2015 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada Report 6—Preparing Male Offenders for Release—Correctional Service Canada

2015 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada Report 6—Preparing Male Offenders for Release—Correctional Service Canada

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- List of Recommendations

- Exhibits:

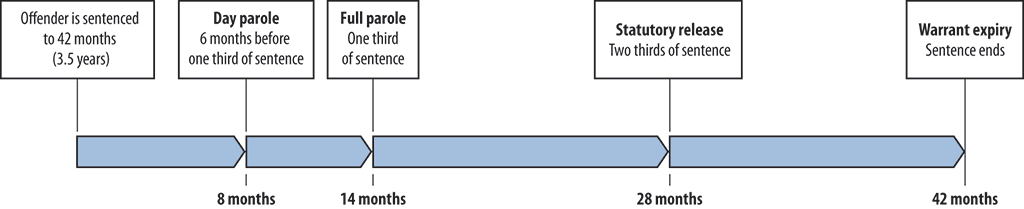

- 6.1—Offenders are eligible for release before the end of their sentence

- 6.2—In the 2013–14 fiscal year, the majority of offenders were first released from penitentiary at their statutory release date

- 6.3—Offenders released on parole are less likely to be convicted of a violent offence before their sentence ends than offenders on statutory release

- 6.4—Most offenders completed their correctional programs in the 2013–14 fiscal year

- 6.5—Key documents were often not obtained before Correctional Service Canada (CSC) completed assessments of offenders’ security level and developed correctional plans

Performance audit reports

This report presents the results of a performance audit conducted by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada under the authority of the Auditor General Act.

A performance audit is an independent, objective, and systematic assessment of how well government is managing its activities, responsibilities, and resources. Audit topics are selected based on their significance. While the Office may comment on policy implementation in a performance audit, it does not comment on the merits of a policy.

Performance audits are planned, performed, and reported in accordance with professional auditing standards and Office policies. They are conducted by qualified auditors who

- establish audit objectives and criteria for the assessment of performance;

- gather the evidence necessary to assess performance against the criteria;

- report both positive and negative findings;

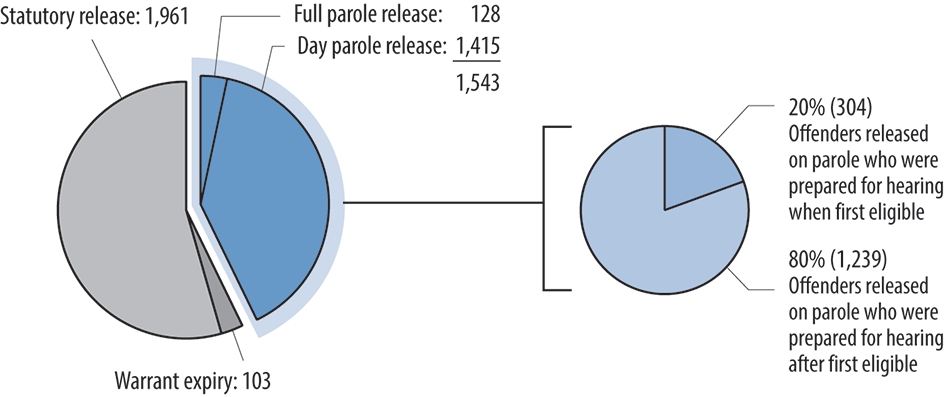

- conclude against the established audit objectives; and

- make recommendations for improvement when there are significant differences between criteria and assessed performance.

Performance audits contribute to a public service that is ethical and effective and a government that is accountable to Parliament and Canadians.

Introduction

Background

6.1 The mission of Correctional Service Canada (CSC) is to “contribute to public safety by actively encouraging and assisting offenders to become law-abiding citizens, while exercising reasonable, safe, secure, and humane control.” One of CSC’s main legislated responsibilities is to assist the reintegration of offenders into the community.

6.2 To support this reintegration, CSC provides correctional interventions for offenders who are in custody or under supervision in the community. In the 2013–14 fiscal year, an average of 14,550 male offenders were in custody in penitentiaries, and another 7,500 male offenders were supervised in the community until the end of their sentence.

6.3 In the 2013–14 fiscal year, CSC spent about $531 million, or 20 percent of its annual expenditures, on programs to rehabilitate offenders. Correctional programs are designed to reduce an offender’s risk to reoffend; they address criminal behaviours involving violence, substance abuse, and sexual abuse. Other programs are intended to improve offenders’ level of education and employability skills. Aboriginal males account for about 23 percent of male offenders in custody and may be referred to correctional programs that have culturally appropriate content and methods to address their risk to reoffend.

6.4 Under the Corrections and Conditional Release Act, offenders may serve part of their sentence under supervision in the community after serving part of their sentence in custody. Most offenders serving fixed-term sentences are eligible to be released (at statutory release) after serving two thirds of their sentence in custody. All offenders must be considered for some form of conditional release after serving one third of their sentence in custody. Conditional release, or parole, means that the offender may serve the remainder of the sentence in the community under CSC supervision, with specific conditions. CSC assesses whether an offender would be a good candidate for release on parole and provides this information to the Parole Board of Canada (Parole Board). Considerations include the offender’s assessed risk to reoffend and the extent to which that risk can be managed in the community. The Parole Board decides whether parole will be granted to an offender and sets the conditions of that release (Exhibit 6.1).

Exhibit 6.1—Offenders are eligible for release before the end of their sentence *

* Shown for a sentence of 3.5 years, the average sentence length for male offenders admitted into federal custody in the 2013–14 fiscal year. Does not include offenders serving life sentences.

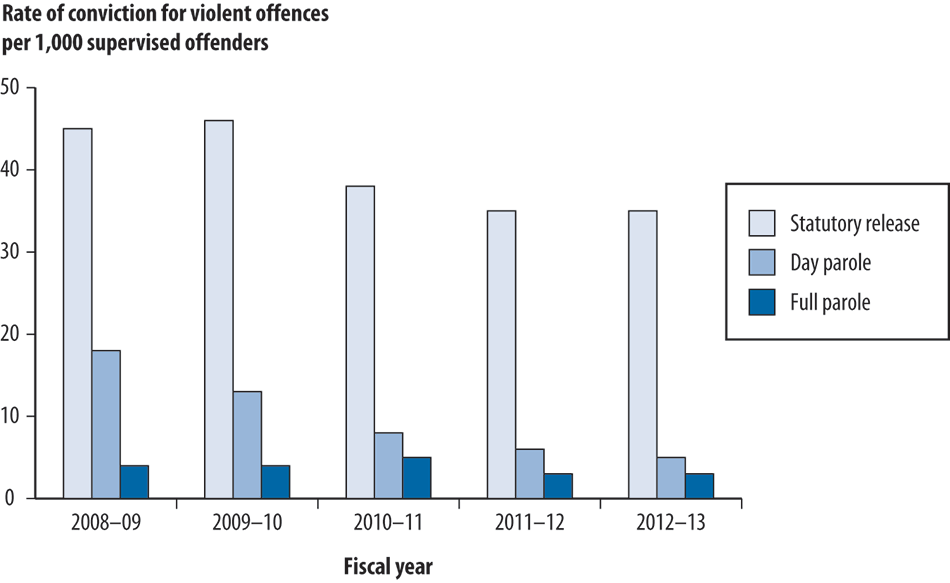

6.5 Federal offenders may be released from a penitentiary to serve the remainder of their sentence under supervision in the community under day parole, full parole, or statutory release. Day parole and full parole are both granted at the discretion of the Parole Board. Day parole allows offenders to participate in community activities during the day, but requires that they return to a halfway house or correctional facility in the evening. Full parole allows offenders to serve the remainder of their sentence in the community. Statutory release refers to the legal requirement that offenders must be released after serving two thirds of their sentence in custody. In exceptional circumstances, offenders who pose a threat for serious harm and violence may be held in custody until warrant expiry, when their sentence ends.

6.6 CSC can influence the length of time an offender remains in custody by providing correctional interventions, such as rehabilitation and education programs, designed to reduce the offender’s risk to public safety. The average length of most sentences served in federal penitentiaries is less than four years. Rehabilitation efforts while an offender is in custody can reduce the likelihood that the individual will reoffend after release and be returned to a penitentiary. Therefore, providing timely access to correctional interventions can protect public safety and help to manage the number of offenders in custody.

6.7 Two recent amendments to the Act have had an impact on the time by which offenders may be recommended for release on parole. In March 2011, the Act was amended to abolish Accelerated Parole Review, a form of early release available to non-violent, first-time offenders after one sixth of their sentence had been served. Most offenders who qualified for this form of early release were assessed as a low risk to reoffend. As a result of this amendment, offenders may apply only for day or full parole, which is available at a later point in their sentence than was possible with an accelerated parole review. In March 2012, an additional amendment to the Act extended the waiting period for a parole eligibility hearing after an offender was denied parole—this waiting period was extended from 6 months to 12 months.

Focus of the audit

6.8 This audit focused on the timely delivery of correctional interventions to offenders in custody to prepare offenders for safe release into the community. This audit is important because Correctional Service Canada is mandated to assist offenders to successfully reintegrate into the community.

6.9 We examined offender release rates from March 2011, to exclude the impact of the abolition of accelerated parole review on these trends. We did not examine the preparation of Aboriginal or women offenders for release, or interventions provided to offenders supervised in the community.

6.10 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Assessing when to recommend offenders for early release

6.11 Overall, we found that Correctional Service Canada (CSC) officials made fewer recommendations for early release to the Parole Board of Canada (Parole Board) in the 2013–14 fiscal year than in the 2011–12 fiscal year. This was the case even for offenders who had been assessed as a low risk to reoffend. As a result, lower-risk offenders were released later in their sentence and had less time supervised in the community before their sentence ended.

6.12 This is important because the more time offenders have to gradually reintegrate into the community under CSC supervision before the end of their sentence, the more likely they are to reintegrate successfully. Furthermore, CSC data consistently shows that low-risk offenders who serve longer portions of their sentence in the community have more positive reintegration results. As such, the supervised release of offenders who have demonstrated responsibility to change contributes to public safety and the successful reintegration of offenders into the community. There are also significant costs to longer periods of incarceration, as it is three times more costly to hold an offender in custody than to supervise him in the community.

6.13 The purpose of conditional release is to contribute to public safety by releasing offenders at a time and in a manner that increases their chances of successful reintegration into the community. Prior to an offender’s parole eligibility date, CSC officials prepare an assessment of the offender’s progress while in the institution, and provide a recommendation as to whether the offender should be granted or denied parole. At all times, public safety remains CSC’s primary consideration. CSC’s recommendations for release correlate strongly with the Parole Board’s decisions to grant parole; few offenders are granted parole without a supportive recommendation from CSC officials. During the 2013–14 fiscal year, 86 percent of CSC recommendations for early release on day parole were granted by the Parole Board.

6.14 In determining whether an offender may be granted parole, the Parole Board considers whether the offender is likely to reoffend or present an undue risk to society before the end of his sentence. The Parole Board also considers whether the release of the offender will contribute to the protection of society by facilitating his reintegration into society as a law-abiding citizen.

Eighty percent of offenders were incarcerated beyond their first parole eligibility date

6.15 In the 2013–14 fiscal year, we found that only a small portion of offenders (20 percent) had their cases prepared for a parole hearing by the time they were first eligible. As well, the majority of offenders (54 percent) were first released from a penitentiary at their statutory release date, rather than on parole at an earlier point in their sentence.

6.16 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

6.17 This finding matters because CSC is responsible for the safe reintegration of offenders into the community and for managing its costs. Parole supervision has consistently been shown to be an essential component of offenders’ successful reintegration to the community, particularly for medium- and high-risk offenders. In addition, it is about three times more costly to hold offenders in custody than to supervise them in the community.

6.18 The delay or cancellation of parole reviews can reduce the time that offenders may benefit from supervision in the community before their sentence expires and can hinder their safe reintegration into the community. CSC studies show that offenders released on day or full parole had lower rates of reoffending before their sentence expired than those released at their statutory date. These studies also indicate that most low-risk offenders could be safely managed in the community, and had a low likelihood of reoffending when they were released.

6.19 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 6.33 and 6.34.

6.20 What we examined. We examined whether CSC ensured that complete and timely reports on offenders’ readiness for release were provided to the Parole Board by their first parole eligibility date. We reviewed CSC data on the number of non-Aboriginal male offenders released from penitentiaries over the past three fiscal years by security level. We compared the actual release date to the dates when offenders were first eligible for release.

6.21 Offender releases on parole. In the 2013–14 fiscal year, we found that 1,543 offenders were first released on either day or full parole, accounting for 43 percent of all those first released from custody (Exhibit 6.2). However, fewer offenders were recommended for parole at their earliest eligibility date. Only 20 percent of offenders had their cases prepared for a parole hearing by their first eligibility date in the 2013–14 fiscal year, compared to 26 percent in the 2011–12 fiscal year.

Exhibit 6.2—In the 2013–14 fiscal year, the majority of offenders were first released from penitentiary at their statutory release date

6.22 We also found that, of the 1,950 low-risk offenders first released in the 2013–14 fiscal year, 1,149 were released on parole. However, 20 percent of these low-risk offenders had their cases prepared for parole hearings when they were first eligible. On average, these offenders were first released on parole about eight months after the date that they were first eligible. Moreover, we found that 39 percent of low-risk offenders were first released from custody at their statutory date rather than on either day or full parole by the Parole Board.

6.23 We found that offenders had increasingly waived or postponed their full parole hearings before the Parole Board. In the 2013–14 fiscal year, 65 percent did so—an increase of 9 percentage points since the 2011–12 fiscal year. Under the Corrections and Conditional Release Act, offenders have the right to a hearing before the Parole Board at the date they are eligible for full parole. Offenders may choose to waive or postpone hearings for their own reasons. However, delaying a hearing may also be due to the inability of CSC to complete an offender’s casework in time.

6.24 Custody costs. We found that the slowing rate of offender releases had been contributing to capacity pressures across institutions and increasing custody costs. Although the crime rate has decreased, and new admissions into federal custody have not increased, the total male offender population grew by 6 percent, from an average of 13,750 offenders in the 2010–11 fiscal year to an average of 14,550 offenders in the 2013–14 fiscal year, largely due to offenders now serving longer portions of their sentences in custody. Since March 2011, CSC costs of custody have increased by $91 million because of increased numbers of offenders in custody.

6.25 We also found that low-risk offenders accounted for about half (49 percent) of those staying in custody longer. Based on CSC’s average cost of maintaining an offender in custody and in the community, about $26 million in custody costs could have been avoided in the 2013–14 fiscal year if low-risk offenders held in minimum-security institutions had been prepared for, and released by, their first parole eligibility date. According to CSC officials, it is good correctional practice to prepare low-risk offenders for release by their first parole eligibility date, as normally they can be safely managed in the community.

More offenders are being released directly from medium- and high-security penitentiaries

6.26 We found that the majority of offenders (54 percent) were first released from custody at their statutory release date in the 2013–14 fiscal year. Most of these offenders entered the community directly from medium- and maximum-security penitentiaries, limiting their ability to benefit from gradual and supervised release that supports safe reintegration.

6.27 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

6.28 This finding matters because CSC is responsible for the safe reintegration of offenders into the community. CSC data indicates that offenders released at statutory release generally have higher levels of violent reoffending before their sentence ends than those released earlier on parole.

6.29 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 6.33 and 6.34.

6.30 What we examined. We examined when offenders were first released from penitentiaries and their type of release. We examined the level of security for these offenders, as well as their assessed risk to reoffend.

6.31 Statutory releases by security level. Under the Act, CSC is required to release offenders at their statutory release date unless it has reasonable grounds to believe that an offender is likely to commit an offence causing serious harm. In the 2013–14 fiscal year, about 2,000 offenders were first released from custody at their statutory date. Of this number, 64 percent were released from medium-security penitentiaries, and 11 percent were released from maximum-security penitentiaries.

6.32 Offenders first released at their statutory release date from maximum- and medium-security levels do not receive the full benefit of a planned, gradual release into the community. Parole Board data indicates that offenders released on parole generally have lower levels of violent reoffending before their sentence expires than those released at their statutory date (Exhibit 6.3). CSC assesses which offenders may be recommended for early release on parole based on the progress each offender has made on his correctional plan, his overall behaviour, and his potential to be safely supervised in the community. However, CSC policy does not require that offenders at higher levels of security be assessed for a transfer to a lower level before their statutory release date, as a way to support their safe reintegration into the community.

Exhibit 6.3—Offenders released on parole are less likely to be convicted of a violent offence before their sentence ends than offenders on statutory release

6.33 Recommendation. Correctional Service Canada should investigate the reasons for the increases observed in the waivers and postponements of parole hearings, particularly by offenders assessed as low risk.

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada will undertake a systematic and comprehensive review of the reasons for waivers and postponements of parole hearings, particularly by offenders assessed as low risk—by July 2015.

6.34 Recommendation. Correctional Service Canada should assess the risks associated with offenders being released directly into the community from medium- and maximum-security institutions.

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada will conduct a study on the risks associated with releasing offenders directly to the community from medium- and maximum-security institutions—by December 2015.

Delivering correctional programs

6.35 Overall, we found that Correctional Service Canada (CSC) has improved the timeliness of delivering correctional programs to offenders in custody. However, many offenders—about 65 percent in the 2013–14 fiscal year—still did not complete their programs before they were first eligible for release. We also found that many low-risk offenders were not referred to correctional programs while in custody, despite having identified risks to reoffend. CSC had not developed tools to objectively assess the benefits of other correctional interventions—such as employment and education programs, and interactions with institutional parole officers—in preparing offenders for release.

6.36 This is important because CSC can influence the successful reintegration of offenders through the timely delivery of correctional programs. CSC analysis indicates that offenders who participate in correctional programs during their time in custody are less likely to reoffend upon release.

6.37 To support the successful reintegration of offenders into the community, CSC provides a range of correctional programs that target criminal behaviour. The traditional suite of correctional programs (general crime prevention programs, violence prevention programs, family violence prevention programs, and sex offender programs) was developed in the 1990s. CSC studies have shown them to be effective in reducing rates of reoffending.

6.38 In January 2010, CSC introduced an updated version of its correctional programs, primarily to improve the timeliness of delivery, particularly for offenders serving short sentences. The new model addresses multiple and overlapping areas of criminality. The programs have been piloted in two regions, and have been approved for delivery in all institutions by May 2017.

Timeliness in the delivery of correctional programs has improved, but this has not led to earlier release

6.39 We found that CSC has improved the timeliness of delivering its correctional programs to many offenders. The successful completion of correctional programs is a key factor in determining whether offenders may be recommended for early release on parole. We found, however, that while more offenders were completing their correctional programs by their first parole eligibility date, they were not recommended for earlier release on parole.

6.40 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

6.41 This finding matters because even minor delays in moving offenders through their assigned correctional programs can lead to delays in parole hearings.

6.42 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 6.74.

6.43 What we examined. We examined whether CSC provided the required correctional programs to offenders to support their timely reintegration. We reviewed CSC data on non-Aboriginal male offenders in custody to determine which correctional programs and other interventions were delivered to offenders and when they were delivered.

6.44 Correctional programs. In the 2013–14 fiscal year, CSC spent $16 million to deliver correctional programs to male offenders. These programs target the criminal behaviour of offenders. CSC studies indicate that they are effective in reducing rates of reoffending, particularly for higher-risk offenders. Exhibit 6.4 shows enrollment and completion rates for correctional programs, as well as for education and employment programs, in the 2013–14 fiscal year.

Exhibit 6.4—Most offenders completed their correctional programs in the 2013–14 fiscal year

| Correctional intervention | Number of offenders enrolled | Percentage of offenders with successful completions |

|---|---|---|

| Correctional programs | ||

| Violence prevention | 1,270 | 72% |

| Substance abuse | 1,354 | 84% |

| Family violence | 326 | 84% |

| Sex offender | 529 | 83% |

| Updated programs | 3,044 | 86% |

| Total | 6,523 | 78% |

| Education programs | 11,434 | Not applicable * |

| Employment programs | 4,218 | Not applicable * |

* Correctional Service Canada has not established performance measures for successful participation in education or employment programs.

Source: Correctional Service Canada, unaudited numbers

6.45 CSC recognizes that the timely delivery of correctional programs is crucial to support offenders’ safe reintegration. In 2010, its correctional programs were updated to improve the timeliness of delivery so that more offenders could complete them by the time they were eligible for release on parole. CSC has committed to implementing the new programs in all institutions by May 2017. It will also conduct ongoing evaluations of the programs’ effectiveness in reducing rates of reoffending.

6.46 We found that more higher-risk offenders were being referred to correctional programs: 90 percent of medium- and high-risk offenders were referred to a correctional program in the 2013–14 fiscal year, an increase of 7 percentage points from the 2011–12 fiscal year. We also found high rates of completion among offenders who were referred to a correctional program: 90 percent of offenders released in the 2013–14 fiscal year had completed a correctional program. However, the majority of offenders, about 65 percent in the 2013–14 fiscal year, did not complete their programs before they were first eligible for release.

6.47 Timely access to correctional programs is particularly important for offenders serving sentences of four years or less, as many of them are eligible for parole within one year of being admitted to a penitentiary. We found that, overall, more offenders serving short-term sentences were able to complete their programs before their full parole eligibility date in the 2013–14 fiscal year than was the case in the 2009–10 fiscal year, when CSC introduced its updated correctional programs. In regions where the updated correctional programs were delivered, 23 percent more offenders completed their programs by their full parole eligibility date than in other regions in the 2013–14 fiscal year.

6.48 However, despite these improvements in the timely delivery of correctional programs, we found that offenders serving sentences of four years or less are not recommended for release on parole any earlier than they had been in the past. As well, for offenders first released in the 2013–14 fiscal year, we found that those who completed the new correctional programs were released at about the same point in their sentence, on average, as offenders who completed the traditional suite of programs at later points in their sentence.

6.49 Security reassessments. Although CSC directives do not require offenders to have their security levels reassessed within three months of successfully completing a correctional program, we found that this was done for 31 percent of offenders during the 2013–14 fiscal year. According to CSC policy, an offender must have his security classification reviewed at least once every two years to assess if he may be placed at a lower level of custody. A review may also be made earlier at the discretion of the parole officer, based on an offender’s behaviour. The successful transfer of an offender to a lower security level can demonstrate his progress and reintegration potential. Also, an offender is more likely to be granted day or full parole from lower-security penitentiaries.

Correctional Service Canada does not clearly demonstrate how interventions prepare low-risk offenders for release

6.50 We found that CSC guidelines did not clearly demonstrate how interventions available to low-risk offenders prepare them for safe reintegration.

6.51 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

- access to correctional interventions,

- work releases,

- parole officer contacts, and

- preparation for first release.

6.52 This finding matters because CSC is mandated to support the timely reintegration of all offenders in custody, including low-risk offenders. But many low-risk offenders remained in custody past their first parole eligibility date, resulting in increased custody costs compared to the cost of supervision in the community, potentially affecting their safe reintegration.

6.53 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 6.74.

6.54 What we examined. We examined whether CSC provided the required correctional interventions to offenders to support their reintegration. We reviewed CSC policy directives for referring offenders to correctional interventions and assessing their impact. We also analyzed CSC data on offender releases and participation in correctional programs for non-Aboriginal male offenders.

6.55 Access to correctional interventions. CSC refers offenders to correctional programs based on their assessed risk to reoffend—those with a higher risk are more likely to be assigned to a program. We found that 32 percent of 3,600 offenders first released during the 2013–14 fiscal year had not been assigned to a correctional program during their time in custody. In 2009, CSC changed its referral guidelines to no longer offer correctional programs to low-risk offenders, as its correctional programs were demonstrated to be most effective in reducing rates of reoffending among higher-risk offenders.

6.56 CSC recognizes that, apart from correctional programs, other interventions, such as employment or education programs, can also help offenders demonstrate their potential for early release. However, we found that CSC has not established clear guidelines for referring offenders to other interventions that may contribute to their successful release.

6.57 Work releases. We found that the use of work releases varied across regions and has declined overall in each of the past three fiscal years. Only 470 work releases were issued to offenders in the 2013–14 fiscal year, a decline of 29 percent from the previous year. A work release is a permit to leave the penitentiary and enter the community on a temporary basis for work purposes prior to the date an offender is eligible for parole. This type of temporary release is authorized by the warden and may be used to demonstrate that an offender is ready for reintegration into the community.

6.58 Parole officer contacts. We found a high variation in the number of face-to-face visits between institutional parole officers and offenders. Parole officers working with offenders in custody are responsible for assisting in their reintegration. In the 50 casework files we examined for offenders serving sentences of four years or less, we found that parole officers did not meet more regularly with high-risk offenders than with lower-risk offenders. For example, a high-risk offender in our sample met with his institutional parole officer once upon admission and then waited about 17 months for the next meeting, which occurred within 21 days of his statutory release. However, a low-risk offender in our sample met with his parole officer a total of four times during his 11 months in custody, with just over 6 months between two of the visits.

6.59 CSC guidelines do not specify the required frequency of an institutional parole officer’s face-to-face visits with an offender, based on the assessed risk of the offender. We noted that offender contact guidelines exist for parole officers supervising offenders in the community. These guidelines specify that parole officers are required to meet more frequently with higher-risk offenders.

6.60 Preparation for first release. CSC officials told us that it is good correctional practice to prepare the cases of low-risk offenders for parole hearings by their first eligibility date, as normally they can be safely supervised in the community. In our review of 50 casework files for offenders released in the 2013–14 fiscal year, 26 offenders were assessed as low risk to reoffend. We found that few of these low-risk offenders were recommended for release when they were first eligible:

- 7 of 26 offenders were recommended for a day parole hearing within one month of their first parole eligibility date, and 6 of these were granted day parole;

- 13 of 26 offenders had their cases prepared for a day parole hearing more than one month after the date that they were first eligible, often being granted day parole after they were eligible for full parole; and

- 6 of 26 offenders were released at their statutory release date. Four of these 6 offenders had waived their full parole eligibility hearing.

6.61 We found that the determination of when offenders should be recommended for early release was based largely on the parole officer’s judgment. However, CSC has limited guidance and tools available to support the parole officer to make an objective assessment of the impact of interventions on an offender’s progress toward safe reintegration, particularly for low-risk offenders.

6.62 CSC has identified the need to improve training for parole officers and their managers, due to weaknesses it found in the quality of offender assessments prepared by parole officers. We found that CSC has yet to develop case management training for parole officers that will address identified performance gaps. Further, managers of parole officers do not receive training on how to perform their important quality management role.

Delivery of employment and education programs is not targeted or timely

6.63 We found that CSC’s employment programs were not targeted to those with the greatest need to improve their skills. Only 5 percent of the offenders participating in employment programs were assessed as having a high need to improve their employability skills. Another 42 percent of employed offenders were assessed with a medium need. CSC has not developed guidelines to prioritize the timely delivery of its employment programs to offenders. We also found that many offenders have improved their level of education while in custody, but they waited an average of five months before starting education programs, potentially limiting the progress they could have made.

6.64 Our analysis to support this finding presents what we examined and discusses

6.65 This finding matters because CSC has identified that most offenders in custody need help to develop skills for future employment. CSC research indicates that interventions to improve offenders’ education and employability skills can promote employment placement in the community and improve offenders’ chances of success upon release.

6.66 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 6.74.

6.67 What we examined. We examined whether offenders in custody received the education and employment programs identified in their correctional plans in a timely manner. We examined guidelines for the provision of employment and education programs to male offenders in custody, as well as participation and completion rates upon release.

6.68 Employment programs. According to CSC data for the 2013–14 fiscal year, 74 percent of offenders in custody were assessed as needing to improve their employability skills. CORCAN is a special operating agency established in 1992 to provide offenders in penitentiaries with meaningful employment to improve their employability skills and chances for employment when they are released. CORCAN also runs vocational training programs within its institutions that allow offenders to earn certificates in areas such as workplace safety, first aid, and fall protection.

6.69 We found that CORCAN did not employ offenders with the greatest need to improve their employability skills. In May 2014, of the 1,071 offenders employed at CORCAN, only 52 had a high need and 454 had a medium need to improve their employability skills. Moreover, in October 2013, CSC eliminated incentive pay for offenders employed at CORCAN. Since then, few offenders have sought CORCAN employment. CORCAN officials estimated that their shops have operated at 57 percent capacity.

6.70 We also found that CSC had not yet developed a strategy or guidelines for delivering employment programs to offenders and targeting those offenders with the greatest need. Nor had it developed guidelines to prioritize the timely delivery of employment programs among other interventions. CSC studies suggest that its current employment programs improve the likelihood of offender employment upon release by about 9 percent, but CSC had not determined the minimum length or type of work experience needed to make a difference in offenders’ employability upon release.

6.71 Education programs. According to CSC data, 49 percent of offenders tested at an education level lower than Grade 8, and 71 percent tested at lower than Grade 10, upon admission to an institution. CSC guidelines offer all offenders the opportunity to upgrade their education to a Grade 12 level. In our review of 50 casework files for offenders released in the 2013–14 fiscal year, we found that 30 offenders were assigned to education programs and that they waited an average of five months before being enrolled. Of these 30 offenders, we found that 8 offenders advanced their education levels before their release.

6.72 CSC has not developed guidelines to prioritize the delivery of education programs among other interventions identified in offenders’ correctional plans. Nor did it have tools to objectively measure how improvements in offenders’ levels of education have addressed their assessed needs. We found that the number of offenders who upgraded their education before they were eligible for full parole has increased by about 11 percent since the 2011–12 fiscal year. However, it is not clear how CSC officials assessed the contribution of these improvements to offenders’ potential for early release.

6.73 CSC invests significant resources in its education and employment programs. In the 2013–14 fiscal year, CSC spent $17 million delivering employment programs and $19 million delivering education programs to male offenders. However, it has yet to develop assessment tools to demonstrate how these programs contribute to offenders’ progress toward safe reintegration.

6.74 Recommendation. Correctional Service Canada should develop guidelines to prioritize the timely delivery of its other correctional interventions, such as employment and education programs, to offenders, and structured tools to assess their impact on an offender’s progress toward safe reintegration into the community.

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada (CSC) has developed guidelines to prioritize the delivery of correctional interventions, and a structured tool will be available to staff by July 2015. Ongoing use and training on this tool will be completed by April 2016. CSC will implement tools to measure correctional plan performance and accountability by April 2017.

Determining offender risks upon admission into custody

6.75 Overall, we found that federal offenders were being assessed for their custody level and required correctional programs within required time frames upon admission, but these assessments are often based on limited information. In many cases, official documents, such as the offender’s updated criminal record, were not obtained by the time the intake assessment was completed.

6.76 This is important because Correctional Service Canada (CSC) is required to use objective and verifiable information to assess an offender’s custody level and correctional plan to ensure the accuracy of these assessments.

6.77 Under the Corrections and Conditional Release Act, CSC is required to assign a security classification of maximum, medium, or minimum to each offender admitted to its penitentiaries. In doing so, it considers the seriousness of the offence committed, the offender’s social and criminal history, and his potential for violent behaviour. CSC is also responsible for developing a correctional plan for each offender as soon as is practical after his admission to the penitentiary.

6.78 CSC completes an intake assessment for each offender admitted into custody to determine the appropriate penitentiary security level and correctional programs. In the 2013–14 fiscal year, intake assessments were completed for about 5,100 offenders admitted into federal custody. The policy requires that the assessment process be completed within 70 days of admission for offenders serving four years or less.

Key documents needed to assess offender risk are not defined

6.79 We found that CSC did not obtain key official documents before assessing offenders’ security level and developing a correctional plan. While CSC policy identifies a number of official documents that may be used to complete offenders’ intake assessments, such as police reports for current and previous criminal activities, it had not established which ones must be obtained, at a minimum, to ensure its intake assessment was accurate.

6.80 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

6.81 This finding matters because the assessment of an offender’s risk must be based on objective and verifiable information. It is important for CSC staff to know which official documents are required at a minimum to ensure the integrity of the offender’s intake assessment. Incomplete information could result in offenders being placed at an incorrect level of security, or not having their criminal risks addressed through correctional programs.

6.82 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 6.87 and 6.88.

6.83 What we examined. We examined whether CSC obtained needed information on offenders to complete intake assessments in a timely manner. We reviewed the documents identified by CSC officials as being needed to complete an accurate intake assessment and the timeliness of their completion.

6.84 Information needed to complete intake assessments. Under the Act, CSC is required to collect all relevant information on the offenders admitted into custody. However, we found no clear policy on which information is required at a minimum to properly assess an offender’s security level and prepare his correctional plan. CSC officials told us that certain documents should be used to ensure a reliable assessment of an offender’s risk at intake. These include the updated criminal record, judge’s comments upon sentencing, police reports, and Crown Attorney comments. Many of these documents must be requested from provincial authorities and prisons, and they can take several weeks to arrive at the federal penitentiary. CSC officials also have access to the national database of criminal records, but this may not provide a current record of all offences.

6.85 We found that intake assessments were being completed within required time frames. However, many intake assessments were completed even though key official documents were still outstanding (Exhibit 6.5). We also found that there was no requirement for updating the intake assessment after the official documents had been received. Parole officers at the institution where the offenders had been placed were not automatically alerted when official documents were finally received so that the appropriateness of the security level and correctional plan could be reviewed in a timely manner.

Exhibit 6.5—Key documents were often not obtained before Correctional Service Canada (CSC) completed assessments of offenders’ security level and developed correctional plans *

| Official document | Requested by CSC upon admission | All documents obtained by CSC upon completing intake assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Updated criminal record | 50% | 0% |

| Judge’s comments | 100% | 76% |

| Police reports | 100% | 74% |

| Crown Attorney’s comments | 46% | 36% |

* Based on a representative sample of 50 offender intake assessments completed from September to December 2013.

6.86 Furthermore, we found that CSC no longer had timely access to the updated criminal history for offenders in custody. In the past, the RCMP provided CSC with a complete and updated record of the offender’s criminal history. In October 2013, the RCMP stopped providing this service, which was not part of its mandate. As a result, CSC must now obtain this information directly from a variety of sources, increasing the risk that it will not have a complete and accurate criminal history to support its assessments.

6.87 Recommendation. Correctional Service Canada should clarify which documents are required, at a minimum, for the integrity of its initial assessment of an offender’s security level and the development of an appropriate correctional plan, and work with its partners to obtain these documents in a timely manner.

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada (CSC) will clarify, in policy, the minimum documentation required for efficient and effective offender assessments—by May 2015. CSC will liaise with other components of the criminal justice system to collect timely and relevant information—by July 2015.

6.88 Recommendation. Correctional Service Canada should strengthen the controls that it has in place to ensure that assessments of an offender’s security level and correctional plan are updated as soon as official documents are obtained for offenders in custody.

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada will ensure that an offender’s security level and correctional plan updates include all relevant information received after intake assessment—by July 2015.

Guidelines to demonstrate the impact of interventions on an offender’s identified risks are not clear

6.89 We found that offenders’ security levels were assessed using the Custody Rating Scale, but the rating was overridden in about 28 percent of security assessments completed during the 2013–14 fiscal year. The Custody Rating Scale determines the security level required for the custody of an offender—maximum, medium, or minimum.

6.90 We also found, during the review of a selection of 50 offender casework files, that five CSC officials who completed the security assessments were not certified to do so, as required by CSC policy.

6.91 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

6.92 This finding matters because an offender’s initial security placement affects the security of offenders and staff, as well as the offender’s potential for parole. The Custody Rating Scale was developed to mitigate the tendency of staff to overestimate offenders’ security risk, resulting in overclassification, which drives up the cost of incarcerating offenders and hinders their safe reintegration. Offenders are more likely to be granted parole from minimum security than from higher levels. A high number of overrides of security assessments indicates that officers, in applying their judgment, give more weight to some factors in assessing an offender’s security risk.

6.93 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 6.100 and 6.101.

6.94 What we examined. We examined the use of information to complete offender intake assessments. We reviewed how the Custody Rating Scale and statistical information on reoffending were used to complete the assessment of an offender’s custody level and refer him to correctional programs.

6.95 Overrides of security classifications. We found that corrections staff did not apply the rating recommended by the Custody Rating Scale in about 28 percent of all security assessments performed in the 2013–14 fiscal year. Of these overrides, 17 percent placed offenders into a higher level of custody, and 11 percent into a lower level. Our file review also confirmed a similar level of overrides when using the Custody Rating Scale. Notes on the offenders’ files indicated that the scale was overridden by staff based on their judgment of the offender’s security risk, considering factors such as his behaviour while in custody or access to correctional programs. We also found that 5 of the 40 officers who completed the assessments in our sample were not certified to use the tool, as required by CSC policy. Four of these officers had overridden the scale’s assessment.

6.96 According to CSC officials, the level of overrides should be about 15 percent of assessments. We found that management did not regularly monitor the number of overrides or take action to reduce their number, although it conducted a revalidation of the scale in 2011.

Static risk factors—Fixed aspects of an offender’s history that cannot be changed. Some examples are previous and current offences, severity of the offence, and age at first offence.

Dynamic risk factors—Characteristics that led to the offender’s behaviour that can change over time. Examples include criminal association, substance abuse, and unemployment.

6.97 Referrals to correctional programs. CSC referred offenders to correctional programs based on the likelihood that they would reoffend. This assessment was made using a static risk assessment tool based on historical facts about the offenders. If offenders were found to have a low risk to reoffend based on the assessment of static risk factors, they were unlikely to be provided with a correctional program, according to CSC referral guidelines. Offenders might also have dynamic risk factors identified in other assessments, but these were not explicitly considered in assigning correctional programs.

6.98 As a result, many offenders who are assessed with a low risk to reoffend may not be referred to a correctional program even if they are also identified with dynamic factors that affect their risk to reoffend. As well, offenders may be assessed as needing multiple programs, but the static assessment tool does not prioritize their assignment. We also note that the tool does not assist with reassessment of the offender’s potential for early release on parole once he has completed a correctional program.

6.99 We examined intake assessments for a selection of 50 offender casework files. We found that 15 of these offenders were assessed as low risk, and none was referred to a correctional program while in custody. However, 10 of these 15 offenders also had a dynamic risk identified in their assessment, such as criminal association or substance abuse. This risk was not included in developing the offenders’ correctional plans. We note that other jurisdictions, including several provinces, have been using tools that weigh both static and dynamic risks to assign correctional interventions and assess their impact.

6.100 Recommendation. Correctional Service Canada should monitor the use of the Custody Rating Scale to ensure that an offender’s security risks are appropriately weighted and officers are properly certified in its use.

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada (CSC) will create automated information reports to monitor Custody Rating Scale (CRS) usage at the national, regional, and local levels—by July 2015. CSC currently trains staff on the CRS and will strengthen parole officers’ induction training and deliver ongoing training by April 2016. In the interim, the results of monitoring will undergo management reviews at the operational level.

6.101 Recommendation. Correctional Service Canada should develop structured tools to assess both static and dynamic risk factors to prioritize the interventions assigned to offenders that are most likely to bring about positive change and support their timely reintegration.

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada (CSC) has already initiated work to ensure there is an evidence-based assessment of static and dynamic risk factors for each offender and to determine the types of correctional interventions that address criminal behaviour at the appropriate time in an offender’s sentence. As discussed as part of CSC’s response to the recommendation under paragraph 6.74, a structured tool will be available to staff by July 2015. Ongoing use and training on this tool will be completed by April 2016.

Conclusion

6.102 We concluded that Correctional Service Canada (CSC) provided correctional interventions to offenders in custody to support their rehabilitation and safe reintegration into the community, but did not ensure that these interventions were provided in a timely manner. Most offenders did not complete their programs by the time they were first eligible for release. Although CSC has improved the timeliness of delivering correctional programs to offenders, it has not ensured that offenders were assessed for earlier release on parole. CSC has not developed guidelines to prioritize the delivery of other correctional interventions, such as employment and education. Nor has it developed structured tools to objectively assess the impact of these interventions on reducing an offender’s risk to reoffend and his readiness for safe release.

About the Audit

The Office of the Auditor General’s responsibility was to conduct an independent examination of offender correctional programs at Correctional Service Canada to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs.

All of the audit work in this report was conducted in accordance with the standards for assurance engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance. While the Office adopts these standards as the minimum requirement for our audits, we also draw upon the standards and practices of other disciplines.

As part of our regular audit process, we obtained management’s confirmation that the findings in this report are factually based.

Objective

To determine whether Correctional Service Canada (CSC) provides correctional interventions to offenders in a timely manner to assist in their rehabilitation and reintegration into the community.

Scope and approach

We reviewed the Corrections and Conditional Release Act and relevant Commissioner’s Directives, including procedures relating to intake assessment, correctional interventions, and pre-release decision making. We also reviewed staff training for institutional parole officers and managers.

We did not examine the preparation of Aboriginal offenders for release, as they may be referred to correctional programs that have culturally appropriate content and methods to address their risk to reoffend.

We analyzed data extracted from CSC’s Offender Management System (OMS) to identify dates of first release and compared those to dates when offenders were first eligible. Our data included all male, non-Aboriginal offenders first released from custody during the 2009–10 through 2013–14 fiscal years. We assessed the quality of CSC data and found it sufficiently reliable for the purpose of our analysis.

Our work included the review of the OMS database records of 50 male, non-Aboriginal offenders admitted into CSC custody on a new sentence of four years or less during the last four months of 2013. The files were representative of CSC’s five regions and were selected to determine whether CSC was following procedures when completing required intake assessments. We also analyzed the OMS database records of 50 male, non-Aboriginal offenders serving sentences of four years or less released from CSC custody during the last four months of 2013. The files were representative of CSC’s five regions and were selected to identify the correctional interventions delivered to offenders and the timing of their release preparations.

For certain audit tests, results were based on probability sampling. Where probability sampling was used, sample sizes were sufficient to report on the sampled population with a confidence level of 90 percent and a margin of error of +10 percent.

Site visits to selected institutions and structured interviews with CSC institutional and administrative staff, including parole officers and managers, were conducted to confirm the audit findings.

Criteria

To determine whether Correctional Service Canada (CSC) provides correctional interventions to offenders in a timely manner to assist in their rehabilitation and reintegration into the community, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

CSC acquires needed information on offenders to complete intake assessments in a timely manner. |

|

|

CSC has trained and qualified staff to conduct intake assessments. |

|

|

CSC provides required correctional interventions and employment programs to offenders to support their timely reintegration. |

|

|

CSC has trained and qualified staff to provide correctional interventions and employment programs. |

|

|

CSC ensures that complete and timely reports are provided to the Parole Board of Canada at first parole eligibility date and for subsequent reviews. |

|

|

CSC has appropriately trained and qualified staff to prepare release assessments on offenders for the Parole Board of Canada. |

|

Management reviewed and accepted the suitability of the criteria used in the audit.

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period from 1 April 2011 to 31 October 2014. In some cases, analysis has included data from previous years. Audit work for this report was completed on 24 November 2014.

Audit team

Assistant Auditor General: Wendy Loschiuk

Principal: Frank Barrett

Director: Carol McCalla

Donna Ardelean

Daniele Bozzelli

Lori-Lee Flanagan

Stuart Smith

List of Recommendations

The following is a list of recommendations found in this report. The number in front of the recommendation indicates the paragraph where it appears in the report. The numbers in parentheses indicate the paragraphs where the topic is discussed.

Assessing when to recommend offenders for early release

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

6.33 Correctional Service Canada should investigate the reasons for the increases observed in the waivers and postponements of parole hearings, particularly by offenders assessed as low risk. (6.15–6.32) |

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada will undertake a systematic and comprehensive review of the reasons for waivers and postponements of parole hearings, particularly by offenders assessed as low risk—by July 2015. |

|

6.34 Correctional Service Canada should assess the risks associated with offenders being released directly into the community from medium- and maximum-security institutions. (6.15–6.32) |

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada will conduct a study on the risks associated with releasing offenders directly to the community from medium- and maximum-security institutions—by December 2015. |

Delivering correctional programs

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

6.74 Correctional Service Canada should develop guidelines to prioritize the timely delivery of its other correctional interventions, such as employment and education programs, to offenders, and structured tools to assess their impact on an offender’s progress toward safe reintegration into the community. (6.39–6.73) |

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada (CSC) has developed guidelines to prioritize the delivery of correctional interventions, and a structured tool will be available to staff by July 2015. Ongoing use and training on this tool will be completed by April 2016. CSC will implement tools to measure correctional plan performance and accountability by April 2017. |

Determining offender risks upon admission into custody

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

6.87 Correctional Service Canada should clarify which documents are required, at a minimum, for the integrity of its initial assessment of an offender’s security level and the development of an appropriate correctional plan, and work with its partners to obtain these documents in a timely manner. (6.79–6.86) |

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada (CSC) will clarify, in policy, the minimum documentation required for efficient and effective offender assessments—by May 2015. CSC will liaise with other components of the criminal justice system to collect timely and relevant information—by July 2015. |

|

6.88 Correctional Service Canada should strengthen the controls that it has in place to ensure that assessments of an offender’s security level and correctional plan are updated as soon as official documents are obtained for offenders in custody. (6.79–6.86) |

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada will ensure that an offender’s security level and correctional plan updates include all relevant information received after intake assessment—by July 2015. |

|

6.100 Correctional Service Canada should monitor the use of the Custody Rating Scale to ensure that an offender’s security risks are appropriately weighted and officers are properly certified in its use. (6.89–6.99) |

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada (CSC) will create automated information reports to monitor Custody Rating Scale (CRS) usage at the national, regional, and local levels—by July 2015. CSC currently trains staff on the CRS and will strengthen parole officers’ induction training and deliver ongoing training by April 2016. In the interim, the results of monitoring will undergo management reviews at the operational level. |

|

6.101 Correctional Service Canada should develop structured tools to assess both static and dynamic risk factors to prioritize the interventions assigned to offenders that are most likely to bring about positive change and support their timely reintegration. (6.89–6.99) |

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada (CSC) has already initiated work to ensure there is an evidence-based assessment of static and dynamic risk factors for each offender and to determine the types of correctional interventions that address criminal behaviour at the appropriate time in an offender’s sentence. As discussed as part of CSC’s response to the recommendation under paragraph 6.74, a structured tool will be available to staff by July 2015. Ongoing use and training on this tool will be completed by April 2016. |

PDF Versions

To access the Portable Document Format (PDF) version you must have a PDF reader installed. If you do not already have such a reader, there are numerous PDF readers available for free download or for purchase on the Internet: