Impacts and results

Introduction

1. This report highlights the results of the financial audits we—the Office of the Auditor General of Canada—conducted in federal organizations for fiscal years ended between July 2020 and April 2021. (We refer to these as the 2020–2021 financial audits.) This report provides a commentary based on those audit results. We also provide additional insights on 2 areas from our financial audits: cybersecurity and advancing the use of data.

2. New this year is our reporting on the financial effects of the coronavirus disease (COVID‑19)Definition 1 pandemic on the consolidated financial statements of the Government of Canada. More specifically, this report provides

- the results of our audit of the consolidated financial statements, which contain a significant amount of new spending in response to the pandemic

- the results of our audit work in response to Parliament’s motion asking us to carry out additional audit work on some of the spending (see paragraph 6)

- a summary of the measures under the government’s economic response to COVID‑19 and where the measures are reported in the consolidated financial statements

3. This commentary is not a performance audit; we do not provide an opinion on the government’s COVID‑19 economic response. We have conducted and will continue to conduct performance audits on some of these measures. Those performance audits are presented in separate reports.

The Government of Canada’s COVID‑19 economic response

4. When the economy took a downturn after the COVID‑19 pandemic hit in March 2020, the government took many budgetary, non-budgetary, and fiscal measures to support affected individuals, businesses, and the provinces and territories (Appendix A). Parliament passed several new acts and amended existing ones to, among other things, authorize the spending of public funds on these emergency measures (Appendix B). These measures—of an unprecedented size and scope—increased the government’s program expenses by 69% from the previous fiscal year.

5. Canada’s response to the pandemic, the COVID‑19 Economic Response Plan, also involved monetary policy and macro-prudential measures intended to support the economy. Among other measures, the Bank of Canada injected liquidity in the financial markets, such as by buying government bonds and corporate bonds. The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada introduced measures to support the operational and financial resilience of banks, insurers, and pension plans.

6. In April 2020, Parliament passed a motion asking the Auditor General to audit spending authorized by parts of the COVID‑19 Emergency Response Act. As part of our audit of the government’s consolidated financial statements, we audited the major spending and verified that the government had complied with legislation. We also conducted performance audits on specific COVID‑19 measures under this act and on other topics. Before we could present our results of this work, Parliament was dissolved on 15 August 2021, and the motion did not survive the dissolution. However, we report our findings on this work because of the extraordinary circumstances involved in approving spending of public funds, and because the amounts were significant. We will continue to audit COVID‑19 measures through annual financial audits and additional performance audits because some measures continue to be significant and will span over more than 1 year.

7. The transactions arising from the COVID‑19 Economic Response Plan were reported in both the financial statements of federal organizations and the Public Accounts of Canada. Every year, our office audits these financial statements, except those of the Bank of Canada and the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. (See “Results of our 2020–2021 financial audits.”) Our independent audit opinion on each of these financial statements is required by law and contributes to the credibility of the information in these statements, enhances transparency, and supports continuous improvement.

8. An overview of the measures in the COVID‑19 Economic Response Plan is in Exhibit 1. We present the following information on these measures, and describe the audit work we have done on the 2020–2021 financial audits, to help parliamentarians exercise oversight of government finances.

Exhibit 1—Overview of the government’s COVID‑19 economic response

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of the Government of Canada’s COVID‑19 Economic Response Plan

Exhibit 1—text version

This flow chart shows an overview of the Government of Canada’s economic response to the coronavirus (COVID‑19) pandemic.

The following measures are authorized under new legislation:

- direct support measures for individuals

- direct support measures for businesses, and loans and liquidity supports

- protecting health and safety

The following measures are authorized under existing legislation and mandate:

- The Bank of Canada lowered interest rates and purchased government and commercial bonds.

- The Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada introduced measures.

The measures that were authorized under existing legislation and mandate increased liquidity and banks’ lending capacity to help markets function.

9. During the 2020–21 fiscal year, the government spent or loaned approximately $300 billion for

- measures to protect health and safety

- measures to directly support individuals and businesses

- other liquidity supports for businesses

(A more detailed list of measures is in Appendix A.)

10. The pandemic had other effects on the government’s finances that are not included in these totals, such as

- reduced revenues from income taxes, sales taxes, customs duties, and other revenue sources as a result of slowdowns in the economy

- loss of federal employee productivity or employee overtime pay

- costs to equip federal workers for remote work or to adapt federal workplaces to follow public health directives, including providing on-site workers with personal protective equipment

Those additional effects were nevertheless accounted for, but are not presented separately, in the financial statements of federal organizations.

11. The government spent approximately $244 billion on direct support measures for individuals and businesses and on protecting health and safety (Exhibit 2). The direct support measures for individuals included the Canada Emergency Response Benefit, which provided a $500 weekly benefit for workers who were unable to work as a result of the pandemic. The direct support measures for businesses included the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy, which initially paid employers up to $847 weekly per employee to subsidize wages.

Exhibit 2—Breakdown of $243.7 billion total spent on COVID‑19 direct support for individuals and businesses and on protecting health and safety

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of data in the Government of Canada’s consolidated financial statements and of the estimated expenditures for the 2020–21 fiscal year reported by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates

Exhibit 2—text version

This bar chart shows the breakdown of the $243.7 billion total spent in the 2020–21 fiscal year on COVID‑19 direct support measures for individuals and businesses and on protecting health and safety measures.

The total amount spent on direct support measures for individuals in the 2020–21 fiscal year was $102.3 billion. This consisted of $63.7 billion for the Canada Emergency Response Benefit, $14.4 billion for the Canada Recovery Benefit, and $24.2 billion for other transfers and expenses.

The total amount spent on direct support measures for businesses in the 2020–21 fiscal year was $110.0 billion. This consisted of $80.2 billion for the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy and the Temporary Wage Subsidy, $13.1 billion for the Canada Emergency Business Account incentive, and $16.7 billion for other transfers and expenses.

The total amount spent on protecting health and safety measures in the 2020–21 fiscal year was $31.4 billion. This consisted of $15.9 billion for the Safe Restart Agreement and $15.5 billion for other transfers and expenses.

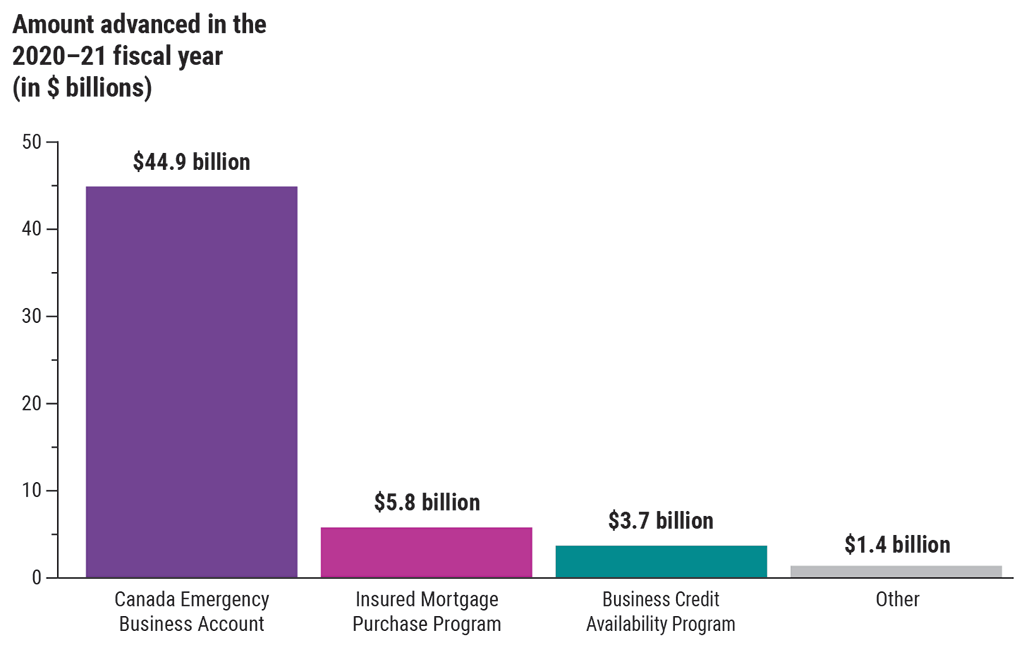

12. As further supports to businesses, the government and several Crown corporations provided approximately $56 billion in loans and other liquidity supports (Exhibit 3). Here are some examples:

- The Canada Emergency Business Account program provided up to $60,000 in interest-free loans to small and medium-sized businesses, and not-for-profits, of which up to $20,000 is forgivable on certain conditions.

- Through the Business Credit Availability Program, Crown corporations partnered with financial institutions and jointly provided loans and guarantees to businesses and offered flexible repayment terms.

- The Insured Mortgage Purchase Program allowed the government to purchase insured mortgage pools through the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, which provided liquidity to financial institutions so that they could continue to offer credit to businesses.

Exhibit 3—Breakdown of the $55.8 billion advanced as COVID‑19 loans and other liquidity supports to businesses

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of data in the Government of Canada’s consolidated financial statements and in the financial statements of Crown corporations

Exhibit 3—text version

This bar chart shows the breakdown of the $55.8 billion that was advanced in the 2020–21 fiscal year as COVID‑19 loans and other liquidity support to businesses. The amount advanced for the Canada Emergency Business Account was $44.9 billion. The amount advanced for the Insured Mortgage Purchase Program was $5.8 billion. The amount advanced for the Business Credit Availability Program was $3.7 billion. The amount advanced for other supports was $1.4 billion.

13. Some of the loans and liquidity supports have been repaid by the businesses, and some programs have closed or are winding down. Loans or liquidity supports that have not yet been repaid by businesses are reported as assets in the financial statements of the respective Crown corporations or, in the case of the Canada Emergency Business Account program, in the government’s consolidated financial statements. The value of these assets is reduced when a loan is determined to be unlikely to be repaid or in order to reflect amounts that are likely to be forgiven. This reduction in the value of assets increases the annual deficit.

14. To provide Crown corporations the funding needed to carry out these programs, the government either made investments by purchasing additional shares of these corporations or lent them funds under the existing consolidated borrowing framework. This is the usual mechanism for borrowing by enterprise Crown corporations. These Crown borrowings are included in the government’s borrowing limit, which is set out in legislation.

15. To raise funds to implement the budgetary and fiscal measures in its COVID‑19 Economic Response Plan, the government issued debt on the financial markets, such as Government of Canada bonds and treasury bills. Issuing debt is one mechanism the government can use to fund additional public spending; the other main one is raising taxes. The debt is reported by the government in its consolidated financial statements as unmatured debt.

16. The total unmatured debt on the government’s statement of financial position rose from approximately $784 billion to $1.125 trillion in the 2020–21 fiscal year. The public debt charges related to unmatured debt decreased from $18 billion to $15 billion, despite the increased level of debt, because of the low cost of borrowing in that year. As part of our audit of the government’s consolidated financial statements, we audited these debt levels and related interest costs. The additional borrowing to fund the COVID‑19 Economic Response Plan will increase the future repayments, and these will be affected by interest rates, which may change. The Financial Administration Act requires the Minister of Finance to present a report annually to Parliament on the government’s management of public debt.

17. In addition to the measures above, the Bank of Canada took a variety of actions intended to support the economy and inject liquidity in the financial markets. The bank has the legislative authority to take certain actions it determines are needed to promote the stability of the Canadian financial system. It lowered the policy interest rate over several weeks in March 2020 to 0.25%, from a pre-pandemic level of 1.75%. This move was intended to help individuals and businesses by lowering interest payments on existing and new loans.

18. Other measures the Bank of Canada took were the following:

- It bought large amounts of assets, such as federal and provincial government bonds and corporate bonds, as stimulus intended to help circulate more money in the economy and enable freer trading in financial markets. In terms of federal government bonds, the bank purchased them from a variety of bondholders, such as private investors and pension funds. Because these bonds’ values had increased on the market, the bank bought them at a price that was more than the value that the bonds were accounted for by the Government of Canada. (The impact of this transaction on the government’s consolidated financial statements is explained in paragraphs 24 and 25.)

- It enhanced some of its standard liquidity tools to provide ready access to funding to financial institutions. It lengthened the term over which it lends money to banks, widened the collateral it accepts to provide lending, and expanded the list of eligible institutions that can access its lending.

19. Lowering the policy interest rate did not have a direct impact on the Bank of Canada’s statement of financial position, but both the enhanced liquidity tools and the asset purchases did. Before the pandemic, the bank’s total assets were approximately $120 billion. At its peak, in March 2021, the bank’s total assets reached approximately $575 billion. As at 1 September 2021, these assets totalled approximately $488 billion. The bank expected to continue adjusting the amount of stimulus on the basis of its ongoing assessment of the strength and durability of the economic recovery. The bank’s financial statements are audited by 2 independent accounting firms. More information on the Bank of Canada’s activities is available on its website.

20. Additionally, the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada took several measures that supported banks, insurers, and pension plans. It is an independent federal government agency that regulates and supervises federally regulated financial institutions and pension plans. It determines whether they are in sound financial condition and meeting regulatory requirements.

21. Its measures did not involve spending public funds. As one measure that helped supply credit to the economy, it lowered the level of its domestic stability buffer—a buffer of capital that the largest banks are required to build in good times so they have more lending capacity in times of economic stress. It lowered the buffer from 2.25% of a bank’s risk-weighted assets to 1.00% in March 2020 to support approximately $300 billion of additional lending capacity by banks. In June 2021, it increased the level of the buffer to 2.50%, effective 31 October 2021. It did this to respond to continued vulnerabilities in the financial system, such as elevated levels of household and corporate debt, while recognizing that economic and financial market conditions had improved. Its financial statements are audited by an independent accounting firm. More information on the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada’s activities is available on its website.

22. As part of our audit of the government’s consolidated financial statements, and to respond at the time to the April 2020 motion from Parliament, we performed the following work:

- We examined the list of measures related to part 3 of the COVID‑19 Emergency Response Act (included in Appendix A) to determine whether the act’s requirements were met before public funds were spent. Specifically, concurrence must be obtained from relevant federal ministers to approve spending. The concurrence records were critical because they were the key control for the authorization of spending of public funds, which is typically provided by Parliament.

- We audited the spending on the measures related to part 3 of the COVID‑19 Emergency Response Act, on a sample basis, to determine whether the amounts were recorded accurately and completely in the financial statements.

- We verified, as applicable, whether actions taken by the government had complied with the sections of the Financial Administration Act and Borrowing Authority Act that were enacted by part 8 of the COVID‑19 Emergency Response Act, including requirements to report to Parliament on the government’s borrowings.

- We also conducted performance audits of the Canada Emergency Response Benefit and other COVID‑19 measures.

23. On the basis of our audit work, we found that the government’s spending related to part 3 of the COVID‑19 Emergency Response Act, in all material respects, was authorized and was reported accurately and completely in the financial statements. We also found that the government’s actions related to the amended provisions of the Financial Administration Act and the Borrowing Authority Act that were enacted by part 8 of the COVID‑19 Emergency Response Act complied, in all material respects, with the legislation.

24. The transactions arising from the budgetary, non-budgetary, and fiscal measures to respond to COVID‑19 are reported in the government’s consolidated financial statements and in the financial statements of several Crown corporations:

- Direct support measures for individuals and businesses and measures for protecting health and safety (Exhibit 2) were mainly reported in the government’s revenues and expenses.

- Loans and liquidity supports (Exhibit 3) were reported either in the government’s assets or in the assets of Crown corporations in their individual financial statements, depending on the program. Estimated amounts for forgiven loans or credit losses were reported as an expense.

- The funding that the government provided to Crown corporations and their financial performance was reported in the government’s statements as an increase or decrease to the government’s investment.

- The purchase of federal government bonds by the Bank of Canada resulted in a net loss of $19 billion reported in the government’s other revenues from enterprise Crown corporations and other government business enterprises, and in an equivalent decrease in the government’s investment in the Bank of Canada.

- Issuance of debt was reported as an increase in unmatured debt in the government’s liabilities.

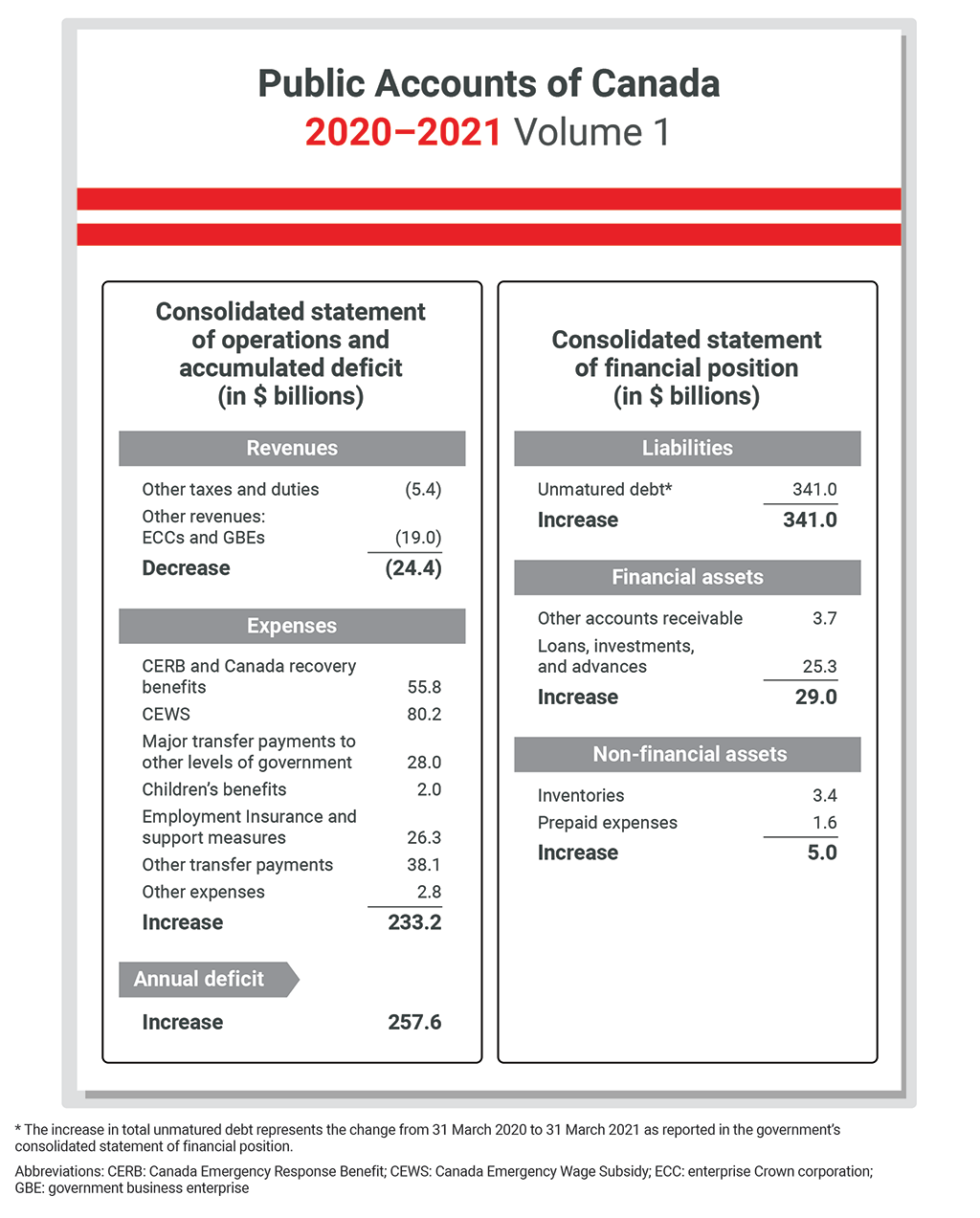

25. As at 31 March 2021, the overall impact of these COVID‑19 measures on the Government of Canada’s consolidated financial statements was approximately a

- $24-billion decrease in revenue (due to the Bank of Canada’s purchase of federal government bonds and due to the enhanced goods and services tax / harmonized sales tax credit to individuals)

- $233-billion increase in expenses

- $341-billion increase in liabilities

- $29-billion increase in financial assets (mainly due to loans advanced under the Canada Emergency Business Account program and to other transactions relating to Crown corporations) and a $5‑billion increase in non‑financial assets

- net $258-billion increase in the annual deficit

The transactions resulting from the COVID‑19 measures of individual Crown corporations are reported in their respective financial statements. The net effects of these transactions are subsequently reported in the government’s consolidated financial statements.

26. Exhibit 4 shows where these budgetary, non-budgetary, and fiscal measures were reported in the consolidated financial statements. The government provided more information in the financial statements discussion and analysis and in the note disclosures accompanying the consolidated financial statements.

Exhibit 4—Where the overall effects of the COVID‑19 measures and the total increase of unmatured debt were reported in the government’s consolidated financial statements

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of data in the Government of Canada’s consolidated financial statements and in the financial statements of Crown corporations and of the estimated expenditures for the 2020–21 fiscal year reported by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates

Exhibit 4—text version

Consolidated statement of operations and accumulated deficit (in $ billions)

| Other taxes and duties | (5.4) |

| Other revenues: enterprise Crown corporations and government business enterprises |

(19.0) |

| Decrease | (24.4) |

| Canada Emergency Response Benefit and Canada recovery benefits | 55.8 |

| Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy | 80.2 |

| Major transfer payments to other levels of government | 28.0 |

| Children’s benefits | 2.0 |

| Employment Insurance and support measures | 26.3 |

| Other transfer payments | 38.1 |

| Other expenses | 2.8 |

| Increase | 233.2 |

| Increase | 257.6 |

Consolidated statement of financial position (in $ billions)

| Unmatured debtNote * | 341.0 |

| Increase | 341.0 |

| Other accounts receivable | 3.7 |

| Loans, investments, and advances | 25.3 |

| Increase | 29.0 |

| Inventories | 3.4 |

| Prepaid expenses | 1.6 |

| Increase | 5.0 |

27. On the basis of our audit, we found that the government properly accounted for COVID‑19 measures, in all material respects, in its consolidated financial statements. In addition, this year, our independent auditor’s report on the government’s consolidated financial statements included an emphasis of matter paragraph. We did this to draw attention to certain amounts in, and notes to, the consolidated financial statements that described the effects of the COVID‑19 pandemic on the Government of Canada, which were significant. This paragraph does not modify our audit opinion.

28. Some measures, such as the Canada Emergency Response Benefit, the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy, and the Canada Recovery Benefit, were designed to deliver benefits to Canadians quickly. The government paid benefits to individuals or businesses once they attested that they met the eligibility criteria. As a result, there is a risk of overpayments of benefits whether due to errors or fraud. To address this risk, post-payment verifications are required to identify any overpayments. The amounts to be recovered related to these overpayments are reported in the consolidated financial statements in the year the overpayments are determined. For some measures, the government has begun to carry out post-payment verification to identify overpayments. It expects its post-payment verification to continue for several years.

29. For the Canada Emergency Response Benefit, as at 31 March 2021, the government recognized accounts receivable from overpayments of $3.7 billion. As described in the notes to the consolidated financial statements, an allowance for doubtful accounts is recorded where collection efforts are unlikely to be successful. The government will determine annually the amount of additional overpayments, as well as any allowance for doubtful accounts.

30. Some measures require estimates to be made about the future repayments of loans, which were reported in the 2020–21 consolidated financial statements and will continue to be reported in future years. For example, as a support to businesses, the Canada Emergency Business Account program advanced interest-free loans to businesses that included a repayment incentive of a loan forgiveness of up to $20,000 if the loan is repaid by 31 December 2022. As at 31 March 2021, the government expected to forgive $13.1 billion of the loans. This reduced the government’s assets and increased the government’s expenses for the 2020–21 fiscal year. The government will update annually its estimate of forgiven loans until the 2022–23 fiscal year, when the repayment date passes and the exact amount of forgiven loans is determined.

31. In addition to amounts forgiven, there is a risk that some businesses may be unable to repay their loans, resulting in losses for the government and federal organizations. It is the practice of federal organizations to assess this risk and recognize a provision for expected credit losses as an expense in their financial statements. The government and Crown corporations will update annually these provisions for credit losses.

Results of our 2020–2021 financial audits

32. The Office of the Auditor General of Canada provided the Government of Canada with an unmodified audit opinion on its 2020–21 consolidated financial statements. This year, as a result of a subsequent event, the government amended its 2020–21 consolidated financial statements after it had approved them but before they were tabled in Parliament. The government described this subsequent event in note 22 of its consolidated financial statements. As a result, our unmodified audit opinion contains 2 dates. The first date applies to the audit work we performed up to the original approval of the consolidated financial statements. The second date applies only to the work we performed on the amendments made by the government with respect to the subsequent event. Our audit opinion provides credibility to the government’s financial reporting. Financial reporting is one way the government demonstrates accountability to elected officials and the public. The audit opinion is also an important contribution to meeting Canada’s commitments under the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. In particular, the opinion helps Canada meet Sustainable Development Goal target 16.6: “Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels.”

33. The list of government organizations we audit has changed over time. We no longer audit Ridley Terminals IncorporatedInc., because it was sold in December 2019 and is no longer a Crown corporation. We were appointed joint auditors of the Canada Enterprise Emergency Funding Corporation, a new federal Crown corporation incorporated in May 2020 as a wholly owned subsidiary of the Canada Development Investment Corporation. For more information about the government organizations we audit, see the Background to the Commentaries on Financial Audits page on our website.

34. Overall, we were satisfied with the timeliness and credibility of the financial statements prepared by 68 out of the 69 government organizations we audit, including the Government of Canada.

35. Because of National Defence’s ongoing challenges in providing the documentation to support the estimated pension obligations, we could not issue our audit opinion on the department’s Reserve Force Pension Plan on a timely basis. In the last 2 fiscal years, National Defence contacted reserve bases and individual reservists and deployed a significant amount of resources to gather all the required documents. National Defence’s ongoing efforts to gather the supporting information resulted in our being able to complete the audit and issue our auditor’s report on the 31 March 2018 financial statements of the Reserve Force Pension Plan in February 2021. This was a significant achievement for the department. We expect to complete the audits of the 31 March 2019 and 31 March 2020 financial statements by January 2022 and the 31 March 2021 and 31 March 2022 audits by January 2023. After that, we expect the financial statements of the Reserve Force Pension Plan to be prepared on a timely basis, which would enable us to issue our auditor’s report on a timely basis.

36. In last year’s commentary, we reported on new challenges that emerged in 2020 for our financial audits as a result of the COVID‑19 pandemic. These challenges included the need to find new ways to manage the audit process remotely and to perform additional work in higher-risk areas.

37. Our work increased in part because of the increase in government spending in response to the pandemic, which had significant effects on the financial statements of federal organizations. The following are examples of how we adapted our audit work:

- We hired contractors in certain regions to perform on-site audit work, such as inventory count procedures, because of travel restrictions.

- We gained an understanding of new or modified business processes and controls implemented by federal organizations. If certain business processes were not supported by sufficiently strong controls, we performed additional verifications before relying on data, which is our standard practice.

- We increased our audit work as a result of new amounts of assets, liabilities, revenue, or expenses reported in the financial statements and disclosures in the notes to the financial statements.

- We considered whether new activities carried out by federal organizations during the pandemic were authorized by their respective legislative mandates and authorities.

We carried out sufficient and appropriate audit work on which to base our conclusions. As a result of the significant collaboration with federal organizations, we completed our audits on a timely basis, which enabled organizations to meet their financial reporting deadlines.

38. In our commentary on the 2018–2019 financial audits, we reported that timely decisions on corporate plans were a problem in 10 of 35 Crown corporations we audited. In this report, we provide an update on the timeliness of approvals of corporate plans.

39. Crown corporations operate at arm’s length from the government under Part X of the Financial Administration Act. As an important step in their accountability to their shareholder (the Government of Canada), most Crown corporations submit their corporate plans to the responsible ministers every year for approval by the Treasury Board. The plans set out activities, objectives, strategies, and operational and financial performance measures, targets, and risks.

40. During our 2020–2021 financial audits, we reviewed the timeliness of Treasury Board approvals of corporate plans for the 34 Crown corporations subject to submitting such plans. Thirty‑one of 34 (91%) corporate plans had not been approved by the Treasury Board before the start of each Crown corporation’s respective fiscal year. We noted that many of these corporate plans came up for approval by the Treasury Board around the time the COVID‑19 pandemic began. However, 6 months into their respective fiscal years, 21 (62%) of these corporations were still waiting for approval. At the end of their respective fiscal years, 10 (29%) of these corporations were still awaiting approval.

41. While awaiting approval of a new corporate plan, a Crown corporation continues to operate under its last approved plan. However, for Crown corporations to move forward with any additional activities needed to continue to fulfill their mandates, they need ongoing communication and timely decisions from the government about their corporate plans. For example, if a Crown corporation needs to replace an aging building, or invest in any major infrastructure, it must make a request to the government through the annual submission of its corporate plan. Delays in approval can result in project delays or possible additional costs when the projects are realized. It can also result in inefficiencies or require the corporation to redo work because of the shifts in priorities.

Opportunities for improvement noted in our 2020–2021 financial audits

42. Financial audits identify opportunities for organizations to improve their systems of internal control, streamline their operations, or enhance their financial reporting practices. We issue management letters to inform the organizations about these opportunities and about more serious points, such as inadequate internal controls that can create risks of errors in financial reports or result in non‑compliance with authorities.

43. We noted opportunities for improvement in various areas. Similar to last year, the most common were

- information technology (IT) general controls over systems supporting financial reporting

- internal controls related to financial reporting

- compliance with government policies, legislation, and regulations

- accounting and financial reporting practices

44. The Treasury Board’s Policy on Financial Management requires many federal organizations to establish, monitor, and maintain a risk-based system of internal control over financial management, including internal control over financial reporting. Crown corporations are not bound by this policy but instead follow requirements for financial and management control and information systems set out in Part X of the Financial Administration Act. We are not required by legislation to test or report on these systems at organizations. However, when we plan audits, we obtain an understanding of each organization’s overall system of internal control. At times, we select internal controls for audit testing. We do this when we believe it is effective to rely on them to collect audit evidence. In addition, when the internal controls we selected are supported by IT general controls, we consider the need to test these IT general controls.

45. In recent years, the government has created a Digital Government Strategy, which intends to transform the way government organizations serve Canadians. As organizations move to further modernize, we expect that they will enhance financial processes and systems. We believe this will provide opportunities to implement more internal controls that are supported by IT general controls. As a result, the financial processes and systems could improve the reliability of information, which could improve operational efficiency and financial management and reporting. When we can test that an organization’s system of internal control produces reliable information, this provides us with an additional source of evidence to support our audit.

46. This year, in 24 of the 69 federal organizations we audit, we performed reviews of IT general controls over systems supporting financial reporting. We identified and selected these internal controls supported by IT general controls and tested the related digital information. Further, our reviews enabled us to identify and inform these organizations of any opportunities we noted for improvement. We noted such opportunities in 11 organizations.

47. We did not perform reviews of IT general controls in 45 federal organizations this year. For these audits, we continued to perform substantive audit work—the examination of supporting documents and records—to support our audit opinions. As the use of technology changes and organizations make improvements to internal controls, including designing and implementing effective IT general controls, we will continue to consider the reliance on internal controls supported by IT general controls and digital information in our audits.

Additional insights from our financial audits—Cybersecurity

48. The federal government’s Canadian Centre for Cyber Security reported that the risk of cyberattacksDefinition 2 against federal organizations is on the rise. Several factors have increased this risk, including the following:

- Organizations were more reliant on digital devices and Internet connectivity during the COVID‑19 pandemic because of increases in remote work, among other things.

- Cybercriminals have used malicious emails and websites disguised as resources related to COVID‑19 to conduct criminal activities.

- More sophisticated activities sponsored by foreign countries posed a threat to Canadian organizations.

49. When planning and conducting a financial audit, we consider cybersecurity risks along with other inherent risks that could affect financial reporting. We also gain an understanding of the controls implemented by federal organizations to mitigate those risks. We carry out audit work to provide an opinion on whether the financial statements are fairly stated, in all material respects.

50. To date, we have not modified any of our audit opinions on financial statements because of cyberattacks experienced by federal organizations. This is because any such incidents have either properly been accounted for or have not had a material impact on the organization’s financial reporting. It should be noted that our financial audit work is not sufficient, nor intended, to conclude on other matters, such as the confidentiality of government or personal information. We are undertaking a performance audit of the cybersecurity of personal information in the cloud and plan to report on this to Parliament in fall 2022.

51. According to the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security, individuals and federal organizations continue to face attempts to steal personal, financial, and corporate information. In our financial audits of federal organizations, we were made aware of attempted cyberattacks that were detected and stopped. In addition, during the 2020–21 fiscal year, 5 organizations were subject to a cyberattack. This required us to do additional audit work to assess the impact on their financial reporting.

52. The effects of the attacks on these organizations varied but included

- certain systems taken offline and respective operations stopped, causing delays and disruptions to activities

- lost data, costing time and resources to recover

- stolen account credentials, unauthorized access to accounts, and unauthorized changes to personal information on compromised accounts of Canadians who interacted with the federal organization

53. In all cases that we observed, the federal organizations were able to continue or restore their operations. However, it can be difficult for any organization to know the extent to which data was stolen in a cyberattack. Once data is outside of an organization’s control, individuals and businesses are vulnerable to risks of identity theft, phishing, ransomware, and other losses.

54. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat is responsible for setting IT policy requirements and for providing strategic oversight of government cybersecurity event management. Further, each federal organization is responsible for the governance of its cybersecurity. Organizations are supported by Communications Security Establishment Canada and the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security. The centre is the lead technical authority responsible for identifying emerging cyberthreats, monitoring government networks and systems, and helping protect against, and mitigate potential effects of, cybersecurity events. The centre also provides advice and guidance on cybersecurity. We encourage federal organizations to prioritize their cybersecurity activities and to follow the Government of Canada policies, directives, and guidance provided for security management to defend and protect against cyberattacks.

Additional insights from our financial audits—Advancing the use of data

55. There has been a move toward digital government in recent years. Digital government involves offering services to Canadians via the Internet and other IT. The government’s current approach to digital government is guided by Canada’s Digital Government Strategy, which aims to use IT to transform government operations and improve services to Canadians. As part of this strategy, the government recently issued a Digital Operations Strategic Plan for 2021–2024. The 3‑year government-wide plan sets out the strategic direction for the integrated management of service, information, data, IT, and cybersecurity. This plan provides the context in which government manages operational and financial data. This financial data gets reported in financial statements, which we audit annually.

56. In our view, advancing the use of data, including using more sophisticated data analytics, will be important to achieving the government’s digital strategies. Data analytics are qualitative and quantitative techniques and processes used to analyze data in order to make conclusions about that information and inform decision making. Many of these techniques and processes can also benefit from automation. The government has several projects with IT systems undergoing major conversion or replacement, where it could consider the integration of data analytics to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of operations. We reported on some of these projects in our previous commentary reports and in our February 2021 performance audit report on procuring complex IT solutions.

57. The government identifies many benefits of using data analytics. Among other things, data analytics can

- identify anomalies in data, which can improve effectiveness of controls, reduce accounting errors, help to identify fraud, and identify inefficiencies or errors in the delivery of services to Canadians

- automate routine processes to reduce errors and increase consistency in service delivery

- improve the management of operations and facilitate better and timelier decisions by using insights from data

- provide more accurate, more complete, and timelier information to Canadians on government programs and processes

58. In 2018, the government issued A Data Strategy Roadmap for the Federal Public Service, which noted an absence of a governance structure providing strategic direction on data issues and several challenges in managing data. Through our audit work, we collaborate with federal organizations and obtain various operational and financial data. We noted similar challenges, including ones that can limit the benefits of data analytics:

- There are challenges in extracting data and in integrating data from disparate sources.

- The prevalent use of spreadsheets in federal organizations increases the risk of data quality issues because of the lack of checks and control processes in some older databases.

- Organizations sometimes are unaware of what data is available to them or fail to use all available data to analyze what works well, and what does not, within government programs.

- There is a gap between the current and desired levels of proficiency in applying data analytics.

59. These challenges can result in incomplete or inaccurate data, leading to lower productivity, poor decision making, and missed opportunities. For example, in our March 2021 performance audit of the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy, we found that the Canada Revenue Agency did not collect employee names or social insurance numbers in the wage subsidy applications. This lack of specific information limited the agency’s ability to conduct automated validations before issuing payments or to cross-match data to other sources. In the early days of the subsidy program, the agency flagged this as creating a high risk of overpayment.

60. Despite the above challenges, we were able to use data analytics as a tool within some of our financial and performance audits. For example, to obtain audit assurance in our financial audits, we used data analytics to detect patterns in specific entity accounts. We then used these patterns, in combination with other audit evidence we collected, to conclude on whether amounts reported in the financial statements were accurate and complete.

61. Advances in how federal organizations use data would allow us to expand our use of data analytics. The benefits of this would be

- improved risk assessments, to better target our audit work

- increased audit efficiency

- more comprehensive analysis, including deeper insights on root causes of errors or anomalies

- sharing opportunities to improve models and tools used by management

62. We encourage the government to continue its progress on the data strategy roadmap and the Digital Operations Strategic Plan. It can take many years, but we see many benefits to decision making and outcomes for Canadians.

Appendix A—Measures included in the Government of Canada’s COVID‑19 Economic Response Plan

We have compiled the measures included in the Government of Canada’s COVID‑19 Economic Response Plan on the basis of our review of information published by the government. We agreed the amounts spent or advanced between 1 April 2020 and 31 March 2021 to the government’s consolidated financial statements, or financial statements of Crown corporations, where possible. For some measures, we have reproduced the estimated amounts spent, as reported by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates.

Protecting health and safety measures

| Number | Measure | Amount expensed or advanced—1 April 2020 to 31 March 2021 (in $ millions) |

Included in Public Accounts of Canada line item (in $ millions) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Safe Restart AgreementNote * |

15,843.5 |

Major transfer payments to other levels of government ($12,977) Inventories ($2,867) |

|

2 |

Helping health care systems recover |

4,000.0 |

Major transfer payments to other levels of government |

|

3 |

Further support for medical research and vaccine developmentsNote * |

2,466.7 |

Other transfer payments ($867) Prepaid expenses ($1,600) |

|

4 |

Safe Return to Class |

2,000.0 |

Major transfer payments to other levels of government |

|

5 |

Funding for personal protective equipment and suppliesNote * |

1,816.5 |

Major transfer payments to other levels of government ($1,283) Inventories ($533) |

|

6 |

Canada’s COVID‑19 immunization plan |

1,000.0 |

Major transfer payments to other levels of government |

|

7 |

Support for international partners |

698.8 |

Other transfer payments |

|

8 |

Safe Restart Agreement federal investments in testing, contact tracing, and data managementNote * |

532.8 |

Major transfer payments to other levels of government |

|

9 |

COVID‑19 response fundNote * |

417.8 |

Other transfer payments |

|

10 |

Supporting a safe restart in Indigenous communitiesNote * |

314.8 |

Other transfer payments |

|

11 |

Canadian Armed Forces support for the COVID‑19 response |

292.4 |

Other expenses |

|

12 |

Enhancing public health measures in Indigenous communitiesNote * |

279.0 |

Other transfer payments |

|

13 |

Personal protective equipment and related equipment support for essential workersNote * |

255.0 |

Other transfer payments |

|

14 |

Support for COVID‑19 medical research and vaccine developmentsNote * |

239.4 |

Other transfer payments |

|

15 |

Quarantine facilities and COVID‑19 border measures |

227.8 |

Other expenses |

|

16 |

Health and social support for northern communitiesNote * |

179.6 |

Other transfer payments |

|

17 |

Supporting public health measures in correctional institutions |

156.3 |

Other expenses |

|

18 |

Virtual care and mental health supportNote * |

137.3 |

Other transfer payments |

|

19 |

Supporting and sustaining the Public Health Agency of Canada and Health Canada’s pandemic operations |

107.3 |

Other expenses |

|

20 |

Support for Health Canada and the Public Health Agency of CanadaNote * |

83.7 |

Other expenses |

|

21 |

Funding for information technologyIT services, infrastructure, and cybersecurity |

80.9 |

Other expenses |

|

22 |

Consular assistance for Canadians abroadNote * |

54.9 |

Other expenses |

|

23 |

COVID‑19 communications and marketing |

45.1 |

Other expenses |

|

24 |

Communication services |

26.8 |

Other expenses |

|

25 |

Canada Healthy Communities Initiative |

19.6 |

Major transfer payments to other levels of government |

|

26 |

Support for food inspection services |

19.4 |

Other expenses |

|

27 |

Supporting the ongoing delivery of key benefits |

17.8 |

Other expenses |

|

28 |

Funding for countermeasures for chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear threats, including pandemic influenza |

15.4 |

Other expenses |

|

29 |

Immediate public health response |

12.5 |

Other expenses |

|

30 |

Advertising campaign: Government of Canada’s COVID‑19 Economic Response PlanNote * |

10.0 |

Other expenses |

|

31 |

Improving ventilation in public buildings |

0.2 |

Other expenses |

|

32 |

Supporting court operations and access to justice |

0.1 |

Other expenses |

|

Subtotal—Protecting health and safety measures |

31,351.4 |

Direct support measures for individuals

| Number | Measure | Amount expensed or advanced—1 April 2020 to 31 March 2021 (in $ millions) |

Included in Public Accounts of Canada line item (in $ millions) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

33 |

Canada Emergency Response BenefitNote * |

63,693.3 |

Canada Emergency Response Benefit and Canada recovery benefits ($39,049) Employment Insurance and support measures ($24,644) |

|

34 |

Canada Recovery Benefit |

14,417.3 |

Canada Emergency Response Benefit and Canada recovery benefits |

|

35 |

Enhanced goods and services tax credit |

5,425.0 |

Other taxes and duties (reducing) |

|

36 |

Essential workers wage top-up |

2,884.2 |

Major transfer payments to other levels of government |

|

37 |

Canada Emergency Student BenefitNote * |

2,880.4 |

Other transfer payments |

|

38 |

One-time payment for seniors eligible for Old Age Security and Guaranteed Income SupplementNote * |

2,455.0 |

Other transfer payments |

|

39 |

Enhanced Canada Child Benefit |

2,000.0 |

Children’s benefits |

|

40 |

Canada Recovery Caregiving Benefit |

1,956.7 |

Canada Emergency Response Benefit and Canada recovery benefits |

|

41 |

Temporary changes to Employment Insurance to improve access |

1,634.0 |

Employment Insurance and support measures |

|

42 |

Supporting provincial and territorial job training efforts as part of COVID‑19 economic recoveryNote * |

1,499.3 |

Major transfer payments to other levels of government |

|

43 |

Enhancing student financial assistance for fall 2020 |

1,350.9 |

Other transfer payments |

|

44 |

Support for persons with disabilitiesNote * |

810.3 |

Other transfer payments |

|

45 |

Canada Recovery Sickness Benefit |

409.4 |

Canada Emergency Response Benefit and Canada recovery benefits |

|

46 |

Canada Emergency Response Benefit administration costsNote * |

287.6 |

Other expenses |

|

47 |

Support for the On-reserve Income Assistance ProgramNote * |

262.2 |

Other transfer payments |

|

48 |

Canada Revenue Agency funding for COVID‑19 economic measuresNote * |

219.4 |

Other expenses |

|

49 |

Ensuring access to Canada Revenue Agency call centresNote * |

97.5 |

Other expenses |

|

50 |

Canada Emergency Student Benefit administration costsNote * |

17.6 |

Other expenses |

|

51 |

Wage support for Staff of the Non-Public Funds, Canadian Forces |

11.2 |

Other expenses |

|

52 |

Improving our ability to reach Canadians |

10.9 |

Other expenses |

|

53 |

Support for children and youthNote * |

4.2 |

Children’s benefits |

|

54 |

Canada student loan moratorium |

2.5 |

Other expenses |

|

55 |

Insured mortgage payment deferrals |

Not applicable—Footnote A |

|

|

Subtotal—Direct support measures for individuals |

102,328.9 |

Direct support measures for businesses

| Number | Measure | Amount expensed or advanced—1 April 2020 to 31 March 2021 (in $ millions) |

Included in Public Accounts of Canada line item (in $ millions) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

56 |

Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy |

79,277.7 |

Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy |

|

57 |

Canada Emergency Business Account loan incentive |

13,084.7 |

Other transfer payments |

|

58 |

Canada Emergency Rent Subsidy |

4,045.0 |

Other transfer payments |

|

59 |

Canada Emergency Commercial Rent AssistanceNote * |

2,147.0 |

Other transfer payments |

|

60 |

Regional Relief and Recovery FundNote * |

1,869.3 |

Other transfer payments |

|

61 |

Cleaning up former oil and gas wells |

1,720.0 |

Major transfer payments to other levels of government ($1,520) Other loans, investments, and advances ($200) |

|

62 |

Indigenous Community Support FundNote * |

1,027.7 |

Other transfer payments |

|

63 |

Temporary Wage Subsidy |

888.3 |

Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy |

|

64 |

Expanding existing federal employment, skills development, and student and youth programmingNote * |

880.0 |

Other transfer payments |

|

65 |

Rapid Housing InitiativeNote * |

870.4 |

Other expenses |

|

66 |

Support for cultural, heritage, and sport organizationsNote * |

497.9 |

Other transfer payments |

|

67 |

Support for Canada’s academic research communityNote * |

434.5 |

Other transfer payments |

|

68 |

Support for the homeless (through Reaching Home)Note * |

394.1 |

Other transfer payments |

|

69 |

Indigenous public health investments |

382.8 |

Other transfer payments |

|

70 |

Emergency Community Support FundNote * |

349.7 |

Other transfer payments |

|

71 |

Support for workers in the Newfoundland and Labrador offshore energy sector |

320.0 |

Major transfer payments to other levels of government |

|

72 |

Support for Indigenous businesses and Aboriginal financial institutionsNote * |

228.8 |

Other transfer payments |

|

73 |

Support for food banks and local food organizationsNote * |

170.9 |

Other transfer payments |

|

74 |

Supporting Canada’s farmers, food businesses, and food supplyNote * |

157.5 |

Other transfer payments |

|

75 |

Support for fish harvestersNote * |

144.8 |

Other transfer payments |

|

76 |

Support for local Indigenous businesses and economiesNote * |

133.0 |

Other transfer payments |

|

77 |

Targeted extension of the Innovation Assistance ProgramNote * |

127.3 |

Other transfer payments |

|

78 |

Support for the Canadian Red CrossNote * |

99.3 |

Other transfer payments |

|

79 |

Funding for VIA Rail Canada IncorporatedInc. |

90.4 |

Other expenses |

|

80 |

Indigenous mental wellness supportNote * |

82.4 |

Other transfer payments |

|

81 |

Support for food system firms that hire temporary foreign workersNote * |

74.0 |

Other transfer payments |

|

82 |

Support essential air access to remote communities |

68.3 |

Other transfer payments |

|

83 |

Support for women’s shelters and sexual assault centres, including in Indigenous communitiesNote * |

50.0 |

Other transfer payments |

|

84 |

Addressing the outbreak of COVID‑19 among temporary foreign workers on farmsNote * |

49.3 |

Other transfer payments |

|

85 |

Addressing gender-based violence during COVID‑19Note * |

48.9 |

Other transfer payments |

|

86 |

Support for fish and seafood processorsNote * |

45.2 |

Other transfer payments |

|

87 |

Bio-manufacturing capacity expansion—National Research Council Royalmount facilityNote * |

43.5 |

Other transfer payments |

|

88 |

Supporting distress centres, the Wellness Together Canada Portal |

41.7 |

Other transfer payments |

|

89 |

Parks Canada revenue replacement and rent relief |

35.7 |

Other transfer payments |

|

90 |

Emissions reduction fund for the oil and gas sector |

31.7 |

Other transfer payments |

|

91 |

Support for the broadcasting industry |

31.4 |

Other transfer payments |

|

92 |

Support for safe operation in the forest sector |

30.1 |

Other transfer payments |

|

93 |

Support for Canada’s national museumsNote * |

25.7 |

Other expenses |

|

94 |

Support for veterans’ organizationsNote * |

20.0 |

Other transfer payments |

|

95 |

New Horizons for Seniors Program expansionNote * |

20.0 |

Other transfer payments |

|

96 |

Support for Canada’s National Arts CentreNote * |

18.2 |

Other expenses |

|

97 |

Financial relief for First Nations through the First Nations Finance Authority |

17.1 |

Other transfer payments |

|

98 |

Women Entrepreneurship Strategy—Ecosystem top-up |

15.0 |

Other transfer payments |

|

99 |

Personal support worker training and other measures to address labour shortages in long-term and home careNote * |

12.6 |

Other transfer payments |

|

100 |

Granville Island Emergency Relief FundNote * |

10.4 |

Other transfer payments |

|

101 |

Supporting Canada’s broadcasting system |

7.9 |

Other transfer payments |

|

102 |

Support for main street businesses |

7.8 |

Other transfer payments |

|

103 |

Support for the Federal Bridge Corporation LimitedNote * |

5.8 |

Other expenses |

|

104 |

Support for the National Film Board |

4.7 |

Other expenses |

|

105 |

Investments in long-term care and other supportive care facilities |

4.7 |

Other transfer payments |

|

106 |

Enhancements to the work-sharing program |

4.4 |

Other transfer payments |

|

107 |

Canadian Digital Service |

3.6 |

Other transfer payments |

|

108 |

Labour market impact assessment refund |

2.8 |

Other transfer payments |

|

109 |

Canada Emergency Business Account administration costs |

1.8 |

Other expenses |

|

110 |

Innovative research and support for new testing approaches and technologies for COVID‑19 |

1.6 |

Other transfer payments |

|

111 |

Regional Air Transportation Initiative |

1.1 |

Other transfer payments |

|

112 |

Funding to support business resumption for federally regulated employers |

0.9 |

Other transfer payments |

|

113 |

Support for audiovisual industryNote * |

0.8 |

Other transfer payments |

|

114 |

Waiver of broadcast licence fees |

Not applicable—Footnote A |

|

|

115 |

Airport ground lease rent deferrals |

Not applicable—Footnote B |

|

|

116 |

Waiver of interest on deposit insurance premiums |

Not applicable—Footnote B |

|

|

Subtotal—Direct support measures for businesses |

110,160.2 |

||

|

Total—Protecting health and safety measures and direct support measures to individuals and businesses |

243,840.5 |

Tax liquidity support

| Number | Measure | Amount expensed or advanced—1 April 2020 to 31 March 2021 (in $ millions) |

Included in Public Accounts of Canada line item (in $ millions) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

117 |

Income tax payment deferral until 30 September 2020 |

Not applicable—Footnote B |

|

|

118 |

Sales tax remittance and customs duty payments deferral |

Not applicable—Footnote B |

|

|

119 |

Supporting Jobs and Safe Operations of Junior Mining Companies |

Not applicable—Footnote B |

Other liquidity support and capital relief

| Number | Measure | Amount expensed or advanced—1 April 2020 to 31 March 2021 (in $ millions) |

Included in Public Accounts of Canada line item (in $ millions) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

120 |

Canada Emergency Business Account |

44,881.1 |

Other loans, investments, and advances |

|

121 |

Insured Mortgage Purchase Program |

5,817.0 |

Enterprise Crown corporations and other government business enterprises and the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation annual report |

|

122 |

Business Credit Availability Program and other credit availability programs |

3,695.8 |

Enterprise Crown corporations and other government business enterprises and the Business Development Bank of Canada ($3,408) and Export Development Canada ($288) annual reports |

|

123 |

Portfolio insurance eligibility extensions |

Not applicable—Footnote A |

|

|

124 |

Support for the agriculture and agri-food sector |

891.0 |

Enterprise Crown corporations and other government business enterprises and the Farm Credit Canada annual report |

|

125 |

Large Employer Emergency Financing Facility |

319.0 |

Enterprise Crown corporations and other government business enterprises and the Canada Enterprise Emergency Funding Corporation annual report |

|

126 |

Bank of Canada actions to support the Canadian economy and financial system |

Enterprise Crown corporations and other government business enterprises and the Bank of Canada annual report |

|

|

127 |

Capital relief (Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada Domestic Stability Buffer) |

Not applicable—Footnote A |

|

|

Subtotal—Other liquidity support and capital relief |

55,603.9 |

||

|

Grand total—Protecting health and safety measures, direct support measures to individuals and businesses, and liquidity support and capital relief |

299,444.4 |

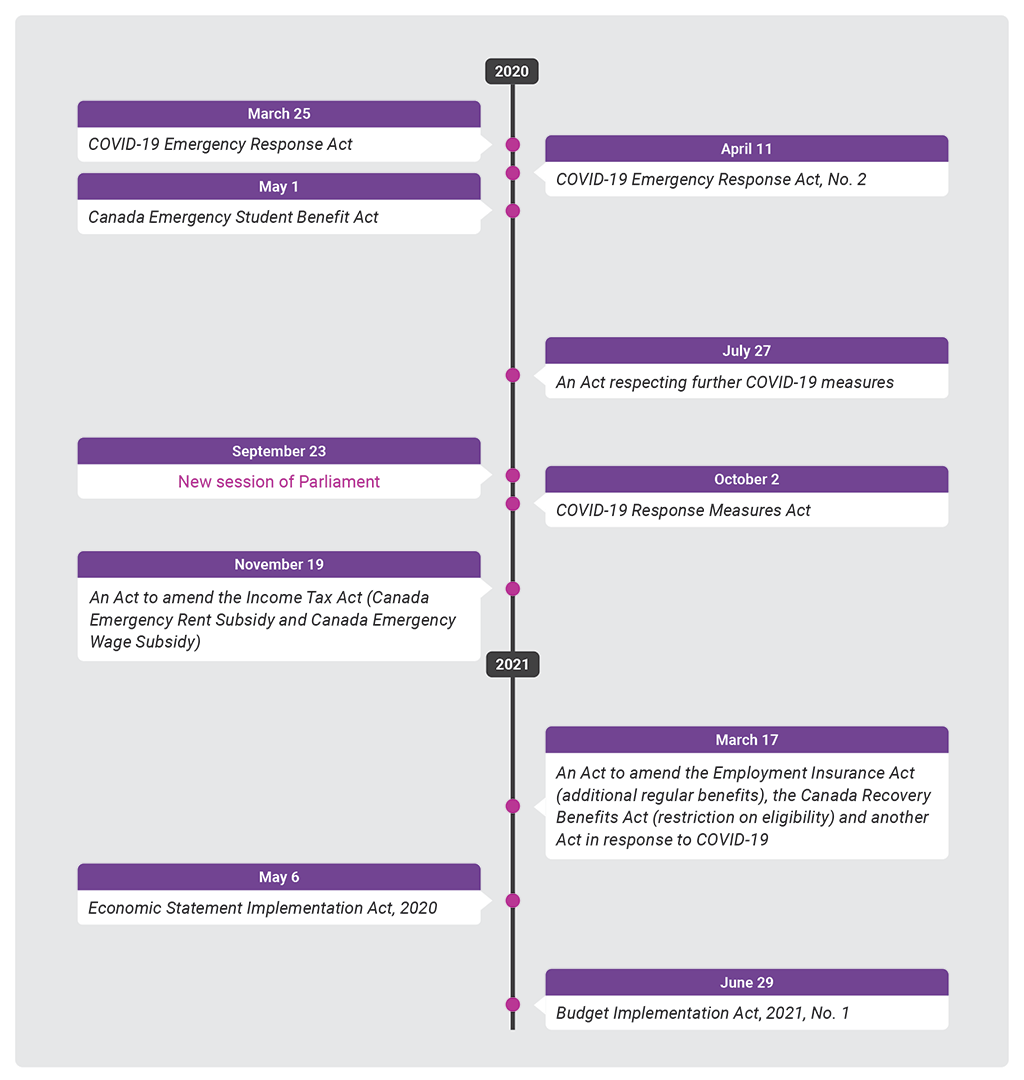

Appendix B—Timeline of key federal legislation related to COVID‑19 spending

Source: Based on information from the Parliament of Canada’s website

Appendix B—text version

This timeline shows the dates on which key federal legislation related to COVID‑19 spending was passed. On 25 March 2020, the COVID‑19 Emergency Response Act was passed. On 11 April 2020, the COVID‑19 Emergency Response Act, numberNo. 2 was passed. On 1 May 2020, the Canada Emergency Student Benefit Act was passed. On 27 July 2020, An Act respecting further COVID‑19 measures was passed. On 23 September 2020, a new session of Parliament began. On 2 October 2020, the COVID‑19 Response Measures Act was passed. On 19 November 2020, An Act to amend the Income Tax Act (Canada Emergency Rent Subsidy and Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy) was passed. On 17 March 2021, An Act to amend the Employment Insurance Act (additional regular benefits), the Canada Recovery Benefits Act (restriction on eligibility) and another Act in response to COVID‑19 was passed. On 6 May 2021, the Economic Statement Implementation Act, 2020 was passed. On 29 June 2021, the Budget Implementation Act, 2021, numberNo. 1 was passed.