Commentary on the 2017–2018 Financial Audits

Commentary on the 2017–2018 Financial Audits

Background to the Commentaries on Financial Audits

Message from the Auditor General of Canada

I’m pleased to present this commentary report on the results of our link to Financial Audit Glossaryfinancial audits.

This report isn’t an audit report. Instead, it highlights the results of the financial audits we—the Office of the Auditor General of Canada—conducted in federal organizations for the fiscal years ended between July 2017 and April 2018 (the 2017–2018 financial audits). It also provides a commentary based on those audit results.

This commentary includes a lot of information. I’ll start with my summary of what a reader should take from this report.

Overall, we’re pleased that the Government of Canada has shown:

- a commitment to its financial accounting and reporting practices—the 20th “clean” audit opinion in a row

- a much better accounting for the value of its pension promises

- an adherence to its plan to improve its accounting for National Defence inventory

- a way forward to produce link to Financial Audit Glossaryfinancial statements for National Defence’s Reserve Force pension plan (with this way forward, we’ll be able to provide an audit opinion in the short term)

There’s one significant blemish on this record: The government still has not shown signs that it has reduced the impact of pay errors coming from its transformation of pay administration, which includes the Phoenix pay system.

This commentary also includes other information that we believe will help an interested reader see a little bit behind the numbers to better understand the government’s financial management.

We produced this commentary for 3 reasons:

- to explain the extent of our financial audit work

- to present the Auditor General’s observations on the government’s consolidated financial statements

- to provide information about certain financial topics that we believe would be of interest to parliamentarians

Our 2017–2018 financial audits covered 69 federal organizations, including the Government of Canada. I’m very pleased to say that we provided an link to Financial Audit Glossaryunmodified audit opinion on the government’s consolidated financial statements for the 20th consecutive year. This means that for 20 years, the Government of Canada has met the requirements for clarity, completeness, accuracy and timeliness in its financial reporting.

An unmodified opinion demonstrates that the government takes financial reporting seriously and is committed to accounting for its transactions properly. Twenty years of unmodified opinions also shows that a series of successive governments have made the same commitment.

In fact, 68 of the 69 financial statements of federal organizations we audited met the requirements for clarity, completeness, accuracy and timeliness to which they were subject. The one exception was National Defence’s Reserve Force pension plan, for which we again could not issue an audit opinion on the financial statements because of persistent problems with the department not retaining documentation to support the estimated value of pensions that the plan will have to pay. This problem has persisted for some time, but we’ve worked with the department and now expect the problem to be resolved in the short term.

This year for the first time, this commentary includes the Auditor General’s observations on the government’s consolidated financial statements. In the past, these observations were published as part of the link to Financial Audit GlossaryPublic Accounts of Canada, which the Government of Canada presents in Parliament each fall. We made this change because we felt it was better to have all commentary on our financial audits in our report.

The Auditor General’s observations explain significant items that we identified as part of our audit of the government’s consolidated financial statements, and that we felt should be brought to Parliament’s attention. This year, we have observations in 3 areas—all of which we also raised last year:

- Our first observation explains the extent of errors we identified in the government’s pay transactions—which indicates no improvement from last year.

- Our second observation is positive. We’re very pleased that the government was able to complete its review of government discount rates. Experience demonstrated that over the past number of years, the link to Financial Audit Glossarydiscount rates that the government used to calculate the value of its unfunded promises to pay future pensions were at the higher end of the acceptable range. The government completed a thorough analysis of how it determines discount rates for all its long-term liabilities and made the appropriate adjustment. We are of the opinion that this resulted in a much better estimate of what the government owes. This change caused the government’s liabilities to increase by several billions of dollars, but the effect accumulated over many years. It took time to properly analyze the government’s accounting policy to calculate discount rates for its unfunded pension promises, and this year, a new accounting policy has been adopted that gives the government a better estimate of its link to Financial Audit Glossaryunfunded pension liability.

- Our third observation is about National Defence inventory. This continues to be a problem, and while it has not been resolved, we’re satisfied that the department made the progress it told the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts that it would make. If the department continues with its published plan to improve management of inventory, it should be able to reduce many of the accounting concerns we have—however, that plan will still take many years to fully implement.

In this commentary, we also let parliamentarians know that:

- many federal organizations have granted access to some of their computer systems to people who do not need access

- while the government improved its financial statements discussion and analysis (FSDA), more can be done to enhance the FSDA’s usefulness in informing parliamentarians about the consolidated financial statements of the Government of Canada

In addition, we provide examples of ongoing or planned significant and complex projects with information technology components. These projects need to be well managed to prevent failures similar to those of Phoenix. We also provide information to help parliamentarians better understand how the budgeted expenses are reflected in the Main Estimates, and how budgeted expenses are distributed between statutory expenditures and voted expenditures, to help them review both types of expenditures.

Results of the 2017–2018 financial audits

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada provided the Government of Canada with an unmodified audit opinion on its consolidated financial statements for the 20th consecutive year. This opinion is an important contribution to Canada’s ability to meet its commitments under the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. In particular, it helps Canada meet Sustainable Development Goal 16.6: “Build effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels.”

Overall, we were satisfied with the timeliness and credibility of 68 out of 69 financial statements prepared by the Government of Canada and the federal organizations that the Office audits.

The exception was National Defence’s Reserve Force pension plan. We could not issue an audit opinion on the plan’s financial statements because of significant and persistent problems with the department not retaining all the documents that support the data used to estimate pension obligations. National Defence is currently developing methods to retain this information. We expect the department to make progress in resolving this matter over the next couple of years.

We noted 3 instances of non-compliance during 2 audits. Two of these instances related to the appointment of officer-directors. These came up during the audits of Ridley Terminals incorporatedInc. and the Canada Development Investment Corporation. The third instance related to the remuneration paid to the chief executive officer of Ridley Terminals Inc.

For more details about the audit of Ridley Terminals Inc., refer to our independent auditor’s report, included in the organization’s link to a portable document format (PDF) file2017 Annual Report, and to our 2018 Special Examination of the organization. For more details about the audit of the Canada Development Investment Corporation, refer to our independent auditor’s report, included in the corporation’s link to a portable document format (PDF) file2017 Annual Report, and to our link to a portable document format (PDF) file2018 Special Examination of the corporation.

Opportunities for improvement noted in the 2017–2018 financial audits

Financial audits identify opportunities for organizations to improve their systems of internal control, streamline their operations or enhance their financial reporting practices. We issue link to Financial Audit Glossarymanagement letters to inform the organizations we audit about these opportunities. We also issue these letters to inform them about more serious issues, such as inadequate internal controls that can create risks of errors in financial reports.

As part of our annual financial audits, we follow up on the points we’ve raised in previous years so we can monitor management’s progress in addressing them.

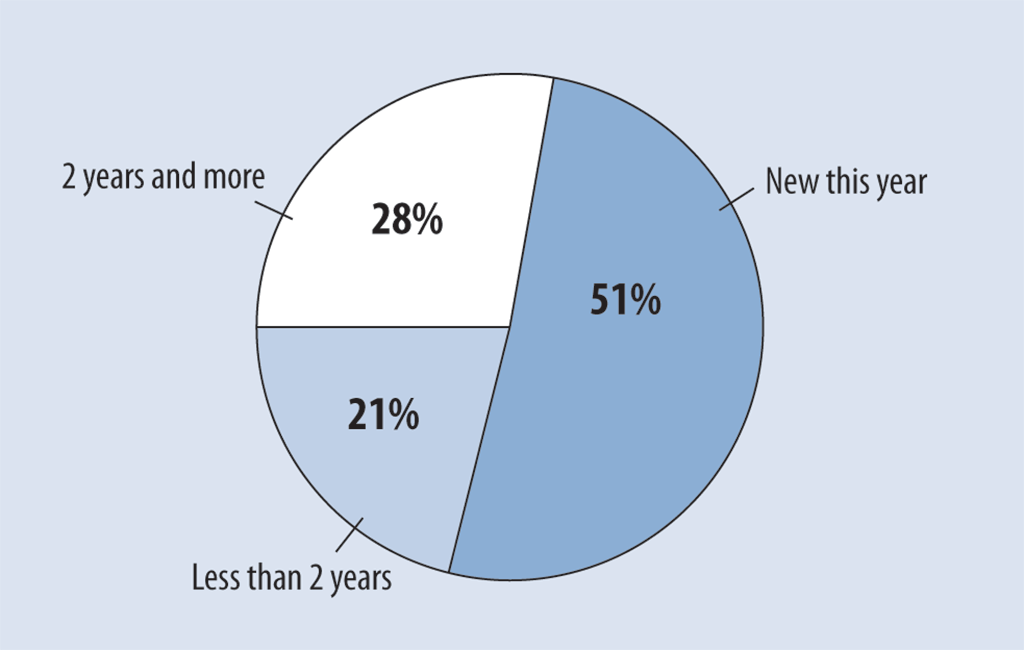

Of the total management letter points that were unresolved as of June 30, 2018, for our 2017–2018 financial audits, 72% were either newly issued (51%) or had been unresolved for less than 2 years (21%) (Exhibit 1). This is positive. It means that in most cases, organizations are quick to address the points we raise.

Exhibit 1—Unresolved observations from the 2017–2018 financial audits

Exhibit 1—text version

This pie chart breaks down how long unresolved observations from the 2017–2018 financial audits had been unresolved. In descending order, the percentages are as follows:

- 51% of unresolved observations were new this year.

- 28% of observations had been unresolved for 2 years or more.

- 21% of observations had been unresolved for less than 2 years.

More than half of the points that remained unresolved as of June 30, 2018, resulted from our review of information technology systems and the controls in place to ensure the integrity of the data they process. Roughly 80% of these points were about managing the access granted to organizations’ information technology systems, including granting access to people who do not need it. Organizations were informed of the need to correct these points to safeguard the integrity of the government’s financial data.

The remaining points raised in management letters that remained unresolved as of June 30, 2018, mainly concerned improvements to financial reporting processes and compliance with government policies, laws and regulations.

The Auditor General’s observations on the government’s 2017–2018 financial statements

Transformation of pay administration

The Transformation of Pay Administration Initiative centralized pay services for 46 departments and agencies in a new Public Service Pay Centre and included the implementation of the Phoenix pay system for all 101 departments and agencies. In 2017–2018, Phoenix processed approximately $25 billion in pay expenses. The government continued to have numerous challenges in accurately paying employees this fiscal year.

Due to these challenges, auditing pay expenses as part of the 2017–2018 annual audit of the Government of Canada’s consolidated financial statements remained labour intensive. We looked at an estimated 16,000 pay transactions across 47 of the 101 departments and agencies that used Phoenix. We found underpayments and overpayments made to employees. As a result of our testing, we estimated that the government owed employees $369 million (because the employees were underpaid) and employees owed the government $246 million (because they were overpaid). In other words, there were approximately $615 million worth of pay errors as at March 31, 2018.

We found that 62% of the employees in our sample were paid incorrectly at least once during the fiscal year (it was also 62% in the 2016–2017 fiscal year). For employees with pay errors, the number of errors for the year ranged from 1 to 19. As at March 31, 2018, 58% of the employees in our sample still required corrections to their pay—a similar percentage to the last fiscal year’s. These findings show that the situation for government employees has not improved.

Paying employees the right amount on time and resolving existing pay issues are shared responsibilities across the government. Public Services and Procurement Canada is responsible for processing payroll transactions, while the departments and agencies have an important role to play in providing timely and accurate information about changes to employee pay.

Despite the significant number of errors in individual employees’ pay, we were able to conclude that pay expenses were presented fairly in the Government of Canada’s consolidated financial statements.

Overpayments and underpayments made to employees partially offset each other. In addition, the government recorded year-end accounting adjustments to improve the accuracy of its pay expenses. These adjustments changed only the reported pay expenses in the consolidated financial statements. They didn’t correct the underlying problems, nor did they correct the pay errors that continue to affect thousands of employees.

Pay elements. The number of elements that make up an employee’s pay, each with its own set of rules and payment frequencies, contributes to the volume of errors and the complexity of processing payroll transactions. All of these pay elements are interconnected. An error in one can affect others, resulting in difficult pay calculations.

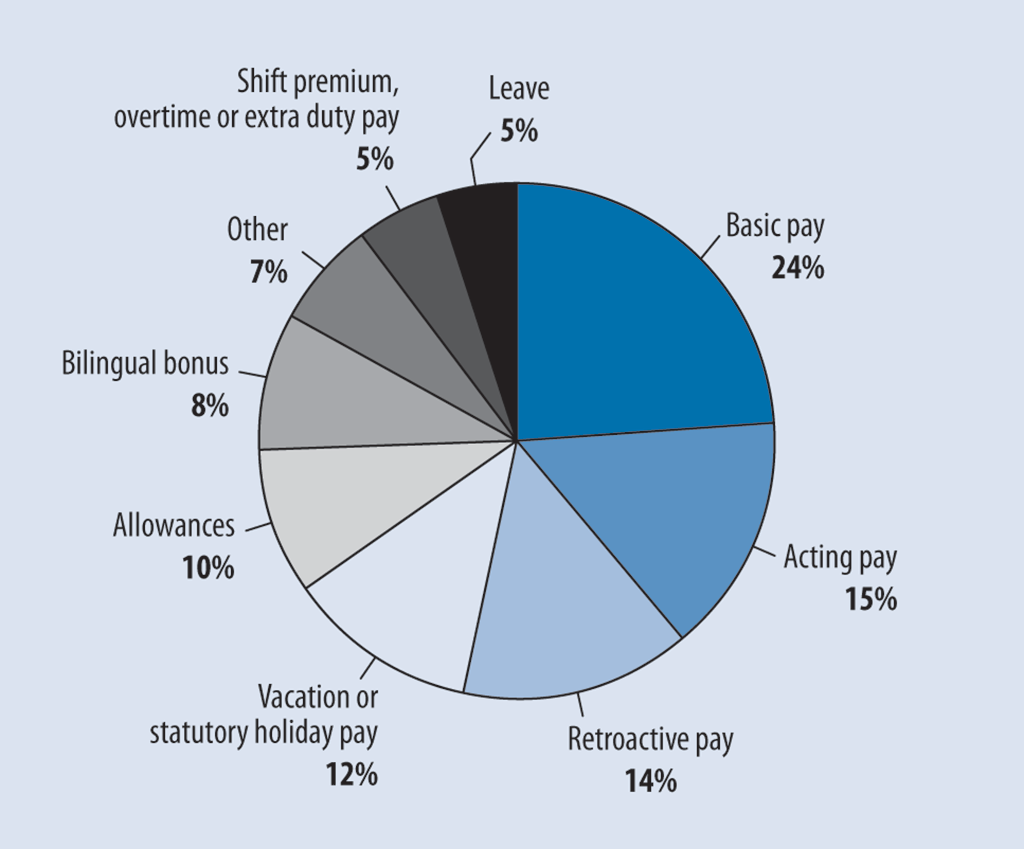

In addition to receiving basic pay (which includes items such as base salary and salary adjustments for promotions and for cost of living), an employee can receive allowances (such as for education or for living in remote locations), pay for temporarily working at a higher level (acting pay), a bonus for working in a bilingual position or premiums for working shifts. Employees working on a part-time or hourly basis have more complex pay calculations, as some of these elements are based on certain hours worked. Exhibit 2 shows the elements of employee pay for which we noted errors during our audit work.

Exhibit 2—Elements of employee pay for which we found errors in our testing

Exhibit 2—text version

This pie chart shows the elements of employee pay for which we found errors in our testing. In descending order, the percentages for these pay elements are as follows:

- 24% of errors were found in basic pay.

- 15% of errors were found in acting pay.

- 14% of errors were found in retroactive pay.

- 12% of errors were found in vacation or statutory holiday pay.

- 10% of errors were found in allowances.

- 8% of errors were found in bilingual bonuses.

- 7% of errors were found in other employee pay elements.

- 5% of errors were found in shift premium, overtime or extra duty pay.

- 5% of errors were found in leave.

Newly signed collective agreements added complexity compared with the previous year. Hundreds of thousands of retroactive payments were processed that, in some cases, applied to years as far back as 2014. These additional payments added to the workload of compensation advisors. For employees with previously uncorrected pay errors, there were greater odds that their retroactive payments would be based on an incorrect amount.

In our view, reducing the complexity of employees’ pay by combining various elements of compensation could reduce errors and the significant effort needed to accurately pay employees. Streamlining pay rules could allow the Phoenix pay system to process more transactions.

Backlog of pay action requests. The backlog of pay action requests caused delays and compounding errors in employees’ pay. Compensation advisors did not process all pay action requests on a timely basis or in an appropriate sequence, including those resulting from the renegotiation of collective agreements. We recognize that Public Services and Procurement Canada has taken some measures to try to address the errors and delays. For example, it launched the “Pay Pods” approach on a trial basis late in the 2017–2018 fiscal year. Pay Pods are groups of compensation advisors assigned to a specific department or agency who are responsible for addressing all outstanding pay action requests in an employee’s file at the same time. This is a change from addressing pay issues by transaction type. Since the Pay Pods trial only began late in the fiscal year, we could not conclude on the benefits of this new initiative.

Manual processes. Given that there are approximately 80,000 pay rules in the public service, many manual calculations and processes are needed to determine employee pay. This manual processing is largely completed by compensation advisors. The government reduced the number of experienced compensation advisors because the Transformation of Pay Administration Initiative was expected to automate many link to Financial Audit Glossarypay processes, reduce manual calculations and eliminate duplicate data entry. Over the past 2 fiscal years, many new advisors have been hired to help deal with the backlog of pay action requests. In our view, the government will need to continue employing a large number of advisors until the backlog of pay action requests and the quantity of manual processes are reduced.

Internal controls. We found weaknesses in the design of the internal controls throughout each step of the pay process and around the Phoenix system. When there are weaknesses in internal controls, there is a greater risk that errors will occur and remain undetected or uncorrected for long periods of time.

An example of a good internal control would be a sound and timely quality assurance program at the Pay Centre to review resolved pay action requests. This would enable Public Services and Procurement Canada to detect errors in processing requests for changes to employees’ pay for the 46 federal departments and agencies under its responsibility. In December 2017, we found that the Pay Centre’s quality assurance team was approximately 12 months behind in its review of resolved pay action requests. This meant the department was reviewing pay transactions and reporting on errors that were a year old—and often no longer relevant because procedures had changed in the intervening months. For a quality assurance program to be useful, it should identify current processing problems.

Training. Because of the errors we observed during the 2017–2018 financial audit and the complexities in pay calculations, we believe that additional effective training is needed to prevent and reduce the number of pay errors. This training should be timely and include public servants throughout the pay process: employees, supervisors, human resources and finance staff in departments and agencies, as well as compensation advisors in departments, agencies and at the Pay Centre.

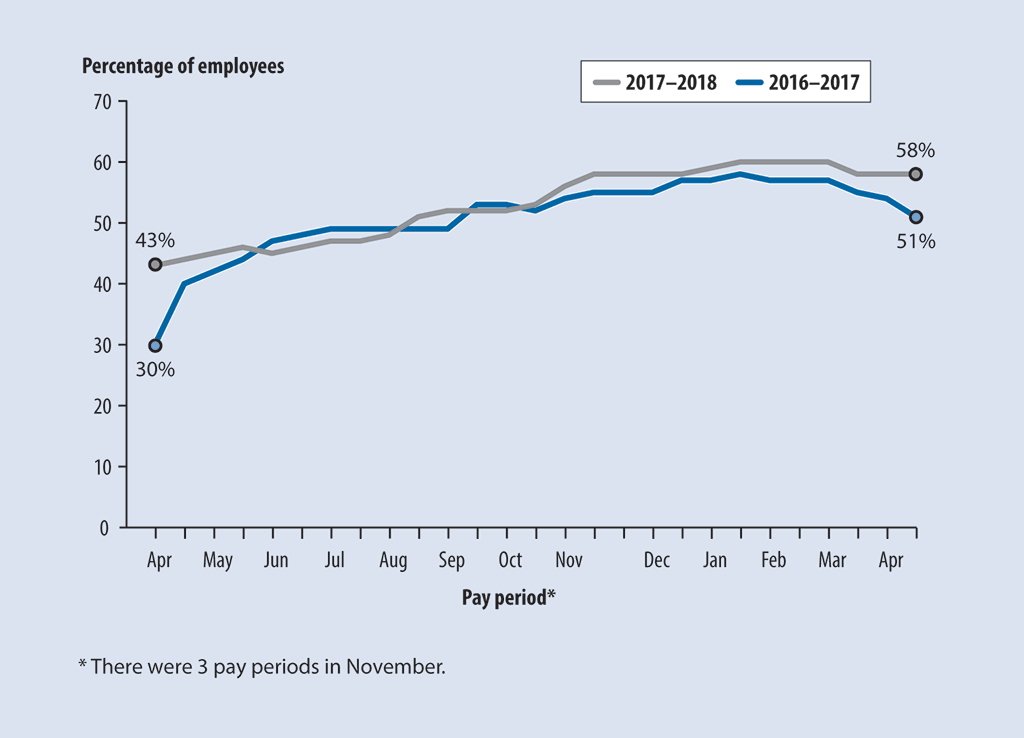

Since the Transformation of Pay Administration Initiative was implemented, pay errors have continued to increase. For the last pay period of the 2017–2018 fiscal year, the percentage of employees in our payroll sample with errors in their pay was 58% (up from 51% in the last pay period of the 2016–2017 fiscal year).

Exhibit 3 shows that for most of the pay periods in the 2017–2018 fiscal year, more than half of the employees in our sample had pay errors.

Exhibit 3—Percentage of employees in our payroll sample with errors in their paycheques by pay period

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of a sample of employees’ pay transactions used in the audit of the consolidated financial statements of the Government of Canada for the years ending March 31, 2018, and March 31, 2017

Exhibit 3—text version

This line chart shows the percentage of employees in our payroll sample with errors in their paycheques by pay period for the 2017–2018 and 2016–2017 fiscal years. The chart highlights the following data:

- For the 2017–2018 fiscal year, the percentage of employees rose from 43% in April 2017 to 58% in April 2018.

- For the 2016–2017 fiscal year, the percentage rose from 30% in April 2016 to 51% in April 2017.

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of a sample of employees’ pay transactions used in the audit of the consolidated financial statements of the Government of Canada for the years ending March 31, 2018, and March 31, 2017

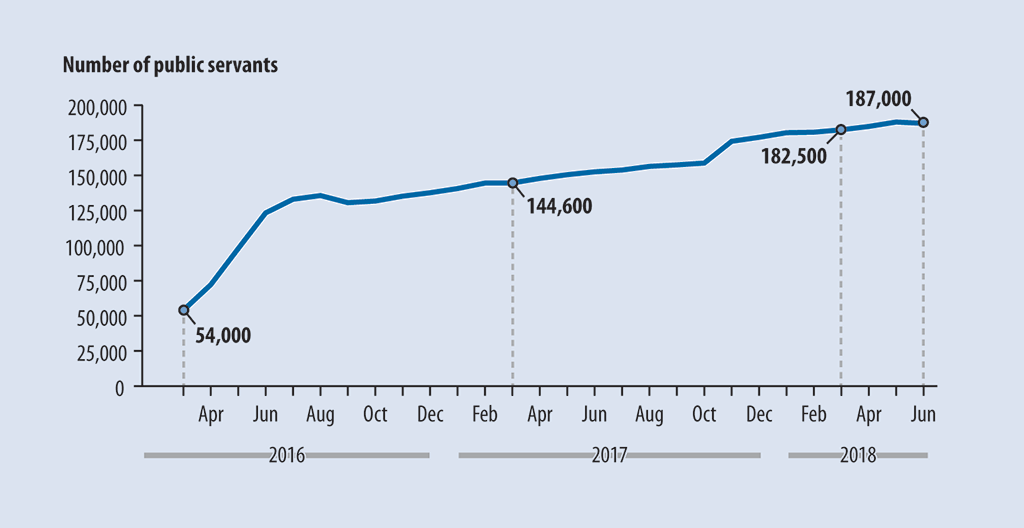

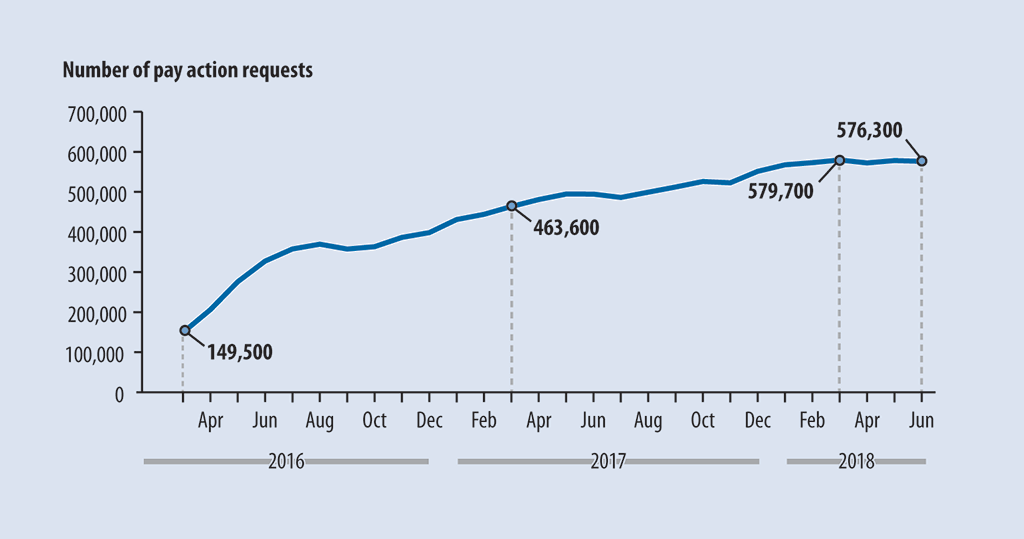

In our Phoenix Pay Problems report, we reported on the number of employees with outstanding pay action requests in the 46 departments and agencies served by the Public Service Pay Centre. As at March 31, 2017, there were 144,600 employees with 463,600 pay action requests outstanding. By March 2018, the number had grown to 182,500 employees, with almost 579,700 pay action requests.

In June 2018, 3 months after the government’s fiscal year-end, the backlog of outstanding requests was still 576,300, with 187,000 employees affected. The government continued to struggle to address the backlog.

Exhibits 4 and 5 are based on our analysis of data in Public Services and Procurement Canada’s Case Management Tool. This tool captures only the backlog for the 46 departments and agencies served by the Pay Centre. It does not include the additional pay action requests in the other departments and agencies.

Exhibit 4—Number of employees with outstanding pay action requests in the 46 departments and agencies served by the Public Service Pay Centre

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of data in Public Services and Procurement Canada’s Case Management Tool

Exhibit 4—text version

This line chart shows the number of employees from March 2016 to June 2018 with outstanding pay action requests in the 46 departments and agencies served by the Public Service Pay Centre. The chart highlights the following data:

- In March 2016, the number of public servants was 54,000.

- In March 2017, the number of public servants rose to 144,600.

- In March 2018, the number of public servants rose to 182,500.

- In June 2018, the number of public servants rose to 187,000.

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of data in Public Services and Procurement Canada’s Case Management Tool

Exhibit 5—Number of outstanding pay action requests for the 46 departments and agencies served by the Public Service Pay Centre

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of data in Public Services and Procurement Canada’s Case Management Tool

Exhibit 5—text version

This line chart shows the number of outstanding pay action requests from March 2016 to June 2018 for the 46 departments and agencies served by the Public Service Pay Centre. The chart highlights the following data:

- In March 2016, the number of outstanding pay action requests was 149,500.

- In March 2017, the number of outstanding pay action requests rose to 463,600.

- In March 2018, the number of outstanding pay action requests rose to 579,700.

- In June 2018, the number of outstanding pay action requests fell to 576,300.

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of data in Public Services and Procurement Canada’s Case Management Tool

Given the direct impact this backlog has on employees, we encourage the government to continue its initiatives to address the number of outstanding pay action requests.

Selecting discount rates for management estimates

During the 2017–2018 fiscal year, the government completed its review of the methods it uses to determine the discount rates for estimating its long-term liabilities. This review resulted in a change to the valuation of long-term liabilities in the following areas:

- public sector pension and other employee and veteran future benefits

- environment liabilities

- asset retirement obligations

- capital leases

Over the past 2 years, the Auditor General’s observations have highlighted the need for the Government of Canada to review the way it determines the discount rates used for the valuation of long-term liabilities. We raised these concerns because historically, certain discount rates had been at the high end of the acceptable range compared with market trends. A higher discount rate yields a lower estimate for long-term liabilities.

We’re satisfied that the government has addressed our recommendations from prior years.

The most significant impact resulting from the new method of selecting discount rates was on the valuation of public sector unfunded pension liabilities.

The discount rates for public sector unfunded pension liabilities are now based on market rates that reflect the government’s current cost of borrowing. Previously, the government used discount rates that reflected historical and expected long-term link to Financial Audit Glossarybond rates. The new rates are consistent with industry practice and comply with the Canadian public sector accounting standards. The result is that these liabilities more accurately reflect the value in today’s dollars of what it would cost the government to settle them in the future.

The government decreased the discount rate used to value the unfunded pension liabilities for 2016–2017 to 2.2% from 3.7%. This resulted in an increase of $19.6 billion in the government’s public sector pension liabilities. While this change affected the values of the public sector pension liabilities and the accumulated deficit in the consolidated financial statements, it does not affect the way the government plans to meet its future obligations or payments to pensioners.

In accordance with the Canadian public sector accounting standards, the government retroactively restated the 2016–2017 balances in its consolidated financial statements. In other words, it adjusted the balances from last year’s statements to reflect the values that would have been shown if the revised discount rates had always been applied. This makes it possible to compare the current year’s results with the previous year’s results. In addition, the government estimated the impact of the change in discount rates on the 10-year comparative financial information included in its link to Financial Audit Glossaryfinancial statements discussion and analysis, found in Section 1 of Volume 1 of the Public Accounts of Canada. The 10-year information, which is unaudited, has also been restated.

The change in discount rates and the resulting impacts on balances reported in the previous year are further explained in Note 2 to the Government of Canada’s consolidated financial statements, also found in Volume 1 of the Public Accounts of Canada. More information about the government’s pension plans can be found in Note 9.

National Defence inventory

National Defence’s inventory is a significant item in the consolidated financial statements of the Government of Canada. It accounted for $5.7 billion of the government’s $6.7 billion total inventory as at March 31, 2018. It is divided into 2 subgroups:

- ammunition, valued at $3.3 billion as at March 31, 2018

- non-ammunition, or “consumables,” valued at $2.4 billion as at March 31, 2018

Consumables are generally high-volume, low-value items, such as clothing, fuel and medical supplies.

Inventory is recorded as an asset. When an item is removed from inventory, an expense is recognized, either because the item will be used or is no longer usable.

In addition to its inventory, National Defence has items such as major spare parts to repair or maintain fleets, equipment and machinery. These items are recorded as tangible capital assets. These assets are managed like inventory, so it can be difficult to distinguish them from inventory. However, the distinction is important, because these 2 types of assets aren’t treated the same way for accounting purposes.

During our 2017–2018 audit of the consolidated financial statements of the Government of Canada, we selected a sample of National Defence’s inventory items and examined them to determine whether the department:

- recorded the right quantity (quantity)

- applied the right price to determine their value (pricing)

- removed obsolete items from inventory or adjusted their value to reflect their obsolescence (obsolescence)

- classified items properly as either inventory or tangible capital assets (classification)

Quantity. In 2017–2018, National Defence increased the number of cyclical inventory counts on a subset of high-risk items based on their nature and value. The quantity errors we found in ammunition were insignificant; however, we found quantity errors for consumables estimated at approximately $217 million. In our view, errors occurred because counts on a subset of inventory may not identify all quantity discrepancies. To improve the accuracy of its inventory, the department has several initiatives in its long-term action plan, such as the implementation of an automatic identification technology system expected to begin in 2022–2023.

Pricing and obsolescence—ammunition. In the current fiscal year, the department focused its attention on monitoring activities for the pricing of ammunition stock codes. The department also recorded an allowance for ammunition obsolescence. We found no significant errors in ammunition.

Pricing and obsolescence—consumables. National Defence reviewed and corrected the pricing for certain high-risk consumables in 2017–2018. We found pricing errors worth approximately $82 million in consumables that the department hadn’t reviewed. We also found obsolescence errors estimated at approximately $117 million. The department recorded an allowance of $95 million that partially offsets these 2 errors.

Classification. In the current fiscal year, National Defence continued its review of how it classifies items between inventory and tangible capital assets. As a result of our audit work, we found classification errors estimated at approximately $93 million for items recorded as inventory instead of capital assets.

The department has more work to do to ensure its underlying inventory records are accurate and its inventory is properly valued and recorded in the consolidated financial statements of the Government of Canada.

In 2016–2017, National Defence provided the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts with a long-term action plan extending to 2026–2027 to address challenges in properly recording and valuing its inventory.

On May 30, 2018, the department reported to the committee that it substantially met the commitments in its action plan for the 2017–2018 fiscal year. The following are some of the key results National Defence reported:

- It had analyzed and corrected the prices of approximately 70,000 high-risk consumable stock codes. The remaining consumable stock codes are expected to be addressed in next year’s action plan.

- It had monitored (and adjusted, if necessary) ammunition pricing, which it analyzed and corrected last year.

- It had completed more test counts and quality assurance procedures over certain inventory items than it had originally committed to.

- It had disposed of certain obsolete items that had been previously written off in the consolidated financial statements.

We reviewed documentation and are pleased with the department’s actions taken to meet its 2017–2018 commitments in its multi-year action plan.

We expect further progress in the next fiscal years as the department accomplishes commitments set out in the plan. We encourage National Defence to continue its efforts to complete actions it identified as necessary to improve its inventory management practices.

Additional insights from our financial audits

The Government of Canada’s financial statements discussion and analysis

The federal government’s financial statements discussion and analysis (FSDA) is a tool meant to make financial information easier to understand.

As part of our audit of the government’s consolidated financial statements, we review the FSDA to ensure it is consistent with the information that we audit. This allows us to identify opportunities to improve the FSDA’s usefulness.

In our last 2 annual commentaries, we encouraged the government to review its FSDA against best practices to improve the FSDA’s usefulness. Although the government made improvements in 2017 and 2018, the FSDA could be further enhanced to help parliamentarians understand information in the consolidated financial statements and financial management. For example, discussing the strategies and techniques used to manage the risks discussed in the FSDA would be useful to users. In addition, there are still opportunities to improve certain sections of the FSDA. For example, the capital asset section could be expanded to help users assess how and when capital assets need to be renewed or replaced and whether sufficient funding will be available to meet these needs and ensure the sustainability of program and service delivery.

Significant projects with information technology components

Looking beyond Phoenix and the government’s transformation of pay administration, our audits have made us aware of more than 30 significant projects with information technology (IT) components—planned or under way—that affect financial reporting at various federal organizations, including Crown corporations. These projects are significant because they involve systems that are undergoing major conversion or replacement as well as changes to IT management in some organizations. Examples include the following:

- Employment and Social Development Canada is responsible for the Canada Student Loans Program, which provides loans and grants to eligible students to help them access and afford post-secondary education. The program also administers loans and grants to students on behalf of some provinces. Its new IT system, which is being developed by a third party, will manage the Canada Student Loans Program across the entire lending lifecycle. The new system is being launched in phases. It started in 2018, and additional features will be available for students in 2019. The full implementation schedule is yet to be determined.

- The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation is undergoing a technology and business transformation that is expected to improve its agility and efficiency as well as the effectiveness of its infrastructure, processes and controls. As part of this transformation, the corporation partnered with a third party to provide ongoing IT services and execute the transformation projects. Its portfolio of planned technology and business transformation projects is well under way and should be completed by 2019.

- The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat is responsible for implementing a new government-wide human resource (HR) system called My Government of Canada Human Resources (MyGCHR), which started in 2009. This system contains employee data and interfaces with the Phoenix pay system. The project’s original objective was to transition 98 departments and agencies from their existing HR applications to a common system. Currently, 44 are using MyGCHR. The Secretariat told us that the transition is delayed due to a reallocation of resources to support the stabilization of Phoenix and work under way to explore a next-generation HR and pay system.

- The Canada Revenue Agency has a multi-year project under way to significantly modify the systems for processing individual tax returns and to explore opportunities for additional business transformation. This project, known as the T1 Systems Redesign, began in the 2013–2014 fiscal year and is being implemented in phases. It is expected to be completed in the 2019–2020 fiscal year.

Federal organizations rely on IT systems to deliver services to Canadians, process financial transactions and prepare financial reports. The integrity of these systems is critical to organizations’ ability to deliver programs successfully and to the credibility of the financial reports they base decisions on and present to Parliament.

The risks and challenges involved in these projects depend on their type and complexity. Risks can take the form of data integrity issues, system functions not working as intended, unforeseen impacts on other systems, challenges in maintaining program delivery during projects, inappropriate changes to internal controls or issues with change management, including training of employees or end users.

If federal organizations do a poor job of managing the risks and challenges inherent in significant and complex projects with IT components, the result could be more failures like Phoenix. To properly manage these risks and challenges, there are some commonly used practices (Exhibit 6).

Exhibit 6—Example of commonly used practices in the governance and management of information technology projects

Governance

- Senior management and the governance body should receive timely and accurate information and provide an appropriate level of oversight.

- There should be an independent review of the project’s progress and state of readiness, which should be shared with the oversight body to inform decision making.

- Ownership and accountability should rest with appropriate senior management. Appropriate controls should be in place to minimize risk.

- Responsibility should be appropriately assigned for project requirements. Key stakeholders should be involved at each stage of the project.

Business case

Before seeking project approval, the organization should prepare a business case that includes precise and measurable objectives, a full analysis of options, costs and risks, as well as an implementation plan.

Organizational capacity

- Before starting a project, the organization should ensure it has the capability and commitment to properly manage and successfully complete the project.

- The project should include a complete contingency plan.

Project management

- The organization should comply with relevant legislative and policy requirements, including available project management guidance. It should closely manage the project risks and monitor key success factors.

- The organization should report regularly to senior management and the governance body any significant event that may prevent the expected project benefits or result in cost overruns or in the project not being delivered on time.

- The project should include plans for keeping the software current throughout the project timetable.

- The information technology programs should be fully tested before being implemented.

- The organization should consult stakeholders and ensure they actively participate in the project’s design and testing.

The following are some questions that parliamentarians could ask of federal organizations planning and undertaking significant and complex projects with IT components to ensure they anticipate possible issues and address the issues proactively:

- How is the organization ensuring that accountability for project outcomes is clear and transparent?

- How is the organization monitoring whether expected outcomes will be achieved on time and on budget?

- How does the organization plan to test data integrity and system functionalities prior to conversion?

- What criteria will it use to assess whether a new system is ready to go live?

Parliamentary approval of government spending

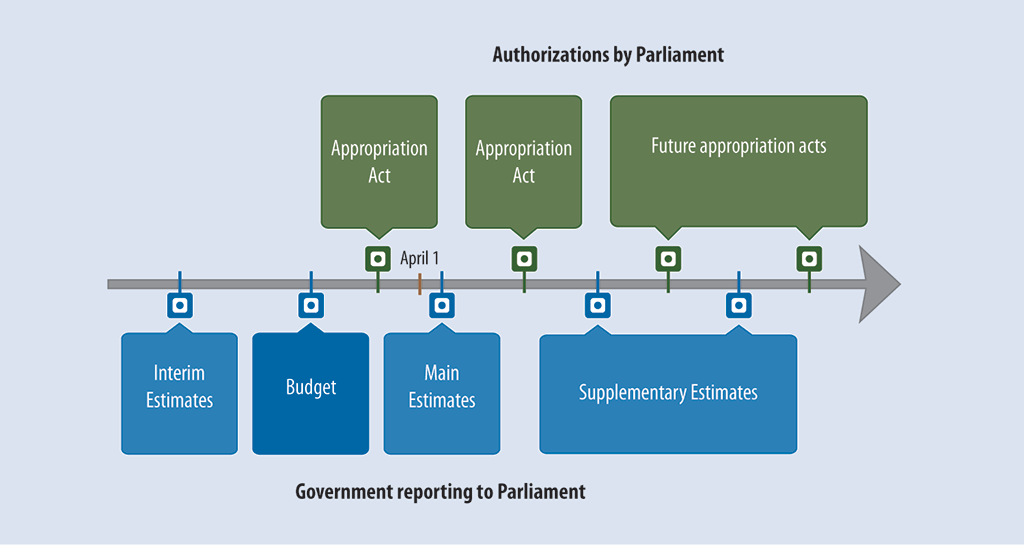

It is critical that Parliament is given complete, precise and consistent information about government spending to oversee whether taxpayers’ dollars serve Canadians’ interests. Granting government the authority to spend is one of Parliament’s principal responsibilities.

Planning, reporting and authorizing government expenditures is a complex process that involves a series of steps over an annual cycle (Exhibit 7). This process can be hard to follow and understand.

- Before the start of the fiscal year, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat submits link to Financial Audit GlossaryInterim Estimates to Parliament to request authorization for the government to spend funds for the first 3 months of the fiscal year until the link to Financial Audit GlossaryMain Estimates are approved. Parliament authorizes this spending through an link to Financial Audit Glossaryappropriation act.

- Also usually before the start of the fiscal year, the Minister of Finance presents the federal link to Financial Audit GlossaryBudget to Parliament for the upcoming fiscal year. The Budget forecasts what the government proposes to spend and the revenue it expects to collect. The Budget is a plan; it does not authorize government spending.

- The President of the Treasury Board tables the Main Estimates in Parliament no later than April 16. This document sets out the detailed projected expenditures of federal organizations for the fiscal year, including the amounts already shown in the Interim Estimates. The Main Estimates include 2 types of expenditures:

- Voted expenditures. These are expenditures that Parliament must authorize annually. The authority for voted expenditures applies to a specific fiscal year.

- Statutory expenditures. These are expenditures that are already authorized under other legislation. They’re presented in the Main Estimates for information purposes only. The authority for these expenditures is provided when the legislation is initially approved.

Parliament authorizes the voted expenditures through an appropriation act. This act excludes the statutory expenditures because they have already been approved through existing legislation.

- At other intervals through the year, the government submits link to Financial Audit GlossarySupplementary Estimates to Parliament to seek approval for any additional expenditures not included in the Main Estimates through additional appropriation acts.

Exhibit 7—The reporting and authorization cycle for government expenditures

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s interpretation of the House of Commons Compendium of Procedure

Exhibit 7—text version

This illustration shows the annual reporting and authorization cycle for government expenditures.

Three steps are shown before April 1:

- Interim Estimates (government reporting to Parliament)

- Budget (government reporting to Parliament)

- Appropriation Act (authorization by Parliament)

Four steps are shown after April 1:

- Main Estimates (government reporting to Parliament)

- Appropriation Act (authorization by Parliament)

- Supplementary Estimates (government reporting to Parliament)

- Future appropriation acts (authorization by Parliament)

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s interpretation of the House of Commons Compendium of Procedure

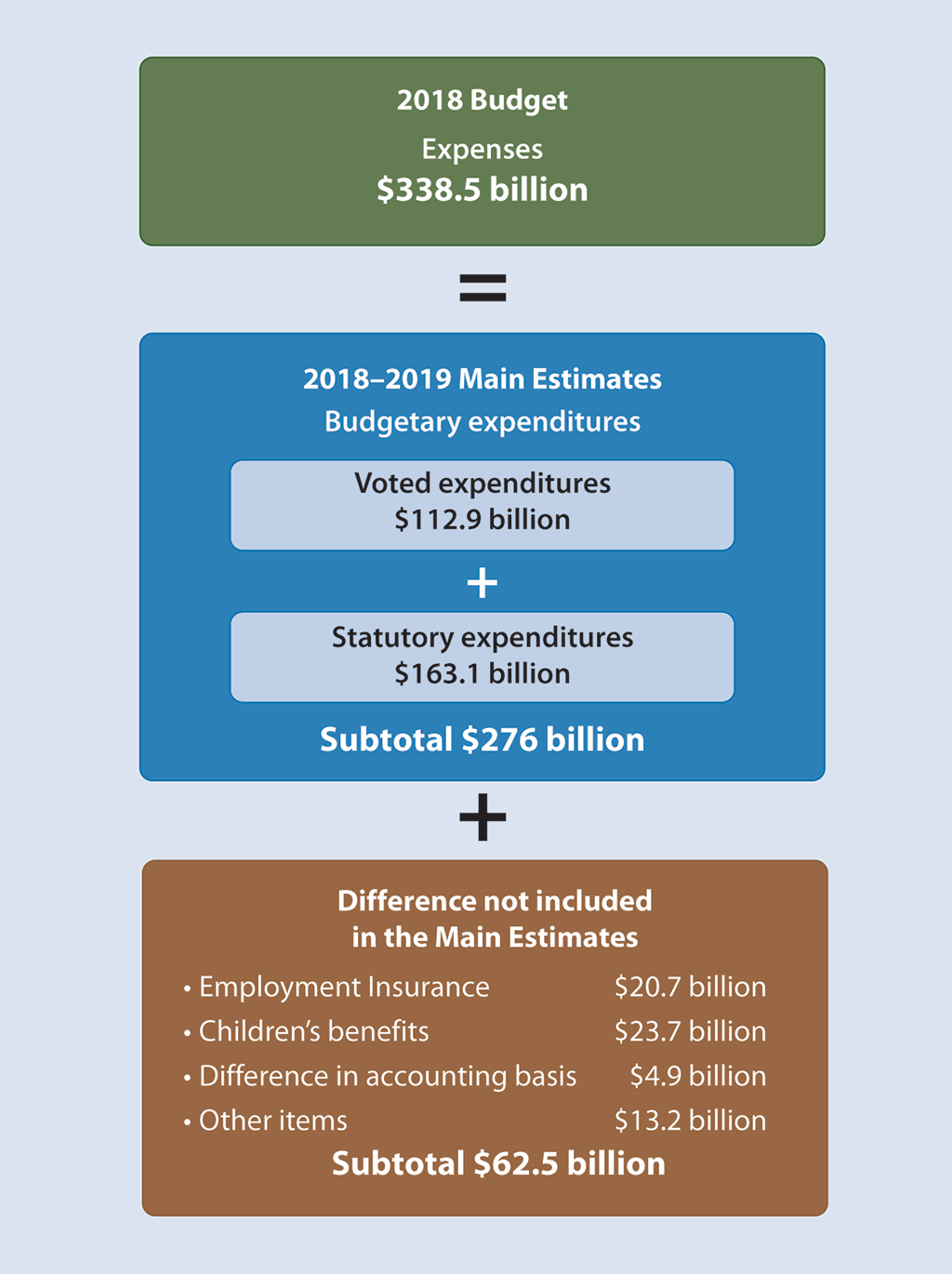

After the submission of the 2018–2019 Main Estimates, Parliament debated and voted on annual expenditures of $112.9 billion, which represented one third of total spending presented in the 2018 Budget (Exhibit 8).

Exhibit 8—Components of government spending

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of the 2018–2019 Main Estimates publication

Exhibit 8—text version

This illustration shows the components of government spending. The 2018 Budget forecasts expenses totalling $338.5 billion for the 2018–2019 fiscal year. The breakdown of this total is as follows:

- $276 billion of budgetary expenditures set out in the 2018–2019 Main Estimates, which is the sum of $112.9 billion of voted expenditures and $163.1 billion of statutory expenditures

- $62.5 billion of expenditures not included in the Main Estimates, which is the sum of $20.7 billion for Employment Insurance, $23.7 billion for children’s benefits, $4.9 billion for the difference in accounting basis, and $13.2 billion for other items.

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of the 2018–2019 Main Estimates publication

The other two thirds of total government spending, mainly consisting of statutory expenditures, wasn’t subject to Parliament’s review through the Main Estimates process. We agree with the recommendations made in the June 2012 report of the Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates on Strengthening Parliamentary Scrutiny of Estimates and Supply, that standing committees provide a challenge function by reviewing statutory programs cyclically to assess their ongoing relevance. Regular and systematic review of statutory expenditures would enhance parliamentary oversight by providing an opportunity to determine whether the intended objectives are being met.

The Main Estimates list hundreds of statutory expenditures for each federal organization. Exhibit 9 summarizes the main categories.

Exhibit 9—Statutory expenditures reported in the 2018–2019 Main Estimates

| Expenditures | $ billions | Percentage of total expenditures |

|---|---|---|

| Payments to provinces and territories | 72.6 | 45% |

| Payments to elderly individuals | 53.7 | 33% |

| Interest on government debts | 22.8 | 14% |

| Contributions to employee benefit plans or other salary-related amounts | 5.7 | 3% |

| Other statutory items | 8.3 | 5% |

| Total | 163.1 | 100% |

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of the 2018–2019 Main Estimates publication (statutory forecasts)

While the Main Estimates present statutory expenditures for information purposes, this document is key to helping parliamentarians scrutinize them during the planning process.

For example, identifying the legislation that supports an expenditure as statutory is useful information for parliamentarians when analyzing the expenditure.

Every year, there is a difference of several billion dollars between the amounts in the Budget and those in the Main Estimates. Parliamentarians need to understand the nature of these amounts because they aren’t subject to annual parliamentary approval through appropriation acts.

In the 2018 Budget, the government forecasted total expenses of $338.5 billion for the 2018–2019 fiscal year. The 2018–2019 Main Estimates set out expenditures of $276 billion, which was $62.5 billion less than the amount provided for in the 2018 Budget (Exhibit 8).

The $62.5 billion difference between the amounts in the Main Estimates and the Budget is largely because the Main Estimates don’t include Employment Insurance benefits ($20.7 billion) and children’s benefits ($23.7 billion). The expenditures for both programs are statutory since they were previously authorized by their enabling legislation. It isn’t clear why the government isn’t treating them as such.

We’ll continue discussions with the government to identify opportunities to improve the information in the Main Estimates and to help parliamentarians understand and scrutinize all of the government’s spending plans.

The following are questions that parliamentarians could ask the government to clarify the information presented in the Main Estimates:

- What processes are available or could be implemented to allow more regular reviews of statutory expenditures?

- Why are Employment Insurance benefits and children’s benefits, which are already authorized by legislation, not reflected in the Main Estimates as statutory expenditures?

- What criteria or basis are used to decide what expenditure qualifies as statutory?

- In addition to recent changes the government made to the annual Estimates process, are there ways to improve parliamentary oversight of government spending?

About our financial statement audits

To find out more about the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s work on the government’s financial statements, see the “Financial Audit” section on our website.