2022 Reports 9 and 10 of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada

Report 10—Specific COVID-19 Benefits

At a Glance

With its response to the COVID‑19 pandemic, the Government of Canada set an objective of helping Canadians as quickly as possible. The COVID‑19 emergency programs that we audited achieved that objective. They quickly offered financial relief to individuals and employers, prevented a rise in poverty, mitigated income inequalities, and helped the economy to recover from the effects of the pandemic.

To expedite issuing payments, the Canada Revenue Agency and Employment and Social Development Canada relied on personal attestations. They decided early on to focus less on confirming the eligibility of applicants up front and more on reviewing eligibility after payments were issued and recovering overpayments or payments made to ineligible recipients. The risk that some recipients might not be eligible for benefits they received made verifying eligibility after payment all the more important.

We found that the department and agency’s approach to limit pre-payment controls, as well as the lack of timely data at the time of application, resulted in a significant amount of payments made to recipients who were ineligible or whose eligibility needs to be verified. We found $4.6 billion of overpayments made to ineligible recipients of benefits for individuals. In addition, we estimated that at least $27.4 billion of payments to individuals and employers should be investigated further. A more definitive estimate of payments made to ineligible recipients and amounts to be recovered by the government will be determined only after the agency and the department have completed their post-payment verifications.

The department and agency did not develop rigorous and comprehensive plans to verify the eligibility of recipients. We found that their post‑payment verification plans did not include verifying payments made to all identified recipients at risk of being ineligible for all COVID‑19 benefit programs. Given the limited pre‑payment controls and the early decision to focus on post‑payment verifications, we expected the department and the agency to perform extensive post‑payment verifications to identify payments made to ineligible recipients.

There have also been delays in conducting post‑payment verifications and the collection of amounts owing has just started. The department and agency are at risk of not completing all planned post‑payment verifications within the applicable timelines. This means they may be unable to identify and recover amounts owing. According to the information provided by the department and agency, they have recuperated approximately $2.3 billion.

Why we did this audit

- It is important that the government demonstrates that the COVID‑19 benefit programs supported Canadians and employers in need.

- The benefit programs to individuals and employers were significant emergency measures that, in order to issue payments within days of receiving an application, relied upon the good faith of Canadians and Canadian employers.

Our findings

- COVID‑19 programs supported Canada’s economic recovery.

- Employment and Social Development Canada adjusted benefit programs to try to address disincentives to work.

- The trade‑off between expediency and confirming eligibility resulted in payments to ineligible recipients.

- Employment and Social Development Canada and the Canada Revenue Agency were planning to do few post‑payment verifications.

- The Canada Revenue Agency performed limited collection activities on COVID‑19 programs.

Key facts and figures

- We found that the government made $4.6 billion of overpayments to ineligible recipients. We also estimated that at least $27.4 billion was paid to recipients that should be investigated further through post‑payment verification to confirm eligibility.

- For most of the COVID‑19 benefit programs, the timeline to collect an amount owed has been established in legislation at 6 years from the date the notice is issued to the recipient of the amount owed or when the debt became payable.

- For benefits to individuals, approximately $2.3 billion of COVID‑19 benefit overpayments had been repaid by recipients.

Highlights of our recommendations

- In order to improve its efficiency of delivering benefit programs, the Canada Revenue Agency, with the collaboration of Employment and Social Development Canada, should pursue the development and implementation of a real‑time payroll system with clear timelines and deliverables.

- To increase the recovery of COVID‑19 amounts owed and reduce the administrative burden, the Canada Revenue Agency should, before the end of December 2022, put system functionalities in place to apply refunds against COVID‑19 amounts owed.

Please see the full report to read our complete findings, analysis, recommendations and the audited organizations’ responses.

According to Statistics Canada, from 2019 to 2020, the median income of combined employment, pensions, and investments for Canadians declined by $1,600. However, the median government transfers doubled from $8,200 to $16,400. This was due mainly to COVID‑19 income support programs. Overall, these increases in government transfers to households exceeded losses in wages and salaries and self‑employment income. This income compensation through the COVID‑19 programs helped to financially support the population.

These findings are aligned with the government’s targets regarding 2 United Nations’ sustainable development goals—Goal 1, No Poverty, and Goal 10, Reduced Inequalities. Thus, we found that the COVID‑19 benefits under audit for individuals contributed to reducing poverty and inequalities in Canada in 2020.

Visit our Sustainable Development page to learn more about sustainable development and the Office of the Auditor General of CanadaOAG.

Exhibit highlights

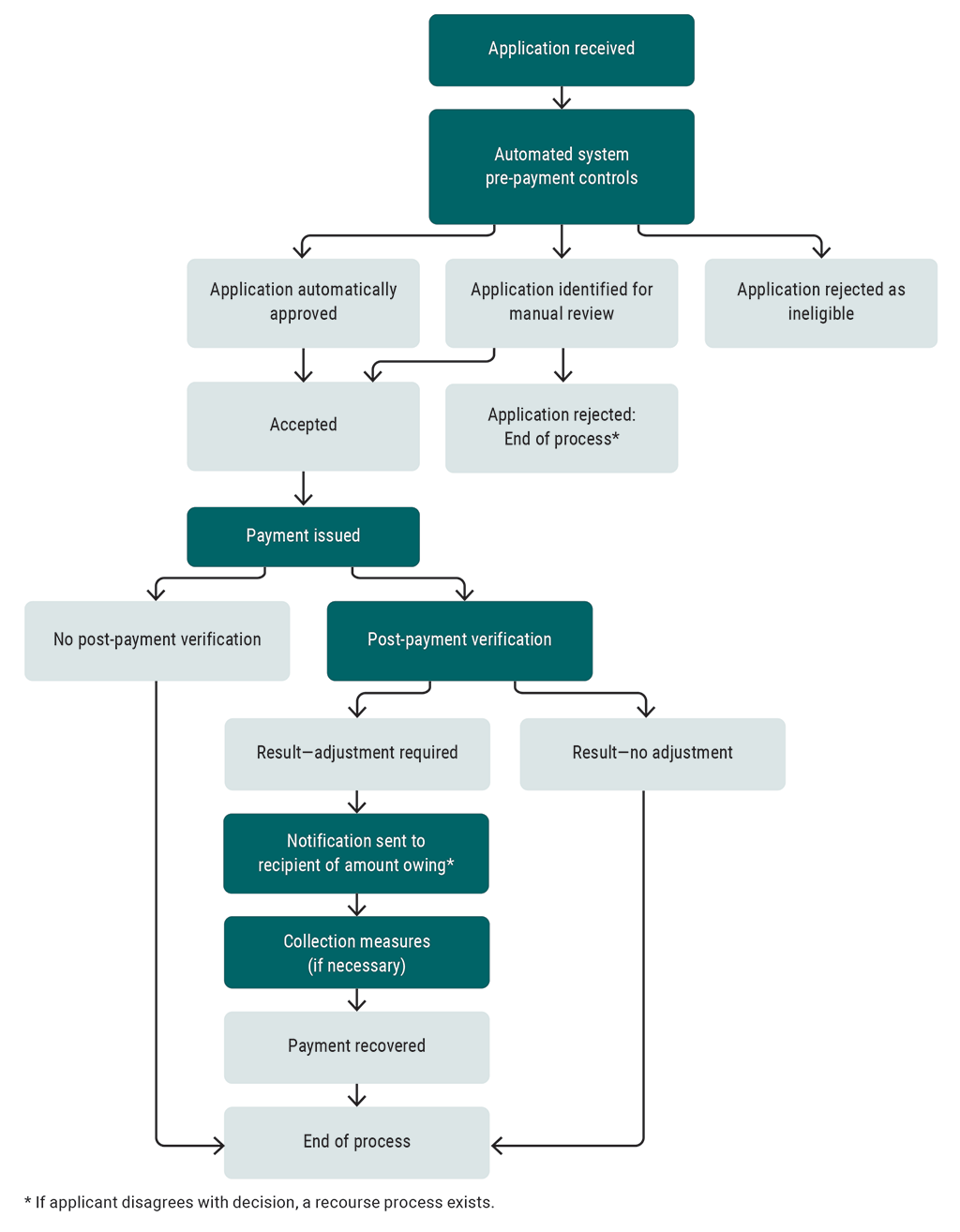

Simplified COVID‑19 benefit application process for individuals and employers

Text version

This flowchart shows a simplified version of the COVID‑19 benefit application process for individuals and employers.

The application is received.

An automated system performs pre-payment controls.

The application can be

- automatically approved

- identified for manual review

- rejected as ineligible

If the application is automatically approved, it is accepted, after which a payment is issued.

If, after the manual review, the application is accepted, a payment is issued.

If, after the manual review, the application is rejected, the application process ends. If the applicant disagrees with the decision, a recourse process exists.

If the application is rejected as ineligible, the application process ends.

For the applications that are accepted and payments issued, some applications undergo post-payment verification and some do not.

If an application does not undergo post-payment verification, the process ends.

If an application undergoes post-payment verification, the result could be no adjustment, and the process ends.

But, for some applications, an adjustment is required. In this case, a notification is sent to the recipient stating the amount owing. If the recipient disagrees with the decision, a recourse process exists.

Collection measures are taken if necessary.

When the payment has been recovered, the process ends.

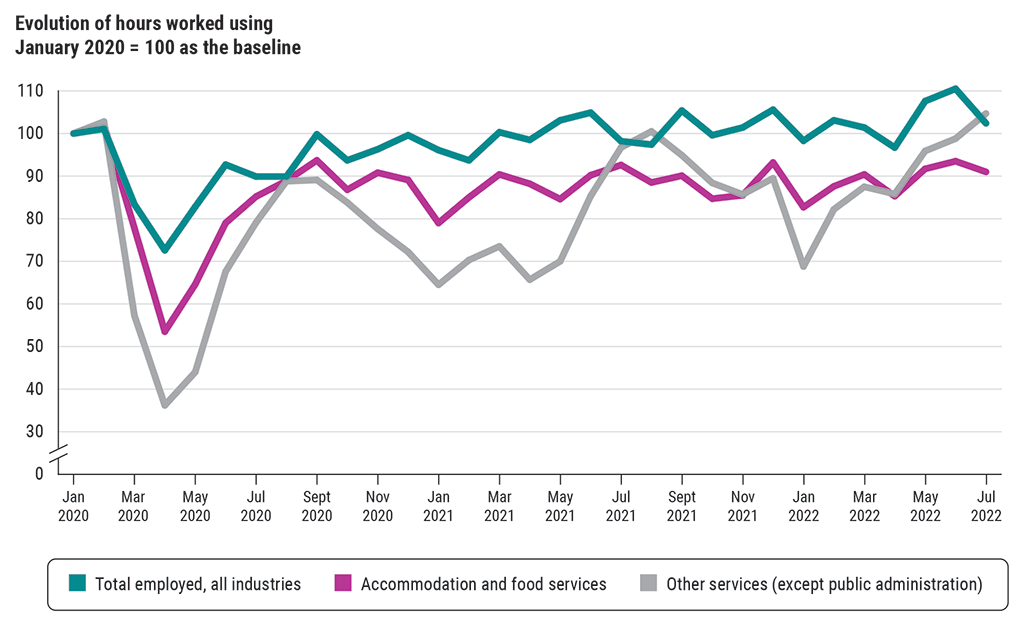

After a major decrease between February and April 2020, the number of hours worked went back to pre‑COVID‑19 level as of May 2021, with some service industries still affected

Note: We used Statistics Canada data and established an index number (January 2020 = 100, which is a statistical technique for measuring changes in the magnitude of a group of related variables) to measure the change from a point in time. “Other services” include activities not classified to any other sector, such as personal care services, funeral services, and car repair and maintenance. For a complete definition, see Statistics Canada.

Source: Statistics Canada

Text version

This graph shows the changes in the number of hours worked from January 2020 to July 2022 in 3 categories of industries. After a decline in March and April 2020, the hours worked returned to pre-pandemic levels, with the exception of some service industries.

The chart shows the following 3 categories of industries:

- total employed for all industries

- accommodation and food services

- other services (except public administration)—“Other services” include activities not classified in any other sector, such as personal care services, funeral services, and car repair and maintenance. For a complete definition, see Statistics Canada.

To determine the evolution of hours worked, we established an index number, which was January 2020 equals 100. This index number was the baseline used to measure changes from that point in time. Using an index number is a statistical technique for measuring changes in the magnitude of a group of related variables. We used Statistics Canada data.

Following are the number of hours worked in all industries from January 2020 to July 2022:

- In January 2020, the number of hours worked was 100.0.

- In March 2020, the number of hours worked was 83.4.

- In May 2020, the number of hours worked was 82.8.

- In July 2020, the number of hours worked was 89.9.

- In September 2020, the number of hours worked was 99.8.

- In November 2020, the number of hours worked was 96.3.

- In January 2021, the number of hours worked was 96.1.

- In March 2021, the number of hours worked was 100.3.

- In May 2021, the number of hours worked was 103.1.

- In July 2021, the number of hours worked was 98.2.

- In September 2021, the number of hours worked was 105.4.

- In November 2021, the number of hours worked was 101.4.

- In January 2022, the number of hours worked was 98.3.

- In March 2022, the number of hours worked was 101.4.

- In May 2022, the number of hours worked was 107.6.

- In July 2022, the number of hours worked was 102.4.

Following are the number of hours worked in accommodation and food services from January 2020 to July 2022:

- In January 2020, the number of hours worked was 100.0.

- In March 2020, the number of hours worked was 57.3.

- In May 2020, the number of hours worked was 44.0.

- In July 2020, the number of hours worked was 79.1.

- In September 2020, the number of hours worked was 89.1.

- In November 2020, the number of hours worked was 77.6.

- In January 2021, the number of hours worked was 64.5.

- In March 2021, the number of hours worked was 73.5.

- In May 2021, the number of hours worked was 70.0.

- In July 2021, the number of hours worked was 96.7.

- In September 2021, the number of hours worked was 94.9.

- In November 2021, the number of hours worked was 85.7.

- In January 2022, the number of hours worked was 68.8.

- In March 2022, the number of hours worked was 87.5.

- In May 2022, the number of hours worked was 95.9.

