2022 Reports 6 to 10 of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the Parliament of Canada

Report 7—Protecting Aquatic Species at Risk

At a Glance

Overall, we found that Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s approach to protecting aquatic species assessed as being at risk under the Species at Risk Act contributed to significant listing delays and decisions not to list species with commercial value. It also had knowledge gaps for some species that directly affected the actions needed to protect them. Fisheries and Oceans Canada focused its knowledge-building primarily on species of commercial value.

We found that some department actions resulted in delays in decisions to protect species under the Species at Risk Act, especially species that are commercially fished. It had yet to provide listing advice for half of the species assessed as being at risk since the act came fully into force in 2004. Furthermore, the analysis the department used to develop listing advice was sometimes unclear or insufficient.

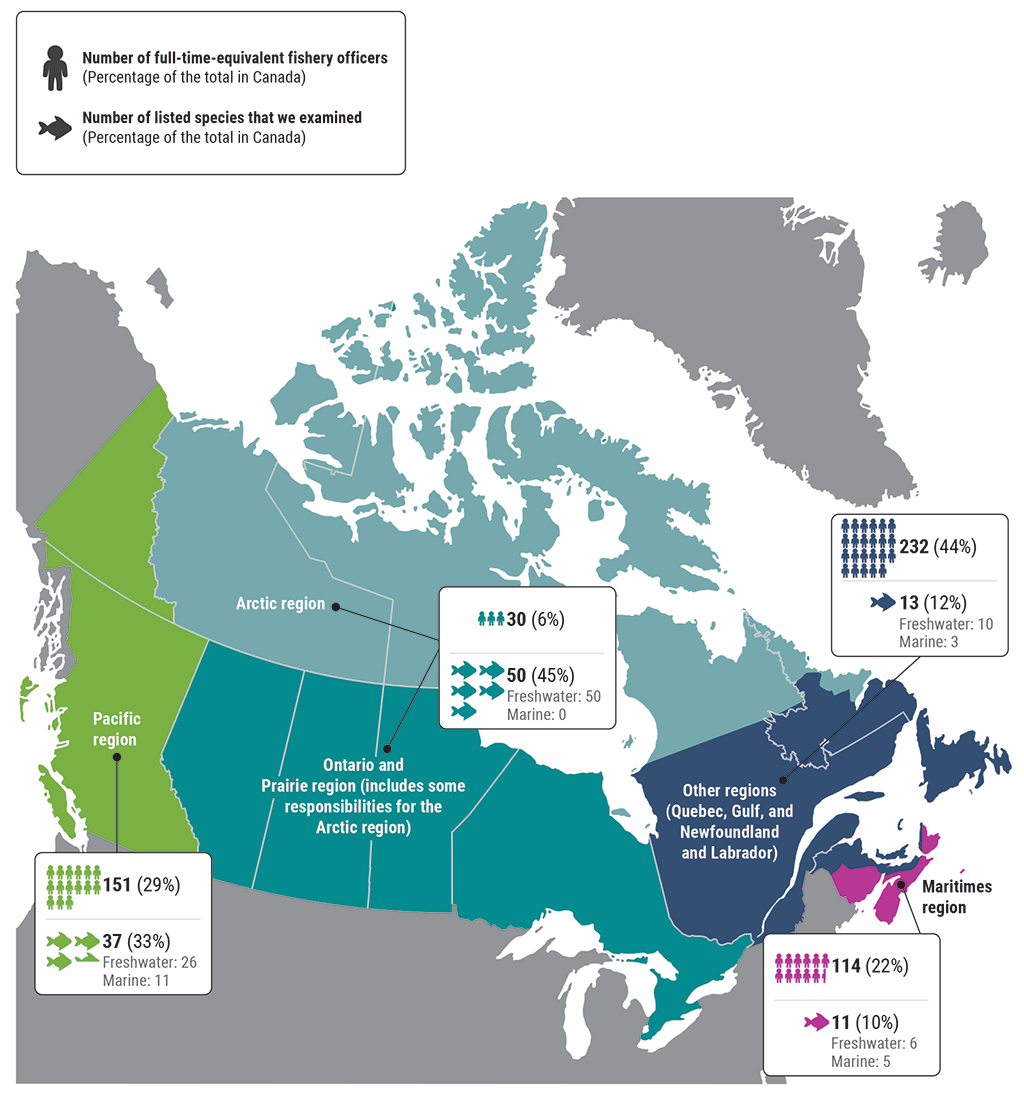

We also found that the department did not have enough staff to enforce compliance with the Species at Risk Act and the Fisheries Act—the 2 main pieces of legislation aimed at conserving and protecting biodiversity—especially in the region that manages most of the freshwater species listed under the Species at Risk Act.

The impact of these delays and gaps is significant because the loss of a species has an effect on ecosystems and communities. Without a change in approach that enables Fisheries and Oceans Canada to collect sufficient information about all the aquatic species it is responsible for, it will be difficult to take appropriate actions to protect many species.

Why we did this audit

- Once an aquatic species becomes extinct, it is lost forever, depriving future generations of its benefits. Such a loss also has broader effects on ecosystems and communities.

- Knowledge about aquatic species is essential to determining whether populations of species are at risk, which will help determine the appropriate strategies to protect them and help them recover.

- Halting or reversing the loss of species in decline or at risk of extinction calls for urgent action by the federal government and other jurisdictions. As time passes, the risks to these species tend to increase and, with them, the difficulties and costs involved in their recovery—a burden that should not be placed on future generations.

- Public awareness about people’s responsibilities toward species at risk, and about government measures and activities to preserve species and their habitat, are critical to protecting aquatic species.

Our findings

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada focused its knowledge-building on species of commercial value. There was little knowledge-building on data-deficient species as the focus was on knowledge-building on fish stock.

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada had yet to develop listing advice for half of the aquatic species assessed as being at risk and analysis to support listing advice was sometimes unclear or insufficient.

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada informed the public about species protection but did not assess the effectiveness of its outreach activities.

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada did not have enough capacity to manage enforcement effectively.

Key facts and figures

- Biodiversity loss has reached crisis proportions on land and in both freshwater and marine environments. Canada, along with its international partners, has recognized the urgent need to halt and reverse the loss of biodiversity. However, some aquatic species are already extinct, while the populations of many others are declining.

- It took an average of 3.6 years to complete the listing process of aquatic species. Some advice took much longer. In November 2017, Environment and Climate Change Canada put a policy in place calling for a Governor in Council decision on whether to list aquatic species under the Species at Risk Act within 2 to 3 years.

- The listing decision process should have been completed for 44 species at risk within the required time frame, but it was completed for only 5 species.

- Although the Ontario and Prairie region is responsible for managing most of the freshwater species listed under Schedule 1 of the Species at Risk Act, it had the lowest number of fishery officers. This region had only 6% of all the department’s fishery officers as at December 2021, managing 45% of all the listed species under review. All of the species in this region were freshwater species.

Highlights of our recommendations

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada should reduce delays in providing advice on whether to list aquatic species at risk. This would allow the Governor in Council to make listing decisions under the Species at Risk Act sooner, which could make additional protection measures available.

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada should ensure that enough staff are available to enforce the general prohibitions and critical habitat prohibitions of the Species at Risk Act, and the fish and fish habitat protection provisions of the Fisheries Act, for all listed marine or freshwater species.

Please see the full report to read our complete findings, analysis, recommendations and the audited organizations’ responses.

Environment and Climate Change Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada have responsibilities related to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 14 (Life Below Water): “Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development.” The departments also have responsibilities related to Goal 15 (Life on Land), and specifically Target 15.5: “Take urgent and significant action to reduce the degradation of natural habitats, halt the loss of biodiversity and, by 2020, protect and prevent the extinction of threatened species.”

