The Auditor General’s observations on the Government of Canada’s 2019–20 consolidated financial statements

Pay administration

Pay and benefits are one of the largest expenses in the Government of Canada’s consolidated financial statements. Every year, we test a sample of federal employees’ pay transactions as part of our audit of the consolidated financial statements to ensure that pay expenses are fairly presented. In 2016, the government’s Transformation of Pay Administration Initiative centralized pay processing for 46 departments and agencies into a Public Service Pay Centre and launched the Phoenix pay system for all 101 departments and agencies. We expanded our testing as a result of the internal control weaknesses in the then-new “HR-to-pay” process, which linked information in human resources (HR) systems with the pay system.

In our previous testing, we found a number of pay errors. The number of employees in our sample who were paid incorrectly, either too much or not enough, at least once during the fiscal year was 67% in 2018–19 and 62% in both 2017–18 and 2016–17. As reported in our previous observations, progress in addressing the errors in employee pay has been slow. Although these errors had an impact on employees, they did not have a significant impact on the consolidated financial statements. That is because total overpayments and underpayments partially offset each other and the government recorded year-end accounting adjustments to improve the accuracy of its pay expenses.

In each of the fiscal years since 2016, we tested all payments made to a sample of employees across departments and agencies for the entire year. We tested payments such as the following:

- basic pay (which includes items such as base salary and salary adjustments for promotions and for cost of living)

- pay for temporarily working at a higher level (acting pay)

- allowances (such as for education or for living in remote locations)

- a bonus for working in a bilingual position

Our audit approach is always evolving, and we made changes this past year as we determined where to focus our efforts to achieve the best value for Canadians. We considered the risk of pay errors having a significant effect on pay expenses reported in the consolidated financial statements. Our testing of pay transactions for the past 3 years consistently showed that overpayments and underpayments partially offset each other and therefore did not have a significant effect on the amount of pay expenses reported. We considered this trend and revised our testing approach to continue to improve its efficiency.

Our new approach tested only basic and acting pay for a sample of selected employees. We used this approach because those types of payments represent 92% of the $26 billion processed by the Phoenix pay system during the year. Our new testing continued to provide statistically sound evidence to support our independent auditor’s report. To compare results from year to year, we adjusted the prior-year results in the next section to reflect our new approach.

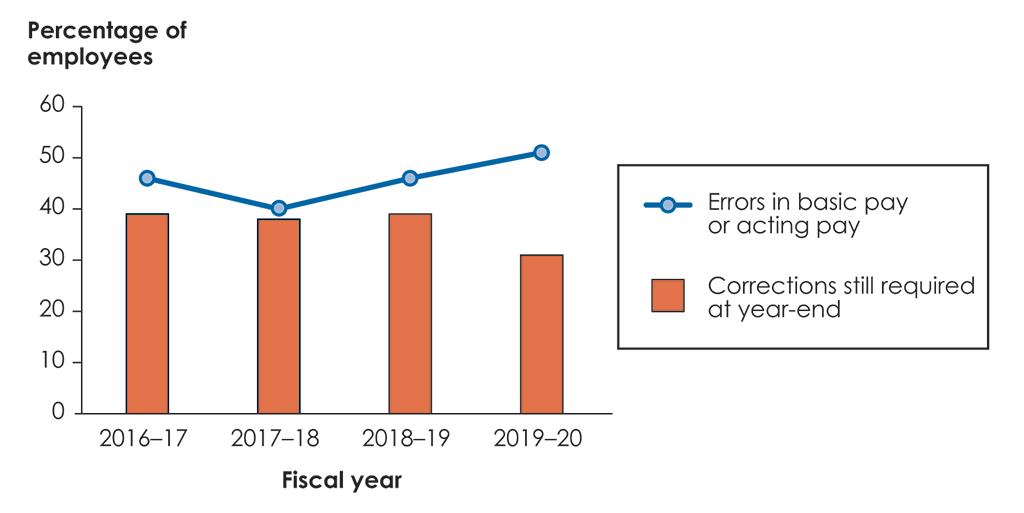

As a result of our audit work, we found that 51% of employees we sampled had an error in their basic or acting pay during the 2019–20 fiscal year, compared with 46% in the prior year. We also found that 31% of employees we sampled still required corrections to their pay as at 31 March 2020, an improvement over 39% in the prior year (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2—Percentage of employees in our sample with an error in basic or acting pay and who were awaiting a correction at year-end

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of a sample of employees’ pay transactions used in the audit of the consolidated financial statements of the Government of Canada for the 4 fiscal years ending 31 March from 2017 to 2020.

Exhibit 2—text version

This chart shows the percentage of employees in our sample with an error in basic or acting pay and who were awaiting a correction at year-end for each fiscal year from 2016–17 to 2019–20. Overall, the percentage of employees in our sample with an error in basic or acting pay increased slightly during the 4 fiscal years, but the percentage of employees who were awaiting a correction at year-end decreased. The chart shows that the percentage of employees in our sample who had an error in basic or acting pay during the fiscal year decreased from 46% in 2016–17 to 40% in 2017–18 and then increased to 46% in 2018–19 and to 51% in 2019–20. The chart also shows that the percentage of employees in our sample who were awaiting a correction at year-end was steady at either 38% or 39% for the 3 fiscal years from 2016–17 to 2018–19 and then decreased to 31% in 2019–20.

Our current-year testing showed that overpayments and underpayments made to employees continued to partially offset each other. The government again recorded year-end accounting adjustments to improve the accuracy of its pay expenses. These adjustments changed only the reported pay expenses in the consolidated financial statements. The adjustments did not correct the pay errors for the employees who were overpaid or underpaid.

We concluded that pay expenses were presented fairly in the Government of Canada’s 2019–20 consolidated financial statements.

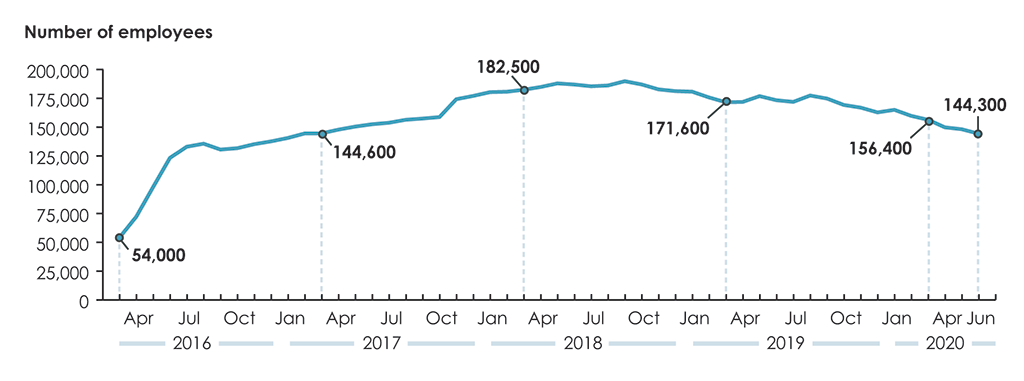

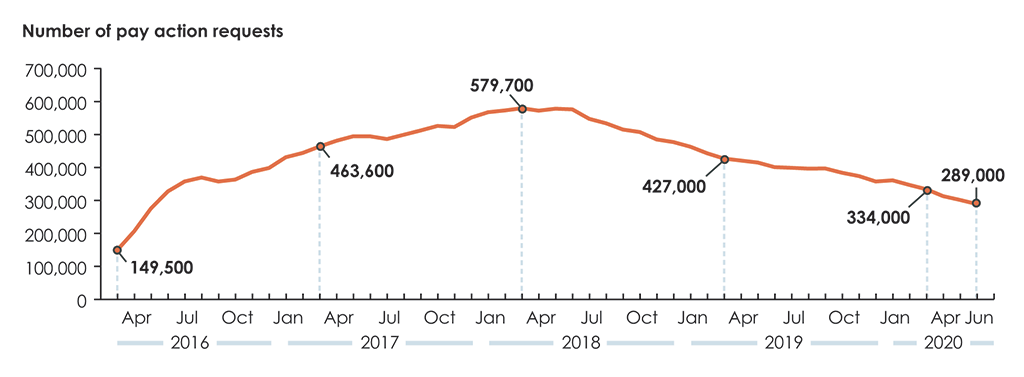

In the past few years, we have reported on the number of employees with outstanding pay action requests in the departments and agencies served by the Public Service Pay Centre. In the current year, the pay centre served 50 departments and agencies. As at 31 March 2020, there were 156,400 employees with pay action requests remaining to be processed (compared with 171,600 as at 31 March 2019). These employees had 334,000 outstanding pay action requests (compared with 427,000 the previous year). In June 2020, 3 months after the government’s fiscal year-end, the number of outstanding pay action requests further declined to 289,000, affecting 144,300 employees.

The number of outstanding pay action requests has been steadily declining for the past 2 years. However, on the basis of the current rate at which the pay centre is reducing the number of pay action requests, we estimate that it could take until December 2022 to address those currently outstanding. Given that the oldest pay action requests are not necessarily resolved first, it can take years for an employee’s pay to be fully corrected. As at 31 March 2020, 30% of requests were 2 years old or more (compared with 19% as at 31 March 2019) and 19% of requests were between 1 and 2 years old (compared with 29% the year before). The government expects that after December 2022, there will always be outstanding pay action requests as a result of normal ongoing pay transactions.

Exhibit 3 shows the number of employees with outstanding pay action requests, and Exhibit 4 shows the number of outstanding pay action requests. These exhibits show only the outstanding pay action requests for the departments and agencies served by the Public Service Pay Centre. They do not show the pay action requests in the other departments and agencies.

Exhibit 3—Number of employees with outstanding pay action requests in the departments and agencies served by the Public Service Pay Centre

Source: Based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of data in Public Services and Procurement Canada’s Case Management Tool

Exhibit 3—text version

This line chart shows the number of employees with outstanding pay action requests in the departments and agencies served by the Public Service Pay Centre. The chart shows that from March 2016 to June 2020, the number of employees with outstanding pay action requests went from 54,000 to 144,300.

In March 2016, there were 54,000 employees with outstanding pay action requests in the departments and agencies served by the Public Service Pay Centre. In March 2017, that number had risen to 144,600, and in March 2018, that number had risen to 182,500. In March 2019, that number had declined to 171,600. In March 2020, that number had declined to 156,400, and in June 2020, that number had declined to 144,300.

Exhibit 4—Number of outstanding pay action requests for the departments and agencies served by the Public Service Pay Centre

Source: From March 2016 to June 2018, based on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s analysis of data in Public Services and Procurement Canada’s Case Management Tool. From July 2018 to June 2020, based on data in Public Services and Procurement Canada’s Case Management Tool.

Exhibit 4—text version

This line chart shows the number of outstanding pay action requests in the departments and agencies served by the Public Service Pay Centre. The chart shows that from March 2016 to June 2020, the number of outstanding pay action requests went from 149,500 to 289,000.

In March 2016, there were 149,500 outstanding pay action requests in the departments and agencies served by the Public Service Pay Centre. In March 2017, that number had risen to 463,600, and in March 2018, that number had risen to 579,700. In March 2019, that number had declined to 427,000. In March 2020, that number had declined to 334,000, and in June 2020, that number had declined to 289,000.

Quality HR and pay data is critical to carrying out the government’s intention to create a long-term, sustainable, and efficient HR and pay system. HR and pay data affects not only salary payments but also other systems, notably pension and benefits. Many parties are involved in the HR-to-pay process: employees, supervisors, compensation advisors, HR teams, finance teams, and others. These parties share a responsibility in keeping accurate HR and pay records so that employees can be paid accurately and on time.

Our testing has once again identified problems in HR and pay data quality. Following are examples from our audit testing:

- Departments and agencies delayed either providing timely information to the Public Service Pay Centre or processing transactions. The delays resulted in inaccurate data used to calculate pay and consequently in pay errors. In 1 instance, an employee was overpaid for the last week of work in 2017. The recovery of the overpayment from the employee has yet to be initiated, and the person is no longer employed by the government. The untimely processing of this transaction increases the time and effort required to recover the overpayment.

- Departments and agencies delayed approving changes in pay for some employees who had assumed temporary roles. Documents that were needed to process changes in pay were not approved until months after employees started in their new roles. In this example, an employee began an acting assignment in February 2019, but the approval document was not completed until 3 months later. As a result of this delay, the employee was underpaid for a 3-month period.

We are concerned that if the government transitions to a new pay system, it could repeat weaknesses in the HR-to-pay process and continue paying employees inaccurately. For example, if data quality problems persist, they could result in errors in employee pay, regardless of which system processes the pay transactions.

The successful design and implementation of a possible new payroll system that can accurately process the complex and numerous government pay rules will require many elements, including the following:

- identifying the key risks

- designing appropriate and effective processes and controls

- quality data

- conducting pilots

- performing system testing

- training

- the collaboration of key functions in all departments and agencies

- an independent project oversight mechanism

We will continue to monitor and have discussions with the government on its progress toward a long-term, sustainable, and efficient HR and pay system.

National Defence inventory and asset pooled items

For 17 years, we have raised concerns about National Defence’s ability to properly account for the quantities and values of its inventory. We have also reported on National Defence’s asset pooled items, which are tangible capital assets that are managed like inventory. As at 31 March 2020, inventories at National Defence were valued at about $5.1 billion (or about 83% of the government’s total inventories). Asset pooled items were valued at about $3.6 billion and were included in the government’s tangible capital assets.

National Defence submitted a 10-year inventory management action plan to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts in the 2016–17 fiscal year. The plan set out actions to resolve challenges in properly recording the quantities and values of inventory. We are encouraged that National Defence reported to the committee by its annual deadline of 30 May 2020 that it had met nearly all the commitments in its inventory management action plan to date.

One of the inventory management plan’s key commitments is to add a modern scanning and barcoding capability to National Defence’s inventory management system. This capability is intended to increase the traceability of inventory and to provide more accurate and timely inventory data. The initiative is complex and is scheduled to be implemented by the end of the 2026–27 fiscal year. In our view, this capability will help strengthen inventory management and improve the accuracy of inventory and asset pooled items reported in the government’s consolidated financial statements.

National Defence continues to make progress to address its inventory management challenges. However, during this year’s audit, we found discrepancies in the reported amounts of inventory and asset pooled items. We noted a combined understatement at year-end of an estimated $759 million.

Maintaining adequate records and strong controls is important to managing assets for which National Defence is accountable. Inaccurate records, when pervasive, can affect National Defence’s ability to deliver its programs efficiently and cost-effectively. It could also result in decisions being made on the basis of inaccurate information. Moreover, in spring 2020, we reported that overall poor supply chain management often prevented National Defence from supplying the Canadian Armed Forces with inventory when it was needed (see the 2020 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada, Report 3—Supplying the Canadian Armed Forces—National Defence).

To report accurate and complete amounts of inventory and asset pooled items in the consolidated financial statements, National Defence needs to strengthen its internal controls. Although National Defence performs periodic inventory counts, we encourage it to make more effort to ensure reported balances are accurate and complete. National Defence could achieve this by doing further analysis and adding procedures to review balances of inventory and asset pooled items. These actions will contribute to validating the existence and valuation of the amounts in the consolidated financial statements.

Lastly, National Defence has made progress over the past year in its review of how it classifies items as either inventory or asset pooled items. We encourage National Defence to finalize its work in this area, including continual monitoring to further improve the accuracy of these balances.

Department of Finance Canada payments

As legislative auditors, we have a responsibility to assess whether financial transactions are in compliance with significant authorities. One of these significant authorities is the authority to spend public money that is granted through legislation passed by Parliament.

We also have a responsibility to report any matters that we consider should be brought to the attention of Parliament. One such matter concerns the federal government’s joint management partnership with the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador for the Hibernia offshore oil project. On 1 April 2019, the Minister of Finance signed an agreement with the province. The agreement stated that the federal government would make payments to the province totalling $3.3 billion over 38 years and that the necessary legislative measures would be introduced to authorize payments. During the 2019–20 fiscal year, the Department of Finance Canada made payments totalling $135 million to the province, through a payment mechanism. In our view, these payments were made without the proper legislative measures having been introduced. The department therefore did not obtain the authority of Parliament.

All spending of public money must be approved by Parliament to provide accountability and transparency to Canadians. This approval is one of Parliament’s fundamental roles. We have recommended to the Department of Finance Canada that it obtain the proper authority from Parliament before making any other payments under this agreement.