- In July 2022, the number of hours worked was 104.7.

Following are the number of hours worked in other services (except public administration) from January 2020 to July 2022:

- In January 2020, the number of hours worked was 100.0.

- In March 2020, the number of hours worked was 77.8.

- In May 2020, the number of hours worked was 64.6.

- In July 2020, the number of hours worked was 85.2.

- In September 2020, the number of hours worked was 93.7.

- In November 2020, the number of hours worked was 90.8.

- In January 2021, the number of hours worked was 79.0.

- In March 2021, the number of hours worked was 90.4.

- In May 2021, the number of hours worked was 84.6.

- In July 2021, the number of hours worked was 92.6.

- In September 2021, the number of hours worked was 90.1.

- In November 2021, the number of hours worked was 85.5.

- In January 2022, the number of hours worked was 82.7

- In March 2022, the number of hours worked was 90.4.

- In May 2022, the number of hours worked was 91.7.

- In July 2022, the number of hours worked was 91.0.

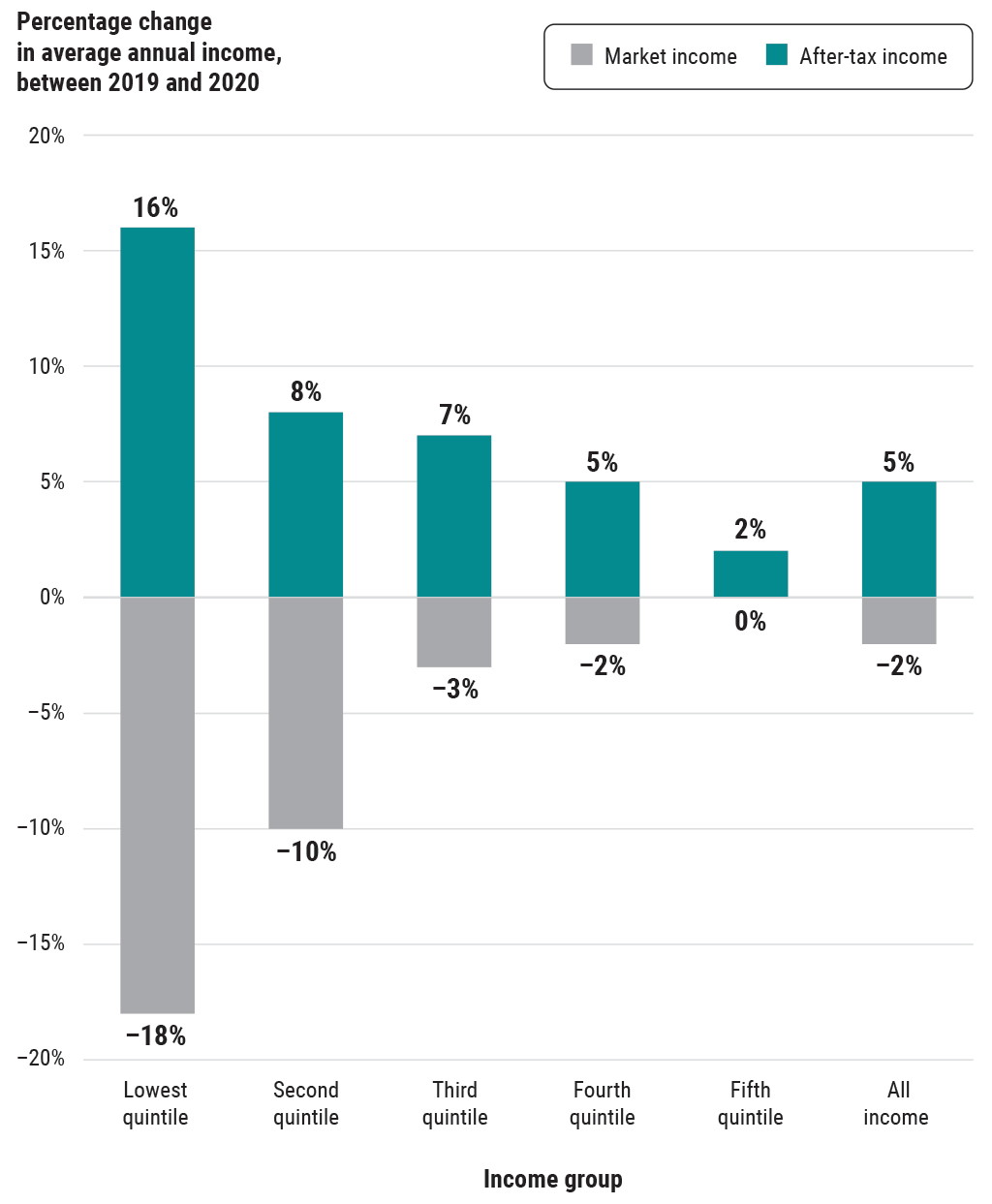

Annual after‑tax income increased among the lowest‑income earners between 2019 and 2020 due to government payments for COVID‑19 benefits

Note: An income quintile is a measure that divides the population into 5 income groups (from lowest income to highest income) so that approximately 20% of the population is in each group. Market income is employment income and private pensions plus income from investments and other market sources. After‑tax income is the total of market income and government payments, less income tax. For 2020, government transfers included emergency response and recovery benefits.

The exhibit above illustrates that people in the lowest quintile were those who had the highest decrease in their market income. It also illustrates that COVID‑19 benefits represented a higher proportion of the total after‑tax income for the people in the lowest quintile.

Source: Statistics Canada

Text version

This bar chart shows the percentage of change in average annual income for different income groups between 2019 and 2020. The percentage of change was greatest in the group with the lowest average annual incomes—as annual incomes increased, the percentage of change decreased.

The chart shows the percentage of change for both market income and after-tax income. Market income is employment income and private pensions plus income from investments and other market sources. After-tax income is the total of market income and government payments, less income tax. For 2020, government transfers included emergency response and recovery benefits. Although after-tax income increased for all income groups, it increased the most for the lowest-income group. Also, the lowest-income group had the greatest decrease in market income.

The 6 income groups consist of 5 income quintiles and the sixth income group shows all income. An income quintile is a measure that divides the population into 5 income groups (from lowest income to highest income), so that approximately 20% of the population is in each group.

Following are the percentages of change in average annual income for each income quintile between 2019 and 2020:

- For the lowest quintile, the average annual after-tax income increased by 16% and the average annual market income decreased by 18%.

- For the second quintile, the average annual after-tax income increased by 8% and the average annual market income decreased by 10%.

- For the third quintile, the average annual after-tax income increased by 7% and the average annual market income decreased by 3%.

- For the fourth quintile, the average annual after-tax income increased by 5% and the average annual market income decreased by 2%.

- For the fifth quintile, the average annual after-tax income increased by 2% and the average annual market income decreased by 0%.

- For all income, the average annual after-tax income increased by 5% and the average annual market income decreased by 2%.

The exhibit illustrates that people in the lowest quintile were those who had the highest decrease in their market income. It also illustrates that the increase in after-tax income was substantial for lower‑income families and compensated for their loss of income.

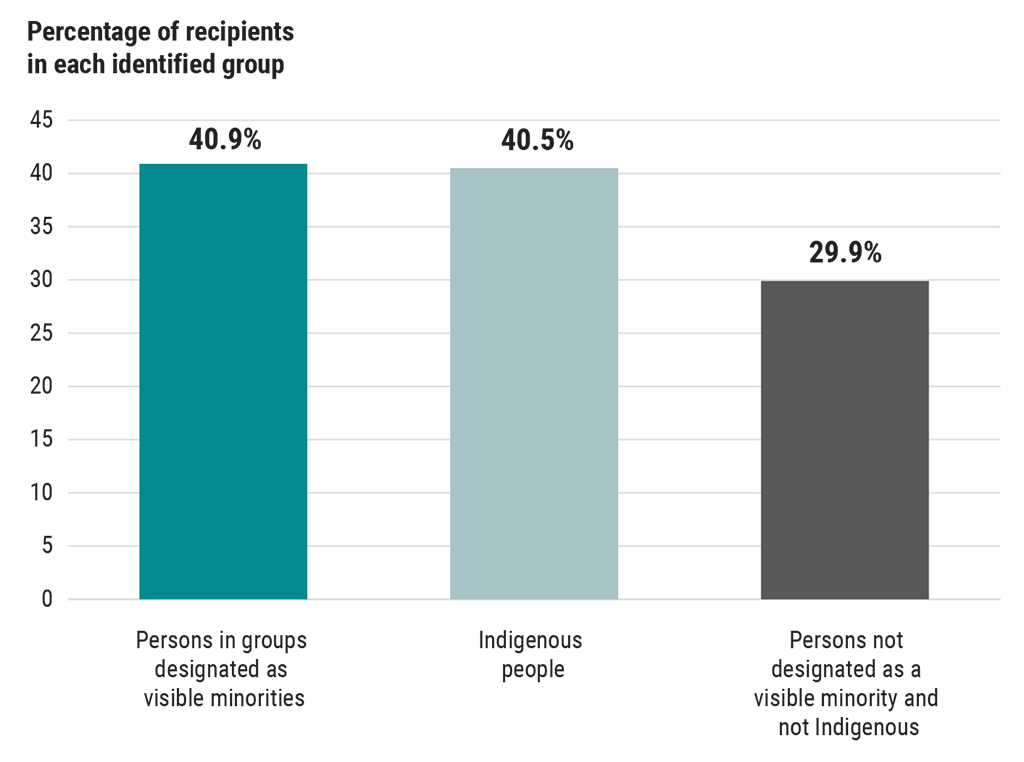

A higher proportion of people in visible minority and Indigenous groups received benefits than in groups not designated as such

Note: Federal COVID‑19 benefits include the Canada Emergency Response Benefit, the Canada Emergency Student Benefit, the Canada Recovery Benefit, the Canada Recovery Caregiving Benefit, the Canada Recovery Sickness Benefit, and a 1‑time payment made to Canadians with disabilities.

Source: Statistics Canada

Text version

This bar chart shows the percentage of people in 3 groups who received benefits.

A higher percentage of people in visible minority and Indigenous groups received benefits compared with the percentage for the group of recipients not designated as visible minorities or Indigenous people.

Following are the percentages of people in each group who received benefits:

- persons in groups designated as visible minorities: 40.9% of people in this group received benefits

- Indigenous people: 40.5% of people in this group received benefits

- persons not designated as a visible minority and not Indigenous: 29.9% of people in this group received benefits

The federal COVID‑19 benefits included in this chart were the Canada Emergency Response Benefit, the Canada Emergency Student Benefit, the Canada Recovery Benefit, the Canada Recovery Caregiving Benefit, the Canada Recovery Sickness Benefit, and a 1‑time payment made to Canadians with disabilities.

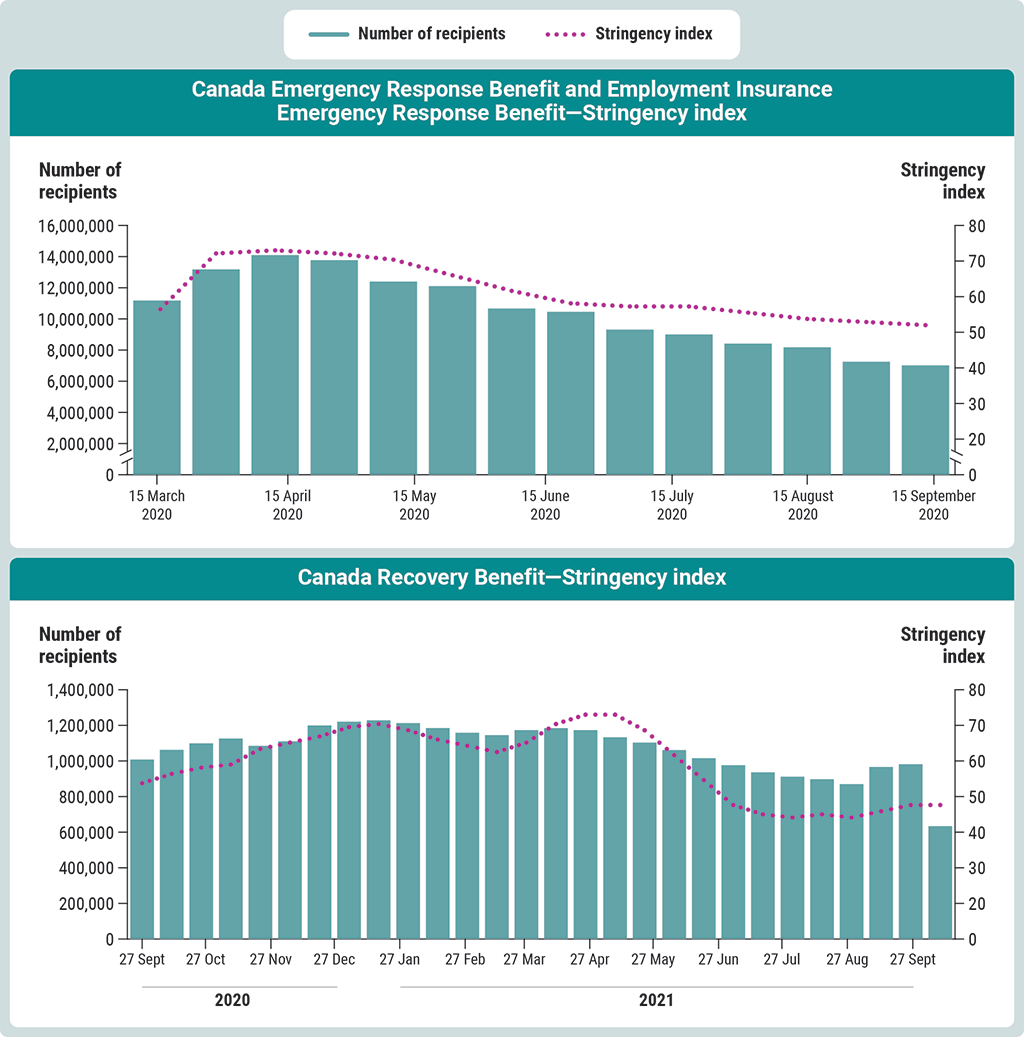

The trend in the number of people receiving benefits aligned with the level of severity of COVID‑19‑related restrictions

Note: The stringency index measures the severity of policies governments put in place to protect people against the transmission of COVID‑19. A higher index score indicates a higher level of COVID‑19–related restrictions on individuals and employers. Values shown for the stringency index are averages of the daily scores for the 2‑week periods for the programs.

Source: Stringency index—Bank of Canada; number of recipients based on data provided by the Canada Revenue Agency and Employment and Social Development Canada

Text version

These 2 charts show the number of recipients of certain COVID‑19 benefit programs compared with the stringency index over certain periods of time. The stringency index measures the severity of policies governments put in place to protect people against the transmission of COVID‑19.

By comparing the number of recipients of benefit programs with the severity of the stringency index, the 2 charts show trends:

- The first chart shows the Canada Emergency Response Benefit and the Employment Insurance Emergency Response Benefit. Over the period from 15 March 2020 to 15 September 2020, the number of recipients of these programs aligned with the stringency index—that is, when the severity of government policies increased to protect against COVID‑19, the number of benefit recipients also increased. And when the severity of government policies decreased, the number of benefit recipients also decreased.

- The second chart shows the Canada Recovery Benefit. Over the period from 27 September 2020 to 27 September 2021, the number of recipients of this program aligned roughly with the stringency index until about June 2021, when the severity of government policies decreased but the number of benefit recipients did not decrease at the same pace.

Following is the detailed data for the first chart about the Canada Emergency Response Benefit and the Employment Insurance Emergency Response Benefit by 2‑week time periods starting from 15 March 2020:

- On 15 March 2020, the number of recipients was 11,174,180 and the stringency index was 52.

- On 29 March 2020, the number of recipients was 13,176,380 and the stringency index was 71.

- On 12 April 2020, the number of recipients was 14,097,180 and the stringency index was 72.

- On 26 April 2020, the number of recipients was 13,769,250 and the stringency index was 71.

- On 10 May 2020, the number of recipients was 12,392,800 and the stringency index was 69.

- On 24 May 2020, the number of recipients was 12,106,650 and the stringency index was 64.

- On 7 June 2020, the number of recipients was 10,665,710 and the stringency index was 59.

- On 21 June 2020, the number of recipients was 10,453,500 and the stringency index was 55.

- On 5 July 2020, the number of recipients was 9,312,350 and the stringency index was 54.

- On 19 July 2020, the number of recipients was 9,000,420 and the stringency index was 54.

- On 2 August 2020, the number of recipients was 8,411,660 and the stringency index was 52.

- On 16 August 2020, the number of recipients was 8,175,200 and the stringency index was 50.

- On 30 August 2020, the number of recipients was 7,250,970 and the stringency index was 49.

- On 13 September 2020, the number of recipients was 7,014,700 and the stringency index was 48.

Following is the detailed data for the second chart about the Canada Recovery Benefit by 2‑week time periods starting from 27 September 2020:

- On 27 September 2020, the number of recipients was 1,007,770 and the stringency index was 50.

- On 11 October 2020, the number of recipients was 1,062,280 and the stringency index was 53.

- On 25 October 2020, the number of recipients was 1,098,890 and the stringency index was 55.

- On 8 November 2020, the number of recipients was 1,125,700 and the stringency index was 56.

- On 22 November 2020, the number of recipients was 1,084,940 and the stringency index was 61.

- On 6 December 2020, the number of recipients was 1,109,840 and the stringency index was 63.

- On 20 December 2020, the number of recipients was 1,199,230 and the stringency index was 65.

- On 3 January 2021, the number of recipients was 1,220,570 and the stringency index was 68.

- On 17 January 2021, the number of recipients was 1,228,120 and the stringency index was 69.

- On 31 January 2021, the number of recipients was 1,212,810 and the stringency index was 67.

- On 14 February 2021, the number of recipients was 1,184,810 and the stringency index was 64.

- On 28 February 2021, the number of recipients was 1,158,480 and the stringency index was 62.

- On 14 March 2021, the number of recipients was 1,145,110 and the stringency index was 60.

- On 28 March 2021, the number of recipients was 1,173,070 and the stringency index was 63.

- On 11 April 2021, the number of recipients was 1,184,410 and the stringency index was 69.

- On 25 April 2021, the number of recipients was 1,173,170 and the stringency index was 72.

- On 9 May 2021, the number of recipients was 1,132,910 and the stringency index was 72.

- On 23 May 2021, the number of recipients was 1,103,160 and the stringency index was 67.

- On 6 June 2021, the number of recipients was 1,061,170 and the stringency index was 59.

- On 20 June 2021, the number of recipients was 1,015,480 and the stringency index was 51.

- On 4 July 2021, the number of recipients was 976,220 and the stringency index was 43.

- On 18 July 2021, the number of recipients was 936,080 and the stringency index was 40.

- On 1 August 2021, the number of recipients was 911,550 and the stringency index was 39.

- On 15 August 2021, the number of recipients was 897,480 and the stringency index was 40.

- On 29 August 2021, the number of recipients was 869,990 and the stringency index was 39.

- On 12 September 2021, the number of recipients was 966,220 and the stringency index was 41.

- On 26 September 2021, the number of recipients was 981,840 and the stringency index was 43.

About the stringency index: A higher index score indicates a higher level of COVID‑19–related restrictions on individuals and employers. Values shown for the stringency index are averages of the daily scores for the 2 week periods for the programs.

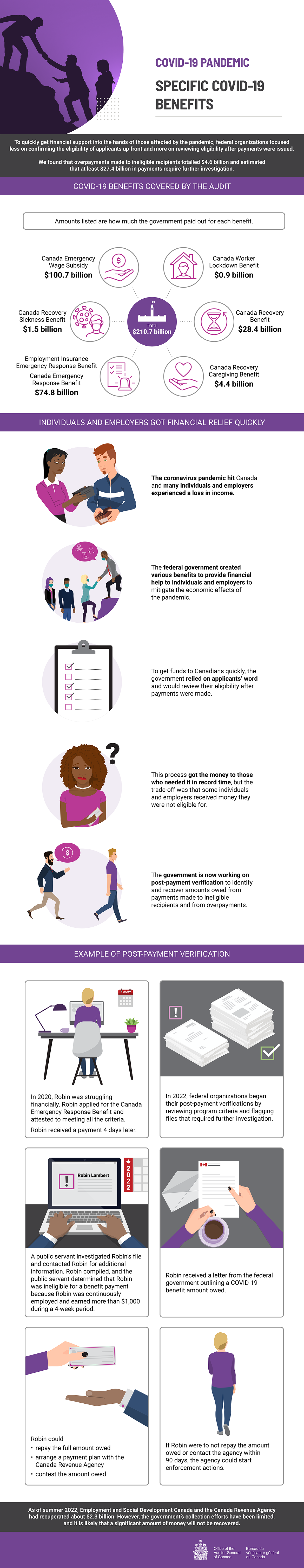

Infographic

Text version

Specific COVID-19 Benefits

To quickly get financial support into the hands of those affected by the pandemic, federal organizations focused less on confirming the eligibility of applicants up front and more on reviewing eligibility after payments were issued.

We found that overpayments made to ineligible recipients totalled $4.6 billion and estimated that at least $27.4 billion in payments require further investigation.

COVID-19 benefits covered by the audit

The federal government spent a total of $210.7 billion on the COVID‑19 benefits covered by the audit. The following amounts are how much the government paid out for each benefit:

- Canada Worker Lockdown Benefit: $0.9 billion

- Canada Recovery Benefit: $28.4 billion

- Canada Recovery Caregiving Benefit: $4.4 billion

- Employment Insurance Emergency Response Benefit and Canada Emergency Response Benefit: $74.8 billion

- Canada Recovery Sickness Benefit: $1.5 billion

- Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy: $100.7 billion

Individuals and employers got financial relief quickly

The coronavirus pandemic hit Canada and many individuals and employers experienced a loss in income.

The federal government created various benefits to provide financial help to individuals and employers to mitigate the economic effects of the pandemic.

To get funds to Canadians quickly, the government relied on applicants’ word and would review their eligibility after payments were made.

This process got the money to those who needed it in record time, but the trade-off was that some individuals and employers received money they were not eligible for.

The government is now working on post-payment verification to identify and recover amounts owed from payments made to ineligible recipients and from overpayments.

Example of post-payment verification

- In 2020, Robin was struggling financially. Robin applied for the Canada Emergency Response Benefit and attested to meeting all the criteria. Robin received a payment 4 days later.

- In 2022, federal organizations began their post-payment verifications by reviewing program criteria and flagging files that required further investigation.

- A public servant investigated Robin’s file and contacted Robin for additional information. Robin complied, and the public servant determined that Robin was ineligible for a benefit payment because Robin was continuously employed and earned more than $1,000 during a 4‑week period.

- Robin received a letter from the federal government outlining a COVID‑19 benefit amount owed.

- Robin could

- repay the full amount owed

- arrange a payment plan with the Canada Revenue Agency

- contest the amount owed

- If Robin were to not repay the amount owed or contact the agency within 90 days, the agency could start enforcement actions.

Recovery and collection

As of summer 2022, Employment and Social Development Canada and the Canada Revenue Agency had recuperated about $2.3 billion. However, the government’s collection efforts have been limited, and it is likely that a significant amount of money will not be recovered.

Related information

Tabling date

- 6 December 2022

Related audits

- 2021 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada

Report 6—Canada Emergency Response Benefit - 2021 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada

Report 7—Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy