Commentary on the 2022–2023 Financial Audits

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Results of our 2022–2023 financial audits

- Auditor General’s observations on the Government of Canada’s 2022–23 consolidated financial statements

- Environmental, social, and governance reporting

- Exhibits:

- 1—COVID-19 benefit overpayments or ineligible payments determined by the government (in millions)

- 2—Canada Emergency Business Account program (in millions)

- 3—Information Technology (IT) general controls

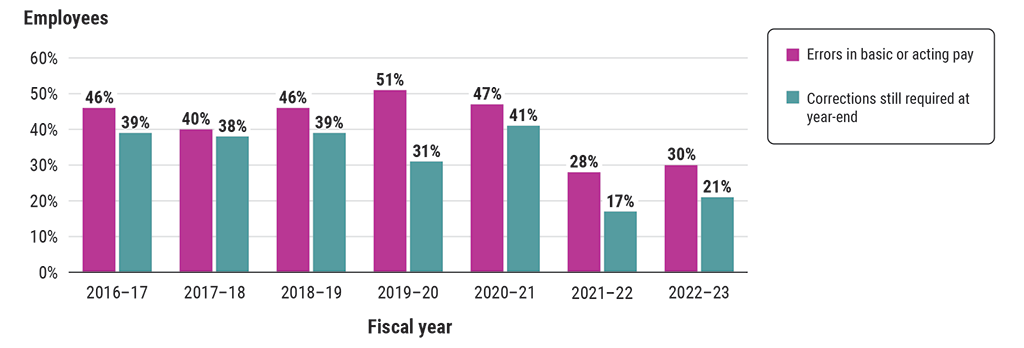

- 4—Percentage of employees in our sample with an error in basic or acting pay and who were awaiting a correction at year-end

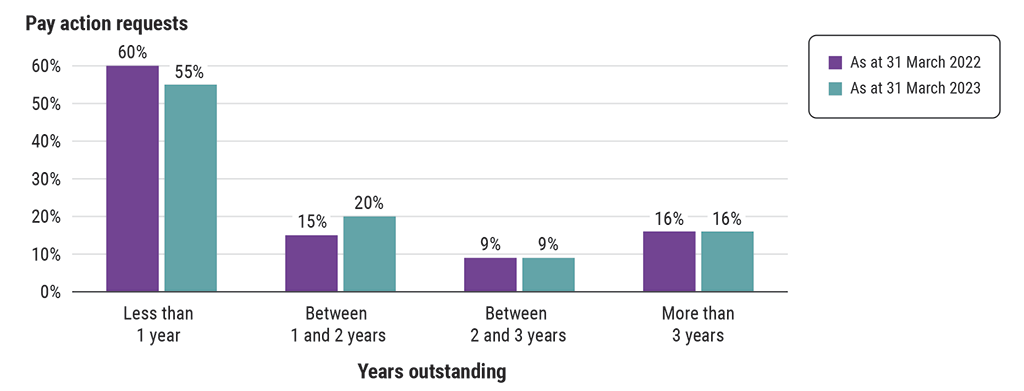

- 5—Percentage of pay action requests in the departments and agencies served by the Public Service Pay Centre, by number of years outstanding

Introduction

1. This report provides a commentary based on the results of the Auditor General of Canada’s financial audits of federal organizations for the fiscal years ended between 31 July 2022 and 30 April 2023 (referred to here as the 2022–2023 financial audits). This commentary includes the Auditor General’s observations on significant findings identified as part of our audit of the Government of Canada’s consolidated financial statements. We also provide insights on environmental, social and governance reportingDefinition 1 done by federal organizations, where this relates to our audit work.

2. The commentary contains information that will help readers see behind the numbers to better understand how the government manages its finances. Our financial audits support the accountability relationship between Parliament and the government organizations that spend taxpayer dollars to deliver programs and services. This accountability helps to ensure that the spending of taxpayer dollars serves the best interests of the public.

Results of our 2022–2023 financial audits

Audit opinions

3. This year, the Office of the Auditor General of Canada issued unmodified audit opinions, which means that the financial statements prepared by the 69 federal government organizations we audit were credible and were reported on time. An unmodified audit opinion confirms the credibility of the government’s financial reporting. Financial reporting is one way the government demonstrates accountability to elected officials and the public. The list of these federal organizations is found on our website.

4. In particular, we provided the Government of Canada with an unmodified audit opinion on its 2022–23 consolidated financial statements. However, this year we noted weaknesses in 2 new areas:

- the government’s adoption of a new accounting standard

- the government’s information technology general controlsDefinition 2

We provide more information on these matters in the Auditor General’s observations section in this report.

5. For the second year, the Trans Mountain Corporation’s year-end financial statements disclosed a significant uncertainty about the Crown corporation’s ability to continue operating. We drew attention to this disclosure in our independent auditors’ report that we issued jointly with another independent auditor at the completion of our audit of the corporation’s financial statements. The uncertainty was related to the corporation’s ability to fund the remaining construction costs of the Trans Mountain expansion project and to make the necessary payments on its existing debt.

6. While this disclosure did not cause us to modify our audit opinion on the Trans Mountain Corporation’s 31 December 2022 financial statements, we assessed the uncertainty to be important enough to mention it in our report. During our audit work, we also assessed that the corporation appropriately described the matter in a note in its financial statements.

7. In January 2023, the corporation revised its cost estimate for the pipeline expansion project to $30.9 billion. The corporation had previously reported costs of the project as of 31 December 2022 to be $21.1 billion. In early 2023, the corporation proposed a borrowing plan to finance the remaining construction costs. The Treasury Board approved both the revised cost estimate and the borrowing plan in April 2023 through the 2023–27 corporate plan of the Canada Development Investment Corporation (the Trans Mountain Corporation’s parent Crown corporation). This corporate plan also anticipates that the revenue from the transport of crude oil in the expanded pipeline will begin in the first quarter of 2024.

8. In February 2022, the Government of Canada announced it would spend no additional public money on the pipeline. Since then, Trans Mountain Corporation has had to obtain external financing to fund the remaining costs of the project. If the corporation cannot finance the full remaining construction of the pipeline expansion, it will be unable to put the expanded pipeline into service to generate revenue.

9. In July 2023, the corporation reported that the borrowing limit on its existing credit facility with a group of Canadian financial institutions, which is guaranteed by the Government of Canada, was increased to $16 billion. Notably, as of 31 December 2022, the corporation had already borrowed $7.2 billion from this credit facility. Given that it will need additional funding to meet the remaining construction costs, the corporation, in its unaudited financial statements for the second quarter of 2023, continued to report a significant uncertainty over continuing operations.

10. Our mandate includes bringing important matters like this to Parliament’s attention. In our annual audits of the consolidated financial statements, we will continue to assess the risks of Trans Mountain Corporation’s ability to fund the remaining costs of the pipeline expansion project and to keep operating.

Adoption of a new assurance standard for key audit matters

11. Under a new Canadian auditing standard, auditors of financial statements of listed entities are required to report key audit matters—that is, matters of most significance in the audit. These can include areas

- where the auditor has difficulty obtaining enough evidence to determine whether the financial statements are fairly presented

- where federal organizations had to make significant decisions about what facts and figures to use in their accounting

- where the matter affects the auditor’s overall strategy, allocation of resources, and extent of efforts

- where the auditor needs to involve senior personnel or an outside expert

12. The Canadian standard aligns with international audit standards, which aim to give readers of financial statements more information that comes out of the audit process. This standard came into effect for the audit of the Government of Canada’s consolidated financial statements for the year ended 31 March 2023. This standard does not apply to any of the other audits we do on federal organizations.

13. The key audit matters in this year’s independent auditor’s report of the government’s consolidated financial statements were related to the following areas:

- tax revenues

- personnel expenses

- pension liabilities and other future benefits

- contingent liabilities

- asset retirement obligations

- financial instruments

- military inventory and asset pooled items (assets that are similar to inventory)

14. We report on key audit matters in our independent auditor’s report on the Government of Canada’s consolidated financial statements, in Volume I of the 2022–23 Public Accounts of Canada. In that report, we describe each matter and our audit response. These matters are not findings or results of our audit work, and they do not modify our audit opinion. They are intended to help readers of the financial statements, such as parliamentarians, better understand the audit work we carried out in support of the audit opinion.

COVID-19 benefits programs

15. In March 2020, the Government of Canada announced Canada’s COVID-19 Economic Response Plan. To minimize the impact of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19)Definition 3 pandemic on the health of Canada’s population, businesses, and economy, the plan included emergency income support programs for individuals and businesses in Canada.

16. Our 2020–2021 and 2021–2022 commentaries on financial audits summarized the effects of these support measures on the government’s consolidated financial statements. Along with annual financial audits, our audit work on these measures included responding to an April 2020 motion from Parliament related to the COVID-19 Emergency Response Act and doing 11 performance audits as of 31 March 2023.

17. To expedite issuing payments, most of these support measures relied on applicants’ attestations of eligibility and had limited pre-payment controls, with the intention to verify eligibility later. In our 2022 performance audit Report 10—Specific COVID-19 Benefits, we estimated that at least $27.4 billion of payments to individuals and businesses should be investigated further through post-payment verification to confirm their eligibility. In that report, we recommended that the Canada Revenue Agency and Employment and Social Development Canada should update their post-payment verification plans to identify payments to ineligible recipients of benefits, keeping in mind the legislated time frames.

18. These organizations developed action plans in response to our audit recommendations, which they provided to Parliament. Employment and Social Development Canada’s action plan noted that its post-payment verifications were ongoing. Canada Revenue Agency’s action plan noted that its post-payment verification work is expected to continue until March 2025.

19. This year, through our audit work, we noted that the government continued to carry out post-payment verifications of benefit payments to confirm the eligibility of recipients. In cases where the government determined overpayments or ineligible payments, it recorded the amounts as accounts receivable (Exhibit 1). The government provided information about these transactions in the notes to its consolidated financial statements. For example, in note 5, the government stated that it expects post-payment verification activities to continue for years and that the cumulative value of overpayments has not been determined but could be material.

Exhibit 1—COVID-19 benefit overpayments or ineligible payments determined by the government (in millions)

| Amount in the 2020–21 fiscal year |

Amount in the 2021–22 fiscal year |

Amount in the 2022–23 fiscal year |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Beginning balance of accounts receivable of COVID-19 benefits | - | $3,742 million | $5,119 million |

| Overpayments or ineligible payments to individuals determined by the government | $4,832 million | $1,630 million | $3,730 million |

| Overpayments or ineligible payments to businesses determined by the government | $435 million | $281 million | $330 million |

| Repayments made by recipients | ($1,525) million | ($534) million | ($2,217) million |

| Ending balance of accounts receivable of COVID-19 benefits | $3,742 million | $5,119 million | $6,962 million |

Benefits to individuals include the Canada Emergency Response Benefit, Employment Insurance Emergency Response Benefit, Canada Recovery Benefit, Canada Recovery Sickness Benefit, Canada Recovery Caregiving Benefit, Canada Worker Lockdown Benefit, and Canada Emergency Student Benefit. Benefits to businesses include the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy and Canada Emergency Rent Subsidy.

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s audit of the consolidated financial statements of the Government of Canada.

20. The Canada Revenue Agency and Employment and Social Development Canada only partially agreed with a key recommendation from our 2022 performance audit Report 10 to increase the extent of verifications to be performed for cases identified as being at risk of being ineligible. As a result, despite the work carried out by the government in the last 3 fiscal years, we remain concerned that it may not be investigating significant amounts of payments made to ineligible individuals or businesses, which it therefore may not identify or recover.

21. Given the limited pre-payment controls when the payments were issued, the post-payment verifications are important. We expect the government, as the steward of public funds, to continue to verify that the benefits it paid to recipients met the eligibility criteria set out in legislation.

22. As part of its COVID-19 Economic Response Plan, the government provided approximately $49 billion in interest-free loans of up to $60,000 to small businesses and not-for-profit corporations through the Canada Emergency Business Account program (Exhibit 2). The application period for the program closed on 30 June 2021. The government will forgive a portion of the loan, up to 33%, as an incentive if the recipient repays the required portion of the loan by a set deadline. At the time of our audit, the deadline was 31 December 2023.

Exhibit 2—Canada Emergency Business Account program (in millions)

| Amount in the 2020–21 fiscal year |

Amount in the 2021–22 fiscal year |

Amount in the 2022–23 fiscal year |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Beginning balance of loans receivable | - | $44,881 million | $44,666 million |

| Loans issued | $45,282 million | $3,767 million | - |

| Loans repaid | $(401) million | $(3,160) million | $(3,159) million |

| Loans written off | - | - | $(5) million |

| Loan incentives realized | - | $(822) million | $(1,349) million |

| Ending balance of loans receivable | $44,881 million | $44,666 million | $40,153 million |

| Estimated remaining loan incentives | $(13,085) million | $(13,778) million | $(12,870) million |

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s audit of the consolidated financial statements of the Government of Canada

23. In its 2020–21 consolidated financial statements, the government estimated that it would need to grant $13.1 billion in loan incentives to those recipients who repaid their loans by the set deadline. It recorded this amount as an expense and as a reduction of the amount of loans owed. As loans are repaid, the estimated amount of remaining loan incentives decreases. After the deadline, the amount of all loan incentives will become known with certainty. Beyond that date, the government will be able to collect any remaining portion of loan incentives.

24. In addition, because some of the loans are at risk of not being repaid, the government annually estimates an allowance for anticipated losses. This amount is recorded in note 19 to the consolidated financial statements within the amount of the valuation allowance for the Canada Emergency Business Account program.

Auditor General’s observations on the Government of Canada’s 2022–23 consolidated financial statements

Asset retirement obligations

25. The Government of Canada owns tangible capital assets, such as buildings, equipment, and vehicles. These are managed by various federal organizations across Canada. As of 31 March 2023, these assets had a value of approximately $97 billion. When it comes time to retire or demilitarizeDefinition 4 some of these tangible capital assets, the government will legally have to take certain actions. For example, it may have to remove asbestos from buildings or clean up and dismantle nuclear facilities. The costs of this type of future legal obligation are known as asset retirement obligations.

26. Developing an understanding of these obligations has several benefits. It provides the government with information about the full life cycle of its assets and helps determine the financial resources that it will need to retire the assets. However, the accounting for asset retirement obligations is complex. To estimate the cost of future transactions, federal organizations have to analyze relevant information and make certain assumptions. For example, they must consider factors such as

- the legal obligations relating to the asset

- how long the asset will continue to be useful

- the rate of the asset’s potential deterioration

- the rate to use in estimating the costs in today’s dollars

- the timing, scope, and cost of future work

27. Starting in the 2022–23 fiscal year, federal organizations analyzed and recorded liabilities for these asset retirement obligations in their accounting records. They did this to meet the requirements of a new Canadian public sector accounting standard. These estimates were compiled and reported in the government’s 2022–23 consolidated financial statements. Federal organizations will annually update these estimates and consider whether new obligations exist until the obligations are fulfilled.

28. As of 31 March 2023, the government estimated that it has asset retirement obligations of $12.9 billion. It disclosed information about them in note 9 to its consolidated financial statements. Because of the significant amounts of the government’s asset retirement obligations and the complexity of reporting on them, we considered the government’s adoption of this standard to be a key audit matter. We described how we addressed the matter in our independent auditor’s report.

29. Our audit noted weaknesses in the government’s process for analyzing and determining the amount of its asset retirement obligations. These weaknesses were primarily in obligations related to dealing with asbestos and other hazardous material and demilitarizing or disarming assets, which represent $4.2 billion of the total asset retirement obligations. The following are examples of noted weaknesses:

- The data some federal organizations used to estimate retirement costs was of poor quality, which means their estimates may not be accurate and need improvement.

- Some federal organizations began financial analyses only recently or waited until very late to complete them, despite having 5 years since the accounting standard was first published. This led to some weakness in their methods for estimating asset retirement obligations. As a result, these federal organizations will need to gather and analyze more information to change or refine their methods.

- Federal organizations lacked guidance from the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. For example, there was no model or approach for how to account for removing asbestos from federal buildings. This resulted in duplicated efforts, inefficient use of time and resources, and inconsistencies in how key measurement assumptions were applied across organizations. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat should improve the oversight, leadership, and advice it offers to federal organizations that hold tangible capital assets. This would increase the accuracy of the estimated obligations the government reports.

30. As a result of the weaknesses noted above, we had to significantly increase our efforts to audit the asset retirement obligations and related transactions reported in the government’s 2022–23 consolidated financial statements. We increased the scope of our work and added more resources to our audit team. To assess whether the asset retirement obligations were complete and accurate, we did additional analysis and independently tested some key assumptions. It is likely that next year’s audit will continue to require a higher audit effort unless the government improves the process.

31. We did not modify our audit opinion as a result of our audit findings in this area. Overall, the weaknesses described did not have a significant effect on the consolidated financial statements. We were still able to conclude that, in all material respects, the government fairly presented the asset retirement obligations in its consolidated financial statements.

Information technology general controls

32. The Government of Canada uses its information technology (IT) systems to support the delivery of programs and services to Canadians and to maintain necessary records. It also uses the data stored in these systems to prepare financial reporting documents, such as the Public Accounts of Canada. Every year as part of our audit, we examine certain IT general controls to assess whether they are operating effectively to ensure the integrity of the data the systems process.

33. IT general controls consist of restrictions to help manage access to systems and data, changes to the system, and system operations (Exhibit 3). If IT general controls are ineffectively designed or poorly implemented, the data stored in the government’s databases has an increased risk of being incomplete, inaccurate, or compromised. The lack of IT controls in organizations can lead, for example, to the disruption of operations, sabotage, or the transmission of unauthorized data outside the organization.

Exhibit 3—Information Technology (IT) general controls

| Types of IT general controls | Description |

|---|---|

|

Manage access |

These controls prevent unauthorized users from accessing systems and data. For example, a username and password are required to gain access to a database, or a security badge is required to gain entry to a secure room. |

|

Manage change |

These controls prevent inappropriate changes to IT systems infrastructure. For example, changes prepared by one person must be approved by a separate person before they are implemented. |

|

Manage IT operations |

These controls are routine tasks performed to ensure systems operate as intended. For example, an error message occurs when transaction records are transferred between systems in a way that is incomplete or inaccurate. |

34. This year, we found deficiencies in controls over access to key systems that store and process data related to payments, receipts, and accounting records. The data in these systems is essential to the government’s preparation of its consolidated financial statements. Certain users had access to government systems and databases that they did not need to fulfill their duties. Controls should have been in place to deny this access or to detect it later. This access gave these users the ability to make changes to the government’s systems and data, which increases the risk of fraud or other wrongdoing.

35. In our work, nothing came to our attention to indicate that there had been inappropriate changes made to data or data breaches as a result of the inappropriate access. Since our communication about this deficiency, the government had started a project to remove access where users did not require it and reconsider the access required for different user responsibilities. Corrections were made starting in May 2023 and additional reviews were ongoing.

36. As a result of the deficiencies noted, we performed additional audit work to support our conclusion on the fair presentation, in all material respects, of the balances, transactions, and disclosures in the government’s consolidated financial statements. However, this additional audit work does not in itself lessen the risk of fraud or privacy breaches.

37. Given the importance of the government’s IT systems, we expect the government to take action to completely address the deficiencies noted. We also encourage the government and all federal organizations to review, monitor, and strengthen the IT general controls of their systems and data.

Continuing observations requiring further action

38. The following are observations on matters that we have reported on for the past several years but that have not yet been resolved. While we are encouraged by the actions the Government of Canada has taken to address some weaknesses raised, further action is needed.

Pay administration

39. In 2016, the Government of Canada, through the Transformation of Pay Administration Initiative, centralized the employee payroll for 46 departments and agencies. Since then, weaknesses in internal control of the HR-to-pay process prevented us from testing and relying on those controls in our audit work. As a result, we did detailed testing of a sample of federal employees’ pay transactions from all 98 federal organizations reported in the government’s consolidated financial statements.

40. We expect the government to have pay processes with internal controls that ensure employees are paid accurately and on time. This expectation remains regardless of whether the government keeps its current pay system for some organizations or puts a new one in place.

41. In our audit work, we found that

- 30% of employees we sampled had an error in their basic or acting pay during the 2022–23 fiscal year, compared with 28% in the prior year

- 21% of employees we sampled still required corrections to their pay as of 31 March 2023, an increase from the 17% reported in the prior year (Exhibit 4)

Exhibit 4—Percentage of employees in our sample with an error in basic or acting pay and who were awaiting a correction at year-end

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General’s analysis of a sample of employees’ pay transactions used in the audit of the consolidated financial statements of the Government of Canada for the 7 fiscal years ending March 31 from 2017 to 2023

Exhibit 4—text version

This bar chart shows for each fiscal year from 2016–17 to 2022–23 the percentage of employees in our sample with an error in basic or acting pay and who were awaiting a correction at year‑end.

The chart shows that the percentage of employees in our sample who had an error in basic or acting pay during the fiscal year decreased from 46% in 2016–17 to 40% in 2017–18 and then increased to 46% in 2018–19 and to 51% in 2019–20. The percentage then decreased to 47% in 2020–21 and to 28% in 2021–22. In 2022–23 the percentage increased to 30%.

The chart also shows that the percentage of employees in our sample who were awaiting a correction at year-end was steady at either 38% or 39% for the 3 fiscal years from 2016–17 to 2018–19 and then decreased to 31% in 2019–20. The percentage then increased to 41% in 2020–21, decreased to 17% in 2021–22, and increased to 21% in 2022–23.

42. We assessed that these errors were not due to problems with the way the pay system performed calculations, but rather were due mainly to inaccurate data being entered into the pay system and to delays in processing pay. Of the 30% of employees in our sample that had errors, roughly one third had errors because of inaccurate data and roughly two thirds had errors because of delays in processing pay. The delays varied from 2 months to nearly 3 years. The government has done quality reviews to address the weaknesses we have noted in our audits since 2016. However, it needs to take further action to strengthen internal controls spanning the entire HR-to-pay process to make sure that data is accurate and in this way to prevent or detect errors in pay.

43. We concluded that pay expenses were fairly presented in the government’s 2022–23 consolidated financial statements. This conclusion was partly because

- overpayments and underpayments made to employees partially offset each other

- the government made year-end accounting adjustments to improve the accuracy of how pay expenses were reported in the financial statements

44. The Public Service Pay Centre continued to address the outstanding pay action requests during the year. The pay centre’s objective is to process 95% of pay action requests within the service standards for the type of request. The pay centre tracks its performance in meeting this target on its website. However, as of 31 March 2023, there were 405,000 outstanding pay action requests. This was an increase from 310,500 reported as of 31 March 2022. Outstanding pay action requests of previous years reached a peak level of 579,700 in March 2018.

45. We analyzed how long pay action requests remained unresolved. We found that as of 31 March 2023, 16% of pay action requests, or approximately 65,000, were outstanding for more than 3 years (Exhibit 5). This was similar to the 16%, or approximately 50,000 requests, a year ago. The situations where requests remained unresolved for years varied. For example, some requests resulted from

- situations where an employee was underpaid and may have been granted a salary advance

- situations where an employee was overpaid and the government was in the process of recovering the overpayment

Exhibit 5—Percentage of pay action requests in the departments and agencies served by the Public Service Pay Centre, by number of years outstanding

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of data in Public Services and Procurement Canada’s Case Management Tool

Exhibit 5—text version

This chart shows the percentage of pay action requests in the departments and agencies served by the Public Service Pay Centre by number of years outstanding as at 31 March 2022 and as at 31 March 2023. The percentage of pay action requests that were outstanding for less than 1 year decreased from 60% as at 31 March 2022 to 55% as at 31 March 2023. The percentage of pay action requests that were outstanding for between 1 and 2 years increased from 15% as at 31 March 2022 to 20% as at 31 March 2023. The percentage of pay action requests that were outstanding for between 2 and 3 years remained steady at 9% as at 31 March 2022 and 31 March 2023. The percentage of pay actions requests that were outstanding for more than 3 years also remained steady at 16% as at 31 March 2022 and 31 March 2023.

46. When the government does not take action or resolve cases involving overpayments over many years, the options to recover the amounts owed decrease over time. This could result in the government writing off the amounts. The risk of such losses persists. As of 31 March 2023, on the basis of data in the pay system, Public Services and Procurement Canada estimated that

- outstanding pay action requests involved a total of more than $500 million in overpayments that it was working to collect from more than 100,000 employees

- approximately one third of these requests had been outstanding for more than 5 years

47. Although the pay centre has taken action to resolve requests and has recovered a portion of these overpayments, clearly more work is to be done.

48. For several years, we have reported on the total number of outstanding pay action requests in the departments and agencies served by the pay centre. Since our 2021–22 commentary, the government has made additional investments, such as funding in Budget 2023 for the pay centre to hire more compensation advisors, who process pay transactions and follow up on pay action requests. Given this, we expect the government in the coming years to improve in resolving outstanding requests and to meet the service standards it established.

49. As part of our annual financial audit work, we stay aware of the government’s plans for developing new information systems that could affect financial reporting. In 2018, the government announced its intention to eventually replace the current pay system with the Next Generation Human Resources and Pay (NextGen) system—a large, multi-year, multi-phase initiative.

50. After several years, the NextGen system is still in its research and experimentation phase. The government is preparing a report on the results of its testing and pilot projects completed in June 2023. The report will provide information on a strategy for an integrated human resources and pay system. Once the government progresses to later phases of the initiative, we will assess our next potential involvement as their external auditor.

National Defence inventory and asset pooled items

51. For 2 decades, we have raised concerns about National Defence’s ability to properly account for the quantities and values of its inventory. We have also reported on the department’s asset pooled items, which are tangible capital assets that are managed like inventory. The department manages a significant portion of the Government of Canada’s inventory and all of its asset pooled items. Overall, as of 31 March 2023, these assets amounted to $8.4 billion. This year in our audit, we estimated a combined understatement of inventory and asset pooled items of $42 million, as compared with $232 million a year earlier.

52. In our work, we tested the quantities, values, and classification of inventory and asset pooled items. This year, we found errors in at least 1 of these characteristics in approximately 17% of the items we sampled, as compared with 15% in our 2021–22 testing. In our view, these errors indicate continued weaknesses in internal controls that the department needs to address.

53. In 2016, National Defence established an inventory management action plan to better record, calculate the value of, and manage its inventory. As previously reported in the Auditor General’s observations on this matter, the department has not yet met its long-term commitment in its action plan to implement a modern scanning and barcoding system. The department has fallen further behind its original schedule to implement the system as it continues to refine its requirements. The department now projects the system will be fully operational in 2028–29.

54. Managing and reporting on inventory and asset pooled items requires a significant level of effort. It is important for the department to

- maintain adequate records and strong controls over these assets to efficiently and cost-effectively manage its operations

- address the root causes of discrepancies and strengthen internal controls to improve data quality, which can also provide opportunities to improve decision making

55. By taking these actions, the department would improve its potential to benefit from future investments in technology, such as its scanning and barcoding system and its planned upgrade to a new system for enterprise resource planning.

Environmental, social, and governance reporting

56. As we noted in our Commentary on the 2021–2022 Financial Audits, federal organizations have increased their reporting on sustainability (also referred to as environmental, social, and governance reporting). This is in response to requirements in legislation, government policies and pronouncements (such as federal budgets), and increased public interest.

57. More specifically, the following are developments that federal organizations will need to consider when reporting on sustainability matters, and particularly on climate-related financial risks:

- As requested by Budget 2021, Crown corporations holding more than $1 billion of assets began reporting on financial risks related to climate change for their fiscal years beginning in 2022. The remainder of Crown corporations will begin such reporting for fiscal years beginning in 2024.

- New International Financial Reporting Standards were issued in June 2023 providing a framework to disclose information on sustainability and exposure to risks and opportunities related to climate change. The standards were developed primarily for capital markets and become effective 1 January 2024 if required by a given jurisdiction. Although federal organizations are not required to report under these standards, the standards provide valuable guidance about sustainability reporting.

- Other standard setters, such as the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board and the International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board, also have relevant sustainability projects underway.

- As part of the federal government’s Greening Government Strategy, in 2022 departments and agencies began doing periodic assessments and taking action to reduce climate risks to assets, services, and operations. As the government gathers more information about climate risks over time, this could affect the information disclosed in the government’s consolidated financial statements or other government reports.

- Under the Canadian Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act, the Minister of Finance will annually publish a report outlining key measures that the federal public administration has taken to manage the financial risks and opportunities related to climate change.

- The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institution’s guideline on climate risk management will come into effect for certain banks and insurance companies in 2024 and for other federally regulated financial institutions in 2025. The guideline does not apply to the federal organizations we audit. However, Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation plans to adopt it, consistent with other mortgage insurers that are subject to federal regulations.

58. Some federal organizations also include sustainability reporting in their annual reports. Canadian auditing standards require that we review annual reports to check that they are consistent with financial statements. Note that even though we review information in annual reports, our auditor’s opinion applies only to the audited financial statements.

59. Our review of the annual reports of the federal organizations we audit included those of Crown corporations that hold assets of more than $1 billion. These began reporting on financial risks related to climate change as requested in Budget 2021 or continued to do so if they had already reported on such risks before. We found that the Crown corporations tailored their disclosures to their own mandate and operations. For example, Crown corporations added elements of sustainability reporting in their reporting on strategic priorities and related targets, corporate risks, key activities and investments, and environmental, social, and governance matters.

60. In our review, we did not note any material inconsistencies between the information in their reporting and the audited financial statements.

61. The Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development, a senior official in our office, reports to Parliament on behalf of the Auditor General of Canada on the environmental and sustainable development commitments and activities of federal organizations, as set out in the Auditor General Act. The Commissioner has additional responsibilities set out in various other federal legislation. This work can be found on our website.

Access to justice for all, and building effective, accountable institutions at all levels.

Source: United NationsFootnote 1

62. In addition, our office carries out audit work that supports several of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, including sustainable development target 16.6: “Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels.” We do this by, among other things, providing Parliament with objective, fact-based information and expert advice on government programs and activities gathered through audits. Examples of this audit work include the following:

- financial audits of 69 federal organizations, including the Government of Canada, which are required by legislation to be performed annually

- special examinations of more than 40 federal Crown corporations, as required by legislation every 10 years

- between 10 and 15 performance audits each year reporting on the efficiency and effectiveness of government programs or activities

- audits of Export Development Canada’s Environmental and Social Review Directive, as required by legislation every 5 years

- audits of the Government of Canada’s schedule to allocate the proceeds of green bonds to eligible green projects, as required by Canada’s Green Bond Framework

63. As federal organizations increase their sustainability reporting, we will continue to engage with relevant stakeholders to plan and carry out any required audit work under our mandate.