2014 Fall Report of the Auditor General of Canada Chapter 1—Responding to the Onset of International Humanitarian Crises

2014 Fall Report of the Auditor General of Canada

Chapter 1—Responding to the Onset of International Humanitarian Crises

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Observations and Recommendations

- Choosing humanitarian assistance partners

- Basing humanitarian assistance on need

- Providing timely humanitarian assistance

- Demonstrating consistency with objectives

- Aid provided through the international humanitarian assistance program was mainly used in a manner consistent with project objectives

- Aid provided through other programs was used in a manner consistent with objectives, but some short-term project objectives were not met

- Federal spending exceeded government commitments to match funds

- Canadian Armed Forces capabilities deployed to the Philippines played a useful role, but several factors limited the amount of assistance delivered

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- Appendix—List of recommendations

- Exhibits:

Performance audit reports

This report presents the results of a performance audit conducted by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada under the authority of the Auditor General Act.

A performance audit is an independent, objective, and systematic assessment of how well government is managing its activities, responsibilities, and resources. Audit topics are selected based on their significance. While the Office may comment on policy implementation in a performance audit, it does not comment on the merits of a policy.

Performance audits are planned, performed, and reported in accordance with professional auditing standards and Office policies. They are conducted by qualified auditors who

- establish audit objectives and criteria for the assessment of performance;

- gather the evidence necessary to assess performance against the criteria;

- report both positive and negative findings;

- conclude against the established audit objectives; and

- make recommendations for improvement when there are significant differences between criteria and assessed performance.

Performance audits contribute to a public service that is ethical and effective and a government that is accountable to Parliament and Canadians.

Introduction

Background

1.1 Humanitarian crises are situations that may require help from the international community to save lives, alleviate suffering, and protect human dignity. Millions of people around the world affected by humanitarian crises rely on assistance from the international community, including Canada, when their governments lack the capacity or will to respond. Even with several billion dollars in humanitarian assistance contributed by governments and other donors worldwide each year—including an average of $567 million annually by the Government of Canada over the last five years, as reported by Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada—humanitarian needs exceed resources. It is therefore important that limited resources be allocated in a timely manner to where they are needed most, and that there is accountability for how they are used.

International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement—A large, global humanitarian network consisting of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (which is composed of national societies, including the Canadian Red Cross Society) and the International Committee of the Red Cross.

1.2 Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada responds to international humanitarian crises and is responsible for coordinating the federal government’s response. Most of the financial assistance provided upon the onset of humanitarian crises is through the Department’s international humanitarian assistance program to United Nations (UN) humanitarian agencies, the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). For significant crises, the Department may commit to match dollar for dollar eligible contributions by individuals to Canadian charities.

1.3 Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada applies the Principles and Good Practice of Humanitarian Donorship in providing humanitarian assistance. Along with several other countries, Canada collaborated to establish these principles, which include humanitarian principles adopted by the UN (Exhibit 1.1).

Exhibit 1.1—Humanitarian principles adopted by the United Nations

Humanity: The centrality of saving human lives and alleviating suffering wherever it is found.

Impartiality: The implementation of actions solely on the basis of need, without discrimination between or within affected populations.

Neutrality: Humanitarian action must not favour any side in an armed conflict or other dispute where such action is carried out.

Independence: The autonomy of humanitarian objectives from political, economic, military, or other objectives that any actor may hold with regard to areas where humanitarian action is being implemented.

Source: Principles and Good Practice of Humanitarian Donorship, Good Humanitarian Donorship Initiative, 2003, and United Nations (A/RES/46/182), 1991, and (A/RES/58/114), 2003

1.4 From time to time, the Canadian Armed Forces participate in humanitarian operations abroad. The Government of Canada calls upon the Canadian Armed Forces to use its capabilities—personnel, equipment, and supplies—for humanitarian operations to save lives, alleviate suffering, and protect human dignity. When the Canadian Armed Forces are so deployed, it is in coordination with Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada.

1.5 The international humanitarian system through which the federal government channels its humanitarian assistance is centred on the UN humanitarian organizations, the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, and key NGOs. The UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs coordinates international emergency responses with the consent of affected nations. Humanitarian organizations are grouped into clusters that work together with affected nations’ governments to develop response plans under the overall direction of a UN Humanitarian Coordinator. For example, there is a cluster for shelter needs, and another for sanitation, water, and hygiene needs.

1.6 At the onset of a large crisis, the UN facilitates and coordinates an assessment of the situation and humanitarian needs. UN organizations and other participating aid organizations use this information to plan their responses to the crisis, which may include increasing the scale of existing humanitarian aid operations and developing new relief projects. The UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs then coordinates the development of an appeal document to potential donors that sets out, among other things, an assessment of the humanitarian needs, response priorities, and the proposed activities, projects, and associated funding requests of participating aid organizations. Government donors, such as Canada, review the appeal document and decide whether to make voluntary contributions to selected aid organizations, operations, and projects. Canada typically enters into specific grant agreements with selected partners. Canada’s financial response is not limited to UN appeals; it also funds appeals of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and proposals submitted directly by NGOs. Until donor funds are received, aid organizations mobilize using internal and other funding sources, such as the United Nations Central Emergency Response Fund.

Focus of the audit

1.7 This audit focused on the federal government’s response to the onset of humanitarian crises in developing countries ranging from sudden natural disasters, such as earthquakes, to rapid increases in humanitarian needs during complex or prolonged crises, such as the displacement of people due to conflict. Because the audit focused on the onset of crises, it did not examine longer-term federal responses.

1.8 Our audit objectives were to determine

- whether Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada provided humanitarian assistance upon the onset of humanitarian crises through appropriate partners using a needs-based approach in a timely manner; and

- whether Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada and National Defence could demonstrate that the assistance they provided upon the onset of humanitarian crises abroad was used in a manner consistent with the objectives of the projects and missions supported.

1.9 The audit examined the federal government’s response to the onset of eight humanitarian crises. This included a sample of 36 projects funded by Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada’s international humanitarian assistance program, and 6 projects funded by the Department’s other programs, as well as assistance provided by National Defence through its deployment of the Canadian Armed Forces in response to Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines. The first audit objective was examined only regarding spending through the international humanitarian assistance program. The program names, numbers of projects selected, and amounts of federal funding are in Exhibit 1.2.

Exhibit 1.2—Federally funded projects and defence operations examined in this audit

| Number of projects and defence operations | Federal program | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| 36 | Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada: International Humanitarian Assistance Program, including the Emergency Disaster Assistance Fund | $124,997,000 |

| 2 | Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada: Global Peace and Security Fund | $11,500,000 |

| 2 | Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada: Bilateral development assistance programs | $6,000,000 |

| 2 | Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada: Canada Fund for Local Initiatives | $104,000 |

| 1 | National Defence: Canadian Armed Force’s Humanitarian operation | $29,216,000 |

| 43 | Total value of projects and operations examined | $171,817,000 |

Source: Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada, and National Defence (unaudited data). National Defence’s figures are incremental costs (additional costs incurred as a direct result of participating in the operation) and are not final. Figures cover the period of 1 April 2011 to 31 December 2013.

1.10 The audit covered the period from 1 April 2011 to 31 December 2013. During that period, the Canadian International Development Agency and Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada were amalgamated into a single entity, Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada. In this report we use only the Department’s current name when referring to its actions and the actions of its predecessor organizations. More details on the audit objectives, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this chapter.

Observations and Recommendations

Choosing humanitarian assistance partners

1.11 According to Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada, a key control in ensuring the effectiveness of the international humanitarian assistance program is to fund appropriate partners. It does this by choosing partners with demonstrated capacity to deliver aid. This capacity consists of a breadth of experience in delivering humanitarian aid, participation in the international humanitarian system, and capacity on the ground to deliver in the given situation. We examined whether the Department takes capacity into account when choosing partners.

1.12 Overall, we found that the Department assesses the capacity of its partners and is working to strengthen its assessment practices. This is important because it helps ensure that partners have the capacity to use departmental funding effectively and carry out projects successfully.

Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada assesses the capacity of its partners and is working to strengthen its assessment practices

1.13 We looked at Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada’s process for assessing the capacity of its partners for each of the 36 approved international humanitarian assistance projects in our sample. The partners that the Department mainly funds are the few large multilateral, international, and non-governmental organizations that have a presence worldwide and that respond to most international humanitarian crises. The Department has worked with them for many years. Nonetheless, the Department conducts periodic assessments of each organization’s overall capacity and has a practice in place to conduct a specific assessment for projects being considered for funding.

1.14 In the Spring 2013 Auditor General’s report, Chapter 4, Official Development Assistance Delivered through Multilateral Organizations, we reported that Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada had adequate processes for assessing the overall capacity of the multilateral organizations it funds. These processes include Canadian government representation and oversight on governing bodies, periodic reviews, and completion of due diligence assessments.

1.15 Since 2011, the Department has been using Fiduciary Risk Evaluation Tools (FRETs) to evaluate each of the partners it funds through the international humanitarian assistance program, both multilateral organizations and NGOs. The tools assess the level of risk for governance and stability, history of results, financial viability, and risks of corruption and fraud. We found that evaluations using these tools had been completed on all the organizations funded for projects in our sample undertaken after the tools were implemented.

1.16 The Department has 10 minimum requirements for international humanitarian assistance funding. For example, an NGO must have at least 5 years of experience in providing international humanitarian assistance, and must adhere to the Code of Conduct for the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) in Disaster Relief. However, the FRETs do not specifically address all of the 10 minimum requirements. Therefore, in August 2013, the Department began requiring NGOs to submit institutional profiles to confirm that they met all 10 requirements, including the key capacity requirements, before their proposals would be considered for humanitarian assistance programming. The Department has received institutional profiles from many of the NGOs that undertook projects within our sample. However, the Department had not yet reviewed these profiles to verify that the 10 requirements had been met.

1.17 Following the onset of a humanitarian crisis, when deciding which parts of an appeal to fund, the Department assesses the capacity of multilateral partners for the specific situation, because organizations do not have equal capacity and access in every country. NGOs send project proposals to the Department, which has published guidelines for NGOs that are preparing proposals that require them to provide specific information on capacity.

1.18 For the 36 projects we examined, we looked at departmental decision documents to determine whether they contained assessments concluding that proposed partners had adequate capacity. We found that the decision documents for 28 of the projects contained such assessments.

1.19 Three of the projects for which we did not find assessments of partner capacity were disbursements from the Emergency Disaster Assistance Fund, which is funded by the Department and administered by the Canadian Red Cross Society. (The Fund is described in paragraphs 1.35 and 1.36.) The Department has recently revised the criteria for such disbursements to require the Red Cross to confirm that, among other things, the receiving national Red Cross society in the affected country has adequate capacity to use the funds effectively. We did not examine the use of this criterion because it was not in effect for the crises we examined where this fund was used. Of the five other projects for which there was no assessment of capacity in decision documents, four were part of the response to a single crisis, the 2011 Central American flooding crisis. The Department told us that the absence of an assessment in the decision documents for those four projects was an administrative oversight. We noted that for projects with other partners in this same crisis, the decision documents included capacity assessments.

1.20 To test whether the Department’s conclusions that proposed partners had adequate capacity were correct, we examined project reports to determine whether there were any capacity limitations that had an impact on project delivery. We found that capacity issues affected a small number of activities, but did not have a significant effect on the overall conduct or results of the projects.

1.21 As well, to confirm that the Department considered capacity in choosing partners and projects to fund, we looked at its rationale for rejecting proposals received from NGOs. We found that for 12 percent of rejected proposals, the main reason for rejection was a concern that the NGO lacked capacity in the given situation.

Basing humanitarian assistance on need

1.22 The humanitarian principles to which Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada subscribes state that humanitarian assistance should be allocated primarily based on need. We therefore examined departmental decision and project documents to determine whether the Department selected projects in a manner focused on the assessed needs of the crisis-affected populations, and allocated funding based on need in a transparent manner.

1.23 Overall, we found that the Department considered the needs of affected populations and chose projects that were expected to help address those needs, but the basis for how much assistance was allocated to crises and individual projects was often not clearly documented. This is important because, although the Department takes needs into account when choosing projects, the Department could not demonstrate how various factors were applied to determine the amount of funding provided.

Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada chooses humanitarian projects based on needs of crisis-affected populations

ReliefWeb—An Internet-based information service provided by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs that disseminates situation reports, assessments, appeals, evaluations, analyses, maps, and other information on crises to help humanitarian organizations make informed decisions and plan effective assistance responses.

1.24 Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada uses several sources when assessing whether project proposals reflect the needs of a crisis. These include United Nations (UN) and Red Cross appeal documents, situation and needs assessment reports produced by aid agencies posted on ReliefWeb, and reports from experienced partners in the field, Canadian embassy staff where there is a Canadian presence, and the Canadian missions to the UN. As well, the Department’s guidelines to non-governmental organizations (NGOs) for preparing project proposals include the requirement to demonstrate how proposed project activities will address the needs of the crisis-affected population.

1.25 In our review of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada’s decision documents for 36 humanitarian projects it funded, we found that officials considered needs assessments in choosing to fund each project. The documents demonstrated that officials concluded that the activities of the projects to be funded would help address the needs of the crisis-affected population.

1.26 To confirm that the Department used an assessment of need when choosing partners and projects to fund, we also looked at its rationale for rejecting proposals. We found that, for the crises we examined, half of rejected proposals from NGOs were rejected because the Department concluded that they did not adequately demonstrate that they addressed priority needs. For example, one rejected proposal requested funding for pest control, which the Department concluded did not address the priority needs of the situation.

It was often not clear how Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada determined the amount of funding to provide

1.27 At the same time as determining the needs of populations affected by a crisis, Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada determines the amount of assistance to provide. The Department develops a package of assistance usually including a total funding allocation, as well as funding amounts for specific projects. There may be several packages over the course of a crisis. We examined whether it was clear how the Department determined the amount of funding provided and we reviewed whether the method used was consistent with the Principles and Good Practice of Humanitarian Donorship.

1.28 We found that, while the decision documents approving packages of assistance mentioned factors taken into account, they did not show how the amounts for the crises as a whole were determined using those factors. Examples of factors presented were:

- the proportion of the amount of the appeal, sometimes compared with other donating countries;

- whether the amount was sufficient for a partner to scale up operations, or to make up a shortfall in donations;

- the number of people in need of assistance and the number expected to be helped by the selected projects; and

- the relative need across countries in an affected region.

1.29 Department officials explained that much of the analysis used to determine funding amounts was not documented, with only the conclusions reflected in the decision documents. We found varying degrees of clarity in those documents for how the Department determined the amount of its contribution to each of our 36 sample projects.

- For 3 disbursements from the Emergency Disaster Assistance Fund to support emergency operations of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), the amount was calculated through a sliding scale formula based on the type and size of the operation.

- For 18 projects with NGOs, the amount allocated by Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada was based on amounts requested in the proposals submitted by the NGOs. However, sometimes these amounts were finalized through discussions between the Department and the NGOs.

- For 15 projects with the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, the International Committee of the Red Cross, and five multilateral organizations, we were unable to verify how the amounts were determined. For example, the Department contributed $1 million to a $25-million project to which other countries contributed; however, the project remained underfunded. Departmental decision documents did not show how the amount of $1 million was chosen.

1.30 We examined the factors taken into account in allocating funds to determine whether they considered the needs of the affected population and we reviewed them for consistency with the Principles and Good Practice of Humanitarian Donorship adopted by Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada. While we found that the factors take into account needs and are consistent with the principles, it was not clear how they were applied. For example, the need to make a proportional contribution was mentioned in many documents, but the percentage funded by the Department in relation to the appeal varied. One decision document stated that the Department typically responds with funding of 3 to 5 percent for an appeal, but other such documents show that it provided approximately 2.5 percent of the requirements for the East Africa drought for 2011 and 7.5 percent of the requirements for the Philippines Typhoon Haiyan in 2013. The Department could not demonstrate how the factors were applied to determine the funding amount because the application of the factors was not clearly documented.

1.31 Recommendation. Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada should document how the dollar amounts of its humanitarian funding allocations are determined, including key calculations and rationale.

Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada’s response. Agreed. Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada strives to allocate its humanitarian funding in line with the Principles and Good Practice of Humanitarian Donorship. The Department will work to better document the rationale behind the dollar amounts proposed for humanitarian funding recommendations.

Providing timely humanitarian assistance

1.32 Providing a timely response is one of the key goals of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada’s international humanitarian assistance program. We therefore looked at the Department’s key tools, policies, and procedures for responding to crises. Because the Department does not measure the overall timeliness of its processes, we examined whether its responses to our sample projects were timely. We also reviewed the Department’s contributions to selected emergency response funds and noted that these help partners respond rapidly at the onset of crises.

1.33 Overall, we found that while the Department can respond quickly, response times vary and the Department does not measure the overall timeliness of its own processes. This is important because slower responses can slow the provision of assistance to affected populations.

Contributions to emergency response funds help partners respond rapidly

1.34 Two international humanitarian assistance tools are the Emergency Disaster Assistance Fund and the Central Emergency Response Fund. These funds support immediate response activities of the Red Cross movement and United Nations (UN), respectively, while the needs assessment and appeals processes are being conducted and before donors begin to contribute. We reviewed whether these two funds were providing funding in a timely manner.

1.35 Emergency Disaster Assistance Fund (EDAF). Through this fund, the Canadian Red Cross Society administers advance funding provided by Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada to support humanitarian operations of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies in responding to small- and medium-scale crises. To use the fund, the Canadian Red Cross Society notifies the Department of the amount required and provides an assessment against agreed-upon criteria. EDAF funding is small, but it is used frequently. According to the Department, in the 2012–13 fiscal year, more than $1.3 million in EDAF funds was used to respond to 30 crises globally.

1.36 The Canadian Red Cross Society requested use of EDAF funds for three crises included in the audit. We found that in all three cases, EDAF operated as intended. In each case the Canadian Red Cross Society provided Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada with an assessment against the criteria. The Department permitted the Society to proceed within 24 hours and the funds were subsequently used as part of the IFRC’s emergency response.

1.37 Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF). The CERF is a large multi-donor fund administered by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. It spent US$499 million in 2013. CERF’s funding is used for new or rapidly deteriorating humanitarian crises that involve a response by the UN. Following the onset of crises, CERF provides funds to UN agencies and the International Organization for Migration, which use these funds to finance their response. A portion of CERF’s funding is also used to help underfunded crises that have not attracted enough donor contributions. Under a multi-year agreement to contribute to CERF, Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada will provide CAN$88.2 million during the 2012–13 to 2014–15 fiscal years.

1.38 Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada usually contributes annually to the CERF, and does not play a direct role in the UN’s decisions to use the fund. We therefore reviewed whether CERF operated in accordance with the Department’s timeliness expectations when it provided funding. We looked at the documentation for the Department’s decisions to support the fund, as well as CERF reports and the reports of UN agencies in receipt of those funds for crises included in our sample. We found that, overall, the reporting showed that the CERF was a timely source of funding to UN organizations for crisis response.

1.39 Once CERF transfers funds to the UN organizations, these organizations are responsible for the use of those funds. In some cases, the UN organizations use partner organizations to implement the response in the crisis-affected country. A UN evaluation reported that there were delays in the disbursements from UN organizations to their implementing partners. Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada has asked the UN to encourage its organizations to transfer funds to implementing partners more quickly.

Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada’s responses are not always timely

1.40 Where Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada provides funding through its international humanitarian assistance program to a crisis directly, it follows four main steps:

- Analyze information on the situation and funding requests prepared by partners to determine an appropriate package of aid projects to recommend for funding.

- Identify sources of funding.

- Obtain approval for the aid package.

- Enter into grant agreements with partners.

1.41 The Department commits to responding to funding requests in a timely manner. It has established some guidelines for what constitutes a timely response in certain circumstances, but there is no single definition of timeliness. We examined whether there were delays in responding to funding requests.

1.42 Even if Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada conducts its analysis and obtains approval to make contributions quickly, whether the response is timely relative to the needs of the crisis may be affected by factors beyond its control. Such factors include the timing of when the affected nation requests international assistance and the degree to which aid organizations are able to access the affected populations. For example, during the 2011 East African drought and the 2012 food and nutrition crisis in Africa’s Sahel region, the international aid community noted that the response was affected by the timing of recipient governments’ requests for assistance and restrictions imposed by armed militants in Somalia. In Syria, access to affected populations remains a key challenge.

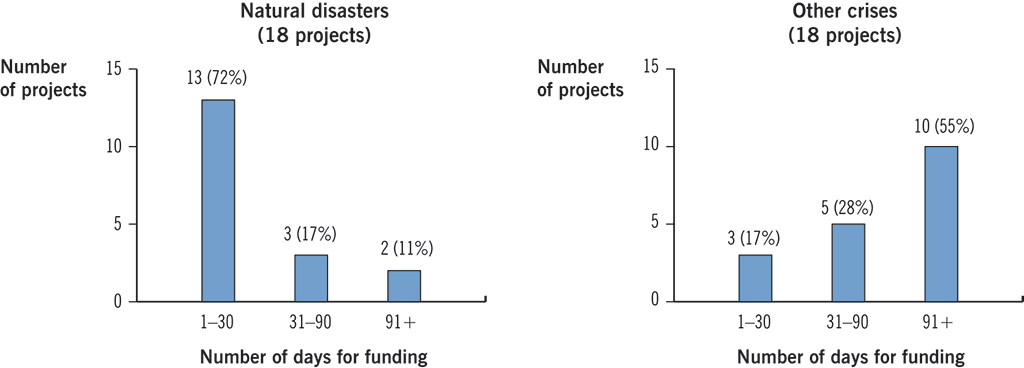

1.43 We found that for 13 of the 18 sample projects involving natural disasters, the Department completed its analysis, determined a recommended package of aid projects, obtained approvals, and entered into grant agreements within 30 days of either international appeals or receiving proposals from partners (Exhibit 1.3). However, for the other 5 cases, the process took longer.

Exhibit 1.3—The timeliness of funding for 36 selected projects varied

Note: The “number of days for funding” is the length of time for the Department to enter into grant agreements with partners, starting from the issue of applicable appeals, increases to existing appeals, or receipt of proposals from partners in cases where there is no applicable appeal.

1.44 Responding to other types of crises generally took longer than responding to natural disasters. To some extent this reflected the complex and evolving situation in these crises, but the response time for the 18 sample projects from these kinds of crises varied considerably. The approval process took less than 90 days for 8 projects, while it took between 3 and 11 months for the other 10 projects.

1.45 There were several causes of the longer response times, including

- lengthy decision processes,

- obtaining approval for additional funding, and

- conducting additional due diligence to ensure that Canadian funds could not be used to benefit terrorist groups.

1.46 We reviewed project documentation to determine whether longer funding response times had an impact on the delivery of assistance to the crisis-affected population. Longer funding response times did not have an impact when, for example, funding was to a multi-donor project to which other donors had already contributed funds. However, in other instances, delays in funding contributed to delays in the delivery of assistance to the affected population. For example, one project to help restore health care services started five months later than planned by the partner.

1.47 Even though timeliness is integral to an effective response to the onset of humanitarian crises, and responses are not always timely, the Department does not measure the overall timeliness of its own processes. Doing so would help the Department identify opportunities to improve its response times and to demonstrate that it responds in a timely manner.

1.48 Recommendation. Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada should monitor and assess its timeliness in responding to the onset of crises to identify opportunities for improving its response time.

Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada’s response. Agreed. Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada agrees that timely funding of humanitarian operations is critical to saving lives and alleviating human suffering, and will continue to identify opportunities for improving its response time.

Demonstrating consistency with objectives

1.49 We examined whether Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada and the Canadian Armed Forces could demonstrate that the assistance they provided at the onset of humanitarian crises abroad was used in a manner consistent with the objectives of the projects and missions supported.

1.50 Overall, we found that assistance provided was mainly used in a manner consistent with objectives, but some objectives had not been achieved for development projects. We also found that there are opportunities for Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada to improve its assessment of the results of its international humanitarian assistance projects. This is important because assessing results helps the Department to demonstrate that funding is achieving objectives, to monitor its partners’ capacity, and to use that information to challenge its partners to improve. Improvements to the Department’s risk management practices for development projects may also help it ensure that objectives are met. In addition, the Canadian Armed Forces’ operation in response to Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines in 2013 was undertaken in a manner consistent with its objectives for humanitarian operations and provided useful assistance but several factors limited the amount of assistance delivered.

Aid provided through the international humanitarian assistance program was mainly used in a manner consistent with project objectives

1.51 Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada funds humanitarian assistance in response to crises using grants under its international humanitarian assistance program. The Treasury Board Policy on Transfer Payments requires departments to demonstrate the effectiveness of grants.

1.52 As explained in paragraphs 1.11 to 1.21, a key control to ensure the effectiveness of the international humanitarian assistance program is to fund partners with demonstrated capacity to deliver aid. Other key controls are departmental monitoring of the results of individual projects through project reporting requirements, situation reports, and monitoring visits. As a final control, the results of this monitoring are to be consolidated at the end of the project in a management summary report to assess whether each project achieved its objectives. At the time of the audit, 24 of the 36 international humanitarian assistance program projects in our sample had been completed. However, management summary reports had been completed for only 2 of these projects.

1.53 As there were few management summary reports to review, we examined the underlying sources of information for summary reports that Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada had collected to determine whether the Department had assurance that its assistance was being used in a manner consistent with project objectives.

1.54 All the grant agreements between the Department and its partners for the sample projects required the partners to report on results achieved. The reporting requirements varied, and were not always clear, but generally consisted of an end-of-project report or an annual report. Though not required by the agreements we examined, some partners also produce progress reports. Where the Department contributed to projects with multiple donors, partners reported on what was achieved with the overall pool of funds. Reporting in this way on projects with multiple donors is intended to reduce the reporting burden on partners compared with reporting separately to each donor.

1.55 We looked at available reports for the 36 projects in our sample to determine whether Canadian funds were being used in a manner consistent with the objectives in departmental decision documents, grant agreements, and associated proposals or appeal documents. For 32 projects in our sample, we were able to make an assessment and found that 31 were consistent with objectives and 1 project was not carrying out activities consistent with objectives but the Department had agreed to a change in use of funds. Of the 31 projects that we found were consistent with objectives, 25 projects were complete at the time of our audit. The other 6 were ongoing but progress reports received by the Department at the time of our audit showed that they were carrying out the activities for which the funds were provided.

1.56 We were unable to assess 4 projects in our sample of 36 because the final project report was late for 1 project, 1 project had not met reporting requirements, results for 1 project were not shown separately in a broader annual report, and 1 ongoing project had not yet reached the stage of being required to provide the Department with a report.

1.57 We examined monitoring visit reports prepared by the Department to determine whether activities reported by partners were consistent with what departmental officials observed during their visits. The Department conducted monitoring visits that covered 9 projects in our sample of 36 international humanitarian assistance projects. Grant agreements for 25 projects stipulated that Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada has a right to conduct monitoring visits. The Department informed us that it may also conduct monitoring visits even when not stipulated in grant agreements. This was the case for 1 of the projects in our sample. The reports for the 9 visits overall showed that partners were carrying out activities in a manner consistent with the reporting on activities provided by the partners.

1.58 We also reviewed other reports that examined the results of the international humanitarian assistance program projects in our sample. These included evaluation, audit, and lessons learned reports produced by partners or third parties. The reports showed no indications that assistance provided by the Department had been used in ways contrary to project objectives.

1.59 Based on these various sources of information, we were satisfied that the Department could demonstrate that its funding was used in a manner consistent with objectives. However, several projects did not fully carry out all planned activities or deliver the entire planned level of output. For example, some projects did not help as many people as initially estimated. As well, we found that partners had requested extensions to the time frame for 11 of the 28 projects with end dates specified in the agreements. The original time frame was often one year, and the average extension was for three months. Some deviation from plans is likely when delivering humanitarian assistance, given the difficult and evolving conditions in which it is provided, and the incomplete information on which plans may have to be based in a crisis environment. This reinforces the need for the Department to know and understand how its projects have performed.

1.60 Without documented assessments, such as the management summary reports, the Department relies on the experience of project officers to track the performance of partners that it uses repeatedly over several years and crises. Assessing results in a more systematic way would strengthen the Department’s ability to demonstrate that its funding is achieving results, to monitor its partners’ capacity, and to use that information to challenge its partners to improve.

1.61 Recommendation. Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada should assess the results of the humanitarian assistance projects it funds in a manner that is useful for managing operations.

Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada’s response. Agreed. All of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada’s humanitarian partners provide reporting on an annual basis, which includes results achieved and lessons learned. Assessing those results is an integral part of the program management cycle. The Department will review its current approach to assessing results. Based on that review, it will adopt measures to ensure that it better captures and assesses results to inform future programming recommendations.

Aid provided through other programs was used in a manner consistent with objectives, but some short-term project objectives were not met

1.62 In addition to humanitarian assistance, Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada may use other programs to provide assistance during crises. These include the Global Peace and Security Fund, the Canada Fund for Local Initiatives, and bilateral development programs. These programs are used because they can support projects with a broader range of goals and that involve different partners than the international humanitarian assistance program. For example, the Global Peace and Security Fund may support projects aiming to increase security in crisis-affected states. We looked at two projects for each of these three types of programs to determine whether the Department could demonstrate that these funds were used in a manner consistent with the objectives described in departmental decision documents and grant agreements.

1.63 We found, similar to the international humanitarian assistance program, that the Department could demonstrate that the funds for most selected projects were used in ways consistent with the objectives for which they were provided. Key tools for providing this assurance were partner project reports and the Department’s own monitoring reports.

1.64 The two Global Peace and Security Fund projects that we examined were in response to the Syria conflict crisis. The projects were to help Jordanian authorities deal with the inflow of persons displaced by the conflict. Both projects experienced delays, but had been completed by the time of our audit.

