2015 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada Report 7—Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces

2015 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada Report 7—Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces

Performance audit reports

This report presents the results of a performance audit conducted by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada under the authority of the Auditor General Act.

A performance audit is an independent, objective, and systematic assessment of how well government is managing its activities, responsibilities, and resources. Audit topics are selected based on their significance. While the Office may comment on policy implementation in a performance audit, it does not comment on the merits of a policy.

Performance audits are planned, performed, and reported in accordance with professional auditing standards and Office policies. They are conducted by qualified auditors who

- establish audit objectives and criteria for the assessment of performance;

- gather the evidence necessary to assess performance against the criteria;

- report both positive and negative findings;

- conclude against the established audit objectives; and

- make recommendations for improvement when there are significant differences between criteria and assessed performance.

Performance audits contribute to a public service that is ethical and effective and a government that is accountable to Parliament and Canadians.

Introduction

Background

Governor in Council—The Governor General, acting on the advice of the Privy Council (or Cabinet), as the formal executive body that gives legal effect to those decisions of Cabinet that are to have the force of law.

7.1 The Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces (the Office of the Ombudsman, or the Office) was created in 1998 to promote transparency and fairness in managing the concerns of military personnel, civilian employees of National Defence (the Department), and their family members. The Ombudsman is appointed by the Governor in Council as a special adviser who reports directly to the Minister of National Defence. The Office has 58 civilian employees and a budget of $5.8 million, which is provided from within the Department’s overall budget.

7.2 The Office of the Ombudsman is responsible for investigating complaints about such issues as receipt of benefits, access to medical treatment, and harassment. The Office also publishes periodic reports on its “systemic” investigations, which are carried out on issues that have arisen frequently during individual investigations.

7.3 The position of Ombudsman was created by directives signed by the Minister of National Defence (known as “ministerial directives”). The directives state that the Ombudsman shall be independent of the management and chain of command at National Defence. This independence was intended to allow the Ombudsman to carry out his investigative functions impartially, free from the Department’s influence. For this reason, the Office of the Ombudsman is in a separate building from that of the Department.

7.4 During the period that we audited, there were two successive ombudsmen. The previous Ombudsman served his term from February 2009 to February 2014. The current Ombudsman began his term in April 2014.

7.5 Although the investigations by the Office of the Ombudsman are to be conducted independently of National Defence, the Office’s budget and employees belong to National Defence. As such, the Office’s administrative activities are subject to the same legislation, regulations, and departmental and Treasury Board policies as those of National Defence.

7.6 The Deputy Minister of National Defence has delegated to the Ombudsman responsibility for the Office of the Ombudsman’s financial management, contracting, and human resource management functions. National Defence is therefore responsible for monitoring these functions to ensure that the Office complies with legislation and government policies.

Focus of the audit

7.7 The objectives of the audit were to determine

- whether the Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces (the Office of the Ombudsman, or the Office) established and followed key controls, and systems and practices, related to financial management, contracting, and human resource management in carrying out its mandate, in compliance with government legislation and policies; and

- whether National Defence (the Department) adequately carried out its oversight responsibilities for the Office of the Ombudsman in compliance with government legislation and policies.

7.8 To examine these issues, we focused on the Office of the Ombudsman’s controls for

- governance,

- financial management,

- human resource management, and

- operations.

Internal control—An activity designed to mitigate risks and provide reasonable assurance that an organization’s objectives, including compliance with applicable laws, regulations, and policies, will be achieved.

7.9 This audit is important because the Office of the Ombudsman is an essential recourse mechanism for military personnel and National Defence civilian employees. To carry out its mandate, the Office requires effective internal controls to safeguard public assets and ensure that public funds and resources are used economically and efficiently. Given the fact that the Office is part of National Defence, the Department’s monitoring of the Office is critical in helping to ensure the Office’s accountability in managing financial and human resources.

7.10 The audit covered the period between February 2009 and August 2014. This period included the five-year mandate of the previous Ombudsman, which ended in February 2014, and the transition to the current Ombudsman’s term.

7.11 During the course of our audit, we interviewed the previous Ombudsman to obtain his views, and we provided him with the documentation on which our findings are based. In addition, we provided him with various drafts of the audit report. This report reflects comments and information that we received from him. At the time of publication, the previous Ombudsman did not agree that all the findings of this report were factually based.

7.12 More details about the audit objectives, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Governance

National Defence did not fully define its roles and responsibilities for monitoring the administration of the Office of the Ombudsman

7.13 Overall, we found that National Defence (the Department) did not fully define or document its roles and responsibilities for monitoring the administration of the Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of Defence and the Canadian Forces (the Office of the Ombudsman, or the Office). The Ombudsman was treated the same as other senior departmental managers in some cases, but not others.

7.14 National Defence and the current Ombudsman agreed that the Department should monitor the Ombudsman’s financial and staffing authorities to ensure that they were properly exercised. However, the details of how this should be done and the mechanisms for monitoring other administrative activities were not fully defined or documented.

7.15 This is important because the lack of defined roles and responsibilities resulted in inadequate monitoring of the administrative activities of the Office of the Ombudsman, and in instances of non-compliance with government legislation and policies.

7.16 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

- National Defence’s view of its monitoring roles and responsibilities,

- the previous Ombudsman’s view of monitoring roles and responsibilities, and

- the current Ombudsman’s view of monitoring roles and responsibilities.

7.17 The ministerial directives do not mention the relationship between the Ombudsman and the Deputy Minister. Previous ombudsmen advocated for a legislated mandate that would clearly define the Office as independent from National Defence, both administratively and operationally. The Office’s annual report for the 2012–13 fiscal year indicated that the Office had investigated the possibility of obtaining a new legislated mandate, but had decided not to do so.

7.18 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 7.28.

7.19 What we examined. We examined whether National Defence and the Office of the Ombudsman established clear roles and responsibilities to allow the Department to monitor the Office’s administrative functions. Treasury Board policies state that deputy heads must fulfill oversight responsibility for their departments through a strong system of controls. In our view, the Department was responsible for defining the nature of its relationship with the Office of the Ombudsman so that it could carry out effective monitoring of controls.

