2015 Fall Reports of the Auditor General of Canada Report 5—Canadian Armed Forces Housing

2015 Fall Reports of the Auditor General of Canada Report 5—Canadian Armed Forces Housing

Introduction

Background

5.1 Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) members relocate many times during the course of their careers. The Department of National Defence and the CAF (National Defence) support members through programs, such as those that provide relocation benefits and, in some locations, a monthly allowance to compensate for higher costs of living. National Defence also supports members by providing access to military housing.

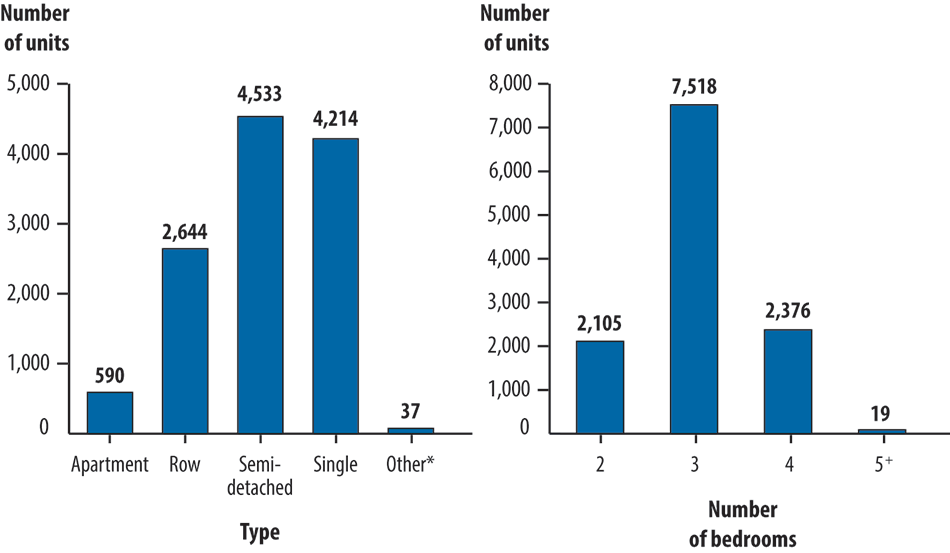

5.2 Military housing is one of several housing options available to CAF members. Most housing units are single or semi-detached homes with three or more bedrooms, because most were built between 1948 and 1960 to accommodate members with families. A smaller number of units are row houses and apartments (Exhibit 5.1).

Exhibit 5.1—Military housing portfolio by type and number of bedrooms

*Other types of units include maisonettes and duplexes.

Source: Adapted from Canadian Forces Housing Agency data, October 2014, which does not include leased housing units. This data should be treated as unaudited.

Exhibit 5.1—text version

The first bar chart shows that there are various types of military housing units. There are 590 apartments, 2,644 row units, 4,533 semi-detached units, and 4,214 single units. Lastly, there are 37 other types of units, which include maisonettes and duplexes.

The second bar chart shows that there are 2,105 military housing units with two bedrooms, 7,518 units with three bedrooms, 2,376 units with four bedrooms, and 19 units with five or more bedrooms.

The data for these charts was adapted from the Canadian Forces Housing Agency data, October 2014, and does not include leased housing units. The data should be treated as unaudited.

