2017 Fall Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the Parliament of Canada Report 5—Environmental Petitions Annual Report and Retrospective

2017 Fall Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the Parliament of Canada Report 5—Environmental Petitions Annual Report and Retrospective

Table of Contents

- Note to Parliamentarians

- Introduction

- Retrospective on the Petitions Process

- Environmental Petitions Annual Report—July 2016 to June 2017

- Conclusion

- About the Environmental Petitions Annual Report and Retrospective

- Appendix—Petitions process

- Exhibits:

- 5.1—Follow-up case study: Petition 187—Regulations concerning lead and arsenic in fruit juices and bottled water

- 5.2—Follow-up case study: Petition 387—Concerns about Canada’s continued use and import of asbestos

- 5.3—Petitions raised many issues during the period from 1 July 2007 to 30 June 2017

- 5.4—Petitions came from five provinces between 1 July 2016 and 30 June 2017

Note to Parliamentarians

5.1 The environmental petitions process, created in 1995, is a unique way for Canadians to express their concerns and ask questions on environmental issues. The process is an opportunity to directly request information and answers from federal ministers. Petitions continue to raise a wide range of topics, issues, and questions, and to have an impact on federal policies and programs that protect the environment and promote sustainable development.

5.2 As an integral part of this report’s retrospective, we surveyed petitioners and federal departments and agencies. We found that both groups raised a number of issues concerning the petitions process and gave a number of corresponding recommendations. These findings are similar to what we found in our last retrospective, in the October 2007 Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development.

5.3 Issues raised by petitioners addressed the lack of a mandate under the Act to

- assess the quality and accuracy of responses from federal departments and agencies, and

- require departments and agencies to act on an issue raised by a specific petition.

5.4 Issues raised by federal departments and agencies addressed aspects of the Act relating to

- the lack of criteria and expectations regarding the quality of petition responses required, and

- the time required to respond to a petition, which is currently 120 calendar days.

5.5 Although some of these recommendations exceed our roles and responsibilities under the current Auditor General Act, the Commissioner has identified several areas of the petitions process that we can enhance. Going forward, we will focus our efforts in four key areas:

- review and improve how we communicate the petitions process to Canadians,

- review and improve how we help Canadians submit petitions,

- review and improve how we help federal departments and agencies respond to petitions (including providing feedback on how satisfied petitioners are with responses), and

- examine other ways to incorporate petitions into our audit work.

Introduction

5.6 For 21 years, since 1996, the Auditor General of Canada has received petitions from Canadians on issues involving environmental matters in the context of sustainable development, in accordance with section 22(1) of the Auditor General Act. The Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development administers the petitions process on behalf of the Auditor General.

5.7 In the October 2007 Commissioner’s report, we included a retrospective of the first 10 years of the petitions process. This year, we include another retrospective, which examines key facets of the process, such as types of issues raised, and survey results of petitioners and federal organizations.

5.8 Environmental petitions submitted by Canadians are valuable, and the process needs to be accessible, as demonstrated in our 2007 retrospective and our many interactions with petitioners over the years. The process is also a valuable instrument for federal departments and agencies.

For more information about the environmental petitions process, including the roles and responsibilities of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development and of federal government departments and agencies, see Getting Answers—A Guide to the Environmental Petitions Process, along with a summary of the process in the appendix.

Focus of the report

5.9 This report is in two parts. The first part looks back on environmental petitions submitted to the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development since 2007. It includes results from our 2017 survey of petitioners as well as government departments and agencies.

5.10 The second part is the Commissioner’s annual report on petitions. As required by the Auditor General Act, the annual report informs Parliament and Canadians about the petitions activity that took place over the past year—that is, the 12-month period from 1 July 2016 to 30 June 2017.

Retrospective on the Petitions Process

5.11 According to the surveys we conducted this year and our interactions with petitioners over the years, the petitions process remains valuable and relevant to Canadians, government departments and agencies, and the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development. The process also remains accessible to both individuals and organizations in Canada.

Petitions are valuable

5.12 Canadians continue to submit environmental petitions. A review of petitions over the years illustrates their value for Canadians and the Government of Canada. Between October 1996—when the first environmental petition was submitted—and June 2017, Canadians submitted a total of 473 petitions and follow-up petitions on a variety of environmental and sustainable development issues. (A petitioner may submit a follow-up petition after receiving a response to a previously submitted petition on the same topic.)

5.13 Petitions support our audit work and studies. Petitions are relevant and valuable to the Commissioner’s work because they inform the audit work we conduct. For example, climate change—a major focus of the fall 2017 Commissioner’s reports—has been the subject of many environmental petitions over the years.

5.14 The scope and variety of issues covered in the 21 petitions related to climate change since 2007 are extensive. For example, petition topics have ranged from concerns about energy efficiency in government workplaces (petitions 223 and 279), to adaptation measures in response to a changing climate (petitions 374 and 376), to plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (petitions 222, 291, and 390). Most petitions were concerned that the government was not doing enough to address issues related to climate change. One petition (petition 224) questioned whether Canada’s emission reduction plans acknowledged enough dissenting views on climate change evidence. Petitions cover a wide variety of other issues (see paragraph 5.19).

5.15 Ministers have responded in a timely manner. In addition to raising issues of concern, petitions pose specific questions for the federal government to answer. Since 1996, ministers have provided over 1,300 responses to petitioners. Starting with the 2001 Commissioner’s report, we have reported annually on the extent to which departments and agencies met their mandatory 120-day deadline for responding to petitions.

5.16 This year, we examined departmental and agency response statistics over the last 10 years. We found that except during the period from July 2008 to June 2009, when the rate dipped to 77 percent, the level of compliance with the 120-day deadline has ranged from 86 to 100 percent.

5.17 Actions taken to address issues raised by petitioners. Our follow-up case studies on two petitions—petition 187 (Exhibit 5.1) and petition 387 (Exhibit 5.2)—illustrate the influence petitions can have. These case studies show that the Government of Canada has lowered the maximum level of lead and arsenic in fruit juices and bottled water, and committed to banning asbestos and asbestos-related products by 2018.

Exhibit 5.1—Follow-up case study: Petition 187—Regulations concerning lead and arsenic in fruit juices and bottled water

Bottled water

Photo: © Africa Studio/Shutterstock.com

Lead and arsenic have long been associated with adverse health effects in humans, including increased cardiovascular disease, neurological damage, and cancer. Scientific studies have identified the negative consequences to human health from exposure to high levels of lead and arsenic, including when elevated concentrations of these substances are found in drinking water and foods.

Petition 187, submitted by David Boyd in December 2006, noted that the tolerance for lead and arsenic in apple juice and bottled water was several times higher than the international standards adopted by the Codex Alimentarius Commission. The petitioner asked whether there would be an amendment of the regulations under the Food and Drugs Act to lower the maximum level of allowable contaminants in beverages. The petitioner also questioned the allowable concentration of arsenic in bottled water.

Health Canada’s response

Health Canada, the department responsible for the establishment of food standards and tolerances under the Food and Drugs Act and regulations, responded to the petitioner in 2007 on behalf of itself and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. Health Canada acknowledged that the Canadian tolerance for ready-to-serve fruit juice was higher than the international standard. In its reply, the Department indicated that the Canadian standard would shortly be brought in line with the international standard. The Department also noted that it was revisiting regulations for bottled water.

Positive impacts

In 2014, Health Canada proposed changes to the tolerances for arsenic and lead in fruit juice, ready-to-serve fruit nectar beverages, and water in sealed containers. Consultations were carried out later that year. In January 2016, the Department’s website included the Summary of Comments and Responses to Health Canada’s Proposed Amendments to the Regulatory Tolerances for Arsenic and Lead in a Variety of Beverages. In March 2017, the Department published its formal notice to amend the maximum levels for arsenic and lead in juices and bottled water. The new regulations lowering the maximum level of contaminants are scheduled to take effect on 14 May 2018.

In the meantime, changes to the Department’s regulatory process in 2016 are intended to allow the Department to react faster to change maximum levels. Rather than going through a lengthy parliamentary process, the Department can now modify documents that are incorporated by reference into the Food and Drug Regulations. The Department indicated that it can complete this new process in months, rather than years.

Exhibit 5.2—Follow-up case study: Petition 387—Concerns about Canada’s continued use and import of asbestos

Chrysotile asbestos

Photo: © farbled/Shutterstock.com

Exposure to asbestos causes a form of cancer called mesothelioma, increases the risk of lung cancer, and causes asbestosis, a lung disease. The World Health Organization has called for eliminating all uses of asbestos. More than 50 industrialized nations have banned the use of all forms of asbestos. In 2015, Canada still allowed asbestos to be used in a number of products, although there were restrictions on its overall use.

Petition 387 was submitted in December 2015 by the Canadian Environmental Law Association and the Canadian Association of University Teachers. The two groups asserted that the Canadian government’s “controlled use” approach regarding asbestos did not adequately prevent harm to human health despite scientific evidence showing that asbestos exposure results in mesothelioma and other diseases. They sought clarity on Canada’s position on the continued use of asbestos. It was the fourth petition concerning the use or trade of asbestos.

The petition questioned whether the government had applied the precautionary principle in developing regulatory and non-regulatory measures for products containing asbestos. It asked whether the federal government was considering modifications to current regulations and urged Canada to ban asbestos. The petition was forwarded to three departments: Environment Canada (now Environment and Climate Change Canada), given its role in regulating toxic substances such as asbestos under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999; Health Canada, given the health implications of asbestos; and Public Works and Government Services (now Public Services and Procurement Canada), given its responsibility for federal buildings containing asbestos.

Departments’ responses

In its April 2016 response, Environment and Climate Change Canada noted its role in regulating the release of asbestos into the atmosphere under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 and explained how its import and export were monitored under the Rotterdam Convention.

Health Canada stated that it would continue to monitor the marketplace and examine evidence regarding the safety of consumer products. It also stated that it would carefully consider whether further protective measures were necessary.

Public Services and Procurement Canada responded that “effective April 1, 2016, there is a new departmental ban on the use of asbestos-containing materials (ACM) in all new construction and renovation for buildings within its portfolio.” It also committed to creating a National Asbestos Inventory for federally owned buildings in its portfolio. This inventory was released in September 2016.

Positive impacts

In December 2016, the Government of Canada announced that it would “fulfill its commitment to ban asbestos and asbestos-containing products by 2018.” It committed to “updating our international position regarding the listing of asbestos as a hazardous material based on Canada’s domestic ban before next year’s meeting of parties to the Rotterdam Convention, an international treaty involving more than 150 countries that support listing asbestos as a hazard.”

The government further committed to develop regulations that would “seek to prohibit all future activities respecting asbestos and asbestos-containing products, including the manufacture, use, sale, offer for sale, import and export.” At the same time, it published a mandatory survey notice under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 requiring industry to submit information on the manufacture, import, export, and use of asbestos and products that contain asbestos.

Interested parties were also given the opportunity to comment on proposed regulations intended for publication in December 2017. The regulations to implement an asbestos ban are expected to be developed by 2018.

Petitions are relevant

5.18 Petitions activity can happen for various reasons, including heightened interest in a particular issue. The following examples illustrate how a particular issue led to petitions activity. Between July 2013 and June 2014, we received 5 petitions on the October 2012 report of the Cohen Commission of Inquiry into the Decline of Sockeye Salmon in the Fraser River. Of the 16 petitions we received between July 2016 and June 2017, 7 were on the adverse health effects of electromagnetic radiation from personal devices. This activity followed the October 2016 tabling of a Government Response to a House of Commons Standing Committee on Health report on radiofrequency electromagnetic radiation and the health of Canadians as well as media coverage of this issue.

