2016 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada Report 5—Canadian Army Reserve—National Defence

2016 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada Report 5—Canadian Army Reserve—National Defence

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- List of Recommendations

- Appendix—Army Reserve unit locations and average strength as a percentage of ideal unit size, 2014–15 fiscal year

- Exhibits:

- 5.1—The Army Reserve is organized into units across the country

- 5.2—The 2008 Canada First Defence Strategy identifies six core missions

- 5.3—The Army Reserve helped prevent flood damage in Alberta

- 5.4—The Army Reserve had about 14,000 active and trained soldiers in the 2014–15 fiscal year

- 5.5—Training should prepare soldiers and units to adapt quickly to various types of non-combat and combat operations

- 5.6—Non-commissioned Army Reserve infantry soldiers receive less initial weapons training than Regular Army infantry soldiers

Introduction

Background

5.1 National Defence is composed of the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces. The Canadian Army, including its Army Reserve, is the component of the Canadian Armed Forces that conducts missions on land. The Army Reserve is fully integrated into the Canadian Army’s chain of command. When Army Reserve members put on their uniforms or volunteer for training or deployment, they are required, like all other members of the Canadian Armed Forces, to carry out their missions without reservation, regardless of personal discomfort, fear, or danger.

Soldiers—All persons who are enrolled in the Canadian Army, including officers and non-commissioned members.

5.2 The Army Reserve is the largest component of Canada’s Primary Reserve Force. As of August 2013, it had provided almost half of the Canadian Army’s 40,143 soldiers. The Army Reserve consists predominantly of part-time professional members of the Canadian Armed Forces who contribute to the defence and security of Canada. These part-time members must balance the demands of their military activities with their civilian lives.

Army Reserve units conduct training to prepare their soldiers for combat and non-combat operations.

Photo: National Defence

5.3 Training and operating the Army Reserve costs about $724 million annually, based on figures from the 2013–14 fiscal year. Army Reserve units train to be ready to support domestic and international missions. In recent years, Army Reserve units and soldiers have contributed to domestic missions involving fighting floods and forest fires. Army Reserve soldiers have also served on international missions, including deployments to Bosnia and Afghanistan. According to the Canadian Armed Forces, Army Reserve soldiers completed 4,642 deployments to Afghanistan. Sixteen of these soldiers died and 75 were wounded in action. In addition, between 2012 and 2015, Army Reserve soldiers were deployed 150 times on 16 other international missions. At the time of our audit, Army Reserve soldiers were deployed to international missions in Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and the Caribbean.

Focus of the audit

5.4 This audit focused on the ability of National Defence to organize, train, and equip its Army Reserve soldiers and units so that they are prepared to deploy as part of an integrated Canadian Army.

5.5 This audit is important because National Defence has determined that the Canadian Army needs the support of the Army Reserve to successfully conduct domestic and international missions.

5.6 We did not examine other components of Canada’s Primary Reserve Force, such as the Navy Reserve, the Air Force Reserve, or the Military Police Reserve.

5.7 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Guidance on preparing for missions

5.8 Overall, we found that Army Reserve units lacked clear guidance on preparing for major international missions. We also found that although the Army Reserve had clear guidance on preparing for domestic missions, formal confirmation that they were prepared was not required. In addition, Army Reserve units and groups lacked access to key equipment on deployments and training exercises.

5.9 This is important because National Defence needs the Canadian Army, including a fully integrated Army Reserve, to organize, train, and equip land forces to meet Canada First Defence Strategy missions.

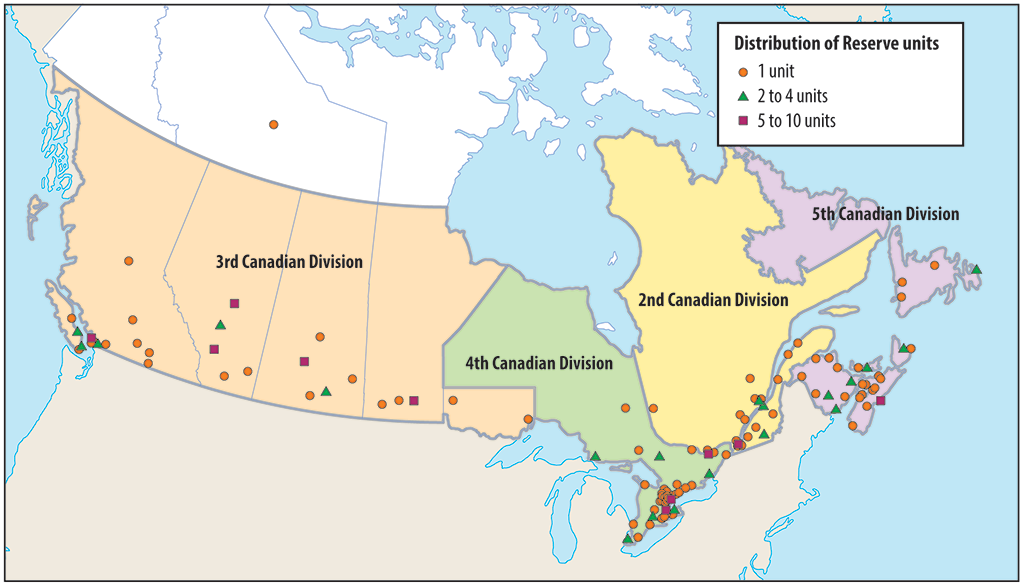

5.10 The Army Reserve is organized into 123 units and 10 brigade headquarters in 117 communities across the country (Exhibit 5.1). The Appendix identifies these units and their local communities. The purpose of these units is to organize, train, and equip their member soldiers to work as cohesive teams so that they are prepared to deploy and accomplish assigned missions.

Exhibit 5.1—The Army Reserve is organized into units across the country

Note: The 1st Canadian Division is not responsible for specific Army Reserve units.

Source: Based on information from National Defence

Exhibit 5.1—text version

This map shows how Army Reserve divisions and units are distributed across Canada.

- The 1st Canadian Division is not responsible for specific Army Reserve units.

- The 2nd Canadian Division operates in Quebec.

- The 3rd Canadian Division operates in British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Northwestern Ontario. One of the units in Alberta supports a team located in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories.

- The 4th Canadian Division operates in Southwestern Ontario, Central Ontario, and Eastern Ontario.

- The 5th Canadian Division operates in Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, and Newfoundland and Labrador.

The map shows where the Army Reserve units are located for each Division. Small shapes represent various numbers of units in the following categories: single units, 2 to 4 units, and 5 to 10 units. The heaviest concentrations of units are found along Canada’s southern border, particularly in southern Ontario. Most Army Reserve units operate in the eastern half of the country.

5.11 The Canadian Armed Forces is expected to conduct domestic and international missions, as identified in the 2008 Canada First Defence Strategy (Exhibit 5.2). The Canadian Army must be prepared to deploy land forces that are capable of both combat and non-combat missions.

Exhibit 5.2—The 2008 Canada First Defence Strategy identifies six core missions

- Conduct daily domestic and continental operations, including in the Arctic.

- Support a major international event in Canada, such as the Olympic Games.

- Respond to a major terrorist attack.

- Support civilian authorities during a crisis in Canada, such as a natural disaster.

- Lead and/or conduct a major international operation for an extended period.

- Deploy forces in response to crises elsewhere in the world for shorter periods.

Source: National Defence

5.12 The Canadian Army has stated that it needs the Army Reserve and the Regular Army to be fully integrated in order to carry out all of these missions, which may occur simultaneously. In 2014, the Commander of the Canadian Army set out what the Canadian Army must do to build an integrated Army Reserve, including the following:

- ensure that the Army Reserve is prepared for domestic and international missions;

- provide Army Reserve soldiers and units with access to the equipment that they need to train themselves;

- recruit and retain Army Reserve soldiers to accomplish Canada First Defence Strategy missions;

- fully fund all activities, including training, that Army Reserve units must undertake;

- optimize individual occupational training for the Army Reserve;

- integrate collective training of Army Reserve soldiers and units into the three-year training cycle of the Regular Army; and

- assess the effectiveness of the Canadian Army’s training system.

Army Reserve units lacked clear guidance on preparing for major international missions

5.13 We found that the Canadian Army had not given Army Reserve units clear guidance as to how they should prepare soldiers and teams to contribute to major international missions. Although the Canadian Army had given Army Reserve units guidance on general training requirements, it had not identified what it expected the units to do to organize and train their soldiers in preparation for international missions.

5.14 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

5.15 This finding matters because Army Reserve soldiers and teams are essential to the Canadian Army’s ability to conduct international missions.

5.16 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 5.22.

5.17 What we examined. We examined Canadian Army planning documents and reports. We also interviewed senior Canadian Army commanders, command teams of Army Reserve units, and Army Reserve soldiers who would be expected to contribute to international missions.

5.18 Guidance for international missions. The Canadian Army expects Army Reserve units to provide up to 20 percent of the soldiers deployed on major (large-scale, extended-period) international missions. This means that after Regular Army soldiers are deployed on the first rotation (planned for up to eight months), Army Reserve units will provide about 1,000 trained soldiers for each subsequent rotation of the mission. These soldiers could be placed in existing Regular Army units or be part of dedicated Army Reserve teams of up to 150 soldiers that will undertake one of the following key tasks:

- Influence Activities,

- Convoy Escort,

- Force Protection, or

- Persistent Surveillance.

5.19 We found that the Canadian Army has directed Army Reserve units to train soldiers to work in teams of 25 to 40 soldiers so these small teams can work together in teams of up to 150 or more soldiers. As a result, more training is required before Army Reserve soldiers and teams can deploy on major international missions. Individual Army Reserve soldiers placed in existing Regular Army units are to be given this additional training when they join these units for their pre-deployment training.

5.20 On major international deployments, the Canadian Army expects that dedicated Army Reserve teams will perform specific key tasks. However, we found that individual Army Reserve units had not been given clear guidance on the training that is required for the key tasks of Convoy Escort, Force Protection, and Persistent Surveillance until a mission has been identified. The Canadian Army plans for Regular Army soldiers to perform these tasks until dedicated Army Reserve teams have been trained for deployment. In our opinion, the absence of guidance for these key tasks is inconsistent with the Canadian Army’s expectation that Army Reserve soldiers will be prepared to provide these tasks as part of dedicated Army Reserve teams during major international missions.

5.21 We found that the Canadian Army did provide clear guidance for one key task: Influence Activities. This task coordinates support between military forces and civilian authorities and shapes the opinions and perceptions of target groups, be they friendly or hostile. The Army Reserve is responsible for training almost all of the soldiers needed for the Canadian Army’s Influence Activities task. At least one Influence Activities team of 52 soldiers is to be prepared to deploy without delay with the Regular Army for Canada First Defence Strategy missions.

5.22 Recommendation. National Defence should provide individual Army Reserve units with clear guidance so that they can prepare their soldiers for key tasks assigned to the Army Reserve for major international missions.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. Providing the necessary training to soldiers before they participate in international deployments is of paramount importance to the Canadian Army. Guidance regarding the required training is provided in the Army’s annual operation plan. Once Reserve participation in a given expeditionary operation is announced, specific direction is given with respect to the training required for individuals and for designated Reserve Teams (to conduct tasks such as Convoy Escort, Force Protection, and Persistent Surveillance). Every Team is “confirmed” through a deliberate process before being given the green light to deploy. The Army will work toward improving its guidance for anticipated key tasks for major international missions.

Army Reserve units and groups were not fully prepared for domestic missions

5.23 We found that the Canadian Army had provided the Army Reserve with clear guidance on preparing for domestic missions. However, we also found that when Army Reserve units and groups deployed on domestic missions, they did not always have access to key equipment. Furthermore, we found that the Canadian Army did not require formal confirmation in writing that Army Reserve brigade groups were prepared to support domestic missions.

5.24 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

- guidance for domestic missions, and

- formal confirmation that Army Reserve groups were prepared to support domestic missions.

5.25 This finding matters because the Canadian Army needs the Army Reserve to be organized, trained, and equipped so that it is prepared to support civilian authorities in their responses to major domestic events and to carry out other domestic missions, including sovereignty exercises in the Arctic.

5.26 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 5.32 and 5.34.

5.27 What we examined. We examined Canadian Army planning documents and reports. We also interviewed senior Canadian Army commanders, command teams of Army Reserve units, and Army Reserve soldiers who would be expected to contribute to domestic missions.

5.28 Guidance for domestic missions. We found that the Canadian Army had given clear guidance to Army Reserve units on preparing for domestic missions, except for equipment needs. This guidance included the number of soldiers required, their organization into teams, their training requirements, and when they needed to be prepared to deploy. For example, each unit is expected to contribute a specific number of trained soldiers to assemble groups of 400 to 600 soldiers within three days of being notified of a domestic mission.

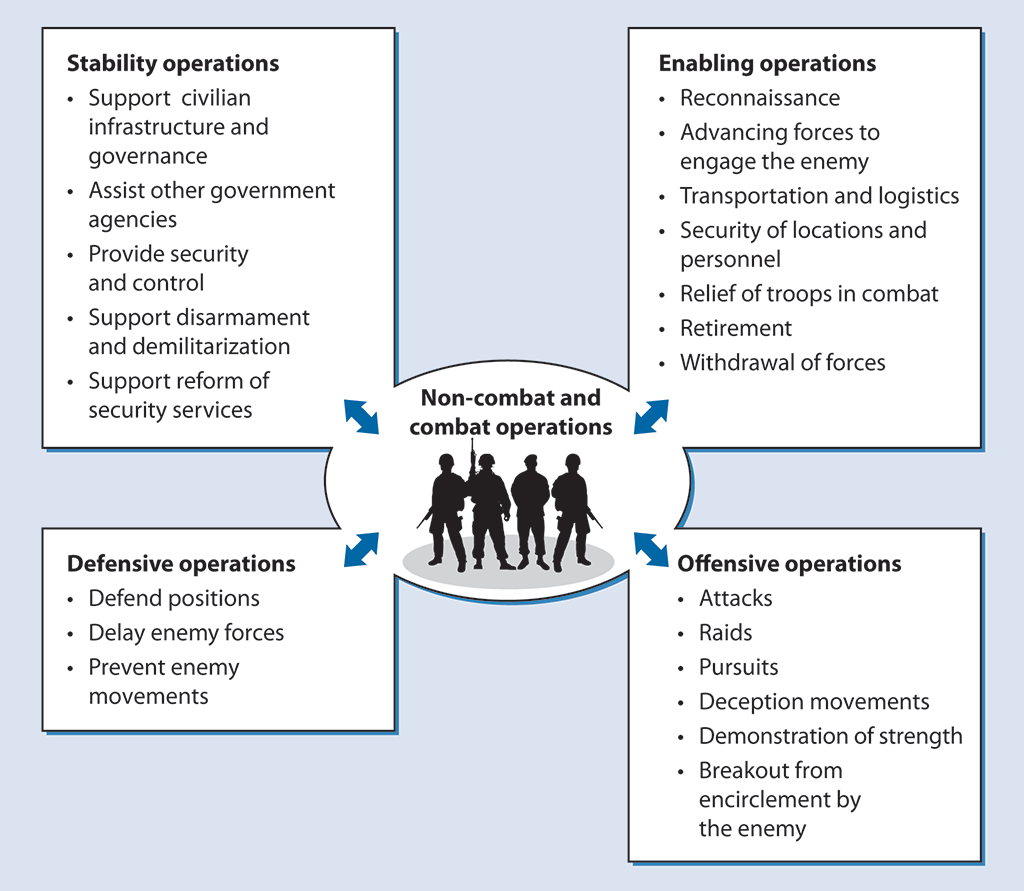

5.29 We found that the Canadian Army has not defined the list of equipment that all Army Reserve units should have for training their soldiers and teams for domestic missions. This means that Army Reserve units may have to rely on other Canadian Armed Forces units to provide this equipment, but we were told that it is often not available. In our opinion, this limited access to equipment impedes the ability of units to train their soldiers and teams.

5.30 We also found that between 2013 and 2015, the Army Reserve contributed to three domestic missions involving fighting floods in Alberta and Manitoba and fighting a forest fire in Saskatchewan (Exhibit 5.3). After each of these missions, the Army Reserve brigade groups and units conducted a lessons-learned exercise to report on the planning and conduct of these missions. When we reviewed these reports, we found many instances of key equipment lacking, such as reconnaissance vehicles, command posts, and communications equipment.

Exhibit 5.3—The Army Reserve helped prevent flood damage in Alberta

During the severe flooding in southern Alberta in 2013, the Canadian Army deployed 2,300 Regular and Reserve soldiers to assist civil authorities. In that deployment, the South Alberta Light Horse regiment, an Army Reserve unit located in Medicine Hat and Edmonton, was called out to prevent damage in the City of Medicine Hat. Working with citizens, soldiers filled and installed more than 17,000 sandbags in a single day to create a berm to stop flood waters. The action was reported to have prevented significant damage to the city’s power and water treatment plants. Soldiers also assisted other emergency responders in pumping out water from the Canmore hospital. Their combined efforts allowed the hospital to establish normal access in two days.

Source: Based on information from National Defence

5.31 In 2013, the Canadian Army directed Army Reserve units to provide about 500 trained soldiers for four specialized Arctic operations groups by 2016. The Canadian Army provided these Army Reserve groups with guidance to train for these operations, including sovereignty exercises. This guidance included a list of equipment necessary for these Arctic operations groups to train and deploy in the Arctic. However, following recent training exercises, these groups reported that they did not always have access to the equipment they needed to be self-sufficient, such as reliable communications and vehicles larger than light snowmobiles.

5.32 Recommendation. The Canadian Army should define and provide access to the equipment that Army Reserve units and groups need to train and deploy for domestic missions.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. A procurement plan is under way to address the shortages within certain fleets. The Canadian Army has defined and provides the equipment required to conduct domestic operations. The majority of this equipment is held either within the unit or with the Canadian Brigade Group. When a specific requirement or gap is identified that is not within the Brigade Group, the Division will reallocate from within its own resources or will request additional items from national stocks.

5.33 Formal confirmation that Army Reserve groups were prepared to support domestic missions. We were told that Army Reserve groups were not required to formally confirm in writing that they were prepared to support domestic missions. We found that some brigade groups did formally confirm that they were prepared to support domestic missions whereas others did not. In our opinion, given the importance and significant cost of large-scale training exercises, the Canadian Army needs to formally confirm in writing that Army Reserve groups are prepared for domestic missions.

5.34 Recommendation. The Canadian Army should require Army Reserve groups to formally confirm that they are prepared to support domestic missions.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Canadian Army will review the process and develop a better-documented confirmation method. The Army conducts training on an annual basis for the 10 Territorial Battalion Groups and the four Arctic Company Response Groups. This training may be verbally confirmed through the chain of command, which is found to be sufficient for training objectives.

Sustainability of Army Reserve units

5.35 Overall, we found that Army Reserve units do not have the number of soldiers they need to train so that soldiers and teams are prepared to deploy when required. The number of Army Reserve soldiers has been steadily declining because the Army Reserve is unable to recruit and retain the soldiers it needs. We found that the Canadian Army does not know if Army Reserve soldiers have the current qualifications they need to deploy for domestic and international missions. Furthermore, we found that the Army Reserve units did not have the funding they needed to fully support all required unit activities.

5.36 This is important because Army Reserve units need enough trained soldiers and adequate funding if they are to organize and train soldiers and teams to be combat-capable and prepared for deployment.

5.37 The National Defence Act established the Reserve Force as “a component of the Canadian Armed Forces … that consists of … members who are enrolled for other than continuing, full-time military service.” This means that most members of the Army Reserve are part-time professional soldiers. Army Reserve soldiers may also voluntarily sign contracts for full-time employment with National Defence. This full-time employment may be for domestic or international deployments or for other positions within National Defence. The only time consent for full-time service is not required is through an order signed by the Governor General acting on the advice of Cabinet.

5.38 Army Reserve units and groups are responsible for training their own soldiers so that they can be deployed as part of an integrated Army on domestic and international missions. To accomplish this, Army Reserve units need a sufficient number of soldiers to participate in unit activities, including training exercises.

Army Reserve units did not have the soldiers they needed

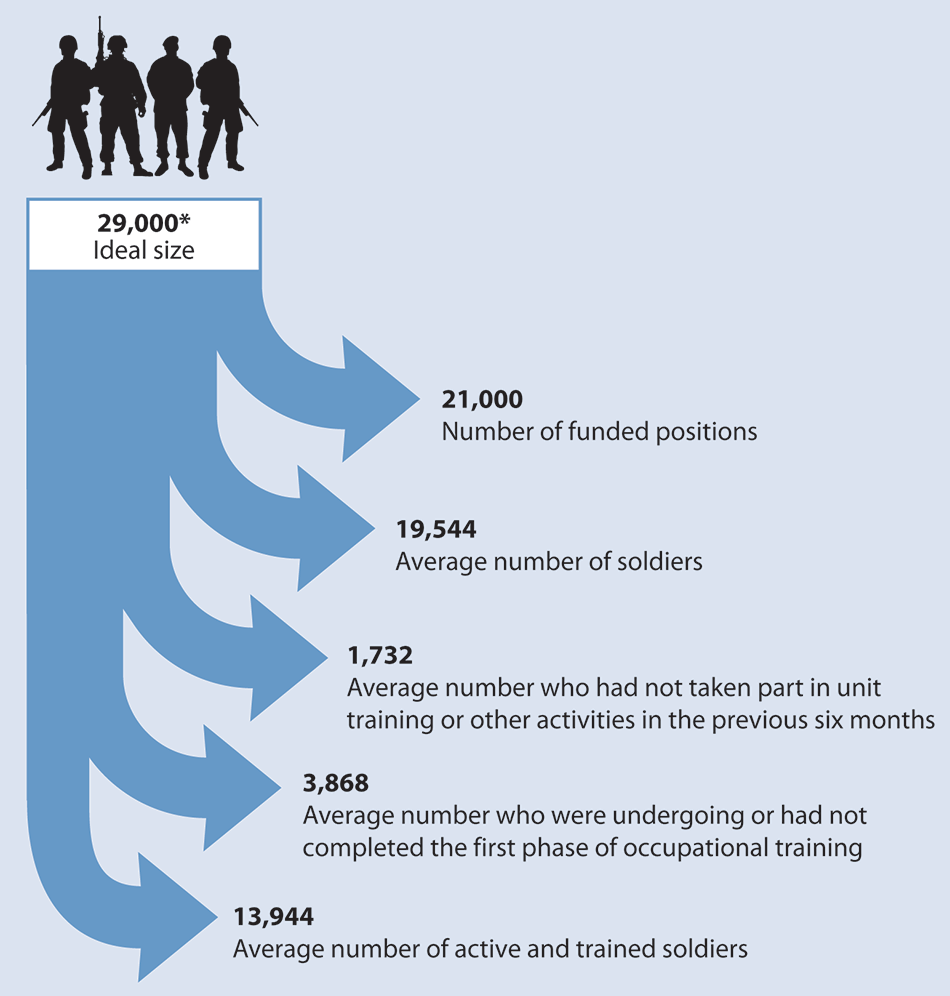

5.39 We found that National Defence has determined that about 29,000 positions in the Army Reserve in the 2014–15 fiscal year would be its ideal size. This number of positions allows the Army Reserve to expand when increases to funding are authorized. During the same period, the Canadian Army provided funding for 21,000 full- and part-time Army Reserve soldiers. However, we found that the average number of trained and attending soldiers in the Army Reserve was 13,944, and that 12 of the 123 Army Reserve units had fewer than half of the soldiers needed for their ideal unit size.

5.40 Between the 2012–13 and 2014–15 fiscal years, the number of Army Reserve soldiers declined by about five percent per year, as a result of several factors. In particular, we found that the National Defence recruiting system was not able to recruit the number of soldiers needed by the Army Reserve, and that Army Reserve units had difficulty retaining their trained soldiers.

5.41 It is critical that the Canadian Army know whether its soldiers are prepared to deploy for domestic and international missions. However, we found that the information system used by the Canadian Army to verify the status of individual soldiers showed that soldiers had low levels of current qualifications.

5.42 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

- size of the Army Reserve,

- number of Army Reserve soldiers,

- terms of service,

- medical care, and

- information about qualifications needed for deployment.

5.43 This finding matters because having the right number of trained Army Reserve soldiers prepared to deploy is critical to the Canadian Army’s ability to perform assigned missions.

5.44 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 5.57, 5.62, 5.65, and 5.70.

5.45 What we examined. We analyzed data from the information systems at National Defence that identified the number and current qualifications for deployment of Army Reserve soldiers. We also reviewed the terms of service and the use of contracts for full-time employment of Army Reserve soldiers. We examined National Defence documents, guidance, and internal analysis. We also interviewed senior departmental and Regular Army officials, and commanders and soldiers of Army Reserve units.

5.46 Size of the Army Reserve. We found that National Defence has determined that about 29,000 positions in the Army Reserve would be its ideal size. This number of positions allows the Army Reserve to expand when increases to funding are authorized. (The Appendix shows the strength of each Army Reserve unit as a percentage of the unit’s ideal size.)

5.47 We also found that for the 2014–15 fiscal year, the Canadian Army had budgeted $334.9 million for about 21,000 Army Reserve soldiers. This means that the Army Reserve was funded for about 72 percent of its ideal size: $202.4 million to cover the pay for 19,471 soldiers on part-time service, $91.3 million for 1,500 full-time soldiers, and $41.2 million for operating and maintenance costs.

5.48 In the 2014–15 fiscal year, the average number of part-time and full-time soldiers in the Army Reserve was 19,544. Of that number, 1,732 had not taken part in unit training or other activities in the previous six months, and 3,868 were undergoing or had not completed the first phase of their occupational training. This means that approximately 70 percent of the soldiers in the Army Reserve, 13,944 on average, were trained and had attended unit activities in the previous six months (Exhibit 5.4).

Exhibit 5.4—The Army Reserve had about 14,000 active and trained soldiers in the 2014–15 fiscal year

* This number of positions allows the Army Reserve to expand when increases in funding are authorized.

Source: Based on information from National Defence for the 2014–15 fiscal year

Exhibit 5.4—text version

This diagram contrasts the ideal size of the Army Reserve with the number of funded positions and average number of active and trained soldiers in the Army Reserve in the 2014–15 fiscal year.

About 29,000 positions make up the ideal size of the Army Reserve. This number allows the Army Reserve to expand when increases in funding are authorized.

In the 2014–15 fiscal year, there were 21,000 funded positions and an average of 19,544 soldiers.

Of these 19,544 soldiers,

- an average of 1,732 had not taken part in unit training or other activities in the previous six months,

- an average of 3,868 were undergoing or had not completed the first phase of occupational training.

Therefore, there was an average of 13,944 soldiers who were active and trained.

5.49 All Army Reserve units are responsible for training their soldiers and sustaining their day-to-day operations, such as managing human and financial resources and maintaining their equipment. We found that 58 of the 123 Army Reserve units were at less than 70 percent of their ideal unit size. Of these, 12 Army Reserve units were at less than 50 percent of their ideal unit size. In our opinion, when units get this small they are not able to train effectively because they lack the qualified instructors, leaders, or soldiers they need to train in teams of 25 to 40 soldiers. The Canadian Army recognizes that smaller units are limited in what they can do and therefore groups them with other units to complete their training to work in teams.

5.50 Number of Army Reserve soldiers. We found that between the 2012–13 and 2014–15 fiscal years, the number of Army Reserve soldiers had been declining at a rate of about five percent, or about 1,000 soldiers per year.

5.51 We found that the National Defence recruiting system did not recruit the number of soldiers needed by the Army Reserve and that Army Reserve units had difficulty retaining their soldiers. National Defence officials stated that the current Reserve recruiting system does not work—it is too slow and does not recruit the number of Army Reserve soldiers it needs, given the present rate of attrition.

5.52 Each year, National Defence sets recruitment targets for all components of the Canadian Armed Forces. We found that in the 2014–15 fiscal year, the recruiting system’s objective was to deliver 2,200 recruits to the Army Reserve—far fewer than the 3,000 recruits needed. National Defence has recognized that it needs to reform the recruiting system.

5.53 We found that National Defence has not developed a retention strategy for the Army Reserve. For example, in order to train their soldiers, units must retain a sufficient number of qualified instructors, such as master corporals or sergeants. We found that units have had difficulty keeping the qualified instructors they need. For example, from 2012 to 2015, the number of master corporals in the Army Reserve declined from 1,971 to 1,770, and the number of sergeants declined from 1,645 to 1,593.

5.54 We also found that during the 2012–13 to 2014–15 fiscal years, almost half of the 7,200 soldiers who left the Army Reserve did so before they had completed their first level of occupational training. This represents a lost investment in recruitment and training.

5.55 The Canadian Army knows it needs to take steps to improve retention in the Army Reserve. The Canadian Army has recognized that providing challenging, exciting training will help improve retention. Furthermore, the Canadian Army does not facilitate the transfer of Regular Army soldiers to the Army Reserve. Doing so would enable the Canadian Army to retain valuable skills within the Army Reserve acquired by Regular Army soldiers.

5.56 In late 2015, National Defence set a goal to increase the Army Reserve by 950 soldiers (five percent) by 2019. In our opinion, this goal will be difficult to achieve given the present rate of attrition.

5.57 Recommendation. National Defence should design and implement a retention strategy for the Army Reserve.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. Retention enables Canadian Armed Forces’ operational and institutional excellence. National Defence will develop and implement a Canadian Armed Forces retention strategy that will ensure retaining our members in uniform is a fundamental aspect of how we manage our people, and is given equal, if not greater, prominence in our attraction and recruiting efforts. Our approach going forward will be comprehensive and incorporate the Regular and Reserve Force, creating greater mobility between these components and accounting for the range of requirements inherent in each. While consideration will be given to transactional requirements in the areas of compensation and benefits, National Defence will develop effective measures including, but not limited to, career management, family support, mental health and wellness support, and diversity requirements.

The Canadian Army is developing a retention strategy for the Army Reserve, and is in the process of updating the strategy based on Chief Military Personnel initiatives.

5.58 Terms of service. Part-time Army Reserve soldiers serve and train on a voluntary basis. Therefore, it is not possible for unit commanders to know if all their soldiers will take part in scheduled activities, including training. For example, in 2015, when Army Reserve units met for their annual large-scale collective training events across Canada, only 3,593 soldiers (26 percent of trained and attending soldiers) attended these exercises.

5.59 Army Reserve soldiers (and any other Reservists) may accept contracts for full-time service with their units, with Army headquarters, or elsewhere in National Defence. These contracts are for periods of 180 days to three years, and can be renewed for much longer periods. While Army Reserve soldiers working under such contracts for up to three years could be regarded as not employed on a continuing full-time basis, in our view, Army Reserve soldiers engaged on such contracts for more than three years are employed on a continuing full-time basis. This is inconsistent with the National Defence Act, which states that Primary Reserve members are enrolled for other than continuing full-time military service when not on active service undertaking emergency duties for the defence of Canada or deployed on international missions. National Defence has, in effect, created a class of soldiers that does not exist in the Act. Furthermore, these soldiers receive 85 percent of the salary and lesser benefits than Regular Army soldiers would receive for the same work.

5.60 We found that in the 2014–15 fiscal year, as many as 1,704 Army Reserve soldiers were on full-time contracts beyond 180 days with the Canadian Army. This means that the Canadian Army spent about 27 percent of its overall Army Reserve pay and operating expenses on these full-time contracts, leaving less available for other Army Reserve activities.

5.61 In 2011, a National Defence report on the employment of full-time Reserve soldiers noted the need to determine the legal and policy basis for these full-time contracts. The report recommended that a full regulatory review of Reserve full-time employment be completed immediately. At the time of our audit, National Defence had not concluded this review.

5.62 Recommendation. National Defence should review the terms of service of Army Reserve soldiers, and the contracts of full-time Army Reserve soldiers, to ensure that it is in compliance with the National Defence Act.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Canadian Armed Forces will review the framework for the Reserve Force terms of service and the administration of Reserve Force service to ensure it complies with the National Defence Act and the regulations enacted under it.

5.63 Medical care. National Defence policy requires Canadian Armed Forces personnel to report any injury, disease, illness, or exposure to toxic material, whether it is service-related or not. We found that over the 2012–13 to 2014–15 fiscal years, Army Reserve soldiers filed about 3,250 reports. We used representative sampling to examine 846 of these reports and found that 35 percent of incidents happened during individual or collective training and 37 percent occurred during physical fitness activities.

5.64 A 2008 report by the Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces found that there was significant confusion throughout the Canadian Armed Forces about medical care entitlements for Reservists serving in Canada. We found that access to medical care for Reservists was still not clear. For example, Army Reserve soldiers do not receive regular medical assessments as Regular Army soldiers do. Also, if Army Reserve soldiers injure themselves during physical fitness training to meet Canadian Armed Forces fitness requirements, Canadian Armed Forces’ medical services do not always provide for care unless that training was formally pre-approved by their commanding officer.

5.65 Recommendation. National Defence should review its policies and clarify Army Reserve soldiers’ access to medical services.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Canadian Forces Health Services Group Headquarters is actively advancing a number of initiatives to review and support policies for medical assessments that contribute to Primary Reserve soldiers’ overall readiness for training and deployment, and that clarify access to medical services, including

- issuing a communiqué to establish the priority for Reservists to receive medical assessments from Headquarters (released October 2015);

- updating the Queen’s Regulations and Orders, Chapter 34, Section 2 (Medical Care of Officers and Non-commissioned Members), currently with the National Defence Regulations Section for amendment drafting, with estimated anticipated approval six months after Section work is complete. In 2009, Health Services Group Headquarters published interim guidance on entitlement to health care for Reserve Force personnel. This was also communicated to members in correspondence dated 2011 from the Vice Chief of the Defence Staff, along with an accompanying guide. Annual reminders are issued to health care providers with regard to entitlement rules;

- assessing courses of action proposed in the joint Canadian Forces Ombudsman/Health Services Group study, “The Feasibility of Providing Periodic Health Assessments to All Primary Reservists” (June 2015) and other potential tools to determine medical fitness and conduct periodic health assessments, through a Reserve Medical Readiness Working Group. It is anticipated that alternatives will be developed by August 2016 and implemented in the fall of 2016.

5.66 Information about qualifications needed for deployment. It is critical that the Canadian Army has information on personnel and training deficiencies that would constrain its ability to be prepared to deploy for domestic and international missions. National Defence maintains a Personnel Readiness Verification system that records soldiers’ current qualifications that are required for deployment.

5.67 We examined reports from the Personnel Readiness Verification system of the qualifications required for Canadian Army soldiers before being deployed. These reports listed the following levels of qualification in place in December 2015 for Army Reserve soldiers:

- defence against nuclear, biological, and chemical threats (5 percent up to date);

- handling of personal weapon (7 percent up to date);

- first aid training (19 percent up to date);

- physical fitness (55 percent up to date); and

- medical requirements (65 percent up to date).

We found that the system does not capture civilian qualifications such as language and cultural skills, which Army Reserve soldiers could bring to the Canadian Army when they are deployed.

5.68 However, senior Canadian Army officials told us that the information recorded by the Personnel Readiness Verification system was not up to date and produced information that could not be relied upon. They also told us that Army Reserve units were not updating this system because the units had a heavy burden of administrative tasks. In our opinion, the Canadian Army does not have the assurance that Army Reserve soldiers have the current qualifications that they need to be prepared for deployment.

5.69 Before their deployment on any mission, Army Reserve soldiers must update qualifications that are not current or must receive a waiver. In 2015, Army Reserve soldiers were deployed to support provincial authorities in Saskatchewan to fight forest fires, which was a potentially hazardous mission. However, the commander of the operation waived the requirement for medical and physical fitness assessments. In the same year, the Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces noted that the practice of deploying without an assessment of medical fitness may cause soldiers or their team members harm and increase the potential liabilities of the Canadian Armed Forces.

5.70 Recommendation. National Defence should ensure that it has up-to-date information on whether Army Reserve soldiers are prepared for deployment. This information should include civilian qualifications held by Army Reserve soldiers.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. Work is ongoing through the Military Personnel Management Capability Transformation project to maintain all Reserve Force personnel readiness using the future military personnel management tool, Guardian. As part of the project, investigation and analysis will take into account the possibility of including civilian qualifications.

The Canadian Army will make every effort to utilize existing human resource systems to keep data up to date in relation to readiness.

Army Reserve funding was not designed to be consistent with unit training and other activities

5.71 We found that the annual planned funding for the Army Reserve was not consistent with the actual activities undertaken by Army Reserve units. We found that in the 2014–15 fiscal year, $13.5 million in unspent funds from the Army Reserve budget was reallocated to uses other than those of the Army Reserve. We also found that in the 2013–14 fiscal year, National Defence attributed a cost of $166 million to the Army Reserve for the operation of Canadian Army bases through a calculation that was not based on actual use and may have overstated reported expenses of the Primary Reserve.

5.72 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

5.73 This finding matters because the Canadian Army needs to fully fund Army Reserve units’ activities, including training, if the Army Reserve is going to support the Canadian Army. In addition, National Defence needs to clearly understand Army Reserve spending if it is to effectively manage those activities and plan for the future needs of the Canadian Army.

5.74 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 5.80 and 5.84.

5.75 What we examined. We examined annual Canadian Army and Army Reserve operating plans and directives, National Defence financial analysis, and reviews of financial practices. We interviewed National Defence senior managers and command teams of Army Reserve units and brigades.

5.76 Annual Army Reserve funding. Since 2000, the Canadian Army has budgeted annual funding for the Army Reserve on the basis of each soldier participating in unit activities, including individual and collective training, for 37.5 days per year. Annual funding also supports a further 7 days of training, during which the unit trains collectively with other units. Funding for this 7-day training is calculated at a participation rate of half the total number of the unit’s soldiers. More funding for external individual training courses is made available through the Canadian Army’s national training system.

5.77 Local Army Reserve unit activities that are expected to be covered by the 37.5 days of funding include

- individual and collective training within the unit;

- training on National Defence policies, such as sexual harassment and workplace health and safety;

- preparation of training courses;

- administration;

- civic duties in the local community; and

- ceremonial duties.

5.78 We found that the budgeted annual funding for the Army Reserve is not consistent with the actual activities undertaken by Army Reserve units. In 2013, an internal Canadian Army analysis was presented for information purposes to senior Army officers, showing that the 37.5 days was at least 10 days fewer than what Army Reserve units actually used for individual and collective training and other activities. For example, the analysis found that 5 additional training days that were spent on preparing for domestic missions were not included in the allocated 37.5 days. This analysis was not endorsed, and no action has been taken to either acknowledge or address this discrepancy.

5.79 Furthermore, an analysis by the Canadian Army of training in the 2014–15 fiscal year found that at least 44 percent of Army Reserve soldiers had participated in fewer than 25 days of training or other unit activities. We were told that units used some of these unspent funds to increase spending on the activity of other soldiers or other unit activities. This analysis questioned whether the present method of funding Army Reserve units was appropriate and accurate.

5.80 Recommendation. National Defence should ensure that budgeted annual funding for Army Reserve units is consistent with expected results.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Canadian Army assigns resources to ensure that all mandated tasks are funded. We will monitor whether these tasks are consistent with the results expected of them.

5.81 Financial reallocation and reporting. We found that in the 2014–15 fiscal year, the Canadian Army reallocated $8.2 million in unspent funds from the Army Reserve budget for other purposes within the Canadian Army and returned another $5.3 million of the planned budget of the Army Reserve to National Defence. However, during visits to Army Reserve units, we were told that many needs were not being met for training. These included equipment, ammunition, travel, and administrative support.

5.82 National Defence reported to Parliament that it spent $1.2 billion to train and operate the Primary Reserve in the 2013–14 fiscal year. According to the Canadian Armed Forces, $724 million of this amount was to train and operate the Army Reserve. Of that amount, $166 million was attributed to the Army Reserve for the operation of Canadian Army bases. This amount was calculated based on a ratio of the number of Army Reserve soldiers to the number of Regular Army soldiers, not on the use of base facilities. The Canadian Armed Forces does not maintain information on the Army Reserve’s actual use of base facilities. In our opinion, the $166 million estimate is not well supported and may result in providing incorrect information to Parliament by overstating the reported expenses of the Primary Reserve.

5.83 In 2015, to better show the Minister of National Defence the total amount spent on the Primary Reserve, the Chief of the Defence Staff directed that an account be used to record how much money is given to, and spent by, each Reserve Force. National Defence also intends to establish a separate reporting process that will connect assigned funding to expected results.

5.84 Recommendation. National Defence should complete planned changes to the way it reports its annual budgets and the expenses of the Army Reserve, so that National Defence can link assigned funding to expected results.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. National Defence utilizes a financial reporting structure to record how much is allocated to and expended by the Primary Reserves. Commencing 9 February 2016, expenditures related to the Reserve Program were incorporated in the financial reports briefed to senior management. This approach will provide greater visibility on funding and expenditures, and will support enhanced reporting and performance measurement.

Training of Army Reserve soldiers

5.85 Overall, we found that the Canadian Army had designed its training so that Army Reserve soldiers received lower levels of physical fitness training and were not trained for the same number of skills as Regular Army soldiers. We found that some Army Reserve soldiers had not acquired the remainder of these skills before they were deployed. We also found that Army Reserve soldiers had lower levels of training as cohesive teams. Furthermore, we found that collective training for Army Reserve units was not well integrated with the training of the Regular Army units.

5.86 This is important because the Canadian Army needs physically fit, well-trained soldiers who can be deployed, either as individuals or in teams, to meet the challenges of the modern battlefield. Without the complete range of skills, Army Reserve soldiers and their teams are put at risk. Furthermore, the flexibility that commanders need to meet the challenges of domestic and international missions is limited by the skills and experiences of the soldiers under their command.

5.87 Training to build a strong and effective fighting force is the primary task of the Canadian Army. Army Reserve training should prepare soldiers and units to adapt quickly to various types of combat operations, sometimes within minutes. This training should also prepare Army Reserve soldiers to perform effectively on non-combat missions, including domestic deployments (Exhibit 5.5).

Exhibit 5.5—Training should prepare soldiers and units to adapt quickly to various types of non-combat and combat operations

Source: Based on information from National Defence

Exhibit 5.5—text version

This diagram lists the non-combat and combat operations that should be included in the training of Army Reserve soldiers and units. They need this training to be able to adapt quickly to these various operations.

This training includes four categories of non-combat and combat operations: stability operations, enabling operations, defensive operations, and offensive operations.

Preparing soldiers and units to carry out stability operations includes training to

- support civilian infrastructure and governance,

- assist other government agencies,

- provide security and control,

- support disarmament and demilitarization, and

- support reform of security services.

Preparing soldiers and units to carry out enabling operations includes training on

- reconnaissance,

- advancing forces to engage the enemy,

- transportation and logistics,

- security of locations and personnel,

- relief of troops in combat,

- retirement, and

- withdrawal of forces.

Preparing soldiers and units to carry out defensive operations includes training to

- defend positions,

- delay enemy forces, and

- prevent enemy movements.

Preparing soldiers and units to carry out offensive operations includes training on

- attacks,

- raids,

- pursuits,

- deception movements,

- demonstration of strength, and

- breakout from encirclement by the enemy.

5.88 Canadian Army training is an innately dangerous activity. The Canadian Army must balance the risks of training against those of not being fully prepared to deploy on missions. This requires that all soldiers maintain the highest level of physical fitness and that training be systematic and progressively more complex, through individual and collective training, so that soldiers can acquire and confirm their skills.

Army Reserve soldiers received less training than Regular Army soldiers

5.89 We found that neither legislation, nor a program designed to support Reservists while on duty or deployed, covered them for all types of occupational skills training. We also found that compared with the training for Regular Army soldiers, occupational skills training courses for Army Reserve soldiers were not designed to provide all of the skills needed to quickly adapt to various types of combat situations. We further found that pre-deployment training of Army Reserve soldiers for international missions did not always address all known gaps in individual occupational skills training.

5.90 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

- support to attend training courses,

- compensation for employers,

- training programs for individual occupational skills, and

- training for deployment on international missions.

5.91 This finding matters because differences in skills and physical fitness between Regular Army and Army Reserve soldiers limit the ability of Army Reserve units and soldiers to be prepared for missions. These differences also increase the risks of injury to soldiers when they train or deploy. The Canadian Army recognizes that it needs to identify and address these differences before Army Reserve soldiers can deploy on missions and be capable of operating in an integrated Army.

5.92 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 5.96, 5.98, and 5.106.

5.93 What we examined. We examined what steps were taken to enable Army Reserve soldiers to attend training courses. We also examined and compared the individual occupational training programs of the Regular Army and the Army Reserve for infantry, armoured crewmen, and electrical mechanical engineers. Furthermore, we examined Army Reserve soldiers’ records of training for deployment on international missions. We examined documents, observed training, and interviewed senior managers and command teams of Army Reserve units as well as instructors and trainees at training schools.

5.94 Support to attend training courses. National Defence has taken several steps to enable Army Reserve soldiers to attend training courses. For example, National Defence works with the Canadian Forces Liaison Council to encourage employers and educational institutions to provide leaves of absence when necessary for training and deployment. The Canadian Army also uses training modules, simulation training, and distance learning to help Army Reserve soldiers balance their training with their civilian schedules. However, we found that from 2011 to 2013, 47 training courses were cancelled, 23 because of a lack of candidates.

5.95 National Defence noted that job protection legislation for Army Reserve soldiers who take time off from civilian employment for military training or duty differs across the country. We found that federal legislation does not provide job protection for all Army Reserve training. The Canada Labour Code and the Reserve Forces Training Leave Regulations under the National Defence Act permit absences for some types of training, such as annual training with the soldier’s unit, training for a specific deployed operation, or leave to attend training for promotion. However, the Code and the Regulations do not provide leave for Army Reserve soldiers to undertake all types of occupational skills training.

5.96 Recommendation. National Defence should work with departments and agencies that have responsibility under the Canada Labour Code and the Reserve Forces Training Leave Regulations to consider including coverage of absences to attend all types of occupational skills training into the Code and the Regulations.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. National Defence will consult with the Public Service Commission of Canada and other applicable agencies to determine whether changes to federal job protection legislation can be justified.

5.97 Compensation for employers. In November 2014, National Defence announced that it planned to introduce a program to compensate civilian employers and self-employed Reserve personnel to help offset costs incurred by employers when a person in the Primary Reserve is absent from work on designated domestic or international deployments. The amount is about $400 for each week of absence. We found that this program did not compensate employers when a Reserve Force soldier attends occupational skills training. The compensation program is thus not able to support the full participation of Army Reserve soldiers in training for Army missions.

5.98 Recommendation. National Defence should consider amendments to its proposed Compensation for Employers of Reservists Program to include absences for all occupational skills training of Army Reserve soldiers.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. Only once the original program is fully implemented and institutionalized will National Defence undertake an evidence-based feasibility study on the expansion of the Compensation for Employers of Reservists Program to include leave for occupational and career training courses, including associated training activities required for career progression.

5.99 Training programs for individual occupational skills. The Canadian Army has taken steps to align standards for individual occupational skills training received by Army Reserve and Regular Army soldiers to allow all of them to acquire the same level of competence for a particular skill. However, we found that individual occupational courses for Army Reserve soldiers were designed so that they graduated from their initial occupational courses with fewer professional and leadership skills than their Regular Army counterparts.

5.100 For example, Regular officers’ initial military training is 70 days. Its objective is to produce an “operationally focused and physically robust graduate who will be able to perform their responsibilities” as a professional soldier and leader of a small team in simple operations. However, the course that Reserve officers attend is 32 days and has significantly less training in important skills such as physical fitness, administration, and leadership of operations and subordinates. Similarly, a Regular Force non-commissioned member receives 60 days of training that include developing leadership skills and extensive physical fitness training. An Army Reserve non-commissioned member receives 23 days of training that does not include these elements.

5.101 Army Reserve soldiers are trained for a specific occupation, such as infantry, armour, artillery, logistics, communications, or electrical mechanical engineering. However, we found that this training was often limited to a narrower set of individual occupational skills than the training provided to Regular Army soldiers. For example, the Army Reserve infantry training course that provides non-commissioned members (excluding officers) with fighting skills requires 35 training days, compared with 62 training days for their Regular Army counterparts. This difference means that these Army Reserve infantry soldiers are not certified to use several weapons (anti-tank and anti-personnel weapons) that the Canadian Army considers necessary for infantry teams of 25 to 40 soldiers (Exhibit 5.6).