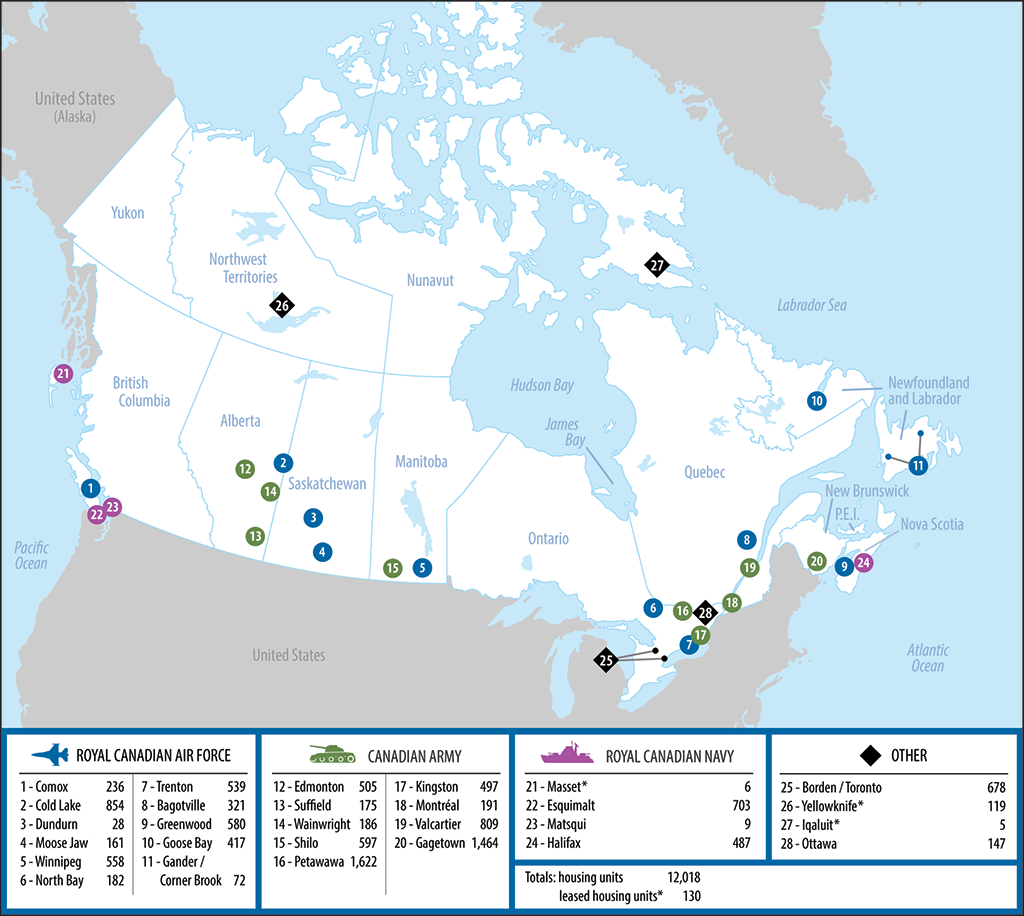

5.3 According to National Defence, about 15 percent of members live in military housing managed by the Canadian Forces Housing Agency (the Agency). About 12,000 housing units are located at 25 sites and about 130 leased housing units are located at 3 sites (Exhibit 5.2).

Exhibit 5.2—The Canadian Forces Housing Agency manages 28 military housing sites across Canada

Source: Adapted from Canadian Forces Housing Agency data, October 2014. This data should be treated as unaudited.

Exhibit 5.2—text version

The map shows the number of military housing units for the Royal Canadian Air Force, for the Canadian Army, for the Royal Canadian Navy, and for other military sites. There are a total of 28 military housing sites: 11 sites for the Royal Canadian Air Force, 9 sites for the Canadian Army, 4 sites for the Royal Canadian Navy, and 4 other military sites. There are a total of 12,018 military housing units, plus 130 leased housing units.

For the Royal Canadian Air Force, the map shows the number of military housing units by location. There are 236 units in Comox, British Columbia; 854 units in Cold Lake, Alberta; 28 units in Dundurn, Saskatchewan; 161 units in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan; 558 units in Winnipeg, Manitoba; 182 units in North Bay, Ontario; 539 units in Trenton, Ontario; 321 units in Bagotville, Quebec; 580 units in Greenwood, Nova Scotia; 417 units in Goose Bay, Newfoundland and Labrador; and 72 units in Gander and Corner Brook, Newfoundland and Labrador.

For the Canadian Army, the map shows the number of military housing units by location. There are 505 units at Edmonton, Alberta; 175 units at Suffield, Alberta; 186 units at Wainwright, Alberta; 597 units at Shilo, Manitoba; 1,622 units at Petawawa, Ontario; 497 units at Kingston, Ontario; 191 units at Montréal, Quebec; 809 units at Valcartier, Quebec; and 1,464 units at Gagetown, New Brunswick.

For the Royal Canadian Navy, the map shows the number of military housing units by location. There are 6 units at Masset, British Columbia, which are leased; 703 units at Esquimalt, British Columbia; 9 units at Matsqui, British Columbia; and 487 units at Halifax, Nova Scotia.

For the other types of sites, the map shows the number of military housing units by location. There are 678 units at Borden and Toronto in Ontario; 119 units at Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, which are leased; 5 units at Iqaluit, Nunavut, which are leased; and 147 units at Ottawa, Ontario.

The data was adapted from the Canadian Forces Housing Agency data, October 2014. The data should be treated as unaudited.

Special operating agency—An agency within a government department that has greater management flexibility in return for certain levels of performance and results.

5.4 Prior to 1995, military housing was managed by individual base (army and navy) and wing (air force) commanders. The housing portfolio was considered dated and in poor condition. In October 1995, the Agency was established as a provisional special operating agency of National Defence. It was allowed to use rental revenues in its management of the housing portfolio, which consisted of about 21,200 units.

5.5 According to the Agency, National Defence invested $400 million in the housing portfolio between 1998 and 2004, for maintenance, disposals, health and safety upgrades, and municipal infrastructure improvements. However, the Agency believed that more work was still needed to bring the portfolio up to contemporary standards.

5.6 In March 2004, the Treasury Board granted the Agency the status of permanent special operating agency. A rationalization framework was also approved to decrease the number of units to 12,500 and to modernize the portfolio. At that time, there were more than 16,000 units.

5.7 The Agency shares military housing responsibilities with the CAF and other parts of National Defence (Exhibit 5.3).

Exhibit 5.3—Many parts of National Defence are responsible for military housing

| Chief of Military Personnel | Develops, approves, implements, and reviews National Defence’s military housing policy and standards. |

| Senior commanders of army, air force, and navy | Define operational requirements and provide advice on military housing needs. |

| Assistant Deputy Minister (Infrastructure and Environment) | Oversees military housing, provides guidance and technical oversight on the management of the housing portfolio, and oversees the Canadian Forces Housing Agency. |

| Canadian Forces Housing Agency | Ensures military housing units are maintained to a suitable standard, and develops and implements plans to meet the future housing needs of the Canadian Armed Forces. |

Focus of the audit

5.8 This audit focused on whether the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces (National Defence) managed military housing in a manner that supported housing requirements, that was consistent with government regulations and policies, and that was cost-effective.

5.9 We examined the policies and practices that National Defence used to support decisions on military housing requirements. We also examined how the Canadian Forces Housing Agency managed military housing.

5.10 This audit is important because, according to National Defence, access by Canadian Armed Forces members to suitable housing contributes to operational effectiveness, the morale of members, and the well-being of members and their families.

5.11 We did not examine other National Defence housing, such as training and transient quarters and leased housing units, or programs that supported the relocation of military personnel.

5.12 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Military housing requirements

National Defence did not clearly define its operational requirements for military housing in a manner consistent with its policy

5.13 Overall, we found that the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces (National Defence) did not comply with key aspects of its military housing policy. We found that National Defence did not clearly define its operational requirements for military housing. We also found that, at some locations, it did not consider how the private housing market could meet the needs of Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) members.

5.14 This is important because clear operational requirements help to define military housing needs, including what style of housing to provide (such as housing size and number of bedrooms), which members to provide the housing to, and where to provide it. In addition, by knowing when the private housing market can meet members’ needs, National Defence can focus its work on locations where military housing is necessary.

5.15 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

- military housing policy,

- operational requirements,

- private housing market, and

- affordability and compensation.

5.16 The Canadian Forces Housing Agency (the Agency) received its status as a permanent special operating agency on the condition that National Defence follow established government policy on Crown-owned housing.

5.17 Government policy requires that Crown-owned housing be provided only when the housing directly supports operational requirements, or when suitable housing is not available in the private housing market. When housing is no longer needed, the surplus should be removed from the portfolio.

5.18 Government policy also requires that occupants of Crown-owned housing be treated equally to those renting similar housing in the private market. This means that Crown-owned housing should be similar in condition, style, and cost, and should not be more affordable.

5.19 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 5.38.

5.20 What we examined. We examined National Defence policy and practices to determine whether they were consistent with applicable regulations and government policy, and used to support decisions on military housing.

5.21 Military housing policy. National Defence last updated its Living Accommodation policy in 2007, though we noted that it has been under review since 2009. This policy states that National Defence can provide military housing only in locations where there is an operational requirement, or where the private housing market cannot meet the needs of CAF members.

5.22 The policy further states that the affordability of housing, when it arises, should be addressed through compensation. Housing should not provide an entitlement or benefit to members, and all members should have equitable access to suitable housing.

5.23 The policy is supplemented by National Defence’s Living Accommodation Instruction. This instruction defines the standards that apply to military housing, notably livable space and number of rooms, as well as the rules that govern how and which members can access and occupy housing.

5.24 Therefore, we found that National Defence’s policy was generally consistent with government policy. However, we also found that National Defence did not comply with the following two key aspects of its own policy.

5.25 Operational requirements. First, we found that National Defence did not clearly define its operational requirements for military housing in order to determine what housing to provide, which members to provide it to, and where to provide it.

5.26 In the past, National Defence allowed members to live in military housing only if they were married or had families, although there were exceptions for single members based on availability. National Defence’s 2007 policy, however, states that all members are eligible to live in military housing and that units are to be allocated on a first-come, first-served basis according to household size.

5.27 In 2010, National Defence engaged an external panel to examine and report on the required number of military housing units. For the purpose of this examination, National Defence endorsed principles that applied to the provision of military housing, some of which were different from those in the 2007 policy. For example, the 2007 policy states that, when allocating military housing, National Defence should not give preference based on rank. But the 2010 principles state that military housing is particularly important for new members with dependents and for members who must move often to meet the CAF’s succession-planning needs. The panel concluded that using these principles would result in a requirement of about 5,800 military housing units in 30 locations nationwide.

5.28 However, senior military officials did not agree with the report’s conclusion. They felt that the proposed number of units was too low and that other factors needed to be considered, such as

- proximity to the site (commuting distance),

- availability of personnel for disaster response,

- volatility of the private housing market,

- members facing difficulties in their personal life (such as divorce, financial problems, and dependents with disabilities), and

- availability of National Defence services on site.

5.29 National Defence then reassessed the required number of military housing units and, in 2012, approved a requirement of 11,858 units at 24 locations. We found that it did not use a specific methodology to determine this number and largely based the number on internal discussions and an estimate developed by the Agency in 2011. The Agency had based its work on the 2007 policy and had concluded that a portfolio of 11,819 units would be required.

5.30 We noted that the Agency arrived at its 2011 estimate by including the number of occupied units and a portion of the number of members waiting for a unit, even though some waiting members already had housing. In addition, the number included a high vacancy rate of 15 percent, consisting of 5 percent for operational flexibility and 10 percent for renovations and maintenance. This estimate thus required that more than 1,500 housing units be vacant at any given time.

5.31 The Agency stated that, when completed, the review of the 2007 policy could significantly affect the required number of units and the way the portfolio is managed. At the end of our audit period, National Defence had not completed the policy review and was still figuring out which members should get housing, which bases and wings needed housing, and whether housing was needed in urban markets. In other words, National Defence had not clearly defined the operational requirements that would help determine the number of military housing units.

5.32 Private housing market. Second, we found that, when National Defence approved the military housing requirement of 11,858 units, it had not considered how the private housing market could have met the needs of CAF members.

5.33 For example, market analyses performed for the Agency showed that the private housing market could have generally met members’ needs in urban locations such as Halifax and Valcartier. By not considering the private housing market, the Agency was therefore not acting in a manner consistent with National Defence and government policies.

5.34 Affordability and compensation. We also found that National Defence is constrained in the application of its policy regarding the affordability of housing. National Defence’s policy states that when it provides military housing it must be allocated on a first-come, first-served basis and that affordability of housing should be ensured through compensation. This is consistent with government policy. However, when National Defence offers housing, it must also comply with the Charges for Family Housing Regulations (Appendix 4.1 of Queen’s Regulations and Orders Volume IV), which define how it must calculate rental charges.

5.35 These Regulations were issued in 2001 under the authority of the National Defence Act and take precedence over the government and National Defence policies. They include a potential limit on the amount of rent charged (as a percentage of a family’s gross annual income) and contain provisions intended to make military housing more affordable to junior ranks.

5.36 The Regulations also state that the monthly rental rate of military housing must be based on annual appraisals prepared by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC). However, the CMHC stopped doing these appraisals in April 2013. Since then, the Agency has calculated the annual rental increase on existing units based on previous annual increases and the Consumer Price Index. At the end of our audit period, there still was no formal process to update appraisal values.

5.37 The Agency also had market analyses indicating that rental rates were below those of the private housing market in locations such as Bagotville, Edmonton, and Winnipeg. In our opinion, when rental rates are below private market rates, it is likely that military housing provides occupants with financial benefits. Such benefits could thus create inequities between military housing and private housing occupants.

5.38 Recommendation. National Defence should complete the review of its military housing policy and clearly define its operational requirements for military housing.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. In September 2015, at a pre-meeting of National Defence’s Accommodation Board, the advisory body of the military housing policy, the departmental stakeholders were directed to complete the review of the operational requirement for military housing. The review, to be completed by the fall of 2016, will draw from the findings of previously published reports to recommend changes and revisions to the existing policy. National Defence will produce a revised accommodation policy by the fall of 2017.

Military housing management

5.39 Overall, we found that the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces (National Defence) did not have adequate plans that defined the work, time, and resources needed to modernize the military housing portfolio and meet the current and future needs of Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) members. We also found that the Canadian Forces Housing Agency (the Agency) was working under constraints that limited its ability to spend its funds effectively on military housing.

5.40 This is important because adequate plans could help the Agency better meet the current and future needs of members. However, constraints can prevent National Defence from completing the high-priority work that could help it achieve its goal of modernizing the portfolio.

5.41 In 2002, National Defence outlined its vision for providing housing to CAF members in Accommodation in Support of the Canadian Forces: A Vision for 2020, which includes the goal of bringing the military housing portfolio up to contemporary standards. At the time, most housing units had been built between 1948 and 1960, and had three or more bedrooms to meet the needs of members with families. However, demographics had changed since then: there were more members who were single and without dependents. Military housing was also expected to be of a quality comparable to housing in the private market, but the portfolio had not been updated in many years.

5.42 A condition of the Agency’s status as a permanent special operating agency was to develop and implement a management framework for the portfolio that would help National Defence meet the housing needs of its members. This framework was to address the portfolio’s condition and National Defence’s military housing requirements. In 2006, the Agency completed a review of the existing portfolio. The review assessed the condition of the housing units, their suitability against contemporary standards, and the adequacy of the portfolio to meet members’ needs and National Defence’s requirements. The Agency proposed to undertake work estimated at $1.95 billion over 25 years to modernize the portfolio. However, Agency officials told us that National Defence did not support this large investment because of competing priorities and, therefore, funding and the proposed plan were not approved.

National Defence did not have adequate plans for military housing

5.43 We found that although National Defence had a goal of modernizing the military housing portfolio, it did not have an adequate and approved long-term plan that determined the work, time, and resources needed to achieve this goal. We also found that the Agency had developed planning documents for each base and wing, but that these documents also did not define the work, time, and resources needed. Finally, we found that the Agency did not have updated information about the condition of housing units to inform its decisions.

5.44 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

5.45 This finding matters because without an adequate plan to modernize the portfolio, the Agency cannot ensure that its work on existing and new housing units will meet the current and future needs of CAF members. Furthermore, National Defence cannot assess whether it has made progress in transforming the portfolio or whether it has effectively used resources dedicated to housing.

5.46 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 5.53 and 5.54.

5.47 What we examined. We examined whether the Agency had developed adequate plans that defined the work, time, and resources needed to meet National Defence’s military housing requirements.

5.48 Long-term plan. National Defence stated that its goal is to have a contemporary housing portfolio. However, it did not have an adequate and approved long-term plan to improve the condition of the portfolio, bring it up to contemporary standards, and help it better meet CAF members’ needs.

5.49 Site planning documents. The Agency had developed site planning documents for each base and wing. These documents estimated the number of housing units needed, and included some analysis of the required size and style of units to meet the needs of members. In several locations, the Agency documented a gap between the housing needs of members caused by changes in household sizes and types, and the military housing units available to meet those needs. For example, the Agency identified that some members in Borden, Edmonton, Shilo, and Valcartier needed smaller and higher-density units, such as apartments or row units. The site planning documents did not identify when these units would be built or what resources would be needed, and no actions were taken to meet these needs.

5.50 Most of these site planning documents outlined options and scenarios to address increased, reduced, or unchanged housing needs of members at the site. However, they did not clearly identify the work, time, and resources needed to implement these options and scenarios. The Agency stated that it used these planning documents, despite their limitations, as one of the tools to set priorities at the site level and guide the selection of housing units to be worked on.