7.20 National Defence’s view of its monitoring roles and responsibilities. Although officials at National Defence told us that they saw the Ombudsman as reporting to the Minister for his investigations, they viewed him as a senior Department manager exercising financial and human resource delegations on behalf of the Deputy Minister. To ensure that delegated authorities for financial management and staffing were properly exercised, the Department conducted some monitoring activities, such as financial verifications and staffing reviews of the Office of the Ombudsman. We found this view and these activities to be consistent with Treasury Board policies.

7.21 However, we found that the Department’s treatment of the Ombudsman, and therefore its monitoring of the Office, were inconsistent with its treatment of other senior Department managers. For example, the Department had an arrangement for delegating authorities to the Ombudsman that was different from the one used for all other senior Department managers. The previous Ombudsman was also given separate authority to approve his own hospitality spending for a one-year period (discussed further at paragraph 7.39), and to authorize spending on contracting and hospitality at the level of a deputy head. His predecessors had also had these authorities. Furthermore, unlike other services of National Defence, the Office of the Ombudsman was not audited by Chief Review Services.

7.22 In our view, these practices were inconsistent with the Department’s view of the Ombudsman as a senior Department manager and were therefore inconsistent with Treasury Board policies. We found that the Department did not follow through on its responsibility to define its relationship with the Ombudsman.

7.23 The previous Ombudsman’s view of monitoring roles and responsibilities. The previous Ombudsman told us that the Office’s relationship with National Defence was a subject of contention during his term. He indicated in correspondence to the Deputy Minister that any of the Department’s internal management reviews of the Office’s administrative matters undermined the Office’s independence.

7.24 The current Ombudsman’s view of monitoring roles and responsibilities. The current Ombudsman told us that he recognized that the Office of the Ombudsman was within the legislative and policy framework of National Defence and was delegated financial and staffing authorities from the Deputy Minister. However, he emphasized that given the independence of the Office’s investigative duties, he reported to the Minister, not the Deputy Minister. In our opinion, this statement was inconsistent with Treasury Board policies, because the Deputy Minister must ensure that the delegated authorities granted to the Ombudsman are properly carried out.

7.25 Both National Defence and the current Ombudsman told us that they acknowledged the complexity of their organizational relationship. Department officials told us that they agreed that the Ombudsman is independent in his investigative functions and that he does not report to the Deputy Minister. However, both the Department officials and the Ombudsman agreed that the Deputy Minister has ultimate responsibility under legislation to ensure that delegations for financial management and staffing are properly exercised. In our view, if monitoring arrangements for these areas differ from those in place for other senior Department managers, they must be carefully defined and documented to ensure consistency with Treasury Board policies.

7.26 In addition, we found that several aspects of monitoring roles and responsibilities needed to be addressed:

- Although some monitoring arrangements for financial management and staffing were in place, such arrangements were not in place for contracting and other human resource management activities. Internal audit arrangements were also not fully defined.

- The relationships and accountabilities between the Ombudsman and the Minister and Deputy Minister of National Defence needed to be clearly defined and documented. Definition of these relationships is critical because the Ombudsman is not an employee of National Defence, but a Governor in Council appointee.

- Situations of “mutual review” needed to be carefully negotiated. For example, the Ombudsman’s mandate included investigations of civilian areas of National Defence, such as the civilian human resources group. Therefore, if this group carried out a review of the Office, this review could be perceived as a threat to independence. It is important to acknowledge this risk and have a process in place for managing it.

7.27 In our opinion, the administration of the Office could be made more effective and efficient if the mechanisms, roles, and responsibilities for monitoring were outlined in a formal document that was signed by both the Ombudsman and the Deputy Minister.

7.28 Recommendation. The Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces and the Deputy Minister of National Defence should define and document how National Defence will monitor the management of the administrative functions of the Office of the Ombudsman. They should also define and document how the Office will demonstrate that internal controls, including delegated authorities, are operating as intended. Monitoring activities should not impede the operational independence of the Ombudsman.

The Office of the Ombudsman’s response. Agreed. The Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces agrees that audit mechanisms, both internal to the Office of the Ombudsman and department-wide, are critical to demonstrating that the finance and human resource authorities delegated to the Ombudsman are appropriately exercised. The Ombudsman commits to working with the Deputy Minister of National Defence to review existing mechanisms, to conduct a gap analysis, and to address all outstanding issues.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. National Defence (with the Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces) will define and document the processes by which it will monitor the administrative activities of the Office, to ensure that delegated authorities and internal controls are operating as intended. National Defence will ensure that these processes do not impede the operational independence of the Ombudsman.

Financial controls

Inadequate financial controls and the overriding of existing controls by management led to non-compliance with rules

7.29 Overall, we found that an inadequate system of internal financial controls and the overriding of existing controls by management led to non-compliance with rules within the Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces (the Office of the Ombudsman, or the Office). In many cases between 2009 and 2013, the Office did not follow rules related to the approval and disclosure of travel and hospitality expenses, and to the management of contracts.

7.30 National Defence (the Department) communicated the rules that applied to approval of travel and hospitality and carried out some monitoring of the Office’s transactions, but did not monitor whether those who approved travel and hospitality were authorized to do so, whether all hospitality expenses were disclosed, or whether contracts were in compliance with rules. This monitoring is required by the Treasury Board to ensure that rules are being followed. In the transactions we examined, we found no evidence that the previous Ombudsman personally profited from any of these transactions. The previous Ombudsman told us that his priority was always the Office’s constituents.

7.31 This finding is important because compliance with financial rules and monitoring of compliance help to ensure good stewardship of public resources and accountability for money spent.

7.32 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

- approval of hospitality and travel,

- disclosure of hospitality expenses,

- separation of approvals,

- contracting practices,

- system of financial controls, and

- internal audit.

7.33 The Office of the Ombudsman is subject to the financial policies of National Defence, and to the management and control requirements of the Financial Administration Act and Treasury Board policies and directives.

7.34 Treasury Board policies require the Department to actively monitor the use of delegated authorities and to take remedial action when necessary. Such action includes providing financial guidance to the Office of the Ombudsman, and promoting an understanding of the financial rules.

7.35 Our recommendations in these areas of examination appear at paragraphs 7.52 and 7.53.

7.36 What we examined. We examined whether the Office of the Ombudsman had established and followed key controls related to financial and contract management. We also examined whether National Defence adequately carried out its monitoring responsibilities for the Office of the Ombudsman to help ensure its compliance with legislation and government policies.

7.37 In examining the financial controls, we examined whether there were appropriate expenses and approvals, public disclosure of expenses, and management of contracts for the Office of the Ombudsman. We began by looking at the two largest expenditures incurred during our audit period:

- $100,000 spent to host an international conference in 2012, and

- a contract totalling $370,000.

In these two cases, we noted issues related to approval and disclosure of expenses, separation of approvals, and contracting practices, which led us to examine additional transactions.

Hospitality—As defined by the Treasury Board, money authorized for the provision of meals, beverages, or refreshments to non-public servants at events necessary for the effective conduct of government business and for purposes of courtesy, diplomacy, or protocol. In some cases, hospitality may include entertainment, local transportation, facility rental, and associated costs, such as audio/video equipment and technical support. In some circumstances, hospitality can also be provided to employees.

7.38 Approval of hospitality and travel. Appropriate approvals are required to ensure compliance with the provisions of the Financial Administration Act. The Treasury Board’s Directive on Travel, Hospitality, Conference and Event Expenditures prohibits participants who attend hospitality events from approving their own requests to incur expenses and their own claims for payment. The directive states that the approval of a higher authority is required in such cases. The same rule applies to travel. National Defence told the previous Ombudsman that approval was required by the Minister or the Deputy Minister.

7.39 We examined samples of the previous Ombudsman’s hospitality and travel requests and claims, and looked at how the Department monitored them. We found that the previous Ombudsman and his staff did not always respect the rules. We also found that the Department’s monitoring of these expenses was insufficient to ensure that the rules were followed.

-

Hospitality—In 2011, there was a temporary change in the Treasury Board directive, and the previous Ombudsman was allowed to approve his own hospitality spending for a period of one year. After that period ended, he was again required to obtain pre-approval from the Minister or Deputy Minister. However, we found that he continued to approve some of his own hospitality requests or had them approved by his subordinates. We examined 28 hospitality transactions and found six instances in which he approved his own requests and two instances in which his subordinates approved his requests. In addition, five hospitality transactions for the international conference were not approved by a higher authority, as required by the Treasury Board directive.

The previous Ombudsman indicated to National Defence that he thought his finance director should be allowed to approve Ombudsman hospitality requests, because the chief financial officer for the Department was allowed to approve the Deputy Minister’s hospitality. Between 2010 and 2013, officials from the Department’s financial policy group sent three separate communications to the previous Ombudsman, stating that neither a subordinate nor the Ombudsman himself could approve the Ombudsman’s expenditures, but the previous Ombudsman continued to do so. The Deputy Minister also wrote to the previous Ombudsman to tell him specifically that hospitality expenditures for events attended by the Ombudsman required the pre-approval of the Deputy Minister.

When officials from the Department’s financial monitoring group identified one instance in which the previous Ombudsman had approved his own hospitality claim, they accepted approval by the Ombudsman’s finance director, which was not appropriate. This showed a disconnect between the Department’s financial policy and the actions of its financial monitoring group.

-

Travel—We examined 30 travel expenses incurred by the previous Ombudsman from 2009 to 2013 and found that his subordinates authorized his travel requests in 28 of these cases. National Defence had told the previous Ombudsman in 2010 that travel required pre-authorization by a higher authority, but the finance director continued approving the Ombudsman’s travel. As part of its regular monitoring, the Department reviewed 15 of these travel expenses, but it accepted inappropriate approvals from the Ombudsman’s staff.

7.40 Disclosure of hospitality expenses. According to the Department’s Financial Administration Manual on the Management of Travel and Hospitality Expenditures, senior managers must report on the Department’s website all hospitality expenditures charged to their budget, regardless of whether they attended the events. In 17 of the 35 cases we examined, including 4 cases for the international conference, we found that the Office did not publicly disclose expenses for hospitality events that the previous Ombudsman hosted or attended. The total of these undisclosed expenses exceeded $12,000. The previous Ombudsman told us that because he considered the expenses in 9 of the cases as essential to the Office’s operations, and not as hospitality expenses, he did not realize that they needed to be disclosed. Department officials told us that they did not review disclosures and that each senior Department manager was accountable for accurate disclosure.

7.41 We found no evidence that the previous Ombudsman personally profited from any of the transactions we examined. He told us that his priority was always the Office’s constituents.

7.42 Separation of approvals. The Treasury Board Directive on Delegation of Financial Authorities for Disbursements states that to avoid errors and fraud, separate individuals must approve the initial granting of a contract, the receipt of goods or services, and the authorization of spending. We found nine contracts related to the international conference in which the previous Ombudsman signed all three types of approvals, for goods and services valued at nearly $27,500. The previous Ombudsman told us that there were not enough managers with financial delegation of authority to allow for separation of approvals. The directive states that if circumstances do not allow such a separation of duties, alternate control measures should be implemented and documented. However, we found no documented alternate control for the Office of the Ombudsman.

7.43 Contracting practices. The Office of the Ombudsman used a temporary help services contract to hire a consultant for a large-scale investigation. We found that the Office then extended this contract, and increased the value from $89,000 to $370,000, to hire the same consultant for a new investigation that began when the first one ended. This meant that the Office used the contract for purposes other than those described in the original statement of work, which is prohibited under the Treasury Board Contracting Policy.

7.44 We also found a lack of separation of approvals in this case: The previous Ombudsman approved the initial contract and amendments, timesheets, and invoices in 19 cases, which totalled $182,000. The previous Ombudsman told us that he had not realized that the contract had been extended—rather, he had assumed that there were two separate contracts. When the contract ended, the consultant was hired as a casual employee for eight weeks and was paid $14,000. In our view, not only were contracting rules disregarded, the subsequent hiring of the individual as a casual employee was also inappropriate.

7.45 System of financial controls. The Financial Administration Act, together with policies and directives of the Treasury Board and National Defence, sets out requirements for financial controls.

7.46 As evidenced by findings cited previously in this report, we found that the Office of the Ombudsman had a weak system of financial controls, which enabled the previous Ombudsman to proceed inappropriately, without a full understanding of the rules, or to override the rules.

7.47 Although the Office tracked expenditures against its budget and verified the accuracy of claims before they were approved, the Office’s finance director did not provide a sufficient challenge function to question financial decisions. According to the Treasury Board Policy on Financial Management Governance, this challenge function is required to ensure affordability of spending, completeness and accuracy of financial information, assessment of risks, and compliance with rules.

7.48 Officials at the Office of the Ombudsman told us that they relied on National Defence for the financial monitoring that the Office itself did not carry out. According to departmental directives, the Office should have its own internal monitoring processes. The Office received less monitoring than did other parts of National Defence. Department officials told us that it viewed the Office as a low financial risk, given the size of its budget (less than $6 million), compared with the size of the overall National Defence budget (almost $20 billion). Departmental monitoring included some reviews of expenses for the Office of the Ombudsman, but did not cover all years or all areas. Thus, controls were lacking both within the Office and in the Department’s monitoring of the Office.

7.49 At the end of our audit period, the current Ombudsman advised us that the Office had begun to develop its own system of internal financial controls, including internal post payment verification. He had also requested that National Defence conduct quarterly financial reviews of the Office.

7.50 Internal audit. We found that the Office of the Ombudsman had no internal audit function during the period covered by our audit. According to the Financial Administration Act, the deputy head of a department is responsible for ensuring that an internal audit capacity appropriate to the needs of the department is in place. We found that the Office had not been included in the Department’s internal audit function and did not have its own internal audit capacity, nor had it contracted for this function. The departmental groups involved in financial oversight assumed that Chief Review Services was conducting audits of controls within the Office, which was not the case. Chief Review Services indicated that it did not have the jurisdiction to conduct audits of controls or evaluations of the Office, given the Ombudsman’s independence specified in the ministerial directives.

7.51 We found that the lack of internal audit meant that neither the Department nor the Office of the Ombudsman could be assured that controls were working as intended.

7.52 Recommendation. The Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces should identify risks and gaps in its financial management processes, such as issues related to approvals, disclosure of expenses, and contracting practices, and take corrective action to address these in its system of financial controls.

The Office of the Ombudsman’s response. Agreed. The Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces agrees that the Office’s system of internal controls was insufficient, and since taking office, the Ombudsman has completed a full gap and risk assessment. The Office is in the process of formalizing its internal controls, including drafting methodology for quarterly file reviews, creating checklists for Responsibility Centre managers, reporting into the proactive disclosure system of National Defence (the Department), and refining existing controls. After the audit period, the Ombudsman invited the Department’s Expenditure Management Review team to review its financial systems. The Department’s review was positive and found no irregularities related to the financial management of the Office of the Ombudsman.

7.53 Recommendation. National Defence should provide regular financial monitoring to ensure that controls are in place at the Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces, such as checking that approvers have the right authorization and following up on instances of non-compliance.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. National Defence agrees that regular financial monitoring will be provided to the Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces to ensure that controls are in place and operating effectively.

Human resource management controls

The previous Ombudsman and senior managers did not respect the Values and Ethics Code, and National Defence took insufficient action to address complaints

7.54 Overall, we found that the previous Ombudsman for the Department of Defence and the Canadian Forces and some senior managers did not respect the Values and Ethics Code, which resulted in grievances, complaints, and high levels of sick leave and turnover. National Defence (the Department) received two separate disclosures of values and ethics violations at the Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces (the Office of the Ombudsman, or the Office) and, in our opinion, failed to fully investigate either one or take adequate action to address the issues raised. After 2012, the situation improved, with some changes put in place under the previous Ombudsman and additional changes made under the current Ombudsman.

7.55 This finding is important because the Values and Ethics Code is in place to ensure fairness and respect in the workplace. A lack of respect for values and ethics can lead to a deterioration in the work environment. To maintain trust and uphold the integrity of the disclosure process, it is also important for the Department to take action when staff members come forward with serious complaints.

7.56 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

7.57 The Office of the Ombudsman is subject to human resource legislation and government policies for staffing, pay, labour relations, and values and ethics. The Public Service Employment Act outlines the government’s commitment to fair and transparent employment practices in the public service.

7.58 The Values and Ethics Code for the Public Sector was established in April 2012 by the Treasury Board to fulfill the requirement of the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act. This legislation was created to establish a procedure for the disclosure of wrongdoing in the public sector, including the protection of those who disclose the wrongdoing. The Values and Ethics Code for the Public Sector states that “treating all people with respect, dignity and fairness is fundamental to our relationship with the Canadian public and contributes to a safe and healthy work environment.” The code that was in place before April 2012 set out similar principles. The Terms and Conditions of Employment for Full-Time Governor in Council Appointees also states that leaders must maintain the public’s trust and confidence in government by upholding “the highest ethical standards” and must respect the principles of any code of conduct applicable to their organizations.

7.59 As previously noted, employees at the Office of the Ombudsman are employees of the Department. The Deputy Minister of National Defence is responsible for promoting responsibility and accountability for good human resource management in the Department. The Deputy Minister delegated authority for staffing the Office, except for executive positions, to the Ombudsman. According to the delegation instrument, the Ombudsman is supported in staffing responsibilities by the Department’s civilian human resources staff.

7.60 Our recommendations in these areas of examination appear at paragraphs 7.64 and 7.78.

7.61 What we examined. We examined whether the Office of the Ombudsman established and followed key controls, and systems and practices, related to human resource management, in compliance with government legislation and policies—specifically, the Public Service Employment Act and the Values and Ethics Code. We looked at labour relations files from 2009 to 2013. We also examined whether National Defence adequately carried out its monitoring responsibilities for the Office of the Ombudsman in this area, as required by the staffing delegation instrument. These requirements and activities are intended to achieve a workforce of engaged employees and a high level of performance.

7.62 Staffing. The staffing delegation instrument states that the Ombudsman must do the following:

- undertake appropriate training,

- avail himself on a regular basis of the advice and guidance of a human resources officer, and

- comply with the principles of the Public Service Employment Act and the Public Service Commission Appointment Policy, including the values of fairness and access.

We found that the previous Ombudsman received training on staffing and that he generally took the advice of his human resources director.

7.63 The Public Service Commission Appointment Delegation and Accountability Instrument requires deputy heads to actively monitor staffing through file reviews, internal audits, or other control mechanisms to ensure that the exercise of delegated authorities complies with legislation. We found that the Department conducted a staffing review of the Office of the Ombudsman in 2010, which found no major instances of non-compliance. This review examined staffing activities prior to the audit period. The Department decided not to carry out a follow-up review that was scheduled for the following year, because of the low number of staffing actions resulting from a departmental staffing freeze. At the end of our audit period, no other staffing review had been conducted. It is our view that staffing reviews should be conducted more frequently.

7.64 Recommendation. National Defence should conduct periodic reviews of staffing to ensure that the human resource authorities delegated to the Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces are being exercised in compliance with legislation and departmental policy. Where discrepancies are found, National Defence should discuss and jointly resolve the matter with the Ombudsman.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. National Defence is implementing a service level agreement between the Ombudsman and the Assistant Deputy Minister (Human Resources–Civilian) to provide integrated human resources planning, programs, and operational human resource services to the managers and employees of the Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces, which includes monitoring of sub-delegated human resource authorities.

Within the Assistant Deputy Minister (Human Resources–Civilian) internal monitoring cycle of departmental staffing sub-delegation activities, a review of staffing activities of the Office of the Ombudsman is part of the 2015–16 Staffing Monitoring Plan.

These initiatives will provide additional mechanisms to monitor and ensure compliance with legislation, central agency policies, and sub-delegated authorities for staffing.

7.65 Respect in the workplace. The Office of the Ombudsman has 58 employees. We found that between 2009 and 2012, there were many instances of senior management behaviour that contravened the “respect for people” element of the Values and Ethics Code. Of the 30 current or former employees we interviewed, 17 told us of situations in which they or others had been bullied or belittled, or had been the target of inappropriate jokes, between 2009 and 2012. All 17 employees mentioned that the previous Ombudsman engaged in this behaviour, and 6 of these employees also spoke about other senior managers whose behaviour they perceived as bullying. In some cases, these situations were documented by employees and managers at the time they occurred. During the same period of 2009 to 2012, 12 individuals submitted a total of 17 grievances and numerous complaints through other avenues of recourse. The Office experienced significant turnover during these years, which included the departures of five senior managers and 13 out of an average of 22 investigators. The amount of sick leave was also significant: Many employees, including 13 out of an average of 22 investigators, took long-term sick leave of more than one month between 2009 and 2012.

7.66 The previous Ombudsman told us that the grievances and complaints came from a small number of disgruntled employees, and that departing staff were just using up their remaining sick leave. He told us that turnover was the result of difficult decisions and actions he took between 2009 and 2011 to “improve the organizational culture and rid the Office of the complacency and sense of entitlement that was profoundly affecting performance.” In our opinion, his behaviours and approach to implementing organizational changes did not respect the Values and Ethics Code and had a negative impact on the Office.

7.67 Employee recourse. For other employees of National Defence, the Director General Workplace Management, who is experienced in dealing with grievances, acts as the final departmental level of the grievance process. Although the staff members of the Office of the Ombudsman are employees of the Department, the Ombudsman has the delegated authority to make final decisions on grievances. This authority includes making decisions on grievances in which he is named or involved.

7.68 During our audit period, 17 grievances were filed in the Office of the Ombudsman, 6 of which were directly related to the previous Ombudsman’s actions or decisions. We found that the previous Ombudsman did not recuse himself from deciding on these 6 grievances. Five of these grievances, filed by five separate employees, were related to a decision made by the previous Ombudsman. The previous Ombudsman upheld his original decision, leading many in the Office to perceive that the employees had not been treated fairly. They eventually took their case to the Federal Court, but an out-of-court settlement was reached prior to a hearing.

7.69 We found that there is nothing in the legislative framework that prohibits the delegation of final grievance authority to the Ombudsman. In our view, however, there is potential for a perceived conflict of interest in situations where the Ombudsman is implicated in the grievance. These situations are, in our opinion, more appropriately handled by the Department or a third party.

7.70 National Defence has acknowledged that given the size of the Office of the Ombudsman, the delegation of authority for grievances needs to be reviewed, and the Department is working on a solution.

7.71 Investigation of complaints. In 2011, an employee of the Office of the Ombudsman sent a complaint regarding the previous Ombudsman to National Defence. The complaint alleged that

- the Office had a toxic work environment;

- many employees and managers felt harassed, abused, and bullied; and

- the Office’s mandate was not being carried out effectively.

7.72 National Defence assessed the allegations according to the definition of “wrongdoing” in the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act and determined that the nature of the allegations was such that, if founded, they would constitute wrongdoing under the Act. The Department did a preliminary assessment and concluded that some of the allegations were indeed founded. In our opinion, at this point, the Department should have conducted a full investigation. Instead, a report based on the preliminary assessment concluded that there was no wrongdoing as defined under the Act. The investigators told us that there was no cause to conduct a subsequent investigation, as they did not believe that additional relevant information would have been discovered. They stated that suitable action would be taken to address the issues raised in the preliminary assessment. The report noted that the allegations were serious and recommended a “comprehensive workplace assessment.”

7.73 In our view, National Defence did not follow Treasury Board guidelines in the handling of this complaint because the conclusion of “no wrongdoing” was reached without a full investigation. Department officials told us that because the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act was relatively new, they were still developing their disclosure procedures. In 2012, National Defence received an additional complaint about the Office of the Ombudsman that was also treated as subject to the Act. In our opinion, the Department did not fully investigate this complaint, either.

7.74 The Department responded to the first complaint by conducting a workplace assessment, with the stated objective to “find ways to work together effectively in the future.” In our opinion, the objective of the workplace assessment was not adequate to address the issues as set out in the first complaint and as reported on the basis of the preliminary assessment.

7.75 The workplace assessment was completed in 2012. It made several recommendations to improve the workplace environment. The Deputy Minister asked for an action plan to address all recommendations and for regular updates on actions taken, and he urged the previous Ombudsman to seek external assistance in implementing them. The previous Ombudsman implemented a working group and employees held discussion groups. Despite the fact that not all recommendations were addressed, staff told us that the workplace environment improved. We noted that some of the recommendations that were not implemented applied to the previous Ombudsman himself, such as executive coaching. In our view, follow-up may have been made more difficult because the previous Ombudsman did not see himself as accountable to the Deputy Minister.

7.76 Many Department officials told us that they thought that the Privy Council Office would take action in this situation, given that the Ombudsman was a Governor in Council appointee, and the Privy Council Office was responsible for administering the Governor in Council appointment process. However, there is no policy or other requirement for the Privy Council Office to take action in such a case. Officials at the Privy Council Office told us that it was the Minister’s responsibility to decide on any action with respect to the previous Ombudsman.

7.77 After 2012, during the latter part of the previous Ombudsman’s term, the Office of the Ombudsman held wellness clinics, and employees had conflict management and harassment prevention training. We noted reductions in the levels of turnover, sick leave, and grievances. At the end of the audit period, we found that the current Ombudsman had made additional efforts to foster a respectful workplace, including implementing values and ethics training and establishing a new union–management consultation committee. Staff members were also given access to a harassment advisor and five trained workplace relations advisors.

7.78 Recommendation. The Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces, together with National Defence, should identify potential risks in staffing and workplace relations at the Office of the Ombudsman and address them in the Office’s internal human resource management controls.

The Office of the Ombudsman’s response. Agreed. Where risks to the workplace or staffing have been identified, the Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces will work with the experts at National Defence to promptly address and resolve the issues raised.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The implementation of the service level agreement between National Defence (Assistant Deputy Minister [Human Resources–Civilian]) and the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces means that managers will have access to comprehensive specialist advice and guidance on workplace relations, staffing, change management, and Human Resources planning—at both the operational and corporate levels.

These and other ongoing initiatives will ensure that serious workplace concerns or recruitment and retention issues are monitored and appropriately addressed, while establishing a mechanism for identifying potential future risks.

Operations

Workplace issues and the lack of standard procedures contributed to delays in processing files

7.79 Overall, we found that the combination of a lack of standard procedures for conducting investigations and workplace issues such as turnover and sick leave at the Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces (the Office of the Ombudsman, or the Office) contributed to delays in processing investigations from 2009 to 2012. After 2012, the workplace environment stabilized, and efforts to close long-standing files were successful. Procedures for investigations were being developed but were still not incorporated into training for investigators.

7.80 This finding is important because the timely completion of files is necessary to carry out the Office’s mandate and to provide closure for complainants. Standard procedures are central to carrying out investigations in a timely manner.

7.81 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

7.82 According to its annual report, the Office of the Ombudsman received approximately 1,500 complaints in the 2012–13 fiscal year. Of these, 80 percent were either referred to other mechanisms, such as the Canadian Forces Grievance System, or resolved without the need for an investigation. All cases come through the Office’s intake function, which refers the complainant to other mechanisms, resolves them within a short period, or routes them to the Office’s investigators.

7.83 For recurring complaints on a single issue, a systemic investigation is sometimes conducted. Systemic investigations typically require 4 to 12 months to complete, and the results are publicly reported.

7.84 Recent systemic investigations addressed issues such as the well-being of military families, the quality of life and cost of living at a base located near the oil fields, delays in the processing of adjudications and grievances, the treatment of reservists, and the delivery of care for post-traumatic stress disorder and other operational stress injuries.

7.85 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 7.96.

7.86 What we examined. We examined whether the Office of the Ombudsman established systems and practices to ensure that investigations were carried out in a consistent and timely manner. We did not audit the process for files that were resolved without proceeding to an investigation.

7.87 Time to complete investigations. The ministerial directives state that “the Office shall attempt to complete an investigation within 60 business days of its commencement.” It was not clear to us how this time period was determined or whether it was realistic, given that complex investigations require time for triage of cases, internal approvals, responses from the Department, and in some cases, full implementation of recommendations or resolution of the issue.

7.88 The Office of the Ombudsman considered files that were open for more than one year as “backlogged.” We examined 20 of 122 investigation files that had been open for more than two years between 2009 and 2013. We found that 5 of these files had been transferred between investigators multiple times or sat for long periods while the investigators were reassigned to systemic investigations. We noted five files that had been assigned to investigators who were not available to carry out the work because they had moved to other assignments or were on personal leave. In one case, a file had been open for seven years and had been transferred four times to different investigators.

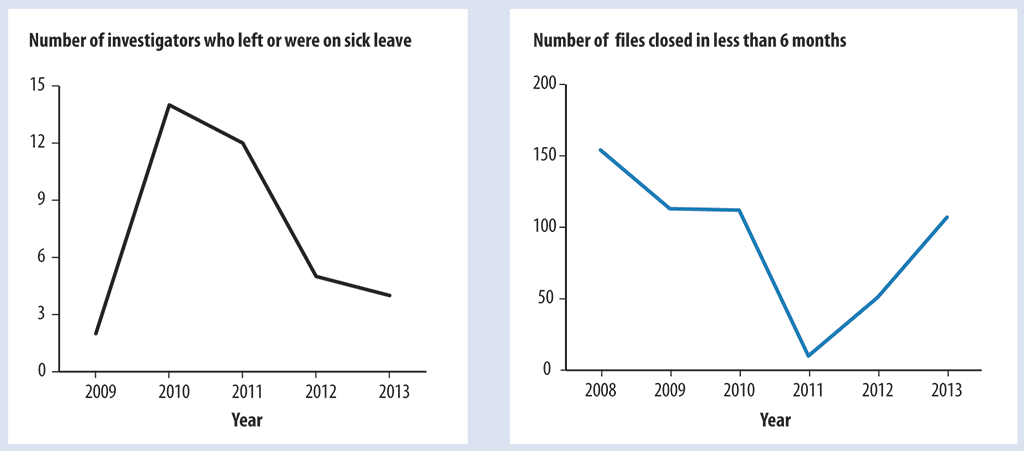

7.89 We were told that backlogs dated back to well before the previous Ombudsman’s term. When the previous Ombudsman became aware of the number of long-standing files, he made an effort to close them by dedicating a small group of investigators to the task, at the same time increasing the effort given to quality review. We found, however, that because of the limited experience of the new managers hired to replace those who had left, and the time required by the additional level of review, it became difficult to close files in a timely manner (Exhibit 7.1).

Exhibit 7.1—Increased turnover and sick leave resulted in fewer timely closures of investigation files

Sources: Information obtained from the Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces, and from National Defence

7.90 We found that files were closed in less than six months for only 6 percent of investigations in 2011, and for only 25 percent of investigations in 2012, compared with 79 percent in 2010. Although some delays were due to issues outside the control of the Office of the Ombudsman, we found that 9 of the 20 files we examined were delayed in whole or in part because of internal inefficiencies.

7.91 In 2011 and 2012, the Office of the Ombudsman implemented a new tracking system that allowed managers to check on the status of a file. This was the first time since the creation of the Office that such information had become available. This tracking system would become vital to efforts to meet service standards. By late 2012, staff turnover started to decline, and a major effort was made to close long-standing files. Staff told us that the backlog was eliminated by fall 2012, compared with the backlog of 200 files that existed in 2010. The Office also started to produce more systemic reports after 2012. In August 2014, when the current Ombudsman had been in the position for five months, there were only 9 files that had been open for more than one year.

7.92 Procedures for investigations. Although the Office of the Ombudsman has existed since 1998, we found that there were no formal procedures for conducting investigations. Documented procedures are important for training new investigators and for ensuring that all steps for an investigation are addressed.

7.93 A project was started in 2009 to document procedures for investigations, but it was not completed. In the absence of documented procedures, there was considerable reliance on the experience of managers and investigators. Staff told us that because of the high turnover of managers and senior investigators, corporate “memory” was lost. The process for undertaking investigations was left to the judgment of the individual investigator, which created a risk that similar files would receive different treatment.

7.94 During the previous Ombudsman’s term, the Office restarted the project to develop standard operating procedures for investigations. It also created a group of subject matter experts who would review all files related to their area of expertise. The intent was to ensure consistency between files and provide a backup person in some cases to allow for knowledge transfer.

7.95 Standard training for investigators was also lacking until a new learning program was developed in 2014, during the current Ombudsman’s term, with modules on communication, interpretation of legislation, planning and organizing, and knowledge of National Defence programs. However, the training did not include investigation procedures. In our view, training for investigators should focus on the new procedures, because these are central to carrying out investigations.

7.96 Recommendation. The Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces should finalize its formal investigation procedures and put in place training based on these procedures.

The Office of the Ombudsman’s response. Agreed. Standard operating procedures for the Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of Defence and the Canadian Forces have been drafted and are being finalized, among which are formal procedures for Ombudsman investigations. A request for proposal has been developed for a service provider to deliver the Ombudsman’s learning and development plan, including training with respect to investigations and the specific procedures developed for the Office of the Ombudsman.

Conclusion

7.97 We concluded that the Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces (the Office of the Ombudsman, or the Office) had inadequate controls for financial management, contracting, and human resource management in carrying out its mandate in compliance with government legislation and policies. In many cases, the Office did not comply with rules or codes of conduct.

7.98 We saw evidence of some improved controls at the end of the term of the previous Ombudsman that continued under the current Ombudsman. There were efforts to identify and address gaps in financial management and to put in place an agreement whereby the Office would use the civilian human resources group of National Defence (the Department) for human resource services.

7.99 We also concluded that although National Defence carried out some of its responsibilities for monitoring the Office of the Ombudsman, these activities were not sufficient to be in compliance with government legislation and policies. The Department did not fully define the roles and responsibilities for carrying out this oversight and did not carry out sufficient monitoring in key areas where we found non-compliance. The Department also did not fully address employee complaints about workplace issues related to values and ethics.

About the Audit

The Office of the Auditor General’s responsibility was to conduct an independent examination of the Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs.

All of the audit work in this report was conducted in accordance with the standards for assurance engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance. While the Office of the Auditor General adopts these standards as the minimum requirement for our audits, we also draw upon the standards and practices of other disciplines.

As part of our regular audit process, we obtained management’s confirmation that the findings in this report are factually based. As noted above, at the time of publication, the previous Ombudsman did not agree that all the findings in this report are factually based.

Objectives

The audit objectives were to determine

- whether the Office of the Ombudsman established and followed key controls, and systems and practices, related to financial management, contracting, and human resource management in carrying out its mandate, in compliance with government legislation and policies; and

- whether National Defence adequately carried out its oversight responsibilities for the Office of the Ombudsman in compliance with government legislation and policies.

Scope and approach

The audit examined selected key “hard” and “soft” controls within the Office of the Ombudsman. Hard controls include compliance with Treasury Board policies and legislation; soft controls include values and ethics. In addition, we looked at the role of National Defence in providing external oversight.

We conducted more than 80 interviews with current and former officials of the Office of the Ombudsman, with National Defence, and with the Privy Council Office, and we reviewed, at the Office of the Ombudsman and at National Defence, more than 700 documents related to Ombudsman activities.

For financial controls, we began by looking at the two largest expenditures at the Office of the Ombudsman during our audit period: a $100,000 international conference in 2012, and a contract totalling $370,000. We noted issues related to the approval and disclosure of expenses, the separation of approvals, and the contracting practices in these two cases, which led us to examine additional transactions. We selected for review additional travel and hospitality transactions for senior management, and also reviewed transactions examined by the groups at National Defence who monitor activities at the Office of the Ombudsman.