1.65 The two bilateral development program projects that we examined were also to provide assistance in Jordan to address issues related to persons displaced by the crisis in Syria. Both of these projects experienced delays of more than a year. The grant agreements were signed in March 2013, and at the time of the audit no substantive assistance had yet been delivered. One project was delayed largely due to lengthy negotiations between the partner and other stakeholders. The other project was cancelled but, at the time of our audit, Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada was transferring the funding to another project being carried out by the same partner to address development needs related to the same crisis. Most of the funds contributed had not yet been spent by its partners, and the Department had agreed to their use to achieve longer-term objectives, but the original purpose of the funding had been to support urgent needs for food and livelihood assistance.

1.66 The Department assessed the two bilateral development projects as low risk when it decided to undertake them. However, the delays experienced by the projects show that actual risks were higher than assessed. During 2013 and 2014, the Government of Canada committed to providing more than $200 million over the next few years through its bilateral development programs to respond to the ongoing Syria crisis. It is therefore important that the Department reflect on its experiences with these two projects in determining the Department’s approach to risks and mitigation strategies for future expenditures to help ensure short-term objectives are achievable.

1.67 Recommendation. Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada should re-examine its risk assessment and mitigation strategy for development projects in the Syria crisis intended to meet urgent needs.

Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada’s response. Agreed. The Department notes that both projects reviewed by the Auditor General, which have led to this recommendation, are now fully operational. Potential project implementation delays represent key considerations when planning and making decisions related to investments in development assistance. The Department will provide greater weight to the aspect of timeliness in assessing and establishing risk ranking for projects.

Federal spending exceeded government commitments to match funds

1.68 Following the onset of several humanitarian crises, Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada announced a matching fund initiative. By announcing that it will match donations by the public to Canadian charities dollar for dollar, the government aims to show generosity and responsiveness to humanitarian crises, encourage fundraising efforts by Canadian charities, and encourage donations by the Canadian public. In 2012, the Department established a formal framework including a set of minimum conditions for launching a matching fund.

1.69 Matching funds have been used for nine humanitarian crises since 2004. Three of these were crises within the period covered by our audit: the East Africa drought crisis in 2011, the Sahel food and nutrition crisis in 2012, and Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines in 2013.

1.70 We therefore examined whether the government funding for these three crises matched the reported donations of the Canadian public. After the government announces a matching fund, Canadian charities report to Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada the amount of donations received from individuals for the crisis. To meet the matching fund commitment, the Department must fund assistance to the crisis up to the amount of reported donations. To fulfill this commitment, the Department uses its regular programming approach to fund the organizations it considers best able to deliver assistance. It does not necessarily give government matching funds to the charitable organizations that raised the funds from the public.

1.71 For the East African drought crisis and the Sahel food and nutrition crisis, the Department provided us with listings showing the aid projects it financed that it considered as matching donations reported by Canadian charities. We found that these projects were for the delivery of humanitarian assistance to the crises on which the Department promised to spend the matching funds. Therefore, the Department honoured its matching fund commitments for the East Africa drought and Sahel food and nutrition crises. Moreover, the federal government spent more on these crises than the amount it was required to match (Exhibit 1.4).

Exhibit 1.4—The federal government has exceeded its commitment to match public donations to Canadian charities

| East Africa drought (2011) | Sahel food and nutrition crisis (2012) | Typhoon Haiyan (2013) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public donations | $70.4 million | $6.9 million | $85.6 million |

| Federal government expenditures | $161.1 million | $65.4 million | $62.9 million (actual and approved expenditures as of 31 March 2014; further spending is planned) |

Source: Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada

1.72 For the Typhoon Haiyan matching fund, Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada’s spending by the end of our fieldwork was not yet enough to match donations reported by Canadian charities. However, planning was underway for additional spending (Exhibit 1.4).

1.73 Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada determines the amount that it is required to match by compiling the amounts reported on declaration forms submitted by registered Canadian charities. Completed forms provide summary totals and do not contain a list of individuals and amounts donated. While the Department does review the forms, it relies mainly on the charitable organizations to ensure the accuracy of the information provided. Even if the information submitted is not accurate, the Department does not view this as a risk because it typically contributes in excess of the matching fund commitment.

Canadian Armed Forces capabilities deployed to the Philippines played a useful role, but several factors limited the amount of assistance delivered

1.74 The Canadian Armed Forces maintains the Disaster Assistance Response Team (DART) for international humanitarian operations. Within the period covered by the audit, there was only one significant deployment of the Canadian Armed Forces for humanitarian purposes, which was in response to Typhoon Haiyan, which struck the Philippines on 8 November 2013.

1.75 The Canadian Armed Forces deployed nearly 320 personnel to the island of Panay in the Philippines. These included

- an air task force to provide transport on the island to mobile medical teams, food supplies, and other items using three Griffon helicopters and one Challenger transport aircraft;

- an engineering squadron—including field engineers, heavy equipment operators, and a spectrum of tradespeople—to purify water, clear routes and debris, and repair infrastructure;

- a medical platoon with four mobile medical teams to provide health services to remote and isolated areas; and

- supporting command, security, liaison, logistics, and communications personnel.

1.76 These capabilities were deployed based on the recommendations of an assessment team sent to the Philippines by Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada. The team, consisting of personnel from both the Department and the Canadian Armed Forces, met with major actors involved in the response including Philippines government officials. The assessment team reported that while domestic capacity to respond was strong, there were significant humanitarian needs on the island of Panay, particularly in terms of access to water, sanitation, shelter, food, and medicine, and concluded that the Canadian Armed Forces could make a useful contribution to support further relief efforts.

Humanitarian gap—The difference between needs occurring during a humanitarian crisis and the ability of national or international humanitarian resources to fill them.

1.77 According to Canadian Armed Forces directives, any involvement in humanitarian operations is intended to be short term to address a humanitarian gap until local authorities or other international organizations can take over. Timely deployment is therefore critical to achieving National Defence’s objectives for humanitarian operations. We therefore looked at whether the Canadian Armed Forces deployed to the Philippines quickly enough that its deployment filled a humanitarian gap. We also examined operational reports to determine whether National Defence could demonstrate that Canadian Armed Forces capabilities delivered the expected assistance.

1.78 The Canadian Armed Forces commanded the DART from a headquarters in a coordination centre on Panay Island that was collocated with Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada, local authorities, the United Nation’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, United Nations humanitarian organizations, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). This collocation enabled the Canadian Armed Forces to coordinate and share information with other organizations participating in relief efforts. We found that the Canadian Armed Forces capabilities did help fill gaps. For example, the mission reported that the helicopters provided urgent assistance to remote communities, including food supplies on behalf of the World Food Programme. For the road clearance and water production capabilities, reports indicate that the Canadian Armed Forces made a useful contribution in locations where they operated, but by the time they came into operation, the gap between humanitarian need and what civil authorities and humanitarian agencies could provide was diminished.

1.79 Road clearance. Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada concluded that heavy equipment was necessary to clear roads permitting access by humanitarian aid workers. However, reports indicate that, on the island of Panay, major road networks were accessible before the DART started clearance due to a campaign by the local authorities. Mission reports indicated that DART cleared 131 kilometres of roads during the deployment, of which 86 percent was cleared in the first seven days.

1.80 Water production. The Canadian Armed Forces deployed three reverse osmosis water purifiers in the Philippines. We found that, at the time the Canadian Armed Forces, local authorities, and NGOs began distributing water produced by the DART, there was no longer a critical need for water in areas where, for example, municipal water plants were back in operation. For this reason, the purifiers were located where DART personnel, local authorities, and humanitarian organizations determined there remained a need for water purification. The first was operational on November 23 and the last began production on December 3. The time required to bring the water purification into operation was the result of transporting the purifiers one at a time from Canada, needing to find and lease suitable land, and technical problems.

1.81 National Defence indicated that as a planning figure, each reverse osmosis unit could produce an average of 20,000 litres of water per day depending on the quality of the source water to be treated and the level of demand from the local population. However, mission reports showed that the units produced only 65 percent of this amount and distributed only 73 percent of what was produced, for an average of 9,400 litres distributed per day. National Defence told us that this was mainly due to limitations in the water distribution capabilities of the local authorities and NGOs. For example, local authorities did not pick up water from the Canadian Armed Forces on several days. Mission reports also showed that the Canadian Armed Forces experienced water production issues such as difficulty in ensuring acceptable water quality due to limited experience of the operators and insufficient chemicals, testing equipment, and other supplies. As well, there were failures of water pumps and water was distributed from one unit for only four days because it was damaged by flooding.

1.82 Recommendation. National Defence should examine how to improve the use, reliability, and operations of Canadian Armed Forces water capabilities used in humanitarian operations.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. National Defence, through the Assistant Deputy Minister (Policy), the Strategic Joint Staff, and the Canadian Joint Operations Command, routinely conducts reviews of the Canadian Armed Forces’ contingency plans for humanitarian disasters. National Defence will work closely with our Government of Canada partners to improve both the assessment of the localized need for potable water and the coordination of water distribution for future humanitarian operations.

As part of the internal Canadian Armed Forces “lessons learned” process, an Engineer Operations Planning Group was convened in the spring of 2014 to specifically discuss the operational and technical Reverse Osmosis Water Purification Unit (ROWPU) issues encountered in the Philippines. This discussion led to the production of a Canadian Armed Forces Standard Operating Procedure for ROWPU operations for inclusion in all ROWPU training.

Conclusion

1.83 Overall, we concluded that Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada provided humanitarian assistance at the onset of our selected crises using a needs-based approach through appropriate partners. However, due to insufficient documentation, it was not always clear how the Department determined the amount of humanitarian assistance to provide. As well, immediate emergency response mechanisms funded in advance of need provided timely funding, but several of the international humanitarian assistance program projects in our sample took significantly longer to fund than the others. Longer response times increase the risk that assistance to affected populations will be delayed, but the Department does not measure the overall timeliness of its own processes. Doing so would help the Department identify opportunities to improve its response times and to demonstrate that it responds in a timely manner.

1.84 We also concluded that Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada could demonstrate that for almost all selected international humanitarian assistance program projects, the assistance provided at the onset of selected crises was used by its partners in a manner consistent with the objectives laid out in its decision documents and grant agreements. There were delays with some projects funded through other programs that resulted in short-term project objectives not being met. We identified that there were opportunities to improve the Department’s practices for assessing results and managing risk.

1.85 We concluded that National Defence’s humanitarian operation as part of the Government of Canada’s response to Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines in 2013 was undertaken in a manner consistent with the Canadian Armed Forces’ stated objective for humanitarian operations: to help fill a gap in assistance until the affected country or aid organizations can provide assistance. While the Canadian Armed Forces made a useful contribution, by the time some capabilities came into full operation, the humanitarian gap that they had intended to address had diminished. As well, the Canadian Armed Forces had difficulties with water production and there were weaknesses with water distribution that limited the assistance delivered.

About the Audit

The Office of the Auditor General’s responsibility was to conduct an independent examination of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada’s and National Defence’s responses to the onset of international humanitarian crises to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs.

All of the audit work in this chapter was conducted in accordance with the standards for assurance engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance. While the Office adopts these standards as the minimum requirement for our audits, we also draw upon the standards and practices of other disciplines.

As part of our regular audit process, we obtained management’s confirmation that the findings reported in this chapter are factually based.

Objectives

The objectives of the audit were to determine

- whether Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada provided humanitarian assistance upon the onset of humanitarian crises through appropriate partners using a needs-based approach in a timely manner; and

- whether Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada and National Defence could demonstrate that the assistance they provided upon the onset of humanitarian crises abroad was used in a manner consistent with the objectives of the projects and missions supported.

Scope and approach

The audit examined assistance provided by Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada and National Defence in response to the onset of humanitarian crises abroad.

The systems and practices for providing assistance were examined mainly through a targeted sample of eight crises for which the Government of Canada provided assistance:

- East Africa drought (July 2011)

- Central American flooding (October 2011)

- Sahel food and nutrition crisis (February 2012)

- Syria conflict (March 2012)

- Pakistan floods (September 2012)

- Hurricane Sandy—Caribbean (October 2012)

- Guatemala earthquake (November 2012)

- Philippines Typhoon Haiyan (November 2013)

Our audit work on the selected crises included examining a targeted selection of funding to 42 aid projects and 1 Canadian military humanitarian operation. The parameters used to select the crises and projects included

- crises occurring in developing countries between April 2011 to December 2013;

- a mix of small and large humanitarian crises and projects;

- a mix of types of crises;

- a range of different partners;

- crises where Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada used matching funds; and

- crises that have included significant deployment of the Canadian Armed Forces.

We also looked at lists of project proposals that were rejected by Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada.

The audit examined documentation that departments either prepared or received from their partners. We also met with officials at National Defence and Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada. As well, we interviewed officials at several humanitarian organizations including Canadian non-governmental organizations, International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, International Committee of the Red Cross, World Food Programme, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, World Health Organization, International Organization for Migration, and the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. This is an audit of the Canadian federal government; we did not audit the records of non-governmental partners.

The following federal government activities were excluded from this audit:

- use of core funding provided to multilateral institutions that may be used in responding to crises;

- longer-term rehabilitation and reconstruction assistance;

- longer-term ongoing responses to prolonged complex crises such as Canadian funding of assessed contributions for United Nations peace operations; participation of Canadian military and police personnel on international peace operations; activities of Citizenship and Immigration Canada to find durable solutions for refugees displaced by crises; and longer-term stabilization, security, and development programming;

- emergency management, including the provision of support to Canadian missions during crises and the provision of emergency consular services to Canadians abroad;

- disaster risk reduction programming; and

- military preparedness for combat operations.

Criteria

To determine whether Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada provided humanitarian assistance upon the onset of humanitarian crises through appropriate partners, using a needs-based approach in a timely manner, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada has processes in place to select partners possessing demonstrated capacity to meet the humanitarian needs in a given context. |

|

|

Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada allocates humanitarian assistance funding to crises in a transparent manner, based primarily on the needs of the affected populations. |

|

|

Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada determines its response to the onset of humanitarian crises and provides funding to its humanitarian partners in a timely manner. |

|

To determine whether Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada and National Defence could demonstrate that the assistance they provided upon the onset of humanitarian crises abroad was used in a manner consistent with the objectives of the projects and missions supported, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada can demonstrate that assistance provided upon the onset of humanitarian crises achieved results consistent with its objectives. |

|

|

National Defence can demonstrate that resources used in providing assistance to the onset of humanitarian crises achieved results consistent with its objectives. |

|

Management reviewed and accepted the suitability of the criteria used in the audit.

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period between 1 April 2011 and 31 December 2013. Audit work for this chapter was completed on 5 September 2014.

Audit team

Assistant Auditor General: Wendy Loschiuk

Principal: Nicholas Swales

Director: Daniel Thompson

Wagdi Abdelghaffar

Jared Albu

Chantal Descarries

Jan Jones

Mary Lamberti

Josée Maltais

Elisa Metza

Nasser Nasser

Alisa Niakhai

For information, please contact Communications at 613-995-3708 or 1-888-761-5953 (toll-free).

Hearing impaired only TTY: 613-954-8042

Appendix—List of recommendations

The following is a list of recommendations found in Chapter 1. The number in front of the recommendation indicates the paragraph where it appears in the chapter. The numbers in parentheses indicate the paragraphs where the topic is discussed.

Basing humanitarian assistance on need

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

1.31 Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada should document how the dollar amounts of its humanitarian funding allocations are determined, including key calculations and rationale. (1.27–1.30) |

Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada’s response. Agreed. Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada strives to allocate its humanitarian funding in line with the Principles and Good Practice of Humanitarian Donorship. The Department will work to better document the rationale behind the dollar amounts proposed for humanitarian funding recommendations. |

Providing timely humanitarian assistance

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

1.48 Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada should monitor and assess its timeliness in responding to the onset of crises to identify opportunities for improving its response time. (1.40–1.47) |

Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada’s response. Agreed. Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada agrees that timely funding of humanitarian operations is critical to saving lives and alleviating human suffering, and will continue to identify opportunities for improving its response time. |

Demonstrating consistency with objectives

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

1.61 Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada should assess the results of the humanitarian assistance projects it funds in a manner that is useful for managing operations. (1.51–1.60) |

Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada’s response. Agreed. All of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada’s humanitarian partners provide reporting on an annual basis, which includes results achieved and lessons learned. Assessing those results is an integral part of the program management cycle. The Department will review its current approach to assessing results. Based on that review, it will adopt measures to ensure that it better captures and assesses results to inform future programming recommendations. |

|

1.67 Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada should re-examine its risk assessment and mitigation strategy for development projects in the Syria crisis intended to meet urgent needs. (1.62–1.66) |

Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada’s response. Agreed. The Department notes that both projects reviewed by the Auditor General, which have led to this recommendation, are now fully operational. Potential project implementation delays represent key considerations when planning and making decisions related to investments in development assistance. The Department will provide greater weight to the aspect of timeliness in assessing and establishing risk ranking for projects. |

|

1.82 National Defence should examine how to improve the use, reliability, and operations of Canadian Armed Forces water capabilities used in humanitarian operations. (1.74–1.81) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. National Defence, through the Assistant Deputy Minister (Policy), the Strategic Joint Staff, and the Canadian Joint Operations Command, routinely conducts reviews of the Canadian Armed Forces’ contingency plans for humanitarian disasters. National Defence will work closely with our Government of Canada partners to improve both the assessment of the localized need for potable water and the coordination of water distribution for future humanitarian operations. As part of the internal Canadian Armed Forces “lessons learned” process, an Engineer Operations Planning Group was convened in the spring of 2014 to specifically discuss the operational and technical Reverse Osmosis Water Purification Unit (ROWPU) issues encountered in the Philippines. This discussion led to the production of a Canadian Armed Forces Standard Operating Procedure for ROWPU operations for inclusion in all ROWPU training. |

PDF Versions

To access the Portable Document Format (PDF) version you must have a PDF reader installed. If you do not already have such a reader, there are numerous PDF readers available for free download or for purchase on the Internet: