2016 Fall Reports of the Auditor General of Canada Report 5—Canadian Armed Forces Recruitment and Retention—National Defence

2016 Fall Reports of the Auditor General of CanadaReport 5—Canadian Armed Forces Recruitment and Retention—National Defence

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

- Reaching targets

- The Regular Force did not meet its target of 68,000 members

- The representation of women did not increase

- Recruiting targets were based on the Canadian Armed Forces’ capacity to recruit and train rather than on the Regular Force’s needs

- Overall recruiting targets were achieved, but several occupations were understaffed

- Getting and developing the right people

- Keeping the right people

- Reaching targets

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- List of Recommendations

- Exhibits:

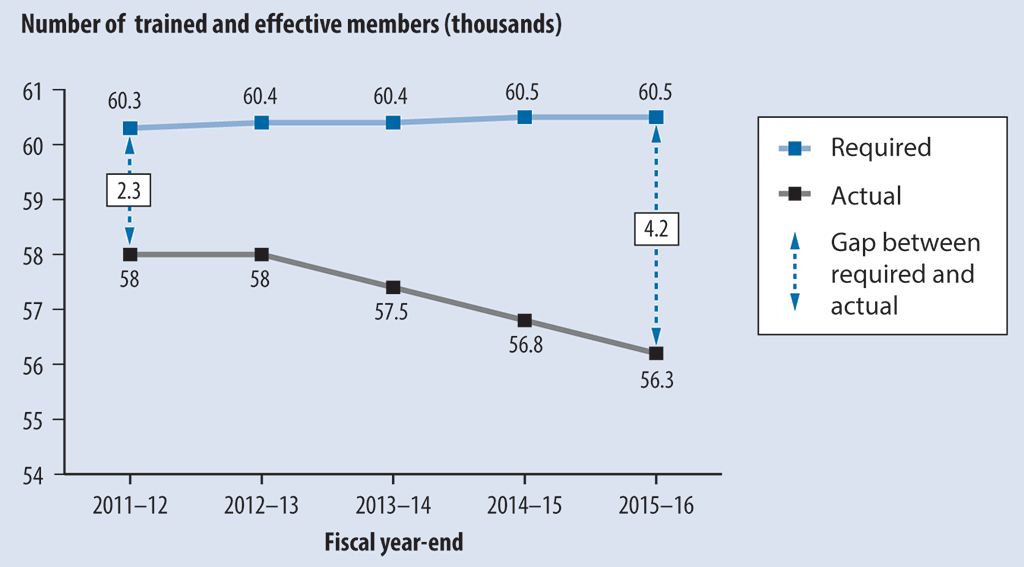

- 5.1—The gap between the required and actual numbers of trained and effective Regular Force members increased from about 2,300 at the end of the 2011–12 fiscal year to about 4,200 at the end of the 2015–16 fiscal year

- 5.2—Enrolments did not meet the numbers needed for some occupations

- 5.3—Non-commissioned members in some occupations took considerable time to become fully functional, partly because of the waiting times during training

Introduction

Background

5.1 National Defence is composed of the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces. The Department is responsible for coordinating with other federal and provincial departments, and for policy and general administration. The Canadian Armed Forces is responsible for commanding, controlling, and administering the Canadian Armed Forces as it carries out the missions identified in the 2008 Canada First Defence Strategy.

5.2 The Canadian Armed Forces includes the Regular Force and the Reserve Force. To carry out its missions effectively, the Canadian Armed Forces needs an appropriate number of trained personnel with the requisite skills for the Canadian Army, the Royal Canadian Air Force, and the Royal Canadian Navy, known as the three environments. To maintain its capability and readiness, the Canadian Armed Forces must select and develop thousands of recruits each year and retain a significant number of its members.

5.3 Chief of the Defence Staff. Under the Chief of the Defence Staff, the three environments of the military are responsible for managing the Canadian Armed Forces’ operations and carrying out missions.

5.4 Military Personnel Command. The Military Personnel Command has functional authority on personnel-related matters and must ensure that sufficient trained personnel are available to fulfill the Canadian Armed Forces’ requirements. The Military Personnel Command recently reorganized its recruitment activities and became responsible for all aspects of the recruiting program—including defining its requirements and attracting, recruiting, selecting, and enrolling personnel. It is also responsible for individual training and education and for retaining military personnel.

5.5 The Office of the Auditor General of Canada conducted audits on the Canadian Armed Forces recruitment and retention in 2002 and 2006:

- 2002 April Report of the Auditor General of Canada, Chapter 5—National Defence—Recruitment and Retention of Military Personnel; and

- 2006 May Status Report of the Auditor General of Canada, Chapter 2—National Defence—Military Recruiting and Retention.

5.6 Previous findings indicated ongoing, systemic recruiting challenges for the Regular Force in its efforts to counter higher rates of attrition and fill certain chronically understaffed occupations. Recruiting targets did not match the needs of the Royal Canadian Navy or the Royal Canadian Air Force, and there was no comprehensive plan to attract more applicants, particularly women, Aboriginal peoples, and visible minorities. The audits also identified issues with training recruiting staff, the quality of the tools used to assess applicants, and applicant processing, which caused many potential candidates to withdraw their applications.

Focus of the audit

5.7 This audit focused on whether the Canadian Armed Forces implemented appropriate systems and practices to recruit, train, and retain the Regular Force members needed to achieve its objectives.

5.8 This audit is important because the Canadian Armed Forces must have an adequate number of members trained and available for duty to meet its domestic and international obligations.

5.9 We did not examine recruitment and retention in the Reserve Force; we completed an audit on this subject in 2016 (2016 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Report 5—Canadian Army Reserve—National Defence). We also did not examine the process for Reserve Force members to transfer to the Regular Force.

5.10 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Reaching targets

Overall message

5.11 Overall, we found that the total number of Regular Force members had decreased, and that there had been a growing gap between the number of members needed and those who were fully trained. In our opinion, it is unlikely that the Regular Force will be able to reach the desired number of members by the 2018–19 fiscal year as planned. We also found that although the Canadian Armed Forces had established a goal of 25 percent for the representation of women, it did not set specific targets by occupation, nor did it have a strategy to achieve this goal.

5.12 We found that although the Regular Force had mechanisms in place to define its recruiting needs, those needs were not reflected in recruitment plans and targets. Instead, recruitment targets were based on National Defence’s capacity to process applications and enrol and train new members. Furthermore, we found that the total recruitment targets had been met by enrolling more members than had been set as targets in some occupations, leaving other occupations significantly below the required number of personnel.

5.13 This is important because the Canadian Armed Forces needs a sufficient number of trained members in the right balance of occupations to maintain its military capability and accomplish the missions set out in the Canada First Defence Strategy.

5.14 According to National Defence, the maximum number of members in the Regular Force was established at 68,000 (plus or minus 500). To accomplish its mandate, the Regular Force needs 60,500 members who are fully trained and effective in their roles. The difference between these two numbers includes members who are on training, ill, or injured.

5.15 The Canadian Armed Forces must perform a wide variety of duties. These are organized into occupations. Approximately 85 of the Regular Force’s 95 occupations are staffed through external recruiting—that is, from the general public. The remaining occupations are staffed by existing Regular Force members or transfers from the Reserve Force. For each occupation, the Canadian Armed Forces needs a sufficient number of members who are healthy, available, and have the required training and competencies for their occupations. The Canadian Armed Forces considers that occupations are “stressed” when they are staffed at less than 90 percent of their required number of trained and effective members.

5.16 Under the Employment Equity Act, the Canadian Armed Forces must identify and eliminate employment barriers and take measures to ensure that women and other designated groups are appropriately represented, taking into account the need for operational effectiveness.

The Regular Force did not meet its target of 68,000 members

5.17 We found that the Regular Force decreased in size since the 2011–12 fiscal year. In our opinion, it is unlikely that it will be able to recruit, train, or retain sufficient personnel to meet its target of 68,000 members by the 2018–19 fiscal year. We also found that the number of Regular Force members who were trained and effective was lower than its required number, and the gap between its required number and the actual number had increased.

5.18 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

5.19 This finding matters because inadequate numbers of trained personnel can affect National Defence’s ability to meet Canada’s international and domestic requirements.

5.20 We made no recommendations in this area of examination.

5.21 What we examined. We analyzed the number of Regular Force members through summary reports produced since the 2011–12 fiscal year.

5.22 Total number of members. We found that the Regular Force was below its target of 68,000 members, and that the number of members had decreased over the past four years. The Regular Force’s numbers shrank from about 67,700 members at the end of the 2011–12 fiscal year to about 66,400 at the end of the 2015–16 fiscal year.

5.23 The actual numbers of members hired for the Regular Force in the 2014–15 and 2015–16 fiscal years (about 4,200 and 5,300, respectively) were below what National Defence had said it needed to reach 68,000 members. The Regular Force planned to reach its target of 68,000 members by the 2018–19 fiscal year. To do so, National Defence estimated that it would need to hire 5,200 members in the 2016–17 fiscal year and 5,800 in each of the following two fiscal years. In our opinion, it is unlikely that the Regular Force will reach its target of 68,000 members by the 2018–19 fiscal year without making significant changes to increase its annual recruits.

5.24 Trained and effective members. We also found that the Regular Force was under its target of 60,500 members who were fully trained and effective in their occupations. This number does not include members who were not performing in their occupations because they were on training, ill, or injured. We observed that by the end of the 2015–16 fiscal year, the gap between the required and actual numbers of fully trained and effective members for the Regular Force had increased to about 4,200 members from about 2,300 at the end of the 2011–12 fiscal year (Exhibit 5.1).

Exhibit 5.1—The gap between the required and actual numbers of trained and effective Regular Force members increased from about 2,300 at the end of the 2011–12 fiscal year to about 4,200 at the end of the 2015–16 fiscal year

Source: Based on data from National Defence (unaudited)—numbers have been rounded

Exhibit 5.1—text version

This is a graphic comparing the required numbers of trained and effective Regular Force members to the actual numbers, and showing the gap between these numbers.

At the end of the 2011–12 fiscal year, the gap was approximately 2,300. From the end of the 2012–13 fiscal year to the end of the 2015–16 fiscal year, the gap increased to almost 4,200.

| Fiscal year-end | Required | Actual | Gap between required and actual |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011–12 | 60,314 | 58,035 | -2,279 |

| 2012–13 | 60,443 | 57,980 | -2,463 |

| 2013–14 | 60,418 | 57,449 | -2,969 |

| 2014–15 | 60,462 | 56,779 | -3,683 |

| 2015–16 | 60,449 | 56,255 | -4,194 |

The representation of women did not increase

5.25 We found that although the Canadian Armed Forces had established a goal for the representation of women among its ranks, it set this overall goal with no specific targets by occupation. We also found that despite the fact that achieving this goal depends heavily on increased recruiting, the Canadian Armed Forces had not implemented any special employment equity measures. The goal was 25 percent during the audit period; meanwhile, women represented 14 percent of the Regular Force.

5.26 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

5.27 This finding matters because it is difficult to attract, select, train, and retain more women in the Canadian Armed Forces without implementing special employment equity measures.

5.28 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 5.34.

5.29 What we examined. We reviewed the Canadian Armed Forces’ employment equity plans for 2010–15 and 2015–20 and available documentation on its goal for the representation of women. We also examined documentation on the actual representation of women and measures that had been put in place to achieve its goal in this area. We also interviewed Canadian Armed Forces officials.

5.30 The goal. In its 2011 Audit Report on Employment Equity in the Canadian Armed Forces, the Canadian Human Rights Commission invited the Canadian Armed Forces to aim for 25 percent as its goal for the representation of women. In 2016, the Chief of the Defence Staff announced that the Canadian Armed Forces would increase the percentage of women by 1 percent every year until this overall goal was met.

5.31 The Canadian Armed Forces must comply with the Employment Equity Act, as well as with regulations that adapt the Act for the Canadian Armed Forces in consideration of the military nature of its operations. These regulations require establishing short- and long-term goals for increasing the representation of women in each occupational group, based on their availability in the Canadian workforce.

5.32 Representation of women. In February 2016, the Canadian Armed Forces indicated that women represented about 14 percent of its Regular Force, or about 9,500 members. In the 2014–15 fiscal year, statistics indicated that about 50 percent of women in the Canadian Armed Forces were concentrated in six occupations: resource management support clerks, supply technicians, logistics officers, medical technicians, nursing officers, and cooks. During the 2014–15 and 2015–16 fiscal years, 14 percent of new recruits were women.

5.33 Plans and measures. We found that the Canadian Armed Forces had established the overall goal of increasing the percentage of women by 1 percent every year but had not set specific targets for each occupation. The expectation was that the Canadian Forces Recruiting Group would recruit more women. While some efforts were made to attract women, no special recruiting program was developed for that purpose. In our view, without a more concerted effort to attract women in occupations where they are under-represented, the Canadian Armed Forces will remain significantly short of its 25 percent employment equity goal.

5.34 Recommendation. The Canadian Armed Forces should establish appropriate representation goals for women for each occupation. It should also develop and implement measures to achieve them.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. A series of initiatives, however, has been developed in order to meet objectives set by the Chief of the Defence Staff.

The following initiatives have been or will be initiated before the end of 2016: A cultural shift is under way that positively affects the Canadian Armed Forces’ recruiting methods. The Canadian Armed Forces is giving priority processing and enrolment to women. It has recently re-energized its attraction and marketing strategy and has assigned women their own line of advertising priority. Previously serving female members who released from the Canadian Armed Forces in the last five years will be offered a return to the Canadian Armed Forces for full-time or part-time employment. The Canadian Armed Forces is prioritizing women applicants at its two Canadian military colleges as well.

The following initiatives will be under way in 2017: The Canadian Armed Forces will stand up a full-time team called the Recruiting and Diversity Task Force, which will be dedicated to developing, planning, and executing activities aimed at increasing diversity group levels in the Canadian Armed Forces. An Advisory Board of prominent Canadians will also be created to advise the Canadian Armed Forces on recruiting. The Task Force and the Advisory Board will work together to influence Canadians and other stakeholders to make the Canadian Armed Forces an employer of choice. A women’s employment opportunity program will be implemented to inform and educate women about the benefits of a Canadian Armed Forces career. A Canadian Armed Forces retention strategy will be implemented to tailor policies and programs to increase retention.

Recruiting targets were based on the Canadian Armed Forces’ capacity to recruit and train rather than on the Regular Force’s needs

5.35 We found that the Regular Force had a well-defined process to identify the number of recruits it needed in each occupation. However, the recruiting targets that resulted were significantly lower than the numbers needed. These targets reflected the recruiting and training capacity rather than the Regular Force’s actual needs.

5.36 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

5.37 This finding matters because the recruiting group needs accurate information on the Regular Force’s true needs in order to plan recruitment. It can take several months to advertise positions and to reach potential applicants. Otherwise, the Regular Force risks turning away qualified applicants.

5.38 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 5.44.

5.39 What we examined. We examined the processes the Regular Force used to identify recruiting needs and translate them into recruiting targets and plans for the 2014–15 and 2015–16 fiscal years. We interviewed Canadian Armed Forces officials, analyzed planning documents, and observed some of the annual occupation reviews.

5.40 Recruiting needs. For both fiscal years, the Regular Force conducted occupation reviews to monitor each occupation and assess whether it had a sufficient number of trained and effective members to meet operational requirements. A long-range planning model provided data on factors influencing each occupation, including yearly enrolment, attrition trends, and the training system’s pace and capacity.

5.41 We found that the annual occupation reviews allowed the Regular Force to define the number of new members it needed for each occupation. The reviews also provided a forum to discuss internal and external factors that influenced members’ availability, training, and attrition rates. Based on those reviews, the Regular Force identified its five-year recruiting needs. The Military Personnel Command used these numbers to create a recruiting plan for the following year, specifying the number of recruits to be enrolled in each occupation. These targets were then given to the recruiting group.

5.42 Recruiting targets. We found that for the 2014–15 and 2015–16 fiscal years, the Military Personnel Command’s recruiting targets were significantly lower than the levels that had been recommended by the Regular Force through its occupation reviews. In the 2015–16 fiscal year, the Regular Force had identified the need for 5,752 new recruits (in addition to members who would be transferring from the Reserve Force), yet the target in the recruiting plan was adjusted to 4,200. Similarly, for the 2014–15 fiscal year, 4,567 members were needed, but the target was adjusted to 3,800.

5.43 We found that the gap between the needs identified by the Regular Force and the recruiting targets of the Military Personnel Command reflected the processing capacities of the recruiting group and the school that provides basic military training. Increasing the capacities of the recruiting group and of the school was considered but determined to be too costly a fix for a problem that, in the Canadian Armed Forces’ opinion, would be resolved by the 2018–19 fiscal year. However, in our opinion, given our findings related to actual enrolments compared with targets, it is unlikely that the Regular Force will achieve its target of 68,000 members in this time frame.

5.44 Recommendation. The Canadian Armed Forces should review its recruiting and training capacity and align this with its planning process to ensure that the recruiting plan reflects the personnel required in each occupation.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. Several years of reductions to recruiting and training capacity as well as shrinking advertising and marketing budgets contributed to the current levels of institutional capacity. The Canadian Armed Forces is currently identifying the additional resources required to recruit and generate the required personnel for each occupation to reach authorized levels by 2018.

Overall recruiting targets were achieved, but several occupations were understaffed

5.45 We found that although the recruiting group met its adjusted target for the total number of enrollees, it did this while not enrolling the number of people needed for some occupations. We also found that several occupations have been understaffed for many years because of issues with recruiting, training, or retention.

5.46 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

5.47 This finding matters because the Regular Force requires a wide variety of skills and competencies. Having enough staff available and trained in each occupation—not just the right overall number of members—is important for accomplishing its operations.

5.48 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 5.52.

5.49 What we examined. We examined personnel reports on the number of members in each occupation and compared recruiting targets with actual enrolments for each occupation for the 2014–15 and the 2015–16 fiscal years. We also interviewed Canadian Armed Forces officials.

5.50 Overall compared with occupation-specific targets. We found that the recruiting group was able to meet its overall recruiting target of the Military Personnel Command—which was smaller than the needs identified by the Regular Force—in both the 2014–15 and the 2015–16 fiscal years. However, the recruiting group achieved this by enrolling more than the adjusted target in certain occupations—for example, pilots, vehicle technicians, firefighters, boatswains, air combat systems officers, resource management support clerks, and stewards—and enrolling less than the adjusted target in others (Exhibit 5.2). Occupations that were consistently under-enrolled and difficult to recruit for included medical officers, physiotherapy officers, signals officers, naval combat systems engineering officers, social work officers, and electronic-optronic technicians.

Exhibit 5.2—Enrolments did not meet the numbers needed for some occupations

| Fiscal year | Identified need | Adjusted targetNote 1 | Enrolments | Number of occupations with enrolments 10% below adjusted targetNote 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Numbers do not include transfers from the Reserve Force. |

|||||||

| 2014–15 | 4,567 | 3,800 | 3,908 | 27 of 84 | |||

| 2015–16 | 5,752 | 4,200 | 4,297 | 27 of 85 | |||

Source: Adapted from National Defence data (unaudited)

5.51 Stressed occupations. Occupations are considered stressed when positions are staffed with less than 90 percent of the target for trained and effective members. Being understaffed places additional strain on members in those occupations. It can also affect the Canadian Armed Forces’ capacity to perform certain duties. As of 31 March 2016, there were 21 stressed occupations, and several of them had been stressed for a number of years. Each of these occupations had different challenges: some were consistently under-enrolled, while others had high attrition rates or delays attributed to training.

5.52 Recommendation. The Canadian Armed Forces should develop and implement a three- to five-year target with an action plan for each occupation to meet recruiting needs, track progress, and take corrective action where necessary.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Canadian Armed Forces currently uses a five-year long-range planning model that factors in attrition and growth. That model is then analyzed in detail to produce a Strategic Intake Plan for each occupation during the Annual Military Occupational Requirements process. This plan is used to determine the recruiting requirements of each occupation. However, the Canadian Armed Forces acknowledges that the planning process must become more agile to adjust to changing requirements throughout the process and take corrective action when required. The Canadian Armed Forces is currently undertaking measures to improve this planning process.

Getting and developing the right people

Overall message

5.53 Overall, we found that the Regular Force was unable to attract a sufficient number of qualified applicants for some occupations. Recruiters did not always have the support needed to provide the necessary information to applicants. We also found that certain practices in the recruitment process prevented qualified candidates from being enrolled. Once recruits were enrolled, they had minimal waiting times for basic training, but they had considerable waiting times for some occupational training. In addition, the Regular Force lacked sufficient mechanisms to oversee members’ progress in training programs.

5.54 This is important because the manner in which the process for applicants is carried out and new recruits are trained has a large impact on how long they will stay in the Canadian Armed Forces. It is also more cost-effective to keep applicants and new trainees in the process, rather than to lose them and have to start over with new members.

5.55 Recruitment. Under the authority of the Military Personnel Command, the Canadian Forces Recruiting Group is responsible for attracting, processing, selecting, and enrolling all Regular Force recruits. This group is also responsible for processing Reserve Force recruits and cadet instructors. Since 2008, the recruiting group has been reduced by about 180 positions, and has closed 13 recruiting locations, as a result of budget cuts. In 2015, it operated out of 23 full-time and 3 part-time locations across Canada, with approximately 620 positions.

5.56 The first step in the recruiting process is to reach out to different groups of Canadians to attract prospective applicants by providing them with information intended to raise their interest in joining the Canadian Armed Forces. Attraction activities include advertising and marketing campaigns, national events, diversity events, school and job fair visits, social media campaigns, and the daily actions of recruiters in each recruiting detachment.

5.57 The number of occupations to which the general public is eligible to apply has fluctuated slightly from year to year. In the 2015–16 fiscal year, the public could apply for 85 of the 95 Regular Force occupations. Applicants could apply through direct entry if they had the minimum education required for the occupation, or through the paid education program to complete college, university, or a specialized professional education.

5.58 The Canadian Forces Recruiting Group uses online applications. Centralized initial screening refers applicants’ files to recruiting locations for processing. Selection decisions have also been centralized. Applicants compete nationally, regardless of their region.

5.59 Training. Once enrolled, all recruits must complete basic training, which is delivered by the Canadian Forces Leadership and Recruit School. For non-commissioned members, the course lasts 12 consecutive weeks. The course for officer cadets is two weeks longer, and because many officer cadets are university students, it can be completed over the summer months. Trainees must complete further training to develop qualifications for their respective occupations. The three environments—the Canadian Army, the Royal Canadian Air Force, and the Royal Canadian Navy—have primary responsibility for delivering occupational training. Another group under the authority of the Military Personnel Command provides training for occupations that support all three environments, such as logistics officers.

5.60 Numerous establishments across Canada deliver military training. There are significant variations among training programs for members in different occupations. For some occupations, the occupational training program is provided in one geographic location. For others, the program has many courses at various locations and can take years to complete.

The Regular Force did not do enough to attract qualified applicants for certain occupations

5.61 We found that the Regular Force did not attract a sufficient number of qualified applicants for several occupations. Information needed by applicants about specific occupations and the Regular Force’s requirements was not always easy to obtain, and recruiters lacked the necessary support to provide detailed information on every occupation.

5.62 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

5.63 This finding matters because attraction is the first step in the recruitment process. To be successful, the recruitment process requires a sufficient number of qualified applicants.

5.64 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 5.71.

5.65 What we examined. We examined the processes the Regular Force used to attract applicants by examining planning documents and the recruiting website. We also visited recruiting detachments and interviewed recruiters.

5.66 Information for applicants. We found that in general, the Regular Force attracted sufficient applicants to enrol thousands of new members each year. However, it was not successful in attracting enough qualified applicants for several specific occupations.

5.67 The Canadian Armed Forces’ website is a key source of information for job seekers about the Canadian Armed Forces as an employer, as well as about its various occupations. We found that the website did not provide potential applicants with a tool to identify the occupations they were best suited or qualified for. The information was organized by occupation, but there was no way for job seekers to view job descriptions or educational requirements without clicking through many pages. As well, many occupations lacked civilian-equivalent titles. These issues may make it difficult for applicants who are unfamiliar with the Canadian Armed Forces to find the information they need.

5.68 Support for recruiters. Attraction activities relied heavily on day-to-day interactions between recruiters and the public. Therefore, to make a career in the Canadian Armed Forces attractive—and to be able to offer accurate occupational information—recruiters needed sufficient knowledge of the occupations, including their entry plans. Potential recruits needed to know what to expect in terms of lifestyle, compensation, and training options to make informed decisions about joining the Canadian Armed Forces. Misconceptions about these aspects could lead recruits to leave their positions prematurely.

5.69 We observed that efforts were made to ensure that recruiters represented a variety of different occupations and all three environments of the military—the Canadian Army, the Royal Canadian Air Force, and the Royal Canadian Navy. However, in our view, it was unlikely that each recruiter could have had in-depth knowledge of so many individual occupations. We found that the Canadian Armed Forces offered limited information and resources to support recruiters. We were told that recruiters did not have consistent access to subject matter experts to answer their detailed questions or keep track of changing entry requirements.

5.70 Each year, the Canadian Forces Recruiting Group worked with the three environments to identify several priority occupations for specific attraction activities. We found special focus on attracting recruits for some occupations. For example, four specialist recruiter positions were created to focus specifically on health services occupations. However, special attention was not provided to all stressed occupations (staffed at less than 90 percent of the required number of trained and effective members).

5.71 Recommendation. The Canadian Armed Forces should implement targeted measures to attract enough qualified applicants for all occupations for which it has difficulty attracting applicants.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Department of National Defence is developing a recruiting advertising and marketing campaign to better attract applicants. However, the Canadian Armed Forces acknowledges that more creative and tailored attraction, advertising, and marketing strategies are required to meet its recruiting targets for a number of occupations. Based on the Canadian Armed Forces’ input, the Department will prioritize existing resources in support of this initiative.

The recruiting process did not meet the applicants’ needs

5.72 We found that the recruiting process was lengthy for many applicants, with delays in key areas. In addition, files were closed in some cases while applicants were still interested, and the organization’s timelines for file processing took priority over the applicants’ circumstances. This contributed to qualified candidates leaving the recruitment process.

5.73 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

5.74 This finding matters because recruiting is about people—and people need time to transition to a new job in the Canadian Armed Forces. Both adequate communication and flexibility are important to keep qualified applicants in the process.

5.75 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 5.87.

5.76 What we examined. We examined the steps taken to process applications and enrol Regular Force recruits for the 2014–15 and the 2015–16 fiscal years. We interviewed recruiting staff, analyzed data and documents, and reviewed a sample of applicant files for occupations that did not meet recruiting targets.

5.77 Many steps were required to process recruits. The Canadian Forces Recruiting Group was responsible for managing the overall process and communicating with applicants. Applicants had to apply for specific occupations and pass an aptitude test. Different scores were required, depending on the occupation. Qualified and competitive applicants were invited for interviews and basic medical exams. At this point, applicants also had to complete reference and background checks, security screening, and academic screening. Certain occupations needed additional screening and testing. Once all requirements were met, candidates were placed on a national merit list, and the top candidates were selected. There were specific selection dates for each occupation. Depending on the number of recruits needed, there might have been one or many selection dates offered throughout the year. Selected candidates received offers of employment, which they were expected to accept or reject within two weeks.

5.78 Time required for recruitment. Recruiting can be a lengthy process, with many steps. According to the Canadian Forces Recruiting Group, the average time to enrol a recruit was approximately 200 days in 2015. Some delays may be unavoidable—for example, obtaining security clearances for individuals who need validation from foreign countries can take a long time. Delays may also be due to the time it takes applicants to obtain and provide documents. However, we found that the time needed for other steps in the process—such as assessing educational equivalencies or conducting medical screening—could have been reduced.

5.79 Educational equivalencies were assessed when applicants had previous experience and education related to their chosen occupations. These equivalencies can reduce the amount of training required after enrolment. The Canadian Forces Recruiting Group can approve some of these; according to the Canadian Armed Forces, this takes a few days. However, we found that educational equivalencies that required authorization from the occupation’s authority took two to six months.

5.80 All applicant files must go to the Canadian Armed Forces’ medical group to determine if applicants are medically fit. We were informed that for applicants with no medical issues, this process took two to three months, but their files could continue to be processed during that time. However, for many other applicants who had to provide letters from family doctors or specialists to explain medical conditions, delays were longer, because the applicants needed time to obtain the documentation and the medical group needed to review the file again. We observed that for many files, it took several months for applicants to obtain documents and more than six months for the medical group to complete reviews.

5.81 Closure of applicants’ files. We observed cases in which files were closed while applicants were still interested in pursuing a career in the Canadian Armed Forces—such as when the applicant

- was waiting for medical specialist appointments or waiting to submit medical documents,

- had requested more time to gather references or attend additional screening or testing, or

- had applied for an occupation where all positions had been filled for the current fiscal year.

5.82 Although it was relatively easy to reopen files after closure, this was not done systematically. The recruiting group lacked a mechanism to bring files back to recruiters’ attention—possibly creating the perception that the Canadian Armed Forces did not really want to recruit the applicant.

5.83 Processing of applicants’ files. Regular Force recruitment was set up to process recruits within fixed time frames to meet specific selection dates. In our opinion, the Canadian Forces Recruiting Group was too rigid in scheduling screening appointments and in making offers of employment. The group prioritized the organization’s timelines over the applicants’ circumstances, contributing to qualified applicants leaving the process.

5.84 In an effort to reduce waiting times for training, the recruiting group tried to align its selection decisions with the start dates for occupational training. Applicants could be scheduled for medical exams and interviews only when a selection date for an occupation was approaching. We found some cases in which applicants had waited up to six months for medical exams or interviews. After this step, they could still change the occupation they were interested in. Also, it could take applicants many months to gather medical documents or references—but any significant delays in these processes could result in their missing the selection date and not receiving an offer.

5.85 Selected candidates received offers of employment that included specific enrolment and training start dates. We found cases where applicants had rejected offers because they needed more time to decide or relocate. For rejections based on timing, the Canadian Forces Recruiting Group did not allow for flexibility or date changes; applicants had to wait for the next selection date. By then, suitable applicants could have received and accepted offers from other employers or schools.

5.86 In our opinion, these approaches may have been appropriate for easy-to-recruit occupations, but in other occupations, there were too few qualified applicants to replace the ones who had left. We found cases in which applicants left the process or files were closed early, contributing to the recruiting group missing its recruiting targets.

5.87 Recommendation. The Canadian Armed Forces should review its selection process with a view to improving its efficiency—including better file management methods and increased flexibility in the recruitment process—in order to maintain a sufficient pool of qualified applicants.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Canadian Armed Forces is currently conducting an extensive review of its entire recruiting process for completion in the 2017–18 fiscal year with a goal of significantly reducing time between processing steps and making the entire process more agile and flexible.

Members in some occupations waited a considerable time to complete their training

5.88 We found considerable delays from one training phase to the next for some occupations. We also found that the Regular Force lacked a consistent reporting method for personnel who were in training, including members awaiting training. This impeded its capacity to monitor members’ progression through their training and measure the efficiency and effectiveness of the training.

5.89 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

- time required to train members,

- timing of basic training,

- timing of occupational training, and

- tracking members in training.

5.90 This finding matters because the availability of Regular Force trained personnel depends on each member’s prompt progression through training. The sooner members are fully trained, the more useful they will be during their service. In addition, time spent waiting for training is a significant source of dissatisfaction for members.

5.91 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 5.101.

5.92 What we examined. We examined data on basic military training and analyzed a sample of training files for seven occupations of the Regular Force. Selected occupations included officers (Infantry Officer, Maritime Surface and Sub-surface Officer, and Pilot) and non-commissioned members (Marine Engineer, Avionics Systems Technician, Army Communication and Information Systems Specialist, and Vehicle Technician). For each of these occupations, we analyzed reports on occupational training delivered between April 2014 and March 2016. We reviewed the training history records of 30 members who were at various stages of their training program. We also interviewed Canadian Armed Forces officials.

5.93 Time required to train members. We found that the delivery of training was complex, and it took time for members to become fully trained and functional in their occupations. Each of the three environments was responsible for assigning courses and monitoring their trainees’ progression. They were also required to track trainees who were ready to be trained in their schools and employ them during waiting periods. Training programs often involved many phases, some delivered at various locations. In many occupations, such as for pilots, various courses had to be completed in a mandatory sequence. In others, like vehicle technicians, the course order was flexible.

5.94 Timing of basic training. To avoid training delays, the Canadian Forces Recruiting Group tried to synchronize the enrolment date of new recruits with the beginning of basic military training. Our tests confirmed that the period of time between these two dates was short.

5.95 Timing of occupational training. After successfully completing basic military training, recruits attended additional training programs to obtain the qualifications they needed to function in their respective occupations. Officers required a university degree in addition to training. Officer recruits who had enrolled prior to completing their university degree, either at the Royal Military College of Canada or another university, completed some of their occupational training while they completed their academic studies. We found that their waiting times were relatively short. In contrast, we found that many officers who had completed their university degree prior to enrolment waited many months between courses. Non-commissioned members also took considerable time to become fully functional, partly because of the time spent waiting for training (Exhibit 5.3).

Exhibit 5.3—Non-commissioned members in some occupations took considerable time to become fully functional, partly because of the waiting times during training

| Occupation | Average training duration (including waiting times) | Average waiting times |

|---|---|---|

| Avionics Systems Technician | 25 months | 6 months |

| Vehicle Technician | 20 months | 7 months |

| Army Communication and Information Systems Specialist | 11 months | 5 months |

| Marine Engineer | 9 months | 2 months |

Source: Adapted from National Defence data (unaudited)

5.96 We found that many trainees had to wait for months at various stages of their training before they became functional in their occupations. Delays were attributed to many factors, such as the schools’ training capacities, maximum and minimum course loads, the availability of courses in both official languages, failing a course, and personal circumstances.

5.97 We observed that while waiting between occupational training courses, some trainees were assigned other training, such as security awareness courses or first aid. However, waiting times were identified as a significant source of dissatisfaction that affected the Regular Force’s ability to retain members during training. As noted in a 2015 retention study by National Defence, waiting times between training periods are a source of demoralization and frustration.

5.98 Tracking members in training. We found that the Regular Force lacked a consistent method to document and account for members on training, including members awaiting training. Schools developed their own reporting methods and formats, making it difficult to integrate and analyze data. Consequently, the Regular Force could not always determine how many of its members were awaiting training or for how long.

5.99 For example, because of unreliable data, we could not calculate delays for pilots’ training. Data showed that 78 members were attending a course, but the course had been over for many months. We were told this error was due to the inability of some training units to update data in the main system used to record training activities.

5.100 The lack of a consistent method limited the Regular Force’s capacity to systematically analyze the efficiency and effectiveness of its training delivery. Having this information would help it better understand its training capacity, assess potential responses to training needs, and consider alternative ways of delivering training.

5.101 Recommendation. The Canadian Armed Forces should implement mechanisms for tracking members in occupational training in order to improve the timeliness of training.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Canadian Armed Forces, as identified in this report, has been successful in ensuring minimal delays between enrolment and basic military training. However, the Canadian Armed Forces acknowledges that steps must be taken to better align follow-on occupational training to avoid lengthy delays. Basic Training List management will remain a focal point for our Canadian Armed Forces training authorities, and the implementation of a new Canadian Armed Forces human resource management system (Guardian) will allow for better alignment of training and tracking of Canadian Armed Forces members awaiting training.

Keeping the right people

The Regular Force did not implement its retention plan

Overall message

5.102 Overall, we found that the Regular Force experienced high levels of attrition in some occupations. Although it knew the causes of attrition, the Regular Force had not implemented its most recent overall retention strategy, nor had it developed specific strategies to respond to the challenges of each occupation.

5.103 This finding matters because the military’s operational capability depends on the Canadian Armed Forces’ ability to retain highly specialized, trained, and experienced military personnel on a long-term basis. It is also important because training and developing people is expensive, particularly in certain occupations; it is therefore more cost-effective for National Defence if, once trained, members stay with the Canadian Armed Forces.

5.104 Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses

5.105 The Canadian Armed Forces spends significant resources and time on training and development, so retaining personnel is important. Throughout their careers, members develop specialized expertise through further training and experience, progressing through the ranks to manage and lead military operations.

5.106 The responsibility for retaining military personnel is shared between the Military Personnel Command and the three environments of the military—the Canadian Army, the Royal Canadian Air Force, and the Royal Canadian Navy. The Military Personnel Command develops retention policies and programs, while the three environments are responsible for monitoring attrition and initiating and recommending actions to prevent it. Together, they formed the Canadian Armed Forces Retention Working Group to discuss and implement retention strategies and policies, help develop a retention strategy to enhance operational effectiveness, and ensure that the Canadian Armed Forces is an employer of choice.

5.107 Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 5.115.

5.108 What we examined. We reviewed documentation, including analyses of attrition, retention strategies, mechanisms to monitor and evaluate retention measures, and the retention working group’s records of discussions. We also interviewed Canadian Armed Forces officials. Our examination of retention was not limited to those occupations that were staffed externally.

5.109 Actual attrition. In the 2014–15 and the 2015–16 fiscal years, the Regular Force lost 5,487 and 4,804 members respectively, which represented about 8 percent and 7 percent of the total number of members in the Regular Force in each of the respective years. We found that attrition rates varied significantly among occupations and were particularly high in some. In the 2015–16 fiscal year, 23 occupations had attrition rates higher than 10 percent.

5.110 We found that whereas the total number of members leaving the Regular Force had outpaced the number of enrolments between the 2011–12 and 2014–15 fiscal years, this trend reversed in the 2015–16 fiscal year. We found that the total number of people leaving during the 2011–12 to 2014–15 fiscal years was about 2,400 more than the total of enrolments. Although the total number of people leaving was 500 fewer than the total number of enrolments in the 2015–16 fiscal year, we observed that in 44 occupations, the number of people leaving had still outpaced enrolments, as it had in the 2014–15 fiscal year.

5.111 Many of our observations were similar to issues we reported on in 2006, when we found that the number of members leaving was increasing and getting proportionally higher when compared with the number of recruits overall, particularly in certain occupations.

5.112 Information on attrition factors. We found that the Regular Force conducted retention surveys every two years to evaluate members’ perceptions and carried out studies to better understand the attrition factors of various occupations. National Defence’s research group produced annual reports on Regular Force attrition, which provided a broad overview of attrition information for the past 20 years, along with more detailed occupation information for the past 5 years. However, this information was not used to develop retention plans for specific occupations.

5.113 Retention strategies and measures. We found that the Canadian Armed Forces had neither implemented nor revised its retention strategy for the Regular Force. In 2009, National Defence developed a retention strategy for the Regular Force. It was supported by an action plan that included more than 40 projects to improve the management of various aspects that influence retention, such as personnel awaiting training, geographic instability, and military units’ attrition monitoring. These projects were not specific to any occupation. They were to be implemented gradually from 2009 to 2011. We were informed that action had been taken for some individual projects, but that the strategy had not been fully implemented. In 2014, the Canadian Armed Forces Retention Working Group planned to develop a revised retention strategy, to be completed by June 2018, using the 2009 strategy as its base.

5.114 In 2014, the Canadian Army called for retention tools and more flexible human resource policies to address high attrition in some geographic areas. In May 2015, Canadian Forces Health Services developed an attraction and retention strategy for occupations under its responsibility. However, such initiatives were developed on an ad hoc basis and did not focus on responding to the specific challenges of each occupation.

5.115 Recommendation. The Canadian Armed Forces should develop, implement, monitor, and evaluate measures to optimize retention for each occupation.

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Canadian Armed Forces will develop a Canadian Armed Forces retention strategy in the 2017–18 fiscal year that will ensure that retaining qualified, competent, and motivated members in uniform is a fundamental aspect of how the Canadian Armed Forces manages its people. While the focus will continue to be the overall personnel requirements using the Annual Military Occupational Requirements process and the Strategic Intake Plan, the Canadian Armed Forces will manage occupational health by implementing tailored retention strategies as required.

Conclusion

5.116 We concluded that the Canadian Armed Forces implemented systems and practices to recruit, train, and retain the members it needed, but, as noted in this report, many of these systems and practices did not meet its needs or achieve its objectives.

5.117 Recruiting targets were set below the Regular Force’s needs. For certain occupations, insufficient numbers of applicants were attracted and processed. In addition, the process placed more emphasis on the Canadian Armed Forces’ timelines and capacities than on applicants’ needs, contributing to some prospective employees leaving the process and others being rejected. Once applicants are enrolled as members, lengthy training times can lead to frustration and attrition, so it is important to track new members with the goal of improving timeliness. Although the Regular Force knew the causes of attrition, it had not implemented or revised its most recent retention strategy.

5.118 In order to achieve the required number of trained members across occupations, the Regular Force must examine its methods of attracting and recruiting candidates, and training and retaining members. It must manage all phases of the process for each occupation. It should tailor and implement different approaches for each occupation to address each occupation’s unique challenges.

About the Audit

The Office of the Auditor General’s responsibility was to conduct an independent examination of recruitment and retention in the Canadian Armed Forces, to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs.

All of the audit work in this report was conducted in accordance with the standards for assurance engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance. While the Office adopts these standards as the minimum requirement for our audits, we also draw upon the standards and practices of other disciplines.

As part of our regular audit process, we obtained management’s confirmation that the findings in this report are factually based.

Objective

The objective of the audit was to determine whether the Canadian Armed Forces implemented appropriate systems and practices to recruit, train, and retain the members needed to achieve the Canadian Armed Forces’ objectives.

Scope and approach

The audit scope included National Defence and focused on the Regular Force. We did not examine the Reserve Force, the process for Reserve Force members to transfer to the Regular Force, or advanced occupational training.

We examined strategic planning documents used to identify recruiting and training needs as well as retention planning. We also examined the operations of the recruiting group and training systems for the three environments—the Canadian Army, the Royal Canadian Navy, and the Royal Canadian Air Force. We interviewed officials responsible in all of these areas, and conducted detailed interviews and site visits at seven recruiting detachments and four military bases. We reviewed a sample of applicant files for occupations that did not meet recruiting targets as well as another sample of training files of members on training in select occupations.

Criteria

To determine whether the Canadian Armed Forces implemented appropriate systems and practices to recruit, train, and retain the members needed to achieve the Canadian Armed Forces’ objectives, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

The Canadian Armed Forces develops and implements recruitment plans to recruit the right number of members with the right skills, in the right place, at the right time, and to achieve diversity. |

|

|

The Canadian Armed Forces implements practices to ensure it has effective selection tools and competent recruiting personnel. |

|

|

The Canadian Armed Forces maintains coordinated attraction programs to support recruiting operations. |

|

|

The Canadian Armed Forces implements a training system ensuring that recruits gain the required knowledge, skills, and competencies in a timely manner to carry out their duties effectively. |

|

|

The Canadian Armed Forces puts in place governance, processes, strategies, and capacity to develop recruits’ required knowledge, skills, and competencies. |

|

|

The Canadian Armed Forces identifies the levels and causes of attrition. |

|

|

The Canadian Armed Forces implements measures to address the causes of attrition. |

|

|

The Canadian Armed Forces monitors the effectiveness of its retention measures. |

|

Management reviewed and accepted the suitability of the criteria used in the audit.

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period between 1 April 2014 and 31 March 2016, and reached back over longer periods, as required, to gather evidence to conclude against criteria. Audit work for this report was completed on 28 September 2016.

Audit team

Assistant Auditor General: Jerome Berthelette

Principal: Gordon Stock

Director: Chantal Thibaudeau

Françoise Bessette

Jean-François Giroux

Tammi Martel

Robyn Meikle

Eric Provencher

Stephanie Taylor

List of Recommendations

The following is a list of recommendations found in this report. The number in front of the recommendation indicates the paragraph where it appears in the report. The numbers in parentheses indicate the paragraphs where the topic is discussed.

Reaching targets

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

5.34 The Canadian Armed Forces should establish appropriate representation goals for women for each occupation. It should also develop and implement measures to achieve them. (5.25–5.33) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. A series of initiatives, however, has been developed in order to meet objectives set by the Chief of the Defence Staff. The following initiatives have been or will be initiated before the end of 2016: A cultural shift is under way that positively affects the Canadian Armed Forces’ recruiting methods. The Canadian Armed Forces is giving priority processing and enrolment to women. It has recently re-energized its attraction and marketing strategy and has assigned women their own line of advertising priority. Previously serving female members who released from the Canadian Armed Forces in the last five years will be offered a return to the Canadian Armed Forces for full-time or part-time employment. The Canadian Armed Forces is prioritizing women applicants at its two Canadian military colleges as well. The following initiatives will be under way in 2017: The Canadian Armed Forces will stand up a full-time team called the Recruiting and Diversity Task Force, which will be dedicated to developing, planning, and executing activities aimed at increasing diversity group levels in the Canadian Armed Forces. An Advisory Board of prominent Canadians will also be created to advise the Canadian Armed Forces on recruiting. The Task Force and the Advisory Board will work together to influence Canadians and other stakeholders to make the Canadian Armed Forces an employer of choice. A women’s employment opportunity program will be implemented to inform and educate women about the benefits of a Canadian Armed Forces career. A Canadian Armed Forces retention strategy will be implemented to tailor policies and programs to increase retention. |

|

5.44 The Canadian Armed Forces should review its recruiting and training capacity and align this with its planning process to ensure that the recruiting plan reflects the personnel required in each occupation. (5.35–5.43) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. Several years of reductions to recruiting and training capacity as well as shrinking advertising and marketing budgets contributed to the current levels of institutional capacity. The Canadian Armed Forces is currently identifying the additional resources required to recruit and generate the required personnel for each occupation to reach authorized levels by 2018. |

|

5.52 The Canadian Armed Forces should develop and implement a three- to five-year target with an action plan for each occupation to meet recruiting needs, track progress, and take corrective action where necessary. (5.45–5.51) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Canadian Armed Forces currently uses a five-year long-range planning model that factors in attrition and growth. That model is then analyzed in detail to produce a Strategic Intake Plan for each occupation during the Annual Military Occupational Requirements process. This plan is used to determine the recruiting requirements of each occupation. However, the Canadian Armed Forces acknowledges that the planning process must become more agile to adjust to changing requirements throughout the process and take corrective action when required. The Canadian Armed Forces is currently undertaking measures to improve this planning process. |

Getting and developing the right people

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

5.71 The Canadian Armed Forces should implement targeted measures to attract enough qualified applicants for all occupations for which it has difficulty attracting applicants. (5.61–5.70) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Department of National Defence is developing a recruiting advertising and marketing campaign to better attract applicants. However, the Canadian Armed Forces acknowledges that more creative and tailored attraction, advertising, and marketing strategies are required to meet its recruiting targets for a number of occupations. Based on the Canadian Armed Force’s input, the Department will prioritize existing resources in support of this initiative. |

|

5.87 The Canadian Armed Forces should review its selection process with a view to improving its efficiency—including better file management methods and increased flexibility in the recruitment process—in order to maintain a sufficient pool of qualified applicants. (5.72–5.86) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Canadian Armed Forces is currently conducting an extensive review of its entire recruiting process for completion in the 2017–18 fiscal year with a goal of significantly reducing time between processing steps and making the entire process more agile and flexible. |

|

5.101 The Canadian Armed Forces should implement mechanisms for tracking members in occupational training in order to improve the timeliness of training. (5.88–5.100) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Canadian Armed Forces, as identified in this report, has been successful in ensuring minimal delays between enrolment and basic military training. However, the Canadian Armed Forces acknowledges that steps must be taken to better align follow-on occupational training to avoid lengthy delays. Basic Training List management will remain a focal point for our Canadian Armed Forces training authorities, and the implementation of a new Canadian Armed Forces human resource management system (Guardian) will allow for better alignment of training and tracking of Canadian Armed Forces members awaiting training. |

Keeping the right people

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

5.115 The Canadian Armed Forces should develop, implement, monitor, and evaluate measures to optimize retention for each occupation. (5.108–5.114) |

National Defence’s response. Agreed. The Canadian Armed Forces will develop a Canadian Armed Forces retention strategy in the 2017–18 fiscal year that will ensure that retaining qualified, competent, and motivated members in uniform is a fundamental aspect of how the Canadian Armed Forces manages its people. While the focus will continue to be the overall personnel requirements using the Annual Military Occupational Requirements process and the Strategic Intake Plan, the Canadian Armed Forces will manage occupational health by implementing tailored retention strategies as required. |