2024 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of CanadaReport 1—ArriveCAN

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings and Recommendations

- The precise cost of the ArriveCAN application could not be determined

- The Canada Border Services Agency relied heavily on external resources, which increased ArriveCAN’s costs

- Procurement decisions did not support value for money

- The requirements placed on bidders were restrictive and likely limited competition

- Practices to manage ArriveCAN were missing at the most basic levels

- There were deficiencies in the testing of the ArriveCAN application

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- Recommendations and Responses

- Exhibits:

- 1.1—Estimated costs of the main contractors on the ArriveCAN application at 31 March 2023

- 1.2—The Canada Border Services Agency continued to rely heavily on external resources to develop ArriveCAN from April 2020 to March 2023

- 1.3—Under the federal government’s process for task authorization, payments are made to contractors, not subcontractors

- 1.4—The Canada Border Services Agency released 177 versions of ArriveCAN from April 2020 to October 2022

Introduction

Background

1.1 In response to the World Health Organization’s declaration on 11 March 2020 of a global pandemic due to the coronavirus disease (COVID‑19), the Government of Canada introduced measures for travellers entering Canada. As the pandemic evolved, the virus and its variants began to spread quickly around the globe.

1.2 The government issued a series of emergency orders‑in‑councilDefinition 1 that imposed a nationwide mandatory quarantine under the Quarantine Act. Starting on 25 March 2020, a mandatory quarantine required most people who entered Canada to isolate for 14 days and monitor themselves for COVID‑19 symptoms.

1.3 The emergency orders required the Public Health Agency of Canada to collect contact and health information from travellers entering Canada. This was done through the Canada Border Services Agency. At first, border services officers manually collected information in a paper-based form from most people who entered Canada. The information was manually keyed in or digitally scanned by officials before being sent to the Public Health Agency of Canada.

1.4 However, as reported in the 2021 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Report 8—Pandemic Preparedness, Surveillance, and Border Control Measures, this manual paper-based process had limitations. It did not give the Public Health Agency of Canada timely access to contact and health information to identify potential risks. Also, the Canada Border Services Agency indicated that the manual process made it difficult to maintain physical distancing between travellers and border officers.

1.5 In March 2020, in response to the emergency orders and to improve its effectiveness in processing health information collected from travellers, the Public Health Agency of Canada asked the Canada Border Services Agency to develop a digital form to collect the information at the border.

1.6 In the 2021 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Report 15—Enforcement of Quarantine and COVID‑19 Testing Orders—Public Health Agency of Canada, we found that the government improved the quality of the information that it collected and how quickly it was collected by using the ArriveCAN application rather than a paper-based form.

1.7 Before the COVID‑19 pandemic, the Canada Border Services Agency was working with contractors on a proof of conceptDefinition 3 for a low- or no‑touch application that would allow travellers to provide customs information electronically. Some of these contractors also worked on ArriveCAN.

1.8 On 29 April 2020, the Canada Border Services Agency launched a digital application called ArriveCAN—available through the web, iOS, and Android mobile apps—which collected contact and health information from people entering Canada. The application, which was developed using third-party suppliers, allowed the Public Health Agency of Canada to provide contact and health information directly to provinces and territories, to enforce quarantine measures, and to minimize physical contact between travellers and border services officers.

1.9 As the pandemic evolved, the government continued to introduce new emergency orders‑in‑council, some of which required adjustments to the ArriveCAN application. On 1 October 2022, the Government of Canada removed most COVID‑19 entry restrictions, as well as random testing, quarantine, and isolation requirements for anyone entering Canada. Since then, travellers can voluntarily use ArriveCAN to complete their customs and immigration declarations in advance.

1.10 On 2 November 2022, the House of Commons passed a motion that called on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada to conduct a performance audit—including payments made to and contracts and subcontracts awarded to contractors—of the government’s management of the ArriveCAN application.

1.11 Canada Border Services Agency. The agency was responsible for developing and managing the ArriveCAN application on the basis of the Public Health Agency of Canada’s health requirements implemented to meet the emergency orders issued under the Quarantine Act. On 1 April 2022, ownership and responsibilities for ArriveCAN were transferred permanently from the Public Health Agency of Canada to the Canada Border Services Agency.

1.12 Public Health Agency of Canada. The agency assists the Minister of Health in performing duties and functions in relation to public health, including those in relation to the emergency orders issued under the Quarantine Act. The agency was the business owner of ArriveCAN until 1 April 2022. Until the health measures were lifted in October 2022, the agency was also responsible for providing the Canada Border Services Agency with any needed changes to ArriveCAN related to public health.

1.13 Public Services and Procurement Canada. The department supports the Government of Canada by being its central purchasing and contracting authority. It was responsible for issuing and administering contracts on the agencies’ behalf when the contract value exceeded their delegated authority to procure.

Focus of the audit

1.14 This audit focused on whether the Canada Border Services Agency, the Public Health Agency of Canada, and Public Services and Procurement Canada managed all aspects of the ArriveCAN application, including procurement and expected deliverables, with due regard to economy, efficiency, and effectiveness.

1.15 This audit is important because Canadians and the Government of Canada need to know whether public funds are being spent considering value for money.Definition 4 This audit also provides an opportunity for government organizations to learn where they can improve when managing time‑sensitive initiatives or projects that include multiple or complex contracts.

1.16 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings and Recommendations

The precise cost of the ArriveCAN application could not be determined

1.17 This finding matters because the government needs to know how much was spent by responsible organizations on this application and whether they applied the principles of economy, efficiency, and effectiveness in this spending. The government also needs to be transparent and accountable to Canadians with respect to the use of public funds.

Weak financial records and controls

1.18 We found that financial records were not well maintained by the Canada Border Services Agency. We were unable to determine a precise cost for the ArriveCAN application because of poor documentation and weak controls at the Canada Border Services Agency. We estimated that the application cost approximately $59.5 million.

1.19 We found that 18% of invoices submitted by contractors that we tested did not have sufficient supporting documentation to determine whether expenses related to ArriveCAN or another information technology (IT) project. This made it impossible to accurately determine whether costs were attributed to the correct projects.

1.20 Given the shortcomings of the financial records, we built up an estimated cost using the agency’s financial system, contracting documents, and other evidence. It is possible that some amounts attributed to ArriveCAN were not for the application. In some cases, the cost of contracts or task authorizations were specific to ArriveCAN; in others, details were missing or were of a general IT nature, and professional judgment was needed to attribute the cost to the application. Exhibit 1.1 shows the breakdown of our estimated costs for the main contractors at 31 March 2023.

Exhibit 1.1—Estimated costs of the main contractors on the ArriveCAN application at 31 March 2023

| Main contractorsNote 1 | Estimated costs attributable to ArriveCAN (in millions) |

|---|---|

| GC Strategies | $19.1 |

| Dalian Enterprises IncorporatedInc. | $7.9 |

| Amazon Web Services, Inc. | $7.9 |

| Microsoft Canada Inc. | $3.8 |

| TEKsystems, Inc. | $3.2 |

| Donna Cona Inc. | $3.0 |

| Business Development OfficeBDO Canada Limited Liability PartnershipLLP | $2.9 |

| MGIS Inc. | $2.4 |

| 49 Solutions | $1.1 |

| Makwa Resourcing Inc. / The Powell GroupTPG Technology Consulting LimitedLtd. | $1.1 |

| Advanced Chippewa Technologies Inc. | $1.0 |

| OtherNote 2 | $6.1 |

| Total | $59.5 |

|

Source: Based on information provided by the Canada Border Services Agency |

|

1.21 Canada Border Services Agency officials have expressed concerns that $12.2 million of the $59.5‑million estimate could be unrelated to ArriveCAN. We determined, however, that this amount was incurred under ArriveCAN task authorizations.Definition 5 We also noted that a significant portion of these expenses were submitted to a parliamentary committee—the Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates—as ArriveCAN expenses.

1.22 We compared the estimate of $59.5 million with the amounts that the agency provided to the committee. We noted that in the information submitted to the committee, there were instances where costs that we determined were related to ArriveCAN were not included and where some other costs were incorrectly included. In our view, this was a consequence of the poor financial recordkeeping. For example, a resource listed in a task authorization could have worked on multiple projects, not just ArriveCAN.

More included in the development of ArriveCAN than the digital form to collect health information

1.23 We found that the costs of the ArriveCAN application included more than just the digital health form related to the COVID‑19 response. While developing the application, the Canada Border Services Agency added the digitization of the customs and immigration declaration, which had historically been a paper-based system, into the application.

1.24 The following is a breakdown of the estimated $59.5 million in ArriveCAN expenditures:

- $53.3 million—pandemic-response health component

- $6.2 million—customs and immigration declaration form

1.25 After October 2022, the collection of health-related information from travellers at the border ceased to be mandatory. However, travellers could still use ArriveCAN to complete their customs and immigration declarations in advance.

1.26 The Canada Border Services Agency should maintain accurate financial records by correctly allocating expenses to projects. To better support these actions, the agency should work with contractors to obtain invoices that accurately detail the work completed by each resource by project, contract, and task authorization.

The Canada Border Services Agency’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

The Canada Border Services Agency relied heavily on external resources, which increased ArriveCAN’s costs

1.27 This finding matters because determining the right balance between the external and internal resources for a project can greatly affect its cost.

Continued reliance on external resources

1.28 The Canada Border Services Agency determined that it would need to rely on external resources to develop the web‑based and mobile application because it did not have sufficient internal capacity with the skills needed.

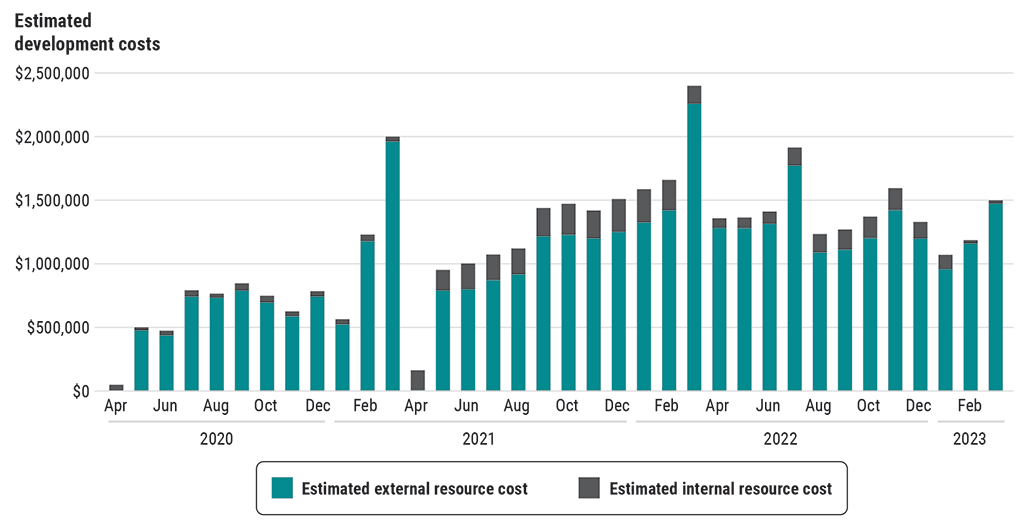

1.29 We found that as time went on, the agency continued to rely heavily on external resources (Exhibit 1.2). Reduced reliance on external resources would have decreased the total cost of the application and enhanced value for money.

Exhibit 1.2—The Canada Border Services Agency continued to rely heavily on external resources to develop ArriveCAN from April 2020 to March 2023

Source: Based on information provided by the Canada Border Services Agency

Exhibit 1.2—text version

This stacked bar chart shows the estimated development costs for the ArriveCAN application for the period of April 2020 to March 2023. Each stacked bar shows the estimated external resource cost and the estimated internal resource cost for each month. The Canada Border Services Agency continued to rely heavily on external resources throughout the period. For example, in May 2020, at the beginning of the period, the estimated external resource cost was $478,628, or 95%, of the total resource cost for that month. However, in March 2023, at the end of the period, the estimated resource cost was $1,479,493, or 98%, of the total resource cost, which was still very high.

The breakdown of the estimated development costs is as follows.

| Month and year | Estimated external resource cost | Estimated internal resource cost |

|---|---|---|

| April 2020 | $0 | $49,248 |

| May 2020 | $478,628 | $25,200 |

| June 2020 | $439,334 | $37,324 |

| July 2020 | $744,349 | $52,347 |

| August 2020 | $735,605 | $34,032 |

| September 2020 | $791,511 | $60,042 |

| October 2020 | $697,391 | $55,725 |

| November 2020 | $589,889 | $39,912 |

| December 2020 | $747,155 | $42,383 |

| January 2021 | $524,928 | $42,675 |

| February 2021 | $1,183,682 | $52,681 |

| March 2021 | $1,970,592 | $40,261 |

| April 2021 | $5,658 | $158,368 |

| May 2021 | $792,425 | $164,838 |

| June 2021 | $804,341 | $203,920 |

| July 2021 | $875,905 | $202,959 |

| August 2021 | $921,550 | $205,013 |

| September 2021 | $1,222,975 | $223,792 |

| October 2021 | $1,233,272 | $247,003 |

| November 2021 | $1,206,917 | $220,204 |

| December 2021 | $1,256,613 | $261,294 |

| January 2022 | $1,330,589 | $265,353 |

| February 2022 | $1,427,640 | $241,292 |

| March 2022 | $2,269,627 | $143,470 |

| April 2022 | $1,288,096 | $77,524 |

| May 2022 | $1,286,963 | $84,370 |

| June 2022 | $1,320,587 | $98,016 |

| July 2022 | $1,781,415 | $143,352 |

| August 2022 | $1,094,047 | $147,007 |

| September 2022 | $1,115,204 | $161,554 |

| October 2022 | $1,208,138 | $170,450 |

| November 2022 | $1,429,336 | $174,664 |

| December 2022 | $1,202,545 | $134,329 |

| January 2023 | $963,086 | $113,161 |

| February 2023 | $1,166,303 | $26,893 |

| March 2023 | $1,479,493 | $28,275 |

1.30 We performed an analysis to identify potential cost savings if the agency had reduced its reliance on external resources over time. We estimated that the average per diem cost for the ArriveCAN external resources was $1,090, whereas the average daily cost for equivalent IT positions in the Government of Canada was $675.

Procurement decisions did not support value for money

1.31 This finding matters because government organizations should ensure that public funds are spent with due regard to economy, efficiency, and effectiveness, including in decisions around the procurement of professional services. While the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat introduced some flexibilities into the procurement and contract processes during the pandemic to achieve results quickly, it still required government organizations to demonstrate due diligence and controls around expenditures and to document their decisions.

1.32 Government organizations use professional services contracts to obtain services of specialists in fields like IT. Such contracts can be awarded using competitive procurement or, in some cases, non‑competitive procurement.

1.33 Given the urgency created by the pandemic, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat encouraged government organizations to focus on results while still demonstrating due diligence and controls on expenditures. To support this direction, the agency invoked exceptions so that certain procurements were not subject to the provisions of the trade agreements and the Government Contracts Regulations and allowed for the consideration of a non‑competitive approach to address urgent needs.

1.34 Normally, government organizations are expected to document the circumstances, rationale, and process of decision making when entering into non‑competitive contracts. This includes documenting communications with potential contractors and how potential contractors are identified and chosen.

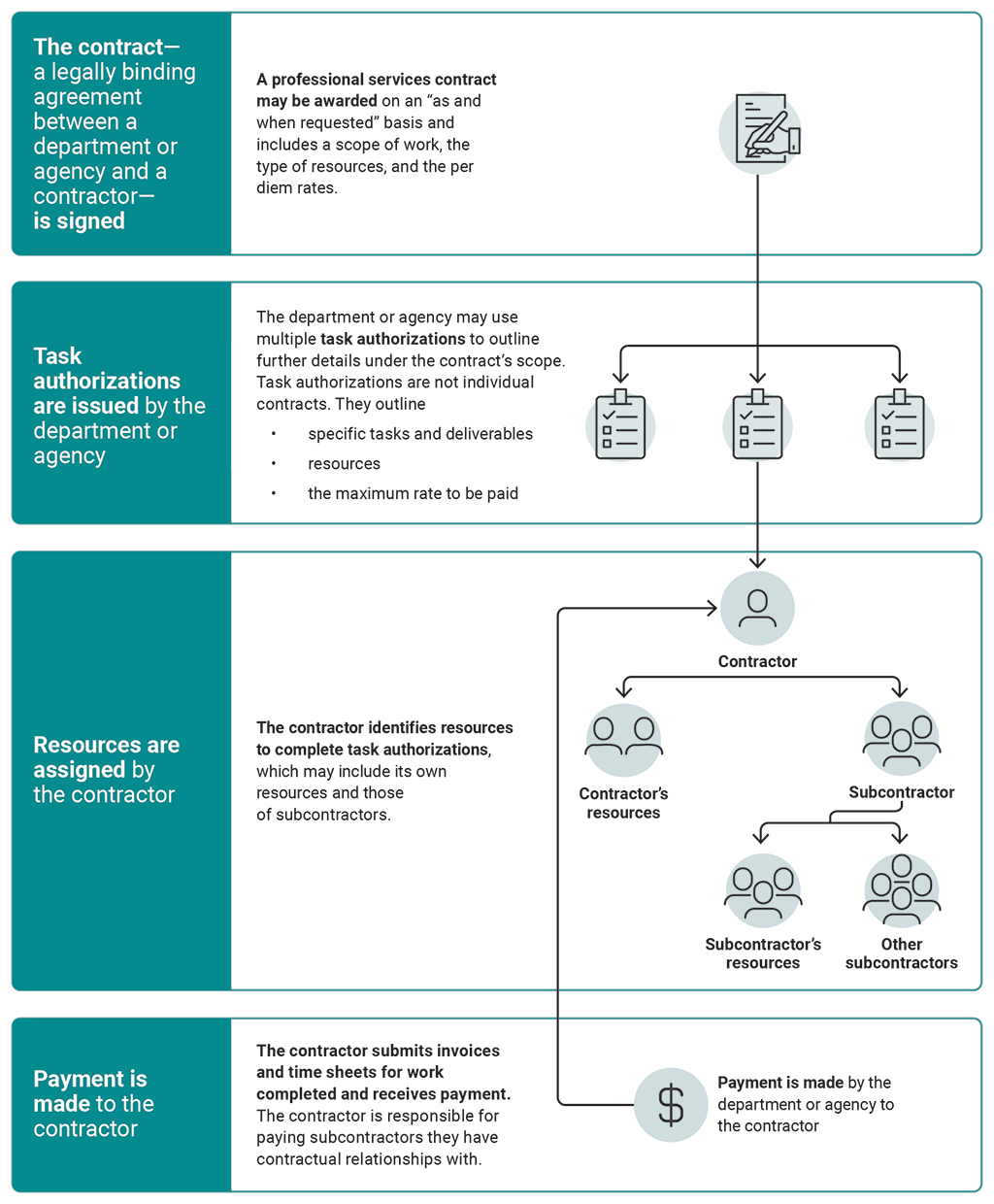

1.35 Professional services contracts are usually structured on an “as and when requested” basis to provide flexibility and quick access to resources. In some cases, these contracts allow the contractor to subcontract work. This means that the specialists doing the work may or may not be employees of the main contractor. Exhibit 1.3 shows the federal government’s process for engaging and paying contractors.

Exhibit 1.3—Under the federal government’s process for task authorization, payments are made to contractors, not subcontractors

Source: Based on information provided by Public Services and Procurement Canada

Exhibit 1.3—text version

This flow chart shows the federal government’s task authorization process, which is as follows.

First, the contract—a legally binding agreement between a department or agency and a contractor—is signed. A professional services contract may be awarded on an “as and when requested” basis and includes a scope of work, the type of resources, and the per diem rates.

Next, task authorizations are issued by the department or agency. The department or agency may use multiple task authorizations to outline further details under the contract’s scope. Task authorizations are not individual contracts. They outline specific tasks and deliverables, resources, and the maximum rate to be paid.

Next, resources are assigned by the contractor. The contractor identifies resources to complete task authorizations, which may include its own resources and those of subcontractors.

Finally, payment is made by the department or agency to the contractor. The contractor submits invoices and time sheets for work completed and receives payment. The contractor is responsible for paying subcontractors they have contractual relationships with.

1.36 The Public Services and Procurement Canada Supply Manual states that using task authorizations mitigates “contractual risks as a result of better-defined tasks, the establishment of a level of effort on a per task basis and more precise pricing for each specific task thereby ensuring better management of the contract.” The daily rates for each resource category are set in the contract. A contract may include the use of multiple task authorizations.

1.37 The “as and when requested” process involves the following steps:

- After identifying a requirement, the government organization sends a draft task authorization to the contractor identifying the resource categories, specific tasks, and the deliverables.

- The contractor responds by proposing a level of effort and resource names and provides documentation that the proposed resources meet the qualifications (for example, under informatics professional services, a level‑2 resource category would require a minimum of 5 years of experience, while a level‑3 resource category would require a minimum of 10 years of experience).

- The government organization assesses the documentation provided by the contractor to ensure that qualifications set out in the contract are met, prior to the approval of the task authorization.

Missing documentation for non‑competitive contracts

1.38 GC Strategies. We found that documentation was missing on the initial discussions and interactions between the Canada Border Services Agency and GC Strategies. These discussions led to the non‑competitive process that resulted in GC Strategies obtaining the first ArriveCAN contract, initially valued at $2.35 million in April 2020.

1.39 The Canada Border Services Agency informed us that GC Strategies was awarded the contract on the basis of a proposal that it submitted. Agency officials told us that they had discussions with 3 potential contractors about submitting a proposal to develop the ArriveCAN application. We found that the agency received a proposal from 1 of the 3 potential contractors, but this proposal was not from GC Strategies. There was no evidence that the agency considered a proposal or any similar document from GC Strategies for this non‑competitive contract.

1.40 We found that the Information, Science and Technology Branch at the Canada Border Services Agency did not support the selection of GC Strategies with a sound justification. Although there was correspondence from the agency to Public Services and Procurement Canada about the selection, we found that the statements made by the agency were not supported by evidence.

1.41 We reviewed available records and could not determine which agency official made the final decision to select GC Strategies. However, the contract requisition to Public Services and Procurement Canada was signed by the Executive Director of the Business Application Services Directorate, which is part of the agency’s Information, Science and Technology Branch. Signing the requisition on behalf of the agency amounts to the exercise of delegated authority and carries with it responsibility and accountability.

1.42 Vendors. We found situations where agency employees who were involved in the ArriveCAN project were invited by vendors to dinners and other activities. The agency’s Code of Conduct requires employees to advise their supervisors of all offers of gifts or hospitality regardless of whether the offer or gift was accepted. We found no evidence that these employees informed their supervisors as required.

1.43 In our view, existing relationships between vendors and the agency’s Information, Science and Technology Branch, as well as the lack of evidence that agency employees reported the invitations to dinners and other activities, created a significant risk or perception of a conflict of interest around procurement decisions.

1.44 The Canada Border Services Agency has launched an investigation into allegations surrounding some employees’ conduct. The investigation was ongoing when we completed our audit. We have also been informed that the agency has referred matters relating to certain employees and contractors to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Because of the nature of the allegations, we did not pursue further audit work around ethics and the Code of Conduct to avoid duplicating or compromising those ongoing processes.

1.45 Other contractors. We found evidence that the Canada Border Services Agency used a non‑competitive approach to award a professional services contract to 49 Solutions. The agency received an unsolicited proposal from this contractor and did not document why it was accepted.

1.46 We also found that the Public Health Agency of Canada awarded a professional services task authorization using a non‑competitive approach to Klynveld Peat Marwick GoerdelerKPMG. We found no documentation of the initial communications or the reasons why the agency did not consider or select other eligible contractors to carry out the work.

1.47 The Canada Border Services Agency and the Public Health Agency of Canada should fully document interactions with potential contractors and the reasons for decisions made during non‑competitive procurement processes and should put in place a process to ensure compliance with the requirements of the contracting policies.

Response of each entity. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Ineffective controls in the contracting process

1.48 We found that the Canada Border Services Agency’s Information, Science and Technology Branch, which led the development of the ArriveCAN application, directly engaged with Public Services and Procurement Canada for contracting purposes. There was no evidence that the agency’s own Procurement Directorate was regularly involved in the contracting process. The directorate has an important challenge function to play in ensuring that key procurement controls are followed and that contracting processes comply with applicable policies and guidelines.

1.49 The Canada Border Services Agency should require that all contracts and task authorizations be reviewed by its Procurement Directorate for compliance with the applicable policies and guidelines. Furthermore, the agency should review the effectiveness of key procurement controls by regularly testing them to ensure that they are working effectively.

The Canada Border Services Agency’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Limited opportunities for competition among professional services vendors

1.50 We found that 3 contractors (GC Strategies, 49 Solutions, and KPMG) were originally awarded professional services work with an original estimated total value of $4.5 million through non‑competitive approaches. Multiple amendments were made to those non‑competitive professional services contracts. Approximately half of the contract amendments extended the contract beyond the original period, which prevented or delayed opportunities for other contractors to compete for work. These amendments also resulted in additional costs. We also found that GC Strategies and KPMG were each awarded 2 additional contracts through non‑competitive approaches. This further limited the opportunities for other contractors to compete for subsequent work.

1.51 We found that Public Services and Procurement Canada, as the government’s central purchasing and contracting authority, challenged the Canada Border Services Agency for proposing and using non‑competitive processes for ArriveCAN and recommended various alternatives. These alternatives included running a shorter competitive process (for example, 10 days) or incorporating shorter contract periods with a non‑competitive approach.

1.52 Despite alternative options proposed by Public Services and Procurement Canada, and statements from Canada Border Services Agency officials that other vendors were capable of doing the work, the agency continued to use a non‑competitive approach.

1.53 We also found a situation where the agency reached out to a firm—one that did not have a contract with the agency—to complete work on ArriveCAN. A few days later, the firm’s resources were added to a task authorization under a contract with GC Strategies. It is unclear why a contract was not issued directly with the firm. By finding the resources itself and having an existing contractor subcontract the work, the agency likely paid more for the resources.

1.54 In addition, we found that the 4 agency contracts that used a non‑competitive approach took between 12 to 63 calendar days from the day Public Services and Procurement Canada received the agency’s request to the day the contract was awarded. In our view, 63 calendar days would have allowed some form of competitive process to be performed as suggested by Public Services and Procurement Canada.

The requirements placed on bidders were restrictive and likely limited competition

1.55 In a competitive procurement process, government organizations prepare a request for proposal to solicit bids for a project or work. The request includes general information about the requirements and the process for selecting a winning bidder. Departments and agencies sometimes seek external help in preparing a request for proposal.

Involvement of the winning bidder in the development of request‑for‑proposal requirements

1.56 We found that GC Strategies was involved in the development of the requirements that the Canada Border Services Agency ultimately included in the request for proposal.

1.57 We found that in May 2022, the agency replaced the 3 non‑competitive contracts held by GC Strategies, which had been issued quickly and urgently, with a competitive contract. This new contract, valued at $25 million, was also awarded to GC Strategies, as it was the only contractor to submit a proposal. In our view, flaws in the competitive processes to award further ArriveCAN contracts raised significant concerns that the process did not result in the best value for money.

1.58 Some of the requirements or eligibility criteria were extremely narrow, which likely prevented competition. For example, bidders were required to have been awarded 3 informatic contracts with the Government of Canada in the last 18 months with a value greater than $10 million. We also found that the reasonableness of per diem rates in the bid was insufficiently assessed. Per diem rates were assessed on the basis of the 3 non‑competitive contracts, which the Canada Border Services Agency had issued during the pandemic. In our opinion, the agency should not have used these prior non‑competitive contracts as a reference point.

1.59 The Canada Border Services Agency should ensure that potential bidders are not involved in developing or preparing any part of a request for proposal and should put in place controls that will prevent this from occurring.

The Canada Border Services Agency’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Practices to manage ArriveCAN were missing at the most basic levels

1.60 This finding matters because government organizations must establish robust management practices to ensure sound project design, implementation, oversight, and accountability.

No governance structure or budget

1.61 We found that from April 2020 to July 2021, when the ArriveCAN application was being developed and regularly updated, no formal agreement existed between the Public Health Agency of Canada and the Canada Border Services Agency on their respective roles and responsibilities. Each agency believed that its counterpart was responsible for establishing a governance structure. In our view, the Public Health Agency of Canada, as the business owner, was responsible for establishing the governance structure.

1.62 As a result of the missing governance structure, good project management practices were not developed and implemented. For example, the Public Health Agency of Canada did not develop project objectives and goals, budgets and cost estimates, assessments of resource needs, or risk management activities.

1.63 A letter of intent between the agencies was signed in July 2021 and was in force until March 2022. The letter clarified responsibilities for funding the development, implementation, management, and support of ArriveCAN.

Failure to properly assess resource qualifications

1.64 We found deficiencies in how the Canada Border Services Agency and the Public Health Agency of Canada managed the experience and qualification requirements of contracts, which raised concerns about value for money. Here are some examples:

- In all non‑competitive contracts, the agencies did not include the experience and qualifications required for resources and, therefore, did not perform formal evaluations of resources. This is important for ensuring value for money.

- For competitive contracts issued by the Canada Border Services Agency, we found cases where the agency did not have evidence to demonstrate that all resources met the contract requirements. In addition, we found that not all of these contracts mentioned the necessary 10 years of experience that is a requirement for level‑3 resource category positions, which is the highest level.

1.65 We found that the Canada Border Services Agency did not have sufficient documentation to support its consistent requests for resources with the highest levels of IT experience—resources that typically charge higher rates—rather than employing a mixture of resources with different levels of experience. In our view, this meant that the agency likely paid for senior resources when work could have been done by resources with less experience that are paid less.

1.66 In addition, in our review of task authorizations that were issued by the Canada Border Services Agency and co‑signed by Public Services and Procurement Canada, we found 2 resources being charged at the rate that required a minimum of 10 years of experience even though the resources did not have this level of experience.

1.67 Finally, we found that the Canada Border Services Agency approved time sheets that included no details on the work completed. This limited the agency’s ability to challenge the contractor’s invoice and, without knowing what work was completed, its ability to allocate the invoice to the right project.

1.68 The Canada Border Services Agency should ensure that professional services contracts and task authorizations specify the required experience and qualifications. In addition, the agency should document its assessment of the qualifications of all proposed resources to ensure that they meet the requirements stated in contracts or task authorizations.

The Canada Border Services Agency’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Lack of clear deliverables and task descriptions

1.69 We found that many of the task authorizations drafted by the Canada Border Services Agency, several of which were co‑signed by Public Services and Procurement Canada, did not include specific and detailed task descriptions and deliverables. This is contrary to the Public Services and Procurement Canada Supply Manual. Without these descriptions, the agency would have had difficulty assessing whether the work was delivered as required and completed on time while providing value for money.

1.70 We found similar issues in the 2 professional services contracts awarded by the Public Health Agency of Canada to KPMG. While the first contract included milestones with clear deliverables and pricing, these were later amended and replaced with less‑specific deliverables to allow for more flexibility. In addition, the agency did not set out specific tasks, levels of effort, and deliverables for these contracts in task authorizations.

1.71 We also found amendments to task authorizations—drafted and signed by the Canada Border Services Agency with many also co‑signed by Public Services and Procurement Canada—that compromised value for money. We found the following:

- Some amendments increased the maximum contract value by increasing the estimated level of effort or extending the time period but without adding new tasks or deliverables.

- Some amendments increased the maximum contract value by adding work to existing task authorizations instead of issuing new ones.

1.72 These approaches to amendments, combined with the deficiencies in drafting contract documents described in paragraphs 1.69 and 1.70, often resulted in increasing the cost without obtaining additional benefits.

1.73 The Canada Border Services Agency and Public Services and Procurement Canada should ensure that tasks and deliverables are clearly defined in contracts and related task authorizations.

Response of each entity. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

There were deficiencies in the testing of the ArriveCAN application

Cybersecurity testing completed by resources not security-cleared or identified on task authorizations

1.74 The Canada Border Services Agency issued 2 task authorizations for cybersecurity assessments of the application under 2 of the GC Strategies contracts valued at approximatively $743,000. The task authorizations required that resources have a reliability security status. We found that security assessments were completed for ArriveCAN in a pre‑development environment by subcontractors under GC Strategies contracts. However, we found that some resources that were involved in the security assessments were not identified in the task authorizations and did not have security clearance. Although the agency told us that the resources did not have access to travellers’ personal information, having resources that were not security-cleared exposed the agency to an increased risk of security breaches.

1.75 In addition, the agency received invoices for resources listed on the task authorizations. However, it was unable to provide any supporting documentation to confirm that work related to the security assessments was performed by 4 of the 5 resources listed. In our view, the agency should have had better oversight of the resources that were completing the work.

1.76 The Canada Border Services Agency should ensure that

- all resources, including contractors and subcontractors, have valid security clearances on file prior to starting any work

- prior to payment, the agency has supporting evidence that confirms and includes the resources’ names, the hours worked, the deliverables on which they worked, and the contracts or task authorizations for the work performed

The Canada Border Services Agency’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Poor documentation of application testing

1.77 We found that between April 2020 and February 2022, there were no documented approvals ensuring that all business requirements were fulfilled prior to the releases of new versions of the ArriveCAN application. The Canada Border Services Agency told us that it understood the risks of emphasizing quick delivery, which meant fewer controls and less documentation around new versions of the application.

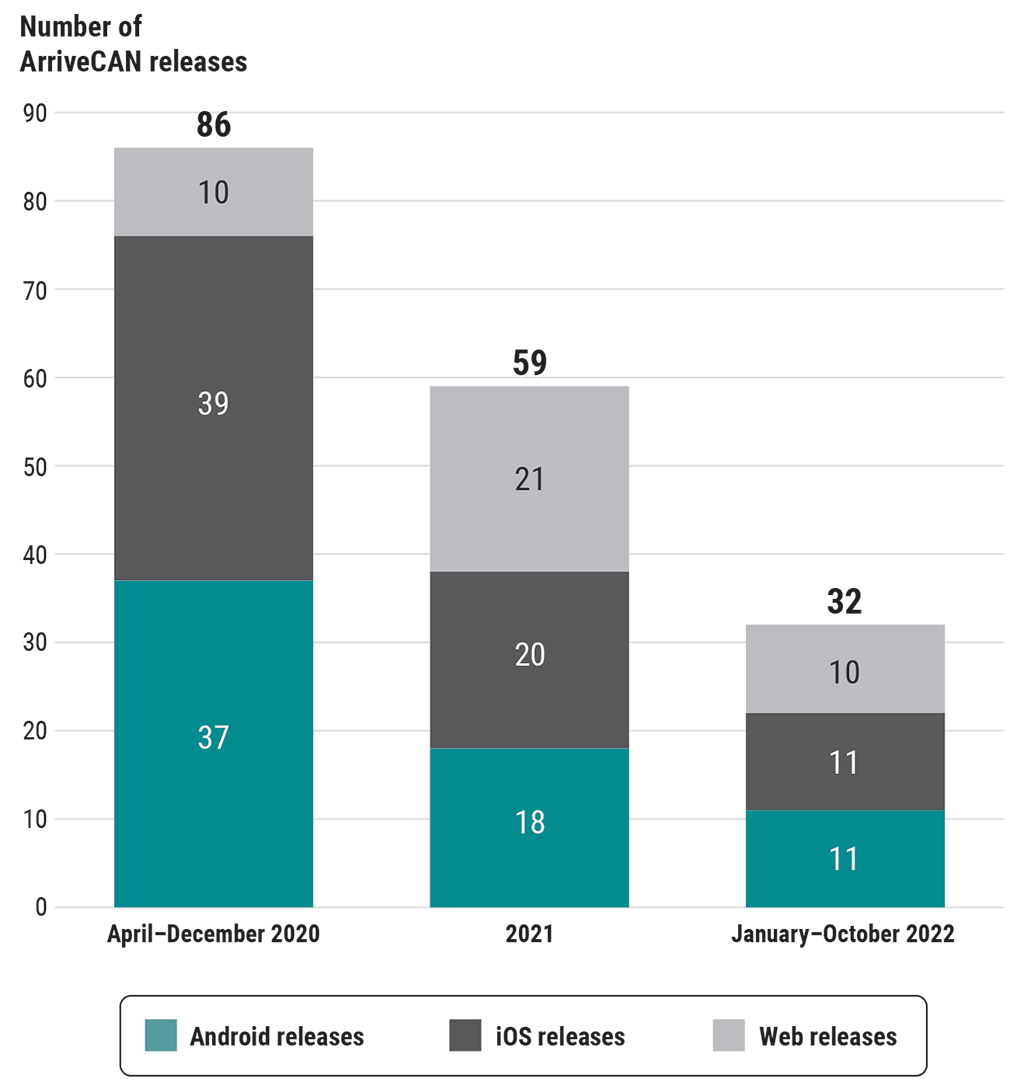

1.78 From the time ArriveCAN was launched in April 2020 until the health requirements were lifted in October 2022, the agency released a total of 177 versions of the application (Exhibit 1.4). A release is when 1 or more changes made to a software are deployed after the application has become available to the people who use the service. Of these 177 releases, 25 were considered major—that is, they included substantial changes.

Exhibit 1.4—The Canada Border Services Agency released 177 versions of ArriveCAN from April 2020 to October 2022

Source: Based on information provided by the Canada Border Services Agency

Exhibit 1.4—text version

This stacked bar chart shows the total number of ArriveCAN releases during 3 periods: April to December 2020, 2021, and January to October 2022. It also shows the number of Android, iOS, and web releases during these periods. The breakdown is as follows.

| Type of release | Number released during the April to December 2020 period | Number released in 2021 | Number released during the January to October 2022 period |

|---|---|---|---|

| Android | 37 | 18 | 11 |

| iOS | 39 | 20 | 11 |

| Web | 10 | 21 | 10 |

| Total | 86 | 59 | 32 |

1.79 We found little documentation showing that the Canada Border Services Agency completed testing prior to releasing new versions of ArriveCAN. There was also a lack of documentation confirming that the Public Health Agency of Canada agreed with the releases while it was the business owner of the application. We reviewed the testing results for the 25 major releases and found the following:

- For 12 out of the 25 major releases, there was no supporting evidence that the Canada Border Services Agency completed user testing.

- Of the remaining 13 releases, 10 had a user testing methodology but had incomplete testing results. Only 3 releases were documented with complete user testing results.

1.80 Without having the assurance that testing was completed, the agencies were at risk of launching an application that might not work as intended. For example, the ArriveCAN release version 3.0, launched on 28 June 2022, wrongly instructed more than 10,000 iOS users who entered Canada between 28 June and 20 July 2022 to quarantine for 14 days, even though they had submitted the required information, including their proofs of vaccination.

1.81 Prior to releasing an application or an update, the Canada Border Services Agency should carry out and document its testing, as well as document results obtained and any outstanding issues, on the basis of the defined roles and responsibilities. The agency should also obtain release approval.

The Canada Border Services Agency’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Conclusion

1.82 Overall, we concluded that the Canada Border Services Agency, the Public Health Agency of Canada, and Public Services and Procurement Canada did not manage all aspects of the ArriveCAN application with due regard to value for money. Deficiencies in contracting and procurement, documentation, and management of deliverables also made it impossible to determine the actual cost of the application.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on ArriveCAN. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs and to conclude on whether ArriveCAN complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements, set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada applies the Canadian Standard on Quality Management 1—Quality Management for Firms That Perform Audits or Reviews of Financial Statements, or Other Assurance or Related Services Engagements. This standard requires our office to design, implement, and operate a system of quality management, including policies or procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether the Public Health Agency of Canada, the Canada Border Services Agency, and Public Services and Procurement Canada managed all aspects of the ArriveCAN application, including procurement and expected deliverables, with due regard to value for money.

Scope and approach

On 2 November 2022, the House of Commons voted on a motion calling on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada to conduct a performance audit of the ArriveCAN application. The scope of the audit was determined by the motion and focused on the overall management of the ArriveCAN application, including procurement and contracting activities, and financial management during the design and implementation phases.

The audit included the following 3 lines of enquiry:

- Overall management. This line of enquiry examined whether a comprehensive management framework was developed and whether general principles for sound management were applied.

- Procurement and contracts. This line of enquiry examined whether procurement and contracting activities were performed according to applicable procedures, guidelines, and policies.

- Management of the deliverables (contract administration). This line of enquiry examined whether the expected deliverables related to the ArriveCAN application were completed according to applicable procedures, guidelines, and policies.

The scope of this audit regarding procurement and contracting activities was based on the mandate of the Office of the Auditor General of Canada. This mandate does not extend to the activities of subcontractors in the context of commercial contracts. This audit did not focus on expected outcomes related to public health and border control.

Note: This audit is about the ArriveCAN application, which is a separate and distinct project from the acquisition of artificial intelligence software to support the Canada Border Services Agency’s workplace harassment strategy.

Criteria

We used the following criteria to conclude against our audit objective:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

In the context of the global coronavirus disease (COVID‑19) pandemic, the Canada Border Services Agency and the Public Health Agency of Canada planned, managed, and monitored the ArriveCAN application with due regard to value for money for Canadians. The Canada Border Services Agency and the Public Health Agency of Canada developed a budget and made reasonable amendments based on changing business requirements. |

|

|

The Canada Border Services Agency managed the procurement and contracting activities according to applicable procedures, regulations, and policies and with due regard to value for money for Canadians. The Public Health Agency of Canada managed the procurement and contracting activities according to applicable procedures, regulations, and policies and with due regard to value for money for Canadians. Public Services and Procurement Canada managed the procurement and contracting activities on behalf of the Canada Border Services Agency and the Public Health Agency of Canada according to applicable procedures, regulations, and policies and with due regard to value for money for Canadians. |

|

|

The Canada Border Services Agency and the Public Health Agency of Canada ensured that expenses made under the ArriveCAN contracts were appropriately substantiated and authorized. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period from 1 January 2019 to 31 January 2023. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies. However, to gain a more complete understanding of the subject matter of the audit, we also examined certain matters that preceded the start date of this period.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 7 February 2024, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

This audit was completed by a multidisciplinary team from across the Office of the Auditor General of Canada led by Sami Hannoush, Principal. The principal has overall responsibility for audit quality, including conducting the audit in accordance with professional standards, applicable legal and regulatory requirements, and the office’s policies and system of quality management.

Recommendations and Responses

In the following table, the paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report.

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

1.26 The Canada Border Services Agency should maintain accurate financial records by correctly allocating expenses to projects. To better support these actions, the agency should work with contractors to obtain invoices that accurately detail the work completed by each resource by project, contract, and task authorization. |

The Canada Border Services Agency’s response. Agreed. As a first step to ensure consistency across all procurement, the Canada Border Services Agency’s Procurement function was centralized and regrouped under 1 organization, the agency’s Procurement Directorate. The agency also launched a comprehensive improvement plan to further strengthen management controls at all levels across the agency and improve governance across the Procurement function. To address this recommendation and prevent similar occurrences in the future, the agency will

The agency will ensure compliance with procurement processes and the consistent application of the new guidance, including the work completed by each resource, which will be assessed and reported on as part of the new Assurance Reviews, by 31 July 2024. |

|

1.47 The Canada Border Services Agency and the Public Health Agency of Canada should fully document interactions with potential contractors and the reasons for decisions made during non‑competitive procurement processes and should put in place a process to ensure compliance with the requirements of the contracting policies. |

The Canada Border Services Agency’s response. Agreed. The Canada Border Services Agency’s improved governance over procurement includes a new Contract Review Board to review and approve contracts and task authorizations. Recognizing the need to ensure sound stewardship of public funds, the new governance structure will provide additional oversight on all contracting activities, focusing on delivering value for money and alignment with procurement and project management policies. To support the integrity in contracting activities, the agency will implement a requirement for staff to report interactions with potential vendors by 31 March 2024. The Procurement Directorate will also ensure compliance by acting as the single window for interactions with vendors in the context of the procurement process. It will also monitor compliance by developing regular risk‑based reviews of contracting files. The new Assurance Program in 2024–25 will ensure the consistent application of the new guidance by reviewing the documentation held in the procurement files. The results of the Assurance Reviews will be presented to the Executive Committee on a quarterly basis, starting 31 July 2024. The Public Health Agency of Canada’s response. Agreed. The Public Health Agency of Canada will update guidance and/or checklists with respect to file documentation, noting requirements to document interactions with potential contractors. The agency expects this action to be implemented by 30 June 2024. The agency will review the current process in place to ensure compliance with file documentation as per the Treasury Board Directive on the Management of Procurement. The agency expects this action to be implemented by 31 October 2024. |

|

1.49 The Canada Border Services Agency should require that all contracts and task authorizations be reviewed by its Procurement Directorate for compliance with the applicable policies and guidelines. Furthermore, the agency should review the effectiveness of key procurement controls by regularly testing them to ensure that they are working effectively. |

The Canada Border Services Agency’s response. Agreed. The Canada Border Services Agency has strengthened its Procurement Directorate to enable more effective oversight of all contracting activities in the agency. This includes ensuring that all procurement actions are flowed through the Procurement Directorate. The agency has created a new Contract Review Board with responsibility for reviewing and approving contracts and task authorizations, which will also help to ensure that all procurement activities are being managed through the Procurement Directorate. The new Assurance Program in 2024–25 will ensure the consistent application of the new guidance and the documentation held in the procurement files. The results of the Assurance Reviews will be presented to the Executive Committee on a quarterly basis, starting 31 July 2024. |

|

1.59 The Canada Border Services Agency should ensure that potential bidders are not involved in developing or preparing any part of a request for proposal and should put in place controls that will prevent this from occurring. |

The Canada Border Services Agency’s response. Agreed. All headquarters staff with procurement responsibilities have completed 4 training courses to help remind them of their responsibilities and the processes required of them. The Procurement Directorate will help prevent occurrences of vendors participating in pre‑contractual conversations by acting as the single window for interactions with vendors in the context of the procurement process. In addition, to support the integrity of contracting activities, the Canada Border Services Agency will implement a requirement for staff to report interactions with potential vendors, by 31 March 2024. Further, employees with procurement responsibilities will be required to attend a Code of Conduct and Values and Ethics awareness session to ensure a clear understanding of expectations to minimize potential apparent and real conflicts of interest. The awareness session will address relevant procurement-related ethical scenarios. The Procurement Directorate has created a new Centre of Expertise, which will provide regular engagement sessions for managers to remind them of their responsibilities relating to procurement by 30 September 2024. |

|

1.68 The Canada Border Services Agency should ensure that professional services contracts and task authorizations specify the required experience and qualifications. In addition, the agency should document its assessment of the qualifications of all proposed resources to ensure that they meet the requirements stated in contracts or task authorizations. |

The Canada Border Services Agency’s response. Agreed. The Procurement Directorate has updated and communicated its new guidance to help strengthen the controls and document each step, including the need for technical authorities to assess qualifications in a consistent manner, including the experience that is required, and that the results must be recorded in the contract award requested and the procurement file. The new Contract Review Board is responsible for approving all contracts and task authorizations at each stage of the procurement process, covering the procurement strategy, project initiation, and at contract award, which will include a review of the professional services experience and qualifications requirements. Regular information workshops will be offered to ensure that existing and especially new managers and employees are up to date on procurement-related expectations, starting 30 September 2024. |

|

1.73 The Canada Border Services Agency and Public Services and Procurement Canada should ensure that tasks and deliverables are clearly defined in contracts and related task authorizations. |

The Canada Border Services Agency’s response. Agreed. The Procurement Directorate has updated and communicated its new guidance that sets out which actions are required to fully document each step in the procurement process, including the need to ensure that tasks and deliverables are clearly defined in contracts and task authorizations, and that they are correctly recorded in the contract award request and the procurement file. To ensure compliance with the procurement processes, the new Contract Review Board is responsible for approving contracts and task authorizations at each stage, covering procurement strategy, project initiation, and at contract award, which will include assurance that the tasks and deliverables are clearly defined in the contracts. Public Services and Procurement Canada’s response. Agreed. Public Services and Procurement Canada has already taken action. The department has provided direction, in a 4 December 2023 communiqué, to procurement staff to ensure that task authorizations include clear tasks and deliverables, in addition to identifying the specific project(s) or initiative(s) that are included in the scope of contracts. Additionally, Public Services and Procurement Canada sent a directive to its client departments, via their senior designated officials for procurement, indicating this change was immediately being brought into effect for professional services contracts, as of 8 November 2023. The department will also update the Guide to Preparing and Administering Task Authorizations as well as the Record of Agreement template for clients. |

|

1.76 The Canada Border Services Agency should ensure that

|

The Canada Border Services Agency’s response. Agreed. The Procurement Directorate has updated and communicated its guidance to document each step in the procurement process, including the need to confirm that resources meet the security requirements, and the need to confirm that the resource’s name, hours worked and contractual details are correct. The results of those reviews must be documented in the procurement file. The Canada Border Services Agency will ensure compliance with procurement processes and the consistent application of the new Standard Operating Procedures will be assessed and reported on as part of the new Assurance Reviews, starting 1 April 2024. The agency’s finance team will improve how it meets its Section 33 responsibilities under the Financial Administration Act by increasing its testing on the documentation provided before payments on contract are made, by 30 September 2024. |

|

1.81 Prior to releasing an application or an update, the Canada Border Services Agency should carry out and document its testing, as well as document results obtained and any outstanding issues, on the basis of the defined roles and responsibilities. The agency should also obtain release approval. |

The Canada Border Services Agency’s response. Agreed. The Vice‑President, Information, Science and Technology Branch, recognizes that, given the constantly evolving pandemic environment and the requirement for 177 releases in 36 months, testing documentation was insufficient during ArriveCAN development. It was not feasible to complete all testing documentation as per existing procedures in this emergency environment. A procedure for streamlined testing documentation will be developed and implemented that will increase agility in emergency situations while at the same time ensuring sufficient controls are in place to document testing results prior to release to production. In addition, the Information, Science and Technology Branch will review and update existing testing procedures to ensure control steps are introduced and documentation is complete before any system or application is released to production. These actions will be completed by June 2024. |