5.51 Condition assessment of housing units. The Agency also used condition assessment information from a national database to set priorities for its annual spending plan on housing units. However, the information was not always reliable. Agency officials told us that the information was not regularly updated as required. We also noted that the information had not been updated since October 2014, because of software problems. Consequently, the Agency did not have up-to-date information on the condition of the housing units to guide spending priorities.

5.52 According to the Agency, since 2004, it has reduced the overall number of housing units from about 16,000 to about 12,000, which is consistent with the goal of reducing and modernizing the portfolio. In addition, the Agency has fully renovated 842 of these units and built 149 new units. However, without an adequate and approved long-term plan, the Agency cannot ensure that the funds spent on housing units were used effectively to better meet current and future housing needs.

5.53 Recommendation. Once National Defence has completed its policy review and clearly defined its operational requirements for military housing, it should develop adequate plans that identify the work, time, and resources needed to meet these requirements.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. National Defence will have a long-term accommodation plan in place within a year after

- the accommodation policy review is complete, and

- operational requirements for military housing are clearly defined and have received departmental approval.

This long-term plan will respond to National Defence’s revised accommodation policy and the defined operational requirements. The plan will be multifaceted and will offer a range of options to meet the newly defined requirements, which could include updating National Defence’s existing portfolio plans as well as innovative approaches to deliver its housing program. The plan will be fully costed and funded based on projected revenues and departmental appropriations.

5.54 Recommendation. The Canadian Forces Housing Agency should regularly capture and update its condition assessment information to ensure it is accurate and available to inform decisions.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Canadian Forces Housing Agency has configured the condition assessment functionality within its recently upgraded Housing Agency Management Information System and has transferred the housing asset condition data from the old system. The transfer of the housing condition data collected since October 2014 will be completed by the end of November 2015. The Agency will complete system training and system rollout to regional offices by 31 March 2016. The Agency will

- strengthen its management oversight of the condition assessment business processes,

- monitor the quality and timely entry of data through ongoing system reports, and

- conduct a full review of the housing condition assessment data annually prior to the end of the fiscal year to allow for sound decision making.

National Defence could not spend funds on military housing effectively

5.55 We found that the Agency could not effectively spend its two primary sources of funding: rental revenues from occupants and capital funds from National Defence. We found that the Agency’s use of rental revenues was constrained. We also found that National Defence did not commit stable capital funds to the Agency, often providing a significant amount late in the fiscal year. National Defence acknowledged these problems and was considering alternative options.

5.56 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

5.57 This finding matters because between the 2012–13 and 2014–15 fiscal years, about $270 million in rental revenues and about $110 million in capital funding were spent on the military housing portfolio. Given the constraints, the Agency cannot ensure that it is using resources effectively on priority work—work that could help the Agency achieve its goal of modernizing the portfolio.

5.58 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 5.69.

5.59 What we examined. We examined documents and other information on funding and financial planning from the Agency and National Defence.

5.60 Rental revenues. From the 2012–13 to 2014–15 fiscal years, the Agency collected approximately $90 million annually in rent. The Agency had to spend these rental revenues in the fiscal year in which it collected them. Under the Financial Administration Act, the Agency cannot carry over rental revenues to future fiscal years. Therefore, if funds are not spent at the end of a fiscal year, they are not available to the Agency in future years.

5.61 The Agency was also constrained in its use of rental revenues within the year. Under the Financial Administration Act and annual appropriation acts, National Defence has parliamentary authority to spend its rental revenues only on operating costs, such as maintenance and repair on existing housing units. In other words, these funds could for example be used to replace windows and doors, but not to fully renovate units or to build new units. Larger renovations and new constructions—major work that could help National Defence achieve its goal to modernize the portfolio—required capital funding.

5.62 Capital funding. National Defence receives capital funding through parliamentary appropriation. We found that it did not commit a stable annual amount of capital funding to the Agency, but provided funding throughout the year.

5.63 From the 2012–13 to 2014–15 fiscal years, National Defence provided about $37 million per year in capital funding. However, the Agency did not receive the full amount at the beginning of each year. In the 2014–15 fiscal year, for example, the Agency received $43 million in four instalments, including the largest instalment of almost $19 million in July, and the last instalment of $6 million in January, only two months before year end. According to the Agency, this timing did not match the construction cycles. Although the Agency had already identified work that could be completed during the year, it did not have enough time to allocate funds to highest-priority work so that it could be carried out by the end of the fiscal year.

5.64 We found that receiving funds late in the fiscal year reduced the Agency’s ability to use them effectively. For example, planning to do significant work on units often means ensuring that units be vacant. When units could not be kept vacant, work was limited to unit components or other lower-priority property improvements, such as building fences or installing sheds. This work was relatively easy to implement, but may not have had the largest impact on improving housing conditions. According to the Agency, when it did not know the amount of funding in advance, it could not plan renovation work on an entire housing unit in a way that took advantage of the economies of scale.

5.65 To alleviate the constraints associated with the amount and timing of capital funding, the Agency provided a portion of its rental revenues to National Defence in exchange for an equivalent amount of capital funding. According to the Agency, this allowed it to better plan work, because the amount and timing of the funding were known before the beginning of the fiscal year.

5.66 Between the 2012–13 and 2014–15 fiscal years, $22.5 million of rental revenues were provided to National Defence. According to National Defence, these revenues were used to cover operating costs of military housing, such as payments in lieu of taxes. However, we noted that National Defence did not clearly define what its military housing costs were and which of these costs were to be covered by rental revenues. Since an expected benefit of creating the Agency was to make the operating costs of military housing more transparent, it is important for the Agency and National Defence to document and track what the operating costs are and which of these costs are to be covered by rental revenues.

5.67 Alternative options. National Defence acknowledged the constraints on the management of military housing. In 2012, it hired a consulting firm to examine how the portfolio was managed and whether there were alternative delivery options for housing. The firm made recommendations related to the costs of current operations and alternative delivery models. At the end of our audit period, the Agency was implementing some of the firm’s recommendations, such as developing ways to lower the cost of minor repairs. National Defence was also discussing options for other delivery models.

5.68 Meanwhile, the Agency will continue to spend rental revenues and capital funding, including an additional $102 million as part of the 2015 Federal Infrastructure Program, to be spent on projects at 10 housing sites in the 2015–16 and 2016–17 fiscal years.

5.69 Recommendation. National Defence should ensure that it uses resources dedicated to military housing effectively. In particular, it should

- clarify operating costs and track the costs it expects to be covered by rental revenues, and

- allocate capital funds in a timely manner so that it can plan their use adequately.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. National Defence will compile a reconciliation at the end of every fiscal year that will report housing rental revenues received and expenditures incurred within National Defence related to and in support of military housing operations. This will be an ongoing requirement, with the reconciliation to be produced by the Assistant Deputy Minister (Infrastructure and Environment) no later than 30 days after the end of the previous fiscal year.

Furthermore, National Defence will approve capital funding to the Canadian Forces Housing Agency through resource allocation decisions made as a result of the departmental three-year integrated business planning cycle. Consequently, funding to the Agency will be allocated over a three-year planning period through the initial allocation letter signed by the Deputy Minister at the beginning of every year.

Conclusion

5.70 We concluded that National Defence’s policy on military housing was consistent with government policy, but that National Defence did not comply with key aspects of its own policy. Most notably, it did not clearly define its operational requirements or consider how the private housing market could meet the needs of Canadian Armed Forces members.

5.71 We also concluded that National Defence did not have adequate and approved plans to support the current and future needs of military housing and, because of constraints, could not spend its funds effectively to modernize the portfolio.

About the Audit

The Office of the Auditor General’s responsibility was to conduct an independent examination of military housing to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs.

All of the audit work in this report was conducted in accordance with the standards for assurance engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance. While the Office adopts these standards as the minimum requirement for our audits, we also draw upon the standards and practices of other disciplines.

As part of our regular audit process, we obtained management’s confirmation that the findings in this report are factually based.

Objective

The audit objective was to determine whether the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces (National Defence) managed military housing in a manner that supported housing requirements, that was consistent with government regulations and policies, and that was cost-effective.

Scope and approach

The audit examined how the Canadian Forces Housing Agency (the Agency) managed military housing. This included how National Defence determined housing requirements (present and future numbers, location, suitability) and how the Agency managed the housing portfolio to meet these requirements.

The audit did not examine other National Defence housing, such as training and transient quarters and leased housing units, or programs that supported the relocation of military personnel.

We examined National Defence policies and practices as well as other relevant planning documents used to support decisions on military housing requirements. We also examined documents and information on strategic and financial planning at the Agency, including the process for setting rental rates and for approving renovations and construction. We conducted interviews with entity officials responsible for determining operational requirements and housing policies, and for planning and managing the military housing portfolio. We selected five bases and wings to examine in more detail and undertook site visits. These sites were selected to provide a mix of army, navy, and air force requirements in different areas of the country (rural, semi-urban, and urban).

Quantitative information in this report is based on data provided by National Defence.

Criteria

To determine whether the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces (National Defence) managed military housing in a manner that supported housing requirements, that was consistent with government regulations and policies, and that was cost-effective, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

National Defence has clearly defined present and future military housing requirements consistent with government policies. |

|

|

The Canadian Forces Housing Agency has adequate plans to meet military housing requirements. |

|

|

The Canadian Forces Housing Agency obtains sufficient resources to meet military housing requirements in a timely manner. |

|

|

The Canadian Forces Housing Agency implements plans and projects cost-effectively. |

|

Management reviewed and accepted the suitability of the criteria used in the audit.

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period between 1 April 2010 and 31 March 2015. Audit work for this report was completed on 28 September 2015.

Audit team

Assistant Auditor General: Jerome Berthelette

Principal: Gordon Stock

Directors: Liliane Cotnoir and André Côté

Lisa Harris

Robyn Meikle

Jeff Stephenson

Stephanie Taylor

List of Recommendations

The following is a list of recommendations found in this report. The number in front of the recommendation indicates the paragraph where it appears in the report. The numbers in parentheses indicate the paragraphs where the topic is discussed.

Military housing requirements

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

5.38 National Defence should complete the review of its military housing policy and clearly define its operational requirements for military housing. (5.20–5.37) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. In September 2015, at a pre-meeting of National Defence’s Accommodation Board, the advisory body of the military housing policy, the departmental stakeholders were directed to complete the review of the operational requirement for military housing. The review, to be completed by the fall of 2016, will draw from the findings of previously published reports to recommend changes and revisions to the existing policy. National Defence will produce a revised accommodation policy by the fall of 2017. |

Military housing management

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

5.53 Once National Defence has completed its policy review and clearly defined its operational requirements for military housing, it should develop adequate plans that identify the work, time, and resources needed to meet these requirements. (5.43–5.52) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. National Defence will have a long-term accommodation plan in place within a year after

This long-term plan will respond to National Defence’s revised accommodation policy and the defined operational requirements. The plan will be multifaceted and will offer a range of options to meet the newly defined requirements, which could include updating National Defence’s existing portfolio plans as well as innovative approaches to deliver its housing program. The plan will be fully costed and funded based on projected revenues and departmental appropriations. |

|

5.54 The Canadian Forces Housing Agency should regularly capture and update its condition assessment information to ensure it is accurate and available to inform decisions. (5.43–5.52) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Canadian Forces Housing Agency has configured the condition assessment functionality within its recently upgraded Housing Agency Management Information System and has transferred the housing asset condition data from the old system. The transfer of the housing condition data collected since October 2014 will be completed by the end of November 2015. The Agency will complete system training and system rollout to regional offices by 31 March 2016. The Agency will

|

|

5.69 National Defence should ensure that it uses resources dedicated to military housing effectively. In particular, it should

|

National Defence’s response. Agreed. National Defence will compile a reconciliation at the end of every fiscal year that will report housing rental revenues received and expenditures incurred within National Defence related to and in support of military housing operations. This will be an ongoing requirement, with the reconciliation to be produced by the Assistant Deputy Minister (Infrastructure and Environment) no later than 30 days after the end of the previous fiscal year. Furthermore, National Defence will approve capital funding to the Canadian Forces Housing Agency through resource allocation decisions made as a result of the departmental three-year integrated business planning cycle. Consequently, funding to the Agency will be allocated over a three-year planning period through the initial allocation letter signed by the Deputy Minister at the beginning of every year. |

PDF Versions

To access the Portable Document Format (PDF) version you must have a PDF reader installed. If you do not already have such a reader, there are numerous PDF readers available for free download or for purchase on the Internet: