2018 Fall Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada Independent Auditor’s ReportReport 6—Community Supervision—Correctional Service Canada

2018 Fall Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of CanadaReport 6—Community Supervision—Correctional Service Canada

Independent Auditor’s Report

Introduction

Background

6.1 Correctional Service Canada (CSC) is the federal government agency that administers adult offenders’ sentences of two years or more, as imposed by the courts. Under the Corrections and Conditional Release Act, most offenders become eligible for release before their sentences end. As a result, nearly all serve a portion of their sentences under supervision in the community.

6.2 CSC manages federal correctional institutions, parole offices, and community correctional centres. Its responsibilities include supervising all offenders under various forms of community release. Public safety is influenced by how well CSC supports the safe transition and successful reintegration of offenders into society.

6.3 The Parole Board of Canada is independent of CSC. Its responsibilities include deciding whether to conditionally release offenders. The Board may also impose special conditions on the release of an offender that it deems necessary to protect society or to facilitate an offender’s successful return to society.

6.4 As of April 2018, approximately 9,100 federal offenders—or almost 40% of all federal offenders—were supervised in the community. The number of offenders in the community increased by 17% between the 2013–14 and 2017–18 fiscal years. During this same period, the overall offender population remained stable. The number of offenders in the community is expected to keep rising.

6.5 In the 2017–18 fiscal year, CSC spent $160 million, or 6% of its overall spending, on the community supervision program. The program provides housing, health services, and staff supervision to offenders to help them reintegrate safely into the community.

Focus of the audit

6.6 This audit focused on whether Correctional Service Canada adequately supervised offenders in the community, and accommodated them when required, to support their return to society as law-abiding citizens.

6.7 This audit is important because offenders’ gradual and supervised return to society leads to better public safety outcomes. Correctional Service Canada’s responsibilities include helping to rehabilitate offenders and reintegrate them into the community as law-abiding citizens.

6.8 We did not examine Correctional Service Canada’s activities for offenders on long-term supervision orders that were conducted after the offenders’ sentences ended. In addition, we did not audit the Parole Board of Canada’s activities.

6.9 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Overall message

6.10 The number of offenders released into community supervision had grown and was expected to keep growing. However, Correctional Service Canada had reached the limit of how many offenders it could house in the community. As a result, offenders approved for release into the community had to wait twice as long for accommodation. Despite the growing backlog, and despite research that showed that a gradual supervised release gave offenders a better chance of successful reintegration, Correctional Service Canada did not have a long-term plan to respond to its housing pressures.

6.11 It could take more than two years from the time a site was selected with a community partner to the time the first offender was placed at a new facility. Given that Correctional Service Canada was already at capacity, this meant that the housing shortages were likely to get worse.

6.12 Our audit also found that Correctional Service Canada did not properly manage offenders under community supervision. For example, it did not give parole officers all the information they needed to help offenders with their health needs, and parole officers did not always meet with offenders as often as they should have.

6.13 This meant that Correctional Service Canada could not find places in a timely manner for many offenders who should have been released into community supervision, and it did not properly monitor many offenders under community supervision.

Accommodation in the community

6.14 In March 2018, nearly one third of the federal offenders on release (2,800 of 9,100 offenders) required supervised housing as a condition of their release. This number included offenders on day paroleDefinition i, full paroleDefinition ii with a residency condition, statutory releaseDefinition iii with a residency condition, or a long-term supervision orderDefinition iv with a residency condition. A residency condition is imposed when the Parole Board of Canada considers it reasonable and necessary to manage an offender’s risk to the community. In exceptional circumstances, offenders who pose a threat of serious harm or violence may be held in custody until the date their sentences end, also known as warrant expiry. Exhibit 6.1 shows the timeline of an offender’s eligibility for release from a correctional institution.

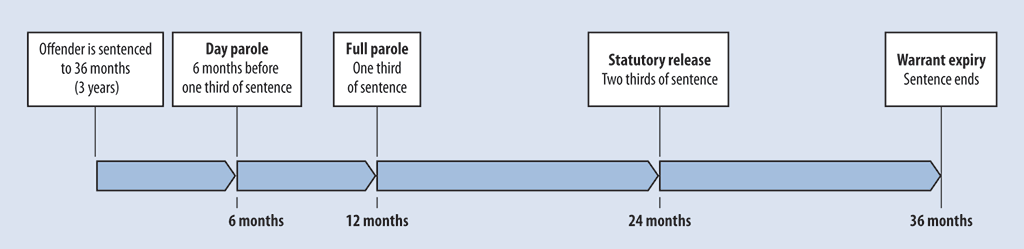

Exhibit 6.1—Offenders can be eligible for different types of release throughout their sentences

Note: A three-year sentence is shown in the timeline as an example.

Source: Based on the Corrections and Conditional Release Act

Exhibit 6.1—text version

This graphic shows a timeline of when offenders are eligible for different types of release during a three-year sentence.

At the start of the timeline, the offender is sentenced to 36 months (or 3 years).

At 6 months before one third of their sentence, offenders are eligible for day parole. Day parole is a conditional release that allows offenders to participate in community activities, with a nightly return to a residential facility.

At 12 months or one third of their sentence, offenders are eligible for full parole. Full parole is a conditional release that allows offenders to serve the remainder of their sentences in locations of their choice in the community.

At 24 months or two thirds of their sentence, offenders are eligible for statutory release. Statutory release is a release required by law. Most offenders, except those serving a life or indeterminate sentence, must be released with supervision after serving two thirds of their sentences, if parole was not already granted.

At 36 months, the warrant expires and the offender’s sentence ends. In exceptional circumstances, offenders who pose a threat of serious harm or violence may be held in custody until warrant expiry, when their sentences end.

Note: A three-year sentence is shown in the timeline as an example.

Source: Based on the Corrections and Conditional Release Act

6.15 There are two types of community-based residential facilities for offenders:

- Community residential facilities are owned by non-governmental agencies and provide special housing, counselling, and supervision to offenders.

- Community correctional centres are operated by Correctional Service Canada. They are designed for offenders on release who need a high degree of structure or who have complex needs.

6.16 Suitable residency space is not always immediately available. In such cases, offenders approved for conditional release by the Parole Board of Canada may wait for space that suits their needs, risk, and desired location to become available, or may agree to be released to a facility in a different location. Either situation impedes their progress toward reintegration.

Correctional Service Canada had no long-term plan to address growing accommodation pressures

6.17 We found that although Correctional Service Canada (CSC) was at capacity at many community-based residential facilities and had forecasted an increase of offenders requiring these facilities, CSC had no long-term plan to meet that demand.

6.18 We found that during our audit period, CSC held lower-risk offenders with higher reintegration potential longer in correctional institutions because the community-based residential facilities could not accommodate them. We noted that overall wait times for housing increased substantially from the 2014–15 fiscal year to the 2017–18 fiscal year. In our view, this prolonged wait might negatively affect offenders’ successful reintegration.

6.19 We also found that capacity constraints caused some offenders with residency requirements to receive housing in locations other than their requested communities. Such situations also impeded offenders’ successful reintegration.

6.20 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

- Available housing for offenders

- Wait times for housing in the community

- Data to measure offender displacement

- Plans to meet demand for housing

6.21 This finding matters because CSC is mandated to release offenders as soon as possible after parole is granted. Research indicates that when offenders spend more time in the community under supervision, and are located close to positive support structures, such as family and employment, they have a better chance of a successful return to society.

6.22 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 6.38.

6.23 What we examined. We examined Correctional Service Canada’s

- population of offenders accommodated in the community,

- forecast for the community offender population,

- current capacity to house offenders in the community, and

- wait times for offenders ready to be placed in community accommodation after meeting release requirements.

6.24 Available housing for offenders. We found that the number of offenders requiring community-based residential facilities rose by 21% over the five-year period from the 2013–14 fiscal year to the 2017–18 fiscal year.

6.25 We also found that Correctional Service Canada (CSC) did not increase the number of housing spaces to keep pace with demand. As a result, the proportion of community-based residential facilities in use generally increased over the five fiscal years from 2013–14 to 2017–18, although the increase was greater in some communities than others. In January 2017, CSC released its internal National Strategic Review. The report observed that spaces for male offenders in community residential facilities were at 85% capacity, with some geographic areas at full or almost full capacity. This meant that when approached to accept an offender, a community residential facility might not have had room to accommodate them.

6.26 CSC’s community correctional centres received offenders with more complex needs and offenders that community residential facilities refused. We found that by March 2018, CSC’s community correctional centres operated at 88% capacity.

6.27 We noted that it is unrealistic to expect full use of community-based residential facilities. Here are some examples of why CSC had difficulty placing offenders in appropriate accommodation:

- Available housing in the requested location did not always match an offender’s specific needs (such as those related to mental health, substance abuse, and mobility or accessibility issues).

- Community residential facilities did not always guarantee that all of their housing was available to offenders.

- Community residential facilities could refuse to accept offenders who did not meet the agreed-upon eligibility criteria (for example, criteria based on the type of offence committed).

6.28 In our view, this meant that CSC was running out of the space it needed to effectively accommodate offenders in the community.

6.29 Wait times for housing in the community. We found that Correctional Service Canada (CSC) did not know the amount of time that offenders had to wait in correctional institutions for available housing in the community. This is important because knowledge of wait times helps in assessing whether there is sufficient capacity to accommodate offenders in the community.

6.30 Offenders released at their statutory release date with a residency condition are prioritized for housing, because CSC is obliged by law to provide them with a placement in the community by their release dates. This means that lower-risk offenders who are granted day parole and have a higher chance of successfully reintegrating as law-abiding citizens are the group most affected by the lack of housing available in the community.

6.31 We found that the average wait time for a day parole offender to be released into the community in the 2014–15 fiscal year was 13 days, with a range of 0 to 105 days. In the 2017–18 fiscal year, the average wait time increased to 24 days, with a range of 0 to 264 days. Furthermore, we found that over the same period, the number of offenders who waited more than two months went from 29 to 257. In our view, CSC had increasing difficulty in meeting the demand for community housing, which may have negatively affected offenders’ successful reintegration as law-abiding citizens.

6.32 Data to measure offender displacement. We found that Correctional Service Canada (CSC) did not maintain data on how many offenders were not placed in their requested communities. CSC did not record the reasons offenders were not placed in their requested communities—such as the lack of capacity, the lack of a space that met an offender’s specific needs, or an offender’s agreeing to be released in a different community rather than wait in a correctional institution. Furthermore, CSC did not maintain data on the types of specialized housing that offenders needed in the community-based residential facilities. This meant that CSC did not have the information it needed to fully understand accommodation pressures, or to prioritize facilities for future expansion according to need.

6.33 Although the data did not exist to assess the number of offenders displaced to other communities, we found that CSC-operated community correctional centres were distributed unevenly across the country. This likely resulted in offenders with complex needs being released to locations far from their requested communities and from the supports they needed for reintegration.

6.34 For example, Ontario had two community correctional centres at the time of our audit: Toronto and Kingston. CSC officials told us that 80% of offenders housed in the Kingston community correctional centre had requested the Greater Toronto Area—260 kilometres away—as their preferred release location. This meant that they were not close to the supports they needed, such as family or employment, to ensure a successful reintegration into society.

6.35 Plans to meet demand for housing. Correctional Service Canada (CSC) periodically reviews its population forecast. In 2017, CSC prepared a new forecast for the next 10 years. It forecasted that within this period, the number of offenders requiring community-based residential facilities would increase by another 13% across Canada. While this projected growth rate was slower overall than the growth that occurred in recent years, some regions were expected to increase significantly more. The greatest anticipated increase was in Ontario, at 32%. CSC officials told us that it can sometimes take more than two years from site selection with a community partner to the time the first offender is placed at a new facility. Given that CSC was in effect operating at capacity at the time of our audit, the forecast meant that housing shortages were likely to worsen.

6.36 CSC did not forecast needs by significant population centres or for specialized housing. These needs included those of aging offenders with mobility issues, offenders with substance abuse issues, and offenders with mental illness. As a result, CSC did not have the tools to proactively prepare for capacity pressures in the community.

6.37 CSC had some success at adding housing in response to existing capacity pressures. CSC achieved these increases by working with community partners to add housing where available. We found, however, that in increasing housing spaces, CSC did not plan beyond 6 to 12 months. Despite capacity pressures, growing demand, and lengthening wait times, CSC did not take a proactive, long-term approach to address its housing shortages.

6.38 Recommendation. Correctional Service Canada should take a proactive, long-term approach to accommodation in community-based residential facilities. It should ensure that its accommodation space is of the right type, in the right location, and available at the right time.

The Agency’s response. Agreed. In order to establish a long-term plan for the management of community accommodation, Correctional Service Canada (CSC) will build on the community capacity analysis that was completed as part of its 2017 internal strategic review (National Strategic Review, January 2017), as well as its ongoing regional analyses. This will provide an integrated, national, long-term approach that will be responsive to operational needs in each region, including the capacity to meet the projected growth and population profile. CSC has also initiated the development of a comprehensive solution for both bed-inventory management and the matching of offenders to community facilities, including wait-lists.

Supervision of offenders

Correctional Service Canada did not always conduct timely and complete supervision of offenders as required

6.39 We found that parole officers at Correctional Service Canada (CSC) did not always meet with offenders as often as needed to manage their risk to society. We also found that parole officers did not always monitor offenders’ compliance with special conditions imposed by the Parole Board of Canada.

6.40 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topic:

6.41 This finding matters because CSC requires parole officers to regularly assess offenders’ progress against their release plans and to identify any changes to their risks and needs. The assessments allow parole officers to adjust the interventions outlined in the plans, as needed, to support offenders’ successful return to society and to manage any risk to public safety.

6.42 CSC advises the Parole Board of Canada whether an offender’s risk can be managed in the community. CSC also develops an offender’s release plan and may recommend special conditions, such as a residency requirement, to the Parole Board of Canada. CSC sets the minimum required frequency of contact between an offender in the community and a parole officer. The frequency is based on the offender’s specific reintegration needs and risk of reoffending. This contact is CSC’s key supervision activity because it involves meeting face to face with the offender, which provides information and lets the parole officer plan or validate other monitoring activities.

6.43 CSC’s community correctional results indicate that the first year after release is when offenders are most likely to reoffend or breach a condition of their release.

6.44 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 6.49.

6.45 What we examined. Using representative sampling, we examined the case management files of 50 offenders to review the parole officers’ monitoring activities for the first year after the offenders were released to the community.

6.46 Monitoring offenders. We found that parole officers did not always meet with offenders in accordance with Correctional Service Canada’s (CSC) standards for supervising offenders in the community. We also found instances in which parole officers met with offenders in a compressed amount of time (for example, three times in six days). This approach did not allow parole officers to perform timely assessments of any changes to the risks offenders posed to society. In addition, parole officers did not always monitor compliance with special conditions imposed by the Parole Board of Canada.

6.47 For 19 of the 50 offender files examined (nearly 40%), we found that parole officers did not fully monitor offenders as required. For the 19 offenders, there were

- 14 cases in which parole officers did not meet offenders for the minimum frequency required;

- 9 cases in which parole officers met with offenders on several occasions over a short time period, which was not in keeping with the spirit of the policy; and

- 3 cases in which parole officers did not monitor compliance with special conditions imposed by the Parole Board of Canada.

6.48 Some cases showed more than one monitoring deficiency. These deficiencies meant that during our sample period, these offenders were not properly supervised for about one quarter of the time they were in the community. In its 2010 internal audit of community supervision, CSC noted similar deficiencies in the contact between parole officers and offenders.

6.49 Recommendation. Correctional Service Canada should ensure that parole officers monitor offenders at least as often as its standards require and monitor the special conditions imposed by the Parole Board of Canada.

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada (CSC) will reinforce the need for compliance with the existing policy requirements related to the frequency of contact and the monitoring of offenders’ special conditions. Additionally, CSC will strengthen compliance monitoring through its existing corporate reporting system. CSC will also reinforce the need for, and monitoring of, documentation to be completed in cases in which exceptions are warranted to the frequency of contact requirements.

Correctional Service Canada did not facilitate offenders’ access to health care as required

6.50 We found that Correctional Service Canada (CSC) did not ensure offenders’ continued access to health care when they transitioned to the community. Often, CSC did not

- provide all required health-related information to the parole officers responsible for preparing offender release plans, or

- ensure that offenders had provincial health insurance cards before their release to the community.

6.51 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

6.52 This finding matters because CSC is responsible for offenders’ continued access to essential health care when they transition to the community. CSC has additional responsibilities when health conditions affect the risk of an offender’s reoffending or the risk to public safety. This includes monitoring health-related special conditions imposed by the Parole Board of Canada.

6.53 CSC must facilitate offenders’ continued access to health care as they transition from a correctional institution to the community.

6.54 Offenders need health cards to access medical services and medications in the community. CSC does not pay for offenders to renew or replace health cards.

6.55 For exceptional circumstances in which a public safety interest is identified, CSC has committed to providing essential health services to address gaps or delays in provincial health service coverage.

6.56 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 6.61 and 6.64.

6.57 What we examined. We used representative sampling to examine 50 case management files to determine whether Correctional Service Canada made relevant health information available to the parole officers responsible for developing the offenders’ release plans. We also looked at whether those offenders had health cards when they were released to the community.

6.58 Sharing health information within Correctional Service Canada. To develop an offender’s release plan, Correctional Service Canada (CSC) is required to share health information in a timely manner with the parole officer responsible for the offender, and to document that it has done so.

6.59 We found that in almost all of the 50 cases in our sample, the release plan included some health information. However, we found evidence in only 5 cases (10%) that CSC provided the parole officer with all of the offender’s required health care information. We found only 1 case in which CSC shared health information four months in advance of an offender’s hearing for release, as CSC’s policy requires.

6.60 This meant that parole officers developed release plans without being fully aware of offenders’ health care needs. It also meant that parole officers likely did not have the information they needed to adequately supervise and provide support to offenders on their release to the community.

6.61 Recommendation. Correctional Service Canada should ensure that it shares all relevant health care information with the parole officers responsible for preparing the release plan and for monitoring progress against that plan, and that it does so in a timely manner.

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada (CSC) agrees with the importance of sharing risk-relevant health information. CSC will conduct a review of its policies regarding the sharing of health information and determine an approach that will be most effective at ensuring that parole officers receive the information they require in a timely manner.

6.62 Health cards. We found that Correctional Service Canada (CSC) often released offenders without a health card. In its 2012 internal audit of the release process, CSC found the same issue, as did the Correctional Investigator of Canada in a 2014 investigation of federal community correctional centres.

6.63 More than one third of the offenders in our sample (18 of 50) did not have health cards at release. For 6 of these offenders, provincial rules did not allow health cards to be issued until the offenders left the correctional institution. However, in our view, CSC did not meet its responsibility to ensure continued access to health services when it released the other 12 offenders without health cards.

6.64 Recommendation. Correctional Service Canada should assist offenders in obtaining health cards before they are released to the community. In provinces or territories where health cards cannot be obtained by persons who are incarcerated, Correctional Service Canada should work with offenders to obtain health cards once they are released.

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada (CSC) will continue to assist offenders in obtaining personal identification (ID) prior to release, including their health card. CSC has engaged with provincial and territorial partners for their support in establishing a process at all remand centres that would ensure that the available ID is transferred with the offender when they are admitted to CSC custody.

Upon release, CSC policy requires that parole officers validate existing ID and assist the offender in applying for other ID as required. CSC will continue to work collaboratively with various stakeholders to prepare offenders for their release with the proper ID.

In addition, CSC will work to improve collaboration with provincial and territorial health authorities with the objective of removing barriers to accessing health care cards.

Measurement of results

6.65 Correctional Service Canada (CSC) compiles performance measurement data on its community supervision program and reports the results both internally and externally.

6.66 CSC’s responsibility includes supervising offenders to assist in their rehabilitation and reintegration into the community as law-abiding citizens. As a result, the reconviction rate is a key measure for assessing CSC’s performance.

Correctional Service Canada did not include all relevant convictions when calculating post-sentence results

6.67 We found that when Correctional Service Canada (CSC) calculated post-sentence outcomes, it included only the convictions that resulted in a return to federal custody. CSC did not include data on the convictions recorded by other levels of government. This meant that CSC had an incomplete picture of the rate at which federal offenders were successfully reintegrating into society as law-abiding citizens.

6.68 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topic:

6.69 This finding matters because without knowing its success rate in rehabilitating offenders as law-abiding citizens, Correctional Service Canada cannot fully assess how well it is meeting its mandate, nor can it make adjustments to address problem areas.

6.70 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 6.77.

6.71 What we examined. We examined Correctional Service Canada’s external and internal performance measures related to community supervision.

6.72 Measuring reconvictions. Correctional Service Canada (CSC) publicly reported several performance measures for its community supervision program. However, we found that few of them measured CSC’s success against its mandate to successfully reintegrate offenders into society as law-abiding citizens.

6.73 CSC reports information on offenders who have completed their sentences and returned to federal custody. We found that on its social media channels, CSC occasionally reported on the percentage of offenders who returned to federal custody within five years of completing their sentences. These social media posts stated that the rate of offenders returning to federal custody had fallen. When reporting to Parliament, CSC reported only on the percentage of offenders who received mental health treatment and returned to federal custody within two years of completing their sentences. This particular group of offenders represented only about 40% of the offender population. As a result, CSC’s reporting to Parliament did not account for the total offender population.

6.74 We also found that CSC’s performance measures did not include data on offences requiring incarceration in provincial or territorial facilities. CSC officials informed us that such data on convictions was excluded because it was difficult to gather. However, we noted that information about convictions was available to the public.

6.75 In 2003, Public Safety Canada sought to understand the rate of reconviction of federal offenders and carried out a study that included reconvictions with provincial and territorial sentences. It recognized that the federal government’s responsibility to rehabilitate offenders as law-abiding citizens included all criminal behaviour, even crimes that did not result in a return to federal custody. Using this more complete measure, Public Safety Canada found that about one quarter of federal offenders reoffended within a short period after they completed their sentences.

6.76 Other countries reported more complete data related to offender reconviction rates. We noted that corrections agencies in the United Kingdom and the United States were required to report reoffending rates in their annual performance reports. These figures were to include offences from multiple jurisdictions. In addition, both countries were to report events other than reconvictions, such as arrests.

6.77 Recommendation. Correctional Service Canada should broaden its measures of the successful reintegration of federal offenders as law-abiding citizens after they complete their sentences to better reflect its mandate.

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada (CSC) uses various performance indicators to measure the safe and successful reintegration of offenders into the community, including community program participation and completion, employment, and successful completion of sentence without federal readmission. To broaden its measures of successful reintegration, CSC will collaborate with Public Safety Canada on the work it has initiated in the area of recidivism rates, including information held by provinces and territories on adult reconvictions.

Conclusion

6.78 We concluded that Correctional Service Canada did not provide enough community housing to offenders in the right locations, nor did it properly supervise offenders in the community to ensure their successful reintegration as law-abiding citizens.

6.79 In our view, Correctional Service Canada needs to do more. This includes providing parole officers with the health information they need to effectively support offenders in the community and supervising offenders more consistently upon release. Correctional Service Canada must also plan more strategically to ensure that it has the types of community housing it needs, where it needs them and when it needs them.

6.80 Finally, in measuring its success, Correctional Service Canada needs a more complete picture of whether it is effectively supporting federal offenders’ successful return to the community.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on the community supervision of offenders under the authority of Correctional Service Canada. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs, and to conclude on whether Correctional Service Canada complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard for Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office applies Canadian Standard on Quality Control 1 and, accordingly, maintains a comprehensive system of quality control, including documented policies and procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we have complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit;

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit;

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided; and

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate.

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether Correctional Service Canada supervised offenders and provided accommodation in the community to support their return to society as law-abiding citizens.

Scope and approach

The audit examined whether Correctional Service Canada (CSC) had sufficient capacity to meet the needs of offenders, whether it monitored and addressed the risks and needs of offenders through applicable case management processes, and whether it measured and reported on results for continuous improvement.

We examined the year-over-year pattern for offenders with a residency requirement who were released on their first term (an offender’s first release to the community while serving a sentence) during the 2011–12 to 2017–18 fiscal years. We calculated wait times for offenders who were not released as soon as they were granted parole. We also looked at the year-over-year pattern with regard to the availability of CSC-funded accommodations.

We used representative sampling to examine 50 case management files for offenders released for the first time on either conditional or statutory release during the 2015–16 fiscal year. We followed the offenders’ progress in the community by reviewing case records for up to one year after their release to assess whether they received planned interventions and whether CSC’s policies and guidelines were followed. The sample was sufficient in size to conclude on the sampled population with a confidence level of 90% and a margin of error of +10%.

We examined CSC’s performance information from the 2014–15 to 2017–18 fiscal years to determine whether it provided a complete picture of CSC’s effectiveness in supporting offenders’ return to society.

Criteria

To determine whether Correctional Service Canada (CSC) supervised offenders and provided accommodation in the community to support their return to society as law-abiding citizens, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

CSC has sufficient capacity to meet the accommodation needs of the offenders in the community. |

|

|

CSC defines its future accommodation needs for the community offender population and has a plan to meet those needs. |

|

|

CSC monitors and addresses the risks and needs of offenders through applicable case management processes in the community. |

|

|

CSC measures and reports on the public safety results achieved by its community supervision program, and it uses the information to adjust the program. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period between 1 April 2015 and 31 March 2018. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies. However, to gain a more complete understanding of the subject matter of the audit, we also examined certain matters that preceded the starting date of this period.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 24 August 2018, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

Principal: Nicholas Swales

Director: Steven Mariani

Donna Ardelean

Nicholas Brouwer

Meaghan Burnham

Johanna Lazore

Jenna Lindley

Stuart Smith

List of Recommendations

The following table lists the recommendations and responses found in this report. The paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report, and the numbers in parentheses indicate the location of the related discussion.

Accommodation in the community

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

6.38 Correctional Service Canada should take a proactive, long-term approach to accommodation in community-based residential facilities. It should ensure that its accommodation space is of the right type, in the right location, and available at the right time. (6.17 to 6.37) |

The Agency’s response. Agreed. In order to establish a long-term plan for the management of community accommodation, Correctional Service Canada (CSC) will build on the community capacity analysis that was completed as part of its 2017 internal strategic review (National Strategic Review, January 2017), as well as its ongoing regional analyses. This will provide an integrated, national, long-term approach that will be responsive to operational needs in each region, including the capacity to meet the projected growth and population profile. CSC has also initiated the development of a comprehensive solution for both bed-inventory management and the matching of offenders to community facilities, including wait-lists. |

Supervision of offenders

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

6.49 Correctional Service Canada should ensure that parole officers monitor offenders at least as often as its standards require and monitor the special conditions imposed by the Parole Board of Canada. (6.39 to 6.48) |

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada (CSC) will reinforce the need for compliance with the existing policy requirements related to the frequency of contact and the monitoring of offenders’ special conditions. Additionally, CSC will strengthen compliance monitoring through its existing corporate reporting system. CSC will also reinforce the need for, and monitoring of, documentation to be completed in cases in which exceptions are warranted to the frequency of contact requirements. |

|

6.61 Correctional Service Canada should ensure that it shares all relevant health care information with the parole officers responsible for preparing the release plan and for monitoring progress against that plan, and that it does so in a timely manner. (6.50 to 6.60) |

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada (CSC) agrees with the importance of sharing risk-relevant health information. CSC will conduct a review of its policies regarding the sharing of health information and determine an approach that will be most effective at ensuring that parole officers receive the information they require in a timely manner. |

|

6.64 Correctional Service Canada should assist offenders in obtaining health cards before they are released to the community. In provinces or territories where health cards cannot be obtained by persons who are incarcerated, Correctional Service Canada should work with offenders to obtain health cards once they are released. (6.62 to 6.63) |

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada (CSC) will continue to assist offenders in obtaining personal identification (ID) prior to release, including their health card. CSC has engaged with provincial and territorial partners for their support in establishing a process at all remand centres that would ensure that the available ID is transferred with the offender when they are admitted to CSC custody. Upon release, CSC policy requires that parole officers validate existing ID and assist the offender in applying for other ID as required. CSC will continue to work collaboratively with various stakeholders to prepare offenders for their release with the proper ID. In addition, CSC will work to improve collaboration with provincial and territorial health authorities with the objective of removing barriers to accessing health care cards. |

Measurement of results

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

6.77 Correctional Service Canada should broaden its measures of the successful reintegration of federal offenders as law-abiding citizens after they complete their sentences to better reflect its mandate. (6.67 to 6.76) |

The Agency’s response. Agreed. Correctional Service Canada (CSC) uses various performance indicators to measure the safe and successful reintegration of offenders into the community, including community program participation and completion, employment, and successful completion of sentence without federal readmission. To broaden its measures of successful reintegration, CSC will collaborate with Public Safety Canada on the work it has initiated in the area of recidivism rates, including information held by provinces and territories on adult reconvictions. |