The Auditor General’s observations on the Government of Canada’s 2020–2021 consolidated financial statements

Pay administration

63. Since the government centralized employee payroll with the Transformation of Pay Administration Initiative in 2016, our audit of the government’s consolidated financial statements has required detailed testing of a sample of federal employees’ pay transactions because of internal control weaknesses in the “HR‑to‑pay” process. This process links information in human resources (HR) systems with the pay system.

64. It is important that employees are paid accurately and on time. Therefore, we expect that the government will return to having pay processes with sufficient and appropriate internal controls. This expectation remains, regardless of whether the government keeps its current pay system for some entities or implements a new one.

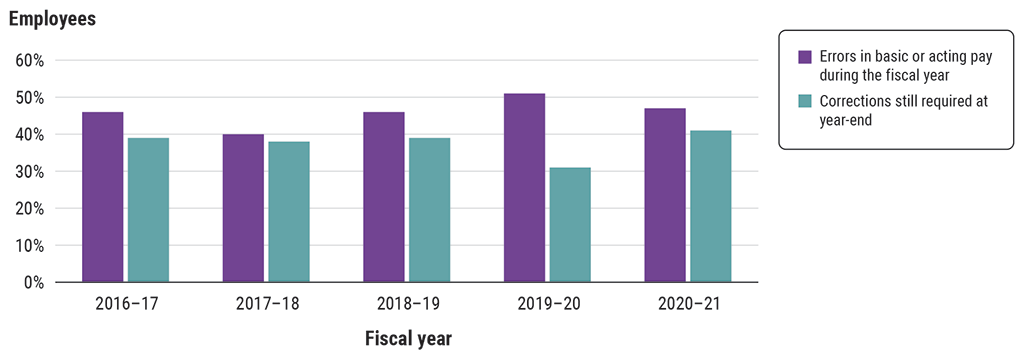

65. As a result of our audit work, we found that 47% of employees we sampled had an error in their basic or acting pay during the 2020–21 fiscal year, compared with 51% in the prior year. We also found that 41% of employees we sampled still required corrections to their pay as at 31 March 2021, an increase from the 31% reported in the prior year (Exhibit 5).

Exhibit 5—Percentage of employees in our sample with an error in basic or acting pay during the fiscal year and who were still awaiting a correction at year-end

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of a sample of Government of Canada employees’ pay transactions for the 5 fiscal years ending March 31 from 2017 to 2021

Exhibit 5—text version

This chart shows for each fiscal year from 2016–17 to 2020–21 the percentage of employees in our sample with an error in basic or acting pay during the fiscal year and who were still awaiting a correction at year‑end. The chart shows that the percentage of employees in our sample who had an error in basic or acting pay during the fiscal year decreased from 46% in 2016–17 to 40% in 2017–18, and then increased to 46% in 2018–19 and to 51% in 2019–20, and then decreased to 47% in 2020–21. The chart also shows that the percentage of employees in our sample who were still awaiting a correction at year‑end was steady at either 38% or 39% for the 3 fiscal years from 2016–17 to 2018–19, and then decreased to 31% in 2019–20, and then increased to 41% in 2020–21.

66. We concluded that pay expenses were presented fairly in the Government of Canada’s 2020–21 consolidated financial statements. What contributed to the fair presentation was that overpayments and underpayments made to employees continued to partially offset each other. In addition, year-end accounting adjustments were made to improve the accuracy of pay expenses. However, as we noted in previous commentaries, these adjustments did not correct the persistent pay errors for the employees who were overpaid or underpaid.

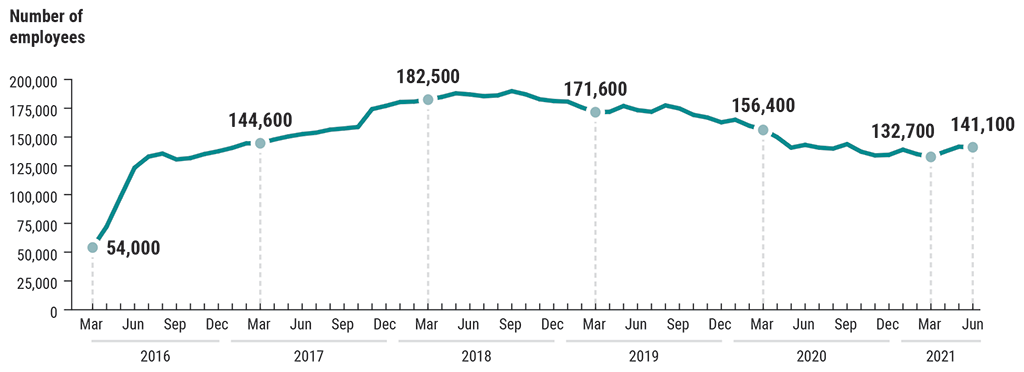

67. Despite the COVID‑19 pandemic, the Public Service Pay Centre continued to work remotely and to address the outstanding pay action requests during the year. However, thousands of employees are still affected and awaiting the resolution of pay action requests (Exhibit 6).

Exhibit 6—Number of employees with outstanding pay action requests in the departments and agencies served by the Public Service Pay Centre

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of data in Public Services and Procurement Canada’s Case Management Tool

Exhibit 6—text version

This line chart shows the number of employees with outstanding pay action requests in the departments and agencies served by the Public Service Pay Centre. The chart shows that from March 2016 to June 2021, the number of employees with outstanding pay action requests went from 54,000 to 141,100.

In March 2016, there were 54,000 employees with outstanding pay action requests in the departments and agencies served by the Public Service Pay Centre. In March 2017, that number had risen to 144,600, and in March 2018, that number had risen to 182,500. In March 2019, that number had declined to 171,600. In March 2020, that number had declined to 156,400, and in March 2021, that number had declined to 132,700. In June 2021, that number had increased to 141,100.

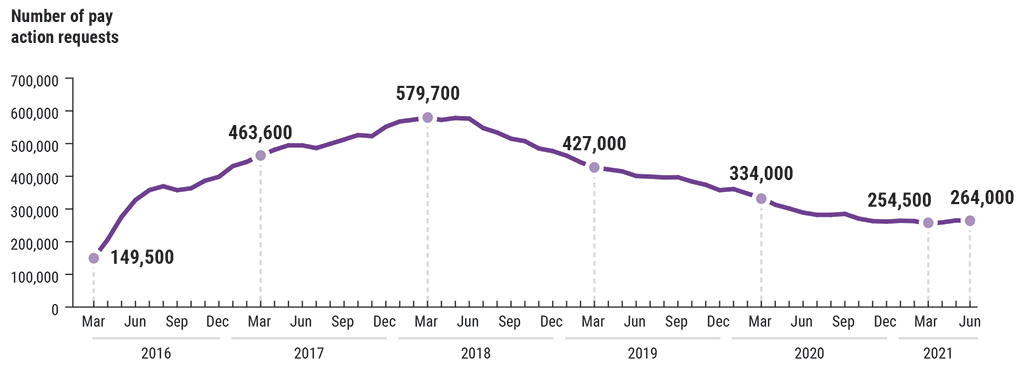

68. For a number of years, we have been reporting on the total number of outstanding pay action requests in the departments and agencies served by the Public Service Pay Centre. As at 31 March 2021, there were 254,500 outstanding pay action requests, a substantial improvement from the 334,000 requests reported as at 31 March 2020. However, as at June 2021, 3 months after the government’s fiscal year-end, the number of outstanding pay action requests had increased to 264,000 (Exhibit 7).

Exhibit 7—Number of outstanding pay action requests in the departments and agencies served by the Public Service Pay Centre

Source: From March 2016 to June 2018, based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of data in Public Services and Procurement Canada’s Case Management Tool. From July 2018 to June 2021, based on data in Public Services and Procurement Canada’s Case Management Tool

Exhibit 7—text version

This line chart shows the number of outstanding pay action requests in the departments and agencies served by the Public Service Pay Centre. The chart shows that from March 2016 to June 2021, the number of outstanding pay action requests went from 149,500 to 264,000.

In March 2016, there were 149,500 outstanding pay action requests in the departments and agencies served by the Public Service Pay Centre. In March 2017, that number had risen to 463,600, and in March 2018, that number had risen to 579,700. In March 2019, that number had declined to 427,000. In March 2020, that number had declined to 334,000, and in March 2021, that number had declined to 254,500. In June 2021, that number had increased to 264,000.

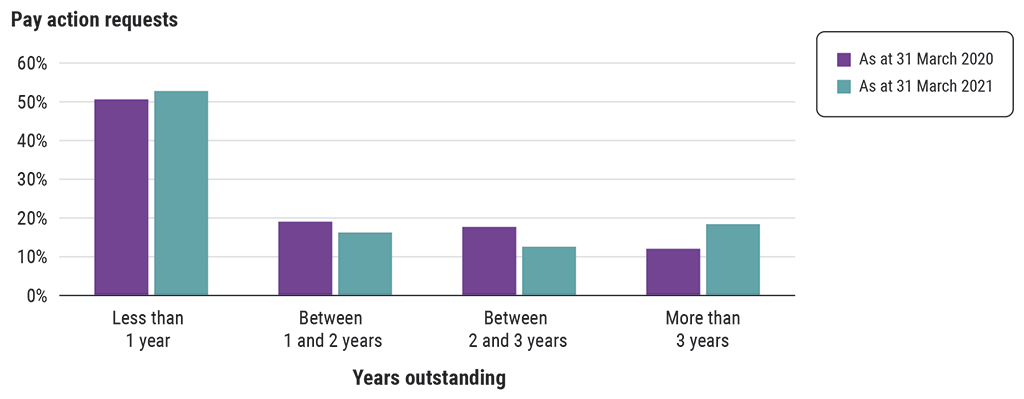

69. We did an analysis of how long pay action requests remained unresolved. We found that as at 31 March 2021, 18% of pay action requests, or 46,400, were more than 3 years old (Exhibit 8). This was an increase from 12%, or 40,200 requests, the previous year. Given that the oldest pay action requests are not necessarily resolved first, it can take years for employees’ pay to be fully corrected. For instance, of the 40,200 requests that were more than 3 years old last year, 46%, or 18,300, remained unresolved as at 31 March 2021.

Exhibit 8—Percentage of pay action requests in the departments and agencies served by the Public Service Pay Centre, by number of years outstanding

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of data in Public Services and Procurement Canada’s Case Management Tool

Exhibit 8—text version

This chart shows the percentage of pay action requests in the departments and agencies served by the Public Service Pay Centre by number of years outstanding as at 31 March 2020 and as at 31 March 2021. The percentage of pay action requests that were outstanding for less than 1 year increased from 51% as at 31 March 2020 to 53% as at 31 March 2021. The percentage of pay action requests that were outstanding for between 1 and 2 years decreased from 19% as at 31 March 2020 to 16% as at 31 March 2021. The percentage of pay action requests that were outstanding for between 2 and 3 years decreased from 18% as at 31 March 2020 to 13% as at 31 March 2021. The percentage of pay actions requests that were outstanding for more than 3 years increased from 12% as at 31 March 2020 to 18% as at 31 March 2021.

70. On the basis of the current rate at which the pay centre is processing pay action requests, we estimate that it could take until April 2023 to address those requests outstanding as at March 2021. The government expects that there will always be outstanding pay action requests from normal ongoing pay transactions. However, we encourage the pay centre to resolve old requests and take steps so that employees’ requests are resolved in a reasonable amount of time and are not outstanding for several years.

71. In our 2017–18 commentary, we reported on internal control deficiencies in the HR-to-pay process. We also issued management letters in past years that identified internal control deficiencies to be addressed by the government. This year, we followed up on IT general controls for pay administration and noted that the government had made some improvements. For example, for the Phoenix pay system, improvements were made to access and change management controls.

72. During our 2020–21 audit, we also began audit work on the design of internal controls for certain payroll applications. Because the HR‑to‑pay process is quite complex and involves numerous systems, this work will continue as part of next year’s audit. This audit work is exploratory work that can set a path to our returning to a controls-reliant audit approach in the future. However, this may not be possible until effective internal controls are implemented in the HR‑to‑pay process, in addition to resolving the backlog of outstanding pay requests and data quality issues.

73. As reported in last year’s commentary, we continue to be concerned that the government’s new HR and pay system could repeat weaknesses we have found in the HR-to-pay process and could pay some employees inaccurately. Next Generation, the current initiative to replace the government’s HR and pay system, is expected to be a large, multi-year initiative. We note that the government recently began pilot projects and planned to test new pay systems in selected departments as part of the initiative.

74. Because it is important that the new HR and pay system will process employee pay accurately and on time, we will continue to be involved as the auditor to report on the government’s progress toward a long-term, sustainable, and efficient HR and pay system.

National Defence inventory and asset pooled items

75. For 18 years, we have raised concerns about the ability of National Defence to properly account for the quantities and values of its inventory. We have also reported on National Defence’s asset pooled items, which are tangible capital assets that are managed like inventory. As at 31 March 2021, inventories at National Defence were valued at about $5.2 billion (or about 53% of the government’s total inventories). Asset pooled items were valued at about $3.2 billion and were included in the government’s tangible capital assets.

76. National Defence submitted a 10-year inventory management action plan to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts in the 2016–17 fiscal year. The plan set out actions to better record, value, and manage the department’s inventory.

77. In May 2021, National Defence reported that most of the action plan initiatives were completed. Despite the operational challenges that the pandemic had on the department, we continue to be encouraged by the progress made. A key initiative, scheduled to be completed by the end of the 2026–27 fiscal year, is the implementation of a modern scanning and barcoding capability within the department’s inventory management system. In our view, this is an important initiative that, once implemented, could help strengthen inventory management and improve the accuracy of inventory and asset pooled item information.

78. However, we also continue to find discrepancies in the reported amounts of inventory and asset pooled items during our annual audit. We noted a combined understatement of inventory and asset pooled items at year-end of an estimated $176 million. Similar to last year, in about a quarter of the items we sampled, we found errors in at least 1 of the characteristics we tested: quantities, values, or classification. This shows that there is still more work to be done to improve the recording of inventory and asset pooled items in the departmental records.

79. Through the department’s action plan, management has put processes in place to address some of the weaknesses with respect to the management and accounting of inventory and asset pooled items. We encourage the department to continue to monitor the implementation of the plan and refine its processes within materiel and financial management, with the cooperation of the Canadian Armed Forces, to address the root causes of these types of errors. Until that is done and internal controls around the management and accounting of inventory are strengthened, these levels of discrepancies within the underlying data will continue. As we have noted in the past, maintaining adequate records and strong controls over these assets is important to the department’s ability to deliver its programs efficiently and cost-effectively.

80. In addition to National Defence’s scanning and barcoding initiative, the department is also planning the future upgrade of its enterprise resource planning software. Both of these projects will be integral to addressing accuracy issues with inventory data.

81. While these significant software changes are still several years away, addressing the root causes of discrepancies and strengthening internal controls will help to maximize the benefits of the investments in these new systems.