2017 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada Independent Audit ReportReport 2—Customs Duties

2017 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of CanadaReport 2—Customs Duties

Independent Audit Report

Introduction

Background

2.1 Individuals and businesses that import goods, such as automobiles and dairy products, into Canada are responsible for paying customs duties according to Canada’s Customs Tariff. Customs duties are a way for the federal government to obtain revenue and protect certain sectors of the Canadian economy. In the 2015–16 fiscal year, customs duties accounted for about $5.4 billion (1.8 percent) of all federal revenue.

Most-favoured-nation tariff treatment—Granting a special favour that was granted to one trading partner (such as a lower customs duty rate for one of its products) to all other members of the World Trade Organization. Under World Trade Organization agreements, countries cannot normally discriminate among their trading partners. However, under the 1979 Enabling Clause, World Trade Organization countries are allowed to unilaterally offer tariff preferences below most-favoured-nation rates to developing and least developed countries.

2.2 Among other things, the Customs Tariff lists the goods on which a duty is imposed when they are imported into Canada, together with the rates at which such goods are taxed. When setting the amount of duties to charge on imported goods, the government needs to consider the different impacts the duties will have. These impacts include how much revenue the government will receive, which domestic businesses will have more or less competition from foreign businesses, Canada’s international obligations, and whether Canadian consumers will pay more or less for imported goods.

2.3 The federal government changes its customs duties either by entering into trade agreements or by unilaterally removing duties. The government may choose to improve the competitiveness of, or reduce the administrative burden on, Canadian businesses. Or it may choose to change customs duties because of the impact on Canadian consumers. In 2015, close to 70 percent of all tariff items were duty-free under the most-favoured-nation tariff treatment.

2.4 Canada Border Services Agency. The Canada Border Services Agency administers more than 90 acts, regulations, and international agreements for federal organizations, the provinces, and the territories. It is responsible for assessing the duties and taxes owed to the Government of Canada. The Agency has a competing mandate—it must ensure the security of the border while facilitating the flow of goods and people.

2.5 Department of Finance Canada. The Department of Finance Canada is responsible for

- the Customs Tariff and several of its orders and regulations, as well as the policy aspects of the Postal Imports Remission Order and the Courier Imports Remission Order;

- developing and implementing policies on trade and tariffs; and

- providing analysis, research, and advice on the government’s international trade and finance policy agenda.

2.6 Global Affairs Canada. Global Affairs Canada is responsible for controlling the import of goods for which Canada requires an import permit, such as beef, chicken, and dairy products. The goods are listed on the Import Control List found in the Export and Import Permits Act.

2.7 Importers. Importers are responsible for correctly classifying and valuing the goods they bring into Canada so that the Canada Border Services Agency can properly assess duties, collect statistics, and determine whether all legal requirements are met. Importers are responsible for paying duties and complying with legislation and regulations. However, importers may hire professional agents—called customs brokers—to help them.

2.8 Importers must classify goods imported into Canada according to the Customs Tariff. There are 7,403 classes of goods listed in the Schedule to the Customs Tariff, down from over 8,500 before 2011. These classes are based on the international Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding System of the World Customs Organization. Importers must assign a 10-digit classification number to identify the imported good. The first six digits of the classification number are established by the World Customs Organization. Canada requires the next two digits to identify some goods with precise rates of duty. It also requires two additional digits to collect statistical information that is used in developing economic policy and negotiating trade agreements.

Focus of the audit

2.9 This audit focused on whether the Department of Finance Canada, Global Affairs Canada, and the Canada Border Services Agency adequately managed customs duties according to their roles and responsibilities.

2.10 This audit is important because for customs duties to balance the different interests of market participants, government organizations must faithfully implement the customs duty system.

2.11 We did not examine the security and safety of imported goods to Canada, free trade agreements, exports, or the supply management program.

2.12 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Assessing customs duties

The Canada Border Services Agency was unable to assess all customs duties owed to the government

Overall message

2.13 Overall, we found that the Canada Border Services Agency was unable to accurately assess all customs duties owed to the government on goods coming into Canada. This was due in part to the Agency’s self-assessment system, which may have allowed importers to be non-compliant with import rules and regulations, and in part to the Agency’s own internal challenges relating to staffing.

2.14 Descriptions of goods on the import forms were often incomplete or incorrect, making it more difficult for the Agency to know exactly what was imported. Through its compliance verifications on specific goods, the Agency established that importers misclassified about 20 percent of those goods coming into Canada and may have ended up paying a lesser amount of duty as a result. In addition, importers could submit changes to their import form information up to four years after their goods were imported. Because the Agency did not examine or sample all shipments before release, it had to rely on the importers’ accounting information and supporting documentation, making it hard for the Agency to verify whether the requested changes were appropriate. In the 2014–15 fiscal year, the Agency paid $136 million in refunds to importers as a result of retroactive changes to import forms.

2.15 These findings matter because when the Canada Border Services Agency fails to accurately assess customs duties, the Government of Canada might lose revenue. The Agency’s verifications indicated lost revenues from misclassifications. For example, in targeted verifications conducted in the 2015–16 fiscal year, the Agency identified that the importers should have paid $42 million more, of which approximately half was due to misclassification.

2.16 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

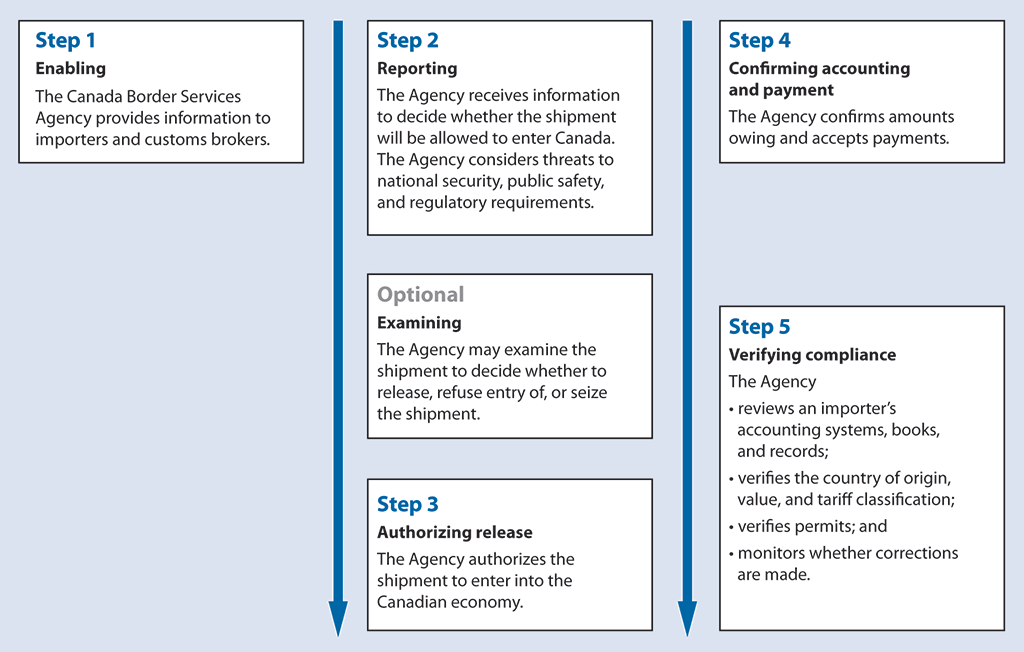

2.17 The import process has five steps (Exhibit 2.1).

Exhibit 2.1—Importing commercial goods into Canada has five steps

Note: This process applies to imported goods for which duties do not need to be paid in advance—the case for most imports.

Source: Based on information from the Canada Border Services Agency

Exhibit 2.1—text version

This diagram outlines the five-step process followed by the Canada Border Services Agency when commercial goods are imported into Canada.

Step 1—Enabling. The Agency provides information to importers and customs brokers.

Step 2—Reporting. The Agency receives information to decide whether the shipment will be allowed to enter Canada. It considers threats to national security, public safety, and regulatory requirements.

Optional step—Examining. The Agency may examine the shipment to decide whether it should be released, refused entry, or seized.

Step 3—Authorizing release. The Agency authorizes the shipment to enter into the Canadian economy.

Step 4—Confirming accounting and payment. The Agency confirms amounts owing and accepts payments.

Step 5—Verifying compliance. The Agency reviews an importer’s accounting systems, books, and records; verifies the country of origin, value, and tariff classification; verifies permits; and monitors whether corrections are made.

Note: This process applies to imported goods for which duties do not need to be paid in advance—the case for most imports.

Source: Based on information from the Canada Border Services Agency

2.18 Our recommendations in these areas of examination appear at paragraphs 2.32, 2.35, and 2.41.

2.19 What we examined. We examined whether the Canada Border Services Agency verified that the duties owed by importers to the federal government were correct.

2.20 Long-standing compliance issues. Over the years, the Canada Border Services Agency has conducted random and targeted verifications to assess whether importers have complied with the government’s import rules. The Agency used statistical sampling to select imports for random verification. For targeted verifications, it selected imports it believed were at high risk for non-compliance. One of the key risk factors used in making its selections was the risk that the wrong amount of duty was paid.

2.21 Over the last 15 years, the Agency’s compliance verifications on specific goods revealed that importers misclassified imported goods more than 20 percent of the time. When an importer misclassifies goods on which duty should be paid, the importer will pay too little or too much duty. We found that, despite the high rate of misclassifications, the Agency did not estimate the overall value of errors in the duties importers paid.

2.22 However, while the Agency did not know the overall value of the errors, the results of some of its verifications indicated lost revenues from misclassifications. For example, in targeted verifications conducted in the 2015–16 fiscal year, the Agency identified that the importers should have paid $42 million more, of which approximately half was due to misclassification.

2.23 We identified two reasons that may have allowed importers to be non-compliant. First, the Agency’s controls over imports were not working, and second, it appeared that some importers could circumvent the rules to their own advantage.

2.24 Controls not working. The deficiencies in the Agency’s controls included

- incorrect or poor-quality descriptions of goods on import forms, which were not useful to the Agency;

- no assessments of individual customs brokers to determine whether they applied import rules accurately; and

- penalties that were too low to be effective at making importers comply with the import rules.

2.25 Descriptions of imported goods. When an importer brings goods into Canada, it must assign a tariff classification number. The importer may also fill in a field that describes the goods being imported. We used software to analyze 2.5 million import records for the period from January to March 2016. We wanted to determine whether importers assigned a tariff classification number that matched the description of the goods importers gave on import forms.

2.26 We found that the descriptions often indicated that many types of goods were imported, but the importer assigned only one tariff classification number to all of the goods—sometimes more than 50 descriptions were associated with a single number. Although this might have been an indication that wrong numbers were frequently used, we determined that it was impossible to assess the appropriateness of the numbers that importers assigned to these records, and we had to remove 1.1 million records (44 percent) from our analysis.

2.27 We examined the remaining 1.4 million records, each of which contained only one narrative description and a single classification number. We found that 74 percent of them did not provide a description that allowed us to determine whether the number used was the right one. For example, we found almost 30,000 records where the description was “sets” or “kits,” without any other description. This led us to conclude that the information the Agency collected about product descriptions was of such poor quality that it offered very little value to the Agency. In fact, according to the Agency, the only way to determine exactly what was imported was to look at the tariff classification and the supporting documentation (for example, commercial invoices or product specifications). The description field was not intended to be used to determine the appropriate amount of duties to pay.

2.28 In our opinion, if the Agency does not collect accurate descriptions of the imported goods at the time of import, it is more difficult to know exactly what was imported, and to know whether the right amount of duty was assessed. But for importers, the time it takes to fill out the description field might represent extra costs.

2.29 Customs brokers. There are 286 licensed customs brokers in Canada. They have experience applying Canada’s complex import rules, and many importers hire a broker to help them apply the rules. We found that 68 percent of import transactions were administered by a broker. While brokers help importers submit import information, it is the importer that is responsible to ensure the information is accurate.

2.30 We found that, despite long-standing compliance issues with the government’s import rules by the importing community, the Canada Border Services Agency did not evaluate the accuracy of import information provided by individual brokers, nor assess individual broker performance.

2.31 The Agency has the power to suspend or cancel a broker’s licence; however, it has rarely suspended a licence over concerns about a broker’s competency. It is important that the Agency monitor brokers and use its enforcement power to improve the quality of the import information submitted. This would be consistent with the recommendation of the World Customs Organization that importers and their agents share the responsibility for providing accurate information.

2.32 Recommendation. The Canada Border Services Agency should review its customs brokers licensing regime by considering features such as

- a licensing process that requires periodically assessing a broker’s compliance record, and

- shared liability of licensed customs brokers and importers to comply with import requirements and paying duties and taxes.

The Agency’s response. Agreed. The Canada Border Services Agency will conduct a review of the customs broker licensing regime. While the Customs Act defines liability for compliance with the import process and for the payment of duties and taxes, the Agency acknowledges that there are opportunities to review this regime in order to ensure that it enables the Agency to effectively manage duties and taxes. In recent years, the Agency has conducted reviews of its broker licensing regime as part of both internal evaluations as well as external consultations. The Agency continues to further review this regime as part of its Commercial Transformation Initiative and in the development of the Canada Border Services AgencyCBSA Assessment and Revenue Management (CARM) project solution. These actions will be completed by September 2018.

2.33 Penalties. The Canada Border Services Agency can charge a penalty to non-compliant importers, but we found that the penalties were probably too low to improve importer compliance. There were three levels of penalties for importers that provided inaccurate or incomplete information on permits, certificates, licences, documents, or declarations of imported goods:

- $150 for the first offence,

- $225 for the second offence, and

- $450 for third and subsequent offences.

2.34 In the 2014–15 fiscal year, the Agency charged 16,000 penalties—less than one tenth of one percent of the transactions for that year. In the 2015–16 fiscal year, total revenue from penalties was $4.4 million, for an average penalty of $151.

2.35 Recommendation. The Canada Border Services Agency should review its penalties in order to better protect import revenues and ensure compliance with trade programs.

The Agency’s response. Agreed. The Canada Border Services Agency’s Programs Branch will explore further measures aimed at creating a meaningful deterrent to importer non-compliance related to the evasion of import revenues and ensuring compliance with trade programs. This will be completed by June 2018.

2.36 Changing import forms. We believe that the Agency’s self-assessment system may have allowed importers to be non-compliant with the import rules and regulations and that importers may have taken advantage of the rules about changing import forms.

2.37 To facilitate trade, when goods arrived at a border, the Agency did not always inspect them and importers might not have had all the necessary import forms. This meant that the Agency did not compare the goods with the information on the import form or on the invoice when the goods arrived at the border—it usually released the goods for delivery to their destination. Generally, within five business days after release, the Agency confirmed the amount owing of duties and taxes. Importers could pay duties and taxes monthly.

2.38 The legislation allowed importers to change the information on their import forms up to four years after the goods were imported, but because the Agency did not collect meaningful information about what was imported at the time the goods crossed the border, it was hard for the Agency to verify whether an importer’s change was appropriate. According to the Agency, the longer an importer had to file an adjustment, the more likely the changes were inappropriate.

2.39 We found that the Agency did not know the number of retroactive changes importers made to import forms for a given year. However, the Agency told us that in the 2014–15 fiscal year, importers initiated about 200,000 adjustments, resulting in the Agency’s paying importers $136 million in refunds. Conversely, importers made about 20,000 adjustments that resulted in payments of $55 million to the Agency.

2.40 In our view, this situation allowed importers to circumvent paying required duties.

2.41 Recommendation. Unless otherwise specified in a free trade agreement, the Canada Border Services Agency should review the period allowed for retroactive changes on the import form, without compromising the Agency’s ability to conduct compliance verifications.

The Agency’s response. Agreed. In consultation with its legal services, the Canada Border Services Agency will conduct a review of the current framework that allows for retroactive changes on the import form. The Agency will develop options to reduce the period allowed for the importer to make corrections while preserving the Agency’s ability to conduct compliance activities. These actions will be completed by December 2019.

2.42 Agency resources. The Agency estimated that for the 2015–16 fiscal year, each additional compliance officer could have identified unassessed customs duties, taxes, and interest totalling 4 to 11 times their individual salaries. This indicated that the Agency believed it was not at an optimal resourcing level to implement the customs duty system.

Controlling goods

Overall message

2.43 Overall, we found that the Canada Border Services Agency and Global Affairs Canada did not work together to adequately manage the limits on quota-controlled goods coming into Canada. We estimated that in 2015, the Agency should have assessed $168 million of customs duties on imports of quota-controlled goods that exceeded volume limits. These goods included dairy, chicken, turkey, beef, and eggs. Also, some goods, imported under the Duties Relief Program, were diverted into the Canadian economy, rather than exported as required by the program. The Agency did not ensure that these diverted goods, such as chicken, were reported to the Agency and the applicable duties paid as required.

2.44 These findings matter because one of the objectives of customs duties is to protect certain Canadian markets by limiting the imports of goods that compete with Canadian products.

2.45 Quota-controlled goods coming into the country are specific goods on which Canada applies tariff rate quotas—essentially a two-tier level of customs duty rates—to control the volume of the goods. Examples of quota-controlled goods are dairy, chicken, turkey, beef, and egg products. A tariff rate quota sets the volume of a good that can be imported into Canada at a lower rate of duty. Once that volume has been imported into the country, duties on any subsequent imports of the same good are applied at a higher rate.

2.46 Goods subject to tariff rate quotas are listed in the Import Control List of the Export and Import Permits Act. Importers must obtain a permit from Global Affairs Canada to bring these goods into Canada. If the importer does not have a permit to import a quota-controlled good when it enters Canada, the Canada Border Services Agency gives the importer five days to get one from Global Affairs Canada.

2.47 The Duties Relief Program, administered by the Agency, allows participating companies to import goods without paying duties as long as those goods are later exported. As part of the program, companies can manufacture or use the goods in a limited manner before export.

Quota-controlled goods were imported without required permits, leading to $168 million in unassessed duties

2.48 We found that in 2015, importers brought quota-controlled goods into Canada without permits and without paying the right amount of customs duties. These quota-controlled goods included dairy, chicken, turkey, beef, and egg products, for which the importers would have paid $168 million in customs duties if the Canada Border Services Agency had compared the permit information with the import form.

2.49 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topic:

2.50 This finding matters because the integrity of the tariff rate quota system depends on the government’s ability to ensure that all importers follow all applicable rules and regulations.

2.51 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 2.55.

2.52 What we examined. We examined whether the Canada Border Services Agency and Global Affairs Canada ensured that tariff rate quotas were respected.

2.53 Enforcing permits for quota-controlled goods. The Agency recorded the permit information of the quota-controlled good in one system and the information on duties and taxes in a different system. This meant that the permitted volume and the actual volume of the imported quota-controlled goods were kept in two different systems and were rarely compared.

2.54 While Global Affairs Canada was responsible for issuing authorizations, certificates, and permits for those items that were on the Import Control List, we found that it did not match the volumes authorized for importing annually with the volumes that importers declared to the Agency as eligible for a lower rate of duty. We did our own analysis for the 2015 calendar year and compared the volume permitted by Global Affairs Canada with Statistics Canada’s import data. Our analysis indicated that it is probable that importers brought a significant volume of controlled goods into Canada without a permit and without paying the appropriate customs duties. From our analysis, we estimated $168 million of unassessed duties on $131 million worth of chicken, turkey, beef, eggs, and dairy products that were imported without the appropriate permits (Exhibit 2.2). According to the Agency, seven to eight percent of chicken, turkey, beef, eggs, and dairy products were therefore imported without the appropriate permits, representing a significant loss of revenue due to unassessed customs duties and representing a cost to the domestic industry.

Exhibit 2.2—In 2015, $168 million of customs duties on quota-controlled goods were not assessed

| Categories of quota-controlled goods | Estimated value of unassessed customs duties ($ millions) |

Estimated value of quota-controlled goods entering the Canadian economy without permits ($ millions) |

|---|---|---|

| Dairy | 81 | 32 |

| Chicken | 50 | 20 |

| Turkey | 15 | 9 |

| Beef | 11 | 41 |

| Eggs | 11 | 29 |

| Total | 168 | 131 |

Note: These calculations are based on the value of the goods that importers declared to Global Affairs Canada. These numbers are unaudited. Except for beef, the controlled goods listed above are usually subject to high duty rates when exceeding volume limits. Sometimes duty rates may be higher than 100 percent of the value of the good.

Source: Based on data from Global Affairs Canada and Statistics Canada

2.55 Recommendation. In collaboration with Global Affairs Canada, the Canada Border Services Agency should better enforce tariff rate quotas by reviewing the process of verifying permits. It should also explore automated means to validate accounting declarations for quota-controlled goods to be charged customs duties at a lower rate.

The Agency’s response. Agreed. The Canada Border Services Agency will conduct a review of the permit verification process to identify any gaps and challenges, and explore automated means to validate accounting declarations of goods under “within access tariff items.”

The Department’s response. Agreed. Global Affairs Canada will work with the Canada Border Services Agency to identify potential mechanisms to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of the enforcement of tariff rate quotas. The actions associated with this recommendation will be completed by September 2017.

The control framework of the Duties Relief Program was ineffective, allowing some supply-managed goods to be diverted into the Canadian market without the applicable duties being paid

Supply-managed goods—Dairy, chicken, turkey, and specific types of eggs. Supply management is the production and marketing system under which these goods are produced in Canada. The principle behind supply management is to ensure domestic demand is met while ensuring revenues for producers and stable prices for consumers. The system is based on three pillars: production controls, import controls, and price controls.

2.56 We found that the Canada Border Services Agency had few controls to ensure that goods imported duty-free under the Duties Relief Program were, if not subsequently exported, reported to the Agency and that applicable duties were paid within 90 days of the date of diversion into the Canadian market, as required by the program. In 2016, the Agency completed six compliance verifications of Duties Relief Program participants that import supply-managed goods and suspended the licences of all six participants because they did not comply with these program requirements.

2.57 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topic:

2.58 This finding matters because if an importer diverts imported goods into the Canadian market that are intended for subsequent export and for which customs duties are not paid, then Canadian producers might face unfair competition.

2.59 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 2.63.

2.60 What we examined. We examined whether the Canada Border Services Agency ensured that the goods imported under the Duties Relief Program were subsequently exported and not diverted into the Canadian market.

2.61 Management of the Duties Relief Program. The Agency ensured that importers were complying with their licences under the Duties Relief Program by conducting periodic verifications at the importers’ premises. However, we found that the Agency did not use some controls—such as requiring a financial deposit to participate in the program and having renewable licences for importers—to create more incentives for the importers to comply with rules.

2.62 In 2016, the Agency decided to conduct compliance verifications of supply-managed goods imported under the program. We found that the Agency had completed six Duties Relief Program verifications for supply-managed goods by the end of our audit period. All six resulted in the Agency’s suspension of the importers’ licences because they had, rather than exporting the imported goods, diverted them into the Canadian market without reporting the diversion to the Agency and paying the applicable duties within 90 days of the date of diversion.

2.63 Recommendation. In consultation with the Department of Finance Canada, the Canada Border Services Agency should improve the Duties Relief Program’s compliance by considering

- making licences renewable, conditional on an importer’s compliance record; and

- requiring a financial deposit proportionate to the value of duties at risk.

The Agency’s response. Agreed. The Canada Border Services Agency will, in relation to making licences renewable and requiring a financial deposit, consult with the policyholder of the Duties Relief Program, the Department of Finance Canada, in considering these potential improvements to compliance. This will be completed by October 2018, dependent upon the outcome of program consultations led by Global Affairs Canada and the Department of Finance Canada.

Reviewing and analyzing the customs duties regime

Overall message

2.64 Overall, we found that the Department of Finance Canada reviewed the Customs Tariff only for specific purposes. For example, it reviewed tariff items when negotiating trade agreements. We found that the Department also considered the budget and economic implications of changes to the customs duties. We also found that many tariff items generated little revenue. In our opinion, the Department needs to review all tariff items regularly to make sure they still serve the interests of Canadian consumers and businesses.

2.65 These findings matter because the customs duties system affects the Canadian economy and should be periodically reviewed to ensure it continues to best serve the interests of Canadians and protect industries.

2.66 The Department of Finance Canada refused to provide us with the documents that might have contained the analysis on the Canada Border Services Agency’s administrative costs for the $20 minimum threshold for charging customs duties on postal and courier imports.

2.67 In 2013, the Standing Senate Committee on National Finance tabled a report that recommended that the Government of Canada conduct a comprehensive review of Canadian tariffs, keeping in mind the impact on domestic manufacturing, with the objective of reducing the price discrepancies between Canada and the United States for certain products. The report also recommended that the Government of Canada analyze the costs and benefits of increasing the minimum value of shipments that are assessed for customs duties in order to reduce the price differences between Canada and the United States for certain goods.

The Department of Finance Canada reviewed the Customs Tariff only for specific purposes

2.68 We found that the Department of Finance Canada reviewed the Customs Tariff for certain purposes, including negotiation of trade agreements, consideration of budget implications of customs duties, and other government objectives. However, the Department did not ensure that all tariff items were still needed.

2.69 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

2.70 This finding matters because the Canadian economy constantly evolves, so it is important that tariffs remain relevant.

2.71 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 2.74.

2.72 What we examined. We examined whether the Department of Finance Canada performed a regular review of the Customs Tariff, using sound analyses.

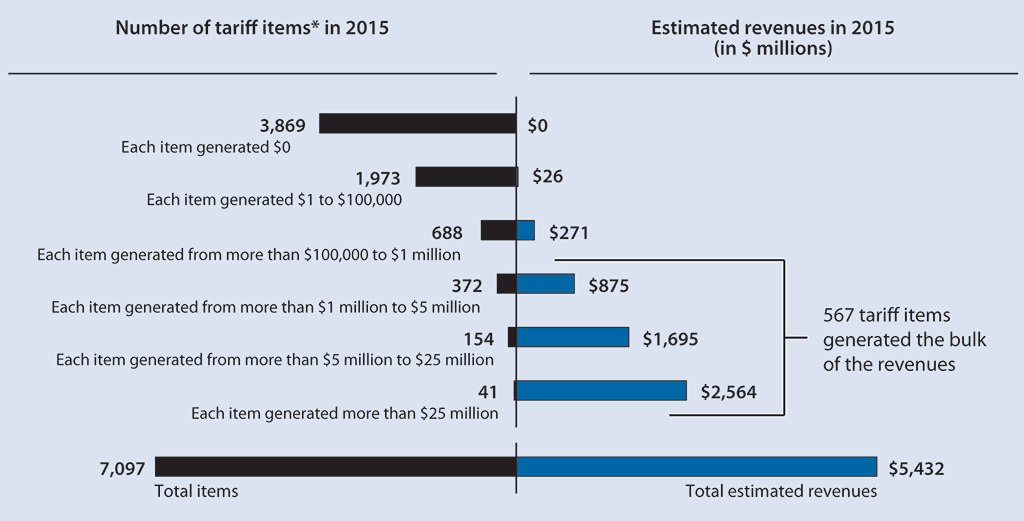

2.73 Reviews of the Customs Tariff. We found that the Department of Finance Canada reviewed the Customs Tariff during recent trade negotiations and in support of various other government priorities. Although the Department made changes to the Customs Tariff, we noted that in 2015, 567 tariff items generated the bulk of customs duty revenues. Each of these 567 tariff items generated more than $1 million (Exhibit 2.3). We also observed that 1,973 tariff items generated less than one half of one percent of customs duty revenues that same year ($26 million out of $5.4 billion). Furthermore, we found that 57 percent of customs duty revenues were generated by just three categories of consumer goods: apparel, footwear, and vehicles and auto parts. In our opinion, a regular review of the Customs Tariff would be useful—for example, to assess whether all tariff items protect manufacturers.

Exhibit 2.3—A small number of tariff items generated most of the customs duty revenues in 2015

Notes: In 2015, transactions were recorded for 7,097 tariff items. The Customs Tariff contains a total of 7,403 tariff items.

*Based on 8 digits in the tariff classification system. Importers classify items according to the World Customs Organization’s Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding System.

Source: Based on data from Statistics Canada, 2015 (calendar year)

Exhibit 2.3—text version

This chart shows the estimated revenues that were generated from the 7,097 tariff items imported in 2015. The tariff items are grouped according to how much revenue individual items generated. Most of the revenues came from the 567 items that each generated more than $1 million.

| Amount generated per item | Number of tariff items | Estimated revenues in $ millions |

|---|---|---|

| $0 | 3,869 | $0 |

| From $1 to $100,000 | 1,973 | $26 |

| From more than $100,000 to $1 million | 688 | $271 |

| From more than $1 million to $5 million | 372 | $875 |

| From more than $5 million to $25 million | 154 | $1,695 |

| More than $25 million | 41 | $2,564 |

| Total | 7,097 | $5,432 |

Notes: In 2015, transactions were recorded for 7,097 tariff items. The Customs Tariff contains a total of 7,403 tariff items.

Identification of tariff items is based on eight digits from the tariff classification system. Importers classify items according to the World Customs Organization’s Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding System.

Source: Based on data from Statistics Canada, 2015 (calendar year)

2.74 Recommendation. The Department of Finance Canada should review the Customs Tariff to identify specific tariff items that no longer meet their policy objectives and that could possibly be modified.

The Department’s response. Agreed. In recent years, the Department of Finance Canada has had a proactive tariff policy in support of important economic policy objectives. This includes numerous measures to assist various economic sectors (including industrial manufacturing, agri-food processors, and transportation), support consumers, and ensure tariff programs for developing countries are aligned with global realities. These efforts are in addition to the many changes made to the Customs Tariff as a result of trade agreements and to simplify its structure and administration.

The Department of Finance Canada agrees that it will continue with its proactive approach to tariff policy in support of various government priorities. In doing so, it will review tariff items that could be modified, taking into account, among other things, Canada’s tariff policy objectives and international obligations.

2.75 Consumer goods tariff relief. As part of the Economic Action Plan 2013, the government decided to eliminate customs duties on baby clothing and selected sports and athletic equipment. Altogether, the Department of Finance Canada estimated that this would reduce government revenue by $76 million. We found that as part of this decision, the Department had appropriately analyzed the fiscal and consumer price impacts of different reductions of customs duties on consumer goods.

2.76 General Preferential Tariff. The General Preferential Tariff offers tariff rates that are lower than the most-favoured-nation tariff rates on goods imported from developing countries. These items are identified in the Schedule to the Customs Tariff. In 2013, the government decided to change the countries covered by the General Preferential Tariff because some more advanced developing countries had become more competitive in international trade and had improved their income levels. On 1 January 2015, the government removed 72 countries from the General Preferential Tariff list, including China and India. The Department of Finance Canada estimated that these changes would result in $333 million in additional customs duties in the 2015–16 fiscal year.

2.77 We found that the Department did a complete analysis of the fiscal and economic impacts of the changes to the General Preferential Tariff. For example, it analyzed different scenarios of changes to the General Preferential Tariff country list and estimated the impact of the changes on the gross domestic product, prices, exports, and imports, as well as the impact on different sectors of the Canadian economy.

Supply chain—The network between a company and its suppliers to produce and distribute a specific product, and the steps it takes to get the product or service to the customer.

2.78 The Department also consulted with stakeholders, including manufacturers and industry associations. Most stakeholders were concerned about the changes proposed to the General Preferential Tariff regime. The Department responded to some of these concerns by postponing the implementation of the changes by six months. This allowed more time for businesses to adjust their supply chains.

The Department of Finance Canada analyzed the $20 minimum threshold for postal and courier imports

2.79 We found that the Department of Finance Canada analyzed the minimum dollar amount for postal and courier imports on which customs duties were charged (de minimis), but we could not conclude whether the analysis was complete. The Department refused to provide us with the documents that might have contained the analysis on the Canada Border Services Agency’s administrative costs for the $20 minimum threshold for charging customs duties on postal and courier imports. According to the Agency’s estimate, there is no net revenue to the government from charging duties on postal shipments with a value of less than $200.

2.80 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topic:

2.81 This finding matters because our audit reports provide Parliament with information on government programs and activities. Without complete information from the Department, we cannot provide assurance that decision makers receive the information they need to make effective decisions.

2.82 We made no recommendations in this area of examination.

2.83 What we examined. We examined whether the Department of Finance Canada reviewed the minimum threshold for assessing customs duties on goods imported through the postal services or by courier to ensure they were still relevant.

2.84 Department of Finance Canada’s analysis. In 1992, the Government of Canada decided that Canadians did not need to pay taxes or duties on goods valued at $20 or less that were imported through the postal service or by courier. By comparison, some of Canada’s peer countries allow higher-value goods to enter their countries before being assessed for customs duties. We found that the Canada Border Services Agency determined that for many low-value imports, it cost more to collect the customs duties than the amount of duties collected. The Agency determined in 2008 that the Government of Canada lost money on goods assessed at less than $100; therefore, it cost the Agency more to administer the current minimum threshold of $20. More recently, the Agency determined that administering customs duties on any goods imported through the postal service valued at less than $200 resulted in a net cost to the Canadian government. Furthermore, because the number of imported parcels has increased significantly—from 38 million in 2011 to 69 million in 2015—the Agency may not be able to consistently enforce the payment of duties on postal shipments with a value between $20 and $200.

2.85 We asked the Department of Finance Canada for its analyses supporting the minimum threshold. The Department provided us with information containing an estimate that increasing the minimum threshold to $200 would have cost the federal government $66 million in forgone revenue in 2011 (revenue that the government will not receive). The Department also considered the minimum threshold level of other countries and the impact on fairness in the Canadian retail sector. The Department of Finance Canada informed us that in its analyses, it also considered the Canada Border Services Agency’s administrative costs for collecting revenues and its enforcement capacity. However, the Department refused to provide us with the documents that contained those particular analyses. The Department considered those documents to be Cabinet confidences that it could not provide on the basis of the government’s interpretation of our statutory right to information and explanations. Therefore, we could not conclude whether the Department had considered the administrative costs of the $20 minimum threshold for charging customs duties on postal and courier imports.

Conclusion

2.86 We concluded that the Canada Border Services Agency could not ensure that all customs duties owed to the government were assessed. We also concluded that Global Affairs Canada and the Canada Border Services Agency could not ensure that the tariff rate quotas were respected. The Canada Border Services Agency allowed some supply-managed goods to enter the Canadian market without the proper duties being paid.

2.87 Furthermore, we concluded that the Department of Finance Canada suitably fulfilled its responsibilities in regard to customs duties, but needed to further review the relevance of tariff items to ensure that they met government objectives. Finally, we could not conclude on whether the Department of Finance Canada considered the administrative costs when it reviewed the $20 minimum threshold for charging customs duties on postal and courier imports.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on the management of customs duties. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs, and to conclude on whether the management of customs duties complies in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office applies Canadian Standard on Quality Control 1 and, accordingly, maintains a comprehensive system of quality control, including documented policies and procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we have complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the Rules of Professional Conduct of Chartered Professional Accountants of Ontario and the Code of Values, Ethics and Professional Conduct of the Office of the Auditor General of Canada. Both the Rules of Professional Conduct and the Code are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit;

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit;

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided; and

- confirmation that the findings in this report are factually based.

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether the Department of Finance Canada, Global Affairs Canada, and the Canada Border Services Agency adequately managed the customs duties according to their roles and responsibilities.

In this context, “adequately managed” means

- performed regular reviews of the Customs Tariff, using sound analyses;

- ensured the correct assessment of customs duties owed to the Crown;

- provided support to commercial importers to enable compliance with importing requirements;

- ensured that the tariff rate quotas were respected; and

- ensured that the goods imported under the Duties Relief Program were not unlawfully diverted into the Canadian economy.

Scope and approach

The audit on the management of the customs duties included the Department of Finance Canada, Global Affairs Canada, and the Canada Border Services Agency.

The audit was conducted along two lines of enquiry:

- The first line of enquiry examined how the Department of Finance Canada kept the Customs Tariff relevant by performing periodic reviews and using sound analysis. The audit also examined whether the Department reviewed the appropriateness of the $20 de minimis rule for postal and courier imports.

- The second line of enquiry examined whether Global Affairs Canada and the Canada Border Services Agency ensured that tariff rate quotas were respected and whether the Agency ensured correct assessment of customs duties owed to the federal government. The audit examined whether the Agency enabled businesses to comply with trade rules and regulations and whether it ensured that goods imported under the Duties Relief Program were not unlawfully diverted into the Canadian economy.

The scope of the audit did not include the security and the safety of imported goods to Canada, free trade agreements, exports, and the supply management program.

Criteria

To determine whether the Department of Finance Canada, Global Affairs Canada, and the Canada Border Services Agency adequately managed the customs duties according to their roles and responsibilities, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

The Department of Finance Canada performs periodic reviews of the Customs Tariff, using sound analysis. “Sound analysis” means assessing the impacts on the Canadian economy, on consumers, and on businesses, and assessing the administrative and compliance burden. |

|

|

The Canada Border Services Agency ensures the correct assessment of customs duties owed to the Crown from commercial importers. |

|

|

The Canada Border Services Agency provides support to commercial importers to enable compliance with importing requirements. |

|

|

Global Affairs Canada and the Canada Border Services Agency ensure that tariff rate quotas are respected. |

|

|

The Canada Border Services Agency ensures that the goods imported under the Duties Relief Program are not unlawfully diverted into the Canadian economy. |

|

|

The Department of Finance Canada reviews the Postal Imports Remission Order and the Courier Imports Remission Order to ensure that they are still relevant. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period between 1 January 2013 and 31 May 2016. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies. However, to gain a more complete understanding of the subject matter of the audit, we also examined certain matters that preceded the starting date of the audit.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 3 March 2017, in Ottawa, Ontario.

Audit team

Principal: Richard Domingue

Director: Philippe Le Goff

Alexandre Fortier-Labonté

Rose Pelletier

List of Recommendations

The following table lists the recommendations and responses found in this report. The paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report, and the numbers in parentheses indicate the location of the related discussion.

Assessing customs duties

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

2.32 The Canada Border Services Agency should review its customs brokers licensing regime by considering features such as

|

The Agency’s response. Agreed. The Canada Border Services Agency will conduct a review of the customs broker licensing regime. While the Customs Act defines liability for compliance with the import process and for the payment of duties and taxes, the Agency acknowledges that there are opportunities to review this regime in order to ensure that it enables the Agency to effectively manage duties and taxes. In recent years, the Agency has conducted reviews of its broker licensing regime as part of both internal evaluations as well as external consultations. The Agency continues to further review this regime as part of its Commercial Transformation Initiative and in the development of the CBSA Assessment and Revenue Management (CARM) project solution. These actions will be completed by September 2018. |

|

2.35 The Canada Border Services Agency should review its penalties in order to better protect import revenues and ensure compliance with trade programs. (2.33–2.34) |

The Agency’s response. Agreed. The Canada Border Services Agency’s Programs Branch will explore further measures aimed at creating a meaningful deterrent to importer non-compliance related to the evasion of import revenues and ensuring compliance with trade programs. This will be completed by June 2018. |

|

2.41 Unless otherwise specified in a free trade agreement, the Canada Border Services Agency should review the period allowed for retroactive changes on the import form, without compromising the Agency’s ability to conduct compliance verifications. (2.36–2.40) |

The Agency’s response. Agreed. In consultation with its legal services, the Canada Border Services Agency will conduct a review of the current framework that allows for retroactive changes on the import form. The Agency will develop options to reduce the period allowed for the importer to make corrections while preserving the Agency’s ability to conduct compliance activities. These actions will be completed by December 2019. |

Controlling goods

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

2.55 In collaboration with Global Affairs Canada, the Canada Border Services Agency should better enforce tariff rate quotas by reviewing the process of verifying permits. It should also explore automated means to validate accounting declarations for quota-controlled goods to be charged customs duties at a lower rate. (2.53–2.54) |

The Agency’s response. Agreed. The Canada Border Services Agency will conduct a review of the permit verification process to identify any gaps and challenges, and explore automated means to validate accounting declarations of goods under “within access tariff items.” The Department’s response. Agreed. Global Affairs Canada will work with the Canada Border Services Agency to identify potential mechanisms to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of the enforcement of tariff rate quotas. The actions associated with this recommendation will be completed by September 2017. |

|

2.63 In consultation with the Department of Finance Canada, the Canada Border Services Agency should improve the Duties Relief Program’s compliance by considering

|

The Agency’s response. Agreed. The Canada Border Services Agency will, in relation to making licences renewable and requiring a financial deposit, consult with the policyholder of the Duties Relief Program, the Department of Finance Canada, in considering these potential improvements to compliance. This will be completed by October 2018, dependent upon the outcome of program consultations led by Global Affairs Canada and the Department of Finance Canada. |

Reviewing and analyzing the customs duties regime

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

2.74 The Department of Finance Canada should review the Customs Tariff to identify specific tariff items that no longer meet their policy objectives and that could possibly be modified. (2.73) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. In recent years, the Department of Finance Canada has had a proactive tariff policy in support of important economic policy objectives. This includes numerous measures to assist various economic sectors (including industrial manufacturing, agri-food processors, and transportation), support consumers, and ensure tariff programs for developing countries are aligned with global realities. These efforts are in addition to the many changes made to the Customs Tariff as a result of trade agreements and to simplify its structure and administration. The Department of Finance Canada agrees that it will continue with its proactive approach to tariff policy in support of various government priorities. In doing so, it will review tariff items that could be modified, taking into account, among other things, Canada’s tariff policy objectives and international obligations. |