5.19 Human and environmental health was the issue most frequently raised in petitions over the last 10 years. All petitions raised at least one environmental issue. From 1 July 2007 to 30 June 2017, the issue most petitions raised was human and environmental health, followed by toxic substances, environmental assessment, and compliance and enforcement (Exhibit 5.3). Canadians demonstrate the relevance of petitions by using them to raise concrete issues, such as concerns about water quality, toxic substances, and waste management. They also use petitions for government management issues, such as concerns about governance, environmental assessments, and compliance and enforcement.

Exhibit 5.3—Petitions raised many issues during the period from 1 July 2007 to 30 June 2017

| Issues raised in petitions | Number of times issue referred to in petitionsNote * |

|---|---|

| Human or environmental health | 141 |

| Toxic substances | 86 |

| Compliance and enforcement | 71 |

| Environmental assessment | 71 |

| Water | 62 |

| Fisheries | 55 |

| Governance | 51 |

| Biodiversity | 37 |

| Science and technology | 36 |

| Federal–provincial relations | 30 |

| Natural resources | 28 |

| Transport | 26 |

| Climate change | 21 |

| Waste management | 20 |

| International cooperation | 19 |

| Indigenous affairs | 15 |

| Pesticides | 15 |

| Agriculture | 14 |

| Air quality | 12 |

5.20 Issues raised by the public are relevant to our audit planning and other work. One of the strengths of the environmental petitions process is our ability to audit and follow up on both environmental issues and departmental and agency responses. The petitions and their responses are an important source of information when we decide on the issues we intend to audit. Following up on petitions allows us to provide Canadians with updates on the federal government’s subsequent activities. For example, in 2012, we provided an update on government responses to petitions filed in 2010 and 2011 on hydraulic fracturing.

The petitions process is accessible

5.21 Individuals and organizations from most provinces and territories have submitted environmental petitions. Of the 222 petitions received from individuals and organizations since July 2007, more than half were submitted by individual Canadians or Canadian residents. These petitions included 28 follow-up petitions.

5.22 Petitions have included all federal departments and agencies subject to the process. The Auditor General Act currently requires ministers of 26 federal departments and agencies to respond to petitions within 120 days of receiving the petition from the Commissioner. All 26 federal organizations have received at least 1 petition in the past 10 years.

5.23 The departments that have received the most petitions since 1 July 2007 are Environment and Climate Change Canada, Health Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Natural Resources Canada, and Transport Canada.

The petitions process can be improved

What we learned

5.24 On behalf of the Auditor General of Canada, the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development works with petitioners and federal departments and agencies to answer questions and provide clarification as needed.

5.25 In 2007, a survey of petitioners led to increased awareness of the petitions process. For example, the 2007 Commissioner’s report led to the 2008 publication of a downloadable petitions guide, Getting Answers—A Guide to the Environmental Petitions Process, which was updated in 2014. The guide contains helpful tips for writing petitions and framing questions, along with a template and checklist for potential petitioners.

5.26 This year, to assist in our review of the petitions process, we surveyed individuals and organizations that had submitted an environmental petition or received a response since 1 January 2012. We also surveyed officials from 26 federal departments and agencies that had responded to an environmental petition between 2012 and 2017. We wanted to know whether the petitioners and the departments and agencies were satisfied with the petitions process, what their experiences were with the process and with any help we gave, and how they would improve the process.

5.27 While petitioners and federal departments and agencies were happy with the support they received from the Commissioner, both groups identified areas that could be enhanced. As a result, we will continue to examine our approach to make improvements.

5.28 Going forward, we will focus our efforts in four key areas:

- review and improve how we communicate the petitions process to Canadians,

- review and improve how we help Canadians submit petitions,

- review and improve how we help federal departments and agencies respond to petitions (including providing feedback on how satisfied petitioners are with responses), and

- examine other ways to incorporate petitions into our audit work.

What petitioners think

5.29 Overall process. In general, surveyed petitioners were satisfied with the petitions process and felt that it was relevant and valuable. Most were also satisfied with the overall experience of the process.

5.30 Petitioners were very satisfied with the Commissioner’s resources: almost all of the petitioners who used the petitions guide found it to be helpful or somewhat helpful. Of those who used the online petitions catalogue, almost all found it to be helpful. All petitioners who consulted with the Commissioner’s team when preparing their petitions found these interactions to be helpful.

5.31 Reasons for submitting a petition. Petitioners most often cited the following reasons for submitting petitions:

- to request that departments or agencies take action on addressing environmental issues;

- to establish a formal public record of the responses of departments or agencies to environmental issues;

- to inform or raise awareness of an environmental issue within the federal government;

- to obtain specific information on departmental or agency actions, plans, or policies that support environmental issues; or

- to seek formal commitments from departments or agencies on environmental issues.

5.32 Responses. Petitioners were generally dissatisfied with the responses they received from federal departments or agencies. We noted a disconnect between what petitioners expected and what federal organizations provided in their responses. Petitioners commented that responses were too brief, evaded the crux of questions, were ambiguous, or did not provide enough evidence.

5.33 Despite this dissatisfaction, a significant number of petitioners felt that their petitions had some effect on the way the federal government manages issues raised in the petitions.

5.34 Suggested improvements. We asked petitioners for recommendations on how to improve the petitions process. Some petitioners said that the Auditor General should have the power to require departments and agencies to act, while others said that the Commissioner should investigate petition responses to ensure that they are detailed and accurate.

5.35 These types of recommendations exceed the scope of our roles and responsibilities under the current Auditor General Act. However, going forward, we will provide feedback to responding departments and agencies on how satisfied petitioners are with responses.

5.36 Other suggestions included having the Commissioner raise awareness of the petitions process by alerting the public when a number of petitions cover the same issue or by reminding Canadian organizations of the process. Other petitioners thought the quality of responses should be managed more by, for example, providing petitioners with a means to respond to or rate responses.

What departments and agencies think

5.37 Overall process. Although petitions may not directly lead to policy changes, several departments and agencies identified how useful the petitions process was in drawing the government’s attention to issues of concern to Canadians. About three quarters of departments and agencies surveyed believed the process had an impact on how the federal government manages environmental and sustainable development issues in Canada. About a quarter felt that petition issues influenced how departments and agencies worked on or made a decision.

5.38 Departments and agencies were generally satisfied with the Commissioner’s resources. All departments and agencies that used the petitions checklist and our website found them somewhat or very helpful. All found the Commissioner’s team to be helpful.

5.39 Scope and clarity of petition questions. Departments and agencies indicated that they were sometimes challenged by the nature of petition questions. For example, departments and agencies were sometimes unclear on how to properly respond to petitions that contained imprecise questions.

5.40 Preparing responses. Departments and agencies also noted that some petition questions often required lengthy responses, despite the Commissioner’s recommendation that petitions not exceed 10 questions. In addition, several departments and agencies felt challenged if they were only peripherally related to the petition or certain questions in the petition.

5.41 Departments and agencies indicated that criteria and expectations relating to the quality of petition responses required by legislation needs to be clearer. Several departments and agencies asked the Commissioner to provide clearer specifications for a quality response as well as examples for guidance.

5.42 Many departments and agencies attributed an increased workload to the challenges of coordinating responses within and between departments and agencies. Challenges included whether a department or agency was large and whether internal coordination was required among several branches; whether responses had to be coordinated between multiple departments and agencies; whether questions were highly technical, legally or scientifically; or whether events outside the petitions process, such as elections and holidays, made meeting response deadlines difficult.

Environmental Petitions Annual Report—July 2016 to June 2017

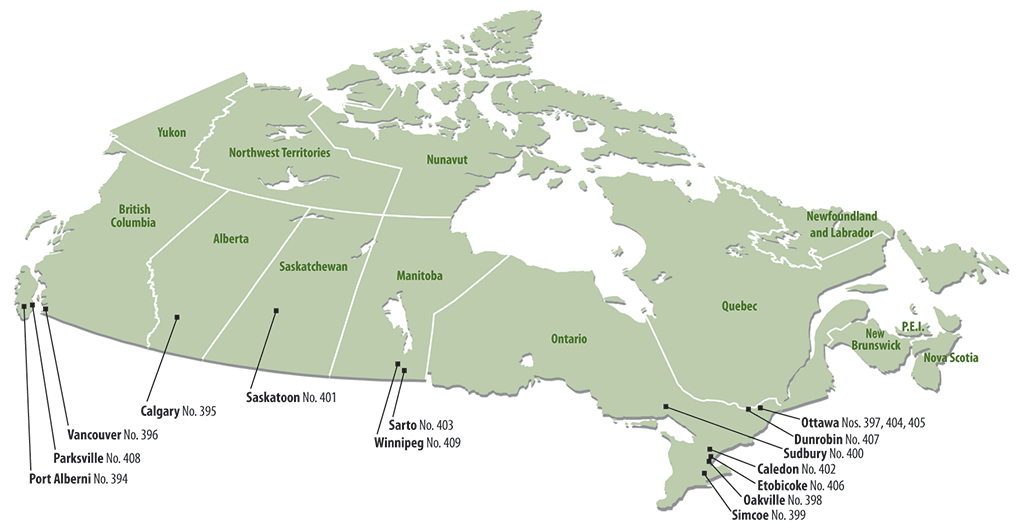

5.43 The Office of the Auditor General of Canada received 16 environmental petitions between 1 July 2016 and 30 June 2017, compared with 13 the previous reporting year and 15 the year before. Petitions originated from five provinces: British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Ontario (Exhibit 5.4). We identified no issues with the timeliness and completeness of responses by departments and agencies.

Exhibit 5.4—Petitions came from five provinces between 1 July 2016 and 30 June 2017

British Columbia

408—The relationship of science to the Federal Sustainable Development Strategy

Alberta

395—Impact on migratory birds of tailings ponds in Alberta’s oil sands mines

Saskatchewan

401—Institutionalized resistance to climate change action (wind energy)

Manitoba

403—Exposure of vulnerable persons to microwave and radiofrequency radiation

Ontario

400—Timeliness of environmental assessments for projects 2 and 3 (Ontario Highway 69 expansion)

402—Precautionary messaging and advisories in schools for safer use of wireless devices

404—Nesting barn swallows at Norman Rodgers Airport, in Kingston, Ontario

405—Canadian nuclear legacy liabilities: Cleanup costs for Chalk River Laboratories

Source: Petitions submitted to the Auditor General of Canada. Summaries are available on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s website.

Exhibit 5.4 map—text version

This map of Canada shows the communities from which the petitions came during the period from 1 July 2016 to 30 June 2017. Petitions came from five provinces: British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Ontario.

British Columbia

- Port Alberni: Petition 394

- Parksville: Petition 408

- Vancouver: Petition 396

Alberta

- Calgary: Petition 395

Saskatchewan

- Saskatoon: Petition 401

Manitoba

- Winnipeg: Petition 409

- Sarto: Petition 403

Ontario

- Simcoe: Petition 399

- Oakville: Petition 398

- Etobicoke: Petition 406

- Caledon: Petition 402

- Sudbury: Petition 400

- Dunrobin: Petition 407

- Ottawa: Petitions 397, 404, and 405

Summaries of all petitions received since 1996 and their responses are available in the petitions catalogue on the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s website. The full text of petitions is available by request.

5.44 Of note, 7 petitions concerned potential adverse health effects on humans from radiofrequency electromagnetic radiation from personal wireless devices, such as cellphones, tablets, baby monitors, and Wi-Fi Internet routers. All of these petitions focused on recommendations established by Safety Code 6, Health Canada’s radiofrequency human exposure guidelines. Many of these petitions concerned the review process of Safety Code 6 and questioned whether guidelines gave sufficient protection to humans. Others concerned the adequacy of these guidelines in different contexts, and the level of awareness around the safe use of wireless devices.

5.45 As required under section 22 of the Auditor General Act, all petitions received this year were forwarded within 15 days to the federal minister or ministers responsible for the issues raised in the petitions. Of the 8 petitions requiring a response this year, all departments and agencies gave their required responses within legislated timelines. Based on our assessment, their responses were complete—that is, all questions in the petition received an answer.

Conclusion

5.46 The environmental petitions process continues to have value and relevance for Canadians. It serves to raise the government’s awareness on a wide range of important environmental topics and questions.

5.47 While petitioners and federal departments and agencies were pleased with the support we provide, we will continue to make improvements. Specifically, we will focus on reviewing and improving how we communicate the petitions process to Canadians, how we help Canadians submit petitions, and how we help federal departments and agencies respond to petitions. We also will examine additional ways to incorporate petitions into our audit work.

About the Environmental Petitions Annual Report and Retrospective

Objective

The objective of this annual report is to inform Parliament and Canadians about the use of the environmental petitions process. This report provides an overview or retrospective of the environmental petitions submitted to the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development in the 10 years since the first retrospective on petitions was produced in 2007. As well, in accordance with section 23 of the Auditor General Act, the report describes the number, subject matter, and status of petitions received and the timeliness of responses from ministers.

Scope and approach

The annual report on environmental petitions summarizes the monitoring of the petitions process by the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development within the Office of the Auditor General of Canada. Information on the petitions process can be found on the Office’s website and within the online guide, Getting Answers—A Guide to the Environmental Petitions Process.

As part of the retrospective, we used FluidSurveys software to create separate voluntary and confidential surveys for petitioners and for federal organizations about their experiences with the environmental petitions process. In March 2017, we sent a questionnaire electronically to the 26 federal organizations subject to the process under the Auditor General Act asking about their experiences with environmental petitions over the past five years (since 2012). In April 2017, we sent a second survey electronically to the 72 petitioners who had submitted an environmental petition or received a response since January 2012.

Period covered by the report

The annual report on environmental petitions covers the period from 1 July 2016 to 30 June 2017. The retrospective of the petitions process covers the period between 1 July 2007 and 30 June 2017.

Petitions team

Principal: Kimberley Leach

Director: George Stuetz

Nathan Adams

Camilla Chiari

Carolle Mathieu

Charlotte Mussells

Kris Nanda

Mary-Lynne Weightman

Appendix—Petitions process

The environmental petitions process and the role of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development

Environmental petitions process

Starting a petition

A Canadian resident submits a written petition to the Auditor General of Canada.

Reviewing a petition

The Commissioner reviews the petition to determine whether it meets the requirements of the Auditor General Act.

If the petition meets the requirements of the Auditor General Act, the Commissioner will

- determine which federal departments and agencies are responsible for the issues addressed in the petition;

- send it to the ministers responsible; and

- send a letter to the petitioner, listing the ministers to whom the petition was sent.

If the petition does not meet the requirements of the Auditor General Act, the petitioner will be informed in writing.

If the petition is incomplete or unclear, the petitioner will be asked to resubmit it.

Responding to a petition

Once a minister receives a petition, he or she must

- send a letter, within 15 days, to the petitioner and the Commissioner acknowledging receipt of the petition; and

- consider the petition and send a reply to the petitioner and the Commissioner within 120 days.

Ongoing petition activities

Monitoring

The Commissioner monitors acknowledgement letters and responses from ministers.

Reporting

The Commissioner reports to Parliament on the petitions and responses received.

Posting on the Internet

The Commissioner posts summary information of each petition, and the responses, on the Internet in both official languages.

Auditing

The Office of the Auditor General considers issues raised in petitions when planning future audits.

Outreach

The Commissioner carries out a variety of outreach activities to inform Canadians about the petitions process.

Source: Adapted from the Auditor General Act and Getting Answers—A Guide to the Environmental Petitions Process.