Exhibit 5.6—Non-commissioned Army Reserve infantry soldiers receive less initial weapons training than Regular Army infantry soldiers

| Weapons training provided during infantry training course for non-commissioned members (excluding officers) | Regular Army infantry training | Reserve Army infantry training |

|---|---|---|

| Personal weapon (rifle) | Provided | Provided |

| Pistol | Provided | Not provided |

| Light machine gun | Provided | Provided |

| General-purpose machine gun | Provided | Provided |

| Hand grenades | Provided | Provided |

| Grenade launcher | Provided | Not provided |

| Short-range anti-armour weapon (light) | Provided | Not provided |

| Short-range anti-armour weapon (medium) | Provided | Not provided |

| Command-detonated explosive | Provided | Not provided |

Source: Based on information from National Defence

5.102 We also found that this lack of individual occupational skills training continued through later career courses. For example, courses for senior leaders of infantry Army Reserve units did not include instruction in key skills such as commanding operations with armoured fighting vehicles, conducting operations in urban areas, and working in command posts. We found that Army Reserve infantry soldiers received 25 percent fewer days of formal individual skills training over their careers than did their Regular Force counterparts.

Army Reserve soldiers were deployed to Eastern Europe in 2015.

Photo: National Defence

5.103 Training for deployment on international missions. The Canadian Army has recognized that it needs to address gaps during the pre-deployment training of Army Reserve soldiers for international missions.

5.104 The importance of addressing all gaps in individual training during pre-deployment training was noted in a 2014 inquiry into a 2010 training incident in Afghanistan in which four Army Reserve soldiers were injured and one was killed. The casualties occurred while the soldiers were training to operate a particular weapon that was part of the mission’s equipment but had not been included in pre-deployment training. The inquiry concluded that the lack of this pre-deployment training contributed to this incident.

5.105 More recently, Canadian Armed Forces soldiers began to deploy as part of NATO’s collective defence in Eastern Europe. When we examined pre-deployment training records for one rotation, the records confirmed that Army Reserve soldiers had completed training on a range of weapons. However, for another rotation, confirmation existed only for their personal weapons. In both cases, a gap remained in the weapons training between Army Reserve and Regular Army soldiers before they deployed on international missions.

5.106 Recommendation. National Defence needs to ensure that training of Army Reserve soldiers for international deployments addresses all known gaps in individual occupational skills training.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Canadian Army already provides sufficient detail to ensure that Army Reserve soldiers are trained to the level required for employment on domestic and international missions. The Army ensures that Reserve soldiers are trained to their occupational function point within their trade and that continuation training is provided annually to enable those soldiers to operate in platoon- and company-level operations. Gaps or deficiencies in skills are identified during the pre-deployment training phase, and the designated Commanders assess and determine how those gaps will be rectified (through individual training courses or collective level training at the deploying unit level). Once deployed, whether Regular or Reserve, the unit will conduct refresher or continuation training to ensure skill proficiency is maintained. If a new task or piece of equipment is identified, the deployed unit Commander will provide the level of training as required. The Canadian Army will ensure the training records of individual soldiers are kept up to date and will continue to explore ways to minimize all known skill gaps.

Army Reserve and Regular Army unit training were not fully integrated

5.107 We found that the level of collective training of Army Reserve units was designed to be less than the Canadian Army’s required level of collective training which is vital for success when deployed. We also found that Army Reserve unit training was not fully integrated with that of Regular Army units.

5.108 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

5.109 This finding matters because the Canadian Army has stated that it needs Army Reserve units to train soldiers who can be deployed as part of an integrated Army to meet assigned missions.

5.110 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 5.119.

5.111 What we examined. We examined the Canadian Army’s requirements and reports of collective training of Army Reserve units. We also examined how this training was aligned with the three-year training cycle of the Regular Army.

5.112 Collective training. The Canadian Army has identified that it is critical to ensure that its soldiers train to work together in a larger team of up to 150 soldiers or more, with many different kinds of equipment. Regular Army units train to this level to have all the skills they require for fighting as an integrated team that can quickly adapt to various combat situations. We found that by design, Army Reserve units train for fewer skills, in smaller teams of 25 to 40 soldiers, and with less access to equipment.

5.113 We also found that in meeting their collective training requirements, some Army Reserve units did not follow the Canadian Army’s requirement that all training be both progressive and safe. During our audit work, it came to our attention that five Army Reserve post-exercise reports between 2013 and 2015 stated that collective training was not always progressive and raised safety concerns. For example, in one case, contrary to the Canadian Army’s guidance, units conducted a live-fire exercise without “walking” their soldiers through the exercise beforehand.

Regular Army soldiers instruct and coach Army Reserve soldiers on tactics and skills during an exercise at Canadian Forces Base Petawawa.

Photo: Office of the Auditor General of Canada

5.114 We also found that the process used to confirm that Army Reserve units had achieved the required level of training was inconsistent. We asked 10 units across all Divisions for information confirming that the units had achieved their required levels of training. We found that the quality of confirmations varied greatly, from well documented to not documented. In six cases, there was no documentation to show that the units had achieved the required level of training. In our opinion, without a consistent and documented confirmation process, the Canadian Army does not have full assurance that all Army Reserve units have achieved the level of collective training they need to progress to higher levels of collective training, including pre-deployment training for international missions.

5.115 We found that the Canadian Army has taken some steps to improve the collective training of Army Reserve soldiers. For example, we observed a recent large-scale exercise involving over 1,000 Army Reserve soldiers from across Ontario that included Regular Army soldiers instructing and coaching Army Reserve soldiers on the tactics and skills that they would need to deploy in a combat role.

5.116 Integrating Army Reserve training with Regular Army training. We found that the collective training requirements for Army Reserve units were not integrated into the three-year training cycle of the Regular Army. Analysis conducted in 2015 by the Canadian Army concluded that integration into the training cycle of the Regular Army would ensure that the Army Reserve’s training for domestic and international missions would be conducted in a progressive and predictable manner and provide formal confirmation of that training. The analysis also noted that this enhanced training would increase the retention of Army Reserve soldiers.

5.117 As previously mentioned, the Army Reserve is expected to provide up to 20 percent of soldiers being deployed on major international missions. Army Reserve soldiers are deployed as individuals placed in Regular Army units or in Army Reserve teams that provide key tasks, such as Convoy Escort, Force Protection, Persistent Surveillance, and Influence Activities. However, the Canadian Army has determined that, with the exception of Influence Activities, these key tasks would have to be performed by Regular Army soldiers during the initial rotation. This is because the training of Army Reserve units has not been integrated into the Regular Army’s training plan to prepare for Canada First Defence Strategy missions.

5.118 In 2009, the Canadian Army took steps to integrate the collective training of Army Reserve and Regular Army units in the same Division. This integration was to be achieved by linking units that perform the same combat operations—for example, Army Reserve infantry units with Regular Army infantry units. These pairings were to help develop command and control relationships, and joint training, which would ensure that Army Reserve units were prepared to meet assigned tasks. However, we found that, with the exception of artillery units, this has not happened.

5.119 Recommendation. National Defence should improve the collective training and integration of Army Reserve units with their Regular Army counterparts so that they are better prepared to support deployments.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Canadian Army is taking the necessary steps to develop opportunities for stronger integration between the Regular Army and the Reserve Force.

Conclusion

5.120 We concluded that although Army Reserve units received clear guidance for domestic missions, the Canadian Army did not require Army Reserve groups to formally confirm that they were prepared to deploy on domestic missions. Army Reserve units and groups did not always have access to key equipment. At the same time, Army Reserve units lacked clear guidance on preparing for international missions, had lower levels of training as cohesive teams, and had not fully integrated this training with that of the Regular Army.

5.121 We concluded that the Army Reserve did not have the number of soldiers it needed and lacked information on whether soldiers were prepared to deploy when required. The number of Army Reserve soldiers has been steadily declining because the Army Reserve has been unable to recruit and retain the soldiers it needs. Furthermore, funding was not designed to fully support unit training and other activities.

5.122 We concluded that Army Reserve soldiers received lower levels of physical fitness training and were not trained in the same number of skills as Regular Army soldiers. We found that some Army Reserve soldiers had not acquired the remainder of these skills before they were deployed.

About the Audit

The Office of the Auditor General’s responsibility was to conduct an independent examination of National Defence’s Canadian Army Reserve to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs. National Defence is responsible for the readiness of the Canadian Army (Regular Force and Army Reserve) and ensures that all members and units of the Army Reserve are trained and equipped so that they are prepared for assigned missions.

All of the audit work in this report was conducted in accordance with the standards for assurance engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance. While the Office adopts these standards as the minimum requirement for our audits, we also draw upon the standards and practices of other disciplines.

As part of our regular audit process, we obtained management’s confirmation that the findings in this report are factually based.

Objective

The objective of the audit was to determine whether the Army Reserve is ready to deploy for domestic and international missions. (Ready means to be prepared.) The sub-objectives included whether

- National Defence assigned missions and objectives to the Army Reserve and its units with the necessary resources,

- Army Reserve units had the capacity to accomplish assigned missions, and

- Army Reserve personnel and units were trained to be combat-capable and to achieve their assigned missions.

Scope and approach

The audit scope included National Defence and focused on the Canadian Army Reserve.

We examined National Defence operational plans, data, and reports, including the funding of Army Reserve units. We also examined the performance of the recruiting system for the Army Reserve. We examined guidance and observed training, and interviewed senior Canadian Army commanders, command teams of Army Reserve units, and Army Reserve soldiers.

When we used representative sampling for analyzing Army Reserve soldiers’ reports of injury, disease, illness, or exposure to toxic material, sample sizes were sufficient to report on the sampled population with a confidence level of 90 percent and a margin of error of less than +10 percent.

Criteria

To determine whether National Defence assigned missions and objectives to the Army Reserve and its units with the necessary resources, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

National Defence assigns clear missions to all Army Reserve units, which contributes to an integrated, multi-purpose, and combat-capable military. |

|

|

National Defence allocates resources to the Army Reserve to achieve National Defence and Canadian Army objectives and manages risks to readiness targets, force generation, and equipment needs. |

|

|

National Defence monitors Army Reserve performance and takes appropriate action to ensure that the Army Reserve can meet assigned missions. |

|

To determine whether Army Reserve units had the capacity to accomplish assigned missions, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Army Reserve units have the people they need to be effective (for example, unit strength and attending members). |

|

|

Army Reserve units enrol sufficient numbers of recruits. |

|

|

Army Reserve units retain the people they need (for example, trainers and command staff). |

|

|

Army Reserve units have access to the equipment they need to accomplish assigned missions. |

|

To determine whether Army Reserve personnel and units were trained to be combat-capable and to achieve their assigned missions, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

National Defence defines individual training requirements to achieve a combat-capable reserve force. |

|

|

Army Reserve personnel receive the opportunities and resources they need to achieve individual training requirements. |

|

|

Individual members of the Army Reserve meet the training requirements for their trade, rank, and deployment. |

|

|

Army Reserve units receive the collective training they need to accomplish assigned missions. |

|

Management reviewed and accepted the suitability of the criteria used in the audit.

Period covered by the audit

The audit examined the period covered by the 2012–13, 2013–14, and 2014–15 fiscal years, and reached back over longer periods, as required, to gather evidence to conclude against criteria. Relevant observations up to January 2016 were also included. Audit work for this report was completed on 26 January 2016.

Audit team

Assistant Auditor General: Jerome Berthelette

Principal: Gordon Stock

Director: Craig Millar

Françoise Bessette

Glenn Crites

Julie Hudon

John McGrath

List of Recommendations

The following is a list of recommendations found in this report. The number in front of the recommendation indicates the paragraph where it appears in the report. The numbers in parentheses indicate the paragraphs where the topic is discussed.

Guidance on preparing for missions

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

5.22 National Defence should provide individual Army Reserve units with clear guidance so that they can prepare their soldiers for key tasks assigned to the Army Reserve for major international missions. (5.18–5.21) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. Providing the necessary training to soldiers before they participate in international deployments is of paramount importance to the Canadian Army. Guidance regarding the required training is provided in the Army’s annual operation plan. Once Reserve participation in a given expeditionary operation is announced, specific direction is given with respect to the training required for individuals and for designated Reserve Teams (to conduct tasks such as Convoy Escort, Force Protection, and Persistent Surveillance). Every Team is “confirmed” through a deliberate process before being given the green light to deploy. The Army will work toward improving its guidance for anticipated key tasks for major international missions. |

|

5.32 The Canadian Army should define and provide access to the equipment that Army Reserve units and groups need to train and deploy for domestic missions. (5.28–5.31) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. A procurement plan is under way to address the shortages within certain fleets. The Canadian Army has defined and provides the equipment required to conduct domestic operations. The majority of this equipment is held either within the unit or with the Canadian Brigade Group. When a specific requirement or gap is identified that is not within the Brigade Group, the Division will reallocate from within its own resources or will request additional items from national stocks. |

|

5.34 The Canadian Army should require Army Reserve groups to formally confirm that they are prepared to support domestic missions. (5.33) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Canadian Army will review the process and develop a better-documented confirmation method. The Army conducts training on an annual basis for the 10 Territorial Battalion Groups and the four Arctic Company Response Groups. This training may be verbally confirmed through the chain of command, which is found to be sufficient for training objectives. |

Sustainability of Army Reserve units

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

5.57 National Defence should design and implement a retention strategy for the Army Reserve. (5.46–5.56) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. Retention enables Canadian Armed Forces’ operational and institutional excellence. National Defence will develop and implement a Canadian Armed Forces retention strategy that will ensure retaining our members in uniform is a fundamental aspect of how we manage our people, and is given equal, if not greater, prominence in our attraction and recruiting efforts. Our approach going forward will be comprehensive and incorporate the Regular and Reserve Force, creating greater mobility between these components and accounting for the range of requirements inherent in each. While consideration will be given to transactional requirements in the areas of compensation and benefits, National Defence will develop effective measures including, but not limited to, career management, family support, mental health and wellness support, and diversity requirements. The Canadian Army is developing a retention strategy for the Army Reserve, and is in the process of updating the strategy based on Chief Military Personnel initiatives. |

|

5.62 National Defence should review the terms of service of Army Reserve soldiers, and the contracts of full-time Army Reserve soldiers, to ensure that it is in compliance with the National Defence Act. (5.58–5.61) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Canadian Armed Forces will review the framework for the Reserve Force terms of service and the administration of Reserve Force service to ensure it complies with the National Defence Act and the regulations enacted under it. |

|

5.65 National Defence should review its policies and clarify Army Reserve soldiers’ access to medical services. (5.63–5.64) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Canadian Forces Health Services Group Headquarters is actively advancing a number of initiatives to review and support policies for medical assessments that contribute to Primary Reserve soldiers’ overall readiness for training and deployment, and that clarify access to medical services, including

|

|

5.70 National Defence should ensure that it has up-to-date information on whether Army Reserve soldiers are prepared for deployment. This information should include civilian qualifications held by Army Reserve soldiers. (5.66–5.69) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. Work is ongoing through the Military Personnel Management Capability Transformation project to maintain all Reserve Force personnel readiness using the future military personnel management tool, Guardian. As part of the project, investigation and analysis will take into account the possibility of including civilian qualifications. The Canadian Army will make every effort to utilize existing human resource systems to keep data up to date in relation to readiness. |

|

5.80 National Defence should ensure that budgeted annual funding for Army Reserve units is consistent with expected results. (5.76–5.79) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Canadian Army assigns resources to ensure that all mandated tasks are funded. We will monitor whether these tasks are consistent with the results expected of them. |

|

5.84 National Defence should complete planned changes to the way it reports its annual budgets and the expenses of the Army Reserve, so that National Defence can link assigned funding to expected results. (5.81–5.83) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. National Defence utilizes a financial reporting structure to record how much is allocated to and expended by the Primary Reserves. Commencing 9 February 2016, expenditures related to the Reserve Program were incorporated in the financial reports briefed to senior management. This approach will provide greater visibility on funding and expenditures, and will support enhanced reporting and performance measurement. |

Training of Army Reserve soldiers