The audit did not examine the following:

- executive-level (EX) staffing,

- the effectiveness of operations, or

- the Governor in Council appointment process.

Criteria

To determine whether the Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces established and followed key controls, systems, and practices related to human resource management, finance, and contracting in carrying out its mandate, in compliance with government legislation and policies, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

The Office of the Ombudsman establishes and follows key controls related to human resource management, finance, and contracting in compliance with authorities. |

|

|

The actions of the Ombudsman and senior officials reflect the highest standards of ethical conduct. |

|

| The Office of the Ombudsman has established a governance structure with clear roles, responsibilities, and accountabilities in order to implement the mandate. |

|

| The Office of the Ombudsman has established systems and practices to ensure that investigations are carried out consistently and in a timely manner. |

|

To determine whether National Defence adequately carried out its oversight responsibilities for the Office of the Ombudsman in compliance with government legislation and policies, we used the following criterion:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

National Defence provides oversight of the Office of the Ombudsman for human resource and financial management, in accordance with the Deputy Minister’s accountability framework. |

|

Management reviewed and accepted the suitability of the criteria used in the audit.

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period between February 2009 and August 2014. Audit work for this report was completed on 20 February 2015.

Audit team

Assistant Auditor General: Jerome Berthelette

Principal: Sharon Clark

Director: Joyce Ku

Kathryn Elliott

Robyn Meikle

List of Recommendations

The following is a list of recommendations found in this report. The number in front of the recommendation indicates the paragraph where it appears in the report. The numbers in parentheses indicate the paragraphs where the topic is discussed.

Governance

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

7.28 The Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces and the Deputy Minister of National Defence should define and document how National Defence will monitor the management of the administrative functions of the Office of the Ombudsman. They should also define and document how the Office will demonstrate that internal controls, including delegated authorities, are operating as intended. Monitoring activities should not impede the operational independence of the Ombudsman. (7.19–7.27) |

The Office of the Ombudsman’s response. Agreed. The Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces agrees that audit mechanisms, both internal to the Office of the Ombudsman and department-wide, are critical to demonstrating that the finance and human resource authorities delegated to the Ombudsman are appropriately exercised. The Ombudsman commits to working with the Deputy Minister of National Defence to review existing mechanisms, to conduct a gap analysis, and to address all outstanding issues. National Defence’s response. Agreed. National Defence (with the Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces) will define and document the processes by which it will monitor the administrative activities of the Office, to ensure that delegated authorities and internal controls are operating as intended. National Defence will ensure that these processes do not impede the operational independence of the Ombudsman. |

Financial controls

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

7.52 The Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces should identify risks and gaps in its financial management processes, such as issues related to approvals, disclosure of expenses, and contracting practices, and take corrective action to address these in its system of financial controls. (7.36–7.51) |

The Office of the Ombudsman’s response. Agreed. The Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces agrees that the Office’s system of internal controls was insufficient, and since taking office, the Ombudsman has completed a full gap and risk assessment. The Office is in the process of formalizing its internal controls, including drafting methodology for quarterly file reviews, creating checklists for Responsibility Centre managers, reporting into the proactive disclosure system of National Defence (the Department), and refining existing controls. After the audit period, the Ombudsman invited the Department’s Expenditure Management Review team to review its financial systems. The Department’s review was positive and found no irregularities related to the financial management of the Office of the Ombudsman. |

|

7.53 National Defence should provide regular financial monitoring to ensure that controls are in place at the Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces, such as checking that approvers have the right authorization and following up on instances of non-compliance. (7.36–7.51) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. National Defence agrees that regular financial monitoring will be provided to the Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces to ensure that controls are in place and operating effectively. |

Human resource management controls

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

7.64 National Defence should conduct periodic reviews of staffing to ensure that the human resource authorities delegated to the Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces are being exercised in compliance with legislation and departmental policy. Where discrepancies are found, National Defence should discuss and jointly resolve the matter with the Ombudsman. (7.61–7.63) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. National Defence is implementing a service level agreement between the Ombudsman and the Assistant Deputy Minister (Human Resources–Civilian) to provide integrated human resources planning, programs, and operational human resource services to the managers and employees of the Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces, which includes monitoring of sub-delegated human resource authorities. Within the Assistant Deputy Minister (Human Resources–Civilian) internal monitoring cycle of departmental staffing sub-delegation activities, a review of staffing activities of the Office of the Ombudsman is part of the 2015–16 Staffing Monitoring Plan. These initiatives will provide additional mechanisms to monitor and ensure compliance with legislation, central agency policies, and sub-delegated authorities for staffing. |

|

7.78 The Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces, together with National Defence, should identify potential risks in staffing and workplace relations at the Office of the Ombudsman and address them in the Office’s internal human resource management controls. (7.65–7.77) |

The Office of the Ombudsman’s response. Agreed. Where risks to the workplace or staffing have been identified, the Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces will work with the experts at National Defence to promptly address and resolve the issues raised. National Defence’s response. Agreed. The implementation of the service level agreement between National Defence (Assistant Deputy Minister [Human Resources–Civilian]) and the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces means that managers will have access to comprehensive specialist advice and guidance on workplace relations, staffing, change management, and Human Resources planning—at both the operational and corporate levels. These and other ongoing initiatives will ensure that serious workplace concerns or recruitment and retention issues are monitored and appropriately addressed, while establishing a mechanism for identifying potential future risks. |

Operations

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

7.96 The Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces should finalize its formal investigation procedures and put in place training based on these procedures. (7.86–7.95) |

The Office of the Ombudsman’s response. Agreed. Standard operating procedures for the Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of Defence and the Canadian Forces have been drafted and are being finalized, among which are formal procedures for Ombudsman investigations. A request for proposal has been developed for a service provider to deliver the Ombudsman’s learning and development plan, including training with respect to investigations and the specific procedures developed for the Office of the Ombudsman. |

PDF Versions

To access the Portable Document Format (PDF) version you must have a PDF reader installed. If you do not already have such a reader, there are numerous PDF readers available for free download or for purchase on the Internet: