2018 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada Independent Auditor’s ReportReport 5—Socio-economic Gaps on First Nations Reserves—Indigenous Services Canada

2018 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of CanadaReport 5—Socio-economic Gaps on First Nations Reserves—Indigenous Services Canada

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- List of Recommendations

- Exhibits:

- 5.1—Since 2001, the gap in high school graduation levels between on-reserve Indigenous people and other Canadians has widened

- 5.2—Australia reports annually on its progress in closing socio-economic gaps between Indigenous people and other Australians

- 5.3—British Columbia reported annually on the education results of Indigenous versus non-Indigenous students

- 5.4—Indigenous Services Canada overstated First Nations’ secondary school graduation or completion rates by up to 29 percentage points

Introduction

Background

5.1 According to Indigenous Services Canada, in December 2017, there were almost one million (987,520) individuals registered under the Indian Act, belonging to one of 618 First Nations or unaffiliated with a specific First Nation. Slightly more than half of the registered population (509,016) live on reserve or Crown land. Unless otherwise specified, “First Nations people” in this report refers to First Nations people on reserves.

5.2 First Nations people tend to have significantly lower socio-economic well-being than other Canadians. Socio-economic well-being can be measured by tracking indicators in areas such as education, income, and health. Closing socio-economic gaps means improving the social well-being and economic prosperity of First Nations people living on reserves.

5.3 To close socio-economic gaps and improve lives on reserves, federal decision makers and First Nations need information about the socio-economic indicators of First Nations people that is reliable, relevant, and up to date.

5.4 Indigenous Services Canada requires First Nations to provide extensive data about their on-reserve members. The Department also obtains data from Statistics Canada, other federal government departments, Indigenous organizations, and other sources.

5.5 Improving the lives of First Nations people requires a long-term approach. The first step in improving the lives of First Nations people is knowing what the current socio-economic gaps are. The second step is to regularly measure the gaps: If the gaps are not smaller in future years, it will mean that progress has not been made, which would mean that federal programs need to change. The federal government has access to data that can be used to inform decisions on federal programs and support and that can help effect real change and improve lives.

5.6 The federal government has made numerous commitments to meet Canada’s obligations to First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people. Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada was the lead government department responsible for meeting such commitments. The Department’s mandate was to support Indigenous and northern peoples in their efforts to

- improve social well-being and economic prosperity;

- develop healthier, more sustainable communities; and

- participate more fully in Canada’s political, social, and economic development.

5.7 In August 2017, the federal government announced the dissolution of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada and the creation of two departments: Indigenous Services Canada, and Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs. We audited Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada before August 2017 and, afterward, the newly formed Indigenous Services Canada, which is now the responsible department. Hereafter, this report refers only to Indigenous Services Canada.

5.8 The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, created in 2008, had a mandate to inform Canadians about what happened in Indian residential schools. The Commission’s final 2015 report included 94 calls to action, many of which referred to the socio-economic factors discussed in this audit. In 2015, the government committed to implementing these calls to action, coordinated by Indigenous Services Canada, including commitments to

- jointly develop strategies to eliminate education and employment gaps;

- identify, measure, and close the gaps in health outcomes between First Nations and other Canadian communities; and

- prepare and publish annual reports on these and other issues.

5.9 Also in 2015, the federal government committed to a renewed relationship with Indigenous people, based on rights, respect, cooperation, and partnership. The Department’s 2017–18 Departmental Plan forecast that it would spend about $10 billion to carry out its mandate.

5.10 In his mandate letter of November 2015, the Prime Minister directed the Minister of Indigenous and Northern Affairs to make real progress on issues essential to Indigenous communities, such as housing, employment, health care, community safety, child welfare, and education.

5.11 In 2000 and 2004, the Office of the Auditor General of Canada released reports highlighting the significant education gap between First Nations people on reserves and the Canadian population as a whole. These reports included recommendations to Indigenous Services Canada to improve its education programs and support for Indigenous post-secondary students. In the 2011 June Status Report of the Auditor General of Canada, Chapter 4—Programs for First Nations on Reserves, the Office criticized the federal government’s progress in improving the lives and well-being of people on reserves.

Focus of the audit

5.12 This audit focused on whether Indigenous Services Canada satisfactorily measured and reported on Canada’s overall progress in closing the socio-economic gaps between on-reserve First Nations people and other Canadians. It also focused on whether the Department made adequate use of data to improve education programs to close the education gap and improve socio-economic well-being.

5.13 Our reasons for examining the Department’s education programs include that

- education is critical to improving well-being on reserves;

- Indigenous Services Canada is the federal department responsible for providing education support for on-reserve First Nations students, and education has been the Department’s largest program in terms of overall spending; and

- Indigenous Services Canada collects significant amounts of education data from First Nations.

5.14 This audit is important because Indigenous Services Canada—the lead federal department responsible for managing federal support to improve quality of life for on-reserve First Nations people—needs to collect and analyze appropriate data to know whether its approach to improving lives on reserves is working.

5.15 We did not examine the performance of non-federal organizations, First Nations communities, or First Nations organizations. Nor did we assess whether the amount of money spent on programs and services on reserves was adequate.

5.16 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Measuring well-being on First Nations reserves

The Department did not have a comprehensive picture of the well-being of on-reserve First Nations people compared with other Canadians

Overall message

5.17 Overall, we found that Indigenous Services Canada’s main measure of socio-economic well-being on reserves, the Community Well-Being index, was not comprehensive. While the index included Statistics Canada data on education, employment, income, and housing, it omitted several aspects of well-being that are also important to First Nations people—such as health, environment, language, and culture.

5.18 We also found that the Department did not adequately use the large amount of program data provided by First Nations, nor did it adequately use other available data and information. The Department also did not meaningfully engage with First Nations to satisfactorily measure and report on whether the lives of people on First Nations reserves were improving. For example, the Department did not adequately measure and report on the education gap. In fact, our calculations showed that this gap had widened in the past 15 years.

5.19 These findings matter because measuring and reporting on progress in closing socio-economic gaps would help everyone involved—including Parliament, First Nations, the federal government, other departments, and other partners—to understand whether their efforts to improve lives are working. If the gaps are not smaller in future years, this would mean that the federal approach needs to change.

5.20 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

- Inadequate measurement of well-being

- Limited use of available data

- Incomplete reporting on well-being

- Lack of meaningful engagement

5.21 First published in 2004, the Department’s Community Well-Being index is its only publicly available overall measure of the socio-economic well-being of First Nations communities in comparison with other Canadian communities. The index is based on 1981 to 2011 census program data collected every five years for all Canadian communities, including First Nations that have a population of at least 65. The index measures four components:

- education (high school and post-secondary graduation),

- labour force (participation and employment),

- income (total per capita), and

- housing (overcrowding and need for major repairs).

5.22 The issues contributing to the socio-economic gaps between First Nations people and other Canadians are complex and challenging, and solutions depend on collaboration among First Nations, the federal and provincial governments, and other parties.

5.23 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 5.37.

5.24 What we examined. To determine whether Indigenous Services Canada adequately measured and reported on overall progress in closing socio-economic gaps between First Nations communities and other Canadians, we examined the Community Well-Being index, departmental documentation, and selected publicly available information. We also interviewed Department officials and representatives from selected provinces, First Nations, and First Nations organizations. In addition, we calculated rates of on-reserve and overall Canadian high school graduation (or equivalent) from 2001 to 2016.

5.25 Inadequate measurement of well-being. We found that the Department did not adequately measure well-being for First Nations people on reserves. The Community Well-Being index measured only four components of well-being: education, employment, housing, and income. While these are important aspects of well-being, the index did not include critical variables such as health, environment, language, and culture. First Nations have identified language and culture, in particular, as critical to their well-being.

5.26 Although the Department recognized that the index was incomplete, it did not modify the index to make it more comprehensive or establish a more complete measure or set of measures for assessing the well-being of on-reserve First Nations people.

5.27 In 2015, all member countries of the United Nations General Assembly, including Canada, adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The 2030 Agenda contains 17 sustainable development goals and 169 associated targets for achieving economic growth, social inclusion, and environmental protection. The 2030 Agenda is intended to mobilize global efforts to ensure healthy lives, end poverty, and fight climate change. In our opinion, Canada’s results against those 17 goals for First Nations people would likely be significantly worse than those for the whole Canadian population. In fact, according to the 2011 Community Well-Being index, 98 of the 100 lowest-scoring Canadian communities were First Nations communities.

5.28 From 2001 to 2011, the Community Well-Being index showed that gaps for all four components had widened. According to Indigenous Services Canada, between 2006 and 2011, about one third of First Nations communities (compared with one fifth of other Canadian communities) experienced a decline in the index scores. As of December 2017, the Department had not yet updated the Community Well-Being index with 2016 Census data.

5.29 Limited use of available data. We found that the Department could have used the volumes of available data from multiple sources to more comprehensively compare well-being relative to other Canadians and across First Nations communities, but did not. The Department had data and access to data from public sources, other departments, and First Nations, but did not include it in either the Community Well-Being index or another comprehensive measure or set of measures. We identified numerous sources of potentially useful data:

- The Department’s internal First Nation Community Profiles contained a large amount of data, including information on housing needs and water quality.

- Employment and Social Development Canada collected data about participation in skills training that Indigenous people received through the Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy and the Skills and Partnership Fund programs. These programs are intended to support Indigenous people in obtaining professional and industry certificates, diplomas, or degrees, as well as work experience and employment.

- Health Canada collected information about First Nations health, including information about oral health services and benefits that it provided to First Nations, as noted in the 2017 Fall Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Report 4—Oral Health Programs for First Nations and Inuit—Health Canada. The First Nations and Inuit Health Branch, which was responsible for that program at Health Canada, has since been transferred to the newly formed Indigenous Services Canada.

- In 2015, the Provincial Health Officer of British Columbia and the First Nations Health Authority issued a joint report, entitled First Nations Health and Well-being: Interim Update. This report provided an update on progress made on seven indicators: life expectancy, mortality rate, youth suicide rate, infant mortality rate, diabetes prevalence, childhood obesity, and the number of practising certified First Nations health care professionals.

- Provinces had data on how many Indigenous children were placed in the care of families with one or more Indigenous members, rather than in families with no Indigenous members. A different culture and language could make it more difficult for children to adjust to the new family environment.

- The First Nations Regional Health Survey 2008–10, conducted by the First Nations Information Governance Centre, identified the prevalence of chronic health conditions reported by First Nations adults on reserves across Canada.

5.30 Department officials told us that it did not incorporate this additional data into the Community Well-Being index because comparative data for other Canadian communities was not available. In our view, the Department should make better use of such data to more comprehensively assess and understand First Nations well-being in comparison with that of other Canadian communities, and to measure whether progress is being made.

5.31 In 2000, Indigenous Services Canada committed to measuring and reporting on the education gap every two years. As of December 2017, we found that the Department had not met this commitment. The index included a score for each of its four components, including education, to produce an overall score of well-being every five years. For example, in 2011, the average education score for First Nations communities was 36, while for Canadian non-Indigenous communities, it was 53. In our view, these scores did not provide a meaningful picture of the education gap because they did not provide a clear way to measure and report on education results.

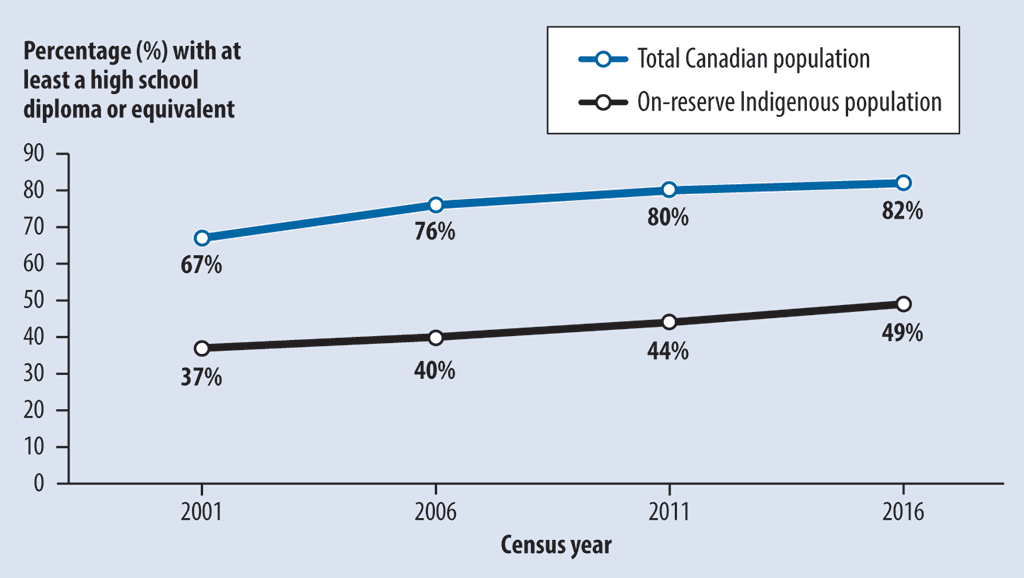

5.32 Using census program data, we calculated on-reserve and overall Canadian high school graduation (or equivalent) levels from 2001 to 2016 (Exhibit 5.1). We found that, while results for First Nations had improved, the results for all Canadians had improved by a greater amount: The gap was 30 percentage points in 2001 and 33 percentage points in 2016. In our view, this is a clearer way to measure and report on education results and would help to provide a more meaningful picture of well-being.

Exhibit 5.1—Since 2001, the gap in high school graduation levels between on-reserve Indigenous people and other Canadians has widened

Note: This chart is based on self-reported data of people aged 15 years and older within the given populations.

Source: Statistics Canada’s 2001, 2006, 2011, and 2016 census program data, provided by Indigenous Services Canada (unaudited)

Exhibit 5.1—text version

This graph compares the percentages over time of on-reserve Indigenous people with similar data for the total Canadian population. The comparison applies to the two populations of people aged 15 years and older who had at least a high school diploma or the equivalent. Since 2001, the education gap between the two populations has widened.

| Population | Percentage (%) with at least a high school diploma or equivalent | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 2006 | 2011 | 2016 | |

| On-reserve Indigenous | 37% | 40% | 44% | 49% |

| Total Canadian | 67% | 76% | 80% | 82% |

Note: This chart is based on self-reported data of people aged 15 years and older within the given populations.

Source: Statistics Canada’s 2001, 2006, 2011, and 2016 census program data, provided by Indigenous Services Canada (unaudited)

5.33 Incomplete reporting on well-being. We found that Indigenous Services Canada did not issue a comprehensive report on the overall socio-economic well-being of First Nations people on reserves. In comparison, we noted that, since 2009, the Prime Minister of Australia has issued annual reports, called Closing the Gap, with progress on improving the socio-economic well-being of Australian Indigenous people. These reports outline where more work is needed (Exhibit 5.2).

Exhibit 5.2—Australia reports annually on its progress in closing socio-economic gaps between Indigenous people and other Australians

In 2008, the Government of Australia and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples of Australia signed a statement of intent committing them to work together to achieve equal health and life expectancy by 2030. Since 2009, Australia has issued annual reports with the following specific targets:

- closing the life expectancy gap within a generation (by 2031);

- halving the gap in mortality rates for Indigenous children under five by 2018;

- ensuring that 95% of Indigenous four-year-olds in remote communities have access to early childhood education by 2025;

- halving the gap for Indigenous students in reading, writing, and numeracy by 2018;

- halving the gap for Indigenous people aged 20 to 24 in Year 12 or equivalent by 2020;

- halving the gap in employment outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians by 2018; and

- closing the gap in school attendance by the end of 2018.

Sources: Close the Gap, Indigenous Health Equality Summit, Statement of Intent, 2008; and Closing the Gap Prime Minister’s Report 2017 (unaudited)

5.34 Lack of meaningful engagement. Indigenous Services Canada did not work with First Nations to develop the Community Well-Being index, first published in 2004. Since then, we found that the Department has not revised the index to include language and culture or developed another comprehensive set of measures to assess First Nations well-being.

5.35 In July 2016, the Department engaged with First Nations and the Assembly of First Nations in a national forum to discuss criteria to measure First Nations students’ success. This work was targeted for completion by December 2017. We found that, in July 2017, the Chief’s Committee on Education directed First Nations representatives to stop working with Indigenous Services Canada. The Committee was concerned that federal processes did not allow enough time to develop measurement frameworks to reflect the diversity, autonomy, and authority of First Nations communities and education systems.

5.36 The federal government recognizes that engaging meaningfully with First Nations is essential to its mission of working together to make Canada a better place for Indigenous and northern peoples and communities. Given this mission, it is our view that greater efforts needed to be made to measure and report on the overall well-being of on-reserve First Nations people compared with that of other Canadians.

5.37 Recommendation. Through engagement with First Nations and other partners, Indigenous Services Canada should use relevant data to comprehensively measure and report on the overall socio-economic well-being of First Nations people on reserves compared with that of other Canadians. The Department should also measure and report on those additional aspects of socio-economic well-being that First Nations have identified as unique priorities, such as language and culture, which might not be directly comparable with other Canadians.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Indigenous Services Canada will build on the Community Well-Being index by co-developing, with First Nations and other partners, a broad dashboard of well-being outcomes that will reflect mutually agreed-upon metrics in measuring and reporting on closing socio-economic gaps. Much of this work is already under way with the Assembly of First Nations and other partners in the co-development of a new fiscal relationship. This includes a shared vision of mutual accountability and the co-development of a national outcome-based framework that leverages the United Nations’ 2030 sustainable development goals. As a part of the co-development, the Department will continue to work closely with First Nations to ensure that the broader reporting of First Nations’ well-being integrates other outcomes and measures that are important to them.

Collecting, using, and sharing First Nations’ education data

Overall message

5.38 Overall, we found that education results for First Nations students have not improved relative to those of other Canadians. We found that despite commitments the Department made 18 years ago, Indigenous Services Canada did not collect relevant data, or adequately use data to improve education programs and inform funding decisions. It also did not assess the relevant data it collected, for accuracy and completeness. Nor did the Department provide access to or regularly share its education information or the results of data analysis with First Nations. In addition, the Department was still unable to report how federal funding for on-reserve education compared with the funding levels for other education systems across Canada.

5.39 These findings matter because the Department and First Nations communities that deliver education need complete and accurate data to make evidence-based decisions and, ultimately, to improve education results and socio-economic well-being.

5.40 The goal of Indigenous Services Canada’s Elementary and Secondary Education Program is to help eligible students on reserves achieve levels of education that are comparable with those of other Canadian students. Through various funding arrangements with the Department, First Nations deliver education on reserves, buy education services from school boards, or combine these two approaches. There are also seven federally operated schools on reserves. In all cases, the Department requires First Nations to provide data about their education programs.

5.41 At the post-secondary level, Indigenous Services Canada aims to help First Nations students develop job skills by giving them financial support for education and skills development. The Department transfers funds to First Nations for eligible students, whether they live on or off reserves. All First Nations recipients are required to report the results and related spending information for funded post-secondary students.

5.42 The Office of the Auditor General reported on Indigenous Services Canada’s education programs in 2000, 2004, and 2011. In response to our past recommendations, the Department made commitments to closing the education gap. In particular, 18 years ago (in 2000), the Department promised to

- develop and use appropriate performance indicators,

- develop and use comparative cost information, and

- publish a report every two years on progress toward closing the education gap between on-reserve First Nations students and other Canadians.

5.43 According to the Department’s documents, for the 2016–17 fiscal year, Indigenous Services Canada spent about $2.1 billion on education operations. The number of elementary and secondary students on reserves in the 2016–17 fiscal year was about 107,000, and the number of funded post-secondary students was estimated to be about 24,000.

The Department did not collect data needed to improve education results

5.44 We found that Indigenous Services Canada did not collect data it needed to improve education results. In particular, it did not collect

- information about education, such as teachers’ years of experience or student participation rates;

- information about post-secondary graduation rates; and

- information to compare First Nations students’ education levels with those of other Canadians.

5.45 Furthermore, we found that the Department did not assess relevant data it did collect, to determine whether it was accurate and complete. For example, it did not know to what extent First Nations students were graduating from high school with diplomas recognized by post-secondary institutions, or with completion certificates, which the Department acknowledged might not be recognized by these institutions.

5.46 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

5.47 This finding matters because reliable, relevant, and up-to-date data is essential to making evidence-based decisions for improving education levels for First Nations students. When First Nations students are unable to proceed to higher education, their socio-economic status is also likely to suffer over the long term.

5.48 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 5.83.

5.49 What we examined. We examined whether Indigenous Services Canada collected information to measure and report on First Nations’ education results, such as graduation rates. We also analyzed this data for accuracy and completeness.

5.50 Not collecting relevant data. In 2010, Indigenous Services Canada developed the Education Performance Measurement Strategy to measure results for First Nations students and schools and to determine whether its students achieved education results comparable with those of other Canadian students.

5.51 We found that the Department did not collect the information needed to compare First Nations’ education results with those of other Canadian students. For example, it did not collect provincial or national data on standardized test scores and student attendance rates to allow for comparisons. Without this information, the Department did not know whether its approach to managing programs to educate First Nations students was helping to close the education gap.

5.52 We also found that the Department did not collect important data from First Nations on primary and secondary education programs. For example, the Department did not collect data about teacher experience or student participation rates. Without this data, the Department did not have a complete picture of First Nations’ education programs.

5.53 We also found that the Department did not have data about post-secondary graduation rates for on-reserve First Nations students. Nor did it collect complete data on the number of First Nations students who wanted to pursue post-secondary education but could not access the funds to do so. Despite commitments by the Department to review these issues in 2004, it was still unable to report on the extent to which its support for First Nations’ post-secondary education improved student results or whether its delivery model ensured that eligible students had equitable access to post-secondary education funding.

5.54 Not assessing relevant data. We found that the Department did not distinguish between high school diplomas and high school completion certificates. According to the Department, the certificates might not be recognized by post-secondary institutions. We found that, for the 214 First Nations schools that offered Grade 12 in the 2016–17 fiscal year, the Department did not collect information on the type of diploma or completion certificate provided to First Nations students. Similarly, the Department did not collect this information about First Nations students attending provincially operated schools.

5.55 Using analysis that the First Nations Education Steering Committee conducted on data collected by the Ministry of Education in British Columbia, we calculated that between the 2012–13 and 2015–16 fiscal years, about 14.5% (380 of 2621) of on-reserve students who finished high school received completion certificates. In comparison, only 2% (2,365 of 118,250) of non–First Nations students in British Columbia received completion certificates over the same period. In our view, by not distinguishing between official diplomas and completion certificates, the Department and First Nations could not determine how many First Nations graduating students might not be eligible to attend post-secondary institutions.

The Department did not adequately use data to improve education results

5.56 We found that Indigenous Services Canada did not adequately use data to improve education results. We found data the Department had collected that could have been used to improve education programs, but was not. For instance, the Department did not analyze First Nations students’ literacy levels to determine how they compared with those of other Canadians. Nor did it assess whether departmental support was achieving expected results, or how the support could be improved.

5.57 We also found that the Department had not adequately used data to determine education funding. We found that it was unclear to what extent funding decisions considered First Nations students’ unique education needs and important factors affecting costs. We found that, despite its commitment to do so in 2000, the Department did not report on how federal funding for on-reserve education compared with funding in other Canadian education systems.

5.58 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

- Inadequate use of data to improve education programs

- Inadequate use of data to inform funding decisions

5.59 These findings matter because low graduation and literacy rates have a negative impact on the lives of on-reserve First Nations people—in particular, through reduced employment opportunities. Because the education gaps are complex—varying by region, population, student age, and over time—closing the gap requires the use of data that is accurate, comprehensive, and up to date.

5.60 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 5.83.

5.61 What we examined. We examined whether Indigenous Services Canada used data to improve education program results relative to those of other Canadians. We also looked at whether it used data to inform funding decisions and whether it had reported on how federal funding for on-reserve education compared with funding in other Canadian education systems.

5.62 Inadequate use of data to improve education programs. In 2008, Indigenous Services Canada identified literacy as a national priority. According to the Department, research has shown that literacy has a strong impact on future potential careers, socio-economic stability, and decision-making abilities. As well, literacy improves education results and student retention during a student’s entire educational career.

5.63 We found that, despite collecting literacy information from First Nations for on-reserve students who participated in standardized testing, the Department did not analyze students’ literacy levels to determine whether its support improved results. Our analysis of departmental data on literacy rates showed that between the 2013–14 and 2015–16 fiscal years, the number of students who met or exceeded literacy levels improved for both male and female students in only one of the five regions where data was available. We found that the Department did not compare First Nations literacy levels with data from other Canadian jurisdictions and did not use this information to inform its support for literacy programs.

5.64 We also noted other examples where the Department did not adequately use data to modify its programs. For example, according to the Department, $42 million in departmental funding was allocated by First Nations over four fiscal years (2012–13 to 2015–16) to support the University and College Entrance Preparation Program. This program was intended to help First Nations students obtain the academic level needed to enter post-secondary programs. Our analysis of departmental data during this period found that of 4,919 students who received assistance, only 397 (8.1%) completed their programs. Despite these consistently poor results, we found that the Department did not work with First Nations or educational institutions to make changes that could increase the success rate of students in the program.

5.65 We also found that the Department was inconsistent in its funding approach to educating students over the age of 21. The Department’s Elementary and Secondary Education Program was intended for students aged 4 to 21. Although the Department knew that a significant number of students over the age of 21 were funded under this program, it did not use this information to make program adjustments. Our analysis of the departmental data showed that from the 2000–01 to 2016–17 fiscal years, 17% of students enrolled in the last year of high school were older than 21.

5.66 According to the Department’s estimate, in one region, the cost of providing education to students over 21 was about $15 million in the 2011–12 fiscal year. Department officials told us that if students were in school when they turned 22, they would continue to be funded. However, older students requesting to return to school were denied funding. In our view, the Department could explore ways to help First Nations students over 21 years old complete secondary education.

5.67 Inadequate use of data to inform funding decisions. Through a combination of core and supplemental programs, Indigenous Services Canada funded eligible on-reserve First Nations students to attend First Nations–operated, federal, private, or provincial schools.

5.68 In 2000, the Department committed to developing and using comparative cost information. This information is important for ensuring that First Nations students receive education comparable to that of other Canadians. Knowing these costs is important for developing an effective education strategy, closing the education gap, and meeting the education needs of First Nations students living on reserves. However, we found that, as of 2017, this work was still not complete, and that the Department was still unable to report how federal funding for on-reserve education compared with funding levels for other education systems across Canada.

5.69 We also found that, in arriving at its core funding decisions, it was not clear to what extent the Department accounted for the unique needs of First Nations students. For example, education costs could increase or decrease, depending on important factors affecting costs, such as

- geographic isolation of many First Nations communities;

- small school populations, common in many First Nations communities;

- the first language of First Nations students (English or French not being the first language for a significant number of First Nations); and

- difficulty in attracting and retaining qualified educators.

According to the Department, its method of calculating core education funding for First Nations had not substantively changed since the late 1990s. The formula relied on historical and out-of-date population data and did not consistently account for the above important factors in costing.

5.70 To supplement its core education funding budget, the Department received an additional $2.6 billion over five fiscal years, from 2016–17 to 2020–21. We found that the Department’s analysis to support this amount was insufficient. For example, included in this amount was $577.5 million, or $115.5 million annually, for the High-Cost Special Education Program. The only evidence the Department provided to substantiate the annual $115.5 million increase was that spending on this program had exceeded the budget by $22 million in the 2012–13 fiscal year. The Department also determined that about 4,400 of the 13,000 students in the program required a new or updated assessment, but it did not provide a cost estimate for doing the needed assessments.

5.71 We also found that the Department could not provide analysis to support its language and culture funding of $275 million, or about $55 million annually, between the 2016–17 and 2020–21 fiscal years. According to the Department, this amount was based on a proposal from one region that was then applied nationally, regardless of specific conditions.

The Department required considerable education data from First Nations but did not share the resulting analyses with them

5.72 We found that, although First Nations communities were required to supply extensive education data to Indigenous Services Canada, the Department did not provide the promised access to its Education Information System. Therefore, First Nations could not access the resulting information and analyses.

5.73 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

- Limited access by First Nations to the Department’s Education Information System

- High administrative burden for First Nations

5.74 This finding matters because without access to education data and related analyses, First Nations communities cannot meaningfully engage with Indigenous Services Canada to improve education results or identify initiatives that would contribute to student success.

5.75 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 5.83.

5.76 What we examined. We reviewed information on the Education Information System and the volume of information that First Nations were required to provide. We examined whether the Department shared useful analyses of this data with First Nations.

5.77 Limited access by First Nations to the Department’s Education Information System. In 2008, the Department proposed that it would develop a system to capture First Nations’ education program data, which First Nations could access as well.

5.78 In 2010, the Department again committed that the system would be a shared information resource with First Nations. The Department also identified the need to reduce the reporting burden to First Nations. First Nations were required to provide 20 annual reports, using data gathered from about 1,500 sources, including

- 119,000 elementary and high school students,

- 19,000 post-secondary students,

- 450 reports on proposal-based education initiatives, and

- activities by 110 cultural education centres.

5.79 A December 2015 internal audit of the system found that First Nations had only limited access to reporting tools to compare, for example, how students in their communities were doing relative to those from other regions. Furthermore, First Nations received little training on how to use the system. The audit also found that some regions were using their own processes and tools to track and report on education data, which increased their workload.

5.80 We found that, as of 2017, Indigenous Services Canada still had not provided First Nations and their organizations with access to education information and related analyses in the Education Information System. According to the Department, from the 2008–09 to 2017–18 fiscal years, it spent about $64 million to develop, implement, and operate its Education Information System.

5.81 High administrative burden for First Nations. First Nations told us that the reporting requirements related to education programs were burdensome. We found that, in the 2017–18 fiscal year, the Department’s education reporting requirements included up to 13 forms with 920 data fields. Many of these fields had to be filled in for each student supported by the Department—about 107,000 elementary and secondary and an estimated 24,000 post-secondary students in the 2016–17 fiscal year.

5.82 We also found that the Department did not use much of the data it collected to improve education results (as detailed in paragraphs 5.62 to 5.66) or inform important funding decisions (paragraphs 5.67 to 5.71). Furthermore, First Nations and their organizations did not have full access to the education information gathered, or to the related analyses (paragraphs 5.77 to 5.80). In our view, not using this data created an unnecessary administrative burden for First Nations.

5.83 Recommendation. Through engagement with First Nations and other partners, Indigenous Services Canada should collect, use, and share data with First Nations appropriately to improve education results of First Nations people on reserves.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Indigenous Services Canada has invested in relationships with First Nations to manage data related to education, including ongoing collaboration to identify meaningful education results that would replace the current approach. These renewed education goals, together with agreed-upon measures and a data collection strategy, will be developed as part of the upcoming education transformation for elementary, secondary, and post-secondary education. In the meantime, the Department is actively exchanging data with First Nations to support education transformation.

Reporting on First Nations’ education results

The Department’s reporting was incomplete and inaccurate

Overall message

5.84 Overall, we found that the Department’s reporting to Parliament on education was inaccurate. The Department’s method of calculating and reporting the on-reserve high school graduation rate of First Nations students overstated the graduation rate because it did not account for students who dropped out between grades 9 and 11. For example, the Department’s reported data showed that, from 2011 to 2016, on average, about one in two (46%) First Nations students graduated, whereas our calculations showed that, on average, only about one in four (24%) students actually completed high school within 4 years. Moreover, between the 2014–15 and the 2015–16 fiscal years, the Department’s data showed that the graduation rate was improving, but our calculations showed that it was declining.

5.85 We also found that the Department did not report on most (17 of 23) education results it had committed to reporting on, to determine whether progress was being made to close the gap. For example, it did not report on student attendance or the delivery of First Nations’ language instruction.

5.86 These findings matter because, without complete and accurate information, Canadians, First Nations, and parliamentarians were not fully informed about the true extent of First Nations’ education results or the education gap.

5.87 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

5.88 Treasury Board policies require departments to develop valid and reliable indicators with measurable targets and to obtain reliable, regular, and accurate data to monitor and report on progress.

5.89 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 5.98.

5.90 What we examined. We examined whether Indigenous Services Canada publicly reported complete and accurate information on its overall progress on closing the education gap between on-reserve First Nations students and other Canadians. We also examined data from the Department’s Education Information System to determine whether the high school graduation rate accounted for students who withdrew from school before starting Grade 12.

5.91 Incomplete reporting. In 2000, the Department committed to developing appropriate performance indicators and publishing a report every two years on closing the education gap between on-reserve First Nations students and other Canadians. In 2010 and 2014, Indigenous Services Canada developed Education Performance Measurement Strategies that committed to specific performance measures.

5.92 We found that the Department did not report results for most of the measures. In particular, its 2014 strategy contained 23 specific measures, but we found that the Department never reported on 17 of them. For example, it did not report on student attendance and First Nations’ language instruction. We also found that, despite the ultimate objective of both strategies that First Nations achieve levels of education comparable to those of other Canadians, the Department did not compare First Nations results with the results of other Canadians for measures in either strategy. We noted that British Columbia published an annual report comparing the education results of Indigenous students with those of non-Indigenous students (Exhibit 5.3). This type of report offered a good example of how the Department could report on education results.

Exhibit 5.3—British Columbia reported annually on the education results of Indigenous versus non-Indigenous students

Since the 1998–99 fiscal year, the Government of British Columbia has published How Are We Doing?, an annual report comparing results for Indigenous and non-Indigenous students in its provincial public schools. The report helps the Ministry of Education, Indigenous communities, and school districts to discuss the issues, make recommendations, and take action to improve educational results for Indigenous students.

The report provides side-by-side comparisons of Indigenous and non-Indigenous student results for the province as a whole and for individual school districts. It includes information on a variety of measures, including results from Grade 4 and Grade 7 standardized tests in reading, writing, and numeracy, as well as average final marks for all mandatory courses for grades 10, 11, and 12. The report also provides information on high school completion rates for Indigenous and non-Indigenous students, including a breakdown of students who receive official graduation diplomas versus completion certificates.

Finally, the report includes information on how well Indigenous and non-Indigenous students make the transition from high school to post-secondary institutions.

Source: Based on information from British Columbia’s 2015–16 How Are We Doing? report (unaudited)

5.93 We also found that Indigenous Services Canada did not report against consistent targets for the performance measures it had identified in its 2010 and 2014 strategies. Setting consistent and measurable targets helps to improve results and achieve systemic change. Yet, in the seven fiscal years from 2010–11 to 2016–17, the Department reported the First Nations’ high school graduation rate for six years and the available literacy rates for four years. During this period, the Department’s target for graduation rates changed four times, and it did not develop a specific target for literacy rates until the 2016–17 fiscal year.

5.94 Inaccurate reporting of graduation rates. We found that the Department’s reported graduation rate for on-reserve First Nations students was inaccurate. It reported a graduation rate that included only students enrolled in their final year of high school. This meant that the reported graduation rate was overstated, because students who dropped out in grades 9, 10, and 11 were excluded from the Department’s calculation. Using data only from a student’s final year of high school is inconsistent with how most provincial governments and the Council of Ministers of Education calculate graduation rates. For example, Manitoba divides the total number of graduates by the total number of students who were enrolled in Grade 9 four years earlier.

5.95 Using departmental data from the 2011–12 to the 2015–16 fiscal years, we calculated a graduation or completion rate that accounted for all students who dropped out in grades 9, 10, and 11 (Exhibit 5.4). We found that these rates were 10 to 29 percentage points lower than those reported by the Department. This means that the Department’s reported data showed, on average, that about one in two (46%) First Nations students graduated. However, our calculations showed that, on average, only about one in four (24%) students who started Grade 9 actually completed high school within 4 years. In our view, anyone relying on departmental information would not be fully informed. For example, the Department reported that graduation rates between the 2014–15 and 2015–16 fiscal years had improved—while we found that they had worsened.

Exhibit 5.4—Indigenous Services Canada overstated First Nations’ secondary school graduation or completion rates by up to 29 percentage points

| Fiscal year | Department’s published rates of graduation or completion (Grade 12 only) |

Our calculated rates of graduation or completion (Grades 9 to 12) |

Department’s overstated difference (in percentage points) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011–12 | 49% | 20% | 29 |

| 2012–13 | 50% | 24% | 26 |

| 2013–14 | 53% | 26% | 27 |

| 2014–15 | 37% | 27% | 10 |

| 2015–16 | 40% | 24% | 16 |

| Five-year average | 46% | 24% | 22 |

Note: According to departmental documentation, changes to data collection methods led to a significant increase and inaccurate results in the First Nations students’ graduation rates reported for the 2011–12, 2012–13, and 2013–14 fiscal years. This data error was corrected in the 2014–15 fiscal year, which resulted in lower reported graduation rates in the 2014–15 and 2015–16 fiscal years.

Sources: Based on Indigenous Services Canada’s Education Information System data and departmental results reports

5.96 In addition, the Department’s reported graduation rate (see Exhibit 5.4) included both students who graduated with provincially recognized high school diplomas (or their equivalents) and those who received high school completion certificates (or their equivalents). Yet students with completion certificates might not have been eligible for enrolment in post-secondary institutions. In our view, these different rates should be reported separately. We note that, because of this issue, our calculated rates in Exhibit 5.4 are also overstated, because the Department’s data did not distinguish between high school graduation and completion.

5.97 Another example of inaccurate reporting was how the Department reported on the University and College Entrance Preparation Program results. In its 2014–15 Departmental Performance Report, the Department reported that, in the 2011–12 fiscal year, 1,017 students were in transition from a University and College Entrance Preparation Program to a post-secondary institution. We found, and the Department confirmed, that this was a mischaracterization of results. In fact, the number reported was simply the number of students funded, not the number of students accepted into post-secondary institutions.

5.98 Recommendation. Indigenous Services Canada’s reporting on First Nations’ education results should be complete and accurate.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Indigenous Services Canada is actively working with First Nations to transform elementary and secondary education, and will be co-developing renewed education outcomes, measurements, and a related data strategy. Likewise, the Department is working with First Nations and other Indigenous partners to transform post-secondary education. Embedded in the approach to renewed education will be agreement on mutual accountability and practices promoting complete and accurate reporting.

Conclusion

5.99 We concluded that Indigenous Services Canada did not satisfactorily measure or report on Canada’s progress in closing the socio-economic gaps between on-reserve First Nations people and other Canadians. We also concluded that the Department’s use of data to improve education programs was inadequate.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on socio-economic gaps between on-reserve First Nations people and other Canadians. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs, and to conclude on whether the Department’s use of data, including measuring and reporting, complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office applies Canadian Standard on Quality Control 1 and, accordingly, maintains a comprehensive system of quality control, including documented policies and procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we have complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit;

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit;

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided; and

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate.

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether Indigenous Services Canada satisfactorily measured and reported on Canada’s overall progress in closing the socio-economic gaps between on-reserve First Nations people and other Canadians, and whether the Department adequately used appropriate data to improve education programs to close education gaps.

Scope and approach

We examined whether Indigenous Services Canada had engaged with First Nations to define what components should be used to measure the social well-being and economic prosperity of on-reserve First Nations people relative to other Canadians. We examined how the Department measured and reported on overall progress in closing socio-economic gaps.

We also examined whether Indigenous Services Canada engaged with First Nations to make adequate use of data to improve programs intended to close education gaps.

The audit scope did not include

- the performance of non-federal organizations, First Nations communities, or First Nations organizations; or

- an assessment of the adequacy of federal resources spent on programs and services for on-reserve First Nations.

In brief, the audit approach comprised

- interviews with officials from the federal government, provincial governments (Manitoba and British Columbia), First Nations communities, and First Nations organizations;

- visits to seven First Nations communities in two regions;

- analyses of data from Indigenous Services Canada’s Education Information System; and

- examination of other relevant documentation and information.

Criteria

To determine whether Indigenous Services Canada satisfactorily measured and reported on Canada’s overall progress in closing the socio-economic gaps between on-reserve First Nations people and other Canadians, and whether the Department adequately used appropriate data to improve education programs to close education gaps, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Working with First Nations and other federal departments, Indigenous Services Canada

|

|

|

Indigenous Services Canada uses appropriate data to assess progress and improve the outcomes of programs intended to close education gaps between First Nations people on reserves and other Canadians. (For the purpose of this audit, “uses” means collects, analyzes, and shares data with First Nations, and reports publicly on progress.) |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period between April 2015 and December 2017. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies. However, to gain a more complete understanding of the subject matter of the audit, we also examined certain matters that preceded the starting date of this period.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 11 April 2018, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

Principal: Joe Martire

Director: Dawn Campbell

Alex Fontaine

Sean MacLennan

Joseph O’Brien

Jacqueline Warren

List of Recommendations

The following table lists the recommendations and responses found in this report. The paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report, and the numbers in parentheses indicate the location of the related discussion.

Measuring well-being on First Nations reserves

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

5.37 Through engagement with First Nations and other partners, Indigenous Services Canada should use relevant data to comprehensively measure and report on the overall socio-economic well-being of First Nations people on reserves compared with that of other Canadians. The Department should also measure and report on those additional aspects of socio-economic well-being that First Nations have identified as unique priorities, such as language and culture, which might not be directly comparable with other Canadians. (5.24 to 5.36) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. Indigenous Services Canada will build on the Community Well-Being index by co-developing, with First Nations and other partners, a broad dashboard of well-being outcomes that will reflect mutually agreed-upon metrics in measuring and reporting on closing socio-economic gaps. Much of this work is already under way with the Assembly of First Nations and other partners in the co-development of a new fiscal relationship. This includes a shared vision of mutual accountability and the co-development of a national outcome-based framework that leverages the United Nations’ 2030 sustainable development goals. As a part of the co-development, the Department will continue to work closely with First Nations to ensure that the broader reporting of First Nations’ well-being integrates other outcomes and measures that are important to them. |

Collecting, using, and sharing First Nations’ education data

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

5.83 Through engagement with First Nations and other partners, Indigenous Services Canada should collect, use, and share data with First Nations appropriately to improve education results of First Nations people on reserves. (5.49 to 5.55, 5.61 to 5.71, 5.76 to 5.82) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. Indigenous Services Canada has invested in relationships with First Nations to manage data related to education, including ongoing collaboration to identify meaningful education results that would replace the current approach. These renewed education goals, together with agreed-upon measures and a data collection strategy, will be developed as part of the upcoming education transformation for elementary, secondary, and post-secondary education. In the meantime, the Department is actively exchanging data with First Nations to support education transformation. |

Reporting on First Nations’ education results

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

5.98 Indigenous Services Canada’s reporting on First Nations’ education results should be complete and accurate. (5.90 to 5.97) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. Indigenous Services Canada is actively working with First Nations to transform elementary and secondary education, and will be co-developing renewed education outcomes, measurements, and a related data strategy. Likewise, the Department is working with First Nations and other Indigenous partners to transform post-secondary education. Embedded in the approach to renewed education will be agreement on mutual accountability and practices promoting complete and accurate reporting. |