Commentary on the 2016–2017 Financial Audits Commentary on the 2016–2017 Financial Audits

Commentary on the 2016–2017 Financial Audits

Background to the Commentaries on Financial Audits

Table of Contents

- Roadmap to this report

- Results of the 2016–2017 financial audits

- Understanding financial information

- Understanding financial health goes beyond numbers in the financial statements

- Contingent liabilities and contractual obligations are significant and complex

- Finding financial information about income security programs and their long-term sustainability isn’t straightforward

- Decisions about infrastructure and other major capital assets affect the government’s financial position

- The government’s financial statements discussions and analysis has improved, but its usefulness can still be enhanced

- About our financial statement audits

Roadmap to this report

This report isn’t an audit report. Instead, it highlights the results of the link to Financial Audit Glossaryfinancial audits conducted by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada in federal organizations for fiscal years ended between December 2016 and August 2017 (the 2016–2017 financial audits), and it provides a commentary stemming from this work.

The Office audited the financial statements of 68 federal organizations. It concluded that 67 of them met the requirements for clarity, completeness and accuracy that federal organizations are subject to. It could not issue an audit opinion on the financial statements of National Defence’s Reserve Force Pension Plan because of significant and persistent problems with data quality.

Despite challenges with auditing pay expenses, the Office was able to provide the Government of Canada with an link to Financial Audit Glossaryunmodified audit opinion on its consolidated financial statements for the 19th consecutive year.

This report provides an overview of observations brought to management’s attention during the 2016–2017 financial audits and touches on persistent problems in the financial statements of the Reserve Force Pension Plan.

It also explores three areas covered by the government’s link to Financial Audit Glossaryfinancial statements: contingent liabilities and contractual obligations, income security programs and major capital assets including infrastructure. The report suggests questions that parliamentarians could ask federal organizations to help them assess the impact of these areas on the government’s financial position.

Finally, the same 3 areas are considered in a discussion of changes that the government could make to clarify and enrich its financial statements discussion and analysis, to better inform parliamentarians tasked with overseeing public spending.

Results of the 2016–2017 financial audits

Overall, the Office of the Auditor General of Canada was satisfied with the credibility of 67 of the 68 financial statements prepared by the Government of Canada and the federal organizations that the Office audits.

The one exception was the financial statements of National Defence’s Reserve Force Pension Plan, for which the Office was once again unable to issue an audit opinion because of significant and persistent problems with data quality.

The Office provided the Government of Canada with an unmodified audit opinion on its consolidated financial statements for the 19th consecutive year. The audit was nonetheless time-consuming and laborious due to the significant extra effort needed to audit the government’s employee pay expenses.

The government’s pay transformation initiative, which included launching the new Phoenix pay system, changed many of the government’s pay processes. Due to the deficiencies the Office identified when it reviewed these processes, it determined that it could not rely on existing internal controls to audit pay expenses to the extent that it had in previous years.

As a result, the Office had to change its approach to auditing pay expenses to examine a much larger sample of transactions than in prior years. That change resulted in additional effort and costs for the Office. It spent approximately 10,000 hours more to audit pay expenses incurred in the fiscal year ended March 31, 2017, than in prior years.

The Office will need to continue to spend additional effort to audit pay expenses until the government fixes pay control deficiencies and the Office can rely on the government’s internal controls to complete its audit work.

The Reserve Force Pension Plan was introduced by National Defence in 2007 to provide pensions to reservists in the Canadian Armed Forces. The Office was appointed as the plan’s auditor in 2008.

In the 10 years since the Reserve Force Pension Plan was introduced, the Office has been unable to conclude on the accuracy and completeness of the data used to estimate key elements of the financial statements. This means that the Office has been unable to provide parliamentarians and plan members with assurance that the plan’s financial statements are free of significant error. Given the severity of the matter, the Office undertook a performance audit of the Reserve Force Pension Plan, which it reported in spring 2011.

Although National Defence changed some of its record keeping for reservists, these improvements have not resolved the matter. For the fiscal year ended March 31, 2017, the Office was still unable to conclude on the accuracy and completeness of the data used to estimate reported pension obligations of $610 million. As a result, the Office once again could not issue an opinion about the plan’s financial statements.

National Defence needs to complete its ongoing efforts to resolve this matter. This situation leaves parliamentarians and plan members without assurance that the plan’s financial statements present credible information about the plan’s finances, which is unacceptable.

For some of the financial audits it conducts, the Office is required by law to report whether organizations are complying with the relevant laws, regulations, directives or bylaws. We may also raise any other matters to the attention of government or federal organizations we audit, at our discretion.

When the Office was required by law to report on compliance during the 2016–2017 financial audits, the Office was satisfied that on the basis of its examination of the transactions that came to its attention, there was no instance of non-compliance with laws, regulations, directives or bylaws that caused the Office to modify its audit opinions.

During this type of examination, auditors can identify opportunities to improve the policies and the systems and practices that government organizations have in place to comply with laws, regulations, directives and bylaws. Auditors typically communicate these observations to organizations to help them make improvements or fix the problems.

The Office was satisfied that the reports of the government and the federal organizations, which included the financial statements the Office audited as part of the 2016–2017 financial audits, met the reporting deadlines set in legislation.

Timeliness is important because decision makers need to receive financial information at the right time to consider that information when making decisions about an organization’s priorities. Similarly, elected officials need to receive relevant information at the right time to exercise oversight over government operations.

Delays in financial reporting are rare. When they occur, they are usually due to external or other circumstances over which the organization has little control. In addition, delays are typically resolved within a few months.

For the Government of Canada and its many departments and organizations, the deadlines for preparing and issuing audited annual financial statements are set in legislation. These annual deadlines typically range from 90 to 120 days following the end of an organization’s fiscal year. In the case of federal pension plans, the legislative deadlines extend to 12 months.

During our financial audits, we can identify opportunities for government organizations to change their procedures to improve systems of internal control, streamline operations or enhance financial reporting practices.

Observations arise from the work we do to support our audit opinion on the reasonable accuracy of the financial statements of the government and of certain federal organizations. As such, the absence of observations for any given organization or area does not mean that the organization’s operations or practices are flawless and that there is no room for improvements. It only means that nothing of note came out of those elements we examined when conducting our financial audits.

Each year, our observations vary in number and in significance. Some are suggestions meant to improve efficiency. Others raise more serious issues, such as inadequate or ineffective internal controls that expose organizations to the risk of the mishandling of funds or the risk of errors in financial reports.

We bring these observations to management’s attention in a management letter or in the Auditor General’s observations on the link to Financial Audit GlossaryPublic Accounts of Canada. It is management’s responsibility to address these observations.

The Auditor General noted the following 3 matters in his observations on the government’s consolidated financial statements in the 2017 Public Accounts of Canada:

- transformation of pay administration

- the National Defence inventory

- selecting discount rates

As part of our financial audits, we follow up every year on previous years’ observations to monitor management’s progress in addressing the issues we noted.

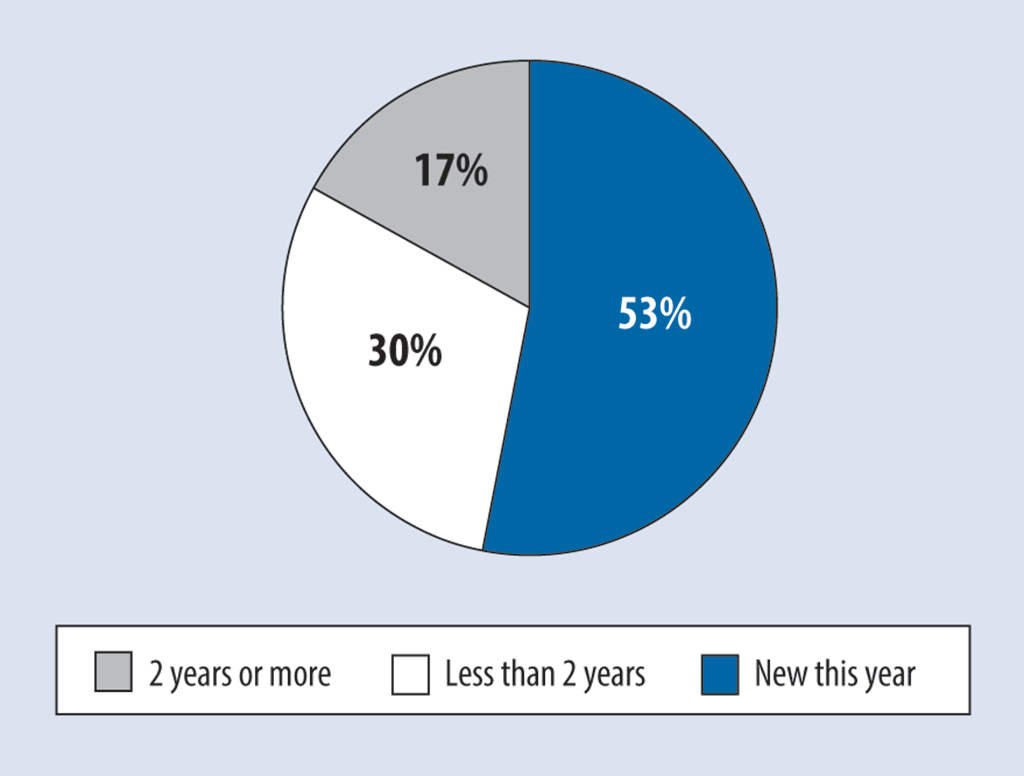

Every year, we issue hundreds of observations to many federal organizations. Of the total observations that were unresolved at the time we completed individual 2016–2017 financial audits, 83% were either newly issued (53%) or had been unresolved for less than 2 years (30%) (see Exhibit 1). This is positive. It means that in most cases, organizations resolved our observations on a timely basis.

Exhibit 1—Unresolved observations in the 2016–17 fiscal year

Exhibit 1—text version

This chart shows that by the end of the 2016–2017 financial audits, 53% of unresolved observations were new, 30% were under two years old, and 17% were two years or older.

Of the total observations unresolved by the end of the 2016–2017 financial audits, more than half resulted from our review of information technology systems and the controls in place to ensure the integrity of the data these systems process. And of these observations on information technology systems, over 70% concerned the management of access granted to system users. These issues should be corrected to help ensure the integrity of the government’s financial data.

The remaining observations mainly concerned improvements in financial reporting processes and compliance with government policies, laws and regulations.

Understanding financial information

Understanding financial health goes beyond numbers in the financial statements

Financial statements summarize a federal organization’s financial health and annual performance. Among other things, the statements show the annual surplus or deficit compared with the budget, as well as the organization’s assets, reflecting what it owns, and its liabilities, reflecting what it owes.

Although these numbers are often the focus of a financial statement reader’s attention, they aren’t enough on their own to assess the state of government finances. A reader also needs to be aware of the risks and uncertainties associated with the government’s assets and liabilities.

One place a reader can look to find more information on these risks and uncertainties is the link to Financial Audit Glossaryfinancial statements discussion and analysis (FSDA). The FSDA is a section of the Public Accounts of Canada that helps explain the numbers in the financial statements. The FSDA is intended to provide some context and explanation about the risks and uncertainties in the overall financial picture provided by the financial statements, to help readers understand the impact that past government decisions could have on future public finances.

Contingent liabilities, large income security programs and infrastructure are examples of areas covered in financial statements where there are risks and uncertainties. We chose to highlight them in this report to assist parliamentarians in their oversight of government finances and to suggest changes that the government could make to enhance its FSDA.

Contingent liabilities and contractual obligations are significant and complex

Contingent liabilities are different from known liabilities. They are possible expenditures that the government may or may not make in the future. Determining whether a future expenditure will occur is dependent on uncertain events not entirely within the government’s control, such as a future settlement of an existing lawsuit.

These possible expenditures are reflected differently in the financial statements, depending on the likelihood that they will eventually become due.

Provisions for contingent liabilities are amounts recorded in the financial statements because they are likely to occur, meaning they are highly probable, and their amount can be estimated.

Contingent liabilities other than provisions for contingent liabilities are possible obligations that aren’t recorded in the financial statements, because there is a low or undeterminable probability that they will result in future cash outflows.

Regardless of whether possible obligations have a higher or lower probability of resulting in an expenditure, they have the potential to substantially alter a government’s future financial position. That is why it is important, in the oversight of public finances, to consider the nature of these amounts, their size and their risk of potential financial impact, as well as how the government is prepared to deal with those risks if they materialize.

Contingent liabilities are outlined in note 6 to the government’s financial statements and in supporting tables found in the Public Accounts of Canada. Reading through these numbers, it is difficult to understand which amounts reflect expenditures likely to occur—meaning they are highly probable and therefore are recorded in the financial statements—and which amounts are unlikely to result in an expenditure and are therefore not recorded in the financial statements. Exhibit 2 shows where readers can find information on contingent liabilities.

Exhibit 2—Where to find information on contingent liabilities

Exhibit 2—text version

Information on contingent liabilities is found in Volume I of the 2017 Public Accounts of Canada. Section 2 contains the consolidated financial statements of the Government of Canada as of March 31, 2017, which are audited by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada. The statement of financial position shows liabilities, including a provision for contingent liabilities of $16.5 billion, plus assets and the accumulated deficit. The contingent liabilities recorded in the statement of financial position are all considered likely.

Note 6 to the consolidated financial statements shows an amount of $2.3 trillion. This amount consists of $0.3 trillion in guarantees and claims, including the $16.5 billion provision for contingent liabilities, plus $2.0 trillion in insurance programs and guarantees. Sections 9 and 11 contain tables 9.7, 11.5 and 11.6, which show the $0.3 trillion in guarantees and claims. Section 11 contains tables 11.5 and 11.7, which show the $0.3 trillion in guarantees and claims, and the $2.0 trillion in insurance programs and guarantees. These contingent liabilities are all considered unlikely or not determinable.

The government’s contingent liabilities are very large: they were estimated at $2.3 trillion as at March 31, 2017. But only a small amount—$16.5 billion—was considered likely to occur and was therefore recorded as a provision for contingent liabilities in the 2017 financial statements.

In the 2017 financial statements, the provision for contingent liabilities were reported in a separate line item for the first time ($16.5 billion as at March 31, 2017). The separate presentation is useful to highlight the impact of contingent liabilities on the government’s financial position. We were able to calculate the breakdown of the $16.5 billion provision, as shown in Exhibit 3. This breakdown would be useful information to include in the note to the financial statements.

Exhibit 3—Provision for contingent liabilities in the federal government’s financial statements

| Fiscal year ended March 31 | ||

|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2016 | |

| Guarantees provided by the government | $0.3 | $0.3 |

| First Nations treaty-related claims | 10.6 | 9.7 |

| Other claims and litigations | 5.6 | 2.6 |

| Provision for contingent liabilities | $16.5 | $12.6 |

Of the $2.3 trillion of contingent liabilities described in note 6 to the financial statements, $2.0 trillion were for financial guarantees, mainly provided under federal insurance programs (Exhibit 4).

Exhibit 4—Selected federal insurance programs and guarantees

Exhibit 4—text version

This diagram shows that the Government of Canada had $2.0 trillion in insurance programs and guarantees. This amount consisted of $1.3 trillion in mortgage insurance and guarantees, and $0.7 trillion in deposit insurance. Of the $1.3 trillion in mortgage insurance and guarantees

- the Department of Finance Canada provided $0.3 trillion in guarantees to protect Canadian financial institutions against default by private mortgage insurers, and

- the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation provided $0.5 trillion in mortgage insurance to Canadian financial institutions to protect them against the risk of mortgage default and $0.5 trillion in guarantees to investors to ensure the timely payment of their insured investments.

The Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation provided $0.7 trillion in deposit insurance to depositors to protect their deposits against the risk of bank default.

For example, the government provides guarantees and mortgage insurance to financial institutions to stabilize the financial market for housing and to support access to housing through 2 main programs. The first program, through the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, protects financial institutions against default by homeowners on their loans. The second, through the Department of Finance Canada, protects financial institutions against default by private mortgage insurers.

The government also provides, through the Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation, protection to Canadians who hold eligible deposits of up to $100,000 in Canadian federally regulated financial institutions.

Although the guarantees under these insurance programs totalled $2 trillion as at March 31, 2017, the large majority have a very low probability of resulting in an expenditure. Only a fraction of less than 0.2% was expected to be paid and recorded in the financial statements of the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation and the Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation, the 2 Crown corporations actively managing these insurance programs.

The following are some questions that parliamentarians could ask the government to assess how well it is managing exposures to risks regarding contingent liabilities:

- What factors or risks could contribute to the potential increase of contingent liabilities in the future?

- How is the government keeping an eye on these possible amounts, and how is it monitoring the possibility that they could become real liabilities?

- What is the nature of the items included in the provision for contingent liabilities? What is the reason for the increase (or decrease)?

Contractual obligations are commitments to making future payments under long-term agreements to acquire goods and services, such as construction contracts and leases of office space, or to making payments to Canadians or other levels of government under grant and contribution agreements.

Contractual obligations are different from contingent liabilities because they are amounts that the government is obliged to pay. However, because the services are to be provided to the government in the future, contract payments aren’t yet recorded as liabilities in the financial statements. Instead, contractual obligations are outlined in note 18 of the government’s financial statements to show the amounts the government has committed to spend in the future.

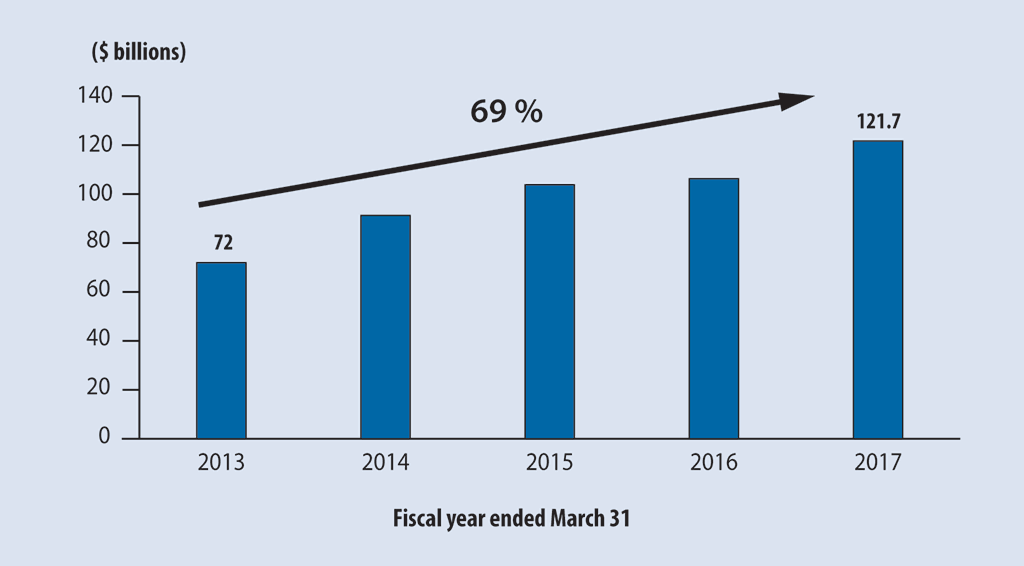

Contractual obligations were nearly $122 billion as at March 31, 2017. The government expected that it would pay 84% of this amount within the next 5 years. This amount has increased by 69% in the past 4 years, as illustrated in Exhibit 5.

Exhibit 5—Government of Canada’s contractual obligations

Exhibit 5—text version

This chart shows that the Government of Canada’s contractual obligations rose 69% from $72.0 billion in the fiscal year ended March 31, 2013 to $121.7 billion in the fiscal year ended March 31, 2017.

The following lists the amounts of the Government of Canada’s contractual obligations for each fiscal year from 2013 to 2017:

- $72.0 billion in the fiscal year ended March 31, 2013

- $91.3 billion in the fiscal year ended March 31, 2014

- $103.8 billion in the fiscal year ended March 31, 2015

- $106.3 billion in the fiscal year ended March 31, 2016

- $121.7 billion in the fiscal year ended March 31, 2017

It is likely that this amount will continue to grow in the future, as the government has indicated that it plans to spend more on long-term infrastructure projects in coming years. This makes it important that this amount be considered by parliamentarians in their oversight role.

The following are some questions that parliamentarians could ask the government about contractual obligations:

- Why have contractual obligations steadily been growing over recent years?

- What will be the impact of these obligations on future financial statements?

Finding financial information about income security programs and their long-term sustainability isn’t straightforward

The government provides income security to Canadians through mainly 3 programs: Old Age Security (OAS), Employment Insurance (EI) and the Canada Pension Plan (CPP).

These programs are complex. Each is set up differently, which is why they are reflected differently in the Public Accounts of Canada.

As the population ages, questions arise about the long-term sustainability of these programs and the impact their costs will have on public finances and on Canadians.

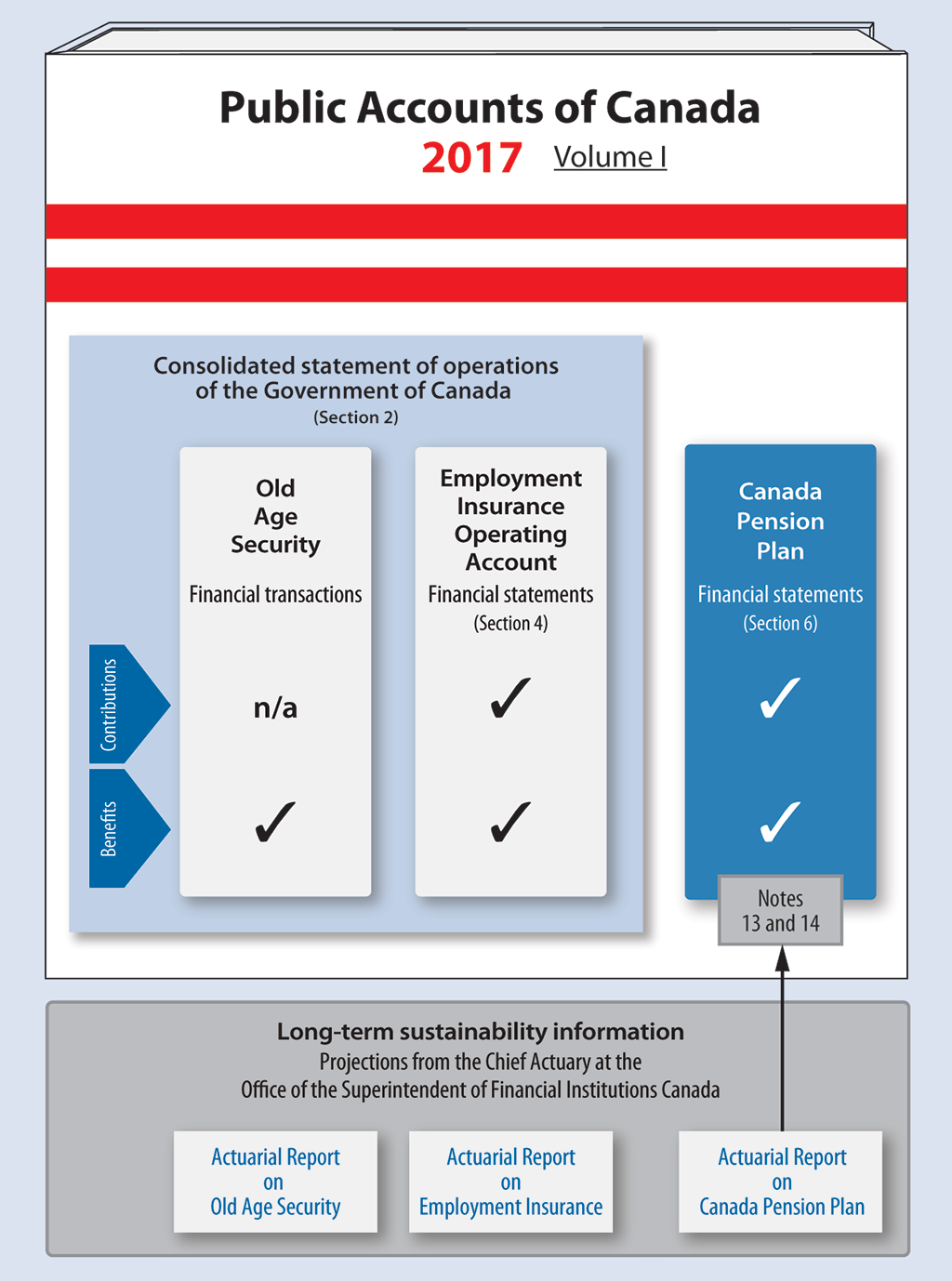

Financial statements mainly report historical transactions and are usually not enough to show what might happen to these programs in the future. To understand the long-term sustainability of income security programs, readers must look to other reports that make projections into the future, such as those issued by the Chief Actuary at the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. Exhibit 6 shows where to find financial information about these programs.

Exhibit 6—Where to find financial information on Canadian income security programs

Exhibit 6—text version

This diagram shows that financial information on Canadian income security programs can be found in the Public Accounts of Canada and in projections from the Chief Actuary at the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada.

The 2017 Public Accounts of Canada, Volume I, contain the consolidated statement of operations of the Government of Canada, which is in Section 2. That statement contains information on Old Age Security’s financial transactions, which include benefits but no contributions. The statement also contains information on the Employment Insurance Operating Account, whose financial statements are in Section 4. Those financial statements show contributions and benefits. The consolidated statement of operations of the Government of Canada found in Section 2 does not contain information about the Canada Pension Plan. The financial statements of the Canada Pension Plan are found in Section 6, which include contributions and benefits.

Information on the long-term sustainability of these three programs are found in projections from the Chief Actuary at the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada in the Actuarial Report on Old Age Security, the Actuarial Report on Employment Insurance, and the Actuarial Report on the Canada Pension Plan. The Actuarial Report on the Canada Pension Plan is also mentioned in Notes 13 and 14 of the Canada Pension Plan financial statements in Section 6 of Volume I of the 2017 Public Accounts of Canada.

OAS is the government’s largest pension program. It cost $48.2 billion in the 2017 fiscal year. Canadians don’t contribute directly to the program, meaning that OAS benefits are funded out of the government’s general revenues and have a direct impact on the annual deficit. The cost of OAS has been increasing on average by 4.7% each year over the last 10 years. The link to a portable document format (PDF) filelatest predictions from the Chief Actuary are that the cost of OAS will continue to grow on average by 5.5% annually until 2030, mainly due to the retirement of the baby boom generation, and thereafter, the growth will slow down to an annual average of 2.9% until 2060. These predictions about the future cost of OAS were reflected in the Department of Finance Canada’s Update of Long-Term Economic and Fiscal Projections published in December 2017. Discussing these trends in the government’s financial statements discussion and analysis would be useful to enable users to assess potential future implications of the cost of OAS on public finances.

The EI program mainly provides temporary income support to eligible unemployed workers. The EI premiums and EI benefits and other costs were nearly $23 billion each for the 2017 fiscal year. Although they are reported as part of the government’s annual revenues and expenses, they are also administered independently through the Employment Insurance Operating Account, which is co-managed by government representatives, workers and employers. The EI Operating Account has its own audited financial statements, which are included in Section 4 of Volume 1 of the Public Accounts of Canada. The EI Operating Account’s long-term sustainability relies on setting EI premiums based on link to a portable document format (PDF) fileprojections by the Chief Actuary. Legislation requires that the account be managed on a break-even basis over a 7-year period. As of March 31, 2017, the EI Operating Account had an accumulated surplus of $3 billion, which was included in the government’s accumulated deficit.

The CPP is jointly controlled by the federal and provincial governments. This is why it isn’t included in the government’s financial statements, unlike the OAS and EI programs. The CPP is funded by contributions from employers and workers, as well as from investment income generated by the plan’s assets. The CPP has its own audited financial statements, which are included in Section 6 of Volume 1 of the Public Accounts of Canada. The 2017 CPP financial statements reported assets available for benefit payments of $321 billion. However, to assess the CPP’s long-term financial sustainability, a reader must also consider projections prepared by the Chief Actuary, which are summarized in notes 13 and 14 of the CPP financial statements. The link to a portable document format (PDF) fileChief Actuary’s 27th triennial actuarial report on the Canada Pension Plan estimated the obligation for pension benefits at $1,171 billion on the basis of plan participants as at December 31, 2015. However, it concluded that the current legislated contribution rate of 9.9% is enough to ensure the plan’s financial sustainability over the long term when considering the impact of both current and future plan participants.

The following are some questions that parliamentarians could ask the government about income security programs:

- What is the financial impact of these income security programs on government finances?

- How does the government monitor the long-term sustainability of these 3 income security programs?

Decisions about infrastructure and other major capital assets affect the government’s financial position

The federal government owns or invests in capital assets worth billions of dollars, including infrastructure such as bridges and buildings.

Understanding the current and future financial impacts of infrastructure or large-scale capital assets requires looking beyond their acquisition or construction costs. Readers must also be aware of the significant costs and financial risks of operating and maintaining these assets throughout their life cycle, and of the obligations to dismantle or otherwise dispose of them at the end of their useful life.

Financial statements provide only part of this story because they reflect only expenses incurred to date. Readers need to consider additional information found in notes to the financial statements or in the financial statements discussion and analysis (FSDA) to assess the future impact of the costs incurred from these assets on the government’s financial position.

For example, billions of dollars in investments are expected over the coming years to build the new Champlain Bridge in Montréal and the Gordie Howe International Bridge between Windsor in Canada and Detroit in the United States. Only the costs incurred to date were included in the government’s 2017 financial statements, as explained in the section of this report on public-private partnerships (P3s).

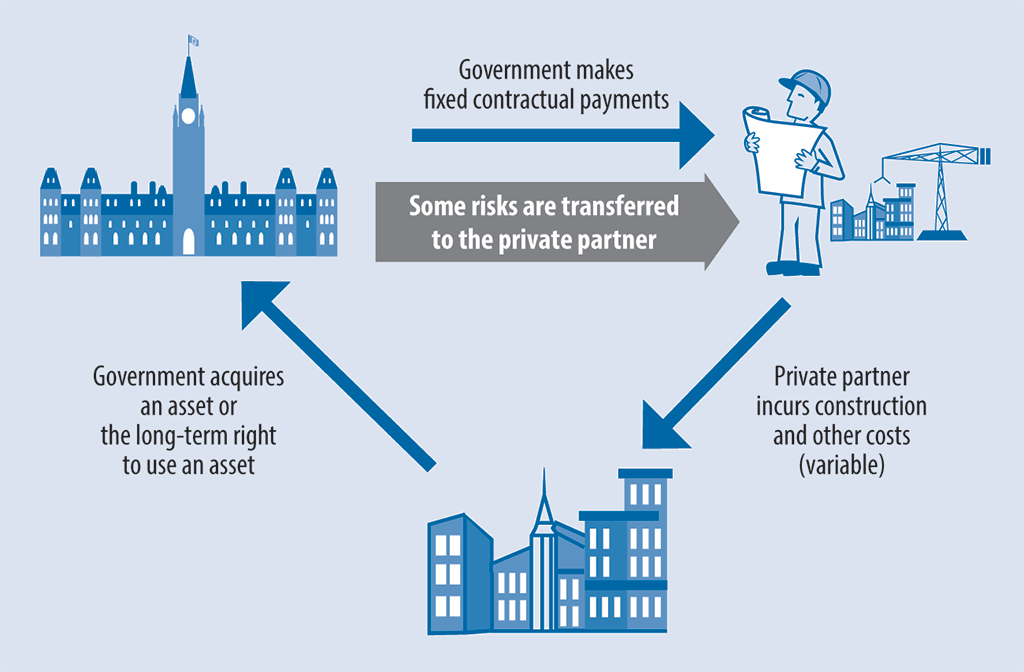

The government is increasingly using public-private partnerships (P3s) to manage infrastructure projects. These arrangements—whereby the government hires a private corporation to undertake aspects of an infrastructure project, such as construction, operation or maintenance—have different financial implications than the traditional approach to building and managing infrastructure projects. Understanding how P3s work is important to assess their present and future impacts on public finances.

The government uses P3s as a form of long-term financing and a way to benefit from private sector expertise. A P3 is also a way to transfer to the private partner some of the risks of the various phases of a project, such as cost overruns, technical defects, delays and rising interest rates during construction.

There is a cost to the government for transferring these types of risks to the private partner, compared with undertaking and self-financing these projects the traditional way. For example, the private partner typically seeks to recover from the government interest charges on amounts it borrowed from private banks at rates that are higher than the preferential borrowing rates available to the government. Cost-benefit analyses and risk assessments are therefore important steps to take before a decision is made to proceed with a P3 project.

P3s can take different forms, with varying degrees of public and private sector involvement. In a simple scenario as illustrated in Exhibit 7, the private corporation incurs and finances the construction costs upfront. Meanwhile, the government commits to reimburse the private partner a fixed amount set out in the terms of the P3 agreement, through a series of payments spread over a longer period, often extending beyond the construction period.

Exhibit 7—Illustration of a public-private partnership

Exhibit 7—text version

First, the federal government makes fixed contractual payments to the private partner and transfers some risks to that partner. Next, the private partner incurs construction and other costs, which are variable. Lastly, the federal government acquires an asset or the long-term right to use an asset.

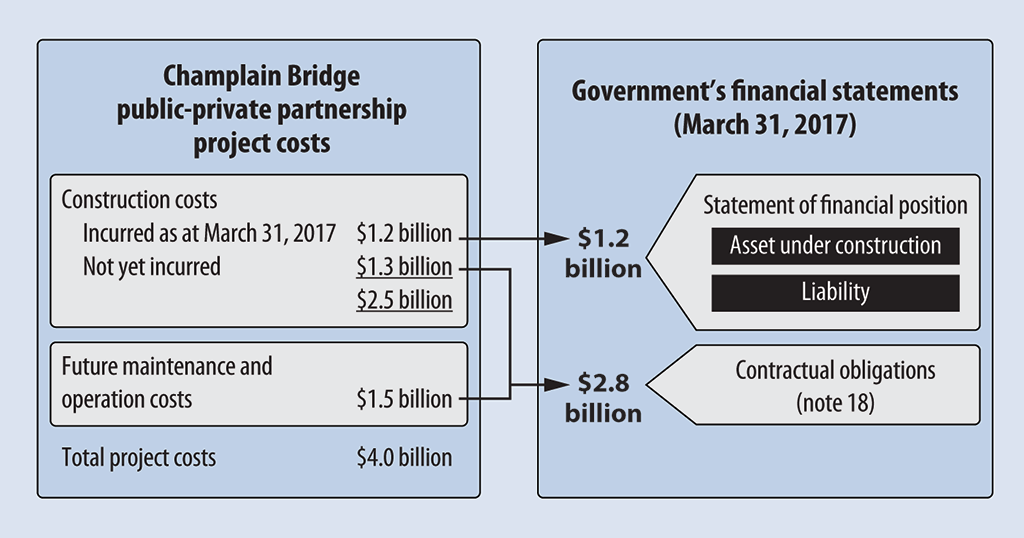

A significant example of a P3 project is the replacement of the existing Champlain Bridge in Montréal led by Infrastructure Canada. Of the total expected cost of $4.0 billion, a liability of $1.2 billion was recorded in the 2017 financial statements, reflecting the value of the work completed by the private partner. The balance of $2.8 billion was included in the government’s contractual obligations and included $1.5 billion for the bridge’s maintenance and operation over the next 30 years (Exhibit 8).

Exhibit 8—How the Champlain Bridge project costs were reflected in the government’s 2017 financial statements

Exhibit 8—text version

The following were the Champlain Bridge public-private partnership project costs. Construction costs incurred as at March 31, 2017 were $1.2 billion and costs not yet incurred were $1.3 billion, for a total of $2.5 billion in construction costs. Future maintenance and operation costs are expected to be $1.5 billion. Total project costs are expected to be $4.0 billion.

The project costs were reflected in the government’s financial statements as at March 31, 2017 in two places. The statement of financial position, or balance sheet, showed an asset under construction and a liability of $1.2 billion. Note 18 showed contractual obligations of $2.8 billion, which was the total of $1.3 billion in construction costs not yet incurred, plus future maintenance and operation costs of $1.5 billion.

Another significant example of a P3 project is the construction of the Gordie Howe International Bridge by the Windsor-Detroit Bridge Authority, also expected to cost billions of dollars. This project is still in its early stages. At the time of our audit of the authority’s 2017 financial statements, the procurement process was still ongoing and the private partner hadn’t yet been chosen. Total costs incurred to date for the bridge were $358 million as at March 31, 2017. These costs mainly consisted of purchasing land and undertaking preparatory activities, such as road construction and utility relocation, to get the site ready for construction by the eventual private partner.

P3 arrangements are used throughout federal organizations. Properly accounting for P3s can be challenging and requires significant judgment. For instance, a department or government organization must estimate and record the asset and the associated liability as the project progresses during construction.

Since 2017, the government maintains a centralized list of active or expected P3 arrangements in various federal departments to help ensure they are properly reflected in the financial statements.

Information on P3s was limited in the 2017 Public Accounts of Canada; there was one footnote in note 16 regarding the total amount spent on P3s in the 2017 fiscal year. Although the government’s financial statements, including its accounting for P3s, comply with accounting standards, Canadians and Parliament could benefit from additional information on significant P3 projects in the FSDA. This information could include the associated financial impact, such as the cost of these projects to the government and the timing of the payment of amounts owed to the private partner.

While new capital assets such as infrastructure are being built, the government must also manage its old assets. There are different strategies to manage old assets, including dismantling, refurbishing or selling them, depending on their nature.

The government has major capital assets that have either reached or will soon reach the end of their useful lives and that will need to be dismantled. Although the government expects it will incur future costs to dismantle these assets, in some cases, it has not yet decided how and when it will be able to do so. These future costs aren’t reported in the financial statements or elsewhere in the FSDA or the Public Accounts of Canada because there isn’t enough information to develop reasonable estimates. These potential future obligations could have a significant impact on the government’s financial health and must therefore be understood.

An example is the decommissioning of the existing Champlain Bridge in Montréal managed by The Jacques-Cartier and Champlain Bridges incorporatedInc., once the new bridge is in service. The government has signalled its intention to dismantle the existing bridge, but it has not yet decided how and when this will take place. As such, the government does not have enough information to develop reliable cost estimates, which is why there are no liability or decommissioning costs recorded yet in the government’s financial statements.

Another example of old capital assets that the government will need to decommission is military equipment that is no longer used by National Defence. The government has not yet decided how and when it will proceed with decommissioning this equipment. As such, there wasn’t enough information as at March 31, 2017, to record the estimated potential decommissioning costs in the government’s 2017 financial statements.

In Budget 2017, the federal government announced a commitment to begin a 3-year review of its capital assets to identify ways to enhance or generate greater value from those assets. We support the government’s review. It could help to identify aging and idle capital assets and the risks that they may generate potential future costs not yet reflected in the government’s financial position.

The following are some questions that parliamentarians could ask the government about infrastructure:

- What are the significant items on the government’s list of P3s? When will these projects be completed and when will costs be recorded in the financial statements?

- How is the government keeping track of significant assets that are near, or have reached, the end of their useful lives? How is the government ensuring that expected dismantling costs are properly reflected in its financial statements?

- What is the progress to date of the government’s 3-year review of capital assets? What is the expected outcome of the review?

The government’s financial statements discussion and analysis has improved, but its usefulness can still be enhanced

The financial statements discussion and analysis (FSDA) is a critical tool intended to help make financial information easier to understand and navigate. In our view, the government’s FSDA is falling short of achieving this goal.

In our Commentary on the 2015–16 Financial Audits, we encouraged the government to review its FSDA against best practices to improve its usefulness. Although the government made improvements in the 2017 FSDA, it was still not making sufficient use of the FSDA to help parliamentarians understand financial information.

As part of our audit of the government’s financial statements, we review the FSDA to ensure it is consistent with the information that we audit. This review allows us to identify opportunities to improve the FSDA’s usefulness.

Some significant risks and uncertainties aren’t discussed in the FSDA. For example, the FSDA could address the risks associated with contingent liabilities and income security programs, including an assessment of the potential impact of these risks on the government’s financial position.

Insight on capital assets within the FSDA continues to be limited. For example, it does not discuss how the government manages capital assets and the associated risks. The 2017 FSDA didn’t discuss current or planned significant investments like the Champlain Bridge and the Gordie Howe International Bridge, or plans to dismantle or otherwise dispose of capital assets that have reached or will soon reach the end of their useful lives. Some financial ratios regarding capital assets were presented without any interpretation or discussion. The government should consider enhancing the FSDA in these areas by using information included in other reports prepared by federal departments and organizations, such as departmental results reports.

In another area, the 2017 FSDA began with a discussion of recent economic developments, citing economic indicators such as the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) growth, interest rates, unemployment rate, inflation and oil prices. However, it didn’t link these indicators to the government’s financial position. A discussion on economic trends should address their recent or future impact on the government’s financial position.

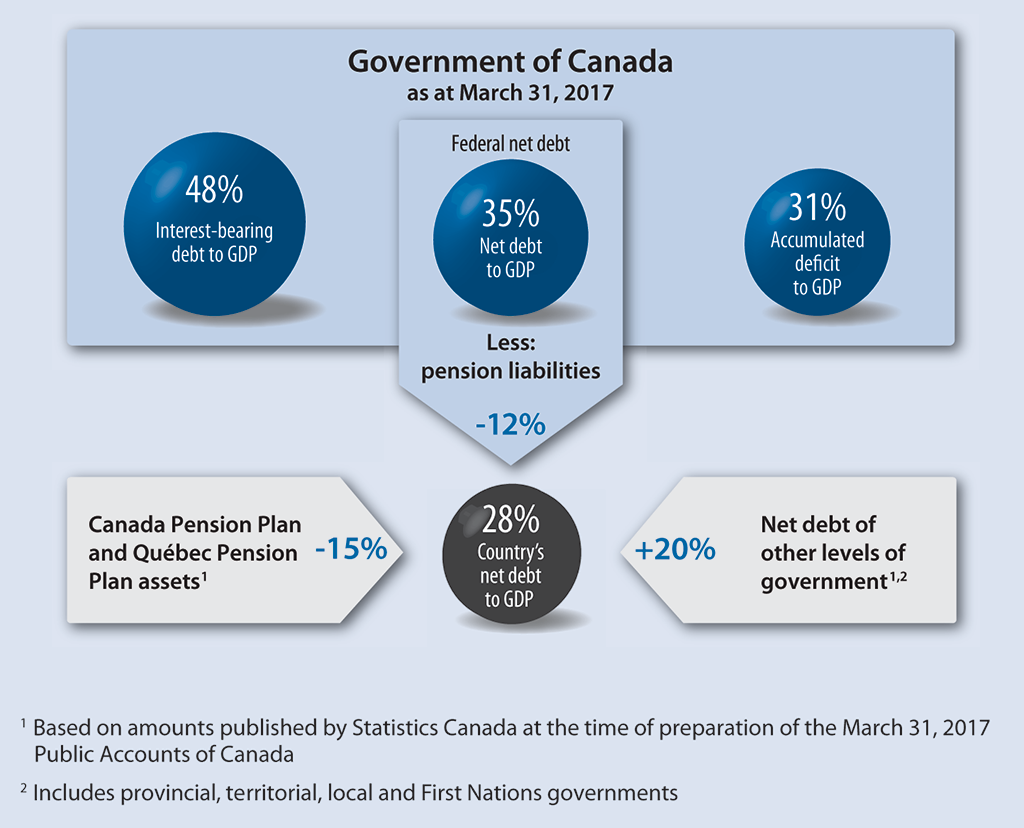

Regarding ratios, the government’s FSDA reported multiple debt-to-GDP ratios to express debt levels as a percentage of the country’s output, as shown in Exhibit 9. Although these ratios can be useful to assess the sustainability of the government’s overall financial policies, they have different meanings depending on how debt is defined. For example, the 3 ratios in the 2017 FSDA that were calculated using amounts found in the federal government’s financial statements, including the net debt-to-GDP ratio of 35%, are relevant to assess the federal government’s debt level.

Exhibit 9—Ratios of debt to gross domestic product (GDP) reported in the federal government’s financial statements discussion and analysis

Exhibit 9—text version

The FSDA shows the following four ratios of debt to gross domestic productGDP as at March 31, 2017:

- The Government of Canada interest-bearing debt-to-GDP ratio was 48%.

- The Government of Canada federal net debt-to-GDP ratio was 35%.

- The Government of Canada accumulated deficit-to-GDP ratio was 31%.

- The country’s net debt-to-GDP ratio was 28%.

This last ratio was calculated by taking the Government of Canada’s net debt-to-GDP ratio of 35%, subtracting its pension liabilities of 12%, subtracting the Canada Pension Plan and Québec Pension Plan assets of 15%, and adding the net debt of other levels of government of 20%, for a total of 28% as the country’s net debt-to-GDP ratio. The calculation of the country’s net debt-to-GDP ratio is based on amounts published by Statistics Canada at the time of preparation of the March 31, 2017 Public Accounts of Canada. The net debt of other levels of government includes provincial, territorial, local and First Nations governments.

However, the FSDA presented a fourth ratio—the country’s net debt-to-GDP ratio of 28% reported by the International Monetary Fund—which included the net debt of other levels of government as well as the net assets held in the Canada Pension Plan and Québec Pension Plan. The scope of this ratio is therefore broader and goes beyond the scope of the federal government’s financial statements. The purpose of this ratio is to compare Canada’s debt level with those of other countries. However, some countries don’t recognize their unfunded pension liabilities in their financial statements. The International Monetary Fund must therefore adjust Canada’s net debt-to-GDP ratio to exclude the unfunded liabilities of the Canadian public sector pension plans to achieve better comparability. As a result, although this ratio is more comparable with other countries following the International Monetary Fund adjustments, it does not accurately reflect Canada’s true net debt, because it excludes significant public sector liabilities. For that reason, including it in the FSDA can confuse and mislead readers seeking to understand the financial health of either the federal government or Canada as a whole. We encourage the government to enhance its FSDA by disclosing the exclusions and clarifying the limited use of this ratio.

Although all these ratios appeared in the FSDA, the differences between them weren’t readily apparent, nor were they explained. This means there is a risk that the numbers will be misunderstood and used incorrectly. Parliamentarians should use caution when using the various debt-to-GDP ratios reported in the FSDA.

We encourage the government to continue to improve the FSDA’s relevance and usefulness.

About our financial statement audits

Visit “Financial Audits” to find out more about the OAG’s work on the government’s financial statements.