Visit our Sustainable Development page to learn more about sustainable development and the Office of the Auditor General of CanadaOAG.

Exhibit Highlights

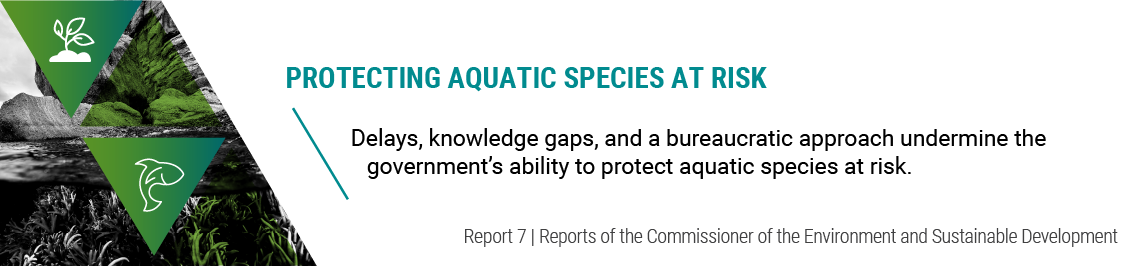

Risk status of aquatic species we examined as at November 2021, as assessed by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada

Source: Adapted from the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada and information from Environment and Climate Change Canada

Text version

This chart shows the risk status of freshwater and marine aquatic species as at November 2021, as assessed by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. The chart shows how many species are in each risk category and presents the categories in order of increasing risk to species.

Forty freshwater species and 28 marine species were assessed as not at risk—that is, they were evaluated and found not to be at risk of extinction given the current circumstances.

Thirty-six freshwater species and 27 marine species were assessed as of special concern—that is, they may become threatened or endangered because of a combination of biological characteristics and identified threats.

Thirty-eight freshwater species and 25 marine species were assessed as threatened—that is, they are likely to become endangered if nothing is done to reverse the factors leading to their extirpation or extinction.

Forty-nine freshwater species and 52 marine species were assessed as endangered—that is, they face imminent extirpation or extinction.

Three freshwater species were assessed as extirpated—that is, they no longer exist in the wild in Canada, but exist elsewhere. No marine species were assessed as extirpated.

Eight freshwater species and 1 marine species were assessed as extinct—that is, they no longer exist.

Twenty-two freshwater species and 15 marine species were assessed as data-deficient—that is, the information that is available about these species is insufficient to be able to assess their risk status.

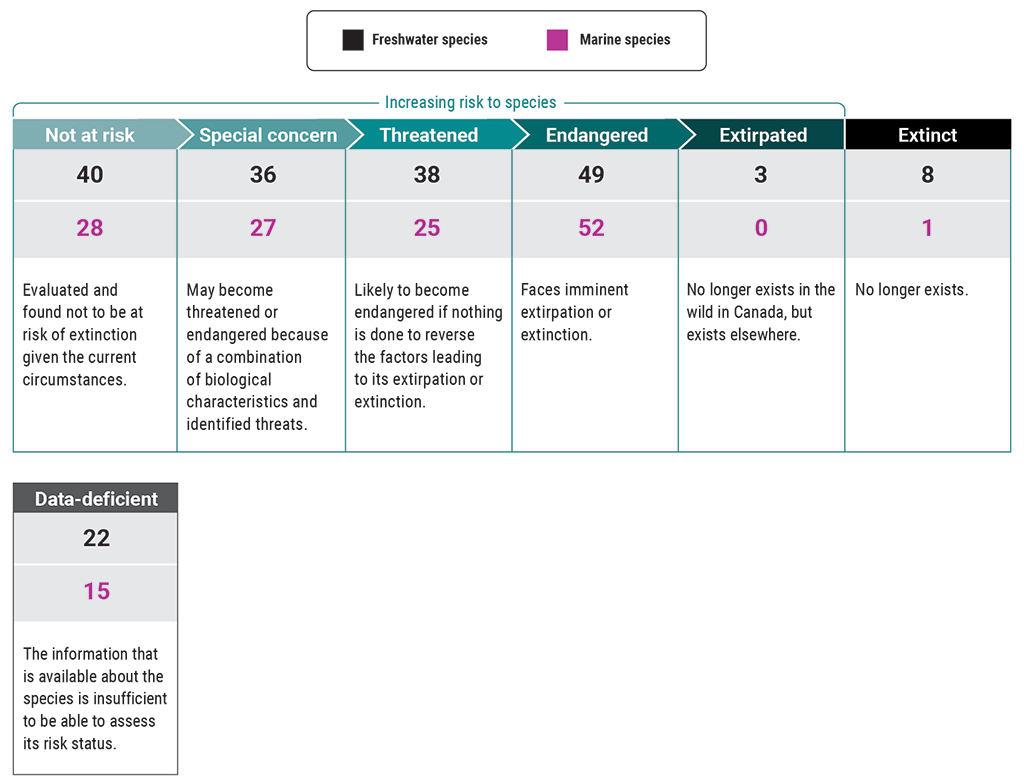

Process for developing listing advice and making recommendations for aquatic species at risk

Source: Based on information provided by Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Text version

This chart shows the process that Fisheries and Oceans Canada follows to develop listing advice, the process that ministers follow to make listing recommendations, and the process that the Governor in Council follows to decide whether to list species under the Species at Risk Act.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada develops listing advice as follows:

- First, the department assesses recovery potential using additional scientific information about the species being assessed, when available.

- Second, the department develops management scenarios to manage species, such as listing and not listing.

- Third, the department conducts socio-economic analysis of the impact, costs, and benefits of management scenarios.

- Fourth, the department holds public consultations with interested and affected Indigenous groups and other stakeholders.

- Finally, the department develops advice whether to list species under the Species at Risk Act on the basis of the preceding steps of the listing process.

Ministers then make listing recommendations as follows:

- The Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard provides listing advice to the Minister of Environment and Climate Change.

- The Minister of the Environment and Climate Change makes recommendations to the Governor in Council.

The Governor in Council then decides whether to list species under the Species at Risk Act as follows:

- If the Governor in Council decides to list, the species is added to Schedule 1 of the Species at Risk Act.

- If the Governor in Council decides to refer back, the decision is referred to the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada.

- If the Governor in Council decides not to list, the decision is deferred to Fisheries and Oceans Canada for alternative approaches.

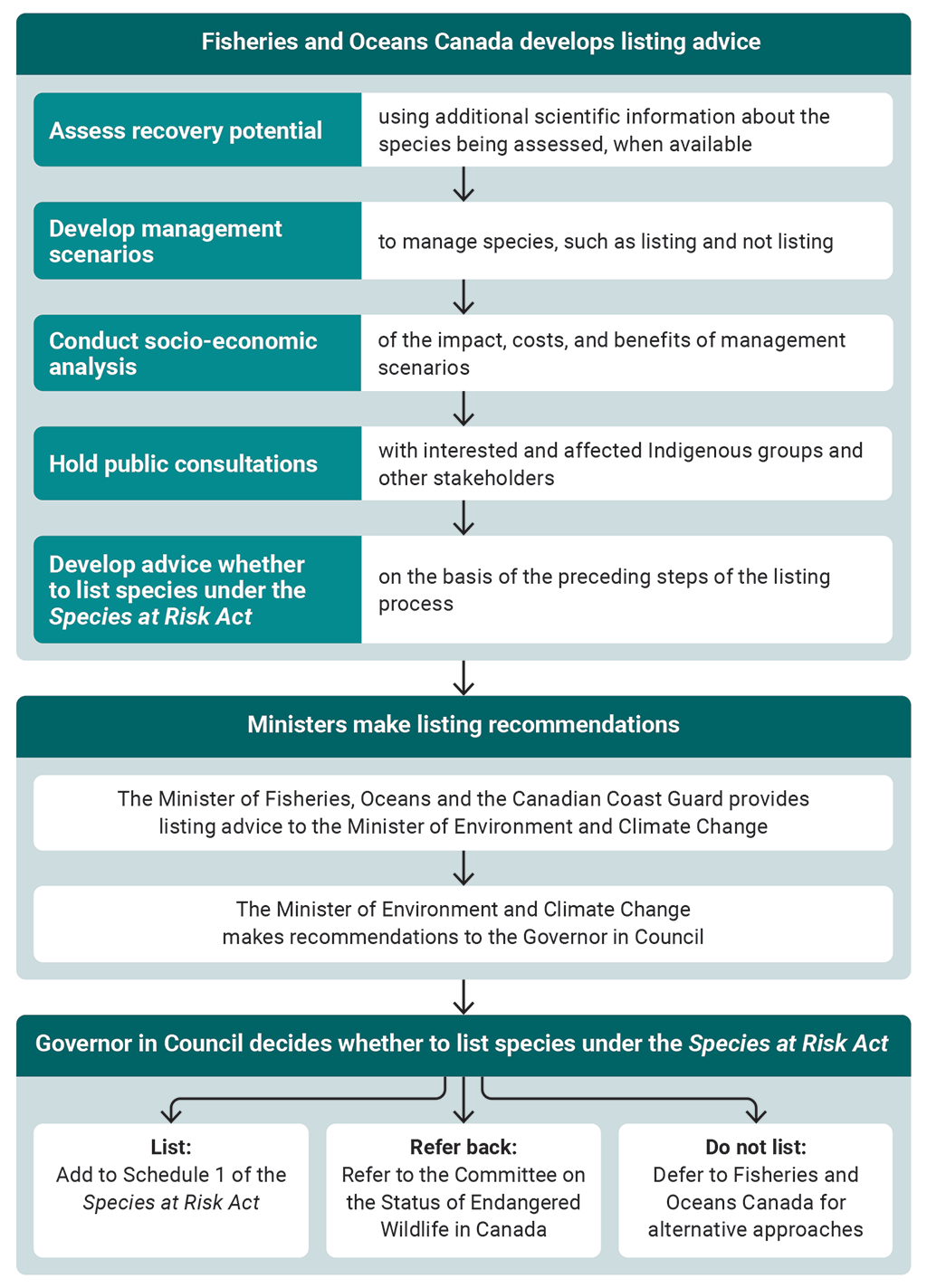

Fisheries and Oceans Canada took a long time to develop listing advice for several aquatic species

Source: Based on information provided by Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Text version

This graph shows the number of years that Fisheries and Oceans Canada took to provide listing advice for the species for which it took the longest time to provide advice. The data is presented in descending order as follows:

- It took 11.0 years to provide advice for the fawnsfoot, which is a freshwater mussel.

- It took 10.0 years to provide advice for the Lake Utopia large-bodied population of rainbow smelt, which is a freshwater fish.

- It took 9.6 years to provide advice for the redside dace, which is a freshwater fish.

- It took 7.9 years to provide advice for the hickorynut, which is a freshwater mussel.

- It took 7.9 years to provide advice for the Great Lakes–upper St. Lawrence populations of the silver lamprey, which is a freshwater fish.

The average time to provide listing advice for all species identified as being at risk was 3.6 years.

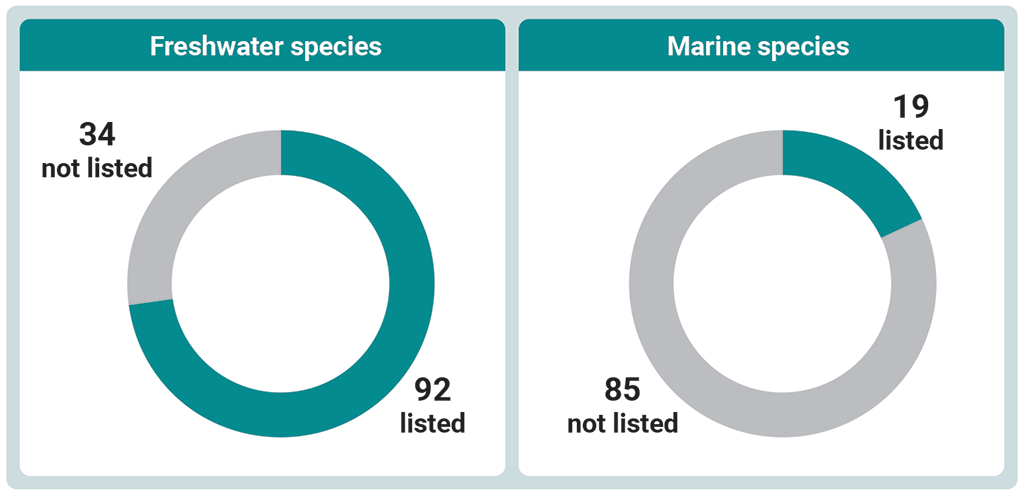

Species at Risk Act listing status for aquatic species covered by this audit

Source: Based on information provided by Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Text version

These 2 pie charts show the listing status for freshwater and marine species.

Thirty-four freshwater species are not listed, and 92 freshwater species are listed.

Eighty-five marine species are not listed, and 19 freshwater species are listed.

Note: “Not listed” includes species for which the decision was not to list and species for which the decision to list was pending.

Fewer fishery officers were allocated to the Ontario and Prairie region, which is responsible for managing the majority of listed freshwater species

Source: Based on information provided by Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Text version

This map shows the number of full-time-equivalent fishery officers and the number of listed species that we examined for the following regions in Canada:

- the Pacific region

- the Ontario and Prairie region, which includes some responsibilities for the Arctic region

- the Quebec, Gulf, and Newfoundland and Labrador regions

- the Maritimes region

In the Pacific region, there are 151 full-time-equivalent fishery officers, which is 29% of the total in Canada. There are also 37 listed species that we examined, which is 33% of the total in Canada. The 37 listed species consist of 26 freshwater species and 11 marine species.

In the Ontario and Prairie region, which includes some responsibilities for the Arctic region, there are 30 full-time-equivalent fishery officers, which is 6% of the total in Canada. There are also 50 listed species that we examined, which is 45% of the total in Canada. The 50 listed species are all freshwater species; there are no marine species.

In the Quebec, Gulf, and Newfoundland and Labrador regions, there are 232 full-time-equivalent fishery officers, which is 44% of the total in Canada. There are also 13 listed species that we examined, which is 12% of the total in Canada. The 13 listed species consist of 10 freshwater species and 3 marine species.

In the Maritimes region, there are 114 full-time-equivalent fishery officers, which is 22% of the total in Canada. There are also 11 listed species that we examined, which is 10% of the total in Canada. The 11 listed species consist of 6 freshwater species and 5 marine species.

Note: There are 527 full-time-equivalent fishery officers and 111 listed species in the scope of the audit in total.

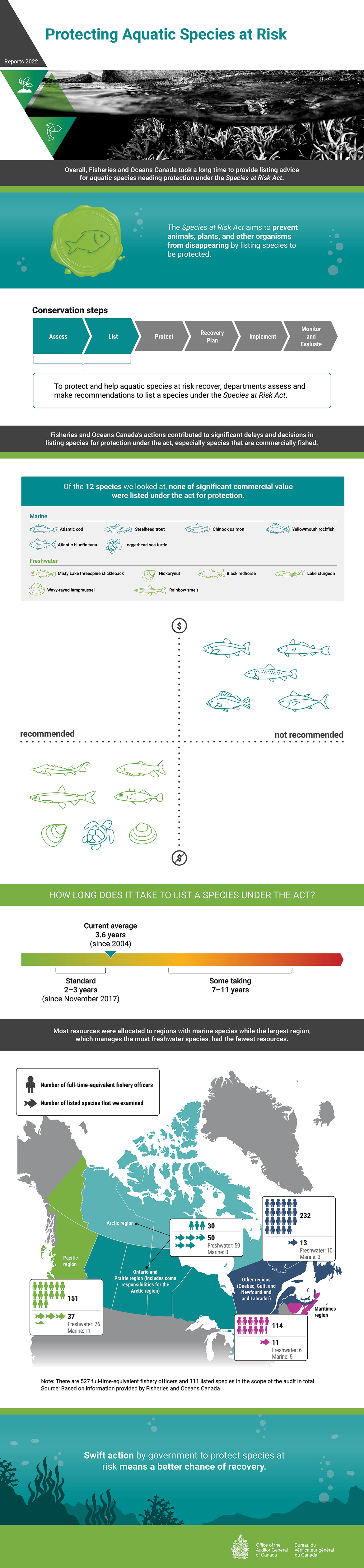

Infographic

Text version

This infographic presents findings from the 2022 audit report on protecting aquatic species at risk.

Overall, Fisheries and Oceans Canada took a long time to provide listing advice for aquatic species needing protection under the Species at Risk Act.

The Species at Risk Act aims to prevent animals, plants, and other organisms from disappearing by listing species to be protected.

Conservation steps

To protect and help aquatic species at risk recover, departments assess and make recommendations to list a species under the Species at Risk Act. These actions fall under the first 2 conversation steps of “assess” and “list.”

Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s actions contributed to significant delays and decisions in listing species for protection under the act, especially species that are commercially fished.

Of the 12 species we looked at, none of significant commercial value were listed under the act for protection. The 5 species of significant commercial value that were not listed under the act are the Atlantic cod, the steelhead trout, the chinook salmon, the yellowmouth rockfish, and the Atlantic bluefin tuna. These are all marine species. The other 7 species we looked at, which were not of significant commercial value, were listed under the act. Six are freshwater species and 1 is a marine species. The freshwater species are the Misty Lake threespine stickleback, the hickorynut, the black redhorse, the lake sturgeon, the rainbow smelt, and the wavy-rayed lampmussel, and the 1 marine species is the loggerhead sea turtle.

How long does it take to list a species under the act?

The standard is 2 to 3 years (since November 2017). The current average is 3.6 years (since 2004). Some take 7 to 11 years.

Most resources were allocated to regions with marine species while the largest region, which manages the most freshwater species, had the fewest resources.

The largest region is the Ontario and Prairie region, which includes some responsibilities for the Arctic region. In this largest region, there are 30 full-time-equivalent fishery officers and 50 listed species that we examined. The 50 listed species are all freshwater species; there are no marine species.

In the Pacific region, there are 151 full-time-equivalent fishery officers and 37 listed species that we examined. The 37 listed species consist of 26 freshwater species and 11 marine species.

In the Quebec, Gulf, and Newfoundland and Labrador regions, there are 232 full-time-equivalent fishery officers and 13 listed species that we examined. The 13 listed species consist of 10 freshwater species and 3 marine species.

In the Maritimes region, there are 114 full-time-equivalent fishery officers and 11 listed species that we examined. The 11 listed species consist of 6 freshwater species and 5 marine species.

Note: There are 527 full-time-equivalent fishery officers and 111 listed species in the scope of the audit in total.

Source: Based on information provided by Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Swift action by government to protect species at risk means a better chance of recovery.

Related information

Tabling date

- 4 October 2022

Related audits

- 2019 Spring Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the Parliament of Canada

Report 1—Aquatic Invasive Species - 2018 Fall Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the Parliament of Canada

Report 2—Protecting Marine Mammals - 2018 Spring Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the Parliament of Canada

Report 3—Conserving Biodiversity

Parliamentary hearings