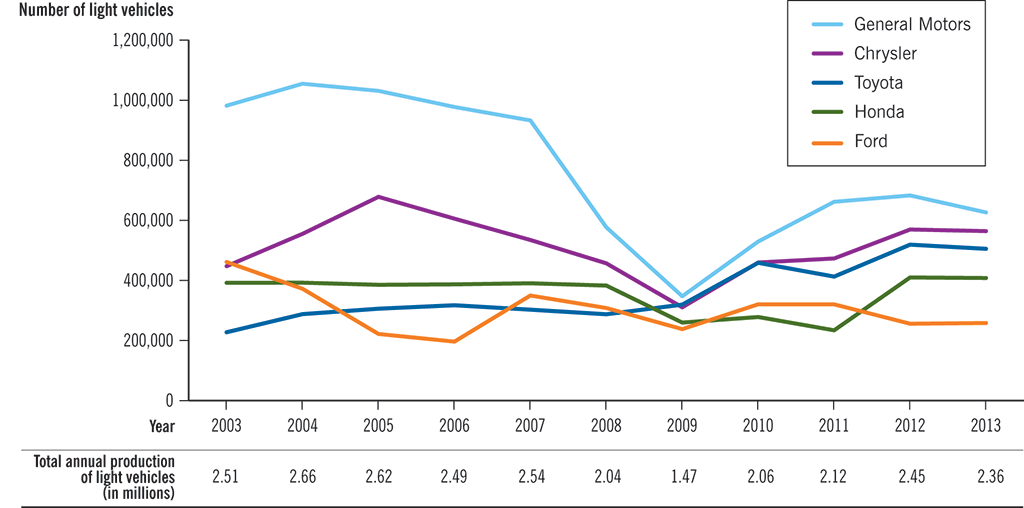

Exhibit 5.1—Production of light vehicles in Canada, 2003-2013

The graph shows the numbers of light vehicles produced annually in Canada from 2003 to 2013 by General Motors, Chrysler, Toyota, Honda, and Ford.

Between 2003 and 2009, the production of all manufacturers declined, except for that of Toyota, which continued to increase. Since 2009, the production increased for all manufacturers, but the total production is still lower than what it was in 2003.

The exhibit also lists the total numbers of light vehicles that were produced annually in Canada between 2003 to 2013.

| Year | Total annual production of light vehicles (in millions) |

|---|---|

| 2003 | 2.51 |

| 2004 | 2.66 |

| 2005 | 2.62 |

| 2006 | 2.48 |

| 2007 | 2.51 |

| 2008 | 2.01 |

| 2009 | 1.48 |

| 2010 | 2.05 |

| 2011 | 2.10 |

| 2012 | 2.44 |

| 2013 | 2.36 |

Source: WardsAuto

(Return)

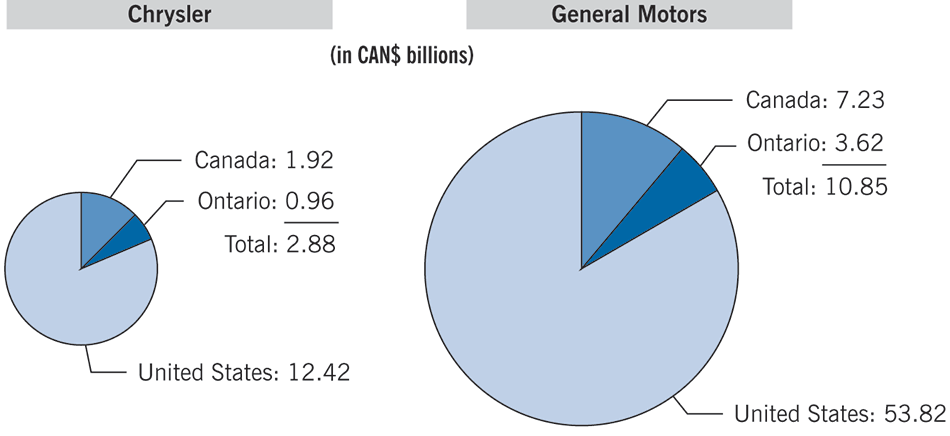

Exhibit 5.2—Canada and Ontario contributed $13.7 billion to Chrysler and General Motors in 2009

Two pie charts show the amounts of financial assistance, in Canadian dollars, provided to Chrysler and General Motors in 2009 by Canada, Ontario, and the United States.

The amounts to Chrysler consisted of $1.92 billion from Canada and $0.96 billion from Ontario (totalling $2.88 billion), and $12.42 billion from the United States.

The amounts to General Motors consisted of $7.23 billion from Canada and $3.62 billion from Ontario (totalling $10.85 billion), and $53.82 billion from the United States.

Canada and Ontario contributed a total of $13.7 billion to the companies in 2009.

Note: Amounts for the United States have been converted to Canadian dollars. The U.S. Government Accountability Office listed these amounts as US$10.4 billion for Chrysler and US$49.5 billion for General Motors.

Sources: Data from Public Accounts of Canada, 2009–10 and the U.S. Government Accountability Office

(Return)

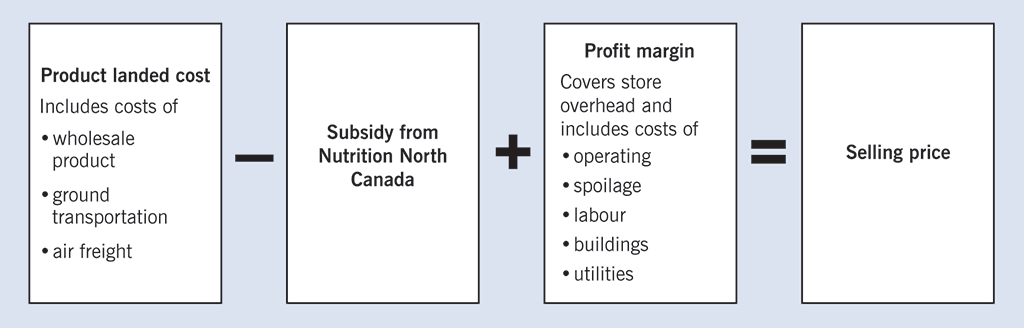

Exhibit 6.1—Information needed to determine whether the full subsidy is passed on to consumers

This chart shows the information needed to determine whether the full subsidy is passed on to consumers. The product landed cost minus the subsidy from Nutrition North Canada plus the profit margin equals the selling price.

The product landed cost includes the costs of the wholesale product, ground transportation, and air freight.

The subsidy is from Nutrition North Canada.

The profit margin covers the store overhead and includes the costs of operating, spoilage, labour, buildings, and utilities.

(Return)

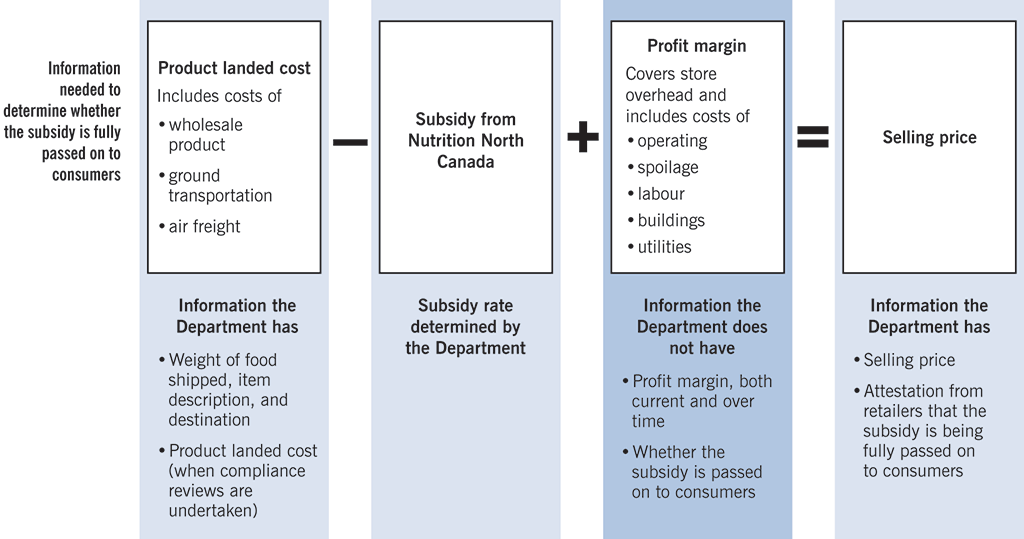

Exhibit 6.2—The Department does not collect information on profit margins from retailers

This chart shows the information the Department does and does not have in order to determine whether the subsidy is fully passed on to consumers.

The Department needs to know the product landed cost, the subsidy from Nutrition North Canada, the profit margin, and the selling price. The product landed cost minus the subsidy from Nutrition North Canada plus the profit margin equals the selling price.

The product landed cost includes the costs of the wholesale product, ground transportation, and air freight. Regarding the product landed cost, the information the Department has is the weight of food shipped, item description, and destination, as well as the product landed cost, when compliance reviews are undertaken.

The subsidy is from Nutrition North Canada. The subsidy rate is determined by the Department.

The profit margin covers the store overhead and includes the costs of operating, spoilage, labour, buildings, and utilities. Regarding the profit margin, the information the Department does not have is the profit margin, both current and over time, and whether the subsidy is passed on to consumers.

Regarding the selling price, the information the Department has is the selling price and attestation from retailers that the subsidy is being fully passed on to consumers.

(Return)